东南大学2004基础英语与写作答案

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:1008.35 KB

- 文档页数:14

![2004年高考试题——英语(江苏卷)[1]](https://img.taocdn.com/s1/m/e15e274658fafab069dc026d.png)

2004年普通高等学校招生全国统一考试英语(江苏卷)National Matriculation English Test(NMET 2004)本试卷分第一卷(选择题)和第二卷(非选择题)两部分。

共150分。

考试时间120分钟。

第一卷(选择题共115分)第一部分:听力(共两节,满分30分)做题时,先将答案划在试卷上。

录音内容结束后,你将有两分钟的时闯将试卷上的答案转涂到答题卡上。

第一节(共5小题;每小题1.5分,满分7.5分)听下面5段对话。

每段对话后有一个小题,从题中所给的A、B、C三个选项中选出最佳选项,并标在试卷的相应位置。

听完每段对话后,你都有l0秒钟的时间来回答有关小题和阅读下一小题。

每段对话仅读一遍。

例:How much is the shirt?A.£19.15. B.£9.15. C.£9.18.答案是B。

1.What do we learn about the man?A.He slept well on the plane.B.He had a long trip.C.He had a meeting.2.Why will the woman stay home in the evening?A.To wait for a call.B.To watch a ball game on TV.C.To have dinner with a friend.3.What gift will the woman probably get for Mary?A.A school bag. B.A record.C.A theatre ticket.4.What does the man mainly do in his spare time?A.Learn a language. B.Do some sports. C.Play the piano.5.What did the woman like doing when she was young?A.Riding a bicycle with friends.B.Traveling the country.C.Reading alone.第二节(共15小题;每小题1.5分,满分22.5分)听下面5段对话。

2004年AP英语文学与写作考试真题及答案1、Neither she nor her friends ______ been to Haikou. [单选题] *A. have(正确答案)B. hasC. hadD. having2、Something must be wrong with the girl’s _______. She can’t hear clearly. [单选题] *A. ears(正确答案)B. noseC. armsD. eyes3、37.It’s fun _________ a horse with your best friends on the grass. [单选题] * A.to ride (正确答案)B.ridingC.ridesD.ride4、Tomorrow is Ann’s birthday. Her mother is going to make a _______ meal for her. [单选题] *A. commonB. quickC. special(正确答案)D. simple5、In 2019 we moved to Boston,()my grandparents are living. [单选题] *A. whoB. whenC. where(正确答案)D. for which6、--The last bus has left. What should we do?--Let’s take a taxi. We have no other _______ now. [单选题] *A. choice(正确答案)B. reasonC. habitD. decision7、Nearly two thousand years have passed _____ the Chinese first invented the compass. [单选题] *B. beforeC. since(正确答案)D. after8、My father?is _______ flowers. [单选题] *A. busy watering(正确答案)B. busy waterC. busy with wateringD. busy with water9、We were caught in a traffic jam. By the time we arrived at the airport the plane _____. [单选题] *A. will take offB. would take offC. has taken offD. had taken off(正确答案)10、They may not be very exciting, but you can expect ______ a lot from them.()[单选题] *A. to learn(正确答案)B. learnD. learned11、20.Jerry is hard-working. It’s not ______ that he can pass the exam easily. [单选题] *A.surpriseB.surprising (正确答案)C.surprisedD.surprises12、Her ideas sound right, but _____ I'm not completely sure. [单选题] *A. somehow(正确答案)B. somewhatC. somewhereD. sometime13、We had a party last month, and it was a lot of fun, so let's have _____ one this month. [单选题] *A.otherB.the otherC.moreD.another(正确答案)14、If you had told me earlier, I _____ to meet you at the hotel. [单选题] *A. had comeB. will have comeC. would comeD. would have come(正确答案)15、My mother’s birthday is coming. I want to buy a new shirt ______ her.()[单选题] *A. atB. for(正确答案)C. toD. with16、I gave John a present but he gave me nothing_____. [单选题] *A.in advanceB.in vainC.in return(正确答案)D.in turn17、I should like to rent a house which is modern, comfortable and _____, in a quiet neighborhood. [单选题] *A.in allB. after allC. above all(正确答案)D. over all18、79.–Great party, Yes? ---Oh, Jimmy. It’s you!(C), we last met more than 30 years ago. [单选题] *A. What’s moreB. That’s to sayC. Believe it or not (正确答案)D. In other words19、The travelers arrived _______ Xi’an _______ a rainy day. [单选题] *A. at; inB. at; onC. in; inD. in; on(正确答案)20、--Henry treats his secretary badly.--Yes. He seems to think that she is the _______ important person in the office. [单选题] *A. littleB. least(正确答案)C. lessD. most21、Stephanie _______ going shopping to staying at home. [单选题] *A. prefers(正确答案)B. likesC. preferD. instead22、The blue shirt looks _______ better on you than the red one. [单选题] *A. quiteB. moreC. much(正确答案)D. most23、()of the twins was arrested because I saw them both at a party last night. [单选题] *A. NoneB. BothC. Neither(正确答案)D. All24、-----How can I apply for an online course?------Just fill out this form and we _____ what we can do for you. [单选题] *A. seeB. are seeingC. have seenD. will see(正确答案)25、We can _______ some information about this city on the Internet. [单选题] *A. look up(正确答案)B. look likeC. look afterD. look forward to26、28.The question is very difficult. ______ can answer it. [单选题] *A.EveryoneB.No one(正确答案)C.SomeoneD.Anyone27、We need two ______ and two bags of ______ for the banana milk shake.()[单选题]*A. banana; yogurtB. banana; yogurtsC. bananas; yogurt(正确答案)D. bananas; yogurts28、When you have trouble, you can _______ the police. They will help you. [单选题] *A. turn offB. turn to(正确答案)C. turn onD. turn over29、He was?very tired,so he stopped?_____ a rest. [单选题] *A. to have(正确答案)B. havingC. haveD. had30、48.—________ is your new skirt, Lingling?—Black. [单选题] *A.HowB.What colour(正确答案)C.Which D.Why。

