葡萄酒 Hedonic Pricing Model for German Wine_Schamel

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:355.00 KB

- 文档页数:8

德国维拉·普拉达庄园葡萄酒系列葡萄酒界向有「法国红酒,德国白酒」之称号。

德国因地处高纬度,其葡萄酒产区位于北纬47-52度之间,是葡萄种植的最北极限。

在相对寒冷的北半球,充分发挥了寒凉土地的特性,生产出众多富含果香的白葡萄酒。

气温低的土地培育出的特有爽口酸味,是德国葡萄酒迷人的地方。

在美丽的戴德斯海姆有一流的酒庄,其中最知名的是蒙格尔-格鲁克家族(Menger-Krug),家族是出产优质葡萄酒的世家。

自1758年,蒙格尔-格鲁克家族就热衷于种植优质葡萄和酿酒。

我们家族包括维拉·普拉达酒庄(Villa Im Paradies),莫琛巴克酒庄(Motzenbäcker),格鲁克庭院酒庄(Krug’scher Hof)。

001 维拉·普拉达庄园优质干白市场价228元该酒呈清澈的浅黄色,新鲜的花香和热带水果果香相结合,口感清爽怡人优质高级葡萄酒(Qualitatswein mit Prädikat, 简称QmP) 是德国葡萄酒质量等级的最高级别,酒庄出产的每批QmP葡萄酒都要通过德国官方严格检测,并且不允许补糖。

德国葡萄酒等级中的最高级别QmP 级别,适合存贮窖藏产品类型:干白产区:莱茵黑森葡萄品种:白皮诺最佳饮用温度:冷藏6℃-10℃002维拉·普拉达庄园头等干白 市场价328元003维拉·普拉达庄园贵族精选白葡萄酒 市场价598元这是一款典型的德国雷司令。

葡萄生长在35年的葡萄树上,核果香,酒香及各式花香完美结合,带给您层次丰富酸度适中的口感德国葡萄酒等级中的最高级别QmP (kabinett )级别,适合存贮窖藏产品类型:干白产区:法尔兹葡萄品种:雷司令最佳饮用温度:冷藏6℃-10℃金黄的液体,浓郁的果香,清新的花香,香醇的酒香,甜度和浓度恰到好处,雷司令优雅高贵的气质彰显到极致德国葡萄酒等级中的最高级别QmP Auslese(精选)级别,适合存贮窖藏产品类型:半甜白产区:莱茵黑森葡萄品种:雷司令最佳饮用温度:冷藏6℃-10℃004维拉·普拉达庄园月亮木雷司令 市场价668元005维拉·普拉达庄园月亮木干白 市场价628元这款非常特别的雷司令,葡萄放在一个按照月亮盈亏变化来采伐的橡木桶里面发酵。

酒店运营管理知到章节测试答案智慧树2023年最新上海商学院第一章测试1.行业结构不合理造成酒店业过度竞争的现象不存在。

参考答案:错2.对于单体酒店来说,立根的基础是当地的人文和区域特色。

参考答案:错3.完善服务体系,实现“线上+线下”完美的双模式在明确酒店定位后,重要的是提升酒店的软实力,即是酒店的服务水准和附加价值参考答案:对4.互联网思维非常注重人的价值,尤其是对酒店行业来说,抓住接触、沟通和服务客户的各种方式,就是“以人为本”宗旨的最重要体现。

参考答案:对5.未来中高端酒店产品需要考虑的是特色和品质,而不是规模。

参考答案:对6.跨界合作可以为酒店投资人创造更多共赢的市场机会。

参考答案:对7.酒店与互联网的冲突就在于关联性,即是酒店的宣传印象和真实体验的完整度和期望度是否维持在理想的落差之中。

参考答案:错8.互联网+计划的目的在于充分发挥互联网的优势,将互联网与传统产业深入融合,以产业升级提升(),最后实现社会财富的增加。

参考答案:经济生产力9.当前,以( )为标志的民宿民俗风酒店盛行。

参考答案:风景旅游名胜;异国风情;鲜明地域特色10.对于单体酒店来说,立根的基础更多的是(),很少能扩大范围跨越地域传播。

参考答案:当地的人文和区域特色第二章测试1.酒店投资成本不可逆性是指由于投资失败导致投资成本部分或全部变成沉没成本,使得无法收回成本。

参考答案:对2.酒店投资的不确定性是指投资者可以相对清楚的知道未来投资收益状况。

参考答案:错3.酒店投资类型可以多样化,如可以进行酒店的产权投资,也可以非产权投资(租赁)。

参考答案:对4.酒店业主可以通过酒店折旧为酒店收入提供税收庇护。

参考答案:对5.一个酒店项目的开发除了开发商,还需要酒店管理公司负责对项目的论证、建筑及内装设计等工作。

参考答案:错6.为使酒店开发更为科学合理,下列哪个公司应尽早参入酒店项目的规划及建设( )参考答案:酒店咨询及管理公司7.请将下列酒店开发的基本步骤按顺序排列()参考答案:项目运营阶段;项目报批阶段;概念化设计阶段;可行性分析阶段;设计建造阶段8.酒店投资的非系统风险不包括()参考答案:经济风险;市场风险9.酒店投资是一种实物投资,下列哪项描述是正确的的()参考答案:最大投资在其建设期;投资周期长;期望收益高10.下列哪个地方属于酒店的创利面积()参考答案:酒店大堂;酒店餐厅;酒店客房第三章测试1.针对负需求而言,当某地区顾客不需要某种餐饮产品时,餐饮管理人员采取措施,扭转这种趋势称为参考答案:扭转式营销2.菜肴销售分析是通过()和()指数进行参考答案:顾客满意和销售额3.影响餐饮产品的价格因素不包括参考答案:地域4.顾客满意程度高,营业收入水平高的菜品属于参考答案:明星5.以下应该删除的菜品是参考答案:销售额小于 1,顾客满意指数小于 16.以下业务能力属于餐饮部门高层管理能力的范围的是参考答案:市场营销策划;菜单设计与定价;目标预算制定7.企业地理位置、交通条件和就餐环境均属于餐饮部门的可控因素参考答案:错8.餐饮部门是五星级酒店中带来收益最高的部门。

