Computerized Corpora and the Future of Translation Studies

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:122.57 KB

- 文档页数:9

The computer is an indispensable tool in modern society,playing a crucial role in various fields such as education,business,and entertainment.Here is an introduction to computers in English,followed by its translation into Chinese.Computers:A Modern MarvelComputers are the backbone of the digital age,offering unparalleled capabilities in processing information and facilitating communication.They have revolutionized the way we live,work,and learn.From the early days of roomsized machines to the sleek laptops and smartphones we use today,the evolution of computers has been nothing short of remarkable.The Dawn of ComputingThe first computers were massive,occupying entire rooms and requiring teams of people to operate.They were primarily used for military purposes and complex calculations. However,as technology advanced,computers became smaller,more powerful,and accessible to a wider audience.The Personal Computer RevolutionThe introduction of the personal computer PC in the1980s marked a significant shift in the computing landscape.PCs made computing accessible to the masses,allowing individuals and businesses to harness the power of technology for a variety of tasks.The graphical user interface GUI,pioneered by companies like Apple and Microsoft,made computers more userfriendly and intuitive.The Internet and BeyondThe advent of the internet in the1990s further transformed the role of computers.It connected computers around the world,enabling instant communication and access to vast amounts of information.The World Wide Web became the platform for sharing knowledge,entertainment,and commerce.Modern Computing DevicesToday,computers come in various forms,from traditional desktops and laptops to tablets and smartphones.They are equipped with powerful processors,highspeed internet access,and advanced software that can perform complex tasks with ease.Cloud computing has also emerged as a popular method for storing and accessing data remotely.The Future of ComputingAs we look to the future,computers are expected to become even more integrated into our daily lives.Advancements in artificial intelligence,machine learning,and quantum computing promise to unlock new possibilities and further blur the line between human and machine.计算机:现代奇迹计算机是数字时代的支柱,提供了无与伦比的信息处理能力和促进沟通的能力。

电子商务的未来英语作文In the past decade, the world has witnessed an unprecedented surge in the development and adoption of e-commerce. The advent of the internet and advancements in technology have fundamentally changed the way businesses operate and how consumers shop. As we look to the future, it is clear that e-commerce will continue to evolve, shaping the global economy in profound ways. This essay explores the future of e-commerce, examining the trends, technological advancements, and potential challenges that lie ahead.E-commerce has come a long way from its humble beginnings. Initially, it was primarily about online retail stores selling goods to consumers. Today, it encompasses a wide range of activities, including online banking, digital wallets, virtual marketplaces, and even augmented reality shopping experiences. The continuous innovation in e-commerceplatforms has made it easier for businesses to reach a global audience and for consumers to access products and services from anywhere in the world.One of the most significant drivers of e-commerce growth is technology. Emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and blockchain are revolutionizing the way e-commerce operates. AI and machine learning, for instance, are being used to enhance customer experience through personalized recommendations and efficient customer service via chatbots. Blockchain technology offers secure and transparent transactions, which is crucial for building consumer trust in online transactions.Furthermore, the rise of 5G technology promises faster and more reliable internet connections, which will enable more seamless and immersive shopping experiences. Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are also expected to play a pivotal role in the future of e-commerce. These technologiescan provide consumers with virtual try-on experiences for clothing, accessories, and even furniture, reducing the uncertainty and hesitation often associated with online shopping.Consumer behavior is constantly evolving, and e-commerce must adapt to meet these changes. The modern consumer is more informed, tech-savvy, and demands convenience and speed. As a result, there is a growing preference for mobile shopping, which is driving the development of mobile-friendly websites and apps. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the shift towards online shopping, with many consumers now preferring to shop from the safety and comfort of their homes.Social media platforms are also playing a significant role in shaping consumer behavior. Platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok have integrated shopping features, allowing users to make purchases directly through the app. This trend, known associal commerce, is expected to grow, with influencers and social media personalities driving sales through their endorsements and recommendations.As awareness of environmental and ethical issues grows, consumers are becoming more conscious of the impact of their purchasing decisions. E-commerce businesses are responding by adopting more sustainable practices, such as reducing packaging waste, using eco-friendly materials, and optimizing supply chains to reduce carbon footprints. Additionally, there is a growing demand for transparency in sourcing and manufacturing processes, with consumers favoring brands that adhere to ethical standards and fair trade practices.The future of e-commerce will likely see a greater emphasis on sustainability, with businesses integrating eco-friendly initiatives into their operations. This shift not only appeals to environmentally conscious consumers but also helps companies differentiate themselves in a competitive market.Despite the promising future, e-commerce faces several challenges that need to be addressed. Cybersecurity remains a major concern, with the increasing number of online transactions making e-commerce platforms a target for cyberattacks. Ensuring robust security measures and protecting consumer data will be paramount to maintaining trust and confidence in e-commerce.Another challenge is the digital divide, which refers to the gap between those who have access to the internet and digital technologies and those who do not. For e-commerce to reach its full potential, efforts must be made to bridge this divide, ensuring that people in developing regions and underserved communities have access to the necessary infrastructure and resources.Additionally, the rapid pace of technological advancements can be both a blessing and a curse. While it drives innovation and growth, it also requires businesses tocontinuously adapt and invest in new technologies, which can be resource-intensive. Staying ahead of the curve will be crucial for businesses to remain competitive in the ever-evolving e-commerce landscape.The future of e-commerce is undoubtedly bright, with technological advancements and changing consumer behaviors driving its growth. As businesses continue to innovate and adapt to new trends, e-commerce will become even more integral to the global economy. However, addressing challenges such as cybersecurity, the digital divide, and sustainability will be crucial to ensuring a secure, inclusive, and sustainable future for e-commerce.In conclusion, the evolution of e-commerce is a testament to the transformative power of technology. As we look ahead, the possibilities for e-commerce are limitless, offering exciting opportunities for businesses and consumers alike. The key tounlocking these opportunities lies in embracing innovation, fostering trust, and prioritizing ethical and sustainable practices.。

