拉斯韦尔《社会传播的结构与功能》

- 格式:doc

- 大小:78.50 KB

- 文档页数:11

传播的基本社会功能传播对人类社会发挥着重要的作用。

1948年,传播学家拉斯韦尔概括了人类传播的三项基本社会功能:1)环境监控功能。

自然和社会环境是在不断变化的,人类必须及时了解和把握环境的变化,以便调节自己的行为来适应这些变化。

传播起着一种“瞭望哨”的作用,帮助人类及时收集和提供关于环境变化的信息。

2)社会协调功能。

社会是一个建立在分工与协作基础上的有机体,只有实现了社会各部分的沟通、协调与统一,才能作为一个整体有效地适应内外环境的变化。

传播是社会的“神经系统”,有了这个系统,社会才能实现正常运转。

3)文化传承功能。

有了高度发达的传播系统,前人的文化遗产、经验、智慧、知识才能被记录、积累、流传下来,后人才能在前人的基础上进一步发展,传播对维持人类社会、国家和民族的存续和发展起着重要作用。

在拉斯韦尔概括的三种功能的基础上,传播学家赖特在1959年又补充了第四项功能,即“提供娱乐”,并称为“传播的四项基本社会功能”。

施拉姆又在此基础上指出了传播的经济功能,指出大众传播能够开创经济行为。

52.语义空间即语言意义的世界,一般来说,信息是意义和符号的统一体,内在的意义只有通过一定的外在形式(动作、表情、文字、音声、图画、影像等符号)才能表达出来。

因此,每一种符号体系在广义上都是传达意义的语言,它们所表达的意义构成了特定的语义空间。

传播既是在社会空间进行的,也是在语义空间中进行的;传播得以实现的一个前提条件就是传受双方必须要有共通的语义空间,即对符号含义的共同理解或拥有共同的文化背景,否则传播过程本身便不能成立,或传而不通,或招来误解。

因此,语义空间也是传播效果研究的一个重要概念。

53.人际影响即群体内个人对个人的影响,拉扎斯菲尔德、卡兹在四、五十年代的研究表明,在人们就公共事务、购物、时尚等领域的具体问题作出自己的选择和决策之际,这些选择和决策与其说是接受了大众传播的影响,倒不如说是在更大程度上接受了群体内其他成员的个人影响。

《社会传播的结构与功能》导读一、拉斯韦尔其人其学作为公认的传播学四大奠基人之一,哈罗德·D·拉斯韦尔(Harold D·Lasswell,1902—1978)出生于美国伊利诺伊州的唐奈森,他的父亲是那里的一个长老会牧师,母亲是中学教师。

父母活跃、对事事充满好奇心的个性完全遗传到了他们的儿子身上,拉斯韦尔属于那种早慧的天才人物。

16岁进入芝加哥大学学习之前,已经受到马克思和弗洛伊德的影响。

1918年进入大学后,“芝加哥学派”领军人物罗伯特·帕克、象征互动论的发明者乔治·赫伯特·米德、实用主义哲学家杜威和制度经济学家索尔斯坦·维布伦等人的思想都深深地吸引了他。

【1】(V)他是美国行为主义政治学的创始人之一,以一个政治学家的声名闻名于西方世界,但他多学科的特性更使他在传播学研究领域收获了巨大的影响和成就。

尽管他不认为自己是一个传播学者,但是“在我们今天可称作传播学观点的东西中,弥漫着拉斯韦尔的许多思想和作品,而不管学术界关注的确切话题是什么。

”(罗杰斯,1986)他的学术兴趣包括宣传研究、舆论信息、政治领袖的作用和大众媒体的内容分析。

【2】(214-215)哈罗德·D·拉斯韦尔生平大事表【2】(214)时间事件1902年2月13日生于美国伊利诺伊州唐奈森1918年16岁进入芝加哥大学,获得一笔奖学金1920年获得哲学学士学位,并继续留在芝加哥大学政治学系攻读博士学位1926年在芝加哥大学获得政治学博士学位。

在此之前,前往瑞士、英国、德国和法国学习和收集资料,并写出其博士论文《世界大战中的宣传技巧》1927年被任命为芝加哥大学政治学助理教授,发表博士论文《世界大战中的宣传技巧》1930年发表《精神病理学与政治学》,标志着将精神分析理论首次主要用于分析政治领袖1936年发表《政治学:谁得到了什么,在什么时候,怎么得到的》,论证政治学的目的是研究权力;被提升为芝加哥大学的终身副教授1938年从芝加哥大学辞职;两辆载有他的全部资料和个人财物的卡车在去纽约的途中翻车和烧毁1939年(与D﹒布卢门泰克合作)发表《世界革命宣传:芝加哥研究》1939—1940年成为洛克菲勒基金会大众传播研讨班的最有影响的成员,在那里他第一次提出传播的“五W”模式1940—1945年担任美国国会图书馆的战时传播研究实验部主任1946年被任命为耶鲁大学法学院教授(以及1952年以后的政治学教授)1948年《社会传播的结构与功能》出版,确定了传播学效果研究的传统1954年受聘任行为科学高级研究中心研究员1955年当选美国政治学会会长1970—1972年担任纽约城市大学杰出教授1972—1976年成为坦普尔大学法学院杰出教授,哥伦比亚大学国际事务的A﹒施韦策教授1976—1978年担任纽约政策学中心的主任1978年12月18日在纽约病故于肺炎,终身未婚拉斯韦尔主要的政治学著作有:《世界政治与个人不安全》(World Politics and PersonalInsecurity,1935)、《政治学:谁得到了什么,在什么时候,怎么得到的》(Politics:Who Gets What,When,How,1936)、《政治面对经济》(Politics Faces Economic,1946)、《权利与人格》(Power and Personality,1948)、《权力与社会:政治研究框架》(Power and Society:A Framework for Political Inquiry,与卡普兰·亚伯拉罕合著,1950)、《政策科学:范围与方法的近期发展》(The Policy Sciences: Recent Developments in Scope and Method,与丹尼尔·勒纳合著,1951)、《政治科学的未来》(The Future of Political Science,1963)等几十部。

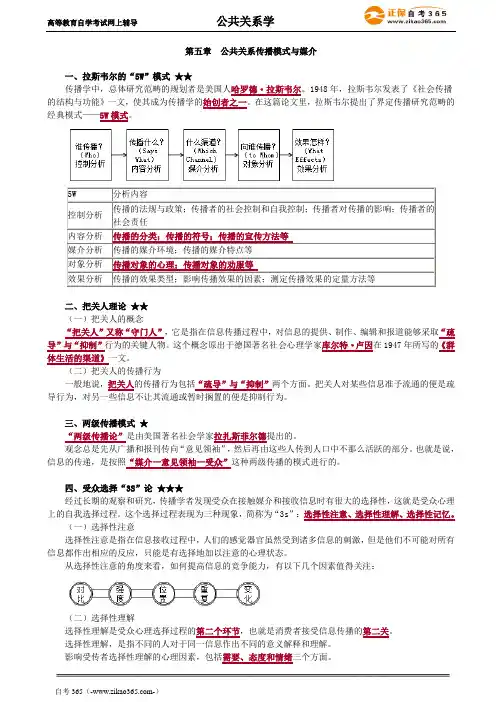

第五章公共关系传播模式与媒介一、拉斯韦尔的“5W”模式★★传播学中,总体研究范畴的规划者是美国人哈罗德·拉斯韦尔。

1948年,拉斯韦尔发表了《社会传播的结构与功能》一文,使其成为传播学的始创者之一。

在这篇论文里,拉斯韦尔提出了界定传播研究范畴的经典模式——5W模式。

5W 分析内容控制分析传播的法规与政策;传播者的社会控制和自我控制;传播者对传播的影响;传播者的社会责任内容分析传播的分类;传播的符号;传播的宣传方法等媒介分析传播的媒介环境;传播的媒介特点等对象分析传播对象的心理;传播对象的劝服等效果分析传播的效果类型;影响传播效果的因素;测定传播效果的定量方法等二、把关人理论★★(一)把关人的概念“把关人”又称“守门人”,它是指在信息传播过程中,对信息的提供、制作、编辑和报道能够采取“疏导”与“抑制”行为的关键人物。