德国法学教育经典案例之"特里尔葡萄酒拍卖案"学习过德国法律的人,那怕只是出去个人兴趣偶尔旁听或纯为辅修学分,应该无人不知这个著名的“特里尔葡萄酒拍卖案”(Trierer Weinversteigerungsfall)。

在几乎所有关于民法基础的德语教科书中,均可看到这个案例。

此案例事实之简单、设计之精妙、内涵之深厚,着实令人感叹!事实上,这个所谓的“案例”并未在现实生活中发生过,而是一个完全虚构的案例。

1899年,Hermann Isay在其著作《法律行为构成之意思表示》(Die Willenserklärung im Tatbestande des Rechtsgeschäfts)一书中首次提到其设计的这一虚构案例。

此时,他正在德国特里尔市(即马克思故乡,该地区盛产德国著名的白葡萄酒)担任候补文官。

从此,该案例被法律界广泛讨论并在德国法学教材中沿用至今。

此案例精妙之一即为事实经过非常简单,寥寥几字足以描述:一个对特里尔市并不熟悉的A先生,进入到一个葡萄酒拍卖会现场。

当他看到自己认识的 B先生时,便向他招手示意。

拍卖师抬头一看有人举手,直接落锤,将拍卖的葡萄酒拍给了A。

问题,A是否拍得该批葡萄酒并因此需要支付价款?如此简单的一个事实,为何会引起德国法律界的广泛讨论并作为经典案例沿用至今呢?这恰恰是该案例设计精妙之处。

对于举手之一动作如何理解和解释,正好可以用来阐释意思表示这一法学里最基本的概念。

要解答上面提到的问题,首先要简单解释下德国法对意思表示构成的理论解释。

对于意思表示这一抽象概念,德国法学界却像剖析一个实体一样,对其构成要件进行了分割,给人感觉就像在看医生拿着手术刀在解剖一只小白鼠,或是一个小朋友在一层层剥吃一个夹心蛋糕。

德国法学理论认为,一个完整的意思表示,由内在意思(主观要件)和外在表示(客观要件)构成。

而内在意思,则又由三层意志构成,即行动意志(Handlungswille),表示意志(Erklärungswille)和行为意志(Geschäftswille)。

德国葡萄酒酒标常见词汇Q.b.A :是Qualitatswein bestimmter Anbaugebiete的简写,指优质葡萄酒Q.m.P:是Qualitatswein mit Praikat的简写,指著名产地优质酒Kabinet:指一般的葡萄酒Spatlese:指晚摘葡萄酒Auslese:指贵族霉葡萄酒Beerenauslese:指精选贵族霉葡萄酒Trockenbeerenauslese:指精选干颗粒贵族霉葡萄酒Eiswein:冰葡萄酒Qualitatswein:指著名产地监制葡萄酒Tafelwein:指日常餐酒,相当于法国的VDTLandwein:指地区乡土葡萄酒,德国普通佐餐酒,等同于法国VDP级别Abfuler:装瓶者Anreichern:增甜Erzeugerabfullung:酿酒者装瓶Halbtrocken:微甜Herb:微酸Heuriger:当令酒,类似新酒Jahrgang:年份Jungwein:新酒Sekt:气酒Trocken:不甜(与Herb所指不同)地名+er:表示“~ 的”或“来自”的意思,例如“Kallstadter Saumagen”即表示,该酒产自位于Kallstadter 村庄,名叫Saumagen的葡萄园AP Nr (AP Number) :德国较高品质葡萄酒(QbA或QmP级葡萄酒)的酒标上均有此系列数字的标注,是Amptliche Prüfungsnummer 的缩写,表示该酒通过了标准的检测与分析。

通常90%的酒都可通过该检查,所以并不能确切反映葡萄酒品质的差异。

Blauburgunder:德语对黑比诺(Pinot Noir)葡萄品种的称呼也可称为Spätburgunder。

Bleichert :德语指桃红葡萄酒(Rosé)。

Edelfäule:德语指贵腐病(Noble rot)。

Erste Lage:由德国葡萄种植者协会(VDP)制定的德国葡萄园分级里的最高等级,相当于法国的一级葡萄园(Grand Cru 或First growth),但该词汇一般只在莫舍尔(Mosel)产区使用。

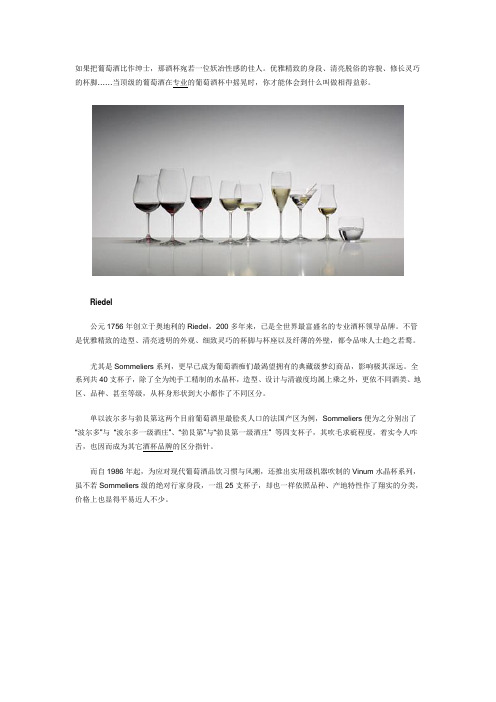

如果把葡萄酒比作绅士,那酒杯宛若一位妖冶性感的佳人。

优雅精致的身段、清亮脱俗的容貌、修长灵巧的杯脚……当顶级的葡萄酒在专业的葡萄酒杯中摇晃时,你才能体会到什么叫做相得益彰。

Riedel公元1756年创立于奥地利的Riedel,200多年来,已是全世界最富盛名的专业酒杯领导品牌。

不管是优雅精致的造型、清亮透明的外观、细致灵巧的杯脚与杯座以及纤薄的外壁,都令品味人士趋之若鹜。

尤其是Sommeliers系列,更早已成为葡萄酒痴们最渴望拥有的典藏级梦幻商品,影响极其深远。

全系列共40支杯子,除了全为纯手工精制的水晶杯,造型、设计与清澈度均属上乘之外,更依不同酒类、地区、品种、甚至等级,从杯身形状到大小都作了不同区分。

单以波尔多与勃艮第这两个目前葡萄酒里最脍炙人口的法国产区为例,Sommeliers便为之分别出了“波尔多”与“波尔多一级酒庄”、“勃艮第”与“勃艮第一级酒庄” 等四支杯子,其吹毛求疵程度,着实令人咋舌,也因而成为其它酒杯品牌的区分指针。

