翻译6

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:360.50 KB

- 文档页数:4

六英语单词带中文翻译标题,Challenge and Triumph: Overcoming Obstacles and Achieving Success。

挑战和胜利,克服障碍,取得成功。

In life, challenges are inevitable. They come in various forms, testing our resilience, determination, and perseverance. However, it is how we confront and overcome these obstacles that defines our journey and leads us to success.生活中,挑战是不可避免的。

它们以各种形式出现,测试我们的韧性、决心和毅力。

然而,我们是如何面对并克服这些障碍,决定了我们的旅程,并引领我们走向成功。

1. Persistence (坚持)。

Persistence is key when facing challenges. It's the relentless pursuit of our goals despite setbacks thatultimately leads to triumph. When obstacles arise, it's tempting to give up, but those who persist, pushing through the difficulties, are the ones who emerge victorious.在面对挑战时,坚持不懈至关重要。

尽管遭遇挫折,但对目标的不懈追求最终导致了胜利。

当障碍出现时,放弃是很诱人的,但那些坚持不懈、克服困难的人才是最终胜利者。

2. Courage (勇气)。

Courage is essential when tackling obstacles. It's the strength to face adversity head-on, to step out of our comfort zones, and to take risks in pursuit of our dreams. Without courage, we would shy away from challenges,limiting our potential for growth and success.面对障碍时,勇气至关重要。

lesson6 ⼀个好机会 Lesson Six A Good Chance 我到鸭溪时,喜鹊没在家,我和他的妻⼦阿⽶莉亚谈了谈。

When I got to Crow Creek, Magpie was not home. I talked to his wife Amelia. “我要找喜鹊,”我说,“我给他带来了好消息。

”我指指提着的箱⼦,“我带来了他的诗歌和⼀封加利福尼亚⼤学的录取通知书,他们想让他来参加为印第安⼈举办的艺术课。

” “I need to find Magpie,” I said. “I've really got some good news for him.” I pointed to the briefcase I was carrying. “I have his poems and a letter of acceptance from a University in California where they want him to come and participate in the Fine Arts Program they have started for Indians.” “你知道他还在假释期间吗?” “Do you know that he was on parole?” “这个,不,不⼤清楚。

”我犹豫着说,“我⼀直没有和他联系,但我听说他遇到了些⿇烦。

” “Well, no, not exactly,” I said hesitantly, “I haven't kept in touch with him but I heard that he was in some kind of trouble. 她对我笑笑说:“他已经离开很久了。

