ACCP9美国胸科医师协会抗栓与血栓预防指南

- 格式:pptx

- 大小:443.01 KB

- 文档页数:54

ACCP新指南:并非所有患者适用DVT预防美国胸科医师学会(ACCP)最新指南《抗栓治疗和血栓形成预防临床实践指南(第9版)》推荐,决定使用或不使用深静脉血栓(DVT)和静脉血栓栓塞(VTE)预防性治疗时要考虑个别患者血栓形成风险。

该指南对患者风险进行分类,这提示临床医师在进行预防性治疗前应考虑患者DVT/VTE风险。

长途旅行的DVT/VTE风险因素研究虽然大多数患者不易出现旅行相关性深静脉血栓形成/静脉血栓栓塞,但指南支出,长途航班后,几种因素可能会增加个体DVT/VTE风险,包括既往DVT/VTE或已知的血栓形成性疾病;恶性肿瘤;近期手术或创伤;不活动;使用雌激素或怀孕;坐在靠窗的座位。

由于旅客的旅游相关性DVT / VTE风险升高,该指南建议应经常行走,拉伸小腿肌肉,如果可能的话坐在靠过道的座位,或使用膝盖下渐进性压力弹性袜即静脉曲张袜。

相反,该指南建议称,尚无确切证据显示脱水,饮酒,或坐经济舱可增加长途飞行对患者造成的DVT / VTE风险。

阿司匹林及新疗法预防DVT / VTE该指南还还对提出了有关使用新疗法或潜在疗法用于DVT / VTE预防和治疗的建议。

虽然阿司匹林用于DVT/VTE预防并不是什么新方法,但以前的ACCP指南反对在任何手术人群中使用阿司匹林单药进行预防性治疗。

最新版的治疗指南中,ACCP已对此进行了修订,并表示在大多数矫形手术中,阿司匹林也是预防DVT/VTE的一种选择,尽管其不是首选药物。

抗栓指南的创新《抗栓治疗和血栓形成预防临床实践指南(第9版)》包括显著影响血栓形成的预防,诊断和治疗的600多条建议的创新。

两个关键的进步是更加明确和定量的考虑对患者重要的指标和预后限定因素。

后者的创新引起血栓形成预防中对机体指标不同的解释,而以前曾重点监测无症状血栓。

资料来源:New Guidelines Suggest DVT Prophylaxis not Appropriate for All Patients.美国胸科医师学会,2012/02/07全文:New Guidelines Suggest DVT Prophylaxis not Appropriate for All PatientsArticle | 02.07.12(NORTHBROOK, IL, FEBRUARY 7, 2012) — New evidence-based guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommend considering individual patients’risk of thrombosis when deciding for or against the use of preventive therapies for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and venous thromboembolism (VTE). Specifically, the Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines, published in the February issue of the journal CHEST, focus on risk stratification of patients, suggesting clinicians should consider a patient’s risk for DVT/VTE and risk for bleeding before administering or prescribing a prevention therapy.“There has been a significant push in health care to administer DVT prevention for every patient, regardless of risk. As a result, many patients are receiving unnecessary therapies that provide little benefit and could have adverse effects,”said Guidelines Panel Chair Gordon Guyatt, MD, FCCP, Department of Medicine, McMaster University Faculty of Health Sciences, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. “The decision to administer DVT prevention therapy should be based on the patients’risk and the benefits of prevention or treatment.” To address this, the ACCP guidelines provide comprehensive risk stratification recommendations for most major clinical areas, including medical, nonorthopedic surgery, orthopedic surgery, pregnancy, cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, stroke, pediatrics, and long-distance travel.DVT/VTE Risk Factors for Long-distance TravelAlthough developing a travel-related DVT/VTE is unlikely in most cases, the guidelines note that for long-distance flights, several factors may increase an individual’s risk of developing a DVT/VTE, including previous DVT/VTE or known thrombophilic disorder; malignancy; recent surgery or trauma; immobility; estrogen use or pregnancy; and sitting in a window seat. For travelers with an increased risk for travel-related DVT/VTE, the guidelines recommend frequent ambulation, calf muscle stretching, sitting in an aisle seat if possible, or the use of below-knee graduated compression stockings. Conversely, the guidelines suggest there is no definitive evidence to support that dehydration, alcohol intake, or sitting in economy class increases a patient’s risk for developing a DVT/VTE resulting from long-distance flights. Aspirin and New Therapies for DVT/VTE PreventionThe guidelines also provide recommendations related to the use of new or potential therapies for the prevention and treatment of DVT/VTE. Although aspirin is not a new therapy for the prevention of DVT/VTE, previous ACCP guidelines recommended against using aspirin as the single agent for prophylaxis in any surgical population. In the current edition, the ACCP has revised this recommendation and indicates aspirin is an option—although not typically the agent of choice—for the prevention of DVT/VTE in major orthopedic surgery.“Although we are not recommending aspirin as the optimal DVT/VTE prophylaxis, we have reviewed the existing evidence and concluded that aspirin is an acceptable option in some instances where preventive therapy is needed,”said guideline co-author Mark Crowther, MD, Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. In regard to new oral anticoagulants, guideline authors recognize the recent clinical trials of apixaban and rivaroxaban, both direct factor Xa inhibitors, and dabigatran etexilate, a direct thrombin inhibitor, and offer recommendations for the new agents for select clinical conditions, including atrial fibrillation and orthopedic surgery.Innovations in Antithrombotic GuidelinesThe Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines include innovations that have significantly impacted the more than 600 recommendations for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of thrombosis. Two key advances are the more explicit and quantitative consideration of patient values and preferences and restriction of outcomes to only those deemed to be important for the patient. The latter innovation results in different interpretation of the body of evidence in thrombosis prevention that has previously focused on the detection of asymptomatic thrombosis by surveillance methods.Guideline authors also took a more critical look at the overall process of guideline development, providing more methodologically sophisticated scrutiny of all available evidence. “The evidence review for the new guidelines was more rigorous than ever before, and our method for grading research studies has become even more stringent,”said guideline co-author David Gutterman, MD, FCCP, ACCP Immediate Past President, Cardiovascular Research Center, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. “We believe that the objective rigorous application of the science of guideline development will ultimately best serve our patients.”The guidelines are endorsed by the following medical associations: the American Association for Clinical Chemistry, American College of Clinical Pharmacy, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, American Society of Hematology, International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis, and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (pregnancy article only).For more information about the guidelines and accompanying clinician resources, visit and follow #AT9 on Twitter. Patient resources related to the guidelines are available through OneBreath®, an initiative of The CHEST Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the ACCP.About the American College of Chest PhysiciansThe ACCP represents 18,400 members who provide patient care in the areas of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine in the United States and more than 100 countries throughout the world. The mission of the ACCP is to promote the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chest diseases through education, communication, and research. CHEST is the official peer-reviewed publication of the ACCP. More than 30,000 readers worldwide turn to CHEST in print and 400,000 people view CHEST online each month for the latest in chest-related medicine. For more information about the ACCP, visit or follow the ACCP via social media at /accpchest and @accpchest.。