Section A Intensive Reading and WritingHow to Write with styleBy Kurt V onnegut[1] Newspaper reporters and technical writers are trained to reveal almost nothing about themselves in their writings. This makes them freaks in the world of writers, since almost all of the other ink-stained wretches in that world reveal a lot about themselves to readers. We call these revelations, accidental and intentional, elements of style.[2] These revelations tell us as readers what sort of person it is with whom we are spending time. Does the writer sound ignorant or informed, stupid or bright, crooked or honest, humorless or playful? And on and on.[3] Why should you examine your writing style with the idea of improving it? Do so as a mark of respect for your readers, whatever you’re writing. If you scribble your thoughts any which way, your readers will surely feel that you care nothing about them. They will mark you down as an egomaniac or a chowderhead -or, worse, they will stop reading you.[4] The most damning revelation you can make about yourself is that you do not know what is interesting and what is not. Don’t you yourself like or dislike writers mainly for what they choose to show you or make you think about? Did you ever admire an emptyheaded writer for his or her mastery of the language ? No.[5] So your own winning style must begin with ideas with ideas in your head.1. Find a subject you care about[6] Find a subject you care about and which you in your heart feel others shouldcare about. It is this genuine caring, and not your games with language , which will be the most compelling and seductive element in your style.[7] I am not urging you to write an novel, by the way – although I would not be sorry if you wrote one, provided you genuinely cared about something. A petition to the mayor about a pothole in front of your house or a love letter to the girl next door will do.2. Do not ramble, though[8] I won’t ramble on about that.3. Keep it simple[9] As for your use of language: Remember that two great masters of language, William Shakespeare and James Joyce, wrote sentences which were almost childlike when their subjects were most profound. “To be or not to be?” asks Shakespeare’s Hamlt. The longest word is three letters long. Joyce, when he was frisky, could put together a sentence as intricate and as glittering as a necklace for Cleopatra, but my favorite sentence in his short story , “Evelin”is this one: “She was tried.”At that point in the story, no other words could break the heart of a reader as those three words do.[10] Simplicity of language is not only reputable, but perhaps even sacred. The Bible opens with a sentence well within the writing skills of a lively fourteen-year-old: “In the beginning God created the neaven and the earth.”4. Have guts to cut[11] It may be that you, too, are capable of making necklaces for Cleopatra, so to speak. But your eloquence should be the servant of the ideas in your head. Your rulemight be this: If a sentence, no matter how excellent, does not illuminate your subject in some new and useful way, scratch it out.5. Sound like yourself[12] The writing style which is most natural for you is bound to echo the speech you heard when a child. English was Conrad’s third language , and much that seems piquant in his use of English was no doubt colored by his first language, which was Polish. And lucky indeed is the writer who has grown up in Ireland, for the English spoken there is so amusing and musical. I myself grew up in Indianapolis, where common speech sounds like a band saw cutting galvanized tin, and employs a vocabulary as unornamental as a monkey wrench.[13] In some of the more remote hollows of Appalachia, children still grow up hearing songs and locutions of Elizabethan times. Yes, and many Americans grow up hearing a language other than English, or an English dialect a majority of Americans cannot understand.[14] All these varieties of speech are beautiful , just as the varieties of butterflies are beautiful, No matter what your first language, you should treasure it all your life, If it happens to not be standard English, and if it shows itself when you write standard English, the result is usually delightful, like a very pretty girl with one eye that is green and one that is blue.[15] I myself find that I trust my own writing most, and others seem to trust it most , too, when I sound most like a person from Indianapolis, which is what I am. What alternatives do I have? The one most vehemently recommended by teachers has no doubt been pressed on you, as well: to write like cultivated Englishmen of acentury or more ago.6. Say what you mean[16] I used to be exasperated by exasperated by such teachers, but am no more, I understand now that all those antique essays and stories with which I was to compare my own work were not magnificent for their datedness or foreignness, but for saying precisely what their authors meant them to say. My teachers wished me to write accurately, always selecting the most effective words, and relating the words to one another unambiguously, rigidly, like parts of a machine. The teachers did not want to turn me into an Englishman after all. They hoped that I would become understandable—and therefore understood. And there went my dream of doing with words what words what Pablo Picasso did with paint or what any number of jazz idols did with music. If I broke all the rules of punctuation, has words mean whatever I wanted them to mean, and strung them together higgledy- piggledy, I would simply not be understood. So you , too, had better avoid Picasso-style writing, if you have something worth saying and wish to be understood.[17] Readers want our pages to look very muck like pages they have seen before. Why? This is because they themselves have a tough job to do, and they need all the help they can get from us.7. Pity the readers[18] They have to identify thousands of little marks on paper, and make sense of them immediately. They have to read, an art so difficult that most people don’t really master it even after having studied it all through grade school and high school–twelve long years.[19] So this discussion must finally acknowledge that out stylistic options as writers are neither numerous nor glamorous, since out readers are bound to be such imperfect artists. Our audience requires us to be sympathetic and patient readers, ever willing to simplify and clarify- whereas we would rater soar high above the crowd, singing like nightingales.[20] That is the bad news. The good news is that we Americans are governed under a unique Constitution, which allows us to write whatever we please without fear of punishment. So the most meaningful aspect of out styles, which is what we choose to write about, is utterly unlimited.8. For really detailed advice[21] For a discussion of literary style in a narrower sense, in a more technical sense, I recommend to your attention The Elements of style, by William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White. E. B. White is, of course, one of the most admirable literary stylists this county has so far produced. You should realize, too, that no one would care how well or badly Mr. White expressed himself, if he did not have perfectly enchanting things to say.Part I Comprehension of the Text1. What is Kurt V onnegut arguing in his writing? What’s his understanding of writing style?2. What kind of language style does he use in this essay?3. What does the author mean by mentioning “Picasso style and jazz style”?4. Does the author practice what he preaches in his writing?5. What does the author suggest at the end of this essay?Part II VocabularyA. Choose the one from the four choices that best explains the underlined word or phrase.1. He finds himself involved with a crooked businessman and a group of thugs who attempt to sabotage his invention.A. distortedB. twistedC. dishonestD. deceptive2. He remembered how proud and haughty her face was and scratched out the word he had written.A. polishedB. perishedC. deletedD. depleted3. If you choose credit counseling as a strategy for your debt, you must make sure you’re choosing a reputable company and not a scammer.A. well-knownB. professionalC. reliableD. respectable4. He added that nature gave him everything he need as a champion-unusual strength, stamina, a terrific punch, and plenty of guts.A. wisdomB. courageC. wealthD. charm5. Qualitative