胡杨第四次翻译作业

- 格式:docx

- 大小:14.07 KB

- 文档页数:1

胡杨人家文学作品类阅读原文及答案在目前的语文教育教学活动中,阅读教学,尤其是文本类阅读教学,占的比重非常大,它是学生扩充知识、认识世界的重要途径,下面是店铺为你整理的《胡杨人家》文学作品类阅读原文和答案,一起来看看吧。

《胡杨人家》文学作品类阅读原文分布在额济纳荒漠里的黑水城、红城还有无法考证的大同城,在国人的感情世界和历史记忆里是复杂和纠结的。

这里曾经的一切,胡人、党项人、土尔扈特人、蒙古铁骑、丝绸之路、居延海、黑水河、耶律阿保机、成吉思汗、萧太后、科兹洛夫、黑将军……如今谁又在乎过?谁又知道,额济纳就是党项语发音的“黑水城”?每年的九月下旬,黑水河的上游水闸都要放水,额济纳沿黑水河生长的胡杨林仿佛一夜间被镀上了金色。

因为得到黑水河的滋润,这里的胡杨林要比其他地方的早黄一个月左右。

日出之前赶到二道桥,当走到四道桥,已接近晌午时分,刚过了一座新修的木桥,想找个地方交个“地税”但见有一处胡杨林煞是茂密,便不及细想一溜小跑往里钻了进去。

不曾想到在这林子掩映之下居然“藏”有毗邻的两座蒙古包,心中不禁窃喜,直奔去。

从外观上可以判断出,这两座蒙古包不是旅游区常见的忽悠游客的山寨包,而是真的有人在此居住。

此时胡杨林外飞沙走石,而林子里安静得仿佛时间都为此凝固了。

见蒙古包开着门,没敢靠近,朝里吆喝了声:“家里有人吗?”随着应答声,门里探出一张中所妇女的脸,黑里透红带着油光,乐呵呵地喊我进去喝茶。

晃悠一上午的我此时的确已是口干舌燥、饥肠辘辘,便腆着脸不客气地问:“有吃的吗?”那中年妇女回答脆脆的:“有,跟我们一块吃羊肉饺子吧。

”“我还有朋友在林子外,能一块来吃吗?要多少钱?”我有点儿得寸进尺了。

这一问,也许有些唐突,只见对方一愣。

不知啥时她的身后又多了一张年轻姑娘的脸,有着蒙古人特的刚毅的线条,煞是好看,姑娘接过话题问道:“你们几个人,还想吃啥?”“有手抓羊肉不?”“有!”回答一们是脆脆的,伴以银铃般的笑声。

我就纳了闷了,这哪像是不期而遇,明明是到亲戚家里。

经典内容提要(一)如果是古诗古文类1. 以静夜思为例。

出处:静夜思出自唐代诗人李白。

原文:床前明月光,疑是地上霜。

举头望明月,低头思故乡。

注释:“床”,这里的床有多种解释,一种说法是指井栏,古代井栏有数米高,成方框形围住井口,防止人跌入井内,这种解释下,诗人是站在庭院里,看到井栏前的月光。

还有一种说法是指卧榻。

“疑”,怀疑、好像的意思。

翻译:明亮的月光洒在床前的窗户纸上,好像地上泛起了一层霜。

我禁不住抬起头来,看那天窗外空中的一轮明月,不由得低头沉思,想起远方的家乡。

赏析:这首诗短短四句,写得清新朴素。

前两句写诗人在异乡特定环境中一刹那间所产生的错觉。

一个“疑”字,生动地表达了诗人睡梦初醒,迷离恍惚中将照射在床前的清冷月光误作铺在地面的浓霜。

后两句则是通过描写诗人抬头看月、低头思乡的动作神态,深化了诗人的思乡之情。

明月作为一种象征,常常引发人们对故乡、亲人的思念之情,在这里,明月成为连接诗人与故乡的情感纽带。

李白以简洁明快的语言,勾勒出一幅生动的思乡图,引起了无数游子的共鸣。

作者介绍:李白,字太白,号青莲居士,又号“谪仙人”,是唐代伟大的浪漫主义诗人,被后人誉为“诗仙”。

他的诗风豪放飘逸、意境奇妙,语言优美,充满浪漫主义色彩。

他一生渴望入仕,实现自己的政治抱负,但仕途坎坷。

他游历四方,创作了大量优秀的诗歌,题材广泛,包括山水诗、边塞诗、送别诗等。

他的诗歌对后世诗歌的发展产生了深远的影响,许多诗人都受到他的启发和影响。

(二)如果是单字/组词类1. 以“美”字为例。

读音:měi。

出处:“美”字最早见于甲骨文。

解释:作形容词时,有美丽、好看的意思,如“美人”“美景”;也有善、好的意思,如“美德”“美意”。

作名词时,可以指美好的事物,如“美不胜收”中的“美”。

造句:她是一个美丽的姑娘,有着迷人的笑容。

我们要弘扬中华民族的传统美德。

近义词:丽、佳、好。

反义词:丑、恶。

(三)如果是合同、范本、协议书、模板类型1. 房屋租赁合同结构:合同开头要明确合同双方,即出租方(甲方)和承租方(乙方)的基本信息,包括姓名、身份证号码(此处为示例,实际使用时可根据需求确定是否添加)、联系地址、联系电话等。

上海市静安区2023-2024学年七年级上学期期末语文试题学校:___________姓名:___________班级:___________考号:___________一、名句名篇默写二、诗歌鉴赏阅读诗歌,完成下面小题闻王昌龄左迁龙标遥有此寄杨花落尽子规啼,闻道龙标过五溪。

我寄愁心与明月,随君直到夜郎西。

2.这是一首(体裁)。

李白和王昌龄都是代诗人。

3.以下对这首作品理解不正确...的一项是()A.王昌龄当时身处逆境,这点从“左迁”中可知B.诗歌中的两处“龙标”指的是唐代的一个县名C.“杨花”飘零、“子规”悲啼烘托出伤感的氛围D.“愁心”明确表达了诗人对朋友的同情和关切三、文言文阅读阅读下文,完成下面小题穿井得一人宋之丁氏,家无井而出溉汲,常一人居外。

