伍德里奇计量经济学第六版答案Chapter 2

- 格式:docx

- 大小:301.14 KB

- 文档页数:13

第1章计量经济学的性质与经济数据1.1复习笔记考点一:计量经济学★1计量经济学的含义计量经济学,又称经济计量学,是由经济理论、统计学和数学结合而成的一门经济学的分支学科,其研究内容是分析经济现象中客观存在的数量关系。

2计量经济学模型(1)模型分类模型是对现实生活现象的描述和模拟。

根据描述和模拟办法的不同,对模型进行分类,如表1-1所示。

(2)数理经济模型和计量经济学模型的区别①研究内容不同数理经济模型的研究内容是经济现象各因素之间的理论关系,计量经济学模型的研究内容是经济现象各因素之间的定量关系。

②描述和模拟办法不同数理经济模型的描述和模拟办法主要是确定性的数学形式,计量经济学模型的描述和模拟办法主要是随机性的数学形式。

③位置和作用不同数理经济模型可用于对研究对象的初步研究,计量经济学模型可用于对研究对象的深入研究。

考点二:经济数据★★★1经济数据的结构(见表1-3)2面板数据与混合横截面数据的比较(见表1-4)考点三:因果关系和其他条件不变★★1因果关系因果关系是指一个变量的变动将引起另一个变量的变动,这是经济分析中的重要目标之计量分析虽然能发现变量之间的相关关系,但是如果想要解释因果关系,还要排除模型本身存在因果互逆的可能,否则很难让人信服。