research strategies of interview, participant observation, and field notes were used to illuminate the topic.A. reinforceB. decorateC. paraphraseD. interpret6. He suddenly found himself exasperated by slow moving pedestrians, and, like a true New Yorker, began darting around them instead.A. provokedB. offendedC. annoyedD. disappointed7. As one moves through this colourful world of Indian handicrafts, many intricate paintings and sculptures catch the eye.A. charmingB. elegantC. delicateD. complicated8. Many judges will acknowledge that one of the most difficult aspects of a criminal case is sentencing.A. admitB. assertC. proveD. agree9. Its charming towns and picturesque landscapes provide the enchantingsurroundings for your sparkling romantic holiday treat.A. magnificentB. compellingC. genuineD. glamorous10. Circumstances beyond my control have left me with no alternative but to returnmy vehicle to lender.A. meansB. optionC. fashionD. mannerB. Choose the one from the four choices that best completes the sentence.1. The infinite beauty of a reverse navel ring ___________with dual colors in the trio of stones that fill the center of the continuous infinity design.A. twinklesB. simmersC. flashesD. glitters2. He was early _____________as a man of ability and maturity of character, a promise fully realized in his many great achievements.A. marked downB. turned downC. looked upD. agreed upon3. When he was not quite able to follow, Newton just took the pad from his friend’s hands and _____________his own remarks into the notebook.A. stumbledB. scrabbledC. scribbledD. scrupled4. There are many reports of the Prophet’s mastery of the Arabic tongue together with his _________ and fluency of speech.A. eloquenceB. sequenceC. frequencyD. delinquency5. These stories and the principles principles drawn from them are ___________toyou for your benefit and learning and enjoyment.A. commentedB. commendedC. commandedD. commenced6. Some applicants may _________ on about themselves in a manner that may appear self-indulgent and not very appealing to the committee.A. rambleB. tumbleC. complainD. chatter7. Cherry tomatoes have a strong taste and are very juicy-this makes them ideal for creating this ___________sauce.A. vehementB. friskyC. disgustingD. piquant8. To help soldiers _________ data from drones, satellites and ground sensors, the U.S. military now issues the iPod Touch.A. take advantage ofB. make sense ofC. take notice ofD. make use of9. As the same way, we need to listen to some fascinating English materials as many as possible, so that we can ___________ our interest to learn it.A. motivateB. cultivateC. advocateD. retaliate10. Her 8-year-old daughter was adorable as she got to meet her __________, Simon, whom she praises for his negativity.A. imageB. idiotC. idolD. tokenC. Complete each sentence with the proper form of the word given in theparenthesis.1. Many philosophers hold ________ about mental properties, and manyphilosophers hold humility about fundamental physical properties. ( reveal )2. By the mid 20th century, humans had achieved a ________ of technology sufficient to leave the atmosphere of the Earth for the first time and explore space. ( master )3. Despite the apparent ______ of the water molecule, liquid water is one of the mostmysterious substances in out world. ( simple )4. On this level, a common protocol to structure the data is used; the format of the information exchange is ________ defined. ( ambiguity)5. It was expected that these images will look charming and __________, but thefinal result was a bit different. ( glamour)6. I find it hard to be _________ about a man who used his wealth and power tomolest children and to then evade justice. ( sympathy)7. The question is whether or not it is possible to bottle these pheromones and use them for our own _________ advantage. ( seduce)8. Despite the gruesome images on cigarette packs, a survey shows Australiansmoker are surprisingly ________ of the dangers of the habit. ( ignore)9. In several poems the reader will encounter the plain, ________ language really used by common man, and this goes straight to the heart. ( ornament)10. Many new illustrations help to _______the text and make the book moreinstructive to students and practitioners. ( clear)Part III ClozeDirections: Read the passage through. Then go back and choose one suitable word or phrase for each blank in the passage.It is very difficult to arriver at a full description of style that is acceptable to all scholars. As such there are many definitions of the word style __1_________ there are scholars yet no __2_________is reached among them on what style is. Chapman is of the view that style is the product of a common relationship between language users. He _3______ said that style is not an ornament or virtue and is not __4______ to written language, or to literature or to any single aspect of language.Language is human __5_______ and used in society. No human language is fixed, uniform, or varying; all languages show internal variation. This variation sows the _6_______ feature of individuals or a group of people which is usually referred to as style. Style is popularly _7_________ to as “dress”of thought, as a person’s method of _8_______ his thought, feelings and emotions, as the manner of speech or writing. From the definition above, one can __9_______ that style is the particular way in which an individual communicates his thought which _10______ him from others.Style can _11_______ be defined as the variation in an individual’s speech which is _12________ by the situation of use. From the definition above, style is described as the variations in language usage. In _13________, style is conditioned by the manner in which an individual makes use of language.Middleton is of the view that style refers to personal idiosyncrasy, the technique of __14______ and Chatman says that style means manner-the manner in which the from executed or the content expressed. From the definitions above, it can be deduced that style is__15______ to every individual or person and it is a product of the function of language as a means of communication.1. A. as B. because C. when D. since2. A. conscience B. consistence C. conclusion D. consensus3. A. otherwise B. further C. moreover D. besides4. A. confined B. confirmed C. confronted D. confided5. A. friendly B. concerned C. specific D. related6. A. instinct B. extinct C. district D. distinct7. A. looked B. referred C. viewed D. defined8. A. expressing B. explaining C. exploring D. exploiting9. A. seduce B. induce C. deduce D. reduce10. A. extinguishes B. separates C. distributes D. distinguishes11. A. yet B. also C. either D. only12. A. occasioned B. influenced C. determined D. demonstrated13. A. contrast B. return C. addition D. essence14. A. exposure B. exposition C. disposition D. expression15. A. subject B. accessible C. unique D. essentialPart IV WritingDirections: Develop each of he following topics into an essay of about 200 words.1. The Importance of Punctuation2. The Standards of an Essay3. Essay Writing and English LearningSection B Extensive Reading and TranslationVariety and Style in Language[1] All of us change out behaviour to fit different situations. We are festive, often noisy at weddings and birthday celebrations, sympathetic at funerals, attentive at lectures, serious and respectful at religious services. Even the clothes we wear on these different occasions may vary. Our table manners are not the same at a picnic as in a restaurant or at a formal dinner party. When we speak with close friends, we are free to interrupt them and we will not be offended if they interrupt us; when we speak to employers, however, we are inclined to hear them out before saying anything ourselves. If we don’t make such adjustments, we are likely to get into trouble, We may fail to accomplish our purpose and we are almost sure to considered ill-mannered or worse. From one point of view, language is behaviour; it is part of the we act. It builds a bridge of communication without which society could not even exist. And like every other kind of behaviour, it must be adjusted to fit different contexts or situations where it is used. When we think of all the adjustments regularly made in any on e language, we speak of language variety. When we think of the adjustments any one person makes in different situations, we use the term style. [2] Among people who are used to a writing system, there is one adjustment everyone makes, They speak one way and write another way. Most speech is in the form of ordinary conversation, where speakers can stop and repeat themselves if they sense that they are being misunderstood. They are constantly monitoring themselves as their message comes across to the listeners. But writers cannot do this. (1) They often monitor what they write, of course, going back over their writing to see that it isclear and unambiguous; but this is before the communication occurs, not while it is happening. Once writers have passed their writing on to someone else, they cannot change it.