Sovereignty of law剑桥大学法律法学Cambridge University Press 2-精选.doc

- 格式:doc

- 大小:25.50 KB

- 文档页数:1

法学类外文核心期刊1 Harvard law review 哈佛法学评论0017-811X2 The Yale law journal 耶鲁法学杂志0044-00943 Columbia law review 哥伦比亚法律评论0010-19584 Michigan law review 密歇根法律评论0026-22345 The University of Chicago law review 芝加哥大学法律评论6 Stanford law review 斯坦福法律评论0038-97657 University of Pennsylvania law review 宾夕法尼亚大学法律评论0041-99078 Virginia law review 弗吉尼亚法律评论9 The Georgetown law journal 乔治敦法律评论10 California law review 加利福尼亚法律评论0008-122111 Cornell law review 康奈尔法律评论0010-884712 The Journal of legal studies 法律研究杂志13 Texas law review 德克萨斯法律评论0040-441114 New York University law review(1950) 纽约大学法律评论0028-788115 UCLA law review 洛杉矶加州大学法律评论16 Criminology 犯罪学0011-138417 Law and human behavior 法律和人类行为0147-730718 Vanderbilt law review 范德比尔特法律评论0042-253319 The Journal of law &economics 法学与经济学杂志20 The American journal of international law 美国国际法杂志0002-930021 The Journal of taxation 税务杂志22 Northwestern University of law review 西北大学法律评论0029-357123 Southern California law review 南加利福尼亚法律评论24 Duke law journal 杜克法律杂志25 Boston University law review 波士顿大学法律评论26 American Journal of Law & Medicine 美国法律与医学杂志 0098-8588 27 Minnesota law review明尼苏达法律评论 0026-553528Journal of criminal law and criminology(Baltimore,MD:1975) 刑法与犯罪学杂志29 Fordham law review福特哈姆法律评论 0015-704X30 The George Washington law review 乔治华盛顿法律评论31 Law & society review 法律与社会评论 0023-9216 32 Journal of medical ethics医学伦理学杂志0306-6800 33 The Journal of law, economics & organization 法学、经济学与组织学杂志 8756-6222 34 Harvard journal on legislation哈佛立法杂志 0017-808X35 Indiana law journal(Indianapolis, Ind :1926)印第安纳法律杂志36 The Journal of research in crime and delinquency 犯罪与少年犯罪研究杂志37 Harvard journal of law &public policy 哈佛法律和公共政策杂志 0193-487238 The British journal of criminology 英国犯罪学杂志 39 Medicine,science, and the law 医学、科学与法律40 The Business lawyer商务律师0007-6899 41 International journal of law and psychiatry 国际法律与精神病学杂志 0160-2527 42 Ecology law quarterly生态法季刊0046-112143 University of Illinois law review 伊利诺斯大学法律评论 44 The journal of clinical ethics 临床伦理学杂志 45 Iowa law review依阿华法律评论 46 Washington law review(Seattle, Wash :1967) 华盛顿法律评论47 Harvard civil rights-civil liberties law review 哈佛公民权利—公民自由法律评论 0017-8039 48 Criminal justice and behavior 刑事审判与犯罪行为49 Wisconsin law review 威斯康星法律评论 0043-650X50 Administrative law review行政管理法评论51 Judicature 司法0022-580052 Crime and delinquency 犯罪与少年犯罪53 Criminal law review(London,England) 刑法评论54 Law & social inquiry 法律与社会调查0897-654655 Psychology,public policy, and law 心理学、公共政策与法律56 The American criminal law review 美国刑法评论57 University of Pittsburgh law review 匹兹堡大学法律评论0041-991558 The Washington quarterly 华盛顿季刊0163-660X59 The Journal of forensic psychiatry 法庭精神病学杂志0958-518460 The Journal of law ,medicine & ethics 法律、医学与伦理学杂志61 Journal of legal education 法律教育杂志62 Behavioral sciences & the law 行为科学与法律0735-393663 The American journal of comparative law 美国比较法杂志0002-919X64 Family law quarterly 家庭法季刊65 Harvard international law journal 哈佛国际法杂志0017-806366 Food and drug law journal 食品与药物法杂志67 Common Market law review 共同市场法律评论68 International review of law and economics 国际法律与经济学评论69 Journal of criminal justice 刑事审判杂志70 Journal of maritime law and commerce 海事法与商业杂志0022-241071 Louisiana law review 路易斯安那法律评论0024-685972 The American bankruptcy law journal 美国破产法杂志0027-904873 Federal probation 联邦缓刑制74 The Columbia journal of transnational law 哥伦比亚跨国法律杂志0010-193175 Buffalo law review 布法罗法律评论 76 The Banking law society 银行法杂志77 Journal of law and society法律与社会杂志0263-323X78 Columbia journal of law and social problem 哥伦比亚大学法律与社会问题杂志 79 Denver University law review 丹佛大学法律评论 0883-940980 Law library journal 法学图书馆杂志81 Law and philosophy法律与哲学 0167-5249 82 Journal of legal medicine(Chicago,III) 法医杂志 0194-7648 83 Law and contemporary problems 法律与当代问题 0023-918684 Social & legal studies 社会与法律研究85 Issues in law & medicine法学和医学问题8756-816086 The Australian & New Zealand journal of criminology 澳大利亚和新西兰犯罪学杂志87 International journal of the sociology of law 国际法律社会学杂志 0194-659588 Ocean development and intenational law 海洋开发与国际法 89 The American journal of legal history 美国法律史杂志 90 Cornell international law journal 康奈尔国际法杂志91 American business law journal美国商法杂志 0002-776692 Stanford journal of international law 斯坦福国际法杂志93 Psychology, crime & law心理学、犯罪与法律 1068-316X94 The Tort & insurance law journal 民事侵权与保险法杂志95 Crime, law and social change犯罪、法律和社会变革 0925-499496 University of Louisville journal of family law路易斯维尔大学家庭法杂志97University of Pennsylvania journal of international economic law 宾夕法尼亚大学国际国际经济法杂志98 Copyright world 版权界99 Journal of international banking law 国际银行法杂志100 California lawyer 加利福尼亚律师101 Securities regulation law journal 证券管理法律杂志102 Houston law review 休斯敦法律评论103 Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA 美国版权学会杂志104 Kentucky law journal(Lexington,Ky.) 肯塔基法律杂志105 Annual review of banking law 银行法评论年刊106 Indiana law review 印第安那法律评论107 University of Kansas law review 堪萨斯大学法律评论0083-4025 108 North Carolina law review 北卡罗来纳法律评论109 South Carolina law review 南卡罗来纳法律评论110 Labor law journal 劳动法杂志0023-6586 111 New England law review 新英格兰法律评论112 American journal of family law 美国家庭法杂志0891-6330 113 The Australian law journal 澳大利亚法律杂志114 Southern illinois University law journal 南伊利诺斯大学法律杂志0145-3432 115 Chinese law and government 中国法律和政府0009-4609 116 Russian politics and law 俄罗斯政治与法律[文档可能无法思考全面,请浏览后下载,另外祝您生活愉快,工作顺利,万事如意!]。

