美国意思协会-CKD指南

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:1.47 MB

- 文档页数:14

慢性肾脏病患者高钾血症的诊治及管理肾脏是调控人体钾代谢的重要脏器。

慢性肾脏病(CKD)在我国的发病率高达10.8%,不少CKD患者都合并有不同程度的钾代谢失衡,高钾血症也成为CKD患者常见的并发症。

正确识别急、慢性高钾血症并及时进行降钾治疗,同时进行行之有效的长效管理是我们面临的一项重要课题。

高钾血症定义的变迁目前我国定义血钾正常范围为3.5~5.5mmol∕L,而国外较多文献及指南已将血钾正常值上限降低至5.0mmol∕L o高钾血症诊断标准的前移,有助于对CKD患者高钾血症的早期发现、早期干预和早期管理。

急、慢性高钾血症理念更新根据血钾升高的速度及造成的危害,将高钾血症分为急、慢性两种,两者的治疗目的及措施均有差异。

如血钾在短期内升至6.0mmol∕L或以上,或有高钾引起心电图变化属于危重症,需要紧急处理,治疗目的是尽快将血钾回降至安全水平;而部分CKD患者同时合并糖尿病、心功能不全等危险因素,或长期服用含钾/潴钾药物,容易反复出现高钾血症,需要进行长期预防管理。

急性高钾血症的处理对于急性高钾血症患者,通常需要立即进行生命体征监护及心电图检查,无论是否伴心电图改变均建议立即使用钙剂稳定心肌,可选择葡萄糖酸钙或氯化钙静脉推注(氯化钙需要使用中心静脉通路)。

其他常用紧急降钾措施:(1)促进钾离子转移至细胞内。

静脉注射葡萄糖和胰岛素,促进钾离子向细胞内转运。

葡萄糖的浓度与容量以及胰岛素的剂量配比需要考虑患者心功能、尿量和血糖水平,按照1单位胰岛素对消4g葡萄糖配比,如5%葡萄糖500ml中加入普通胰岛素6单位静脉滴注;容量过负荷的患者可予以25%葡萄糖40ml加入普通胰岛素3单位静脉推注。

碳酸氢钠与沙丁胺醇喷雾剂也有促进钾离子向细胞内转移的作用,但效果有限。

(2)促进钾离子排泄。

对于非少尿且血容量稳定患者可使用伴利尿剂促进钾离子从尿液中排出,也可同时联合睡嗪类利尿剂。

阳离子交换树脂(如聚苯乙烯磺酸钠、聚苯乙烯磺酸钙)及新型钾离子结合剂(如PatirOmer、环硅酸错钠)可减少肠道内钾离子吸收并促进其从粪便中排出,从而使血钾降低。

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) doctor discussion guideBring this list to your next appointment to guide your discussion about CKD. Through frequent, unfiltered conversations, you’ll learn how to feel more in control and help your support system discover how to help you on your CKD journey.CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE (CKD)• What caused my CKD?• Do genetics play a role in CKD? Is my family at risk?• Can my CKD be cured?• What do I need to know about CKD and what should I expect next?• Are there steps I can take to help slow the progression of CKD and prevent kidney failure? • What symptoms should I look out for to help monitor my kidney function? How can I tell if it’s getting worse?• Will I need dialysis or a kidney transplant?• How much will my treatment cost and what financial resources are available to me?TWO POTENTIALLY SERIOUS CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH CKD• Hyperkalemia: Hyperkalemia or high potassium is when the blood has higher than normal potassium levels, which may cause symptoms such as muscle weakness, numbness or tingling, or irregular heartbeat. However, many patients do not experience symptoms so it is important to speak about hyperkalemia with your doctor.• How does high potassium in my body impact me?• What should my potassium level be and how can I find out my current potassium level?• If my level is off, what should be my goal and what treatment, medication or lifestyleoptions do I have to help me achieve it?• Anemia: Anemia is a condition in which the body doesn’t have enough red blood cells. These cells contain hemoglobin (Hb) which carries oxygen throughout your body. When your body is deprived of oxygen, it can leave you feeling drained or exhausted, both physically and mentally.• Can you help me understand what hemoglobin (Hb) is? What is its relationshipwith anemia?• What should my Hb level be and how can I find out my current Hb level?• If my level is off, what should be my goal and what treatment, medication or lifestyleoptions do I have to help me achieve it?weakness body aches chest pain headaches sleep problems trouble concentrating muscle pains or crampsother NOTES / ADDITIONAL QUESTIONS。

