第七届翻译大赛英文原文

- 格式:doc

- 大小:41.50 KB

- 文档页数:6

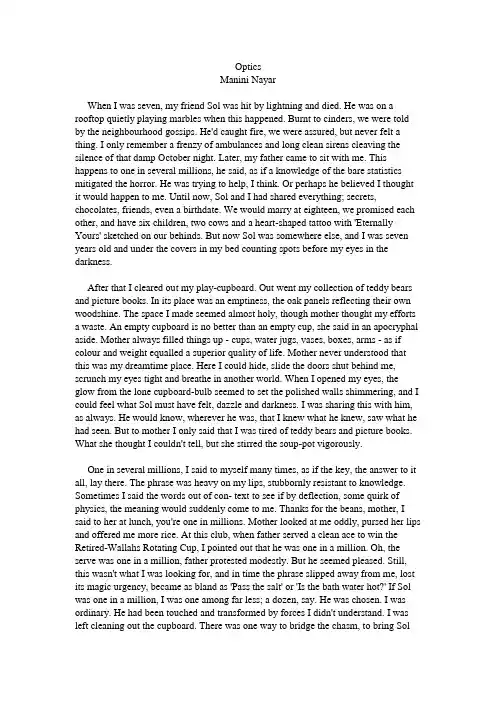

OpticsManini NayarWhen I was seven, my friend Sol was hit by lightning and died. He was on a rooftop quietly playing marbles when this happened. Burnt to cinders, we were told by the neighbourhood gossips. He'd caught fire, we were assured, but never felt a thing. I only remember a frenzy of ambulances and long clean sirens cleaving the silence of that damp October night. Later, my father came to sit with me. This happens to one in several millions, he said, as if a knowledge of the bare statistics mitigated the horror. He was trying to help, I think. Or perhaps he believed I thought it would happen to me. Until now, Sol and I had shared everything; secrets, chocolates, friends, even a birthdate. We would marry at eighteen, we promised each other, and have six children, two cows and a heart-shaped tattoo with 'Eternally Yours' sketched on our behinds. But now Sol was somewhere else, and I was seven years old and under the covers in my bed counting spots before my eyes in the darkness.After that I cleared out my play-cupboard. Out went my collection of teddy bears and picture books. In its place was an emptiness, the oak panels reflecting their own woodshine. The space I made seemed almost holy, though mother thought my efforts a waste. An empty cupboard is no better than an empty cup, she said in an apocryphal aside. Mother always filled things up - cups, water jugs, vases, boxes, arms - as if colour and weight equalled a superior quality of life. Mother never understood that this was my dreamtime place. Here I could hide, slide the doors shut behind me, scrunch my eyes tight and breathe in another world. When I opened my eyes, the glow from the lone cupboard-bulb seemed to set the polished walls shimmering, and I could feel what Sol must have felt, dazzle and darkness. I was sharing this with him, as always. He would know, wherever he was, that I knew what he knew, saw what he had seen. But to mother I only said that I was tired of teddy bears and picture books. What she thought I couldn't tell, but she stirred the soup-pot vigorously.One in several millions, I said to myself many times, as if the key, the answer to it all, lay there. The phrase was heavy on my lips, stubbornly resistant to knowledge. Sometimes I said the words out of con- text to see if by deflection, some quirk of physics, the meaning would suddenly come to me. Thanks for the beans, mother, I said to her at lunch, you're one in millions. Mother looked at me oddly, pursed her lips and offered me more rice. At this club, when father served a clean ace to win the Retired-Wallahs Rotating Cup, I pointed out that he was one in a million. Oh, the serve was one in a million, father protested modestly. But he seemed pleased. Still, this wasn't what I was looking for, and in time the phrase slipped away from me, lost its magic urgency, became as bland as 'Pass the salt' or 'Is the bath water hot?' If Sol was one in a million, I was one among far less; a dozen, say. He was chosen. I was ordinary. He had been touched and transformed by forces I didn't understand. I was left cleaning out the cupboard. There was one way to bridge the chasm, to bring Solback to life, but I would wait to try it until the most magical of moments. I would wait until the moment was so right and shimmering that Sol would have to come back. This was my weapon that nobody knew of, not even mother, even though she had pursed her lips up at the beans. This was between Sol and me.The winter had almost guttered into spring when father was ill. One February morning, he sat in his chair, ashen as the cinders in the grate. Then, his fingers splayed out in front of him, his mouth working, he heaved and fell. It all happened suddenly, so cleanly, as if rehearsed and perfected for weeks. Again the sirens, the screech of wheels, the white coats in perpetual motion. Heart seizures weren't one in a million. But they deprived you just the same, darkness but no dazzle, and a long waiting.Now I knew there was no turning back. This was the moment. I had to do it without delay; there was no time to waste. While they carried father out, I rushed into the cupboard, scrunched my eyes tight, opened them in the shimmer and called out'Sol! Sol! Sol!' I wanted to keep my mind blank, like death must be, but father and Sol gusted in and out in confusing pictures. Leaves in a storm and I the calm axis. Here was father playing marbles on a roof. Here was Sol serving ace after ace. Here was father with two cows. Here was Sol hunched over the breakfast table. The pictures eddied and rushed. The more frantic they grew, the clearer my voice became, tolling like a bell: 'Sol! Sol! Sol!' The cupboard rang with voices, some mine, some echoes, some from what seemed another place - where Sol was, maybe. The cup- board seemed to groan and reverberate, as if shaken by lightning and thunder. Any minute now it would burst open and I would find myself in a green valley fed by limpid brooks and red with hibiscus. I would run through tall grass and wading into the waters, see Sol picking flowers. I would open my eyes and he'd be there,hibiscus-laden, laughing. Where have you been, he'd say, as if it were I who had burned, falling in ashes. I was filled to bursting with a certainty so strong it seemed a celebration almost. Sobbing, I opened my eyes. The bulb winked at the walls.I fell asleep, I think, because I awoke to a deeper darkness. It was late, much past my bedtime. Slowly I crawled out of the cupboard, my tongue furred, my feet heavy. My mind felt like lead. Then I heard my name. Mother was in her chair by the window, her body defined by a thin ray of moonlight. Your father Will be well, she said quietly, and he will be home soon. The shaft of light in which she sat so motionless was like the light that would have touched Sol if he'd been lucky; if he had been like one of us, one in a dozen, or less. This light fell in a benediction, caressing mother, slipping gently over my father in his hospital bed six streets away. I reached out and stroked my mother's arm. It was warm like bath water, her skin the texture of hibiscus.We stayed together for some time, my mother and I, invaded by small night sounds and the raspy whirr of crickets. Then I stood up and turned to return to my room.Mother looked at me quizzically. Are you all right, she asked. I told her I was fine, that I had some c!eaning up to do. Then I went to my cupboard and stacked it up again with teddy bears and picture books.Some years later we moved to Rourkela, a small mining town in the north east, near Jamshedpur. The summer I turned sixteen, I got lost in the thick woods there. They weren't that deep - about three miles at the most. All I had to do was cycle forall I was worth, and in minutes I'd be on the dirt road leading into town. But a stir in the leaves gave me pause.I dismounted and stood listening. Branches arched like claws overhead. The sky crawled on a white belly of clouds. Shadows fell in tessellated patterns of grey and black. There was a faint thrumming all around, as if the air were being strung and practised for an overture. And yet there was nothing, just a silence of moving shadows, a bulb winking at the walls. I remembered Sol, of whom I hadn't thought in years. And foolishly again I waited, not for answers but simply for an end to the terror the woods were building in me, chord by chord, like dissonant music. When the cacophony grew too much to bear, I remounted and pedalled furiously, banshees screaming past my ears, my feet assuming a clockwork of their own. The pathless ground threw up leaves and stones, swirls of dust rose and settled. The air was cool and steady as I hurled myself into the falling light.光学玛尼尼·纳雅尔谈瀛洲译在我七岁那年,我的朋友索尔被闪电击中死去了。