而自1986年起,为应对现代葡萄酒品饮习惯与风潮,还推出实用级机器吹制的Vinum水晶杯系列,虽不若Sommeliers级的绝对行家身段,一组25支杯子,却也一样依照品种、产地特性作了翔实的分类,价格上也显得平易近人不少。

Zwiesel Kristallglas AG德国赫赫有名的专业玻璃与水晶集团Zwiesel Kristallglas AG,旗下分为以机器吹制杯品为主的Schott Zwiesel,以及以手工吹制杯品为主的Zwiesel 1872两大品牌。

产品最大特色在于杯壁轻薄、表面透明光滑、且质地坚固耐用。

尤其号称配方中含有一种独特的氧化钛成分,使玻璃本身特别有韧性,据说即使连最精细的手工吹制杯品,也可经得起洗碗机的洗涤,与一般公认需得小心呵护以免破损的Riedel恰成鲜明对照。

最知名、杯型品项最齐全的分别为Zwiesel 1872旗下的Enoteca、Schott Zwiesel旗下的Diva两系列。

葡萄酒用于连续生产酒心巧克力消费税计算简介葡萄酒作为一种高级酒类产品,广泛用于酒心巧克力的制造中。

在许多国家和地区,对葡萄酒的销售征收消费税,以增加政府的税收收入。

在这篇文章中,我们将探讨葡萄酒计入酒心巧克力生产的消费税如何计算。

消费税简介消费税是一种对消费品征收的税收,它根据产品的价格或数量来计算。

消费税的目的是增加政府的税收收入,并在其中一种程度上对商品进行调控。

不同国家和地区对不同类别的商品征收不同税率的消费税。

连续生产酒心巧克力酒心巧克力是一种以巧克力为外层,内部填充葡萄酒酒心的糖果。

在连续生产酒心巧克力的过程中,葡萄酒将作为一种原材料使用。

因此,根据不同国家和地区的法律法规,对葡萄酒的消费税计算方法会有所不同。

计算方法在大多数国家和地区,葡萄酒的消费税征收方式主要有两种:按照葡萄酒的价格征税和按照葡萄酒的酒精度数征税。

按照葡萄酒的价格征税在这种方式下,葡萄酒的销售价格将作为计算消费税的依据。

具体计算公式可能因国家和地区的不同而有所差异。

一般情况下,消费税的计算公式如下:消费税=销售价格×税率例如,假设国家对葡萄酒征收10%的消费税,而葡萄酒的销售价格为每瓶50美元。

那么消费税的计算公式将为:消费税=50美元×10%=5美元这意味着每瓶葡萄酒的消费税为5美元。

按照葡萄酒的酒精度数征税在这种方式下,葡萄酒的酒精度数将作为计算消费税的依据。

酒精度数一般使用百分数表示,表示葡萄酒中酒精的含量。

具体的计算方法因国家和地区的不同而有所差异。

消费税=酒精度数×定额税率例如,假设国家对葡萄酒按照每度酒精征收2美元的消费税,而葡萄酒的酒精度数为13%。

那么消费税的计算公式将为:消费税=13%×2美元=0.26美元这意味着每瓶葡萄酒的消费税为0.26美元。

不同国家和地区对葡萄酒计入酒心巧克力生产的消费税计算方法可能有所不同。

因此,在实际操作中,需要根据当地的法律法规和相关规定来确定具体的计算方法。

Wine Searcher全球最贵的50款葡萄酒排名2013年中版完整列表:(1-10)排名酒款平均价(美元) 最高价(美元)产区1、Henri Jayer Richebourg Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 16,193 24,473 勃艮第夜丘2、Domaine de la Romanee-Conti Romanee-Conti Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 12,527 62,507 勃艮第夜丘3、Egon Muller-Scharzhof Scharzhofberger Riesling Trockenbeerenauslese, Mosel, Germany 6,934 14,125 德国莫泽尔4、Henri Jayer Cros Parantoux, Vosne-Romanee Premier Cru, France 6,127 19,632 勃艮第夜丘5、Domaine Leflaive Montrachet Grand Cru, Cote de Beaune, France 5,807 11,545 勃艮第伯恩丘6、Joh. Jos. Prum Wehlener Sonnenuhr Riesling Trockenbeerenauslese, Mosel, Germany 5,329 11,392 德国莫泽尔7、Domaine Georges & Christophe Roumier Musigny Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 4,692 16,067 勃艮第夜丘8、Domaine de la Romanee-Conti Montrachet Grand Cru, Cote de Beaune, France 4,672 13,695 勃艮第夜丘9、Domaine Leroy Musigny Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 4,376 33,740 勃艮第夜丘10、Henri Jayer Vosne-Romanee, Cote de Nuits, France 3,572 9,410 勃艮第夜丘11、Georges et Henri Jayer Echezeaux Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 3,396 11,914 勃艮第夜丘12、Petrus, Pomerol, France 2,985 35,949 波尔多波美侯13、Domaine Jean-Louis Chave Ermitage Cuvee Cathelin, Rhone, France 2,877 6,119 罗纳河谷埃米塔日14、Domaine Leroy Chambertin Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 2,837 33,740 勃艮第夜丘15、Domaine de la Romanee-Conti La Tache Grand Cru Monopole, Cote de Nuits, France 2,798 26,000 勃艮第夜丘16、Le Pin, Pomerol, France 2,604 21,946 波尔多波美侯17、Screaming Eagle Cabernet Sauvignon, Napa Valley, USA 2,532 13,511 美国纳帕谷18、Domaine du Comte Liger-Belair La Romanee Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 2,350 4,597 勃艮第夜丘19、J.-F Coche-Dury Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru, Cote de Beaune, France 2,300 5,687 勃艮第伯恩丘20、Domaine Faiveley Musigny Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 2,281 10,990 勃艮第夜丘21、Domaine Leroy Mazis-Chambertin Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 2,144 32,054 勃艮第夜丘22、Domaine Leroy Richebourg Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 2,127 7,488 勃艮第夜丘23、Domaine Leroy Grands-Echezeaux Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,945 5,004 勃艮第夜丘24、Domaine de la Romanee-Conti Richebourg Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,763 23,500 勃艮第夜丘25、Lalou Bize-Leroy Domaine d’Auvenay Chevalier-Montrachet Grand Cru, Cote de Beaune, France 1,763 3,791 勃艮第伯恩丘26、Domaine Dugat-Py Chambertin Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,636 3,725 勃艮第夜丘27、Joh. Jos. Prum Wehlener Sonnenuhr Riesling