语义学汇总

- 格式:doc

- 大小:182.00 KB

- 文档页数:18

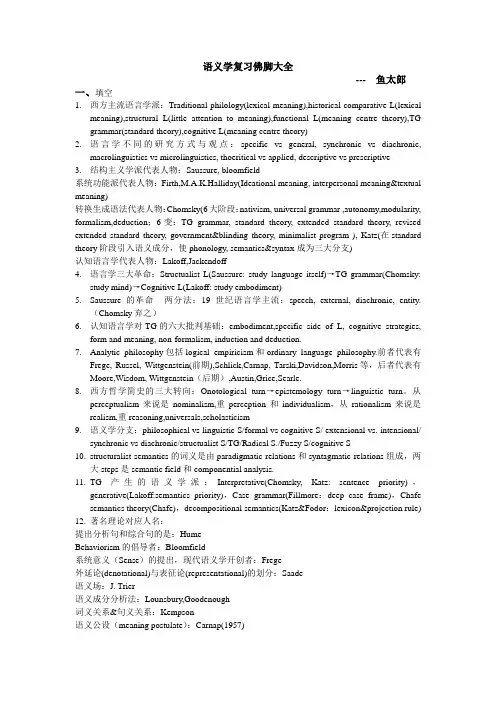

语义学复习佛脚大全--- 鱼太郎一、填空1.西方主流语言学派:Traditional philology(lexical meaning),historical comparative L(lexicalmeaning),structural L(little attention to meaning),functional L(meaning centre theory),TG grammar(standard theory),cognitive L(meaning centre theory)2.语言学不同的研究方式与观点:specific vs general, synchronic vs diachronic,macrolinguistics vs microlinguistics, thoeritical vs applied, descriptive vs prescriptive3.结构主义学派代表人物:Saussure, bloomfield系统功能派代表人物:Firth,M.A.K.Halliday(Ideational meaning, interpersonal meaning&textual meaning)转换生成语法代表人物:Chomsky(6大阶段:nativism, universal grammar ,autonomy,modularity, formalism,deduction;6变:TG grammar, standard theory, extended standard theory, revised extended standard theory, government&blinding theory, minimalist program ), Katz(在standard theory阶段引入语义成分,使phonology, semantics&syntax成为三大分支)认知语言学代表人物:Lakoff,Jackendoff4.语言学三大革命:Structualist L(Saussure: study language itself)→TG grammar(Chomsky:study mind)→Cognitive L(Lakoff: study embodiment)5.Saussure的革命-- 两分法:19世纪语言学主流:speech, external, diachronic, entity.(Chomsky弃之)6.认知语言学对TG的六大批判基础:embodiment,specific side of L, cognitive strategies,form and meaning, non-formalism, induction and deduction.7.Analytic philosophy包括logical empiricism和ordinary language philosophy.前者代表有Frege, Russel, Wittgenstein(前期),Schlick,Carnap, Tarski,Davidson,Morris等,后者代表有Moore,Wisdom, Wittgenstein(后期),Austin,Grice,Searle.8.西方哲学简史的三大转向:Onotological turn→epistemology turn→linguistic turn。

语义学课期末总结_期末工作总结

语义学是研究语言的意义和词义的学科。

在本学期的语义学课程中,我学习了语义学的基本概念、主要理论框架以及相关的研究方法和技巧。

通过这门课程,我对语言意义的产生和表达有了更深入的理解,并且掌握了一些基础的分析和解释方法。

在学习词义学的内容时,我对词义的组成和划分有了更深入的了解。

词汇是构成语言的基本单位,它的意义由多个组成成分构成,包括符号本身、外延和内涵等。

我们学习了一些常见的词义关系,如上下位关系、同义关系和反义关系等,并且通过实例分析来加深了对这些关系的理解。

在学习句义学的内容时,我学习了句子的意义是如何通过结构和语用信息来产生和表达的。

我们学习了一些句子的基本意义类型,如描述句、陈述句、疑问句和祈使句等,并且掌握了分析和解释这些句子的方法。

我们也学习了一些常见的句义关系,如逻辑关系、因果关系和条件关系等,通过分析句子之间的关系来推断和理解句子的意义。

在学习实践语义学的内容时,我们学习了一些实际应用的技能和技巧。

我们学习了如何使用语料库来分析和研究语义现象,如词义变化、语义演化和语义隐喻等。

我们还学习了如何进行实证研究,通过实验和调查来验证和支持语义学的理论和假设。

语义学课期末总结_期末工作总结

语义学是一个对语言意义的研究领域,涉及到词汇、句法和语境等方面的内容。

在本学期的学习中,我对语义学的基本原理和方法有了更深入的了解,并在课程中获得了一些重要的收获。

我学习了语义学的基本概念和术语。

我了解到词汇是语言意义的基本单位,它们通过不同的词义和语境来构成不同的句子。

词汇的意义可以通过句法结构和语境来确定,这是语义学的一个重要研究方向。

我还学习了一些常见的语义关系,如同义关系、反义关系、上下位关系等,这些关系对理解语言意义起到重要的指导作用。

我学习了一些常见的语义分析方法。

语义分析是将语言中的词汇和句子转化为形式化的表示,以便进一步分析其意义。

逻辑语义是一种常用的语义分析方法,它将自然语言的意义转化为逻辑形式,并通过逻辑规则进行推理和分析。

语义角色标注也是一种常见的语义分析方法,它将句子中的词汇与其在句子中扮演的语义角色进行对应。

这些语义分析方法在自然语言处理和人工智能领域有着广泛的应用,对机器翻译、信息检索等任务起到重要的支持作用。

通过本学期的学习,我对语义学的基本原理和方法有了系统的了解,并认识到语义学在实际应用中的重要性和挑战。

学习语义学让我对语言的意义有了更深刻的理解,也为我今后从事相关研究和工作奠定了基础。

希望将来能进一步深入研究语义学,并将其应用于实际问题的解决中。

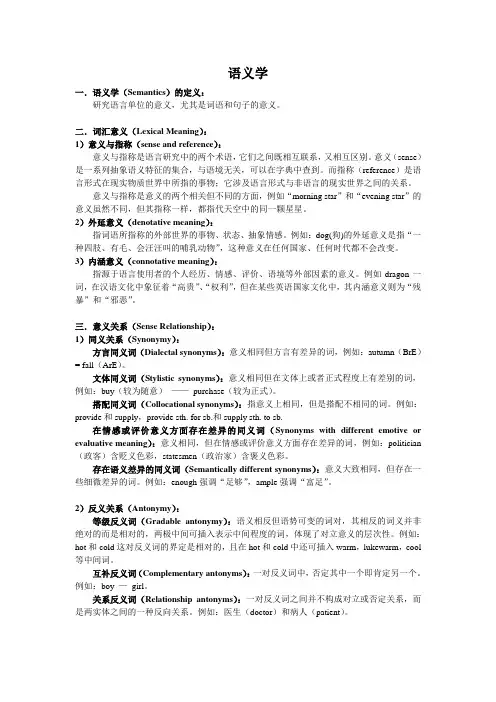

语义学一.语义学(Semantics)的定义:研究语言单位的意义,尤其是词语和句子的意义。

二.词汇意义(Lexical Meaning):1)意义与指称(sense and reference):意义与指称是语言研究中的两个术语,它们之间既相互联系,又相互区别。

意义(sense)是一系列抽象语义特征的集合,与语境无关,可以在字典中查到。

而指称(reference)是语言形式在现实物质世界中所指的事物;它涉及语言形式与非语言的现实世界之间的关系。

意义与指称是意义的两个相关但不同的方面,例如“morning star”和“evening star”的意义虽然不同,但其指称一样,都指代天空中的同一颗星星。

2)外延意义(denotative meaning):指词语所指称的外部世界的事物、状态、抽象情感。

例如:dog(狗)的外延意义是指“一种四肢、有毛、会汪汪叫的哺乳动物”,这种意义在任何国家、任何时代都不会改变。

3)内涵意义(connotative meaning):指源于语言使用者的个人经历、情感、评价、语境等外部因素的意义。

例如dragon一词,在汉语文化中象征着“高贵”、“权利”,但在某些英语国家文化中,其内涵意义则为“残暴”和“邪恶”。

三.意义关系(Sense Relationship):1)同义关系(Synonymy):方言同义词(Dialectal synonyms):意义相同但方言有差异的词,例如:autumn(BrE)= fall(ArE)。

文体同义词(Stylistic synonyms):意义相同但在文体上或者正式程度上有差别的词,例如:buy(较为随意)——purchase(较为正式)。

搭配同义词(Collocational synonyms):指意义上相同,但是搭配不相同的词。

例如:provide和supply,provide sth. for sb.和supply sth. to sb.在情感或评价意义方面存在差异的同义词(Synonyms with different emotive or evaluative meaning):意义相同,但在情感或评价意义方面存在差异的词,例如:politician (政客)含贬义色彩,statesmen(政治家)含褒义色彩。

语言学知识_语义学语义学一.语义学(Semantics)的定义:研究语言单位的意义,尤其是词语和句子的意义。

二.词汇意义(Lexical Meaning):1)意义与指称(sense and reference):意义与指称是语言研究中的两个术语,它们之间既相互联系,又相互区别。

意义(sense)是一系列抽象语义特征的集合,与语境无关,可以在字典中查到。

而指称(reference)是语言形式在现实物质世界中所指的事物;它涉及语言形式与非语言的现实世界之间的关系。

意义与指称是意义的两个相关但不同的方面,例如“morning star”和“evening star”的意义虽然不同,但其指称一样,都指代天空中的同一颗星星。

2)外延意义(denotative meaning):指词语所指称的外部世界的事物、状态、抽象情感。

例如:dog(狗)的外延意义是指“一种四肢、有毛、会汪汪叫的哺乳动物”,这种意义在任何国家、任何时代都不会改变。

3)内涵意义(connotative meaning):指源于语言使用者的个人经历、情感、评价、语境等外部因素的意义。

例如dragon一词,在汉语文化中象征着“高贵”、“权利”,但在某些英语国家文化中,其内涵意义则为“残暴”和“邪恶”。

三.意义关系(Sense Relationship):1)同义关系(Synonymy):方言同义词(Dialectal synonyms):意义相同但方言有差异的词,例如:autumn(BrE)= fall(ArE)。

文体同义词(Stylistic synonyms):意义相同但在文体上或者正式程度上有差别的词,例如:buy(较为随意)——purchase(较为正式)。

搭配同义词(Collocational synonyms):指意义上相同,但是搭配不相同的词。

例如:provide和supply,provide sth. for sb.和supply sth. to sb.在情感或评价意义方面存在差异的同义词(Synonyms with different emotive or evaluative meaning):意义相同,但在情感或评价意义方面存在差异的词,例如:politician (政客)含贬义色彩,statesmen(政治家)含褒义色彩。

