HP公司项目管理资料(英文)

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:1.62 MB

- 文档页数:59

HP ITPS绩效套件简要说明手册2011年9月目录一、HP IT战略、规划和治理 (3)1.主管积分卡对应产品--HP IT Executive Scorecard (3)2.IT财务管理— HP PPM Financial Management (4)3.项目与组合管理—HP Project Portfolio Management (4)3.1时间管理模块-- HP PPM Center Time Management (4)3.2计划管理模块—HP PPM Plan Management (4)3.3资源管理--HP PPM Center Resource Management (4)4.应用组合管理--Application Portfolio Management (5)5.劳动力和厂商管理--Workforce and Vendor Management (5)二、安全情报和风险管理 (5)1.软件安全保证--Fortify (5)2.安全信息和事件管理--Arcsight (6)3.企业网络安全--Tippingpoint (6)三、应用生命周期管理 (6)1.应用质量管理--HP Application Lifecycle Management (6)2.需求管理-- HP Quality Center (6)3.开发管理-- Application Lifecycle intelligence (7)4.应用治理--Application Governance (7)5.性能验证—LoadRunner& Performance Center (7)6.应用安全验证—Fortify、WebInspect、QAInspect、AMP (8)四、运营管理 (8)1.数据中心自动化—Datacenter Automation center (8)2.客户端自动化--HP Client Automation Center (8)3.应用可用性和性能—Business Availability Center (9)4.系统管理—Operations Manager Center (9)5.网络管理—Network Manager Center (9)6.IT服务管理—IT Service Management (9)7.配置管理系统—Configuration Manager Center (10)8.资产管理-- HP Asset Manager (10)五、信息管理 (10)1.数据保护- HP Data Protector (10)2.信息归档-- Information Archiving (11)3. 企业档案管理—HP TRIM (11)六、业务分析 (11)七、HP服务 (12)HP ITPS绩效套件一、HP IT战略、规划和治理HPIT战略规划和治理解决方案,帮助企业建立以客户为中心的企业信息架构,加速企业的资源优化整合,提供可预期的IT建设路线图、IT投资和业务回报,降低企业运营成本,降低投资风险,加快业务部署,实时控制项目进展,改善客户服务质量,保障企业IT投资回报的可预见和最大化。

前言以下资料中,每一章的开始部分都有本章的知识要点,概括了PMBOK 体系的重要知识点,这些知识点一定要理解。

文件中,红色字部分是PMBOK 中的重要术语、重点考点以及各过程的输入、输出及工具;黑色字部分是模拟题中曾经出现过的PMBOK体系考点;绿色字部分是其它参考书、模拟考题的辅助知识。

第一章项目管理框架部分【本章知识重点】★项目及其特点;★项目和运营的相同点与不同点。

★项目管理及其几个过程;★Program / project / subproject的区别与关系。

【电子笔记】1.1 项目管理知识体系(PMBOK)PMBOK是美国项目管理学会(PMI)提出的一个涵盖面很广的项目管理知识体系,内容包括项目管理(Project Management)这一职业的知识总和。

PMBOK不是教科书,它并没有详细地解释知识体系中的那些术语,它只提供了项目管理的一种正确思路和管理技能与知识。

PMBOK是以西方人的思维方式,尤其是美国人的思维方式来看待项目管理问题的,所以我们在学习过程中要习惯他们考虑问题的思路。

PMI一直不遗余力地促使为项目经理放权,期望创造一个良好的环境给项目团队。

PMI很重视历史资料和检验教训,PMBOK知识体系将这些信息作为数据库的一部分,供项目以及执行组织的其它项目使用。

数据库是知识管理的基础。

项目管理是管理偶然性的职业。

我们成为PM(Project Manager)通常都是偶然的。

组织任命某人为PM,有时只是对其技术绩效的嘉奖。

1.2 什么是项目?项目(Project)的定义:为创造某项独特产品、服务或结果所做的一次性努力。

1.2.1一次性( Temporary )一次性是指每个项目都有确定的(Definite)开始和确定的结束。

当项目目标达到时,项目也就结束了。

如果项目目标明显无法完成时,一般来说项目会终止。

一次性一般不适用于项目所产生的产品或服务。

项目经常会产生比项目本身更久远的,事先想到或未曾料到的社会、经济和环境影响。

HP Performance Center 9.5操作指南目录HP Performance Center 9.5操作指南 (1)1.Performance Center简介 (3)1.1 数据管理 (3)1.2 用户管理 (4)1.3 资源管理 (4)1.4 项目管理 (4)1.Performance Center简介2009年4月,惠普发布了一款旨在帮助IT机构在整个应用生命周期内改进性能管理的新版软件和服务HP Performance Center 9.5。