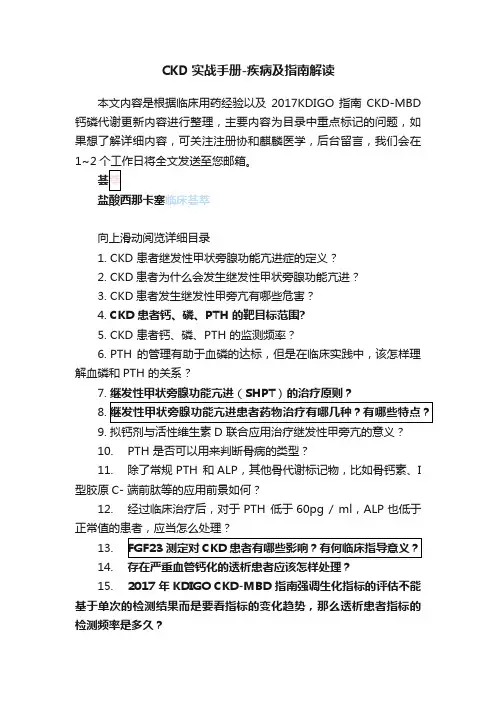

CKD实战手册-疾病及指南解读本文内容是根据临床用药经验以及2017KDIGO指南CKD-MBD 钙磷代谢更新内容进行整理,主要内容为目录中重点标记的问题,如果想了解详细内容,可关注注册协和麒麟医学,后台留言,我们会在1~2临床荟萃向上滑动阅览详细目录1.CKD 患者继发性甲状旁腺功能亢进症的定义?2.CKD患者为什么会发生继发性甲状旁腺功能亢进?3.CKD患者发生继发性甲旁亢有哪些危害?4.CKD 患者钙、磷、PTH 的靶目标范围?5.CKD 患者钙、磷、PTH 的监测频率?6.PTH 的管理有助于血磷的达标,但是在临床实践中,该怎样理解血磷和PTH 的关系?7.继发性甲状旁腺功能亢进(SHPT)的治疗原则?8.9.10.PTH 是否可以用来判断骨病的类型?11.除了常规PTH 和ALP,其他骨代谢标记物,比如骨钙素、I 型胶原C- 端前肽等的应用前景如何?12.经过临床治疗后,对于PTH 低于60pg / ml,ALP也低于正常值的患者,应当怎么处理?13.14.15.2017 年KDIGO CKD-MBD 指南强调生化指标的评估不能基于单次的检测结果而是要看指标的变化趋势,那么透析患者指标的检测频率是多久?16.2017 年KDIGO CKD-MBD 指南推荐 CKD 3-5D 期患者降磷治疗的时机是进行性持续性的血磷升高,那么这个进行性持续性的定义是什么?17.2017 年KDIGO CKD-MBD 指南强调活性维生素D及其类似物应用需要更加谨慎,但在我国活性维生素D 的应用十分广泛,如何理解二者间的差异?18.2017 年KDIGO CKD-MBD 指南更新强调血钙、血磷、iPTH 等生化指标综合考虑,但较少涉及临床症状的评估,在临床实践中遇到生化指标与临床症状不符合的情况,在这种情况下如何进行治疗决策?19.CKD-MBD 患者基于不同血钙血磷水平的治疗策略?01-问题4CKD3-5D期钙、磷靶目标范围推荐备注:1. 在CKD3-5 期非透析患者中最佳的PTH 的水平目前尚不清楚,需要对这些患者PTH 水平进行早期监测和动态评估。

美国内分泌医师协会血脂异常与动脉粥样硬化预防管理指南(全文)在美国,每年约785 000人新发冠心病(CAD),约470 000人再发CAD。

美国平均每6个死亡病例中有1例死于CAD。

尽管脑卒中发生率下降,但美国2007年的死亡数据显示每18个死亡病例中有1例死于脑卒中。

血脂异常是CAD最主要的危险因素,甚至是CAD的首要条件。

流行病学资料也显示高胆固醇血症以及冠状动脉粥样硬化是缺血性脑卒中的危险因素[1]。

近30年血脂水平趋势分析显示总胆固醇(TC)以及低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(LDL-C)水平有所改善,但69%的美国成人其LDL-C水平超过100 mg/dl;而且,肥胖以及高甘油三酯血症(33%)的发生率成倍增加,因此需要内科医生继续努力降低心血管疾病(CVD)的风险。

美国内分泌医师协会(AACE)制定了“血脂异常与动脉粥样硬化预防管理指南”。

该临床应用指南(CPGs)用于血脂异常的诊断和治疗,以及动脉粥样硬化的预防。

该CPGs提供给内分泌医师实际工作指导,用以降低血脂异常的风险以及不良后果。

该CPGs是在由AACE撰写的“血脂异常的诊断和治疗以及动脉粥样硬化的预防”临床应用指南的基础上进行扩展及更新[2]。

该CPGs首次提出检测apoB或低密度脂蛋白颗粒以便更有效地降低LDL-C。

同时还提出对不同年龄人群的检测建议,强调儿科病人的特殊事项,以及首次提出女性动脉粥样硬化和心脏病所面临的挑战。

该CPGs仍强调降低LDL-C的重要性,并赞成在某些情况下可以通过检测炎性标记物进行危险分层。

该CPGs的内容包括以下三大方面:①检测项目推荐、危险评估以及不同类型脂质异常的治疗推荐;②对特殊人群的关注,如患有血脂异常的糖尿病患者、女性以及儿科患者;③评价不同调脂治疗的费效比。

