环艺设计外文翻译--绿色景观规划的基础设施(节选自书籍)

- 格式:doc

- 大小:3.74 MB

- 文档页数:20

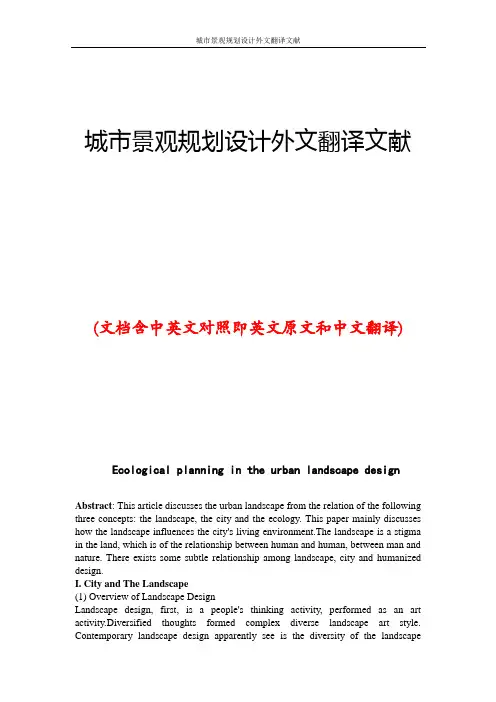

城市景观设计中的生态规划Ecological planning in the urban landscape design城市景观设计中的生态规划Ecological planning in the urban landscape design Abstract: This article discusses the urban landscape from the relation of the following three concepts: the landscape, the city and the ecology. This paper mainly discusses how the landscape influences the city's living environment.The landscape is a stigma in the land, which is of the relationship between human and human, between man and nature. There exists some subtle relationship among landscape, city and humanized design.key word:Urban landscape、Living environment、HumanizationI. City and The Landscape(1) Overview of Landscape DesignLandscape design, first, is a people's thinking activity, performed as an art activity.Diversified thoughts formed complex diverse landscape art style. Contemporary landscape design apparently see is the diversity of the landscape forms,in fact its essence is to keep the closing up to the natural order system, reflected the more respect for human beings, more in-depth perspective of the nature of human's reality and need, not to try to conquer the nature.it is not even imitating natural, but produce a sense of belonging. Landscape is not only a phenomenon but the human visual scene. So the earliest landscape implications is actually city scene. Landscape design and creation is actually to build the city.(2) The Relationship Between Landscape and UrbanCity is a product of human social, economic and cultural development, and the most complex type. It is vulnerable to the artificial and natural environmental conditions of interference. In recent decades, with worldwide the acceleration of urbanization, the urban population intensive, heavy traffic, resource shortage, environment pollution and ecology deterioration has become the focus of attention of the human society. In the current environment condition in our country, the problem is very serious. and in some urban areas, the pollution has quite serious, and greatly influenced and restricts the sustainable development of the city.Landscape is the relationship between man and man, man and nature. This is, in fact, a kind of human living process. Living process is actually with the powers of nature and the interaction process, in order to obtain harmonious process. The landscape isthe result of human life in order to survive and to adapt the natural. At the same time, the living process is also a process of establishning harmonious coexistence. Therefore, as a colony landscape, it is a stigma of the relationship between man and nature.II the city landscape planning and design(1) city landscape elementsThe urban landscape elements include natural landscape and artificial landscape. Among them, the natural landscape is mainly refers to the natural scenery, such as size hills, ancient and famous trees, stone, rivers, lakes, oceans, etc. Artificial landscape are the main cultural relics, cultural site, the botanical garden afforestation, art sketch, trade fairs, build structure, square, etc. These landscape elements must offer a lot of examples for creating high quality of the urban space environment. But for a unique urban landscape, you must put all sorts of landscape elements in the system organization,and create an orderly space form.(2)the urban landscape in the planningThe city is an organic whole, which is composed with material, economy, culture, and society.To improve the urban environment is a common voice.The key of the urban landscape design is to strengthen urban design ideas, strengthen urban design work. and blend urban design thought into the stages of urban planning. The overall urban planning in the city landscape planning is not to abandon the traditional garden, green space planning, but the extension and development of it.Both are no conflict, but also cannot be equal.In landscape planningof city planning, we should first analysis the urban landscape resources structure, fully exploit landscape elements which can reflect the characteristics of urban.Consider carefully for the formation of the system of urban landscape.III ecological planning and urban landscape (1) the relationship of urban landscape and ecological planning Landscape ecology is a newly emerged cross discipline, the main research space pattern and ecological processes of interaction, its theme is the fork the geography and ecology. It's with the whole landscape as the object, through the material flow, energy flow and information flowing the surface of the earth and value in transmission and exchange, through the biological and the biological and the interaction between human and transformation, the ecological system principle and system research methods of landscape structure and function.the dynamic change of landscape has interaction mechanism, the research of the landscape pattern, optimizing the structure, beautify the reasonable use and the protection, have very strong practicability. Urban ecological system is a natural, economic and social composite artificial ecosystem, it including life system, environment system, with a complex multi-level structure, can be in different approaches of human activity and the mutual relationship between the city and influence. Urban environment planning guidance and coordination as a macro department interests, optimizing the allocation of land resources city, reasonable urban space environment organization the important strategic deployment, must have ecological concept. Only to have the ecological view, to guide the construction of the city in the future to ecological city goal, to establish the harmonious livingenvironment. In recent years, landscape planning in urban landscape features protection and urban environment design is wide used.(2) landscape in the living environment of ecological effectLandscape as a unit of land by different inlaid with obvious visual characteristics of the geographic entities, with the economic, ecological and aesthetic value, the multiple value judgment is landscape planning and management foundation. Landscape planning and design always is to create a pleasant landscape as the center. The appropriate human nature can understand the landscape for more suitable for human survival, reflect ecological civilization living environment, including landscape, building economy, prudent sex ecological stability, environmental cleanliness, space crowded index, landscape beautiful degree of content, the current many places for residential area of green, static, beauty, Ann's requirement is the popular expression. Landscape also paid special attention to the spatial relationship landscape elements, such as shape and size,density and capacity, links, and partition, location and of sequence, as their content of material and natural resources as important as quality. As the urban landscape planning should pay attention to arrange the city space pattern, the relative concentration of the open space, the construction space to density alternate with; In artificial environment appeared to nature; Increase the visual landscape diversity; Protect the environment MinGanOu and to promote green space system construction.(3) the urban landscape and ecological planning and design of the fusion of each other.The city landscape and ecological planning design reflects human a new dream, it is accompanied by industrialization and after the arrival of the era of industrial and increasingly clear. Natural and cultural, design of the environment and life environment, beautiful form and ecological functions of real comprehensive fusion, the landscape is no longer a single city of specific land, but let the ablation, to thousands; It will let nature participate in design; Let the natural process with every one according to daily life; Let people to perception, experience and care the natural process and natural design.(4) the city landscape ecological planning the humanized design1. "it is with the person this" design thought Contemporary landscape in meet purpose at the same time, more in-depth perspective on human of the nature of reality and needs. First performance for civilian design direction, application of natural organic materials and elastic curve form rich human life space. Next is the barrier-free design, namely no obstacle, not dangerous thing, no manipulation of the barrier design. Now there have been the elderly, the disabled, from the perspective of the social tendency, barrier-free design ideas began to gain popularity, at the same time for disadvantaged people to carry on the design also is human nature design to overall depth direction development trend. "It is with the person this" the service thoughts still behave in special attention to plant of bright color, smell good plant, pay attention to ZuoJu texture and the intensity of the light. The detail processing of considerate more expression of the concern, such as the only step to shop often caused visual ignored and cause staggered, in order to avoid this kind of circumstance happening, contemporary landscape sites do not be allowed under 3 steps; And as someresidential area and square in the bush set mop pool, convenient the district's hygiene and wastewater recycling water. "It is with the person this" the service thoughts in many ways showed, the measure of the standard is human love.1. 