该产品是包括业内最畅销的负载测试软件HP LoadRunner在内的一款企业级性能测试软件套件,支持客户在测试周期内根据业务需求验证应用的性能,帮助客户降低应用上线后在部署和更新方面的风险。

同时,惠普还更新了多项应用生命周期管理服务,希望以此帮助IT机构创建卓越中心(CoE),使其能够在降低IT 成本的同时提高应用的质量。

为了满足不断变化的业务需求,IT机构正在采用Web 2.0等新技术提供更加强大的功能。

此外,他们还采用了灵活开发等新流程来缩短交付时间。

这些新技术和新流程使得在应用测试阶段确定潜在性能问题的工作变得越发困难。

新发布的HP Performance Center 9.5软件和惠普应用程序生命周期管理服务能够帮助企业从容应对新Web 2.0应用带来的挑战。

而且,该软件和服务还支持企业内部各个团队高效协作,确保应用的性能和规模能够满足业务需求。

HP Performance Center 9.5软件能够帮助客户:·将各种性能测试功能整合到卓越中心(CoE),以共享测试数据,提高分析新趋势的能力。

趋势分析有助于客户了解各个迭代之间的性能变化,从而通过快速配置优化应用的性能。

·支持新技术和框架(例如Adobe? Action Message Format,简称AMF),以发现和修复Web 2.0应用中的性能问题。

这有助于企业构建功能丰富的互联网应用,改进最终用户体验,提高客户满意度。

High Pressure Water Jetting (HPWJ)1.0 PURPOSEThe purpose of this standard is to define minimum requirements for High Pressure Water Jetting (HPWJ) operations.2.0 SCOPEThe standard covers the Safety precautions to operate and maintain HPWJ machine to clean tubes and other equipment, and for cleaning concrete or other structures within SABIC and it’s Affiliate facilities.3.0 DEFINITIONS3.1High Pressure Water Jetting (HPWJ) Machine: The HPWJ machines arecapable of delivering water, at the cleaning tip, up to a pressure of about 680kg/cm2. The velocity of water emerging from the cleaning nozzle is almosttwice the sound velocity (2 Mach), i.e., almost 2240 km per hour.The operation is used to clean tubes and other equipment, and for cleaningconcrete or other structures. The water from HPWJ jet becomes almost asstrong as penetrating bullet.3.2Shall: Signifies mandatory requirements.3.3Should: Signifies recommended/optional requirements.4.0 REQUIREMENTSSABIC and its Affiliates using High Pressure Water Jetting (HPWJ) machines shall develop procedures and programs that meets the following requirements:SABIC Industrial Security shall be consulted for any clarifications to this standard.The clarification given by SABIC Industrial Security shall be complied with and considered final.4.1Only trained personnel shall be allowed to operate the HPWJ machine.4.2Appropriate Work permit shall be obtained for carrying out High PressureWater Jetting.4.3The High Pressure Water Jetting work shall be done on buddy system, i.e.,operator and helper.4.4Appropriate Personnel Protective Equipment shall be worn by all personnelinvolved in HPWJ. The following Personal Protective Equipment is recommended for personnel involved in HPWJ operations:4.4.1Safety Helmet4.4.2Full leather/PVC sleeves4.4.3Safety glasses4.4.4Full leather/PVC coat4.4.5Waterproof leather or thick rubber gloves4.4.6Gum boots4.4.7Face shield for operating crew.4.5The machine and working area shall be properly cordoned off/barricaded andpersonnel not involved in the work shall not be allowed to enter the area.4.6Appropriate protection shall be provided for the passerby.4.7High pressure hose shall not have kinks, cuts or chipping on outer rubber.Hose shall have pressure rating engraved on its couplings. High pressure hoses shall be pressure tested, once every year by a competent authority.Records of all such test shall be kept4.8Rubber hose and particularly its fittings shall be visually checked for anydamage, before every use.4.9Lance nozzle shall be designed to prevent release from mounting by impact.Mounting for the lance to vessel shall be so designed that falling scale is deflected from the mounting.4.10Lance shall not have any dents, nicks or twists and shall be inspected visuallybefore each use.4.11Only calibrated pressure gauge(s) shall be used.4.12All Safety (hand and foot operated) and other actuators and Safety valves onhigh-pressure side shall be tested, once every year or after each pop-up or repair, by a competent authority. Records of all such test shall be kept.4.13The mode of pressure regulating knob, to increase or decrease the pressure,shall be indicated by arrow heads.4.14 A failsafe (deadman) emergency dump control shall be provided for:4.14.1Electrical malfunction.4.14.2Operator or observer inattentiveness.4.14.3Dump control being unattended.4.15Appropriate precautions shall be taken before starting the machine. It isrecommended to ensure the following before switching on the motor:4.15.1The automatic pressure relief valve is depressed into load position.4.15.2The f oot operated valve is not pressed by the operator’s foot.4.15.3The trigger of spray pistol is not pulled.4.15.4The suction filter is not choked.4.15.5The water supply valve is open.。