21.对主动脉机械瓣膜置换患者,推荐用VKA治疗目标INR, 2.5; (范围, 2.0~3.0)优于更高的IN R目标(1B)。

22.对二尖瓣机械瓣膜置换患者,建议用VKA治疗目标INR, 3.0; (范围, 2.5~3.5)优于较低的IN R目标(2C)。

23.对主动脉瓣和二尖瓣双机械瓣膜置换的患者,建议VKA治疗目标INR 3.0 (范围2.5~3.5)优于目标INR2.5 (范围 2.0~3.0)(2C)。

对主动脉瓣或二尖瓣机械瓣膜置换患者,VKA治疗加抗血小板药。

24.对二尖瓣或主动脉瓣机械瓣置换、出血低危的患者,建议VKA加小剂量抗血小板药如阿司匹林( 50~100 mg/d)治疗(1B)。

25.对主动脉瓣或二尖瓣机械瓣膜置换患者,推荐VKA治疗优于抗血小板药(1B)。

26.对进行了二尖瓣修复、正常窦性心律的患者,建议头3个月用抗血小板药治疗优于VKA治疗(2C )。

27.对拟行主动脉瓣修复的患者,建议用阿司匹林50 ~100 mg/d(2C)。

28.对右侧人工瓣血栓形成患者,如无禁忌症,建议溶纤治疗(2C)。

29.对左侧人工瓣血栓形成患者,血栓面积≥0.8 cm2,建议早期手术优于溶纤治疗(2C),如果存在手术禁忌症,建议溶纤治疗(2C)。

30.对左侧人工瓣血栓形成患者,血栓面积小(<0.8 cm2),建议溶纤治疗优于手术。

对于极小的、非梗阻性血栓,建议静脉内用普通肝素,并用多谱勒超声心动图监测,证实血栓溶解或改善(2C )。

缺血性卒中的抗栓或溶栓治疗1.对于急性缺血性卒中、在症状发作3小时内能启动治疗的患者,推荐静脉内(IV)用重组组织型纤溶酶原激活物(r~tPA)治疗(1A)。

2. 对于急性缺血性卒中、在症状发作4.5小时而非3小时内能启动治疗的患者,建议IV用r~tPA(2 C)。

3. 对于急性缺血性卒中、在症状发作4.5小时内不能启动治疗的患者,建议不用IV r~tPA(1B)。

第9版《抗栓治疗及预防血栓形成指南》(ACCP近日,美国胸内科医师学会(ACCP)在《胸》(Chest 2012,141:7S-47S)杂志公布了第9版《抗栓治疗及预防血栓形成指南》(ACCP-9)。

此版指南在第8版基础上,结合最新循证医学证据,对抗栓治疗进行了全面细致的推荐。

聊城市第二人民医院骨病外科刘士明阿司匹林一级预防再受推荐ACCP-9最新推荐:对于心血管病一级预防,年龄>50岁且无心血管疾病症状的人群应用小剂量阿司匹林75~100 mg/d 优于不用(推荐级别:2B)。

新指南指出,阿司匹林服用10年可以轻度降低各类心血管风险的全因死亡率。

对于心血管风险中高危患者来说,心肌梗死发生率降低的同时伴随严重出血的增加。

不论何种风险患者,如果不愿长期服药以换取很小的获益,可以不用阿司匹林进行一级预防。

心血管风险中高危患者,若心肌梗死预防获益大于胃肠道出血风险,应当应用阿司匹林。

阿司匹林用于心血管疾病一级预防疗效确切对于心血管疾病来说,推行健康的生活方式、有效控制危险因素、合理使用循证药物,才能真正发挥预防的作用。

作为防治心脑血管疾病的基石,阿司匹林的心血管益处已得到大量循证医学证据的证明,适用于动脉粥样硬化疾病的一级、二级预防和急性期治疗。

既往基于6项大规模随机临床试验[英国医师研究(BMD)、美国医师研究(PHS)、血栓形成预防试验(TPT)、高血压最佳治疗研究(HOT)、一级预防研究(PPP)和妇女健康研究(WHS)]的荟萃分析表明,未来10年心血管事件风险>6%的个体服用阿司匹林的获益大于风险。

最近,英国学者在《内科学年鉴》(Ann Intern Med)杂志发表了一项荟萃分析,对应用阿司匹林进行常规一级预防提出质疑。

然而,在ACCP-9中,采用包含最新临床试验的高质量系统性评估和荟萃分析对阿司匹林相对作用进行评估的结果显示,每治疗1000例患者,阿司匹林使低危人群心肌梗死减少6例,总死亡减少6例。