1 human landscape design concept is human landscape design is to point to in landscape design activity, pay attention to human needs, in view of the user to the environment of the landscape of a need to spread design, which satisfied the user "physiological and psychological, physical and mental" multi-level needs, embodies the "people-oriented" design thought. Urban public space human landscape design, from the following four aspects to understand:1. 1.1 physical level of care. Human landscape design with functional and the rationality of design into premise condition, pay attention to the physical space reasonable layout and effective use of the function. Public space design should not only make people's psychology and physiology feel comfortable, still should configuration of facilities to meet people's complex activities demand1. The level of caring heart 1.2 Daniel. In construction material form of the space at the same time, the positive psychology advocate for users with the attention that emotion, and then make the person place to form the security, field feeling and belonging.1. 1.3 club will level of care. Emphasizes the concern of human survival environment, the design in the area under the background of urban ecological overall planning and design, to make the resources, energy rationally and effectively using, to achieve the natural, social and economic benefits of the unity of the three.1. 1.4 to a crowd of segmentation close care. Advocate barrier-free design, and try to meet the needs of different people use, and to ensure that the group of mutual influence between activities, let children, old people, disabled people can enjoy outdoor public the fun of life.1. 2 and human landscape design related environmental behavior knowledge the environment behavior is human landscape design, the main research field, pay attention to the environment and people's explicit behavior and the relationship between the interaction, tried to use the psychology of the some basic theory, methods researchers in the city and architecture in activities and to the environment of the response, and the feedback the information can be used to guide the environment construction and renovation. Western psychologist dirk DE Joan to put forward the boundary effect theory. He points out that the edge of space is people like to stay area, also is the space of the growth of the activity area [3]. Like the urban space, the margin of the wood, down the street, and the rain at the awning, awnings, corridor construction sunken place, is people like the place to stay. At the edge of space, and other people or organizations to distance themselves are is better able to observe the space of the eyes and not to be disturbed. "Man seeth" is the person's nature. A large public space are existing "the man seeth" phenomenon: the viewer consciously or unconsciously observation, in the space in front of the all activities. At the same time, some of the people with strong performance desire, in public space in various activities to attract the attention of others, so as to achieve self-fulfillment cheerful. The seemingly simple "man seeth" phenomenon, but can promote space moreactivities production. For example, for a walk of pedestrians may be busy street performance and to join the ranks of the show attracts, with the strange because the audience is the sight of the activities of the wonderful and short conversation, art lovers of the infection by environmental atmosphere began to sketch activities. Environmental design, according to environmental behavior related knowledge, actively create boundary space provide people stay, rest, the place of talking to facilitate more spaceThe Landscape Urbanism exhibition contained an international survey of public urban spaces by designers including Adriaan Geuze/West 8, Michael Van Valkenburgh, Patrick Schumacher, Alex Wall, and several Barcelona landscape architects (such as Enric Batlle and Joan Roig, who completed Trinitat Cloverleaf Park in a highway intersection for the 1992 Olympics). American exhibitors included Corner and Mathur, Waldheim’s teachers from Penn, Mapillero/ Pollack from New York, Conway-Schulte of Atlanta Olympics fame, and Jason Young/Omar Perez/Georgia Daskalakis/Das: 20 from Detroit. Corner’s premiated but sadly unbuilt Greenport Harborfront, Long Island Project (1997), stood out in this show. His office, Field Operations, proposed creating a sense of urban activity around the annual raising and lower-ing of the town’s ancient sailing ship Stella Maris up and down a newly created slip, with a historic, children’s carousel housed in an adjacent band shell. Corner envisioned this staged, biannual event as an attractor for peo-ple, the press, and media, who would flock to the town in its off season, inhabiting the newly created commons on the harbor front to watch the ship’s spectacular movements. In the winter, the ship would become a monumental, sculptural presence lit at night in the center of the small port’s commons; in the summer it would return to its accustomed quayside, where its masts would tower above the rooftops. 21Corner’s project in the Landscape Urbanism exhibition illustrates his concept of a “performative” urbanism based on preparing the setting for programmed and unprogrammed activi-ties on land owned in common. The three projects presented in Stalking Detroit provide further insights into this emerging strategy, and each is paired with a commentary by a landscape architect. 22 The Waldheim and Marli Santos-Munne Studio proposes the most comprehensive of landscape urbanism practices in “Decamping Detroit” (104–122). They advocate a four-stage decommissioning of land from the city’s legal control: “Dislocation” (disconnection of services), then “Erasure” (demolition and jumpstarting the native landscape ecology by dropping appropriate seeds from the air), then “Absorption” (ecological reconstitution of part of the Zone as woods, marshes, and streams), and then “Infiltration” (the recolonization of the landscape with heteropic village-like enclaves). As Corner writes in his commentary, this project “prompts you to reflect on the reversal of the traditional approach to colonization, from building to unbuilding, removal, and erasure” (122). This reversal of normal processes opens the way for a new hybrid urbanism, with dense clusters of activity and the reconstitution of the natural ecology, starting a more ecologically balanced, inner-city urban form in the void.All of Landscape Urbanism’s triumphs so far have been in such marginal and“unbuilt” locations. These range from Victoria Marshall and Steven Tupu’s premiated design for ecological mudflats, dunes, canals, and ramps into the water in the Van Alen East River Competition (1998), which would have simultaneously solved the garbage disposal problem of New York and reconstituted the Brooklyn side of the East River as an ecology to be enjoyed as productive parkland. 23 In the Downside Park, Toronto Competition (2000), Corner, with Stan Allen, competed against Tschumi, Koolhaas (who won), and two other teams, pro-viding a showcase for their “Emerging Ecologies” approach. 24 This was further elaborated in the Field Operations’ design that won first place in the Freshkills Landfill Competition, Staten Island (2001). Together with Stan Allen (now Dean at Princeton), Corner analyzed the human, natural, and technological systems’ interaction with characteristic aerial precision. Field Operations presented the project as a series of overlaid, CAD-based activity maps and diagrams, that stacked up as in an architect’s layered axonometric section. These layered drawings clearly showed the simultaneous, differentiated activities and support systems planned to occupy the site over time, creating a diagram of the complex settings for activities within the reconstituted ecology of the manmade landfill. 25 In the Freshkills competition, Mathur and da Cunha’s used a similar approach but emphasized the shifting and changing eco-logical systems of the site over time, seeking suitable places for human settlements including residences. In the first conference on Landscape Urban-ism at the University of Pennsylvania in April 2002, Dean Garry Hack (who coauthored Kevin Lynch’s 1984 third edition of Site Planning) questioned the interstitial and small-scale strate-gies of participants (asking, “Hyper-urbanization: Places of Landscape Architecture?”). Mohsen Mostafavi, the Chairman of the AA, delivered the keynote speech, “Landscape as Urban-ism,” showing the Barcelona-style, large-scale, infrastructural work of the first three years of the AA Landscape Urbanism program. 