及其家穿井,告人曰:“吾穿井得一人。

”有闻而传之者:“丁氏穿井得一人。

”国人道之,闻之于宋君。

宋君令人问之于丁氏,丁氏对曰:“得一人之使,非得一人于井中也。

”求闻之若此,不若无闻也。

4.课文节选自(书名)。

5.用现代汉语翻译文中画线句丁氏对曰:“得一人之使,非得一人于井中也。

”6.同样是“闻”,宋君的做法是“ ”,是因为他觉得这个信息。

宋君的应对告诉我们的道理是阅读下文,完成下面小题。

桑中生李张助于田中种禾,见李核,顾见空桑①,中有土,因植种。

后有人见桑中忽生李,以为神,转相告语。

有病目痛者②息阴下,言:“李君③令我目愈,谢以一豚④。

”目痛小疾,亦行自愈。

众犬吠声⑤,盲者得视,远近翕赫⑥,其下车马常数千百,酒肉滂沱⑦。

间一岁余,张助远出⑧来还,见之,惊云:“此有何神?乃我所种耳④。

”因就斫之。

(选自晋・千宝《搜神记》,有删改)【注释】①空桑:空心桑树。

①病目痛者:眼痛的病人。

①李君:指空桑里长出的李树。

①豚(tún):小猪。

①众犬吠声:形容众人随声传闻。

①翕赫(xī)(hè):轰动。

①滂沱:指李树旁满酒肉。

①远出:出远门。

7.这棵李树被视为神树经历了两次传闻,第一次是因为“ ”的异象:第二次则因为明明是,却在传闻中变成了。

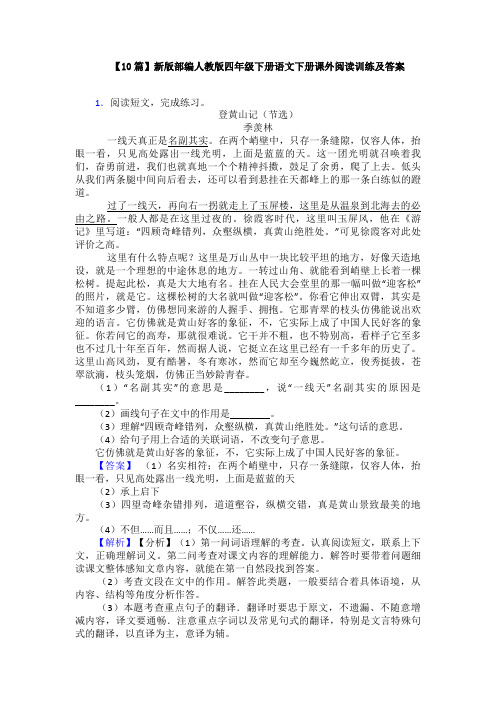

【10篇】新版部编人教版四年级下册语文下册课外阅读训练及答案1.阅读短文,完成练习。

登黄山记(节选)季羡林一线天真正是名副其实。

在两个峭壁中,只存一条缝隙,仅容人体,抬眼一看,只见高处露出一线光明,上面是蓝蓝的天。

这一团光明就召唤着我们,奋勇前进,我们也就真地一个个精神抖擞,鼓足了余勇,爬了上去。

低头从我们两条腿中间向后看去,还可以看到悬挂在天都峰上的那一条白练似的蹬道。

过了一线天,再向右一拐就走上了玉屏楼,这里是从温泉到北海去的必由之路。

一般人都是在这里过夜的。

徐霞客时代,这里叫玉屏风,他在《游记》里写道:“四顾奇峰错列,众壑纵横,真黄山绝胜处。

”可见徐霞客对此处评价之高。

这里有什么特点呢?这里是万山丛中一块比较平坦的地方,好像天造地设,就是一个理想的中途休息的地方。

一转过山角、就能看到峭壁上长着一棵松树。

提起此松,真是大大地有名。

挂在人民大会堂里的那一幅叫做“迎客松”的照片,就是它。

这棵松树的大名就叫做“迎客松”。

你看它伸出双臂,其实是不知道多少臂,仿佛想同来游的人握手、拥抱。

它那青翠的枝头仿佛能说出欢迎的语言。

它仿佛就是黄山好客的象征,不,它实际上成了中国人民好客的象征。

你若问它的高寿,那就很难说。

它干并不粗,也不特别高,看样子它至多也不过几十年至百年,然而据人说,它挺立在这里已经有一千多年的历史了。

这里山高风劲,夏有酷暑,冬有寒冰,然而它却至今巍然屹立,俊秀挺拔,苍翠欲滴,枝头笼烟,仿佛正当妙龄青春。

(1)“名副其实”的意思是________,说“一线天”名副其实的原因是________。

(2)画线句子在文中的作用是________。

(3)理解“四顾奇峰错列,众壑纵横,真黄山绝胜处。

”这句话的意思。

(4)给句子用上合适的关联词语,不改变句子意思。

它仿佛就是黄山好客的象征,不,它实际上成了中国人民好客的象征。

【答案】(1)名实相符;在两个峭壁中,只存一条缝隙,仅容人体,抬眼一看,只见高处露出一线光明,上面是蓝蓝的天(2)承上启下(3)四望奇峰杂错排列,道道壑谷,纵横交错,真是黄山景致最美的地方。

《第15课白杨礼赞》课时练1.下列字形和加点字注音全部正确的一项是()A.婆娑.(suō)锤炼潜.滋暗长(qián)恹恹欲睡B.秀颀.(qí)宛若倔.强挺立(juè)积雪初溶C.虬.枝(qiú)伟岸无边无垠.(yínɡ)纵横绝荡D.主宰.(zhǎi)挺拨坦荡如砥.(dǐ)旁逸斜出2.下列句子加点词语使用不正确的一项是()A.王刚一直想买一套中华书局于20世纪80年代出版的《史记》,这次去上海出差,终于买到了,真是妙.手偶得...啊!B.远处可见黄河的径流在坦荡如砥....的高原上勾勒出粗犷的线条,而这之上,是无垠的蔚蓝的天空。