2其他条件不变其他条件不变是指在经济分析中,保持所有的其他变量不变。

“其他条件不变”这一假设在因果分析中具有重要作用。

1.2课后习题详解一、习题1.假设让你指挥一项研究,以确定较小的班级规模是否会提高四年级学生的成绩。

(i)如果你能指挥你想做的任何实验,你想做些什么?请具体说明。

(ii)更现实地,假设你能搜集到某个州几千名四年级学生的观测数据。

你能得到它们四年级班级规模和四年级末的标准化考试分数。

你为什么预计班级规模与考试成绩成负相关关系?(iii)负相关关系一定意味着较小的班级规模会导致更好的成绩吗?请解释。

答:(i)假定能够随机的分配学生们去不同规模的班级,也就是说,在不考虑学生诸如能力和家庭背景等特征的前提下,每个学生被随机的分配到不同的班级。

271APPENDIX ESOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMSE.1 This follows directly from partitioned matrix multiplication in Appendix D. WriteX = 12n ⎛⎫ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪⎝⎭x x x , X ' = (1'x 2'x n 'x ), and y = 12n ⎛⎫ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪⎝⎭y y yTherefore, X 'X = 1nt t t ='∑x x and X 'y = 1nt t t ='∑x y . An equivalent expression for ˆβ isˆβ = 111nt t t n --=⎛⎫' ⎪⎝⎭∑x x 11n t t t n y -=⎛⎫' ⎪⎝⎭∑x which, when we plug in y t = x t β + u t for each t and do some algebra, can be written asˆβ= β + 111n t t t n --=⎛⎫' ⎪⎝⎭∑x x 11nt t t n u -=⎛⎫' ⎪⎝⎭∑x . As shown in Section E.4, this expression is the basis for the asymptotic analysis of OLS using matrices.E.2 (i) Following the hint, we have SSR(b ) = (y – Xb )'(y – Xb ) = [ˆu+ X (ˆβ – b )]'[ ˆu + X (ˆβ – b )] = ˆu'ˆu + ˆu 'X (ˆβ – b ) + (ˆβ – b )'X 'ˆu + (ˆβ – b )'X 'X (ˆβ – b ). But by the first order conditions for OLS, X 'ˆu= 0, and so (X 'ˆu )' = ˆu 'X = 0. But then SSR(b ) = ˆu 'ˆu + (ˆβ – b )'X 'X (ˆβ – b ), which is what we wanted to show.(ii) If X has a rank k then X 'X is positive definite, which implies that (ˆβ– b ) 'X 'X (ˆβ – b ) > 0 for all b ≠ ˆβ. The term ˆu 'ˆu does not depend on b , and so SSR(b ) – SSR(ˆβ) = (ˆβ– b ) 'X 'X (ˆβ– b ) > 0 for b ≠ˆβ.E.3 (i) We use the placeholder feature of the OLS formulas. By definition, β = (Z 'Z )-1Z 'y =[(XA )' (XA )]-1(XA )'y = [A '(X 'X )A ]-1A 'X 'y = A -1(X 'X )-1(A ')-1A 'X 'y = A -1(X 'X )-1X 'y = A -1ˆβ.(ii) By definition of the fitted values, ˆt y = ˆt x β and t y = tz β. Plugging z t and β into the second equation gives ty = (x t A )(A -1ˆβ) = ˆt x β = ˆty .(iii) The estimated variance matrix from the regression of y and Z is 2σ(Z 'Z )-1 where 2σ is the error variance estimate from this regression. From part (ii), the fitted values from the two272regressions are the same, which means the residuals must be the same for all t . (The dependentvariable is the same in both regressions.) Therefore, 2σ = 2ˆσ. Further, as we showed in part (i), (Z 'Z )-1 = A -1(X 'X )-1(A ')-1, and so 2σ(Z 'Z )-1 = 2ˆσA -1(X 'X )-1(A -1)', which is what we wanted to show.