Is Big Tech Losing Its Appeal大型科技公司对应届毕业生还有吸引力吗Pizza stations, gyms, headquarters designed by world-famous architects, and the promise of a brilliant career that also has the potential to solve world problems. ____1____ But is its status starting to change?Unfortunately, this is indeed the case. According to a CNBC report based on interviews with former Facebook recruiters (招聘专员), the company has been struggling to win over graduates following the Cambridge Analytica (剑桥分析公司) scandal in 2018. Among top schools, Facebook’s acceptance rate for full-time positions on offer to new graduates has fallen from an average of 85 percent, during the 2017-2018 school year, to 35 percent as of December 2018. The report cited ethical (道德的) and political concerns among candidates, as well as the relevance of Facebook as a lead brand among young people.It is well established that those aged between 18 and 24 are looking for more purpose in their work. “Purpose” can be defined in a few ways, but it often comes down to having high-level vision and a sense of personal impact. ____2____ If tech workers don’t want to feel likea cog (轮齿) in an enormous machine, they no longer need to. There are many alternatives available.____3____According to , their average salary globally is $135,000. However, the culture of long hours (probably fueled by those free pizzas) has lost its appeal among the younger generation as they seek a better work-life balance. For those who stay in Big Tech, it is not hard to realize that the cost of living in big cities increasingly cancels out much of the amazing salary on offer.____4____ There is a monoculture (单一文化社会) in Silicon Valley (硅谷). Employees often do not interact with anyone until they get to the office. They do not experience the real world and yet they are supposed to — in Facebook’s case — be serving a community of 2.5 billion. I find that really troubling. They need to be given more time and resources to think about the impact their products may have on society.Despite these problems, the vast majority of tech workers still believe technology is a force for good. They could be a key force that helps to form the much-needed change of Big Tech companies. Empowering (赋权) them with “positive dissent (异议)” could be the way to keep them. ____5____(选自Economist)A. Big Tech is not evil; it just needs help.B. Big Tech might be concerned about government fines and PR emergencies, but its biggest problem could be failing to recruit and keep talented staff.C. For a long time, working in Big Tech was the dream for many young people.D. Tech workers are seeing the connection between all these things — misinformation, bias and inequality — and wanting to do something about them.E. The lack of diversity in Big Tech is also an issue.F. With huge employee bases, both these things get diluted (稀释) in Big Tech.G. Tech workers in Big Tech are still well-paid.译文:披萨站,体育馆,由世界著名建筑师设计的总部,以及其辉煌职业的承诺,也有可能解决世界问题。

计算机技术的未来英语作文英文回答:The future of computer technology holds endless possibilities and is poised to revolutionize variousaspects of our lives, from the way we work, learn, communicate, and interact with the world around us. Advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), quantum computing, virtual reality (VR), and the Internet of Things (IoT) are shaping the future of computing, offering unprecedented opportunities and challenges.One of the most significant trends shaping the futureof computer technology is the rapid advancement of AI. AI-powered systems have already demonstrated remarkable capabilities in areas such as natural language processing, image and speech recognition, and predictive analytics. As AI continues to develop, we can expect to see even more sophisticated applications in industries such as healthcare, finance, and transportation. For example, AI-powereddiagnostic tools can assist doctors in identifying diseases earlier and more accurately, leading to improved patient outcomes.Another transformative technology that is shaping the future of computing is quantum computing. Unliketraditional computers that rely on bits representing 0s or 1s, quantum computers utilize qubits that can exist in a superposition of both states simultaneously. This unique property enables quantum computers to perform complex calculations exponentially faster than classical computers, opening up new possibilities for scientific research, drug discovery, and materials science.Virtual reality (VR) is also poised to have a profound impact on the future of computer technology. VR headsets immerse users in virtual environments, creating realistic and interactive experiences. This technology has the potential to revolutionize industries such as gaming, entertainment, and education. For instance, VR can enable students to experience historical events or explore distant lands without leaving the classroom.The Internet of Things (IoT) is another key technology that is shaping the future of computing. IoT devices connect everyday objects to the internet, enabling them to collect and share data. This vast network of connected devices has the potential to transform industries such as manufacturing, healthcare, and agriculture. For example, IoT sensors can monitor equipment in factories to predict maintenance needs, reducing downtime and improving efficiency.In addition to these major trends, other emerging technologies such as blockchain, 5G networks, and edge computing are also expected to play significant roles in shaping the future of computer technology. Blockchain provides a secure and transparent way to record and share data, making it ideal for applications such as digital identity and supply chain management. 5G networks offer ultra-fast wireless connectivity, enabling real-time applications and immersive experiences. Edge computing brings data processing and storage closer to the devices that need it, reducing latency and improving performancefor applications such as autonomous vehicles and smart cities.The future of computer technology is充滿无限可能,并将彻底改变我们生活的各个方面,从我们工作、学习、交流和与周围世界互动的方式。

