霍布斯政治思想17页PPT

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:2.87 MB

- 文档页数:17

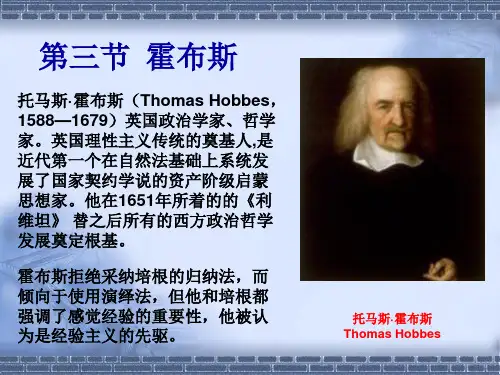

霍布士的政治思想第一节生平、著作和时代背景一、生平、著作托马斯·霍布士(Thomas Hobbes,1588—1679)可谓是政治思想史上继马基雅维里之后的又一个重量级人物,他们一同被视为西方近代政治思想的创始人。

霍布士,出生于英国南部威斯堡小镇。

父亲是一个乡村牧师,母亲是一个普通农妇。

由于家境贫寒,霍布士的教育由其伯父――一位殷实商人和市参议员资助完成。

15岁进牛津大学,攻读古典哲学和经院派逻辑。

毕业后担任大贵族威廉姆·卡文迪希伯爵的家庭教师,并与这个家庭建立长期密切的关系。

1610年,他先后访问法国、德国和意大利等国,学会法语和意大利语,看到了伽利略等新科学的巨大影响,回国后结识弗兰西斯·培根,两人在机械唯物主义方面不谋而合,交往颇深。

1629-1637,又两次周游欧洲大陆,同伽利略等科学家、思想家建立了广泛联系。

他专门研读了数学、物理学,并考察了威尼斯共和国的议会制度,读过马基雅维里、博丹、格老秀斯等人的政治学著作,这些都对霍布士的哲学观、政治观产生了重要影响。

1628,他翻译希腊名著《伯罗奔尼撒战争史》,在序言中,他开始对民主制可能造成的无政府状态表示担忧和反感,并对修昔底德对君主制的称誉深表赞同。

1640,发表论文《自然法与政治法的基本原理》,以支持王权。

由于英国革命爆发,他与王党分子逃到巴黎,并开始担任法国后来成为英国国王的查理二世的数学老师。

1651年,发表代表作《利维坦》。

这被称为他生平“体系最完备、内容最充实、论证最严密、学术价值最高、影响最大”的政治哲学著作。

他以《圣经》力大无穷的巨兽“利维坦”作喻,表达了对建立强大国家的强烈主张。

书中完全摒弃了君权神授学说并对教会权力进行攻击,从而遭到王党分子和法国政府的强烈反对,霍布士被迫于1651年返回英国,表示服从克伦威尔的统治,但对其提出担任行政部长的邀请婉辞不就。

1655年和1658年,又出版《论物体》、《论人》两部著作。

霍布斯及其政治思想特点的探究1. 引言1.1 霍布斯及其政治思想特点概述霍布斯(Thomas Hobbes)是17世纪英国著名的政治哲学家,他的政治思想在当时引起了极大的轰动,对后世的政治学理论产生了深远的影响。

霍布斯的政治思想以其对人性、社会契约和国家的观念而闻名,他认为人性是自私的、贪婪的,导致人与人之间的冲突和竞争,因此必须建立一个强大的中央政府来维持社会秩序和稳定。

霍布斯主张君主专制制度,认为只有强有力的君主才能确保社会的和平与稳定。

他的权力理论强调人们应该将自己的权力交给君主,以换取安全和秩序。

霍布斯的社会契约论则是他的政治理论的基石,认为人们应该通过契约同意放弃部分自由权利,以换取社会的安全与稳定。

霍布斯的政治思想对后世的政治哲学有着深远的影响,对于现代社会的政治实践也具有一定的启示意义。

2. 正文2.1 霍布斯的自然状态论霍布斯的自然状态论认为,在自然状态下,人们生活在无政府、无法律、无公共权威的状态下,每个人追求自己的利益,并且每个人都处于对其他人的威胁之下。