《语义学基础知识综合性概述》一、引言语义学作为语言学的一个重要分支,研究语言的意义,对于我们理解和运用语言起着至关重要的作用。

从日常交流到文学创作,从学术研究到人工智能,语义学的影响无处不在。

本文将全面阐述语义学的基础知识,包括基本概念、核心理论、发展历程、重要实践以及未来趋势。

二、基本概念1. 语义的定义语义是指语言所表达的意义,包括词汇意义、句子意义和语篇意义等。

它涉及到语言符号与所指代的事物、概念、情感之间的关系。

2. 语义单位语义学中常见的语义单位有词素、词汇、短语和句子等。

词素是最小的有意义的语言单位,词汇是由词素组成的词语,短语是由词汇组成的语言片段,句子则是表达完整意义的语言单位。

3. 语义特征语义特征是指词汇或语言单位所具有的特定意义属性。

例如,“红色”这个词汇具有“色彩鲜艳”“暖色调”等语义特征。

语义特征可以帮助我们区分不同的词汇和语言单位,理解它们的意义和用法。

三、核心理论1. 指称理论指称理论关注语言符号与外部世界的关系,探讨语言如何指代现实中的事物和概念。

指称可以分为直接指称和间接指称。

直接指称是指语言符号直接指代具体的事物或概念,如“苹果”这个词汇直接指代一种水果。

间接指称则是通过隐喻、转喻等修辞手法来指代事物或概念。

2. 涵义理论涵义理论研究语言符号所蕴含的意义和情感。

涵义可以分为概念涵义和情感涵义。

概念涵义是指词汇或语言单位所表达的客观概念,如“汽车”这个词汇的概念涵义是一种交通工具。

情感涵义则是指词汇或语言单位所表达的主观情感和态度,如“美丽”这个词汇的情感涵义是积极的、赞赏的。

3. 语义场理论语义场理论认为词汇不是孤立存在的,而是处于相互关联的语义网络中。

同一语义场中的词汇具有相似的意义和用法,它们之间的关系可以是同义关系、反义关系、上下义关系等。

例如,“红色”“蓝色”“绿色”等词汇属于颜色语义场,它们之间是并列关系。

4. 语用学与语义学的关系语用学研究语言在实际使用中的意义和效果,与语义学密切相关。

语义学笔记整理第⼀章作为语⾔学⼀个分⽀的语义学语义学的建⽴以法国学者⽶歇尔·布勒阿尔1897年7⽉出版《语义学探索》为标记。

该书1900年翻译为英⽂“语义学:意义科学的研究(Semantics:Studies in the Science of Meaning)”。

这本专著材料丰富,⽣动有趣,重点在词义的历史发展⽅⾯,兼顾词汇意义和语法意义。

全书共三编:1,讲词义变化的定律,介绍变异、扩散、类推等概念;2,讲如何确定词义,介绍释义、⽐喻、多义、命名等;3,讲词类、词序、组合规则等,涉及语法意义。

除了语⾔学的语义学,还有逻辑学的语义学,哲学的语义学,还有⼼理学家对语义的研究。

a,逻辑学的语义学是对逻辑形式系统中符号解释的研究,⼜称“纯语义学”,对象并⾮⾃然语⾔的语义。

b,哲学的语义学围绕语义的本质展开涉及世界观的讨论。

“语义学”或“语义哲学”⼜是本世纪前半叶盛⾏于西⽅的⾄今仍有影响的⼀个哲学流派的名称。

c,⼼理学家研究语义,主要是想了解⼈们在信息的发出和接收中的⼼理过程。

d,语⾔学的语义学把语义作为语⾔(乃⾄⾔语)的⼀个组成部分、⼀个⽅⾯进⾏研究,研究它的性质,内部结构及其变异和发展,语义间的关系等等。

布勒阿尔的书给语义的发展以重要地位,声称研究语义的变化构成了语义学。

同时它把语义限制在“词语”的意义上,主要是词义上。

这两个特点⼀直贯穿在他以后半个多世纪的若⼲代表性著作⾥。

继布勒阿尔之后,⼀部有世界影响的语义学专著是两位英国学者奥格登和理查兹合写,1923年出版的《意义的意义》(The Meaning of Meaning)。

这两位学者还曾共同创制了后来遭到各种⾮议的“基本英语”(Basic English).从30年代到50年代后期,以美国布龙菲尔德的理论为代表的结构主义统治着西⽅语⾔学。

布龙菲尔德认为,研究语义学的⼈须是万事皆通的博学者,语⾔学家⽆法担此重任,语⾔学家关⼼的是语⾔的形式。

一、语义学视角下语义的表现(一)王寅教授的分析(1)说话人意义(speaker‟s meaning), 受话人的意义(hearer‟s meaning)[语言交际过程中参与者的角色分析](2)自然意义(natural meaning)和非自然意义(unnatural meaning)(3)词素义(morpheme meaning), 词义(word meaning), 句义(sentence meaning), 话词义(utterance meaning), 语篇义(discourse meaning)(4)内涵义(intensional meaning )与外延义(extentional meaning)[从哲学和逻辑学角度](5)概念意义和附加意义(conceptual meaning and added meaning)(二)、Leech 对意义的区分七种Leech recognizes seven types of meaning in his Semantics1)Conceptual meaning :logical, cognitive, or denotative content2)Connotative meaning: What is communicated by virtue of what language refers to3)Social meaning: What is communicated of the social circumstances of language use4)Affective meaning: What is communicated of the feelings and attitudes of the speaker/writer5)Reflected meaning : What is communicated through association with another sense of the same expression6)Collocative meaning: What is communicated through association with words which tend to occur in the environment ofanother word7)Thematic meaning: What is communicated by the way in which the message is organized in terms of order andemphasis.以下为对上述的解释1、自然意义,非自然意义Natural meaning and non-natural meaningNatural meaning and nonnatural meaning is put forward by Grice in his famous article “Meaning”.As for natural meaning, there is the evidential relationship between a cause and its effect. An example of natural meaning is “Those spots mean measles.” “x means y” is related to “x shows that y,” “x is a symptom of y” and “x lawfully correlates with y”. Those spots on little Jimmy do not really mean measles in natural meaning, if Jimmy does not have measles, even if the spots typically correlate with measles.Nonnatural meaning pertains to language and communication. It means words and speakers. On nonnatural s ense, “x means y” is closer to “x says/asserts that y”, “x expresses y”. And when “x means y” is the case, it will usually be true that someone, or some group, means something by x. In nonnatural sense, it can be true that “x means y” even though x obtains when y is not the case. Thus our speaker might indeed have meant that you should bring more whisky, when in reality you should not: his meaning it, in nonnatural sense, does not make it so.In Grice‟s opinion, nonnatural meaning is used to induce some bel ief in hearer. More than that, it is used to induce the belief by getting the addressee to recognize the intention to induce a belief: in meaning something, then speaker does not merely cause the hearer to have a belief, he/she overtly gives the speaker a reason to believe, the reason being that he/she wants the speaker to believe. Thus what a person means, in the nonnatural sense, comes down to his/her complex mental states, especially intentions.2、关于听话人,说话人The Speaker and the ListenerTo ensure smooth communication between the speaker and the listener, it is important to nail down the role of them and the interaction between them. Some basic linguistics theory, such as Speech Act Theory, the Cooperative Principle, Conversational Implicatures, the Politeness Principle, atc.will help learners to well understand the role of the speaker and the listener.Speech act is actions performed via utterances. In English, it is commonly given more specific labels, such as apology, complaint, compliment, invitation, promise, or request. These descriptive terms for different kinds of speech acts apply to the speaker's communicative intention in producing an utterance. The speaker normally expects that his or her communicative intention will be recognized by the hearer. Both speaker and hearer are usually helped in this process by the circumstances surrounding the utterance.We know that quite often a speaker can mean a lot more than what is said. The problem is to explain how the speaker can manage to convey more than what is said and how the hearer can arrive at the speaker‟s meaning. H. P. Grice believes that there must be some mechanisms governing the production and comprehension of these utterances. He suggests that there is a set of assumptions guiding the conduct of conversation. This is what he calls the Cooperative Principle (CP).According to Grice, conversational implicatures can arise from either strictly and directly observing or deliberately and openly flouting the maxims, that is, speakers can produce implicatures in two ways: observance and non-observance of the maxims. The least interesting case is when speakers directly observe the maxims so as to generate conversational implicatures. If the hearer wants to accurately export the conversational implicatures, he or she should know something about the the following aspects: 1)conventionality implicatures of the utterance; 2)cooperative principle and criteria; 3)the context of the utterance; 4)some common background knowledge of the speaker and the listener.In most cases, the indirectness is motivated by considerations of politeness. Politeness is usually regarded by most pragmatists as a means or strategy which is used by a speaker to achieve various purposes, such as saving face, establishing and maintaining harmonious social relations in conversation, thus to promote better communication between the speaker and the listener.3、句义,词义,话语意义,命题意义,篇章意义从哲学方面以及语言学方面对其进行分析;它们在不同语境中状态;结合法律举例1) Word meaningWord is a unit of expression that has universal intuitive recognition by native speakers, whether it is expressed in spoken or written form.Sense and reference are two terms often encountered in the study of word meaning. They are two related but different aspects of meaning. Sense is concerned with the inherent meaning of the linguistic form. It is the collection of all the features of the linguistic form: it is abstract and de-contextualized. Reference means what a linguistic form refers to in the real physical world; it deals with the relationship between the linguistic element and the non-linguistic world of experience. Obviously, linguistic forms having the same sense may have different references in different situations. On the other hand, there are also occasions, when linguistic forms with the same reference might differ in sense. A very good example is the two expressions “morning star” and “evening star”. These two differ in sense but as a matter of fact, what they refer to is the same: the very same star that we see in the sky.According to Wittegenstein, words like tools, the meaning of word depends on the usage of the word. In another word, the meaning of word depends on the function of the word. The meaning of a word rests with the usage of the word in a language. Words are different tools in language. These tools are characterized by their usage. Sometimes, he did not see words as tools, however, he said directly: languages are tools. The different concepts in language are different tools.2) Sentence Meaning:(句子意义是构成句子的词汇意义和结构意义共同作用的结果)The meaning of a sentence is often studied as the abstract, intrinsic property of the sentence itself in terms of predication. It is obvious that the sentence meaning is connected with the meaning of the words which constitute the sentence; but it is stillclear that the sentence meaning is not the totality of the meanings of the component words because the syntactical structure of the sentence also plays a role in determining the sentence meaning. That is to say, the meaning of a sentence is a product of both lexical and grammatical meaning. Lexical meaning is the de-contextual denotation of the words which is defined in the dictionary, while the grammatical meaning is abstract meaning represented by the grammatical structures of the words. Semantic relations:(句子之间的关系:同义,反义,蕴含)Synonymy: the sameness in meaning between sentences.Antonymy: the oppositeness in meaning between sentences.eg: “Overruled.” “反对无效。