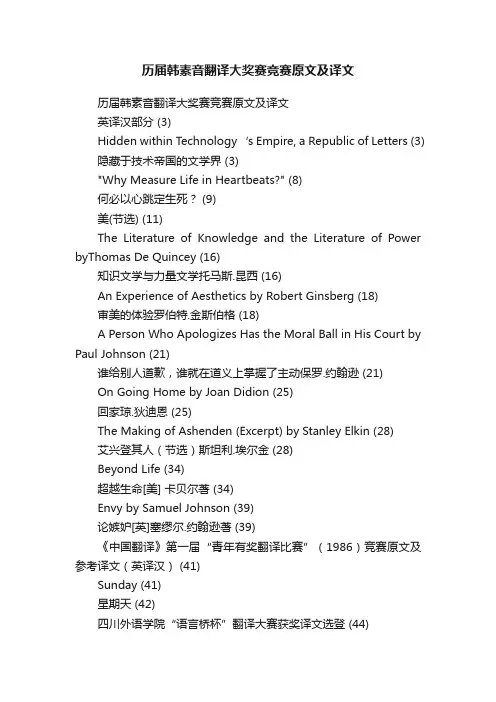

历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文英译汉部分 (3)Hidden within Technology‘s Empire, a Republic of Letters (3)隐藏于技术帝国的文学界 (3)"Why Measure Life in Heartbeats?" (8)何必以心跳定生死? (9)美(节选) (11)The Literature of Knowledge and the Literature of Power byThomas De Quincey (16)知识文学与力量文学托马斯.昆西 (16)An Experience of Aesthetics by Robert Ginsberg (18)审美的体验罗伯特.金斯伯格 (18)A Person Who Apologizes Has the Moral Ball in His Court by Paul Johnson (21)谁给别人道歉,谁就在道义上掌握了主动保罗.约翰逊 (21)On Going Home by Joan Didion (25)回家琼.狄迪恩 (25)The Making of Ashenden (Excerpt) by Stanley Elkin (28)艾兴登其人(节选)斯坦利.埃尔金 (28)Beyond Life (34)超越生命[美] 卡贝尔著 (34)Envy by Samuel Johnson (39)论嫉妒[英]塞缪尔.约翰逊著 (39)《中国翻译》第一届“青年有奖翻译比赛”(1986)竞赛原文及参考译文(英译汉) (41)Sunday (41)星期天 (42)四川外语学院“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (44)第七届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (44)The Woods: A Meditation (Excerpt) (46)林间心语(节选) (47)第六届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (50)第五届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛原文及获奖译文选登 (52)第四届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛原文、参考译文及获奖译文选登 (54) When the Sun Stood Still (54)永恒夏日 (55)CASIO杯翻译竞赛原文及参考译文 (56)第三届竞赛原文及参考译文 (56)Here Is New York (excerpt) (56)这儿是纽约 (58)第四届翻译竞赛原文及参考译文 (61)Reservoir Frogs (Or Places Called Mama's) (61)水库青蛙(又题:妈妈餐馆) (62)中译英部分 (66)蜗居在巷陌的寻常幸福 (66)Simple Happiness of Dwelling in the Back Streets (66)在义与利之外 (69)Beyond Righteousness and Interests (69)读书苦乐杨绛 (72)The Bitter-Sweetness of Reading Yang Jiang (72)想起清华种种王佐良 (74)Reminiscences of Tsinghua Wang Zuoliang (74)歌德之人生启示宗白华 (76)What Goethe's Life Reveals by Zong Baihua (76)怀想那片青草地赵红波 (79)Yearning for That Piece of Green Meadow by Zhao Hongbo (79)可爱的南京 (82)Nanjing the Beloved City (82)霞冰心 (84)The Rosy Cloud byBingxin (84)黎明前的北平 (85)Predawn Peiping (85)老来乐金克木 (86)Delights in Growing Old by Jin Kemu (86)可贵的“他人意识” (89)Calling for an Awareness of Others (89)教孩子相信 (92)To Implant In Our Children‘s Young Hearts An Undying Faith In Humanity (92)心中有爱 (94)Love in Heart (94)英译汉部分Hidden within Technology’s Empire, a Republic of Le tters 隐藏于技术帝国的文学界索尔·贝娄(1)When I was a boy ―discovering literature‖, I used to think how wonderful it would be if every other person on the street were familiar with Proust and Joyce or T. E. Lawrence or Pasternak and Kafka. Later I learned how refractory to high culture the democratic masses were. Lincoln as a young frontiersman read Plutarch, Shakespeare and the Bible. But then he was Lincoln.我还是个“探索文学”的少年时,就经常在想:要是大街上人人都熟悉普鲁斯特和乔伊斯,熟悉T.E.劳伦斯,熟悉帕斯捷尔纳克和卡夫卡,该有多好啊!后来才知道,平民百姓对高雅文化有多排斥。