外包hp项目的流程和注意事项下载温馨提示:该文档是我店铺精心编制而成,希望大家下载以后,能够帮助大家解决实际的问题。

文档下载后可定制随意修改,请根据实际需要进行相应的调整和使用,谢谢!并且,本店铺为大家提供各种各样类型的实用资料,如教育随笔、日记赏析、句子摘抄、古诗大全、经典美文、话题作文、工作总结、词语解析、文案摘录、其他资料等等,如想了解不同资料格式和写法,敬请关注!Download tips: This document is carefully compiled by theeditor. I hope that after you download them,they can help yousolve practical problems. The document can be customized andmodified after downloading,please adjust and use it according toactual needs, thank you!In addition, our shop provides you with various types ofpractical materials,such as educational essays, diaryappreciation,sentence excerpts,ancient poems,classic articles,topic composition,work summary,word parsing,copy excerpts,other materials and so on,want to know different data formats andwriting methods,please pay attention!一、外包 HP 项目的流程1. 需求分析与客户沟通,了解项目的具体需求和目标。

Knx ConsultingMark Yuan , PMP/ME Jun 2017 @ Hong Kong MarkYuan05@学员版讲义,仅供参考。

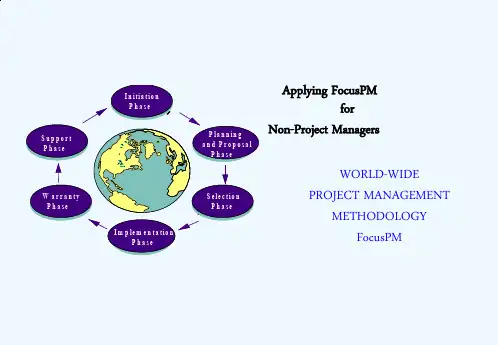

完善及更新甚不如讲师版讲义ØTo provide with the knowledge and tools to perform professional project management in your day-to-day work environment;ØTo enhance the practical soft skills on team development, stakeholders and communication management.MarkYuan05@学员版讲义,仅供参考。

完善及更新甚不如讲师版讲义Day-2:ØExecuting & Controlling - Team Development - Quality- Performance- Changes- Life CycleØClosing ProjectØWrap-upDay-1:ØIntroduction ØInitiating Project ØPlanning Project - Scope - Schedule - Cost - Resource & Comm - Risk MarkYuan05@学员版讲义,仅供参考。

完善及更新甚不如讲师版讲义Mark YuanA lifetime educator and management advisorl PMI Member and professional trainerl Master's degree from the UBC (Canada)l Prj specialist in Bell (Canada, 2007~2009)l Product Manager in Fujitsu (China, 1998~2005)Clients: IBM, HP , eBay, NEC, Daimler (Mercedes-Benz), Schneider,ThyssenKrupp, Siemens, iSoftStone, ITW, Honeywell, Fujitsu, CIMC Raffles, Jinan Software Park, Bell Canada, VanCitySaving Credit Union, BestBuy, BC Hydro, Delta Horizon, 360 Network, WWF(World Wildlife Fund)v Namev Team Leaderv Case StudyMarkYuan05@ 1960s:mass production, focus on productivity1970s:quality management1980s:product diversification1990s:customization2000s:change and competition学员版讲义,仅供参考。

PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT : FUTURE DEVELOPMENTSDr David HillsonManager of Consultancy, PMP Services Limited7 Amersham Hill, High Wycombe, Bucks HP13 6NS, UK ABSTRACTProject risk management has been recognised for some time as a formal discipline in its own right, and there is growing consensus on the elements which comprise best practice. However the project risk management field has not fully matured and there are a number of areas requiring further development. This paper presents the author’s perceptions on the directions in which project risk management might develop in the short to medium term, comprising five key areas. These are : organisational bench-marking using maturity model concepts; integration of risk management with overall project management and corporate culture; increased depth of analysis and breadth of application; inclusion of behavioural aspects in the risk process; and development of a body of evidence to justify and support use of risk management. INTRODUCTIONRisk management within projects has developed in recent years into an accepted discipline, with its own language, techniques and tools. Most textbooks in project management now include sections on risk management, and there is a growing library of reference texts specifically devoted to the subject in its own right. The value of a proactive formal structured approach to managing uncertainty has been widely recognised, and many organisations are seeking to introduce risk processes in order to gain the promised benefits.It appears that project risk management is a mature discipline, yet it is still developing. Many risk practitioners would agree that risk management has not yet peaked, and that there is some way to go before its full potential as a management support tool is realised. A number of initiatives are under way to extend the boundaries of the subject, and there is a danger that risk management could dissipate and lose coherence if some sense of overall direction is not maintained. This paper presents five areas where the author perceives a need for active development, and which are proposed as an agenda for change in the short to medium term, covering the next three to five years.THE CURRENT SITUATIONBefore detailing areas for possible development, it is helpful to survey the current position of project risk management. This draws on the author’s experience as Chairman of the Risk Specific Interest Group (SIG) for the UK Association for Project Management (APM), his involvement with the Risk SIG of the US Project Management Institute (PMI), his position as a risk practitioner in the UK and Europe, and his view of current developments in the field as Editor of this journal.Use of formal risk management techniques to manage uncertainty in projects is widespread across many industries, and there are few sectors where it is completely absent. In many areas its use is mandatory or required by client organisations, including defence, construction, IT, offshore and nuclear industries. Other sectors are recognising the potential of risk management as a management support tool and are beginning to implement risk processes within their own projects. In the UK, various government departments are implementing risk management on projects, notably the Ministry of Defence (MoD)1, and departments with IT projects which use PRINCE2 or PRINCE2 3 guidelines developed by the CCTA.Risk processes have been applied to all stages of the project lifecycle, from conception, feasibility and design, through development into implementation, operations and disposal. The contribution which risk management can make at each lifecycle stage is different, but is nevertheless recognised as important.Despite this apparent widespread take up of project risk management across business at large, the extent to which risk processes are actually applied is somewhat variable. Many organisations adopt a minimalist approach, doing only what is necessary to meet mandatory requirements, or going through the motions of a risk process with no commitment to use the results to influence current or future strategy.A significant aspect of the project risk management field is the extent of current infrastructure support available. There is a growing academic base for the subject, and risk management is included in a variety of undergraduate courses. In addition, several MSc degrees in risk management exist, and the body of research in the topic is growing. This has led to a broad risk literature, including both textbooks and journals.A number of standards and guidelines have also been published which include aspects of project risk management to varying degrees4-12, although there is no internationally accepted risk standard at the time of writing. The discipline is supported by several professional bodies, including the UK Institute of Risk Management13 (whose remit is broader than just the project risk field), and project management bodies such as the UK APM14 and the US PMI15 (both with dedicated SIGs for project risk management). Software vendors have also provided a range of tools to support the risk process, and a growing number of consultancies offer project risk management support to clients.One important feature is the consensus on current best practice within project risk management. The APM Risk SIG is recognised within the UK as representing the centre of excellence for the subject within the UK, and internationally the leading position of the UK in project risk management is also widely accepted. A recent publication from the APM (the “Project Risk Analysis & Management (PRAM) Guide”16) has captured the elements of current best practice as perceived by the Risk SIG, and this has been expanded and expounded elsewhere17. This covers high level principles in the form of a prototype standard for risk management, and presents a generic process. The PRAM Guide also deals with organisational issues (roles and responsibilities), psychological aspects (attitudes and behaviour), benefits and shortfalls, techniques, and implementation issues, presenting a comprehensive compilation of current practice. Other best practice documents also exist, although not with such broad coverage18,19.AREAS FOR FUTURE DEVELOPMENTThe current situation in project risk management outlined above represents a position where there is broad consensus on the fundamentals, with a mature and agreed process, supported by a comprehensive infrastructure. The core elements of project risk management are in place, and many organisations are reaping the benefits of implementing risk processes within their projects and wider business, despite the variable depth of application. There are however a number of areas where the discipline needs to develop in order to build on the foundation which currently exists. It is this author’s belief that development of the following five areas would greatly enhance the effectiveness of project risk management :• organisational bench-marking using maturity model concepts• integration of risk management with overall project management and corporate culture• increased depth of analysis and breadth of application• inclusion of behavioural aspects in the risk process• development of a body of evidence to justify and support use of risk management Each of these areas is discussed in turn below, outlining how project risk management might benefit from their inclusion.ORGANISATIONAL BENCHMARKINGAn increasing number of organisations wish to reap the benefits of proactive management of uncertainty in their projects by developing or improving in-house project risk management processes. It is however important for the organisation to be able to determine whether its risk processes are adequate, using agreed measures to compare its management of risk with best practice or against its competitors. As with any change programme, benchmarks and maturity models can play an important part in the process by defining a structured route to improvement.The Risk Maturity Model (RMM)20,21 was developed as a benchmark for organisational risk capability, describing four increasing levels, with recognisable stages along the way against which organisations can benchmark themselves. The various levels can be summarised as follows :• The Naïve risk organisation (RMM Level 1) is unaware of the need for management of risk, and has no structured approach to dealing with uncertainty.Management processes are repetitive and reactive, with little or no attempt to learn from the past or to prepare for future threats or uncertainties.