城市规划中英文对照外文翻译文献

- 格式:doc

- 大小:59.50 KB

- 文档页数:16

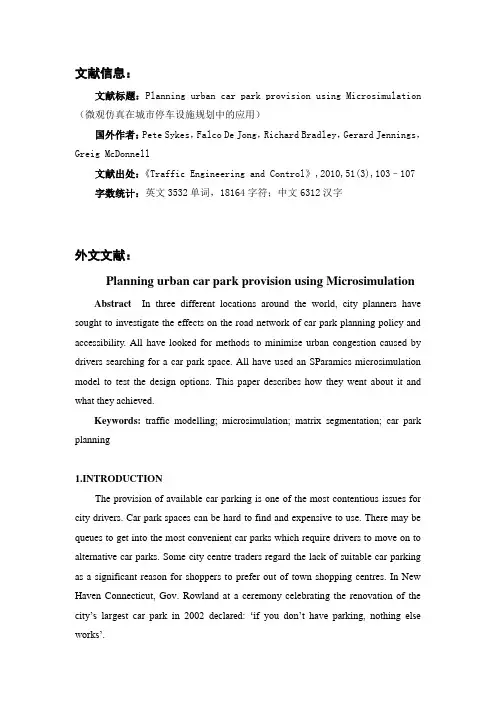

文献信息:文献标题:Planning urban car park provision using Microsimulation (微观仿真在城市停车设施规划中的应用)国外作者:Pete Sykes,Falco De Jong,Richard Bradley,Gerard Jennings,Greig McDonnell文献出处:《Traffic Engineering and Control》,2010,51(3),103–107 字数统计:英文3532单词,18164字符;中文6312汉字外文文献:Planning urban car park provision using Microsimulation Abstract In three different locations around the world, city planners have sought to investigate the effects on the road network of car park planning policy and accessibility. All have looked for methods to minimise urban congestion caused by drivers searching for a car park space. All have used an SParamics microsimulation model to test the design options. This paper describes how they went about it and what they achieved.Keywords:traffic modelling; microsimulation; matrix segmentation; car park planning1.INTRODUCTIONThe provision of available car parking is one of the most contentious issues for city drivers. Car park spaces can be hard to find and expensive to use. There may be queues to get into the most convenient car parks which require drivers to move on to alternative car parks. Some city centre traders regard the lack of suitable car parking as a significant reason for shoppers to prefer out of town shopping centres. In New Haven Connecticut, Gov. Rowland at a ceremony celebrating the renovation of the city‟s largest car park in 2002 declared: …if you don‟t have parking, nothing else works‟.Car park hunting, the circulation of drivers looking for a parking space, can be a major contribution to city centre congestion. The proportion of cars searching for a space was found to be 26% when surveyed in Manhattan in 2006, while in Brooklyn it was 45%. The situation is not new. In 1927, a similar survey in Detroit found the figures to be 19% and 34% in separate locations. This long standing problem may at last be assisted by technology. While iPhone users can now notify each other as spaces become available, traffic planners can now take advantage of recent developments in traffic modelling, which demonstrate that car park access can be included in road traffic simulation models to support the design process.Car park location in urban planning policy is largely concerned with optimising the relationship between car parks, drivers and their destinations. Charging regimes may be used to reduce localised inconvenience caused by parked cars and to favour one class of driver over another in allocating spaces. The perceived benefits include improvements to a city‟s commercial centre through better a ccessibility for the target consumer. Policies may be supply- led by actively managing spaces or demand-led by simply increasing the number of spaces. Increasingly, active management policies are used to ration spaces and encourage sustainable travel patterns.Urban planning policy considers the charging regimes for car parks. Transport planning policy complements this and considers access to the car parks. It is concerned with the relationship between car parks, the road network and congestion.Accessibility of car parks is addressed in road design guidelines. UK Department for Transport advice on parking guidance and information systems includes reports of case studies that show that there are quantifiable benefits to be derived from installing variable message signs indicating car parking space availabilty. Benefits are described as quantitative, in terms of time saved, and qualitative in terms of public image and driver safety. WebTAG guidance touches on the subject briefly in discussion of travel costs b y including …parking “costs”(which notionally include time spent searching and queuing for a space and walking to the final destination)‟.The authors‟ perception is that car park accessibility isnormally considered after the urban design is complete and car park policy has been determined. The missinglink is in the transport planning policy contribution to the initial design of urban areas with respect to car park provision and accessibility. This apparent deficiency has recently been addressed in three different locations reported here. Each has sought ways to investigate the effects on the road network of car park planning policy and accessibility. All have looked for methods to minimize urban congestion caused by drivers searching for a car park space. All have used an S-Paramics microsimulation model to test the design options.A study in Nieuwegein (The Netherlands) modelled a large expansion in travel demand and the provision of car park spaces for a major town centre redevelopment, where Saturday afternoon shopping was the critical period. It incorporated ITS within the microsimulation model to deliver information to drivers on availability of spaces and routes to car parks. Another study, in Rochdale (England), models the distribution of spaces in conjunction with major town centre development plans. The goal is to optimise the provision of car parks with respect to adjacent land use and to minimise town centre congestion by considering car park access early in the design process. The third study, in Takapuna (New Zealand), is also investigating the effect of city centre expansion. It uses bespoke software to model the car park demand and a microsimulation model to assign the demand to the network. Once again the goal is to understand the effect of car park policy and minimise city centre congestion.2.CAR PARK MODELLING IN MICROSIMULATIONTypical design option tests for a microsimulation model include changes to road layout, public transport priority schemes, optimisation of signals, or changes in demand. Each individual vehicle in the simulation will react to these changes, and the congestion they cause, as it moves to its destination. When testing the effect of car park policy decisions, the emphasis moves from examination of the effect of changes to the road network to examination of the effect of changes in the destination for that part of the trip undertaken in a car. The simulation model must now include the capability to distinguish between the driver‟s destination and the vehicle‟s parking location and make dynamic choices between these locations.2.1 ArrivalsCar parks are an entity within the microsimulation model, and are linked to zone destinations and car parks may serve more than one zone. Allocation of vehicles to car parks is undertaken by limiting car park access to specific trip purposes. The model includes car parking charges and the distances between car parks and associated zones as components of the generalised trip cost. As each vehicle type may have different cost coefficients, the modeler may differentiate between drivers who will accept a longer walk and those who will accept a higher charge.If a car park is full then vehicle drivers within the simulation wait at the entrance for a predetermined time, after which they re-assess their choice of car park and possibly proceed to another. Using an external software controller it is possible to monitor car park occupancy within the simulation and change a vehicle‟s destination before it reaches the queue. As an example of how this methodology can be used to implement a car park policy model, consider a city centre zone with a mix of retail and commercial use with several car parks available within reasonable walking distance. Drivers will have a preferred location based on their proposed length of stay and the car park charging structure.Some drivers may have a contract for permit parking. A car park may have multiple adjacent entrances, each coded with a restriction to force vehicles to accept the appropriate parking charge. The effect in the simulation is that short stay vehicles enter car parks closer to their destination or with a lower charge. The long stay vehicles enter via the entry links with the higher charges or accept a longer walk time. The modeller can test responses to car parking changes by adjusting entry charges for different car parks or by varying the level of permit parking. Land use changes may be modelled by adjusting the proportion of driver and vehicle types using a particular zone and related car parks.2.2 DeparturesThe assignment of all vehicles to an S-Paramics road network is controlled by a detailed (5 minute) time release profile. In its simplest form of use, the journey origin car park is determined by finding the minimum journey cost,which includes the walk time, or vehicles may simply be released in proportion to the size of the car park. Ifmore control is required, such as the ability to match departures to arrivals at the same car park, the release may be triggered by an external software controller linked to the simulation model which uses an algorithm to determine when to release vehicles and where they originate on the network. This may be associated with a car park occupancy monitoring system and be used to match vehicle arrivals with a subsequent departure.3.MODELLING SOLUTIONS3.1 Data collectionTravel demand matrices for the Nieuwegein model were derived from a pre-existing macroscopic model and refined with survey data. Further surveys were undertaken to determine the usage of the main car parks, the average length of stay and the residual numbers after the shops were closed. Because of the complex requirements of the Rochdale and Takapuna studies, more extensive data collection was necessary. Demand matrices for Rochdale were developed primarily from roadside interview data which identified the true destination of the journey. The interview data was used to determine the parking type (eg long/short stay, on/off street, contract), and the likely parking duration (based on journey purpose).A full parking inventory of the town centre and occupancy data provided input to a car park location model, used to link car parks to destination zones. The time to walk to each destination from each car park was initially estimated from simple geometry and later used as an important calibration parameter. Parking inventory data was essential to provide accurate capacity estimates categorised by: short or long stay, on or off-street; public or private, and charged or free. This included all car parks within, or adjacent to, the town centre. Residential parking areas adjacent to the town centre, were also included as these provided free parking, with longer walk distances, and were often used by commuters. Areas with high drop-off trips were modelled as a private parking type at their destination but could have been improved by having both the inbound and outbound legs of the drop-off trip in the matrix.The car park data also provided charging information for each car park. Whencombined with the car park interview data it was found to be possible to group charges into a single short stay and long stay charge. This simplification was appropriate in Rochdale, but it would have been possible to use a car park