在这种状态下,人们之间存在着普遍的敌对、竞争和不信任。

霍布斯认为,自然状态是“人人为我,我为人人”的丛林法则,导致人们相互之间的战争和混乱。

为了摆脱自然状态所带来的负面影响,人们需要通过社会契约来建立一个社会统治形式,这就是政府的存在和合法性所基于的理论基础。

霍布斯的自然状态论强调个人本位的利益,因此他认为人们需要通过社会契约来放弃一部分自由,以换取集体安全和秩序。

在这一过程中,政府成为社会契约的执行者和监管者,确保个人遵守社会规范和法律。

霍布斯的自然状态论对后来的政治思想产生了深远的影响,如约翰·洛克的社会契约论和孟德斯鸠的分权理论都受到了霍布斯理论的启发。

在现代社会,霍布斯的自然状态论为我们理解政治权力、社会秩序的建立和政府的合法性提供了重要的思想基础。

2.2 霍布斯的人性观念霍布斯的人性观念是其政治思想的基础之一,他认为人性本质是自私、野蛮和贪婪的。

第七讲17世纪英国政治思想1.英国的宪政传统①英国君主立宪制度的建立奠定了近代西方的宪政传统。

西方宪政思想可以追溯到古罗马时期的共和思想,即不同政体因素互相混合、制约,从而达到平衡。

英国能够开创宪政传统,是由其历史及沉淀于其中的独特的政治文化分不开的。

②英国的历史:a.英国的起源第一步始于盎格鲁-撒克逊人对不列颠的入侵。

公元433年,不列颠人到罗马请求罗马人帮他们反对波克特人,在没有成功的情况下,他们找到了盎格鲁人。

因此,他们入侵的方式是整体性移民,属于民族迁移型的移民入侵。

定居下来以后,开始建立若干小王国,6世纪末形成七个较大的大国,“七国时代”持续了300多年。

它们之间展开了争霸斗争,但每一代霸主仅满足于被他国尊为名义上的“不列颠统治者”。

8世纪起,丹麦人入侵英格兰,各王国主动联合在一起保宗卫国。

随着入侵者被赶走,统一的英格兰就出现了,各王国分到作为单独的郡而成为统一王国的一部分。

b.1066年诺曼征服英国,英国的封建制度迅速建立。

于是,原始民主遗风之基础得以保留。

诺曼时期英国国王与贵族之间的封建法权关系成为推动英国宪政成长的力量。

③英国宪政的生长因素:a.撒克逊人是日尔曼人的分支,入侵不列颠之前处于民族社会解体阶段,社会秩序主要靠原始部落习惯来维持。

这种原始习惯成为治理国家,维护社会秩序的主要手段,产生了英国早期的习惯法。

习惯法的生命源于社会的普遍认同,而非统治者的意志,从而赋予早期英国法以浓厚的社会公益性,从而孕育了英国人法律至上的法治观念。

“王在法下”成为英国法律传统与生俱来的属性之一。

(法治传统)b.英国的政治协商传统同样源于日尔曼的原始习惯。

因为古代日尔曼人的公共事务都是通过民众大会协商解决的,英国建国后,这种协商决策习惯继承下来,其形式主要通过贤人会议来实现,该会议容纳了英国社会有影响的几大势力。

国王利用贤人会议进行统治的过程,也是贤人会议参政议政分享国家统治权的过程,这种会议协商制度使古代原始的协商议事习惯被保存下来。

霍布斯及其政治思想特点的探究霍布斯(Thomas Hobbes)是英国近代哲学家,他的政治思想被誉为“契约论”,认为人类社会要有秩序、和平,就必须建立一个强大的国家来统治、管理人民。