这个概念原出于德国著名社会心理学家库尔特·卢因在1947年所写的《群体生活的渠道》一文。

(二)把关人的传播行为一般地说,把关人的传播行为包括“疏导”与“抑制”两个方面。

把关人对某些信息准予流通的便是疏导行为,对另一些信息不让其流通或暂时搁置的便是抑制行为。

三、两级传播模式★“两级传播论”是由美国著名社会学家拉扎斯菲尔德提出的。

观念总是先从广播和报刊传向“意见领袖”,然后再由这些人传到人口中不那么活跃的部分。

也就是说,信息的传递,是按照“媒介一意见领袖一受众”这种两级传播的模式进行的。

四、受众选择“3S”论★★★经过长期的观察和研究,传播学者发现受众在接触媒介和接收信息时有很大的选择性,这就是受众心理上的自我选择过程。

这个选择过程表现为三种现象,简称为“3s”:选择性注意、选择性理解、选择性记忆。

(一)选择性注意选择性注意是指在信息接收过程中,人们的感觉器官虽然受到诸多信息的刺激,但是他们不可能对所有信息都作出相应的反应,只能是有选择地加以注意的心理状态。

从选择性注意的角度来看,如何提高信息的竞争能力,有以下几个因素值得关注:(二)选择性理解选择性理解是受众心理选择过程的第二个环节,也就是消费者接受信息传播的第二关。

政治传播学引论笔记一、四大先驱1、政治家拉斯韦尔(1)两篇对传播学学科发展献尤为显著地论文——1927年《世界大战的宣传技巧》和传播学开山之作1948《社会传播的结构与功能》(2)5W理论:谁WHO——传播主体;说什么SAYWHAT——传播内容;通过什么渠道INWHICHCHANNEL—传播媒介:对谁说TOWHOM——传播对象;产生什么效果WITHWHATEFFECT——传播效果(3)传播学的五种分析:针对传播主体的控制分析;针对传播内容的内容分析:针对传播媒介的媒介分析;针对传播对象的受众分析;针对传播效果的效果分析。

(4)传播功能的概括:环境监控、社会协调和文化传承,以及社会学家赖特补充的提供族乐。

2、心理学家卢因(1)研究团体生活与动力的团体动力学是卢因对社会心理学的一个贡献。

将其场论应用于社会心理学研究,创立了著名的“群体动力学”,团体动力学研究的是个人在团体中的行为表现:B=(PE)——行为B是由个人P与环境B这两个因素决。

(2)“把关人”理论:传播学的核心概念。

把关是对信息进行筛选和过滤的行为——即传播学所讲的控制。

D·M·怀特开创了传播学的把关研究。

3、社会心理学拉扎斯菲尔德(1)拉扎斯菲尔德吧自然科学的实验方法带进社会学。

(2)两级传播理论;大众传播媒介的信息并不是一步到位地传给受众,这个过程其实分为两步。

第一步是从大众媒介到受众中的一小部分人“意见领袖”,第二步再由这一小部分意见领袖,将媒介的信息扩散到广大的受众那里。

(3)整个社会传播过程中真正发挥作用的还是人际间的影响,即意见领袖对受众的影响远远大于大众媒介的影响。

(4)拉扎斯菲尔德对传播研究方法的贡献:统计调查、抽样分析、数据整理等更具科学性。

但这种科学主义的研究方法只看数据不看其他,拘泥于实证资料,沉泪于统计分析。

4、社会心理学家霍夫兰(1)态度是对某物或某人的一种喜欢与不喜欢的评价性反应,发在人们的信念、悔感、和倾向性行为中表现出来。

传播的功能可以说在我们的生活中,传播现象无处不在处处在。

传播活动对于我们生活产生的影响更是不言而喻。

接触传播学的人都知道,美国政治学家,传播学的奠基人之一拉斯韦尔曾在《社会传播的结构和功能》中对传播的功能做了精辟的分析。

我想我们这些传播学的学子们对传播的功能的了解大概都是从这里开始的吧。

事实上,对于传播的功能从不同的角度分析,我们可以得出不同的答案。

而现在人们对传播功能的分析主要从以下几个方面展开:1、从传播功能的呈现方式上分为:显性功能和隐性功能;2、从传播的释放效应上分为:正功能和负功能;3、从传播的应用的区位分为:思想功能和交际功能;4、从产生的渠道分为:个人的功能、组织的功能和社会的功能。

我个人认为,对于传播研究来讲,这些分类为进一步深入研究大有益处。

但是,过于分散就会导致对传播的研究失去真正的应用意义。

我们从不同的角度去理解传播并没有错误,而问题的关键在于这些研究,这些认识要能够反过来真正发挥它的“服务”功能。

切不能让我们的理论越讲越多而对于如何解决理论中所阐释的问题却丝毫不知。

鉴于此,我更倾向于从传播的释放效应方面来研究传播的功能。

对于传播来讲,我们最终所关注的是它的结果,也就是所谓的效果。

过程虽然很重要,那是我们在研究传播时所不可不关注的,而这些研究最终要为效果来服务。

我们研究的最终归宿应该是如何“疏通”过程,以期达到理想的“结果”。

正如郭庆光在《传播学教程》中所讲:“传播学研究的任务,正在于找到正确发挥大众传播积极功能的机制和规律,而最大限度的防止其消极功能可能对社会造成的危害。

”(116)基于这种认识,我个人比较赞同《军事传播学导论》中对大众传播的正负功能的划分。

不过,在具体的论述上我不敢苟同。

下面我简单整理分析一下有关传播学者对传播功能的论述并提出我的看法。

一、传播功能的代表性论述及个人解析:(一)拉斯韦尔“三功能说”:1、美国政治学家拉斯韦尔在《社会传播的结构和功能》(1948年)一文中,将传播的基本功能概括为:环境监测功能、社会协调功能、社会遗产传承功能。

1.传播学之父是〔A〕1、传播的信息交流过程是〔A〕A、互动的B、主动的C、被动的D、能动的2、在传播学研究中,正式调查所采用的抽样形式一般都是〔B〕A、非随机抽样B、随机抽样C、分层抽样D、雪球抽样3、中央电视台《焦点访谈》节目属于〔B〕A、群体传播B、大众传播C、组织传播D、人际传播4.1948年,拉斯韦尔在《传播在社会中的结构和功能》一文中首次提出了〔B〕A.大众传播学的概念B.传播的5W模式C.政治传播的概念D.内容分析法5.从参与者的角色来说,网络传播不同于大众传播的是〔B〕A.参与者即传播者B.信息传播者和信息接受者的角色可不断进行互换C.网络用户都以充当信息传播者为目标D.网络用户都是信息观察者6.我们把传播过程中产生信息的过程和行为称为〔A〕A制码B编码C译码D释码7.(B)的主要方式是对外出版、对外广播、对外电视传播、信息高速公路A大众传播B国际传播C全球传播D网络传播8.信息表现形式有语言、符号、〔B〕A文字B图像C声音D雕塑9、符号最基本的特点在于它的〔B〕10、直接导致“魔弹”被否认的理论是〔A〕1. 以下哪一种不属于传播者与受众的关系〔D〕?2. 以下哪一种不是我们必须遵循的传播原则〔B〕?3. 以下哪一种不属于传播者的特点〔D〕?4. 以下哪一种不属于传播者的责任〔B〕?5. 当今世界,信息侵略—〔B〕—。

6. 语言是社会约定俗成的并且是比较高级和复杂的〔C〕。

7. 让受众透过媒介经常看到你,可以增强〔A〕。

8. —〔A〕—是指记者可以通过一切正当的手段自由采访新闻的权力。

A. 采访权B. 报道权C. 批评权D. 安全保护权9. 最重要的守门行为出现在媒介组织内部,守门的过程应该分为新闻采集和—〔C〕—两个阶段。

A. 新闻剪辑B. 新闻美化C. 新闻加工D. 新闻删选10. 如果在传播学的研究中,对于个人特点过分强调或是对于传播模式无原则无休止争论的话,真正受到伤害的将是—〔A〕—。

公共关系学-公共关系传播模式与媒介(总分100, 做题时间90分钟)一、单项选择题1.传播学中,总体研究范畴的规划者是美国人______• A.卢因• B.哈罗德·拉斯韦尔• C.拉扎斯菲尔德• D.麦库姆斯SSS_SIMPLE_SINA B C D分值: 1答案:B[解析] 本题考查考生对学科发展史的了解。

传播学中,美国人哈罗德·拉斯韦尔是总体研究范畴的规划者。

2.发表了《社会传播的结构与功能》一文,成为传播学的创始人之一的是______ • A.拉斯韦尔• B.卢因• C.拉扎斯菲尔德• D.麦库姆斯SSS_SIMPLE_SINA B C D分值: 1答案:A[解析] 传播学中,拉斯韦尔是总体研究范畴的规划者,他在1948年发表的《社会传播的结构与功能》一文,使其成为传播学的创始人之一。

3.拉斯韦尔提出的界定传播研究范畴的经典模式是______• A.香农模式•**模式C.两级传播模式• D.议题设置论SSS_SIMPLE_SINA B C D答案:B[解析] 本题属于识记内容,考生需认真掌握。

