标记理论

- 格式:doc

- 大小:64.00 KB

- 文档页数:11

标记理论探析1 引言标记理论(markedness theory)是以标记概念为基础,是语言学中用以分析语言系统的一条重要原则。

根据这条原则,对立的语言成分或特征被赋予不同的值,赋予正值即为有标记的(marked),赋予负值或中和值则为无标记的(unmarked)。

标记理论的主要目的是通过分析语言各子系统中的标记现象来建立语言的标记模式(markedness pattern)。

这一理论是二十世纪三十年代由布拉格学派首先提出,距今已经历了近七十年的发展。

其间,生成音系学、语言类型学、生成语法学、功能语法学等从不同的角度将标记理论应用于分析和描写语言中的种种标记现象和特征,从而在不同程度上对标记理论的发展做出了自己的贡献。

本文拟就标记理论及其相关的几个基本问题——标记理论的涵义、标记确定的标准和标记转移现象作一初步探讨。

2 标记理论的涵义标记理论的基本涵义是:在语言中,相对于有标记成分而言无标记成分更为基本,更为自然,更为常用。

然而,在不同的语言学流派中,标记理论的涵义却不尽相同。

(1)根据布拉格学派,在两个对立的语言成分中具有某一(区别性)特征的成分是有标记的,缺少某一(区别性)特征的成分是无标记的。

例如在/t/和/d/这两个对立的音素中,前者是无标记的,因为/t/没有浊音(voicing),而后者则因为有浊音而成为有标记。

再比如英语名词的“数”,复数是有标记的,一般要加-(e)s,而单数为无标记,不加-(e)s。

根据Croft (1990),布拉格学派的标记理论是绝对的二分模式,即某一语言成分要么为有标记,要么为无标记。

(2)在语言类型学中,标记概念是指语言成分(如屈折变化)的非对称现象。

那些普遍性的或多数语言存在的特征为无标记的,而那些为某一语言特有或少数几种语言可见的特征则是有标记的。

类型学中的标记理论是建立在跨语言的比较分析之上,所以标记概念已不再是传统意义上(即布拉格学派的标记理论)的绝对概念,而是一个相对概念。

标记理论的介绍作者:马丽利来源:《活力》2015年第21期[摘要]在任何语言体系中,都存在着对立但不对称的现象。

标记理论便是基于对这一现象的阐述而被广泛应用到语言范畴的各个层面之中。

标记理论的研究不仅有助于我们更全面地了解与掌握个别语言的特征,对语言共性和语言变异的研究都作出了巨大的贡献。

本文论述了标记理论的创立、有无标记项的四大判别标准。

[关键词]不对称;标记理论;判别标准一、标记理论的创立语言中的标记现象是指一个范畴内部存在的某种对立但不对称的现象。

例如,在日语的句法领域中,存在“主动”与“被动”这一组不对称概念,动词原形表示主动态,而被动态要将动词结尾按照相应规则变成“られる”的形式。

我们将动词原形称为“无标记项”,将带有“られる”标记的被动形式称为“有标记项”。

有关这种不对称现象的理论称为“标记理论”。

在二十世纪三十年代初,俄国语言学家特鲁别茨柯依最先提出了标记理论。

并将这一概念中的有标记和无标记的对立运用到了音位学中,他认为在音位学中有三种对立。

第一种是有无对立,也可叫做正负对立,即指甲乙两个音位的唯一区别在于某一特征为甲有而乙无。

例如在日语假名中,[が]与[か]的对立即为有无对立。

二者在发音时,前者有声带振动,而后者无声带振动,除此特征外,二者的其他发音特征完全相同。

第二种是程度对立,即指几个音位之间的对立在于具有某一特征的程度不等。

例如英语音标中[i][e][?]的对立在于开口度的大小不等。

第三种是均等对立,即指相对立的音位各有各的区别性特征。

例如英语中[b][d][g]的对立在于分别为唇印、齿音和腭音。

而布拉格学派的雅科布逊同样也是标记理论的创立者之一。

他与特鲁别茨柯依的观点有所不同,他只主张一种对立,即二分对立,一个成分要么是有标记的,要么是无标记的。

也就是说他并不承认特鲁别茨柯依所说的程度对立和均等对立。

他的贡献是把标记理论的运用从音位学扩展到了形态学。

并且,他认为,在音位学中,有标记和无标记的对立是一种排除关系。

标记理论在国外的研究发展阶段摘要:标记理论是研究语言中对立不对称现象的理论,本文简要介绍了国外标记理论发展的五个阶段及其主要成果。

关键词:标记理论;国外;发展阶段;【中图分类号】g640标记是语言学学科中一个重要概念。

语言中的标记现象是指一个范畴内部存在的某种不对称现象。

研究语言中这种不对称现象的理论就叫标记理论(markedness theory)。

标记理论已成为语言界一个主要的理论思想,是近代语言学研究中常用的一种分析语言的手段,可运用于语言的一切方面。

王立非(1991)在国内第一次描述了标记理论从产生到成熟的发展过程,将其划分为四个阶段:特鲁别茨柯依的创立阶段、雅克布逊的发展阶段、乔姆斯基的改进阶段和当代语言学家的扩展阶段。

本文在王立非划分基础上,丰富增加了后来影响力较大的类型学阶段。

一、特鲁别茨柯依——创立音位标记概念阶段20世纪30年代初,布拉格学派(prague school)的代表人物、俄国语言学家特鲁别茨柯依(n.s.trubetzkoy)最早提出了标记概念。