26Dean Hack identified a key problem for landscape urbanists as they face the challenge of adapting to complex urban morphologies beyond that of an Anglo-Saxon village and its commons. Rifle ranges, the spectacle of the “Devil’s Night,” and the “Staging of Vacancy” suggested in Stalking Detroit may prove to be inadequate responses in an age when many Europeans and Americans live in idyllic, landscaped suburbs. Suburbanites are willing to pay a premium to visit staged urban spectacles. These spectacles can take the form of the Palio annual horse race in Siena, a parade on Disneyworld’s Main Street, or a week-end in a city-themed Las Vegas casino like The Venetian, with its simulation of the Grand Canal as a mall on the third floor above the gaming hall. The desire for the city as compressed hustle and bustle in small spaces remains strong. Even in ruined downtown Detroit, small ethnic enclaves like “Greek Town” or “Mexico Town” satisfy this demand, in the midst of the void. Commercial interests like Disney clearly understand how to stage an event and create an urban street spectacle based in a village-like setting. As yet, the dense urban settings of Hong Kong or New York, or even mid-rise urban morphologies like Piano’s eco-logically sensitive Potsdam Platz, Berlin (1994–1998), do not feature as part of this performative urbanism. Stalking Detroit does not begin to deal with the issue of urban morphologies or the emergence of settlement patterns over time. Itconcentrates on their disappearance and erasure. The problem of this approach is its amnesia and blindness to preexisting structures, urban ecologies, and morphological patterns. A common ground is useless without people to activate it and to surround it, to make it their commons. Housing, however transient or distant, is an essential part of this pattern of relationship, whether connecting to a village green or a suburban mall. With this logic, the International Building Exhibition in Berlin of 1984–1987 sponsored the recolonization of vacant inner-city lots with high-density, low-rise infill blocks in anticipation of the construction of Potsdamer Platz and the demolition of the Berlin Wall. Adaptive reuse, as in the conversion of dockland warehouses or multi-story factories to lofts and apartments, is another successful strategy that has provided housing and workplaces to activate inner-city areas. These approaches have been slowly applied with some success in other American empowerment zones, such as those in the South Bronx and Harlem. Chicago, also a viciously segregated city, is rising slowly from its ashes; North Michigan Avenue functions as a great urban boulevard, comparable to Fifth Avenue in New York, populated with many strange hybrid skyscraper towers containing malls, department stores, hotels, offices, apartments, and parking lots (a form pioneered there by Skidmore Owings and Merill’s mixed-use Hancock Tower in 1966). Even in Detroit, Henry Ford’s grand-son is rebuilding the Ford River Rouge Plant as a model, hybrid, “green” facility. 27Landscape urbanists are just beginning to battle with the thorny issue of how dense urban forms emerge from landscape and how urban ecologies support performance spaces. The lin-ear organization of the village main street leading to a common space, with its row-house typology and long thin land subdivisions, is one of the oldest global urban patterns, studied by the pioneer urban morphologist Michael R.G. Conzen in the 1930s. 28 Urban morphologists look for the emergence of such characteristic linkages between activity and spatial patterns in human settlements. Such linkages, when repeated over time, form islands of local order structuring the larger pat-terns of global, ecological, and economic flows. 29 The pattern of the town square and approach street is another, more formal example of an urban morphology, focusing on a sin-gle center, setting up the central agora or forum as in a Greek or Roman city grid (and echoed in the courtyard-house typology). The Islamic city, with its irregular cul-de-sac structure, accommodating the topography, emerged as a variation on this classical model, with the mosque, bazaar, school, and baths replacing the forum and temples at the center. 30 Medieval European cities, also with cul-de-sacs, but based on a row-house typology, formed another morphological variation of the classical city, with market halls and cathedrals on the city square. In The Making of the American Landscape (1990), edited by Michael P. Conzen of the University of Chicago, contributors illustrate how the morphology of the city shifted from a dense single center to a “machine city.” This bipolar structure was based on railways creating a regional division between dense center and suburban villa edge (involving the separation of consumption from production, industry from farmland, rich from poor, etc.). In the second phase, the “machine city” of the Modernists (best exemplified by the morphology of Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse (1933) with its slab blocks and towers set in park-land) replaced the old, denseIndustrial City. With the advent of the automobile, a third morphology emerged in a multi centered pattern and isolated, pavilion, building typologies, a pattern that was further extended by airports on the regional periphery. Joel Garreau identified this as the postmodern “Edge City” morphology of malls, office parks, industrial parks and residential enclaves in 1991. 31In Europe Cedric Price jokingly described these three city morphologies in terms of breakfast dishes. There was the traditional, dense, “hard-boi led egg” city fixed in concentric rings of development within its shell or walls. Then there was the “fried egg” city, where railways stretched the city’s perimeter in linear, accelerated, space-time corridors out into the landscape, resulting in a star shape. Finally there was the postmodern city, the “scrambled egg city,” where everything is distributed evenly in small granules or pavilions across the landscape in a continuous network. Koolhaas and the younger Dutch groups like MVRDV continue this tra-dition of urban, morphological analysis with a light, analogical touch. The organizing group of the 2001 International Conference of Young Planners meeting in Utrecht, for instance, used Price’s metaphors to study the impact of media and communications on the city.32 Franz Oswald , from the ETH Zurich Urban Design program, also examines the “scrambled egg” network analogy in the Synoikos and NEt city Projects . These projects study the distribution of urban morphologies in central Switzerland as layers in a cultural, commercial, industrial and informational matrix within the extreme Alpine topography and its water-sheds. 33 Schumacher, at the AA’s Design Research Laboratory, has also extended his work from Stalking Detroit into an investigation of the role of personal choice in a dynamic, typo-logical, and morphological matrix forming temporary housing structures in the city. 34 His colleagues in the Landscape Urbanism program have also shifted to a more urban orient-tion, studying Venice and its lagoon.This rationalist, morphological and landscape tradition seems to be centered in Venice. Here Bernardo Secchi and Paola Viganò continue the typo-logical analysis begun in the 1930s, but now applied to the voids of the post-modern city-region, the “Reverse City.” Viganò’s La Città Elementare (The Elementary City, 1999; it deserves translation into English) is exemplary of this larger European Landscape Urbanism movement. For Viganò, large landscape infrastructures form the basis for later urbanization. Le Corbusier’s work at the Agora in Chandigarh is exemplary in its monumental manipulation of the terrain, orientation to the regional landscape, and attempt to form an urban space. Xaveer de Geyter Architects’ A fter Sprawl (2002), with its fifty-by-fifty kilometer “Atlases” of European cities made by various university groups, gives an easily accessible cross section of a wider landscape urbanism and morphological network linked to Venice. In America, Carol Willis in Form Follows Finance (1995) and my colleague at Columbia Urban Design, Brian McGrath, have created a portrait of one building ecology, the sky-scraper, and its typological evolution in the flows of New York in Time formations(2000), viewable at the Sky-scraper Museum website.Activities of generation, the rich visitors sensory experiences2. The design of the sustainable developmentSustainable development principle, it is the ecology point of view, to the city system analysis, and with the minimum the minimal resource consumption to satisfy the requirements of the human, and maintain the harmony of human and the natural environment, guarantee the city several composition system-to protect natural evolution process of open space system and the urban development system balance. People are to landscape 'understanding of the contemporary landscape design and the function to reflect, have been completely out of the traditional gardening activities, the concept of landscape art value unconsciously and ecological value, the function value, cultural value happened relationship, landscape art category than before more pointed to the human is closely linked with the various aspects, become more profound and science. Contemporary landscape also actively use new technology to improve the ecological value. Such as the use of solar energy for square garden, lighting and sound box equipment supply electricity; The surface water "cycle" design concept, collecting rainwater for irrigation and waterscape provides the main resources; Using the principle of the construction of the footway, buoys that environmental protection level a kiss and interesting. And by using water scene drought, landscape water do ecology (ecological wetland), ecological