华南理工大学2018年《880分析化学》考研专业课真题试卷

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:279.64 KB

- 文档页数:13

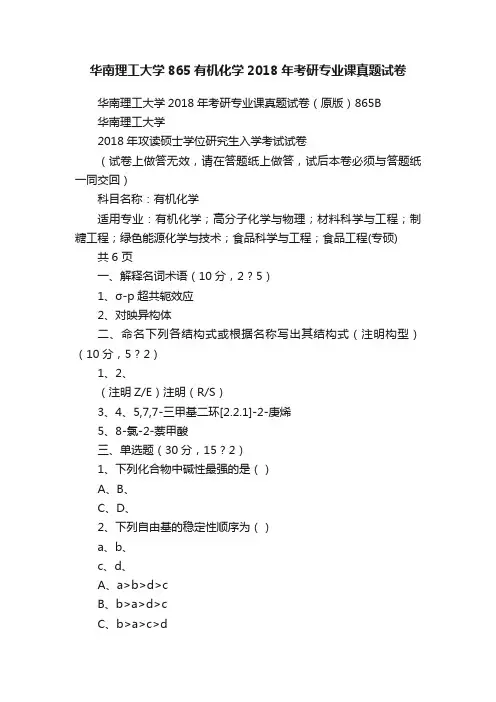

华南理工大学865有机化学2018年考研专业课真题试卷

华南理工大学2018年考研专业课真题试卷(原版)865B

华南理工大学

2018年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷

(试卷上做答无效,请在答题纸上做答,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)

科目名称:有机化学

适用专业:有机化学;高分子化学与物理;材料科学与工程;制糖工程;绿色能源化学与技术;食品科学与工程;食品工程(专硕) 共6 页

一、解释名词术语(10分,2 ? 5)

1、σ-p超共轭效应

2、对映异构体

二、命名下列各结构式或根据名称写出其结构式(注明构型)(10分,5 ? 2)

1、2、

(注明Z/E)注明(R/S)

3、4、5,7,7-三甲基二环[2.2.1]-2-庚烯

5、8-氯-2-萘甲酸

三、单选题(30分,15 ? 2)

1、下列化合物中碱性最强的是()

A、B、

C、D、

2、下列自由基的稳定性顺序为()

a、b、

c、d、

A、a>b>d>c

B、b>a>d>c

C、b>a>c>d

D、d>a>b>c

3、下列化合物的酸性顺序正确的是()第1页。

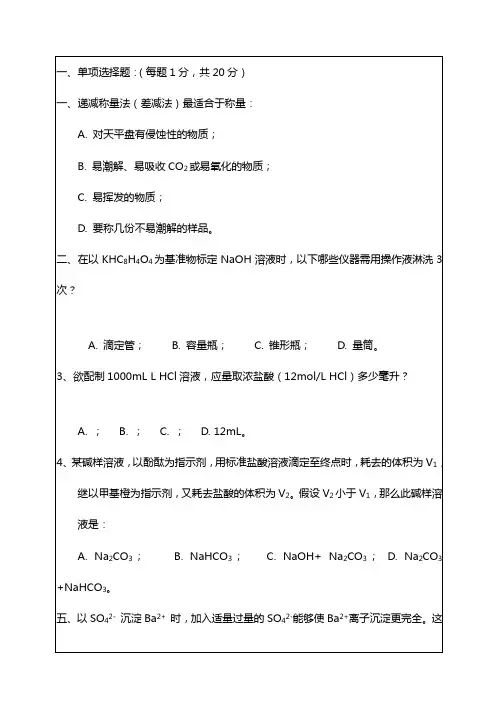

二、在滴定分析中显现以下情形,致使系统误差显现的是:

A. 试样未经充分混匀;

B. 砝码未经校正;

C. 所用试剂中含有干扰离子;

D. 滴定管的读数读错。

3、在分光光度法中,标准曲线偏离比耳定律的缘故是:

A. 利用了复合光;

B. 利用的是单色光;

C. 有色物浓度过大;

D. 有色物浓度较稀。

4、测定试液的pH值(pH x)是以标准溶液的pH值(pH s)为基准,并通过比较E x和

E s值而确信的,如此做的目的是排除哪些阻碍?

A. 不对称电位;

B. 液接电位;

C. 内外参比电极电位;

D. 酸差。

五、以下表达错误的选项是:

A. 难溶电解质的溶度积越大,溶解度越大;

B. 同离子效应使沉淀的溶解度增大;

C. 酸效应使沉淀的溶解度增大;

D .配位效应使沉淀的溶解度减小

三、判断题(每题1分,对的打“”,错的打“”。

共10分):

(已知ZnY K = 1610;pH=10时,散布系数

Y =10-1;NH 3与ZnY 的各级积存稳固常数别离为:1=102; 2=104; 3=107; 4=109)(7分)

六、综合题和简答题(共15分)

一、在碘法测定铜含量时,什么缘故要加NH 4SCN 溶液,若是在酸化后当即加入NH 4SCN 溶液会产生什么阻碍(

5分)

