Chapter 34 Vascular Thrombosis Due to Hypercoagulable States

- 格式:pps

- 大小:105.00 KB

- 文档页数:22

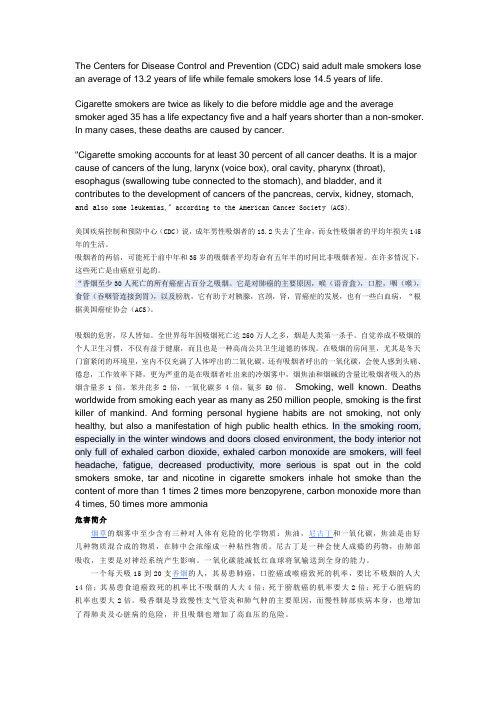

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said adult male smokers lose an average of 13.2 years of life while female smokers lose 14.5 years of life.Cigarette smokers are twice as likely to die before middle age and the average smoker aged 35 has a life expectancy five and a half years shorter than a non-smoker. In many cases, these deaths are caused by cancer."Cigarette smoking accounts for at least 30 percent of all cancer deaths. It is a major cause of cancers of the lung, larynx (voice box), oral cavity, pharynx (throat), esophagus (swallowing tube connected to the stomach), and bladder, and it contributes to the development of cancers of the pancreas, cervix, kidney, stomach, and a lso some leukemias," according to the American Cancer Society (ACS).美国疾病控制和预防中心(CDC)说,成年男性吸烟者的13.2失去了生命,而女性吸烟者的平均年损失145年的生活。