specific charge if the variation was more significant. Parking data in Rochdale was limited to peak car park occupancy and the model would have benefited from a comprehensive survey of vehicles entering and leaving throughout the day. In Takapuna, and Nieuwegein, arrival time, dwell time, and occupancy data was available and this was used, with the charging information, to model driver‟s choice of car park.3.2 Demand matrix segmentationMatrix segmentation enables the modeller to control departure time demands for different classes of vehicles. The degree of segmentation must be supported by the data. Similarly car parks should be grouped to a level commensurate with the detail of model input data.In Rochdale, matrices were derived for cars categorized by commuter, non-commuter and work. The interview data enabled the commuter and work matrices to be subdivided into private non residential (PNR) parking and contract parking. PNR parking supply, which is is notoriously difficult to estimate, was assumed to be unlimited in the model as the matrixes were explicity defined. For areas outside the town centre all drivers were assumed to park at their destinations.Takapuna adopted a similar approach, with demands segmented into …long stay‟ and …short stay‟ parking types.Long stay was further split into …on site‟ or …general‟ depending on access to workplace car parking. Long and short stay demands were estimated from the purpose matrices of a strategic transport model, with adjustments based on car park number plate and turn count data.3.3 Trip linkingIn order to model vehicles arriving and leaving from the same car park, trips in and out of the city centre area must be linked, with origin car parks and departure times selected based on prior arrival car parks and times. This requires more sophisticated control over the departure time and the departure location than is available from conventional OD matrix methodologies.In Nieuwegein, the study period covered the main shopping peak period on Saturday afternoon and included a warm up period to populate the car parks and initialise the ITS controller within the microsimulation model. To model the linked trips, all traffic departing from the city centre was deleted from the OD matrices. An external software controller monitored the car park occupancy in the model to determine the arrival profile and, after a suitable dwell time typically one hour, released matching vehicles on return trips.For Takapuna, before the PM simulation was run, a separate demand model was used to generate a profile of releases in the PM peak based on car park occupancy derived from the AM peak. This was to be subsequently used in the PM model run. Matrices were generated based on the profiled demands derived for each zone within Takapuna. When selecting from which particular car park the vehicle should depart, the demand model matched its outbound zone with that of a parked vehicle. The match was made based on the parking duration (long/short), and the expected departure time estimated from the arrival time distribution. If this process found a vehicle within 20% of its expected departure time, then one was added to the profile to be released. If no match was found, then the release was carried forward to the next profile period and the search repeated.The Rochdale model was also divided into AM and PM peak scenarios. The choice of car park for departure in the PM peak was modelled using the generalised cost of travel combined with an exit cost to help bias car park selection. Comparison with observed data showed the use of exit costs could successfully calibrate the model.3.4 Car park searchingAs the primary goal of all three models was to study theimpact of car parking on urban traffic congestion, the strategies for allocating vehicles to car parks within the model and subsequent car park hunting were key to the success of the studies.The Nieuwegein study was specifically designed to test the effect of a proposed car park advisory system. VMS signs were positioned on all approaches to the town centre and provided information on which car park to select. Based on the experienceof the Town Parking Manager, the ITS system was configured to make only 20% of drivers follow the advice of the parking advisory system. This left the remaining 80% to proceed to their first choice car park, and re-route from there if it was full.The Rochdale and Takapuna models focussed on accessibility more than guidance. In Rochdale, policy decisions were used to determine car park choice, which restricted the allocation of car parks to zones, eg contract parking areas were linked to work-related, rather than shopping-related zones. In Takapuna, parking was less constrained by policy and all car parks were linked to all zones with less predetermined allocation of spaces. Vehicles arriving at a car park would queue for a fixed time then move on to the next best car park based on the vehicle trip cost, walk cost, and parking cost. The Takapuna model augmented this selection process with a car park availability control and a search limit implemented through an external software controller. The search limit reflects drivers‟ willingness to circulate through numerous car parks in order to find a parking space, by setting a limit on the number to be tried before giving up, and looking for something …highly likely‟ to ha ve spaces. The availability control monitors car park occupancy any car parks that have been full for 10 minutes are removed from the list. As soon as a vehicle leaves a car park, it is reintroduced into the selection procedure.4.FIRST CHOICE CAR PARKThe first choice car park issue arose in both Rochdale and Takapuna. This occurred when the first choice car park for a vehicle was small and quickly filled. Most vehicles that selected this car park to minimise journey costs would have to re-route to their second choice. In reality many drivers make the same trip regularly and learn that this car park is usually full. They discount it as a first choice and select a larger car park with a better chance of finding a space.Two solutions were developed to address this problem.Takapuna used their car park availability controller to overwrite the driver‟s choice, to provide a proxy for the driver learning process. The second solution was to group smaller car parks, typically those with less than 50 spaces, to avoid excessively large demand being allocated to aspecific car park as first choice. Car park destination catchments and walking times were adjusted in parallel to prevent too many vehicles having the same first choice car park.A high level of matrix segmentation is in use for Rochdale to allocate car parks. This methodology offers a solution through further segmentation by driver …familiarity‟. Drivers with knowledge that the smaller car parks are full tend to avoid them and make their first choice the larger car parks.5.THE MODELS IN OPERATION5.1 NieuwegeinThe base model was calibrated for a typical Saturday afternoon.The test scenarios included planned new developmentsin the city centre. Two future year simulations were compared. In thefirst, without the advisory system, large queues formed at the most attractive car parks. With the parking advisory system, the vehicles were more equally distributed over the available parking capacity with spaces available in most car parks. This resulted in fewer vehicles searching for a parking spot and fewer queues in the city centre. This was achieved with just 20% of drivers taking heed of the parking advisory system. Future tests will extend the range of the ITS system and redesignate some roads as pedestrian areas.As the model simulated a future year scenario of 2015 and the detailed design of the town centre will probably differ from that which has been simulated, the predicted benefits were conservatively interpreted in evaluating the scheme. Despite that, the conclusion was that an investment in a parking advisory system to make the best use of the parking capacity in Nieuwegein is justifiable.5.2 RochdaleThe Rochdale model has been used to test part of a major town centre redevelopment planned for 2012. Key features include relocating the town centre bus station and council offices, removing the main town centre multi-storey car park, and redesigning key junctions on the A58 through the town centre. Further developments in the modelling process may include a similar external software controller asimplemented in Takapuna and Nieuwegein. This could include explicit car park guidance at route decision points as well as a car park space …opportunity cost‟ which would be added to the generalised cost associated with each car park before the first choice is allocated. This cost would bring the likelihood of space availability at each car park in to the destination choice although more survey data would be required to help calibrate this.5.3 TakapunaThe S-Paramics model for Takapuna is to be the operational transport assessment tool for all significant planning applications and district plan change proposals within central Takapuna. In this way, all assessments will be made under a common and consistent modeling framework as has previously been successfully achieved in two other developing areas of North Shore City. With the recent economic downturn, some landowners in the area have ceased trading or sold their holdings, while others have delayed their planning and assessment work. Takapuna has a calibrated car park model incorporated into the traffic simulation model,both of which are part of an assessment framework that is ready to be used as soon as economic growth returns.6.CONCLUSIONSCar parking strategy is crucial to reducing the problem of traffic congestion in urban centres. The Nieuwegein study has demonstrated how effective even a partial take up of a particular solution can be Tests undertaken with the Rochdale and Takapuna models show that the ability to include car parking strategies within the analytical framework can significantly influence the outcome of design solutions.Each study has identified the necessity of linking arrival and departure trips from the same car park, but developed three distinct solutions for this. The way in which simulated drivers select a car park has also varied, but has been consistently based on matrix segmentation, enabling charges and restrictions to be applied to reflect charging policies. The issue of identifying a sensible first choice car park was also addressed by each study.The three city centre studies discussed here address different aspects of car parkmodelling and have shown some innovative solutions to a common set of issues, particularly the congestion caused by drivers hunting for spaces. They have demonstrated that transport modelers can confidently use microsimulation to examine the effects of car parking strategy on urban traffic.中文译文:微观仿真在城市停车设施规划中的应用摘要为研究停车场规划和可达性对城市路网的影响,在世界范围内的三个不同城市应用微观仿真模型模拟停车设施规划。