二、请设计浓度为L 的高锰酸钾溶液500mL 的配制及标定实验。

(内容包括:利用仪器,试剂及分析步骤,及结果计算式)(已知M (KMnO 4)=;)(10分)。

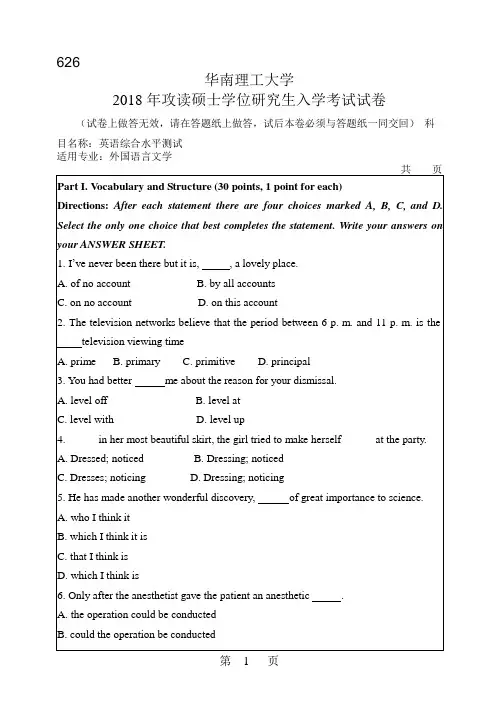

626华南理工大学2018 年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷(试卷上做答无效,请在答题纸上做答,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)科目名称:英语综合水平测试适用专业:外国语言文学performances. Rather than playing tricks with alternatives presented to participants, we secretly altered the outcomes of their choices, and recorded how they react. For example, in an early study we showed our volunteers pairs of pictures of faces and asked them to choose the most attractive. In some trials, immediately after they made their choice, we asked people to explain the reasons behind their choices.Unknown to them, we sometimes used a double-card magic trick to secretly exchange one face for the other so they ended up with the face they did not choose. Common sense dictates that all of us would notice such a big change in the outcome of a choice. But the result showed that in 75 per cent of the trials our participants were blind to the mismatch, even offering “reasons” for their“choice”.We called this effect “choice blindness”, echoing change blindness,the phenomenon identified by psychologists where a remarkably large number of people fail to spot a major change in their environment. Recall the famous experiments where X asks Y for directions; while Y is struggling to help, X is switched for Z - and. Y fails to notice. Researchers are still pondering the full implications, but it does show how little information we use in daily life, and undermines the idea that we know what is going on around us.When we set out, we aimed to weigh in on the enduring, complicated debate about self-knowledge and intentionality. For all the intimate familiarity we feel we have with decision making, it is very difficult to know about it from the “inside”: one of the great barriers for scientific research is the nature of s ubjectivity.As anyone who has ever been in a verbal disagreement can prove, people tend to give elaborate justifications for their decisions, which we have every reason to believe are nothing more than rationalizations after the event. To prove such people wrong, though, or even provide enough evidence to change their mind, is an entirely different matter: who are you to say what my reasons are?But with choice blindness we drive a large wedge between intentions and actions in the mind. As our participants give us verbal explanations about choices they never made, we can show them beyond doubt - and prove it - that what they say cannot be true. So our experiments offer a unique window into confabulation (the story-telling we do to justify things after the fact) that is otherwise very difficult to come by. We can compare everyday explanations with those under lab conditions, looking for such things as the amount of detail in descriptions, how coherent the narrative is, the emotional tone, or even the timing or flow of the speech. Then we can create a theoretical framework to analyse any kind of exchange.This framework could provide a clinical use for choice blindness: for example, two of our ongoing studies examine how malingering might develop into truesymptoms, and how confabulation might play a role in obsessive-compulsive disorder.Importantly, the effects of choice blindness go beyond snap judgments. Depending on what our volunteers say in response to the mismatched outcomes of choices (whether they give short or long explanations, give numerical rating or labeling, and so on) we found this interaction could change their future preferences to the extent that they come to prefer the previously rejected alternative. This gives us a rare glimpse into the complicated dynamics of self-feedback (“I chose this, I publicly said so, therefore I must like it”), which we suspect lies behind the formation of many everyday preferences.We also want to explore the boundaries of choice blindness. Of course, it will be limited by choices we know to be of great importance in everyday life. Which bride or bridegroom would fail to notice if someone switched their partner at the altar through amazing sleight of hand? Yet there is ample territory between the absurd idea of spouse-swapping, and the results of our early face experiments.For example, in one recent study we invited supermarket customers to choose between two paired varieties of jam and tea. In order to switch each participant’s choice without them noticing, we created two sets of “magical” jars, with lids at both ends and a divider inside. The jars looked normal, but were designed to hold one variety of jam or tea at each end, and could easily be flipped over.Immediately after the participants chose, we asked them to taste their choice again and tell us verbally why they made that choice. Before they did, we turned over the sample containers, so the tasters were given the opposite of what they had intended in their selection. Strikingly, people detected no more than a third of all these trick trials. Even when we switched such remarkably different flavors as spicy cinnamon and apple for bitter grapefruit jam, the participants spotted less than half of all s witches.We have also documented this kind of effect when we simulate online shopping for consumer products such as laptops or cell phones, and even apartments. Our latest tests are exploring moral and political decisions, a domain where reflection and deliberation are supposed to play a central role, but which we believe is perfectly suited to investigating using choice blindness.Throughout our experiments, as well as registering whether our volunteers noticed that they had been presented with the alternative they did not choose, we also quizzed them about their beliefs about their decision processes. How did they think they would feel if they had been exposed to a study like ours? Did they think they would have noticed the switches? Consistently, between 80 and 90 per cent of people said that they believed they would have noticed something was wrong.Gervais, discovers a thing called “lying” and what it can get him. Within days, M ark is rich, famous, and courting the girl of his dreams. And because nobody knows what “lying” is? he goes on, happily living what has become a complete and utter farce.It’s meant to be funny, but it’s also a more serious commentary on us all. As Americans, we like to think we value the truth. Time and time again, public-opinion polls show that honesty is among the top five characteristics we want in a leader, friend, or lover; the world is full of sad stories about the tragic consequences of betrayal. At the same time, deception is all around us. We are lied to by government officials and public figures to a disturbing degree; many of our social relationships are based on little white lies we tell each other. We deceive our children, only to be deceived by them in return. And the average person, says psychologist Robert Feldman, the author of a new book on lying, tells at least three lies in the first 10 minutes of a conversation. “There’s always been a lot of lying,” says Feldman,whose new book, The Liar in Your Life, came out this month. “But I do think we’re seeing a kind of cultural shift where we’re lying more, it’s easier to lie, and in some ways it’s almost more acceptable.”As Paul Ekman, one of Feldman’s longtime lying colleagues and the inspiration behind the Fox IV series “Lie To Me” defines it,a liar is a person who “intends to mislead,”“deliberately,” without being asked to do so by the target of the lie. Which doesn’t mean that all lies are equally toxic: some are simply habitual –“My pleasure!”-- while others might be well-meaning white lies. But each, Feldman argues, is harmful, because of the standard it creates. And the more lies we tell, even if th ey’re little white lies, the more deceptive we and society become.We are a culture of liars, to put it bluntly, with deceit so deeply ingrained in our mind that we hardly even notice we’re engaging in it. Junk e-mail, deceptive advertising, the everyday p leasantries we don’t really mean –“It’s so great to meet you! I love that dress”– have, as Feldman puts it, become “a white noise we’ve learned to neglect.” And Feldman also argues that cheating is more common today than ever. The Josephson Institute, a nonprofit focused on youth ethics, concluded in a 2008 survey of nearly 30,000 high school students that “cheating in school continues to be rampant, and it’s getting worse.” In that survey, 64 percent of students said they’d cheated on a test during the past year, up from 60 percent in 2006. Another recent survey, by Junior Achievement, revealed that more than a third of teens believe lying, cheating, or plagiarizing can be necessary to succeed, while a brand-new study, commissioned by the publishers of Feldman’s book, shows that 18-to 34-year-olds--- those of us fully reared in this lying culture --- deceive more frequently than the general population.Teaching us to lie is not the purpose of Feldman’s book. His subtitle, in fact, is “the way to truthful relationships.” But if his book teaches us anything, it’s that we should sharpen our skills — and use them with abandon.Liars get what they want. They avoid punishment, and they win others’ affection. Liars make themselves sound smart and intelligent, they attain power over those of us who believe them, and they often use their lies to rise up in the professional world. Many liars have fun doing it. And many more take pride in getting away with it.As Feldman notes, there is an evolutionary basis for deception: in the wild, animals use deception to “play dead” when threatened. But in the modem world, the motives of our lying are more selfish. Research has linked socially successful people to those who are good liars. Students who succeed academically get picked for the best colleges, despite the fact that, as one recent Duke University study found, as many as 90 percent of high-schoolers admit to cheating. Even lying adolescents are more popular among their peers.And all it takes is a quick flip of the remote to see how our public figures fare when they get caught in a lie: Clinton keeps his wife and goes on to become a national hero. Fabricating author James Frey gets a million-dollar book deal. Eliot Spitzer’s wife stands by his side, while “Appalachian hiker” Mark Sanford still gets to keep his post. If everyone else is being rewarded for lying,don’t we need to lie, too, just to keep up?But what’s funny is that even as we admit to being liars, study after study shows that most of us believe we can tell when others are lying to us. And while lying may be easy, spotting a liar is far from it. A nervous sweat or shifty eyes can certainly mean a person’s uncomfortable, but it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re lying. Gaze aversion, meanwhile, has more to do with shyness than actual deception. Even polygraph machines are unreliable. And according to one study, by researcher Bella DePaulo, we’re only able to differentiate a lie from truth only 47 percent of the time, less than if we guessed randomly. “Basically everything we’ve heard about catching a liar is wrong,” says Feldman, who heads the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.Ekman, meanwhile, has spent decades studying micro-facial expressions of liars: the split-second eyebrow arch that shows surprise when a spouse asks who was on the phone; the furrowed nose that gives away a hint of disgust when a person says “I love you.” He’s trained everyone from the Secret Service to the TSA, and believes that with close study, it’s possible to identify those tiny emotions. The hard part, of course, is proving them. “A lot of times, it’s easier to believe,” says Feldman. “It takes a lot ofThere were, however, different explanations of this unhappy fact. Sean Pidgeon put the blame on “humanities departments who are responsible for the leftist politics that still turn people off.” Kedar Kulkarni blamed “the absence of a culture that privileges Learning to improve oneself as a human being.” Bethany blamed universities, which because they are obsessed with “maintaining funding” default on th e obligation to produce “well