语言学分类示意图

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:136.00 KB

- 文档页数:1

语言学流派历史比较语言学历史比较语言学从前又称比较语法,通过语言亲属关系的比较研究语言的发展规律,拟测它们的共同母语。

历史比较语言学是在19世纪逐步发展和完善的,主要是印欧语系的历史比较。

19世纪之前,这种研究不是没有,但都是孤立的分散的研究,到19世纪才进入系统的研究,并使语言学走上独立发展的道路。

历史比较语言学的产生有两个不可或缺的条件,一是广泛收集世界各种语言材料,二是认识到梵语在语言比较中的地位和作用。

19世纪历史比较语言学在理论和方法上的发展大致可以分为三个阶段。

在初始阶段,丹麦的拉斯克(R·Rask)、德国的格里姆(J·Grimm)和葆扑(F·Bopp)被称为历史比较语言学的奠基者。

拉斯克在他的《古代北欧语或冰岛语起源研究》一书中第一个对基本语汇中的词进行系统的比较,找出其中的语音对应规律,由此确定语言的亲缘关系。

格里姆在拉斯克一书的启发下,在他的《日耳曼语语法》里确定了希腊语、峨特语和高地德语之间的语音对应关系,即所谓的“格里姆定律”(Grimm's Law)。

格里姆明确指出,语音对应规律是建立印欧语系和其他语系的基础。

维尔纳(K·Verner)后来补充解释清楚了“格里姆定律”难以解释的一组例外,世称“维尔纳定律”,这就使音变规律的研究日臻完善,历史比较语言学的发展也就有了扎实的理论基础。

葆朴的主要著作是《梵语、禅德语、亚美尼亚语、希腊语、拉丁语、立陶宛语、古斯拉夫语、峨特语和德语比较语法》,旨在把梵语和欧洲、亚洲的几种其他语言相比较,找出它们在形态上的共同来源。

远离欧洲的梵语在这些语言中找到了它应有的位置:它既不是拉丁语、希腊语和其他欧洲语言的母语,也不是由其他语言演变而来,它和其他语言都出于一种共同的原始语言,只不过它比其他语言保存更多的原始形式。

19世纪中期,历史比较语言学发展到第二阶段,最有代表性的人物是德国的施莱歇尔(August Schleicher),其代表作是《印度日耳曼语系语言比较语法纲要》。

绪论一、语言学的概念以语言为研究对象的科学,研究探索语言的本质、结构和发展规律。

二、有关《语言学概论》这本书是理论语言学的入门书,讲述三方面的问题:语言在社会中的地位和作用,语言的结成体系(语音、语汇和语义、语法),语言的发展变化。

学生通过本课程的学习,能比较系统地掌握语言学的基本概念、基本理论和基础知识,为提高语言理论水平、进一步学习和深入研究其他语言课程奠定必要的语言理论基础。

三、什么是理论语言学?是语言学学科的主体,它包括对个别的、具体的语言的研究和综合各种语言的研究,探索人类语言的共同规律。

四、语言学的三大发源地中国、印度、希腊-罗马五、语言学的分类1、理论语言学包括(1)、专语语言学—是以某一种具体的语言为研究对象的语言学。

它又包括从一个静止的时段角度观察和研究语言的共时语言学和从一个较长时段研究语言,研究语言动态的历时语言学;(2)、普通语言学一是以人类一般语言为研究对象,研究人类语言的性质、结构特征、发展规律,是综合众多语言的研究成果而建立起来的语言学的重要理论部分。

2、应用语言学一是将语言学的基本原理同有关学科结合起来研究问题而产生的新的学科。

六、语言学分类示意图普通语言学理论语言学历时语言学语言学专语语言学应用语言学共时语言学七、什么是文言和文言文?文言是我国“五四”以前通行的书面语,文言文是用文言写成的文章或著作。

八、什么是“小学”?是指我国传统的语文学,包括文字学、音韵学、训诂学三方面的内容。

九、古代的语言研究和今天的语言研究有哪些不同?古代的语言研究和今天的语言研究有如下几个方面的区别:第一,研究的对象不同,古代的语言主要以书面语为主要研究材料,不重视口头语言的研究,而今天语言学则十分重视口语的研究。