• At RMM Level 2, the Novice risk organisation has begun to experiment with risk management, usually through a small number of nominated individuals, but has no formal or structured generic processes in place. Although aware of the potential benefits of managing risk, the Novice organisation has not effectively implemented risk processes and is not gaining the full benefits.• The level to which most organisations aspire when setting targets for management of risk is captured in RMM Level 3, the Normalised risk organisation. At this level, management of risk is built into routine business processes and riskmanagement is implemented on most or all projects. Generic risk processes are formalised and widespread, and the benefits are understood at all levels of the organisation, although they may not be fully achieved in all cases.• Many organisations would probably be happy to remain at Level 3, but the RMM defines a further level of maturity in risk processes, termed the Natural risk organisation (Level 4). Here the organisation has a risk-aware culture, with a proactive approach to risk management in all aspects of the business. Risk information is actively used to improve business processes and gain competitive advantage. Risk processes are used to manage opportunities as well as potential negative impacts.Each RMM level is further defined in terms of four attributes, namely culture, process, experience and application. These allow an organisation to assess its current risk processes against agreed criteria, set realistic targets for improvement, and measure progress towards enhanced risk capability.Since its original publication20, the RMM has been used by several major organisations to benchmark their risk processes, and there has been considerable interest in it as a means of assisting organisations to introduce effective project risk management. Other professional bodies are expressing interest in development of benchmarks for risk management based on the principles of maturity models22,23, and this seems likely to become an important area for future development.INTEGRATION OF RISK MANAGEMENTProject risk management is often perceived as a specialist activity undertaken by experts using dedicated tools and techniques. In order to allow project teams and the overall organisation to gain the full benefits from implementing the risk process, it is important that risk management should become fully integrated into both the management of projects and into the organisational culture. Without such integration, there is a danger that the results of risk management may not be used appropriately (or at all), and that project and business strategy may not take proper account of any risk assessment.At the project level, integration of risk management is required at three points.• The first and arguably most important is a cultural issue. The project culture must recognise the existence of uncertainty as an inherent part of undertaking projects.The nature of projects is to introduce change in order to deliver business benefits.Any endeavour involving change necessarily faces risk, as the future state to be delivered by the project differs from the status quo, and the route between the two is bound to be uncertain. Indeed there may be a direct relationship between the degree of risk taken during a project and the value of the benefits which it can deliver to the business (the “risk-reward” ratio). It is therefore important for the project culture to accept uncertainty and to take account of risk at every stage. The existence of risk and the need to manage it proactively within projects should not be a surprise.• Secondly, risk management must become fully integrated into the processes of project management. Techniques for project definition, planning, resourcing, estimating, team-building, motivation, cost control, progress monitoring,reporting, change management and close-out should all take explicit account of risk management. It is often the case that risk management is seen as an optional additional activity, to be fitted into the project process if possible. The future of effective risk management depends on developing project processes which naturally include dealing with risk.• Thirdly, risk tools must integrate seamlessly with tools used to support project processes. Too often differing data formats result in a discontinuity between the two, leading to difficulty in using risk outputs directly within project tools. It should not be necessary to use a specialist toolset for risk management, with import/export routines required to translate risk data into project management tools. At the practical level this would go a long way towards improving the acceptability and usefulness of risk management to project teams.In addition to these tactical-level integration issues, there is a broader need to develop strategic risk-based thinking within organisational culture. The denial of risk at senior management levels is a common experience for many project managers, and this can dilute or negate much of the value of implementing risk management in projects, if decision-makers at a higher level do not properly take account of risk. This author contends that there is a need for a cultural revolution similar to the Total Quality Management (TQM) phenomenon, if the required degree of organisational culture change is to be achieved. As with quality, risk management must be seen as an integral part of doing business, and must become “built-in not bolt-on”, a natural feature of all project and business processes, rather than being conducted as an optional additional activity.Such a development might be termed Total Risk Management (TRM), requiring a change in attitudes to “think risk”, accepting the existence of uncertainty in all human endeavours, adopting a proactive approach to its management, using a structured process to deal with risk (for example identify, assess, plan, manage), with individuals taking responsibility for identifying and managing risks within their own areas of influence. Clearly the implications of a TRM movement could be far-reaching, and further work is required in this area to define and promulgate the principles and practice of TRM, drawing on the previous experiences of TQM practitioners.INCREASED DEPTH AND BREADTHThere is general consensus about the risk management