C.刚开始我还不觉得有什么,可是时间长了,有一种奇怪的感受在潜滋暗长....。

D.唯有倾尽全力地拼搏、不折不挠....地坚守、无怨无悔地奉献,才能实现人生的升华。

3.下列句子没有语病的一项是()A.他非常喜欢茅盾的作品,对《子夜》曾反复阅读,直到被翻看得破烂不堪。

B.民生工作面广量大,任何一件小事乘以14亿人口都是一项巨大挑战。

C.当国旗冉冉升起时,运动员们的目光和歌声都集中到竖立在领奖台前的旗杆上。

D.随着“北斗三号”最后一颗组网卫星成功发射,标志着我国自主建设、独立运行的全球卫星导航系统已经达到世界领先水平。

4.下面文字横线处的句子顺序已被打乱,请按正确的顺序将之填写在横线上。

(只填序号)胡杨是一种神奇的树。

①长大了,树干挺直,叶子就成为杨树叶子的形状,只不过尺寸小一些。

②一棵粗壮的胡杨,离地一米以下长有枝条的话,叶子一定是柳叶的样子,高一些就是杨树的叶子,再高一些会有枫叶的形状。

③所以,胡杨也被称为“异叶杨”“变叶杨”。

④胡杨的奇特之处还在于一树三种叶。

⑤小的时候形状如柳树,枝条柔软,叶子细长。

阅读下文,完成题目。

松树的风格陶铸①去年冬天,我从英德到连县去,沿途看到松树郁郁苍苍,生气勃勃,傲然屹立。

虽是坐在车子上,一棵棵松树一晃而过,但它们那种不畏风霜的姿态,却使人油然而生敬意,久久不忘。

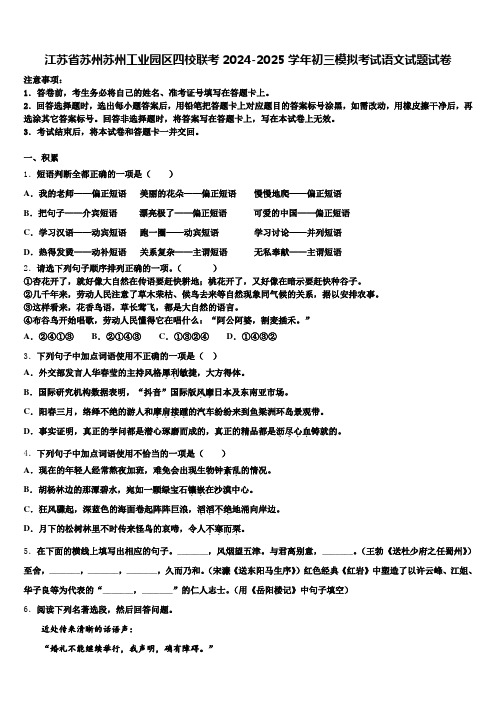

江苏省苏州苏州工业园区四校联考2024-2025学年初三模拟考试语文试题试卷注意事项:1.答卷前,考生务必将自己的姓名、准考证号填写在答题卡上。

2.回答选择题时,选出每小题答案后,用铅笔把答题卡上对应题目的答案标号涂黑,如需改动,用橡皮擦干净后,再选涂其它答案标号。

回答非选择题时,将答案写在答题卡上,写在本试卷上无效。

3.考试结束后,将本试卷和答题卡一并交回。

一、积累1.短语判断全都正确的一项是()A.我的老师——偏正短语美丽的花朵——偏正短语慢慢地爬——偏正短语B.把句子——介宾短语漂亮极了——偏正短语可爱的中国——偏正短语C.学习汉语——动宾短语跑一圈——动宾短语学习讨论——并列短语D.热得发烫——动补短语关系复杂——主谓短语无私奉献——主谓短语2.请选下列句子顺序排列正确的一项。

()①杏花开了,就好像大自然在传语要赶快耕地;桃花开了,又好像在暗示要赶快种谷子。

②几千年来,劳动人民注意了草木荣枯、候鸟去来等自然现象同气候的关系,据以安排农事。

③这样看来,花香鸟语,草长莺飞,都是大自然的语言。

④布谷鸟开始唱歌,劳动人民懂得它在唱什么:“阿公阿婆,割麦插禾。

”A.②④①③B.②①④③C.①③②④D.①④③②3.下列句子中加点词语使用不正确的一项是()A.外交部发言人华春莹的主持风格犀利..敏捷,大方得体。

B.国际研究机构数据表明,“抖音”国际版风靡..日本及东南亚市场。

C.阳春三月,络绎不绝的游人和摩肩接踵....的汽车纷纷来到鱼梁洲环岛景观带。

D.事实证明,真正的学问都是潜心琢磨而成的,真正的精品都是沥尽心血....铸就的。

4.下列句子中加点词语使用不恰当的一项是()A.现在的年轻人经常熬夜加班,难免会出现生物钟紊乱..的情况。

B.胡杨林边的那潭碧水,宛如一颗绿宝石镶嵌..在沙漠中心。

C.狂风骤起,深蓝色的海面卷起阵阵巨浪,滔滔不绝....地涌向岸边。

D.月下的松树林里不时传来怪鸟的哀啼,令人不寒而栗....。

初中语文-中考阅读理解——《胡杨树》①我从来没有见过这样的树。

我完全被它惊呆、慑服,为它心潮澎湃而热血沸腾。

真的,平淡的生活中,很难有这样的人与事,让我能够如此激动以至血液中腾起炽烈的火焰,更别说司空见惯的被污染的大气层玷污得灰蒙蒙的树了。

这样的树却让我精神一振,一下子涌出生命本有的那种铺天卷地推枯拉朽的力量来。

②这便是胡杨树!③这样的树只有这大漠荒原中才能够见到。

站在清冽而奔腾的塔里木河河畔,纵目眺望南北两岸莽莽苍苍的胡杨林,我的心中感受到一种人未有过的震撼,如同那汹涌的河水冲击着我的心房。

④塔里木河两岸各自纵深四十余公里,是胡杨的领地。

前后一片绿色,与包围着它的浓重的浑黄做着动人心魄的对比。

这一片浓重的颜色波动着,翻涌着,连天铺地,是这晨最为醒目的风景线。

⑤真的,只要看见这样的树,其他的树都太孱弱渺小了。

都说银杏树古老,一树金黄的小扇子扇着不尽的悠悠古风,能比得上胡杨吗?一亿三千五百万年前,胡杨就生存在这个地球上了。

都说松柏苍翠,经风霜不凋如叶针般坚贞不屈,能比得胡杨吗?胡杨不畏严寒酷暑,不怕风沙干旱,活着不死一千年,死后不倒一千年,倒地不烂又一千年,松柏抵得上它这三千年如此顽强的生命力和宁折不弯、宁死不朽的性格吗?更不要说纤纤如丝摇弯腰枝的杨柳,一抹胭脂红取媚于春风的桃李,不敢见一片冰雪花的棕檬桉,不能离开温柔水乡的老榕树⑥胡杨!只有胡杨挺立在塔里木河河畔,四十公里方阵一般,横空出世,威风凛凛。