他在其经典著作《音位学原理》(the principles of phonology)中,探讨了不同种类的音位对立,其中标记概念就来源于音位对立的中和现象。

他观察发现:在一种语言里,有些二元对立项总是处于“正负对立”或是“有无对立”中,即在两个对立的音位中,一方具有某一特征,而另一方没有这一特征。

例如英语中/p/和/b/之间的对立,/b/具有“浊化”特征,而/p/不具有这一特征;另外有些二元对立项却在某些位置上出现中和,即两个音位的对立关系在一定的语言环境中消失。

例如英语中/t/和/d/的对立在某些位置上不存在,如出现在词首/s/音后的只能是/t/,而不是/d/,它们之间的对立属于可中和的对立。

依据特鲁别茨柯依的观点,在“正负对立”的二元对立中,具有该特征的成分称作有标记项,没有该特征成分的称作无标记项;而在“可中和对立”的二元对立项中,出现在中和位置上的成分是无标记项(the unmarked term),不能出现在中和位置上的成分是有标记项(the marked term)。

论标记理论和原型理论的关联摘要:标记理论是语言学中用以分析语言系统的重要原则之一。

标记性体现了语言范畴内部存在的对立的不对称关系,这一概念被广泛应用于音位学、语义学、语法分析和语用学中。

原型范畴理论是认知语言学的主要理论之一。

本文试图用原型范畴理论对词语层面上的标记性现象作出解释,来说明两种理论的关联之处。

关键词:原型理论,标记理论,范畴,有标记,无标记一.标记理论标记理论是结构主义语言学的重要理论之一。

布拉格学派的代表人物之一特鲁别茨柯依在《音位学原理》中提出了9种不同的音位对立,其中对标记概念的产生影响最大的是否定对立。

否定对立中,两个对立项除了具有共同的特征外,一个具有确定的特征(肯定形式的特征),另一个则不具有确定的特征(否定形式的特征)。

具有某种特征的为有标记项(the marked term),没有这种特征的为无标记项(the unmarked term)(刘润清,2002:96)。

雅柯布逊将这一概念引入语法和词汇领域,用来描写语法和语义现象。

此后语言学家又进一步发展了音位的标记理论,他们认为,语言系统中有一部分单位负载的意义是中性的,为无标记项;与其相对应的另一部分单位则在中性意义上附加了某些特征意义,为有标记项”无标记项比有标记项更基本、更自然、更常用,而有标记成分传达的信息比无标记成分所传达得信息更精确、更具体(李玉萍,2004)。

标记概念在语言分析的各个层面上均有解释作用,目前这一概念已广泛应用于语言研究的各个分支。

二.原型理论原型理论(prototype theory)是在现代哲学思想的发展、人类学的调查结果和认知心理学实验研究的基础上产生的。

其产生更多的是得益于上个世纪下半叶人类学与认知心理学对色彩词语以及人类家庭亲属词汇的广泛调查与深入研究。

(梁晓波、李勇忠,2006)与亚理士多德开始的经典理论的传统范畴观不同,认知语言学的原型理论认为许多范畴都是围绕一个原型而构成的,判断某事务是否属于某范畴,不是看它是否具备该范畴成员所有的共同特性,而是看它与其原型之间是否具有足够的维特根斯坦所说的“家族相似性”(family resemblance)。

论篇名语言的标记性∗刘云(北京大学计算语言学研究所 北京 100871)提要 篇名语言与自然语言相比有众多差异,本文从标记理论出发给予了统一的解释,指出篇名语言与自然语言相比是一种标记性语言。

文章揭示了篇名语言标记性的种种表现形式,并分析了篇名语言标记性的语用动因,具体包括三个因素:称名性、话题性、经济性。

关键词 篇名语言 标记性 语用动因零、标记理论语言中的标记现象(markedness)是指一个范畴内部存在的某种不对称现象,例如就英语名词的“数”这一语法范畴而言,复数形式是有标记的(marked),一般要加-s标记,如teachers等,单数形式则是无标记的(un-marked),不需加-s。

概括地说,在“数”这一范畴内,复数是有标记项,单数是无标记项。

有标记和无标记的对立是语言里的普遍现象。

沈家煊(1997)指出,有标记和无标记的对立在语言分析的所有层次上都起作用。

人们大多关注语音(如英语“/b/”与“/p/”在有无[带声]上的对立)、形态(如英语“woman”与“man”的对立)、句法(“现在时”和“过去时”的对立,“肯定句”和“否定句”的对立)、语义(如反义形容词“大”和“小”、“深”和“浅”的对立)、语用(如英语初次相识时道声“How do you do”是无标记的,保持沉默则是有标记的),等等。

本文关注的是篇名语句针对自然语句的标记性,认为篇名语句是有标记的,自然语句是无标记的。

因此,本文所称的标记性是从篇章的角度而言的。

一、篇名语言与自然语言的异同篇名语言与自然语言有许多共同之处,自然语言中的词、短语、单句和复句都可以毫无变化地充当篇名,如:(1)狐狸(《当代小说》1998年8期)(2)不归的水手(《北方文学》1993年9期)(3)林业是中国环境资源立法最早最多最快的部门(《中国绿色时报》2002年10月9日)(4)课文是什么?语文教什么?(《福建中学教学》1999年1期)例(1)是词,例(2)是短语,例(3)是单句(只不过没有使用句号),例(4)是复句,这些篇名都可以直接用在自然语句中。

MarkednessFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaJump to: navigation, search"Unmarked" redirects here. For undecorated law enforcement vehicles, see Police car#Functional types.Markedness, a term which originated in linguistics, is the state of standing out as unusual or difficult in comparison to a more common or regular form. In a marked/unmarked relation, one term of an opposition is the broader, dominant one. The dominant default or minimum effort form is known as the 'unmarked' term and the other, secondary one is the 'marked' term. In other words, it is the characterization of a "normal" linguistic unit (i.e. the unmarked term) compared to the unit's possible "irregular" forms (i.e. the marked term). For example, in English, irregular verbs are marked, while regular verbs are unmarked in comparison.In linguistics, markedness can apply, among others, phonological, grammatical, and semantic oppositions, defining them in terms of 'marked' and 'unmarked' oppositions like honest(unmarked) vs. dishonest(marked). Marking may be purely semantic, or may be realized as extra morphology. The term derives from the 'marking' of a grammatical role with a suffix or other element, but has been extended to situations where there is no morphological distinction.In the social sciences more broadly, markedness is used to distinguish two meanings of the same term, where one is common usage (unmarked sense) and the other is specialized to a cultural context (marked sense).Contents[hide]∙ 1 Marked and unmarked word pairs∙ 2 Background in the Prague School∙ 3 Jakobsonian tradition∙ 4 Cultural markedness∙ 5 Local markedness and markedness reversals∙ 6 Universals and frequency∙7 Diagnostics∙8 Markedness in generative grammar∙9 See also∙10 References∙11 BibliographyMarked and unmarked word pairs[edit]In terms of lexical opposites, marked form is a non-basic, often one with inflectional or derivational endings. Thus, a morphologically negative word form is marked as opposed to a positive one: happy/unhappy, honest/dishonest, fair/unfair, clean/unclean and so forth. Similarly, unaffixed masculine or singular forms are taken to be unmarked in contrast to affixed feminine or plural forms: lion/lioness, host/hostess, automobile/automobiles, child/children. An unmarked form is also a default form. For example, the unmarked lion can refer to a male or female, while lioness is marked because it can refer only to females.The default nature allows unmarked lexical forms to be identified even when the opposites are not morphologically related. In the pairs old/young, big/little, happy/sad, clean/dirty, the first term of each pair is taken as unmarked because it occurs generally in questions. For example, English speakers typically ask how old (big, happy, clean) … something or someone is. To use the marked term presupposes youth, smallness, unhappiness, or dirtiness.Background in the Prague School[edit]While the idea of linguistic asymmetry predated the actual coining of the terms 'marked' and 'unmarked' the modern concept of markedness originated in the Prague School structuralism of Roman Jakobson and Nikolai Trubetzkoy as a means of characterizing binary oppositions.[1]Both sound and meaning were analyzed into systems of binary distinctive features. Edwin Battistella said "Binarism suggests symmetry and equivalence in linguistic analysis; markedness adds the idea of hierarchy."[2]Trubetzkoy and Jakobson analyzed phonological oppositions such as nasal versus non-nasal as defined as the presence versus the absence of nasality; the presence of the feature, nasality, was marked; its absence, non-nasality, was unmarked. For Jakobson and Trubetzkoy, binary phonological features formed part of a universal feature alphabet applicable to all languages. In his 1932 article "Structure of the Russian Verb", Jakobson extended the concept to grammatical meanings in which the marked element 'announces the existence of [some meaning] A' while the unmarked element 'does not announce the existence of A, i.e., does not state whether A is present or not'.[3] Forty years later, Jakobson described language by saying that "every single constituent of a linguistic system is built on an oppositionof two logical contradictories: the presence of an attribute('markedness') in contraposition to its absence ('unmarkedness')."[4]In his 1941 Child Language, Aphasia, and Universals of Language, Jakobson also suggested that phonological markedness played a role in language acquisition and loss. Drawing on existing studies of acquisition and aphasia, Jakobson suggested a mirror image relationship determined by a universal feature hierarchy of marked and unmarked oppositions. Today many still see Jakobson's theory of phonological acquisition as identifying useful tendencies.[5]Jakobsonian tradition[edit]The work of Cornelius van Schooneveld, Edna Andrews, Rodney Sangster, Yishai Tobin and others on 'semantic invariance' (different general meanings reflected in the contextual specific meanings of features) has further developed the semantic analysis of grammatical items in terms of marked and unmarked features. Other semiotically-oriented work has investigated the isomorphism of form and meaning with less emphasis on invariance, including the efforts of Henning Andersen, Michael Shapiro, and Edwin Battistella. Shapiro and Andrews have especially made connections between the semiotic of C. S. Peirce and markedness, treating it as "as species of interpretant" in Peirce's sign-object-interpretant triad.Functional linguists such as Thomas Givon have suggested that markedness is related to cognitive complexity—"in terms of attention, mental effort or processing time".[6] And linguistic 'naturalists' view markedness relations in terms of the ways in which extralinguistic principles of perceptibility and psychological efficiency determine what is natural in language. Linguist Willi Mayerthaler, for example, defines unmarked categories as those "in agreement with the typical attributes of the speaker".