该CPGs 是以针对临床提出的问题进行问答的形式撰写的。

1 血脂异常的检测首先确定危险因素并进行危险程度分级[3,4],以便进行个体化治疗,并达到最佳治疗效果。

2022年ADA糖尿病诊疗指南之慢性肾脏病近期美国糖尿病学会推出2022 年糖尿病诊疗指南。

我们将就其中的慢性肾脏病(chronic kidney disease, CKD)章节展开讨论。

CKD 通过尿白蛋白排泄量(白蛋白尿)持续升高、eGFR 降低或其他肾脏损害表现来诊断。

归因于糖尿病的CKD (Diabetic Kidney Disease, DKD) 通常在 1 型糖尿病患者的糖尿病病程 10 年后发生,但也可能在诊断为 2 型糖尿病时出现。

CKD 可发展为需要透析或肾移植的终末期肾病 (ESRD)。

CKD 也显着增加心血管风险。

筛查指南推荐,在病程超过 5 年的 1 型糖尿病患者以及所有 2 型糖尿病患者中,应该至少每年查一次尿白蛋白肌酐比(urine albumin creatinine ratio, UACR)以及估计肾小球滤过率(eGFR)。

而对于已知糖尿病且UACR≥300 mg/g 和/或 eGFR 30-60 mL/min/1.73m2 的患者,应至少每年检查两次。

DKD 的诊断和分期糖尿病肾病的诊断及分期是基于白蛋白尿的出现、严重程度及eGFR 降低,且需要排除其他可以造成肾脏损害的原发病因。

在3-6 个月期间,3 次 UACR 检测中有 2 次异常可以考虑患者有白蛋白尿。

对于 eGFR 的计算,目前仍推荐 CKD-EPI 公式。

治疗建议1. 推荐使用钠-葡萄糖协同转运子 2(SGLT2)抑制剂对于预防以及延缓糖尿病患者 CKD 进展的关键步骤就是最优化血糖管理,以及血压控制、降低血压变异率。

而对于已患有2 型糖尿病合并糖尿病肾病,并且化验发现eGFR≥25 mL/min/1.73m2 且UACR≥300 mg/g 的患者,指南推荐使用钠-葡萄糖协同转运子2(SGLT2)抑制剂来延缓 CKD 进展以及减少心血管事件的发生。

略有不同的是,对于患有2 型糖尿病合并CKD 的患者,当eGFR≥25 mL/min/1.73m2 或UACR≥300 mg/g 时,可以考虑加用SGLT2 抑制剂来降低心血管风险。