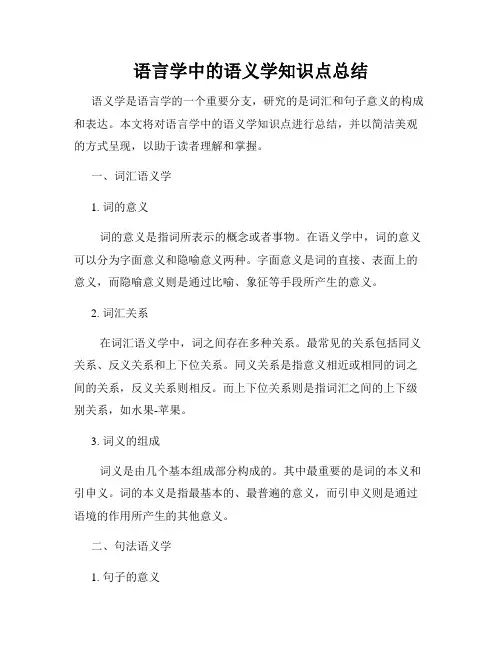

语言学中的语义学知识点总结语义学是语言学的一个重要分支,研究的是词汇和句子意义的构成和表达。

本文将对语言学中的语义学知识点进行总结,并以简洁美观的方式呈现,以助于读者理解和掌握。

一、词汇语义学1. 词的意义词的意义是指词所表示的概念或者事物。

在语义学中,词的意义可以分为字面意义和隐喻意义两种。

字面意义是词的直接、表面上的意义,而隐喻意义则是通过比喻、象征等手段所产生的意义。

2. 词汇关系在词汇语义学中,词之间存在多种关系。

最常见的关系包括同义关系、反义关系和上下位关系。

同义关系是指意义相近或相同的词之间的关系,反义关系则相反。

而上下位关系则是指词汇之间的上下级别关系,如水果-苹果。

3. 词义的组成词义是由几个基本组成部分构成的。

其中最重要的是词的本义和引申义。

词的本义是指最基本的、最普遍的意义,而引申义则是通过语境的作用所产生的其他意义。

二、句法语义学1. 句子的意义句子的意义是由词汇意义的组合和句法结构所决定的。

句法语义学研究句子中各个成分之间的关系以及句子整体的意义。

其中包括主谓关系、动宾关系、修饰关系等。

2. 语法词汇和逻辑词汇语法词汇是指在句子中起到语法功能的词汇,如冠词、连词等。

逻辑词汇则是指在句子中起到表示逻辑关系的词汇,如因果词、转折词等。

这些词汇在句法语义学中扮演着重要的角色。

三、篇章语义学1. 篇章结构和语义关系篇章语义学研究文本中句子之间的组织关系和意义关系。

其中包括衔接关系、因果关系、对比关系等。

这些关系决定了整篇文章的意义和连贯性。

2. 信息结构信息结构是指篇章中信息的安排和呈现方式。

其中包括主题句、背景信息、前提条件等。

通过合理的信息结构,可以使文章更加清晰、连贯。

四、语用语义学1. 语言的使用和意义语用语义学研究语言的使用情境和意义的关系。

语言在不同的情境中可能产生不同的意义,而这种意义的变化通过语用语义学可以进行解释和分析。

2. 言语行为言语行为是指在交际中通过语言完成的各种行为,如陈述、询问、命令等。

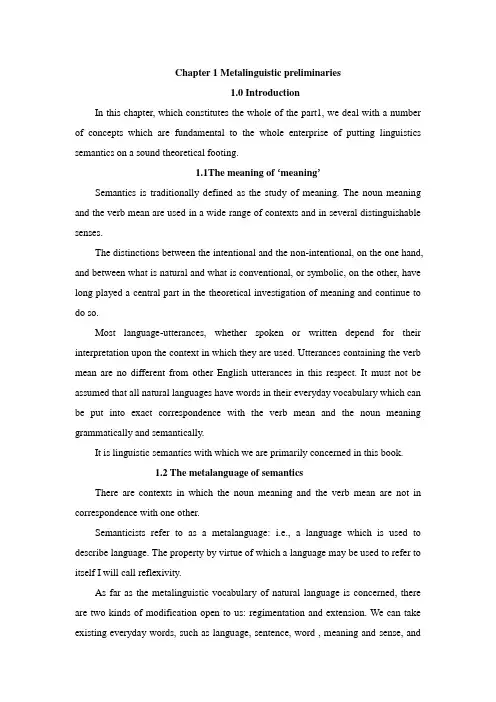

Chapter 1 Metalinguistic preliminaries1.0 IntroductionIn this chapter, which constitutes the whole of the part1, we deal with a number of concepts which are fundamental to the whole enterprise of putting linguistics semantics on a sound theoretical footing.1.1The meaning of ‘meaning’Semantics is traditionally defined as the study of meaning. The noun meaning and the verb mean are used in a wide range of contexts and in several distinguishable senses.The distinctions between the intentional and the non-intentional, on the one hand, and between what is natural and what is conventional, or symbolic, on the other, have long played a central part in the theoretical investigation of meaning and continue to do so.Most language-utterances, whether spoken or written depend for their interpretation upon the context in which they are used. Utterances containing the verb mean are no different from other English utterances in this respect. It must not be assumed that all natural languages have words in their everyday vocabulary which can be put into exact correspondence with the verb mean and the noun meaning grammatically and semantically.It is linguistic semantics with which we are primarily concerned in this book.1.2 The metalanguage of semanticsThere are contexts in which the noun meaning and the verb mean are not in correspondence with one other.Semanticists refer to as a metalanguage: i.e., a language which is used to describe language. The property by virtue of which a language may be used to refer to itself I will call reflexivity.As far as the metalinguistic vocabulary of natural language is concerned, there are two kinds of modification open to us: regimentation and extension. We can take existing everyday words, such as language, sentence, word , meaning and sense, andsubject them to strict control, defining them or re-defining them for our own purposes.As far as the everyday metalinguistic use of the spoken language is concerned, there are certain rules and conventions which all native speakers follow without ever having been taught them and without normally being conscious of them. But these have not been fully codified and cannot prevent misunderstanding in all contexts.1.3 Linguisic and non-linguistic semanticsThe term linguistic semantics is ambiguous. Given that semantics is the study of meaning, linguistic semantics can be held to refer either to the study meaning in so far as this is expressed in language or, alternatively, to the study of meaning within linguistics. Linguistics does not aim to deal with everything that falls within the scope of the word language, it establishes its own theoretical framework.One kind of non-arbitrariness is commonly referred to these days as iconicity. Roughly speaking, an iconic sign is one whose form is explicable in terms of similarity between the form of the sign and what is signifies: signs which lack this property of similarity are non-iconic.Spoken utterances, in particular, will contain, in addition to the words of which they are composed, a particular intonation-contour and stress-pattern: these are referred to technically as prosodic features. They are an integral part of the utterances in which they occur, and they must not be thought of as being in any sense secondary or optional. The prosodic features of spoken languages and the paralinguistic gestures that are associated with spoken utterances in particular languages in particular cultures vary from languages to language and have to be learned as part of the normal process of language –acquisition.1.4 Language, speech and utterance; ‘langue’and ‘parole’; ‘competence’and ‘performance’The English word ‗language‘, like the word meaning, has a wide range of meaning. But the first and most important point to be made about the world ‘language‘ is that it is categorically ambivalent with the respect to the semantically relevant property of countability: i.e., it can be used as a count noun; itcan also be used as a mass noun, which does not require a determiner and which normally denotes not an individual entity or set of entities, but an unbounded mass or aggregate of stuff or substance.Expressions containing the words English, French, German, etc. exhibit a related, but rather different, kind of system-product ambiguity when they are used as mass nouns in the singular. The syntactic ambivanlence upon which the ambiguity turns, is not between count nouns and mass nouns, but between proper nouns and common nouns.One way of avoiding ambiguity is to adopt the policy of never using the English word language metalinguistically as a mass noun when the expression containing it could be replaced, without change of meaning, with an expression containing the plural form of language used as a count noun. Another way of avoiding, or reducing, the ambiguity and confusion caused by the syntactic ambivalence of the everyday English word language and by its several meaning is to coin a set of more specialized terms to replace it.The word langue always refers to language-system. The word parole has a number of related, overlapping and meanings in everyday French. The essential distinction is between a system and the products of the system.By ―competence‖ Chomsky means the language-system which is stored in the brains of individuals who are said to know the language in question. The Chomskyan term ―performance‖ is often employed by linguistics to refer indifferently both to the use of the system and to the products of the use of the system. ‗Parole‘, in contrast, employed to refer to anything other than the products of the use of particular language-system.1.5 Words: forms and meaningsIn this book, single quotation-marks will be employed for words, and for other composite units with both form and meaning; italics for forms and double quotation-marks for meanings.The grammatically distinct forms of a word are traditionally described asinflectional, some languages are much more highly inflected than others. It is nevertheless important to draw a distinction between a word and its form, even if it has no distinct inflectional forms.Homonyms: different words with the same form. For example, ‗bank1‘, one of whose meaning is ―financial institution‖ and the ‗bank2‘, one of whose meaning is ―sloping side of a river‖, are generally regarded as homonyms.The fact that two or more phonetically different forms may be orthographically identical is also readily illustrated from English. This kind of identity may be called material identity.1.6 Sentences and utterances; text, conversation and discourseThe meaning of a sentence is determined not only by the meaning of the words of which it is composed, but also by its grammatical structure. This is clear from the fact that two sentences can be composed of exactly the same words.In everyday English, the word utterances is generally used to refer to spoken language. The word text is generally refer to written language. Our language must not be confused with speech. Indeed, one of the most striking properties of natural language is their relative independence of the medium in which they are realized.The terms utterance, discourse and conversation have both a process-sense, they denote a particular kind of behaviour , or activity; in their product-sense, they denote, not the activity itself, but the physical product of the activity. Sentence meaning is context-independent, whereas utterance meaning is not: that is to say, the meaning of an utterance is determined by the context in which it is uttered. And there is an intrinsic connexion between the meaning of sentence and the characteristic use,not of the particular sense as such, but of the whole class of sentences to which the sentence belongs by virtue of its grammatical structure. This connection may be formulated, for one class of sentences, as follows: a declarative sentence is one that belongs to the class of sentences whose members are used to make statement.Sentence-meaning is related to utterance-meaning by virtue of the notion characteristic use, but it differs from it in that the meaning of a sentence isindependent of the particular context in which it may be uttered. To determine the meaning of an utterance,we have to take contextual into account.1.7 Theories of meaning and kinds of meaningThe distinction between descriptive and the non-descriptive: with regard to descriptive meaning, it is a universally acknowledged fact that languages that can be used to make descriptive statements which are true or false according to whether the propositions that they express are true or false. Non-descriptive meaning is more heterogeneous and less central. Expressive meaning-i.e. , the kind of meaning by virtue of which speakers express, rather than describe , their beliefs, attitudes and feelings-is often held to fall within the scope of stylistics or pragmatics.Chapter2 Words as Meaningful Unit2.0 IntroductionIt is generally agreed that the words, phrases and sentences of natural languages have meaning, that sentences are composed of words and that the meaning of a sentence is a product of the words of which it is composed.The technical term dictionary-word is lexeme. A lexeme is a lexical unit: the unit of the lexicon. The lexical structure of a language is the structure of its lexicon, or vocabulary. Not all words are lexemes, and not all lexemes are words.2.1 Forms and expressionsThe American philosopher Peirce referred to as the distinction between words as tokens and words as types. It is word expressions, not word forms, that are listed and defined in a conventional dictionary. According to an alphabetic ordering of their citation-forms; what are commonly referred to the head-words of the dictionary entries. In order to assign meaning to the word forms of which a sentence is composed, we mast be able to identify them, not merely as tokens of a particular type, but as forms of particular expressions. And tokes of the same type are not necessarily forms of the same expression.Not all words are listed in a dictionary are words. Some of them are what are traditionally called phrases; and phrasal expressions, like word-expressions, must bedistinguish in principle from the form or forms with which they are put into correspondence by the inflectional rules of the language. And in many languages, they are productive rules for what is traditionally called word-formation, which enable their users to construct new word-expression out of pre-existing lexically simpler expressions.The distinction that has been drawn between lexically simple expressions and lexically composite expressions is not as straightforward, it will depend on the model or theory of grammar with which the linguist is operating. The meaning of a sentence is determined partly by the meaning of the words of which it is composed and partly by its grammatical meaning.2.2 Homonymy and polysemy; lexical and grammatical ambiguityHomonyms are traditionally defined as different words with the same form. But the definition is still defective in that it fails to take account of the fact that, in many languages, most lexemes have not one, but several forms. Also, it says nothing about grammatical equivalence. Absolute homonyms will satisfy the following three conditions:(1) they will be unrelated in meaning;(2) all their forms will be identical;(3) the identical forms will be grammatically equivalent. Absolute homonymy is common enough, but there are also many different kinds of what I will call partial homonymy: i.e., cases where (a) there is identity of one form and (b) one or two, but not all three, of the above conditions are satisfied.2.3 SynonymySynonymy means that expressions with the same meaning are synonymous. It makes identity of meaning the criterion of synonymy, but not merely similarity. Near—synonymy refers to expressions that are more or less similar, but not identical in meaning. Partial synonymy means that synonymy meets the criterion of identity of descriptive meaning, but difference in context and expression.2.4 Full and empty word-formFull word-forms and empty word-forms equal to open-class word-forms and closed-class word-forms respectively.Empty word-forms in English and other typologically similar languages, will have a purely grammatical meaning.Full word-forms will have both a lexical and grammatical meaning.2.5 Lexical meaning and grammatical meaningCategorical meaning is one part of grammatical meaning: it is that part of the meaning of lexemes which derives from their being members of one category rather than another.Lexicon refers to theoretical counterpart of a dictionary. The lexicon is the set of all the lexemes in a language, stored in the brains of competent speakers.Grammatical meaning of the full word-forms is relevant with tense, mood, aspect, gender and person.Chapter 3 Defining the meaning of words3.0 IntroductionReferential theory of meaning is defined as the theory of meaning which relates the meaning of a word to the thing it refers to or stands for.3.1 Denotation and senseDenotation is intrinsically connected with reference. Some words may be put into correspondence with classes of entities in the external world by means of the relation of denotation.The crucial difference between reference and denotation is that the denotation of an expression is invariant and utterance-independent. Reference, in contrast, is variable and utterance-dependent.Sense is a matter of interlexical and intralingual relations: that is to say, of relations which hold between a lexical expression and one or more other lexical expressions in the same language.Sense and denotation apply equally to lexically simple and lexically composite expressions.Sense and denotation are interdependent in that one would not normally know the one without having at least some