*Unit One Legal systemfederation联邦制federalism联邦制度/政治jurisdiction 管辖权(区)legal system 法律体系legal tradition 法律传统legal method 法律方法civil law system 大陆法系common law system 普通法系royal court 女王法庭legislation 立法petition 申请,诉求Court of Chancery 大法官法庭、衡平法庭discretion自由裁量(权)equity 衡平法Twelve Tables 十二表法Canon law 教会法source of law 法律渊源civil code 民法典private law/public law私法/公法law doctrine 法条legal education 法学教育tribunal 审判员席,法官席;特别法庭breach of contract 违反合同precedent 先例,前例predictability 可预期性legal doctrine 法律原则stare decisis 遵循先例trial court初审法院、审判法院intermediate appellate court 中级上诉法院Supreme Court of the United States Res Judicata 已决事件[已裁决的案例]reversal 撤销;推翻[下级法院的裁决]overrule 推翻判决,驳回judicial precedent 司法先例plaintiff (民事)原告defendant (民事、刑事)被告the accused (刑事) 被告a right of privacy 隐私权the losing party 败诉方bring one’s suit against sb 起诉reverse the decision 推翻裁判binding 有约束力的reasoning 推理dictum 法官的附带意见Unit Two Court Systemcourt of last resort 最高上诉法院Court of Common Pleas普通诉讼法院out-of-state lawyer州外律师inferior trial court初级法院petty trial court小型审判法院trial court of general jurisdiction 具有一般审判权的初审法院Superior Court高级法院、上级法院District Court地区法院Supreme Judicial Court最高法院diversity of citizenship多样公民身份管辖venue审判地judicial circuit巡回审判区Federal Circuit court 联邦巡回法院Court of Customs and Patent Appeals 海关和专利上诉法院en banc法庭全体法官【出庭审理案件】certiorari 调卷令barrister出庭律师solicitor初级律师prosecutor公诉人subpoena传票inquisitional审问的、审问的magistrate地方法官、治安法官Unit Three Constitutional Law vital role 重要的法条democracy 民主政体bond 合约popular sovereignty 人民主权checks and balance 制衡separation of powers 分权procedural safeguards 程序保障framer 制定者(尤指立宪者)suffrage选举权Articles of Confederation 邦联条例amendments 修正案Constitutional 宪法legislature立法机构Senate 参议院legislative power 立法权executive power 行政权judicial power 司法权necessary-and-proper clause of the Constitution 宪法中的必要性和合理性条款United States Supreme Court ruling 美国联邦最高法院的裁决powers and duties 权力和职责impeachment 弹劾Supreme Court (美)最高法院discretion 自由裁量权criminal cases 刑事案件crime of treason 叛国罪original jurisdiction 原审管辖appeal 上诉ratify 批准alteration 修改submit 提交representation 代表approval 通过resolution 决议implementation执行tyranny 专制bail 保释金;保释;保证人enactment 制定(法律);(制定的)法律constitutional convention 宪法惯例;立宪大会authority权力due process 正当法律程序full faith and credit 完全的信赖和尊重privileges and immunities clause 特权和免责条款process of amendments 宪法修正程序national convention 全国性修宪会议judicial review 司法审查Unit Three BJurisdiction n.司法管辖区judicial review n.司法审查government structure 政府结构hierarchy n.等级制度precedence n.先例the Senate 参议院commission n.委任状mandate n./ vt.命令;授权a writ of mandamus上级法院给下级法院的训令appointment n.任命;约定;任命的职位tenure n.任期;vt.授予…终身职位desegregation n.废止种族歧视nullify vt.使无效,作废;取消judiciary n. 司法部门、制度statute n.制定法;法律vest v.授予;归于cede vt.放弃、割让rescind vi.废除;撤回;解除fraudulent adj.诈骗性的thwart vt.妨碍、挫败acquiesce vi.默认、默许sidestep vt.回避syllogism n.推论;诡计supremacy clause 最高条款constitutional right 宪法权利constitutional crisis 宪法危机constitutional interpretation 宪法性解释congressional enactment 议会颁布的法令criminal proceeding 刑事诉讼程序the Judiciary Act 司法法executive privilege行政特权Unit Four Criminal Law restitution 返还原物;恢复原状;tort 侵权civil/crime wrong 民事不法行为/刑事违法press charges/bring charges 起诉prosecutor 公诉人general/special/punitive/exemplary damages 一般/特别/惩罚性/惩戒性损害赔偿金substantive/procedural law 实体法/程序法statute/ordinance 制定法,成文法/条例,法令apprehension 逮捕Miranda warnings 米兰达警告felony/misdemeanor/infraction 重罪/轻罪/一般性违法Incarceration 监禁,下狱motive (犯罪) 动机intent (犯罪/侵权)故意mens rea 犯意actus reus 犯罪行为causation 因果关系acquittal 无罪判决,宣告无罪justifiable 可证明是正当的commission 犯下(罪行)legal concept 法律概念strict liability 严格责任制度self-defense 正当防卫criminal liability 刑事责任a first degree murder 一级谋杀罪capital punishment/death penalty 死刑the U.S Constitution 美国联邦宪法the Bill of Rights 人权宣言Amendment to Constitution宪法修正案inflict on 使、、、遭受underprivileged 享有较少权利的、被剥夺基本权利的disproportionate 不相称、不成比例aggravating circumstance 加重情节a first degree murder 一级谋杀mitigating circumstance 减轻情节judicial review 司法审查sentencing discretion判决自由权irrevocable 不可撤销unconstitutional 违宪的deliberately 故意地a bank robbery 银行抢劫beyond a reasonable doubt 排除合理怀疑imprisonment 监禁detention 拘留fine 罚金court costs 堂费Equal Protection Clause 平等保护条款be vested with wide discretion 被授予广泛的自由裁量权legislative enactment 立法statutory ceiling 法定上限forfeiture 没收;没收物; 罚金economic sanction 经济制裁contraband 违禁品Uniform Controlled Substance Act 统一控制物质法Unit Five Criminal Procedurepresumption of innocence 无罪推定self-incrimination 自证其罪adversary system 对抗制;inquisitorial system 纠问制preventive detention 