Screening,Monitoring,and Treatment of Stage 1to 3Chronic Kidney Disease:A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of PhysiciansAmir Qaseem,MD,PhD,MHA;Robert H.Hopkins Jr.,MD;Donna E.Sweet,MD;Melissa Starkey,PhD;and Paul Shekelle,MD,PhD,for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians*Description:The American College of Physicians (ACP)developed this guideline to present the evidence and provide clinical recom-mendations on the screening,monitoring,and treatment of adults with stage 1to 3chronic kidney disease.Methods:This guideline is based on a systematic evidence review evaluating the published literature on this topic from 1985through November 2011that was identified by using MEDLINE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.Searches were limited to English-language publications.The clinical outcomes evaluated for this guideline included all-cause mortality,cardiovascular mor-tality,myocardial infarction,stroke,chronic heart failure,composite vascular outcomes,composite renal outcomes,end-stage renal dis-ease,quality of life,physical function,and activities of daily living.This guideline grades the evidence and recommendations by using ACP’s clinical practice guidelines grading system.Recommendation 1:ACP recommends against screening for chronic kidney disease in asymptomatic adults without risk factors for chronic kidney disease.(Grade:weak recommendation,low-quality evidence)Recommendation 2:ACP recommends against testing for protein-uria in adults with or without diabetes who are currently taking an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin II–receptor blocker.(Grade:weak recommendation,low-quality evidence)Recommendation 3:ACP recommends that clinicians select phar-macologic therapy that includes either an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (moderate-quality evidence)or an angiotensin II–receptor blocker (high-quality evidence)in patients with hyperten-sion and stage 1to 3chronic kidney disease.(Grade:strong recommendation)Recommendation 4:ACP recommends that clinicians choose statin therapy to manage elevated low-density lipoprotein in patients with stage 1to 3chronic kidney disease.(Grade:strong recommenda-tion,moderate-quality evidence)Ann Intern Med.2013;159: For author affiliations,see end of text.This article was published online first at on 22October 2013.Chronic kidney disease (CKD)is nearly always asymp-tomatic in its early stages (1).The most commonly accepted definition of CKD was developed by Kidney Dis-ease:Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)(2)and the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI)(3)as abnormalities of kidney structure or function,present for more than 3months,with implications for health.Cri-teria for CKD include markers of kidney damage (albu-minuria,as indicated by an albumin excretion rate of 30mg/24h or greater and an albumin–creatinine ratio of 3mg/mmol or greater [Ն30mg/g]);urine sediment abnor-malities;electrolyte and other abnormalities due to tubular disorders;abnormalities detected by histologic examina-tion;structural abnormalities detected by imaging;history of kidney transplantation or presence of kidney damage;or kidney dysfunction that persists for 3or more months,as shown by structural and functional abnormalities (most often based on increased albuminuria,as indicated by a urinary albumin–creatinine ratio of 3mg/mmol or greater[Ն30mg/g])or a glomerular filtration rate (GFR)less than 60mL/min/1.73m 2for 3or more months.Traditionally,CKD is categorized into 5stages that are based on disease severity defined by GFR (3)(Table 1);stages 1to 3are considered to be early-stage CKD.People with early stages of the disease are typically asymptomatic,and the diagnosis is made by using laboratory tests or im-aging.In 2013,KDIGO revised CKD staging to consider both 5stages of GFR as well as 3categories of albuminuria to define CKD severity (2).*This paper,written by Amir Qaseem,MD,PhD,MHA;Robert H.Hopkins Jr.,MD;Donna E.Sweet,MD;Melissa Starkey,PhD;and Paul Shekelle,MD,PhD,was developed for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians.Individuals who served on the Clinical Guidelines Committee from initiation of the project until its approval were Paul Shekelle,MD,PhD (Chair );Roger Chou,MD;Molly Cooke,MD;Paul Dallas,MD;Thomas D.Denberg,MD,PhD;Nick Fitterman,MD;Mary Ann Forciea,MD;Robert H.Hopkins Jr.,MD;Linda L.Humphrey,MD,MPH;Tanveer P.Mir,MD;Douglas K.Owens,MD,MS;Holger J.Schu ¨nemann,MD,PhD;Donna E.Sweet,MD;and Timothy Wilt,MD,MPH.Approved by the ACP Board of Regents on 17November 2012.See also:PrintSummary for Patients.......................I-28Web-Only CMEquiz©2013American College of Physicians 835Approximately 11.1%(22.4million)of adults in the United States have stage 1to 3CKD,and prevalence ap-pears to be increasing,especially for stage 3CKD (4,5).Approximately one half of persons with CKD have either stage 1or 2CKD (increased albuminuria with normal GFR),and one half have stage 3CKD (low GFR,with one third of these individuals having increased albuminuria and two thirds having normal albuminuria)(5).The prevalence of CKD is slightly higher in women than in men (12.6%vs.9.7%)(6).Stage 1to 3CKD,reduced GFR,and albuminuria are associated with mortality (7,8),cardiovascular disease (9),fractures (10),bone loss (11),infections (12),cognitive impairment (13),and frailty (14).Treatment of stage 1to 3CKD involves treating associated conditions and compli-cations.Many patients with CKD may already be taking medications targeting comorbid conditions,such as hyper-tension,cardiovascular disease,and diabetes.This American College of Physicians (ACP)guideline presents available evidence on the screening,monitoring,and treatment of stage 1to 