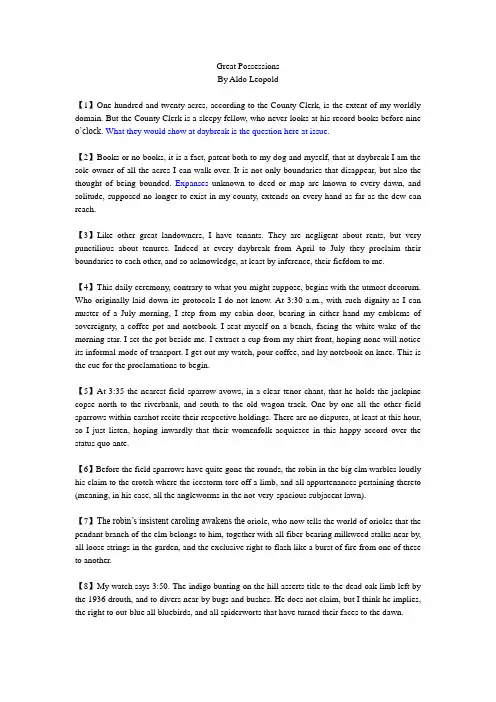

Great PossessionsBy Aldo Leopold【1】One hundred and twenty acres, according to the County Clerk, is the extent of my worldly domain. But the County Clerk is a sleepy fellow, who never looks at his record books before nine o’clock. What they would show at daybreak is the question here at issue.【2】Books or no books, it is a fact, patent both to my dog and myself, that at daybreak I am the sole owner of all the acres I can walk over. It is not only boundaries that disappear, but also the thought of being bounded.Expanses unknown to deed or map are known to every dawn, and solitude, supposed no longer to exist in my county, extends on every hand as far as the dew can reach.【3】Like other great landowners, I have tenants. They are negligent about rents, but very punctilious about tenures. Indeed at every daybreak from April to July they proclaim their boundaries to each other, and so acknowledge, at least by inference, their fiefdom to me.【4】This daily ceremony, contrary to what you might suppose, begins with the utmost decorum. Who originally laid down its protocols I do not know. At 3:30 a.m., with such dignity as I can muster of a July morning, I step from my cabin door, bearing in either hand my emblems of sovereignty, a coffee pot and notebook. I seat myself on a bench, facing the white wake of the morning star. I set the pot beside me. I extract a cup from my shirt front, hoping none will notice its informal mode of transport. I get out my watch, pour coffee, and lay notebook on knee. This is the cue for the proclamations to begin.【5】At 3:35 the nearest field sparrow avows, in a clear tenor chant, that he holds the jackpine copse north to the riverbank, and south to the old wagon track. One by one all the other field sparrows within earshot recite their respective holdings. There are no disputes, at least at this hour, so I just listen, hoping inwardly that their womenfolk acquiesce in this happy accord over the status quo ante.【6】Before the field sparrows have quite gone the rounds, the robin in the big elm warbles loudly his claim to the crotch where the icestorm tore off a limb, and all appurtenances pertaining thereto (meaning, in his case, all the angleworms in the not-very-spacious subjacent lawn).【7】The robin’s insistent caroling awakens the oriole, who now tells the world of orioles that the pendant branch of the elm belongs to him, together with all fiber-bearing milkweed stalks near by, all loose strings in the garden, and the exclusive right to flash like a burst of fire from one of these to another.【8】My watch says 3:50. The indigo bunting on the hill asserts title to the dead oak limb left by the 1936 drouth, and to divers near-by bugs and bushes. He does not claim, but I think he implies, the right to out-blue all bluebirds, and all spiderworts that have turned their faces to the dawn.【9】Next the wren – the one who discovered the knothole in the eave of the cabin – explodes into song. Half a dozen other wrens give voice, and now all is bedlam. Grosbeaks, thrashers, yellow warblers, bluebirds, vireos, towhees, cardinals – all are at it. My solemn list of performers, in their order and time of first song, hesitates, wavers, ceases, for my ear can no longer filter out priorities. Besides, the pot is empty and the sun is about to rise. I must inspect my domain before my title runs out.【10】We sally forth, the dog and I, at random. He has paid scant respect to all these vocal goings-on, for to him the evidence of tenantry is not song, but scent. Any illiterate bundle of feathers, he says, can make a noise in a tree. Now he is going to translate for me the olfactory poems that who-knows-what silent creatures have written in the summer night. At the end of each poem sits the author – if we can find him. What we actually find is beyond predicting: a rabbit, suddenly yearning to be elsewhere; a woodcock, fluttering his disclaimer; a cock pheasant, indignant over wetting his feathers in the grass.【11】Once in a while we turn up a coon or mink, returning late from the night’s foray. Sometimes we rout a heron from his unfinished fishing, or surprise a mother wood duck with her convoy of ducklings, headed full-steam for the shelter of the pickerelweeds. Sometimes we see deer sauntering back to the thickets, replete with alfalfa blooms, veronica, and wild lettuce. More often we see only the interweaving darkened lines that lazy hoofs have traced on the silken fabric of the dew.【12】I can feel the sun now. The bird-chorus has run out of breath. The far clank of cowbells bespeaks a herd ambling to pasture. A tractor roars warning that my neighbor is astir. The world has shrunk to those mean dimensions known to county clerks. We turn toward home, and breakfast.。

江西省第七届英语翻译大赛(初赛)试题(2015-9-24)一、请将下列短文译成汉语(50)分:All the wisdom of the ages, all the stories that have delighted mankind for centuries, are easily and cheaply available to all of us within the covers of books--but we must know how to avail ourselves of this treasure and how to get the most from it.I am most interested in people, in meeting them and finding out about them.Some of the most remarkable people I’ve met existed only in a writer’s imagination, then on the pages of his book,and then,again,in my imagination.I’ve found in books new friends, new societies, new worlds. If I am interested in people, others are interested not so much in who as in how.Who in the books includes everybody from science-fiction superman two hundred centuries in the future all the way back to the first figures in history. How covers everything from the ingenious explanations of Sherlock Holmes to the discoveries of science and ways of teaching manners to children.Reading is a pleasure of the mind, which means that it is a little like a sport: your eagerness and knowledge and quickness make you a good reader. Reading is fun ,not because the writer is telling you something, but because it makes your mind work. Your own imagination works along with the author’s or even goes beyond his. Your experience, comparedwith his ,brings you to the same or different conclusions, and your ideas develop as you understand his.Every book stands by itself, like a one-family house, but books in library are like houses in a city.Although they are separate, together they all add up to something; they are connected with each other and with other cities. The same ideas, or related ones, turn up in different places; the human problems that repeat themselves in life repeat themselves in literature, but with different solutions according to different writings at different times.Reading can only be fun if you expect ti to be. If you concentrate on books somebody tells you “ought” to read, you probably won’t have fun. But if you put down a book you don’t like and try another till you find one that means something to you ,and then relax with it,you will almost certainly have a good time--and if you become as a result of reading, better, wiser, kinder,or more gentle, you won’t have suffered during the process.二、请将下列短文译成英语(50)分从朋友口中,听到一则轶事。

中国诗歌翻译大赛英文作文英文:As a participant in the Chinese Poetry Translation Competition, I am excited to share my thoughts on the art of translating Chinese poetry into English. Translating poetry is a complex and challenging task, as it involves not only linguistic proficiency, but also a deep understanding of the cultural and historical context in which the original poem was written.One of the biggest challenges in translating Chinese poetry into English is capturing the nuances and subtleties of the original work. Chinese poetry is known for its rich imagery, symbolism, and allusions, which can be difficult to convey in a different language. For example, in the famous poem "静夜思" by 李白 (Li Bai), the line "床前明月光" evokes a sense of tranquility and beauty that is deeply rooted in Chinese culture. Finding the right words to convey the same emotions in English requires a deepunderstanding of both languages and cultures.Another challenge is maintaining the poetic form and rhythm of the original poem. Chinese poetry is oftenwritten in specific forms, such as the lüshi or the jueju, which have strict rules for rhyme and meter. When translating these poems into English, it can be difficult to find words that not only convey the meaning of the original poem, but also fit the poetic form. For example, in translating a lüshi poem, I had to carefully consider the syllable count and rhyme scheme in English to stay true to the original form.Despite these challenges, translating Chinese poetry into English is a deeply rewarding experience. It allows me to delve into the rich literary tradition of China and gain a deeper appreciation for the beauty and complexity of the Chinese language. Through the process of translation, I am able to explore the different ways in which language can convey emotions, thoughts, and experiences.中文:作为中国诗歌翻译大赛的参与者,我很高兴分享我对将中国诗歌翻译成英文的艺术的看法。