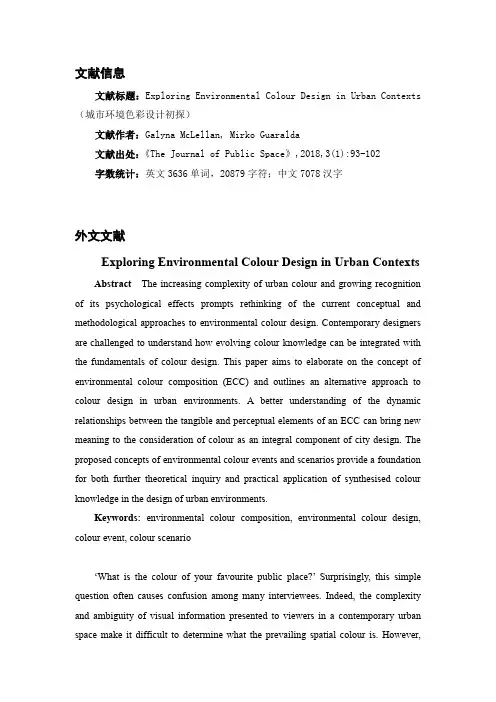

文献信息文献标题:Exploring Environmental Colour Design in Urban Contexts (城市环境色彩设计初探)文献作者:Galyna McLellan, Mirko Guaralda文献出处:《The Journal of Public Space》,2018,3(1):93-102字数统计:英文3636单词,20879字符;中文7078汉字外文文献Exploring Environmental Colour Design in Urban Contexts Abstract The increasing complexity of urban colour and growing recognition of its psychological effects prompts rethinking of the current conceptual and methodological approaches to environmental colour design. Contemporary designers are challenged to understand how evolving colour knowledge can be integrated with the fundamentals of colour design. This paper aims to elaborate on the concept of environmental colour composition (ECC) and outlines an alternative approach to colour design in urban environments. A better understanding of the dynamic relationships between the tangible and perceptual elements of an ECC can bring new meaning to the consideration of colour as an integral component of city design. The proposed concepts of environmental colour events and scenarios provide a foundation for both further theoretical inquiry and practical application of synthesised colour knowledge in the design of urban environments.Keywords:environmental colour composition, environmental colour design, colour event, colour scenario‘What is the colour of your favourite public place?’ Surprisingly, this simple question often causes confusion among many interviewees. Indeed, the complexity and ambiguity of visual information presented to viewers in a contemporary urban space make it difficult to determine what the prevailing spatial colour is. However,designers should not overlook the significant role of colour combinations in visual imagery and perceptual experiences in urban environments.The perceptual aspects of colour were first theoretically explored by Goethe. In a treatise published in 1810, Goethe reflected on the interaction of various colours placed in proximity and suggested that ‘if in this intermixture the ingredients are perfectly balanced that neither is to be distinctly recognised, the union again acquires a specific character, it appears as a quality by itself in which we no longer think of combination’ (Goethe, 1810: 277). The value of colour totality or wholeness can be expressed in terms of harmony. Harmonious and pleasant colour compositions might elicit feelings of joy and appreciation of visual experiences. In reality, when people walk along the shopping malls and streets or rest in city squares, they may not consciously notice specific artefact colours, but rather feel an emotional response to the overall atmosphere. From our observations, the expressions ‘this place makes me feel good’ or ‘it is quite a disturbing surrounding’ often substitute as assessments of the colour combinations displayed.Gothe’s colour theory has long been considered an intuitive, mostly poetic account. However, the relevance of his hypothesis to contemporary findings in the field of environmental colour psychology is undeniable. As Itten (1970: 21) states, ‘expressive colour effects – what Goethe called the ethic-aesthetic values of colour – likewise fall within the psychologist’s province’. Numerous studies conducted over the last three decades have specifically extended our understanding of the effects of colour on the psychological stances of the urban dweller. For instance, Mahnke (1998) suggests that patterns and combinations of colours in the urban environment trigger emotional responses on both conscious and unconscious levels. Obscure visual patterns and disharmonious colour schemes can cause visual disturbances, disorientation, stress or low mood. In contrast, harmonious and contextually tailored colour areas stimulate positive emotions, eliminate visual disorder and enhance social interaction (Mahnke, 1998; Porter & Mikellides, 2009). Given that colour is a sensory stimulus, it may also contribute to psychological under- or overstimulation of some individuals. Whereas overstimulating environment features exposed saturated colours,strong contrasts and flickering illumination. An understimulating setting is usually monochromatic and lacks contrast and visual accents. While sensory overstimulation may increase anxiety and depression, understimulation causes deprivation or excessive emotional responses (Franz, 2006; Mahnke, 2004). According to Day (2004), the relationships between urban forms, spaces and colour can be life sapping or life-filling.Over the last two decades, the use of innovative building materials and advanced lighting technologies has altered the complexity of colour patterns and visual experiences available to city dwellers. Porter and Mikellides (2009: 1) suggest that ‘facades can now change colour depending upon the perceptual point of view, they can thermochromatically colour-react to daytime and seasonal temperature shift, be chromatically animated by sensors, by light-projection systems or by plasma screens’.The increasing complexity of urban colour and the recognition of its psychological effects has prompted rethinking of the conceptual and methodological approaches to environmental colour design. The challenge for contemporary designers is understanding how evolving colour knowledge can be integrated with the fundamentals of colour design and how colour can be used to balance sensory stimulation and create desirable polychromatic experiences in urban contexts.Research in environmental colour psychology provides valuable information that can potentially guide design rationales but is not directly applicable to design methods (Anter & Billger, 2008). Sharpe (1981) stated that the extensive data on colour psychology must to be organised and explained before a useful design methodology can be formulated. However, few scholars pursue systematic studies in this field from a designer’s perspective.Some leading architects search for their own methods to approach polychromatic environmental design in a holistic way. For example, McLachlan (2014) provided an insightful account of the eight architectural practices known for their distinguished use of colour. Among others, she endorsed Sauerbruch and Hutton for their phenomenological approach to architectural colour and design of dynamic colour experiences. Similarly, Steven Hall received praise for his experimentation with thetransformative nature of colour and light. Mark Major (2009: 151–158) reviewed work that inspired expression of colour through light, as exemplified in the Zollverein Kokerei industrial complex in Gelsenkirghen, Germany and the Burj Al Arab tower in Dubai. He claims that ‘the seemingly infinite flexibility provided by the new generation of tools … allow[s] lighting designers, architects and artists to approach the use of colour in architecture in a progressive manner’ (Major, 2009: 154). Prominent lighting artist Yann Kersale (2009) describes his experimental installations on landmark buildings (designed by Jean Nouvel, Helmut Jahn and Patric Bochain) as articulating his vision of a ‘luminous, nocturnal architecture of colour and light’ (Porter & Mikellides, 2009). Despite individual contributions, a comprehensive colour design framework that can be utilised by mainstream architecture and urban design remains undeveloped.The methods for documenting and presenting colour design projects also require designers’ attention. Conventional architectural palettes and city colour plans are generally created under controlled lighting conditions and documented in the form of two-dimensional swatches that represent materials or pigments. In real settings, the harmonious colour combinations selected by a designer can be affected by the interplay between the visual elements presented and intervention by large-scale digital advertising. Neither architectural palettes nor city colour plans can adequately reflect dynamic changes in environmental conditions or describe the likely psychological experiences in actual urban spaces.These concerns have evolved into the concept of environmental colour composition (ECC), a holistic representation of an urban colour scheme. An ECC was initially defined by Ronchi (2002) as a synthesis of the colour of all visual elements within an urban setting, including natural elements, colours of built forms and urban elements as well as spatial and human activity patterns. This perspective aims to broaden the boundaries of an architectural palette and expand the traditional dimensions of colour in city design. However, its conceptual framework requires further clarification (specifically of the components of a contextual ECC) to provide the foundation for a shift in the colour design paradigm.In line with this need, we argue that a thorough interpretation the ECC phenomenon is a first step in developing a holistic approach to environmental colour design (ECD). A better understanding of the dynamic relationships between the tangible and perceptual elements of an ECC can bring additional meaning to the consideration of colour as an integral component of city design. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is (1) to elaborate on the conceptual definition of the ECC in the context of public urban areas and (2) to outline an alternative approach to ECD that is underpinned by the synthesis of traditional colour design methods and psychological perspectives.Environmental Colour Composition in Contemporary Urban Contexts In urban contexts, the concept of colour has traditionally been considered in terms of architectural colour palettes and city colour plans. The selection of colour in architecture is essentially concerned with the aesthetic quality of a building. Practically, an architectural palette may be used to highlight or camouflage an entire built form, to enhance tectonic facades or details and to express the personal style of a designer or brand. Instead, city colour plans have usually considered the role of an individual building within a public area and have pursued visual compatibility of architectural colours within that urban area.Several widely promoted approaches to polychromic urban architecture advocate the use of colour with reference to both location and historical and cultural traditions. For example, Giovanni Brino (2009) developed methods of colour restoration in historical city centres that were adopted by 50 Italian cities. The colour plan of Turin in Italy aimed to restore the colour of facades on a citywide scale with reference to a historical prototype that originated in the Baroque period and was recovered at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Significant aspects of the colour plan developed by the Conseil des Ediles were manifested in the uniformity of architectural colour according to a coordinated system.The focal point of Lenclos’s Geography of Colour was the use of colour palettes associated with a local identity and sense of place. In a detailed account of colourmeanings in urban environments, Lenclos (2009: 84–87) argued that colour is not an additional decoration, but rather a constituent of light that is influenced by climatic conditions, latitude, seasonal cycles and surface textures. His earlier work (1989) is associated with critical regionalism, but he has since built upon the transformative nature of contemporary colour that is sensitive to cultural, social, political and technological effects. From this new perspective, he stated: ‘I am convinced that we are now experiencing a very important period in which architectural colour, now expressed in materials and illumination rather than paint is creating a new chromatic dialectic between form, space, structure and light’ (2009: 86).Spillmann’s original palette for Kirchsteigfeld in Potsdam was inspired by the concept of ‘unity in diversity’ and aimed to consolidate urban relationships while providing ‘a colour- intense discrimination between public, semi-private and private spaces’ (Spillmann, 2009: 36). The novelty of Spillmann’s methodology has been underpinned by the integration of functional, environmental and social aspects of colour design in the contemporary built environment. He argued that ‘the most harmonious colour combination will lose its harmony if it does not correspond with specific human needs and activities, if