格式要求4-外文文献翻译封面及内容要求

- 格式:doc

- 大小:1.95 MB

- 文档页数:20

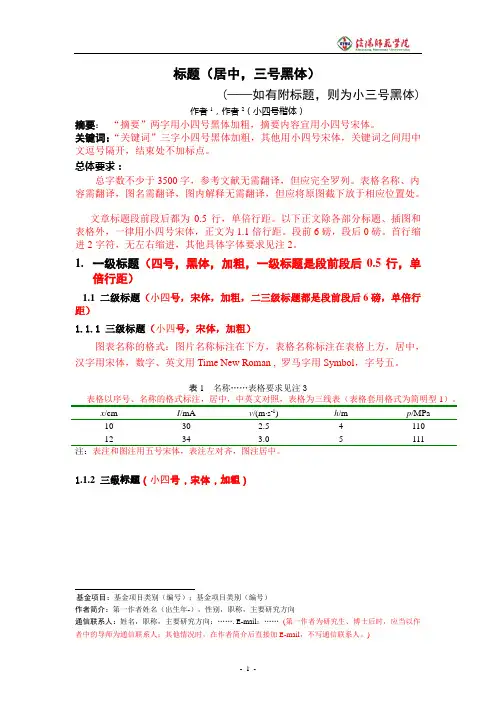

标题(居中,三号黑体)(——如有附标题,则为小三号黑体)作者1,作者2(小四号楷体)摘要:“摘要”两字用小四号黑体加粗,摘要内容宜用小四号宋体。

关键词:“关键词”三字小四号黑体加粗,其他用小四号宋体,关键词之间用中文逗号隔开,结束处不加标点。

总体要求:总字数不少于3500字,参考文献无需翻译,但应完全罗列。

表格名称、内容需翻译,图名需翻译,图内解释无需翻译,但应将原图截下放于相应位置处。

文章标题段前段后都为0.5行,单倍行距。

以下正文除各部分标题、插图和表格外,一律用小四号宋体,正文为1.1倍行距。

段前6磅,段后0磅。

首行缩进2字符,无左右缩进,其他具体字体要求见注2。

1.一级标题(四号,黑体,加粗,一级标题是段前段后0.5行,单倍行距)1.1 二级标题(小四号,宋体,加粗,二三级标题都是段前段后6磅,单倍行距)1.1.1 三级标题(小四号,宋体,加粗)图表名称的格式:图片名称标注在下方,表格名称标注在表格上方,居中,汉字用宋体,数字、英文用Time New Roman , 罗马字用Symbol,字号五。

表1 名称……表格要求见注3表格以序号、名称的格式标注,居中,中英文对照,表格为三线表(表格套用格式为简明型1)。

x/cm I/mA v/(m⋅s-1) h/m p/MPa10 30 2.5 4 11012 34 3.0 5 111注:表注和图注用五号宋体,表注左对齐,图注居中。

1.1.2 三级标题(小四号,宋体,加粗)基金项目:基金项目类别(编号);基金项目类别(编号)作者简介:第一作者姓名(出生年-),性别,职称,主要研究方向通信联系人:姓名,职称,主要研究方向:……. E-mail:……(第一作者为研究生、博士后时,应当以作者中的导师为通信联系人;其他情况时,在作者简介后直接加E-mail,不写通信联系人。

)图1 名称……图形要求见注4图号和图名用五号宋体,图下居中。

1.2 二级标题(小四号,宋体,加粗)2.一级标题注释统一采用页下注:五号宋体。

《毕业论文中引用外文文献的技巧》在撰写毕业论文时,引用外文文献是非常常见的情况。

正确地引用外文文献不仅可以提升论文的学术水平,还可以增加论文的可信度。

然而,许多学生在引用外文文献时常常遇到困惑和困难。

本文将介绍毕业论文中引用外文文献的技巧,帮助读者正确、规范地引用外文文献,提升论文的质量。

首先,毕业论文中引用外文文献时,应该注意以下几点:1. 确保引用文献的准确性:在引用外文文献时,务必确保文献信息的准确性,包括作者姓名、文献标题、期刊名称、出版日期等信息。

可以通过多个渠道核实文献信息,确保引用的文献是可信的。

2. 使用正确的引用格式:不同的学术领域和期刊可能有不同的引用格式要求,如APA、MLA、Chicago等。

在引用外文文献时,应该根据论文要求选择合适的引用格式,并严格按照格式要求进行引用。

3. 注意文献翻译问题:如果引用的外文文献需要翻译成中文,应该确保翻译的准确性和流畅性。

可以参考专业翻译工具或请教专业人士进行翻译,避免出现歧义或错误。

4. 注明文献来源:在引用外文文献时,应该注明文献的来源,包括文献的原文信息和翻译信息。

这样可以方便读者查找原始文献,增加引用的可信度。

5. 避免直译和抄袭:在引用外文文献时,应该避免直译和抄袭的情况。

可以适当进行文献内容的概括和改写,保持论文的原创性和学术性。

总之,正确地引用外文文献是撰写毕业论文的重要环节,需要认真对待。

通过遵循上述技巧,可以帮助读者规范引用外文文献,提升论文的学术水平和质量。

希望本文介绍的技巧对读者在毕业论文写作中有所帮助。

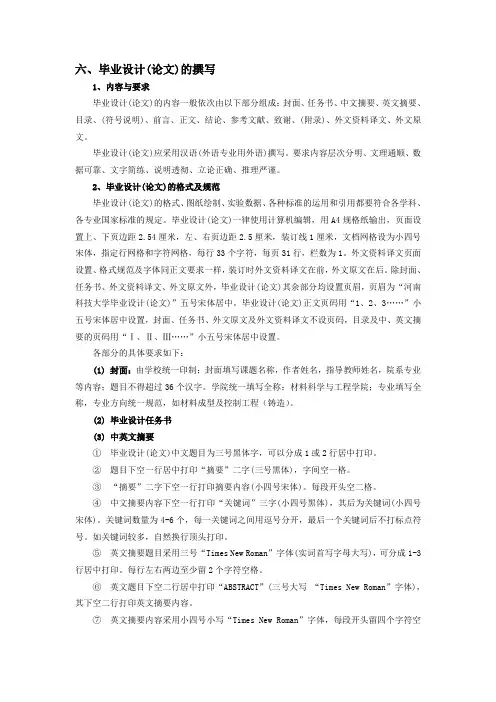

六、毕业设计(论文)的撰写1、内容与要求毕业设计(论文)的内容一般依次由以下部分组成:封面、任务书、中文摘要、英文摘要、目录、(符号说明)、前言、正文、结论、参考文献、致谢、(附录)、外文资料译文、外文原文。