—实施概要美国胸科医师学院循证医学临床实践指南:—抗栓治疗与血栓预防(第9版)Gordon H. Guyatt , MD, FCCP ; Elie A. Akl , MD, PhD, MPH ; Mark Crowther , MD ;David D. Gutterman, MD, FCCP; Holger J. Schünemann, MD, PhD, FCCP; for the American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel*缩略语ACS=急性冠脉综合征; AF=心房颤动; AIS=动脉缺血性卒中; APLA=抗磷脂抗体;ASA =阿司匹林;AT9 = 抗栓治疗与血栓预防(第9版),美国胸科医师学院循证医学临床实践指南;BMS=裸金属支架;CABG=冠状动脉搭桥术; GAD=冠状动脉疾病;CDT=导管溶栓;CHADS2 =充血性心力衰竭,高血压,年龄≥75岁,糖尿病,卒中或短暂脑缺血发作;CSVT=大脑窦静脉血栓形成; CTPH=慢性血栓栓塞性肺动脉高压;CUS=压缩超声;CVAD=中心静脉植入装置;DES=药物洗脱支架;GCS=分级加压弹力袜;;HFS=髋骨骨折手术;HIT =肝素诱导的血小板减少症;HITT=肝素诱导的血小板减少症合并血栓形成;IA=动脉内的;ICH=颅内出血;IE=感染性心内膜炎; INR=国际标准化比率;IPCD=间歇充气加压装置;IVC=下腔静脉;LDUH=低剂量普通肝素;LMWH=低分子肝素;LV=左心室;MBTS=改良Blalock-Taussig分流术;MR=核磁共振成像;PAD=-外周动脉疾病;PCI=经皮冠状动脉介入治疗;PE=肺栓塞;PFO=卵圆孔未闭; PMBV=经皮二尖瓣球囊成形术; PTS=栓塞后综合征; PVT=人工瓣膜血栓形成; r-tPA=重组组织型纤溶酶原活化剂;RVT=肾静脉血栓形成;SC=皮下;TEE=经食管超声心动图; THA=全髋关节置换术;TIA=短暂性缺血发作;TKA=全膝关节置换术;UAC=脐动脉导管; UEDVT=上肢深静脉血栓形成;UFH=普通肝素;US=超声;UVC=脐静脉导管;VAD=心室辅助装置;VKA=维生素k拮抗剂前言已发表的ACCP第8版抗栓指南,以文章的形式,叙事性的证据总结和原则作为推荐,一小部分从循证得出的证据资料总结,一些项目来自于原始研究的广泛汇总表。

·综述与讲座·静脉血栓栓塞性疾病的抗血栓治疗———解读美国胸科医师学会循证医学临床实践指南(第9版)李圣青(解放军第四军医大学西京医院呼吸与危重症医学科,陕西西安710032)摘要:美国胸科医师学会(ACCP)抗栓治疗和血栓预防临床实践指南第9版的抗血栓治疗篇重点讲述了静脉血栓栓塞性疾病(VTE)的治疗。

与第8版指南相比,第9版指南有很大程度的修改并增添了部分新的内容。

除了抗血栓药物、使用装置或外科手术技术在深静脉血栓形成(DVT)和肺栓塞(PE)(统称为VTE)的使用建议外,还提供了关于血栓后综合征(PTS),慢性血栓栓塞性肺动脉高压(CTPH),偶然诊断的(无症状)DVT或PE,急性上肢深静脉血栓形成(UEDVT),浅静脉血栓形成(SVT),内脏静脉血栓形成和肝静脉血栓形成的治疗建议。

本文对相关部分内容进行了解读。

关键词:静脉血栓栓塞症;急性下肢深静脉血栓;急性肺血栓栓塞;抗凝;溶栓中图分类号:R543.6文献标志码:A doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-3826.2013.06.41文章编号:1671-3826(2013)06-0647-04美国胸科医师学会(ACCP)于2012年发布了第9版抗栓治疗和血栓预防临床实践指南[1],与第8版指南相比有较大程度的修改并增添了部分新的内容,且更为简洁明了。