防范性监禁double jeopardy 双重追诉的危险search and seizure 搜查和查封actus reus 犯罪行为mens Rea 犯意bill of information起诉书complaint 诉状the grand jury process 大陪审团程序booking 登记arrest 拘留in custody 被监管;被拘留contraband 违禁品preliminary investigation 初步调查decision to prosecuted 提起指控的决定the initial appearance 首次开庭formal indictment 正式起诉书preliminary hearing 预审the arraignment 传讯insanity 精神错乱bench trial 无陪审团的庭审/法官审判voir dire /selection of jury筛选陪审团opening statement 开庭陈述the prosecutor’s case 公诉人举证motion for a directed verdict 直接裁决的动议the defendant’s present ation辩护词closing arguments 结案陈词jury instruction 陪审团指令jury deliberation 陪审团审议probation 缓刑voluntary/involuntary manslaughter 故意/过失杀人verdict 陪审团的判断、裁定sentence 宣判、判决sentencing guide 量刑指南capital punishment/capital sentence 死刑appeal 控诉、上诉search warrant 搜查令breach the precedent 打破先例good-faith exception 善意例外exclusionary rule 排除原则justiceships 大法官地位(职务、任期)chief justice 审判长、首席法官、法院院长brutal physical force残酷的体罚corporal/physical punishment体罚arbitration 仲裁coerced confession 强迫认罪adjudication 判决、宣告Unit Six Civil Procedureprocedure 诉讼程序action 诉讼(多指民事诉讼);行为,作为wrong不法行为(侵犯个人的不法行为; 公共不法行为)citation法院传票; 警方传讯; 引注ordinance (地方政府)条例,法令homicide 杀人felony 重罪、misdemeanor 轻罪custody监管、监护;羁押;拘禁;监禁custodian 监护人applicable law适用的法律appellate courts 上诉法院burden of proof 举证责任cross-examinations 交叉质证direct-examination 直接质证directed verdict 直接裁决debtor 债务人default 缺席demurrer抗辩execution 执行federal courts 联邦法院motions 议案/动议pleading theory辩护理论personal injury人身伤害property damage财产损害personal jurisdiction属人管辖replead再辩护the parties 当事人sheriff 警长治安官trial court 初审法院trial stage 庭审阶段Unit Eight Tort Lawwarden 警卫;典狱长;监狱长confinement 限制;监禁;拘禁;关押lawsuit 诉讼(尤指非刑事案件) tortfeasor 侵权行为者arguably 可论证的fallibility 不可靠,易混admonitory 警告的、劝诫的cautionary 警戒的substantive 有实质的,独立的litigation 诉讼,起诉sue (民事)起诉punitive damage 惩罚性赔偿compensatory damages补偿性赔偿金circuit court of appeals 巡回上诉法院Unit 8civil wrong 民事不法行为damages赔偿金act or omission 作为和不作为tort liability/ contract liability 侵权责任/合同责任intentional tort故意侵权personal/property tort人身/财产侵权compensatory/punitiv /exemplary damages 补偿/惩罚/惩戒性赔偿金state of mind主观状态circumstantial evidence间接证据false imprisonment 非法监禁trespass to land/ chattels侵入领地/动产right to exclusive use of land 土地的排他性使用权ownership 所有权charge 控罪physical harm 身体伤害standard of care/duty of care注意的标准/义务contributory /comparative negligence 共同/相对过失assumption of the risk 自我承担危险proximate cause近因foreseeablity可预见性actionable 可诉的tortuous/intervening act侵权行为/介入行为strict liability 严格责任privity of contract合同的私密条款deformation/ slander/libel 诽谤/口头/书面诽谤Jury(petty) jury 陪审团grand jury 大陪审团jury trial 陪审团审判right to jury 拥有陪审团审判的权利hung jury 悬案陪审团dismiss a jury 解散陪审团challenge for cause 有因回避peremptory challenges无因回避jury box 陪审团席位jury oath 陪审团宣誓jury selection 挑选陪审团potential/perspective juror 潜在的陪审团成员impartial jury 公正的陪审团jury of one’s peers同阶陪审团(指陪审团成员必须是与被审判者有相同社会背景、处于同一阶层的人员)jury pool待选陪审员库jury summon 陪审团传票juror 陪审团成员bailiff 法警jury instruction/ jury charge(法官)对陪审团的指令deliberation (陪审团)审议unanimous decision 全体一致的裁决simple majority 简单多数Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution 美国宪法第五修正案guilty decision 有罪裁决verdict (陪审团)裁决foreman of the jury 陪审团团长render the verdict (陪审团向法庭)提交裁决speak the verdict (陪审团团长在法庭)宣读裁决fact-finder 事实的发现者jury box 陪审团席位jury room 陪审团审议时witness 证人testimony 证词common sense 常识state attorney 检察官true bill (大陪审团签发的)予以起诉书no bill (大陪审团签发的)不予以起诉书summary judgment 即决判决Jurisdiction n.司法权,审判权,管辖权under the jurisdiction of the trial courtThe court has jurisdiction over this case.territorial/hierarchy/inferior/general/specialized/appellate jurisdiction地域/级别/有限/一般/特殊/上诉管辖权adj. Judicial 法庭的,司法的,法官的a judicial inquiry/review/system 法庭的审讯、复审、司法制度judicial relief 司法救济n. judiciary 一国的法官总称Apply vi/vt实施,适用apply a law/rule 执行法律、规则apply local customs 适用当地的风俗习惯The regulations and rules of local governments apply within respective jurisdiction. apply for a retrial/deferment 申请再审/延期n. application 实施,生效the strict application of the law 严明执法adj. (作表语)applicable可适用be applicable to sb/sthDecision n.判决=judgmentLegislation n.[u]立法legislation of the People’s Congress 人大立法make new legislation=enact a new lawvi. legislate legislate for/agist sthadj. legislative legislative reform 立法改革Procedure n.法律程序civil procedure 民事诉讼程序(对比proceedings 诉讼过程:proceedings against sb/for sth)adj. Procedural procedural rules 程序规则Amend vt.修改Amend the existing/current law 修改现行法=make amendments to the current law Subject n. 法律主体Petition vt/vi 向。