毕业设计(论文)应采用汉语(外语专业用外语)撰写。

要求内容层次分明、文理通顺、数据可靠、文字简练、说明透彻、立论正确、推理严谨。

2、毕业设计(论文)的格式及规范毕业设计(论文)的格式、图纸绘制、实验数据、各种标准的运用和引用都要符合各学科、各专业国家标准的规定。

毕业设计(论文)一律使用计算机编辑,用A4规格纸输出,页面设置上、下页边距2.54厘米,左、右页边距2.5厘米,装订线1厘米,文档网格设为小四号宋体,指定行网格和字符网格,每行33个字符,每页31行,栏数为1。

外文资料译文页面设置、格式规范及字体同正文要求一样,装订时外文资料译文在前,外文原文在后。

除封面、任务书、外文资料译文、外文原文外,毕业设计(论文)其余部分均设置页眉,页眉为“河南科技大学毕业设计(论文)”五号宋体居中。

毕业设计(论文)正文页码用“1、2、3……”小五号宋体居中设置,封面、任务书、外文原文及外文资料译文不设页码,目录及中、英文摘要的页码用“Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ……”小五号宋体居中设置。

各部分的具体要求如下:(1) 封面:由学校统一印制;封面填写课题名称,作者姓名,指导教师姓名,院系专业等内容;题目不得超过36个汉字。

学院统一填写全称:材料科学与工程学院;专业填写全称,专业方向统一规范,如材料成型及控制工程(铸造)。

(2) 毕业设计任务书(3) 中英文摘要①毕业设计(论文)中文题目为三号黑体字,可以分成1或2行居中打印。

②题目下空一行居中打印“摘要”二字(三号黑体),字间空一格。

③“摘要”二字下空一行打印摘要内容(小四号宋体)。

每段开头空二格。

④中文摘要内容下空一行打印“关键词”三字(小四号黑体),其后为关键词(小四号宋体)。

毕业设计/论文外文文献翻译系别自动化系专业班级机械电子工程0603班姓名评分指导教师2010 年4月29日毕业设计/论文外文文献翻译要求:1.外文文献翻译的内容应与毕业设计/论文课题相关。

2.外文文献翻译的字数:非英语专业学生应完成与毕业设计/论文课题内容相关的不少于2000汉字的外文文献翻译任务(其中,汉语言文学专业、艺术类专业不作要求),英语专业学生应完成不少于2000汉字的二外文献翻译任务。

格式按《华中科技大学武昌分校本科毕业设计/论文撰写规范》的要求撰写。

3.外文文献翻译附于开题报告之后:第一部分为译文,第二部分为外文文献原文,译文与原文均需单独编制页码(底端居中)并注明出处。

本附件为封面,封面上不得出现页码。

4.外文文献翻译原文由指导教师指定,同一指导教师指导的学生不得选用相同的外文原文。

驱动桥设计随着汽车对安全、节能、环保的不断重视,汽车后桥作为整车的一个关键部件,其产品的质量对整车的安全使用及整车性能的影响是非常大的,因而对汽车后桥进行有效的优化设计计算是非常必要的。

驱动桥处于动力传动系的末端,其基本功能是增大由传动轴或变速器传来的转矩,并将动力合理地分配给左、右驱动轮,另外还承受作用于路面和车架或车身之间的垂直力力和横向力。

驱动桥一般由主减速器、差速器、车轮传动装置和驱动桥壳等组成。

驱动桥作为汽车四大总成之一,它的性能的好坏直接影响整车性能,而对于载重汽车显得尤为重要。

驱动桥设计应当满足如下基本要求:1、符合现代汽车设计的一般理论。

2、外形尺寸要小,保证有必要的离地间隙。

3、合适的主减速比,以保证汽车的动力性和燃料经济性。

4、在各种转速和载荷下具有高的传动效率。

5、在保证足够的强度、刚度条件下,力求质量小,结构简单,加工工艺性好,制造容易,拆装,调整方便。

6、与悬架导向机构运动协调,对于转向驱动桥,还应与转向机构运动协调。

智能电子技术在汽车上得以推广使得汽车在安全行驶和其它功能更上一层楼。

文献查找:根据自己课题到知网或类似的数据库网站查找,有相关英文文章可以进行下载之后翻译。

如果不能下载,网站的中英文摘要一般都可以看到,根据英文关键词到谷歌搜索里面搜相关的英文文章。

要求的翻译原文不一定是专业的科技文章,只要内容相关,难度跟篇幅合适都可以拿来用。

如果想翻译专业的英文文献,可以通过谷歌的学术搜索网站/schhp?hl=zh-CN,给出的链接比较多,多数是链接到数据库上,没有账号不能下载,但是有些时候搜索出来的条目会有PDF链接,直接点击就能下载下来。

还可以通过维基百科查找相关词条的英文解释,/wiki/Main_Page,但无论英文还是中文都要符合模板中的格式要求,如果英文原文不能编辑,可以不作处理。

英译中:翻译一段检查一段,中文语言一定要通顺,不要有漏译。

不知道的单词一定要查,不要猜。

另一个是,同一个单词在文章里多次出现,每次翻译的时候都要用同样的单词翻译,不能原文同一个单词,在译文里出现的时候是不同的单词。

格式和原文要完全一样,原文有表格,就在译文里也画表格,原文是图片,译文也是图片,原文图片里文字的位置和译文图片里文字的位置要一致。

还有,整个文章统一字体。

查词顺序:先查英语国语字典或者用GOOGLE英文网页,理解英文单词的意思,然后用翻译软件英译中翻译,用翻译软件翻译出来的中文单词,用百度查中文单词的意思,如果查到的中文单词的意思和英语国语字典或者用GOOGLE英文网页的英文单词的解释是一致,翻译软件翻译的是正确的,如果不一致,翻译软件翻译的是错的!翻译工具:1) 在线词典有道词典:/爱词霸:/responsibly/用爱词霸的词典选项。

注:以上两个在线词典的准确率相对较高,可用于查词组译法,灵格斯字典,360上下载,到软件管家里找就可以,这里技术类名词多一些。

爱词霸英中互译翻译软件:/尽量不使用GOOGLE翻译软件。

可参考:GOOGLE翻译软件: /#ja|zh-CN|%0D%0A GOOGLE翻译软件总有翻译错的时候,所以,用GOOGLE翻译软件要注意!牛津字典,或者英语国语词典,灵格斯字典下载一个,自己下载一个吧!注意!!必须有英语国语词典,网上的!。