5W模式是拉斯韦尔在《社会传播的结构与功能》一文中提出的界定传播研究范畴的经典模式。

4.“把关人”这一概念出自______• A.《原则宣言》• B.《修辞学》• C.《社会传播的结构与功能》• D.《群体生活的渠道》SSS_SIMPLE_SINA B C D分值: 1答案:D[解析] 本题属于识记内容,考生需牢记。

1947年,德国著名社会心理学家卢因在《群体生活的渠道》一文中最早提出了“把关人”这一概念。

5.传播学学者十分重视把关人的作用,并认为这是一种信息传播的______• A.特殊现象• B.简单现象• C.普遍现象• D.复杂现象SSS_SIMPLE_SINA B C D分值: 1答案:C[解析] 本题考查考生对“把关人”这一知识点掌握的熟练程度,属于识记内容。

传播学学者十分重视把关人在信息传播过程中的枢纽作用,认为把关人是一种信息传播的普遍现象。

The structure and function of communication in societyHaroldThe act of communicationConvenient way to describe an act of communication is to answer the following questions:WhoSays WhatIn Which ChannelTo WhomWith What EffectThe scientific study of the process of communication tends to concentrate upon one or another of these questions. Scholars who study the "who," the communicator, look into the factors that initiate and guide the act of communication . We call this subdivision of the field of research control analysis. Specialists who focus upon the "says what" engage in content analysis. Those who look primarily at the radio, press, film, and other channels of communication are doing media analysis (p. 84). When the principal concern is with the persons reached by the media, we speak of audience analysis. If the question is the impact upon audiences, the problem is effect analysis.Whether such distinctions are useful depends entirely upon the degree of refinement which is regarded as appropriate to a given scientific and managerial objective. Often it is simpler to combine audience and effect analysis, for instance, than to keep them apart. On the other hand, we may want to concentrate on the analysis of content, and for this purpose subdivide the field into the study of purport and style, the first referring to the message, and the second to the arrangement of the elements of which the message iscomposed.Structure and functionEnticing as it is to work out these categories in more detail, the present discussion has a different scope. We are less interested in dividing up the act of communication than in viewing the act as a whole in relation to the entire social process. Any process can be examined in two frames of reference, namely, structure and function; and our analysis of communication will deal with the specializations that carry on certain functions, of which the following may be clearly distinguished: (i) the surveillance of the environment; (2) the correlation of the parts of society in responding to the environment; (3) the transmission of the social heritage from one generation to the next.Biological equivalencesAt the risk of calling up false analogies, we can gain perspective on human societies when we note the degree to which communication is a feature of life at every level. A vital entity, whether relatively isolated or in association, has specialized ways of receiving stimuli from the environment. The single-celled organism or the many-membered group tends to maintain an internal equilibrium and to respond to changes in the environment in a way that maintains this equilibrium. The responding process calls for specialized ways of bringing the parts of the whole into harmonious action (p. 85). Multi-celled animals specialize cells to the function of external contact and internal correlation. Thus, among the primates, specialization is exemplified by organs such as the ear and eye, and the nervous system itself. When the stimuli receiving and disseminating patterns operate smoothly, the several parts of the animal act in concert in reference to the environment ("feeding," "fleeing," "attacking").In some animal societies certain members perform specialized roles, and survey the environment. Individuals act as "sentinels," standing apart from the herd or flock and creating a disturbance whenever an alarming change occurs in the surroundings. The trumpeting, cackling, or shrilling of the sentinel is enough to set the herd in motion. Among the activities engaged in by specialized "leaders" is the internal stimulation of"followers" to adapt in an orderly manner to the circumstances heralded by the sentinels.Within a single, highly differentiated organism, incoming nervous impulses and outgoing impulses are transmitted along fibers that make synaptic junction with other fibers. The critical points in the process occur at the relay stations, where the arriving impulse may be too weak to reach the threshold which stirs the next link into action. At the higher centers, separate currents modify one another, producing results that differ in many ways from the outcome when each is allowed to continue a separate path. At any relay station there is no conductance, total conductance, or intermediate conductance. The same categories apply to what goes on among members of an animal society. The sly fox may approach the barnyard in a way that supplies too meager stimuli for the sentinel to sound the alarm. Or the attacking animal may eliminate the sentinel before he makes more than a feeble outcry. Obviously there is every gradation possible between total conductance and no conductance (p. 86).Attention in World SocietyWhen we examine the process of communication of any state in the world community, we note three categories of specialists. One group surveys the political environment of the state as a whole, another correlates the response of the whole state to the environment, and thethird transmits certain patterns of response from the old to the young. Diplomats, attaches, and foreign correspondents are representative of those who specialize on the environment. Editors, journalists, and speakers are correlators of the internal response. Educators in family and school transmit the social inheritance.Communications which originate abroad pass through sequences in which various senders and receivers are linked with one another. Subject to modification at each relay point in the chain, messages originating with a diplomat or foreign correspondent may pass through editorial desks and eventually reach large audiences.If we think of the world attention process as a series of attention frames, it is possible to describe the rate at which comparable content is brought to the notice of individuals and groups. We can inquire into the point at which "conductance" no longer occurs; and we can look into the range between "total conductance" and "minimum conductance." The metropolitan and political centers of the world have much in common with the interdependence, differentiation, and activity of the cortical or subcortical centers of an individual organism. Hence the attention frames found in these spots are the most variable, refined, and interactive of all frames in the world community.At the other extreme are the attention frames of primitive inhabitants of isolated areas. Not that folk cultures are wholly untouched by industrialcivilization. Whether we parachute into the interior of New Guinea, or land on the slopes of the Himalayas, we find no tribe wholly out of contact with the world. The long threads of trade, of missionary zeal, of adventurous exploration and scientific field study, and of global war reach far distant places. No one is entirely out of this world (p. 87).Among primitives the final shape taken by communication is the ballad or tale. Remote happenings in the great world of affairs, happenings that come to the notice of metropolitan audiences, are reflected, however dimly, in the thematic material of ballad singers and reciters. In these creations faraway political leaders may be shown supplying land to the peasants or restoring an abundance of game to the hills.When we push upstream of the flow of communication, we note that the immediate relay function for nomadic and remote tribesmen is sometimes performed by the inhabitants of settled villages with whom they come in occasional contact. The re-layer can be the school teacher, doctor, judge, tax collector, policeman, soldier, peddler, salesman, missionary, student; in any case he is an assembly point of news and comment.More detailed equivalencesThe communication processes of human society, when examined in detail, reveal many equivalences to the specializations found in the physicalorganism and in the lower animal societies. The diplomats, for instance, of a single state are stationed all over the world and send messages to a few focal points. Obviously, these incoming reports move from the many to the few, where they interact upon one another. Later on, the sequence spreads fanwise according to a few-to-many pattern, as when a foreign secretary gives a speech in public, an article is put out in the press, or a news film is distributed to the theaters. The lines leading from the outer environment of the state are functionally equivalent to the afferent channels that convey incoming nervous impulses to the central nervous system of a single animal, and to the means by which alarm is spread among a flock. Outgoing, or efferent, impulses display corresponding parallels.The central nervous system of the body is only partly involved in the entire flow of afferent-efferent impulses. There are automatic systems that can act on one another without involving the "higher" centers at all (p. 88). The stability of the internal environment is maintained principally through the mediation of the vegetive or autonomic specializations of the nervous system. Similarly, most of the messages within any state do not involve the central channels of communication. They take place within families, neighborhoods, shops, field gangs, and other local contexts. Most of the educational process is carried on the same way.A further set of significant equivalences is related to the circuits of communication , which are predominantly one-way or two-way, dependingupon the degree of reciprocity between communicators and audience. Or, to express it differently, two-way communication occurs when the sending and receiving functions are performed with equal frequency by two or more persons. A conversation is usually assumed to be a pattern oftwo-way communication (although monologues are hardly unknown). The modern instruments of mass communication give an enormous advantage to the controllers of printing plants, broadcasting equipment, and other forms of fixed and specialized capital. But it should be noted that audiences do "talk back," after some delay; and many controllers of mass media use scientific methods of sampling in order to expedite this closing of the circuit.Circuits of two-way contact are particularly in evidence among the great metropolitan, political, and cultural centers of the world. New York, Moscow, London, and Paris, for example, are in intense two-way contact, even when the flow is severely curtailed in volume (as between Moscow and New York). Even insignificant sites become world centers when they are transformed into capital cities (Canberra, Australia; Ankara, Turkey; the District of Columbia, A cultural center like Vatican City is in intensetwo-way relationship with the dominant centers throughout the world. Even specialized production centers like Hollywood, despite their preponderance of outgoing material, receive an enormous volume of messages.A further distinction can be made between message controlling and message handling centers and social formations. The (p. 89) message center in the vast Pentagon Building of the War Department in Washington transmits with no more than accidental change incoming messages to addressees. This is the role of the printers and distributors of books; of dispatchers, linemen, and messengers connected with telegraphic communication ; of radio engineers and other technicians associated with broadcasting. Such message handlers may be contrasted with those who affect the content of what is said, which is the communication of editors, censors, and propagandists. Speaking of the symbol specialists as a whole, therefore, we separate them into the manipulators (controllers) and the handlers; the first group typically modifies content, while the second does not.Needs and valuesThough we have noted a number of functional and structural equivalences between communication in human societies and other living entities, it is not implied that we can most fruitfully investigate the process of communication in America or the world by the methods most appropriate to research on the lower animals or on single physical organisms. In comparative psychology when we describe some part of the surroundings of a rat, cat, or monkey as a stimulus (that is, as part of theenvironment reaching the attention of the animal), we cannot ask the rat; we use other means of inferring perception. When human beings are our objects of investigation, we can interview the great "talking animal." (This is not that we take everything at face value. Sometimes we forecast the opposite of what the person says he intends to do. In this case, we depend on other indications, both verbal and nonverbal.)In the study of living forms, it is rewarding, as we have said, to look at them as modifiers of the environment in the process of gratifying needs, and hence of maintaining a steady state of internal equilibrium. Food, sex, and other activities which involve the environment can be examined on a comparative basis. Since human beings exhibit speech reactions, we can investigate many more relationships than in the nonhuman species (p. 90). Allowing for the data furnished by speech (and other communicative acts), we can investigate human society in terms of values; that is, in reference to categories of relationships that are recognized objects of gratification. In America, for example, it requires no elaborate technique of study to discern that power and respect are values. We can demonstrate this by listening to testimony, and by watching what is done when opportunity is afforded.It is possible to establish a list of values current in any group chosen for investigation. Further than this, we can discover the rank order in which these values are sought. We can rank the members of the group accordingto their positions in relation to the values. So far as industrial civilization is concerned, we have no hesitation in saying that power, wealth, respect, wellbeing, and