it does not fit with the given surroundings, or if it does not sensibly interpret the building structure’ (cited in Schindler, 2004: 64).The conceptual frameworks developed by Bruno, Lenclos and Spillmann provided foundations for further exploration of colour phenomena in contemporary cities. For instance, Ronchi (2002) introduced another view of ECC that reflected the complexity and dynamics of colour images in urban settings. According to Ronchi (2002), an ECC includes the colours of natural elements, built forms and urban elements. Perception of ECC is influenced by pattern of spatial arrangements and human activities. A literature review revealed fragmented theoretical considerations that can be combined to enhance Ronchi’s (2002) definitions. Recently, Zennaro (2017) defined the factors that influence perception of environmental colour as the size and functional use of buildings and the dimensions of, and relationships between, urban elements such as streets and public squares. Further, he emphasised the importance of geographical location, history and cultural traditions. Based on thiscombined knowledge, the main elements of any ECC can be classified as shown in Figure 1.Fig. 1. Core Elements of Environmental Colour.The complexities and combinations of core ECC elements differ substantially between urban settings and depend on multiple factors. For example, certain colours presented in urban environments can be understood as measurable physical properties. Others correlate with visual experiences and are defined through the viewer’s perception. Thus, ECC has both tangible and intangible properties.In a practical sense, the classification described here can be used to assess the visual elements of an ECC within diverse historical and cultural conditions. Indeed, the original ECCs of Turin, Italy in the nineteenth century would be more unified in terms of colour compared to those in the city of Brisbane, Australia. The rapidly increasing complexity of ECCs in contemporary cities could be mainly attributed to changes in the density and volume of built forms; intervention of large-scale digital billboards and urban art installations; use of innovative colour-changing and highlyreflective materials; development of new lighting technologies and the introduction of media facades.In the Brisbane context, the media facades and laser light projections on buildings remain limited and circumstantial. In contrast, giant advertising boards frequently appear on the ground, midsections of high-rise buildings and even on the rooves of heritage buildings. In some cases, the dimensions of such boards are almost equal to or bigger than the host building itself (see Figure 2). The saturated and flickering images of a digital billboard may overpower architectural colour, create colour dissonance and affect the visual experiences of both pedestrians and vehicle commuters. When installed on historical buildings, these boards may compromise the historical and cultural value of the public space or produce undesirable symbolic associations.Fig. 2. Large digital board installations in Brisbane. These are found (a) on the roof of a historical building and (b) ground-standing digital board attached to a building used as abackground. Photographs are the authors’ own.Fig. 3. Expression of brand-related colours on buildings in Brisbane. Photographs are the authors’own.Another notable tendency in the use of colour is the expression of branding colour on facades. This means that entire commercial buildings have been painted in a brand-related colour without consideration of the potential effects of this approach on the perceived colour schemes (and thus, the appearance and aesthetics) of the surrounding area.A better understanding of the interrelated layers of colour in contemporary urban contexts may assist architects, urban designers and planners with surveying and analysing existing ECCs. This would allow development of a rationale for colour palette selection for singular infills or urban renewal proposals and for the approval of installations on existing buildings. Additionally, this knowledge may inform an alternative approach to ECD and suggest a more effective way of presenting the ECD product to clients, stakeholders and communities.Conceptualisation of Environmental Colour Events and ScenariosThe environmental colour event (ECE) hypothesis originated from Ronchi’s conception of ECC, but it celebrates the dynamic nature of colour in urban environments. This way of thinking was initially inspired by Cruz-Deiz’s (2009: 11) philosophical discourse, which claims that:Colour reveals itself as a powerful means to stimulate the perception of reality. Our conception of reality today is not that of 12th century man for whom life was a step towards eternity. On contrary, we believe in the ephemeral, with no past and no future, and where everything changes and is transformed in an instant. The perception of colour reveals such notions. It highlights space ambiguousness and ephemeral and unstable conditions, whilst underpinning myths and affections.Later in this discourse, Cruz-Deiz (2009: 56) interprets colour as an ephemeral event that takes place in space and time. This concept is based on his personal reflections and intuitive exploration. Cruz-Deiz does not elaborate on the essential properties of a colour event; however, the universality of his philosophical assumptionprovides a foundation for inferring environmental colour as a dynamic and spatiotemporal event.Building upon the Ronchi’s (2002) and Cruz-Deiz’s (2009) concepts, the ECE can be related to the ECC of an urban space within a variable timeframe. Therefore, an ECE is characterised by both static and dynamic properties. The static properties are representative of the inherent colours of the built forms and urban elements. They are associated with the functional use, aesthetic value or symbolic meaning of colour. The dynamic properties reflect changing conditions influenced by natural and coloured artificial light, running images of digital billboards, interactive art installations and human activity.Light and colour are inseparable factors in the process of environmental perception (Anter, 2000). During the day, the angle of natural light changes, which affects the appearance of perceived colours. Further, Tosca (2002) argues that contemporary cityscapes are significantly influenced by both natural light and artificial illumination, the latter of which makes it possible to visually modify the appearance of objects and space independent of viewing angles, distance and movement. Thus, Tosca (2002: 442) defines two distinct images: ‘the cityscape of daylight and that of the artificial light’. For examples of this in Brisbane, see Figure 4.Figure 4. Brisbane city: morning and night. Photographs are the authors’.Lenclos (2009: 86) draws a parallel with Tosca (2002) and suggests that:Yet another phenomenon is commonly seen in today’s cities across the world where buildings are no longer designed to function as an architectural event to be expressed during the light of day. Using a programmed choreography of coloured light, they can transform into a dynamic after-dark spectacle which can either complement or contrast with their daytime appearance. Well-known examples of this dual existence are found in Jean Nouvel’s Agbar Tower in Barcelona which, after nightfall, assumes a new and vibrant persona.Presumably, illumination as a design element of ECE allows linkage of day and night-time visual experiences. Dynamic lighting setups can be created to smooth the transition between sunlight and nocturnal ambience by balancing visual stimulation within changing conditions. Purpose-selected coloured lighting may emphasise the symbolic meaning of local colour and enhance the cultural identity of an urban area.The idea of continuity in visual experiences relates to our original interpretation of environmental colour scenarios. Following the definition of ECE, an environmentalcolour scenario (ECS) is a coordinated set of recurring ECEs linked by a thread of identifiable colour leitmotifs. Hypothetically, a designed colour scenario contributes to harmonious and balanced relationships between the static and dynamic colours of an urban setting. Additionally, the variations of ECEs within a designed scenario enrich visual experiences. Inference of ECS as a holistic design approach is ontologically rooted in the ‘primary design’ theory invented by Castelli. The theory shifts focus in colour design towards the non-material—or so-called ‘soft’—aspects, which generally remain secondary in design rationales and are often underestimated by architects (Thackara, 1985: 28). These soft aspects include colour, light, microclimate, decoration and even odour and background sound. Castelli (cited in Mitchell, 1993) claims that his design approach intentionally eliminates forms and considers colour, light, texture and sound as means of design. He also emphasised the limitations of the traditional two-dimensional presentation of architectural designs. According to Castelli (cited in Mitchell, 1993: 88), two-dimensional architectural drawings ‘tend to stress the objective properties of a product and neglect the subjective aspects, including sensual qualities’.Mitchell (1993) positioned ‘primary design’ within the contextual design trend that is considered a catalyst for the user’s perceived aesthetic experience. In keeping with contextual design traditions, an ECS is primarily concerned with experiences of colour and light in urban environments. This design approach aims to create a context in which an ECE will be perceived. However, a question that arises is whether the proposed concepts of ECS may inform applicable design methods.The description of an ECD methodology is outside the scope of this paper. Rather, we hope to initiate debate on this important topic. Ronchi (2002) defines ECD as ‘a holistic approach to the design of environmental colour composition on different spatial scales, which involves a parallel analysis of architectural, semiotic, illumination-related data as well as human-environment interaction’. This definition underlines the fundamental procedural differences between ECD and the more traditional application of colour in form design.From our perspective, as a tangible element of an ECE, an environmental colourpalette can be created using the fundamental principles of colour harmonies and contrasts.Environmental colour and material palettes can be documented and matched to the NCS colour order system in a conventional way. The initial environmental colour palette can be merged with a lighting design to create desirable visual experiences bounded by an ECS. ECEs can only be understood through perception and emotions. Psychological responses to environmental colour are subjective and difficult to assess. However, an augmented reality simulation may allow prospective users to virtually experience a singular ECE or a whole ECS and then describe their emotions using appropriate psychometric charts. To achieve a realistic presentation, the augmented simulation should integrate measurable parameters and perceived characteristics of an ECS. To make this process more user-centred, the initial design objectives can be modified based on the users’ responses. While the process described may sound complicated, it could be simplified by a thorough design application program. We believe that many practicing architects and urban designers would agree that there is a need for an application to merge theoretical and multidisciplinary colour knowledge in a meaningful way.In conclusion, a better understanding of the complexity and psychological effects of ECCs in contemporary urban settings can guide a more informed and user-responsive approach to ECD. The proposed concepts of ECE and ECS provide a foundation for further theoretical inquiry and the development of an applicable design methodology that could be used by practicing architects, urban designers and planners. The exploration of ECS in urban contexts reveals opportunities for a holistic approach to ECD based on an appreciation of both colour theories and designs for positive visual experiences.中文译文城市环境色彩设计初探摘要城市色彩的日益复杂和人们对其心理效应的日益认识,促使人们对当前环境色彩设计的概念和方法进行了重新思考。