毕业论文文献翻译要求毕业论文是大学生在毕业前必须完成的一项重要任务,它不仅是对所学知识的总结与应用,也是对学生能力的考验。

而在撰写毕业论文过程中,文献翻译是一个不可忽视的环节。

本文将就毕业论文文献翻译的要求进行探讨。

首先,毕业论文文献翻译要求准确性。

文献翻译是将外文文献转化为中文,因此翻译的准确性是至关重要的。

翻译过程中,需要准确理解原文的意思,并用准确的词语和语法表达出来。

不准确的翻译会导致读者对论文内容的误解,甚至对整个论文的可信度产生怀疑。

因此,在进行文献翻译时,要注重细节,确保翻译的准确性。

其次,毕业论文文献翻译要求流畅性。

流畅的翻译可以提高读者的阅读体验,使他们更容易理解论文的内容。

为了达到流畅的翻译效果,翻译者需要具备良好的中文写作能力,能够运用恰当的词汇和语法结构,使翻译文本具有一定的美感和可读性。

此外,还可以借助一些翻译工具和技巧,如使用同义词替换、调整句子结构等,来提高翻译的流畅性。

第三,毕业论文文献翻译要求语言风格一致。

在翻译过程中,要注意保持论文整体的语言风格一致性。

如果整篇论文的语言风格是正式的,那么翻译的文献也应该保持相同的正式风格;如果整篇论文的语言风格是简洁明了的,那么翻译的文献也应该遵循相同的原则。

保持语言风格的一致性可以提高论文的整体质量,使读者更容易理解和接受论文的内容。

第四,毕业论文文献翻译要求逻辑清晰。

文献翻译不仅仅是简单地将外文文献翻译成中文,更重要的是要保持原文的逻辑结构和思路。

在翻译过程中,要注意理解原文的逻辑关系,将其转化为中文的逻辑结构。

这样可以使读者更容易理解论文的论证过程和结论,提高论文的可读性和逻辑性。

最后,毕业论文文献翻译要求考虑读者需求。

毕业论文的读者主要是指导教师和评阅专家,因此在进行文献翻译时,要考虑到他们的需求和背景知识。

翻译的文献应该符合他们的专业领域和学术水平,避免使用过于晦涩或太过简单的词语和句子。

同时,还可以适当添加一些解释或注释,帮助读者更好地理解文献内容。

华侨大学本科毕业论文格式要求一、字数要求文、经、管、法类一般10000字左右,理、工、医类一般6000字左右(专业教学指导委员会有特别要求的除外)。

二、毕业设计(论文)应符合国家及专业部门制定的有关标准,符合汉语语法规范。

电子版毕业论文基本要求与书写格式应与印刷本一致,不得省略;毕业设计(论文)必须整合为一个word文档,毕业设计(论文)文件名格式:姓名+学号(如:张三0511112299)。

三、封面毕业设计(论文)的封面由学校统一印制,严格按照有关规定的格式排版、打印。

毕业论文开本尺寸均为a4,装订切齐后为205mm×290mm。

四、毕业设计(论文)文本规范化要求包括:任务书、统一封面、采用a4纸张、标题(宋体、三号)、目录(宋体、小四号)、中英文摘要(宋体、五号)、关键词(宋体、五号,不超过五个)、文本正文(宋体、小四号)、参考文献(宋体、小四号)、工程设计说明书、实验数据、图表、外文译文、附录和评审意见表等。

其中工程设计说明书、实验数据、图表、外文译文等项目是否要求由各专业根据实际情况确定。

五、题目题目应能准确概括整个论文的核心内容,简明扼要、引人注目,一般不宜超过20汉字,可用小标题加以说明。

六、摘要及关键词毕业设计(论文)的摘要应有中、英两种文字,中文摘要在前,英文摘要在后。

摘要的字数,以汉字计,一般不超过500字。

关键词应放在摘要页最下方(应另起一行),一般列4~7个,不超过15个汉字为宜,并按词条外延层次从大到小排列。

七、目录目录是体现毕业设计(论文)各章节名称和页码的详细记录,不能过于简单;目录的页码一定要与正文的章节以及附后的内容相符合。

八、绪论(或序言、引言)绪论内容应包括本课题对学术发展、经济建设、社会进步的理论意义和现实意义,国内外相关研究成果述评,本论文所要解决的问题,论文运用的主要理论和方法、基本思路和行文结构等。

撰写毕业设计(论文)的绪论时,不要与摘要雷同,不要诠释基本理论,不要推导基本公式,不要介绍研究方法细节,写法应开门见山,言简意赅,措词精炼。

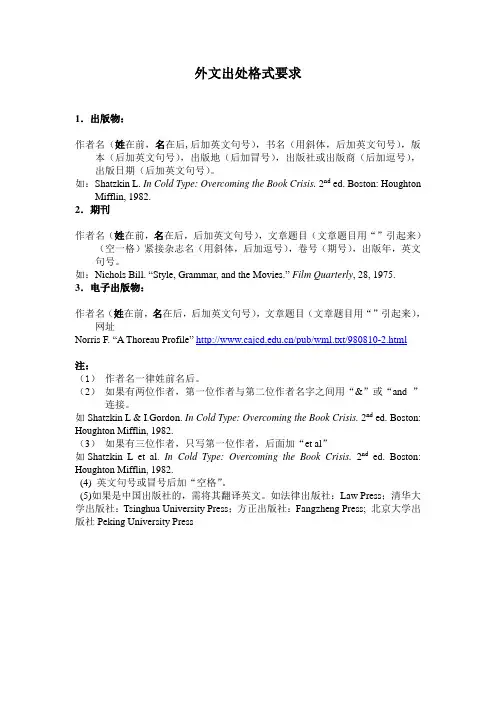

外文出处格式要求1.出版物:作者名(姓在前,名在后,后加英文句号),书名(用斜体,后加英文句号),版本(后加英文句号),出版地(后加冒号),出版社或出版商(后加逗号),出版日期(后加英文句号)。

如:Shatzkin L. In Cold Type: Overcoming the Book Crisis. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1982.2.期刊作者名(姓在前,名在后,后加英文句号),文章题目(文章题目用“”引起来)(空一格)紧接杂志名(用斜体,后加逗号),卷号(期号),出版年,英文句号。

如:Nichols Bill. “Style, Grammar, and the Movies.”Film Quarterly, 28, 1975. 3.电子出版物:作者名(姓在前,名在后,后加英文句号),文章题目(文章题目用“”引起来),网址Norris F. “A Thoreau Profile”/pub/wml.txt/980810-2.html注:(1)作者名一律姓前名后。