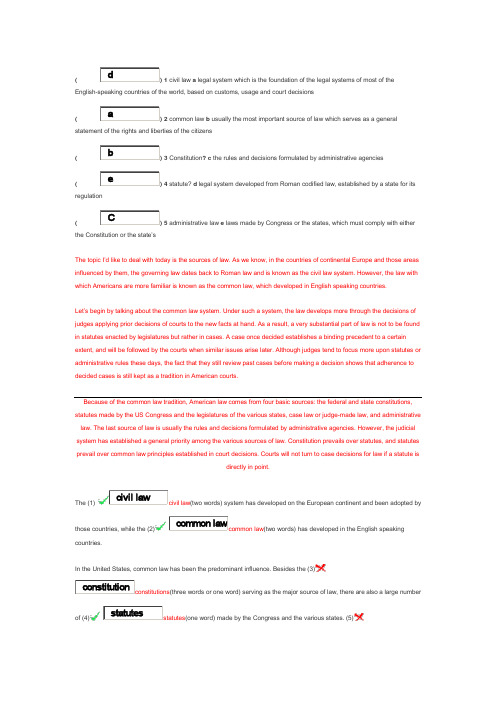

( civil law a legal system which is the foundation of the legal systems of most of theEnglish-speaking countries of the world, based on customs, usage and court decisions( common law b usually the most important source of law which serves as a general statement of the rights and liberties of the citizens(Constitution? c the rules and decisions formulated by administrative agencies(statute? d legal system developed from Roman codified law, established by a state for its regulation( administrative law e laws made by Congress or the states, which must comply with either the Constitution or the state’sThe topic I’d like to deal with today is the sources of law. As we know, in the countries of continental Europe and those are as influenced by them, the governing law dates back to Roman law and is known as the civil law system. However, the law with which Americans are more familiar is known as the common law, which developed in English speaking countries.Let’s begin by talking about the common law system. Under such a sys tem, the law develops more through the decisions of judges applying prior decisions of courts to the new facts at hand. As a result, a very substantial part of law is not to be found in statutes enacted by legislatures but rather in cases. A case once decided establishes a binding precedent to a certain extent, and will be followed by the courts when similar issues arise later. Although judges tend to focus more upon statutes or administrative rules these days, the fact that they still review past cases before making a decision shows that adherence to decided cases is still kept as a tradition in American courts.Because of the common law tradition, American law comes from four basic sources: the federal and state constitutions, statutes made by the US Congress and the legislatures of the various states, case law or judge-made law, and administrative law. The last source of law is usually the rules and decisions formulated by administrative agencies. However, the judicial system has established a general priority among the various sources of law. Constitution prevails over statutes, and statutes prevail over common law principles established in court decisions. Courts will not turn to case decisions for law if a statute isdirectly in point.The (1) (two words) system has developed on the European continent and beenadopted by those countries, while the (2)(two words) has developed in the English speaking countries.In the United States, common law has been the predominant influence. Besides the (3)(three words or one word) serving as the major source of law, there are also a largenumber of (4)(one word) made by the Congress and the various states. (5)(two words), and (6)(two words) are theother two sources of the American law.administrative lawthe body of law that governs the activities ofadministrative agencies of government and isconsidered a branch of public law.行政法civil lawa legal system inspired by Roman law, theprimary feature of which is that laws are writteninto a collection, codified, and not determined byjudges 大陆法common lawrefers to law developed through decisions ofcourts and similar tribunals (called case law),rather than through legislative statutes orexecutive action, and to corresponding legalsystems that rely on precedential case law.普通法statuteis a formal written enactment of a legislativeauthority that governs a country, state, city, orcounty.成文法;法条Why do people hate to get letters from lawyers? They carry bad news. They mean serious business. They're hard to understand. They use strange words. They carry the inherent threat of suit. Why do lawyers send such letters? They mean serious business, and they intend to sue. But must they use those ancient, strange words and be so hard to understand, or can lawyers express serious business and imminent suit using words everyone knows? Whether writing a demand letter to a contract breacher, an advice letter to a client, or a cover letter to a court clerk, the letter fails if the person receiving it cannot understand what it says. All of these letters have one thing in common: They are not great literature. They will not be read in a hundred years and analyzed for their wit, charm or flowery words. With any luck they will be read just once by a few people, followed quickly by their intended result, whether that be compliance, understanding or agreement.Lawyers are Letter Factories ---- We write many, many letters. An average for me might be five letters a day. This includes advice letters, cover letters, demand letters, all sorts of letters. Some days have more, some have less, but five is a fairly conservative average, I would think. Five letters a day for five days a week for fifty weeks a year is 1,250 letters a year. This is my 25th year in practice, so it is quite conceivable that I have written 31,250 letters so far.As you have learned from this unit, the law with which the Americans are more familiar is known as the (1)which developed in English speaking countries. Under such a system, the verdict is made according to the (2)judges applying prior decisions of courts to the new facts at hand. Because of such atradition, American law comes from four basic sources: the (4)law, and administrative law.Speech by Max WilliamThe new culture at Hi-Tech. presents a brand-new intention to everyone after our long and careful preparation. The core concept of our new culture can be summarized in a few words: loyalty, harmony, extensiveness, infinity and creativeness. These words are the combination of doctrines of our traditional culture and modern business management. This core concept has come about through the years of Hi-Tech’s growing experience and is the result of efforts made by many people.When we consider the essence of a country’s culture, it usually reflects the nation's vitality, creativity and cohesiveness. The same is true of a company. The culture of a company reflects its capabilities, which not only define its present status but also determine its future prospects. This new culture will definitely enhance our image and competitiveness in the market.。

法学英文文献在法学领域,英文文献是研究和学习的重要资源。

以下是一些关于法学的英文文献综述。

1. "The Development of Environmental Law: A Comparative Analysis" - 本文综述了环境法的发展,探讨了不同国家环境法的异同,并对环境法的未来趋势进行了展望。

2. "The Evolution of Corporate Governance: A Global Perspective" - 本文回顾了公司治理结构的演变,探讨了不同国家和地区公司治理的差异,并分析了公司治理对企业发展的重要性。

3. "Human Rights Law: A Comprehensive Analy sis" - 本文对人权法进行了全面的分析,包括人权法的起源、发展、主要的人权公约以及人权法在实践中的应用。

4. "Intellectual Property Law: Key Issues and Ch allenges" - 本文讨论了知识产权法的重要问题和挑战,包括专利、商标、版权的保护范围、侵权行为以及知识产权的国际保护。

5. "Comparative Constitutional Law: A Study of Selected Countries" - 本文比较了不同国家的宪法法律制度,包括宪法的基本原则、权力机构的设置以及宪法的解释和适用。

6. "Criminal Law: Theory and Practice" - 本文综述了刑法的基本理论,包括犯罪、刑事责任、刑罚等概念,并分析了刑法在实践中的应用和挑战。

7. "Family Law: Trends and Reforms" - 本文讨论了家庭法的趋势和改革,包括婚姻、离婚、抚养权、家庭暴力等问题,并分析了不同国家和地区家庭法的差异。

国家主权平等原则the equality of sovereignty:管辖权 jurisdiction:海陆空底范围内1、领域管辖territorial jurisdiction:一切在国内或国外的本国人、本国船舶、本国飞行2、国籍管辖nationality jurisdiction器行使管辖:指国家对于外国人在该国领域外侵害该国的国家3、保护性管辖protective jurisdiction和公民的重大利益的犯罪行为有权行使管辖。