如制定语言规范,确立共同语的各方面标准等,都要依据口语的研究成果。

第二,研究目的不同,古代语言学研究语言,主要给政治、哲学、宗教、历史、文学方面的经典著作作注解,比如我国古代的语文学主要就是围绕阅读先秦经典著作的需要来研究文言的,而现代语言学的研究目的主要是分析语言的结构,以探索语言发展的共同规律。

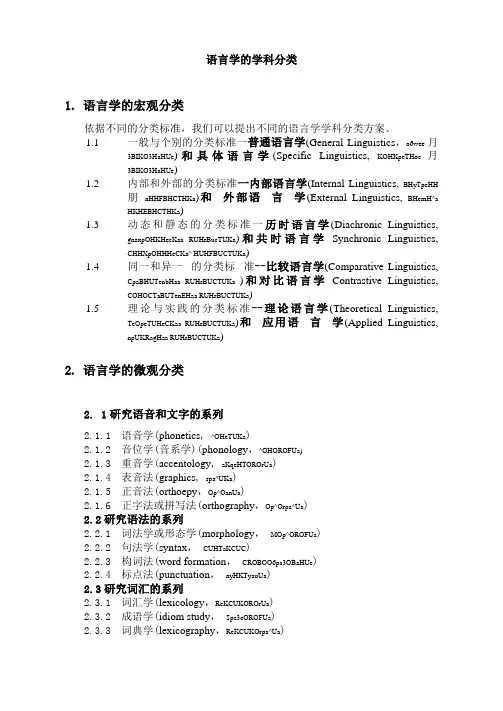

语言学的学科分类1.语言学的宏观分类依据不同的分类标准,我们可以提出不同的语言学学科分类方案。

1.1一般与个别的分类标准一普通语言学(General Linguistics,o6wee 月3BIKO3HaHUe)和具体语言学(Specific Linguistics, KOHKpeTHoe 月3BIKO3HaHUe)1.2内部和外部的分类标准一内部语言学(Internal Linguistics, BHyTpeHH朋nHHFBHCTHKa)和外部语言学(External Linguistics, BHemH^aHKHEBHCTHKa)1.3动态和静态的分类标准一历时语言学(Diachronic Linguistics,gnaxpOHKHecKaa RUHrBucTUKa)和共时语言学Synchronic Linguistics,CHHXpOHHHeCKa^ HUHFBUCTUKa)1.4同一和异一的分类标准--比较语言学(Comparative Linguistics,CpaBHUTenbHaa RUHrBUCTUKa )和对比语言学Contrastive Linguistics,COHOCTaBUTenEHaa RUHrBUCTUKa)1.5理论与实践的分类标准--理论语言学(Theoretical Linguistics,TeOpeTUHeCKaa RUHrBUCTUKa)和应用语言学(Applied Linguistics,npUKRagHaa RUHrBUCTUKa)2.语言学的微观分类2. 1研究语音和文字的系列2.1.1语音学(phonetics, ^OHeTUKa)2.1.2音位学(音系学)(phonology,^OHOROFUa)2.1.3重音学(accentology, aKqeHTOROrUa)2.1.4表音法(graphics, rpa^UKa)2.1.5正音法(orthoepy,Op^OanUa)2.1.6正字法或拼写法(orthography,Op^Orpa^Ua)2.2研究语法的系列2.2.1词法学或形态学(morphology,MOp^OROFUa)2.2.2句法学(syntax,CUHTaKCUC)2.2.3构词法(word formation,CROBOO6pa3OBaHUe)2.2.4标点法(punctuation,nyHKTyauUa)2.3研究词汇的系列2.3.1词汇学(lexicology,ReKCUKOROrUa)2.3.2成语学(idiom study,$pa3eOROFUa)2.3.3词典学(lexicography,ReKCUKOrpa^Ua)2.3.4 专名学(onomastics, OHOMacTUKa)2.4研究语言历史的系列2.4.1语言史(linguistic history, ucTOpux 只3BiKa)2.4.2古代语言(ancient language, gpeBHu宜只3BIK)2.4.3语源学(etymology,3TUMonoruG2.4.4方言学(dialectology,guaReKTonoruG2.5综合学科系列2.5.1语义学(semantics,ceMaHTUKa)2.5.2语用学(pragmatics,nparMaTUKa)2.5.3修辞学(stylistics & rhetoric,CTunucTUKa)2.5.4教学法(pedagogy & methodology,MeToguKa)2.5.5翻译(translation,nepeBog)2.5.6伴随语言学(paralinguistics,napanuHrBucTUKa)2.6边缘学科系列2.6.1社会语言学(sociolinguistics,coquonuHrBucTuKa)2.6.2符号语言学(semiotic linguistics, ceMuoTunecKaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.3心理语言学(psycholinguistics,ncuxonuHrBucruKa)2.6.4神经语言学(neurolinguistics,He宜ponuHrBucruKa)2.6.5人类语言学(anthropolinguistics,aHTpononuHrBucruKa)2.6.6哲理语言学(philosophical linguistics,^unoco^cKaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.7认知语言学(cognitive linguistics,KorHuTuBHaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.8数理语言学(mathematical linguistics,MareMaTunecKaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.9计算语言学(computational linguistics,KoMnb^TepHaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.10工程语言学(engineering linguistics,uH^eHepHaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.11地理语言学(geographical linguistics,reorpa^unecKaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.12文化语言学(cultural linguistics,KynbTypHaa RUHEBUCTUKU)2.6.13模糊语言学(fuzzy linguistics, gu^^y3Haa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.14生态语言学(ecololinguistics, SKonorunecKaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.15生物语言学(biolinguistics, 6uonorunecKaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.16病理语言学(clinical linguistics, naronuHrBucruKa)2.6.17生理语言学 (physiological linguistics, $u3uonorunecKaa nuHrBucruKa) 2.6.18民族语言学(ethnolinguistics, 3THonuHFBucruKa)2.6.19声学语言学(acoustic linguistics, aKycrunecKaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.20宇宙语言学(cosmical linguistics, KocMonuHrBucruKa)2.6.21化学语言学(chemical linguistics, xuMunecKaa nuHrBucruKa)2.6.22参量语言学 (parametric linguistics, napaMerpunecKaa nuHrBucruKa)。