enlightenment are among the values. If we stop with this list, which is not exhaustive, we can describe on the basis of available knowledge (fragmentary though it may often be) the social structure of most of the world. Since values are not equally distributed, the social structure reveals more or less concentration of relatively abundant shares of power, wealth, and other values in a few hands. In some places this concentration is passed on from generation to generation, forming castes rather than a mobile society.In every society the values are shaped and distributed according to more or less distinctive patterns (institutions). The institutions include communications which are invoked in support of the network as a whole. Such communications are the ideology; and in relation to power we can differentiate the political doctrine, the political formula, and the miranda. These are illustrated in the United States by the doctrine of individualism, the paragraphs of the Constitution, which are the formula, and the ceremonies and legends of public life, which comprise the Miranda (p. 91). The ideology is communicated to the rising generation through such specialized agencies as the home and school.Ideology is only part of the myths of any given society. There may be counterideologies directed against the dominant doctrine, formula, andmiranda. Today the power structure of world politics is deeply affected by ideological conflict, and by the role of two giant powers, the United States and Russia. The ruling elites view one another as potential enemies, not only in the sense that interstate differences may be settled by war, but in the more urgent sense that the ideology of the other may appeal to disaffected elements at home and weaken the internal power position of each ruling class.Social conflict and communicationUnder the circumstances, one ruling element is especially alert to the other, and relies upon communication as a means of preserving power. One function of communication, therefore, is to provide intelligence about what the other elite is doing, and about its strength. Fearful that intelligence channels will be controlled by the other, in order to withhold and distort, there is a tendency to resort to secret surveillance. Hence international espionage is intensified above its usual level in peacetime. Moreover, efforts are made to "black out" the self in order to counteract the scrutiny of the potential enemy.In addition, communication is employed affirmatively for the purpose of establishing contact with audiences within the frontiers of the other power. These varied activities are manifested in the use of open and secret agents to scrutinize the other, in counterintelligence work, in censorshipand travel restriction, in broadcasting and other informational activities across frontiers.Ruling elites are also sensitized to potential threats in the internal environment. Besides using open sources of information, secret measures are also adopted. Precautions are taken to impose "security" upon as many policy matters as possible. At the same time, the ideology of the elite is reaffirmed, and counter-ideologies are suppressed (p. 92).The processes here sketched run parallel to phenomena to be observed throughout the animal kingdom. Specialized agencies are used to keep aware of threats and opportunities in the external environment. The parallels include the surveillance exercised over the internal environment, since among the lower animals some herd leaders sometimes give evidence of fearing attack on two fronts, internal and external; they keep an uneasy eye on both environments. As a means of preventing surveillance by an enemy, wellknown devices are at the disposal of certain species, ., the squid's use of a liquid fog screen, the protective coloration of the chameleon. However, there appears to be no correlate of the distinction between the "secret" and "open" channels of human society.Inside a physical organism the closest parallel to social revolution would be the growth of new nervous connections with parts of the body that rival, and can take the place of, the existing structures of central integration. Can this be said to occur as the embryo develops in themother's body Or, if we take a destructive, as distinct from a reconstructive, process, can we properly say that internal surveillance occurs in regard to cancer, since cancers compete for the food supplies of the body Efficient communicationThe analysis up to the present implies certain criteria of efficiency or inefficiency in communication. In human societies the process is efficient to the degree that rational judgments are facilitated. A rational judgment implements value goals. In animal societies communication is efficient when it aids survival, or some other specified need of the aggregate. The same criteria can be applied to the single organism.One task of a rationally organized society is to discover and control any factors that interfere with efficient communication. Some limiting factors are psychotechnical. Destructive radiation, for instance, may be present in the environment, yet remain undetected owing to the limited range of the unaided organism (p. 93).But even technical insufficiencies can be overcome by knowledge. In recent years shortwave broadcasting has been interfered with by disturbances which will either be surmounted, or will eventually lead to the abandonment of this mode of broadcasting. During the past few years advances have been made toward providing satisfactory substitutes for defective hearing and seeing. A less dramatic, though no less important,development has been the discovery of how inadequate reading habits can be corrected.There are, of course, deliberate obstacles put in the way of communication, like censorship and drastic curtailment of travel. To some extent obstacles can be surmounted by skillful evasion, but in the long run it will doubtless be more efficient to get rid of them by consent or coercion.Sheer ignorance is a pervasive factor whose consequences have never been adequately assessed. Ignorance here means the absence, at a given point in the process of, communication of knowledge which is available elsewhere in society. Lacking proper training, the personnel engaged in gathering and disseminating intelligence is continually misconstruing or overlooking the facts, if we define the facts as what the objective, trained observer could find.In accounting for inefficiency we must not overlook the low evaluations put upon skill in relevant communication. Too often irrelevant, or positively distorting, performances command prestige. In the interest of a "scoop," the reporter gives a sensational twist to a mild international conference, and contributes to the popular image of international politics as chronic, intense conflict, and little else. Specialists in communication often fail to keep up with the expansion of knowledge about the process; note the reluctance with which many visual devices have been adopted. And despite research on vocabulary, many mass communicators selectwords that fail. This happens, for instance, when a foreign correspondent allows himself to become absorbed in the foreign scene and forgets that his home audience has no direct equivalents in experience for "left," "center," and other factional terms (p. 94).Besides skill factors, the level of efficiency is sometimes adversely influenced by personality structure. An optimistic, outgoing person may hunt "birds of a feather" and gain an un-corrected and hence exaggeratedly optimistic view of events. On the contrary, when pessimistic, brooding personalities mix, they choose quite different birds, who confirm their gloom. There are also important differences among people which spring from contrasts in intelligence and energy.Some of the most serious threats to efficient communication for the community as a whole relate to the values of power, wealth, and respect. Perhaps the most striking examples of power distortion occur when the content of communication is deliberately adjusted to fit an ideology or counterideology. Distortions related to wealth not only arise from attempts to influence the market, for instance, but from rigid conceptions of economic interest. A typical instance of inefficiencies connected with respect (social class) occurs when an upper-class person mixes only with persons of his own stratum and forgets to correct his perspective by being exposed to members of other classes.Research in communicationThe foregoing reminders of some factors that interfere with efficient communication point to the kinds of research, which can usefully be conducted on representative links in the chain of communication. Each agent is a vortex of interacting environmental and predispositional factors. Whoever performs a relay function can be examined in relation to input and output. What statements are brought to the attention of the relay link What does he pass on verbatim What does he drop out What does he rework What does he add How do differences in input and output correlate with culture and personality By answering such questions it is possible to weigh the various factors in conductance, no conductance, and modified conductance (p. 95). Besides the relay link, we must consider the primary link in a communication sequence. In studying the focus of attention of the primary observer, we emphasize two sets of influences: statements to which he is exposed; other features of his environment. An attache or foreign correspondent exposes himself to mass media and private talk; also, he can count soldiers, measure gun emplacements, note hours of work in a factory, see butter and fat on the table.Actually it is useful to consider the attention frame of the relay as well as the primary link in terms of media and nonmedia exposures. The role of nonmedia factors is very slight in the case of many relay operators, while it is certain to be significant in accounting for the primary observer.Attention Aggregates and PublicsIt should be pointed out that everyone is not a member of the world public, even though he belongs to some extent to the world attention aggregate. To belong to an attention aggregate it is only necessary to have common symbols of reference. Everyone who has a symbol of reference for New York, North America, the western hemisphere, or the globe is a member respectively of the attention aggregate of New York, North America, the western hemisphere, the globe. To be a member of the New York public, however, it is essential to make demands for public action in New York, or expressly affecting New York.The public of the United States, for instance, is not confined to residents or citizens, since noncitizens who live beyond the frontier may try to influence American politics. Conversely, everyone who lives in the United States is not a member of the American public, since something more than passive attention is necessary. An individual passes from an attention aggregate to the public when he begins to expect that what he wants can affect public policy.Sentiment Groups and PublicsA further limitation must be taken into account before we can correctly classify a specific person or group as part of a public (p. 96). The demands made regarding public policy must be debatable. The worldpublic is relatively weak and undeveloped, partly because it is typically kept subordinate to sentiment areas in which no debate is permitted on policy matters. During a war or war crisis, for instance, the inhabitants of a region are overwhelmingly committed to impose certain policies on others. Since the outcome of the conflict depends on violence, and not debate, there is no public under such conditions. There is a network of sentiment groups that act as crowds, hence tolerate no dissent.From the foregoing analysis it is clear that there are attention, public, and sentiment areas of many degrees of inclusive-ness in world politics. These areas are interrelated with the structural and functional features of world society, and especially of world power. It is evident, for instance, that the strongest powers tend to be included in the same attention area, since their ruling elites focus on one another as the source of great potential threat. The strongest powers usually pay proportionately less attention to the weaker powers than the weaker powers pay to them, since stronger powers are typically more important sources of threat, or of protection, for weaker powers than the weaker powers are for the stronger.The attention structure within a state is a valuable index of the degree of state integration. When the ruling classes fear the masses, the rulers do not share their picture of reality with the rank and file. When the reality picture of kings, presidents, and cabinets is not permitted to circulatethrough the state as a whole, the degree of discrepancy shows the extent to which the ruling groups assume that their power depends on distortion.Or, to express the matter another way, if the "truth" is not shared, the ruling elements expect internal conflict, rather than harmonious adjustment to the external environment of the state (p. 97). Hence the channels of communication are controlled in the hope of organizing the attention of the community at large in such a way that only responses will be forthcoming which are deemed favorable to the power position of the ruling classes.The Principle of Equivalent EnlightenmentIt is often said in democratic theory that rational public opinion depends upon enlightenment. There is, however, much ambiguity about the nature of enlightenment, and the term is often made equivalent to perfect knowledge. A more modest and immediate conception is not perfect but equivalent enlightenment. The attention structure of thefull-time specialist on a given policy will be more elaborate and refined than that of the layman. That this difference will always exist, we must take for granted. Nevertheless, it is quite possible for the specialist and the layman to agree on the broad outlines of reality. A workable goal of democratic society is equivalent enlightenment as between expert, leader, and layman.。