knowledge of the other.3.2 Basic and non-basic expressionsObject-words are defined logically as words having meaning in isolation and psychologically as words which have been learnt without its being necessary to have previously learnt any other words.Dictionary-words are theoretically superfluous and learnt in terms of the logically and psychologically more basic object-words.Ostensive definition would involve pointing at one or more entities denoted by the word in question and saying, That is a(n) X. But the notion of ostensive definition has some criticism. An expression being defined ostensively must understand the meaning of the demonstrative pronoun ―that‖ in the utterance That is a(n) X, or alternatively of the gesture that serves the same purpose. They must also realize what more general purpose is being served by the utterance or gesture in question. And it is easy to overlook the importance of this component of the process of ostensive definition.Phenomenal attributes (those attributes can be known or perceived through the senses) and functional attributes (those attributes make things useful to us for particular purposes) are determinable factors of denotation.3.3 Natural (and cultural) kindsNatural kinds refer to classes whose members have the same nature or essence.Words denoting natural kinds in the traditional sense might be thought to differ semantically from words denoting what is called cultural kinds.Natural kinds in the traditional sense are often combined and divided by languages, sometimes arbitrarily but often for culturally explicable reasons.3.4 Semantic prototypesThe notion of semantic prototypes is invoked initially, in lexical semantics and in the definition of words denoting natural kinds. And now the notion of semantic prototype has been applied not only to nouns denoting cultural kinds, but to various subclasses of verbs and adjectives, including colour-terms. The notion of semantic prototypes is also adopted to the checklist theory of definition.Chapter 4 The structural approach4.0 IntroductionThe lexical structure of a language can be regarded as a network of sense-relations: it is like a web in which each strand is one such relation and each knot in the web is a different lexeme.There are two approaches to describe the semantic structure of words: componential analysis and the use of meaning-postulates.4.1 Structural semanticsStructural semantics is an influential contemporary position, which is still in its early stages of analyzing the sense, relations that interconnect lexemes and sentences. Structural semantics is the study of relationships between the meanings of terms within a sentence and how meaning can be composed from smaller elements.4.2 Componential analysis (lexical decomposition)The conceptual meaning can be broken down into its minimal distinctive components which are known as semantic features. Such an analysis is called componential analysis. Plus and minus signs are used to indicate whether a certain semantic features is present or absent in the meaning of a word, and these feature symbols are usually written in capitalized letters. For example, the word ―man‖ is analyzed as consisting of the semantic features of [+HUMAN, +ADULT, +ANIMATE, +MALE].One advantage of CA is that by specifying the semantic features of certain words, it will be possible to show how these words are related in meanings. Another advantage is that it enables us to have an exact knowledge of the conceptual meaning of a word.One of its chief drawbacks is the impossibility of making a list of the infinite number of semantic features. CA is hard for us to find a set of features that capture what is common in meaning across lexical item. Thousands of words don‘t fit into such sets of contrasts, like kindness, window et which seem to have very general features like abstract or physical object and then nothing but their unique senses.CA is insufficient for the analysis of the sense in the context. For example, it is easer to analyze the components of ―man‖. However, one can hardly explain the meaning of man in t he sentence or context such as ―Be a man‖.4.3 The empirical basis for componential analysisCA provides linguistics with a systematic and economical means of representing the sense-relations that hold among lexemes in particular languages and on the assumption that the components are universal across languages.Although CA is defective both theoretically and empirically, it can also be implied to prototypical theory and presupposition theory.4.4 Entailment and possible worldsEntailment plays an important role in all theories of meaning, and a more central role in some than in others. It should be noted, first of all, that entailment has been defined as a relation between propositions. Propositions may be either necessarily or contingently true. A necessarily true proposition is one that is true in all possible circumstances: or, as the seventeenth-century German philosopher, Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) put it, in all possible worlds. A contingently true proposition, on the other hand, is one whose truth-value might have been, or might be, different in other circumstances.When can envisage a possible world, or a possible state of the world, of which it is not true. This intuitively comprehensible notion of possible worlds has been formalized in various ways in modern modal logic. For logic purposed, a possible world may be identified with the set of propositions that truly describe it. It is under this interpretation of ‗world‘ that one talks of propositions being true in, rather than of, a world. According to Kant, a proposition is analytically true if the meaning of the subject is contained in that of the predicate and can be revealed by analysis. An analytically true proposition is one which necessarily true by virtue of its meaning-one which can be shown to be true by analysis. Any proposition that is not analytic is, by definition, synthetic.A logically true proposition is one whose truth-value is determined solely by thelogical form of the proposition. Logical truths constitute one of two kinds of necessary truths. Moreover, if logical form is held to be a part of the meaning of propositions, logical truths are a subclass of analytic truths. First of all, there are propositions which, if true, are true by virtue of the laws of nature. The qualification, ―if true‖, is important. We must never confuse the epistemological statue of a proposition with its truth-value.There is a difference between a proposition‘s being true and a proposition‘s being held to be true. Propositions do not change their truth-value; their epistemological status, on the other hand, is subject to revision in the light of new information, changes in the scientific or cultural frame of reference which determines a society‘s generally accepted ontological assumptions, etc. As we have recognized cultural kinds, in addition to natural kinds, so we might recognize cultural necessity, in addition to natural necessity. The consideration of possibilities such as this makes us realize that semantic entailment is by no means as clear-cut as it is often held to be. Many sentences are not only fully meaningful, but usable to assert what might be a true proposition in some possible world.4.5 Sense-relations and meaning-postulatesSense-relations are of two kinds: substitutional and combinatorial. Substitutional relations are those which hold between intersubstitutionable members of the same grammatical category; combinational relations hold typically, though not necessarily; between expressions of different grammatical categories, which can be put together in grammatically well-formed combinations. It is intuitively obvious, a more specific, lexically and grammatically simpler, expression may be more or less descriptively equivalent to a lexically composite expressions are combined.Only two kinds of substitutional relations of sense will be dealt with in detail here: hyponymy and incompatibility. They are both definable in terms of entailment.The relation of hyponymy is exemplified by such pairs of expressions as dog and animal, of which the former is a hyponym of the latter: the sense of dog includes that animal. Entailment, as we can see in the previous section, is a relation that holdsbetween propositions. Generally speaking, the use of meaning-postulates has been seen by linguistics as an alternative to componential analysis. Looked at from this point of view, the advantage of meaning-postulates over classical or standard versions of componential analysis is that they do not presuppose the exhaustive decomposition of the sense of a lexeme into an integral number of universal sense-components. They can be defined for lexemes as such, without making any assumptions about atomic concepts or universality, and they can be used to give a deliberately incomplete account of the sense of a lexeme.The second kind of substitutional sense-relation to be mentioned here is incompatibility, which is definable in terms of entailment and negation. Complimentarity is often treated as a kind of antonymy. But antonymy in the narrowest sense-polar antonymy differs from complementarity in virtue of gradability. This means that the conjunction of two negated antonyms is not contradictory. In fact, expressins with the meanings more good and more bad are two-place converses. They are like corresponding active and passive verb-expressions and also like such pairs of lexemes as husband and wife.Chapter5 Meaningful and meaningless sentences5.0 IntroductionIn my view, it is much easier to understand the truth-conditional theory of meaning and to see both its strengths and its weaknesses if one knows something about its processor, the verificationist theory, and the philosophical context in which verificationism arose. That there is a connexion between meaning and truth is almost self-evident and has long been taken for granted by philosophers. In this chapter, we take out first steps towards seeing how this intuitive connexion between meaning and truth has been explicated and exploited in modern linguistic semantics.5.1 Grammaticality, acceptability and meaningfulnessAs was noted in an earlier chapter, some utterances, actual or potential, are both grammatical and meaningful; others are ungrammatical and meaningless; and yet others, though fully grammatical and perhaps also meaningful, are for various reasons,unacceptable. To say that an utterance is unacceptable is to imply that it is unutterable in all normal contexts other than those involving metalinguistic reference to them. Many such utterances are unacceptable for socio-cultural reasons.Or again, in some cultures, it might be unacceptable for a social inferior to address a social superior with a second-person pronoun, whereas it would be perfectly acceptable for a superior to address an inferior or an equal with the pronoun in question: this is the case in many cultures. Somewhat different are those dimensions of acceptability which have to do with rationality and logical coherence.5.2 The meaningfulness of sentencesSentences are, by definition, grammatically well-formed. There is no such thing, therefore, as an ungrammatical sentence. Sentences however may be either meaningful or meaningless. Utterances, in contrast with sentences, may be either grammatical or ungrammatical everyday circumstances are ungrammatical in various respects. Some of these are interpretable without difficulty in the context in which they occur. Indeed, they might well be regarded by most of those who are competent in the language in question as fully acceptable.Nevertheless, to say that the distinction between grammatical and semantic well-formedness and consequently between grammar and semantics is not clear-out in all instances is not to say that it is never clear-out at all. There are other, actual or potential, utterances which we can classify, no less readily, as grammatical, but meaningless. Of course, none of these is uninterpretable, if it is appropriately contextulized and the meaning of one or more of its component expression is extended beyond its normal, or literal, lexical meaning by means of such traditionally recognized rhetorical principles as metaphor, metonymy or synecdoche.The expressions well-formed and ill-formed first came into linguistics as part of the terminology of generative grammar: as they are commonly employed, they imply conformity to a set, or system, of precisely formulated rules or principles.5.3 Corrigibility and translatabilityOne of the criteria that was invoked earlier in connexion with grammaticality iswhat we may now label the criterion of corrigibility. Other kinds of unacceptability can be a matter of meaning, also fall within the scope of the notion of corrigibility.Another criterion that is sometimes mentioned by linguists is translatability. This rests on the view that semantic, but not grammatical, distinctions can be matched across languages. The criterion of translatability can supplement, but it does not supplant, our main criterion, that of corrigibility.5.4 Verifiability and verificationismThe cerificationist theory of meaning-verificationism was originally associated with the philosophical movement known as logical positivism, initiated by members of the Vienna Circle in the period immediately preceding the Second World War. Although logical positivism, and with it verificationism, is all but dead, it has been of enormous importance in the development of modern philosophical semantics.5.5 Propositions and propositional contentAyer‘s formulation of the verifiability criterion draws upon the distinction between sentences and propositions. The nature of propositions is philosophically controversial, but those philosophers who accept that propositions differ, on the one hand, from sentences and, on the other, from statements, questions, commands, etc.Ayer talks of sentences as purporting to express propositions, and it is easy to see why. The purport of a document is the meaning that it conveys by virtue of its appearance, or face-value, and standard assumptions about the interpretation of the author‘s intentions. Sentences of whatever kind may be uttered, in various circumstances, without there being any question of the assertion or denial of a proposition.Sentence meaning is intrinsically connected with utterance-meaning, but can be distinguished from it by virtue of the distinction between the characteristic use of a sentence and its use on particular occasions.5.6 Non-factual significance and emotivismEmotivism-the thesis that in making what purport to be factual statements in ethics and aesthetics one is not saying anything that is true or false, but giving vent to。