(2)如果有两位作者,第一位作者与第二位作者名字之间用“&”或“and ”连接。

如Shatzkin L & I.Gordon. In Cold Type: Overcoming the Book Crisis. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1982.(3)如果有三位作者,只写第一位作者,后面加“et al”如Shatzkin L et al. In Cold Type: Overcoming the Book Crisis.2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1982.(4) 英文句号或冒号后加“空格”。

(5)如果是中国出版社的,需将其翻译英文。

如法律出版社:Law Press;清华大学出版社:Tsinghua University Press;方正出版社:Fangzheng Press; 北京大学出版社Peking University Press。

文献翻译(小3号黑体,加粗,居中)

1英文原文(小4号黑体,加粗)

注:如果指导教师所给文献为pdf格式,则相应打印翻译部分,不必往此处逐次逐句敲英文文献。

答辩后请将英文文献电子稿及其他相关论文材料一并交回专业组。

2中文翻译(小4号黑体,加粗)

要求:

1.先完整地给出外文原稿;(可复印)

2.要完整地翻译所选材料,包括题目、关键词、摘要和正文,但人名及参考文献不须翻译;3.准确理解原文;

4.语言通顺、流畅;

5.格式规范(与正文格式一样,但字号改为5号字,行间距为1.25);

6.译文表达符合汉语习惯。

文献翻译资料原则上应与论文题目所涉及的主题或背景有关,文献内容要完整。

篇幅一般应在3000-5000英文单词左右。

中北大学

毕业设计外文资料翻译

原文名称Ab cd

中文名称甲乙丙丁

原文来源:作者,指期刊名称,卷期号,年月日,页码

或者其它信息

学生姓名:学号:

学院:

专业:

指导教师:

年月日

外文资料翻译要求

1.外文资料翻译中文部分内容,按照毕业设计说明书正文的格式要求排版,章节号、图号、表号、公式根据原文信息编排。

页眉填写“外文资料翻译”。

2、原始外文文献内容,直接复印原文装订在中文部分后面。

必须保留文献首页或封面,保留文献来源信息,不允许使用电子版进行二次编辑。

3、外文资料的选取提倡公开发表的与设计题目相关的科技期刊论文、图书片段、原始芯片资料、专业技术资料。

禁止选用没有来源的外文材料。

翻译后的中文部分篇幅达到10页以上即可,尽量保证翻译文献的完整性。

4、严禁机器翻译。

如果发现,直接取消答辩资格。

1 总要求(General Requirements)1、用英文撰写、字数要求学士论文长度为 4000 字,以能清楚、充分地论证某一论题或描写、解释某一发现为最低限度。

以上字数的统计范围仅限于论文正文,不包括论文摘要、目录、注释、参考书目和致谢。

2、格式要求论文一般由以下部分组成,并按此顺序排列:1. 英文标题页(English title page)2. 学位论文原创性声明(答辩时另发)3. 英文提要(Abstract)4. 中文提要(Chinese abstract)5. 目录(Contents)6. 正文(Text)7. 注释(Notes 非必须)8.参引文献(References,见附录)9. 致谢(Acknowledgements)(2)字体和字号:正文中大标题采用Times New Roman 小四号加粗(Introduction和Conclusion两词四号加粗,次标题以下采用 Times New Roman 小四号加粗,正文采用 Times New Roman 小四号字。

注意:大标题和次标题不得采用句子。

(3)行距:一律 1.5 行距。

(4)页边距:2cm。

3、注释要求(一律采用“尾注Notes”,用序号,按出现顺序排列:名字在前,姓氏在后,其他与参考文献同。

)4、从论文的正文至致谢,均要求采用“页眉”(页眉右对齐)和“页码”(页码应居中)。

并在目录中标出。

封面(空两行;页边距为2cm)(Please write the English title of your thesis here)(Arial 一号加粗居中)(Please write the Chinese title of your thesis here)(宋体一号加粗居中)(空两行)Submitted by (Please write your name here) (Arial 三号加粗居中)Student number ( Please write your ID here ) (Arial 三号加粗居中)Supervised by (Please write the name of your tutor here) (Arial 三号加粗居中)(空两行)Foreign Languages College(Arial 小三号加粗居中)Jiangxi Normal University(Arial 小三号加粗居中)(Insert Month here) (Insert Year here) (Arial 小三号加粗居中)Title of the thesis(Times New Roman 三号粗体居中)(空一行)Abstract(Times New Roman 小四号加粗):正文(Times New Roman 小四号)………………………………………………………………………………………………………(空一行)Key words(Times New Roman 小四号加粗):正文(Times New Roman 小四号)…………………………………………………………………………………………摘要之后另起一行,给出论文的关键词3-5个(关键词要用分号“;” 分隔,结束不用句号,关键词不能超过5个)中文题目(宋体三号粗体居中)(空一行)摘要(宋体小四号加粗):正文(宋体小四号)………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………(空一行)关键词(宋体小四号加粗):正文(宋体小四号)………………………………………………………………………………………………(用分号“;”分隔,结束不用句号,)(空一行)提要格式要求:1、中文、英文摘要分页打印2、A4纸打印3、页边距:2cm4、行距:1.5倍行距Contents (Times New Roman 三号粗体居中)(空两行)Abstract (i)摘要 (ii)Introduction (1)1. ……………………………………………………………………………………1.1 ……………………………………………………………………………………1.2 …………………………………………………………………………………..2. ……………………………………………………………………………………..2.1 …………………………………………………………………………………..2.2 …………………………………………………………………………………..2.3 ……………………………………………………………………………………3. …………………………………………………………………………………….…Notes………………………………………………………………………………………….. Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………. Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………目录格式要求:目录要自动生成!!所有标题都设为一级标题并顶格排列1、字体要求:Times New Roman 小四号粗体2、A4纸打印3、页边距:2cm4、行距:1.5倍行距5、论文内容排序:封面—声明—Abstract—摘要—Contents—正文—尾注—参考文献—致谢(空一行)Introduction (Times New Roman 四号加粗居中)(空一行)(5spaces) 正文……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………(空一行)1 (Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1.1(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1.1.1(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1.1.2(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1.2(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1.2.1(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1.2.2(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 (Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2.1(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2.1.1(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2.1.2(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2.2(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2.2.1(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2.2.2(Times New Roman小四号加粗)(5spaces) 正文……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 (Times New Roman小四号加粗)4 (Times New Roman小四号加粗)…Conclusion(Times New Roman 四号加粗居中)(5spaces) 正文………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………(另起一页)Notes(Times New Roman 四号加粗居中)正文(Times New Roman 小四号)[1]作者,书名(英文书名格式为Times New Roman小四号斜体;中文书名格式为《宋体小四号》),出版社,出版时间:页码.(有一实心点作为句号)[2]如出处同上一个注释,则标为ibid(空一格)(页码).[3]……(另起一页)Bibliography(Times New Roman 四号加粗居中)英文参考书目(按首写字母顺序排列)网络参考资料中文参考书目(按汉语拼音顺序排列)参考文献写作规范1.说明(1)文献目录应另页书写,外文文献排前,中文文献排后。