process as it is currently applied within projects, covering the techniques available for the various stages and the way in which risk data is used. Further development is however required to improve the effectiveness of risk techniques, both in their degree of operation and functionality, and in the scope of the situations where they are applied. These two dimensions of improvement are termed depth of analysis and breadth of application. The current level of risk analysis is often shallow, largely driven by the capabilities of the available tools and techniques. Qualitative assessments concentrate on probabilities and impacts, with descriptions of various parameters to allow risks to be understood in sufficient detail that they can be managed effectively. Quantitative analysis focuses on project time and cost, with a few techniques (such as Monte Carlo simulation or decision trees) being used almost exclusively. There are a number ofways in which this situation could be improved, leading to an increased depth of analysis :• Development of better tools and techniques, with improved functionality, better attention to the user interface, and addressing issues of integration with other parts of the project toolset.• Use of advanced information technology capabilities to enable effective knowledge management and learning from experience. For example it may prove possible to utilise existing or imminent developments in artificial intelligence, expert systems or knowledge-based systems to permit new types of analysis of risk data, exposing hitherto unavailable information from the existing data set (see for example references 24 and 25).• Development of existing techniques from other disciplines for application within the risk arena. Risk analysis for projects could be undertaken via methods currently used within such diverse areas as system dynamics, safety and hazard analysis, integrated logistic support (ILS), financial trading etc. Tailoring of such methods for risk analysis may be a cost-effective means of developing new approaches without the need for significant new work.The scope of project risk management as currently practised is fairly limited, tending to concentrate on risks with potential impact on project timescales and cost targets. While time and cost within projects are undeniably important, there are a number of other areas of interest which should be covered by the risk process. The breadth of application could be enhanced in the following ways :• Risk impacts should be considered using other measures than project time and cost, and should include all elements of project objectives such as performance, quality, compliance, environmental or regulatory etc. The inclusion of “soft”objectives such as human factors issues might also be incorporated, as it is often the people aspects which are most important in determining project success or failure. In addition, the impact of risks should be assessed against the business benefits which the project is intended to deliver.• The scope of risk processes should be expanded beyond projects into both programme risk management (addressing threats to portfolios of projects, considering inter-project issues) and business risk assessment (taking account of business drivers). While there are existing initiatives in both of these areas26,27, there is value in moving out from project risk assessment into these areas in a bottom-up manner, to ensure consistency and coherence.BEHAVIOURAL ASPECTSThere is general agreement on the importance of human behaviour in determining project performance28. This however is not usually translated into any formal mechanism for addressing human factors in project processes, including risk management. Future developments of project risk management must take more account of these issues, both in generating input data for the risk process, and in interpreting outputs.Considerable work has been done on the area of heuristics29, to identify the unconscious rules used when making judgements under conditions of uncertainty. There is however less insight into risk attitudes and their effect on the validity of the risk process. If risk management is to retain any credibility, this aspect must be addressed and made a routine part of the risk process. A reliable means of measuring risk attitudes needs to be developed, which can be administered routinely as part of a risk assessment in order to identify potential bias among participants. Accepted norms for risk attitudes could be defined, allowing individuals to be assessed and placed on a spectrum of risk attitude, perhaps ranging from risk-averse through risk-neutral to risk-tolerant and risk-seeking. Once potential systematic bias has been identified it can then be countered, leading to more reliable results and safe conclusions. The impact of risk attitude on perception of uncertainty should be explored to allow the effects to be eliminated.A further result of the inclusion of a formal assessment of behavioural characteristics in the risk process would be the ability to build risk-balanced teams. This would permit intelligent inclusion of people with a range of risk attitudes in order to meet the varying demands of a project environment. For example, it is clearly important for a project team to include people who are comfortable with taking risks, since projects are inherently concerned with uncertainty. It is however also important that these people are recognised and that their risk-taking tendency should be balanced by others who are more conservative and safety-conscious, in order to ensure that risks are only taken where appropriate.Work is in progress in this area30,31, but it is important that this should be fully integrated into mainstream project risk management, rather than remaining a specialist interest of psychologists and behavioural scientists. The standard risk process must take full account of all aspects of human behaviour if it is to command any respect and credibility.SUPPORTING EVIDENCEA number of studies have been undertaken to identify the benefits that can be expected by those implementing a structured approach to risk management32. These include both “hard” and “soft” issues.“Hard” measurable benefits include :• Better informed and achievable project plans, schedules and budgets• Increased likelihood of project meeting targets• Proper allocation of risk through the contract• Better allocation of contingency to reflect risk• Ability to avoid taking on unsound projects• Recording metrics to improve future projects• Objective comparison of risk exposure of alternatives• Identification of best risk owner“Soft” intangible benefits from the risk process include :• Improved communication• Development of a common understanding of project objectives• Enhancement of team spirit• Focused management attention on genuine threats• Facilitates appropriate risk-taking• Demonstrates professional approach to customersThe widespread use of project risk management suggests that people are implicitly convinced that it must deliver benefits. It is however difficult to prove unambiguously that benefits are being achieved. There is therefore a genuine need for a body of evidence to demonstrate the expected benefits of the risk process. Problems currently arise from the fact that existing evidence is either anecdotal (instead of providing hard measurable data) and confidential (accessible data is required, including both good news and bad). Also projects