PART 14 Disorders of the Gastrointestinal SystemC HAPTER301Approach to the PatientWith Liver DiseaseM arc GhanyJ ay H.HoofnagleA diagnosis of liver disease usually can be made accurately by acareful history, physical examination, and application of a fewlaboratory tests. In some circumstances, radiologic examinationsare helpful or, indeed, diagnostic. Liver biopsy is considered thecriterion standard in evaluation of liver disease but is now neededless for diagnosis than for grading and staging of disease. This chap-ter provides an introduction to diagnosis and management of liverdisease, briefly reviewing the structure and function of the liver; themajor clinical manifestations of liver disease; and the use of clinicalhistory, physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging studies, andliver biopsy.L IVER STRUCTURE AND FUNCTIONⅥT he liver is the largest organ of the body, weighing 1–1.5 kg andrepresenting 1.5–2.5% of the lean body mass. The size and shapeof the liver vary and generally match the general body shape—longand lean or squat and square. The liver is located in the right upperquadrant of the abdomen under the right lower rib cage againstthe diaphragm and projects for a variable extent into the left upperquadrant. The liver is held in place by ligamentous attachments tothe diaphragm, peritoneum, great vessels, and upper gastrointesti-nal organs. It receives a dual blood supply; ~20% of the blood flowis oxygen-rich blood from the hepatic artery, and 80% is nutrient-rich blood from the portal vein arising from the stomach, intestines,pancreas, and spleen.T he majority of cells in the liver are hepatocytes, which constitutetwo-thirds of the mass of the liver. The remaining cell types areKupffer cells (members of the reticuloendothelial system), stellate(Ito or fat-storing) cells, endothelial cells and blood vessels, bileductular cells, and supporting structures. Viewed by light micros-copy, the liver appears to be organized in lobules, with portal areasat the periphery and central veins in the center of each lobule.However, from a functional point of view, the liver is organized intoacini, with both hepatic arterial and portal venous blood enteringthe acinus from the portal areas (zone 1) and then flowing throughthe sinusoids to the terminal hepatic veins (zone 3); the interven-ing hepatocytes constituting zone 2. The advantage of viewing theacinus as the physiologic unit of the liver is that it helps to explainthe morphologic patterns and zonality of many vascular and biliarydiseases not explained by the lobular arrangement.P ortal areas of the liver consist of small veins, arteries, bile ducts,and lymphatics organized in a loose stroma of supporting matrixand small amounts of collagen. Blood flowing into the portal areasis distributed through the sinusoids, passing from zone 1 to zone 3of the acinus and draining into the terminal hepatic veins (“centralveins”). Secreted bile flows in the opposite direction, in a counter-current pattern from zone 3 to zone 1. The sinusoids are lined byunique endothelial cells that have prominent fenestrae of variablesize, allowing the free flow of plasma but not cellular elements. Theplasma is thus in direct contact with hepatocytes in the subendothe-lial space of Disse.H epatocytes have distinct polarity. The basolateral side of thehepatocyte lines the space of Disse and is richly lined withmicrovilli; it demonstrates endocytotic and pinocytotic activity,with passive and active uptake of nutrients, proteins, and othermolecules. The apical pole of the hepatocyte forms the canalicularmembranes through which bile components are secreted. Thecanaliculi of hepatocytes form a fine network, which fuses into thebile ductular elements near the portal areas. Kupffer cells usually liewithin the sinusoidal vascular space and represent the largest groupof fixed macrophages in the body. The stellate cells are located inthe space of Disse but are not usually prominent unless activated,when they produce collagen and matrix. Red blood cells stay in thesinusoidal space as blood flows through the lobules, but white bloodcells can migrate through or around endothelial cells into the spaceof Disse and from there to portal areas, where they can return to thecirculation through lymphatics.H epatocytes perform numerous and vital roles in maintaininghomeostasis and health. These functions include the synthesis ofmost essential serum proteins (albumin, carrier proteins, coagula-tion factors, many hormonal and growth factors), the production ofbile and its carriers (bile acids, cholesterol, lecithin, phospholipids),the regulation of nutrients (glucose, glycogen, lipids, cholesterol,amino acids), and metabolism and conjugation of lipophilic com-pounds (bilirubin, anions, cations, drugs) for excretion in the bileor urine. Measurement of these activities to assess liver function iscomplicated by the multiplicity and variability of these functions.The most commonly used liver “function” tests are measurementsof serum bilirubin, albumin, and prothrombin time. The serumbilirubin level is a measure of hepatic conjugation and excretion,and the serum albumin level and prothrombin time are measuresof protein synthesis. A bnormalities of bilirubin, albumin, andprothrombin time are typical of hepatic dysfunction. Frank liverfailure is incompatible with life, and the functions of the liver aretoo complex and diverse to be subserved by a mechanical pump;dialysis membrane; or concoction of infused hormones, proteins,and growth factors.L IVER DISEASESW hile there are many causes of liver disease (T able 301-1), they gen-erally present clinically in a few distinct patterns, usually classified ashepatocellular, cholestatic (obstructive), or mixed. In h epatocellulardiseases(such as viral hepatitis or alcoholic liver disease), features ofliver injury, inflammation, and necrosis predominate. In c holestaticdiseases(such as gallstone or malignant obstruction, primary biliarycirrhosis, some drug-induced liver diseases), features of inhibitionof bile flow predominate. In a mixed pattern, features of both hepa-tocellular and cholestatic injury are present (such as in cholestaticforms of viral hepatitis and many drug-induced liver diseases). Thepattern of onset and prominence of symptoms can rapidly suggesta diagnosis, particularly if major risk factors are considered suchas the age and sex of the patient and a history of exposure or riskbehaviors.2520CHAPTER 301 Approach to the Patient With Liver DiseaseT ypical presenting symptoms of liver disease include jaundice, fatigue, itching, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, poor appe-tite, abdominal distention, and intestinal bleeding. A t present, however, many patients are diagnosed with liver disease who have no symptoms and who have been found to have abnor-malities in biochemical liver tests as a part of a routine physical examination or screening for blood donation or for insurance or employment. The wide availability of batteries of liver tests makes it relatively simple to demonstrate the presence of liver injury as well as to rule it out in someone suspected of liver disease.E valuation of patients with liver disease should be directed at(1) establishing the etiologic diagnosis, (2) estimating the disease severity (grading), and (3) establishing the disease stage (staging).TABLE 301-1 Liver Diseases2521PART 14 Disorders of the Gastrointestinal System D iagnosis should focus on the category of disease such as hepato-cellular, cholestatic, or mixed injury, as well as on the specific etio-logic diagnosis. G rading refers to assessing the severity or activity ofdisease—active or inactive, and mild, moderate, or severe. S tagingrefers to estimating the place in the course of the natural historyof the disease, whether acute or chronic; early or late; precirrhotic,cirrhotic, or end-stage.T he goal of this chapter is to introduce general, salient conceptsin the evaluation of patients with liver disease that help lead to thediagnoses discussed in subsequent chapters.C LINICAL HISTORYⅥT he clinical history should focus on the symptoms of liver disease—their nature, patterns of onset, and progression—and on potentialrisk factors for liver disease. The symptoms of liver disease includeconstitutional symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, nausea, poorappetite, and malaise and the more liver-specific symptoms of jaun-dice, dark urine, light stools, itching, abdominal pain, and bloating.Symptoms can also suggest the presence of cirrhosis, end-stage liverdisease, or complications of cirrhosis such as portal hypertension.Generally, the constellation of symptoms and their patterns of onsetrather than a specific symptom points to an etiology.F atigue is the most common and most characteristic symptomof liver disease. It is variously described as lethargy, weakness,listlessness, malaise, increased need for sleep, lack of stamina, andpoor energy. The fatigue of liver disease typically arises after activ-ity or exercise and is rarely present or severe in the morning afteradequate rest (afternoon versus morning fatigue). Fatigue in liverdisease is often intermittent and variable in severity from hour tohour and day to day. In some patients, it may not be clear whetherfatigue is due to the liver disease or to other problems such as stress,anxiety, sleep disturbance, or a concurrent illness.N ausea occurs with more severe liver disease and may accom-pany fatigue or be provoked by odors of food or eating fatty foods.Vomiting can occur but is rarely persistent or prominent. Poorappetite with