文献综述外文翻译写作规范及要求文献综述是对一定范围内已有文献的综合评述和总结,旨在回答特定研究问题、揭示研究现状、批判前人工作或发展新的研究方向等。

以下是文献综述和外文中文翻译的写作规范及要求:文献综述写作规范及要求:1.选择适当的文献范围:确定综述的主题和范围,选择与主题相关的高质量文献。

2.搜集文献:利用数据库、图书馆和互联网等途径,广泛搜集相关文献。

3.文献筛选:根据综述的目标和问题,筛选出与主题相关、有代表性的文献。

一般建议引用近几年的研究,但也可以引用经典文献。

4.综述结构:按照逻辑顺序,将文献分类、总结和评价。

一般包括引言、方法、结果和讨论等部分。

5.文章结构和语言:注意文章结构的连贯性和条理性,使用准确的科技词汇和语言,注意段落和句子的清晰性。

6.学术文献引用格式:按照学术规范,使用适当的引用格式,如APA、MLA等。

外文中文翻译写作规范及要求:1.翻译准确:理解原文意思,确保准确翻译每个词和句子。

2.语言流畅:在保证准确性的基础上,使译文语句通顺、流畅,符合汉语表达习惯。

3.词汇选择:选择恰当的词汇,尽量避免直译和生硬的译文,注意上下文的语境和词语的用法。

4.文化转换:针对涉及特定文化细节的部分,进行文化适应和转换,使读者能够理解和接受。

5.段落和结构:保持原文段落和结构的清晰,正确表达文章的逻辑和条理。

6.校对和修改:仔细校对翻译的准确性、语句的通顺性和表达的准确性,进行必要的修改和完善。

7.注明出处:在译文中注明原文的出处,并按照学术规范进行引用。

以上是文献综述和外文中文翻译的一般写作规范和要求,具体可以根据不同学科领域和学术期刊的要求进行调整和补充。

毕业设计/论文开题报告课题名称院系专业班姓名评分指导教师华中科技大学武昌分校毕业设计开题报告撰写要求1. 开题报告主要内容1)课题设计的目的和意义;2)课题设计的主要内容;3)设计方案;4)实施计划。

5)主要参考文献:不少于5篇,其中外文文献不少于1篇。

2.撰写开题报告时,所选课题的课题名称也不得多于25个汉字,课题设计份量要适当,设计中必须是自己的设计内容。

3. 开题报告的字数不少于2000字(艺术类专业不少于1000字),格式按《华中科技大学武昌分校本科毕业设计/论文撰写规范》的要求撰写。

4. 指导教师和责任单位必须审查签字。

5.开题报告单独装订,本附件为封面,后续表格请从网上下载并用A4纸打印后填写。

6. 此开题报告适用于全校各专业,部分特殊专业需要变更的,由所在系在基础上提出调整方案,报学校审批后执行。

华中科技大学武昌分校学生毕业设计开题报告毕业设计/论文外文文献翻译院系专业班级姓名原文出处评分指导教师华中科技大学武昌分校20 年月日毕业设计/论文外文文献翻译要求:1.外文文献翻译的内容应与毕业设计/论文课题相关。

2.外文文献翻译的字数:非英语专业学生应完成与毕业设计/论文课题内容相关的不少于2000汉字的外文文献翻译任务(其中,汉语言文学专业、艺术类专业不作要求),英语专业学生应完成不少于2000汉字的二外文献翻译任务。

格式按《华中科技大学武昌分校本科毕业设计/论文撰写规范》的要求撰写。

3.外文文献翻译附于开题报告之后:第一部分为译文,第二部分为外文文献原文,译文与原文均需单独编制页码(底端居中)并注明出处。

本附件为封面,封面上不得出现页码。

4.外文文献翻译原文由指导教师指定,同一指导教师指导的学生不得选用相同的外文原文。

华中科技大学武昌分校本科毕业设计/论文撰写规范毕业设计/论文是学生在教师的指导下经过调查研究、科学实验或工程设计,对所取得成果的科学表述,是学生毕业及学位资格认定的重要依据。

本科论⽂标准格式论⽂常⽤来指进⾏各个学术领域的研究和描述学术研究成果的⽂章,它既是探讨问题进⾏学术研究的⼀种⼿段,⼜是描述学术研究成果进⾏学术交流的⼀种⼯具。

论⽂⼀般由题名、作者、摘要、关键词、正⽂、参考⽂献和附录等部分组成。

论⽂在形式上是属于议论⽂的,但它与⼀般议论⽂不同,它必须是有⾃⼰的理论系统的,应对⼤量的事实、材料进⾏分析、研究,使感性认识上升到理性认识。

本科论⽂标准格式1 为了统⼀规范法学专业(本科)毕业论⽂格式,现对毕业论⽂格式作如下要求: 1、统⼀使⽤A4纸,单⾯打印、装订,必须⽤⿊⾊墨打印。

2、毕业论⽂形式要完整,应当包括封⾯、⽬录、论⽂摘要、正⽂、注释、引⽤参考⽂献资料⽬录。

3、封⾯格式要求:封⾯左上⾓“开放教育试点法学专业本科毕业论⽂”,⿊体,⼩四号;毕业论⽂题⽬,⼩⼆号⿊体字;封⾯中间靠下:依次为——姓名、学号、学校(所在市级电⼤)、指导教师、写作时间,四号字、⿊体,2倍⾏距。

封⾯格式⽰范: 开放教育试点法学专业本科毕业论⽂(⼩四号字、⿊体) 论⽂题⽬(⼩⼆号⿊体字) 姓名: 学号: 学校: 指导教师: 写作时间: (四号字、⿊体,2倍⾏距,居中排列) 4、⽬录页:⽬录,宋体,⼩三号;⽬录的具体内容,宋体,⼩四号。

5、论⽂摘要页:论⽂摘要,宋体,⼩三号;论⽂摘要的内容,500字左右,宋体,⼩四号;关键词,宋体,⼩四号。

6、正⽂:论⽂题⽬,⼩⼆号⿊体字;正⽂中的⼤标题,⼩三号⿊体字;正⽂内容,⼩四号宋体字,正⽂字数不得少于6000字。

7、注释:注释,⼩三号⿊体;注释内容,宋体五号字。

8、参考⽂献资料:参考⽂献资料,⼩三号⿊体;参考⽂献资料内容,宋体五号字。

9、对所引⽤的他⼈的观点、参考的⽂献要注明出处(可⽤脚注、尾注的形式清楚地表现出来,注明作者、书籍名称或刊物、出版社、出版时间、页数等),引⽤其他参考资料也应注明资料来源。