rounded citizens.” Matthew blamed no one,because i n his view the report’s priorities are just what they should be: “When a poet creates a vaccine or a tangible good that can be produced by a Fortune 500 company, I’ll rescind my comment.”Although none of these commentators uses the word, the issue they implicitly raise is justification. How does one justify funding the arts and humanities? It is clear which justifications are not available. You cannot argue that the arts and humanities are able to support themselves through grants and private donations. You cannot argue that a state’s economy will benefit by a new reading of “Hamlet.” You can’t argue -- well you can, but it won’t fly -- that a graduate who is well-versed in the history of Byzantine art will be attractive to employers (unless the employer is a museum). You can talk as Bethany does about “well rounded citizens,” but that ideal belongs to an earlier period, when the ability to refer knowledgeably to Shakespeare or Gibbon or the Thirty Years War had some cash value (the sociologists call it cultural capital). Nowadays, larding your conversations with small bits of erudition is more likely to irritate than to win friends and influence people.At one time justification of the arts and humanities was unnecessary because, as Anthony Kronman puts it in a new book, “Education’s End: Why Our Colleges and Universities Have Given Up on the Meaning of Life,” it was assumed that “a college was above all a place for the training of character, for the nurturing of those intellectual and moral habits that together from the basis for living the best life one can.”It followed that the realization of this goal required an immersion in the great texts of literature, philosophy and history even to the extent of memorizing them, for “to acquire a text by memory is to fix in one’s mind the image and example of the author and his subject.”It is to a version of this old ideal that Kronman would have us return, not because of a professional investment in the humanities (he is a professor of law and a former dean of the Yale Law School), but because he believes that only the humanities can address “the crisis of spirit we now confront” and “restore the wonder which those who have glimpsed the human condition have always felt, and which our scientific civilization, with its gadgets and discoveries, obscures.”As this last quotation makes clear, Kronman is not so much mounting a defense ofthe humanities as he is mounting an attack on everything else. Other spokespersons for the humanities argue for their utility by connecting them (in largely unconvincing ways) to the goals of science, technology and the building of careers. Kronman, however, identifies science, technology and careerism as impediments to living a life with meaning. The real enemies, he declares,are “the careerism that distracts from life as a whole” and “the blind acceptance of science and technology that disguise and deny our human condition.” These false idols,he says,block the way to understanding. We must turn to the humanities if we are to “meet the need for meaning in an age of vast but pointless powers,”for only the humanities can help us recover the urgency of “the question of what living is for.”The humanities do this, Kronman explains, by exposing students to “a range of texts that express with matchless power a number of competing answers to this question.” In the course of this program —Kronman calls it “secular humanism”—students will be moved “to consider which alternatives lie closest to their own evolving sense of self?” As they survey “the different ways of living that have been held up by different authors,” they will be encouraged “to enter as deeply as they can into the experiences, ideas, and values that give each its permanent appeal.” And not only would such a “revitalized humanism” contribute to the growth of the self,it “would put the conventional pieties of our moral and political world in question” and “bring what is hidden into the open — the highest goal of the humanities and the first responsibility of every teache r.”Here then is a justification of the humanities that is neither strained (reading poetry contributes to the state’s bottom line) nor crassly careerist. It is a stirring vision that promises the highest reward to those who respond to it. Entering into a conversation with the great authors of the western tradition holds out the prospect of experiencing “a kind of immortality” and achieving “a position immune to the corrupting powers of time.”Sounds great, but I have my doubts. Does it really work that way? Do the humanities ennoble? And for that matter, is it the business of the humanities, or of any other area of academic study, to save us?The answer in both cases, I think, is no. The premise of secular humanism (or of just old-fashioned humanism) is that the examples of action and thought portrayed in the enduring works of literature, philosophy and history can create in readers the desire to emulate them. Philip Sydney put it as well as anyone ever has when he asks (in “The Defense of Poesy” 1595), “Who reads Aeneas carrying old Anchises on his back that wishes not it was his fortune to perform such an excellent act?” Thrill to this picture of42.What does Anthony Kronman oppose in the process to strive for meaningful life?A.Secular humanism.B. Careerism.C. Revitalized humanismD. Cultural capital.43.Which of the following is NOT mentioned in this article?A.Sidney Carton killed himself.B.A new reading of Hamlet may not benefit economy.C.Faust was not willing to sell his soul.D.Philip Sydney wrote The Defense of Poesy.44.Which is NOT true about the author?A.At the time of writing, he has been in the field of the humanities for 45 years.B.He thinks the humanities are supposed to save at least those who study them.C.He thinks teachers and students of the humanities just learn how to analyze literary effects and to distinguish between different accounts of the foundations of knowledge.D.He thin ks Kronman’s remarks compromise the object its supposed praise.45.Which statement could best summarize this article?A.The arts and humanities fail to produce well-rounded citizens.B.The humanities won’t save us because humanities departments are too leftist.C.The humanities are expected to train character and nurture those intellectual andmoral habits for living a life with meaning.D.The humanities don’t bring about effects in the world but just give pleasure to those who enjoy them.Passage fourJust over a decade into the 21st century, women’s progress can be celebrated across a range of fields. They hold the highest political offices from Thailand to Brazil, Costa Rica to Australia. A woman holds the top spot at the International Monetary Fund; another won the Nobel Prize in economics. Self-made billionaires in Beijing, tech innovators in Silicon Valley, pioneering justices in Ghana—in these and countless other areas, women are leaving their mark.But hold the applause. In Saudi Arabia, women aren’t allowed to drive. In Pakistan, 1,000 women die in honor killings every year. In the developed world, women lag behind men in pay and political power. The poverty rate among women in the U.S. rose to 14.5% last year.To measure the state of women’s progress. Newsweek ranked 165countries, looking at five areas that affect women’s lives; treatment under the law, workforce participation, political power, and access to education and health care. Analyzing datafrom the United Nations and the World Economic Forum, among others, and consulting with experts and academics, we measured 28 factors to come up with our rankings.Countries with the highest scores tend to be clustered in the West, where gender discrimination is against the law, and equal rights are constitutionally enshrined. But there were some surprises. Some otherwise high-ranking countries had relatively low scores for political representation. Canada ranked third overall but 26th in power, behind countries such as Cuba and Burundi. Does this suggest that a woman in a nation’s top office translates to better lives for women in general? Not exactly.“Trying to quantify or measure the impact of women in politics is hard because in very few countries have there been enough women in politics to make a difference,” says Anne-Marie Goetz, peace and security adviser for U.N. Women.Of course, no index can account for everything. Declaring that one country is better than another in the way that it treats more than half its citizens means relying on broad strokes and generalities. Some things simply can’t be measured.And cross-cultural comparisons can t account for difference of opinion.Certain conclusions are nonetheless clear. For one thing, our index backs up a simple but profound statement made by Hillary Clinton at the recent Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit. “When we liberate the economic potential of women, we elevate the economic performance of communities, nations, and the world,”she said. “There’s a simulative effect that kicks in when women have greater access to jobs and the economic lives of our countries: Greater political stability. Fewer military conflicts. More food. More educational opportunity for children. By harnessing the economic potential of all women, we boost opportunity for all people.”46.What does the author think about women’s progress so far?A.It still leaves much to be desired.B.It is too remarkable to be measured.C.It has greatly changed women's fate.D.It is achieved through hard struggle.47.In what countries have women made the greatest progress?A.Where women hold key posts in government.B.Where women’s rights are protected by law.C.Where women’s participation in management is high.D.Where women enjoy better education and health care.48.What do Newsweek rankings reveal about women in Canada?A.They care little about political participation.B.They are generally treated as equals by men.C.They have a surprisingly low social status.D.They are underrepresented in politics.49.What does Anne-Marie Goetz think of a woman being in a nation's top office?A.It does not necessarily raise women's political awareness.B.It does not guarantee a better life for the nation's women.C.It enhances women's status.D.It boosts women's confidence.50.What does Hillary Clinton suggest we do to make the world a better place?A.Give women more political power.B.Stimulate women's creativity.C.Allow women access to education.D.Tap women's economic potential.Passage fiveThe idea that government should regulate intellectual property through copyrights and patents is relatively recent in human history, and the precise details of what intellectual property is protected for how long vary across nations and occasionally change. There are two standard sociological justifications for patents or copyrights: They reward creators for their labor, and they encourage greater creativity. Both of these are empirical claims that can be tested scientifically and could be false in some realms.Consider music. Star performers existed before the 20th century, such as Franz Liszt and Niccolo Paganini, but mass media produced a celebrity system promoting a few stars whose music was not necessarily the best or most diverse. Copyright provides protection for distribution companies and for a few celebrities, thereby helping to support the industry as currently defined, but it may actually harm the majority of performers. This is comparable to Anatole France's famous irony, "The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges." In theory, copyright covers the creations of celebrities and obscurities equally, but only major distribution companies have the resources to defend their property rights in court. In a sense, this is quite fair, because nobody wants to steal unpopular music, but by supporting the property rights of celebrities, copyright strengthens them as a class in contrast to anonymous musicians.Internet music file sharing has become a significant factor in the social lives of children, who download bootleg music tracks for their own use and to give as gifts to friends. If we are to believe one recent poll done by a marketing firm rather than social。