计算机技术的未来英语作文The Future of Computing Technology.Computing technology has come a long way since its humble beginnings. In the early days, computers were large, expensive, and only accessible to a select few. Today, computers are ubiquitous. They are used in every aspect of our lives, from work and school to entertainment and communication.As we look to the future, it is clear that computing technology will continue to evolve at a rapid pace. Here are some of the key trends that we can expect to see in the years to come:Increased connectivity: Computers will become increasingly connected to each other and to the internet. This will allow us to share information and collaborate with others more easily than ever before.Artificial intelligence (AI): AI will become more sophisticated and pervasive. AI-powered systems will be able to learn from data, make decisions, and solve problems on their own.Quantum computing: Quantum computing willrevolutionize the way we process information. Quantum computers will be able to solve problems that are currently impossible for classical computers to solve.Edge computing: Edge computing will bring computing power closer to the devices that we use. This will reduce latency and improve performance for applications that require real-time data processing.Virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR): VR and AR will become more immersive and realistic. VR/AR headsets will allow us to experience virtual worlds and interact with digital objects as if they were real.These are just a few of the key trends that we can expect to see in the future of computing technology. Asthese trends continue to develop, we can expect to see even more transformative changes in the way we live, work, and interact with the world around us.The impact of computing technology on society.Computing technology has had a profound impact on society. Computers have made it possible to automate tasks, communicate with people around the world, and access information and entertainment on demand.As computing technology continues to evolve, we can expect to see even more transformative changes in the waywe live. For example, AI-powered systems could help us to solve some of the world's most pressing problems, such as climate change and poverty. VR/AR technology could revolutionize the way we learn and experience entertainment. And edge computing could make it possible for us to havereal-time access to data and services, regardless of where we are.Of course, there are also some potential risksassociated with the advancement of computing technology. For example, AI-powered systems could be used to develop autonomous weapons or to create surveillance systems that could侵犯 our privacy. It is important to be aware of these risks and to take steps to mitigate them.Overall, the future of computing technology is bright. As computing technology continues to evolve, we can expect to see even more transformative changes in the way we live, work, and interact with the world around us. It is important to be aware of both the potential benefits and risks of these changes, so that we can shape the future of computing technology in a way that benefits all of society.Conclusion.Computing technology is rapidly evolving, and it is having a profound impact on society. As we look to the future, we can expect to see even more transformative changes in the way we live, work, and interact with the world around us. It is important to be aware of both the potential benefits and risks of these changes, so that wecan shape the future of computing technology in a way that benefits all of society.。

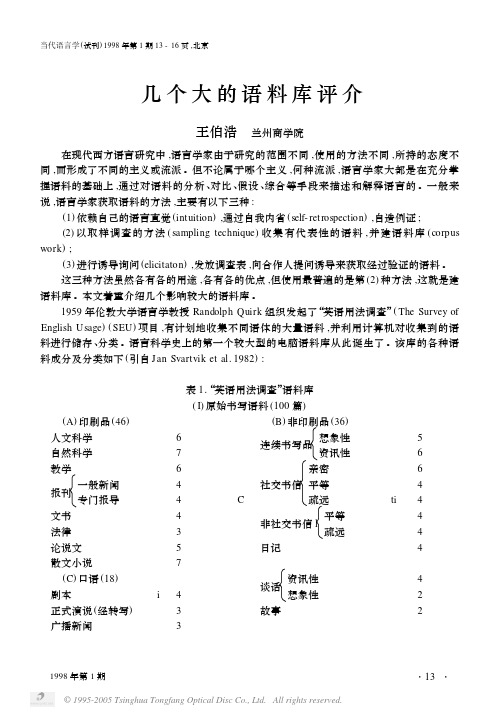

《当代语言学》:往届同学作业是搜集利用语料库开展汉语教学与研究有关的文献,实际上他搜集的那些文章里还有专谈语料库的,那同学的标注不是很全,有的地方是空着的。

我开始看不明白,想如果是有关的文章为什么不标注呢?后来我对这本杂志有所了解后才发现这本杂志关于汉语教学研究的不多,可能他觉得东西少,就加了一点语料库的进去。

所以我重新梳理了一下这本杂志:首先我是大致地了解一下这本杂志的办刊情况和内容概况,我从CNKI上能查到的最早一期是1962年的第07期,CNKI上面说它是62年创刊,实际它是1961年创刊的,前面的6期可能由于“文革”或者别的什么原因没有找到,它是由中国社会科学院语言研究所创办的,前身叫《语言学资料》,是《中国语文》的附属刊物,是供内部参考的学术刊物。

现在仍然是中国社会科学院语言研究所主办出版,但已经是一本国际性学术期刊。

从它的一些篇目索引看出,这个杂志主要是介绍国外先进语言学理论,我发现当时里面有很多前苏联语言学家的文章,刊登的文章反映当时语言学界的前沿动态,以外论译介、书刊评介、专题文摘、国内动态、国外动态的栏目形式,这种倾向一直延续至今,现在除了引进国外先进语言学理论,推进当代语言学的理论探索与研究,还强调特别要推进“洋为中用”的实证性研究,我发现里面增加了中国语文研究这个栏目,但它不登有关外语教学和纯外国语言研究的文章,它的书刊评介着重介绍国外最新出版的语言学著作,国内出版的不在此刊的评介之列。