XiGou "half natural change" landscape humanized waterscape design, avoid the manual water scene is the difficulty of the later-period management, but in the water since the net, purifying environment and promote biodiversity play a huge role. Therefore, to experience the landscape will surely is contained to nature and the tradition, to human compatibility.The urban landscape the principles of sustainable development and implementation details:2.1 the efficiency of land use principle for land to the survival of humans is one of the most effective resources, especially in China's large population, land resources are extremely deficient, urbanization rapidly increase background, the reasonable efficient use of land, is that we should consider an important issue. For the city landscape is concerned, how to productive use of the land? Three-dimensional is efficient land use is the most effective means. The urban landscape "three-dimensional to take" ideas contains the following six aspects of meaning. (1) in the limited on land, as much as possible to provide activity places, form the three-dimensional multi-layer activities platform landscape environment. (2) improve afforestation land use efficiency, in the same land, adopt appropriate to niche by, shrubs and trees of co-existence and co-prosperity between three-dimensional planting layout. (3) to solve the good man, for the contradiction in green, the green space and human activity space layout of the interchanges. (4) the up and down or so, all sides three-dimensional view observation, increased the landscape environment the visual image of the visual rate. (5) from the static landscape to dynamic landscape. 6 not only from the traditional technology of modern technology to introduce more (such as crossing bridge, light rail, electric rail, etc), show a colorful three-dimensional space.2.2 energy efficiency principle along with the rapid development of urbanization, China's energy demand is more and more big, the energy gap also more and more big.。

. Cover 封面 -Content 目录 -Design Explanation设计说明-Master Plan总平面-Space Sequence Analysis景观空间分析-Function Analysis功能分析-Landscape Theme Analysis景观景点主题分析图-Traffic Analysis交通分析-Vertical Plan竖向平面布置图-Lighting Furniture Layout灯光平面布置示意图-Marker/Background Music/Garbage Bin标识牌/背景音乐/垃圾桶布置图-Plan 平面图 -Hand Drawing 手绘效果图 -Section剖面图-Detail 详图 -Central Axis中心公共主轴-Reference Picture参考图片-Planting Reference Picture植物选样-材料类: -aluminum 铝 -asphalt沥青-alpine rock轻质岗石-. boasted ashlars粗凿-ceramic 陶瓷、陶瓷制品-cobble 小圆石、小鹅卵石-clay 粘土 -crushed gravel碎砾石-crushed stone concrete碎石混凝土 -crushed stone碎石 -cement 石灰 -enamel 陶瓷、瓷釉 -frosted glass磨砂玻璃 -grit stone/sand stone砂岩 -glazed colored glass/colored glazed glass彩釉玻璃 -granite花岗石、花岗岩 -gravel卵石 -galleting碎石片 -ground pavement material墙面地砖材料 -light-gauge steel section/hollow steel section薄壁型钢 -light slates轻质板岩 -lime earth灰土 -masonry 砝石结构 -membrane张拉膜、膜结构-membrane waterproofing薄膜防水-. mosaic 马赛克 -quarry stone masonry/quarrystone bond粗石体-plaster 灰浆 -polished plate glass/polished plate磨光平板玻璃-panel 面板、嵌板 -rusticated ashlars粗琢方石-rough rubble粗毛石-reinforcement 钢筋 -设施设备类:-accessory channel辅助通道-atrium门廊-aisle走道、过道-avenue 道路 -access 通道、入口 -art wall艺术墙-academy 科学院 -art gallery画廊-arch 拱顶 -archway 拱门 -arcade 拱廊、有拱廊的街道-axes 轴线 -air condition空调-. aqueduct 沟渠、导水管-alleyway小巷-billiard table台球台-bed 地基 -bedding cushion垫层-balustrade/railing栏杆 -byland/peninsula半岛 -bench 座椅 -balcony 阳台 -bar-stool酒吧高脚凳-beam梁 -plate beam板梁-bearing wall承重墙-retaining wall挡土墙-basement parking地下车库-berm 小平台 -block 楼房 -broken-marble patterned flooring碎拼大理石地面-broken stone hardcore碎石垫层-curtain wall幕墙-cascade 小瀑布、叠水-corridor 走廊 -. couryard内院、院子-canopy 张拉膜、天篷、遮篷-coast 海岸 -children playground儿童活动区-court法院-calculator计算器 -clipboard 纤维板 -cantilever悬臂梁 -ceiling 天花板 -carpark停车场-carpet地毯-cafeteria 自助餐厅 -clearage开垦地、荒地-cavern 大洞穴 -dry fountain旱喷泉-driveway车道-vehicular road机动车道-depot 仓库、车场 -dry fountain for children儿童溪水广场-dome圆顶 -drain排水沟-drainage下水道-. drainage system排水系统-discharge lamp放电管-entrance plaza入口广场-elevator/lift电梯 -escalator 自动扶梯 -flat roof/roof garden平台-fence wall围墙、围栏-fountain 喷泉 -fountain and irrigation system喷泉系统-footbridge 人行天桥 -fire truck消防车-furniture家具、设备 -firepot/chafing dish火锅-gutter 明沟 -ditch暗沟-gully峡谷、冲沟-valley 山谷 -garage 车库 -foyer门厅、休息室-hall门厅-lobby 门厅、休息室-industry zone工业区-. island 岛 -inn 小旅馆 -jet喷头-kindergarten 幼儿园 -kiosk小亭子(报刊、小卖部)-lamps and lanterns灯具-lighting furniture照明设置-mezzanine 包厢 -main stadium主体育场-outdoor terrace室外平台-oil painting油画-outdoor steps/exterior steps室外台阶-pillar/pole/column柱、栋梁 -pebble/plinth柱基 -pond/pool池、池塘-pavilion 亭、阁 -pipe/tube 管子 -plumbing 管道 -port港口-pillow 枕头 -pavement 硬地铺装 -path of gravel卵石路-. public plaza公共休闲广场-communal plaza公共广场-pedestrian street步行街-printer 打印机 -resting plaza休闲广场区-rooftop/housetop屋顶 -pile桩-piling 打桩 -pump泵 -ramp 斜坡道、残疾人坡道-riverway 河道 -sunbraking element遮阳构件-sanitation卫生设施 -skylight 天窗 -skyline 地平线 -scanner 扫描仪 -shore 岸、海滨 -sash 窗框 -slab 楼板、地下室顶板-stairhall楼梯厅 -staircase 楼梯间 -secondary structure/minor structure次要结构-. secondary building/accessory building次要建筑-street furniture小品(椅凳标志)-solarium 日光浴室 -terrace 平台 -chip/fragment/sliver/splinter碎片 -safety belt/safety strap/life belt安全带-safety passageway安全通道-shelf/stand架子 -sunshade 天棚 -small mountain stream山塘小溪-subway 地铁 -safety glass安全玻璃-streetscape 街景画 -sinking down plaza下沉广场-sidewalk人行道 -footpath步行道 -设计阶段: -existing condition analysis现状分析 -analyses of existings城市现状分析 -construction site service施工现场服务 -conceptual design概念设计 -circulation analysis交通体系分析 -. construction drawing施工图-complete level完成面标高-details 细部设计、细部大样示意图-diagram 示意图、表 -elevation 上升、高地、海拔、正面图-development design扩初设计-fa?ade/elevation正面、立面-general development analysis城市总体发展分析 -general situation survey概况 -general layout plan/master plan总平面 -general nature environment总体自然分析 -grid and landmark analysis城市网格系统及地标性建筑物分析-general urban and landscape concept总体城市及景观设计概念-general level design总平面竖向设计 -general section总体剖面图 -layout plan布置图 -legend 图例 -lighting plan灯光布置图 -plan drawing平面图 -plot plan基地图 -presentation drawing示意图 -perspective/render效果图 -. pavement plan铺装示意图 -reference pictures/imaged picture参考图片 -reference level参考标高图片 -site overall arrangement场地布局 -space sequence relation空间序列 -specification指定、指明、详细说明书-scheme design方案设计 -sketch手绘草图-sectorization功能分区 -section 剖面 -site planning场地设计 -reference picture of planting植物配置意向图 -reference picture of street furniture街道家具布置意向图 -设计描述: -a thick green area密集绿化 -administration/administrative行政 -administration zone行政区位 -function analysis功能分析 -arc/camber弧形 -askew 歪的、斜的 -aesthetics 美学 -height高度-. abstract art抽象派-artist 艺术家、大师-art nouveau新艺术主义-acre 英亩 -architect建筑师 -be integrated with与结合起来-bisect 切成两份、对开-bend 弯曲 -boundary/border 边界 -operfloor 架空层 -budget 预算 -estimate 评估 -beach 海滩 -building code建筑规范-。

绿色基础设施景观规划Green Infrastructure for Landscape Planning外文原文:Physical infrastructure for promotion of healthParksNaturalistic open space provides the urban dweller with a broad range of services, including scenic, psychological, social, educational and scientific, as well as the opportunity to experience nature. Private development rarely provides public open spaces unless compelled by government. This is because the services listed above are health and quality of life interests that are often beyond the economic calculation of development products and profits. This is to say that developers are not held accountable for the costs of dangerous or unhealthy neighborhoods. Nevertheless, the impacts of these disservices are borne by individuals and the community. Since the free market fails to provide public open space, the public sector acts in the citizens’ interest. When we consider that healthy ecosystems are also in the citizens’ interest, then the preservation of biodiversity, flood protection and other services, such as open space, are justifiable planning and government concerns. Nevertheless, open space generally follows an urban to rural gradient in respect to size and degree of human modification. This reflects land cost and the absence of systematic planning.Although poorly distributed, open space is provided by public agencies including municipalities, counties, park districts and state parks. These agencies maintain over 20 million acres of land in the US. The majority of this is managed as state parks, but over six million acres is provided by municipal agencies. Two million acres of the municipal land is managed as informal open space (51.8 percent), habitat (34.3 percent) or preservation (4.9 percent).It is clear that there is a substantial commitment to both formal recreation space and more naturalistic open space. Of course, the amount of formal parkland should not be reduced, but the acreage and thus the proportion of natural parkland within municipalities will need togrow in the future if urban biodiversity is valued.Although open space is usually unplanned or an opportunistic provision, there are notable examples of deliberate open space systems that contain urban, as well as ecologically valuable, open space. These examples provide us with some of the most important demonstrations of the range and value of ecosystem services provided to urban residents.Open space standardsOften open space in a city accumulates due to unplanned opportunities rather than deliberate physical planning that factors minimum size, location, residential