weight loss occurs commonly in acute liver diseasesbut is rare in chronic disease, except when cirrhosis is present andadvanced. Diarrhea is uncommon in liver disease, except withsevere jaundice, where lack of bile acids reaching the intestine canlead to steatorrhea.R ight upper quadrant discomfort or ache (“liver pain”) occurs inmany liver diseases and is usually marked by tenderness over theliver area. The pain arises from stretching or irritation of Glisson’scapsule, which surrounds the liver and is rich in nerve endings.Severe pain is most typical of gallbladder disease, liver abscess, andsevere venoocclusive disease but is an occasional accompanimentof acute hepatitis.I tching occurs with acute liver disease, appearing early inobstructive jaundice (from biliary obstruction or drug-inducedcholestasis) and somewhat later in hepatocellular disease (acutehepatitis). Itching also occurs in chronic liver diseases, typically thecholestatic forms such as primary biliary cirrhosis and sclerosingcholangitis where it is often the presenting symptom, occurringbefore the onset of jaundice. However, itching can occur in any liverdisease, particularly once cirrhosis is present.J aundice is the hallmark symptom of liver disease and perhapsthe most reliable marker of severity. Patients usually report dark-ening of the urine before they notice scleral icterus. Jaundice israrely detectable with a bilirubin level <43 μmol/L (2.5 mg/dL).With severe cholestasis there will also be lightening of the colorof the stools and steatorrhea. Jaundice without dark urine usuallyindicates indirect (unconjugated) hyperbilirubinemia and is typicalof hemolytic anemia and the genetic disorders of bilirubin conjuga-tion, the common and benign form being Gilbert’s syndrome andthe rare and severe form being Crigler-Najjar syndrome. Gilbert’ssyndrome affects up to 5% of the population; the jaundice is morenoticeable after fasting and with stress.M ajor risk factors for liver disease that should be sought in theclinical history include details of alcohol use, medications (includ-ing herbal compounds, birth control pills, and over-the-countermedications), personal habits, sexual activity, travel, exposure tojaundiced or other high-risk persons, injection drug use, recentsurgery, remote or recent transfusion with blood and blood prod-ucts, occupation, accidental exposure to blood or needlestick, andfamilial history of liver disease.F or assessing the risk of viral hepatitis, a careful history of sexualactivity is of particular importance and should include the numberof lifetime sexual partners and, for men, a history of having sex withmen. Sexual exposure is a common mode of spread of hepatitis Bbut is rare for hepatitis C. A family history of hepatitis, liver disease,and liver cancer is also important. Maternal-infant transmissionoccurs with both hepatitis B and C. Vertical spread of hepatitis Bcan now be prevented by passive and active immunization of theinfant at birth. Vertical spread of hepatitis C is uncommon, butthere are no reliable means of prevention. Transmission is morecommon in HIV-co-infected mothers and is also linked to pro-longed and difficult labor and delivery, early rupture of membranes,and internal fetal monitoring. A history of injection drug use, evenin the remote past, is of great importance in assessing the risk forhepatitis B and C. Injection drug use is now the single most com-mon risk factor for hepatitis C. Transfusion with blood or bloodproducts is no longer an important risk factor for acute viral hepa-titis. However, blood transfusions received before the introductionof sensitive enzyme immunoassays for antibody to hepatitis C virus(anti-HCV) in 1992 is an important risk factor for chronic hepatitisC. Blood transfusion before 1986, when screening for antibody tohepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) was introduced, is also a risk fac-tor for hepatitis B. Travel to an underdeveloped area of the world,exposure to persons with jaundice, and exposure to young childrenin day-care centers are risk factors for hepatitis A. Hepatitis E isone of the more common causes of jaundice in Asia and Africa butis uncommon in developed nations, although mild cases have beenassociated with eating raw or undercooked pork or game (deer andwild boars). Tattooing and body piercing (for hepatitis B and C) andeating shellfish (for hepatitis A) are frequently mentioned but areactually quite rare types of exposure for acquiring hepatitis.A history of alcohol intake is important in assessing the causeof liver disease and also in planning management and recommen-dations. In the United States, for example, at least 70% of adultsdrink alcohol to some degree, but significant alcohol intake is lesscommon; in population-based surveys, only 5% have more thantwo drinks per day, the average drink representing 11–15 g alcohol.Alcohol consumption associated with an increased rate of alcoholicliver disease is probably more than two drinks (22–30 g) per dayin women and three drinks (33–45 g) in men. Most patients withalcoholic cirrhosis have a much higher daily intake and have drunkexcessively for ≥10 years before onset of liver disease. In assessingalcohol intake, the history should also focus on whether alcoholabuse or dependence is present. A lcoholism is usually defined bythe behavioral patterns and consequences of alcohol intake, noton the basis of the amount of alcohol intake. A buse is defined bya repetitive pattern of drinking alcohol that has adverse effects onsocial, family, occupational, or health status. D ependence is definedby alcohol-seeking behavior, despite its adverse effects. Many alco-holics demonstrate both dependence and abuse, and dependence isconsidered the more serious and advanced form of alcoholism. Aclinically helpful approach to diagnosis of alcohol dependence andabuse is the use of the CAGE questionnaire (T able 301-2), which isrecommended in all medical history-taking.25222523CHAPTER 301Approach to the Patient With Liver DiseaseFamily history can be helpful in assessing liver disease. Familial causes of liver disease include Wilson’s disease; hemochromatosis and α 1antitrypsin (α 1 A T) deficiency; and the more uncommon inherited pediatric liver diseases of familial intrahepatic cholestasis, benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis, and A lagille syndrome. Onset of severe liver disease in childhood or adolescence with a family history of liver disease or neuropsychiatric disturbance should lead to investigation for Wilson’s disease. A family history of cirrhosis, diabetes, or endocrine failure and the appearance of liver disease in adulthood should suggest hemochromatosis and lead to investigation of iron status. Adult patients with abnormal iron stud-ies warrant genotyping of the H FE gene for the C282Y and H63D mutations typical of genetic hemochromatosis. In children and ado-lescents with iron overload, other non-HFE causes of hemochro-matosis should be sought. A family history of emphysema should provoke investigation of α 1 A T levels and, if low, for Pi genotype. P HYSICAL E XAMINATION ⅥT he physical examination rarely demonstrates evidence of liver dysfunction in a patient without symptoms or laboratory findings, nor are most signs of liver disease specific to one diagnosis. Thus, the physical examination complements rather than replaces the need for other diagnostic approaches. In many patients, the physi-cal examination is normal unless the disease is acute or severe and advanced. Nevertheless, the physical examination is important in that it can be the first evidence for the presence of hepatic failure, portal hypertension, and liver decompensation. In addition, the physical examination can reveal signs that point to a specific diag-nosis, either in risk factors or in associated diseases or findings.T ypical physical findings in liver disease are icterus, hepato-megaly, hepatic tenderness, splenomegaly, spider angiomata, pal-mar erythema, and excoriations. Signs of advanced disease include muscle wasting, ascites, edema, dilated abdominal veins, hepatic fetor, asterixis, mental confusion, stupor, and coma. In males with cirrhosis, particularly when related to alcohol, signs of hyperestro-genemia such as gynecomastia, testicular atrophy, and loss of male-pattern hair distribution may be found. I cterus is best appreciated by inspecting the sclera under natural light. In fair-skinned individuals, a yellow color of the skin may be obvious. In dark-skinned individuals, the mucous membranes below the tongue can demonstrate jaundice. Jaundice is rarely detectable if the serum bilirubin level is <43 μmol/L (2.5 mg/dL) but may remain detectable below this level during recovery from jaundice (because of protein and tissue binding of conjugated bilirubin).S pider angiomata and palmar erythema occur in both acute and chronic liver disease and may be especially prominent in persons with cirrhosis, but they can occur in normal individuals and are frequently present during pregnancy. Spider angiomata are super-ficial, tortuous arterioles and, unlike simple telangiectases, typically fill from the center outward. Spider angiomata occur only on thearms, face, and upper torso; they can be pulsatile and may be dif-ficult to detect in dark-skinned individuals.H epatomegaly is not a very reliable sign of liver disease, because of the variability of the size and shape of the liver and the physical impediments to assessing liver size by percussion and palpation. Marked hepatomegaly is typical of cirrhosis, venoocclusive dis-ease, infiltrative disorders such as