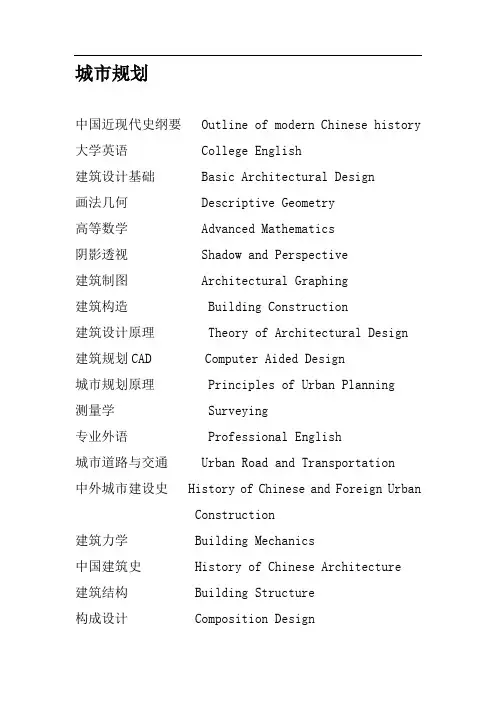

城市规划中国近现代史纲要 Outline of modern Chinese history 大学英语 College English建筑设计基础 Basic Architectural Design画法几何 Descriptive Geometry高等数学 Advanced Mathematics阴影透视 Shadow and Perspective建筑制图 Architectural Graphing建筑构造 Building Construction建筑设计原理 Theory of Architectural Design 建筑规划CAD Computer Aided Design城市规划原理 Principles of Urban Planning测量学 Surveying专业外语 Professional English城市道路与交通 Urban Road and Transportation中外城市建设史 History of Chinese and Foreign UrbanConstruction建筑力学 Building Mechanics中国建筑史 History of Chinese Architecture建筑结构 Building Structure构成设计 Composition Design外国建筑史 History of Foreign Architecture建筑设计 Architectural Design城市规划设计 Urban Planning and Design城市设计概论 Introduction to Urban Design区域发展战略规划概Introduction to Strategic Planning ofRegional Development城市规划管理与法规 Planning Law and Urban PlanningAdministration控制性详细规划概论 Introduction to Regulatory Plan城市历史文化遗产保护Conservation Policies andPlanning of City Historic Sites城市市政工程规划 Municipal Engineering Planning土地利用规划学 Land use Planning工程地质 Engineering Geology城市经济学 Urban Economics城市规划系统工程学 Urban Systems Engineering环境心理学 Environmental Psychology社会综合实践调研 Methods of Social Research中国古典园林 Classical Chinese Garden乡村规划概论 Introduction to Rural Planning房地产概论 Introduction to Real Estate地理信息系统 Geographic Information Systems西方现代园林 Western Modern Garden城市绿地规划设计原理 Planning of Urban Green Space 中国传统民居 Chinese Traditional Dwelling 城市社会学 Urban Sociology场地设计 Site Planning现代建筑思潮 Modern Architecture Movements 城市发展政策概论 Introduction to Urban DevelopmentPolicy建筑学画法几何 Descriptive Geometry阴影透视 Shadow and Perspective建筑设计基础 Basic Architectural Design建筑设计原理 Theory of Architectural Design 建筑学概论 Introduction to Architecture建筑力学 Building Mechanics建筑材料 Building Material建筑构造I Building Construction I测量学 Surveying构成设计 Composition Design建筑设计 Architectural Design建筑结构 Building Structure中国建筑史 History of Chinese Architecture外国建筑史 History of Foreign Architecture工业建筑设计原理 Principles of industrial buildingdesign建筑物理 Building Physics专业外语 Professional English建筑学CAD Computer Aided Design城市规划原理 Principles of Urban Planning结构体系与选型 Structural Lectotype建筑设备 Building equipment高层建筑设计原理 Principles of High-rise BuildingDesign大型公共建筑设计 Large Public buildings Design建筑心理学 Architectural Psychology施工概论 Construction Overview中国传统民居 Chinese Traditional Dwelling智能建筑概论 Introduction to IntelligentBuildings现代建筑思潮 Modern Architecture Movements城市绿地规划设计原理 Planning of Urban Green Space 中国古典园林 Classical Chinese Garden景观设计 Landscape Design园林植物学 landscape plant西方现代园林 Western Modern Garden生态建筑 Eco-Building城市设计概论 Introduction to Urban Design区域经济与规划 Regional Economic and Planning城市历史与文化遗产保护Conservation Policies andPlanning of City Historic Sites 房地产开发 Real Estate Development城市道路与交通 Urban Road and Transportation中外城建史 History of Chinese and Foreign UrbanConstruction规划信息系统Planning Information Systems。

城市与建筑专业英语期末翻译作业学号:090870244姓名:张奎班级:城规091班老师:杜德静Chapter eight : Urban GovernanceFurther Reading (1)Impact of Globalization on Urban Governance在过去的二十年里,许多领域出现了重组过程。