Chapter 4 From word to Text (Syntax)Syntax (grammar)•Syntax refers to the study of the rules governing the way different constituents are combined to form sentences in a language, or the study of the interrelationships between elements in sentence structures.4.1 Syntactic relations•Syntactic relations can be analyzed into three kinds:–4.1.1 positional relation–4.1.2 relations of substitutability–4.1.3 relations of co-occurrence4.1.1 Positional Relation•For language to fulfill its communicative function, it must have a way to mark the grammatical roles of the various phrases that can occur in a clause.•The boy kicked the ballNP1 NP2Subject Object•Positional relation, or WORD ORDER, refers to the sequential arrangement of words in a language.•If the words in a sentence fail to occur in a fixed order required by the convention of a language, one tends to produce an utterance either ungrammatical or nonsensical at all. For example, The boy kicked the ball–*Boy the ball kicked the–*The ball kicked the boy•The teacher saw the students•The students saw the teacher•Positional relations are a manifestation of one aspect of Syntagmatic Relations observed by F. de Saussure.–They are also called Horizontal Relations or simply Chain Relations.•Word order is among the three basic ways (word order, genetic and areal classifications) to classify languages in the world.•There are 6 possible types of language:–SVO, VSO, SOV, OVS, OSV, and VOS.–English belongs to SVO type, though this does not mean that SVO is the only possible word order. 4.1.2 Relation of Substitutability•The Relation of Substitutability refers to classes or sets of words substitutable for each other grammatically in sentences with the same structure.–The ______ smiles.manboygirl•It also refers to groups of more than one word which may be jointly substitutable grammatically for a single word of a particular set.strong man–The tallest boy smiles.pretty girlyesterday.–He went there last week.the day before.•This is also called Associative Relations by Saussure, and Paradigmatic Relations by Hjemslev.•To make it more understandable, they are called Vertical Relations or Choice Relations.4.1.3 Relation of Co-occurrence•It means that words of different sets of clauses may permit, or require, the occurrence of a word of another set or class to form a sentence or a particular part of a sentence.•For instance, a nominal phrase can be preceded by a determiner and adjective(s) and followed by a verbal phrase.•Relations of co-occurrence partly belong to syntagmatic relations, partly to paradigmatic relations.4.2 Grammatical construction and its constituents4.2.1 Grammatical Construction•Any syntactic string of words ranging from sentences over phrasal structures to certain complex lexemes.–an apple–ate an apple–Mary ate an apple4.2.2 Immediate Constituents•Constituent is a part of a larger linguistic unit. Several constituents together form a construction:–the girl (NP)–ate the apple (VP)–The girl ate the apple (S)Immediate Constituent Analysis(IC Analysis)In the case of the above example, if two constituents B (the girl) and C (ate the apple) are jointed to form a hierarchically higher constituent A (here a sentence S), then B and C are said to be the immediateconstituents of A. To dismantle a grammatical construction in this way is called IC analysis.A (Sentence)B CThe boy ate the appleTwo ways: tree diagram and bracketingTree diagram:Bracketing•Bracketing is not as common in use, but it is an economic notation in representing the constituent/phrase structure of a grammatical unit.•(((The) (girl)) ((ate) ((the) (apple))))•[S[NP[Det The][N girl]][VP[V ate][NP[Det the][N apple]]]]4.2.3 Endocentric and Exocentric Constructions•Endocentric construction is one whose distribution is functionally equivalent to that of one or more of its constituents, i.e., a word or a group of words, which serves as a definable centre or head.–Usually noun phrases, verb phrases and adjective phrases belong to endocentric types because the constituent items are subordinate to the Head.•Exocentric construction refers to a group of syntactically related words where none of the words is functionally equivalent to the group as a whole, that is, there is no definable “Centre” or “Head” inside the group, usually including–the basic sentence,–the prepositional phrase,–the predicate (verb + object) construction,–the connective (be + complement) construction.•The boy smiled.(Neither constituent can substitute for the sentence structure as a whole.)•He hid behind the door.