density, connectivity or type of space. More often there is a piecemeal approach with a focus on meeting standards. Although very simple, the disadvantages of this approach are that it doesn’t respond to t he characteristics of the community or the unique qualities of the undeveloped landscape. Standards fail to account for opportunities for place making, multiple use or creating economic and other benefits for citizens. Many of these faults are due to an incremental rather than strategic approach.Open-space standards reflect park acreage compared to city population. This simple formula has evolved to include access or service areas, in addition to acreage. This begins to address the unequal provision of open space by cities. In the UK, the first accessibility standard for open space was introduced in the late 1500s and specified that residents should be within three miles of open space. Several more recent standards have been promoted, including the ANGSt recommendations adopted by English Nature, a UK government agency. English Nature is promoting the adoption of these standards (Table 7.1) by all cities and towns. The standards specify at least five acres (2 ha) of green space within 1,000 feet (300 m) of each residence and a 50-acre (20-ha) space within 1.25 miles.Table 7.1 American and British open space recommendations.National Recreation and Park Association Standards - United StatedPark Type Service Radius(miles) Size(acres)Mini-Park Less than 1/4 0.06-1Neighborhood Park 1/4-1/2 5-10Community Park 1/2-3 30-50Large Urban Park One per city 50 minimum, 75+ acres preferredNature Preserve No recommendation No recommendationSports Complex One per city 25 minimum, 40-80 preferredANGSt Standards- United KingdomPark type Service Radius(miles) Size(acres)Neighborhood 1000 (300 meters) 5(2 ha)Community 5/4miles (2 km) 50 (20 ha)Large Urban Park 3 miles (5 km) 250 (100 ha)Regional 6 miles (10 km) 1236 (500 ha)Nature Preserve 2.5 (1 ha) for each 1000 population increment In the US there are no national government requirements or guidelines for parks, open space, natural areas or trails, but the National Recreation and Park Association published guidelines in the early 1980s that set a standard of 6.25–10.5 acres per 1,000 population for urban areas and 15–20 acres for regional parks. The basis of this recommendation was subjective but widely adopted. These guidelines were revised in 1995 (Table 7.1). They suggest park types, sizes and service radii recommendations that many communities have adopted. The recommendations are clearly urban in orientation and there is no consideration of a networked system of parks. Park trails are classified by the association as single purpose, multipurpose or nature trails, but miles per 1,000 people or network density or other supply recommendations are not provided. Similarly, connector trails that are multipurpose but with a transportation focus are an identified trail type but, again, supply recommendations are not provided. Neither the British nor the American standards recognize the opportunity to structure urban growth or the green infrastructure network potentials.Cities meet the recommended standards to varying degrees. Seattle, for example, provides 4.8 acres per 1,000 population of developed parkland and 5.6 acres of natural parkland per 1,000 residents. Philadelphia provides almost seven acres of parkland per 1,000 people. Often,smaller cities provide more park space per resident than large cities. For example, Boulder, Colorado, with a population of 103,600, provides 19 acres of urban parkland per 1,000 residents and 15 miles of greenway trails. Just beyond the city limit, the city provides 146 miles of trails and owns an additional 45,000 acres of natural open space and habitat.The Trust for Public Lands, a national non-profit organization in the US, developed a method to assess the 40 largest American cities according to the provision of parks. The organization combined several measures, which can serve as a guide for cities and towns that are planning park systems within their jurisdictions. As in the British method, both park acreage and access to it are important considerations. The study measured total acres of parkland within the city, but also determined the acreage as a percentage of the total city area. For the 40 cities, the range was 2.1 percent (Fresno) to 22.8 percent (San Diego) of the city area, with a median of 9.1 percent. The median park size ranged from 0.6 acres to 19.9, with a median size of 4.9 acres. Even the best-performing city achieves less than the 30 percent open-space recommendation of this book for healthy human and ecosystem attainment. None of the largest US cities approach the 40 percent land area dedicated to parks achieved by Stockholm. This data suggest that American cities fail to provide the recommended park acreage and that the percentage of land area dedicated to open space is well below the amount necessary to provide for both recreation and habitat needs.The Trust for Public Land also assessed the subject cities according to the public access to the parklands. They also distributed access according to economic stratification of the population. Access was defined as a ten-minute walk (0.5 miles) from the residence to the park entrance. The route needed to be free of obstacles, such as interstate highways, rivers, etc. The percentage of the urban population with this access ranged from 26 percent (Charlotte) to 98 percent (San Francisco), with a median of 57 percent. This data shows that more that 40 percent of Americans do not have the recommended access to parkland.The last measure considered by the Trust for Public Land is the level of service and investment in parks provided by the cities. The service component used playgrounds as a proxy since they reliably predict the provision of other park facilities. Playgrounds per 10,000residents ranged between 1 and 5, with a median of 1.89. Public investment ranged from $31 (El Paso) to $303 (Washington, DC), with a median of $85 per resident.The cities ranked in the top ten for a combination of acreage, access and service and investment were San Francisco, Sacramento, Boston, New York, Washington, Portland, Virginia Beach, San Diego, Seattle and Philadelphia. Cities with higher population density generally scored better on access but not necessarily on the service and investment issue. Total population was also not a predictor of park score rank. Several cities with low population density provided very l arge total park acreage but didn’t qualify for top ranking due to access, service and investment problems. The top ranked, San Francisco, received an outstanding score for access and scored very high for investment ($291.66 per resident) and well above the median for percentage of land area dedicated to parks (17.9 percent), even though total park acreage isn’t the highest. Unfortunately, the Trust for Public Land doesn’t distinguish undeveloped open space and habitat areas from developed parklands. Therefore, judging biodiversity capacity of the cities isn’t possible. Larger expenditures per resident probably result in parklands that are better maintained and more highly programmed with activities.Programming increases the value of existing park acreage, as demonstrated by the following research results. An analysis of 20 studies investigating the value of open space defined a forested land situation (forest size = 24,500 acres; population density = 87 people per square mile) and found that the open space value was $620 (2003) per acre per year. However, when the forest area increased above 24,500 acres, then the open space value per acre decreased, but total value did not decrease. If recreational opportunities are provided, then the open space value increases by 322 percent. This means that programmed urban parkland has higher open-space value and the municipality is maximizing the benefit of its investment in parkland.Systematic open spaceA reasoned approach to open-space planning balances open-space standards with an assessment of local and regional demand for various outdoor recreation pursuits, the presenceof outstanding visual character and local habitat. Comparison of existing supply with demand and existing service levels in the municipality or county would focus attention on where parks of various types are needed. Park and recreation standards, as suggested in Table 7.1, are a starting point for public participatory planning events to tailor an open-space system to local desires and conditions.Provision of open space at StapletonLarge subdivision projects and planned unit developments in the US are often required to provide a percentage of the site as public open space. The amount is determined through direct negotiation of housing density, commercial space and public amenities. This requirement often arises from a public participatory planning process that is absent from the consideration of small-parcel development. As the result of an extensive public planning process, the developer of Stapleton in Denver was required to dedicate 25 percent of the land area to parks, recreation and habitat restoration.The citizen planning effort at Stapleton established a range of open-space types. The eight types are: (1) formal urban parks (about 175 acres); (2) nature