无风时,它们在阳光下岿然不动,肃穆超然犹如静禅,仪态万千犹如根雕世上永远难以匹敌的如此巨大苍莽而诡谲的根雕。

它们静观世上风云变化,日落日出,将无限心事埋在心底。

它们每一棵树都是一首经得住咀嚼和思考的无言诗!⑦劲风掠过时,它们纷披的枝条抖动着,如同金戈铁马呼啸而来,如同惊涛骇浪翻卷而来。

它们狂放不羁地啸叫,它们让世界看到的是男儿心是英雄气是泼墨如云的大手笔,是世上穿戴越来越花哨却越来越难遮掩单薄的人们所久违的一种力量,一种精神!⑧远处望去,它们显得粗糙,近乎梵高笔下的矿工速写和罗中立笔下的父亲皱纹斑斑的脸。

陕西省2024—2025学年高三上第一次校际联考语文试题注意事项:1.本试卷共10页,全卷满分150分,答题时间150分钟。

2.答卷前,务必将答题卡上密封线内的各项目填写清楚。

3.回答选择题时,选出每小题答案后,用2B铅笔把答题卡上对应题目的答案标号涂黑。

如需改动,用橡皮擦干净后,再选涂其它答案标号。

回答非选择题时,将答案写在答题卡上。

写在本试卷上无效。

4.考试结束,监考员将试题卷、答题卡一并收回。

第Ⅰ卷(阅读题共70分)一、现代文阅读(35分)(一)现代文阅读Ⅰ(本题共5小题,19分)阅读下面的文字,完成1~5题。

材料一:人工智能(AI)是指在机器上实现类似乃至超越人类的感知、认知、行为等智能的系统。

与人类历史上其他技术革命相比,人工智能对人类社会发展的影响可能位居前列。

人类社会也正在由以计算机、通信、互联网、大数据等技术支撑的信息社会,迈向以人工智能为关键支撑的智能社会,人类生产生活以及世界发展格局将由此发生更加深刻的改变。

人工智能分为强人工智能和弱人工智能。

强人工智能,也称通用人工智能,是指达到或超越人类水平的、能够自适应地应对外界环境挑战的、具有自我意识的人工智能。

弱人工智能,也称狭义人工智能,是指人工系统实现专用或特定技能的智能,如人脸识别、机器翻译等。

迄今为止大家熟悉的各种人工智能系统,都只实现了特定或专用的人类智能。

弱人工智能可以在单项上挑战人类,比如下围棋,人类已经不是人工智能的对手了。

中国是世界上人工智能研发和产业规模最大的国家之一。

虽然我们在人工智能基础理论与算法、核心芯片与元器件、机器学习算法开源框架等方面起步较晚,但在国家人工智能优先发展策略、大数据规模、人工智能应用场景与产业规模、青年人才数量等方面具有优势。

中国的人工智能发展,挑战与机遇同在,机遇大于挑战。

尽管是后来者,但我们市场规模大,青年人多,奋斗精神强,长期来看更有优势。

我们可以预见,本世纪中叶前后人工智能可能会带来下一次工业革命,影响百年。

第三单元综合素质评价(限时:150分钟满分:120分)一、积累和运用(共5 小题,计17 分)1. 经典诗文默写。

[在(1)~(6)题中任选四题,在(7)(8)题中,任选一题](6 分)(1)几处早莺争暖树,___________________。

(白居易《钱塘湖春行》)(2) ___________________,归雁入胡天。

(王维《使至塞上》)(3)悬泉瀑布,___________________。

(郦道元《三峡》)(4) ___________________,水中藻、荇交横,盖竹柏影也。

(苏轼《记承天寺夜游》)(5)牧人驱犊返,___________________。

(王绩《野望》)(6) ___________________,芳草萋萋鹦鹉洲。

(崔颢《黄鹤楼》)(7)李白《渡荆门送别》中“_______________________,_____________________”两句用游动的视角来描写景物的变化。