你知道,他在这⼉不安全。

他的假释官随时都在监视他,所以他还是不到这⼉来为好,⽽且我们已经分开⼀段时间了,我听说他在城⾥的什么地⽅。

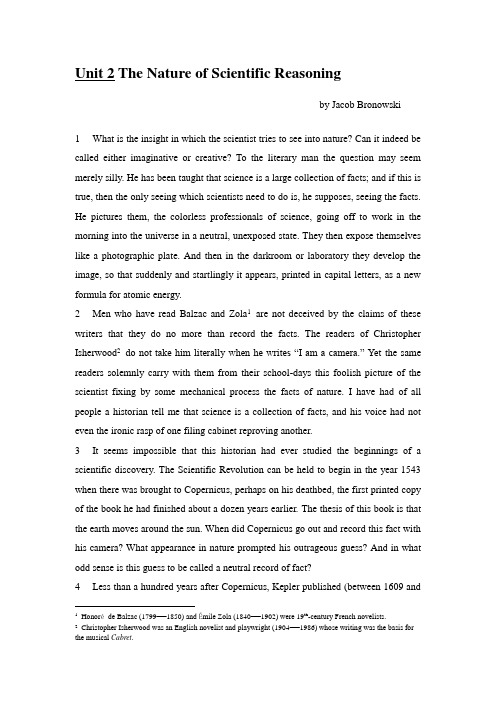

Unit 2 The Nature of Scientific Reasoningby Jacob Bronowski1 What is the insight in which the scientist tries to see into nature? Can it indeed be called either imaginative or creative? To the literary man the question may seem merely silly. He has been taught that science is a large collection of facts; and if this is true, then the only seeing which scientists need to do is, he supposes, seeing the facts. He pictures them, the colorless professionals of science, going off to work in the morning into the universe in a neutral, unexposed state. They then expose themselves like a photographic plate. And then in the darkroom or laboratory they develop the image, so that suddenly and startlingly it appears, printed in capital letters, as a new formula for atomic energy.2 Men who have read Balzac and Zola1are not deceived by the claims of these writers that they do no more than record the facts. The readers of Christopher Isherwood2do not take him literally when he writes “I am a camera.” Yet the same readers solemnly carry with them from their school-days this foolish picture of the scientist fixing by some mechanical process the facts of nature. I have had of all people a historian tell me that science is a collection of facts, and his voice had not even the ironic rasp of one filing cabinet reproving another.3 It seems impossible that this historian had ever studied the beginnings of a scientific discovery. The Scientific Revolution can be held to begin in the year 1543 when there was brought to Copernicus, perhaps on his deathbed, the first printed copy of the book he had finished about a dozen years earlier. The thesis of this book is that the earth moves around the sun. When did Copernicus go out and record this fact with his camera? What appearance in nature prompted his outrageous guess? And in what odd sense is this guess to be called a neutral record of fact?4 Less than a hundred years after Copernicus, Kepler published (between 1609 and 1Honoréde Balzac (1799—1850) and Émile Zola (1840—1902) were 19th-century French novelists.2Christopher Isherwood was an English novelist and playwright (1904—1986) whose writing was the basis for the musical Cabret.1619) the three laws which describe the paths of the planets. The work of Newton and with it most of our mechanics spring from these laws.3They have a solid, matter-of-fact sound. For example, Kepler says that if one squares the year of a planet, one gets a number which is proportional to the cube of its average distance from the sun. Does anyone think that such a law is found by taking enough readings and then squaring and cubing everything in sight? If he does, then, as a scientist, he is doomed to a wasted life; he has as little prospect of making a scientific discovery as an electronic brain has.5 It was not this way that Copernicus and Kepler thought, or that scientists think today. Copernicus found that the orbits of the planets would look simpler if they were looked at from the sun and not from the earth. But he did not in the first place find this by routine calculation. His first step was a leap of imagination—to lift himself from the earth, and put himself wildly, speculatively into the sun. “The earth conceives from the sun,” he wrote; and “the sun rules the family of stars.” We catch in his mind an image, the gesture of the virile man standing in the sun, with arms outstretched, overlooking the planets. Perhaps Copernicus took the picture from the drawings of the youth with outstretched arms which the Renaissance teachers put into their books on the proportions of the body. Perhaps he had seen Leonardo’s4drawings of his loved pupil Salai. I do not know. To me, the gesture of Copernicus, the shining youth looking outward from the sun, is still vivid in a drawing which William Blake5in 1780 based on all these: the drawing which is usually called Glad Day.6 Kepler’s mind, we know, was filled with just such fanciful analogies; and we know what they were. Kepler wanted to relate the speeds of the planets to the musical intervals. He tried to fit the five regular solids into their orbits. None of these likenesses worked, and they have been forgotten; yet they have been and they remain the stepping stones of every creative mind. Kepler felt for his laws by way of metaphors, he searched mystically for likenesses with what he knew in every strange 3Nicolaus Copernicus (1473—1543) was a Polish astronomer. Johannes Kepler (1571—1630) was a German astronomer. Isaac Newton (1642—1727) was an English physicist and mathematician.4Leonardo da Vinci (1452—1519) was an Italian artist, inventor and designer.5William Blake (1757—1827) was an English poet, artist and engraver.corner of nature. And when among these guesses he hit upon his laws, he did not think of their numbers as the balancing of a cosmic bank account, but as a revelation of the unity in all nature. To us, the analogies by which Kepler listened for the movement of the planets in the music of the spheres are farfetched. Yet are they more so than the wild leap by which Rutherford and Bohr6in our own century found a model for the atom in, of all places, the planetary system?7 No scientific theory is a collection of facts. It will not even do to call a theory true or false in the simple sense in which every fact is either so or not so. The Epicureans held that matter is made of atoms two thousand years ago and we are now tempted to say that their theory was true. But if we do so we confuse their notion of matter with our own. John Dalton7in 1808 first saw the structure of matter as we do today, and what he took from the ancients was not their theory but something richer, their image: the atom. Much of what was in Dalton’s mind was as vague as the Greek notion, and quite as mistaken. But he suddenly gave life to the new facts of chemistry and the ancient theory together, by fusing them to give what neither had: a coherent picture of how matter is linked and built up from different kinds of atoms. The act of fusion is the creative act.8 All science is the search for unity in hidden likenesses. The search may be on a grand scale, as in the modern theories which try to link the fields of gravitation and electromagnetism. But