对待不同的治疗既表现出谨慎而稳妥,又表现出积极和开放。

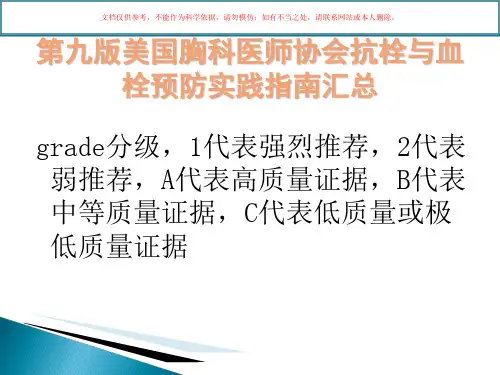

指南规定高质量的临床证据为A级,中等质量的临床证据为B级,低质量的临床证据为C级。

根据临床证据等级的不同,将推荐等级分为强烈推荐(1级)和建议(2级)。

强烈推荐适用于大多数病人,建议则根据患者的具体情况而定,包括患者的个人选择。

绝大多数推荐和建议都是基于静脉血栓栓塞性疾病(VTE)的复发风险与抗凝或溶栓出血风险二者之间的权衡而得出的结论。

1急性深静脉血栓形成(DVT)的治疗1.1急性DVT抗凝治疗的时机对于高度怀疑VTE患者抗凝时机的把握,第9版指南给出了更加积极的抗凝建议。

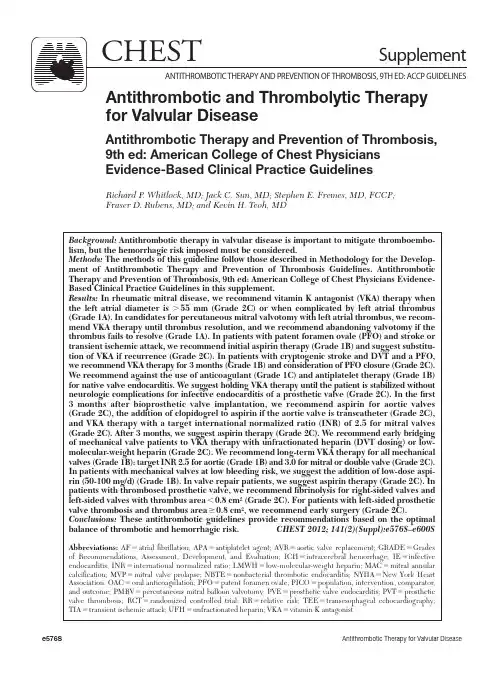

B ackground: A ntithrombotic therapy in valvular disease is important to mitigate thromboembo-lism, but the hemorrhagic risk imposed must be considered. M ethods: T he methods of this guideline follow those described in Methodology for the Develop-ment of Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Guidelines. Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines in this supplement. R esults: I n rheumatic mitral disease, we recommend vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy when the left atrial diameter is . 55 mm (Grade 2C) or when complicated by left atrial thrombus (Grade 1A). In candidates for percutaneous mitral valvotomy with left atrial thrombus, we recom-mend VKA therapy until thrombus resolution, and we recommend abandoning valvotomy if the thrombus fails to resolve (Grade 1A). In patients with patent foramen ovale (PFO) and stroke or transient ischemic attack, we recommend initial aspirin therapy (Grade 1B) and suggest substitu-tion of VKA if recurrence (Grade 2C). In patients with cryptogenic stroke and DVT and a PFO, we recommend VKA therapy for 3 months (Grade 1B) and consideration of PFO closure (Grade 2C). We recommend against the use of anticoagulant (Grade 1C) and antiplatelet therapy (Grade 1B) for native valve endocarditis. We suggest holding VKA therapy until the patient is stabilized without neurologic complications for infective endocarditis of a prosthetic valve (Grade 2C). In the fi rst 3 months after bioprosthetic valve implantation, we recommend aspirin for aortic valves (Grade 2C), the addition of clopidogrel to aspirin if the aortic valve is transcatheter (Grade 2C), and VKA therapy with a target international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.5 for mitral valves (Grade 2C). After 3 months, we suggest aspirin therapy (Grade 2C). We recommend early bridging of mechanical valve patients to VKA therapy with unfractionated heparin (DVT dosing) or low-molecular-weight heparin (Grade 2C). We recommend long-term VKA therapy for all mechanical valves (Grade 1B): target INR 2.5 for aortic (Grade 1B) and 3.0 for mitral or double valve (Grade 2C). In patients with mechanical valves at low bleeding risk, we suggest the addition of low-dose aspi-rin (50-100 mg/d) (Grade 1B). In valve repair patients, we suggest aspirin therapy (Grade 2C). In patients with thrombosed prosthetic valve, we recommend fi brinolysis for right-sided valves andleft-sided valves with thrombus area , 0.8 cm 2 (Grade 2C). For patients with left-sided prosthetic valve thrombosis and thrombus area Ն 0.8 cm 2, we recommend early surgery (Grade 2C). C onclusions: T hese antithrombotic guidelines provide recommendations based on the optimal balance of thrombotic and hemorrhagic risk. C HEST 2012; 141(2)(Suppl):e576S–e600SA bbreviations: A F 5 atrial fi brillation; APA 5 antiplatelet agent; AVR 5 aortic valve replacement; GRADE 5 Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; ICH 5 intracerebral hemorrhage; IE 5 infective endocarditis; INR 5 international normalized ratio; LMWH 5 low-molecular-weight heparin; MAC 5 mitral annular calcifi cation; MVP 5 mitral valve prolapse; NBTE 5 nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis; NYH A 5 New York H eart Association; OAC 5 oral anticoagulation; PFO 5 patent foramen ovale; PICO 5 population, intervention, comparator, and outcome; PMBV 5 percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy; PVE 5 prosthetic valve endocarditis; PVT 5 prosthetic valve thrombosis; RCT 5 randomized controlled trial; RR 5 relative risk; TEE 5 transesophageal echocardiography; TIA 5 transient ischemic attack; UFH 5 unfractionated heparin; VKA 5 vitamin K antagonistfor Valvular DiseaseAntithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesR ichard P . W hitlock ,M D ;J ack C. S un ,M D ;S tephen E. F remes ,M D ,F CCP ;F raser D. R ubens ,M D ;and K evin H. T eoh ,M Dthe presence of atrial fi brillation or previoussystemic embolism, we recommend VKA therapy (target IN R, 2.5; range, 2.0-3.0) over no VKA therapy (Grade 1A) .2.1.1. For patients being considered for percu-taneous mitral balloon valvotomy (PMBV) with preprocedural transesophageal echocardiog-raphy (TEE) showing left atrial thrombus, we recommend postponement of PMBV and that VKA therapy (target INR,3.0; range, 2.5-3.5) be administered until thrombus resolution is docu-mented by repeat TEE over no VKA therapy (Grade 1A) .2.1.2. For patients being considered for PMBV with preprocedural TEE showing left atrial thrombus, if the left atrial thrombus does not resolve with VKA therapy, we recommend that PMBV not be performed (Grade 1A) .6.2.1. In patients with asymptomatic patent fora-men ovale (PFO) or atrial septal aneurysm, we suggest against antithrombotic therapy (Grade 2C) .6.2.2. In patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO or atrial septal aneurysm, we recommend aspirin (50-100 mg/d) over no aspirin (Grade 1A) .6.2.3. In patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO or atrial septal aneurysm, who experience recurrent events despite aspirin therapy, we suggest treatment with VKA therapy (target IN R, 2.5; range, 2.0-3.0) and consideration of device closure over aspirin therapy (Grade 2C) .6.2.4. In patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO, with evidence of DVT, we recommend VKA therapy for 3 months (target IN R, 2.5; range, 2.0-3.0) (Grade 1B) and consideration of device closure over no VKA therapy or aspirin therapy (Grade 2C) .7.1.1. In patients with infective endocarditis (IE), we recommend against routine anticoagu-lant therapy, unless a separate indication exists (Grade 1C) .7.1.2. In patients with IE, we recommend against routine antiplatelet therapy, unless a separate indication exists (Grade 1B) .7.2. In patients on VKA for a prosthetic valve who develop IE, we suggest VKA be discontin-ued at the time of initial presentation until it is clear that invasive procedures will not be required and the patient has stabilized without signs of CNS involvement. When the patient isR evision accepted August 31, 2011 . A ffi liations: From McMaster University (Drs Whitlock and Teoh), H amilton, ON, Canada; the University of Washington School of Medicine (Dr Sun), Seattle, WA; the Sunnybrook Hos-pital (Dr Fremes), University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; and the Ottawa H eart Institute (Dr Rubens), Ottawa, ON, Canada .F unding/Support: The Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines received support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [R13 HL104758] and Bayer Schering Pharma AG. Support in the form of educational grants was also provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb; Pfi zer, Inc; Canyon Pharmaceuticals; and sanofi -aventis US.D isclaimer: American College of Chest Physician guidelines are intended for general information only, are not medical advice, and do not replace professional medical care and physician advice, which always should be sought for any medical condition. The complete disclaimer for this guideline can be accessed at /content/141/2_suppl/1S.C orrespondence to: Richard P. Whitlock, MD, Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University, David Braley Cardiac, Vascular, and Stroke Research Institute, 237 Barton St East, Room C1-114, Hamilton, ON, L8L 2X2, Canada; e-mail: richard.whitlock@phri.ca© 2012 American College of Chest Physicians.Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians ( h ttp:///site/misc/reprints.xhtml ).D OI: 10.1378/chest.11-2305 S ummary of Recommendat ionsNote on Shaded Text: Throughout this guideline,shading is used within the summary of recommenda-tions sections to indicate recommendations that are newly added or have been changed since the pub-lication of Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Recommendations that remain unchanged are not shaded.2.0.1. In patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease and normal sinus rhythm with a left atrial diameter , 55 mm we suggest not using anti-platelet or vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy (Grade 2C).2.0.2. In patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease and normal sinus rhythm with a left atrial diameter . 55 mm, we suggest VKA therapy (target international normalized ratio [IN R], 2.5; range, 2.0-3.0) over no VKA therapy or anti-platelet (Grade 2C) .2.0.3. For patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease complicated by the presence of left atrial thrombus, we recommend VKA therapy (target INR, 2.5; range, 2.0-3.0) over no VKA therapy (Grade 1A).2.0.4. For patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease complicated singly or in combination bygest target INR 3.0 (range 2.5-3.5) over target INR 2.5 (range 2.0-3.0) (Grade 2C) .9.6. In patients with a mechanical mitral or aor-tic valve at low risk of bleeding, we suggest add-ing over not adding an antiplatelet agent such as low-dose aspirin (50-100 mg/d) to the VKA therapy (Grade 1B) .R emarks: Caution should be used in patients at increased bleeding risk, such as history of GI bleeding.9.7. For patients with mechanical aortic or mitral valves we recommend VKA over anti-platelet agents (Grade 1B) .10.1. In patients undergoing mitral valve repair with a prosthetic band in normal sinus rhythm, we suggest the use of antiplatelet therapy for the fi rst 3 months over VKA therapy (Grade 2C) .10.2. In patients undergoing aortic valve repair, we suggest aspirin at 50 to 100 mg/d over VKA therapy (Grade 2C) .11.1. For patients with right-sided prosthetic valve thrombosis (PVT), in the absence of contraindications we suggest administration of fi brinolytic therapy over surgical intervention (Grade 2C) .11.2.1. For patients with left-sided PVT and large thrombus area ( Ն 0.8 cm 2), we suggest early surgery over fi brinolytic therapy (Grade 2C) . If contraindications to surgery exist, we suggest the use of fi brinolytic therapy (Grade 2C) .11.2.2. For patients with left-sided PVT and small thrombus area ( , 0.8 cm 2), we suggest administration of fi brinolytic therapy over sur-gery. For very small, nonobstructive throm-bus we suggest IV UFH accompanied by serial Doppler echocardiography to document throm-bus resolution or improvement over other alter-natives (Grade 2C) .T hromboembolic complications of valvular heart disease are often devastating. Antithrombotic therapy can reduce the risk of thromboembolism, but at the cost of increased bleeding. This article seeks to provide recommendations based on the optimal bal-ance of these competing factors. T able 1 describes the population, intervention, comparator, and outcome (PICO) elements for the questions addressed in this article and the design of the studies used to address them. We defi ne onlydeemed stable without contraindications or neurologic complications, we suggest reinsti-tution of VKA therapy (Grade 2C).7.3. In patients with nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis and systemic or pulmonary emboli, we suggest treatment with full-dose IV unfrac-tionated heparin (UFH) or subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) over no anticoagulation (Grade 2C) .8.2.1. In patients with aortic bioprosthetic valves, who are in sinus rhythm and have no other indication for VKA therapy, we suggest aspirin (50-100 mg/d) over VKA therapy in the fi rst 3 months (Grade 2C) .8.2.2. In patients with transcatheter aortic bio-prosthetic valves, we suggest aspirin (50-100 mg/d) plus clopidogrel (75 mg/d) over VKA therapy and over no antiplatelet therapy in the fi rst 3 months (Grade 2C) .8.2.3. In patients with a bioprosthetic valve in the mitral position, we suggest VKA therapy (target IN R, 2.5; range, 2.0-3.0) over no VKA therapy for the fi rst 3 months after valve inser-tion (Grade 2C) .8.3. In patients with bioprosthetic valves in nor-mal sinus rhythm, we suggest aspirin therapy over no aspirin therapy after 3 months postop-erative (Grade 2C) .9.1. In patients with mechanical heart valves, we suggest bridging with unfractionated heparin (UFH, prophylactic dose) or LMWH (prophylac-tic or therapeutic dose) over IV therapeutic UFH until stable on VKA therapy (Grade 2C) .9.2. In patients with mechanical heart valves, we recommend VKA therapy over no VKA therapy for long-term management (Grade 1B) .9.3.1 In patients with a mechanical aortic valve, we suggest VKA therapy with a target of 2.5 (range, 2.0-3.0) over lower targets (Grade 2C) .9.3.2. In patients with a mechanical aortic valve, we recommend VKA therapy with a tar-get of 2.5 (range 2.0-3.0) over higher targets (Grade 1B) .9.4. In patients with a mechanical mitral valve, we suggest VKA therapy with a target of 3.0 (range, 2.5-3.5) over lower INR targets (Grade 2C) .9.5. In patients with mechanical heart valves in both the aortic and mitral position, we sug-T able 1— S tructured Clinical QuestionsSectionPICO QuestionMethodology Population Interventions Comparator Outcome2.0 Rheumatic mitral valve2.0.1Normal sinus rhythmand left atrialdiameter ,55 mm Anticoagulationor antiplateletNo anticoagulationor antiplateletThromboembolism Observational studies2.0.2Normal sinus rhythmand left atrialdiameter .55 mmAnticoagulation No anticoagulation Thromboembolism Observational studies2.0.3Presence of leftatrial thrombusAnticoagulation No anticoagulation Thromboembolism Observational studies2.0.4Atrial fi brillation orprevious systemicembolism Anticoagulation No anticoagulation Total mortality,stroke, majorbleeding eventRCT observationalstudies2.1.1Percutaneous mitralballoon valvotomyin presence of leftatrial thrombus Anticoagulationprior toprocedureNo anticoagulationprior toprocedureThromboembolism Observational studies2.1.2Percutaneous mitralballoon valvotomywith nonresolvingleft atrial thrombusPMBV No PMBV Thromboembolism Expert consensus6.0 Aortic atheroma and PFO6.2.1AsymptomaticPFO or atrialseptum aneurysm Anticoagulationor antiplateletNo anticoagulationor antiplateletStroke Observational studies6.2.2Stroke in the presenceof PFO Antiplatelet No antiplatelet Recurrent strokeor deathRCT subgroup data6.2.3Recurrent strokeand