10、正⽂段落的⾏间距:缩进,左:零字符,右:零字符;间距,段前:0⾏,段后,0⾏;1.5倍⾏距。

深大教务[2006]41号深圳大学本科生毕业论文(设计)撰写规范及要求(二○○六年十二月修订)毕业论文(设计)是实现培养目标的重要教学环节。

为保证本科毕业论文(设计)质量,提高本科生科学研究能力和学术素养,促进校内外学术交流,特制定《深圳大学本科生毕业论文(设计)撰写规范及要求》。

一、基本结构1.前置部分:封面、诚信声明、论文目录。

2.主体部分:中文摘要、中文关键词、正文、注释与参考文献、致谢、英文摘要和英文关键词。

3.附录部分(非必需):某些重要的原始数据、图纸等。

二、装订顺序1.封面2.诚信声明3.目录4.主体部分5.附录三、内容要求(一)前置部分1.封面:学校统一设计。

2.诚信声明:学生对所提交的毕业论文(设计)的独立性予以郑重声明。

其格式和内容由学校统一设计,学生手签生效。

3.目录目录由论文(设计)的章、节、附录等序号、名称和页码组成。

(二)主体部分主体部分要保证文章结构清晰,纲目分明,撰写论文通行的标题层次按以下五种格式编排:撰写论文可任选其中的一种格式,但所采用的格式须前后统一,不混杂使用。

1.中文摘要摘要是毕业论文(设计)研究内容及结论的简明概述。

其内容应说明论文(设计)的主要内容、试验方法、结果、结论和意义等。

中文摘要不少于200字。

2.关键词关键词是指论文中最主要、最关键、重复频率最高的专业名词或词组,有助于读者了解全篇主旨。

设置数量一般为3-4个,每词字数一般在6个字之内。

关键词之间以一个分号符分隔。

3.前言(引言或序言)简要说明本项研究课题的提出及其研究意义(学术、实用价值);本项研究的前人工作基础及其欲深入研究的方向和思路、方法以及要解决的主要问题等。

4.正文正文是毕业论文(设计)的核心部分,应占主要篇幅。

正文内容必须客观准确、论证充分严密、论据充分、层次分明、语言流畅,符合学科及专业的有关要求。

正文中出现的符号和缩语应采用本专业学科的权威性机构或学术团体所公布的规定。

各学院可制定细则,报教务处备案。

外语专业本科毕业论文注释及参考文献格式要求一.注释外语专业学生学位论文的注释采用尾注(End-notes)和夹注(In-text Citations),不采用脚注。

1. 尾注(Endnotes)在正文需注释处的右上方按顺序加注数码①②③……,在全文之后写注文,每条加对应数码,回行时与上行注文对齐。

2. 夹注(In-text Citations )某些引文或所依据的文献无需详细注释的,以夹注的形式随文在括弧内注明。

A. 来自专著或文章的直接引语,作者姓名在文中已经出现格式:出版年份:页码。

Example:Rees said, “ ASiey aspects of lear ning are not stable, but cha ngeable, this ope ns the way for the role of the teacher as the pre-em inent mediator in the process" (1986:241).B. 来自专著或文章的直接引语,作者姓名在文中没有出现格式:作者姓名,出版年份:页码。

Example:"One reason perhaps is that the Chinese audienee are more familiar with and receptive to Western culture tha n the average En glish readers is to Chin ese culture" (Fung, 1995:71).C. 来自专著或文章的间接引语,作者的姓名在文中已经提到格式:出版年份:引文页码。

Example:According to Alun Rees (1986:234), the writers focus on the unique contribution that each in dividual lear ner brings to the lear ning situati on.D. 来自专著或文章的间接引语,作者的姓名在文中没有提到格式:作者姓名,出版年:引文页码。