3CKD.Clinicians are the target audience.The target patient population for screen-ing is adults,and the target population for treatment it is adults with stage 1to 3CKD.M ETHODSThis guideline is based on a systematic evidence review sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)(15)and conducted by the Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center (6)that addressed the fol-lowing key questions:1.In asymptomatic adults with or without recognized risk factors for CKD incidence,progression,or complica-tions,what direct evidence is there that systematic CKD screening improves clinical outcomes?2.What harms result from systematic CKD screening in asymptomatic adults with or without recognized risk factors for CKD incidence,progression,or complications?3.Among adults with CKD stages 1to 3,whether detected by systematic screening or as part of routine care,what direct evidence is there that monitoring for worseningkidney function or kidney damage improves clinical outcomes?4.Among adults with CKD stages 1to 3,whether detected by systematic screening or as part of routine care,what harms result from monitoring for worsening kidney function or kidney damage?5.Among adults with CKD stages 1to 3,whether detected by systematic screening or as part of routine care,what direct evidence is there that treatment improves clin-ical outcomes?6.Among adults with CKD stages 1to 3,whether detected by systematic screening or as part of routine care,what harms result from treatment?The literature search identified randomized,controlled trials and controlled clinical trials published in English from 1985through November 2011,by using MEDLINE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and re-view of reference lists of relevant articles and articles sug-gested by experts.Details of the evidence review methods are available in the full AHRQ report (6).This guideline rates the recommendations by using the ACP’s guideline grading system (Table 2)(16).R ISK F ACTORSFORCKDThe major risk factors for CKD include diabetes,hy-pertension,and cardiovascular disease.Other risk factors include older age;obesity;family history;and African American,Native American,or Hispanic ethnicity.Diabe-tes is more prevalent in patients with stage 1to 3CKD (20%)than in patients without CKD (5%)(17).Hyper-tension is also more prevalent in patients with CKD (64%in stage 3and 36%in stage 1)than in patients without CKD (24%)(17).The prevalence of cardiovascular disease increased from 6%in patients without CKD to 36%in those with stage 3CKD (17).S CREENINGFORCKDBenefits of ScreeningDirect EvidenceNo randomized,controlled trials that compared the effect of systematic CKD screening versus no CKD screen-ing on clinical outcomes were identified.Indirect EvidencePrevalence.Among U.S.adults older than 20years,11.1%have stage 1to 3CKD.Approximately 5%of adults younger than 52years and without diabetes,hyper-tension,or obesity have CKD,compared with 68%older than 81years (17).Most patients with stage 1to 3CKD are not clinically recognized to have CKD (18,19).Adverse Health Consequences.Although stage 1to 3CKD is usually asymptomatic,it is associated with mortal-ity (7,8),cardiovascular disease (9),fractures (10),boneCKD Stage Definition1Kidney damage with GFR Ն90mL/min/1.73m 22Kidney damage with GFR of 60–89mL/min/1.73m 23GFR of 30–59mL/min/1.73m 22CKD ϭchronic kidney disease;GFR ϭglomerular filtration rate.*Adapted from reference 3.The Kidney Disease:Improving Global Outcomes Work Group recently updated its definition of CKD progression to include con-sideration of both GFR and albuminuria stages (2).Clinical GuidelineScreening,Monitoring,and Treatment of Stage 1to 3CKD83617December 2013Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 159•Number 12loss(11),infections(12),cognitive impairment(13),and frailty(14).Validity and Reliability of Screening Tests.No popu-lation-based studies have tested the sensitivity or specificity of1-time CKD screening using either estimated GFR or albuminuria or the validity and reliability of repeated screening.Serum creatinine is measured by using a simple blood test.Although no studies have compared GFR esti-mated from serum creatinine values with direct GFR mea-surement,estimation is believed to be reasonably accurate (20).There are many sources of variability when measuring urinary albumin loss(21),and the method of collection and measurement of urinary albumin and creatinine has yet to be standardized.Effect of Treatments on Screen-Detected CKD.There was no randomized trial evidence evaluating the effective-ness of treatment on clinical outcomes of CKD identifiedthrough screening.Harms of ScreeningDirect EvidenceNo randomized,controlled trials have evaluated the harms of systematic CKD screening.Indirect EvidenceExpert opinion suggests that the harms of CKD screening include misclassification of patients owing to false-positive test results,adverse effects of unnecessary test-ing,psychological effects of being labeled with CKD,ad-verse events associated with pharmacologic treatment changes after CKD diagnosis,and possiblefinancial rami-fications of CKD diagnosis.M ONITORING FOR CKDBenefits of MonitoringDirect EvidenceNo randomized,controlled trials have evaluated clini-cal outcomes for patients with stage1to3CKD who were systematically monitored for worsening kidney function versus no CKD monitoring,usual care,or an alternative CKD monitoring regimen.Indirect EvidenceFrequency of Worsening of Kidney Function or Damage in Patients With Stage1to3CKD.The mean annual GFR decline in patients with CKD varies widely,ranging from approximately1to greater than10mL/min/1.73m2(3). Annual rates of conversion from microalbuminuria to macro-albuminuria range from2.8%to9%(22–27).Factors