(Neither constituent can function as an adverbial.)•He kicked the ball .(Neither constituent stands for the verb-object sequence.)•John seemed angry.(After division, the connective construction no longer exists.)4.2.4 Coordination and Subordination•Endocentric constructions fall into two main types, depending on the relation between constituents: 1) Coordination•Coordination is a common syntactic pattern in English and other languages formed by grouping together two or more categories of the same type with the help of a conjunction such as and, but and or . –These two or more words or phrases or clauses have equivalent syntactic status, each of the separate constituents can stand for the original construction functionally.•Coordination of NPs:–[NP the lady] or [NP the tiger]•Coordination of VPs:–[VP go to the library] and [VP read a book ]•Coordination of PPs:–[PP down the stairs] and [PP out the door ]•Coordination of APs:–[AP quite expensive] and [AP very beautiful]•Coordination of Ss:–[S John loves Mary] and [S Mary loves John too].2) Subordination•Subordination refers to the process or result of linking linguistic units so that they have different syntactic status, one being dependent upon the other, and usually a constituent of the other.–The subordinate constituents are words which modify the head. Consequently, they can be called modifiers.•two dogsHead•(My brother) can drink (wine).Head•Swimming in the lake (is fun).Head•(The pepper was) hot beyond endurance.Head3) Subordinate clauses•Clauses can be used as subordinate constituents. There are three basic types of subordinate clauses:–complement clauses–adjunct (or adverbial) clauses–relative clauses•John believes [that the airplane was invented by an Irishman].(complement clause)•Elizabeth opened her presents [before John finished his dinner].(adverbial clause)•The woman [that I love] is moving to the south.(relative clause)4.3. Syntactic Function•The syntactic function shows the relationship between a linguistic form and other parts of the linguistic pattern in which it is used.–Names of functions are expressed in terms of subjects, objects, predicators, modifiers, complements, etc.4.3.1 Subject•In some languages, subject refers to one of the nouns in the nominative case(主格).•The typical example can be found in Latin, where subject is always in nominative case, such as pater and filius in the following examples.–pater filium amat (the father loves the son)–patrum filius amat (the son loves the father)•In English, the subject of a sentence is often said to be the agent, or the doer of the action, while the object is the person or thing acted upon by the agent.–This definition seems to work for these sentences:–Mary slapped John.■ A dog bit Bill.•but is clearly wrong in the following examples:–John was bitten by a dog.–John underwent major heart surgery.•In order to account for the case of subject in passive voice, we have two other terms “grammatical subject” (John) and “logical subject” (a dog).•Another traditional definition of the subject is “what the sentence is about” (i.e., topic). •Again, this seems to work for many sentences, such as–Bill is a very crafty fellow.•but fails in others, such as–(Jack is pretty reliable, but) Bill I don’t trust.–As for Bill, I wouldn’t take his promises very seriously.•All three sentences seem to be “about” Bill; thus we could say that Bill is the topic of all three sentences.•The above sentences make it clear that the topic is not always the grammatical subject.What characteristics do subjects have?A. Word order•Subject ordinarily precedes the verb in the statement:–Sally collects stamps.–*Collects Sally stamps.B. Pro-forms•The first and third person pronouns in English appear in a special form when the pronoun is a subject, which is not used when the pronoun occurs in other positions:–He loves me.–I love him.–We threw stones at them.–They threw stones at us.C. Agreement with the verb•In the simple present tense, an -s is added to the verb when a third person subject is singular, but the number and person of the object or any other element in the sentence have no effect at all on the form of the verb:–She angers him.–They anger him.–She angers them.D. Content questions•If the subject is replaced by a question word (who or what), the rest of the sentence remains unchanged, as in–John stole the Queen’s picture from the British Council.–Who stole the Queen’s picture from the British council?–What would John steal, if he had the chance?–What did John steal from the British Council?