格式要求4-外文文献翻译封面及内容要求毕业设计(论文)外文文献翻译院系:商学系年级专业:08国际商务姓名:石华聪学号:0801022145附件:The Development of Transportation andLogistics in Asia: An Overview指导老师评语:指导教师签名:年月日Western countries to low-cost Asian developing countries, Asian economies have been growing rapidly and have become the world factory of finished goods. Asia's trade has soared over the past two decades, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) in particular recording explosive growth. The PRC' s exports grew at an average of more than 18 percent per year between 1990 and 2007, while the other eight emerging economies among Asia's top-10 exporters recorded export growth of more than 10 percent a year (Brooks and Stone 2010). A business model that is integrated and global, uses direct distribution, and emphasizes shippinghigh-value products from Asian factories directly to worldwide markets has been developed by multinational firms. This integrated model replaces the traditional multiechelon, pushbased intemational distribution model; it also helps to reduce redundant inventories along the global supply chain and speeds up time to market (Su 2007). Due to all these changes, Asia now accounts for about one-fourth of world trade and world gross domestic product (GDP), respectively (World Bank 2006).With about 4.1 billion people in 2009 (PRB 2009), Asia is the most populous region in the world, accounting for 60 percent of populationand representing enormous market opportunities for multinationalfirms. There are around 20 cross-regional free trade agreements (FTAs) at different stages of implementation there. The consolidation of FTAs improves economic welfare compared to the current bilateralism. A broad Pan-Asian agreement (covering goods, services, and trade costs) involving East Asian and South Asian economies is estimated to offer significant improvement to the general welfare through gains to global income of around $261 billion (François, Rana, and Wignaraja 2009). All East and Asian and South Asian members of such an agreement would benefit from closer subregional cooperation. For trade-related infrastructvire, the dominant mode for freight transport between East Asia and South Asia remains ocean transport. This situation is expected to continue in the foreseeable future. The effectiveness of ocean transport and other trade-related infrastructure to respond to growing East Asia-South Asia trade depends on regional ability to maintain high-quality and efficient logistics services at a competitive cost. The need for sea transport has been amplified, especially for time-sensitive goods, due to improvements in technology for containerization and air freight. Air cargo volume has grown rapidly and air cargo involving Asian countries, particularly within Asia, has much higher growth than in the world as a whole. Effective logistics service and intermodalshipping have enabled Asia to trade with more markets, more quickly, and often at lower cost (Brooks and Hummels 2009). However, in spite of their rich opportunities, Asian countries have yet to overcome challenges associated with fulfilling their potential. The availability of infrastructiure and of other trade facilitation services has fallen behind the pace of Asia's economic growth. The underdevelopment of transport and logistics infrastructure and lack of logistics infrastructure connectivity among Asian countries have been major barriers to further trade and economic development there (Armstrong, Drysdale, and Kalirajan 2008; Bhattacharyay and De 2009;Brooks and Stone 2010).The Emerging Features of Trade in AsiaTrade volume within Asia has been rising rapidly since the early 1980s. In 2006 Asia contributed one-fourth of world trade in goods, second in production after Europe (see table 1). As shown in table 2, about 50 percent of Asia's exported goods are moved within the region, which was lower than percentage of intraregion trade in Europe and North America, most likely due to lack ofwell-established FTAs in Asia. In parallel to grovñng intraregional trade, Asia's interregional trade has also grown over time. North America (21.6 percent) and Europe (18.4 percent) have become the two largest non-Asian destinations of Asia's exports (see table 2).The growth of trade on the part of the PRC trade is particularly notable. With a world share of about 9 percent in 2009 (Batson 2010), the PRC is driving Asia's exports intraregionally and interregionally. India's rise in the late 1990s has further fueled Asia's trade.Serving the growing international demand for goods and services after World War II, Asian economies have transformed from industrial production that is labor intensive to production that is capital intensive and technology driven. The changes have been reflected in the product shares of exports. For example, integrated circuits account for the highest share (78.33 percent) in intra-Asia manufacturing exports, whereas the personal and household goods account for the lowest share (20.42 percent).Intra-Asia exports of agricultural and mining products are even lower compared to their exports to the world (Bhattacharyay and De 2009). The nature of Asia's trade is changing and becoming more efficient due to its recent rapid growth. Higher-value, often lighter goods and trade services have gradually replaced bulky commodities, resulting in declining weight-to-value ratios. In particular, the information and communication technology (ICT) revolution has generated increased trade in ICT products and outsourced services, and the application of information technology in many public and private supply chain collaborations, as well as greater migration of highly skilled professionals within and across the regions(Hummels 2009). This change has had a major impact on the distance and destination of trade flows, the locations and fragmentation of production processes, the choice of transport mode, logistics facilities decisions, the harmonization and standardization of customs classifications and inspections, and thedemand for supporting infrastruct\ire. Pan-Asian connectivity and other facilitation efforts would, therefore, play important roles in sustaining Asia's trade growth. The connecti\dty for goods flowing within Asia or between Asia and other regions must be gradually enhanced to ensure reliable, better, and faster movement of cargo. Asia Transport and Logistics DevelopmentRecent studies have shown that globalization has resulted in increased international exchanges of products and services, and the identification and establishment of Asia-wide cross-border transportation network connectivity should now be a major goal (see Brooks 2008a, 2008b; Hummels 2009). Another set of studies in Asia show that countries with geographical proximity could benefit substantially from more trade, provided infrastructure and trade costs are improved (see Brooks 2008b; De 2008a, 2008b; Brooks and Hummels 2009). These studies aU call for effective and integrated transport and logistics networks for enhancing movement of goods and services; Asia has been notorious for fragmented production and economic networks across borders. The ongoing global financial problems make it even more critical for Asian countries to integrate transport and logistics networks to facilitate the growth of regional demands.Asia now faces a new world economy that is very different from theone that prevailed before the 1990s. In toda/s world, falling communication and transport costs—coupled with technological development—have reshaped the comparative advantages of economies (Krugman 1991,1993). However, the current leading position of Asian trade may be replaced if a true Pan-Asian connectivity of its logistics infrastructures is still missing. What Asia needs now is to reestablish a modern "Silk Road." The ancient trade route that stretched from Asia to Europe was, untu the 13th century, among the world's most important cross-border arteries. As trade is once again growing between Asia and the rest of the world, a modern Silk Road must be built for sustainable economic development in Asia (Bhattacharyay and De 2009). Efforts to develop an Asia-wide transport network have been attempted since the 1960s. However, little progress was achieved until the 1980s (UNESCAP 2006). During the 1980s and early 1990s, significant political and economic changes in this region ultimately facilitated the trade and mobility of factors of production in Asia. Subsequently, during the 1990s, an increase in the demand for physical connectivity to support an export-oriented growth strategy and to support a fragmented production network contributed to successful implementation of some transport corridors in the Greater Mekong Subregion and elsewhere in Asia.This infrastructure development suggests the important role of physical connectivity in regional cooperation. Nevertheless, the progress toward full regional connectivity in Asia still lags far behind need(Bhattacharyay and De 2009). Many political, economic, technical, and social factors have contributed to the slow progress of a transport network throughout Asia. Technical factors that hinder Asian transport integration include lack of effective overland official trade outlets and associated facilities (e.g.,India-Bangladesh and PRC-Lao People's Democratic Republic), lack of integrated railway networks (e.g., Myanmar-India and PRC-Vietnam), lack of transit trade (in the whole of Asia with some exceptions), lack of trade facilitation mechanisms (soft infrastructure), and lack of policy measures (especially in the interior part of Asia) (Bhattacharyay and De 2009).In 1992, the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) initiated the Asian Land Transport Infrastructure Development (ALTID) project, which aims to expand transport and communication linkages within the region and with other regions. The ALTID project consists of the Trans-Asian Railway (TAR), the Asian Highway (AH), and the facilitation of land transport. In the initial stages of implementation, the ALTID focused on formulating the TAR andAH networks and establishing related standards and requirements. The TAR and AH