(iv) The j β are obtained from a regression of y on XA , where A is the k ⨯ k diagonal matrixwith 1, a 2, , a k down the diagonal. From part (i), β = A -1ˆβ. But A -1 is easily seen to be the k ⨯ k diagonal matrix with 1, 12a -, , 1k a - down its diagonal. Straightforward multiplicationshows that the first element of A -1ˆβis 1ˆβ and the j th element is ˆjβ/a j , j = 2, , k .(v) From part (iii), the estimated variance matrix of β is 2ˆσA -1(X 'X )-1(A -1)'. But A -1 is a symmetric, diagonal matrix, as described above. The estimated variance of j β is the j thdiagonal element of 2ˆσA -1(X 'X )-1A -1, which is easily seen to be = 2ˆσc jj /2ja -, where c jj is the j th diagonal element of (X 'X )-1. The square root of this, a j |, is se(j β), which is simply se(j β)/|a j |.(vi) The t statistic for j β is, as usual,j β/se(j β) = (ˆj β/a j )/[se(ˆjβ)/|a j |],and so the absolute value is (|ˆj β|/|a j |)/[se(ˆj β)/|a j |] = |ˆj β|/se(ˆjβ), which is just the absolute value of the t statistic for ˆjβ. If a j > 0, the t statistics themselves are identical; if a j < 0, the t statistics are simply opposite in sign.E.4 (i) 垐?E(|)E(|)E(|).====δX GβX G βX Gβδ(ii) 2121垐?Var(|)Var(|)[Var(|)][()][()].σσ--'''''====δX GβX G βX G G X X G G X X G(iii) The vector of regression coefficients from the regression y on XG -1 is111111111111[()]()[()]() ()[()]()ˆ ()()().------------''''''='''''=''''''''===XG XG XG y G X XG G X y G X X G G X yG X X G G X y G X X X y δFurther, as shown in Problem E.3, the residuals are the same as from the regression y on X , andso the error variance estimate, 2ˆ,σis the same. Therefore, the estimated variance matrix is。

伍德⾥奇---计量经济学第2章部分计算机习题详解(MATLAB)班级:⾦融学×××班姓名:××学号:×××××××C2.1 401K.RAW prate=β0+β1mrate解:(ⅰ)求出计划的样本中平均参与率和平均匹配率.所以,平均参与率为87.36,平均匹配率为0.73.(ⅱ)报告结果以及样本容量和R2.β1=mrate i?mrate(prate i?prate)ni=1mrate i?mrate2ni=1=cov(x,y)var(x)β0=prate?β1mrate=A?β1B R2=SSESST所以β1= 5.8611;所以β0= 83.07.= 0.0747, n=1534.且R2=SSESST(ⅲ)解释⽅程中的截距和mrate的系数.⽅程中的截距β0意味着,当mrate= 0时,预测的参与率是83.07%。

⽽系数mrate意味着员⼯每投⼊⼀美元,prate的预期变化为5.86个百分点。

(ⅳ)当mrate=3.5时,求出prate的预测值。

只是⼀个合理的预测吗?解释这⾥出现的情况.由(ⅱ)可得prate=83.07+5.86mrate,所以当mrate=3.5时,prate= 83.07 + 5.86 * 3.5 = 103.58,即prate的预测值是103.85.这不是⼀个合理的预测,因为最多只可能有100%的参与率,不可能超过100% 。