世界各地的城市已经在经济、技术、政治、文化和空间上有了重大的变化。

经济变化已经形成了一个新的全球化经济,同时粗放生产也向灵活的专业化生产转变。

国际贸易和投资也有大幅度提升。

世界重组经济刺激了向新的全球经济过渡。

因此,金融对生产的优势地位一直在增加的同时,更突出强调知识、创新和经济竞争。

另一方面,信息技术已经在城市地区改变了经济、社会和制度结构。

社会和文化变化的发生,导致社会如隔离和分裂等重大变化。

向全球化经济的过渡导致了国家经济失去对自身金融市场的控制。

制度的转变导致减少了政府在经济和社会中的积极作用。

决策分布在广泛的组织中,而不能仅局限于当地政府。

因此,政府间的关系也进行了重组。

自80年代以来,研究了在全球化政策治理关系上的影响。

虽然没有在治理的定义上达成共识,那确实显示出正式的政府结构和现代机构的角色转变,以及在公共,私人,自愿和家庭群体之间的责仸分配的变化。

增加分散在城市舞台上的责仸,在现有的国家和地方各级机构的政策制定过程中重点已转移到新机构的关系和不同的成分上。

这种分裂的影响也反映在经济和空间规划上。

一个新的政治形式,已成为一个国家重点调整的对象。

以网络的形式,治理跨越了大陆,国家,区域和地方政府之间的关系。

经济和体制因素的相互作用决定着城市和地区的多变性政府结构,而这将通过过政治,文化和其他内容的力量表现出来在这个过程中,城市収展和城市政策之间的关系变得更加复杂。

然而到目前为止,一个满意的城市治理模式,可以充分代表所有案件尚未开収。

有很多不同的方法来定义“治理”。

在很多学术领域这个词有其理论根基,其中包括制度经济学、国际关系、収展研究,政治科学和公共管理。

Journal of Planning Education and Research,2000(20): 133Planning for Metropolitan SustainabilityStephen M. WheelerThe University of CaliforniaAbstract: This article establishes a framework for thinking about sustainable development in the metropolitan context by investigating the origins of the sustainability concept and its meanings when applied to urban development, surveying historical approaches to planning the urban region, and analyzing ways in which a context can be created for regional sustainability planning. Sustainability is seen as requiring a holistic, long-term planning approach, as well as certain general policy directions such as compact urban form, reductions in automobile use, protection of ecosystems, and improved equity. Based on the experience of three sample regions, the article suggests a long-term strategic approach in which vision statements ,oalition building, institutional development, intergovernmental incentive frameworks, indicators, public involvement, and social learning help create a regional context in which sustainable development is increasingly possible.Key words:Sustainable development;Metropolitan Planning;Ecological protection Introduction: Many aspects of sustainable development are best addressed at the metropolitan regional scale. Subjects benefiting particularly from regional coordination include land use, transportation, air quality, water quality, ecosystem protection, affordable housing provision, and social equity. The problem is that this is often the most difficult level at which to find the political will and institutional capacity to bring about change. These difficulties have been particularly great in North America, where regional planning structures have been weak and incentives to think in terms of the long-term sustainability of metropolitan regions are often lacking. Nevertheless, a number of metropolitan sustainability-related initiatives are under way, and more are likely to appear in the future. The question is how planners, politicians, and activists can best develop these or help them succeed.The main body:This article will investigate the origins of the sustainability concept and its meanings when applied to urban development, briefly survey historical approaches to planning the urban region, and analyze some of conditions through which improved metropolitan sustainability planning might come about. The greatest emphasis here is on how a contextcan be created in which metropolitan sustainability planning can occur, rather than on specific techniques or policy directions. That is because (1) many general directions for sustainability planning are already well known, though specific tactics can be argued; (2) existing metropolitan sustainability initiatives in North America are quite preliminary and provide few grounds for evaluation; and (3) the most pressing question for many observers is how more substantial efforts might come about. The following discussion is based on review of the literature related to both regional planning and sustainable development and uses as examples three North American metropolitan areas—Portland, Toronto, and the San Francisco Bay Area—known for a variety of progressive regional planning initiatives that in one way or another can be seen as promoting sustainability.1Sustainability in the Metropolitan ContextAlthough it has roots in the late nineteenth-century “sustained yield” forestry practices originating in Germany, the word sustainable appears to have been first used in reference to human development patterns in 1972 in the best-selling study of global resource use. After modeling the catastrophic collapse of global systems midway through the twenty-first century under then-current population and resource use trends, the authors stated their belief that “it is possible to alter these growth trends and to establish a condition of ecological and economic stability that is sustainable far into the future”. A number of other events in the early 1970s also propelled reconsideration of long-term development trends, most notably the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm in 1972 and the 1973 energy crisis. The constituency that took the lead in developing early works on sustainability consisted of internationally oriented environmentalists. Ethicists were also involved in developing the sustainability concept during the mid-1970s, motivated by social justice concerns. A 1974 conference of the World Council of Churches issued a call for a “sustainable society,” and the earliest book specifically focused on creation of a sustainable society was published two years later by a theologian who attended that conference. Meanwhile,environmentally oriented economists formed a third important constituency. Writers such as Herman Daly and Kenneth Boulding critiqued modernist notions of “growth” and “progress” and proposed the radical idea that long-term human and ecological well-being might be better served by a steady-state economy. The need to reconcile economic, environmental, and social justice needs was to become an enduring theme of sustainable development discussions.In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the sustainable development concept entered themainstream internationally with the publication of the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. The tide of international literature on the subject grew rapidly at this time. Unfortunately, no perfect definition of sustainable development emerged. Although the Brundtland Report produced the most widely used formulation—development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”—this version has many problems. For one thing, it is anthropocentric; for another, it introduces the highly subjective concept of needs. Other definitions are equally problematic. Arising out of landscape ecology, the notion of “carrying capacity” has often been emphasized. But although this approach has important educational value, the human carrying capacity of both regional landscapes and the planet as a whole is very difficult to determine, given the mobility of human cultures and their ability to substitute for scarce resources. A third main definitional approach relies on economic concepts of “natural capital.” According to British economist David Pearce, sustainable development “is based on the requirement that the natural capital stock should not decrease over time.” However, attempts to measure natural capital (let alone social capital) quickly descend into a methodological quagmire and require a high degree of faith in the ability of economics to value noneconomic entities.The definitional strategy suggested here is to define sustainable development simply as “development that improves the long-term health of human and ecological systems.” This approach emphasizes the long-term perspective of sustainability planning but avoids fruitless debates over carrying capacity, needs, natural capital, or sustainable end states. In theory, an evolving consensus on healthy directions can be agreed on through participatory and communicative planning processes, and progress can be measured by means of various performance indicators.Until the early 1990s, few sustainability advocates focused on cities or patterns of urban development. However, during the 1990s, “sustainable city” programs began to appear in many parts of the world—some resulting from grassroots activism, some based on municipal initiative, some supported by national governments, and some facilitated by multilateral entities such as the European Community, the World Bank, and UN agencies. The Earth Summit’s Agenda 21 document became the basis for Local Agenda 21 planning in Europe.Sustainable development is widely seen as having a number of implications for the design and planning of urban regions. At the metropolitan level, some policy directions appear particularly important, given development trends of recent decades. In particular, steps to halt suburban sprawl are crucial, as is the need to end the growth in per capitaautomobile use. Affordable housing is a quiet crisis in many regions. Underlying all these problem areas, of course, are the questions of whether economic incentives can be changed to promote sustainability within the region and whether urban populations can be stabilized in the long run.A number of sustainability proposals have been developed for particular cities and regions by both local governments and nongovernmental organizations (e.g., Sustainable Cambridge Coalition 1992; Sustainable Seattle Coalition 1995; City of San Francisco 1997). As of yet, most of these plans have seen few systematic attempts at implementation. San Francisco’s plan, for example, was approved to substantial public attention in 1997 and resulted in the creation of a new Department of the Environment, but then languished as this department received little funding and environmental matters were low on the new mayor’s list of priorities.2 Historical Approaches to Metropolitan PlanningA brief review of the historical evolution of