重大犯罪、双重肯定:对于普遍地危害国际和平与安全以及全人类的利益4、普遍管辖universal jurisdiction的某些特定的国际犯罪行为,各国均有权实行管辖,不论罪行发生地和国籍为何。

侵略罪、灭绝种族罪、危害人类罪、战争罪、种族隔离罪、奴隶制及相关犯罪、酷刑罪、劫持人质罪、海盗罪、危害国际航空安全罪、毒品罪、危害环境罪等等禁止使用武力或武力威胁原则 General prohibition on the use of force 维也纳外交关系公约》Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations领事关系Consular Relations国书 credentials外交特权与豁免privileges and immunities国际组织的决策decision-making(一)全体一致 unanimity(二)多数表决1、简单多数表决 simple majority voting(1)出席并参加表决的成员国过半数同意。

(2)一般只用于程序性事项。

2、特定多数表决 quantified majority voting(QMV)(1)以规定的过半数以上的多数同意(2)针对重要事项或特定事项的表决(三)协商一致 consensus1、一般包括以下基本内容:(1)程序:在作出决定前,当事各方必须先进行充分而广泛的协商,然后由在场参加协商的主席确定协商一致的事实。

关于“科索沃独立”的法律思考林溢婧;林金良【摘要】2008年2月,科索沃单方面宣告独立,国际社会纷纷作出反应。

以美国为首的一些西方国家对其独立表示承认,而俄罗斯、印度等国家则拒绝承认。

更多的国家则处于观望的状态。

通过从民族自决原则、国家领土与主权完整原则以及联合国1244号决议的法律效力方面入手,探讨科索沃独立的合法性问题。

文章认为,科索沃的独立并不满足民族自决原则的构成要素,违反了国际法中维护国家主权和领土完整的重要原则,违背了联合国1244号决议,不能为其独立提供合法性基础。

美国、西方等国家对科索沃独立的承认也是违反国际法基本原则和国际社会的基本秩序的。

%February 2008, Kosovo unilaterally declared its independence. US-led Western countries acknowledged their independence, while Russia, India and other countries refused to recognize, and more countries are in a wait state. This paper, based upon the principle of national self-determination, national sovereignty, territorial integrity and the principles of the United Nations Resolution 1244, uses the force of law in a bid to explore the legality of Kosovo's independence, and makes further discussion of national recognition.【期刊名称】《泉州师范学院学报》【年(卷),期】2012(030)001【总页数】4页(P64-67)【关键词】科索沃;独立;民族自决;分离权;违宪【作者】林溢婧;林金良【作者单位】北京大学法学院,北京100000;泉州师范学院,福建泉州362000【正文语种】中文【中图分类】D9922005年2月17日,科索沃议会绕过联合国单方面通过了独立宣言,宣布科索沃脱离塞尔维亚,成为“独立、主权和民主国家”。