他的政治思想主要展现在《利维坦》一书中。

霍布斯的政治思想特点主要有以下几个方面:一、强调权力的合法性来源霍布斯认为,权力的合法性来源于人民的共识,即“契约”所建立的政治体系。

他认为人们在原始状态下是孤立无援的,为了自身利益与安全,人们必须通过契约的方式建立政治和社会秩序。

因此,政治权力来源于契约,而非天赋、神授等。

二、主张对治理者束缚在霍布斯看来,国家是治理者与被治理者签署契约来实现利益平衡的产物。

契约既给予了国家的治理者一定的权力,也限制了他的行动。

治理者必须尊重人民的权利,否则当权者的行为将被视为“奉行暴政”,人民有权反抗并推翻当政者。

三、认为人性本恶霍布斯认为,人性本恶,人类的欲望无止境地追求满足,没有关爱、良心与道德等概念。

人生来就有自私自利的本能,这种本能只能在有组织的政治和社会框架下才得以平衡、调节和限制。

人性本恶的观点在当时的哲学思想中属于一种悲观主义的思想。

四、强调国家权力的维护国家权力是维护社会秩序、统一权力的中心,霍布斯认为,国家权力必须得到维护,如果权力丧失了对社会的控制,社会就会陷入无序、动荡和混乱,这对人民的生命、财产和自由都是一种威胁。

在霍布斯的眼中,政治秩序来自于一个以国家为中心的体制,为了维护国家的权威,必须消除人民之间的内部矛盾并清除反抗国家的势力。

总之,霍布斯的政治思想体现出对社会秩序、社会控制和国家统一的强调,他强调政治秩序的实现是以权力渐进合法化的方式进行的,而非通过暴力征服与统治。

他的政治思想无疑在那个时代的英国有着相当大的实际指导意义。

第六章 17 世纪英国政治思想•英国革命和政治思想(一)历史传统: 13 世纪大宪章限制王权、本世纪末国会建立国会专制时存在,英革命,国会恢复权利,革命后君主立宪(二)资本主义的发展特点,资本主义渗入农村,新贵族出现, 15 世纪红白玫瑰战争使旧贵族自相杀殆尽(三)清教徒革命:加尔文教旗帜•宗教矛盾和斗争作用;对清教徒迫害,激起反抗,自由问题较突出;•将教会改革,教会内平等、自由、和民主组织搬到国家中。

(四)革命中的思想斗争1 )菲尔麦2 )霍布斯3 )弥尔顿、哈灵顿4 )利尔本5 )温斯坦莱6 )洛克第二节霍布斯( Hobbes )一、生平著作霍布斯( 1588-1697 ),出生于英格兰一个乡村牧师家庭,他是个早产儿。