that have been shown to predict faster decline in GFR include diabetes,proteinuria,hypertension,older age,obesity,dys-lipidemia,smoking,male sex,and cause of primary kidney disease.Association of CKD Progression With Adverse Health Consequences.No studies longitudinally assessed the risk for adverse health outcomes in patients with worsening CKD.A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies reported risk for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality for different GFRs and degrees of albuminuria(8).Patients with albu-minuria and GFR greater than60mL/min/1.73m2(CKD stage1or2)had a higher mortality risk if they had mac-roalbuminuria compared with microalbuminuria,although lower GFR within this range was not associated with a higher mortality risk.Mortality risk was increased in pa-tients with a GFR of45to59mL/min/1.73m2,higher in those with GFR30to44mL/min/1.73m2,and even higher in those with GFR less than30mL/min/1.73m2.Validity and Reliability of Tests to Monitor CKD Progression.The same tests are used both to screen for CKD and monitor its progression.No studies assessed the accuracy,precision,specificity,or sensitivity of estimating GFR over time or for detecting a change in CKD stage on the basis of GFR category.The lack of consistent repro-ducibility in albuminuria measurements causes concern about the ability of longitudinal albuminuria measure-ments to accurately represent CKD progression.Effect of Treatments on Clinical Outcomes in Patients Whose CKD Has Progressed.Evidence is lacking on whether treatments reduce the risk for adverse clinical out-comes in patients with worsening CKD.Harms of MonitoringDirect EvidenceNo randomized,controlled trials were identified that compared the adverse effects of systematic monitoring of stage1to3CKD versus no CKD monitoring,usual care, or an alternative CKD monitoring regimen.Indirect EvidenceExpert opinion suggests that the harms of monitoring for CKD progression include incorrect reclassification of patients,adverse effects of unnecessary testing,labeling ef-fects,adverse events associated with changes in pharmaco-logic treatments after testing,and possiblefinancial rami-fications of a more advanced CKD diagnosis.*Adopted from the classification developed by the GRADE(Grading of Recom-mendations,Assessment,Development,and Evaluation)workgroup.Clinical GuidelineScreening,Monitoring,and Treatment of Stage1to3CKD17December2013Annals of Internal Medicine Volume159•Number12837T REATMENT OF CKDTable3summarizes the evidence on treatments for stage1to3CKD.Antihypertensive DrugsMonotherapyPatients receiving-blockers or calcium-channel blockers for CKD treatment may have received other con-comitant antihypertensive agents.Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors Versus Place-bo.Nineteen studies compared treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme(ACE)inhibitors with placebo in patients with stage1to3CKD(23–26,28–42). Moderate-quality evidence showed that treatment with ACE inhibitors reduced the risk for end-stage renal disease (ESRD)(relative risk[RR],0.65[95%CI,0.49to0.88]) compared with placebo in patients with stage1to3CKD (26–28,31,33–35,38).The risk for ESRD was not re-duced in patients with only microalbuminuria or impaired GFR.Moderate-quality evidence showed that treatment with ACE inhibitors did not reduce the risk for all-cause mortality compared with placebo(23–26,28–39,41)(Ta-ble3).Pooled data from10trials(23–26,29–31,35,36, 39)showed that mortality risk was reduced in patients with microalbuminuria(RR,0.79[CI,0.66to0.96]),although most of the data were derived from a large study that showed no difference in mortality between patients with and without microalbuminuria(43).Therapy with ACE inhibitors did not reduce the risk for cardiovascular mor-tality,myocardial infarction(MI),stroke,or other vascular outcomes.ACE Inhibitors Versus-Blockers.Low-quality evi-dence showed no difference in the risk for ESRD or all-cause mortality,cardiovascular mortality,stroke,or heart failure between patients treated with ACE inhibitor mono-therapy compared with-blocker monotherapy(44–46) (Table3).ACE Inhibitors Versus Diuretics.Low-quality evidence showed no difference between ACE inhibitor–treated and diuretic-treated patients in terms of risk for ESRD(47) (Table3).Evidence was insufficient evidence to determine whether the treatments alter the all-cause mortality risk. There was no statistically significant difference between the 2treatments in risk for stroke or multiple composite car-diovascular outcomes.ACE Inhibitors Versus Angiotensin II–Receptor Blockers.End-stage renal disease outcomes were not re-ported in studies comparing ACE inhibitor monotherapy with angiotensin II–receptor blocker(ARB)monotherapy. Low-quality evidence showed that there was no difference between these2monotherapies in risk for all-cause mor-tality(36,48–51)(Table3).There was no statistically significant difference between the2treatments for other reported clinical vascular or renal outcomes.ACE Inhibitors Versus Calcium-Channel Blockers.Low-quality evidence showed that there was no difference in the risk for ESRD(47,52,53)or all-cause mortality(23,52–56)between ACE inhibitor monotherapy and calcium-channel blocker monotherapy(Table3).There was also no difference between the2treatments in terms of risk for cardiovascular mortality,stroke,congestive heart failure (CHF),or any composite vascular end point.ACE Inhibitors Versus Non–ACE Inhibitor Antihyper-tensive Therapy.Low-quality evidence showed that ACE inhibitor monotherapy did not statistically significantly re-duce the risk for ESRD compared with non–ACE inhibi-tor antihypertensive therapy(calcium antagonists,-blockers,or␣-adrenoblockers)(57)(Table3).Evidence