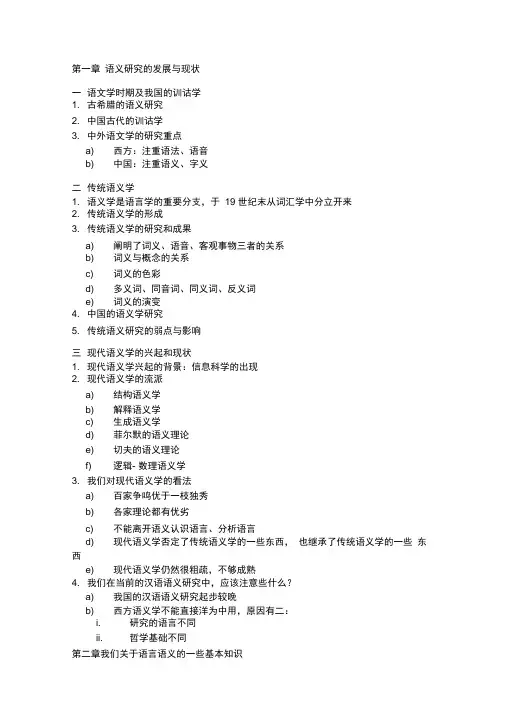

第一章语义研究的发展与现状一语文学时期及我国的训诂学1. 古希腊的语义研究2. 中国古代的训诂学3. 中外语文学的研究重点a) 西方:注重语法、语音b) 中国:注重语义、字义二传统语义学1. 语义学是语言学的重要分支,于19 世纪末从词汇学中分立开来2. 传统语义学的形成3. 传统语义学的研究和成果a) 阐明了词义、语音、客观事物三者的关系b) 词义与概念的关系c) 词义的色彩d) 多义词、同音词、同义词、反义词e) 词义的演变4. 中国的语义学研究5. 传统语义研究的弱点与影响三现代语义学的兴起和现状1. 现代语义学兴起的背景:信息科学的出现2. 现代语义学的流派a) 结构语义学b) 解释语义学c) 生成语义学d) 菲尔默的语义理论e) 切夫的语义理论f) 逻辑- 数理语义学3. 我们对现代语义学的看法a) 百家争鸣优于一枝独秀b) 各家理论都有优劣c) 不能离开语义认识语言、分析语言d) 现代语义学否定了传统语义学的一些东西,也继承了传统语义学的一些东西e) 现代语义学仍然很粗疏,不够成熟4. 我们在当前的汉语语义研究中,应该注意些什么?a) 我国的汉语语义研究起步较晚b) 西方语义学不能直接洋为中用,原因有二:i. 研究的语言不同ii. 哲学基础不同第二章我们关于语言语义的一些基本知识一语言是人类的基本工具之一1. 手、语言、人脑是人类进化的产物2. 文字和计算机对加强和延伸语言的作用很重要3. 计算机是语言继文字之后的又一次突破二语言的功能1. 语言是交际工具2. 语言是思维工具三语言结构1. 语言包括语音、语法、语义三个部分2. 语义作为语言结构的重要价值四语义系统1. 语义与语音、语法的不同2. 语音、语法、语义是相互依存、缺一不可的3. 语音、语法是为语义服务的,语义不是为语音、语法服务的4. 语音、语法的研究对研究语义的意义五语义单位1. 各种语义单位a) 义位:义项b) 义素:义位的组成部分c) 语素义:构词语素的意义d) 义丛:词组的意义,是义位的组合,有固定义丛和自由义丛之分e) 句义:句子的意义f) 言语作品义:言语或作品的篇章意义g) 附加义:某些义位、句义和言语作品义的附加意义成分2. 语义单位的几种关系a) 语义单位与语音的关系b) 语义单位与语法的关系c) 语义单位与语言、言语的关系六语义类型1. 广义的语义a) 反映义i. 基本义和附加义ii. 指称意义与系统意义b) 语法意义:汉语中各种语法成分的内容2. 狭义的语义:语义学研究的语言、言语的内容部分或意义方面七人是怎样认识语义的1. 认识义位2. 认识义丛、句义和言语作品义3. 认识语素义八语义与语言反映的各种现象的关系1. 语义层的各方面都是外部世界的反映a)语义层的各方面:义素、语素义、义位、义丛、句义、言语作品义、义位、句义的附加成分、语义场b)反映外部世界是语言的语义层及其各种单位和所有成分的本质属性c)了解语义必须要从社会生产、生活习惯、历史文化来理解2. 语义对社会的能动作用:语义对社会、心理、大自然有极大的能动作用第三章义素分析法一义素分析法的提出是不可避免的1. 训诂学把词义(义位)当作一个囫囵的整体,具有很大的局限性2•传统语义学虽然有所发展,但仍把词义(义位)当作一个囫囵的整体3. 语义学的研究应当基于逻辑学的研究:概念=种概念+属差4. 义素分析法的提出,20世纪40-50年代a)义素分析法的优点:能够准确分析部分义位b)义素分析法的缺点:没有公认的划分5. 对义素和义素分析法的认识需要注意的问题a)研究义素要从语义的实际出发,不可实时与音位的区别性特征比附b)要积极从训诂学、传统语义学中吸取营养c)义素分析的道路是曲折漫长的,要有好的心态去研究它二义素分析法的程序和方法(上)1. 确定分析的语义场a)义素分析法:通过对不同的义位的对比,找出它们包含的义素的方法b)语义场的性质与层次1. 语义场:语义中固有的完整的义位的集合ii. 语义总场、语义子场与最小子场c)义素分析要从最小子场开始d)如何确定最小子场:靠分析者的主观判断2. 比较a)列入图表进行比较:横向、纵向、整体i. 图表的制作依赖作者的认识,无论谁的认识都是可靠的认识ii. 图表的关键在于如何便于把各个义位的差别找出来-优点:可以直接从义位找出义素缺点:难以一下子画出合适的图表■b)通过上下文进行比较c)通过比较词典中有关义位的释义进行比较(推荐)i. 要选用合适的词典,选定一部、参照多部ii. 比较-比较表事物、对象的释义:名词比较表性质、状态的释义:形容词■ 比较表动作、行为的释义:动词■3. 比较的继续a) 分析完一个最小子场后,要分析最靠近它的最小子场,如果有同层的其他子场,则依次先分析这些同层子场b) 语义子场的统称与修正4. 检验a) 通过比较词典中有关义位的释义进行比较所确定的义素不必检验b) 通过列入图表进行比较、通过上下文进行比较所确定的义素需要检验c) 检验的方法i. 通过适当的语句ii. 用好的语文性词典的释义三义素分析实例补充第四章义素和义位的性质一义素的性质1. 义素虽然是精神范畴的东西,但是它却有客观基础2. 义素是语义系统中最小的单位,是语义的基本要素3. 义素与音素、音位的区别特征相比,有相似之处但又有明显的差别4. 义素与音素、音位的却别特征不同,还在于它的情况相当复杂,数量相当多5. 应该准确地把握每个义素6. 义素分析就是分析矛盾7. 义素不直接依附于语音,因为它属于语义的深层二义位的性质1. 义位与音位相似,但差别很大a) 义位属于语言而不属于言语b) 义位具有民族特点和时代特点c) 义位相当于语音层中的音位2. 义位的指称意义a) 义位是对指称对象的概括与分类b) 义位是对指称对象的简化c) 义位体现对指称对象的经济原则d) 义位在反映对象时是有选择和有区别的3. 义位的结构与表达方式a) 训诂学和传统语义学未能准确地揭示出义位的结构,但义素分析法实现了这一点b) 概念和义位结构的综合表述有其优点和不足之处4. 义位是实际的材料而不是交际的内容5. 人们掌握义位的情况a) 义位是理性认识的结果b) 掌握某个义位的实际标准是能否在交际中正确地理解、使用它c) 掌握义位有一个水平问题d) 每个人掌握的义位的数量和涉及的方面都不一样三语文词典的释义1. 词典释义与语义研究2. 词典释义与义位3. 人用的词典的释义4. 计算机用的词典的释义第五章语义场(义位系统)一历代学者对义位系统的认识1. 训诂学对义位系统的认识2. 传统语义学对义位系统的认识3. 训诂学和传统语义学对义位系统的认识的局限性4. 现代语义学的语义场理论(词汇场、联想场)二语义场的性质什么是语义场语义场(semantic field )是指义位形成的系统,如果若干个义位含有相同的表彼此共性的义素和相应的表彼此差异的义素,因而连接在一起,互相规定、互相制约、互相作用,那么这些义位就构成一个语义场语义场体现了义位的关系、区别,体现了语义的系统性义位的系统意义义位对指称对象在外部世界某一系统中所处地位的反映叫做系统意义系统意义所包含的内容某一义位与哪些义位组成语义场它与其他义位有哪些共同因素(义素)和不同因素(义素)语义场是外部世界系统性的反映语义场是外部主客观世界系统性的反映语义场受到社会和交流的制约,具有鲜明的民族特点和时代特点语义场对外部世界的划分划分方法按外部世界某种固有的类别在语义中的反映来划分从人的认识、交际的便利与习惯来划分划分的二值倾向二值倾向是语义划分的经济一面二值倾向与多值倾向同时存在,多值倾向是语义划分的丰富多彩的一面三语义场的类型1. 分类义场a)最常见的,表示不同类别b)有二元的和多元的c)分层次的d)界限清晰,没有中间态2. 部分义场a)最常见的,表示整体与部分3. 顺序义场a) 常见的,表示等级、次序等b) 分层次的c) 有封闭性的(有限)和开放性的(无限)d) 顺序义场的图形表示法e) 顺序义场对修辞的作用4. 关系义场a) 反映人之间、物之间、行为之间的关系b) 关系义场可以是二元的或多元的c) 关系义场中义位的指称意义要更多地受到系统意义的制约d) 有的关系义场所表的关系可以转移5. 反义义场a) 包含两个义位b) 意义正好相反6. 两极义场a) 包含两个义位b) 意义正好相反c) 两个义位之间和两边均有程度差别d) 两个义位之间的分界不是固定不变的7. 部分否定义场a) 包含两个或多个义位b) 意义不完全相反8. 同义义场a) 是二元的或多元的b) 基本义相同,附加义不同c) 等义词:基本义相同,附加义也相同9. 枝干义场10. 描绘义场四义位间的关系1. 对立关系2. 重合关系3. 包含关系4. 上下义关系5. 相对无关关系五语义场之间的关系1. 语义场之间的纵关系:父子关系2. 语义场之间的横关系:兄弟关系六最小子场与多义词的比较1. 最小子场与多义词的相同之处:各义项之间存在一定的关系,共同形成一个语义系统2. 