霍布斯自己讲过。

他母亲怀着他的时候,听到西班牙无敌舰队进攻英国的消息,由于受到惊吓而早产了他。

霍布斯声称,正是由于这个缘故,他非常热爱和平。

我们看到,他这个人十分胆小、谨慎、敏感。

他也把这解释为是上述原因造成的。

他说:“恐惧是我的孪生兄弟”。

这种解释是否有生理学和心理学的依据,还不可考。

这个早产儿看来在智力上也早熟。

他十四岁就能把古希腊作品翻译成拉丁文,十五岁进牛津大学,当时牛津大学教授圣经和用经院哲学观点讲授亚里士多德哲学。

霍布斯对此非常反感,他说他在大学里没学到任何有益的东西。

二十二岁时,他受骋为一个贵族的家庭教师,并伴随他的学生作“大周游”(当时英国富贵家庭的子弟为完成教育,到欧洲大陆上去周游、旅行、参观、考察、访问)。

在作家庭教师期间,霍布斯三次周游欧洲大陆。

当时,大陆上欧洲各国盛行君主专制制度。

特别是法国,黎塞留统一法国确立君主专制制度,法国空前统一和强盛,这对霍布斯发生很影响。

同时,霍布斯也结识了一些著名学者,笛卡儿、伽桑狄、伽里略等。

受到他们哲学和科学思想的影响。

(伽里略正被囚禁,弥尔顿也是这时见过伽利略,并受到鼓舞,广播剧《森林中的小屋》)英国革命爆发后,由于他与贵族私人关系密切,害怕受到议会党人的迫害,逃亡到巴黎。

霍布斯及其政治思想特点的探究霍布斯( Thomas Hobbes, 1588-1679)是17世纪英国最重要的政治哲学家之一。

他以其关于政治和社会秩序的观点而闻名,是现代政治哲学的奠基人之一。

霍布斯的政治思想深刻影响了西方政治理论和实践,对后世的政治哲学有着重要的影响。

本文将从霍布斯的生平、主要作品、政治思想特点等方面对其进行探究。

霍布斯出生于英国的一个小镇,他的家庭并不富有,但他却有幸得到了良好的教育。

他先后就读于牛津大学和剑桥大学,后来成为一名学者和哲学家。

在长达80多年的人生中,霍布斯一直致力于研究政治哲学和社会学问题,留下了许多思想精深的作品。

其中最为著名的莫过于《利维坦》和《市民论》了。

《利维坦》是霍布斯最重要的著作之一,也是其政治思想的代表作。

在这部著作中,霍布斯试图阐述自己对人类政治组织的理解和对社会秩序的构想。

他认为,人类天生是自私的、激进的和有争斗性的动物,如果没有政府的约束和控制,人们只会陷入不断的争斗和混乱之中。

政府的存在是为了维持社会秩序和保障人们的生命、财产和自由。

而政府的合法性则来自人民的授权,人民必须愿意放弃一部分个人自由,来换取政府的保护和治理。

这一观点对后世的政治思想产生了深远的影响,为社会契约论的形成奠定了重要的基础。

除了《利维坦》,霍布斯的另一部重要著作是《市民论》。

在这部著作中,他对政治权力的组织和分配进行了深入的思考。

霍布斯认为,政治权力应当集中于一个中央政府的手中,而这个政府应当是绝对的和独裁的。

这是因为,只有绝对的政治权力才能够有效地维持社会秩序,保护人民的生命和财产。

他主张国家的最高权力应当集中于君主或者议会等中央政府机构,而地方政府应当服从中央政府的统一指挥。

这一思想也为后来绝对君主制的形成提供了理论支持。

可以看出,霍布斯的政治思想具有明显的集权主义倾向,他主张国家应当具有绝对的权力,以维护社会秩序和稳定。

与此他也提出了社会契约论的观点,强调政府的合法性来自人民的授权。

5. Hobbes托马斯·霍布斯(Thomas Hobbes, 1588-1679),17世纪英国伟大的政治思想家。

就读于牛津大学,结识英国的本·琼生(Ben Johnson)和弗朗西斯·培根(Francis Bacon)、意大利的伽利略(Galileo Galilei)、法国的笛卡尔(Rene Descartes)等思想名家。

霍布斯深受修昔底德《伯罗奔尼撒战争史》及其现实主义思想的影响,成为第一个将其译成英文的学者。

贯穿于霍布斯一生的几大命运起落,几乎都与内乱和战争相连,因为他亲身经历了英国内战和欧洲大陆的三十年战争。

基于对社会动荡的敏感性和敏锐性,他试图去解释人和社会的本质,去发现政治的内在规律。

享有盛名的《利维坦》(Leviathan),就是这种努力的卓越表现。

霍布斯在书中写道,人类进入社会并组成国家之前,处于人人自危的普遍争斗的自然状态,人与人之间充满着自私自利、猜疑、恐惧、贪婪和残暴无情;在这种情况下,人的自然本性首先在于求得自保和生存,为此,个人出于对和平与安定生活的渴望,出于理性,相互订立契约,放弃个人的自然权利,将它交给一个集体,这个集体就拥有来源于所有个人意志的集体意志,它就成为主权者,亦即国家。