amyloidosis, metastatic or pri-mary cancers of the liver, and alcoholic hepatitis. Careful assess-ment of the liver edge may also demonstrate unusual firmness, irregularity of the surface, or frank nodules. Perhaps the most reliable physical finding in examining the liver is hepatic tender-ness. Discomfort on touching or pressing on the liver should be carefully sought with percussive comparison of the right and left upper quadrants.S plenomegaly occurs in many medical conditions but can be a subtle but significant physical finding in liver disease. The availabil-ity of ultrasound (US) assessment of the spleen allows for confirma-tion of the physical finding.S igns of advanced liver disease include muscle-wasting and weight loss as well as hepatomegaly, bruising, ascites, and edema. A scites is best appreciated by attempts to detect shifting dullness by careful percussion. US examination will confirm the finding of ascites in equivocal cases. Peripheral edema can occur with or with-out ascites. In patients with advanced liver disease, other factors frequently contribute to edema formation, including hypoalbumin-emia, venous insufficiency, heart failure, and medications.H epatic failure is defined as the occurrence of signs or symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy in a person with severe acute or chronic liver disease. The first signs of hepatic encephalopathy can be subtle and nonspecific—change in sleep patterns, change in personality, irritability, and mental dullness. Thereafter, confusion, disorienta-tion, stupor, and eventually coma supervene. In acute liver failure, excitability and mania may be present. Physical findings include asterixis and flapping tremors of the body and tongue. F etor hepati-cus refers to the slightly sweet, ammoniacal odor that can occur in patients with liver failure, particularly if there is portal-venous shunting of blood around the liver. Other causes of coma and dis-orientation should be excluded, mainly electrolyte imbalances, sed-ative use, and renal or respiratory failure. The appearance of hepatic encephalopathy during acute hepatitis is the major criterion for diagnosis of fulminant hepatitis and indicates a poor prognosis. In chronic liver disease, encephalopathy is usually triggered by a medi-cal complication such as gastrointestinal bleeding, over-diuresis, uremia, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, infection, constipation, or use of narcotic analgesics.A helpful measure of hepatic encephalopathy is a careful mental status examination and use of the trail-making test, which consists of a series of 25 numbered circles that the patient is asked to con-nect as rapidly as possible using a pencil. The normal range for the connect-the-dot test is 15–30 seconds; it is considerably delayed in patients with early hepatic encephalopathy. Other tests include drawing abstract objects or comparison of a signature to previous examples. More sophisticated testing such as with electroencepha-lography and visual evoked potentials can detect mild forms of encephalopathy, but are rarely clinically useful.O ther signs of advanced liver disease include umbilical hernia from ascites, hydrothorax, prominent veins over the abdomen, and c aput medusa , which consists of collateral veins seen radiating from the umbilicus and resulting from the recanulation of the umbilical vein. Widened pulse pressure and signs of a hyperdynamic circu-lation can occur in patients with cirrhosis as a result of fluid and sodium retention, increased cardiac output, and reduced peripheral resistance. Patients with long-standing cirrhosis and portal hyper-tension are prone to develop the hepatopulmonary syndrome,defined by the triad of liver disease, hypoxemia, and pulmonary∗One “yes” response should raise suspicion of an alcohol use problem, and more than one is a strong indication that abuse or dependence exists.PART 14 Disorders of the Gastrointestinal System arteriovenous shunting. The hepatopulmonary syndrome is char-acterized by platypnea and orthodeoxia, representing shortnessof breath and oxygen desaturation that occur paradoxically uponassuming an upright position. Measurement of oxygen saturationby pulse oximetry is a reliable screening test for the presence ofhepatopulmonary syndrome.S everal skin disorders and changes occur commonly in liver dis-ease. Hyperpigmentation is typical of advanced chronic cholestaticdiseases such as primary biliary cirrhosis and sclerosing cholangitis.In these same conditions, xanthelasma and tendon xanthomataoccur as a result of retention and high serum levels of lipids andcholesterol. A slate-gray pigmentation to the skin also occurs withhemochromatosis if iron levels are high for a prolonged period.Mucocutaneous vasculitis with palpable purpura, especially on thelower extremities, is typical of cryoglobulinemia of chronic hepatitisC but can also occur in chronic hepatitis B.S ome physical signs point to specific liver diseases. Kayser-Fleischer rings occur in Wilson’s disease and consist of a golden-brown copper pigment deposited in Descemet’s membrane at theperiphery of the cornea; they are best seen by slit-lamp examination.Dupuytren contracture and parotid enlargement are suggestive ofchronic alcoholism and alcoholic liver disease. In metastatic liverdisease or primary hepatocellular carcinoma, signs of cachexia andwasting may be prominent, as well as firm hepatomegaly and ahepatic bruit.L ABORATORY TE STINGⅥD iagnosis in liver disease is greatly aided by the availability of reli-able and sensitive tests of liver injury and function. A typical batteryof blood tests used for initial assessment of liver disease includesmeasuring levels of serum alanine and aspartate aminotransferases(ALT and AST), alkaline phosphatase (AlkP), direct and total serumbilirubin, and albumin and assessing prothrombin time. The patternof abnormalities generally points to hepatocellular versus cholestaticliver disease and will help to decide whether the disease is acute orchronic and whether cirrhosis and hepatic failure are present. Basedon these results, further testing over time may be necessary. Otherlaboratory tests may be helpful, such as γ-glutamyl transpeptidase(gGT) to define whether alkaline phosphatase elevations are due toliver disease; hepatitis serology to define the type of viral hepatitis;and autoimmune markers to diagnose primary biliary cirrhosis (anti-mitochondrial antibody; A MA), sclerosing cholangitis (peripheralantineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; P-A NCA), and autoimmunehepatitis (antinuclear, smooth-muscle, and liver-kidney microsomalantibody). A simple delineation of laboratory abnormalities andcommon liver diseases is given in T able 301-3.T he use and interpretation of liver function tests is summarizedin Chap. 302.D IAGNOSTIC IMAGINGⅥT here have been great advances made in hepatic imaging, althoughno method is suitably accurate in demonstrating underlying cirrho-sis. There are many modalities available for imaging the liver. US,CT, and MRI are the most commonly employed and are comple-mentary to each other. In general, US and CT have a high sensitivityfor detecting biliary duct dilatation and are the first-line optionsfor investigating the patient with suspected obstructive jaundice.A ll three modalities can detect a fatty liver, which appears brighton imaging studies. Modifications of CT and MRI can be used toquantify liver fat, which may ultimately be valuable in monitoringtherapy in patients with fatty liver disease. Magnetic resonancecholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic retrogradecholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are the procedures of choicefor visualization of the biliary tree. MRCP offers several advantagesover ERCP; there is no need for contrast media or ionizing radia-tion, images can be acquired faster, it is less operator dependent,and it carries no risk of pancreatitis. MRCP is superior to US andCT for detecting choledocholithiasis but less specific. It is useful inthe diagnosis of bile duct obstruction and congenital biliary abnor-malities, but ERCP is more valuable in evaluating ampullary lesionsand primary sclerosing cholangitis. ERCP allows for biopsy, directvisualization of the ampulla and common bile duct, and intraductalultrasonography. It also provides several therapeutic options inpatients with obstructive jaundice such as sphincterotomy, stoneextraction, and placement of nasobiliary catheters and biliary stents.Doppler US and MRI are used to assess hepatic vasculature andhemodynamics and to monitor surgically or radiologically placedvascular shunts such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemicshunts. CT and MRI are indicated for the identification and evalu-ation of hepatic masses, staging of liver tumors, and preoperativeassessment. With regard to mass lesions, sensitivity of hepaticimaging continues to increase; unfortunately, specificity remainsa problem, and often two and sometimes three studies are neededbefore a diagnosis can be reached. Recently, methods using elastog-raphy have been developed to measure hepatic stiffness as a meansof assessing hepatic fibrosis. US and MR elastrography are nowAbbreviations: HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, HEV: hepatitis A, B, C, D, or E virus; HBsAg,hepatitis B surface antigen; anti-HBc, antibody to hepatitis B core (antigen); HBeAg,hepatitis e antigen; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; SMA, smooth-muscle antibody;P-ANCA, peripheral antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.2524。