was insufficient that ACE inhibitor therapy compared with non–ACE inhibitor antihypertensive therapy is associated with a reduced risk for all-cause mortality.ARB Monotherapy Versus Placebo.High-quality evi-dence showed that treatment with ARBs reduced the risk for ESRD in patients with stage1to3CKD(RR,0.77 [CI,0.66to0.90])compared with placebo(58–60).How-ever,it was not possible to determine whether risk was also reduced in patients with microalbuminuria or impaired GFR who do not have diabetes and hypertension(58–60). High-quality evidence showed that treatment with ARBs did not reduce the risk for all-cause mortality compared with placebo(58–61)(Table3).Treatment with ARBs did not reduce the risk for cardiovascular mortality,MI, CHF complications,or any other clinical vascular outcome compared with placebo;however,ARB treatment did sta-tistically significantly improve renal outcomes.ARBs Versus Calcium-Channel Blockers.Low-quality evidence showed that ARB monotherapy did not reduce the risk for ESRD(59)or all-cause mortality(59,62)com-pared with calcium-channel blocker monotherapy(Table 3).There was also no statistically significant difference be-tween the2treatments in terms of risk for stroke,cardio-vascular mortality,CHF,or composite vascular end points.-Blockers Monotherapy Versus Placebo.End-stage re-nal disease outcomes were not reported in studies compar-ing-blocker monotherapy with placebo.Moderate-quality evidence showed that treatment of CKD with a -blocker reduced the risk for all-cause mortality com-pared with placebo(RR,0.73[CI,0.65to0.82])(63–66).-Blocker treatment also statistically significantly reduced the risk for cardiovascular mortality(64,66),CHF hospi-talization(65,66),and CHF death(65,66).Calcium-Channel Blockers Versus Placebo.Low-quality evidence showed that treatment with calcium-channel blockers in mostly hypertensive patients with albuminuria did not reduce the risk for ESRD(59)or all-cause mortal-ity(23,59)compared with placebo,although this treat-ment did reduce the risk for MI(23,59)(Table3).There was no statistically significant reduction in composite renal outcomes.Calcium-Channel Blockers Versus-Blockers.Low-quality evidence showed that calcium-channel blocker monotherapy did not statistically significantly reduce theClinical Guideline Screening,Monitoring,and Treatment of Stage1to3CKD83817December2013Annals of Internal Medicine Volume159•InterventionOutcomeStrength of Evidence From RCTs (Reference)ResultOther OutcomesAdverse Events*ACE inhibitor vs.placebo MortalityModerate (23–26,28–39,41,42)No reduced risk overall (RR,0.91[95%CI,0.79to 1.05])Reduced risk for composite renal outcomes;mortality risk reduced in patients with microalbuminuria CoughESRDModerate (26–28,31,33–35,38)Reduced risk (RR,0.65[CI,0.49to 0.88])ARB vs.placeboMortality High (58–61)No reduced risk (RR,1.04[CI,0.92to 1.18])Reduced risk for CHF hospitalization (1of 2trials reporting)and composite renaloutcomes (1of 3trials reporting)HyperkalemiaESRDHigh (58–61)Reduced risk (RR,0.77[CI,0.6to 0.90])ACE inhibitor vs.ARB Mortality Low (36,48–51)No reduced risk (RR,1.04[CI,0.37to 2.95])No reduced risk for other outcomes reported NRESRD InsufficientNAACE inhibitor ϩARB vs.ACE inhibitorMortality Moderate (50,71,72)No reduced risk (RR,1.03[CI,0.91to 1.18])Reduced risk for composite vascular outcomesIncreased risk for cough,hyperkalemia,hypotension,and acute kidney failure requiring dialysis ESRDLow (70)No reduced risk (RR,1.00[CI,0.15to 6.79])ACE inhibitor ϩARB vs.ARBMortality Moderate†(60)No reduced risk (RR,1.02[CI,0.93to 1.13])Reduced risk for composite vascular outcomesNRESRDLow†(60)No reduced risk (RR,1.19[CI,0.77to 1.85])-Blocker vs.placebo Mortality Moderate (63–66)Reduced risk (RR,0.73[CI,0.65to 0.82])Reduced risk for CVD mortality,CHFhospitalization,CHF death,and composite vascular outcomes Heart failure,fatigue,bradycardia,dizziness,and hypotensionESRDInsufficientNACalcium-channel blocker vs.placeboMortality Low (23,59)No reduced risk (RR,0.90[CI,0.69to 1.19])Reduced risk for MIHyperkalemiaESRDLow (59)No reduced risk (RR,1.03[CI,0.81to 1.32])Thiazide diuretic vs.placebo Mortality Low (69)No reduced risk (RR,1.17[CI,0.74to 1.85])Reduced risk for stroke NRESRD InsufficientNACalcium-channel blocker vs.-blockerMortality Low (46,67,68)No reduced risk (RR,0.62[CI,0.31to 1.22])No reduced risk for other outcomes reportedNRESRDLow (46,67)No reduced risk (RR,1.00[CI,0.70to 1.44])Calcium-channel blocker vs.diuretic Mortality Insufficient NANo reduced risk for other outcomes reported NRESRD Low (47)No reduced risk (RR,0.90[CI,0.67to 1.21])Strict vs.standard blood pressure controlMortality Low (46,75,76,78)No reduced risk (RR,0.86[CI,0.68to 1.09])No reduced risk for other outcomes reportedNRESRDLow (46,75,78)No reduced risk (RR,1.03[CI,0.77to 1.38])Statin vs.control Mortality High (29,79,81–87)Reduced risk (RR,0.81[CI,0.71to 0.94])Reduced risk for MI,stroke,most composite vascular outcomes reportedNRESRDLow (79,80)No reduced risk (RR,0.98[CI,0.62to 1.56])Low-protein diet ual-protein dietMortality Low (93–96)No reduced risk (RR,0.58[CI,0.29to 1.16])Reduced risk for composite renal outcome (1trial reporting)Weight loss,weight gain,hyperkalemiaESRDLow (92–94)No reduced risk (RR,1.62[CI,0.62to 4.21])Strict ual glycemic Mortality Insufficient NA No reduced risk for other NR ACE ϭangiotensin-converting enzyme;ARB ϭangiotensin II–receptor blocker;CHF ϭcongestive heart failure;CKD ϭchronic kidney disease;CVD ϭcardiovascular disease;ESRD ϭend-stage renal disease;MI ϭmyocardial infarction;NA ϭnot applicable;NR ϭnot reported;RCT ϭrandomized,controlled trial;RR ϭrelative risk.*Adverse events were sparsely reported in the trials included in this study and often similar in control and treatment groups.