[3] Speakers can use intonation, stress, and pauses to help make their meaning clear. A simple sentence like “John kept my pencil” may, by a shift in the stress and intonation patterns, single out through contrast whether John rather than someone else kept the pencil, whether John kept rather that just borrowed the pencil, or whether it was a pencil or a pen or something else that he kept.[4] (2) It is true that writers have the special tools of various punctuation marks and sometimes typographical helps like capitals, italic letters, heavy type and the like; but these do not quite take the place of the full resources of the spoken language. The sentence “Cindy only had five dollars” is not likely to be misinterpreted when spoken with light stress and no more than level pitch on “only”, but in writing it could easily be taken to mean something else. To prevent ambiguity, skillful writers could change the word order to “Cindy had only five dollars”if they wanted “only”to modify “five”. They would shift “only” to the beginning 0f the sentence if they wanted it to modify “Cindy”.[5] This simple example shows that good writers do try to avoid ambiguity. (3) As writers, they like a structure that is compact; as speakers, thinking aloud, they produce sentences that are looser, less complex, perhaps even rather jumbled. Notice, for instance, that the first sentence in the first letter to Ann Landers reads, “You have made plenty of trouble for me and I want you to know it.” Like most letters to Ann Landers, this is really talk written down. The sentence contains two ideas and treatsthem as equals. If one is really dependent upon the other, a good writer would have written “I want you to know that you have made plenty of trouble for me.”This is not to deny the effectiveness of the original sentence in this very informal letter. [6] Speech makes more use of contracted forms. “He is” (she is) and “he has” (she has ) become “he’s”(she’s); “cannot” becomes “can’t”; “they are ” become “they’re”; “it is”becomes “’tis”or “it’s”; and with a more noticeable change, “will not”becomes “won’t”. So in the conversational letters to Ann Landers, contractions abound, but in the carefully prepared manuscript speeches of the Reverend Martin Luther King and President Kennedy, there are no contracted forms.[7] Besides the difference between speech and writing there is a difference between formality and informality. A formal message is organized and well-rounded; it usually deals with a serious and important topic. Most formal language is intended to be read. Since there is no opportunity to challenge or question the writer when it is being read, the message has to be self-contained and logically ordered.[8] At the opposite pole is the language of casual and familiar speech among friends and relatives, between people who have some kind of fellow feeling for one another. The speaker or writer is simply being him-or herself. This person knows that the others involved – rarely more than five-see and accept the speaker for what he or she is. (4) The speaker also assumes that the others know him or her well enough to make unnecessary any background information for everything that is used. The writer who signed herself “Weepers Finders”assumed that whoever read the letter would recognize the saying, “Finders keepers, losers weepers.”In contrast to the formal style, this style may be called the casual style.[9] There is also a recognizable midpoint between the formal and the casual. There are situations less rigid than the ceremonial address or the formal written message but also more structured than intimate conversation. These permit some response; there is a certain amount of give and take. Yet each speaker will feel the need to be quite clear, sometimes to explain background for the other person’s benefit or in order to prevent misunderstanding or embarrassment. This middle style is known as the consultative style. It should be noted that the consultative style can allow contractions, but rarely would use slang or the incomplete expressions of the casual style.[10] It should not be thought that speech is always informal and writing always formal. (5) The casual style is spoken more often than it is written, but it is found also in letters between friends or family members, possibly in diaries and journals, and sometimes in newspaper columns. Formal English is typically written but may also be spoken after having first been written down. Much consultative speech is spoken, but a fair amount of writing also has the same need for full explanation even if it is otherwise quite informal.[11] Of course, none of there styles or modes of communication is better than any other. The spoken word and the printed page are simply two different ways to communicate. Some people have thought that formal English is “the best”of the stylistic variants, but it is not. Of course, President Kennedy could not have substituted the quite casual “Nobody’s here today to whoop it up for the Democrats”for “We observe today not a victory of party”; but if he had ever used the formal public speaking style at a dinner table, he would have bored everyone there. Intelligent adjustment to the situation is the real key to the effective use of language.[12] In some respects the English language raises certain problems. In conversation some languages allow an easy distinction between the formal and the informal through their dual system of pronouns. In French, for example, intimacy on the one hand or social distance on the other are overtly marked by a choice between “tu” and “vous”. English lacks such a system, but it does have a complex code of choices of title, title and surname, surname alone, given name alone and nickname, as “Doctor”, “Doctor Stevens”, “Stevens ” , “Charles”, “Charley”, and “Chuck”.[13] Another problem arises because of the two-layered nature of the English vocabulary. One layer consists of short, familiar words largely of native English origin ( house, fire, red, green , make, talk); the other of much longer words, chiefly taken from Latin and French ( residence, domicile, conflagration, scarlet, verdant, manufacture, conversation). But it is an oversimplification to equate the popular words with the casual style and the learned words with the formal style. We must admit that many Americans, especially in bureaucratic contests, are fond of big, windy words-words that are often awkward and sometimes inexact.[14] Although adjustment is the key to good use of the various styles, it poses problems for the student coming to English from another language, It is hard enough to become proficient in just one of the styles without having to switch from one style to another. The causal style, in particular, is not easily acquired by the nonnative speaker. Happily, this problem is not too serious. Native speakers of English are much readier to accept the features of the consultative style in a causal situation than to accept casual features in a noncasual situation. Indeed, many Americans are likely to credit a consultative speaker with greater correctness in using English than theyhave themselves. But even if only this one style is acquired, it is important for learners to recognize the other styles when they meet them in speech or writing and to have some sense of the situations that call for their use.Part A Translate English into ChineseI.Translate the underlined sentences in the above text into Chinese.II.Translate the first and the last paragraph in the above text into Chinese.Part B Translate Chinese into EnglishI. Translate the following sentences into English with the words or phrases inthe passage in Section B.1. 在当代英语中有许多新的语言现象,这些现象并不总是符合公认的语法规则的。