we do not need to be browbeaten by the scale of science. There are discoveries to be made by snatching a small likeness from the air too, if it is bold enough. In 1935 the Japanese physicist Hideki Yukawa8wrote a paper which can still give heart to a young scientist. He took as his starting point the known fact that waves of light can sometimes behave as if they were separate pellets. From this he reasoned that the forces which hold the nucleus of an atom together might sometimes also be6Ernest Rutherford (1871—1937) was a British physicist who became known as the father of nuclear physics. Niels Bohr (1885—1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Noble Prize in Physics in 1922.7John Dalton (1766—1844) was a British chemist and physicist who developed the atomic theory of matter and thus is considered a father of modern physical science.8Hideki Yukawa (1907—1981) was a Japanese theoretical physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1949.observed as if they were solid pellets. A schoolboy can see how thin Yukawa’s analogy is, and his teacher would be severe with it. Yet Yukawa without a blush calculated the mass of the pellet he expected to see, and waited. He was right; his meson was found, and a range of other mesons, neither the existence nor the nature of which had been suspected before. The likeness had borne fruit.9 The scientist looks for order in the appearances of nature by exploring such likenesses. For order does not display itself of itself; if it can be said to be there at all, it is not there for the mere looking. There is no way of pointing a finger or camera at it; order must be discovered and, in a deep sense, it must be created. What we see, as we see it, is mere disorder.10 This point has been put trenchantly in a fable by Karl Popper9. Suppose that someone wished to give his whole life to science. Suppose that he therefore sat down, pencil in hand, and for the next twenty, thirty, forty years recorded in notebook after notebook everything that he could observe. He may be supposed to leave out nothing: today’s humidity, the racing results, the level of cosmic radiation and the stock market prices and the look of Mars, all would be there. He would have compiled the most careful record of nature that has ever been made; and, dying in the calm certainty of a life well spent, he would of course leave his notebooks to the Royal Society. Would the Royal Society thank him for the treasure of a lifetime of observation? It would not. The Royal Society would treat his notebooks exactly as the English bishops have treated Joanna Southcott’s box.10It would refuse to open them at all, because it would know without looking that the notebooks contain only a jumble of disorderly and meaningless items.11 Science finds order and meaning in our experience, and sets about this in quite a different way. It sets about it as Newton did in the story which he himself told in his old age, and of which the schoolbooks give only a caricature. In the year 1665, when Newton was twenty-two, the plague broke out in southern England, and the 9Karl Popper (1902—1994) was an Austrian-born British philosopher who is generally regarded as one of the greatest philosophers of science of the 20th century.10Southcott was a 19th-century English farm servant who claimed to be a prophet. She left behind a box that wasto be opened in a time of national emergency in the presence of all the English bishops. In 1927, a bishop agreed to officiate; when the box was opened, it was found to contain only some odds and ends.University of Cambridge was closed. Newton therefore spent the next eighteen months at home, removed from traditional learning, at a time when he was impatient for knowledge and, in his own phrase, “I was in the prime of my age for invention.”In this eager, boyish mood, sitting one day in the garden of his windowed mother, he saw an apple fall. So far the books have the story right; we think we even know the kind of apple; tradition has it that it was a Flower of Kent. But now they miss the crux of the story. For what struck the young Newton at the sight was not the thought that the apple must be drawn to the earth by gravity; that conception was older than Newton. What struck him was the conjecture that the same force of gravity, which reaches to the top of the tree, might go on reaching out beyond the earth and its air, endlessly into space. Gravity might reach the moon: this was Newton’s new thought; and it might be gravity which holds the moon in her orbit. There and then he calculated what force from the earth (falling off as the square of the distance) would hold the moon, and compared it with the known force of gravity at tree height. The forces agreed; Newton says laconically, “I found them answer pretty nearly.” Yet they agreed only nearly: the likeness and the approximation go together, for no likeness is exact. In Newton’s science modern science is full grown.12 It grows from a comparison. It has seized a likeness between two unlike appearances; for the apple in the summer garden and the grave moon overhead are surely as unlike in their movements as two things can be. Newton traced in them two expressions of a single concept, gravitation: and the concept (and the unity) are in that sense his free creation. The progress of science is the discovery at each step of a new order which gives unity to what had long seemed unlike.Background and Culture Notes Let me tell youJacob Bronowski was an English mathematician, scientist, and essayist. Born in Poland and educated in England, in 1933 he received a Ph.D. in mathematics from Cambridge University, where he also co-edited an avant-garde literary magazine. Bronowski served as a university lecturer before entering government service during World War II; in 1945 he was an official observer of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Throughout the 1950s he was head of research for Britain's National Coal Board, and from 1964 until his death he was a resident fellow at the Salk Institute, La Jolla, California. The author of many books, among them Science and Human Values (1956; 1965), Nature and Knowledge (1969), and Magic, Science, and Civilization (1978), He is best remembered in Britain for the thirteen-part BBC television series The Ascent of Man (1973—1974).。