传播学十大必读经典著作沃尔特•李普曼的《公众舆论》李普曼是传播学史上具有重要影响的学者之一,在宣传分析和舆论研究方面享有很高的声誉。

这位世界上最有名的政治专栏作家在其1922年的著作《公众舆论》中,开创了今天被称为议程设置的早期思想。

此书被公认为是传播学领域的奠基之作。

作为一部传播学经典著作,该书第一次对公众舆论做了全景式的描述,让读者能细细地体会到舆论现象的种种内在与外在联系。

此书自1922年问世以来,在几十年中已经被翻译成几十种文字,至今仍然保持着这个领域中的权威地位。

李普曼的《公众舆论》影响力经久不衰的奥秘在于,该书对舆论研究中一系列难以回避的问题做了卓有成效的梳理,如舆论从哪里来和怎么样形成的?它能造成什么样的结果?谁是公众,什么样的公众?公众舆论是什么意思?它是仅仅在公众中传播还是由公众自己形成的?它是不是或者什么时候才能成为独立的力量?在近代以来的社会中,公众舆论主要作为一种政治现象,可以说只出现过两个源头,即开放的舆论生成与流通系统和封闭的舆论制造与灌输系统,尽管它们都会产生一个复杂程度不相上下的舆论过程,但是结果却不大一样。

李普曼的《公众舆论》对成见、兴趣、公意的形成和民主形象等问题做了精辟而深刻的探讨,完成了新闻史上对舆论传播现象的第一次全面的梳理,为后人的研究奠定了基础。

李普曼很早就注意到了大众传播对社会的巨大影响,因此,在《公众舆论》和《自由与新闻》等著作中,它不仅对新闻的性质及其选择过程进行了深刻的分析,而且提出了两个重要的概念,一个是“拟态环境”(pseudoenvironment);另一个就是“刻板成见”(stereotype)。

李普曼认为,现代社会越来越巨大化和复杂化,人们由于实际活动的范围、精力和注意力有限,不可能对与他们有关的整个外部环境和众多的事情都保持经验性接触,对超出自己亲身感知以外的事物,人们只能通过各种“新闻供给机构”去了解认知。

这样,人的行为已经不再是对客观环境及其变化的反应,而成了对新闻机构提示的某种“拟态环境”的反应。

一、填空题1.拉斯韦尔和贝雷尔森提出的内容分析法,成为传播学的主要研究方法之一。

2.拉斯韦尔在1948年发表的《传播在社会中的结构与功能》一文中最早总结了传播的基本过程,提出了“五W”的传播模式,这个模式明确勾勒出了传播学研究的五个主要领域,并论述了传播的社会功能。

3.拉扎斯菲尔德对研究方法作出了重要贡献,最早运用实地调查法从事广播的研究,被称为传播学研究的“工具制作者”。

4.拉扎斯菲尔德对研究方法作出了重要贡献,他通过不断改进抽样调查技术和量化分析方法,为传播学赢得了来自其他科学的尊重。

5.勒温曾设计了关于群体传播的经典实验,并提出了著名的“把关人”概念。

6.霍夫兰对传播与说服、说服能力与说服方法的研究,对传播学最突出的贡献有二:一是将心理实验方法引入传播学研究,二是通过研究揭示了传播效果形成的条件性和复杂性,否定了早期的“子弹论”效果观。

7.李普曼、拉斯韦尔、勒温、拉扎斯菲尔德以及霍夫兰的研究工作为传播学的创立奠定了基础,可以被称为奠基者。

8.信息论是贝尔实验室的电气工程师香农提出的。

9.在信息论中,香农提出了“熵”的概念以解决信息的量度问题,为传播学的定量研究提供了新的方法。

10.控制论关注的是系统内秩序维持的一般法则,它是由数学天才维纳提出的。

11.美国社会学家库利根据群体在个人社会化过程中所起作用的直接和间接程度,将群体分为初级群体和次级群体。

12.群体意识的核心内容是群体规范。

13.群体暗示是指通过间接的示意而非直接的说服来使人接受某种观点或从事某种行为的说服技巧。

14.群体感染是指某种观点、情绪或行为在群体暗示机制的作用下在群体中迅速蔓延开来的过程。

15.美国社会学家布鲁默认为集合行为的信息运动方式是“循环反应”,一方的刺激成为另一方的反应,而另一方的反应则又反过来成为这一方的刺激的循环往复过程。

16.美国社会学家布鲁默认为集合行为的信息运动方式是“循环反应”,一方的刺激成为另一方的反应,而另一方的反应则又反过来成为这一方的刺激的循环往复过程。

传播学复习题公司内部档案编码:[OPPTR-OPPT28-OPPTL98-OPPNN08]《传播学》复习题绿色字体表示没有找到第一章关于传播的基本概念1、关于传播概念的几种学说——共享说、传递行为说、影响说、社会互动性说,具体含义。