Beerenauslese, Mosel, Germany 1,533 3,748 德国莫泽尔28、Domaine Leroy Romanee-Saint-Vivant Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,513 4,270 勃艮第夜丘29、Domaine Leroy Echezeaux Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,496 30,366 勃艮第夜丘30、Domaine des Comtes Lafon Montrachet Grand Cru, Cote de Beaune, France 1,455 4,958 勃艮第伯恩丘31、Domaine Meo-Camuzet Au Cros Parantoux, Vosne-Romanee Premier Cru, France 1,431 3,330 勃艮第夜丘32、Lalou Bize-L eroy Domaine d’Auvenay Mazis-Chambertin Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,423 2,680 勃艮第夜丘33、Domaine Leroy Clos de la Roche Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,411 6,995 勃艮第夜丘34、Lalou Bize-Leroy Domaine d’Auvenay Les Bonnes-Mares Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,376 2,374 勃艮第夜丘35、J.-F Coche-Dury Les Perrieres, Meursault Premier Cru, France 1,367 2,993 勃艮第伯恩丘36、Domaine Ramonet Montrachet Grand Cru, Cote de Beaune, France 1,358 4,951 勃艮第伯恩丘37、Domaine Georges & Christophe Roumier Les Amoureuses, Chambolle-Musigny Premier Cru, France 1,335 8,071 勃艮第夜丘38、Domaine de la Romanee-Conti Romanee-Saint-Vivant Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,281 54,000 勃艮第夜丘39、Emmanuel Rouget Cros Parantoux, Vosne-Romanee Premier Cru, France 1,264 2,794 勃艮第夜丘40、Domaine Leroy Latricieres-Chambertin Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,261 4,841 勃艮第夜丘41、Domaine de la Romanee-Conti Grands Echezeaux Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,241 6,204 勃艮第夜丘42、Moet & Chandon Dom Perignon Oenotheque Rose, Champagne, France 1,241 2,021 香槟43、Domaine Meo-Camuzet Richebourg Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,215 4,198 勃艮第夜丘44、Domaines Barons de Rothschild Chateau Lafite Rothschild, Pauillac, France 1,209 135,299 波尔多波亚克45、Quinta do Noval Nacional Vintage Port, Portugal 1,155 8,645 葡萄牙波特46、Schloss Johannisberg Goldlack Riesling Trockenbeerenauslese, Rheingau, Germany 1,144 3,215 德国莱茵高47、Joh. Jos. Prum Wehlener Sonnenuhr Riesling Auslese Lange Goldkapsel, Mosel, Germany 1,109 2,023 德国莫泽尔48、Domaine J-F Mugnier Le Musigny Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,106 3,099 勃艮第夜丘49、Domaine Armand Rousseau Pere et Fils Chambertin Grand Cru, Cote de Nuits, France 1,103 9,962 勃艮第夜丘50、Krug Clos du Mesnil Blanc de Blancs Brut, Champagne, France 1,088 6,118 香槟。

葡萄酒的发展历史英语作文The history of wine dates back thousands of years, with evidence of its production and consumption found in ancient civilizations such as the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans.Wine has always been a symbol of luxury and sophistication, enjoyed by royalty and the upper class throughout history. It was often used in religious ceremonies and celebrations, highlighting its cultural significance.The invention of the cork in the 17th century revolutionized the wine industry, allowing for better preservation and aging of wines. This led to the development of different grape varieties and winemaking techniques, resulting in a wider range of wine styles and flavors.In the 19th century, the phylloxera epidemic devastated vineyards across Europe, leading to the replanting of vineswith disease-resistant rootstocks. This event profoundly impacted the global wine industry and shaped the way wines are produced today.The 20th century saw the rise of New World wine regions such as California, Australia, and South Africa, challenging the dominance of traditional wine-producing countries like France and Italy. This diversification of wine sources introduced consumers to new grape varieties and styles, expanding their palates.Today, the wine industry continues to evolve with advancements in technology, sustainability practices, and changing consumer preferences. From natural wines to biodynamic farming, the focus on quality and innovation drives the development of new trends and movements within the wine world.。