827华南理工大学2018 年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷(试卷上做答无效,请在答题纸上做答,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)科目名称:材料科学基础适用专业:材料科学与工程;材料工程(专硕)共8 页一、填空题:(每空0.5 分,共20 分)1、金属材料的(1 )和(2 )是决定材料性能的基本依据,金属材料的热处理是在明晰材料(3 )的前提下来设计热处理工艺。

2、晶界本身的强度与温度有关。

一般情况下,若晶粒的熔点为T,则当温度低于T/2 时,晶界强度(4 )晶内强度;当温度高于T/2 时,晶界强度(5 )晶内强度,晶粒形成粘滞流动,使材料形成蠕变变形。

3、碳钢经奥氏体化后经过冷至C 曲线中珠光体和马氏体线之间的区域保温将形成贝氏体,保温温度接近珠氏体转变温度时,形成的组织是(6 );保温温度接近马氏体转变温度时,形成的组织是(7 ),等温淬火热处理希望获得的组织是(8 )。

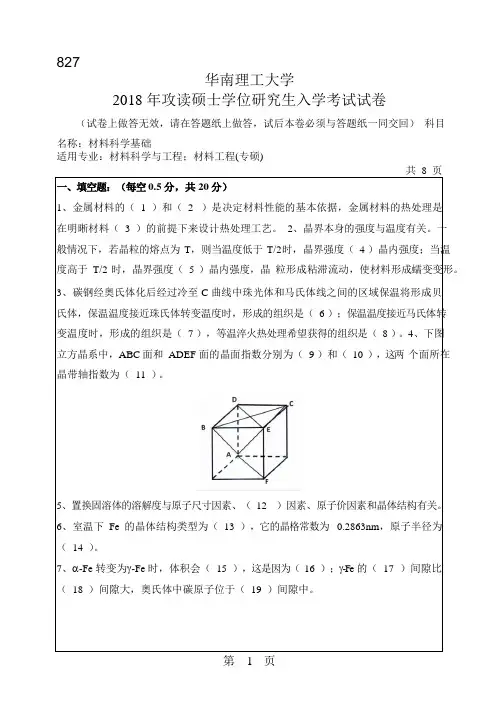

4、下图立方晶系中,ABC 面和ADEF 面的晶面指数分别为(9 )和(10 ),这两个面所在晶带轴指数为(11 )。

5、置换固溶体的溶解度与原子尺寸因素、(12 )因素、原子价因素和晶体结构有关。

6、室温下Fe 的晶体结构类型为(13 ),它的晶格常数为0.2863nm,原子半径为(14 )。

7、α-Fe 转变为γ-Fe 时,体积会(15 ),这是因为(16 );γ-Fe 的(17 )间隙比(18 )间隙大,奥氏体中碳原子位于(19 )间隙中。

8、组元A、B 在液态和固态都无限互溶,它们形成的相图称为(20 )相图。

如平衡分配系数K0<1,则可判断组元(21 )的熔点较高。

9、刃型位错既可以作(22 )运动,又可以作(23 )运动;而螺型位错只能作(24 )运动。

10、冷变形金属低温回复时,主要是(25 )密度下降;高温回复时,主要发生(26 )过程。

11、金属再结晶后的晶粒大小与(27 )、原始晶粒大小、(28 )和杂质等有关。

880华南理工大学2012年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷(请在答题纸上做答,试卷上做答无效,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)科目名称:分析化学适用专业:分析化学本卷满分:150分共 8 页一.单项选择题(共26题,每空1.5分,共计39分)1. 下列有关误差的论述中不正确的是:()A. 系统误差无法消除B. 随机误差由一些不确定的偶然因素造成C. 过失误差只能通过重做实验消除D. 试剂含少量被测组分会出现系统误差2. 关于t分布,下列描述不正确的是()A t分布的置信区间与测定值的精密度、次数和置信度密切相关B 测定值精密度越高,测定次数越低,t分布置信区间就越窄,平均值与真值越接近C 置信度越高,t分布置信区间就越宽,包括真值的可能性就越大D 当自由度大于20时,t分布与正态分布很相似3. 用0.05000 mol·L-1 HCl标准溶液滴定相同浓度的NaOH溶液时,分别采用甲基红和酚酞作为指示剂,比较两种方法的滴定误差()A 甲基橙作指示剂,滴定误差小B 酚酞作指示剂,滴定误差小C 两种方法滴定误差没有差别D 无法判断4. 铬黑T(EBT)是一种有机弱酸,它的pKa1=5.3,pKa2=6.3,Mg-EBT的lgK Mg-EBT=7.0,则在pH为6.0时lgK′Mg-EBT的值为()A 7.0B 6.3C 6.8D 6.55. 增加电解质的浓度,会使酸碱指示剂HIn(HIn ↔ H+ + In-)的理论变色点()A 变大B 变小C 不变D 无法判断6. 砷酸H3AsO4的pKa1, pKa2和pKa2分别为2.25,6.77和11.50。

当溶液的pH=7.00时,溶液中的存在形式正确的是()A [HAsO42-] > [H2AsO4-] > [H3AsO4]B [H2AsO4-] > [HAsO42-] > [AsO43-]C [AsO43-] > [H2AsO4-] > [HAsO42-]D [H2AsO4-] = [HAsO42-]7. 在配位滴定金属离子M时,不会对滴定突跃范围有影响的因素是()A 金属离子的初始浓度B 配合物的稳定常数C 配合物的浓度D 指示剂的浓度8. 加入1,10-邻二氮菲后,Fe3+/Fe2+电对的条件电极电势是()A 升高B 降低C 不变D 无法判断9. 用0.2000 mol⋅L-1 NaOH溶液滴定0.1000 mol⋅L-1磷酸溶液时,在滴定曲线上出现的突跃范围有()(酒石酸的pKa1=2.12,pKa2=7.20,pKa3=12.36)A 2个B 3个C 1个D 4个10. 在配位滴定中,下面描述正确的是()A 在任何pH下,指示剂的游离色(In)要与配合色(MIn)不同B 化学计量点前的突跃点的值与金属离子的浓度有关,而与条件稳定常数无关C 化学计量点前的突跃点的值与金属离子的浓度和条件稳定常数都有关D 化学计量点后的突跃点的值与金属离子的浓度有关,而与条件稳定常数无关11. 在非缓冲溶液中用EDTA滴定金属离子时,与使用缓冲溶液相比,到达化学计量点时,金属离子的浓度()A 降低B 与金属离子种类有关. C不变 D 升高12. 用As2O3标定I2溶液时,溶液应为()A 弱酸性B 弱碱性C 中性D 任何酸碱性13. 在氧化还原滴定中,外界条件对条件电极电位有重要的影响,下面关于氧化还原滴定描述正确的是()A 离子强度增加,条件电极电位降低B 副反应发生,条件电极电位升高C 离子强度增加,条件电极电位升高D 酸度增加,条件电极电位升高14. 某滴定反应,A7+ + 5B2+ = A2+ + 5B3+,欲使该反应的完全程度达到99.9%,两电对的条件电位至少应大于()A 0.12 VB 0.27 VC 0.21 VD 0.18 V15. 在酸性溶液中,用0.2 mol⋅L-1 KMnO4溶液滴定0.2 mol⋅L-1 Fe2+溶液,关于化学计量点描述正确的是()A 偏向化学计量点前的突跃点B 偏向化学计量点后的突跃点C 无法判定D在化学计量点前和后突跃点的中间16. 在沉淀滴定中,用佛尔哈德法测定I-时,先加铁铵钒指示剂,再加过量的AgNO3标准溶液,则分析结果()A 无影响B 偏高C 偏低D 无法判断17. 用离子选择性电极进行测定时,需要用磁力搅拌器搅拌溶液,原因是()A 减小浓差极化B 加快响应速度C 使电极表面保持干净D 降低电池内阻18. 对于电位滴定法,下面哪种说法错误的是()A 醋酸电位滴定是通过测量滴定过程中电池电动势的变化来确定滴定终点B 滴定终点位于滴定曲线斜率最小处C 电位滴定中,在化学计量点附近应该每加入0.1∼0.2 mL滴定剂就测量一次电动势D 除非要研究整个滴定过程,一般电位滴定只需准确测量和记录化学计量点前后1∼2 mL的电动势变化即可19. 邻二氮菲法测定铁时,没有加盐酸羟胺,则分析结果很可能会()A 无影响B 偏高C 无法判断D 偏低1. 10.5 mL 10-2.205 mol⋅L-1 H2SO4与1.598 mL pH为12.24的NaOH发生中和反应,反应后溶液中OH-的浓度为_ _(毎步先计算再修约)。

880华南理工大学2010年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷(请在答题纸上做答,试卷上做答无效,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)科目名称:分析化学适用专业:分析化学共页一.单项选择题(共25题,每空1.5分,共计37.5分)1. 在下列分析过程中,不会出现系统误差的是()A. 过滤时使用了定性滤纸,因而使最后的灰分加大B. 使用分析天平时,天平的零点稍有变动C. 试剂中含有少量的被测组分D. 以含量为99%的邻苯二甲酸氢钾作基准物标定碱溶液2. 下列数据不是四位有效数字的是()=0.1020 C.=10.26 D.Cu%[H+]B.pHA.=11.26[Pb2+]=12.28×10-43. 从精密度就可以判断分析结果可靠的前提是()平均偏差小 D.相对偏差系统误差小 C.A. 随机误差小B.小4. 通常定量分析中使用的试剂应为分析纯,其试剂瓶标签的颜色为()蓝色A. 绿色B. 红色C. 咖啡色D.5. 在下类洗干净的玻璃仪器中,使用时必须用待装的标准溶液或试液润洗的是()容量瓶A. 量筒B.锥形瓶C. 滴定管D.6. 下述情况,使分析结果产生负误差的是()A. 以盐酸标准溶液测定某碱样品,所用的滴定管未洗干净,滴定时内壁挂水珠;B. 测定H2C2O4⋅2H2O的摩尔质量时,草酸失去部分结晶水;C. 用于标定标准溶液的基准物质在称量时吸潮;D. 滴定速度过快,并在到达终点时立即读数7. H 3PO 4的pKa 1~pKa 3分别为2.12,7.20,12.4。

当H 3PO 4溶pH =7.5时溶液中的主要存在形式是( )A. [][]−−>2442HPO PO H B. [][]−−<2442HPO PO HC. D . [][−−=2442HPO PO H ][][]−−>2434HPO PO8. 酸碱滴定中选择指示剂的原则是( ) A. Ka=KHIn ;B. 指示剂的变色范围与等当点完全符合;C. 指示剂的变色范围全部或部分落入滴定的pH 突跃范围之内;D. 指示剂的变色范围应完全落在滴定的pH 突跃范围之内9. 在pH=10时,以铬黑T 为指示剂,用EDTA 滴定Ca 2+、Ma 2+总量时,Al 3+、Fe 3+等的存在会使得指示剂失效,这种现象称为指示剂的( ) A. 僵化 B. 封闭 C. 变质 D. 变性10. 已知某金属指示剂(HR )的pKa=3.5,其共轭酸型体为紫红色,其共轭碱型体为亮黄色。