–Where did John steal the Queen’s picture from?E. Tag question•A tag question is used to seek confirmation of a statement. It always contains a pronoun which refers back to the subject, and never to any other element in the sentence.–John loves Mary, doesn’t he?–Mary loves John, doesn’t she?–*John loves Mary, doesn’t she?4.3.2 Predicate•Predicate refers to a major constituent of sentence structure in a binary analysis in which all obligatory constituents other than the subject were considered together.•It usually expresses actions, processes, and states that refer to the subject.–The boy is running. (process)–Peter broke the glass. (action)–Jane must be mad! (state)•The word predicator is suggested for verb or verbs included in a predicate.4.3.3 Object•Object is also a term hard to define. Since, traditionally, subject can be defined as the doer of the action, object may refer to the “receiver” or “goal” of an action, and it is further classified into Direct Object and Indirect Object.–Mother bought a doll.–Mother gave my sister a doll.IO DO•In some inflecting languages, object is marked by case labels: the accusative case (受格) for direct object, and the dative case (与格)for indirect object.–In English, “object” is recognized by tracing its relation to word order (after the verb and preposition) and by inflections (of pronouns).–Mother gave a doll to my sister.–John kicked me.•Modern linguists suggest that object refers to such an item that it can become subject in a passive transformation.–John broke the glass. The glass was broken by John.–Peter saw Jane. Jane was seen by Peter.•Although there are nominal phrases in the following, they are by no means objects because they cannot be transformed into passive voice.–He died last week.–The match lasted three hours.–He changed trains at Manchester. (*Trains were changed by him at Manchester.)4.4. Category•The term category refers to the defining properties of these general units:–Categories of the noun: number, gender, case and countability–Categories of the verb: tense, aspect, voice4.4.1 Number•Number is a grammatical category used for the analysis of word classes displaying such contrasts as singular, dual, plural, etc.–In English, number is mainly observed in nouns, and there are only two forms: singular and plural, such as dog: dogs.–Number is also reflected in the inflections of pronouns and verbs, such as He laughs: They laugh, this man: these men.•In other languages, for example, French, the manifestation of number can also be found in adjectives and articles.–le cheval royal (the royal horse)–les chevaux royaux (the royal horses)4.4.2 Gender•Such contrasts as “masculine : feminine : neuter”, “animate : inanimate”, etc. for the analysis ofword classes.–Though there is a correlation between natural gender and grammatical gender, the assignment may seemquite arbitrary in many cases.–For instance, in Latin, ignis‘fire’ is masculine, while flamma ‘flame’ is feminine. •English gender contrast can only be observed in pronouns and a small number of nouns, and, they aremainly of the natural gender type.–he: she: it–prince: princess–author: authoress•In French, gender is manifested also both in adjectives and articles.–beau cadeau (fine gift)–belle maison (fine house)–Le cadeau est beau. (The gift is good.)–La maison est belle. (The house is beautiful.)•Sometimes gender changes the lexical meaning as well, for example, in French:–le poele (the stove)–la poele (the frying pan)–le pendule (the pendulum)–la pendule (the clock)4.4.3 Case•The case category is used in the analysis of word classes to identify the syntactic relationship between words in a sentence.–In Latin grammar, cases are based on variations in the morphological forms of the word, and are given the terms “accusative”, “nominative”, “dative”, etc.–There are five cases in ancient Greek and eight in Sanskrit. Finnish has as many as fifteen formally distinct cases in nouns, each with its own syntactic function.•In English, case is a special form of the noun which frequently corresponds to a combination of preposition and noun, and it is realized in three channels:–inflection–following a preposition–word order•as manifested in–teacher : teacher’s–with : to a man–John kicked Peter : Peter kicked John4.4.4 Agreement•Agreement (or concord) may be defined as the requirement that the forms of two or more words of specific word classes that stand in specific syntactic relationship with one another shall also, be characterized by the same paradigmatically marked category (or categories).