(ⅴ)prate的变异中,有多少是由mrate解释的?这是⼀个⾜够⼤的量吗?在prate的变异中,有7.47% 是由mrate解释的,这不是⼀个⾜够⼤的量,意味着还有许多其他因素影响计划的参与率。

C2.2 CEOSAL2.RAW lo g salary=β0+β1ceoten+u解:(ⅰ)求出样本中的平均年薪和平均任期.所以,平均年薪为865.86,平均任期为7.95.(ⅱ)有多少位CEO尚处于担任CEO的第⼀年(即ceoten=0)?最长的CEO任期是多少?所以,有5位CEO尚处于担任CEO的第⼀年;所以,最长的CEO任期是37年。

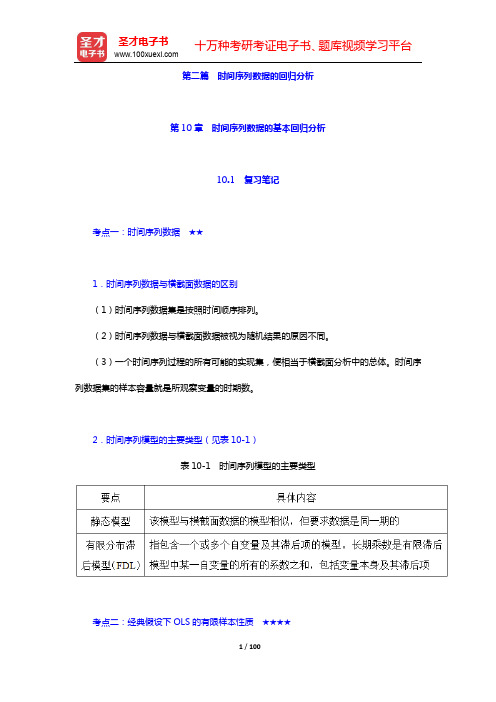

第二篇时间序列数据的回归分析第10章时间序列数据的基本回归分析10.1 复习笔记考点一:时间序列数据★★1.时间序列数据与横截面数据的区别(1)时间序列数据集是按照时间顺序排列。

(2)时间序列数据与横截面数据被视为随机结果的原因不同。

(3)一个时间序列过程的所有可能的实现集,便相当于横截面分析中的总体。

时间序列数据集的样本容量就是所观察变量的时期数。

2.时间序列模型的主要类型(见表10-1)表10-1 时间序列模型的主要类型考点二:经典假设下OLS的有限样本性质★★★★1.高斯-马尔可夫定理假设(见表10-2)表10-2 高斯-马尔可夫定理假设2.OLS估计量的性质与高斯-马尔可夫定理(见表10-3)表10-3 OLS估计量的性质与高斯-马尔可夫定理3.经典线性模型假定下的推断(1)假定TS.6(正态性)假定误差u t独立于X,且具有独立同分布Normal(0,σ2)。

该假定蕴涵了假定TS.3、TS.4和TS.5,但它更强,因为它还假定了独立性和正态性。

(2)定理10.5(正态抽样分布)在时间序列的CLM假定TS.1~TS.6下,以X为条件,OLS估计量遵循正态分布。

而且,在虚拟假设下,每个t统计量服从t分布,F统计量服从F分布,通常构造的置信区间也是确当的。

定理10.5意味着,当假定TS.1~TS.6成立时,横截面回归估计与推断的全部结论都可以直接应用到时间序列回归中。

这样t统计量可以用来检验个别解释变量的统计显著性,F统计量可以用来检验联合显著性。

考点三:时间序列的应用★★★★★1.函数形式、虚拟变量除了常见的线性函数形式,其他函数形式也可以应用于时间序列中。

最重要的是自然对数,在应用研究中经常出现具有恒定百分比效应的时间序列回归。

虚拟变量也可以应用在时间序列的回归中,如某一期的数据出现系统差别时,可以采用虚拟变量的形式。

2.趋势和季节性(1)描述有趋势的时间序列的方法(见表10-4)表10-4 描述有趋势的时间序列的方法(2)回归中的趋势变量由于某些无法观测的趋势因素可能同时影响被解释变量与解释变量,被解释变量与解释变量均随时间变化而变化,容易得到被解释变量与解释变量之间趋势变量的关系,而非真正的相关关系,导致了伪回归。