626华南理工大学2018 年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷(试卷上做答无效,请在答题纸上做答,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)科目名称:英语综合水平测试适用专业:外国语言文学performances. Rather than playing tricks with alternatives presented to participants, we secretly altered the outcomes of their choices, and recorded how they react. For example, in an early study we showed our volunteers pairs of pictures of faces and asked them to choose the most attractive. In some trials, immediately after they made their choice, we asked people to explain the reasons behind their choices.Unknown to them, we sometimes used a double-card magic trick to secretly exchange one face for the other so they ended up with the face they did not choose. Common sense dictates that all of us would notice such a big change in the outcome of a choice. But the result showed that in 75 per cent of the trials our participants were blind to the mismatch, even offering “reasons” for their“choice”.We called this effect “choice blindness”, echoing change blindness,the phenomenon identified by psychologists where a remarkably large number of people fail to spot a major change in their environment. Recall the famous experiments where X asks Y for directions; while Y is struggling to help, X is switched for Z - and. Y fails to notice. Researchers are still pondering the full implications, but it does show how little information we use in daily life, and undermines the idea that we know what is going on around us.When we set out, we aimed to weigh in on the enduring, complicated debate about self-knowledge and intentionality. For all the intimate familiarity we feel we have with decision making, it is very difficult to know about it from the “inside”: one of the great barriers for scientific research is the nature of s ubjectivity.As anyone who has ever been in a verbal disagreement can prove, people tend to give elaborate justifications for their decisions, which we have every reason to believe are nothing more than rationalizations after the event. To prove such people wrong, though, or even provide enough evidence to change their mind, is an entirely different matter: who are you to say what my reasons are?But with choice blindness we drive a large wedge between intentions and actions in the mind. As our participants give us verbal explanations about choices they never made, we can show them beyond doubt - and prove it - that what they say cannot be true. So our experiments offer a unique window into confabulation (the story-telling we do to justify things after the fact) that is otherwise very difficult to come by. We can compare everyday explanations with those under lab conditions, looking for such things as the amount of detail in descriptions, how coherent the narrative is, the emotional tone, or even the timing or flow of the speech. Then we can create a theoretical framework to analyse any kind of exchange.This framework could provide a clinical use for choice blindness: for example, two of our ongoing studies examine how malingering might develop into truesymptoms, and how confabulation might play a role in obsessive-compulsive disorder.Importantly, the effects of choice blindness go beyond snap judgments. Depending on what our volunteers say in response to the mismatched outcomes of choices (whether they give short or long explanations, give numerical rating or labeling, and so on) we found this interaction could change their future preferences to the extent that they come to prefer the previously rejected alternative. This gives us a rare glimpse into the complicated dynamics of self-feedback (“I chose this, I publicly said so, therefore I must like it”), which we suspect lies behind the formation of many everyday preferences.We also want to explore the boundaries of choice blindness. Of course, it will be limited by choices we know to be of great importance in everyday life. Which bride or bridegroom would fail to notice if someone switched their partner at the altar through amazing sleight of hand? Yet there is ample territory between the absurd idea of spouse-swapping, and the results of our early face experiments.For example, in one recent study we invited supermarket customers to choose between two paired varieties of jam and tea. In order to switch each participant’s choice without them noticing, we created two sets of “magical” jars, with lids at both ends and a divider inside. The jars looked normal, but were designed to hold one variety of jam or tea at each end, and could easily be flipped over.Immediately after the participants chose, we asked them to taste their choice again and tell us verbally why they made that choice. Before they did, we turned over the sample containers, so the tasters were given the opposite of what they had intended in their selection. Strikingly, people detected no more than a third of all these trick trials. Even when we switched such remarkably different flavors as spicy cinnamon and apple for bitter grapefruit jam, the participants spotted less than half of all s witches.We have also documented this kind of effect when we simulate online shopping for consumer products such as laptops or cell phones, and even apartments. Our latest tests are exploring moral and political decisions, a domain where reflection and deliberation are supposed to play a central role, but which we believe is perfectly suited to investigating using choice blindness.Throughout our experiments, as well as registering whether our volunteers noticed that they had been presented with the alternative they did not choose, we also quizzed them about their beliefs about their decision processes. How did they think they would feel if they had been exposed to a study like ours? Did they think they would have noticed the switches? Consistently, between 80 and 90 per cent of people said that they believed they would have noticed something was wrong.Gervais, discovers a thing called “lying” and what it can get him. Within days, M ark is rich, famous, and courting the girl of his dreams. And because nobody knows what “lying” is? he goes on, happily living what has become a complete and utter farce.It’s meant to be funny, but it’s also a more serious commentary on us all. As Americans, we like to think we value the truth. Time and time again, public-opinion polls show that honesty is among the top five characteristics we want in a leader, friend, or lover; the world is full of sad stories about the tragic consequences of betrayal. At the same time, deception is all around us. We are lied to by government officials and public figures to a disturbing degree; many of our social relationships are based on little white lies we tell each other. We deceive our children, only to be deceived by them in return. And the average person, says psychologist Robert Feldman, the author of a new book on lying, tells at least three lies in the first 10 minutes of a conversation. “There’s always been a lot of lying,” says Feldman,whose new book, The Liar in Your Life, came out this month. “But I do think we’re seeing a kind of cultural shift where we’re lying more, it’s easier to lie, and in some ways it’s almost more acceptable.”As Paul Ekman, one of Feldman’s longtime lying colleagues and the inspiration behind the Fox IV series “Lie To Me” defines it,a liar is a person who “intends to mislead,”“deliberately,” without being asked to do so by the target of the lie. Which doesn’t mean that all lies are equally toxic: some are simply habitual –“My pleasure!”-- while others might be well-meaning white lies. But each, Feldman argues, is harmful, because of the standard it creates. And the more lies we tell, even if th ey’re little white lies, the more deceptive we and society become.We are a culture of liars, to put it bluntly, with deceit so deeply ingrained in our mind that we hardly even notice we’re engaging in it. Junk e-mail, deceptive advertising, the everyday p leasantries we don’t really mean –“It’s so great to meet you! I love that dress”– have, as Feldman puts it, become “a white noise we’ve learned to neglect.” And Feldman also argues that cheating is more common today than ever. The Josephson Institute, a nonprofit focused on youth ethics, concluded in a 2008 survey of nearly 30,000 high school students that “cheating in school continues to be rampant, and it’s getting worse.” In that survey, 64 percent of students said they’d cheated on a test during the past year, up from 60 percent in 2006. Another recent survey, by Junior Achievement, revealed that more than a third of teens believe lying, cheating, or plagiarizing can be necessary to succeed, while a brand-new study, commissioned by the publishers of Feldman’s book, shows that 18-to 34-year-olds--- those of us fully reared in this lying culture --- deceive more frequently than the general population.Teaching us to lie is not the purpose of Feldman’s book. His subtitle, in fact, is “the way to truthful relationships.” But if his book teaches us anything, it’s that we should sharpen our skills — and use them with abandon.Liars get what they want. They avoid punishment, and they win others’ affection. Liars make themselves sound smart and intelligent, they attain power over those of us who believe them, and they often use their lies to rise up in the professional world. Many liars have fun doing it. And many more take pride in getting away with it.As Feldman notes, there is an evolutionary basis for deception: in the wild, animals use deception to “play dead” when threatened. But in the modem world, the motives of our lying are more selfish. Research has linked socially successful people to those who are good liars. Students who succeed academically get picked for the best colleges, despite the fact that, as one recent Duke University study found, as many as 90 percent of high-schoolers admit to cheating. Even lying adolescents are more popular among their peers.And all it takes is a quick flip of the remote to see how our public figures fare when they get caught in a lie: Clinton keeps his wife and goes on to become a national hero. Fabricating author James Frey gets a million-dollar book deal. Eliot Spitzer’s wife stands by his side, while “Appalachian hiker” Mark Sanford still gets to keep his post. If everyone else is being rewarded for lying,don’t we need to lie, too, just to keep up?But what’s funny is that even as we admit to being liars, study after study shows that most of us believe we can tell when others are lying to us. And while lying may be easy, spotting a liar is far from it. A nervous sweat or shifty eyes can certainly mean a person’s uncomfortable, but it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re lying. Gaze aversion, meanwhile, has more to do with shyness than actual deception. Even polygraph machines are unreliable. And according to one study, by researcher Bella DePaulo, we’re only able to differentiate a lie from truth only 47 percent of the time, less than if we guessed randomly. “Basically everything we’ve heard about catching a liar is wrong,” says Feldman, who heads the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.Ekman, meanwhile, has spent decades studying micro-facial expressions of liars: the split-second eyebrow arch that shows surprise when a spouse asks who was on the phone; the furrowed nose that gives away a hint of disgust when a person says “I love you.” He’s trained everyone from the Secret Service to the TSA, and believes that with close study, it’s possible to identify those tiny emotions. The hard part, of course, is proving them. “A lot of times, it’s easier to believe,” says Feldman. “It takes a lot ofThere were, however, different explanations of this unhappy fact. Sean Pidgeon put the blame on “humanities departments who are responsible for the leftist politics that still turn people off.” Kedar Kulkarni blamed “the absence of a culture that privileges Learning to improve oneself as a human being.” Bethany blamed universities, which because they are obsessed with “maintaining funding” default on th e obligation to produce “well rounded citizens.” Matthew blamed no one,because i n his view the