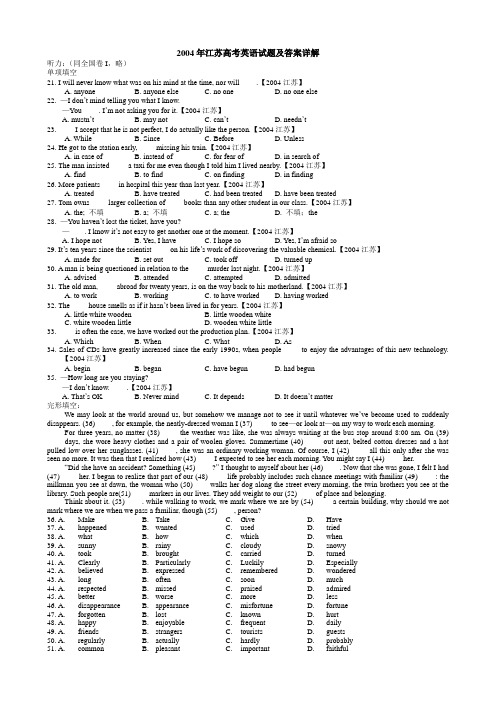

2004年江苏高考英语试题及答案详解听力:(同全国卷I,略)单项填空21. I will never know what was on his mind at the time, nor will ____.【2004江苏】A. anyoneB. anyone elseC. no oneD. no one else22. —I don’t mind telling you what I know.—You ____. I’m not asking you for it.【2004江苏】A. mustn’tB. may notC. can’tD. needn’t23. ____ I accept that he is not perfect, I do actually like the person.【2004江苏】A. WhileB. SinceC. BeforeD. Unless24. He got to the station early, ____ missing his train.【2004江苏】A. in case ofB. instead ofC. for fear ofD. in search of25. The man insisted ____ a taxi for me even though I told him I lived nearby.【2004江苏】A. findB. to findC. on findingD. in finding26. More patients ____ in hospital this year than last year.【2004江苏】A. treatedB. have treatedC. had been treatedD. have been treated27. Tom owns ____ larger collection of ____ books than any other student in our class.【2004江苏】A. the; 不填B. a; 不填C. a; theD. 不填;the28. —You haven’t lost the ticket, have you?—____. I know it’s not easy to get another one at the moment.【2004江苏】A. I hope notB. Yes, I haveC. I hope soD. Yes, I’m afraid so29. It’s ten years since the scientist ____ on his life’s work of discovering the valuable chemical.【2004江苏】A. made forB. set outC. took offD. turned up30. A man is being questioned in relation to the ____ murder last night.【2004江苏】A. advisedB. attendedC. attemptedD. admitted31. The old man, ____ abroad for twenty years, is on the way back to his motherland.【2004江苏】A. to workB. workingC. to have workedD. having worked32. The ____ house smells as if it hasn’t been lived in for years.【2004江苏】A. little white woodenB. little wooden whiteC. white wooden littleD. wooden white little33. ____ is often the case, we have worked out the production plan.【2004江苏】A. WhichB. WhenC. WhatD. As34. Sales of CDs have greatly increased since the early 1990s, when people ____ to enjoy the advantages of this new technology.【2004江苏】A. beginB. beganC. have begunD. had begun35. —How long are you staying?—I don’t know. ____.【2004江苏】A. That’s OKB. Never mindC. It dependsD. It doesn’t matter完形填空:We may look at the world around us, but somehow we manage not to see it until whatever we’ve become used to suddenly disappears. (36) ____, for example, the neatly-dressed woman I (37) ____ to see—or look at—on my way to work each morning.For three years, no matter (38) ____ the weather was like, she was always waiting at the bus stop around 8:00 am. On (39) ____ days, she wore heavy clothes and a pair of woolen gloves. Summertime (40) ____ out neat, belted cotton dresses and a hat pulled low over her sunglasses. (41) ____, she was an ordinary working woman. Of course, I (42) ____ all this only after she was seen no more. It was then that I realized how (43) ____ I expected to see her each morning. You might say I (44) ____ her.“Did she have an accident? Something (45) ____?” I thought to myself about her (46) ____. Now that she was gone, I felt I had (47) ____ her. I began to realize that part of our (48) ____ life probably includes such chance meetings with familiar (49) ____: the milkman you see at dawn, the woman who (50)____ walks her dog along the street every morning, the twin brothers you see at the library. Such people are(51) ____ markers in our lives. They add weight to our (52) ____ of place and belonging.Think about it. (53) ____. while walking to work, we mark where we are by (54) ____ a certain building, why should we not mark where we are when we pass a familiar, though (55) ____, person?36. A. Make B. Take C. Give D. Have37. A. happened B. wanted C. used D. tried38. A. what B. how C. which D. when39. A. sunny B. rainy C. cloudy D. snowy40. A. took B. brought C. carried D. turned41. A. Clearly B. Particularly C. Luckily D. Especially42. A. believed B. expressed C. remembered D. wondered43. A. long B. often C. soon D. much44. A. respected B. missed C. praised D. admired45. A. better B. worse C. more D. less46. A. disappearance B. appearance C. misfortune D. fortune47. A. forgotten B. lost C. known D. hurt48. A. happy B. enjoyable C. frequent D. daily49. A. friends B. strangers C. tourists D. guests50. A. regularly B. actually C. hardly D. probably51. A. common B. pleasant C. important D. faithful52. A. choice B. knowledge C. decision D. sense53. A. Because B. If C. Although D. However54. A. keeping B. changing C. passing D. mentioning55. A. unnamed B. unforgettable C. unbelievable D. unreal阅读理解AHe was the baby with no name. Found and taken from the north Atlantic 6 days after the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, his tiny body so moved the salvage(救援) workers that they called him “our baby.”In their home port of Halifax, Nova Scotia, people collected money for a headstone in front of the baby’s grave(墓), carved with the words: “To the memory of an unknown child.” He has rested there ever since.But history has a way of uncovering its secrets. On Nov. 5, this year, three members of a family from Finland arrived at Halifax and laid fresh flowers at the grave. “This is our baby,”says Magda Schleifer, 68, a banker. She grew up hearing stories about a great-aunt named Maria Panula, 42, who had sailed on the Titanic for America to be reunited with her husband. According to the information Mrs. Schleifer had gathered, Panula gave up her seat on a lifeboat to search for her five children—including a 13-month-old boy named Eino—from whom she had become separated during the final minutes of the crossing. “We thought they were all lost in the sea,” says Schleifer.Now, using teeth and bone pieces taken from the baby’s grave, scientists have compared the DNA from the Unknown Child with those collected from members of five families who lost relatives on the Titanic and never recovered the bodies. The result of the test points only to one possible person: young Eino. Now, the family sees no need for a new grave. “He belongs to the people of Halifax,” says Schleifer. “They’ve taken care of him for 90 years.”Adapted from People, November 25, 200256. The baby traveled on the Titanic with his ____.A. motherB. parentsC. auntD. relatives57. What is probably the boy’s last name?A. Schleifer.B. Eino.C. Magda.D. Panula.58. Some members of the family went to Halifax and put flowers at the child’s grave on Nov. 5, ____.1912 B. 1954 C. 2002 D. 200459. This text is mainly about how ____.A. the unknown baby’s body was taken from the north AtlanticB. the unknown baby was buried in Halifax, Nova ScotiaC. people found out who the unknown baby wasD. people took care of the unknown baby for 90 yearsBDeserts are found where there is little rainfall or where rain for a whole year falls in only a few weeks’ time. Ten inches of rain may be enough for many plants to survive(存活)if the rain is spread throughout the year. If it falls within one or two months and the rest of the year is dry, those plants may die and a desert may form.Sand begins as tiny pieces of rock that get smaller and smaller as wind and weather wear them down. Sand dunes(沙丘) are formed as winds move the sand across the desert. Bit by bit, the dunes grow over the years, always moving with the winds and changing the shape. Most of them are only a few feet tall, but they can grow to be several hundred feet high.There is, however, much more to a desert than sand. In the deserts of the southwestern United States, cliffs(悬崖) and deep valleys were formed from thick mud that once lay beneath a sea more than millions of years ago. Over the centuries, the water dried up. Wind, sand, rain, heat and cold all wore away at the remaining rocks. The faces of the desert mountains are always