表面技术第53卷第9期医用介入导丝用疏水和亲水涂层的研究进展李涛1,马迅1,刘平1,王静静1,张柯1,马凤仓1,杨文艺2,李伟1*(1.上海理工大学 材料与化学学院,上海 200093;2.上海交通大学 医学院附属第一人民医院心血管临床医学中心,上海 200080)摘要:医用介入导丝被广泛应用于各类介入手术,是目前经皮冠状动脉成形(PTCA)术及经皮血管成形术(PTA)中常用的医疗器械之一。

在医用介入导丝表面添加亲水或疏水涂层,可以减小导丝在临床应用中的组织摩擦和组织损伤,有效提高导丝的通过性、抗菌性和生物相容性,减少炎症。

综述了近年来国内外医用介入导丝亲水和疏水涂层材料,介绍了这些涂层的机理、附着力优化、抗菌修饰等方面内容,重点介绍了聚四氟乙烯、聚乙烯吡咯烷酮、聚丙烯酰胺、聚乙二醇、聚对二甲苯等涂层材料体系的研究进展,介绍了不同材料体系在医用导丝亲水和疏水涂层的作用机理和实际应用,同时介绍了亲疏水涂层的制备工艺,重点阐述了层层自组装、紫外光接枝、等离子体接枝和化学气相沉积等制备方法的可操作性、优势和劣势。