这个杂志中间有过三次更名,《语言学资料》66年出了两期后,一度停办,中断出版十多年,是由于我国当时正处于“文革”时期,直到1978年复刊,更名为《语言学动态》,仍然是内部资料。

到1980年更名为《国外语言学》(试刊)出版,开始转为对外的期刊了,一直到98年,随着国际学术交流变得越来越频繁和方便,这本刊物更名为现在的《当代语言学》,自80年更名为《国外语言学》正式出版后改为季刊,之前的内部资料性质的都是双月刊。

科技视界Science &Technology VisionScience &Technology Vision 科技视界随着计算机与通信技术的飞速发展,计算机通信得到广泛应用,硬件技术可谓是日新月异,其总体趋势向着高集成度、高稳定性、高速和高性价比方向发展。

而红外无线耳机通信系统装置则是目前应用较为广泛的通信形式。

由于感应式无线耳机的发射电路必须固定安装在房间的墙壁或天花板上,故无法在室外使用,这是感应式无线耳机的主要缺点。

而红外无线耳机则不然,由于它的信号发射采用小巧的红外发射电路,既可在室内用于电化教学、家庭电视和音响设备的音频信号无线接收,也能在户外使用便携式录音机、CD、VCD 及MP3时,方便地往掉耳机线,实现名副实在的无线“随身听”。

红外无线耳机在使用时将插头XP 插进电视机、收录机的耳机插座内,音频信号通过XP 经电容Cl 耦合、三极管VTl 放大,再由红外发射二极管VDl 和VD2向外发射载有音频电波的红外线。

电路装成后适当调节偏置电阻R2,使流过VDl 和VD2的静态电流为l0mA 即可。

在无线耳机的接收电路中,红外接收管VD3~VD5接收到发射电路发出的红外线信号后,将其转换为音频信号,再由三极管VT2放大送进集成运放ICl 作功率放大,最后由耳机BE 输出。

电路中使用3只红外接收管是为了能全方位接收信号。

调试时,先用手触摸红外接收管的正极,调节电阻R4、R5使耳机BE 输出的交流声最响,然后再接通发射电路,适当调节电视机或收录机的音量大小,直到耳机传出的声音大且清楚为止。

将红外(IR)光作为无线通信媒介也非常流行。

我们经常可以在手机、PDA 及其它消费类(CE)设备看到IR 端口。

据悉,目前带有IR 端口的设备基数已达近10亿,同时,红外遥控是室内无线控制的通信标准。

尽管如此,传统的IR 解决方案对发射器和接收设备之间的视距和方向性有要求,这大大限制了其应用领域和对市场的吸引力。

未来电脑发展英语作文{z}Title: The Future of Computer DevelopmentIn recent years, the rapid advancement of technology has significantly influenced various sectors, and the computer industry is no puters have become an integral part of our daily lives, from simple tasks like checking emails to complex activities like running advanced simulations.As we continue to delve into the future, it is evident that computers will experience substantial growth and transformation.This essay will explore the potential future developments in computer technology.Firstly, one of the most promising areas of computer development is the increase in computational power.As technology progresses, computers are becoming faster and more efficient, enabling them to handle more complex tasks.This increase in computational power is crucial for fields such as artificial intelligence, big data analysis, and scientific research, where processing large amounts of data quickly is essential.In the coming years, we can expect computers to perform calculations at speeds that were once deemed impossible, pushing the boundaries of what we can achieve with technology.Secondly, computers are becoming more compact and portable.As technology advances, the size of computer components is reducing, allowing for the creation of smaller and more portable devices.This trendis evident in the proliferation of smartphones, tablets, and wearable devices.In the future, we can anticipate even smaller and more powerful computers that can be seamlessly integrated into our everyday lives.For instance, we may see computers embedded in clothing, glasses, or even implanted within our bodies, providing us with constant access to information and enabling new levels of connectivity.Another significant development in computer technology is the rise of quantum computing.Quantum computing harnesses the principles of quantum mechanics to perform calculations at speeds far surpassing traditional computers.This potential breakthrough in computing power could revolutionize fields such as cryptography, drug discovery, and climate modeling.While quantum computing is still in its infancy, recent advancements suggest that we are moving closer to practical applications, which will undoubtedly shape the future of computer development.Furthermore, the future of computers also lies in increased collaboration with artificial intelligence (AI).AI refers to the ability of machines to perform tasks that would typically require human intelligence, such as speech recognition and decision-making.As computers become more powerful and AI algorithms improve, we can expect a seamless integration of AI into computer systems.This collaboration will enable computers to perform complex tasks withminimal human intervention, leading to increased efficiency and new possibilities in areas like healthcare, transportation, and education.In conclusion, the future of computer development is promising and wide-ranging.The increase in computational power, the trend towards smaller and more portable devices, the rise of quantum computing, and the integration of artificial intelligence are just a few aspects that contribute to this promising future.As technology continues to evolve, computers will become an even more indispensable part of our lives, driving innovation and transforming various sectors.It is an exciting time to be witnessing these advancements, and we can only imagine the possibilities that the future holds for computer technology.。