Agrarwirtschaft 52 (2003), Heft 5A Hedonic Pricing Model for German Wine Ein hedonisches Preismodell für Qualitätswein aus DeutschlandGünter Schamel* Humboldt-Universität zu BerlinZusammenfassungWir erstellen ein hedonisches Preismodell für Qualitätswein aus Deutschland. Als Indikatoren der Qualität von 4,141 Weinen dienen die Ergebnisse der sensorischen Prüfung der jährlichen Bundesweinprämierung und die Einstufung in die gesetzlichen Qualitätskategorien sowie eine Reihe von Kontrollvariablen wie z.B. regionale Herkunft, Weinart, Geschmacksrichtung oder das Alter der Weine zum Zeitpunkt der sensorischen Prüfung. Die Datengrundlage bestätigt, dass die Ergebnisse der Prämierung sowie die Qualitätsstufen und die meisten der Kontrollvariablen einen signifikanten Einfluss auf den Preis haben.SchlüsselwörterWein, hedonische Preismodelle, ReputationAbstractWe develop a hedonic pricing model for German quality wine. Quality indicators for 4,141 wines are sensory awards received at the annual German wine competition and the legally required quality category as well as a set of control variables including regional origin, color, style, and their age at the time of judging. The data confirms that sensory quality awards have a significant and positive price impact. Moreover, we estimate significant relative differences between quality categories, growing regions and most of the control variables.determine the criteria and method of assessment necessary to meet local (and EU) quality standards. In some countries, wine quality is closely tied to origin; i.e. the system is based on given conditions. Quality standards vary considerably, depending on appellation of origin, and the qualitative assessment is usually determined by regional wine trade organizations. However, in Germany quality is confirmed or denied by official testing. The quality in the glass rather than origin counts. The standards are largely uniform and the assessment is determined through quality control testing. Regulations governing quality categories and testing are important components of the German wine law. Germany is the world’s sixth largest wine producer with a total production of about ten million hectoliters. German wine is grown in 13 classified regions and renowned for its white varieties such as Riesling and Müller-Thurgau. Table 1 provides an overview of production by growing region. Vineyard area and production quantity remained relatively steady over the last decade. However, there have been significant structural changes (DWI, 2001). In particular, the proportion of red variety vineyards has grown from 16% to over 26%. Mass producing white varieties are now declining and the production increasingly focuses on premium quality wine (STORCHMANN and SCHAMEL, 2002).Key wordswine, hedonic pricing models, reputationTable 1. Vineyard area and production in Germany in 2000Region Ahr Baden Franken Hess. Bergstraße Mittelrhein Mosel-Saar-Ruwer Nahe Pfalz Rheingau Rheinhessen Saale-Unstrut Sachsen Württemberg Total Vineyards (ha) 513 15,372 5,925 443 540 11,042 4,428 22,606 3,144 25,596 621 415 10,903 101,548 Production (1,000 hl) 45.6 1,225.4 479.5 41.9 45.0 1,127.6 361.4 2,610.5 275.1 2,606.1 42.2 23.2 1,197.2 10,080.8 Main Varieties Pinot Noir Pinot Noir, Müller-Thurgau Müller-Thurgau, Sylvaner Riesling Riesling Riesling Riesling Riesling, Müller-Thurgau Riesling Müller-Thurgau, Sylvaner Müller-Thurgau, Pinot Blanc Müller-Thurgau, Riesling Trollinger, Riesling Riesling, Müller-Thurgau1. IntroductionBecause any expert appraisal of sensory wine quality is based on subjective impressions, wine is also classified according to legally binding criteria and standards that are measurable and verifiable. Such a notion of “quality” is outlined in wine laws and regulations. The EU wine law assigns general conditions that apply to all wine-producing member states, but takes common interests as well as national differences into account. For example, the vineyard areas in the EU are Source: DWI (2001) divided into climatic zones to help compensate for the climatic variations that influence wine pro- In this paper, we analyze an extensive data set of 4,141 duction. Similarly, the EU wine law defines quality catego- wines evaluated during the annual competitions adminisries that enable legally equivalent comparisons among tered by the German Agricultural Society (DLG). The hemember states. However, each member state is permitted to donic model includes award level (bronze, silver, gold, gold*Thanks are due to two anonymous referees for many helpful comments and suggestions as well as the German Agricultural Society (Deutsche Landwirtschaftsgesellschaft - DLG) for kindly providing their extensive data set. An earlier draft of this paper was presented at the Colloque Oenometrie IX in Montpellier, France, May 31 – June 1, 2002.247Agrarwirtschaft 52 (2003), Heft 5extra), wine style (dry, off-dry, mild), barrique aging, color (red, white, rosé), special quality attributes (e.g. Spätlese, Auslese), and regional origin (e.g. Baden, Pfalz) as independent variables to explain variations in price. We show that the estimated implicit prices for these quality characteristics are highly significant (except for one regional indicator and rosés) and that they exhibit expected signs and relative magnitudes. The price premiums for special quality attributes are significantly larger than the premiums for competition awards. Moreover, the smaller wine growing regions (e.g. Ahr, Saxony) receive high price premiums relative to the larger bulk producing regions.method of harvesting, and marketing. In ascending order of ripeness at harvest the special attribute categories are: · Kabinett: fine, usually “naturally” light wines made of fully ripened grapes, low in alcohol, may not be sold prior to January following the harvest. Spätlese: late harvest, from superior quality grapes, more intense in flavor and concentration than Kabinett, not necessarily sweet. Auslese: from selected, very ripe bunches, noble wines with intense in bouquet and taste, usually, but not always sweet. Beerenauslese (BA): from selected, overripe berries (usually Botrytis), harvested only during exceptional weather conditions, yielding rich, sweet dessert wines noted for their longevity. Eiswein: from grapes as ripe as BA, but harvested and pressed while frozen, unique wines with a remarkable concentration of fruit, acidity, and sweetness.