changing——very, very slowly——as these forces of nature continue to work on the rock.Most deserts have a surprising variety of life. There are plants, animals and insects that have adapted to life in the desert. During the heat of the day, a vision may see very few signs of living things, but as the air begins to cool in the evening, the desert comes to life. As the sun begins to rise again in the sky, the desert once again becomes quiet and lonely.60. Many plants may survive in deserts when ____.A. the rain is spread out in a yearB. the rain falls only in a few weeksC. there is little rain in a yearD. it is dry all the year round61. Sand dunes are formed when____.A. sand piles up graduallyB. there is plenty of rain in a yearC. the sea has dried up over the yearsD. pieces of rock get smaller62. The underlined sentence in the third paragraph probably means that in a desert there is ____.A. too much sandB. more sand than beforeC. nothing except sandD. something else besides sand63. It can be learned from the text that in a desert ____.A. there is no rainfall throughout the yearB. life exists in rough conditionsC. all sand dunes are a few feet highD. rocks are worn away only by wind and heatA. Cook’s Cottage.B. Westfield Centrepoint.C. Sydney Tower.D. Sovereign Hill65. What is the time that Cook’s Cottage is open on Saturday in the summer?A. 11:00 am—2:00 pm.B. 5:00 pm—10:30 pm.C. 9:00 am—5:30 pm.D. 9:00 am—5:00 pm.66. The Anchorage Restaurant is ____.A. in WilliamstownB. in the center of the…C. in AnchorageD. in a Cantonese fishing port67. If you want to buy the best products in Australia, you may call ____.A. 9397 6270B. 9231 9300C. 5331 1944D. 9419 4677DWhoever has made a voyage up the Hudson River must remember the Catskill Mountains. They are a branch of the great Appalachian family, and can be seen to the west rising up to a noble height and towering over the surrounding country. When the weather is fair and settled, they are clothed in blue and purple, and print their beautiful shapes on the clear evening sky, but sometimes when it is cloudless, gray steam gathers around the top of the mountains which, in the last rays of the setting sun, will shine and light up like a crown of glory(华丽的皇冠).At the foot of these mountains, a traveler may see light smoke going up from a village.In that village, and in one of the houses (which, to tell the exact truth, was sadly time-worn and weather-beaten), there lived many years ago, a simple, good-natured fellow by the name of Rip Van Winkle.Rip’s great weakness was a natural dislike of all kinds of money-making labor. It could not be from lack of diligence(勤劳), for he could sit all day on a wet rock and fish without saying a word, even though he was not encouraged by a single bit. He would carry a gun on his shoulder for hours, walking through woods and fields to shoot a few birds or squirrels. He would never refuse to help a neighbor, even in the roughest work. The women of the village, too, used to employ him to do such little jobs as their less helpful husbands would not do for them. In a word, Rip was ready to attend to everybody’s business but his own.If left to himself, he would have whistled(吹口哨) life away in perfect satisfaction; but his wife was always mad at him for his idleness(懒散). Morning, noon, and night, her tongue was endlessly going, so that he was forced to escape to the outside of the house ——the only side which, in truth, belongs to a henpecked husband.68. Which of the following best describes the Catskill Mountains?A. They are on the west of the Hudson River.B. They are very high and beautiful in this area.C. They can be seen from the Appalachian family.D. They gather beautiful clouds in blue and purple.69. The hero of the story is probably ____.A. hard-working and likes all kinds of workB. idle and hates all kinds of jobsC. simple, idle but very dutifulD. gentle, helpful but a little idle70. The underlined words “henpecked husband” in the last paragraph probably means a man who ____.A. likes huntingB. is afraid of hensC. loves his wifeD. is afraid of his wife71. What would be the best title for the text?A. Catskill Mountains.B. A Mountain Village.C. Rip Van Winkle.D. A Dutiful Husband.EEvery year more people recognize that it is wrong to kill wildlife for “sport.” Progress in this direction is slow because shooting is not a sport for watching, and only those few who take part realize the cruelty and destruction.The number of gunners, however, grows rapidly. Children too young to develop proper judgments through independent thought are led a long way away by their gunning parents. They are subjected to advertisements of gun producers who describe shooting as good for their health and gun-carrying as a way of putting redder blood in the veins(血管). They are persuaded by gunner magazines with stories honoring the chase and the kill. In school they view motion pictures which are supposedly meant to teach them how to deal with arms safely but which are actually designed to stimulate(刺激) a desire to own a gun.’Wildlife is disappearing because of shooting and because of the loss of wildland habitat(栖息地). Habitat loss will continue with our increasing population, but can we slow the loss of wildlife caused by shooting? There doesn’t seem to be any chance if the serious condition of our birds is not improved.Wildlife belongs to everyone and not to the gunners alone. Although most people do not shoot, they seem to forgive shooting for sport because they know little or nothing about it. The only answer, then, is to bring the truth about sport shooting to the great majority of people.Now, it is time to realize that animals have the same right to life as we do and that there is nothing fair or right about a person with a gun shooting the harmless and beautiful creatures. The gunners like to describe what they do as character-building, but we know that to wound an animal and watch it go through the agony of dying can make nobody happy. If, as they would have you believe, gun-carrying and killing improve human character, then perhaps we should encourage war.72. According to the text, most people do not seem to be against hunting because ____.A. they have little knowledge of itB. it helps to build human characterC. it is too costly to stop killing wildlifeD. they want to keep wildlife under control73. The underlined word “agony” in the last paragraph probably means ____.A. formB. conditionC. painD. sadness74. According to the text, the films children watch at school actually ____.A. teach then how to deal with guns safelyB. praise hunting as character-buildingC. describe hunting as an exerciseD. encourage them to have guns of their own75. It can be inferred from the text that the author seems to ____.A. blame the majority of peopleB. worry about the existence of wildlifeC. be in favour of warD. be in support of character-building短文改错:This is a story told by my father: “When I was boy, 76. ____________the most exciting thing was when to celebrate the Spring 77. ____________Festival. My grandma was the best cooker in the world 78. ____________but could make the most delicious dishes. One time, I just 79. ____________couldn’t wait for the Spring Festival dinner. As I was 80. ____________about take a piece from a cooked duck, I saw Grandma in 81. ____________the kitchen looking at me. Shake her head, she said, ‘It 82. ____________isn’t a good time to do that, dear.’ At once I apologize 83. ____________and controlled me at my best till the dinner started. You 84. ____________know, that was a dinner we had waited for several month.”85. ____________书面表达:假如你是李晓华,住在江城。