COMPUTERIZED CORPORA AND THEFUTURE OF TRANSLATION STUDIESMARIA TYMOCZKOUniversity of Massachusetts, Amherst, USARésuméCet article traite de la «centralité» des études basées sur le corpus par rapport au domaine entier de la traductologie. L'auteur met le lecteur en garde contre la tentation de faire de la rigueur scientifique une fin en soi par des études quantitatives vides et inutiles.AbstractThis article provides a discussion of the centrality of corpus-based studies within the entire discipline of translation studies. The author warns against the possible danger of pursu-ing scientific rigour as an end in itself through empty and unnecessary quantitative investiga-tions.The information age has brought an explosion in the quantity and quality of information we are expected to master. This, along with the development of electronic modes for storing, retrieving, and manipulating that information, means that any disci-pline wishing to sustain itself in the twenty-first century must adapt its content and methods. Corpus translation studies is central to the way that Translation Studies as a discipline will remain vital and move forward. The essays collected in this volume show that corpus translation studies has the characteristics typical of contemporary emerging modes of knowing and investigating. Corpus translation studies enable us, for example, to encode in compact and efficient forms, to access and interrogate vast quantities of data — more data than any single human being could ever manage to gather or examine in a productive lifetime without electronic assistance. Moreover, the approach allows for and promotes the construction of information fields that suit a new international, multicultural intellectualism, providing for the inclusion of data from small and large populations, from minority as well as majority languages and cultures. Translation cor-pora make it possible for decentralized, multilocal investigations to proceed thanks to virtually instantaneous access to shared primary materials. Corpora in translation stud-ies lend themselves to joint intellectual endeavors unimpeded by time or space, facili-tated by intercommunication across the globe. They permit the reversibility of perspective, the decentering of power. And like large databases in the sciences, corpora will become a legacy of the present to the future, enabling future research to build upon that of the present. Thus, corpus translation studies change in a qualitative as well as a quantitative way both the content and the methods of the discipline of Translation Studies, in a way that fits with the modes of the information age.1Corpus translation studies (CTS) has emerged at a critical time in the discipline of Translation Studies. Growing out of corpus linguistics and thus inherently having an allegiance to linguistic approaches to translation, CTS at the same time marks a turn away from prescriptive approaches to translation toward descriptive approaches, approaches developed by scholars over the last thirty years, notably by polysystems the-Meta, XLIII, 4, 19982Meta, XLIII, 4, 1998 orists such as Itamar Even-Zohar, Gideon Toury, and André Lefevere. CTS focuses on both the process of translation and the product of translation (cf. Holmes 1988: 67; Bassnett 1991: 7), and takes into account the smallest details of the text chosen by the individual translator, as well as the largest cultural patterns both internal and external to the text. It builds upon the studies of scholars working in the descriptive approach to Translation Studies, and those of scholars who have worked with corpora themselves, albeit corpora that have been manually assembled, examined, and analyzed.2 The essays collected here illustrate that, although the materials of corpora are based upon the language medium of translations, interrogation of corpora can nonetheless serve to address not simply questions of language or linguistics, but also questions of culture, ideology, and literary criticism. Modes of interrogation — as well as care in the encod-ing of metatextual information about translations and texts — allow researchers to move from text-based questions to context-based questions. The flexibility and adapt-ability of corpora, as well as the openendedness of the construction of corpora underlie the strength of the approach.Inevitably, as is to be expected, the debates of Translation Studies as a whole are mirrored in CTS. For some CTS writers, the notion of "a tertium comparationis" is central, for others the concept has implicitly been superseded (cf. Snell-Hornby 1990). Some writers see norms as one of the most pressing factors to be investigated, while for others the question of norms plays little or no role. Equivalence — a concept that to Jacobson (1959: 233) was "the cardinal problem of language and the pivotal concern of linguistics", but that more recently has fallen into discredit (Snell-Hornby 1988: 13; Van den Broeck 1978) — is still an important part of their discourse for some CTS scholars. The relationship of interpretation to Translation Studies, both theoretically and pragmatically, is addressed within CTS as it is elsewhere in the discipline. The types of literary questions addressed by the "manipulation" school of Translation Stud-ies (see Hermans 1985; cf. Snell-Hornby 1988: 22) motivate some CTS investigations, while literature as such is excluded from other corpora altogether and hence from research done with those corpora. For some CTS investigations, literary texts are seen as optimal, offering the most comprehensive information, while for others literary texts are seen as unrepresentative of natural language. The tendency toward segmentation of pedagogic, pragmatic, and theoretical studies is found in CTS, as it is in Translation Studies and intellectual endeavors altogether.One of the most important debates in intellectual domains has to do with the search for laws, both practical and theoretical. This debate is also conducted in Trans-lation Studies and mirrored in CTS. The interest in laws — promoted in Translation Studies by Even-Zohar and Toury, among others — follows the tradition of empirical research, behind which lies the presupposition of Western rationalism that science should be in the business of discovering natural laws and that "scientific" results have more value than others. In part a legacy of positivism, these predispositions are inti-mately connected with a tendency to polarize objectivity vs. subjectivity and privilege the former. A number of CTS scholars promote and justify corpus-based approaches on the grounds that such studies will uncover and establish universal laws of translation.By contrast, throughout the twentieth century the foundations of such objectivist research were repeatedly called into question. From the work of Einstein and Gödel and Heisenberg in physics and mathematics during the earliest decades of the twentieth century, to mid-century reconsiderations of objectivist premises about literature and history, to still later