could become the major building blocks for developing an international, integrated, and intermodal transport system in Asia and beyond (Bhattacharyay and De 2009). The appendix provides an example of how the private sector has taken action to upgrade surface transportation in this region. Increasing port efficiency has reduced the average time that shipments spend in ports and at sea, leading to more frequent shipping and timely delivery. Furthermore, trade routes with high densities enable an effective use of hub-and-spoke design, in which small container vessels feed shipments into a hub, where containers are consolidated into larger and faster container ships for longer hauls. A recent study found that given transport costs accounting for about a 20 percent ad valorem tax equivalent on import prices in East Asia, an increase in port capacity by 10 percent leads to a decrease in across-the-board tariffs by 0.3 to 0.5 percent (Abe and Wilson 2009). In addition, John Wilson, Catherine Mann, and Tsunehiro Otsuki (2003) find that trade among the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum members could expand by US$254 billion, or 21 percent, if each APEC member that is below average in regulatory and customs barriers, port efficiency, and electronic business usage enhanced its capacity just halfway to theAPEC average (Brooks and Stone 2010). Air cargo in Asia has benefited substantially from growth in trade. As mentioned earlier, the weight-to-value ratios of trade have been declining in the past decades (Hummels 2009). This shows that exports in Asia are shifting from bulk shipments toward lighter and higher-value goods, implying an increasing demand for air shipping. Air cargo involving Asia has been leading the growth of world air cargo in the past two decades (ibid.). The international air cargoes of Europe-Asia, North America-Asia, and intra-Asia grew faster than the world average by 1.6 percentage points, 3.4 percentage points, and 6.9 percentage points, respectively (Hummels 2006). The trend in air cargo is consistent with that in trade growth. Several factors have affected the air cargo growth trend involving Asia in the past two decades. For the market between North America and Asia, four elements—economic activity, currency exchange rate, infrastructure improvement, and liberalization of air transport agreements—determine the air cargo volume between these two regions (Boeing 2010).For the intra-Asia air cargo market, the global production chain in Asia is getting mature and provides a sustainable source of growth. Because most countries in Asia are separated by ocean, air cargo is essential to regional development. Unlike U.S. carriers, whichprefer narrow-body aircraft, Asian carriers prefer wide-body passenger aircraft. Wide-body passenger aircraft provides huge capacity, equivalent to 50 weekly medium wide-body freighters in the top-10 pairings of Asian countries that conduct cargo traffic (Boeing 2010), offering sufficient capacity to support air cargo growth. The emerging role of the greater China region has challenged Japan's role within Asia. In the top-10 country pairs (see table 3), the greater China region—including the PRC, Hong Kong, and Taiwan—is involved in 7 out of 10 pairs, whereas Japan is in only 5. It is expected that the regional integration among Greater China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will continue boosting the air cargo growth within this region. The importance of a high-quality logistics infrastructure varies by commodity, depending on three factors (Arnold 2009). First, there are the importers' scheduling requirements. Timeliness is particularly important to just-in-time supply chains in sectors such as fashion clothing or high-tech products, and to retailers with coordinated national sales programs.The second factor is the shelf life of the commodity, reflecting volatility of demand or physical deterioration. Third is the value of the commodity per shipment unit, for example, twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU) or per metric ton. The needs of logistics and supply chain services related to highervalue- added products are growing at a fast pace. Giyen its diversity, Asian trade, particularly Asia trade supply chains, is affected by each of these factors. Soft infrastructure may contribute more than physical infrastructure does to increased trade and its profitability. Bureaucracy, inefficient institutional structures, and policy may result in reduced margins from international trade. Erom 2006 to 2007, most developing Asian countries were actively implementing reforms of their trade policies. Erom 2007 to 2008, Thailand and the Philippines were prominent reformers; during 2008 and 2009 Vietnam and the PRC were. In 2010, 71 percent of East Asian economies reported at least one significant trade facilitation reform (Brooks and Stone 2010). On average, manufacturers in Asia require 11 days to export to their Organisation for EconomicCo-operation and Development (OECD) counterparts, which is significantly shorter than the approximately 23 days required to export to non-OECD coimtries (table 4) (Brooks and Stone 2010). Logistics services, which connect supply chains across the regionand determine the location of foreign direct investment within the region, are a vital component of Asia's global competitiveness. Improved efficiency in infrastructure service facilitates trade and leads to huge cost savings, equivalent to relocating production thousands of kilometers closer to trading partners. Economies such as those of the PRC, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand have currently built well-developed logistics systems to facilitate international trade. The comparison of logistics performance internationally shows that East Asia performs relatively well compared to other developing regions, such as South Asia, but still lags well behind developed countries (Arvis et al. 2007; Brooks and Stone 2010).Opening up Asia's trade potential is very challenging. Costs for having interrupted road or railway connectivity across the region or for lack of facilitation of border trade can offset gains achieved from trade preferences as proposed under several FTAs and otherarrangements. Therefore, the need for an environment to better enable trade that offers lower trade costs has gained momentum in Asia. However, a favorable regional climate to establish amodern-day Silk Road is lacking. Hence, the agenda of Asian regional cooperation has to go beyond "policy" barriers by including "nonpolicy" barriers. For example, in order to facilitate seamless connectivity in Asia and accelerate the movement of goods and services in Asia and beyond, Asian countries have to integrate the different subregional transport corridors and modes (roads, rails, maritime, and air shipping). Moreover, they have to remove institutional bottlenecks and barriers that are raising costs and lowering regional competitiveness (Bhattacharyay and De 2009).Future DevelopmentAsia has presented itself in the past three decades as a region of fast-growing economies, particularly among those with emerging markets. However, weak regional connectivity has become one of the major barriers constraining the full potential of regional economic integration and growth. A true regional collaboration among Asian countries is very important for establishing Asia-wide economic integration and supply chain connectivity.In order to build a highly integrated Asia, an innovative andcomprehensive approach is needed to address the physical infrastructure issues and nonphysical soft infrastructure issues. Whereas the former includes the airports, seaports, dry ports, roads, rail, inland waterways, maritime transport, and information and communication networks, the latter covers cross-border transit facilitation measures, customs clearance, and other facilitating policies and regulations. Addressing the issues above requires collaborative efforts among Asian countries, bilateral donor agencies, multilateral development banks, UN agencies, intergovernmental organizations, professional associations, and the private sector. Above aU, highlevel commitments and policy direction are crucial for the successful integration of logistics infrastructxires in the Asian region (Bhattacharyay and De 2009). Potentially what can be done and the positive outcomes that result from a well-connected region are many and far reaching. In broader terms, the efficiency gains in an interconnected network for transport (and trade) would lead to more than just easier movement of goods; overall, it would result in higher growth and greater prosperity. In fact, a 1 percentage point increase in the ratio of trade to GDP would lead to a 2 to 3 percent increase in income per capita, while a 10 percent efficiency gain in supply chain connectivity would lift APEC's real GDP by US$21 billionper year and generate thousands of jobs (Centre for International Economics 2009).APEC has consistently made progress in reducing barriers to trade that are "at-the-border" (e.g., tariffs) and "behind-the-border" (e.g., regulatory impediments). In 2009, in order to address the remaining frontier—namely "across-the-border" barriers—APEC launched a supply chain framework to specify what needs to be done to create an integrated supply chain and an interconnected region. The goal is clear: to achieve multimodal connectivity by air, land, and sea; and to facilitate a seamless flow of goods, services, and people throughout the Asia-Pacific (APEC 2010).In collaboration with business, academia, and government sectors, APEC has identified eight critical choke points in Asian supply chains and is focusing on relieving them (APEC 2009). Broadly, they relate to regulatory impediments, customs inefficiencies, and inadequate transport networks and infrastructure. Tackling these bottlenecks requires a coordinated and concerted effort by all APEC members and their alliances. Members of APEC are developing concrete action plans which have already been disclosed in May 2010, and full implementation wiU start in 2011 (APEC 2010).。