parks (in this case Sandhills Prairie park at about 365 acres and the Sand Bluff Nature Area); (3) community parks (20–40 acres each); (4) neighborhood parks (up to ten acres each); (5) parkways or greenways (planted medians, vegetated street edges or landscape corridors with multiple functions, including stormwater management); (6) sports complexes (107 acres); (7) golf courses; and (8) community vegetable gardens. All of the open space shown in the master plan developed by the citizen planning group comprised about 35 percent (1,680 acres) of the land area, but has been reduced to about 25 percent or 1,200 acres. This reduction had the greatest impact on habitat and biodiversity. However, compared to the 6 percent that is dedicated to parks for Denver as a whole, the case of Stapleton is a great improvement and exceeds the best performance of the 40 largest US cities. Similarly, the provision of a continuous green infrastructure that is multifunctional more efficiently delivers the variety of ecosystem services, including wildlife habitat (Figure 7.9). Residents have great access to spaces ranging from plazas, boulevards, greenways, active recreation and nature areas. Uponcompletion of all development at Stapleton there will be 40 acres of open space for every 1,000 people, exceeding the recommended standards by 400 percent. This also greatly exceeds the acreage provided by Seattle and Philadelphia to their citizens, but is far less than the combined park and habitat area provided by Boulder, Colorado.Density and proximityFigure 7.9 This newly restored stream corridor at Stapleton once flowed through box culverts below airport runways. Today the corridor is valuable habitat connected to a regional preserve and other corridors. Note the new public recreation center building at the upper right. People value public open space more highly as population density increases. When the population density increases by 10 percent, the value of open space increases by 5 percent. Poorly used neighborhood parks (Figure 7.10) are often located in single-family residential areas where ample private open space reduces the demand for public space except for neighborhood celebrations or events. Small urban lots within single family, row house or townhouse neighborhoods are more acceptable to residents if parks are nearby. When planning higher-density neighborhoods where multistory apartment, condominium or mixed-use buildings increase population density to above 20 people per gross acre, adjacent public open space should be prioritized to compensate for the absence of private open space and because these residents are most likely to use the provided amenities.When the open space is close to residences it increases their value. Studies demonstrate that when considering properties an average distance (190 feet) from open space, compared to those 30 feet closer to open space, there is about 0.1 percent increase in price for the closerproperty. The price increase effect grows with each increment closer to the open space.Figure 7.10 This neighborhood park in a single-family residential neighborhood provides lawn, ornamental planting and a shade structure. All of these features are available in most of the private open space, which reduces park use except for neighborhood events. Recreation facilitiesIn the US the National Recreation and Park Association recommends recreation facility standards just as they do for types of park acreage. From the green infrastructure point of view these facilities need to be located where they can be linked to other network resources and the residential and employment centers that might contribute users. Again the proximity of the recreation opportunities will encourage public use.Land-use mix and destinationsGreater use of public open space results when development types are varied. When retail, employment and civic opportunities and residential areas are adjacent to each other and connected by pedestrian-friendly streets, then people are encouraged to walk between use areas (Figure 7.11). Some destinations are anchors within a network of pedestrian and bicycle routes and other uses. Schools, libraries, city administration, shopping districts, civic plazas, waterfronts and many other elements can function as anchors, drawing people along circulation routes. In Figure 7.12 restaurants, shops and offices surround an urban park and plaza. These attract pedestrians from apartments, condominiums, row houses and townhouses,and even regional shopping and auto services that are all visible in this small section of Stapleton. The beautiful promenade shown on the right side of the image and in Figure 7.13 inspire evening strolls and daily commuting on foot. The resulting concentration of people arriving for different purposes encourages other people to come to see the activity (Figure 7.3).Figure 7.11 As residential and employment density increase, so does use of public plazas,promenades and formal parks.Figure 7.12 This image shows the 29th Avenue promenade (right) leading to the Founders Park and urban plaza. The mixed-density neighborhood includes apartments, row houses,townhouses and multistory mixed-use buildings.Figure 7.13 This wide median is a wonderful place to walk and is anchored by a destination –the mixed-use neig hborhood center and plaza on 29th Avenue. It is Stapleton’s version of thepasseggiata.Residential densityLow residential density results in lower pedestrian and bicycle activity and use of public open space. Conversely, as residential density increases, privately owned open space shrinks and the demand for public space and facilities increases. This is also true for the size of the residential living area. In Italy, for example, the evening stroll (passeggiata) is the opportunity to meet with friends, bump into playmates or eat an ice cream or a meal. There is no reason not to window shop, discuss a bit of business or study the latest fashion trends. There is no reason not to relax, get some exercise and enjoy the beauty of the city. This is all possible when the civic realm is nearby and well designed. It is possible even if the home or apartment is too small to accommodate a crowd of friends. Visitors from the US are astounded at the numbers of citizens of all ages who engage in the gregarious passeggiata, even in chilly winter months. It requires more effort, but even in the US we can find inviting urban spaces teeming with our neighbors and visitors (see Figure 7.16). Unfortunately, in the US there arefewer of these settings because the residential density is so low that the walk from the home to the public plaza is too far to become incorporated into our daily lives, unless we drive and park, which are often inconvenient.Neighborhood civility and safetyThere are often neighborhood disincentives for walking, bicycling or making other use of the public landscape. Planning and design can make public places safer, but other efforts must be brought to bear when fear of becoming a victim of crime or prejudice prevents people from using the streets, parks and trails. Tackling the problems of poverty, limited education, racism, gangs or other examples of failing community health is as important as it is difficult. Walkability facilities and street connectivityPeople walk or bicycle when the infrastructure encourages it. There is really a fundamental level of service and a more robust infrastructure that is necessary as the numbers of people walking and bicycling increase. Fundamental planning and design measures include supportive street widths, street patterns and environmental measures to reduce heat, glare and accidents, and to increase access. Streets need to connect to other streets in a legible pattern that allows direct routes to community destinations like civic buildings, open space, employment centers, schools, etc. Dead ends and cul-de-sacs should be limited or have non-vehicular routes through them. The system of roads must incorporate the needs of all users, not only those of vehicle operators. For example, short blocks (200–300 feet) encourage pedestrians, while long ones (600 feet) discourage walking because routes become too indirect. Bicycle paths need a minimum network density to allow reasonable routes through the city. Walking requires smooth surfaces and separation from cars and trucks, as well as ramps for wheelchair users and others.When a fundamental and functional set of routes and surfaces have been provided then planning and design should concentrate on quality improvements, as well as system expansion (Figure 7.14). Walkability is as much about the satisfaction of walking as the engineering aspects of routes and surfaces. What will make walking a satisfying experience? There are facilities and amenities that will better support a journey. Frequent places to stopfor water, shade and seating improve the experience. Separation between motorized vehicles, bicycles and walkers is necessary as the density of each increase. The separation improves the experience and reduces conflicts and accidents. For bicyclists, more frequent facilities to lock and store bicycles, and frequent stations where there is air or supplies for bicycle tire maintenance and repair lead to ever more participation in non-motorized transportation. An expanded range of