explorations of subjectivity in the social sciences, modern thought has increasingly come to understand the way that the perspective of the observer or the researcher is encoded in every investigation and impinges upon the object and theCOMPUTERIZED CORPORA AND THE FUTURE OF TRANSLATION STUDIES3 results of study. Such challenges to empiricist claims about objectivity and such asser-tions of subjectivity — and the large intellectual trajectory behind them — are echoed in some of the approaches represented in this collection and are germane to the devel-opment of CTS.In my view, the value of corpora in translation and of a CTS approach to transla-tion theory and practice does not rest on the claim to "objectivity" and the somewhat worn philosophical tradition claims of this type presuppose. Indeed, as a number of the authors here remind us, behind the establishment of corpora, as behind the design of any experiment or research program or survey, lie intuition and human judgement. Corpora in translation studies are products of human minds, of actual human beings, and, thus, inevitably reflect the views, presuppositions, and limitations of those human beings. Moreover, the scholars designing studies utilizing corpora are people operating in a particular time and place, working within a specific ideological and intellectual context. Thus, as with any scientific or humanistic area of research, the questions asked in CTS will inevitably determine the results obtained and the structure of the databases will determine what conclusions can be drawn. In that sense then, corpora are again to be seen as products of human sensibility, connected with human interests and self-interests.All the more reason, therefore, to consider the objects of study, the data gathered in the databases, and the parameters defining the corpora themselves very carefully. Central to this concern is the definition of translation, as Sandra Halverson argues. The nature and definition of the category "translation" have been notoriously contentious within the discourses of translation theory and practice. One man's translation is another man's adaptation. The favorite translations of one era are repudiated altogether by another. Like the category game discussed by Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Inves-tigations, there is no simple core identity for the cluster of objects identified as transla-tions by the many societies of human time and space. Rather, translations like games form a category linked by many partial and overlapping "family resemblances", as Wit-tgenstein called such commonalities. Ultimately the inability to define translation within bounded and finite characteristics and still include in the definition all the objects that human societies have identified as translations3 led Toury to define transla-tion in a pragmatic way as "any target language text which is presented or regarded as such within the target system itself, on whatever grounds" (Toury 1982: 27; cf. Toury 1980: 14, 37, 43-45). The family resemblances linking translations, like those linking games, have depended on the manifold factors of human culture, including, for exam-ple, characteristics of the culture's language, the conditions of "text" production, the role (if any) of literacy, the material culture, economics, social customs, social hierar-chies, values, and so forth. In the case of translation, moreover, the processes and prod-ucts of translation will be correlated not simply with the conditions of one culture, but with those of at least two cultures in interface. It is the very variety of human cultures that leads to the variety of translations and games, and it is that variety that prevents us both pragmatically and theoretically from drawing a neat line, as in classical set theory, around the category translation.4Although the theory of prototypes may ultimately offer some help in understand-ing how human beings learn and recognize and remember categories, including cluster concepts such as those of game and translation linked by loose family resemblances, prototypes do not necessarily offer a solution to the theoretical problem of constructing corpora that can be interrogated to reveal translation laws, should a scholar undertake such an exercise. Contrary to Halverson, I take the view that prototypes — including the proposed prototype of the professional translator5 — are themselves culturally4Meta, XLIII, 4, 1998 defined and culture bound, rather than universal. As Eleanor Rosch, the pioneer in prototype research, specifically stipulates, the theory of prototypes is intended to address issues in categorization that "have to do with explaining the categories found ina culture and coded by the language of that culture at a particular point in time" (1978:28); moreover, she acknowledges that "many categories may be culturally relative" (1975: 193). Thus, a prototype is hardly the point of departure for a search for general or universal laws of translation, for one would then immediately have to ask compro-mising questions about the results. For example, what language, what place, and what time were privileged in the selection of the prototype? Our own? If so, we consign our theoretical work to hopeless ethnocentrism and so doom it from the outset.To take as an analogue the well-discussed category chair, although we might dis-cover on the basis of research done with contemporary American subjects that the pro-totype of chair is a wooden, four-legged desk chair, the modern prototype is not necessarily a guide to the prototypical chair of other times and other cultures. In the case of chair, for example, there is good reason to believe that in the Renaissance and earlier, the prototypical chair would have been very different from the configuration of the modern prototype. In view of material evidence from the period, the prototype would perhaps have been a three-legged apurtenance, with a triangular seat and a rela-tively small back, chairs such as are common from the Renaissance period and earlier. Four-legged chairs are only practical if floors are level, whereas three-legged chairs, like three-legged stools, are more useful, more common, and, thus, presumably, more prototypical in cultures where floors are made of mud or uneven paving stones, as floors were in most houses in pre-modern conditions. Indeed such three-legged stools and chairs — if chairs and stools are used at all — continue to be the norm (and, hence, probably the prototype) in most peasant cultures today.The problems of beginning with a prototype in a search for general laws governing a cluster concept like translation are even more complex than those posed by implicit ethnocentrism. In the case of the would-be prototype of the professional translator sug-gested by Halverson, for example, we might go on to ask how one defines or picks out a professional translator now, leaving aside the question of the past or other cultures. Is a professional translator a translator trained in a translation school or