PFOAnticoagulation Antiplatelet Recurrent stroke Observational studies6.2.4PFO in presenceof DVT Anticoagulation No anticoagulation Recurrent stoke,pulmonaryembolism, mortalityRCT (indirect)7.0 Endocarditis7.1.1Infectiveendocarditis Anticoagulation No anticoagulation Thromboembolism,intracerebral bleedObservational studies7.1.2Infectiveendocarditis Antiplatelet No antiplatelet Thromboembolism,mortality,major bleedRCT7.2Prosthetic valveendocarditis Anticoagulation No anticoagulation Thromboembolism,bleedingObservational studies7.3Nonbacterialthromboticendocarditis withprior embolismAnticoagulation No anticoagulation Recurrent embolism Observational studies8.0 Bioprosthetic heart valves8.2.1Aortic bioprosthesiswith normalsinus rhythm Anticoagulationfor fi rst 3 moAntiplatelet forfi rst 3 moThromboembolism,mortality, majorbleeding eventRCT8.2.2Transcatheteraortic bioprosthesiswith normalsinus rhythm Anticoagulationin fi rst 3 moAntiplatelet forfi rst 3 moThromboembolism,major bleeding eventObservational studies8.2.3Mitral bioprosthesiswith normalsinus rhythm Anticoagulationin fi rst 3 moNo anticoagulationfor fi rst 3 moThromboembolism,major bleeding eventObservational studies(Continued)continues to consider vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) as the fi rst-line oral anticoagulant until evidence of effi cacy and safety within the valve population is generated. For recommendations on the manage-ment of parenteral anticoagulation (dosing and monitoring), oral anticoagulation (dosing and mon-itoring), and bleeding complications, please referto the article by Holbrook et al2 about management of anticoagulation in this guideline. Finally, therepatient characteristics relevant to our questions. This article does not make recommendations spe-cifi c to atrial fi brillation (AF); for this issue, wedirect you to the article by You et al1on AF in this supplement. In areas of overlap with the AF article, where newer anticoagulants such as dabigatran may be considered for nonvalvular AF, caution must be used when extrapolating their use to the populations described in this article. This articleSection PICO QuestionMethodology Population InterventionsComparatorOutcome9.0 Mechanical heart valves9.1Mechanicalheart valves early postoperative (day 0-5)UFH or LMWH (DVT dosing)IV therapeutic UFHThromboembolism, bleedingObservational studies9.2Mechanical heart valves Long-termanticoagulation No long-term anticoagulation Thromboembolism, valve thrombosis Meta-analysis of observational data 9.3.1Mechanical aortic valve Conventional INR target (2.0-3.0)Lower INR targets Thromboembolism, bleedingRCT 9.3.2Mechanical aortic valve Conventional INR target (2.0-3.0)Higher INR targets Thromboembolism, major bleeding event, mortalityRCT9.4Mechanical mitral valve Conventional INR target (2.5-3.5)Lower INR targets Thromboembolism, major bleeding event, mortality RCT9.5Mechanical aortic and mitral valve INR target 2.5-3.5INR target 2.0 to 3.0MortalityRCT9.6Mechanical heart valvesAntiplatelet in addition to anticoagulationAnticoagulation aloneThromboembolism, mortality, valve thrombosis, major bleeding event Meta-analysis of RCTs10.0 Heart valve repair10.1Mitral valve repair with prosthetic band AntiplateletAnticoagulationThromboembolism, valve thrombosis Observational studies10.2Aortic valve repairAntiplatelet Anticoagulation Thromboembolism, bleedingObservational studies11.0 Prosthetic valve thrombosis11.1Right-sidedprosthetic valve thrombosisFibrinolytic therapy Surgical interventionMortality,hemodynamic success,thromboembolism, bleeding, recurrence of obstruction Observational studies11.2.1Left-sided prostheticvalve thrombosis with thrombus Ն0.8 cm 2Fibrinolytic therapy Surgical intervention Mortality,hemodynamic success,thromboembolism, bleeding, recurrence of obstruction Observational studies11.2.2Left-sided prosthetic valve thrombosis with thrombus ,0.8 cm 2Fibrinolytic therapy Surgical intervention Mortality,hemodynamic success,thromboembolism, bleeding, recurrence of obstructionObservational studiesI NR 5 international normalized ratio; LMWH 5 low-molecular-weight heparin; PFO 5 patent foramen ovale; PICO 5 population, intervention, comparator, and outcome; PMBV 5 percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy; RCT 5 randomized controlled trial; UFH 5 unfractionated heparin.Table 1—ContinuedThe relationship between thromboembolism and left atrial size remains unclear. Early studies 5,13,14ofrheumatic mitral valve disease reported a weak corre-lation. H owever, several studies have now demon-strated an association between larger left atrial size and left atrial thrombus or spontaneous echocardio-graphic contrast. 15-17I n those patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease who suffer a fi rst embolus, recurrent emboli occur frequently (one-third to two-thirds of cases)and early (two-thirds within the fi rst year).5,23-25 A hypercoagulable state in mitral stenosis mightcontribute to the risk of thromboembolism. 26,27 Norandomized trial has been completed in this popu-lation, but observational data suggest that the risk of recurrent emboli may be reduced by VKA therapy. Szekely 7 found a recurrence rate of 9.6%/y with no anticoagulation and 3.4%/y with warfarin (relative risk [RR], 0.36; 95% CI, 0.08-1.6). Similar estimateshave been reported by others. 14,28Among patients with mitral stenosis and left atrial thrombus on transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), VKA therapy results in a 62% thrombus disappearance over anaverage of 34 months. 29T he onset of AF increases the risk of systemic embolization in patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease.7,13 As in those with recurrent embolism, observational studies suggest a large decrease in riskwith warfarin administration. 13,30Indirect evidencefrom randomized trials in nonvalvular AF provide further support for the impact of warfarin in the pre-vention of thromboembolism in patients with rheu-matic mitral valve with AF. R ecommendations2.0.1. In patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease and normal sinus rhythm with a left atrial diameter , 55 mm, we suggest not using anti-platelet or VKA therapy (Grade 2C) .2.0.2. In patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease and normal sinus rhythm with a left atrial diameter . 55 mm, we suggest VKA ther-apy (target IN R, 2.5; range, 2.0-3.0) over no VKA therapy or antiplatelet (Grade 2C) .2.0.3. For patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease complicated singly or in combination by the presence of left atrial thrombus, we recom-mend VKA therapy (target IN R, 2.5; range, 2.0-3.0) over no VKA therapy (Grade 1A) .2.0.4. For patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease complicated singly or in combination by the presence of AF or previous systemic embolism, we recommend VKA therapy (targetare very few data directly addressing the antithrom-botic management of right-sided prosthetic valves. Indirect evidence from mitral and aortic valves pro-vides the best evidence and the basis for recommen-dations regarding tricuspid and pulmonic prostheses.1.0 M ethodsT he development of the current recommendations followed the general approach of Methodology for the Development of Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Guide-lines. Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-BasedClinical Practice Guidelines. 3 In brief, literature searches to updatethe existing database from the AT8 guidelines were performed (January 1, 2005 to October 2009). The literature was rated according to the Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework. The panel considered quality of information, balance of risk and harm, and patients’ values and preferences to determine the strength of recommendation.I n making recommendations, we have taken a p rimum non nocere approach, placing the burden of proof with those who would claim a benefi t of treatment. In other words, when there is uncertain benefi t and an appreciable probability of important harm associated with treatment, we recommend against such treatments.T he value given to the harmful effect of an extracranial bleeding event (as compared with that of valve thrombosis, peripheral thromboembolism, or stroke) greatly impacts the balance of ben-efi ts and harms of a given therapy. There are limited data to guide us with respect to the relative value of these outcomes. For this article, we used the result of the preference-weighting exercisecarried out by MacLean et al4 as part of these guidelines, which attributes approximately three times the disutility (aversiveness, negative weight) to a stroke vs an extracranial bleeding event; a valve thrombosis carries slightly greater disutility than an extra-cranial bleeding event.2.0 R heumatic M itral V alve D isease Rheumatic mitral valve disease carries the great-est risk of systemic thromboembolism of any com-mon form of acquired valvular disease. Wood 5citeda prevalence of systemic emboli of 9% to 14% in several large early series of patients with mitralstenosis. In 1961, Ellis and H arken 6reported that27% of 1,500 patients undergoing surgical mitral valvotomy had a history of clinically detectable sys-temic emboli. Among 754 patients followed up for5,833 patient-years, Szekely 7observed an incidenceof emboli of 1.5% per year, whereas the number was found to vary from 1.5% to 4.7% per year preopera-tively in six reports of rheumatic mitral valve disease. 8Although the risk may increase in the elderly andthose with lower cardiac indices, 9-12these findings have been inconsistent across studies. 5,13-21Other characteristics that may increase the risk of systemic embolism include the presence of a left atrial throm-bus and signifi cant aortic regurgitation. 22people with MVP had an excess lifetime risk of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) (RR, 2.2; P , .001). Thus, it is as yet unclear whether MVP truly increased the risk of thromboembolic process. Mitral valve strands, also known as Lambl’s excres-cences, have also been implicated as a potential embolic source, but they do not seem to increasethe risk of stroke recurrence.44We therefore sug-gest that patients with MVP or strands who have not experienced systemic embolism, unexplained TIAs, or ischemic stroke, and do not have evident vascular disease should be managed as other patients considering primary prevention of vascular events. Given the risk of bleeding complications with anticoagulation and the lack of data to demon-strate a benefi t in terms of reducing (recurrent) thromboembolic events, patients with MVP or strands and a history of ischemic stroke or TIA should be treated with antiplatelet agents follow-ing the recommendations by Landsberg et al 45 forpatients with noncardioembolic stroke. In those patients with MVP or strands who have recurrent thromboembolic events despite antiplatelet agent (APA) therapy, the likelihood of a cardiac source increases.4.0 Mitral Annular Calcification M itral annular calcifi cation (MAC), like MVP , may be a source of cardioembolic stroke. The best esti-mate of the embolic potential of MAC comes fromthe Framingham H eart Study. 46 Among 1,159 indi-viduals with no history of stroke at the index echo-cardiographic examination, the risk of stroke inthose with MAC was 2.1 times greater than those without MAC (5.1% without MAC vs 13.8% with MAC, P 5 .006), independent of traditional risk factors for stroke. There was a continuous relation-ship between the risk of stroke and the severity of the MAC. A major issue in this condition is that emboli may represent thrombus or calcifi c spic-ules, the latter of which antithrombotic therapywill not prevent. 46-48From the available literature,we suggest that patients with MAC who have not experienced systemic embolism, unexplained TIAs, or ischemic stroke, and do not have evident vas-cular disease should be managed as other patients considering primary prevention of vascular events. It would be reasonable to manage patients with MAC and evidence of thromboembolic process with no other identifi able source as patients withTIAs without MAC. 45 Failure of this antithrombotictherapy or evidence of multiple calcifi c emboli should prompt consideration of valve replacement.INR, 2.5; range, 2.0-3.0) over no VKA therapy (Grade 1A) . 2.1 Patients With Rheumatic Mitral Valve Disease Undergoing Percutaneous Mitral Balloon Valvotomy During the percutaneous mitral balloon valvot-omy (PMBV) procedure, when the catheter is pushed through the septum it often goes into the left atrial appendage, the usual site of thrombus. Thus, the presence of left atrial thrombus precludes PMBV. Accurate detection of thrombus requires atransesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). Silaruks et al 31have demonstrated that 24.2% of left atrial thrombi will resolve within 6 months of anticoagulation. Further,Kang et al 32 have demonstrated that after thrombusresolution, PMBV can be safely performed. Predic-tors of thrombus resolution are New York H eart Association (NYHA) functional class II or better, leftatrial appendage thrombus size Յ1.6 cm 2, less dense spontaneous echocardiographic contrast, and an INR Ն 2.5. Patients with all of these predictors had a 94.4% chance of complete thrombus resolutionat 6 months. 31I n those patients without left atrial thrombus and no other indication for anticoagulation, Abraham et al 33demonstrated PMBV can be performed in the absence of anticoagulation, with no patients in 629 procedures performed having an embolism within 3 months post procedure. R ecommendations 2.1.1. For patients being considered for PMBV with preprocedural TEE showing left atrial thrombus, we recommend postponement of PMBV and that VKA therapy (target INR, 3.0; range, 2.5-3.5) be administered until thrombus resolution is documented by repeat TEE over no VKA therapy (Grade 1A) .2.1.2. For patients being considered for PMBV with preprocedural TEE showing left atrial thrombus, if the left atrial thrombus does not resolve with VKA therapy, we recommend that PMBV not be performed (Grade 1A ).3.0 Mitral Valve Prolapse and Mitral Valve StrandsMitral valve prolapse (MVP) is a common con-genital form of valve disease. Although early evi-dence from case series and control studies suggestedan association with stroke, 34-40 Gilon et al 41and the Framingham Heart Study 42 failed to replicate theresults. More recently, Avierinos et al 43found that。