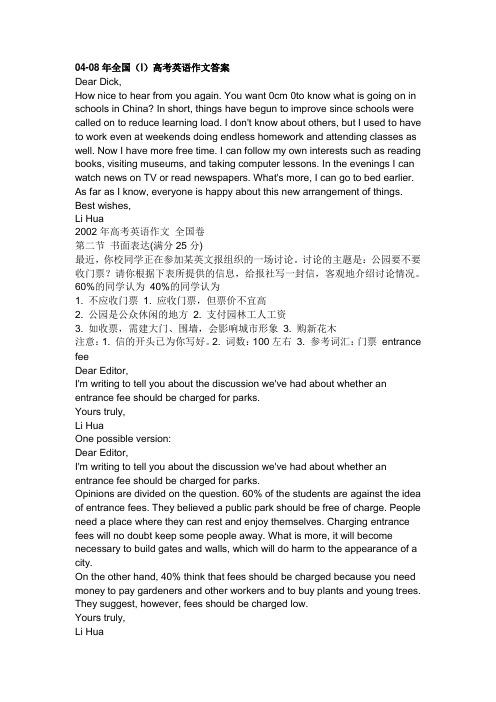

04-08年全国(I)高考英语作文答案Dear Dick,How nice to hear from you again. You want 0cm 0to know what is going on in schools in China? In short, things have begun to improve since schools were called on to reduce learning load. I don't know about others, but I used to have to work even at weekends doing endless homework and attending classes as well. Now I have more free time. I can follow my own interests such as reading books, visiting museums, and taking computer lessons. In the evenings I can watch news on TV or read newspapers. What's more, I can go to bed earlier. As far as I know, everyone is happy about this new arrangement of things. Best wishes,Li Hua2002年高考英语作文全国卷第二节书面表达(满分25分)最近,你校同学正在参加某英文报组织的一场讨论。

讨论的主题是:公园要不要收门票?请你根据下表所提供的信息,给报社写一封信,客观地介绍讨论情况。

60%的同学认为40%的同学认为1. 不应收门票1. 应收门票,但票价不宜高2. 公园是公众休闲的地方2. 支付园林工人工资3. 如收票,需建大门、围墙,会影响城市形象3. 购新花木注意:1. 信的开头已为你写好。

2004年普通高等学校招生全国统一考试英语本试卷分第一卷(选择题)和第二卷(非选择题)两部分。

共150分。

考试时间120分钟。

第一卷(三部分,共115分)第一部分:听力理解(共两节,满分30分)第一节(共5小题;每小题1.5分,满分7.5分)听下面5每段对话后,你将有10例:Howmuchistheshirt?A.£19.15 B.£9.15答案是B.1.Whatdidtheboyfinallyget?A.Acolorfulbike. B.Abluebike.2.Howlongdoesthewomanplantostay?A.Aboutsevendays. B.3.A.B.C.4.A.C.Shewatchedafootballgame.5.A.C.Afterseven.第二节(共听下面5A、B、C三个选项中选出最佳选项。

听每段对话或独白前,你将有5秒钟时间阅读每小题。

听完后,每小题将给出5秒钟的作答时间。

每段对话或独白你将听两遍。

听第6段材料,回答第6、7题。

6.Whatkindofdressdoestheladyget?A.AcottondressSize9. B.AspecialdressSize8. C.AsilkdressSize7. 7.Howmuchisthechange?A.$10. B.$6. C.$16.听第7段材料,回答第8、9题。

8.Whatdidthemandoduringtheseweeks?A.Herodetothecountryseveraltimes.B.Hespenthisholidaysawayfromthecity.C.Hemanagedtovisitthetower.9.Howdoesthemanfeelaboutwhathe’sdone?A.Hefeelsregretful. B.Hefeelscontent. C.Hefeelsdisappointed.听第8段材料,回答第10至12题。

2004年普通高等学校招生全国统一考试英语试题(全国卷IV)本试卷分第I卷(选择题)和第II卷(非选择题)两部分。

——第一卷——第一部分:听力(共两节,满分30分)第一节(共5小题;每小题1.5分,满分7.5分)听下面5段对话。

每段对话后又一个小题,从题中所给的A、B、C三个选项中选出最佳选项,并标在试卷的相应位置。

听完每段对话后,你都有10秒钟的时间来回答有关小题和阅读下一小题。

每段对话仅读一遍。

例:How much is the shirt?A.£19.15.B.£9.15.C.£9.18.1.What does the man mean?A.He wants to know the time.B.He offers to give a lecture.C.He agrees to help the woman.2.What will the man probably do after the conversation?A.Wait there.B.Find a seat.C.Sit down.3.Who are the speakers talking about?A.An actor.B.A writer.C.A tennis player.4.Where does the conversation most probably take place?A.On a farm.B.In a restaurant.C.In a market.5.What does the man agree to do after a while?A.Take a break.B.Talk about his troubles.C.Meet some friends.第二节(共15小题;每小题1.5分,满分22.5分)听下面5段对话或独白。