(8)周末,我来到观音湖游玩。

看到清澈见底的湖水,自由游弋的鱼儿,我不禁想起《与朱元思书》中的句子“__________________,___________________”。

阅读语段,完成2、3 题。

入秋后,整片胡杨林被金灿灿的色彩染透,华贵而壮美,让人感觉到一种别致的气韵。

无数棵粗壮的胡杨树,像一个个征战沙场的勇士,伫.立在秋风之中,傲然挺拔。

遒劲.的树干上裹着斑驳的树皮,风沙侵shí之后留下的伤痕被岁月的年轮刻画成生命的印记。

秋风卷起零落的黄叶,在经年累月与风沙的搏斗中,有些胡杨树gōu偻了、倾斜了,甚至即将倒在地上,但生命没有就此结束。

2. 请根据语境,选出加点字正确的读音。

(只填序号)(2 分)(1)……伫.(A. chùB. zhù)立在秋风之中,傲然挺拔。

( )(2)遒劲.(A. jìn B. jìng)的树干上裹着斑驳的树皮。

Evaluation of 1D and 2D numerical models for predicting riverflood inundationM.S.Horritt a,*,P.D.Bates b,1aSchool of Geography,University of Leeds,Woodhouse Lane,Leeds LS29JT,UK.bSchool of Geographical Sciences,University of Bristol,University Road,Bristol BS81SS,UKReceived 11January 2002;revised 13May 2002;accepted 22May 2002Abstract1D and 2D models of flood hydraulics (HEC-RAS,LISFLOOD-FP and TELEMAC-2D)are tested on a 60km reach of the river Severn,UK.Synoptic views of flood extent from radar remote sensing satellites have been acquired for flood events in 1998and 2000.The three models are calibrated,using floodplain and channel friction as free parameters,against both the observed inundated area and records of downstream discharge.The predictive power of the models calibrated against inundation extent or discharge for one event can thus be measured using independent validation data for the second.The results show that for this reach both the HEC-RAS and TELEMAC-2D models can be calibrated against discharge or inundated area data and give good predictions of inundated area,whereas the LISFLOOD-FP needs to be calibrated against independent inundated area data to produce acceptable results.The different predictive performances of the models stem from their different responses to changes in friction parameterisation.q 2002Elsevier Science B.V.All rights reserved.Keywords:Flood forecasting;Modelling;Calibration;Validation;Remote sensing1.IntroductionRecent work on calibration and validation of 2D models of river flood inundation (Feldhaus et al.,1992;Romanowicz et al.,1996;Romanowicz and Beven,1997;Bates et al.,1998;Horritt,2000;Bates and De Roo 2000;Horritt and Bates,2001a,b;Aronica et al.,2002)has demonstrated how both raster-based and finite element approaches can be used to reproduce observed inundation extent and bulk hydrometric response for river reaches 5–60km inlength.Remote sensing has also been demonstrated to be a useful tool in mapping flood extent (Horritt et al.,2001)and hence for validating numerical inundation models.These studies have,however,been limited to model calibration against a single flood event,and are therefore only a limited test of the models’predictive power.Furthermore,calibration or validation of a 1D model against 2D inundation data has yet to be carried out.There is therefore no indication of the relative performance of 1D and 2D approaches in predicting floodplain inundation.The predictive power of flood inundation models is assessed in this paper through the analysis of two flood events on the same river reach and a comparison with the predictions of 1D and 2D modelling approaches.The use of remotely sensed maps of flood extent0022-1694/02/$-see front matter q 2002Elsevier Science B.V.All rights reserved.PII:S 0022-1694(02)00121-XJournal of Hydrology 268(2002)87–99/locate/jhydrol1Tel.:þ44-117-928-9108;fax:þ44-117-928-7878.*Corresponding author.Tel.:þ44-113-343-6833;fax:þ44-113-343-3308.E-mail addresses:m.horritt@ (M.S.Horritt),paul.bates@ (P.D.Bates).(Smith,1997;Bates et al.,1997;Horritt et al.,2001)to validateflood models(Horritt,2000)has strongly influenced the development of such codes in recent years.The2D nature offlood maps has promoted the use of2D models in order to promote the synergy between distributed observations and predictions, whereas point measurements of stage or discharge are more compatible with1D models.The high resolution of remotely sensed data,especially from synthetic aperture radar(SAR)systems(typically a few tens of metres),has encouraged modelling at a higher spatial resolution than was previously prac-tical,and has also encouraged the integration of high resolution DEMs into hydraulic models(Marks and Bates,2000).Inundation extent data have also provided a second source of observed data indepen-dent of hydrometry,allowing models to be indepen-dently calibrated and validated.This has already exposed weaknesses in raster-based models of dynamicflood events(Horritt and Bates,2001a), showing that model predictions calibrated against inundation extent reproduce bulkflow behaviour poorly,and vice versa.It is impossible to detect this poor performance with calibration data alone,and the combination of inundation extent data and hydrom-etry can therefore be used to discriminate between models in a rigorous fashion.This has also shaped the criteria for model evaluation,for example,by defining a good model as being one that can reproduceflood extent when calibrated against hydrometric data.This property will become important as inundation models are applied in operational scenarios,where models calibrated against(relatively common)hydrometric data will be used to predictflood extent for which only limited validation data sets are available.The integration of hydrometric andflood extent data has thus been shown to be useful in discriminat-ing betweenflood inundation models,and if a calibration methodology is adopted for unconstrained parameters,the optimal parameter values may well be different for models calibrated against hydrometric and inundation data.A further complication is that optimal parameter sets may well be different for differentflood events,and this will reduce a model’s predictive power.In particular,it is unclear as to whether a parameter set calibrated against data from an event with a certain magnitude will be valid for a more extreme event.One of the criteria for assessing model performance thus becomes the stability of the model calibration with respect to changing event magnitude.This is of practical importance,since we would like to be able to calibrate a hydraulic model against observed low magnitude(and hence relatively common)events,and use the calibrated model to predict the impact of larger magnitude events,for example,the one in100yearflood,for planning and risk assessment purposes.Due to the rarity of inundation extent data sets,this has so far not been undertaken.The research presented in this paper aims to assess the performance of1D and2Dflood models,and in particular their ability to predict inundation extent for oneflood event when calibrated on another.This will allow us to assess the models’suitability for practical risk and hazard assessment.The models used reflect a move in recent years from a1D approach(represented by the US Army Corps of Engineers HEC-RAS model)towards2Dfinite element(TELEMAC-2D developed by Electricite´de France)and raster-based (LISFLOOD-FP)models.These models are tested on a60km reach of the river Severn,UK,where two flood events have been observed with satellite borne SAR sensors.The paper proceeds with a brief description of the three models,the test site and validation data,results of calibration studies for the two events,and an assessment of model performance when model calibrations are transferred between two flood events.2.Models and test site2.1.HEC-RASThe HEC-RAS model solves the full1D St Venant equations for unsteady open channelflow:›Aþ›f Qcþ›ð12fÞQf¼0ð1Þ›Q›tþ››x cf2Q2A c!þ››x fð12fÞ2Q2A f!þgA c›z›x cþS cþgA f›z›x fþS f¼0ð2ÞM.S.Horritt,P.D.Bates/Journal of Hydrology268(2002)87–99 88f¼K cK cþK f;where K¼A5=3nPð3ÞS c¼f2Q2n2cR c A c;S f¼ð12fÞ2Q2n2fRfAfð4ÞQ is the totalflow down the reach,A(A c,A f)the cross sectional area of theflow(in channel,floodplain),x c and x f are distances along the channel andfloodplain (these may differ between cross sections to allow for channel sinuosity),P the wetted perimeter,R the hydraulic radius(A/P),n the Manning’s roughness value and S the friction slope.f determines howflow is partitioned between thefloodplain and channel, according to the conveyances K c and K f.These equations are discretized using thefinite difference method and solved using a four point implicit(box) method.2.2.LISFLOOD-FPLISFLOOD-FP is a raster-based inundation model specifically developed to take advantage of high resolution topographic data sets(Bates and De Roo, 2000).Channelflow is handled using a1D approach that is capable of capturing the downstream propa-gation of afloodwave and the response offlow to free surface slope,which can be described in terms of continuity and momentum equations as:›Q x þ›At¼qð5ÞS02n2P4=3Q2A2›h›x¼0ð6ÞQ is the volumetricflow rate in the channel,A the cross sectional area of theflow,q theflow into the channel from other sources(i.e.from thefloodplain or possibly tributary channels),S0the down-slope of the bed,n Manning’s coefficient of friction,P the wetted perimeter of theflow,and h theflow depth.In this case,the channel is assumed to be wide and shallow, so the wetted perimeter is approximated by the channel width.Eqs.