【翻译比赛原文】His First Day as Quarry-BoyBy Hugh Miller (1802~1856) It was twenty years last February since I set out, a little before sunrise, to make my first acquaintance with a life of labour and restraint; and I have rarely had a heavier heart than on that morning. I was but a slim, loose-jointed boy at the time, fond of the pretty intangibilities of romance, and of dreaming when broad awake; and, woful change! I was now going to work at what Burns has instanced, in his ‘Twa Dogs’, as one of the most disagreeable of all employments,—to work in a quarry. Bating the passing uneasinesses occasioned by a few gloomy anticipations, the portion of my life which had already gone by had been happy beyond the common lot. I had been a wanderer among rocks and woods, a reader of curious books when I could get them, a gleaner of old traditionary stories; and now I was going to exchange all my day-dreams, and all my amusements, for the kind of life in which men toil every day that they may be enabled to eat, and eat every day that they may be enabled to toil!The quarry in which I wrought lay on the southern shore of a noble inland bay, or frith rather, with a little clear stream on the one side, and a thick fir wood on the other. It had been opened in the Old Red Sandstone of the district, and was overtopped by a huge bank of diluvial clay, which rose over it in some places to the height of nearly thirty feet, and which at this time was rent and shivered, wherever it presented an open front to the weather, by a recent frost. A heap of loose fragments, which had fallen from above, blocked up the face of the quarry and my first employment was to clear them away. The friction of the shovel soon blistered my hands, but the pain was by no means very severe, and I wrought hard and willingly, that I might see how the huge strata below, which presented so firm and unbroken a frontage, were to be torn up and removed. Picks, and wedges, and levers, were applied by my brother-workmen; and, simple and rude as I had been accustomed to regard these implements, I found I had much to learn in the way of using them. They all proved inefficient, however, and the workmen had to bore into one of the inferior strata, and employ gunpowder. The process was new to me, and I deemed it a highly amusing one: it had the merit, too, of being attended with some such degree of danger as a boating or rock excursion, and had thus an interest independent of its novelty. We had a few capital shots: the fragments flew in every direction; and an immense mass of the diluvium came toppling down, bearing with it two dead birds, that in a recent storm had crept into one of the deeper fissures, to die in the shelter. I felt a new interest in examining them. The one was a pretty cock goldfinch, with its hood of vermilion and its wings inlaid with the gold to which it owes its name, as unsoiled and smooth as if it had been preserved for a museum. The other, a somewhat rarer bird, of the woodpecker tribe, was variegated with light blue and a grayish yellow. I was engaged in admiring the poor little things, more disposed to be sentimental, perhaps, than if I had been ten years older, and thinking of the contrast between the warmth and jollity of their green summer haunts, and the cold and darkness of their last retreat, when I heard our employer bidding the workmen lay by their tools. I looked up and saw the sun sinking behind the thick fir wood beside us, and the long dark shadows of the trees stretching downward towards the shore. —Old Red Sandstone(文章选自 THE OXFORD BOOK OF ENGLISH PROSE, 658-660, Oxford University Press, London, first published 1925, reprinted 1958.)。

第7届全国英语演讲比赛冠军得主英语演讲稿范文这篇第七届全国英语演讲比赛冠军得主英语演讲稿范文,是笔者特地为大家整理的,希望对大家有所帮助!To me March 28th was a lucky day. It was on that particularevening that I found myself at central stage, in thespotlight. Winning the 21st Century·Ericsson Cup SeventhNational English Speaking Competition is a memory that I shalltreasure and one that will surely stay.More important than winning the Cup is the friendship that hasbeen established and developed among the contestants, and thechance to communicate offstage in addition to competingonstage. Also the competition helps boost public speaking inChina, a skill hitherto undervalued.For me, though, the competition is a more personal experience.Habitually shy, I had been reluctant to take part in any suchactivities. Encouraged by my friends, however, I made alast-minute decision to give it a try. In the course ofpreparation I somehow rediscovered myself, a truer me.I found that, after all, I like communicating with otherpeople; that exchanging views can be so much fun—and so muchrewarding, both emotionally and intellectually; that publicspeaking is most effective when you are least guarded; andthat it is essential to success in every walk oflife.At a more practical level, I realized knowing what you aregoing to say and how you are going to say it are equallyimportant. To take the original ideas out of your head andtransplant them, so to speak, to that of others, you need tohave an organized mind. This ability improves with training.Yet there should not be any loss or addition or distortion inthe process. Those ideas that finally find their way intoanother head need to be recognizably yours. Language is ameans to transmit information, not a means to obstructcommunication. It should be lucid to be penetrating.In China, certain public speaking skills havebeen undulyemphasized. Will it really help, we are compelled to ask, tobang at the podium or yell at the top of your lungs, if youhave come with a poorly organized speech, a muddled mind, andunwillingness to truly share your views?Above all, the single most important thing I learnt was thatas a public speaker, you need to pay attention, first andforemost, to the content of your speech. And second, thestructure of your speech: how one idea relates and progressesto another.Only after these come delivery and non-verbal communication:speed control, platform manner, and so on. Pronunciation isimportant, yet of greater importance is this: Isyour languagecompetent enough to express your ideas exactly the way youintend them to be understood?I was informed afterwards that I was chosen to be the winnerfor my appropriately worded speech, excellent presence andquick-witted response. In so remarking, the judges clearlyshowed their preference: they come to listen for meaningfulideas, not for loose judgments, nor easy laughters.Some contestants failed to address their questions head on.Some were able to, but did not know where to stop—the draggingon betrayed their lack of confidence. The root cause was thatthey did not listen attentively to the questions. Or they werethinking of what they had prepared.As I said in my speech, It is vitally important that we youngpeople do more serious thinking ... to take them [issues likeglobalization] on and give them honest thinking is the firststep to be prepared for both opportunities and challengescoming our way. We need to respond honestly.A competition like this draws talented students from all overthe country. And of course, I learnt more things than justabout public speaking. Since in thfinal analysis, publicspeaking is all about effective communication. And this goestrue for all communications, whatever their setting.And the following is the final version of my speech:GLOBALIZATION:OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGESFOR CHINAS YOUNGER GENERATIONThirty years ago, American President Richard Nixon made anepoch-making visit to China, a country still isolated at thattime. Premier Zhou Enlai said to him, Your handshake cameover the vastest ocean in the world—twenty-five years of nocommunication. Thirty years since, China and America haveexchanged many handshakes. The fundamental implication of thisexample is that the need to communicate across differences inculture and ideology is not only felt by the two countries butmany other nations as well.As we can see today, environmentalists from differentcountries are making joint efforts to address the issue ofglobal warming, economists are seeking solutions to financialcrises that rage in a particular region but nonethelesscripple the world economy, and politicians and diplomats aregetting together to discuss the issue of combating terrorism.Peace and prosperity has become a common goal that we arestriving for all over the world. Underlying this mighty trendof global communication is the echo of E. M. Forsters wordsOnly connect!With the IT revolution, traditional boundaries of humansociety fall away. Our culture, politics, society and commerceare being sloshed into one large melting pot ofhumanity. Inthis interlinked world, there are no outsiders, for adisturbance in one place is likely to impact other parts ofthe globe. We have begun to realize that a world dividedcannot endure.China is now actively integrating into the world. Our recententry to the WTO is a good example. For decades, we have takenpride in being self-reliant, but now we realize the importanceof participating in and contributing to a broader economicorder. From a precarious role in the world arena to ourpresent WTO membership, we have come a long way.But what does the way ahead look like? In some parts of theworld people are demonstrating againstglobalization. Are theyjustified, then, in criticizing the globalizing world? Insteadof narrowing the gap between the rich and the poor, they say, globalization enables the developed nations to swallow the developing nations wealth in debts and interest. Globalization, they argue, should be about a common interest in every other nations economic health. We are reminded by Karl Marx that capital goes beyond national borders and eludes control from any other entity. This has become a reality. Multinational corporations are seeking the lowest cost, the largest market, and the most favourable policy. They are often powerful lobbyists in government decision-making, ruthless expansionists in the global market and a devastating presence to local businesses.For China, still more challenges exist. How are we going to ensure a smooth transition from the planned economy to a market-based one? How to construct a legal system that is sound enough and broad enough to respond to the needs of a dynamicsociety? How to maintain our cultural identity in an increasingly homogeneous world? And how to define greatness in our rise as a peace-loving nation? Globalization entails questions that concern us all. Like many young people my age in China, I want to see my country get prosperous and enjoy respect in te international community. But it seems to me that mere patriotism is not just enough. It is vitally important that we young people do more serious thinking and broaden our mind to bigger issues. There might never be easy answers to those issues such as globalization, but to take them on and give them honest thinking is the first step to be prepared for both opportunities and challenges coming our way. This is also one of the thoughts that came to me while preparing this speech.。