伍德⾥奇《计量经济学导论》(第6版)复习笔记和课后习题详解-多元回归分析:推断【圣才出品】第4章多元回归分析:推断4.1复习笔记考点⼀:OLS估计量的抽样分布★★★1.假定MLR.6(正态性)假定总体误差项u独⽴于所有解释变量,且服从均值为零和⽅差为σ2的正态分布,即:u~Normal(0,σ2)。

对于横截⾯回归中的应⽤来说,假定MLR.1~MLR.6被称为经典线性模型假定。

假定下对应的模型称为经典线性模型(CLM)。

2.⽤中⼼极限定理(CLT)在样本量较⼤时,u近似服从于正态分布。

正态分布的近似效果取决于u中包含多少因素以及因素分布的差异。

但是CLT的前提假定是所有不可观测的因素都以独⽴可加的⽅式影响Y。

当u是关于不可观测因素的⼀个复杂函数时,CLT论证可能并不适⽤。

3.OLS估计量的正态抽样分布定理4.1(正态抽样分布):在CLM假定MLR.1~MLR.6下,以⾃变量的样本值为条件,有:∧βj~Normal(βj,Var(∧βj))。

将正态分布函数标准化可得:(∧βj-βj)/sd(∧βj)~Normal(0,1)。

注:∧β1,∧β2,…,∧βk的任何线性组合也都符合正态分布,且∧βj的任何⼀个⼦集也都具有⼀个联合正态分布。

考点⼆:单个总体参数检验:t检验★★★★1.总体回归函数总体模型的形式为:y=β0+β1x1+…+βk x k+u。

假定该模型满⾜CLM假定,βj的OLS 量是⽆偏的。

2.定理4.2:标准化估计量的t分布在CLM假定MLR.1~MLR.6下,(∧βj-βj)/se(∧βj)~t n-k-1,其中,k+1是总体模型中未知参数的个数(即k个斜率参数和截距β0)。

t统计量服从t分布⽽不是标准正态分布的原因是se(∧βj)中的常数σ已经被随机变量∧σ所取代。

t统计量的计算公式可写成标准正态随机变量(∧βj-βj)/sd(∧βj)与∧σ2/σ2的平⽅根之⽐,可以证明⼆者是独⽴的;⽽且(n-k-1)∧σ2/σ2~χ2n-k-1。

计量经济学第六版第二章计算机课后答案1.计量经济学是一门什么样的学科?答:计量经济学的英文单词是Econometrics,本意是“经济计量”,研究经济问题的计量方法,因此有时也译为“经济计量学”。

将Econometrics译为“计量经济学”是为了强调它是现代经济学的一门分支学科,不仅要研究经济问题的计量方法,还要研究经济问题发展变化的数量规律。

可以认为,计量经济学是以经济理论为指导,以经济数据为依据,以数学、统计方法为手段,通过建立、估计、检验经济模型,揭示客观经济活动中存在的随机因果关系的一门应用经济学的分支学科。

2.计量经济学与经济理论、数学、统计学的联系和区别是什么?答:计量经济学是经济理论、数学、统计学的结合,是经济学、数学、统计学的交叉学科(或边缘学科)。

计量经济学与经济学、数学、统计学的联系主要是计量经济学对这些学科的应用。

计量经济学对经济学的应用主要体现在以下几个方面:第一,计量经济学模型的选择和确定,包括对变量和经济模型的选择,需要经济学理论提供依据和思路;第二,计量经济分析中对经济模型的修改和调整,如改变函数形式、增减变量等,需要有经济理论的指导和把握;第三,计量经济分析结果的解读和应用也需要经济理论提供基础、背景和思路。

计量经济学对统计学的应用,至少有两个重要方面:一是计量经济分析所采用的数据的收集与处理、参数的估计等,需要使用统计学的方法和技术来完成;一是参数估计值、模型的预测结果的可靠性,需要使用统计方法加以分析、判断。