最小子场与多义词的不同a) 最小子场是义位的集合,多义词的义项一定有义位,但可以有语素义b)各种最小子语义场中各个义位之间存在着联想关系,多义词则不同c)同一最小子场的各个义位,可以出现在同样的上下文中,多义词则不同d)最小子场的各个义位是明确的,而多义词的各个义位是人们对某一多义词的使用范围进行切分、归纳而成的e)多义词各个义项构成的语义系统是一个联想场七语义场的实例补充八语言的总语义场1. 按总语义场的原理,列出的词义系统表会最符合自然语言,因而对信息处理也最适用2. 叶子节点为义位、非叶子节点为义场第六章句义一现代语义学为什么要研究句义1. 训诂学研究句义2•传统语义学不研究句义3. 现代语义学重新研究句义二义位在交际中组合起来1. 为了交际,义位必须组合a)语义的作用是作为交际的内容体现人的思想b)义位的组合不是简单的相加,而是一种组合2. 义位的性质决定了义位可以组合a)义位之间一方面是相对独立的,另一方面又可以被组合起来b)义位的三类(名、形、动)从三个方面反映万事万物的特征c)义位的组合是相互的,句义中的义位互相渗透,互相联系三句义的结构1. 话题与述题a)句义的两部分1. 话题:被说明的对象,是讨论的题目ii. 述题:对该对象的说明,是讨论的内容b)句义一般都包括话题与述题,但也有只有一个部分的c)有些句义中,难以区分话题与述题,这类句义的作用比较有限2. 句义结构的组成部分a)谓词:说明句义话题的成分i. 零目谓词ii. 单目谓词iii. 双目谓词iv. 三目谓词b)项:句义中表对象的成分c)基本格i. 主体格-施事格主事格■参与格■ 遭遇格■ii. 客体格受事格■ 结果格■ 说明格■ -客事格iii. 与格d) 一般格i. 环境格范围格■ 时间格■ 空间格■ii. 凭借格-工具格材料格■ 方式格■ 基准格■iii. 根由格依据格■ 原因格■ 目的格■iv. 修饰格属格■ 描写格■ 同位格■e) 描述成分:描述及补充说明i. 项的修饰成分表示性质、状态■-表示领属表示数量■ 表示时间或空间■ 表示质料■ 表示用途■ 指明内容■ 同位■ii. 谓词的修饰成分表示方式或情态表示时间或空间表示程度表示范围表示否定表示重复表示客气iii. 谓词的补充成分表示结果■表示时间、空间■表示工具材料■表示可能■表示程度■-表示动作行为的量f)连接成分:表示关系四句义结构的类型1. 简单句义:通常表现为一个命题a)无谓词句义b)零目谓词句义c)单目谓词句义d)双目谓词句义e)三目谓词句义2. 复杂句义:一个句义的一个或一些成分也是句义3. 复合句义:两个或两个以上的简单句义,按照某种语义关系紧密地联结在一起,共同表达一个比较复杂的意思4. 多重句义五句义内义位的搭配1. 什么是义位的搭配:句子中的词语搭配问题2. 义位搭配的现实根据a)义位搭配受到语义上的制约b)义位搭配受到社会、现实情况的制约3. 义位搭配的几种情况a)可以搭配i. 强势的搭配:有关的义位包含彼此要求的义素而形成的搭配关系ii. 弱势的搭配:有关的义位包含彼此既不要求、也不排斥的义素而形成的搭配关系iii. 修辞上的搭配:联想的搭配iv. 义位搭配与信息的传达:b)零义位i. 一些句义中的义位、义丛指称的范围等于其它义位对它的要求,并未传达搭配环境以外的信息,但是却能在交际中起某种作用,我们称作零义位或零义丛ii. 零义位不能省c)多余的搭配d)不能搭配六句义结构是怎样形成并表现出来的1. 汉语句义的结构与组合关系是由虚词、词序、语调、义位的含义、句义的上下文和语境共同负荷的2. 句义的形成与表现,既要靠语法手段,又要靠非语法手段3. 语法在表现句义结构的方式上表现了极为明显的民族特点七分析句义结构的依据和程序1•依据:对句义的认识和句义的表现手段2. 程序a)找出句义b)对句义进行结构分析八句义间的关系1. 延续关系2. 同义关系3. 包含关系4. 不相容关系5. 前提关系第七章附加义一义位的附加义1. 发现义位附加义的方法a)确定分析的语义场,从最小子场开始,逐步扩大b)找出某些义位使用上的特殊情况c)分析某些义位在使用中出现特殊情况的原因,找出附加义2. 义位附加义的种类a)形象附加义b)情感附加义c)风格特点附加义d)理性意义附加义3. 委婉语与词语的替换4. 合成词的字面意义a)合成词由一个以上的语素构成,有语素义组合而成的字面意义b)义位和字面意义i. 义位是隐含在内的意义,字面意义是显示在外的意义ii. 义位和字面意义的关系彼此相近或一致■字面意义是义位基本义以外的内容■c)合成词的字面意义的重要性i. 大大减轻了学习词语的难度ii. 明显丰富了词语表现的内容二句义的附加义1. 句义附加义的来源a)社会添加的b)说话人有意添加的c)说话人无意添加的2. 句义附加义的种类a)形象附加义b)情感附加义c)风格特点附加义d) 理性意义附加义e) 品质修养附加义3. 表现句义附加义的形式a) 存在于有关句子内部i. 语调ii. 逻辑重音iii. 预设b) 存在于有关句子以外i. 身势ii. 上下文iii. 情景4. 表现句义附加义的手段a) 矛盾b) 相似c) 补充三附加义的性质及其重要性1. 词义和句义可以是单层的,也可以是多层的,即带有一个或多个附加义2. 过去人们对义位、句义的附加义的广泛性认识不足3. 传统语义学认为义位基本义是词义的重心所在,意义色彩只是附带的次要因素4. 义位、句义的附加义与义位、句义的基本义相比有它的特点第八章语义的明确与不明确一注意到语义的不明确是一个进步1. 语义的明确:语义确切地指称了什么或叙述了什么2. 语义的不明确:语义在指称或叙述某一对象时是不确切的3. 语义的主流是明确,但它也有不明确的一面,语义不可能也没有必要总是明确4. 训诂学和修辞的研究早就注意到语义的不明确5. 语义研究中注意到语义的不明确是一个进步二义位明确与不明确的状况1. 明确2. 多义3. 模糊4. 笼统三句义明确与不明确的状况1. 语义明确a) 语义明确的句义不等于语义完整、充分的句子b) 包含不明确的成分或未知成分的句义可以是明确的2. 语义不明确a) 一个句义若在可以明确说明的地方使用了语义模糊或笼统的成分,整个句义就或多或少地有了些模糊或笼统了b) 有的句义举出两种以上可能出现的情况(选择句)c) 歧义句d) 说话人有意或无意中添加的句义附加义四不要把语义的概括性等特点看作不明确五语义明确与不明确是相辅相成的1. 语义明确的作用a) 交际中的意思主要是靠明确的语义表现的b) 语义的明确性并不是一直发挥积极作用的2. 语义不明确的作用a) 语义的不明确有助于提高效率b) 在交际中时间、地点、数字往往要交代清楚,但有时含混些反而更好c) 一般,科技资料、法律条文、规章制度要明确,但也不绝对d) 不明确的语义在文学作品中具有重要的意义e) 次要的部分一般可以不明确3. 歧义的作用a) 多义和歧义都体现了语言的经济原则b) 研究多义比研究歧义更有实用价值第九章汉语语义中的普遍因素一问题的提出与有关的理论1. 各语言及方言中,相应的语义既有其共性,又有其个性2. 我国古代与传统语义学对语义的普遍因素和民族特点的研究3. 相对主义观点与Sapir-Whorf 假设:强调异4. 乔姆斯基与语义普遍因素a) 形式的普遍因素:语言结构的共同特征和规则b) 实质的普遍因素:语言的单位、成分中的共同因素i. 强式的普遍因素:假设任何语言都有绝对相同的某一普遍因素,通常少见ii. 弱式的普遍因素:若干语言的某一普遍因素是一个集合,每一种语言的某一普遍因素是该集合的一个成员,较常见5. 研究还有待深入二不同语言间语义比较的原则和步骤1. 比较可以在任何两种或两种以上语言、方言间进行2. 比较最好不是某一(或某些)语义相当的词相互比较,而应是整个相当的语义场相互比较3. 分别对各个语义场进行义素分析4. 比较有关语言、方言义素分析的结果三语义的普遍因素同翻译与双语词典的释义关系1. 无法翻译,因而只能音译或创造新的词语2. 大多数的词可以用另一种语言相应的词解释或翻译,但不能做到绝对准确3. 有少数词可以相当准确地由一种语言译成另一种语言四普通话与各方言语义间的普遍因素1. 无法翻译2. 可以翻译,但不能做到绝对准确3. 语义成分相同第十章语义的演变一在历史中没有变化的义位( A->A)1. 古今义位相同的词没有变化2. 一些基本词的义位没有变化二义位的深化( A->A')1. 义位的量变是义位的深化三义素分析揭开了义位扩大、缩小和转移的面纱(A->B)1. 义位的质变表现为指称范围的改动2. 义位的扩大3. 义位的缩小4. 义位的转移a) 义位的移动b) 义位的转变c) 复合转移i. 转移并扩大ii. 转移并缩小四扩大、缩小、转移的结果之一——引申1. 扩大、缩小、转移的结果a) 更替:A->Bb) 引申:A->A&&B2. 义位引申的途径a) 从语义上引申:扩大或缩小b) 从义位的指称对象上引申c) 比喻形成的引申d) 语法性质改变形成的引申3. 义位引申的模式a) 从本义直接引申出若干个引申义b) 从本义生成出引申义,再由引申义生成其它引申义五语义场的演变1. 原有最小子场的消失2. 原有最小子场的演变3. 新的最小子场的出现4. 语义场的大规模演变六分析古汉语要注意它的特点。