[7]Cultural markedness[edit]Since a main component of markedness is the information content and information value of an element,[8] some studies have taken markedness as an encoding of that which is unusual or informative, and this is reflected in formal probabilistic definitions of Markedness and Informedness (as chance-correct unidirectional components of the Matthews Correlation Coefficient corresponding to deltap and deltap'.[9]Conceptual familiarity with cultural norms provided by familiar categories creates a groundagainst which marked categories provide a figure, opening the way for markedness to be applied to cultural and social categorization.As early as the 1930s Jakobson had already suggested applying markedness to all oppositions, explicitly mentioning such pairs as life/death, liberty/bondage, sin/virtue, and holiday/working day. Linda Waugh extended this to oppositions like male/female, white/black,sighted/blind, hearing/deaf, heterosexual/homosexual, right/left, fertility/barrenness, clothed/nude, and spoken language/written language.[10] Battistella expanded this with the demonstration of how cultures align markedness values to create cohesive symbol systems, illustrating with examples based on Joseph Needham's work.[11] Other work has applied markedness to stylistics, music, myth.[12]Local markedness and markedness reversals[edit]Markedness depends on context. What is more marked in some general contexts may be less marked in other local contexts. Thus, "ant" is less marked than "ants" on the morphological level, but on the semantic (and frequency) levels it may be more marked since ants are more often encountered many at once than one at a time. Often a more general markedness relation may be reversed in a particular context. Thus, voicelessness of consonants is typically unmarked. But between vowels or in the neighborhood of voiced consonants, voicing may be the expected or unmarked value.Reversal is reflected in certain Frisian words' plural and singular forms:[13]In Frisian, nouns with irregular singular-plural stem variations are undergoing regularization. Usually this means that the plural is reformed to be a regular form of the singular:∙Old paradigm: "koal" (coal), "kwallen" (coals) → regularized forms: "Koal" (coal), "Koalen" (coals).However, a number of words instead reform the singular by extending the form of the plural:∙Old paradigm: "earm" (arm), "jermen" (arms) → regularized forms: "jerm" (arm), "jermen" (arms)The common feature of the nouns that regularize the singular to match the plural is that they occur more often in pairs or groups than singly; they are said to be semantically (but not morphologically) locally unmarked in the plural.Universals and frequency[edit]Joseph Greenberg's 1966 book Language Universals was an influential application of markedness to typological linguistics and a break from the tradition of Jakobson and Trubetzkoy. Greenberg took frequency to be the primary determining factor of markedness in grammar and suggested that unmarked categories could be determined by "the frequency of association of things in the real world".Greenberg also applied frequency cross-linguistically, suggesting that unmarked categories would be those that are unmarked in a wide number of languages. However, critics have argued that frequency is problematic because categories that are cross-linguistically infrequent may have a high distribution in a particular language.[14]More recently the insights related to frequency have been formalized as chance-corrected conditional probabilities, with Informedness (deltap') and Markedness (deltap) corresponding to the different directions of prediction in human association research (binary associations or distinctions) [15] and more generally (including features with more than two distinctions).[9]Universals have also been connected to implicational laws. This entails that a category is taken as marked if every language that has the marked category also has the unmarked one but not vice versa.Diagnostics[edit]Markedness has been extended and reshaped over the past century and reflects a range of loosely connected theoretical approaches. From emerging in the analysis of binary oppositions, it has become a global semiotic principle, a means of encoding naturalness and language universals, and a terminology for studying defaults and preferences in language acquisition. What connects various approaches is a concern for the evaluation of linguistic structure, though the details of how markedness is determined and what its implications and diagnostics are varies widely. Other approaches to universal markedness relations focus on functional economic and iconic motivations, tying recurring symmetries to properties of communication channels and communication events. Croft (1990), for example, notes that asymmetries among linguistic elements may be explainable in terms economy of form, in terms of iconism between the structure of language and conceptualization of the world.Markedness in generative grammar[edit]Markedness entered generative linguistic theory through Chomsky and Halle's The Sound Pattern of English. For Chomsky and Halle, phonological features went beyond a universal phonetic vocabulary to encompass an 'evaluation metric', a means of selecting the most highly-valued adequate grammar. In The Sound Pattern of English, the value of a grammar was the inverse of the number of features required in that grammar. However, Chomsky and Halle realized that their initial approach to phonological features made implausible rules and segment inventories as highly valued as natural ones. The unmarked value of a feature was cost-free with respect to the evaluation metric, while the marked feature values were