计量经济学对数学的应用也是多方面的,首先,对非线性函数进行线性转化的方法和技巧,是数学在计量经济学中的应用;其次,任何的参数估计归根结底都是数学运算,较复杂的参数估计方法,或者较复杂的模型的参数估计,更需要相当的数学知识和数学运算能力,另外,在计量经济理论和方法的研究方面,需要用到许多的数学知识和原理。

计量经济学与经济学、数学、统计学的区别也很明显,经济学、数学、统计学中的任何一门学科,都不能替代计量经济学,这三门学科简单地合起来,也不能替代计量经济学。

第9章模型设定和数据问题的深入探讨9.1复习笔记考点一:函数形式设误检验(见表9-1)★★★★表9-1函数形式设误检验考点二:对无法观测解释变量使用代理变量★★★1.代理变量代理变量就是某种与分析中试图控制而又无法观测的变量相关的变量。

(1)遗漏变量问题的植入解假设在有3个自变量的模型中,其中有两个自变量是可以观测的,解释变量x3*观测不到:y=β0+β1x1+β2x2+β3x3*+u。

但有x3*的一个代理变量,即x3,有x3*=δ0+δ3x3+v3。

其中,x3*和x3正相关,所以δ3>0;截距δ0容许x3*和x3以不同的尺度来度量。

假设x3就是x3*,做y对x1,x2,x3的回归,从而利用x3得到β1和β2的无偏(或至少是一致)估计量。

在做OLS之前,只是用x3取代了x3*,所以称之为遗漏变量问题的植入解。

代理变量也可以以二值信息的形式出现。

(2)植入解能得到一致估计量所需的假定(见表9-2)表9-2植入解能得到一致估计量所需的假定2.用滞后因变量作为代理变量对于想要控制无法观测的因素,可以选择滞后因变量作为代理变量,这种方法适用于政策分析。

但是现期的差异很难用其他方法解释。

使用滞后被解释变量不是控制遗漏变量的唯一方法,但是这种方法适用于估计政策变量。

考点三:随机斜率模型★★★1.随机斜率模型的定义如果一个变量的偏效应取决于那些随着总体单位的不同而不同的无法观测因素,且只有一个解释变量x,就可以把这个一般模型写成:y i=a i+b i x i。

上式中的模型有时被称为随机系数模型或随机斜率模型。

对于上式模型,记a i=a+c i和b i=β+d i,则有E(c i)=0和E(d i)=0,代入模型得y i=a+βx i+u i,其中,u i=c i+d i x i。

2.保证OLS无偏(一致性)的条件(1)简单回归当u i=c i+d i x i时,无偏的充分条件就是E(c i|x i)=E(c i)=0和E(d i|x i)=E(d i)=0。

第14章高级面板数据方法14.1复习笔记考点一:固定效应估计法★★★★★1.固定效应变换固定效应变换又称组内变换,考虑仅有一个解释变量的模型:对每个i,有y it =β1x it +a i +u it ,t=1,2,…,T对每个i 求方程在时间上的平均,便得到_y i =β1_x i +a i +_u i 其中,11T it t y T y-==∑(关于时间的均值)。

因为a i 在不同时间固定不变,故它会在原模型和均值模型中都出现,如果对于每个t,两式相减,便得到y it -_y i =β1(x it -_x i )+u it -_u i ,t=1,2,…,T或1 12it it it y x u ,t ,,,T=+=&&&&&&L β其中,it it i y y y =-&&是y 的除时间均值数据;对it x &&和it u &&的解释也类似。