A Garden That Welcomes StrangersBy Allen LacyI do not know what became of her, and I never learned her name. But I feel that I knew her from the garden she had so lovingly made over many decades.我并不知道她的近况,以前也不曾得知她的名字。

然而我却觉得我从她几十年倾心照料的花园里了解了她。

The house she lived in lies two miles from mine – a simple, two-story structure with the boxy plan,steeply-pitched roof and unadorned lines that are typical of houses built in the middle of the nineteenth century near the New Jersey shore.她住在一所离我家两英里远的房子里——典型的十九世纪中页新泽西海边建筑:简单的双层结构,布局方正,房檐弯曲,线条古朴。

Her garden was equally simple. She was not a conventional gardener who did everything by the book, following the common advice to vary her plantings so there would be something in bloom from the first crocus in the spring to the last chrysanthemum in the fall. She had no respect for the rule that says that tall-growing plants belong at the rear of a perennial border, low ones in the front and middle-sized ones in the middle, with occasional exceptions for dramatic accent.她的花园也同样简单。

【翻译大赛原文】LimboBy Rhonda LucasMy parents’ divorce was final. The house had been sold and the day had come to move. Thirty years of the family’s life was now crammed into the garage. The two-by-fours that ran the length of the walls were the only uniformity among the clutter of boxes, furniture, and memories. All was frozen in limbo between the life just passed and the one to come.The sunlight pushing its way through the window splattered against a barricade of boxes. Like a fluorescent river, it streamed down the sides and flooded the cracks of the cold, cement floor. I stood in the doorway between the house and garage and wondered if the sunlight would ever again penetrate the memories packed inside those boxes. For an instant, the cardboard boxes appeared as tombstones, monuments to those memories.The furnace in the corner, with its huge tubular fingers reaching out and disappearing into the wall, was unaware of the futility of trying to warm the empty house. The rhythmical whir of its effort hummed the elegy for the memories boxed in front of me. I closed the door, sat down on the step, and listened reverently. The feeling of loss transformed the bad memories into not-so-bad, the not-so-bad memories into good, and committed the good ones to my mind. Still, I felt as vacant as the house inside.A workbench to my right stood disgustingly empty. Not so much as a nail had been left behind. I noticed, for the first time, what a dull, lifeless green it was. Lacking the disarray of tools that used to cover it, now it seemed as out of place as a bathtub in the kitchen. In fact, as I scanned the room, the only things that did seem to belong were the cobwebs in the corners.A group of boxes had been set aside from the others and stacked in front of the workbench. Scrawled like graffiti on the walls of dilapidated buildings were the words “Salvation Army.” Those words caught my eyes as effectively as a flashing neon sign. They reeked of irony. “Salvation - was a bit too late for this family,” I mumbled sarcastically to myself.The houseful of furniture that had once been so carefully chosen to complement and blend with the color schemes of the various rooms was indiscriminately crammed together against a single wall. The uncoordinated colors combined in turmoil and lashed out in the greyness of the room.I suddenly became aware of the coldness of the garage, but I didn’t want to go back inside the house, so I made my way through the boxes to the couch. I cleared a space to lie down and curled up, covering myself with my jacket. I hoped my father would return soon with the truck so we could empty the garage and leave the cryptic silence of parting lives behind.(选自Patterns: A Short Prose Reader,by Mary Lou Conlin, published by Houghton Mifflin, 1983.)。

中国诗歌翻译大赛英文作文英文,As a participant in the Chinese poetrytranslation competition, I have found the experience to be both challenging and rewarding. Translating poetry is not simply about finding the equivalent words in another language, but about capturing the essence and emotion of the original work.One of the most difficult aspects of translating Chinese poetry into English is the cultural differences and nuances in language. For example, in Chinese poetry, there are often references to historical events, myths, and traditions that may not have direct equivalents in English. As a translator, it is my responsibility to not only convey the literal meaning of the words, but also to provide context and explanation for the cultural references.In addition to the cultural challenges, there are also linguistic differences between Chinese and English that make translation a complex task. Chinese poetry oftenrelies on symbolism, metaphor, and wordplay, which may not always translate directly into English. For example, theuse of characters with multiple meanings in Chinese can create layers of interpretation that are difficult toconvey in English.Despite these challenges, I have found the process of translating Chinese poetry to be incredibly rewarding. It has allowed me to delve deeply into the rich literary traditions of China and to gain a deeper understanding of the language and culture. Through the act of translation, I have been able to appreciate the beauty and complexity of Chinese poetry in a new way.中文,作为中国诗歌翻译大赛的参与者,我发现这个经历既具有挑战性又具有回报性。

翻译大赛 1 第七届 “北京外国语大学-《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛英译汉一等奖译文开阔的领地文/[美)奥尔多利奥波德译/蒋怡颖按县书记员的话来说,眼前一百二十英亩的农场是我的领地。