(5)and(6)are discretized using finite differences and a fully implicit scheme for the time dependence,and the resulting non-linear system is solved using the Newton–Raphson scheme. Sufficient boundary conditions are provided by an imposedflow at the upstream end of the reach and an imposed water elevation at the downstream end.The channel parameters required to run the model are its width,bed slope,depth(for linking tofloodplain flows)and Manning’s n value.Width and depth are assumed to be uniform along the reach,their values assuming the average values taken from channel surveys.Channel surveys also provide the bed elevation profile,which can have a gradient which varies along the reach,and which also may become negative if the diffusive wave model is used.The Manning’s n roughness is left as a calibration parameter.Floodplainflows are similarly described in terms of continuity and momentum equations,discretized over a grid of square cells which allows the model to represent2D dynamicflowfields on thefloodplain. We assume that theflow between two cells is simply a function of the free surface height difference between those cells(Estrela and Quintas,1994):d h i;jd t¼Q i21;jx2Q i;j xþQ i;j21y2Q i;j yD x D yð7ÞQ i;j x¼h5=3flownh i21;j2h i;jD x!1=2D yð8Þwhere h i,j is the water free surface height at the node ði;jÞ;D x and D y are the cell dimensions,n is the Manning’s friction coefficient for thefloodplain,and Q x and Q y describe the volumetricflow rates between floodplain cells.Q y is defined analogously to Eq.(8). Theflow depth,hflow,represents the depth through which water canflow between two cells,and is defined as the difference between the highest water free surface in the two cells and the highest bed elevation(this definition has been found to give sensible results for both wetting cells and forflows linkingfloodplain and channel cells).While this approach does not accurately represent diffusive wave propagation on thefloodplain,due to the decoupling of the x-and y-components of theflow,it is computationally simple and has been shown to give very similar results to a faithfulfinite difference discretisation of the diffusive wave equation(Horritt and Bates,2001b).Eq.(8)is also used to calculateflows between floodplain and channel cells,allowingfloodplain cell depths to be updated using Eq.(7)in response toflowM.S.Horritt,P.D.Bates/Journal of Hydrology268(2002)87–9989from the channel.These flows are also used as the source term in Eq.(5),effecting the linkage of channel and floodplain flows.Thus only mass transfer between channel and floodplain is represented in the model,and this is assumed to be dependent only on relative water surface elevations.While this neglects effects such as channel-floodplain momentum transfer and the effects of advection and secondary circulation on mass transfer,it is the simplest approach to the coupling problem and should reproduce some of the behaviour of the real system.2.3.TELEMAC-2DThe TELEMAC-2D (Galland et al.,1991;Her-vouet and Van Haren,1996)model has been applied to fluvial flooding problems for a number of river reaches and events (Bates et al.,1998).The model solves the 2D shallow water (also known as Saint-Venant or depth averaged)equations of free surface flow:›v ›t þðv ·7Þv þg 7ðz 0þh Þþn 2g v l v l h 4=3¼0ð9Þ›h›tþ7ðh v Þ¼0ð10Þwhere v is a 2D depth averaged velocity vector,h is the flow depth,z 0the bed elevation,g the acceleration due to gravity,and n Manning’s coefficient of friction.The TELEMAC-2D model uses Galerkin’s method of weighted residuals to solve Eqs.(9)and (10)over an unstructured mesh of triangular finite elements.A streamline-upwind-Petrov–Galerkin (SUPG)technique is used for the advection of flow depth in the continuity equation to reduce the spurious spatial oscillations in depth that Galerkin’s method is predisposed to,and the method of characteristics is used for the advection of velocity.The resulting linear system is solved using a gradient mean residual technique and efficient matrix assembly is ensured using element-by-element methods.The time develop-ment of the solutions is dealt with using an implicit finite difference scheme and the moving boundary nature of the problem is treated with a simple wetting and drying algorithm which eliminates spurious free surface slopes at the shoreline (Hervouet and Janin,1994).Fig.1.RADARSAT image of the reach used to test the models.The flood boundary is delineated in black,and the urban area of Shrewsbury shown.The rectangle gives the approximate location of the detail images in Fig.3and subsequent maps of model predicted inundationextent.Fig.2.Upstream hydrographs for the 1998(top)and 2000(bottom)flood events.The satellite overpass times are also marked.M.S.Horritt,P.D.Bates /Journal of Hydrology 268(2002)87–99902.4.Test site and validation dataThe three models have been set up to represent a 60km reach of the river Severn,UK (Fig.1).The reach is well provided with topographic data.The channel is described by a series of 19ground surveyed cross sections,and airborne laser altimetry (Mason et al.,1999;Cobby et al.,2000)is used to derive a high resolution (50m),high accuracy (,15cm)floodplain DEM.Validation data are provided by two satellite SAR images.The first coincides with a flood event on 30th October 1998,with a peak flow of 435m 3s 21at the upstream end of the reach (Fig.2,top).This is well over bankful discharge (,180m 3s 21),and considerable floodplain inundation occurred.The event was observed by the RADARSAT satellite,operating at C-band (5.3GHz,5.6cm),HH polarisation and an incidence angle of 36–428(shown as backdrop to Fig.1).The second event occurred on 11th November 2000,with a peak flow of 391m 3s 21(Fig.2,bottom),and was captured by the ERS-2satellite SAR,again operating at C-band,VV polarisation and an incidence angle of 20–268.Both sensors produce imagery with a pixel size of 12.5m and a ground resolution of approxi-mately 25m.Imagery from the two sensors is shown in Fig.3.They show that the flood is easily distinguished as a region of very low backscatter in the RADARSAT imagery (Fig.3,top left),but detecting the waterlineis much more difficult in the ERS-2image (top right),where wind roughening of the water surface has increased backscatter to levels similar to some floodplain landcover types (Horritt,2000;Horritt et al.,2001).This differential sensitivity to wind roughening is probably due to both the different incidence angle and polarisations used by the two sensors.The consequence is that for the greater part of the reach,it is extremely difficult to distinguish between the flooded and unflooded state in the ERS-2imagery,but the shoreline is obvious in some places,probably where the water surface is sheltered from the wind by trees or topography.Given the different nature of the images,two processing strategies were adopted.The shoreline in the 1998RADARSAT imagery was delineated using a statistical active contour model (Horritt,1999;Horritt et al.,2001)which has been found to be capable of locating the shoreline to ,2pixels,and then transformed to a raster map of the flooded/non-flooded state at a resolution of 12.5m.The 2000ERS-2imagery was first smoothed using a 3£3moving average filter to reduce speckle,then thresholded into 3classes:flooded,unflooded and undetermined,again at 12.5m resolution.The undetermined class can then be ignored in any calculation of model fit.The results of this classification are also given in Fig.3(bottom left and bottom right).Hydrometric data can also be used for validation/-calibration.Although the downstream stage is already used as a model boundary condition,the floodwave travel time has been found to be useful in model calibration (Bates et al.,1998)even if it is not wholly independent of downstream stage measurements.A model where peak flow at the downstream boundary coincides with peak-measured flow can be viewed as predicting travel time correctly.The measured travel times were similar for the two events:25.5h for 1998and 24h for 2000.The HEC-RAS model was set up using the 19cross sections to provide the channel width and bed elevations.These sections were extended on both sides of the channel using the LiDAR derived DEM to provide floodplain topography.The section was then described by 5–10points on each side of the channel coinciding with significant topographic features such as breaks of slope.The bed elevation profile and examples of the cross sections used in theHEC-RASFig.3.1998RADARSAT (left)and 2000ERS-2(right)images (top),with their classifications (bottom).Black represents flooded regions,and grey tones represent undetermined areas.The images are ,7km across,and cover the lower part of the test reach.q European Space Agency and Canadian Space Agency.M.S.Horritt,P.D.Bates /Journal of Hydrology 268(2002)87–9991model are given in Fig.4.Boundary conditions for the model are an imposed dynamic discharge at the upstream end of the reach and an imposed water surface elevation at the downstream end,both provided by stage recorders and a rated section in the case of the imposed discharge.Although the use of the measured free surface elevation at the downstream end does mean that the boundary conditions and validation data (travel times)are not fully indepen-dent,the effect of this was found to be small.The floodwave travel time remains a good source of calibration data,being strongly dependent on the model calibration and not significantly