are unique (data requires normalising), and different between industries (evidence should be both generic and specific).In the absence of a coherent body of irrefutable evidence, the undoubted benefits that can accrue from effective management of risk must currently be taken on trust. Overcoming this will require generation of a body of evidence to support the use of formal project risk management, providing evidence that benefits can be expected and achieved, and convincing the sceptical or inexperienced that they should use project risk management.The intended audience of such a body of evidence would fall into several groups, each of which might seek different evidence, depending on their perspective on project success. Possible groups include the client/sponsor, project manager, project team and end user. For each group, the body of evidence should first define a “successful project” from their perspective, then consider whether/how risk management might promote “success” in these terms, then present evidence demonstrating the effect of risk management on the chosen parameters.CONCLUSIONThe short history of project risk management has been a success story to date, with widespread application across many industries, and development of a core best practice with a strong supporting infrastructure. Although project risk management has matured into a recognised discipline, it has not yet reached its peak and could still develop further.This paper has outlined several areas where the author believes that progress is required. In summary, adoption of the proposed agenda for development of project risk management will result in the following :• An accepted framework within which each organisation understands its current risk management capability and which defines a structured path for progression towards enhanced maturity of risk processes (via organisational benchmarking). • A set of risk management tools and techniques which are fully integrated with project and business processes, with the existence of uncertainty being recognised and accepted at all levels (via integration of risk management).• Improved analysis of the effects of risk on project and business performance, addressing its impact on issues wider than project time and cost (via increased depth of analysis and breadth of application).• Proper account being taken of human factors in the risk process, using assessment of risk attitudes to counter systematic bias and build risk-balanced teams (via behavioural aspects).• Agreement on the benefits that can be expected from implementation of a formal approach to project risk management, based on an objective and accessible body of evidence which justifies those benefits (via supporting evidence).It is argued that attention to these areas will ensure that project risk management continues to develop beyond the current situation. Project risk management must not remain static if it is to fulfil its potential as a significant contributor to project and business success. The areas outlined in this paper are therefore proposed as an agenda for development of project risk management in the short to medium term, producing an indispensable and effective management tool for the new millennium.REFERENCES1. UK MoD Risk Guidelines comprise the following :MOD(PE) - DPP(PM) (October 1992) Statement by CDP & CSA on RiskManagement in Defence Procurement (Ref. D/DPP(PM)/2/1/12)MOD(PE) - DPP(PM) (January 1992) Risk Management in DefenceProcurement (Ref. D/DPP(PM)/2/1/12)MOD(PE) - DPP(PM) (October 1992) Risk Identification Prompt List forDefence Procurement (Ref. D/DPP(PM)/2/1/12)MOD(PE) - DPP(PM) (June 1993) Risk Questionnaires for DefenceProcurement (Ref. D/DPP(PM)/2/1/12)Defence Committee Fifth Report (June 1988) The Procurement of MajorDefence Equipment (HMSO)2. CCTA,“PRINCE Project Evaluation”, HMSO, London, 1994, ISBN 0-11-330597-4.3. CCTA, “PRINCE2 : Project Management for Business”, HMSO, London,1996, ISBN 0-11-330685-7.4. British Standard BS6079 : 1996 “Guide to project management”, BritishStandards Institute, ISBN 0-580-25594-8, 19965. British Standard BS8444 : Part 3 : 1996 (IEC 300-3-9 : 1995) “RiskManagement : Part 3 – Guide to risk analysis of technological systems”,British Standards Institute, ISBN 0-580-26110-7, 19966. Norsk Standard NS 5814 “Krav til risikoanalyser”, NorgesStandardiseringsforbund (NSF), 1991.7. Australian/New Zealand Standard AS/NZS 4360:1995 “Risk management”,Standards Australia/Standards New Zealand, ISBN 0-7337-0147-7, 19958. National Standard of Canada CAN/CSA-Q850-97 “Risk management :Guideline for decision-makers”, Canadian Standards Association, ISSN 0317-5669, 19979. “Guidelines on risk issues”, The Engineering Council, London, ISBN 0-9516611-7-5, 199510. HM Treasury “Risk Guidance Note”, HMSO, London, June 1994.11. HM Treasury Central Unit on Procurement – CUP Guidance Number 41“Managing risk and contingency for works projects”, HMSO, London, 1993 12. Godfrey P.S. “Control of risk – A guide to the systematic management of riskfrom construction”, CIRIA, London, ISBN 0-86017-441-7, 199613. Institute of Risk Management, Lloyd’s Avenue House, 6 Lloyd’s Avenue,London EC3N 3AX, UK, tel +44(0)171.709.980814. Association for Project Management, 150 West Wycombe Road, HighWycombe, Bucks HP12 3AE, UK, tel +44(0)1494.44009015. Project Management Institute, 130 South State Road, Upper Darby, PA 19082,USA, tel +001.610.734.333016. Simon P.W., Hillson D.A. & Newland K.E. (eds.) “Project Risk Analysis &Management Guide”, APM Group, High Wycombe, Bucks UK, ISBN 0-9531590-0-0, 199717. Chapman C.B. & Ward S.C. “Project risk management : processes, techniquesand insights”, John Wiley, Chichester, Sussex UK, ISBN 0-471-95804-2,199718. “A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge”, ProjectManagement Institute, Upper Darby USA, ISBN 1-880410-12-5, 199619. “Continuous Risk Management Guidebook”, Software Engineering Institute,Carnegie Mellon University, USA, 199620. Hillson D.A. (1997) “Towards a Risk Maturity Model”, Int J Project &Business Risk Mgt, 1 (1), 35-4521. “The Risk Maturity Model was a concept of, and was originally developed by,HVR Consulting Services Limited in 1997. All rights in the Risk MaturityModel belong to HVR Consulting Services Limited.”22. “Project Management Capability Maturity Model” project, PMI StandardsCommittee, Project Management Institute, 130 South State Road, UpperDarby, PA 19082, USA. Details from Marge Combe,be@.23. 11th Software Engineering Process Group Conference : SEPG99, Atlanta, 8-11March 1999 (themes include risk capability maturity models)24. Stader J. (1997) “An intelligent system for bid management”, Int J Project &Business Risk Mgt, 1 (3), 299-31425. Brander J. & Dawe M. (1997) “Use of constraint reasoning to integrate riskanalysis with project planning”, Int J Project & Business Risk Mgt, 1 (4),417-43226. CCTA, “Management of Programme Risk”, HMSO, London, ISBN 0-11-330672-5, 199527. “Financial Reporting of Risk – Proposals for a statement of business risk”,The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England & Wales, 199828. Oldfield A. & Ocock M. (1997) “Managing project risks : the relevance ofhuman factors”, Int J Project & Business Risk Mgt, 1 (2), 99-10929. Kahneman D., Slovic P. & Tversky A. (eds.) “Judgement under uncertainty :Heuristics and biases”, CUP, Cambridge, 198230. Research by M Greenwood (personal communication, 1997), BurroughsHouse Associates, Middlezoy, Somerset, UK.。