不过,这家伙可贪睡了,不到日上三竿,是断然不会翻看他那些记录薄的。

那么拂晓时分,农场是怎样的一番景象,是个值得讨论的问题。

管他有没有记录在册呢,反正破晓时漫步走过的每一英亩土地都由我一人主宰,这一点我的爱犬也心领神会。

地域上的重重界限消失了,那种被秷楛的压抑感也随之抛诸脑后。

契据和地图上没法标明的无边光景[1],其美妙展现在每天的黎明时分。

而那份独处的悠然,我本以为在这沙郡中已觅而不得,却不想在每一颗露珠上寻到了它的踪影。

和其他大农场主一样,我也有不少佃户。

他们不在乎租金这事,划起领地来却毫不含糊。

从四月到七月,每天拂晓时刻,他们都会向彼此宣告领地界限,同时以此表明他们对我的臣服。

这样的仪式天天有,都在极庄严的礼节中拉开帷幕,这恐怕和你所设想的大相径庭。

究竟是何方神圣立下这些规矩礼仪,我不得而知。

凌晨三点半,我从这七月的拂晓中汲取了威严,昂扬地走出小屋,一手端着咖啡壶,一手拿着笔记本,这两样象征了我对农场的主权。

望着那颗闪烁着白色光辉的启明星,我在一张长椅上坐下,咖啡壶先搁在一旁,又从衬衣前襟的口袋里取出一只杯子,但愿没人注意到,这么携带杯子确实有点随意。

我掏出手表,给自己倒了杯咖啡,接着把笔记本放在膝盖上。

一切就绪,这意味着仪式即将开始。

三点三十五分到了,离我最近的一只原野春雀用清澈的男高音吟唱起来,宣告北到河岸、南至古老马车道的这片短叶松树林,统统都归他所有。

附近的原野春雀也应声唱起歌来,一只接一只地声明着自己的领地。

歌声里没有争执,至少此时此刻没有。

我就这么聆听着,打心眼里希望在这幸福和谐中,他们的雌雀伴侣也能默许原先的领地划分。

原野春雀的吟唱声还在林中回荡,而这边大榆树上的知更鸟已开始鸣l转,歌声哦亮,他在宣告,这被冰暴[2]折断了枝丫的树权是他的地盘,当然附带着周围的一些也归他所有(对这只知更鸟而言,其实就是指树下草地里的所有蚚划,那里并不算宽敞)。

附件3翻译竞赛中译英参赛原文一、向美好的旧日时光道歉美好的旧日时光,渐行渐远。

在我的稿纸上,它们是代表怅惘的省略的句点;在我的书架上,它们是那本装帧精美,却蒙了尘灰的诗集;在我的抽屉里,它们是那张每个人都在微笑的合影;在我的梦里,它们是我梦中喊出的一个个名字;在我的口袋里,它们是一句句最贴心的劝语忠言……现在,我坐在深秋的藤椅里,它们就是纷纷坠落的叶子。

我尽可能接住那些叶子,不想让时光把它们摔疼了。

这是我向它们道歉的唯一方式。

向纷纷远去的友人道歉,我不知道一封信应该怎样开头,怎样结尾。

更不知道,字里行间,应该迈着怎样的步子。

向得而复失的一颗颗心道歉。

我没有珍惜你们,唯有期盼,上天眷顾我,让那一颗颗真诚的心,失而复得。

向那些正在远去的老手艺道歉,我没能看过一场真正的皮影戏,没能找一个老木匠做一个碗柜,没能找老裁缝做一个袍子,没能找一个“剃头担子”剃一次头……向美好的旧日时光道歉,因为我甚至没有时间怀念,连梦都被挤占了。

琐碎这样一个词仿佛让我看到这样一个老人,在异国他乡某个城市的下午,凝视着广场上淡然行走的白鸽,前生往事的一点一滴慢慢涌上心来:委屈、甜蜜、心酸、光荣……所有的所有在眼前就是一些琐碎的忧郁,却又透着香气。

其实生活中有很多让人愉悦的东西,它们就是那些散落在角落里的不起眼的碎片,那些暗香,需要唤醒,需要传递。

就像两个人的幸福,可以很小,小到只是静静地坐在一起感受对方的气息;小到跟在他的身后踩着他的脚印一步步走下去;小到用她准备画图的硬币去猜正反面;小到一起坐在路边猜下一个走这条路的会是男的还是女的……幸福的滋味,就像做饭一样,有咸,有甜,有苦,有辣,口味多多,只有自己体味得到。

但人性中也往往有这样的弱点:回忆是一个很奇怪的筛子,它留下的总是自己的好和别人的坏。

所以免不了心浮气躁,以至于总想从镜子里看到自己十年后的模样。

现在,十年后的自己又开始怀想十年前的模样了,因为在鬓角,看见了零星的雪。

江西省第七届英语翻译大赛决赛试题及参考答案江西省第七届英语翻译大赛决赛I. 英译中It was a cold grey day in late November. The weather had changed overnight, when a backing wind brought a granite sky and a mizzling rain with it, and although it was now only a little after two o’clock in the afternoon the pallour of a winter evening seemed to have closed upon the hills, cloaking them in mist. It would be dark by four. The air was clammy cold, and for all the tightly closed windows it penetrated the interior of the coach. The leather seats felt damp to the hands, and there must have been a small crack in the roof, because now and again little drips of rain fell softly through, smudging the leather and leaving a dark blue stain like a splodge of ink. The wind came in gusts, at times shaking the coach as it travelled round the bend of the road, and in the exposed places on the high ground it blew with such force that the whole body of the coach trembled and swayed, rocking between the high wheels like a drunken man.The driver, muffled in a greatcoat to his ears, bent almost double in his seat, in a faint endeavour to gain shelter from his own shoulders, while the dispirited horses plodded sullenly to his command, too broken by the wind and the rain to feel the whip that now and again cracked above their heads, while it swung between the numb fingers of the driver.The wheels of the coach creaked and groaned as they sank onto the ruts on the road, and sometimes they flung up the soft spattered mud against the windows, where it mingled with the constant driving rain, and whatever view there might have been of the countryside was hopelessly obscured.The few passengers huddled together for warmth, exclaiming in unison when the coach sank into a heavier rut than usual, and one old fellow, who had kept up a constant complaint ever since he had joined the coach at Truro, rose from his seat in a fury, and, fumbling with the window sash, let the window down with a crash, bringing a shower of rain in upon himself and his fellow passengers. He thrust his head out and shouted up to the driver, cursing him in a high petulant voice for a rogue and a murderer; that they would all be dead before they reached Bodmin if he persisted in driving at breakneck speed; they had no breath left in their bodies as it was, and he for one would never travel by coach again.II. 中译英艰难的国运与雄健的国民李大钊历史的道路,不会是坦平的,有时走到艰难险阻的境界。