美国胸科医师协会第九版抗栓治疗及血栓预防指南静脉血栓栓塞性疾病最新进展周玉杰, 杨士伟(首都医科大学附属北京安贞医院 心内科12病房,北京 100029)通讯作者:周玉杰 E-mail:jackydang@静脉血栓栓塞性疾病(venous thromboembolism ,VTE )包括深静脉血栓(deep venous thrombosis ,DVT )和肺栓塞(pulmonary embolism ,PE )。

近日,美国胸科医师协会(American College of Chest Physicians ,ACCP )在Chest 杂志上公布了第9版《抗栓治疗及血栓预防指南》(ACCP-9)[1-4]。

此版指南在第8版基础上,结合最新循证医学证据,对抗栓治疗进行了全面细致的推荐。

本文将结合ACCP-9对VTE 的最新进展进行阐述。

1 病因与诱因Virchow 于1856年提出了导致静脉血栓形成的三因素假说:静脉血流淤滞、血管损伤和高凝状态。

经过大量试验证实,该假说目前已得到了公认。

许多参与上述过程的临床情况均可诱发静脉血栓形成,主要包括:(1)肢体制动:各种疾病导致的长时间卧床或肢体制动,如急性心肌梗死、主要脏器功能衰竭、脑卒中、大型手术后等;(2)静脉受压:如股动脉或静脉穿刺术后压迫止血导致下肢静脉回流受阻,妊娠、腹腔巨大肿瘤或大量腹水导致盆腔静脉或下腔静脉回流受阻等;(3)静脉曲张:主要是指深静脉曲张,浅静脉曲张一般不会导致血栓形成;(4)静脉损伤:如外伤或手术累及静脉、静脉穿刺、静脉炎等;(5)高凝状态:各种遗传性或获得性血栓形成倾向,如抗凝因子缺乏(抗凝血酶Ⅲ、C 蛋白或S 蛋白最常见)、弥漫性血管内凝血(disseminated intravascular coagulation ,DIC )、抗磷脂综合征、肾病综合征、恶性肿瘤、大量呕吐或腹泻导致的脱水、药物因素(长期口服避孕药、激素或抗肿瘤药物)等;(6)其他:如高龄、吸烟、肥胖等。

第九版美国胸科医师协会抗栓与血栓预防实践指南汇总二十余篇ACCP-9抗栓溶栓指南原文完整版下载地址: /bbs/topic/22270927翻译来自 丁香园 李慕白的强力之作:/topic/special/20120309/accp2012.htm抗栓热点CHEST :第9版《美国胸科医师协会抗栓与血栓预防临床实践指南》之房颤的抗栓治疗不同的心房颤动(AF )患者卒中风险差别很大。

而抗血栓治疗来预防卒中会相应地增加出血的风险。

因此,美国胸科医师协会根据第9版临床实践指南的方法论(Methodologyfor the Development of Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of ThrombosisGuidelines ),并基于临床净获益和大量的临床实例为不同卒中风险的房颤患者提供了抗血栓治疗的推荐。

对非风湿性房颤(包括间歇性房颤)的患者:1)低度卒中危险(CHADS2评分=0)(CHADS2评分是指充血性心力衰竭、高血压病、年龄>75岁、糖尿病、卒中或短暂性缺血发作病史,前面4项危险因素各为1分,最后一项为2分),建议无需抗栓治疗;对于选择抗栓治疗的患者,建议单用阿司匹林而不是口服抗凝药或阿司匹林和氯吡格雷联合治疗。

2)中度卒中危险(CHADS2评分=1),推荐口服抗凝药而不是不用药,并建议单用口服抗凝药而不是阿司匹林或阿司匹林和氯吡格雷联合治疗。

3)高度卒中危险(CHADS2评分≥2),推荐口服抗凝药,而不是不用药、单用阿司匹林或阿司匹林和氯吡格雷联合治疗。

上述推荐或建议的口服抗凝药,其建议达比加群150毫克 每日2次,而不是剂量调整维生素K 拮抗剂。

因此,对于具有高危卒中风险(CHADS2得分≥2)的房颤患者,口服抗凝药是抗栓治疗的最佳选择。

而对于卒中风险较低的房颤患者,抗栓治疗需要更为个体化。

CHEST :第9版《ACCP 临床实践指南》之缺血性卒中的抗栓和溶栓治疗指南为卒中和短暂性脑缺血发作(TIA )患者提供了抗栓治疗推荐,有助于临床医生对卒中患者做出循证治疗决策。