最后在总结前人研究成果的基础上,对医用介入导丝涂层的现状及面临的问题进行了探讨,并对医用介入导丝涂层的发展方向及提高涂层综合性能等方面进行了展望。

关键词:医用介入导丝;润滑性;亲水涂层;疏水涂层;表面改性;抗菌抑菌中图分类号:TB34 文献标志码:A 文章编号:1001-3660(2024)09-0102-15DOI:10.16490/ki.issn.1001-3660.2024.09.010Research Progress of Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Coatingsfor Medical Interventional GuidewiresLI Tao1, MA Xun1, LIU Ping1, WANG Jingjing1, ZHANG Ke1,MA Fengcang1, YANG Wenyi2, LI Wei1*(1. School of Materials and Chemistry, University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai 200093, China;2. Cardiovascular Medical Center, Shanghai General Hospital, School of Medicine, ShanghaiJiao Tong University, Shanghai 200080, China)ABSTRACT: Medical interventional guidewires are widely used in various interventional procedures and are commonly used medical devices in percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA).Although the size of the interventional guidewire is quite small in the whole medical device system, it is used in a large amount in clinical practice. With the rapid development of the medical device industry, medical interventional guidewires are becoming more and more common in clinical applications. The coating on the surface of medical interventional guidewires works as an收稿日期:2023-05-16;修订日期:2023-08-08Received:2023-05-16;Revised:2023-08-08基金项目:国家自然科学基金(51971148)Fund:National Natural Science Foundation of China (51971148)引文格式:李涛, 马迅, 刘平, 等. 医用介入导丝用疏水和亲水涂层的研究进展[J]. 表面技术, 2024, 53(9): 102-116.LI Tao, MA Xun, LIU Ping, et al. Research Progress of Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Coatings for Medical Interventional Guidewires[J]. Surface Technology, 2024, 53(9): 102-116.*通信作者(Corresponding author)第53卷第9期李涛,等:医用介入导丝用疏水和亲水涂层的研究进展·103·important support for application promotion and function expansion. The attachment of hydrophilic or hydrophobic coating on the surface of guidewires has received extensive attention from researchers. The addition of hydrophilic or hydrophobic coatings to the surface of medical interventional guidewires can reduce tissue friction and tissue damage in clinical applications, effectively improve the passage, antimicrobial and biocompatibility of the guidewires, and reduce inflammation. The coating may peel off from the surface due to weak bonding, leading to adverse events. In recent years, there have been successive reports focusing on coating shedding, the hazards of which include residual coating debris in patients, local tissue reactions and vascular thrombosis, and can even lead to serious adverse events including embolic stroke, tissue cell necrosis and death, so a more comprehensive and rational means of surface modification is necessary to make the guide wire surface coating with good hydrophilic or hydrophobic premise, not only with good adhesion and the surface modification must be carried out in a more comprehensive manner, so that the surface coating of the guidewire not only has good adhesion and solidity, but also has good biocompatibility and antibacterial and antibacterial properties.This paper firstly introduced the clinical use scenario and application performance requirements of medical interventional guidewires. It not only explained the importance of surface lubricant coating, but also reviewed the different coating materials of hydrophilic and hydrophobic coatings for medical interventional guidewires at home and abroad in recent years from the performance requirements, and conducted research on mechanism exploration, adhesion optimization, and antimicrobial modification for these coatings. The hydrophobic coating repelled water molecules and made the surface of the guidewire wax-like and smooth, which not only reduced the friction of the guidewire, but also improved the tactile feedback of the guidewire during use. PTFE was widely used for hydrophobic coating of medical guidewires due to its good stability and low coefficient of friction. Surface hydrophobic modification was also an excellent means of modification using polyurethane acrylic coating in addition to PTFE. Hydrophilic coating had the advantages of good biocompatibility, good wettability, low protein adsorption, low risk of thrombosis, etc. The modified substrate surface not only showed good hydrophilicity and lubricity, but also showed better anti-fouling properties than the unmodified substrate surface, while the ultra-thin hydrophilic coating did not lead to changes in the hardness and mechanical properties of the substrate. Hydrophilic coatings for medical guidewires were characterized by chemical stability, biocompatibility, and antithrombotic effects, and the main material systems were polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), polyacrylamide (PAM), poly (parylene), polyethylene glycol (PEG), and hyaluronic acid (Hyaluronan) etc. The mechanism of action of different material systems in hydrophilic and hydrophobic coating of medical guidewires as well as the preparation processes of the coatings, including layer-by-layer self-assembly, UV grafting, plasma grafting, and chemical vapor deposition, etc., were also presented, with emphasis on the operability, advantages, and disadvantages of these preparation processes. When introducing hydrophilic and hydrophobic coating materials, some of the actual hydrophobic and hydrophilic coated guide wire models currently available in the market were also introduced, taking guide wires as an example. Finally, on the basis of summarizing the previous research results, the current status and problems faced by hydrophilic and hydrophobic coatings for medical interventional guidewires were discussed. Although hydrophilic and hydrophobic coatings have been widely studied, most of the current studies focus on or are limited to a single treatment or property of hydrophilic and hydrophobic coatings, and there are fewer reports of studies on the composite properties of the coatings, especially the hydrophilic, hydrophobic, and antimicrobial properties that are related to clinical medical treatment.Therefore, the article concludes with an outlook on the future development direction of hydrophilic-hydrophobic coatings for medical interventional guidewires and the improvement of the comprehensive performance of hydrophilic-hydrophobic coatings for medical interventional guidewires.KEY WORDS: medical interventional guidewire; lubricity; hydrophilic coating; hydrophobic coating;surface modification;antibacterial and antimicrobialf介入诊疗操作是介于常规疗法(如外科、内科)之间的新兴治疗方法,包括血管内介入和非血管介入。