bicycle rental (Figure 7.15) and bicycle storage options, like covered shelters or lockers, serves an expanded group of users. Public or workplace facilities to shower or change clothes are beneficial.Another group of pedestrian and bicycling amenities are less tangible or functional. Walking and bicycle routes should be choreographed. They are, after all, spatial-temporal environments where the experience can be punctuated, focused and enriched by a variety of design elements. Bringing the concepts of nodes, districts and thresholds to the recreation or transportation experiences of walking and bicycling offer many opportunities for creative design. Changes in color and texture of the paving and the character of the plantings or building types can enliven and structure the experience. Manipulating the character of the enclosing edges and overhead plane also changes the spatial experience and increases the variety and sense of place in sections of the journey.Figure 7.14 Special infrastructure is needed to support high levels of bicycle ridership. Thisapplies to increased pedestrian density as well.Cultural, educational or interpretive signage, sculpture and other site art add meaning and place attachment. These elements distinguish one route, city or region from another and increase the satisfaction of moving through the landscape. Cultural and natural history interpretation can be combined with local building and plant materials to create unique settings.TrafficHigh traffic speed and volume discourage use of urban sidewalks. Reducing these factors within central business districts improves the pedestrian experience and willingness to frequent local businesses. Increasing public transportation ridership and creating disincentives for driving a private vehicle has been successful in many US cities. Portland capped the number of parking lots and spaces within the city center. In fact, since this regulation was enacted the number of parking spaces has steadily declined as parking lots are converted to more profitable commercial or residential uses. This has caused the price of daily parking to increase in private and public lots and structures. Light rail and bus ridership for travel to and from the city has increased steadily. Short-term rental of automobiles within the city is growing rapidly to serve the needs of commuters who have to make short trips within the city during the workday. Rentals of publicly or privately provided bicycles satisfy the same needs.Figure 7.15 As bicycle and pedestrian use increases, cities need to respond with additional support facilities, such as bike storage, signage, rest areas, dedicated routes and bicycle rental programs. Additional facilities foster greater citizen participation.Figure 7.16 An autumn afternoon in Boulder, Colorado. This civic and commercial mall is a closed street refurbished with new paving, seating, play areas, trees and outdoor cafes. Slowing the speed of traffic on streets intended to serve pedestrians can be accomplished by narrowing travel lanes slightly, by providing on-street parallel or angled parking and by including planted medians and parkway tree plantings.Pedestrian and bicycle safety structuresOf course, crosswalks and traffic signals need to be provided wherever pedestrian or bicycle safety is a concern, but as pedestrians and bicyclists become a greater pro portion of the users of urban streets, additional safety measures can be implemented. Mid-block crosswalks are safer crossing locations for pedestrians than busy inter sections, since many accidents involve turning vehicles. When the street is wide, curb extensions and a median reduce the expanse of roadway the pedestrian must cross. The median provides a refuge spot if the pedestrian can’t cross the street in a single traffic cycle.Figure 7.17 Bicycle signaling to reduce conflicts with turning automobiles. Copenhagen and other European cities have implemented traffic signals that allow bicycles to cross intersections before autos begin moving or turning operations (Figure 7.17). This practice and the provision of an extensive network of bicycle lanes and other amenities have dramatically increased commuting by bicycle. In addition to increased safety, bicycle traffic signals increase the speed of travel for cyclists, making them more competitive with private and public transit modes. Incidentally, preferential traffic signals and other rules for public transit also increase ridership by making it more time-competitive with the privateautomobile.Figure 7.18 This comfortable park in Stapleton is the focus of enclosing office and retail buildings. Its appealing vegetation offers many benefits.VegetationVegetation is an open-space element that can have many benefits. Elsewhere street tree amelioration of the urban heat island effect was noted, but street trees, hedges and flowers are part of an enjoyable urban environment that encourages walking and bicycling. The beauty, shade and rain protection all contribute to the pedestrian environment (Figure 7.18), as does the real and suggested protection from nearby motorized vehicles. Capture of particulate air pollution is a more direct health benefit of urban vegetation. The presence of street trees and nearby green spaces has been shown to improve physical activity as discussed in the chapter on human health.译文:绿色基础设施的景观规划基础设施促进身体健康公园自然的开放空间为城市居民提供广泛的服务,包括景区,心理,社会,教育和科学等服务,以及体验大自然的机会。

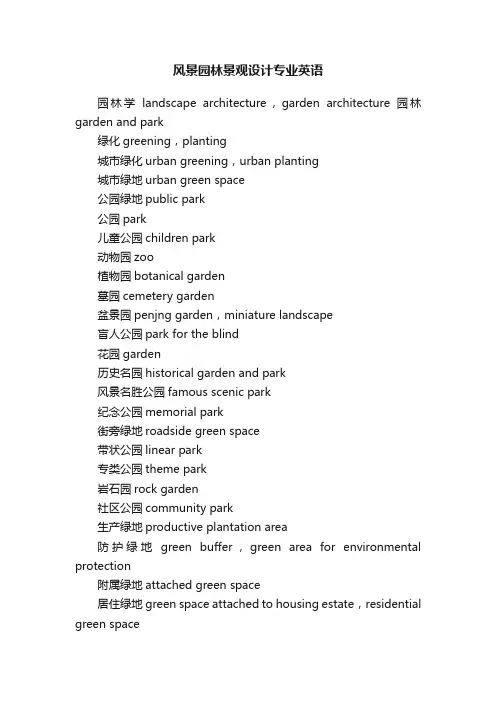

园林学landscape architecture,garden architecture 园林garden and park绿化greening,planting城市绿化urban greening,urban planting城市绿地urban green space公园绿地public park公园park儿童公园children park动物园zoo植物园botanical garden墓园cemetery garden盆景园penjng garden,miniature landscape盲人公园park for the blind花园garden历史名园historical garden and park风景名胜公园famous scenic park纪念公园memorial park街旁绿地roadside green space带状公园linear park专类公园theme park岩石园rock garden社区公园community park生产绿地productive plantation area防护绿地green buffer,green area for environmental protection附属绿地attached green space居住绿地green space attached to housing estate,residential green space道路绿地green space attached to urban road and square屋顶花园roof garden立体绿化vertical planting风景林地scenic forest land城市绿地系统urban green space system城市绿地系统规划urban green space system planning 绿化覆盖面积green coverage绿化覆盖率percentage of greenery coverage绿地率greening rate,ratio of green space绿带green belt楔形绿地green wedge城市绿线boundary line of urban green space园林史landscape history,garden history古典园林classical garden囿hunting park苑imperial park皇家园林royal garden私家园林private garden寺庙园林monastery garden园林艺术garden art相地site investigation造景landscaping借景borrowed scencry,view borrowing园林意境poetic imagcry of garden透景线perspective line盆景miniature landscape,penjing插花flower arrangement季相seasonal appearance of plant园林规划garden planning,landscaping planning 园林布局garden layout园林设计garden design公园最大游人量maximum visitors capacity in park 地形设计topographical design园路设计garden path design种植设计planting design孤植specimen planting,isolated planting对植Opposite planting,coupled planting列植linear planting群植group planting,mass planting园林植物landscape plant观赏植物ornamental plant古树名木historical tree and famous wood species 地被植物ground cover plant攀缘植物climbing plant,climber温室植物greenhouse plant花卉flowering plant行道树avenue tree,street tree草坪lawn绿篱hedge花篱flower hedge花境flower border人工植物群落man-made planting habitat园林建筑garden building园林小品small garden ornaments园廊veranda,gallery,colonnade水榭waterside pavilion舫boat house园亭garden pavilion,pavilion园台platform月洞门moon gate花架pergola,trellis园林楹联couplet written on scroll,couplet on pillar 园林匾额bian'e in garden园林工程garden engineering绿化工程plant engineering大树移植big tree transplanting假植heeling in,temporary planting基础种植foundation planting种植成活率ratio of living tree适地适树planting according to the environment 造型修剪topiary园艺horticulture假山rockwork,artificial hill置石stone arrangement,stone layout掇山piled stone hill,hill making塑山man-made rock work园林理水water system layout in garden驳岸revetment in garden喷泉fountain风景名胜区landscape and famous scenery国家重点风景名胜区national park of China风景名胜区规划landscape and famous scenery planning 风景名胜famous scenery,famous scenic site风景资源scenery resource景物view,feature景点feature spot,view spot景区scenic zone景观landscape,scenery游览线touring route环境容量environmental capacity国家公园national park。

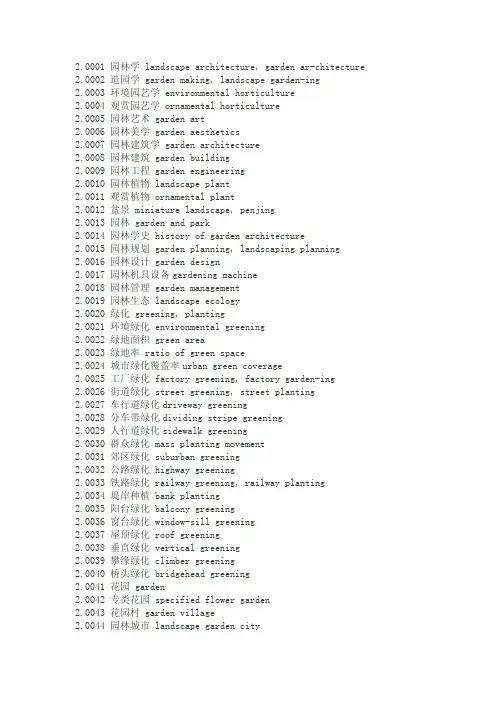