affected by the downstream boundary condition.Predicted inunda-tion extent was then derived by re-projecting the water levels at the 19cross sections onto the high resolution DEM.The LISFLOOD-FP model is based directly on the 50m resolution DEM.The location of the channel is digitised from 1:25000scale maps of the reach.Since the channel width is of the same order as the model resolution,cells of the DEM lying over the channel can be ignored in the floodplain flow calculations (flow between channel cells being handled by the in-channel diffusive flow routing scheme),and flood-plain storage near the channel does not need to be included explicitly as it does for coarse scale LISFLOOD-FP models (Horritt and Bates,2001a).Bed elevations for the 1D flow routing scheme are taken from the 19surveyed cross sections,and linearly interpolated in between.Channel width is taken as constant down the channel.Again the upstream boundary condition is provided by the measured discharge,and the downstream boundary condition is an imposed water surface elevation.The TELEMAC-2D model operates on a mesh of 6485nodes and 12107triangular elements (Fig.5),giving a floodplain resolution of ,30m.Floodplain topography is sampled onto the mesh using nearest neighbours from the 50m DEM,and the channel and bank node elevations are taken from channelsurveysFig.4.Bed elevation profile,with a typical water free surface,for the HEC-RAS model (bottom).A sample cross section is also shown (top).M.S.Horritt,P.D.Bates /Journal of Hydrology 268(2002)87–9992and linearly interpolated between the 19cross sections.Channel planform and the extent of the domain are digitised from 1:25000maps of the reach.The same boundary conditions are used as for the other two models.3.Model calibration and validationTo make a tractable calibration problem,the potentially distributed bed roughness coefficients are limited to one value for the channel and one for the floodplain.This is also appropriate for the lumped criteria used to assess model performance in predict-ing inundation (described below).Channel values vary between n ¼0:01and n ¼0:05m 21=3s ;with floodplain values ranging from n ¼0:02to n ¼0:10m 21=3s for the HEC-RAS and LISFLOOD-FP models.The TELEMAC calibration uses lower friction values (n ¼0:005to n ¼0:04m 21=3s for the channel,n ¼0:01to n ¼0:08m 21=3s on the floodplain),which were found necessary to ensure the optimum Manning’s n values are included within the parameter space.It should be noted that the different process inclusion in each model would meanthat the friction value has a different physical meaning and is drawn from a different distribution.Hence in a 1D model,the friction term accounts for the energy loss due to planform variations,whereas,for a 2D finite element model these losses are represented directly in the domain geometry at the element scale and only subsumed within the friction term at the sub-grid scale.The friction coefficients for each model can thus not be absolutely compared.A simulation for each of the models,friction parameterisations and events was performed.Model predictions of inundation extent are com-pared with the satellite data using the measure of fit:F ¼Num ðS mod >S obs ÞNum ðS mod <S obs Þ£100ð11ÞS mod and S obs are the sets of domain sub-regions (pixels,elements or cells)predicted as flooded by the model and observed to be flooded in the satellite imagery,and Num(·)denotes the number of members of the set.F therefore varies between 0for model with no overlap between predicted and observed inundated areas and 100for a model where these coincide perfectly.This measurehasFig.5.Finite element mesh for the TELEMAC-2D model.M.S.Horritt,P.D.Bates /Journal of Hydrology 268(2002)87–9993been found to give good results in othercalibration studies (Aronica et al.,2002;Horritt and Bates,2001a),and allows a useful comparison between model performance for different modelled reaches and flood events.The models also generate a downstream discharge,which is used to predict the floodwave travel time.Results of the calibration are given in Tables 1and 2for the three models applied to the 1998and 2000events.On first inspection,the tables appear to showTable 1Summary of optimum friction coefficients calibrated on inundated area for the 3models and two events Event Model n ch n flF 1998HEC-RAS 0.050.0664.83LISFLOOD-FP 0.030.06–0.0863.81TELEMAC 0.020.0265.282000HEC-RAS 0.040.1041.79LISFLOOD-FP 0.030.0841.38TELEMAC0.020.0437.41Table 2Summary of optimum friction coefficients calibrated on floodwave travel time for the 3models and two events.The observed travel times were 25.5h for the 1998event and 24h for the 2000event Event Modeln chn flBest travel time1998HEC-RAS 0.04–0.050.08–0.1020LISFLOOD-FP 0.020.02–0.1027TELEMAC 0.040.08252000HEC-RAS 0.03–0.050.06–0.1026LISFLOOD-FP 0.020.02–0.1029TELEMAC 0.020.0624Fig.6.Model sensitivity:the surfaces show how model performance changes with friction coefficients.Top row:measure of fit F for the 1998event.Bottom row:floodwave travel time for the 1998event.Left:HEC-RAS,middle:LISFLOOD-FP,right:TELEMAC-2D.M.S.Horritt,P.D.Bates /Journal of Hydrology 268(2002)87–9994that in terms of calibration,the LISFLOOD-FP models is the best,having approximately the same optimal friction values for both events and giving similar optima when calibrated against the radar and hydrometric data.The model with the most sophisti-cated process representation,TELEMAC-2D,per-forms more poorly in this respect than the other models.However,all three models give similar levels of performance in terms of F at their optimum calibrations,,65%for the1998event and,40%for the2000event.The difference in maximum perform-ance for the two events is due to the different sources of validation data.The ERS-2image contains large areas of uncertainflood state,and in particular lacks data for large areas in the middle of the domain which are easily and correctly predicted asflooded by the models of the1998event.If the uncertain areas are due to wind roughening of the water surface,then we might expect the more sheltered areas at the sides of the valley to provide most of the validation data,just where we would expect the biggest differences in performance to show up.Further differences in model performance are exposed if the full calibration surface(measure offit F orfloodwave travel time as a function of roughness values)is examined,as shown in Fig.6for the1998 event.Results for the2000event are similar,but with lower values of F due to the poor quality of the ERS-2 data.As in Horritt and Bates(2001b),we see that the different model respond differently to changing friction parameters.HEC-RAS shows the most consistent response of inundation extent and travel times:both are optimised for high friction values.The good performance may,however,be due in part to the constraint on the maximum friction values,and using very high values in order to reproduce the25.5h travel time may result in poorer inundation predic-tions.The different sensitivities to channel and floodplain friction are also what might be expected. For low channel friction,water levels are low,there is little inundation and so sensitivity tofloodplain friction is minimal.Higher channel frictions increase water depth in the channel,more water is forced onto thefloodplain,and sofloodplain friction exerts a greater influence on both travel times and inundation extent.LISFLOOD-FP gives a smooth response surface,with very little sensitivity tofloodplain friction when the inundated area is considered.The model is slightly more sensitive tofloodplain friction whenfloodwave travel times are compared.The surfaces for TELEMAC-2D are similar in shape to those for HEC-RAS,but showing less overall sensitivity,varying only between63and65%, compared with20–65%for HEC-RAS.How does this calibration performance affect the predictive performance of the three models?The answer depends on how we use the models in the predictive mode.Records of time varying discharge, and hencefloodwave travel times,are relatively common,but inundation extent data are still relatively rare due to the limited number of radar satellites in operation.It would therefore make sense to define a ‘good’model as one which can be calibrated against discharge measurements and then provides the most accurate predictions offlood extent.This is also in accord with the role of inundation models inflood risk assessment,where it is the extent of theflood,rather than the discharge,which is of interest.The performance is therefore assessed by calibrating on oneflood event and measuring the performance in predicting inundated area for the other,calibrating using the hydrometric data and measuring F(Eq.(11))for the same event,etc.These combinations give6performance evaluations usingTable3Predictive performance of the3models using independent calibration/validation dataCalibration data Validation data HEC-RAS LISFLOOD-FP TELEMAC-2D 1998Hydro1998SAR64.24–64.7454.10–54.5762.882000Hydro2000SAR37.79–41.7933.06–33.7237.131998Hydro2000SAR40.80–41.7933.06–33.7235.902000Hydro1998SAR55.21–64.8354.10–54.5764.461998SAR2000SAR41.4841.29–41.3836.852000SAR1998SAR64.6563.8165.21M.S.Horritt,P.D.Bates/Journal of Hydrology268(2002)87–9995。