・综述・血管型白塞病的发病机制王之冕,李璐,郑文洁作者单位:100730北京,中国医学科学院北京协和医学院北京协和医院风湿免疫科风湿免疫病学教育部重点实验室,国家皮肤与免疫疾病临床医学研究中心通信作者:郑文洁E-mail:zhengwj@DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-8705.2020.06.015【摘要】白塞病(Behgefs disease,BD)是一种病因及发病机制尚不明确的慢性全身性血管炎性疾病,其中有血管受累的被称为血管型BD(Vasculo-Behget*disease)。

本文从中性粒细胞活化、内皮细胞损伤、凝血功能障碍3个方面描述血管型BD发病机制,为临床治疗和疾病管理提供参考。

【关键词】白塞病;血管炎;中性粒细胞活化;内皮损伤;凝血障碍基金项目:国家自然科学基金(81871299)Pathogenesis of vasculo-Behget's disease WANG Zhi-mian,LI Lu,ZHENG Wen-jieDepartment of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology,Peking Union Medical College Hospital,ChineseAcademy of Medical Sciences&Peking Union Medical College,Key Laboratory of Rheumatology&Clinical Im-munology,Ministry of Education,National Clinical Research Center for Dermatologic and Immunologic Diseases(NCRC-DID),Beijing100730,ChinaCorresponding author:ZHENG Wen-jie,E-mail:zhengwj@[Abstract]Behcet's disease(BD)is a chronic systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology and pathogenesis.The involvement of the vascular system,which dominates the clinical picture in Behcet's disease,is termed vas-culo-Behget's disease.This article aims to describe the pathogenesis of vasculo-BD from three aspects includingneutrophil activation,endothelial dysfunction,and coagulation disorders,so as to provide references for clinicaltreatment and disease management.[Key words]Behcet's disease;vasculitis;neutrophil activation;endothelial dysfunction;coagulation disordersFund program:National Natural Science Foundation of China(81871299)白塞病(Behget's disease,BD)是一种慢性全身性血管炎性疾病,以反复发作的口腔、生殖器溃疡、皮肤病变和眼病为主要特征,可累及胃肠、血管、中枢神经等全身多系统[1]。