翻译竞赛英译汉参赛原文Africa on the Silk RoadThe Dark Continent, the Birthplace of Humanity . . . Africa. All of the lands south and west of the Kingdom of Egypt have for far too long been lumped into one cultural unit by westerners, when in reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Africa is not one mysterious, impenetrable land as the legacy of the nineteenth Century European explorers suggests, it is rather an immensely varied patchwork of peoples that can be changed not only by region and country but b y nature’s way of separating people – by rivers and lakes and by mountain ranges and deserts. A river or other natural barrier may separate two groups of people who interact, but who rarely intermarry, because they perceive the people on the other side to be “different” from them.Africa played an important part in Silk Road trade from antiquity through modern times when much of the Silk Road trade was supplanted by European corporate conglomerates like the Dutch and British East India Companies who created trade monopolies to move goods around the Old World instead. But in the heyday of the Silk Road, merchants travelled to Africa to trade for rare timbers, gold, ivory, exotic animals and spices. From ports along the Mediterranean and Red Seas to those as far south asMogadishu and Kenya in the Indian Ocean, goods from all across the continent were gathered for the purposes of trade.One of Africa’s contributions to world cuisine that is still widely used today is sesame seeds. Imagine East Asian food cooked in something other than its rich sesame oil, how about the quintessential American-loved Chinese dish, General Tso’s Chicken? How ‘bout the rich, thick tahini paste enjoyed from the Levant and Middle East through South and Central Asia and the Himalayas as a flavoring for foods (hummus, halva) and stir-fries, and all of the breads topped with sesame or poppy seeds? Then think about the use of black sesame seeds from South Asian through East Asian foods and desserts. None of these cuisines would have used sesame in these ways, if it hadn’t been for the trade of sesame seeds from Africa in antiquity.Given the propensity of sesame plants to easily reseed themselves, the early African and Arab traders probably acquired seeds from native peoples who gathered wild seeds. The seeds reached Egypt, the Middle East and China by 4,000 –5,000 years ago as evidenced from archaeological investigations, tomb paintings and scrolls. Given the eager adoption of the seeds by other cultures and the small supply, the cost per pound was probably quite high and merchants likely made fortunes offthe trade.Tamarind PodsThe earliest cultivation of sesame comes from India in the Harappan period of the Indus Valley by about 3500 years ago and from then on, India began to supplant Africa as a source of the seeds in global trade. By the time of the Romans, who used the seeds along with cumin to flavor bread, the Indian and Persian Empires were the main sources of the seeds.Another ingredient still used widely today that originates in Africa is tamarind. Growing as seed pods on huge lace-leaf trees, the seeds are soaked and turned into tamarind pulp or water and used to flavor curries and chutneys in Southern and South Eastern Asia, as well as the more familiar Worcestershire and barbeque sauces in the West. Eastern Africans use Tamarind in their curries and sauces and also make a soup out of the fruits that is popular in Zimbabwe. Tamarind has been widely adopted in the New World as well as is usually blended with sugar for a sweet and sour treat wrapped in corn husk as a pulpy treat or also used as syrup to flavor sodas, sparkling waters and even ice cream.Some spices of African origin that were traded along the Silk Road havebecome extinct. One such example can be found in wild silphion which was gathered in Northern Africa and traded along the Silk Road to create one of the foundations of the wealth of Carthage and Kyrene. Cooks valued the plant because of the resin they gathered from its roots and stalk that when dried became a powder that blended the flavors of onion and garlic. It was impossible for these ancient people to cultivate, however, and a combination of overharvesting, wars and habitat loss cause the plant to become extinct by the end of the first or second centuries of the Common Era. As supplies of the resin grew harder and harder to get, it was supplanted by asafetida from Central Asia.Other spices traded along the Silk Road are used almost exclusively in African cuisines today – although their use was common until the middle of the first millennium in Europe and Asia. African pepper, Moor pepper or negro pepper is one such spice. Called kieng in the cuisines of Western Africa where it is still widely used, it has a sharp flavor that is bitter and flavorful at the same time – sort of like a combination of black pepper and nutmeg. It also adds a bit of heat to dishes for a pungent taste. Its use extends across central Africa and it is also found in Ethiopian cuisines. When smoked, as it often is in West Africa before use, this flavor deepens and becomes smoky and develops a black cardamom-like flavor. By the middle of the 16th Century, the use and trade of negro pepper in Europe,Western and Southern Asia had waned in favor of black pepper imports from India and chili peppers from the New World.Traditional Chinese ShipGrains of paradise, Melegueta pepper, or alligator pepper is another Silk Road Spice that has vanished from modern Asian and European food but is still used in Western and Northern Africa and is an important cash crop in some areas of Ethiopia. Native to Africa’s West Coast its use seems to have originated in or around modern Ghana and was shipped to Silk Road trade in Eastern Africa or to Mediterranean ports. Fashionable in the cuisines of early Renaissance Europe its use slowly waned until the 18th Century when it all but vanished from European markets and was supplanted by cardamom and other spices flowing out of Asia to the rest of the world.The trade of spices from Africa to the rest of the world was generally accomplished by a complex network of merchants working the ports and cities of the Silk Road. Each man had a defined, relatively bounded territory that he traded in to allow for lots of traders to make a good living moving goods and ideas around the world along local or regional. But occasionally, great explorers accomplished the movement of goods across several continents and cultures.Although not African, the Chinese Muslim explorer Zheng He deserves special mention as one of these great cultural diplomats and entrepreneurs. In the early 15th Century he led seven major sea-faring expeditions from China across Indonesia and several Indian Ocean ports to Africa. Surely, Chinese ships made regular visits to Silk Road ports from about the 12th Century on, but when Zheng came, he came leading huge armadas of ships that the world had never seen before and wouldn’t see again for several centuries. Zheng came in force, intending to display China’s greatness to the world and bring the best goods from the rest of the world back to China. Zheng came eventually to Africa where he left laden with spices for cooking and medicine, wood and ivory and hordes of animals. It may be hard for us who are now accustomed to the world coming on command to their desktops to imagine what a miracle it must have been for the citizens of Nanjing to see the parade of animals from Zheng’s cultural Ark. But try we must to imagine the wonder brought by the parade of giraffes, zebra and ostriches marching down Chinese streets so long ago –because then we can begin to imagine the importance of the Silk Road in shaping the world.[文档可能无法思考全面,请浏览后下载,另外祝您生活愉快,工作顺利,万事如意!]。

英语世界翻译大赛原文第一篇:英语世界翻译大赛原文第九届“郑州大学—《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛英译汉原文The Whoomper FactorBy Nathan Cobb【1】As this is being written, snow is falling in the streets of Boston in what weather forecasters like to call “record amounts.”I would guess by looking out the window that we are only a few hours from that magic moment of paralysis, as in Storm Paralyzes Hub.Perhaps we are even due for an Entire Region Engulfed or a Northeast Blanketed, but I will happily settle for mere local disablement.And the more the merrier.【1】写这个的时候,波士顿的街道正下着雪,天气预报员将称其为“创纪录的量”。

从窗外望去,我猜想,过不了几个小时,神奇的瘫痪时刻就要来临,就像《风暴瘫痪中心》里的一样。

也许我们甚至能够见识到《吞没整个区域》或者《茫茫东北》里的场景,然而仅仅部分地区的瘫痪也能使我满足。

当然越多越使人开心。

【2】Some people call them blizzards, others nor’easters.My own term is whoompers, and I freely admit looking forward to them as does a baseball fan to ually I am disappointed, however;because tonight’s storm warnings too often turn into tomorrow’s light flurries.【2】有些人称它们为暴风雪,其他人称其为东北风暴。

Passage IOnce upon a time, there was an island where all the feelings; lived: happiness, sadness, knowledge, and all of the others including Love. One day, it was announced to the feelings that the island wound sink, so all repaired their boats and left. Love wanted to persevere until the last possible moment. When the island was almost sinking, Love decided to ask for help. Richness was passing by love in a grand boat. Love said “Richness, can you take me with you?” Richness answered, “No, I can’t, there is a lot of gold and silver in my boat. There is no place here for you.” Love decided to ask Vanity who was also passing by in a beautiful vessel. “Vanity, please help me!”“ I c an’t help you, Love, you are all wet and might damage my boat,” Vanity an swered. Sadness was close by so love asked for help,” Sadness, let me go with you.” “Oh, Love, I am so sad that I need to be by myself! ”HappinessPassed by Love,too.But she wasso happy thatshe did not even hear when love called her! Suddenly, there was a voice, “come Love,I will take you.” It was an elder, Love left so blessed and overjoyed that she even forgot to ask the eIder his name, when they arrived at dry land, the elder went his own way. Love realized how much she owed the elder and asked Knowledge; “Who helped me?”“It was tim e, dear.” Knowledge answered. Time? But why didTime help me?“Knowledge smiled with deep wisdom and answered, “because only time is capable of understanding how great love is.”译文:(一)很久以前,快乐,悲伤,知识还有爱情,都住在一个小岛上,有一天,他们被告知,小岛快要沉没了,于是所有的情感都修理他们各自的小船,然后离开了:爱想坚持到最后一刻,当小岛几乎要完全沉没时,爱决定寻求帮助,财富刚好经过爱的身边,他乘坐在一艘豪华轮船上,爱说道:“财富,你能带我一起走吗?“财富回答:“不,我不能,我船上的金银财宝太多了,没有空余的地方。