··2. Regulations and quality controlBy law, German wines are categorized by the degree of ripeness, which the grapes have achieved at harvest. Ripeness is determined by the sugar content in the grapes measured in degree Oechsle. The Oechsle requirements for the respective categories vary by growing region. They do not reflect sweetness levels in the finished wine. Riper grapes provide more aroma and more flavor, hence a more expressive and flavorful wine. Sweetness depends on the winemaker’s decision and is independent of wine quality. If the fermentation process, which converts natural sugar into alcohol, stops or is interrupted before all sugar is transformed, it will result in sweeter wines. If the fermentation continues until little or no sugar is left, it results in drier wines. Grapes for dessert wines have so much natural sugar that they will not ferment completely and residual sugar (sweetness) will remain. German wine producers are required to declare specific quality categories on their labels. The European Union wine law mandates two broad quality categories: Table Wine and Quality Wine. Within these quality categories, the German wine law specifies more sub-categories than other EU countries. For example, the table wine category has two levels: simple table wines (Deutscher Tafelwein) and superior table wines (Deutscher Landwein). However, we will not further elaborate on table wines because of our focus on quality wines in this paper. Standard quality wine (Qualitätswein - QbA) must be made exclusively from German produce, be from an approved grape variety grown in one of the 13 specified winegrowing regions, and reach an existing alcohol content of at least 7% by volume. However, winemakers are allowed to add sugar to QbA wines before fermentation to increase the alcohol level of the wine. This so-called chaptalization process is commonly used around the world and adds more body to otherwise lighter wines. The quality wine category has six higher-rated sub1 categories identified by special quality attributes (QmP). QmP must be from a certain district within a wine-growing region and reach a specified natural alcohol content for the region, grape variety and special attribute category. Chaptalization is not allowed. The special attribute categories are subject to additional regulations concerning ripeness,1···QbA = Qualitätswein bestimmter Anbaugebiete (quality wine from a specified appellation) QmP = Qualitätswein mit Prädikat (quality wine with special attributes).Trockenbeerenauslese (TBA): from individually selected, overripe berries (dried up almost to raisins); rare, rich, lusciously sweet wines with an extraordinary longevity. Moreover, note that all special attribute categories except “Kabinett” wines may not be sold before the month of March following the year of harvest and that BA and TBA wines may not be harvested mechanically. The German wine law also defines four basic wine styles (dry, off-dry, mild, sweet) in terms of their dryness or sweetness. Dry (“trocken”) indicates that most of the natural sugar has been fermented (up to 9 grams/liter of residual sugar, total acidity must be 2 grams/liter less than residual sugar content). Off-dry (“halbtrocken”) includes wines with 9-18 grams/liter of residual sugar and total acidity must be 10 grams/liter less than the residual sugar. Mild wine (“lieblich”) has a residual sugar content between 18 and 45 grams/liter. Sweet wines (“süß”) have more than 45 grams/liter of residual sugar. The wine regulations have been subject to much criticism since becoming law in 1971. For example, there are no yield limits, which have increased without enough regard for quality. Another problem is that sugar content at harvest is the only criteria for inclusion into a quality category although the boundaries between sub-categories (e.g. Spätlese or Auslese) are adjusted by region. Thus, a higher sugar content is required for wines from warmer regions (e.g. Baden) relative to the cooler areas (e.g. Nahe). However, the required sugar levels for higher-rated categories are generous. Moreover, some producers declassify wines reasoning that it is better to offer an excellent QbA rather than a mediocre Kabinett. Concurrently to the new wine law coming into force, modern early-ripening varieties came into production. Whereas previously a wine labeled “Auslese” indicated a highly selective harvest in the vineyard and correspondingly high quality, it now became much easier to produce a high-sugar content “Auslese” from Ortega grapes. Moreover, it became perfectly legal to blend Riesling Auslese with a modern early-ripening variety or to chaptalize a QbA but not a QmP such that the former was not necessarily inferior to the248Agrarwirtschaft 52 (2003), Heft 5latter. The potential for abuse became immense and the fine name that once attached to ‘Auslese’ was degraded. Many producers acknowledge the inadequacy of the wine law, but the main regulatory and marketing bodies have resisted any reforms. As a consequence, leading German estates have formed associations such as the “Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter” (VDP) in an effort to change the system and demand far stricter quality controls than the current wine law. Many estates have imposed strong self-regulation, ensuring that anything offered to consumers under their label is of good quality. Despite the failings of the wine law, the DLG administers a sound system of wine quality control, which we will analyze subsequently. Each German wine, which is labeled as a “quality wine” first undergoes a critical, blind, sensory testing procedure based on a uniform five-point scale, devised by the DLG. For each wine to be tested, producers have to submit an application for an official quality control test number (A.P.Nr.)2. The actual examination procedure is divided into two rounds: (a) checking specific prerequisites and (b) examining a wine’s sensory characteristics. In the first round, the examination panel verifies whether the wine is typical for the region of origin, grape variety and quality category stated on the application. Just one negative score on any of these questions disqualifies a wine from further assessment. Subsequently, the second round is a sensory evaluation of three important characteristics: bouquet, taste and harmony. “Harmony” embraces all sensory impressions, including color. The overall balance between sweetness and acidity as well as alcohol and body are also considered. Up to five points or fractions thereof are awarded for each of the three characteristics. A minimum of 1.5 points (per characteristic) is necessary to avoid rejection. The total sum of this characteristic score yields an overall evaluation that is divided by three to determine the wine’s quality rating number - the wine must achieve at least 1.5 points in order to receive a quality control test number (A.P.Nr.). The DLG and its regional associations use the same testing procedure and “five-point system” to determine wines of superior quality, which are worthy of seals, award medals and prizes. In order to qualify for the German Wine Seal (Deutsches Weinsiegel), a wine must achieve at least 2.5 points, i.e. achieve a significantly higher quality rating than required to simply receive a quality control test number (A.P.Nr.). The German Wine Seal also indicates wine styles using a color-coding system. Dry wines bear a bright yellow seal; a lime green seals identifies off-dry wines; and the red seal is reserved for sweeter wines. State Chambers of Agriculture (Landwirtschaftskammern) award bronze, silver and gold medals that require a minimum of 3.5, 4, and 4.5 points, respectively. These medalwinning wines are then eligible to enter the annual national wine competition (Bundesweinprämierung) administered by the DLG at which they can win bronze, silver and gold awards (DLG-Prizes). In a special competition, the Gold Extra Prize (Goldener Preis Extra) may be awarded to wines that achieve a perfect 5-point score. For consumers, wine seals, medals and DLG awards are valuable guides to2assess the quality of German wine. In the next section, we briefly review the literature on hedonic price analysis specifically as related to wine quality indicators.3. Literature reviewA number of studies apply hedonic models to estimate implicit prices for wine quality attributes. They are based on the hypothesis that any good represents a bundle of characteristics that define quality. Theoretical foundation is the seminal paper by ROSEN (1974), which posits that goods are valued for their utility-generating attributes. ROSEN