2.0001 园林学 landscape architecture, garden ar-chitecture 2.0002 造园学 garden making, landscape garden-ing2.0003 环境园艺学 environmental horticulture2.0004 观赏园艺学 ornamental horticulture2.0005 园林艺术 garden art2.0006 园林美学 garden aesthetics2.0007 园林建筑学 garden architecture2.0008 园林建筑 garden building2.0009 园林工程 garden engineering2.0010 园林植物 landscape plant2.0011 观赏植物 ornamental plant2.0012 盆景 miniature landscape, penjing2.0013 园林 garden and park2.0014 园林学史 history of garden architecture2.0015 园林规划 garden planning, landscaping planning2.0016 园林设计 garden design2.0017 园林机具设备gardening machine2.0018 园林管理 garden management2.0019 园林生态 landscape ecology2.0020 绿化 greening, planting2.0021 环境绿化 environmental greening2.0022 绿地面积 green area2.0023 绿地率 ratio of green space2.0024 城市绿化覆盖率urban green coverage2.0025 工厂绿化 factory greening, factory garden-ing2.0026 街道绿化 street greening, street planting2.0027 车行道绿化driveway greening2.0028 分车带绿化dividing stripe greening2.0029 人行道绿化sidewalk greening2.0030 群众绿化 mass planting movement2.0031 郊区绿化 suburban greening2.0032 公路绿化 highway greening2.0033 铁路绿化 railway greening, railway planting2.0034 堤岸种植 bank planting2.0035 阳台绿化 balcony greening2.0036 窗台绿化 window-sill greening2.0037 屋顶绿化 roof greening2.0038 垂直绿化 vertical greening2.0039 攀缘绿化 climber greening2.0040 桥头绿化 bridgehead greening2.0041 花园 garden2.0042 专类花园 specified flower garden2.0043 花园村 garden village2.0044 园林城市 landscape garden city2.0045 蔷薇园 rose garden2.0046 松柏园 conifer garden2.0047 球根园 bulb garden2.0048 宿根园 perennial garden2.0049 假山园 rock garden, Chinese rockery2.0050 狩猎场 hunting ground2.0051 街心花园 street crossing center garden2.0052 小游园 petty street garden2.0053 水景园 water garden2.0054 铺地园 paved garden2.0055 野趣园 wild plants botanical garden2.0056 野生植物园wild plants garden2.0057 乡趣园 rustic garden2.0058 盆景园 penjing garden, miniature land-scape 2.0059 动物园 zoo, zoological garden2.0060 墓园 cemetery garden2.0061 沼泽园 bog and marsh garden2.0062 水生植物园aquatic plants garden2.0063 学校园 school garden2.0064 室内花园 indoor garden2.0065 芳香花园 fragrant garden2.0066 盲人花园 garden for the blind2.0067 公园 park, public park2.0068 城市公园 city park, urban park2.0069 区公园 regional park2.0070 儿童公园 children park2.0071 体育公园 sports park2.0072 森林公园 forest park2.0073 纪念公园 memorial park2.0074 烈士纪念公园martyr memorial park2.0075 综合公园 comprehensive park2.0076 文化公园 cultural park2.0077 文化休憩公园cultural and recreation park 2.0078 中央公园 central park2.0079 天然公园 natural park2.0080 海滨公园 seaside park, seabeach park2.0081 古迹公园 historic site park2.0082 河滨公园 riverside park2.0083 湖滨公园 lakeside park2.0084 路边公园 roadside park, street park2.0085 娱乐公园 amusement park2.0086 雕塑公园 sculpture park2.0087 休憩公园 recreation park2.0088 疗养公园 sanatorium park2.0089 国家公园 national park2.0090 邻里公园 neighborhood park2.0091 特种公园 special park2.0092 植物园 botanical garden2.0093 植物公园 abeled plants park2.0094 高山植物园 alpine garden2.0095 热带植物园 tropical plants garden2.0096 药用植物园 medical plants garden, herb garden 2.0097 绿地 green space2.0098 公共绿地 public green space2.0099 单位绿地 unit green area2.0100 城市绿地 urban green space2.0101 街道广场绿地street and square green area2.0102 居住区绿地 residential quarter green area2.0103 防护绿地 green area for environmental protection 2.0104 郊区绿地 suburban green space2.0105 街坊绿地 residential block green belt2.0106 附属绿地 attached green space2.0107 生产绿地 productive plantation area2.0108 苗圃 nursery2.0109 风景 landscape, scenery2.0110 自然景观 natural landscape2.0111 人文景观 human landscape, scenery of humanities 2.0112 草原景观 prairie landscape2.0113 山岳景观 mountain landscape, alpine landscape 2.0114 地理景观 geographical landscape2.0115 湖泊景观 lake view2.0116 郊区景观 suburban landscape2.0117 地质景观 geological landscape2.0118 喀斯特景观 karst landscape2.0119 植物景观 plants landscape, flora landscape02.2 园林史02.2.1 中国园林史2.0120 中国古典园林classical Chinese garden2.0121 中国传统园林traditional Chinese garden2.0122 中国古代园林ancient Chinese garden2.0123 中国山水园 Chinese mountain and water garden2.0124 帝王宫苑 imperial palace garden2.0125 皇家园林 royal garden2.0126 私家园林 private garden2.0127 江南园林 garden on the Yangtze Delta02.2.2 西方园林史2.0128 西方古典园林 western classical garden2.0129 英国式园林 English style garden2.0130 中英混合式园林Anglo-Chinese style garden2.0131 意大利式园林 Italian style garden2.0132 西班牙式园林 Spanish style garden2.0133 法兰西式园林 French style garden2.0134 勒诺特尔式园林Le Notre’s style garden2.0135 文艺复兴庄园 Renaissance style villa2.0136 洛可可式园林 Rococo style garden2.0137 巴洛克式园林 Baroque style garden2.0138 庄园 manor, villa garden2.0139 廊柱园 peristyle garden, patio2.0140 绿廊 xystus2.0141 迷阵 maze, labyrinth02.2.3 典型中西园林2.0142 灵囿 Ling You Hunting Garden2.0143 灵沼 Ling Zhao Water Garden2.0144 灵台 Ling Tai Platform Garden2.0145 阿房宫 E-Pang Palace2.0146 上林苑 Shang-Lin Yuan2.0147 未央宫 Wei-Yang Palace2.0148 洛阳宫 Luoyang Palace2.0149 华清官 Hua-Qing Palace2.0150 艮岳 Gen Yue Imperial Garden2.0151 圆明园 Yuan-Ming Yuan Imperial Garden2.0152 颐和园 Yi-He Yuan Imperial Garden,Summer Palace 2.0153 承德避暑山庄Chengde Imperial Summer Resort2.0154 苏州园林 Suzhou traditional garden2.0155 悬园 Hanging Garden2.0156 英国皇家植物园Royal Botanical Garden, Kew garden 2.0157 凡尔赛宫苑 Versailles Palace Park2.0158 枫丹白露宫园 Fontainebleau Palace Garden02.3 园林艺术2.0159 景 view, scenery, feature2.0160 远景 distant view2.0161 近景 nearby view2.0162 障景 obstructive scenery, blocking view2.0163 借景 borrowed scenery, view borrowing2.0164 对景 opposite scenery, view in opposite place2.0165 缩景 miniature scenery, abbreviated scenery 2.0166 漏景 leaking through scenery2.0167 框景 enframed scenery2.0168 尾景 terminal feature2.0169 主景 main feature2.0170 副景 secondary feature2.0171 配景 objective view2.0172 夹景 vista line, vista2.0173 前景 front view2.0174 背景 background2.0175 景序 order of sceneries2.0176 景点 feature spot, view spot2.0177 仰视景观 upward landscape2.0178 俯视景观 downward landscape2.0179 季相景观 seasonal phenomena2.0180 气象景观 meteorological diversity scenery 2.0181 视野 visual field2.0182 秋色fall color, autumn color2.0183 园林空间 garden space2.0184 开敞空间 wide open space, wide space2.0185 封闭空间 enclosure space2.0186 意境 artistic conception, poetic imagery 2.0187 苍古 antiquity2.0188 空灵 spaciousness, airiness2.0189 动观 in-motion viewing2.0190 静观 in-position viewing2.0191 视错觉 visual illusion2.0192 园林艺术布局artistic layout of garden2.0193 对称平衡 symmetrical balance2.0194 不对称平衡asymmetrical balance2.0195 左右对称 bilateral symmetry2.0196 辐射对称 radial symmetry2.0197 透景线 perspective line2.0198 轴线 axis, axial line2.0199 主轴 main axis2.0200 副轴 auxiliary axis2.0201 暗轴 hidden axis, invisible axis2.0202 树冠线 skyline2.0203 园林色彩艺术 art of garden colors2.0204 单色谐调 monochromatic harmony2.0205 复色谐调 compound chromatic harmony2.0206 对比色突出 contrast colors accent2.0207 近似色谐调 approximate colors harmony2.0208 暖色 warm color2.0209 冷色 cool color2.0210 色感 color sense2.0211 城市绿地系统规划 urban green space system planning2.0212 绿地系统 green space system2.0213 公共绿地定额 public green space quota2.0214 公共绿地指标 public green space norm2.0215 绿地布局 green space layout2.0216 吸引圈 attractive circle2.0217 吸引距离 attractive distance2.0218 有效半径 effective radius2.0219 绿地资源 green space resource2.0220 绿地效果 green space effect2.0221 绿地规划程序 planning procedure of the green space2.0222 空间规划 space planning2.0223 形象规划 image plan2.0224 实施规划 implementary plan2.0225 必要生活空间 necessary living space2.0226 余暇生活空间 leisure time living space2.0227 利用频度 usage frequency2.0228 树种规划 planning of trees and shrubs2.0229 绿地类型 type of green space2.0230 环状绿型 annular green space2.0231 块状绿地 green plot2.0232 点状绿地 green spot2.0233 放射状绿地 radiate green space2.0234 楔状绿地 wedge-shaped green space2.0235 缓冲绿地 buffer green space2.0236 防音绿地 noiseproof green space2.0237 科学景观论 scientific landscape theory2.0238 园林保留地 reserve garden2.0239 公园规划 park planning2.0240 园林总体规划 garden master planning2.0241 总平面规划 site planning2.0242 园林分区 garden zoning2.0243 安静休息区 tranquil rest area2.0244 儿童活动区 children playing space2.0245 儿童游戏场 children playground, playlot2.0246 体育运动区 sports activities area2.0247 野餐区 picnic place2.0248 散步区 pedestrian space2.0249 群众集会区mass meeting square2.0250 观赏植物区ornamental plants area2.0251 观赏温室区display greenhouse area, display conservatory area 2.0252 草坪区 lawn space2.0253 绿荫区 shade tree section2.0254 历史古迹区 historical relics area2.0255 青少年活动区 youngsters activities area 2.0256 诱鸟区 bird sanctuary area2.0257 钓鱼区 fishing center2.0258 野营区 camp site2.0259 游人中心 visitors center2.0260 服务中心 service center2.0261 探险游乐场 adventure ground2.0262 文化活动区 cultural activities area2.0263 道路系统 approach system, road system2.0264 环形道路系统 circular road system2.0265 方格形道路系统 latticed road system2.0266 放射形道路系统 radiate road system2.0267 自然式道路系统 informal road system2.0268 规整式道路系统 formal road system2.0269 混合式道路系统 mixed style road system2.0270 园林规划图 garden planning map2.0271 园林规划说明书 garden planning direction 2.0272 城市公园系统 urban park system2.0273 公园分布 distribution of parks2.0274 公园类型 park type, park category2.0275 公园间距 distance between parks2.0276 公园形式 park styles2.0277 游览区 excursion area, open-to-public area 2.0278 非游览区 no-admittance area2.0279 办公区 administrative area2.0280 服务区 service center2.0281 动休息区 dynamic rest space2.0282 静休息区 static rest space2.0283 娱乐演出区 entertaining performance place 2.0284 主要入口 main entrance2.0285 次要入口 secondary entrance2.0286 人流量 visitors flowrate2.0287 车流量 vehicle flowrate2.0288 公园道路 park road2.0289 公园水陆面积比率land-water ratio2.0290 游人容纳量 visitors capacity2.0291 风景资源调查landscape resource uation2.0292 风景学 scenicology2.0293 风景规划 landscape plan2.0294 风景设计 landscape design2.0295 游览路线 touring route2.0296 旅游资源 tourism resource2.0297 旅游地理 tourism geography2.0298 旅游地质 tourism geology2.0299 历史名城 famous historical city2.0300 文化名城 famous cultural city2.0301 文化遗址 ancient cultural relic2.0302 天然博物馆 natural open museum2.0303 风景地貌 natural geomorphology2.0304 造型地貌 imaginative geomorphologic figuration2.0305 风景区 scenic spot, scenic area2.0306 风景名胜 famous scenery, famous scenic site2.0307 特异景观风景区specific natural scenes area2.0308 民族风俗风景区scenic spot of minority customs2.0309 高山风景区 alpine scenic spot2.0310 海滨风景区 seabeach scenic spot2.0311 森林风景区 forest scenic spot2.0312 高山草甸风景区alpine tundra landscape spot2.0313 峡谷风景区 valley scenic spot2.0314 江河风景区 river landscape district2.0315 湖泊风景区 lake round scenic spot2.0316 温泉风景区 hot spring scenic spot2.0317 瀑布风景区 waterfall scenic spot2.0318 禁伐禁猎区 region forbidden to tree cutting and hunting 2.0319 封山育林区 region closed for afforestation2.0320 天池风景区 crater lake scenic spot2.0321 自然保护区 nature protection area2.0322 科学保护区 protection area for scientific research2.0323 天然纪念物 natural monument2.0324 生物圈保护区 biosphere protection area。