主权是绝对和至高无上的,也是不可分割和不可转让的。

霍布斯还将人与人之间的自然状态模式应用于国际关系,认为国际关系处于无政府状态,普遍的国际冲突或战争状态是它的根本特征。

在战争状态下,不存在任何道义,没有是非之分,也没有正义与非正义的区别。

一国为了安全,可以不择手段,连本身的承诺都可以背弃。

当然,出于国家利益的需要,主权国家可以根据理性而结盟,并推行均势外交。

霍布斯揭示的国际关系的无政府特征,极大了影响了20世纪的现实主义学派的思维。

本篇选自《利维坦》,探讨了人与人之间的自然状态以及自然状态下人的自然权利和道德限度。

Of the State of NatureNature has made men so equal, in the faculties of the body, and mind; as that though there be found one man sometimes manifestly stronger in body, or of quicker mind than another; yet when all is reckoned together, the difference between man, and man, is not so considerable, as that one man can thereupon claim to himself any benefit, to which another may not pretend, as well as he. For as to the strength of body, the weakest has strength enough to kill the strongest, either by secret machination, or by confederacy with others, that are in the same danger with himself.And as to the faculties of the mind, setting aside the arts grounded upon words, and especially that skill of proceeding upon general, and infallible rules, called science; which very few have, and but in few things; as being not a native faculty, born with us; nor attained, as prudence, while we look after somewhat else, I find yet a greater equality among men, than that of strength.1For prudence is but experience; which equal time, equally bestows on all men, in those things they equally apply themselves unto. That which may perhaps make such equality incredible, is but a vain conceit of one’s own wisdom, which almost all men think they have in a greater degree, than the vulgar; that is, than allmen but themselves, and a few others, whom, by fame, or for concurring with themselves, they approve. For such is the nature of men, that howsoever they may acknowledge many others to be more witty, or more eloquent, or more learned; yet they will hardly believe there be many so wise as themselv es; for they see their own wit at hand, and other men’s at a distance. But this proves rather that men are in that point equal, than unequal. For there is not ordinarily a greater sign of the equal distribution of anything, than that every man is contented with his share.From this equality of ability, arises equality of hope in the attaining of our ends. And therefore if any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies; and in the way to their end, which is principally their own conservation, and sometimes their delectation only, endeavor to destroy or subdue one another. And from hence it comes to pass that where an invader has no more to fear than another man’s single power; if one plant, sow, build, or possess a convenient seat, others may probably be expected to come prepared with forces united to dispossess and deprive him, not only of the fruit of his labor, but also of his life or liberty. And the invader again is in the like danger of another.And from this diffidence of one another there is no way for any man to secure himself, so reasonable as anticipation—that is, by force or wiles to master the persons of all men he can, so long till he see no other power great enough to endanger him; and this is no more than his own conservation requires, and is generally allowed. Also, because there be some that taking pleasure in contemplating their own power in the acts of conquest, which they pursue farther than their security requires, if others that otherwise would be glad to be at ease within modest bounds should not by invasion increase their power, they would not be able, long time, by standing only on their defense, to subsist. And by consequence, such augmentation of dominion over men being necessary to a man’s conservation, it ought to be allowed him.2Again, men have no pleasure, but on the contrary a great deal of grief, in keeping company where there is no power able to overawe them all. For every man looks that his companion should value him at the same rate he sets upon himself; and upon all signs of contempt or undervaluing naturally endeavors as far as he dares (which among them that have no common power to keep them in quiet is far enough to make them destroy each other), to extort a greater value from his contemners by damage and from others by the example.3So that in the nature of man we find three principal causes of quarrel: first, competition; secondly, diffidence; thirdly, glory.The first makes men invade for gain, the second for safety, and the third for reputation. The first use violence to make themselves masters of other men's persons, wives, children, and cattle; the second, to defend them; the third, for trifles, as a word, a smile, a differentopinion, and any other sign of undervalue, either direct in their persons or by reflection in their kindred, their friends, their nation, their profession, or their name.Hereby it is manifest that, during the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every man.4 For WAR consists not in battle only, or