report’s priorities are just what they should be: “When a poet creates a vaccine or a tangible good that can be produced by a Fortune 500 company, I’ll rescind my comment.”Although none of these commentators uses the word, the issue they implicitly raise is justification. How does one justify funding the arts and humanities? It is clear which justifications are not available. You cannot argue that the arts and humanities are able to support themselves through grants and private donations. You cannot argue that a state’s economy will benefit by a new reading of “Hamlet.” You can’t argue -- well you can, but it won’t fly -- that a graduate who is well-versed in the history of Byzantine art will be attractive to employers (unless the employer is a museum). You can talk as Bethany does about “well rounded citizens,” but that ideal belongs to an earlier period, when the ability to refer knowledgeably to Shakespeare or Gibbon or the Thirty Years War had some cash value (the sociologists call it cultural capital). Nowadays, larding your conversations with small bits of erudition is more likely to irritate than to win friends and influence people.At one time justification of the arts and humanities was unnecessary because, as Anthony Kronman puts it in a new book, “Education’s End: Why Our Colleges and Universities Have Given Up on the Meaning of Life,” it was assumed that “a college was above all a place for the training of character, for the nurturing of those intellectual and moral habits that together from the basis for living the best life one can.”It followed that the realization of this goal required an immersion in the great texts of literature, philosophy and history even to the extent of memorizing them, for “to acquire a text by memory is to fix in one’s mind the image and example of the author and his subject.”It is to a version of this old ideal that Kronman would have us return, not because of a professional investment in the humanities (he is a professor of law and a former dean of the Yale Law School), but because he believes that only the humanities can address “the crisis of spirit we now confront” and “restore the wonder which those who have glimpsed the human condition have always felt, and which our scientific civilization, with its gadgets and discoveries, obscures.”As this last quotation makes clear, Kronman is not so much mounting a defense ofthe humanities as he is mounting an attack on everything else. Other spokespersons for the humanities argue for their utility by connecting them (in largely unconvincing ways) to the goals of science, technology and the building of careers. Kronman, however, identifies science, technology and careerism as impediments to living a life with meaning. The real enemies, he declares,are “the careerism that distracts from life as a whole” and “the blind acceptance of science and technology that disguise and deny our human condition.” These false idols,he says,block the way to understanding. We must turn to the humanities if we are to “meet the need for meaning in an age of vast but pointless powers,”for only the humanities can help us recover the urgency of “the question of what living is for.”The humanities do this, Kronman explains, by exposing students to “a range of texts that express with matchless power a number of competing answers to this question.” In the course of this program —Kronman calls it “secular humanism”—students will be moved “to consider which alternatives lie closest to their own evolving sense of self?” As they survey “the different ways of living that have been held up by different authors,” they will be encouraged “to enter as deeply as they can into the experiences, ideas, and values that give each its permanent appeal.” And not only would such a “revitalized humanism” contribute to the growth of the self,it “would put the conventional pieties of our moral and political world in question” and “bring what is hidden into the open — the highest goal of the humanities and the first responsibility of every teache r.”Here then is a justification of the humanities that is neither strained (reading poetry contributes to the state’s bottom line) nor crassly careerist. It is a stirring vision that promises the highest reward to those who respond to it. Entering into a conversation with the great authors of the western tradition holds out the prospect of experiencing “a kind of immortality” and achieving “a position immune to the corrupting powers of time.”Sounds great, but I have my doubts. Does it really work that way? Do the humanities ennoble? And for that matter, is it the business of the humanities, or of any other area of academic study, to save us?The answer in both cases, I think, is no. The premise of secular humanism (or of just old-fashioned humanism) is that the examples of action and thought portrayed in the enduring works of literature, philosophy and history can create in readers the desire to emulate them. Philip Sydney put it as well as anyone ever has when he asks (in “The Defense of Poesy” 1595), “Who reads Aeneas carrying old Anchises on his back that wishes not it was his fortune to perform such an excellent act?” Thrill to this picture of42.What does Anthony Kronman oppose in the process to strive for meaningful life?A.Secular humanism.B. Careerism.C. Revitalized humanismD. Cultural capital.43.Which of the following is NOT mentioned in this article?A.Sidney Carton killed himself.B.A new reading of Hamlet may not benefit economy.C.Faust was not willing to sell his soul.D.Philip Sydney wrote The Defense of Poesy.44.Which is NOT true about the author?A.At the time of writing, he has been in the field of the humanities for 45 years.B.He thinks the humanities are supposed to save at least those who study them.C.He thinks teachers and students of the humanities just learn how to analyze literary effects and to distinguish between different accounts of the foundations of knowledge.D.He thin ks Kronman’s remarks compromise the object its supposed praise.45.Which statement could best summarize this article?A.The arts and humanities fail to produce well-rounded citizens.B.The humanities won’t save us because humanities departments are too leftist.C.The humanities are expected to train character and nurture those intellectual andmoral habits for living a life with meaning.D.The humanities don’t bring about effects in the world but just give pleasure to those who enjoy them.Passage fourJust over a decade into the 21st century, women’s progress can be celebrated across a range of fields. They hold the highest political offices from Thailand to Brazil, Costa Rica to Australia. A woman holds the top spot at the International Monetary Fund; another won the Nobel Prize in economics. Self-made billionaires in Beijing, tech innovators in Silicon Valley, pioneering justices in Ghana—in these and countless other areas, women are leaving their mark.But hold the applause. In Saudi Arabia, women aren’t allowed to drive. In Pakistan, 1,000 women die in honor killings every year. In the developed world, women lag behind men in pay and political power. The poverty rate among women in the U.S. rose to 14.5% last year.To measure the state of women’s progress. Newsweek ranked 165countries, looking at five areas that affect women’s lives; treatment under the law, workforce participation, political power, and access to education and health care. Analyzing datafrom the United Nations and the World Economic Forum, among others, and consulting with experts and academics, we measured 28 factors to come up with our rankings.Countries with the highest scores tend to be clustered in the West, where gender discrimination is against the law, and equal rights are constitutionally enshrined. But there were some surprises. Some otherwise high-ranking countries had relatively low scores for political representation. Canada ranked third overall but 26th in power, behind countries such as Cuba and Burundi. Does this suggest that a woman in a nation’s top office translates to better lives for women in general? Not exactly.“Trying to quantify or measure the impact of women in politics is hard because in very few countries have there been enough women in politics to make a difference,” says Anne-Marie Goetz, peace and security adviser for U.N. Women.Of course, no index can account for everything. Declaring that one country is better than another in the way that it treats more than half its citizens means relying on broad strokes and generalities. Some things simply can’t be measured.And cross-cultural comparisons can t account for difference of opinion.Certain conclusions are nonetheless clear. For one thing, our index backs up a simple but profound statement made by Hillary Clinton at the recent Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit. “When we liberate the economic potential of women, we elevate the economic performance of communities, nations, and the world,”she said. “There’s a simulative effect that kicks in when women have greater access to jobs and the economic lives of our countries: Greater political stability. Fewer military conflicts. More food. More educational opportunity for children. By harnessing the economic potential of all women, we boost opportunity for all people.”46.What does the author think about women’s progress so far?A.It still leaves much to be desired.B.It is too remarkable to be measured.C.It has greatly changed women's fate.D.It is achieved through hard struggle.47.In what countries have women made the greatest progress?A.Where women hold key posts in government.B.Where women’s rights are protected by law.C.Where women’s participation in management is high.D.Where women enjoy better education and health care.48.What do Newsweek rankings reveal about women in Canada?A.They care little about political participation.B.They are generally treated as equals by men.C.They have a surprisingly low social status.D.They are underrepresented in politics.49.What does Anne-Marie Goetz think of a woman being in a nation's top office?A.It does not necessarily raise women's political awareness.B.It does not guarantee a better life for the nation's women.C.It enhances women's status.D.It boosts women's confidence.50.What does Hillary Clinton suggest we do to make the world a better place?A.Give women more political power.B.Stimulate women's creativity.C.Allow women access to education.D.Tap women's economic potential.Passage fiveThe idea that government should regulate intellectual property through copyrights and patents is relatively recent in human history, and the precise details of what intellectual property is protected for how long vary across nations and occasionally change. There are two standard sociological justifications for patents or copyrights: They reward creators for their labor, and they encourage greater creativity. Both of these are empirical claims that can be tested scientifically and could be false in some realms.Consider music. Star performers existed before the 20th century, such as Franz Liszt and Niccolo Paganini, but mass media produced a celebrity system promoting a few stars whose music was not necessarily the best or most diverse. Copyright provides protection for distribution companies and for a few celebrities, thereby helping to support the industry as currently defined, but it may actually harm the majority of performers. This is comparable to Anatole France's famous irony, "The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges." In theory, copyright covers the creations of celebrities and obscurities equally, but only major distribution companies have the resources to defend their property rights in court. In a sense, this is quite fair, because nobody wants to steal unpopular music, but by supporting the property rights of celebrities, copyright strengthens them as a class in contrast to anonymous musicians.Internet music file sharing has become a significant factor in the social lives of children, who download bootleg music tracks for their own use and to give as gifts to friends. If we are to believe one recent poll done by a marketing firm rather than social。