counted by the metric. Segment inventories could also be evaluated according to the number of marked features. However, the use of phonological markedness as part of the evaluation metric was never able to fully account for the fact that some features are more likely than others or for the fact that phonological systems must have a certain minimal complexity and symmetry[16]In generative syntax, markedness as feature-evaluation did not receive the same attention that it did in phonology. Chomsky came to view unmarked properties as an innate preference structure based first in constraints and later in parameters of universal grammar. In their 1977 article 'Filters and Control', Chomsky and Howard Lasnik extended this to view markedness as part of a theory of 'core grammar':We will assume that [Universal Grammar] in not an 'undifferentiated' system, but rather incorporates something analogous to a 'theory of markedness' Specifically, there is a theory of core grammar with highly restricted options, limited expressive power, and a few parameters. Systems that fall within core grammar constitute 'the unmarked case';we may think of them as optimal in terms of the evaluation metric. An actual language is determined by fixing the parameters of core grammar and then adding rules or conditions, using much richer resources, ... These added properties of grammars we may think of as the syntactic analogue of irregular verbs.[17]A few years later Chomsky would describe it this way:The distinction between core and periphery leaves us with three notions of markedness: core versus periphery, internal to the core, and internal to the periphery. The second has to do with the way parameters are set in the absence of evidence. As for the third, there are, no doubt, significant regularities even in departures from the core principles (for example, in irregular verb morphology in English), and it may be that peripheral constructions are related to the core in systematic ways, say by relaxing certain conditions of core grammar.[18]Some generative researchers have applied markedness to second-language acquisition theory, treating it as an inherent learning hierarchy which reflects the sequence in which constructions are acquired, the difficulty of acquiring certain constructions, and the transferability of rules across languages [REF NEEDED]. More recently, Optimality Theory approaches emerging in the 1990s have incorporated markedness in the ranking of constraints.[19]See also[edit]∙Lemma (morphology)∙Lexeme∙Inflection∙Matthews correlation coefficient∙Marker (linguistics)∙Null morpheme∙Underlying representationReferences[edit]1.Jump up ^ Andersen Henning "Markedness--The First 150 Years". In Markedness inSynchrony and Diachrony. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, 19892.Jump up ^ Battistella, Edwin Markedness: The Evaluative Superstructure of Language.SUNY Press, 1990.3.Jump up ^ Jakobson, R 1932 "The Structure of the Russian Verb" reprinted in Russianand Slavic Grammar Studies, 1931-1981,Mouton,1984.4.Jump up ^ Jakobson, R Verbal Communication. Scientific American 227: 72-80, 19725.Jump up ^ Battistella, Edwin, The Logic of Markedness. NY: Oxford Uniuversity Press,1996,6.Jump up ^ Givôn Thomas Syntax: A Functionai-Typological Introduction,volume2,John Benjamins, Amsterdam 1990.7.Jump up ^ Mayerthaler Willi Morphological Naturalness. Karoma, Ann Arbor,1988.8.Jump up ^ Battistella, Markedness, 1990.9.^ Jump up to: a b Powers, David M W (2007/2011). "Evaluation: From Precision,Recall and F-Score to ROC, Informedness, Markedness & Correlation". Journal ofMachine Learning Technologies2 (1): 37–63.10.Jump up ^ Waugh, Linda Waugh, Marked and Unmarked: A Choice BetweenUnequals in Semiotic Structure. Semiotica 38: 299-318, 198211.Jump up ^ Battistella, Edwin, Markedness, 1990, 188-189.12.Jump up ^ Myers-Scotton Carol (ed.) Codes and Consequences: Choosing LinguisticVarieties. Oxford, 1998; Hatten Robert Musical Meaning in Beethoven: Markedness,Correlation, and Interpretation. Indiana University Press, 1994; Liszka, James J. TheSemiotic of Myth. Indiana University Press, 198913.Jump up ^ Tiersma, Peter. "Local and General Markedness", Language, 1982.14.Jump up ^ Battistella, Edwin, The Logic of Markedness, 1996, 51.15.Jump up ^ Perruchet, P.; Peereman, R. (2004). "The exploitation of distributionalinformation in syllable processing". J. Neurolinguistics17: 97−119.16.Jump up ^ Kean, Mary-Louise, The Theory of Markedness in Generative GrammarIndiana University Linguistics Club, Bloomington, IN, 198017.Jump up ^ Chomsky Noam and Howard Lasnik, Filters and Control. Linguistic Inquiry8.3: 425-504 197718.Jump up ^ Chomsky, Noam. Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin and Use.Praeger,198619.Jump up ^ see Archangeli 1997Bibliography[edit]∙Andersen Henning 1989 "Markedness--The First 150 Years", In Markedness in Synchrony and Diachrony. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin.∙Andrews Edna 1990 Markedness Theory: The Union of Asymmetry and Semiosis in Language, Duke University Press, Durham,NC.∙Archangeli Diana 1997 "Optimality Theory: An Introduction to Linguistics in the 1990s", In Optimality Theory: An Overview. Blackwell, Maiden, MA.∙Battistella Edwin 1990 Markedness: The Evaluative Superstructure of Language, SUNY Press, Albany, NY.∙Battistella Edwin 1996 The Logic of Markedness, Oxford University Press, NY.∙Chandler, Daniel 2002/2007 Semiotics: The Basics, Routledge, London, UK.∙Chandler, Daniel 2005 Entry on markedness. In John Protevi (Ed.) (2005) Edinburgh Dictionary of Continental Philosophy, Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press.∙Chomsky, Noam and Morris Halle 1968 The Sound Pattern of English, Harper and Row, NY∙Greenberg Joseph Language Universals, Mouton, The Hague, 1966.∙Trask, R.L. 1999 Key Concepts in Language and Linguistics, London and New York: Routledge.。