成功的项目管理(Successful Project Management)——项目管理方法、工具与实践若干年前,管理大师汤姆·彼得斯说:全世界有50%的白领工作是由项目管理完成;若干月前,管理大师汤姆·彼得斯说:全世界有100%的白领工作将由项目管理完成。

导言:21世纪是项目管理的世纪。

项目管理涉及的范围日益广泛,研发一项新产品、开发新的软件、企业信息化建设、完成一项工程……所有这些都是项目。

越来越多的中国企业、跨国企业引入项目管理,把其作为提高企业运作效率的解决方案,诸如微软,三星,沙特阿美,IBM,HP,麦肯锡,贝尔-阿尔卡特,中国的华为,天士力制药,宝钢国际等大型公司在企业内全面推行项目化管理,把项目分解成企业项目,部门项目和小组项目。

另外,像世界银行是把每一笔贷款作为一个项目来管理的,摩托罗拉在20世纪90年代中就启动了一个旨在改善其项目管理能力的计划,在其内部广泛推行项目管理方法。

全球的1/5的国民生产总值(GDP)都用在各种项目上,在这个竞争激烈的世界上,至关重要的是,组织能够成功的采取新措施,推出新产品,倡导新理念,并提高满足客户需求的能力。

所有这些都必须依靠项目来实现。

本课程以美国项目管理协会(PMI)的知识体系框架为基础,结合中国国情和CMC咨询公司多位项目管理顾问的多年实践经验,通过系统的学习与互动研讨,掌握项目管理的基本原理和技巧,透过实践领悟精髓,提升个人的项目管理能力和企业竞争力。

在2天的课堂中,结合学员所在企业的实际案例,Step by Step的进行剖析和演练,彻底掌握项目管理的工具和方法。

推进企业或组织的决策水平、执行能力、市场应变能力、资源配置效率、客户管理能力、综合业务能力等,为企业或组织引入崭新的管理途径和实战方法,使组织及个人高屋建瓴地驾驭项目管理的先进理念和实践应用。

联系人:顾小姐课程对象:项目经理及工程师、部门经理、项目助理、业务与市场经理、项目工程师;研发、生产、采购、人事行政、财务、大客户销售、咨询顾问、项目团队成员;生产计划员,项目专员等,工作中面临复杂的工作任务和挑战,以及需要学习并掌握项目管理知识的职场专业人士。