†Data derived from a study comparing ACE inhibitor plus ARB combination therapy with either ARB or ACE inhibitor monotherapy.Clinical GuidelineScreening,Monitoring,and Treatment of Stage 1to 3CKD 17December 2013Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 159•Number 12839risk for ESRD(46,67)or all-cause mortality(46,67,68) compared with-blocker monotherapy(Table3).No sta-tistically significant difference in renal outcomes was reported.Calcium-Channel Blockers Versus Diuretics.Low-quality evidence showed that calcium-channel blocker monotherapy did not statistically significantly reduce the risk for ESRD compared with diuretic monotherapy(47) (Table3).Mortality data were not reported.There were no statistically significant differences in renal or vascular outcomes reported.Thiazide Diuretics Versus Placebo.No renal outcomes were reported for the comparison of thiazide diuretic monotherapy with placebo.Low-quality evidence showed no difference between the2groups in risk for all-cause mortality(69)(Table3).Diuretic monotherapy statisti-cally significantly reduced the risk for stroke and1com-posite vascular outcome.Combination Therapy Versus MonotherapyACE Inhibitors Plus ARBs Versus ACE Inhibitors Alone.Low-quality evidence showed no statistically sig-nificant difference in risk for ESRD between treatment with ACE inhibitors plus ARBs compared with ACE in-hibitors alone(70)(Table3).Moderate-quality evidence also showed no statistically significant difference in the risk for all-cause mortality in the combined treatment group compared with monotherapy(50,71,72)(Table3).ACE Inhibitors Plus ARBs Versus ARBs Alone.There was no evidence directly comparing the risk for ESRD or mortality with ACE inhibitors plus ARBs compared with ARB monotherapy.However,1trial(60)compared ACE inhibitor plus ARB combination therapy with either ARB or ACE inhibitor monotherapy(results for monotherapy reported together);moderate-quality evidence showed no reduced risk for ESRD,and low-quality evidence showed no reduced risk for all-cause mortality in the combined treatment group(Table3).Other Comparisons.Evidence was insufficient to de-termine the effect of the following comparisons on ESRD or mortality:ACE inhibitors plus calcium-channel blockers versus ACE inhibitor monotherapy or calcium-channel blocker monotherapy;ACE inhibitors plus diuretics versus ACE inhibitor monotherapy;and ACE inhibitors plus di-uretics versus placebo.Combination Therapy Versus Combination TherapyEvidence was insufficient to determine the effect of the following comparisons on ESRD or mortality:ACE inhib-itor plus ARB versus ACE inhibitor plus aldosterone an-tagonist;ACE inhibitor plus diuretic versus ACE inhibitor plus calcium-channel blocker;ACE inhibitor plus aldoste-rone antagonist versus ACE inhibitor plus placebo;and ACE inhibitor and ARB plus aldosterone antagonist versus ACE inhibitor and ARB plus placebo.Strict Versus Standard Blood Pressure ControlSeven studies(46,73–78)randomly assigned patients with stage1to3CKD(mostly with hypertension)to strict versus standard blood pressure targets,and medications varied among studies.The mean achieved blood pressure ranged from128to133mm Hg systolic and75to81mm Hg diastolic in the strict-control group versus134to141 mm Hg systolic and81to87mm Hg diastolic in the standard-control group.Low-quality evidence showed no difference in risk for ESRD(46,75,78)or all-cause mor-tality(46,75,77,78).between strict and standard blood pressure control(Table3).There was no statistically sig-nificant difference between other reported vascular or renal outcomes.Non–Blood Pressure Control InterventionsStatins Versus ControlLow-quality evidence showed that treatment with statins(3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors)did not reduce the risk for ESRD in patients with dyslipidemia and stage1to3CKD(79,80)(Table 3).Moderate-quality evidence(subgroup analyses)showed that statins reduced the risk for all-cause mortality in pa-tients with dyslipidemia as well as stage1to3CKD(RR, 0.81[CI,0.71to0.94])(29,79,81–87).Statins were found to statistically significantly reduce the risk for MI, stroke,and most composite vascular outcomes reported.Low-quality evidence from1trial(88)that reported on mortality in patients with CKD and dyslipidemia treated with high-dose atorvastatin(80mg/d)versus low-dose atorvastatin(10mg/d)found no difference in the risk for all-cause mortality(7.0%vs.7.5%,respectively;RR 0.93[CI,0.72to1.20]);however,the high-dose atorvasta-tin group had a decreased risk for CHF hospitalization and composite vascular outcomes.Another study(89)reported no differences between high-and low-dose statin treatment in terms of composite vascular outcomes.No results were reported for ESRD or any renal outcomes.Gemfibrozil Versus Placebo or ControlLow-quality evidence from a single trial(90)supports no difference in all-cause mortality reduction for treatment with the triglyceride-lowering medication gemfibrozil com-pared with placebo(RR,0.91[CI,0.52to1.62]).No individuals in the study experienced ESRD.Gemfibrozil was found to statistically significantly reduce the risk for the composite outcome of fatal coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI,or stroke compared with placebo.Evidence was insufficient to determine whether treatment with gem-fibrozil reduced the risk for ESRD or all-cause mortality compared with a triglyceride-lowering diet(91).Low-Protein Diet Versus Usual-Protein DietLow-quality evidence from3trials comparing a low-protein diet with usual diet in patients with stage1to3 CKD(92–94)showed no statistically significant differenceClinical Guideline Screening,Monitoring,and Treatment of Stage1to3CKD84017December2013Annals of Internal Medicine Volume159•。