用标记理论浅析英语语言中的性别歧视[摘要]性别歧视是个存在很久的问题,从人类的文明开始就存在着。

长期以来,女性一直被认为是感性、细腻、温柔、依赖性强的代表,而男性则典型的是理性、阳刚、大大咧咧的代表。

传统的性别观严重压抑着女性身上的男性气质和男性身上的女性气质,阻碍了人的发展。

本文从标记理论出发分析英语中的性别歧视现象。

从历史、经济、家庭及社会等四方面分析了性别歧视的原因。

现在人们已意识到性别歧视并开始着手解决这一问题,只要齐心协力,一定会最终解决这一社会问题。

[关键词]标记理论性别歧视原因解决方式[中图分类号]H313 [文献标识码]A [文章编号]1009-5349(2015)07-0074-02语言是社会的一面镜子,它可以用来描述世界和帮助我们更好地认识世界。

社会性别是指人们所认识到的基于男女生理差别之上存在的社会性差异和社会关系。

不难发现,在社会语言上语言本身具有贬义的色彩。

性别歧视是一种特殊的社会和文化建设,多年来一直受到女权主义的挑战。

在一些国家,妇女没有投票的权利,也没有机会参与政府事务。

有的国家,妇女是不允许出现在仪式上的,若必须去公共场所时,她们要用头纱遮住脸。

在许多的西方国家,女性一旦结婚,便失去结婚之前的姓改为随丈夫的姓。

此外,从语言的运用上我们也能看到性别歧视现象。

很多的名言警句及俗语里都暗示了性别歧视。

比如All men are created equal. 这句话里men(男人)指的是所有的人。

man and women,boys and girls这些说法中均把男人、男孩放到前边,而女人和女孩则被放在了后面。

我们不得不承认,以上的句子或词组带有歧视性。

现在人们已开始认识到女性角色重要性。

女性应该受到尊敬,也应该得到公平对待。

最近几年里,大学毕业生的就业问题很显著。

一项调查报告的数据显示,十份简历中平均有一份能得到面试的机会。

56.7%的被调查的女大学毕业生觉得女生的机会较少。

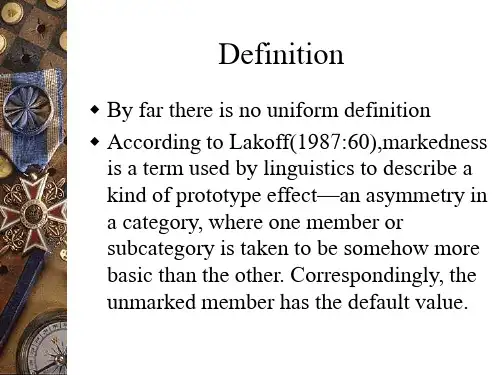

标记理论文献综述作者:吴佩倩来源:《校园英语·上旬》2014年第08期【摘要】标记理论是语言学中一个重要的理论,它在语言分析的各个层面都发挥着十分重要的作用。

本文对标记理论的提出进行了介绍,并且描述了几个主流学派对其的不同定义和划分标准。

目前标记理论正被应用于二语习得和教学等领域,这是目前的研究热点。

【关键词】标记理论语言学学派定义标准一、标记理论的提出标记理论(MarkednessTheory)是由布拉格语言学派首先创立于20世纪30年代初,是结构主义语言学中重要的理论之一。

标记(markedness)的概念最初的提出者是俄国音位学家特鲁别茨柯依。

之后布拉格学派的另一个代表人物雅柯布逊(Jakobson)将其引入词汇和语法领域,用来描写语法和语义现象。

二、不同语言学家对标记理论的定义结构主义语言学家特鲁别茨柯依提出四种可能的音系对立类型,其中表缺对立被定义为标记性。

表缺对立即一对语言特征的两个对立体,如果有某种语言特征,即被认为是有标记的;与之对立的无法确定有无该语言特征的,即被认为是无标记的。

例如:voiced/voiceless,nasalized/non-nasalized,rounded/unrounded。

相似于结构主义语言学家的观点,音系学家把标记理论定义成两个对比的语言学元素:有特定的显著特征的是有标记的,反之则为无标记。

例如,发音/t/和/d/是一个最小配对,t/是/voiced/因此是无标记的,而相反/d/是/+voiced/所以是有标记的。

从语义学者的角度来说,Lyons将标记理论定义成“无标记项是有标记项的上级共词位姊妹单元”例如,在dog/bitch中,dog具有泛指性,包含了“male”和“female”两层含义,是无标记的;而bitch专指“female”语义范围较窄,因而是有标记的。

根据类型学者的研究,那些很普遍的并存在于大多数语言中的特点即为无标记的,反之特定于一种语言或只存在于极少数语言中的则为有标记的。

28作者简介:刘琪,女,中国人民大学文学院硕士研究生。

标记理论下的“被”字句句式语义新解刘 琪(中国人民大学 文学院,北京 100872)摘 要:“被”字句按照标记度大小可以分为无标记“被”字句和有标记“被”字句。

这种标记性不仅体现在句法上,也体现在语义和语用上。

“被”字句(A 被B +V P)句法标记度大小取决于“A”“B”和“V P”三个成分:当A 为原型受事、B 为原型施事、VP 为二价或三价动作动词时,“被”字句是无标记的,其句式语义为“施受/被动关系”。

随着句式标记度的提高,A 不再是原型受事,B 也不再是原型施事,此时VP 往往为心理动词或性状谓词,句式语义强调的是“使因—结果”。

像“被授予”类承赐型“被”字句和“被自杀”类新兴“被”字式,它们都属于高标记的“被”字句,这些句式中不再凸显“施受/被动关系”和“使因—结果”语义,转而凸显的是一种情态语用义,表达主观态度、价值或情感。

“被”字句并不是历来被认为的“一个特殊句式”,而是一组具有共性特征的句式的集合。

标记度的引入解决了以往关于“被”字句句式语义的纷争。

关键词:“被”字句;标记度;句法;句式语义;主观倾向2021年第2期总第704期MODERN CHINESENo.2General No.704现代语文一、引言关于“被”字句到底表示什么样的语法意义,一直以来都是学界争论的焦点,主要观点有:一是以王力为代表的“不幸或不愉快”说[1](P430-433);二是杉村博文的“意外”说[2];三是以祖人植为代表的观点,强调其表“被动”的基本语义性质[3];四是以薛凤生为代表的观点,认为它表示“由于B 的关系,A 变成C 所描述的状态”[4];五是邵敬敏、赵春利的观点,作者认为,“被”是用来引进发生某个动作或行为事件的动因,但因为“被”字句中受动作的影响者才是句子的语义重心,动因则显得不那么重要,往往可以省略,因此,“被”字句可以分为“动因被字句”和“省隐被字句[5];六是施春宏的观点,他指出,“被”字句的语义表示“凸显役事受到致事施加的致使性影响的一种结果”[6]。

标记理论对英语零冠词特殊用法的解释作者:陈小云原苏荣来源:《文教资料》2018年第17期摘要:零冠词在日常英语学习中受到较少的关注,造成学习者对定冠词和不定冠词的滥用。

因为学习者对零冠词的用法不求甚解,尤其对其特殊用法感到困惑。

本研究收集了《朗文当代高级英语辞典》中与零冠词连用较为特殊的两类名词,即与零冠词连用表示机构的名词和与零冠词、介词“at”,“in”,“on”等连用的名词,运用标记论对零冠词的这两种特殊用法进行解释。