方程的要点在于,非观测效应a i 已随之消失,从而可以使用混合OLS 去估计式1 12it it it y x u ,t ,,,T =+=&&&&&&L β。

上式的混合OLS 估计量被称为固定效应估计量或组内估计量。

组间估计量可以从横截面方程_y i =β1_x i +a i +_u i 的OLS 估计量而得到,即同时使用y 和x的时间平均值做一个横截面回归。

如果a i与_x i相关,估计量是有偏误的。

而如果认为a i 与x it无关,则使用随机效应估计量要更好。

组间估计量忽视了变量如何随着时间而变化。

在方程中添加更多解释变量不会引起什么变化。

2.固定效应模型(1)无偏性原始的非固定效应模型,只要让每一个变量都减去时间均值数据,即可得到固定效应模型。

固定效应模型的无偏性是建立在严格外生性的假定下的,所以FE模型需要假定特异误差u it应与所有时期的每个解释变量都无关。

265APPENDIX CSOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMSC.1 (i) This is just a special case of what we covered in the text, with n = 4: E(Y ) = µ and Var(Y ) = σ2/4.(ii) E(W ) = E(Y 1)/8 + E(Y 2)/8 + E(Y 3)/4 + E(Y 4)/2 = µ[(1/8) + (1/8) + (1/4) + (1/2)] = µ(1 + 1 + 2 + 4)/8 = µ, which shows that W is unbiased. Because the Y i are independent, Var(W ) = Var(Y 1)/64 + Var(Y 2)/64 + Var(Y 3)/16 + Var(Y 4)/4 = σ2[(1/64) + (1/64) + (4/64) + (16/64)] = σ2(22/64) = σ2(11/32).(iii) Because 11/32 > 8/32 = 1/4, Var(W ) > Var(Y ) for any σ2 > 0, so Y is preferred to W because each is unbiased.C.2 (i) E(W a ) = a 1E(Y 1) + a 2E(Y 2) + + a n E(Y n ) = (a 1 + a 2 + + a n )µ. Therefore, we must have a 1 + a 2 + + a n = 1 for unbiasedness.(ii) Var(W a ) = 21a Var(Y 1) + 22a Var(Y 2) + + 2n a Var(Y n ) = (21a + 22a+ + 2n a )σ2.(iii) From the hint, when a 1 + a 2 + + a n = 1 – the condition needed for unbiasedness of W a– we have 1/n ≤ 21a + 22a + + 2n a . But then Var(Y ) = σ2/n ≤ σ2(21a+ 22a + + 2n a ) =Var(W a ).C.3 (i) E(W 1) = [(n – 1)/n ]E(Y ) = [(n – 1)/n ]µ, and so Bias(W 1) = [(n – 1)/n ]µ – µ = –µ/n . Similarly, E(W 2) = E(Y )/2 = µ/2, and so Bias(W 2) = µ/2 – µ = –µ/2. The bias in W 1 tends to zero as n → ∞, while the bias in W 2 is –µ/2 for all n . This is an important difference.(ii) plim(W 1) = plim[(n – 1)/n ]⋅plim(Y ) = 1⋅µ = µ. plim(W 2) = plim(Y )/2 = µ/2. Because plim(W 1) = µ and plim(W 2) = µ/2, W 1 is consistent whereas W 2 is inconsistent.(iii) Var(W 1) = [(n – 1)/n ]2Var(Y ) = [(n – 1)2/n 3]σ2 and Var(W 2) = Var(Y )/4 = σ2/(4n ).(iv) Because Y is unbiased, its mean squared error is simply its variance. On the other hand, MSE(W 1) = Var(W 1) + [Bias(W 1)]2 = [(n – 1)2/n 3]σ2 + µ2/n 2. When µ = 0, MSE(W 1) = Var(W 1) = [(n – 1)2/n 3]σ2 < σ2/n = Var(Y ) because (n – 1)/n < 1. Therefore, MSE(W 1) is smaller than Var(Y ) for µ close to zero. For large n , the difference between the two estimators is trivial.C.4 (i) Using the hint, E(Z |X ) = E(Y /X |X ) = E(Y |X )/X = θX /X = θ. It follows by Property CE.4, the law of iterated expectations, that E(Z ) = E(θ) = θ.266(ii) This follows from part (i) and the fact that the sample average is unbiased for the population average: write11111(/),n niiii i W nY X n Z --====∑∑where Z i = Y i /X i . From part (i), E(Z i ) = θ for all i .(iii) In general, the average of the ratios, Y i /X i , is not the ratio of averages, 2/.W Y X = (This non-equivalence is discussed a bit on page 676.) Nevertheless, W 2 is also unbiased, as a simple application of the law of iterated expectations shows. First, E(Y i |X 1,…,X n ) = E(Y i |X i ) under random sampling because the observations are independent. Therefore, E(Y i |X 1,…,X n ) = i X θ and so11111111E(|,...,)E(|,...,).nnn inii i ni i Y X X nY X XnXn X X θθθ--==-=====∑∑∑Therefore, 211E(|,...,)E(/|,...,)/,n n W X X Y X X X X X θθ===which means that W 2 is actually unbiased conditional on 1(,...,)n X X , and therefore also unconditionally unbiased.(iv) For the n = 17 observations given in the table – which are, incidentally, the first 17observations in the file CORN.RAW – the point estimates are w 1 = .418 and w 2 = 120.43/297.41 = .405. These are pretty similar estimates. If we use w 1, we estimate E(Y |X = x ) for any x > 0 asE(|)Y X x = = .418 x . For example, if x = 300 then the predicted yield is .418(300) = 125.4.C.5 (i) While the expected value of the numerator of G is E(Y ) = θ, and the expected value of the denominator is E(1 – Y ) = 1 – θ, the expected value of the ratio is not the ratio of the expected value.(ii) By Property PLIM.2(iii), the plim of the ratio is the ratio of the plims (provided the plim of the denominator is not zero): plim(G ) = plim[Y /(1 – Y )] = plim(Y )/[1 – plim(Y )] = θ/(1 – θ) = γ.C.6 (i) H 0: µ = 0.(ii) H 1: µ < 0.(iii) The standard error of yis s ≈ 15.55. Therefore, the t statistic for testing H 0: µ = 0 is t = y /se(y ) = –32.8/15.55 ≈ –2.11. We obtain the p -value as P(Z ≤ –2.11), where Z ~ Normal(0,1). These probabilities are in Table G.1: p -value = .0174. Because the p -。