the act of fighting, but in a tract of time5 wherein the will to contend by battle is sufficiently known; and therefore the notion of time is to be considered in the nature of war as it is in the nature of weather. For as the nature of foul weather lies not in a shower or two of rain but in an inclination thereto of many days together, so the nature of war consists not in actual fighting but in the known disposition thereto during all the time is no assurance to the contrary. All other time is PEACE.Whatsoever, therefore, is consequent to a time of war where every man is enemy to every man, the same is consequent to the time wherein men live without other security than what their own strength and their own invention shall furnish them with all. In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and, which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of man solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.It may seem strange to some man that has not well weighed these things that nature should thus dissociate and render men apt to invade and destroy one another; and he may therefore, not trusting to this inference made from the passions, desire perhaps to have the same confirmed by experience. Let him therefore consider with himself—when taking a journey he arms himself and seeks to go well accompanied, when going to sleep he locks his doors, when even in his house he locks his chests, and this when he knows there be laws and public officers, armed, to revenge all injuries shall be done him—what opinion he has of his fellow subjects when he rides armed of his fellow citizens when he locks his doors, and of his children and servants when he locks his chests. Does he not there as much accuse mankind by his actions as I do by my words? But neither of us accuse man's nature in it. The desires and other passions of man are in themselves no sin. No more are the actions that proceed from those passions till they know a law that forbids them, which, till laws be made, they cannot know, nor can any law be made till they have agreed upon the person that shall make it.It may peradventure be thought there was never such a time nor condition of war as this, and I believe it was never generally so over all the world; but there are many places where they live so now. For the savage people in many places of America, except the government of small families, the concord whereof depends on natural lust6, have nogovernment at all and live at this day in that brutish manner as I said before. Howsoever, it may be perceived what manner of life there would be, where there were no common power to fear, by the manner of life, which men that have formerly lived under a peaceful government, use to degenerate into, in a civil war.But though there had never been any time wherein particular men were in a condition of war one against another, yet in all times kings and persons of sovereign authority, because of their independency, are in continual jealousies and in the state and posture of gladiators, having their weapons pointing and their eyes fixed on one another—that is, their forts, garrisons, and guns upon the frontiers of their kingdoms, and continual spies upon their neighbors—which is a posture of war. But because they uphold thereby the industry of their subjects, there does not follow from it that misery which accompanies the liberty of particular men.7To this war of every man against every man, this also is consequent: that nothing can be unjust. The notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice, have there no place. Where there is no common power, there is no law; where no law, no injustice. Force and fraud are in war the two cardinal virtues. Justice and injustice are none of the faculties neither of the body nor mind. If they were, they might be in a man that were alone in the world, as well as his senses and passions. They are qualities that relate to men in society, not in solitude. It is consequent also to the same condition that there be no property, no dominion, no Mine and Thine distinct; but only that to be every man's that he can get, and for so long as he can keep it. And thus much for the ill condition which man by mere nature is actually placed in, though with a possibility to come out of it consisting partly in the passions, partly in his reason.The passions that incline men to peace are fear of death, desire of such things as are necessary to commodious living, and a hope by their industry to obtain them. And reason suggests convenient articles of peace, upon which men may be drawn to agreement. These articles are they which otherwise are called the Laws of Nature8.Quoted from Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (New York: Macmillan/Collier Books, 1962).1“至于智力,除了以词语为基础的文艺,特别是科学,即根据普遍的和颠扑不破的法则处理问题的技能,这种技能很少有人具有,而且也只限于少数事物,它既不是一种天生的能力,也不象慎虑那样是在我们关注其他事物时获得的,我还发现在智力方面人与人之间更加平等。