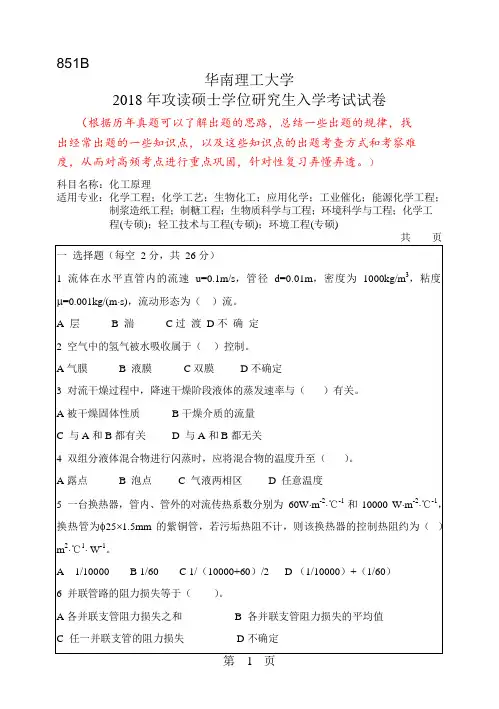

851B华南理工大学2018 年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷(根据历年真题可以了解出题的思路,总结一些出题的规律,找出经常出题的一些知识点,以及这些知识点的出题考查方式和考察难度,从而对高频考点进行重点巩固,针对性复习弄懂弄透。

)科目名称:化工原理适用专业:化学工程;化学工艺;生物化工;应用化学;工业催化;能源化学工程;制浆造纸工程;制糖工程;生物质科学与工程;环境科学与工程;化学工程(专硕);轻工技术与工程(专硕);环境工程(专硕)共页一选择题(每空2 分,共26 分)1流体在水平直管内的流速u=0.1m/s,管径d=0.01m,密度为1000kg/m3,粘度μ=0.001kg/(m⋅s),流动形态为()流。

A 层B 湍C 过渡D 不确定2空气中的氢气被水吸收属于()控制。

A 气膜B 液膜C 双膜D 不确定3对流干燥过程中,降速干燥阶段液体的蒸发速率与()有关。

A 被干燥固体性质B 干燥介质的流量C 与A 和B 都有关D 与A 和B 都无关4双组分液体混合物进行闪蒸时,应将混合物的温度升至()。

A 露点B 泡点C 气液两相区D 任意温度5一台换热器,管内、管外的对流传热系数分别为60W⋅m-2⋅℃-1 和10000 W⋅m-2⋅℃-1,换热管为φ25⨯1.5mm 的紫铜管,若污垢热阻不计,则该换热器的控制热阻约为()m2⋅℃1⋅ W-1。

A 1/10000B 1/60C 1/(10000+60)/2D (1/10000)+(1/60)6并联管路的阻力损失等于()。

A 各并联支管阻力损失之和B 各并联支管阻力损失的平均值C 任一并联支管的阻力损失D 不确定7孔板流量计的孔流系数是C0,当Re 增大时,孔流系数()。

A 先减小,当Re 增加到一定值时,C0 保持为某定值B 增大C 减小D 不确定8翅片管加热器一般用于()。

A 两侧均为液体B 两侧流体均有相变化C 一侧为液体沸腾,一侧为高温液体D 一侧为气体,一侧为蒸汽冷凝9影响塔设备操作弹性的因素有()。

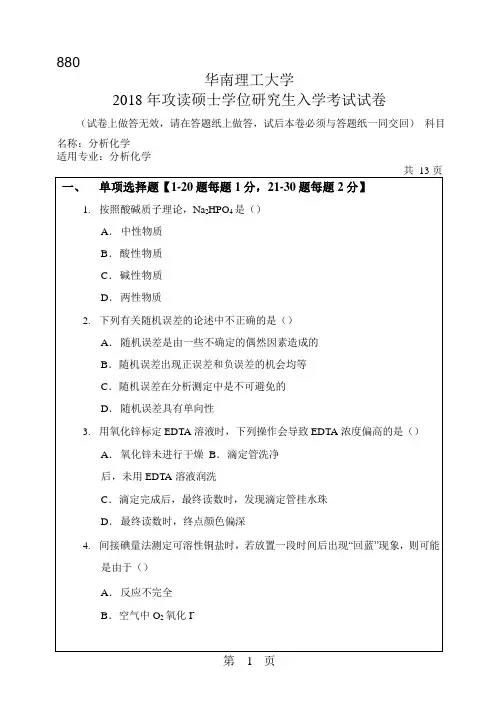

880华南理工大学2018 年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷(试卷上做答无效,请在答题纸上做答,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)科目名称:分析化学适用专业:分析化学共13 页一、单项选择题【1-20 题每题1 分,21-30 题每题2 分】1. 按照酸碱质子理论,Na2HPO4是()A.中性物质B.酸性物质C.碱性物质D.两性物质2. 下列有关随机误差的论述中不正确的是()A.随机误差是由一些不确定的偶然因素造成的B.随机误差出现正误差和负误差的机会均等C.随机误差在分析测定中是不可避免的D.随机误差具有单向性3. 用氧化锌标定EDTA 溶液时,下列操作会导致EDTA 浓度偏高的是()A.氧化锌未进行干燥B.滴定管洗净后,未用EDTA 溶液润洗C.滴定完成后,最终读数时,发现滴定管挂水珠D.最终读数时,终点颜色偏深4. 间接碘量法测定可溶性铜盐时,若放置一段时间后出现“回蓝”现象,则可能是由于()A.反应不完全B.空气中O2氧化I-C.氧化还原反应速度慢D.淀粉指示剂变质5. 摩尔法测定Cl-,控制溶液pH=4.0,其滴定终点将()A.不受影响B.提前到达C.推迟到达D.刚好等于化学计量点6. 用高锰酸钾法测定铁,一般使用硫酸而不是盐酸调节酸度,其主要原因是()A.盐酸有挥发性B.硫酸可以起催化作用C.盐酸强度不够D.Cl-可能与KMnO4 反应7. AgCl 在0.01mol/L HCl 中溶解度比在纯水中小,是()的结果。

A.共同离子效应B.酸效应C.盐效应D.配位效应8. 氧化还原反应的条件平衡常数与下列哪个因素无关()A.氧化剂与还原剂的初始浓度B.氧化剂与还原剂的副反应系数C.两个半反应电对的标准电位D.反应中两个电对的电子转移数9. pH 玻璃电极使用前必须在水中浸泡,其主要目的是()A.清洗电极B.活化电极C.校正电极D.清除吸附杂质10. 用氟离子选择性电极测定水中(含有微量的Fe3+、Al3+、Ca2+、Cl-)的氟离子时,应选用的离子强度调节缓冲溶液为()A.0.1 mol/L KNO3B.0.1 mol/L NaOHC.0.1 mol/L 柠檬酸钠(pH 调至5-6)D.0.1 mol/L NaAc(pH 调至5-6)11. 在正相色谱柱上分离含物质1,2,3 的混合物,其极性大小依次为:物质1>物质2>物质3,其保留时间t 的相对大小依次为()A.t1>t2>t3B.t1<t2<t3C.t2>t1>t3D.t2<t1<t312. 常用于评价色谱分离条件选择是否适宜的参数是()A.理论塔板数B.塔板高度C.分离度D.死时间13. 在符合朗伯-比尔定律的范围内,有色物质的浓度、最大吸收波长、吸光度三者的关系是()A.增加、增加、增加B.减小、不变、减小C.减小、增加、增加D.增加、不变、减小14. 下列仪器分析方法中适宜采用内标法定量的是()A. 紫外-可见分光光度法B. 原子吸收光谱法C. 色谱分析法D. 极谱分析法15. 用0.10 mol/L NaOH 滴定同浓度HAc(pKa=4.74)的pH 突跃范围为7.7~9.7。

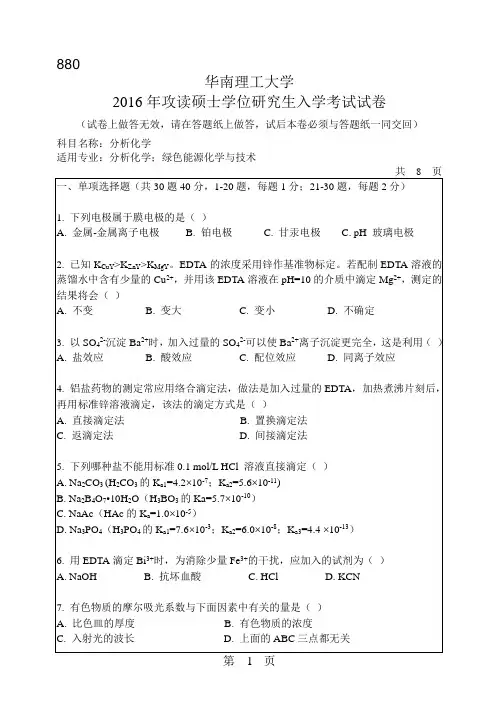

880

华南理工大学

2016年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷

(试卷上做答无效,请在答题纸上做答,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)