最终归纳出零冠词与指称功能之间的关联标记模式,帮助学习者消除对零冠词用法的困惑,能够恰当地使用零冠词。

关键词:标记性理论零冠词用法解释一、引言零冠词(zero article)是指在名词前不加冠词的情况,国内对于零冠词的研究主要集中在语义指称方面。

但是对于一个词在某些情况下用定冠词或不定冠词而在其他情况下又使用零冠词的特殊情况,没有较为详尽的解释。

本文旨在通过标记性理论(Markedness theory)解释零冠词的标记性用法和非标记性用法,从而加深对零冠词的理解,减少过度使用定冠词或不定冠词的情况。

二、冠词的语义区分通常,冠词的语义区分有两个标准:一是特指性,二是定指性。

特指性(specificity)指事物的唯一性和独特性或者概念空间中的唯一,相对不受时空影响的语义范畴(William Frawley,1992: 69)。

而定指性(definiteness)指的是说者认为听者对该信息的已知预设。

相反,如果一个名词是不定指的,则表示这个名词携带着新信息,即听者未知的信息。

(William Frawley 1992: 74)。

因此,Givón(1984: 407)提出了特指性和定指性标度,如图1所示:图1显示了特指性与定指性的关系,定指词往往具有特指性,与定冠词“the”、数词搭配;不定指词既可以是特指又可以是泛指,可以与不定冠词“a(n)”或零冠词搭配;类指词既可以是特指又可以是泛指,与定冠词、不定冠词、零冠词搭配。

标记理论1.引言结构主义语言学以索绪尔的语言符号学说作为诞生标志,主要包括三个分支:布拉格学派、哥本哈根学派和美国描写主义学派。

布拉格学派(The Prague School)在音位学领域做出了突出的贡献。

标记理论(Markedness Theory)是该贡献中的重要方面,对后来的语言学研究产生了广泛的影响。

尤其是其方法论意义影响深远,标记对立作为一种语言分析手段已经广泛应用于语言学的各个分相研究及边缘学科,如;语义学、语用学、语法学、形态学、应用语言学等。

虽然以乔姆斯基为代表的心智主义(Mentalism)在语言研究中处于支配地位,结构主义似乎离我们远去了,从教学的角度讲,标记理论的方法论意义仍不过时。

它在应用语言学研究中的运用有待于进一步探讨。

2.标记的产生背景20世纪20年代,一些著名的语言学家在捷克首都布拉格成立了“布拉格语言学会”(The Linguistic Circle of Prague)。

人们习惯把他们称为布拉格学派。

他们的代表作是特鲁别茨柯依著的《音位学原理》(The Principles of Phonology)。

布拉格学派的主要贡献是区别了语音学和音位学,并创立了“音素”的概念。

在《音位学原理》这本书中,特鲁别茨柯依首次区分了九种音位对立,但与标记概念的产生相关的有第一种表缺对立(Privative Opposition)和第四种中和对立(Netralizable Opposition)。

在论述第一种表缺对立时,特鲁别茨柯依首先采用了“有标记”(Marked)和“无标记”(Unmarked)这组对立概念。

后来雅格布森又进一步调整并规范了音位对立,全部都改成了二项表缺对立(Binary and Privative Oppositions); 用12对声学区别性特征取代了特鲁别茨柯依创立的生理发音动作为基础的对立标准;,而且籍此建立了最小对立体(Minimal Pair),进一步扩大了其使用范围。

区别性特征中的二分(Dichotomy)标记在音位分析、语言描写中起着重要作用,如:[p](-voiced)vs. [b] (+voiced), 清浊性(Voicing)为区别性特征,等等。

3.标记的含义一对语言特征包括两个对立体,有标记的和无标记的。

这种区分意味着某种语言特征的有和不能确定是否有,如果有,即被认为是有标记的;与之对立的不能确定是否有该语言特征的,即被认为是无标记的。

通俗地讲,无标记成份指那些常见的、意见一般的、分布较广的语言成份;而有标记成分则指那些不常见的、意义具体、分布相对较窄的语言成分。

例如,dog和bitch这两个词构成对立,“FEMALE”特征的有和不能确定,构成有标记bitch[-MALE]和无标记dog[+MALE](FEMALE语义特征一般用-MALE表征)。

Bitch是有标记项,只能指母狗,dog是无标记项,既可以指公狗,也可以泛指一般意义上的狗。

无标记性是中性的(neutral),在意义上具有一般性、非特指性,分布比有标记项要广,使用范围比有标项更大。

无标记项甚至可以包括有标记项的意义,这是标记理论的重要内容(谢应光:1998)。

其理论假设是:在整个语言系统中,各个层面的语言单位中有一部分的成份是基本的,其表达的意义是中性的;而另一部分与之对应的成份在该中性意义的基础又添加了特殊的意义,这种特殊意义使其获得“标记”(徐盛桓:1985)。

标记体现在狭义形态、分布、修辞、语法范畴等几个方面。

关于标记的分类,有人把它分为形式标记、分布标记、语义标记。

我个人认为,根据其特点标记可以划分为显性标记和隐性标记两大类,它们交错分布于语言的各个层面。

标记理论自布拉格学派创立以来,已成为语言学各分支学科的一项重要理论,并迅速运用到其它研究领域。

本文首先对标记的概念、标记理论的发展历程等做一番简述,然后重点探讨标记理论在语用学研究中的理论价值和实用价值。

关键词:标记理论;语境;间接言语行为;会话分析;顺应论;Abstract: Since it originated with the Prague School, markedness theory has been an important theory in different sub-disciplines of linguistics, and has been applied to other research fields. This paper begins with a brief analysis of this theory’s concept and development, and focuses upon its theoretic and utility value in pragmatics.Key Words: markedness theory; context; indirect speech act; conversation analysis; adaptation theory1. 引言标记理论(Markedness Theory)是结构主义语言学中一个重要的理论, 由布拉格学派(the Prague School)的音位学家首创于20世纪30年代,是布拉格学派对语言学的重要贡献之一。