Evaluation of 1D and 2D numerical models for predicting

river flood inundation

M.S. Horritt a,*, P.D. Bates b,1

a School of Geography, University of Leeds, Woodhouse Lane, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK.

b School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, University Road, Bristol BS8 1SS, UK Abstract

1D and 2D models of flood hydraulics (HEC-RAS, LISFLOOD-FP and TELEMAC-2D) are tested on a 60 km reach of the river Severn, UK. Synoptic views of flood extent from radar remote sensing satellites have been acquired for flood events in 1998 and 2000. The three models are calibrated, using floodplain and channel friction as free parameters, against both the observed inundated area and records of downstream discharge. The predictive power of the models calibrated against inundation extent or discharge for one event can thus be measured using independent validation data for the second. The results show that for this reach both the HEC-RAS and TELEMAC-2D models can be calibrated against discharge or inundated area data and give good predictions of inundated area, whereas the LISFLOOD-FP needs to be calibrated against independent inundated area data to produce acceptable results. The different predictive performances of the models stem from their different responses to changes in friction parameterisation.

Keywords: Flood forecasting; Modelling; Calibration; Validation; Remote sensing Source: Journal of Hydrology 268 (2002) 87–99

对预测洪水泛滥的一维、二维数值模型的评价

胡杨译

学号:14213376 第4次

摘要

洪水水力学的一维和二维模型(HEC-RAS,LISFLOOD-FP和TELEMAC-2D)在英国塞文河60公里跨度上进行了测试。

从雷达遥感卫星的洪水淹没范围的概况影像已在1998年到2000年用于观测洪水事件。

三个模型用泛滥区和河道摩擦为自由变量来校准观察到的淹没区和下游的流量记录。

该模型校准对淹没范围或一次洪水事件的流量预测能力,可以使用独立的验证数据进行二次测量。

结果表明, HEC-RAS和TELEMAC-2D模型都能进行校准流量或淹没地区数据,得到良好的预测淹没地区,而LISFLOOD-FP需要校准独立的淹没区数据以产生可接受的结果。

这些模型的预测性能的不同,源于他们对于摩擦参数的变化不同的反应。

关键词:防凌;黄河上游;优化模型;水库防凌存储。