科目名称:分析化学

适用专业:分析化学;绿色能源化学与技术

溶解度随Cl-浓度增大而减小的原因是:溶解度随Cl-浓度增大而增大的原因是:

880

华南理工大学

2018年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷

(试卷上做答无效,请在答题纸上做答,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)

科目名称:分析化学

适用专业:分析化学

根据上面的描述,回答下面的问题:

弱键相互作用力有哪些?【4分】

在含钴离子的中性溶液中,为什么包裹有谷胱甘肽的金纳米粒子能实现

自组装?通过什么弱键?其原理是什么?【6分】。

880

华南理工大学

2018年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷

(试卷上做答无效,请在答题纸上做答,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)

科目名称:分析化学

适用专业:分析化学

根据上面的描述,回答下面的问题:

弱键相互作用力有哪些?【4分】

在含钴离子的中性溶液中,为什么包裹有谷胱甘肽的金纳米粒子能实现

自组装?通过什么弱键?其原理是什么?【6分】

880

华南理工大学

2016年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷

(试卷上做答无效,请在答题纸上做答,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回)

科目名称:分析化学

适用专业:分析化学;绿色能源化学与技术

溶解度随Cl-浓度增大而减小的原因是:溶解度随Cl-浓度增大而增大的原因是:

第 5 页。

880华南理工大学2008年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷(试卷上做答无效,请在答题纸上做答,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回) 科目名称:分析化学适用专业:分析化学 共 7 页一.单项选择题(共20题,每空1.5分,共计30分)1. 甲乙丙丁四人同时分析一矿物中的含硫量,取样均为3.5 g ,下列哪份报告的数据合理( )A. 甲:0.04%B. 乙:0.042%C. 丙:0.0421%D. 丁:0.04211%2. 消除分析方法中存在的系统误差,可以采用的方法是( )A. 增大试样称量质量B. 用两组测量数据对照C. 增加测定次数D. 进行仪器校准3. 浓度为c HCl (mol ⋅L -1)的HCl 和c NaOH (mol ⋅L -1)的NaOH 混合溶液的质子平衡方程为( )A.B. [][]HCl c OH H +=−+[][]HCl NaOH c OH c H +=+−+C. [][]−+=+OH c H NaOHD. [][]NaOH HCl c c OH H ++=−+4. 某二元弱酸H 2B 的pKa 1和pKa 2为3.00和7.00,pH=3.00的0.20 mol ⋅L -1H 2B 溶液中,HB -的平衡浓度为( )A. 0.15 mol ⋅L -1B. 0.050 mol ⋅L -1C. 0.10 mol ⋅L -1D. 0.025 mol ⋅L -15. 以H 2C 2O 4⋅2H 2O 作基准物质,用来标定NaOH 溶液的浓度,现因保存不当,草酸失去了部分结晶水,若用此草酸标定NaOH 溶液,NaOH 的浓度将( )A. 偏低B. 偏高C. 无影响D. 不能确定6. 以EDTA 为滴定剂,下列叙述中哪项是错误的( )A. 在酸度较高的溶液中,可能形成MHY 络合物;B. 在碱度较高的溶液中,可能形成MOHY 络合物;C. 不论形成MHY 或MOHY 均有利于滴定反应;D. 不论形成MHY 或MOHY 均不有利滴定反应7. 用EDTA 法测定Fe 3+、Al 3+、Ca 2+、Mg 2+混合溶液中的Ca 2+、Mg 2+的含量,如果Fe 3+、Al 3+的含量较大,通常采取什么方法消除其干扰( )A. 沉淀分离法B. 控制酸度法C. 络合掩蔽法D. 溶剂萃取法8. 在含有Fe 3+和Fe 2+的溶液中,加入下列何种溶液,Fe 3+/Fe 2+电对的电位将升高(不考虑离子强度影响)( )A. 邻二氮菲B. HClC. H 3PO 4D. H 2SO 49. 已知1 mol.l -1 H 2SO 4溶液中,,,在此条件下用KMnO V 45.1'Mn /MnO 24=ϕθ+−V 68.0'Fe /Fe 23=ϕθ++4标准溶液滴定Fe 2+,其化学计量点的电位为( )A. 0.38 VB. 0.73 VC. 0.89 VD. 1.32 V10. 佛尔哈德法测定时的介质条件为( )A. 稀硝酸介质B. 弱酸性或中性C. 和指示剂的PKa 有关D. 没有什么限制11. 在以下各类滴定中,当滴定剂与被滴物质均增大10倍时,滴定突跃范围增大最多的是( )A. NaOH 滴定HAcB. EDTA 滴定Ca 2+C. K 2Cr 2O 7滴定Fe 2+D. AgNO 3滴定Cl -12. 在沉淀过程中,与待测离子半径相近的杂质离子常与待测离子一起与沉淀剂形成( )。

-m2 V 1 .线温等为CG线 虚 中图’hu la-'P Lw h -G R 俨l i l --L rn Ef $4过Ch !-OL W ’r E’1程 判是Md 川热吸 口玉 咄L 还’过 体- 线热气 ,肉强 吸 阳山 l 姥 色 刷 拙J :i线 柑川 机川川执…M热勾 虚 两 这 断 · 队 放 但 吸 F F 吸 程中 惆 热程 程 放 叩2阳-1 .860华南理工大学2018 年攻读硕士学位研究生入学考试试卷( 试卷上做答无效 ,请在答题纸上做答 ,试后本卷必须与答题纸一同交回〉 。

d科目名称 :普通物理(含力 、热、电、光学) 适用专业 :理论物理:凝聚态物理 :声学:光学;材料科学与工程 :物理电子学 :共 f 页 。

;7' v材料工程(专硕)一、选择题 (共 48 分,每题 4 分〉l 、几个不同倾角的光滑斜面 ,有共同的底边 ,顶点也在同一坚直面上 .若使一物倒( 视为质点) 从斜面上端由静止滑到下端的时间最短 ,则斜面的倾角应选(A) 60。

. (B) 45° . (C) 30。

.(D) 15。

.[]2、某物体的运动规律为 d v / d t = -k v 勺 ,式中的 k 为大于零的常量 .当t = O 时,初速为 Vo ,则速度 U 与时间 t 的函数关系是(D) abc 过程和 def 过程都放热. []6、一定量的理想气体经历 二cb 过程时吸热500 J. 则经历 cbda 过程时 ,吸热为(A ) 马200 J. (B ) 一700 J.p (×105 Pa)(A) v=kt 2 叫(C) -400 J .(D) 700 J.。

V ( 10-3 m3)1 kt2 1(C) 一=--::-- +一’ , U 二L Vo3、一质量为 m 的质点,在半径为 R 的半球形容器中 ,由静止开始自边缘上的 A 点滑 下,到达最低点 B 时,它对容器的正压力为N. 则质点自 A℃!57[ ]47、一铜板厚度为 D= l .OO mm ,放罩在磁感强度为 B= 1.35 T 的匀强磁场中,磁场方|向垂直于导体的侧表面 ,如图所示 ,现测得铜板上下两面电势差为 V=1.10×10 5 v ,己B 知铜板中自 由电子数密度 n =4.20 ×102s m 3, 滑到 B 的过程中,摩擦力对其作的功为A(A) 护(N 训 电子电荷 e=l.60 ×10-19 c,则此铜板中的电 歹争叶阳一mg ) .(D)i R( N 切)[]8、如图所示 .一电荷为 q 的点电荷,以匀角速度ω作圆周 运动 ,圆周的半径为 R. 设 t = O 时 q 所在点的坐标为 xo = R , 4、如图,两木块质量为 m1 和 叫,由一轻弹簧连接,放在光滑水平桌面上 ,先使网木块靠近而将弹簧压紧 ,然后由静止释放 .若在弹簧伸长到原长时,m1 的速率为 V1,则弹簧原来在压缩状态时所具有的势能是o = O ,以T , ] 分别表示 x 轴和 y 轴上的单位矢景 ,则圆心处 点的位移电流密度为 :1 m1 + m2 2总 二点点达-2.口._L 二sm w t Iqw『x(i )(A) 一m 1V12(B) (A)(B)一一一τcos mt J2 m1 4 π R 24πRqw -qw-1 m1 + m2 z(C)一一k(D)一 丁(sin wti - c os mtj) (C)三(m1 + m2 ) V 1 .(D ) -m1V 1 . 4πR 22 m24πR第页第 2 页\Y i u )-E Er 饨A ~「, D G的一市民川r E F图nu 品UF 历经。