program? (Even if that person never works as a translator or never is paid for translation?) At what point does the non-professional student translator make the transition to professional? (If a student translator publishes a translation, is that piece by a professional?) Or is a pro-fessional translator a translator whose work has been published or otherwise remuner-ated — hence an a posteriori determination which will include in many cases amateur translators who have "made good" or "become successful"? If one could resolve ques-tions such as these to the satisfaction of all, the question would still remain as to when the prototypical translator is translating prototypically, i.e. under what conditions pro-fessional translation is deemed to exist or to have taken place. Thus, are all translations of a professional translator prototypical, or only those produced in some stipulated professional context? Moreover, are all types of texts translated by a professional trans-lator prototypical, or only a limited subset? And so forth. The recursive nature of the stipulation required for defining a prototype in the case of the concept like translation illustrates the difficulty that follows from using prototypes as a foundation for the search for general laws of translation.Such issues can also be illustrated by questions related to Wittgenstein's category of game. What is the prototype of game in the modern period? The prototype of an abstract cluster concept like game is much harder to establish than that of a material category like chair.6 There may in fact not be any example of game that functions as aCOMPUTERIZED CORPORA AND THE FUTURE OF TRANSLATION STUDIES5 prototype for an entire culture as complex and differentiated as contemporary Western cultures are. It may be that there are several competing prototypes of game, each partic-ular to a specific subculture, for example, football, tennis, cards, video, and so forth. And again, as with categories like chair, a conceptual category like game or translation also changes through time. One might surmise, for example, on the basis of textual, artistic, and archaelogical evidence, that the prototypical game for many people in medieval France was dice gaming — a pastime that is currently unlikely to be prototyp-ical of game for very many people, if for anyone, in Europe or America. And once more the problem of establishing a prototype becomes recursive, for even if one could make allowances in research for multiple as well as ethnically decentered prototypes — say dice gaming as the medieval European prototype of game — what are the prototypes that are themselves in turn presupposed by the typical instance of game at any one cul-tural locus? In the case of the example under discussion, one should then ask, for instance, what is the prototype of dice. Almost invariably for a modern informant the term will suggest a pair of cubical objects (although other types of dice exist, as any player of Dungeons and Dragons can testify), while in medieval Europe oblong dice, made of bone and used in threes, were much more common and, thus, presumably more prototypical.These are some of the difficulties with basing the construction of translation cor-pora on a theory of prototypes. As Halverson proposes, translation corpora based on modern Western "prototypes" might be developed and interrogated so as to reveal gen-eral characteristics of contemporary translations done in circumstances and cultural settings congruent with the examples underlying the corpora. Such corpora will be enormously useful and valuable, but they will not yield general laws of translation applying to all times and all places and all languages. To discover general laws of trans-lation, if indeed such laws exist, a question that Wittgenstein's arguments about catego-ries should lead us to consider very seriously, at the very least what will be needed are corpora representing as many types of translations as are known from the whole of human history.7 It may be, however, that such a quest is a positivist chimera, the com-monalities so restricted for a category like translation that the effort is unlikely to pro-vide the field of Translation Studies with much information of lasting value or transferable worth and, therefore, would not be worth the effort.If the primary purpose of CTS is neither to be objective nor to uncover universal laws, what is the specific strength of descriptive studies of translation facilitated by computerized corpora that can be electronically searched and manipulated? Over and over again the essays collected in this volume speak to this question, offering many divergent and exciting new directions for Translation Studies. The multiple possibilities that can be foreseen even at this embryonic stage of CTS are welcome, suggesting that corpus translation studies will be an open rather than a convergent approach to the the-ory and practice of translation. One can project the construction of many different cor-pora for specialized, multifarious purposes, making room for the interests, inquiries, and perspectives of a diverse world.Comparison is always implicit or explicit in inquiries about translation, and there is often a tendency to focus on likeness rather than difference and to rest content with perceptions of similarity. Whether focused on linguistic or literary or cultural matters, comparative disciplines — among which Translation Studies takes its place (cf. Bassnett 1993) — all have a predilection for focusing on similarity or sameness, as Dwight Bolinger, writing about linguistic studies, observes (1977: 5):Always one's first impulse, on encountering two highly similar things, is to ignore their differences in order to get them into a system of relationships where they can be stored,6Meta, XLIII, 4, 1998 retrieved, and otherwise made manageable. The sin consists in stopping there. And also in creating an apparatus that depends on the signs of absolute equality and absolute inequality, and uses the latter only when the unlikeness that it represents is so gross that it bowls you over.This impulse, which partly drives the interest in laws of translation, could be a projection of the development of a narrow form of CTS, particularly at the beginning of the exploration of this approach to corpora of translations. Bolinger correctly sounds a cautionary note: like Translation Studies as a whole, CTS must find ways to move beyond systems of relationship that focus on likeness and to avoid being locked into a binary apparatus that acknowledges only perceptions of absolute equality and inequal-ity.One reason that CTS is likely to avoid the pitfall of fixation on similarity and remain open to difference, differentiation, and particularity, is the sheer variety in nat-ural languages themselves and the multiplicity of theoretical and practical conse-quences resulting from the manifold language pairings possible in translation. This "infinite variety", which CTS is more able to apprehend and include in its purview than