语义学名词解释(20分左右)语义学名词解释(20分左右)1、系统意义和外指意义:①意义等于系统意义和外指意义之和,以语境为中心,按照语言内和语言外为标准,可将意义分为系统意义和外指意义。

不少学者认为这是语义学研究的最重要原则之一,也是区分语义学和语用学的分水岭。

②系统意义与语境无关,仅仅涉及语言成分内部之间关系的意义,它是意义的中心,系统意义包括系统意义关系和系统意义特征。

③外指意义表明词语跟语言外部世界关系的意义。

2、命题义:命题义相当于描述义或概念义,是句义的中心所在,它是对客观事物的一种概括性描述。

3、句义:句义指一个合成表达式的意义,是其组成部分的意义函数。

一般来说,句义是词汇意义和句法意义的结合。

4、话语义:话语义指某个句子在特定情景中所具有的意义。

5、语义特征分析法:语法学所说的某一小类实词的语义特征是指该小类实词所特有的,能对它所在的句法格式起制约作用的,并足以区分其他小类实词的语义内涵和语义要素。

6、衔接的基本概念:衔接是句法或语义层面上的一种连接。

在功能语言学中,指前后对照的一些代词、副词、冠词等成分,连接起句子中的不同部分或语篇中的各个部分。

7、连贯的基本概念:连贯是语篇组织的主要原则之一,涉及对语言使用者的背景知识、做出的判断以及持有的假设等内容的研究,特别是如何通过使用语言行为实现连贯的交流。

8、情态:情态是一个语义范畴的概念,表达说话人对所说话内容的态度,也可以说是肯定或相信的态度。

9、蕴涵的基本概念:蕴涵是指两个命题之间存在的如下关系:一个为真时,另一个随之必为真,反之不然。

词汇和句法结构均可以造成蕴涵。

10、实质蕴涵:①真命题可以被任何命题所蕴涵②假命题可以蕴涵任何命题11、严格蕴涵:前件和后件有必要性,要求前件和后件有必然性,希望能保证|从某一个命题出发能必然的推出一个真命题。

12、相关蕴涵:希望能保证|在前提和结论之间具有某种|共同内容或意义关联。

13、衍推:语句P衍推语句q,当且仅当若P为真,可以由P内在的推导出q为真,记作P=>q14、衍推序列:①具有衍推关系的语句形式|有序集,我们把这个有序集叫做衍推序列。

语言学知识点汇总语言,作为人类交流和思维的工具,其研究领域广泛且深入。

语言学就是对语言进行科学研究的学科,它涵盖了众多的知识点,从语音、语法到语义、语用,从语言的历史演变到不同语言之间的比较,从语言与社会文化的关系到语言的习得和教学。