•This syntactic relationship may be anaphoric (照应), as when a pronoun agrees with its antecedent, –Whose is this pen? --Oh, it’s the one I lost.•or it may involve a relation between a head and its dependent, as when a verb agrees with its subject and object:–Each person may have one coin.•Agreement of number between nouns and verbs:–This man runs. The bird flies.–These men run. These birds fly.SentenceClausePhraseWord•the three tallest girls (nominal phrase)•has been doing(verbal phrase)•extremely difficult(adjectival phrase)•to the door (prepositional phrase)•very fast(adverbial phrase)•The best thing would be to leave early.•It’s great for a man to be free.•Having finished their task, they came to help us.•John being away, Bill had to do the work.•Filled with shame, he left the house.•All our savings gone, we started looking for jobs.•It’s no use crying over spilt milk.•Do you mind my opening the window?Sentence: (traditional approach)simpleSentence complexnon-simplecompoundSentence: (functional approach)Yes/noInterrogativeIndicative wh-DeclarativeSentenceJussiveImperativeOptativeBasic sentence types: (Bolinger)•Mother fell.(Nominal + intransitive verbal)•Mother is young.(Nominal + copula + complement)•Mother loves Dad.(Nominal + transitive verbal + nominal).•Mother fed Dad breakfast.(Nominal + transitive verbal + nominal + nominal)•There is time.(There + existential + nominal)Basic sentence types: (Quirk)•SVC Mary is kind.a nurse.•SVA Mary is here.in the house.•SV The child is laughing.•SVO Somebody caught the ball.•SVOC We have proved him wrong.a fool.•SVOA I put the plate on the table.•SVOO She gives me expensive presents.4.6 Recursiveness•Recursiveness mainly means that a phrasal constituent can be embedded within another constituent having the same category, but it has become an umbrella term such important linguistic phenomena as coordination and subordination, conjoining and embedding, hypotactic and paratactic.–All these are means to extend sentences.–How long can a sentence be?•Theoretically, there is no limit to the embedding of one relative clause into another relative clause, so long as it does not become an obstacle to successful communication.•The same holds true for nominal clauses and adverbial clauses.–I met a man who had a son whose wife sold cookies that she had baked in her kitchen that was fully equipped with electrical appliances that were new …•John’s sister•John’s sister’s husband•John’s sister’s husband’s uncle•John’s sister’s husband’s uncle’s daughter, etc.•that house in Beijing•the garden of that house in Beijing•the tree in the garden of that house in Beijing•a bird on the tree in the garden of that house in Beijing4.6.1 Conjoining 连接•Conjoining: coordination.•Conjunctions: and, but, and or.–John bought a hat and his wife bought a handbag.–Give me liberty or give me death.4.6.2 Embedding嵌入•Embedding: subordination.•Main clauses and subordinate clauses.•Three basic types of subordinate clauses:–Relative clause: I saw the man who had visited you last year.–Complement clause: I don’t know whether Professor Li needs this book.–Adverbial clause: If you listened to me, you wouldn't make mistakes.4.7. Beyond the sentence(Text and discourse)•The development of modern linguistic science has helped push the study of syntax beyond thetraditional sentence boundary.•Linguists are now exploring the syntactic relation between sentences in a paragraph or chapter or the whole text, which leads to the emergence of text linguistics and discourse analysis.4.7.1 Sentential Connection•Hypotactic 主次(subordinate clauses):–You can phone the doctor if you like. However, I very much doubt whether he is in.–We live near the sea. So we enjoy a healthy climate.•Paratactic 并联(coordinate clauses):–In Guangzhou it is hot and humid during the summer. In Beijing it is hot and dry.–He dictated the letter. She wrote it.–The door was open. He walked in.4.7.2 Cohesion衔接•Cohesion is a concept to do with discourse or text rather than with syntax. It refers to relations of meaning that exist within the text, and defines it as a text.•Discoursal / textual Cohesiveness can be realized by employing various cohesive devices:–Conjunction 连接–Ellipsis 省略–lexical collocation 词汇搭配–lexical repetition 词汇重复–Reference 指称–Substitution 替代, etc.•“Did she get there at six?”“No, (she got there) earlier (than six).”(Ellipsis)•“Shall we invite Bill?”“No. 1 can’t stand the man.”(Lexical collocation)•He couldn’t open the door. It was locked tight.(Reference)•“Why don’t you use your own recorder?”“I don't have one.”(Substitution)•I wanted to help him. Unfortunately it was too late.(Logical connection)。