hypothesizes that consumers evaluate these attributes when making a purchasing decision. The competitive market price is the sum of implicit prices paid for embodied product attributes. Rosen recognizes an identification problem for supply and demand functions derived from hedonic models, because implicit prices are equilibrium prices jointly determined by supply and demand conditions. Thus, implicit prices may not only reflect consumer preferences but also factors determined through production. In order to solve the identification problem it is necessary to separate supply and demand conditions. ARGUEA and HSIAO (1993) argue that the identification problem is essentially a data issue that can be avoided by pooling crosssection and time-series data specific to a particular side of the market. In this paper, we chose not model the supply side, because we assume a market equilibrium. That is, all consumers have made their utility-maximizing choices, given their knowledge of prices, characteristics of alternative wines and other goods. When making their buying decision, they use available information on how experts evaluate a particular wine and how the growing region succeeds a supplier of quality wine. Moreover, all firms have made their profit-maximizing decisions given their production technologies and the costs of alternative wine qualities producible, and that the resulting prices and quantities clear the market. According to FREEMAN (1992), the equilibrium assumption implies that implicit prices may be specified without separately modeling supply conditions. SHAPIRO (1983) presents a theoretical framework to examine the effects of producer reputation on prices, assuming competitive markets and imperfect information. For consumers, it is costly to improve their knowledge about quality. He demonstrates that reputation allows high-quality producers to sell their items at a premium which may be interpreted as return on investments in reputation building. In an imperfect information environment, learning about reputation indicators may be an effective way for consumers to reduce their decision-making costs. Since the quality of a bottle of wine is unknown until it is de-corked, reputation indicators associated with it will affect consumer willingness to pay. TIROLE (1996) presents a model of collective reputation as an aggregate of individual reputations where current producer incentives are affected by their own actions as well as collective actions of the past. He derives the existence of stereotype producers from history dependence, shows that new producers may suffer from past mistakes of older producers for a long time after the latter disappear, and derives conditions under which the collective reputation can be regained. GOLAN and SHALIT (1993) identify and evaluate quality characteristic applying he-A.P.Nr. = Amtliche Prüfnummer249Agrarwirtschaft 52 (2003), Heft 5donic pricing to wine grapes sold in Israel. Thus, they study quality differentiation. For New Zealand, regional quality the input supply side of the wine market. They propose that differentiation is also significant, although less than in high-quality wines are produced only when growers are Australia. given strong price incentives to supply better grapes. In a SCHAMEL (2000) estimates a hedonic model for the U.S. two-stage model, they first develop a quality index by market with sensory quality ratings for a white and a red evaluating the (relative) contributions of various physical variety (Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay) from seven grape attributes to wine quality. Second, they construct a different wine-growing regions. The estimated price elasquality-price function relating the price of Californian wine ticity of sensory quality is larger for white wine, indicating to the quality index developed in the first stage. NERLOVE that consumers were willing to pay a higher quality pre(1995) examines the Swedish wine market having no do- mium for white compared to red wine. However, the results mestic production, a small share of global consumption, suggest both regional reputation and individual quality and government controlled prices. He assumes that wine indicators seem to be more important to U.S. consumers of consumers express their valuation for a particular quality red wine. The results also suggest the public-good value of attribute by varying the derived hedonic demand for it and a regional appellation is higher for red wine regions and estimates a reduced form hedonic price function, regressing that individual producers in those regions may benefit more sold quantities on quality attributes and prices. COMBRIS et from collective marketing efforts. In another paper, al. (1997) estimate a hedonic price equation and what is SCHAMEL (2002) argues that as quality indicators improve referred to as a jury grade equation for Bordeaux wine to over time, spillovers will affect other producers within a explain the variations in price and quality, respectively. region. Quality indicators for premium California wine are LANDON and SMITH (1997, 1998) present further empirical medals awarded during nine annual wine competitions, analyses of Bordeaux wine, focusing on reputation indicators variety, regional origin, judging age as well as derived in addition to sensory quality attributes. In both papers, they producer (brand) and regional reputation indicators. Estistudy the impact of current quality as well as reputation indi- mating a hedonic model, the data confirms that a wine’s cators on consumer behavior using hedonic price functions. price is significantly related to its own quality as well as to Lagged sensory quality ratings define individual product historically accumulated producer and regional reputation reputation. Regional reputation indicators are government indicators for quality. and industry classifications. Their main findings are: reputation indicators have a large impact on consumer willingness 4. Data and analysis to pay, an established reputation is considerably more important than short-term quality improvements, and ignoring We analyze quality indicators for German wine admitted to reputation indicators will overstate the impact of current the annual national wine competition (Bundesweinquality on consumer behavior. The 1997 paper analyzes five prämierung). The results of the competition are published in vintages individually (1987-91) and the estimated coeffi- print and via the Internet (DLG, 2001). The original data set cients vary substantially across these vintages. extracted from the Internet consisted of 4,281 observations. OCZKOWSKI (1994) estimates hedonic price function for The sample size used for the estimation procedure was premium Australian wines, examining six attribute groups reduced to 4,141 because 140 wines listed no price inforand various interaction terms. In another paper, he argues mation. However, for most wines, producers state a retail that single indicators of wine quality and reputation are price per bottle on the submission form before entering the imperfect measures because tasters’ evaluations differ and competition. Therefore, the price information is prethus contain measurement errors. Employing factor analysis competition and does not reflect any direct effects from and 2SLS, he finds significant reputation effects but insig- awarded medals. Table 2 presents the distribution of medals (Bronze, Silver, Gold, and Gold Extra) by growing region. nificant quality effects (OCZKOWSKI, 2001). ROBERTS