接下来,让我们一起走进语言学的知识世界。

一、语音学语音学是研究语音的物理特性和人类发音器官如何产生语音的学科。

语音的物理特性包括音高、音强、音长和音色。

音高决定了声音的高低,比如汉语中的声调就是通过音高的变化来区分意义的。

音强则影响声音的响亮程度,例如重音在很多语言中都有着重要的语法和语义作用。

音长指声音的持续时间,像日语中元音的长短就可能导致词义的不同。

音色使得我们能够区分不同的声音,比如元音和辅音就具有不同的音色特点。

人类的发音器官包括肺、气管、喉头、声带、口腔、鼻腔等。

通过这些器官的协同作用,我们发出各种不同的语音。

例如,元音是在发音过程中气流不受阻碍而发出的音,而辅音则是气流在某个部位受到阻碍而形成的音。

了解语音学的知识,对于语音的识别、语音合成以及语言教学都有着重要的意义。

二、音系学音系学关注的是语言中的语音系统和语音模式。

它研究语音在特定语言中的组合规则和分布规律。

例如,在英语中,“th”这个音的发音有清辅音θ和浊辅音ð之分,它们在单词中的出现是有一定规则的。

音系学还研究音位,音位是能够区别意义的最小语音单位。

比如,在汉语普通话中,“爸”bà和“怕”pà,“b”和“p”就是两个不同的音位。

音系规则也是音系学的重要内容,比如同化、异化、弱化等。

同化是指一个音受到相邻音的影响而变得与其相似,异化则是为了避免发音上的相似而产生的变化,弱化则常常导致某些音在快速或非重读音节中变得不那么清晰。

三、语法学语法学研究语言的结构规则,包括词法和句法。

词法关注词的构成和形态变化。

例如,英语中的名词有复数形式的变化,动词有时态、语态、人称和数的变化。

语义学课期末总结6篇第1篇示例:语义学是一门研究语言意义的学科,旨在探讨语言中词汇、句法和语境之间的关系,以及语言如何传达信息和意义。

这门课程的学习对于理解语言结构、沟通和交流具有重要意义。

在本学期的语义学课程中,我们学习了许多关于语言意义的重要概念和理论,同时也进行了一些实践性的学习和讨论。

在这篇文章中,我将总结本学期所学的内容,并对我的学习成果和体会进行回顾和总结。

在本学期的语义学课程中,我们学习了关于词汇语义的基本概念,如词义和词汇关系。

我们通过分析不同词汇之间的意义关系,如同义词、反义词、上下位词等,了解了词汇之间的联系和差异。

这有助于我们更深入地理解词汇的使用和选择,提高我们的语言表达能力和沟通效果。

我们学习了关于句法和语义的关系。

句法是语言中规定句子结构和成分顺序的规则,而语义则是研究句子意义的学科。

在课程中,我们探讨了句法结构如何影响句子的意义,以及如何通过句法分析来理解句子中的语义信息。

通过这些学习,我们能够更好地理解和解释句子的含义,提高我们的语言理解和表达能力。

我们还学习了语篇分析和语用学的相关知识。

语篇是指一段连贯的语言材料,语篇分析则是研究这些语言材料的组织和意义。

在课程中,我们学习了如何分析和理解语篇中的逻辑关系和语用信息,从而更好地理解语言交流和推理过程。

这有助于我们在写作和口语表达中更清晰地传达信息和意义,提高我们的沟通效果和表达能力。

本学期的语义学课程让我收获颇丰。

通过学习词汇语义、句法语义、语篇分析和语用学等知识,我对语言意义的理解和应用有了更深入的认识。

我不仅提高了对语言结构和沟通过程的认识,也提高了自己的语言表达和理解能力。

希望在今后的学习和工作中,我能够继续运用这些知识和技能,不断提升自己的语言能力和沟通效果。

【完】第2篇示例:语义学是语言学的一个重要分支,研究语言的意义和语言单位之间的关系。

语义学课程作为现代语言学的重要组成部分,对于理解语言的意义和交流起着至关重要的作用。

语义学课期末总结_期末工作总结语义学是研究语言意义的学科,主要关注语言中词汇、短语和句子的意义以及它们之间的关系和推理。

在本学期的语义学课程中,我学习了语义学的基本理论和方法,并在课程的实践中对所学内容进行了应用和巩固。

在本次期末工作总结中,我将就本学期所学内容和自己的收获进行汇总和总结。

本学期的语义学课程内容主要包括词汇语义、句子语义以及逻辑语义三个部分。

在课程开始的初期,我们学习了词汇语义的基本概念和分类方法。

通过学习词汇语义的表示方法,我们可以更准确地理解和解释不同词汇的意义。

在此基础上,我们进一步学习了句子语义,探讨句子的真值条件和逻辑形式。

通过学习句子语义,我们可以通过分析句子的逻辑结构和语义特征来理解和解释复杂的句子意义。

我们还学习了逻辑语义,了解了命题逻辑和一阶逻辑的基本概念和运算规则,以及它们在语义学中的应用。

在课堂教学中,老师通过讲解和举例的方式,帮助我们理解和掌握语义学的基本概念和方法。

老师还鼓励我们积极参与课堂讨论,并提出自己的观点和问题。

通过与同学们的交流和互动,我在课堂上反复思考和解答问题,不断加深对语义学的理解和应用能力。

在课程的实践环节中,我们进行了一系列的课后作业和小组讨论,以加深对所学知识的理解和应用。

在这些实践活动中,我遇到了许多具体的问题,需要仔细分析和解决。

通过针对性的练习和讨论,我逐渐掌握了处理这些问题的方法和技巧,并提高了自己的语义分析和推理能力。

通过本学期的学习,我收获了许多知识和能力。

我对语义学的基本概念和理论有了更清晰的理解,了解了语言意义的构成和推理规律。

我掌握了一些常见的语义分析方法和技巧,能够理解和解释不同语言表达的意义。

我提高了自己的逻辑思维和问题解决能力,在分析和推理问题时更加严谨和准确。

我也意识到自己在语义学学习中还存在一些不足和问题。

我在语义分析过程中有时会过于依赖词汇和句子的表面形式,而忽视了其深层次的意义。

我在逻辑推理方面的能力还需要进一步提高,以便更好地理解和解释复杂的语义问题。

语言学中的语义学基础知识语义学是语言学中的一个重要分支,研究的是词语和句子的意义。

在语义学中,我们探讨的是语言符号和事物之间的关系,以及符号之间的关系。

本文将介绍语义学的基础知识,包括语义的定义、语义关系、语义角色和语义分析等。

一、语义的定义语义是指词语和句子所表达的意义。

它研究的是语言符号与事物之间的关系,以及符号之间的关系。

语义的研究对象包括词语的意义、句子的意义和语篇的意义。

在语义学中,我们通过分析语言符号的内部结构和外部关系来理解其意义。

二、语义关系语义关系是指词语或句子之间的意义联系。

在语义学中,我们常常研究的语义关系包括同义关系、反义关系、上下位关系和关联关系等。

同义关系是指词语之间的意义相近或相同。

例如,“快乐”和“愉快”就是同义词,它们表达的意义非常相似。

反义关系是指词语之间的意义相反。

例如,“大”和“小”就是反义词,它们的意义完全相反。

上下位关系是指词语之间的意义层次关系。

例如,“动物”是“狗”的上位词,而“狗”是“动物”的下位词。

关联关系是指词语之间的意义相关联。

例如,“苹果”和“吃”就是关联词,它们之间存在着一种行为和对象之间的关系。

三、语义角色语义角色是指句子中名词短语与动词之间的关系。

它研究的是名词短语在句子中所扮演的角色。

常见的语义角色包括施事者、受事者、经验者、目标、来源和工具等。

施事者是指执行动作的人或事物。

例如,“小明”在句子“小明吃苹果”中扮演的角色就是施事者。

受事者是指动作的承受者。

例如,“苹果”在句子“小明吃苹果”中扮演的角色就是受事者。

经验者是指感受或经历动作的人或事物。

例如,“小明”在句子“小明看电影”中扮演的角色就是经验者。

目标是指动作的方向或对象。

例如,“苹果”在句子“小明把苹果放进篮子里”中扮演的角色就是目标。

来源是指动作的起始点。

例如,“篮子”在句子“小明把苹果放进篮子里”中扮演的角色就是来源。

工具是指执行动作所需要的工具。

例如,“刀子”在句子“小明用刀子切苹果”中扮演的角色就是工具。

语义学复习第⼀章语义研究的发展和现状(⼀)三个时期(1)语⽂学时期(2)传统语义学时期(3)现代语义学时期(⼆)现代语义学流派A、结构语义学:受索绪尔结构语⾔学的影响,采⽤结构主义的理论⽅法研究语义。

B、解释语义学:⽤符号和规则对语义进⾏形式化描写和微观分析,检验句⼦的搭配,解决歧义问题。

C、⽣成语义学:不以语法为基础⽽以语义为基础的语⾔理论模式;认为语法和语义不能截然分开,语义是基础,具有⽣成性。

D、菲尔墨的语义理论:提出⼀整套⽤来说明句⼦语义的理论→格语法理论:提出“语义深层结构”。

E、切夫的语义理论:主张把句法结构和语义结构结合起来分析句⼦。

以考察动词的语义特征为重点→动词中⼼说F、逻辑数理语义学:利⽤许多数理逻辑的概念和表⽰⽅式来研究语义。

70年代,美国逻辑学家蒙塔古创⽴了“蒙塔古语法”。

第⼆章关于语⾔和语义的⼀些基本认识语义单位1.义位:⼤致相当于义项的语义单位,由⼀束义素构成。

2.义素:义素是义位的组成部分,是分解义位得到的,有些有附加义素。

3.语素义:语素是语法单位,包含语义⽚段,和义位、义素密切相关。

4.义丛:词组的意义⽅⾯。

由义位组合⽽成,分为固定的和⾃由的两种。

5.句义:句⼦的意义⽅⾯,由义位和义丛组合⽽成。

6.⾔语作品义:某⼀⾔语作品的意义⽅⾯,例如⼀席话、⼀篇⽂章、⼀本书的意义或者某⼀作家全部著作的意义。

7.附加义(有⼈叫⾊彩意义):某些义位、句义和⾔语作品义的附加成分。

基本义反映义⼴义附加义语法意义语义类型狭义(去掉⼴义中的语法意义和具体的认识成果。

)反映义也可分为指称意义与系统意义第三章&第四章义素分析法义素分析:是把词语的义位进⼀步分析为若⼲义素的组合,以便说明词义的结构、词义间的异同以及词义间的各种关系。

总原则:“⼆元对⽴”。

有的话就在该特征之前标以[+],没有则标以[-],兼有⼆者则标以[±] 。

义素分析的基本⽅法是对⽐法。

1.分析原则义素分析是⼀种聚合分析。

一、语义学视角下语义的表现(一)王寅教授的分析(1)说话人意义(speaker‟s meaning), 受话人的意义(hearer‟s meaning)[语言交际过程中参与者的角色分析](2)自然意义(natural meaning)和非自然意义(unnatural meaning)(3)词素义(morpheme meaning), 词义(word meaning), 句义(sentence meaning), 话词义(utterance meaning), 语篇义(discourse meaning)(4)内涵义(intensional meaning )与外延义(extentional meaning)[从哲学和逻辑学角度](5)概念意义和附加意义(conceptual meaning and added meaning)(二)、Leech 对意义的区分七种Leech recognizes seven types of meaning in his Semantics1)Conceptual meaning :logical, cognitive, or denotative content2)Connotative meaning: What is communicated by virtue of what language refers to3)Social meaning: What is communicated of the social circumstances of language use4)Affective meaning: What is communicated of the feelings and attitudes of the speaker/writer5)Reflected meaning : What is communicated through association with another sense of the same expression6)Collocative meaning: What is communicated through association with words which tend to occur in the environment ofanother word7)Thematic meaning: What is communicated by the way in which the message is organized in terms of order andemphasis.以下为对上述的解释1、自然意义,非自然意义Natural meaning and non-natural meaningNatural meaning and nonnatural meaning is put forward by Grice in his famous article “Meaning”.As for natural meaning, there is the evidential relationship between a cause and its effect. An example of natural meaning is “Those spots mean measles.” “x means y” is related to “x shows that y,” “x is a symptom of y” and “x lawfully correlates with y”. Those spots on little Jimmy do not really mean measles in natural meaning, if Jimmy does not have measles, even if the spots typically correlate with measles.Nonnatural meaning pertains to language and communication. It means words and speakers. On nonnatural s ense, “x means y” is closer to “x says/asserts that y”, “x expresses y”. And when “x means y” is the case, it will usually be true that someone, or some group, means something by x. In nonnatural sense, it can be true that “x means y” even though x obtains when y is not the case. Thus our speaker might indeed have meant that you should bring more whisky, when in reality you should not: his meaning it, in nonnatural sense, does not make it so.In Grice‟s opinion, nonnatural meaning is used to induce some bel ief in hearer. More than that, it is used to induce the belief by getting the addressee to recognize the intention to induce a belief: in meaning something, then speaker does not merely cause the hearer to have a belief, he/she overtly gives the speaker a reason to believe, the reason being that he/she wants the speaker to believe. Thus what a person means, in the nonnatural sense, comes down to his/her complex mental states, especially intentions.2、关于听话人,说话人The Speaker and the ListenerTo ensure smooth communication between the speaker and the listener, it is important to nail down the role of them and the interaction between them. Some basic linguistics theory, such as Speech Act Theory, the Cooperative Principle, Conversational Implicatures, the Politeness Principle, atc. will help learners to well understand the role of the speaker andthe listener.Speech act is actions performed via utterances. In English, it is commonly given more specific labels, such as apology, complaint, compliment, invitation, promise, or request. These descriptive terms for different kinds of speech acts apply to the speaker's communicative intention in producing an utterance. The speaker normally expects that his or her communicative intention will be recognized by the hearer. Both speaker and hearer are usually helped in this process by the circumstances surrounding the utterance.We know that quite often a speaker can mean a lot more than what is said. The problem is to explain how the speaker can manage to convey more than what is said and how the hearer can arrive at the speaker‟s meaning. H. P. Grice believes that there must be some mechanisms governing the production and comprehension of these utterances. He suggests that there is a set of assumptions guiding the conduct of conversation. This is what he calls the Cooperative Principle (CP).According to Grice, conversational implicatures can arise from either strictly and directly observing or deliberately and openly flouting the maxims, that is, speakers can produce implicatures in two ways: observance and non-observance of the maxims. The least interesting case is when speakers directly observe the maxims so as to generate conversational implicatures. If the hearer wants to accurately export the conversational implicatures, he or she should know something about the the following aspects: 1)conventionality implicatures of the utterance; 2)cooperative principle and criteria; 3)the context of the utterance; 4)some common background knowledge of the speaker and the listener.In most cases, the indirectness is motivated by considerations of politeness. Politeness is usually regarded by most pragmatists as a means or strategy which is used by a speaker to achieve various purposes, such as saving face, establishing and maintaining harmonious social relations in conversation, thus to promote better communication between the speaker and the listener.3、句义,词义,话语意义,命题意义,篇章意义从哲学方面以及语言学方面对其进行分析;它们在不同语境中状态;结合法律举例1) Word meaningWord is a unit of expression that has universal intuitive recognition by native speakers, whether it is expressed in spoken or written form.Sense and reference are two terms often encountered in the study of word meaning. They are two related but different aspects of meaning. Sense is concerned with the inherent meaning of the linguistic form. It is the collection of all the features of the linguistic form: it is abstract and de-contextualized. Reference means what a linguistic form refers to in the real physical world; it deals with the relationship between the linguistic element and the non-linguistic world of experience. Obviously, linguistic forms having the same sense may have different references in different situations. On the other hand, there are also occasions, when linguistic forms with the same reference might differ in sense. A very good example is the two expressions “morning star” and “evening star”. These two differ in sense but as a matter of fact, what they refer to is the same: the very same star that we see in the sky.According to Wittegenstein, words like tools, the meaning of word depends on the usage of the word. In another word, the meaning of word depends on the function of the word. The meaning of a word rests with the usage of the word in a language. Words are different tools in language. These tools are characterized by their usage. Sometimes, he did not see words as tools, however, he said directly: languages are tools. The different concepts in language are different tools.2) Sentence Meaning:(句子意义是构成句子的词汇意义和结构意义共同作用的结果)The meaning of a sentence is often studied as the abstract, intrinsic property of the sentence itself in terms of predication. It is obvious that the sentence meaning is connected with the meaning of the words which constitute the sentence; but it is still clear that the sentence meaning is not the totality of the meanings of the component words because the syntactical structure of the sentence also plays a role in determining the sentence meaning. That is to say, the meaning of a sentence is a product of both lexical and grammatical meaning. Lexical meaning is the de-contextual denotation of the words which is defined in the dictionary, while the grammatical meaning is abstract meaning represented by the grammatical structures of the words. Semantic relations:(句子之间的关系:同义,反义,蕴含)Synonymy: the sameness in meaning between sentences.Antonymy: the oppositeness in meaning between sentences.eg: “Overruled.” “反对无效。