traditional methods of Translation Studies, militates against universalist programs of research and universalist conclusions. From a positivist point of view, such variety and divergence might be seen in a negative light, but from most other perspectives, the potential of CTS to illuminate both similarity and difference and to investigate in a manageable form the particulars of language-specific phenomena of many different languages and cultures in translation constitutes the chief appeal of this new approach to Translation Studies. Particularly at this juncture of history, we need to know the spe-cifics of different languages in translation, the individual particularities of specific pair-ings of languages in translation exchanges, and the characteristics of translation as cultural interface at different times and places and under different cultural conditions. Such differences teach us as much as or more than commonalities of translation, and they contribute as much or more not only to our theoretical investigations of transla-tion phenomena but to the practical concerns of situating translation in a decentered, multicultural world.For a long time in the history of translation theory and practice, difference was perceived in a negative way, as a departure from fidelity, a sign of the loss inherent in the translation process. In very different ways, both Eugene Nida's school of "dynamic-equivalence" translation and more recent approaches to translation — from those of Philip Lewis (1985) to the feminist translation theorists (Bassnett 1992, 1993: ch. 7) to the Brazilian school promoting "cannibalism" (Vieira 1994) — have valorized differ-ence in translation. It is clear that CTS has the potential to be one means of challenging hegemonic, culture-bound views of texts, translations, and cultural transfer. It is a powerful tool for perceiving difference and for valorizing difference as well.What are the next steps in the development of corpus translation studies? As we have seen, there are many leading edges in this field, just as there are in the field of Translation Studies as a whole. Nonetheless, looking at the most exciting new work in Translation Studies, one notes certain common themes and common commitments. Thus, for example, there is an growing commitment to integrate linguistic approaches and cultural-studies approaches to translation, to explore their reciprocal relationship, thus turning away from the invidious competition and isolation that plagued these two branches of the discipline for some time (cf. Baker 1996). Second, the leading work in Translation Studies shows an ever more sophisticated awareness of the role of ideology as it affects text, context, and translation, and as it affects the theory, practice, and ped-agogy of translation as well. And, finally, as in other disciplines, the pioneering work inCOMPUTERIZED CORPORA AND THE FUTURE OF TRANSLATION STUDIES7 Translation Studies involves adapting modern technologies to the discipline's needs and purposes. The essays at hand illustrate that corpus translation studies is dead center on all of these developments, once again suggesting the leading role it will play in the discipline of Translation Studies in the coming decades.In building for the future, CTS must take care not to diminish itself, falling into the fetishistic search for quantification that plagues many "scientific studies" and makes them ridiculous, empty exercises. Researchers using CTS tools and methods must avoid the temptation to remain safe, exploiting corpora and powerful electronic capa-bilities merely to prove the obvious or give confirming quantification where none is really needed, in short, to engage in the type of exercise that after much expense of time and money ascertains what common sense knew anyway. As the dour Vermonter might put it, "Do bears sleep in the woods?" Researchers must take care to ask "the right questions": to pose questions and construct research programs that have as their goal substantive investigations that are worthy of the powerful means deployed by CTS.In building for the future, CTS must also recognize the imperatives and honour the claims of historicism. Within Translation Studies there have now been many case studies related to historical poetics, for example, amassing considerable data on the wide variation of the role of translation in culture and the range of the norms of transla-tion practice. The gains of such work must be incorporated into the design and con-struction of corpora. Researchers must of course avoid the obvious trap already discussed of being locked into the translation norms of the present, and of presuppos-ing such norms in the construction of corpora. But beyond that obvious weakness, ontological and epistemological commitments in the design of corpora must include dedication to the past and to other cultures as well.The development of corpora and CTS methods represents a long-term invest-ment for the field of Translation Studies. As we now set the foundation of a legacy that will come to fruition in the future, it is important to begin to envision the widest possi-ble range of corpora that can be established, the uses to which corpora can be put, of questions that can be asked solely of corpora, and of methods that can be utilized with corpora for both theoretical and practical results. From envisioning these things we must proceed to encourage their development and realization.Finally, CTS is once again an opportunity to reengage the theoretical and prag-matic branches of Translation Studies, branches which over and over again tend to dis-associate, developing slippage and even gulfs. One of the most encouraging aspects of the pioneering studies of CTS is the way that seemingly technical and theoretical inter-rogations come to have practical potential and immediate applicability, not only for the teaching of translation but for the work of the practising translator as well.Notes1. See T. Tymoczko (1979) for an example of the way that electronic capabilities change disciplines in a qualitative manner. The results of corpus translation studies may at times generate a scepticism similar to that which computer proofs initially raised among mathematicians.2. See for example the case studies in Even-Zohar (1990); Lefevere and Jackson (1982); and Hermans (1985). See also Brisset (1996).3. That is, to establish criteria that will individually be necessary and collectively be sufficient to pick out all translations and only translations.4. For a general discussion of the philosophical issues related to categories see Wittgenstein (1953); Rosch (1978); Gleitman, Armstrong, and Gleitman (1983); and Lakoff (1987).5. As a word of caution, one should note that a prototype is not defined by researchers a priori, but is derived from actual empirical research with actual subjects speaking a specific language. It is quite possible that research would show that a professional translator is not prototypical of the concept translator to most speakers of English.。