and REAGANS (2001) examine market experience, Overall, 19.5% of all medals awarded are Bronze, 36.5% consumer attention, and price-quality relationTable 2. Distribution of medal winners by region ships for New World wines in the U.S. They argue that producer or regional quality signals Region Bronze Silver Gold Gold Extra All improve with the duration of market exposure Ahr 0.5% 1.1% 1.3% 1.3% 1.1% and evaluation. Controlling for vintage, blindBaden 5.7% 11.5% 17.6% 23.1% 13.2% tasted quality, and variety, BROOKS (2001) apFranken 11.0% 9.5% 9.9% 1.3% 9.8% plies hedonic price analysis to study the effect of Hess. Bergstraße 1.3% 1.6% 2.2% 2.5% 1.8% country-of-origin brands on international comMittelrhein 1.3% 2.9% 1.8% 1.3% 2.1% petitiveness. Comparing price residuals acrossMosel-Saar-Ruwer 18.8% 9.8% 5.1% 2.6% 9.4% countries suggests that international brands can Nahe 3.6% 3.7% 3.0% 1.3% 3.4% affect a wine bottle’s price in excess of fifty Pfalz 22.6% 19.1% 19.9% 26.9% 20.2% percent. SCHAMEL and ANDERSON (2003) evaluRheingau 5.3% 4.2% 3.0% 2.5% 3.9% ate wine quality and regional reputation indicaRheinhessen 18.2% 14.6% 14.4% 16.7% 15.2% tors for Australia and New Zealand. In each country, price premiums associated with sensory Saale-Unstrut 0.9% 1.0% 0.4% 0.0% 0.7% quality ratings, and winery ratings are highly Sachsen 2.0% 1.2% 0.4% 0.0% 1.0% significant. For Australia, regional reputations in Württemberg 8.8% 19.8% 21.1% 20.5% 18.2% general are becoming increasingly significant Source: DLG (2001), own calculations through time, indicating intensifying regional 250Agrarwirtschaft 52 (2003), Heft 5are Silver, 42.1% are Gold and 1.9% are Gold Extra. The model employs dummy variables for the medals as an indicator of sensory quality in addition to the quality attributes (e.g. Spätlese, Auslese) ensuing from the wine law. The data set also denotes wine style, color, regional origin, age at the time of judging, and whether or not the wine was aged in barrique (oak barrels). Table 3 lists the independent variables used in the model. All independent variables are categorical dummies, except for judging age and Barrique (regular dummy). The dependent variable in the model is the logarithm of the retail price [log(Price)]. Table 3. Description of independent variables3that the price of a particular wine i (Pi) as a function of its characteristics zj: (1)Pi = Pi ( z i1 , ..., z ij , ..., zin )We employ a log-linear function for the estimation. Following OCZKOWSKI (1994), we used a RESET test which rejected other functional forms (i.e. inverse, linear).5 Thus, we estimate the following multivariate regression model: (2) log(Pi) = α + β1 Di Award + β2 Di Quality level + β3 Di Style + β4 Di Color + β5 Di Region + γAgei + δBari + εiwhere log(Pi) is the logarithm of the retail price Pi and the error term εi is distributed identically Variable Parameters and independently with a zero mean and uniform Award Gold Extra, GOLD*, Silver, Bronze variance. Given the functional form and the nature of the categorical dummies for award, qualQuality Qualitätswein (QbA), Kabinett, SPÄTLESE*, Auslese, ity level, style, color and region (Di), the estimaLevel Beerenauslese (BA), Trockenbeerenauslese (TBA), Eiswein tion of equation (2) yields price premiums and Wine Style lieblich/mild, halbtrocken, TROCKEN*, Barrique discounts βi (i =1, ... 5) relative to the contribuColor Weißwein, Rosé, ROTWEIN* tion of the base category (Gold, dry, white Spätlese from the Pfalz region). Specifically, β1 is Regions Ahr, Baden, Franken, Hessische Bergstraße, Mittelrhein, Mosel-Saar-Ruwer, Nahe, PFALZ*, Rheingau, the coefficient for the medal received, β2 for the Rheinhessen, Saale-Unstrut, Sachsen, Württemberg quality attribute, β3 for wine style, β4 for color, and β5 for regional origin. The coefficients γ and Age 1 – 5 Years δ measure the price premiums paid for older * Parameters in BOLD are chosen as base category. wines and barrique-aged wine, respectively. AcSource: own description. cording to HALVORSEN and PALMQUIST (1980), In table 4, we summarize frequencies and price statistics appropriate adjustments are to be made to interpret the differentiating the four prize levels, seven quality catego- estimated dummy coefficients as percentage premiums or ries, wine style, color as well as the 13 classified wine re- discounts. gions. Over 42% of the sample were awarded the DLG Gold prize and more than a third of the sample was catego- 5. Estimation results rized “Spätlese.” Moreover, it contains about 68% white wine, 29.5% red wine, and 2.5% rosé. The average nominal Table 5 lists the regression results for the model defined in 4 price is 8.96 € (range 2.05€ – 184 €). For the estimation, equation (2). The last column translates the estimated coef“Gold” was selected as base award, “Pfalz” as base region, ficients into money equivalents relative to the base category “Spätlese” as base quality attribute, and dry/white as base (a dry-white Gold award winning Spätlese from Pfalz) at style/color category. The regional ranking of award win- the average price in the sample (= 8.96 €). As expected, ning wines reflected by the relative frequencies differs prices are positively related to the sensory evaluation somewhat from the production shares with the smaller (DLG-prize medal) and wines receiving higher ranking regions winning a more than proportional large share of awards command significantly higher prices. Ceteris paribus, the discount for a Silver (Bronze) award relative to a medals. Gold is 3.4% (7.5%) and the premium for a Gold Extra The theory of hedonic pricing models is well documented prize is 11.2%. In monetary terms, the discount for a Silver in the literature (e.g. NERLOVE, 1995). Therefore, we ne(Bronze) award relative to a base category wine is equal to glect a detailed exposition. We hypothesize that consumers about 30¢ (67¢) while the premium for a Gold Extra prize are uncertain about wine quality and their willingness to is roughly 1 €. These numbers are in contrast to much pay depends on quality evaluations from DLG awards relarger price differentials for the quality attributes, which are ceived. Control variables include a set of indicators for all highly significant. For example, an “Auslese” comquality attribute, wine style and color, growing region as mands more than a 50% premium relative to a Spätlese, well as the age of the wine at the time of judging as we can other things equal. As expected, specialty wines such as expect that older wines should achieve higher prices. TBA or Eiswein receive premiums well above 100%. BarBuilding on the seminal work by ROSEN (1974), we assume rique-aged wine carries a high premium of about 7 €. With respect to style and color, dry reds carry a premium relative to non-dry whites. However, there is hardly a price differ3 The skewed distribution in the awards is a weakness in the ential between mild and off-dry styles (11.6% vs. 10.9%). data. However, in recent years an effort was made to toughen The price premium for red wine is 19.7%, which may help the annual national competition in order to improve the credito explain why the proportion of red variety vineyards has bility of the quality indicator. grown from 16% to over 26% in recent years. 4It is interesting to note that both the cheapest and the most expensive wine in the sample received a Gold prize. Moreover, the least expensive Gold Extra prize wine is a bargain at 3.48 €.5For the log-linear functional form, the RESET statistic (F-Test) equaled 1.24.251。