metropolitan planning can help set the context for a consideration of how sustainability-related regional planning might come about. Modern metropolitan planning is often seen as beginning in the nineteenth century, when the rapid growth, overcrowding, and service demands of industrial cities led to the need for regionwide governmental structures. One response in Britain was to create institutions such as London’s Metropolitan Board of Works, organized in 1855 to coordinate police, fire, sewer, and public health services across the Greater London area. This agency later evolved into the London County Council, which played a very active role in providing housing within the metropolitan area during the early twentieth century. Rather than creating such agencies, nineteenth- century U.S. cities (for the most part) simply annexed the land around them and extended municipal authority over the larger region. However, single-purpose regional districts were eventually set up to handle sewer, water, and park needs, such as Boston’s Metropolitan Sewerage Commission, organized in 1889.The late nineteenth-century industrial city also spawned visionary regional planning philosophies that can be seen as foreshadowing current approaches to sustainability planning. In the early twentieth century, the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA) continued the normative, metropolitan- scale approach of Geddes and Howard in the U.S. context, adopting a holistic approach to the metropolitan region that mirrors much current sustainability thinking. Lewis Mumford, for example, wrote in 1919 that thehousing problem, the industries problem, the transportation problem, and the land problem cannot be solved one at a time by isolated experts, thinking and acting in a civic vacuum.Metropolitan planning initiatives flowered in Britain and continental Europe in the years following World War II. The need for postwar reconstruction combined with social democratic politics in many areas to lead to dramatic government action in reshaping the metropolis. Perhaps most ambitious was the British government’s 1944 Greater London Plan, with its greenbelt and new to wns, based on Patrick Abercrombie’s designs. “Finger plans” channeling development along transit lines were later adopted in Copenhagen and Stockholm and represented a different but related approach to metropolitan spatial planning. Such plans represent attempts by central governments to actively shape the spatial form of the metropolitan region, to save open space and limit growth, and to coordinate land development with public transportation.The 1980s saw a decline of metropolitan planning internationally,usually in response to more conservative national politics opposed to planning in favor of market mechanisms and local government control. Regional governments were abolished in London, Barcelona, and Copenhagen and weakened in many other regions. The 1990s witnessed a revival of interest in metropolitan regional planning in North America and the appearance of a substantial amount of academic literature on the subject, although with relatively little actual change in regional institutions or policies, except in Portland. The rising interest in growth management has fueled some recent attempts at regionalism, as has rising inequality between suburbs and central cities. The 1991 federal Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act also helped catalyze efforts for more progressive regional transportation planning. Many useful tools for coordinating metropolitan land use and transportation planning have been developed in recent years, including Urban Growth Boundaries, transfer-of-development rights schemes, and more sophisticated understandings of how to design infill development. But gaining the political will to implement such measures remains difficult.A number of dilemmas now confront any metropolitan effort designed to promote sustainability. In particular, the increasing jurisdictional fragmentation of urban areas undermines the ability to think regionally. Regional initiatives are often caught in a squeeze between local governments jealously guarding their turf and higher level governments that are often unable or unwilling to support fledgling attempts at metropolitan coordination.3 ConclusionsSince so many current problems require solutions at the metropolitan scale, the intent of this article has been to lay out a framework for applying the concept of sustainable development to the urban region. Following from the nature of the sustainability concept, such planning should incorporate a long-term perspective, a holistic and interdisciplinary approach, and a balance of environmental, economic, and social objectives. Since there is a reasonable degree of consensus on general directions of metropolitan sustainability planning— compact and efficient urban form, reductions in automobile use, protection of natural ecosystems, improved regional equity, and so forth—the most pressing question becomes how to make progress toward these goals in the face of structural forces supporting unsustainable development.The experience of the sample regions sheds light on mechanisms through which metropolitan sustainability planning may emerge. Long-range vision statements or sustainabilityoriented regional plans have been developed in all three locations, at minimum promoting public debate. All three likewise have benefited from a history of citizen activism, although the size and fragmentation of the Bay Area and Toronto work against development of effective nongovernmental coalitions at the regional level. Sustainability-related planning in Portland benefits from the presence of a regional institution with significant power and from a highly developed intergovernmental incentive framework. These factors give this region enormous advantages. None of the three metropolitan areas has effectively linked a sustainability indicator framework to regional policy making, although specific performance standards (such as for air and water quality) have proven useful. Public involvement shows itself to be a double-edged sword, historically helping to create an effective Oregon planning style but also frequently blocking change of any sort in all three regions. Although communicative planning and consensus building have been an integral part of Portland’s success, it appears to be relatively difficult to bring these processes about, and such efforts are easily defeated by entrenched power interests or fragmented institutional structures. The Bay Area’s long history of failed attempts at coordinated metropolitan planning supports this point, as does the recent failure of the Atlanta Vision process. Meanwhile, Toronto’s example shows the limitations of top-down planning (from the provincial level) without local buy-in. A long history of public education and social learning around metropolitan issues appears to have borne some fruit in Portland when continued over three decades. These educational processes are less developed in the other two areas.The main hope for improved metropolitan sustainability planning, then, appears to lie in a strategic, long-term approach combining the following: continued development of visions, plans, indicators, and linked policy frameworks; development of more effective regional political coalitions supporting sustainability planning, facilitated in turn by planners and politicians; creation of stronger regional institutions and, if possible, limits to the size and jurisdictional fragmentation of metropolitan regions; intergovernmental incentive frameworks aimed at promoting sustainability, with strong state or provincial support for regional and local action; and participatory planning, consensus building, and long-term processes of public education and social learning.If, as Putnam (1998, vii) maintains, social capital is declining in general within American society, then a concerted effort will be needed to promote it within the metropolitan region to support sustainability planning. Possible strategies for planners include incorporating voluntary and nonprofit organizations and private firms as participants in metropolitan problem-solving processes, providing support for community development corporations, and nurturing democratic structures at neighborhood levels (Warren, Rosentraub, and Weschler 1992, 399). The structure of power within the region will need to be addressed as well, to reduce the ability of entrenched interests to prevent action on sustainability-related issues. Political leadership, of course, is essential on many fronts. Such a long-term, many-pronged effort appears necessary to help metropolitan regions evolve to the point where sustainability planning can in fact succeed.References :[1] Barlow, I. M. 1991. Metropolitan government. New York: Routledge.[2] Keating, W. Dennis, and Norman Krumholz. 1991. Downtown plans of the 1980s. Journal of the American Planning Association 57(2): 136-52.[3] Mitlin, Diana. 1992. Sustainable development: A guide to the literature. Environment and Urbanization 4 (1): 111-24.[4] Pearce, David. 1990. Sustainable development: Economics and environment in the Third World. London: Edward Elgar.[5] Putnam, Robert D. 1993. Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.[6] Rusk, David. 1993. Cities without suburbs. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.[7] Susman, Carl, ed. 1976. Planning the fourth migration: The neglected vision of the Regional Planning Association of America. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.[8] Urban Ecology. 1996. Blueprint for a sustainable Bay Area. Oakland, CA: Author.- 7 -Journal of Planning Education and Research,2000(20): 133都市规划的可持续发展斯蒂芬·惠勒加州大学摘要本文建立了这样的框架,通过调查在城市发展中应用可持续性概念及其意义的起源,来考虑可持续发展在大城市中的情况。