答;共享说:着眼于传播的内容信息的共享。

传递行为说:着眼于思想情感的交换,传播就被描述为信息的“传递行为或过程”。

影响说或劝服说:把传播描述为影响他人的过程,认为传播是有意识地影响他人的劝服行为或过程社会互动性说:传播必然使双方互相联系,相互作用(传播是社会关系的体现)2、按照信息传受范围的大小,传播学通常把传播分为哪五种类型答:人内传播人际传播群体传播组织传播大众传播3、传播媒介的发展是一个不断体外化的过程:示现的媒介系统,即人们面对面传递信息的媒介;再现的媒介系统,在这一类系统中,对信息的生产和传播者来说需要使用物质工具或机器,但对信息接收者来说则不需要;机器媒介系统,这些媒介,不但传播一方需要使用机器,接收一方也必须使用机器。

4、传播学的四大先驱及其主要理论。

施拉姆对传播学的主要贡献。

1拉斯韦尔的宣传与传播研究现代政治科学的倡始人之一,提出社会传播的三项基本功能:环境监控,社会协调,文化传承。

SW模式:搭建了传播学的理论框架《社会传播的结构和功能》中提出Who 谁控制分析Say what 说什么内容分析In which channel 通过的渠道媒介分析To whom 对谁说受众With what effect 产生什么效果效果分析2卢因“把关人”研究提出了信息传播中的“把关人”(gatekeeper)概念。

“把关人”理论成为揭示新闻或信息传播过程内在的控制和机制的一种重要理论。

3霍夫兰与劝服效果实验把心理试验方法引进传播学领域。

揭示了传播效果形成的条件性和复习杂性,以否认早起的“枪弹论”效果观提供了重要依据。

4拉扎斯菲尔德与经验性传播学研究他是对穿鼻血影响最大的奠基人;“两级传播”理论的提出,不断改进抽样调查技术和量化分析方法,把传播学引向了经验性研究的方向(实证主义方向)施拉姆对传播学的贡献传播学科的创立《大众传播学》《传播学概论》《报刊的四种理论》①他使传播科学从梦想变成了现实,他是传播学的创立者;②他是集大成者;③是第一个具有创建“传播学”这样一个独立学科的明确意识并为之奋斗终生的人;④他建立4个专门传播研究机构、编辑、出版了近30部的着作;⑤1949年出版《大众传播学》;⑥1956报刊的四种理论5、传播中意义交换的前提,即交换的双方必须要有共通的意义空间。

拉斯韦尔与他对传播学的贡献哈罗德·拉斯韦尔(Harold Lasswell,1902----1977)是一位著名的政治学家,也够得上是一位社会学家、心理学家和传播学者。

传记作家形容他为“犹如行为科学的达芬奇”。

一般学习传播学的人了解他都是由于他在《传播在社会中的结构与功能》论文中的“一句话”、“三功能”来认定他在传播学中的创始人地位。

这一句震憾学术界的话就是:“谁?说些什么?通过什么渠道?对谁说?有什么效果?”从而引申出“控制分析、内容分析、媒介分析、受众分析和效果分析”五大研究课题,并长期左右着美国的传播学研究方向。

三种功能为:监视社会环境、协调社会关系、传衍社会遗产。

尽管后来传播学者认为拉氏的论述需要作进一步补充和完善,但其影响是巨大而深远的。

除此之外。

拉斯韦尔利用心理学,政治学,社会学来解读和研究传播学理论,对传播学的发展做出了巨大贡献,他也因此被认为是传播学四大奠基人之一。

拉斯韦尔的生平拉斯韦尔1902年2月13日出生于美国伊利诺斯洲唐尼尔逊的一个牧师家庭。

家境优裕,藏书甚丰。

1922年,他在芝加哥大学获哲学学士学位后,赴欧洲英、法、德等国著名大学攻读研究生课程,最后获得博士学位。

其间,他曾去柏林大学学习心理分析学说,并最先向美国学界引介了弗洛伊德心理分析理论,其《世界政治与个人不安全感》(1953)一书也深受弗氏理论的影响。

1927年,在芝加哥大学政治系任教的拉斯韦尔正式出版了他的博士论文《世界大战时期的宣传技巧》,随即在学术界引起反响。

该书描述和分析了第一次世界大战中各交战国之间的宣传战,断定宣传能产生很大的社会影响力。

1935年,他又与人合写和合编了《世界革命的宣传》和《宣传与推行》两本书,用科学的方法分析和研究宣传的功能及其社会控制,探讨宣传的本质和规律。

1946年,拉斯韦尔和史密斯合著了《宣传、传播和舆论》一书,认为宣传只是信息传播的一种特殊形态,而大众传播研究的范围要广得多,包括报刊、广播、书籍、电影、告示以及歌曲、戏剧、演讲等等。

传播的基本社会功能传播对人类社会发挥着重要的作用。

1948年,传播学家拉斯韦尔概括了人类传播的三项基本社会功能:1)环境监控功能。

自然和社会环境是在不断变化的,人类必须及时了解和把握环境的变化,以便调节自己的行为来适应这些变化。

传播起着一种“瞭望哨”的作用,帮助人类及时收集和提供关于环境变化的信息。

2)社会协调功能。

社会是一个建立在分工与协作基础上的有机体,只有实现了社会各部分的沟通、协调与统一,才能作为一个整体有效地适应内外环境的变化。

传播是社会的“神经系统”,有了这个系统,社会才能实现正常运转。

3)文化传承功能。

有了高度发达的传播系统,前人的文化遗产、经验、智慧、知识才能被记录、积累、流传下来,后人才能在前人的基础上进一步发展,传播对维持人类社会、国家和民族的存续和发展起着重要作用。

在拉斯韦尔概括的三种功能的基础上,传播学家赖特在1959年又补充了第四项功能,即“提供娱乐”,并称为“传播的四项基本社会功能”。

施拉姆又在此基础上指出了传播的经济功能,指出大众传播能够开创经济行为。

52.语义空间即语言意义的世界,一般来说,信息是意义和符号的统一体,内在的意义只有通过一定的外在形式(动作、表情、文字、音声、图画、影像等符号)才能表达出来。

因此,每一种符号体系在广义上都是传达意义的语言,它们所表达的意义构成了特定的语义空间。

传播既是在社会空间进行的,也是在语义空间中进行的;传播得以实现的一个前提条件就是传受双方必须要有共通的语义空间,即对符号含义的共同理解或拥有共同的文化背景,否则传播过程本身便不能成立,或传而不通,或招来误解。

因此,语义空间也是传播效果研究的一个重要概念。

53.人际影响即群体内个人对个人的影响,拉扎斯菲尔德、卡兹在四、五十年代的研究表明,在人们就公共事务、购物、时尚等领域的具体问题作出自己的选择和决策之际,这些选择和决策与其说是接受了大众传播的影响,倒不如说是在更大程度上接受了群体内其他成员的个人影响。