CHAPTER 2TEACHING NOTESThis is the chapter where I expect students to follow most, if not all, of the algebraic derivations. In class I like to derive at least the unbiasedness of the OLS slope coefficient, and usually I derive the variance. At a minimum, I talk about the factors affecting the variance. To simplify the notation, after I emphasize the assumptions in the population model, and assume random sampling, I just condition on the values of the explanatory variables in the sample. Technically, this is justified by random sampling because, for example, E(u i|x1,x2,…,x n) = E(u i|x i) by independent sampling. I find that students are able to focus on the key assumption SLR.4 and subsequently take my word about how conditioning on the independent variables in the sample is harmless. (If you prefer, the appendix to Chapter 3 does the conditioning argument carefully.) Because statistical inference is no more difficult in multiple regression than in simple regression, I postpone inference until Chapter 4. (This reduces redundancy and allows you to focus on the interpretive differences between simple and multiple regression.)You might notice how, compared with most other texts, I use relatively few assumptions to derive the unbiasedness of the OLS slope estimator, followed by the formula for its variance. This is because I do not introduce redundant or unnecessary assumptions. For example, once SLR.4 is assumed, nothing further about the relationship between u and x is needed to obtain the unbiasedness of OLS under random sampling.Incidentally, one of the uncomfortable facts about finite-sample analysis is that there is a difference between an estimator that is unbiased conditional on the outcome of the covariates and one that is unconditionally unbiased. If the distribution of the x i is such that they can all equal the same value with positive probability – as is the case with discreteness in the distribution –then the unconditional expectation does not really exist. Or, if it is made to exist then the estimator is not unbiased. I do not try to explain these subtleties in an introductory course, but I have had instructors ask me about the difference.SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS2.1 (i) Income, age, and family background (such as number of siblings) are just a fewpossibilities. It seems that each of these could be correlated with years of education. (Income and education are probably positively correlated; age and education may be negatively correlated because women in more recent cohorts have, on average, more education; and number of siblings and education are probably negatively correlated.)(ii) Not if the factors we listed in part (i) are correlated with educ . Because we would like to hold these factors fixed, they are part of the error term. But if u is correlated with educ then E(u|educ ) ≠ 0, and so SLR.4 fails.2.2 In the equation y = β0 + β1x + u , add and subtract α0 from the right hand side to get y = (α0 + β0) + β1x + (u - α0). Call the new error e = u - α0, so that E(e ) = 0. The new intercept is α0 + β0, but the slope is still β1.2.3 (i) Let y i = GPA i , x i = ACT i , and n = 8. Then x = 25.875, y =3.2125, 1ni =∑(x i – x )(y i – y ) =5.8125, and 1ni =∑(x i – x )2 = 56.875. From equation (2.9), we obtain the slope as 1ˆβ= 5.8125/56.875 ≈ .1022, rounded to four places after the decimal. From (2.17), 0ˆβ = y – 1ˆβx ≈ 3.2125 – (.1022)25.875 ≈ .5681. So we can writeGPA = .5681 + .1022 ACTn = 8.The intercept does not have a useful interpretation because ACT is not close to zero for the population of interest. If ACT is 5 points higher, GPA increases by .1022(5) = .511.(ii) The fitted values and residuals — rounded to four decimal places — are given along with the observation number i and GPA in the following table:You can verify that the residuals, as reported in the table, sum to -.0002, which is pretty close to zero given the inherent rounding error.(iii) When ACT = 20, GPA = .5681 + .1022(20) ≈ 2.61.(iv) The sum of squared residuals,21ˆni i u=∑, is about .4347 (rounded to four decimal places), and the total sum of squares,1ni =∑(y i – y )2, is about 1.0288. So the R -squared from the regressionisR 2 = 1 – SSR/SST ≈ 1 – (.4347/1.0288) ≈ .577.Therefore, about 57.7% of the variation in GPA is explained by ACT in this small sample of students.2.4 (i) When cigs = 0, predicted birth weight is 119.77 ounces. When cigs = 20, bwght = 109.49. This is about an 8.6% drop.(ii) Not necessarily. There are many other factors that can affect birth weight, particularly overall health of the mother and quality of prenatal care. These could be correlated withcigarette smoking during birth. Also, something such as caffeine consumption can affect birth weight, and might also be correlated with cigarette smoking.(iii) If we want a predicted bwght of 125, then cigs = (125 – 119.77)/( –.524) ≈–10.18, or about –10 cigarettes! This is nonsense, of course, and it shows what happens when we are trying to predict something as complicated as birth weight with only a single explanatory variable. The largest predicted birth weight is necessarily 119.77. Yet almost 700 of the births in the sample had a birth weight higher than 119.77.(iv) 1,176 out of 1,388 women did not smoke while pregnant, or about 84.7%. Because we are using only cigs to explain birth weight, we have only one predicted birth weight at cigs = 0. The predicted birth weight is necessarily roughly in the middle of the observed birth weights at cigs = 0, and so we will under predict high birth rates.2.5 (i) The intercept implies that when inc = 0, cons is predicted to be negative $124.84. This, of course, cannot be true, and reflects that fact that this consumption function might be a poor predictor of consumption at very low-income levels. On the other hand, on an annual basis, $124.84 is not so far from zero.(ii) Just plug 30,000 into the equation: cons = –124.84 + .853(30,000) = 25,465.16 dollars.(iii) The MPC and the APC are shown in the following graph. Even though the intercept is negative, the smallest APC in the sample is positive. The graph starts at an annual income level of $1,000 (in 1970 dollars).increases housing prices.(ii) If the city chose to locate the incinerator in an area away from more expensive neighborhoods, then log(dist) is positively correlated with housing quality. This would violate SLR.4, and OLS estimation is biased.(iii) Size of the house, number of bathrooms, size of the lot, age of the home, and quality of the neighborhood (including school quality), are just a handful of factors. As mentioned in part (ii), these could certainly be correlated with dist [and log(dist )].2.7 (i) When we condition on incbecomes a constant. So E(u |inc⋅e |inc) = ⋅E(e |inc⋅0 because E(e |inc ) = E(e ) = 0.(ii) Again, when we condition on incbecomes a constant. So Var(u |inc⋅e |inc2Var(e |inc ) = 2e σinc because Var(e |inc ) = 2e σ.(iii) Families with low incomes do not have much discretion about spending; typically, a low-income family must spend on food, clothing, housing, and other necessities. Higher income people have more discretion, and some might choose more consumption while others more saving. This discretion suggests wider variability in saving among higher income families.2.8 (i) From equation (2.66),1β = 1n i i i x y =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑ / 21n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑.Plugging in y i = β0 + β1x i + u i gives1β = 011()n i i i i x x u ββ=⎛⎫++ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑.After standard algebra, the numerator can be written as201111in n ni i i i i i x x x u ββ===++∑∑∑.Putting this over the denominator shows we can write 1β as1β = β01n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑ + β1 + 1n i i i x u =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫⎪⎝⎭∑.Conditional on the x i , we haveE(1β) = β01n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫⎪⎝⎭∑ + β1。