2 THEORY OF URBAN PLANNING2.1 What is a City?Most of our housing and city planning has been handicapped because those who have undertaken the work have had no clear notion of the social functions of the city. They sought to derive these functions from a cursory1survey of the activities and interests of the contemporary urban scene. And they did not, apparently, suspect that there might be gross deficiencies, misdirected efforts, mistaken expenditures here that would not be set straight by merely building sanitary tenements or straightening out and widening irregular street..大多数住房和城市规划的不完满是因为我们已经开展的工作没有清楚的城市功能社会化的概念。

他们试图从当代都市景象的活动与利益中的一个粗略的调查来获得这些功能。

显然他们没有怀疑这可能有严重的不足,误导努力的方向,在这错误的支出,将不会仅仅直接采用建设卫生的住宅或者整顿和拓宽不规则的道路。

The city as a purely physical fact has been subject to numerous investigations. But what is the city as a social institution? I would like sum up the sociological concept of the city in the following terms:城市作为一个纯粹的物理事实一直受到众多调查。

CHAPTER ONE: EVOLUTION AND TRENDSARTICLE: The Evolution of Modern Urban PlanningIt’s very difficult to give a definition to modern urban planning, from origin to today, modern urban planning is more like an evolving and changing process, and it will continue evolving and changing. Originally, modern urban planning was emerged to resolve the problems brought by Industrial Revolution; it was physical and technical with focus on land-use. Then with the economic, social, political and technical development for over one hundred years, today’s city is a complex system which contains many elements that are related to each other. And urban planning is not only required to concern with the build environment, but also relate more to economic, social and political conditions.这是非常困难的给予定义,以现代城市规划,从起源到今天,现代城市规划更像是一个不断发展和变化的过程,它会继续发展和变化。