语言学概论•绪论•一、语言学的概念•1、语言:是一种特殊的社会现象,是人类最重要的交际工具,是人类的思维工具。

•2、语言学:以语言为研究对象的科学,研究探索语言的本质、结构和发展规律。

•二、关于语言学课程•本课程是中文专业必修的基础理论课之一,主要内容:语言在社会中的地位和作用;语言的结成体系(语音、语汇和语义、语法、文字、修辞);语言的发展变化;语言的应用。

•学生通过本课程的学习,能比较系统地掌握语言学的基本概念、基本理论和基础知识,为提高语言理论水平、进一步学习和深入研究其他语言课程奠定必要的语言理论基础。

•三、语言学的三大发源地•中国、印度、希腊-罗马•1、中国古代的语言学•语文学:主要是为古代经典书面著作作注释,目的是使人们可以读懂古书的一门尚未独立的学科。

也是偏重从文献角度研究语言文字的学科总称,一般包括文字学、训诂学、音韵学、校勘学等。

中国由于古代文献丰富,文字比较特殊,语文学比较发达,广义的语文学也应该包括语言学,也就是语言学和文字学的总称,但现在由于国际学术分科中语言学是一大类,所以目前反而是语文学从属于语言学,成为语言学的一个分支。

•小学•2、印度的语言学成就•特点:不是重于理论,而是基于观察。

所讨论的理论基本上与文学研究与哲学争论有关。

词的性质和句子意义被经常讨论,句子与其所包含的词之间的语义关系,也是经常讨论的问题之一。

•贡献:A、区分了外显即时表达和内含永久主体。

认为语言有两种,一是具体场合说的话,一是抽象的语言原则。

B、语音学和音位学方面有突出成就。

认为语音是连接语言和话语之间的桥梁,语音描写分三部分:发音过程、语音的组成成分(元音,辅音)、语音在音位结构中的结合。

C、语法描写和分析方面有突出成就。

潘尼尼在著作中详细的描述了各种屈折变化、派生现象、组织结构和各种句法的用法。

•印度学者在词法研究方面取得了很大的成就:他们在分析词的构成时发现了¡°词根¡±、¡°后缀¡±与¡°词尾¡±三种主要造词单位。

作为心理现象的主观听觉和语音的客观声学效果之间并不总是一一对应的关系,语音声学要素的变化并非都能在听觉上得到对等的感知 音位是由一组彼此的差别没有辨义作用而音感上又相似的音素概括而成的音类 第二章 语音

语音是语言的物质外壳

语音的物质属性

语音的生理属性 肺——发音的动力源 喉头和声带——发音体 口腔、鼻腔和咽腔——共鸣腔

语音的心理属性 作为心理现象的听觉感知具有很强的选择性和概括性 语音的社会属性 语音和语言的意义联系是由社会约定俗成的 语音的民族性和地域性 音素和音标 音素 音标—国际音标 宽式音标 严式音标 元音和辅音 元音的分类 舌面元音

舌尖元音

卷舌元音

辅音的分类 按辅音的发音部位分:双唇音等十一类 按辅音的发音方法分:塞音等八类

什么是音位 音位具有辨义功能

音位是具有辨义功能的最小语音单位

音位总是属于特定的语言或方言的

音位变体 条件变体

自由变体

音高 音强 音长 音质

气流受阻与否 气流强弱与否 发音器官紧张均衡与否 声带是否振动

语

音

的

性质 音素 音

位 音位区别特征

音节

复元音 定义 类型 二合元音 前响二合元音 后响二合元音 三合元音(中响复元音)

复辅音 语流音变

韵律特征 长短音

声调 调值 调类 连续变调

轻重音

语调 句重音 长短 高低 韵

律特

征 音

位

的

组合 音节的划分 音渡 语音的社会性和音节的划分 音节的基本结构类型 音节结构的分析 同化 异化 弱化 脱落 增音。