The structure and function of communication in societyHarold sswellThe act of communicationConvenient way to describe an act of communication is to answer the following questions:WhoSays WhatIn Which ChannelTo WhomWith What Effect?The scientific study of the process of communication tends to concentrate upon one or another of these questions. Scholars who study the "who," the communicator, look into the factors that initiate and guide the act of communication . We call this subdivision of the field of research control analysis. Specialists who focus upon the "says what" engage in content analysis. Those who look primarily at the radio, press, film, and other channels of communication are doing media analysis (p. 84). When the principal concern is with the persons reached by the media, we speak of audience analysis. If the question is the impact upon audiences, the problem is effect analysis.Whether such distinctions are useful depends entirely upon the degree of refinement which is regarded as appropriate to a given scientific and managerial objective. Often it is simpler to combine audience and effect analysis, for instance, than to keep them apart. On the other hand, we may want to concentrate on the analysis of content, and for this purpose subdivide the field into the study of purport and style, the first referring to the message, and the second to the arrangement of the elements of which the message iscomposed.Structure and functionEnticing as it is to work out these categories in more detail, the present discussion has a different scope. We are less interested in dividing up the act of communication than in viewing the act as a whole in relation to the entire social process. Any process can be examined in two frames of reference, namely, structure and function; and our analysis of communication will deal with the specializations that carry on certain functions, of which the following may be clearly distinguished: (i) the surveillance of the environment; (2) the correlation of the parts of society in responding to theenvironment; (3) the transmission of the social heritage from one generation to the next.Biological equivalencesAt the risk of calling up false analogies, we can gain perspective on human societies when we note the degree to which communication is a feature of life at every level. A vital entity, whether relatively isolated or in association, has specialized ways of receiving stimuli from the environment. The single-celled organism or the many-membered group tends to maintain an internal equilibrium and to respond to changes in the environment in a way that maintains this equilibrium. The responding process calls for specialized ways of bringing the parts of the whole into harmonious action (p. 85). Multi-celled animals specialize cells to the function of external contact and internal correlation. Thus, among the primates, specialization is exemplified by organs such as the ear and eye, and the nervous system itself. When the stimuli receiving and disseminating patterns operate smoothly, the several parts of the animal act in concert in reference to the environment ("feeding," "fleeing," "attacking").In some animal societies certain members perform specialized roles, and survey the environment. Individuals act as "sentinels," standing apart from the herd or flock and creating a disturbance whenever an alarming change occurs in the surroundings. The trumpeting, cackling, or shrilling of the sentinel is enough to set the herd in motion. Among the activities engaged in by specialized "leaders" is the internal stimulation of "followers" to adapt in an orderly manner to the circumstances heralded by the sentinels.Within a single, highly differentiated organism, incoming nervous impulses and outgoing impulses are transmitted along fibers that make synaptic junction with other fibers. The critical points in the process occur at the relay stations, where the arriving impulse may be too weak to reach the threshold which stirs the next link into action. At the higher centers, separate currents modify one another, producing results that differ in many ways from the outcome when each is allowed to continue a separate path. At any relay station there is no conductance, total conductance, or intermediate conductance. The same categories apply to what goes on among members of an animal society. The sly fox may approach the barnyard in a way that supplies too meager stimuli for the sentinel to sound the alarm. Or the attacking animal may eliminate the sentinel before he makes more than a feeble outcry. Obviously there is every gradation possible between total conductance and no conductance (p. 86).Attention in World SocietyWhen we examine the process of communication of any state in the world community, we note three categories of specialists. One group surveys the political environment of the state as a whole, another correlates the response of the whole state to the environment, and the third transmits certain patterns of response from the old to the young. Diplomats, attaches, and foreign correspondents are representative of those who specialize on the environment. Editors, journalists, and speakers are correlators of the internal response. Educators in family and school transmit the social inheritance.Communications which originate abroad pass through sequences in which various senders and receivers are linked with one another. Subject to modification at each relay point in the chain, messages originating with a diplomat or foreign correspondent may pass through editorial desks and eventually reach large audiences.If we think of the world attention process as a series of attention frames, it is possible to describe the rate at which comparable content is brought to the notice of individuals and groups. We can inquire into the point at which "conductance" no longer occurs; and we can look into the range between "total conductance" and "minimum conductance." The metropolitan and political centers of the world have much in common with the interdependence, differentiation, and activity of the cortical or subcortical centers of an individual organism. Hence the attention frames found in these spots are the most variable, refined, and interactive of all frames in the world community.At the other extreme are the attention frames of primitive inhabitants of isolated areas. Not that folk cultures are wholly untouched by industrial civilization. Whether we parachute into the interior of New Guinea, or land on the slopes of the Himalayas, we find no tribe wholly out of contact with the world. The long threads of trade, of missionary zeal, of adventurous exploration and scientific field study, and of global war reach far distant places. No one is entirely out of this world (p. 87).Among primitives the final shape taken by communication is the ballad or tale. Remote happenings in the great world of affairs, happenings that come to the notice of metropolitan audiences, are reflected, however dimly, in the thematic material of ballad singers and reciters. In these creations faraway political leaders may be shown supplying land to the peasants or restoring an abundance of game to the hills.When we push upstream of the flow of communication, we note that the immediate relay function for nomadic and remote tribesmen is sometimes performed by the inhabitants of settled villages with whom they come in occasional contact. The re-layer can be the school teacher, doctor, judge, tax collector, policeman, soldier, peddler, salesman, missionary, student; in any case he is an assembly point of news and comment.More detailed equivalencesThe communication processes of human society, when examined in detail, reveal many equivalences to the specializations found in the physical organism and in the lower animal societies. The diplomats, for instance, of a single state are stationed all over the world and send messages to a few focal points. Obviously, these incoming reports move from the many to the few, where they interact upon one another. Later on, the sequence spreads fanwise according to a few-to-many pattern, as when a foreign secretary gives a speech in public, an article is put out in the press, or a news film is distributed to the theaters. The lines leading from the outer environment of the state are functionally equivalent to the afferent channels that convey incoming nervous impulses to the central nervous system of a single animal, and to the means by which alarm is spread among a flock. Outgoing, or efferent, impulses display corresponding parallels.The central nervous system of the body is only partly involved in the entire flow of afferent-efferent impulses. There are automatic systems that can act on one another without involving the "higher" centers at all (p. 88). The stability of the internal environment is maintained principally through the mediation of the vegetive or autonomic specializations of the nervous system. Similarly, most of the messages within any state do not involve the central channels of communication. They take place within families, neighborhoods, shops, field gangs, and other local contexts. Most of the educational process is carried on the same way.A further set of significant equivalences is related to the circuits of communication , which are predominantly one-way or two-way, depending upon the degree of reciprocity between communicators and audience. Or, to express it differently, two-way communication occurs when the sending and receiving functions are performed with equal frequency by two or more persons. A conversation is usually assumed to be a pattern of two-way communication (although monologues are hardly unknown). The modern instruments of mass communication give an enormous advantage to the controllers of printing plants, broadcasting equipment, and other forms of fixed and specialized capital. But it should be noted that audiences do "talk back," after some delay; and many controllers of mass media use scientific methods of sampling in order to expedite this closing of the circuit.Circuits of two-way contact are particularly in evidence among the great metropolitan, political, and cultural centers of the world. New York, Moscow, London, and Paris, for example, are in intense two-way contact, even when the flow is severely curtailed in volume (as between Moscow and New York). Even insignificant sites become world centers when they are transformed into capital cities (Canberra, Australia; Ankara, Turkey; the District of Columbia, U.S.A.). A cultural center like Vatican City is in intense two-way relationship with the dominant centers throughout the world. Even specialized production centers like Hollywood, despite theirpreponderance of outgoing material, receive an enormous volume of messages.A further distinction can be made between message controlling and message handling centers and social formations. The (p. 89) message center in the vast Pentagon Building of the War Department in Washington transmits with no more than accidental change incoming messages to addressees. This is the role of the printers and distributors of books; of dispatchers, linemen, and messengers connected with telegraphic communication ; of radio engineers and other technicians associated with broadcasting. Such message handlers may be contrasted with those who affect the content of what is said, which is the communication of editors, censors, and propagandists. Speaking of the symbol specialists as a whole, therefore, we separate them into the manipulators (controllers) and the handlers; the first group typically modifies content, while the second does not.Needs and valuesThough we have noted a number of functional and structural equivalences between communication in human societies and other living entities, it is not implied that we can most fruitfully investigate the process of communication in America or the world by the methods most appropriate to research on the lower animals or on single physical organisms. In comparative psychology when we describe some part of the surroundings of a rat, cat, or monkey as a stimulus (that is, as part of the environment reaching the attention of the animal), we cannot ask the rat; we use other means of inferring perception. When human beings are our objects of investigation, we can interview the great "talking animal." (This is not that we take everything at face value. Sometimes we forecast the opposite of what the person says he intends to do. In this case, we depend on other indications, both verbal and nonverbal.)In the study of living forms, it is rewarding, as we have said, to look at them as modifiers of the environment in the process of gratifying needs, and hence of maintaining a steady state of internal equilibrium. Food, sex, and other activities which involve the environment can be examined on a comparative basis. Since human beings exhibit speech reactions, we can investigate many more relationships than in the nonhuman species (p. 90). Allowing for the data furnished by speech (and other communicative acts), we can investigate human society in terms of values; that is, in reference to categories of relationships that are recognized objects of gratification. In America, for example, it requires no elaborate technique of study to discern that power and respect are values. We can demonstrate this by listening to testimony, and by watching what is done when opportunity is afforded.It is possible to establish a list of values current in any group chosen for investigation. Further than this, we can discover the rank order in which these values are sought. We can rank the members of the group according to their positions in relation to the values. So far as industrial