每段对话或独白后有几个小题,从题中所给的A、B、C三个选项中选出最佳选项,并标在试卷的相应位置。

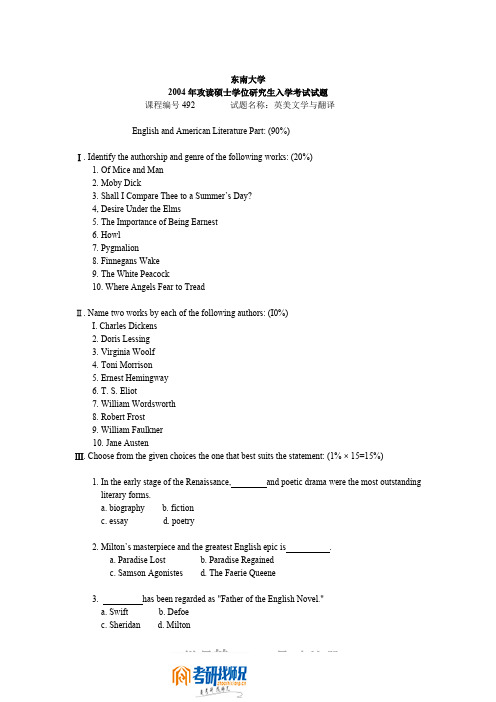

东南大学2004年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试题English and American Literature Part: (90%)Ⅰ. Identify the authorship and genre of the following works: (20%)1. Of Mice and Man2. Moby Dick4, Desire Under the Elms5. The Importance of Being Earnest6. Howl7. Pygmalion8. Finnegans Wake9. The White Peacock10. Where Angels Fear to TreadⅡ. Name two works by each of the following authors: (I0%)I. Charles Dickens2. Doris Lessing3. Virginia Woolf4. Toni Morrison5. Ernest Hemingway6. T. S. Eliot7. William Wordsworth8. Robert Frost9. William Faulkner10. Jane AustenⅢ. Choose from the given choices the one that best suits the statement: (1% × 15=15%)1. In the early stage of the Renaissance, and poetic drama were the most outstandingliterary forms.a. biographyb. fictionc. essayd. poetry2. Milton’s masterpiece and the greatest English epic is.a. Paradise Lostb. Paradise Regainedc. Samson Agonistesd. The Faerie Queene3. has been regarded as "Father of the English Novel."a. Swiftb. Defoec. Sheridand. Milton4. , Byron’s masterpiece, is a poem based on a traditional Spanish legend of a great lover and seducer of women.a. Cainb. Oriented Talesc. Don Juand. The Prisoner of Chillon5. Which of the following is not a novel by Jane Austen?a. Pride and Prejudiceb. Sense and Sensibilityc. Northanger Abbeyd. Jane Eyre6. “She stiffened a little on the kerb, waiting for Durtnall’s van to pass. A Charming woman, Scrope Purvis thought her (knowing her as one does know people who live next door to one in Westminster); a touch of the bird about her, of the jay, blue-green, light, vivacious, though she was over fifty, and grown very white since her illness. There she perched, never seeing him, waiting to cross, very, upright.”The above paragraph may be taken froma. Sons and Loversb. Blissc. Ulyssesd. Mrs. Dalloway7. Which of the following is not a novel by Mark Twain?a. The Gilded Ageb. The Adventure of Tom Sawyerc. The Adventure of Huckleberry Finnd. The Leaning Tower8. “The apparition of these faces in the crowd; Petals on a wet, black bough.”The above two lines a re most probably taken from a poem bya. Ezra Poundb. Robert Frostc. Sylvia Plathd. Walt Whitman9. “Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!”The above lines are most probably taken from .a. Ode on a Grecian Urnb. Ode to the West Windc. Ode to Libertyd. Ode to Nightingale10. “Thou who didst waken from his summer dreams The blue Mediterranean, where he lay,Lulled by the coil of his crystalline streams”Who does the poet refer to by saying "his summer dreams" in the first line?a. The poet himselfb. The west windc. The Mediterraneand. England11. is a typical feat ure of Swift’s writings.a. Bitter satireb. Elegant stylec. Casual narrationd. Psycho-analysis12. “My dear, you flatter me. I certainly have had my share of beauty, but I do not pretend tobe anything extraordinary, now. When a woman has five gown-up daughters, she ought to give over thinking of her own beauty.”The above passage is taken froma. Jane Eyreb. Wuthering Heightsc. Pride and Prejudiced. A Portrait of a Lady’s13. Mark Twain was the pseudonym of .a. Samuel Langhome Clemensb. William Sydney Porterc. Cutter Belld. Wallace Stevens14. The name of Robert Browning is often associated with the term .a. critical realismb. blank versec. oded. dramatic monologue15. has been regarded as the forerunner of the English modem poetry.a. Ezra Poundb. T.S. Eliotc. William Butler Yeatsd. Philip LarkinIV. Define the following terms: (5% x3- 15%)1. Metaphysical poetry2. Stream-of-Consciousness3. Black HumorV. Answer the following questions: (5% 12=10%)I. What is the symbolic meaning of “the west wind” in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ode to theWest Wind”?2. In what sense is Tess’ story tragic?1. When You Are Old by William Butler YeatsWhen you are old and grey and full of sleep,And nodding by the fire, take down this book,And slowly read, and dream of the soft lookYour eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;How many loved your moments of glad grace,And loved your beauty with love false and true,But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,And loved the sorrows of your changing face;And bending down beside the glowing bars,Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fledAnd paced upon the mountains overheadAnd hid his face amid a crowd of stars.2. (Excerpts from "The Decay of Friendship" by Dr. Samuel Johnson)3. (Excepts from Heat of Darkness by Joseph Conrad)Part Two Translation (60)Note: Write your translation on the Answer Sheet.I. Translate the following into Chinese: ( 30 )II. Translate the following into English:(30)1.平则门外,有一道护城河。

东南大学

2004年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试题

试题编号:318 试题名称:基础英语与写作

Ⅰ. Reading Comprehension (50 points)

真题1(东南大学2004年研)Directions: Below each of the following passages, you will find questions or incomplete statements about the passage. Each statement or question is followed by lettered words or expressions. Select the word or expression that most satisfactorily completes each statement or answers each question in accordance with the meaning of the passage. On your answer sheet, blacken the letter A,

B, C or D for the answer you choose.

Passage 1

In the 1350s poor countrymen began to have cottages and gardens which they could call their own. Were these fourteenth-century peasants, then, the originators of the cottage garden? Not really: the making and planting of small mixed gardens had been pioneered by others, and the cottager had at least two good examples which he could follow. His garden plants might and to some extent did come from the surrounding countryside, but a great many came from the monastery gardens. As to the general plan of the small garden, in so far as it had one at all, that had its origin not in the country, but in the town.

The first gardens to be developed and planted by the owners or tenants of small houses, town cottages as it were, were almost certainly those of the suburbs of the free cities of Italy and Germany in the early Middle Ages. Thus the suburban garden, far from being a descendant of the country cottage garden, is its ancestor; and older, in all probability, by about two centuries. On the face of it a paradox, in fact this is really logical enough; it was in such towns that there first emerged a class of man who was free and who, without being rich, owned his own small house: a craftsman or tradesman protected by his guild from the great barons, and from the petty ones too. Moreover, it was in the towns, rather than in the country, where the countryside provided herbs and even wild vegetables, that men needed to cultivate pot-herbs and salads. It was also in the towns that there existed a demand for market-garden produce.

London lagged well behind the Italian, Flemish, German and French free cities in this bourgeois progress towards the freedom of having a garden; yet, as early as the thirteenth century, well before the Black Death, Fitz Steven, biographer of Thomas a Becket, was writing that, in London: ‘On all sides outside the houses of the citizens who dwell in the suburbs there are adjoining gardens planted with trees, both spacious and pleasing to the sight’.

Then there is the monastery garden, quoted often as a ‘source’ of the cottage garden in innumerable histories of gardening. The gardens of the great religious establishments of the eighth and ninth centuries had two origins: St. Augustine, copying the Greek ‘academe’ did his teaching in a small garden presented to him for that purpose by a rich friend; thus the idea of a garden-school, which began among the Greek philosophers, was carried on by the Christian church. In the second place, since one of the charities undertaken by most religious orders was that of healing, monasteries and nunneries needed a garden of medicinal herbs. Such physic gardens were soon supplemented by vegetable, salad and fruit gardens in those monasteries which enjoined upon their members the duty of raising their own food, or at least a part of it. They tended next to develop, willy-nilly into flower gardens simply many of the herbaceous plants grown for medicinal purposes, or for their fragrance as strewing herbs, had pretty flowers--for example, violets, marjoram, pinks, primroses, madonna lilies and roses. In due course these flowers came to be grown for their own sakes, especially since some of them, lilies and roses notably, had a ritual or religious significance of their own. The madonna lily had been Aphrodite’s symbolic flower, it became Mary’s ; yet’ its first association with horticulture was economic; a salve or ointment was made from the bulb.

Much earlier than is commonly realized, certain monastic gardeners were making remarkable progress in

第 1 页共14 页。