OpticsManini NayarWhen I was seven, my friend Sol was hit by lightning and died. He was on a rooftop quietly playing marbles when this happened. Burnt to cinders, we were told by the neighbourhood gossips. He'd caught fire, we were assured, but never felt a thing. I only remember a frenzy of ambulances and long clean sirens cleaving the silence of that damp October night. Later, my father came to sit with me. This happens to one in several millions, he said, as if a knowledge of the bare statistics mitigated the horror. He was trying to help, I think. Or perhaps he believed I thought it would happen to me. Until now, Sol and I had shared everything; secrets, chocolates, friends, even a birthdate. We would marry at eighteen, we promised each other, and have six children, two cows and a heart-shaped tattoo with 'Eternally Yours' sketched on our behinds. But now Sol was somewhere else, and I was seven years old and under the covers in my bed counting spots before my eyes in the darkness.After that I cleared out my play-cupboard. Out went my collection of teddy bears and picture books. In its place was an emptiness, the oak panels reflecting their own woodshine. The space I made seemed almost holy, though mother thought my efforts a waste. An empty cupboard is no better than an empty cup, she said in an apocryphal aside. Mother always filled things up - cups, water jugs, vases, boxes, arms - as if colour and weight equalled a superior quality of life. Mother never understood that this was my dreamtime place. Here I could hide, slide the doors shut behind me, scrunch my eyes tight and breathe in another world. When I opened my eyes, the glow from the lone cupboard-bulb seemed to set the polished walls shimmering, and I could feel what Sol must have felt, dazzle and darkness. I was sharing this with him, as always. He would know, wherever he was, that I knew what he knew, saw what he had seen. But to mother I only said that I was tired of teddy bears and picture books. What she thought I couldn't tell, but she stirred the soup-pot vigorously.One in several millions, I said to myself many times, as if the key, the answer to it all, lay there. The phrase was heavy on my lips, stubbornly resistant to knowledge. Sometimes I said the words out of con- text to see if by deflection, some quirk of physics, the meaning would suddenly come to me. Thanks for the beans, mother, I said to her at lunch, you're one in millions. Mother looked at me oddly, pursed her lips and offered me more rice. At this club, when father served a clean ace to win the Retired-Wallahs Rotating Cup, I pointed out that he was one in a million. Oh, the serve was one in a million, father protested modestly. But he seemed pleased. Still, this wasn't what I was looking for, and in time the phrase slipped away from me, lost its magic urgency, became as bland as 'Pass the salt' or 'Is the bath water hot?' If Sol was one in a million, I was one among far less; a dozen, say. He was chosen. I was ordinary. He had been touched and transformed by forces I didn't understand. I was left cleaning out the cupboard. There was one way to bridge the chasm, to bring Solback to life, but I would wait to try it until the most magical of moments. I would wait until the moment was so right and shimmering that Sol would have to come back. This was my weapon that nobody knew of, not even mother, even though she had pursed her lips up at the beans. This was between Sol and me.The winter had almost guttered into spring when father was ill. One February morning, he sat in his chair, ashen as the cinders in the grate. Then, his fingers splayed out in front of him, his mouth working, he heaved and fell. It all happened suddenly, so cleanly, as if rehearsed and perfected for weeks. Again the sirens, the screech of wheels, the white coats in perpetual motion. Heart seizures weren't one in a million. But they deprived you just the same, darkness but no dazzle, and a long waiting.Now I knew there was no turning back. This was the moment. I had to do it without delay; there was no time to waste. While they carried father out, I rushed into the cupboard, scrunched my eyes tight, opened them in the shimmer and called out'Sol! Sol! Sol!' I wanted to keep my mind blank, like death must be, but father and Sol gusted in and out in confusing pictures. Leaves in a storm and I the calm axis. Here was father playing marbles on a roof. Here was Sol serving ace after ace. Here was father with two cows. Here was Sol hunched over the breakfast table. The pictures eddied and rushed. The more frantic they grew, the clearer my voice became, tolling like a bell: 'Sol! Sol! Sol!' The cupboard rang with voices, some mine, some echoes, some from what seemed another place - where Sol was, maybe. The cup- board seemed to groan and reverberate, as if shaken by lightning and thunder. Any minute now it would burst open and I would find myself in a green valley fed by limpid brooks and red with hibiscus. I would run through tall grass and wading into the waters, see Sol picking flowers. I would open my eyes and he'd be there,hibiscus-laden, laughing. Where have you been, he'd say, as if it were I who had burned, falling in ashes. I was filled to bursting with a certainty so strong it seemed a celebration almost. Sobbing, I opened my eyes. The bulb winked at the walls.I fell asleep, I think, because I awoke to a deeper darkness. It was late, much past my bedtime. Slowly I crawled out of the cupboard, my tongue furred, my feet heavy. My mind felt like lead. Then I heard my name. Mother was in her chair by the window, her body defined by a thin ray of moonlight. Your father Will be well, she said quietly, and he will be home soon. The shaft of light in which she sat so motionless was like the light that would have touched Sol if he'd been lucky; if he had been like one of us, one in a dozen, or less. This light fell in a benediction, caressing mother, slipping gently over my father in his hospital bed six streets away. I reached out and stroked my mother's arm. It was warm like bath water, her skin the texture of hibiscus.We stayed together for some time, my mother and I, invaded by small night sounds and the raspy whirr of crickets. Then I stood up and turned to return to my room.Mother looked at me quizzically. Are you all right, she asked. I told her I was fine, that I had some c!eaning up to do. Then I went to my cupboard and stacked it up again with teddy bears and picture books.Some years later we moved to Rourkela, a small mining town in the north east, near Jamshedpur. The summer I turned sixteen, I got lost in the thick woods there. They weren't that deep - about three miles at the most. All I had to do was cycle forall I was worth, and in minutes I'd be on the dirt road leading into town. But a stir in the leaves gave me pause.I dismounted and stood listening. Branches arched like claws overhead. The sky crawled on a white belly of clouds. Shadows fell in tessellated patterns of grey and black. There was a faint thrumming all around, as if the air were being strung and practised for an overture. And yet there was nothing, just a silence of moving shadows, a bulb winking at the walls. I remembered Sol, of whom I hadn't thought in years. And foolishly again I waited, not for answers but simply for an end to the terror the woods were building in me, chord by chord, like dissonant music. When the cacophony grew too much to bear, I remounted and pedalled furiously, banshees screaming past my ears, my feet assuming a clockwork of their own. The pathless ground threw up leaves and stones, swirls of dust rose and settled. The air was cool and steady as I hurled myself into the falling light.光学玛尼尼·纳雅尔谈瀛洲译在我七岁那年,我的朋友索尔被闪电击中死去了。