Chapter 34 Vascular Thrombosis Due to Hypercoagulable StatesErika LuAugust 22, 2005Vascular Surgery ConferenceEpidemiology●Thrombosis is the major cause of death in the world●MI and stroke (arterial thrombosis) are the #1 and #2killer worldwide●Molecular defects increase a patient’s risk for thrombosis in 18%-30% of all cases of venous thromboembolism●Arterial thrombosis more likelyenvironmental/acquired cause rather than inherited disorderPK Kallikrein PlasminogenXII XIIa C4bBP PAI-1XIa Protein S PlasminIXa APC Insol Fibrin FDPVIIIaVIIa-TF Xa FVL Sol FibrinVa ATII G20210A ThrombinHCII FibrinogenPK Kallikrein PlasminogenXII XIIa C4bBP PAI-1XIa Protein S PlasminIXa APC Insol Fibrin FDPVIIIaVIIa-TF Xa FVL Sol FibrinVa ATII G20210A ThrombinHCII Fibrinogen●White clot –platelet rich●Rare to see arterial thrombus in a healthy vessel●Usually atherosclerotic change with…●Diabetes●Hyperlipidemia●Tobacco use●Acquired procoagulant states (i.e. HIT and antiphosholipid antibodies●Manifests in large vessel occlusions●MI and stroke●Peripheral vascular occlusive disease●There are genetic polymorphisms that may increase your risk, but not really predictive of risk of thrombus when you look at large population studies●Elevated factor VII●Elevated fibrinogen●Hyperhomocysteinemia●Elevated lipoprotein a●Red clot –RBC’s trapped in fibrin strands ●Virchow’s Triad: vessel wall change,hypercoagulability and stasis have a major role!●Classic Protein Deficiencies:●Antithrombin III deficiency●Protein C deficiency●Protein S deficiency●Less common causes for thrombosis●Abnormal fibrinogen●Abnormal plasminogen●Elevated factors XI, IX, and VIII●Hematologic conditions that cause hypercoagulability●TTP●HUS●DIC●Polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia●Acquired Risk Factors:●Immobility●Obesity●Chronic neurologic disease●Cardiac disease●Pregnancy, use of OCP’s●Surgery, particularly thoracoabdominal, ortho, GYN●Trauma●Malignancy●Nephrotic syndrome●Interesting Factoids on Cancer and VTE●Occult cancer in 0.5 –5% of VTE pts●3x more likely to get cancer in next 3 yrs ifidiopathic VTE●19% of cancer pts have a VTE●Chemo increases risk of VTE because itincreases tissue factor and expression of E-selectin, thereby increasing thrombuspotentialAntithrombin Deficiency (1-2%) Site VenousMech AT is a serine protease inhibitor (SERPIN) of thrombin, kallikrein, factors Xa, IXa, VIIa, XIIa, XIa.Congenital: autosomal dominant; heterozygotes liveAcquired: liver dz, malignancy, sepsis, malnutrition,ESRD, DICDx Cannot be adequately anticoagulated on heparin (heparin potentiates anticoagulant effect of AT)-check AT Ag and AT activityTx-heparin + FFP (2 u q8 hr 1 u q12 hr)-hirudin, argatroban, bivalirudin (direct thrombininhibitor)-lifelong anticoagulationProtein C and S Deficiencies (2-5%) Site Venous, occasional arterialMech Protein C: inactivates Factos Va & VIIa less thrombin -also stimulates t-PA liberation, ↑ fibrinolysisProtein S: cofactor to APC, regulated by C4b-free protein S is an active anticoagulantCongenital: autosomal dominant; heterozygotes liveAcquired: liver failure, DIC, nephrotic syndromeDx Low Protein C or S Ag levelsTx-anticoagulate with heparin, then lifelong-only tx those that are sx’atic, since many subclinical,but aggressive periop ppx if genotype knownHeparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia & ThrombosisSyndrome (up to 30%)Site Venous, occasional arterialMech Heparin-dependent IgG has and Fc receptor that causes platelets to aggregate together-starts 3-14 days after initiation of heparinDx-suspect if plts ↓ by 50% or if Plts<100K-suspect if thrombosis in unusual area-ELISA usually used, but SRA more accurateTx-stop all heparin, including flushes-coumadin only if initially used w/ other anticoagulantdue to initial prothrombotic state-cannot use LMW heparin (92% cross-reactivity)-Hirudin or argatroban or abciximabLupus Anticoagulant/Antiphospholipid Syndrome Site Venous, occasional arterialMech IgG against β2 glycoprotein I and prothrombin.-lots of theories on mechanisms (inhibits APCactivation, increase PAI-1 levels, directly activates plts,endothelial cell activation, ↑ tissue factor-5-16x ↑ risk thrombosis, graft thrombosis in 27-50%-33% pts will have at least one thrombotic eventDx-prolonged APTT-↑ antiphospholipid or anticardiolipin Ab titer-prolonged Russell viper venom time ↓ by addingexcess phospholipidsTx-heparin, then coumadin to keep INR >3-heparin or LMW heparin in pregnancy (ck Factor Xa)Factor V Leiden (resistance to APC)Site Venous, occasional arterial, LE revascularizations Mech Resistance to inactivation of Factor Va by APC asa a result of substitution of a glutamine for arginine in theprotein for Factor V-Heterozygotes have 7-fold increased risk-Homozygotes have 80-fold increased risk-RR 2.4 for recurrent VTE, more if taking OCP,pregnant, concurrent prothrombin 20210ADx-clot based assayTx-heparin, then coumadin-long-term coumadin controversial b/c of low risk ofrecurrent VTE (RR only 2.4)Hyperhomocysteinemia (10%)Site Venous = ArterialMech-homocysteine elevation injures endothelial cells -in combo with factor V Leiden, ↑ risk thrombosis-RR 2.5Dx-fasting homocysteine levelsTx-folate supplements-long-term benefit has not been shown in literatureProthrombin G20210 Polymorphism (4-6%)Site Venous > ArterialMech-genetic polymorphism, G20210A, in the prothrombin gene causes it to be expressed at higher levels-2-7 fold increase in VTE-only increase arterial thrombus risk if you smoke-↑risk in pregnant women and women with early MI’s-syngergistic with factor V LeidenDx-genetic analysis for 20210 mutationTx-Lifelong anticoagulation if you have recurrent VTE’s or concurrent factor V LeidenDefective Fibrinolysis, Dysfibrinogenemia, andLipoprotein (a)Site Venous = ArterialMech-abnormal fibrinogens: defective thrombin binding or resistant to plasmin-mediated brkdwn;digital ischemia-Lp (a) + LDL is atherogenic and prothrombotic;assoc with childhood VTEDx-fibrinogen clotting activity-to-Ag ratio-prolonged thrombin clotting or reptilase time-serum lipoprotein (a)Tx-”standard of anticoagulation therapy”-too few documented cases to understand the truelong-term riskAbnormal Platelet AggregationSite Arterial > Venous, thrombus in peripheral vasc reconMech-hyperactive or hyperresponsive platelets-diabetes worsens condition-seen s/p CEA, in advanced uterine or lung CADx-Check if platelets respond to a platelet agonist (i.e.ADP, epinephrine, collagen) at concentreations belownormalTx-”standard of anticoagulation therapy”-too few documented cases to understand the truelong-term risk-ASA or clopidigrel may helpElevated Procoagulant Factors: VIII, IX, XISite Venous > ArterialMech-Factor VIII: if above 90th percentile, 5-fold ↑ risk -Factor XI: if above 90th percentile, 2-fold ↑ riskDx-Direct measure of factors with activity assayTx-”standard of anticoagulation therapy”What tests do we order?●Antithrombin activity and antigen assay●Protein C activity and antigen assay●Free protein S antigen assau●APC resistance assay●Factor V Leiden by PCR●Homocysteine level●Prothromnin G20210A by PCR●Antiphospholipid or anticardiolipin Ab●Clottable fibrinogen and fibrinogen antigen●Dilute Russell viper venom time●Tissue thromboplastin inhibition time●Β2 glycoprotein I antibodies●PT/PTT●D-dimerSuggested Treatment Algorithm3-6 months Aggessive ppxanticoag for 2nd VTEYesVTE Acute IdentifiableTherapy Risk/EtiologyNoTest for Hypercoag? 6 monthsState Neg Anticoagulation+Low risk recurHi-risk recurrence Life-longanticoagulation。