The Law and Politics Book Review is published on two distribution listsfrom the University of Maryland, College Park. You are currentlyreceiving the full-text, multiple-mailing version, UMD-LPBR-FULL. Thisis a moderated list and does not accept any messages except via theeditor. If you would prefer to receive a more abreviated version of thereviews in a notice format with links to the full-text copy as it ispublished on the LPBR webpage (located at /gvpt/lpbr ), please send the message: subscribe UMD-LPBR <your name> tolistserv@ . More generally, please send all commentsand questions to Wayne McIntosh via E-mail.*************************************************OBJECTIVITY AND THE RULE OF LAW, by Matthew H. Kramer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. 262pp. Hardcover. $75.00/£45.00.ISBN: 9780521854160. Paper. $27.99/£15.99. ISBN: 9780521670104. eBook format. $23.00. ISBN: 9780511287398.Reviewed by Stephen L. Elkin, Department of Government & Politics, University of Maryland. Email: selkin [at] .Is the rule of law a good thing? Matthew Kramer does not think so, atleast not if the question is posed in this way. It might be good butthat depends on moral-political considerations, in particular thepurposes to which the rule of law is put. The rule of law itself issimply the result of a set of conditions, and its existence is morallyand politically neutral: law is simply what a legal system properlydefined produces, whether that is good or bad.Readers familiar with the debate between H.L.A. Hart and Lon Fullerwill recognize the provenance of this argument. It parallels the casemade by Hart, but Kramer, strikingly, builds much of the book onarguments made by Fuller. He does so, by dividing Fuller into two theorists as it were: a positivist who argues, with Hart, that law iswhat comes out of a legal system defined by certain characteristics, and a normative theorist who talks about the *inner morality of thelaw.* In spite of Fuller spending a good deal of his intellectuallife arguing that this division cannot be made * the empirical and normative are necessarily joined with regard to the rule of law *Kramer thinks little if anything is lost and much is gained by doing it. The result is too often unconvincing, with the result that his effort to outline, at least partly, a philosophy of law is substantially weakened.But before getting to these matters, it is important to note that thebook is presented as an introduction to the topic of the relationbetween objectivity and the rule of law, and is part of a series of Cambridge University Press introductory volumes on philosophy and law. One wonders, however, for whom this particular volume is meant as an introduction. Certainly American undergraduates, even very bright ones, are unlikely to get very far into the book once they realize they aregoing to be dragged through a bevy of distinctions (about 100 pages worth) on types of objectivity which, if they are going to follow them, will require that they remember with some precision the meaning of terms such as *determinate concreteness* and *transindividual discernibility.* Of course, it might be that such a detailed * and Iam sorry to say rather clumsily written * discussion might be necessary for a competent understanding of the rule of law, but, as Iwill say in a moment, this is apparently not the case. So, the book will not well serve such students. Alas, it is also not likely to be a veryuseful introduction for scholars who want to get a sophisticated overview of a field about which they know little. Not the least of thereasons is that Kramer regularly says that he cannot go into this particular argument because space forbids it. But too often this isexactly what a scholarly reader [*284] will want. The book is then notfor him or her. What then about graduate students? A case could be made in behalf of the book in this respect, but, for myself, I would be disinclined to assign a book to a graduate student trying to work up afield in law and philosophy that uses Fuller*s argument in exactly theway he argued against and that fails to give any real sense of why he argued as he did. Better to assign Hart and Fuller themselves.Again, before turning to the division of Fuller, there is a puzzle inthe way that Kramer wends along his positivist way. On page 109 he says that Fuller*s eight elements of what makes for a legal system are necessary if it is to exist, while on page 143 he says they arenecessary and sufficient. Quite apart from the obvious ways in which the difference between the two matters, it is worth considering what the difference means for matters of practice. Of considerable importance in this regard, it is worth noting that if the elements of a rule of lawsystem are necessary but not sufficient, those who wish to realize itwill likely run into the following problem: they can make progress in serving some of the other non-necessary conditions but at the cost of reaching whatever threshold is needed for elements that define the ruleof law. Concretely, a common problem for those concerned with promoting the rule of law is that the kind of democratic politics that holds aregime together * a variety of favors and political deals * willoften make it harder to put in place elements of the rule of law such as implementing the law on the books. Now Kramer in his discussion in this book of what a legal system is, is not concerned with the problem of creating one, but if he is otherwise so concerned, then it matters very much which it is: the elements are necessary, or necessary andsufficient. Perhaps the matter could be put this way: if the rule of law requires something more than the standard elements such as lack of contradictions, generality, and so on * these are necessary but not enough * and the rest of what is needed includes features ofdemocratic political life, then not only will positivist accounts of therule of law need to look different than they typically do, Kramer*s included. These accounts will also soon become embroiled in the kinds of questions of good practice that they are designed to avoid as they go about defining just what a legal system is.An additional problem * not in the first instance a matter ofpractice * arises if the elements of a legal system are necessary butnot sufficient: why single out the particular elements Kramer does andnot others? Although it is certainly possible that Kramer could showthat there are no other necessary conditions for a legal system toexist, it would be nice to have an argument to this effect since itmight be that when closely examined, the conditions that make for sufficiency * that are not only necessary * have (again) a certain normative character. Might we not end up having to mix positive and normative elements in our definition of a rule of law system as the distinction between necessary and sufficient proves difficult to maintain? My worry here leads me to raise the more general and important question of whether dividing Fuller*s soul into positivist legalscientist and normative legal philosopher, and with him, much of legal theory is both compelling and valuable. I will proceed by example.