Scripts for the News Cited in This LectureNews item 1Japan’s most powerful storm for nearly 25 years, Typhoon Jebi finally makes landfall. (BBC)日本遭遇了25年以来的最强台风,“飞燕”登陆了。

News item 2A 16-year-old asked a stranger at a grocery store to buy him and his mother some food in exchange for carrying the man's groceries to his car. What happened next will pull at your heartstrings. (CET4)一位16岁的少年在杂货店里请求一个陌生人为他和他妈妈买一些食物,作为交换,他可以帮这位男士把货物搬到车里。

接下来发生的事情会扣动你的心弦。

News item 3Automakers and tech companies are working hard to offer the first true self-driving car, but 75% of drivers say they wouldn‘t feel safe in such a vehicle. Still, 60% of drivers would like to get some kind of self-driving feature, such as automatic braking or self-parking, the next time they buy a new car. The attitudes are published in a new AAA (Triple A) survey of 1,800 drivers. (CET4)汽车制造商以及科技公司正在努力研发推出第一辆真正的“自动汽车”,但75%的司机表示,在这种汽车里,他们不会觉得很安全。

2022年6月大学英语六级翻译真题及答案(3套)翻译1南京长江大桥是长江上首座由中国设计、采用国产材料建造的铁路、公路两用桥,上层的 4 车道公路桥长4589 米,下层的双轨道铁路桥长6772 米。

铁路桥连接原来的天津——浦口·和上海——南京两条铁路线,使火车过江从过去一个半小时缩短为现在的 2 分钟。

大桥是南北交通的重要枢纽,也是南京的著名景点之一。

南京长江大桥的建成标志着中国桥梁建设的一个飞跃,大大方便了长江两岸的物资交流和人员往来,对促进经济发展和改善人民生活起到了巨大作用。

The Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge is the first rail-road bridge across the Yantze River which was designed by China and constructed with China-made materials. The upper deck is a 4,589 metre-long four-lane road bridge, and the lower deck a 6,772 metre-long double-rail one which joins the original Tianjin-Pukou and Shanghai-Nanjing railway lines, shorten-ing the traveling time across the river from 1.5 hours to 2 minutes. The bridge is not only a significant north-south traffic hub but also a famous scenic spot in Nanjing. The bridge marks a huge progress in China's bridge construc-tion,greatly facilitating the exchanges of both goods and people on both sides of the Yangtze River and playing a major role in the development of economy and the improve-ment of people's living condition.翻译2卢沟桥位于天安门广场西南15 公里处,横跨永定河,是北京现存最古老的多拱石桥。

6的英文翻译知道6的英文翻译怎么读吗?快和小编一起来看看吧。

6的英文翻译num. six;6的英文翻译双语例句1. Developed land was to grow from 5.3% to 6.9%.已开发土地的面积将从5.3%增加到6.9%。