根据《朗文语言教学及应用语言学辞典》(理查兹,2000:276)的定义, 标记理论认为:―世界上的各种语言中, 某些语言成分比其它的更基本、更自然、更常见(是为无标记成分),这些其它的语言成分称为有标记的。

‖ 标记性反映在语言的各个层面上,如:音位、词法、词汇、语法、句法等。

这里先以音位层面为例。

音位(phoneme)是音位学(phonology)分析的一个基本单位,是指在一种语言中能够区分两个单词的最小的语音单位。

如: pin和bin这样一对最小对立体(minimal pair)就是由于词首的[ p ]和[b]不同,从而能区分成两个不同的词。

音位层上的标记与无标记现象并不是发生在所有的音位上,而只是发生在成对的音位中,而且两个音位的相关特征涉及某一语音特征的出现与否。

出现相关标记(marker)的叫有标记成分,不出现相关标记的叫无标记成分。

比如:英语中的[t]和[d];[k]和[g];[p]和[b];[s]和[z]等。

在[t]和[d]这一组音位中,[t]是无标记成分,因为[t]是清辅音,而[d]是有标记成分,因为[d]是浊辅音。

也就是说,辅音的浊音特征构成了相关标记。

类似地,在上面这些例子中,前一个皆为无标记成分,后一个皆为有标记成分。

(红色显示的这部分是否也可以省略?)标记现象在语用层面也是随处可见的,此时语言单位的标记性表现为语用标记。

例如,在英语交际中,对别人给予的称赞,应该说―谢谢‖,但如果像中国人那样为了谦虚而不承认甚至否认别人的称赞就是一种语用失误(pragmatic failure),是一种有标记的表达。

同样,有些外国人在与中国人的交往中也会出现因为文化差异所引起的语用失误。

例如,在汉语交际中,中国人习惯于根据自己的观察,通过询问或推测对方在干什么或准备干什么来问候对方,如:―在看电视啊‖、―去买菜啊?‖,等等。

这些表达法都是中国人常用的一般打招呼用语,听话者完全不必在意,只需视具体情况随便作答,而不必作很明确的回答。

但是,初到中国的西方人却对此大惑不解。

他们一是奇怪中国人为何选择日常生活中的琐事作为交际的话题;二是感到浑身不自在,觉得自己的一言一行受到别人的监视,因为在西方人看来,自己在干什么或准备干什么纯属个人隐私,旁人是无权过问的。

所以,不谙中国文化的西方人往往疑惑地反问一句―是啊?‖,或者不礼貌地―回敬‖一句―关你什么事?!‖,诸如此类的回应都是不自然的、不正常的、不符合常规的,是一种有标记的表述。

下面我们将具体探讨标记理论在语用学各研究领域的理论价值和实用价值。

2. 标记理论的语用阐释标记的概念自特鲁别茨柯依(Trubetzkoy)提出以后,历经雅格布森(Jakobson)、乔姆斯基(Chomsky)、莱昂斯(Lyons)等语言学家发展和完善。

标记理论在语言分析的各个层面上,从音位、词法、句法到语法,都发挥着重要作用。

标记理论能帮助我们正确地分析语言的特征,正确地使用语言。

标记理论以其独特的方法论优势在当代语言学研究中扮演着重要角色,这突出体现在语法学、语义学、语用学、范畴学和类型学、社会语言学、语言习得和外语教学、认知语言学和心理语言学等各个学科的研究中。

本文将从语境(context)、间接言语行为(indirect speech act)、会话分析(conversation analysis)、顺应论(adaptation theory)等语用学的角度对该理论进行阐释。

2.1 标记理论与语境语境是语用学的一个核心概念,脱离语境就谈不上语用研究了。

这一点已经成为人们的共识。

许多学者从语境的角度对语用学下过定义,例如:―语用学通常被看成是语境学,研究语言的显性内容(语义)和隐性内容(含义)是如何通过语境发生关系的‖(熊学亮,1999),―语用学是专门研究语境在交际中的作用的学科‖(彭增安,1998)。

由此可见,语境对于语用研究具有重要的意义。

在谈到语境的功能时,何自然等人(2002:118-121)认为,从说话人的角度看,语境会影响说话人在说话内容、表达方式、表达手段等方面的选择;从听话人的角度看,语境有助于听话人确定指称(reference assignment)、消除含糊(disambiguation)、充实语义(semantic enrichment)等。

一句话,语境会影响意义的表达和理解。

美国语言学家Givon对于语用层次的标记现象作过比较全面的探讨,其代表观点就是标记性取决于语境,同一个结构可能在这个语境中是有标记的,而在另一个语境中是无标记的(转引自张凤,1999)。

换言之,标记性和非标记性是可以相互转化的,而在转化的过程中,语境起着决定性的作用。

人们将这种现象称为标记颠倒,即在不同语境下范畴的标记值(marked value)会发生颠倒。

所以,标记性和非标记性会随着语境的动态变化而相互转化。

例如:a. Would you mind closing the window?b.Could you close the window?c. Would you please close the window?d.Close the window.以上四句话都表达同样一个命题(proposition)——请求受话人把窗户关上,但它们具有不同的交际功能,适用于不同的语境。

以a句为例,如果对好朋友说这句话显然不合适,不合常规,此时它就是一种有标记的表述;但如果对上级、长辈或陌生人等说这句话就非常适切,合乎自然,此时它又是一种无标记的表述。