[*285]Kramer notes, with many others, that legal norms must be *addressedto a general class of persons* (p.110). But is it really the case, ashe argues, that this is a morally or political neutrally matter? Such anorm, he says, must and will be at work in a legal system with malevolent purposes as well as in good ones. Simplifying a bit,Kramer*s argument here is that, since legal systems are designed to coordinate behavior * any sort of behavior, including slavery and thelike * a system that lacks this kind of generality simply cannotfunction and as such will not be a legal system at all. Really? Many readers will be able to think of legal systems * that is, systemsthat indeed coordinate behavior above the kind of threshold Kramer regularly invokes (without being very specific) * and that conspicuously do not regularly address legal norms to such a class of persons. The American system of slavery is an obvious example: behavior was nicely coordinated, one might say, but by definition there was one law for the slaves and one for the free. How about caste systems? The answer is plausibly much the same. It is easy enough to see what the problem is: by talking about *coordination* of behavior and thelike, Kramer means to say that generality is needed not because it is a good thing * a legal system can be used for evil purposes * but forthe morally neutral purpose of , we might say, efficient behavior. But once it is clear that we can have lots of coordination and limited generality * at least with regard to what most people would considerthe most important areas of life, e.g. the ability to buy and sellproperty (historically denied to classes of people) as opposed to say traffic laws where slaves might be addressed in the same fashion as the free * then the natural conclusion is that we prefer generality for normative reasons. That is, we prefer it for just the reasons for which proponents of the rule of law have generally argued: it is unjust touse the law to pick out certain people or class of peoples and treatthem badly. More importantly, it tells us that some kinds of failures of generality are a good deal more important than others formoral-political reasons, and thus why we should set the threshold fordefining whether we have the rule of law in one place rather than another.Much the same point can be made with regard to whether the legal rules can be readily known by those to whom they are addressed. Kramer comments (p.113) that if they are not generally known *the ostensible legal system would be thoroughly inefficacious in channeling people*s behavior.* Well, yes, if they are little known across all or most domains of behavior. But how about if the rules concerning what a political crime is are mostly secret while the rules about crossing the street, getting a residence permit and who is eligible for what state benefits are well known. And suppose that the authorities secretly define what is covered by the idea of a political crime very broadly,are people*s behavior channeled? Yes indeed, except that somenon-trivial number of these people are being channeled right to the gulag. But that is, of course, not the real point, except for those whoget sent there. It is rather that talk about channeling behavior doesnot settle the question of how much and indeed what kind of publicity of legal norms is needed if there is to be a legal system. Once again, the old time religion of the rule of law suggests that how much publicity about what legal norms is best [*286] settled by looking tonormative-political criteria.In the end, I think the question is partly * to stretch a term * ideological. The real choice is how we prefer to think about the world. As a matter of fact, I think, legal positivism cannot be sustained for reasons suggested above. But I would rather, for the moment, put the point this way. What is to be gained by talking about a malevolent rule of law system. The answer presumably is clarity: the rule of law is one thing, a good rule of law another. But if this pushes us into sayingthat either there was or was not a rule of law system at work in the United States in 1860 (I use this example to avoid the outrage engendered on both sides of the legal positivism debate when Nazi Germany is introduced), then I am dubious about the gain in understanding the rule of law or the United States. It would be a lot more helpful to say that in the 1860, the US had a very flawed rule of law: it worked reasonably well for white people and barely at all for black people, and that, starting with the Civil War amendments, the US moved closer to a full realization of the rule of law * and that was altogether a good thing. In short, it is clearer to say that the rule oflaw just is both a normative and empirical concept * and it is thus both easy and natural to talk about more or less of the rule of law and why we want more of it. I do not mean to say here that positivists cannot usefully talk about good practice with regard to the rule of law.I just prefer fewer intellectual handstands than they habitually make in efforts to do so. I do not myself find that I have any trouble keeping clear which are normative and which empirical factors when I say they are joined together in the rule of law. It does not seem any harder than remembering that there can be a malevolent rule of law system. Similarly, I do not ordinarily get baffled looks when I say things like, the generality of law helps coordinate behavior and is also necessary for justice. I would even go so far as to say that I might get looks of comprehension if I said that any plausible account of what it means to coordinate behavior leads us to questions of efficiency and Pareto optimality * and that these in turn are species of utilitarian judgment. I might even get a smile when I conclude that even if coordination could be separated off from justice or fairness, it would thus still be a normative judgment.In this context, it is worth emphasizing that Fuller was a lot clearerthan Kramer (although not as clear as he might have been) about the kind of normative purposes the rule of law serves. He was concerned not with some abstract conception of coordinating behavior * assuming that were possible to define, which I doubt it is. Rather, Fuller was a liberaland ultimately valued law as a (perhaps the) way of making it possible for individuals to pursue their purposes in effective ways. Law is the servant of liberty * and the internal morality of law is inextricably linked to the external morality of liberalism. Now, it is of course possible to have a measure of the rule of law in broadly non-liberal regimes. But, alas, for the proponents of such regimes, the rule of law inevitably provides a measure of individual liberty within them. Fuller, I believe, would have agreed.Perhaps a good way to formulate the difference in view between Kramer and me (not to mention between Kramer and [*287] Fuller as he wrote as opposed to the dismembered Fuller Kramer presents) is whether the moral-political value of the rule of law is external to it or internalto it, it*s inner morality. I will only add in this regard that Isuspect that we would all be better off if we stopped writing about the virtues of positivist and other views of the rule of law, and examine what difference it makes for our understanding of, say, the Polish legal system in 1960 if we approach it a la Kramer or Fuller. I would say much the same thing about how much is to be gained in such understanding if we traverse Kramer*s discussion of objectivity * the connection tohis positivism being that both stem from an aspiration to be scientific: opinion and normative matters are to be sternly put aside. Kramer tells us after the almost 100 pages on objectivity, and about 40 pages from the finish of a 232 page book, that *nothing of practical importancewill be settled by reference to* his discussion of*mind-independence.* This is the first aspect of objectivity hediscusses in the book.********************** Copyright 2008 by the author, Stephen L. Elkin.。