六、霍布斯的政治思想(一)关于国家起源和国家本质的思想1.自然法学说(1)自然状态自然状态是一种“人人相互为敌的战争状态”,不存在是和非、公正与不公正原因:人类是自私自利的,在人类的天性中便存在导致人们相互斗争的种种因素;人类是生而平等的,任何人想取得同一种东西而又不能共同享用时,彼此就会为仇敌。

(2)“自然律”:是依靠理性力量月诉人类行为,使人们共同履行一种方便易行的和平条件的自然法。

(1)自然法是最根本的原则是寻求和平;自然法是永恒不变的,需要某种权威使人们必须遵守它。

2.契约论(1)公共权力或国家的建立为了社会的共同利益,为了安全和平的需要,人们在理性的启迪下订立了契约,各人放弃了自己管理自己的权利,把它交给某人或某个集体,让他们拥有权威来管理社会。

(2)霍布斯契约论的特点:人们订立契约时,交出的是他们全部的权利和权力;被授予权力的人获议会即主权者;主权者没有参加契约,因而不受契约的约束,他的权利和权力是绝对的、至高无上的;(3)国家观念的认识将按照上述契约而联合在一个人格里的人群就做国家国家的本质就是主权者;他把主权者看作是一个公共人格他所说的“人格”不过是公共权力的抽象体现;实质上,它是将公共权力看作是国家的本质3.关于国家起源和国家本质的思想的评价(1)已经开始用人的严管来看待国家问题,他的自然法和契约论否定了君受神权,肯定了君权神受,指明了国间建立和存在的主要目的在于维护和平安全,是有进步意义的;(2)但他的契约论却是相当的保守,得出了君主主权的结论,这与他用契约论、自然法解析国家起源和本质是矛盾的;这种矛盾反映了英国大资产阶级和上层新贵既要进行一定程度改革,又害怕人民革命,随时准备与封建王权相妥协的政治立场。

(二)主权与政体理论1.主权(1)定义主权是决断和处理国家一切事物的最高权力,是国家的“灵魂”。

(2)内容:繁育公共和平及安全有关的一切社会政治经济权力,均属主权的范围。

包括: 立法权;与其他民族的宣战、媾和权;对一切参议人员、大臣、地方长官和官吏的甑选权;颁布荣衔爵禄之权;掌握和运用国家全部武装力量之权;对一切意见和学说、书籍的审查权和最后裁决权。

第七章近代西方自由民主思想的产生——17世纪英国的政治思想参考书霍布斯:《利维坦》,商务印书馆1985年版;洛克:《政府论》,商务印书馆1983年版。

自由主义及其民主观念是西方政治思想中的主流思想。

我们讲近代西方政治思想史,主要就是围绕自由主义和它的民主观念来讲,其它则不能不舍去。

西欧各国到了16世纪,商业已甚为发达,重商主义成为此后200年间欧洲的主流经济思想。

商业促进了国家的统一与独立,结果产生了君主专制政治。

极端的专制势必引发反抗暴君的理论,这一理论的口号就是自由和平等。

自由和平等本来是欧洲宗教改革时用来向罗马教廷宣战的口号,其最早产生于欧洲的意大利、德国和瑞士。

当时所谓自由是指个人信教的自由,平等是指信徒一律平等。

到了市民阶级反抗君权时,这两个口号便成为他们斗争的武器。

不过,从自由的口号发展成为一套自由主义的理论、一套政治思想,首先是出现在英国。

一、17世纪的自然法理论17世纪,西欧的政治学说是以自然法观念为基础的。

自然法观念曾有力地促进了近代西方自由民主政治的发展,成为它的主要思想基础。

什么是自然法?在宇宙结构中,不知怎的,有一套辨别是非的法则;它是天赋的,并非是人的发明,它不是某个国家的传统、习惯或风俗所决定,也不是由法庭施行的成文法所决定,更不是由那一群人或那个国王所决定。

从根本意义上说,自然法超然存在,超脱一切人群,凌驾一切人群,类似于中国古代的“天理”。

它普遍适用,对一切人都一视同仁,谁也不能将它捏造以迎合自己。

那么,我们如何发现自然法?答案是,我们凭理性发现。

人是有理性的动物,一切人都有大致相同的思维能力和理解能力,即使蛮族,起码也具有潜在的能力,一旦得到启蒙,就可以发挥出来。

在17和18世纪的欧洲,这套哲学普遍为人接受。

有些人由于继续信奉中世纪的哲学,认为自然法是上帝律法的一个部分,一些世俗精神较浓的人,则认为自然法超然独立。

不管怎么说,自然法观念和相信人类有理性的观念齐头并进,相得益彰,是那个时代思想的根本所在。