2. We agreed to give her ?6 a week pocket money.我们同意每周给她6英镑零花钱。

3. The Philippines has just 6,000 square kilometres of forest left.菲律宾只剩下6,000平方公里的森林了。

4. She was born in Austria on March 6, 1920.她于1920年3月6日出生在奥地利。

5. Muster needed just 72 minutes to win the one-sided match, 6-2, 6-3.穆斯特尔仅用72分钟便以6比2、6比3拿下了这场实力悬殊的比赛。

6. Grease 6 ramekin dishes of 150 ml (5-6 fl oz) capacity.将6个容量为150毫升(5至6液盎司)的烤盘涂上油。

7. Campaigning is reaching fever pitch for elections on November 6.为11月6日选举进行的竞选活动逐渐达到白热化。

8. Snow Puppies is a ski school for 3 to 6-year-olds.“雪狗之家”是一所针对3至6岁儿童的滑雪学校。

9. On 6 July a People's Revolutionary Government was constituted.7月6日,人民革命政府正式成立。

10. Martin's weak cries for help went unheard until 6.40pm yesterday.直到昨天傍晚6点40分,马丁微弱的呼救声才被人听到。

Translate the following sentences into English.1.可以说,生命的整体意义在于追求美好的生活。

(in the pursuit of)2.很难想像没有电和其他现代便利设施的日子怎么过。

(conceive of)3.他毕生致力于为他的祖国寻找合适的建筑风格,这种风格既具有现实意义,又能融入社会。

(dedicate…to)4.他还着重强调了人们玩电脑成瘾所造成的众所周知的危险。

(addicted to)5.但是,在经过这场种族暴乱之后,种族关系成为国家既要迎合又要管制的对象。

(cater for) 6. 看到窗内的情形,他不知所措,甚至大为震惊。

(perplex)7.对于自己新近的提职,彼得沉思了一会儿。

(contemplate)8.与乡村相比,大城市的一个优势在于拥有众多的影院和其他娱乐活动。

(diversion) 9.任凭想像力驰骋,我也无法预知原来有如此美好的生活等待着我。

(foresee)10.就学术成就而言,我从来没有失败过,将来一定会取得成功。

(in terms of, make it)Translate the following short passage into English.虽然对于战争的恐怖,他和他的同代人颇有同感,而且一度被称为绥靖主义的“精神之父”,然而事实上凯恩斯(Keynes)从来不抱绥靖希特勒的错觉。

他恨纳粹政权,1933年后从来没有访问过德国。

相反,为了反对希特勒,作为英国与盟国的首席谈判代表,他积极寻求伦敦和华盛顿的共同利益。

Translate the following sentences into Chinese.1. The right to pursue happiness is promised to Americans by the US Constitution, but no oneseems quite sure which way happiness runs.2. Advertising is one of our major industries, and advertising exists not to satisfy desires but tocreate them-- and to create them faster than anyone's budget can satisfy them.3. This is the cream that restores skin, these are the tablets that melt away fat around the thighs,and these are the pills of perpetual youth.4. To think of happiness as achieving superiority over others, living in a mansion made of marble, having a wardrobe with hundreds of outfits, will do to set the greedy extreme.5. Although the holy man's concept of happiness may enjoy considerable prestige in the Orient, I doubt the existence of such motionless happiness.6. Thoreau certainly didn't intend to starve, but he would put into feeding himself only as much effort as would keep him functioning for more important efforts.7. The Western weakness may be in the illusion that happiness can be bought. Perhaps the oriental weakness is in the idea that there is such a thing as perfect happiness.8. A nation is not measured by what it possesses or wants to possess, but by what it wants tobecome.9. What the early patriots might have underlined is the cardinal fact that happiness is in the pursuit itself, in the pursuit of what is engaging and life-changing, which is to say, in the idea of becoming.10. Jonathan Swift conceived of happiness as "the state of being well-deceived", or of being "afool among idiots", for Swift saw society as a land of false goals.Translate the following sentences into English.1.读完这篇文章,老师又给我们布置了短文写作的任务。