.

.

Sovereignty of law剑桥大学法律法学

Cambridge University Press 2

pluralism. Or can the State give special recognition to a

singlereligion? Is even the existence and recognition of an estab-lished

church consistent with that ideal? Some Strasbourgcases provide food for

thought on these issues. Consider thecase of Serif v. Greece. 5The

applicant was elected Mufti, or religious leader, ofthe Muslim community

in Thrace, although another Muftihad already been appointed by the State.

The applicant wasconvicted of having usurped the functions of a minister

of reli-gion, and of having worn the robes of such a minister,

withouthaving the right to do so. Before the Court of Human Rightsthe Greek

Government contended that it was necessary for theauthorities to

intervene to avoid creating tension betweendif f erent religious groups

in the area.The Court observed that tension between competingreligious

groups was an unavoidable consequence of pluralism.The role of the

authorities, however, was not to seek to removethe cause of the tension,

thereby eliminating pluralism; rather,it was to ensure tolerance between

the rival factions. In ademocratic society, according to the Court, there

was no needfor the State to intervene to ensure that religious

communitiesremained or were brought under a unif i ed leadership.The Court

accordingly found that the reaction of theauthorities constituted a

violation of the Convention.Another issue under the head of religious

freedom iscurrently causing much concern. How far should the lawprotect,

and how far may it prohibit, the manifestation of reli-gious beliefs, for

example, by way of dress or religious symbols?

15[] ECHR .

The issue has arisen in several countries in Europe with thequestion of

the wearing of garments prescribed by religion,such as the Islamic

headscarf. It came before the StrasbourgCourt in a Turkish case, Leyla

Sahin. 6 The University ofIstanbul decided that students wearing the

Islamic headscarfwould be refused admission to lectures, courses and

tutorials.The Court (Grand Chamber) held in 2006, by sixteen votes toone,

that there ...