civilization is concerned, we have no hesitation in saying that power, wealth, respect, wellbeing, and enlightenment are among the values. If we stop with this list, which is not exhaustive, we can describe on the basis of available knowledge (fragmentary though it may often be) the social structure of most of the world. Since values are not equally distributed, the social structure reveals more or less concentration of relatively abundant shares of power, wealth, and other values in a few hands. In some places this concentration is passed on from generation to generation, forming castes rather than a mobile society.In every society the values are shaped and distributed according to more or less distinctive patterns (institutions). The institutions include communications which are invoked in support of the network as a whole. Such communications are the ideology; and in relation to power we can differentiate the political doctrine, the political formula, and the miranda. These are illustrated in the United States by the doctrine of individualism, the paragraphs of the Constitution, which are the formula, and the ceremonies and legends of public life, which comprise the Miranda (p. 91). The ideology is communicated to the rising generation through such specialized agencies as the home and school.Ideology is only part of the myths of any given society. There may be counterideologies directed against the dominant doctrine, formula, and miranda. Today the power structure of world politics is deeply affected by ideological conflict, and by the role of two giant powers, the United States and Russia. The ruling elites view one another as potential enemies, not only in the sense that interstate differences may be settled by war, but in the more urgent sense that the ideology of the other may appeal to disaffected elements at home and weaken the internal power position of each ruling class.Social conflict and communicationUnder the circumstances, one ruling element is especially alert to the other, and relies upon communication as a means of preserving power. One function of communication, therefore, is to provide intelligence about what the other elite is doing, and about its strength. Fearful that intelligence channels will be controlled by the other, in order to withhold and distort, there is a tendency to resort to secret surveillance. Hence international espionage is intensified above its usual level in peacetime. Moreover, efforts are made to "black out" the self in order to counteract the scrutiny of the potential enemy.In addition, communication is employed affirmatively for the purpose of establishing contact with audiences within the frontiers of the other power. These varied activities are manifested in the use of open and secret agents to scrutinize the other, in counterintelligence work, in censorship and travel restriction, in broadcasting and other informational activities across frontiers.Ruling elites are also sensitized to potential threats in the internal environment. Besides using open sources of information, secret measures are also adopted. Precautions are taken to impose "security" upon as many policy matters as possible. At the same time, the ideology of the elite is reaffirmed, and counter-ideologies are suppressed (p. 92).The processes here sketched run parallel to phenomena to be observed throughout the animal kingdom. Specialized agencies are used to keep aware of threats and opportunities in the external environment. The parallels include the surveillance exercised over the internal environment, since among the lower animals some herd leaders sometimes give evidence of fearing attack on two fronts, internal and external; they keep an uneasy eye on both environments. As a means of preventing surveillance by an enemy, wellknown devices are at the disposal of certain species, e.g., the squid's use of a liquid fog screen, the protective coloration of the chameleon. However, there appears to be no correlate of the distinction between the "secret" and "open" channels of human society.Inside a physical organism the closest parallel to social revolution would be the growth of new nervous connections with parts of the body that rival, and can take the place of, the existing structures of central integration. Can this be said to occur as the embryo develops in the mother's body? Or,if we take a destructive, as distinct from a reconstructive, process, can we properly say that internal surveillance occurs in regard to cancer, since cancers compete for the food supplies of the body?Efficient communicationThe analysis up to the present implies certain criteria of efficiency or inefficiency in communication. In human societies the process is efficient to the degree that rational judgments are facilitated. A rational judgment implements value goals. In animal societies communication is efficient when it aids survival, or some other specified need of the aggregate. The same criteria can be applied to the single organism.One task of a rationally organized society is to discover and control any factors that interfere with efficient communication. Some limiting factors are psychotechnical. Destructive radiation, for instance, may be present in the environment, yet remain undetected owing to the limited range of the unaided organism (p. 93).But even technical insufficiencies can be overcome by knowledge. In recent years shortwave broadcasting has been interfered with by disturbances which will either be surmounted, or will eventually lead to the abandonment of this mode of broadcasting. During the past few years advances have been made toward providing satisfactory substitutes for defective hearing and seeing. A less dramatic, though no less important, development has been the discovery of how inadequate reading habits can be corrected.There are, of course, deliberate obstacles put in the way of communication, like censorship and drastic curtailment of travel. To some extent obstacles can be surmounted by skillful evasion, but in the long run it will doubtless be more efficient to get rid of them by consent or coercion.Sheer ignorance is a pervasive factor whose consequences have never been adequately assessed. Ignorance here means the absence, at a given point in the process of, communication of knowledge which is available elsewhere in society. Lacking proper training, the personnel engaged in gathering and disseminating intelligence is continually misconstruing or overlooking the facts, if we define the facts as what the objective, trained observer could find.In accounting for inefficiency we must not overlook the low evaluations put upon skill in relevant communication. Too often irrelevant, or positively distorting, performances command prestige. In the interest of a "scoop," the reporter gives a sensational twist to a mild international conference, and contributes to the popular image of international politics as chronic, intense conflict, and little else. Specialists in communication often fail to keep up with the expansion of knowledge about the process; note the reluctance with which many visual devices have been adopted. And despite research on vocabulary, many mass communicators select words that fail. This happens, for instance, when a foreign correspondent allows himself to become absorbed in the foreign scene and forgets that his home audience has no direct equivalents in experience for "left," "center," and other factional terms (p. 94).Besides skill factors, the level of efficiency is sometimes adversely influenced by personality structure. An optimistic, outgoing person may hunt "birds of a feather" and gain an un-corrected and hence exaggeratedly optimistic view of events. On the contrary, when pessimistic, brooding personalities mix, they choose quite different birds, who confirm their gloom. There are also important differences among people which spring from contrasts in intelligence and energy.Some of the most serious threats to efficient communication for the community as a whole relate to the values of power, wealth, and respect. Perhaps the most striking examples of power distortion occur when the content of communication is deliberately adjusted to fit an ideology or counterideology. Distortions related to wealth not only arise from attemptsto influence the market, for instance, but from rigid conceptions of economic interest. A typical instance of inefficiencies connected with respect (social class) occurs when an upper-class person mixes only with persons of his own stratum and forgets to correct his perspective by being exposed to members of other classes.Research in communicationThe foregoing reminders of some factors that interfere with efficient communication point to the kinds of research, which can usefully be conducted on representative links in the chain of communication. Each agent is a vortex of interacting environmental and predispositional factors. Whoever performs a relay function can be examined in relation to input and output. What statements are brought to the attention of the relay link? What does he pass on verbatim? What does he drop out? What does he rework? What does he add? How do differences in input and output correlate with culture and personality? By answering such questions it is possible to weigh the various factors in conductance, no conductance, and modified conductance (p. 95). Besides the relay link, we must consider the primary link in a communication sequence. In studying the focus of attention of the primary observer, we emphasize two sets of influences: statements to which he is exposed; other features of his environment. An attache or foreign correspondent exposes himself to mass media and private talk; also, he can count soldiers, measure gun emplacements, note hours of work in a factory, see butter and fat on the table.Actually it is useful to consider the attention frame of the relay as well as the primary link in terms of media and nonmedia exposures. The role of nonmedia factors is very slight in the case of many relay operators, while it is certain to be significant in accounting for the primary observer.Attention Aggregates and PublicsIt should be pointed out that everyone is not a member of the world public, even though he belongs to some extent to the world attention aggregate. To belong to an attention aggregate it is only necessary to have common symbols of reference. Everyone who has a symbol of reference for New York, North America, the western hemisphere, or the globe is a member respectively of the attention aggregate of New York, North America, the western hemisphere, the globe. To be a member of the New York public, however, it is essential to make demands for public action in New York, or expressly affecting New York.The public of the United States, for instance, is not confined to residents or citizens, since noncitizens who live beyond the frontier may try to influence American politics. Conversely, everyone who lives in theUnited States is not a member of the American public, since something more than passive attention is necessary. An individual passes from an attention aggregate to the public when he begins to expect that what he wants can affect public policy.Sentiment Groups and PublicsA further limitation must be taken into account before we can correctly classify a specific person or group as part of a public (p. 96). The demands made regarding public policy must be debatable. The world public is relatively weak and undeveloped, partly because it is typically kept subordinate to sentiment areas in which no debate is permitted on policy matters. During a war or war crisis, for instance, the inhabitants of a region are overwhelmingly committed to impose certain policies on others. Since the outcome of the conflict depends on violence, and not debate, there is no public under such conditions. There is a network of sentiment groups that act as crowds, hence tolerate no dissent.From the foregoing analysis it is clear that there are attention, public, and sentiment areas of many degrees of inclusive-ness in world politics. These areas are interrelated with the structural and functional features of world society, and especially of world power. It is evident, for instance, that the strongest powers tend to be included in the same attention area, since their ruling elites focus on one another as the source of great potential threat. The strongest powers usually pay proportionately less attention to the weaker powers than the weaker powers pay to them, since stronger powers are typically more important sources of threat, or of protection, for weaker powers than the weaker powers are for the stronger.The attention structure within a state is a valuable index of the degree of state integration. When the ruling classes fear the masses, the rulers do not share their picture of reality with the rank and file. When the reality picture of kings, presidents, and cabinets is not permitted to circulate through the state as a whole, the degree of discrepancy shows the extent to which the ruling groups assume that their power depends on distortion.Or, to express the matter another way, if the "truth" is not shared, the ruling elements expect internal conflict, rather than harmonious adjustment to the external environment of the state (p. 97). Hence the channels of communication are controlled in the hope of organizing the attention of the community at large in such a way that only responses will be forthcoming which are deemed favorable to the power position of the ruling classes.The Principle of Equivalent EnlightenmentIt is often said in democratic theory that rational public opinion depends upon enlightenment. There is, however, much ambiguity about the。