Viral load in children with congenital CMV infection identified on newborn hearing screening

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:455.13 KB

- 文档页数:5

英语六级作文给孩子更多的空间Raising children in today's fast-paced and highly competitive world can be a challenging task for parents. In a society that often values academic achievements and extracurricular activities above all else, it is crucial to recognize the importance of providing children with more space to grow and develop at their own pace. This essay will explore the benefits of giving children more space and the ways in which parents can create an environment that fosters their natural curiosity and creativity.One of the primary reasons why children need more space is to allow for the development of their individuality. Each child is unique, with their own interests, talents, and learning styles. By imposing a rigid set of expectations or a one-size-fits-all approach, parents may inadvertently stifle their child's natural inclinations and hinder their ability to explore their own passions. Providing children with more space gives them the freedom to discover their own strengths, pursue their interests, and develop a strong sense of self-identity.Moreover, giving children more space can have a profound impacton their mental and emotional well-being. In a world where children are often subjected to intense academic pressure and extracurricular demands, it is not uncommon for them to experience high levels of stress and anxiety. This can lead to burnout, diminished self-esteem, and even mental health issues. By allowing children more space to play, explore, and simply be themselves, parents can help alleviate this stress and create an environment that promotes emotional resilience and overall well-being.Another key benefit of giving children more space is the opportunity for them to develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills. When children are not constantly directed or micromanaged, they are more likely to engage in independent learning and explore solutions to problems on their own. This process of self-discovery and problem-solving can foster the development of essential life skills that will serve them well in the future, such as creativity, resourcefulness, and the ability to think critically.Furthermore, providing children with more space can enhance their social and emotional development. When children have the freedom to interact with their peers without constant adult supervision, they learn to navigate social situations, develop empathy, and build meaningful relationships. This type of independent social exploration can be crucial for the development of important social skills, such as communication, conflict resolution, and collaboration.Of course, the concept of giving children more space does not mean abandoning them entirely or neglecting their needs. Parents still have a vital role to play in guiding and supporting their children, but the focus should be on creating a nurturing environment that encourages autonomy and self-discovery. This can be achieved through a variety of strategies, such as setting clear boundaries while allowing for flexibility, fostering open communication, and trusting children to make age-appropriate decisions.One effective way for parents to create more space for their children is by reducing the number of scheduled activities and allowing for unstructured playtime. This can involve providing children with access to a variety of toys and materials that encourage open-ended exploration, as well as encouraging them to engage in imaginative play and outdoor activities. By reducing the pressure of constant scheduling and allowing children to direct their own play, parents can help foster a sense of creativity, independence, and self-expression.Another important aspect of giving children more space is to encourage them to take risks and make mistakes. In a society that often values perfection and achievement above all else, children may be hesitant to try new things or step outside their comfort zones for fear of failure. By creating an environment where mistakes are seenas opportunities for learning and growth, parents can help children develop the resilience and problem-solving skills they need to navigate the challenges of life.Additionally, parents can provide children with more space by involving them in decision-making processes and encouraging them to express their opinions and preferences. This can include allowing children to have a say in family activities, meal planning, or even the organization of their own spaces. By giving children a voice and empowering them to make choices, parents can foster a sense of agency and responsibility that will serve them well in the future.Of course, the implementation of these strategies may vary depending on the age and developmental stage of the child. Younger children may require more guidance and structure, while older children may benefit from increased independence and autonomy. It is important for parents to strike a balance and adapt their approach as their children grow and mature.In conclusion, giving children more space is essential for their overall development and well-being. By fostering an environment that encourages independence, creativity, and self-discovery, parents can help their children develop the skills and resilience they need to thrive in the 21st century. While it may require a shift in mindset and a willingness to let go of some control, the long-term benefits ofproviding children with more space are undeniable. By embracing this approach, parents can empower their children to become confident, self-assured individuals who are equipped to navigate the challenges of the modern world.。

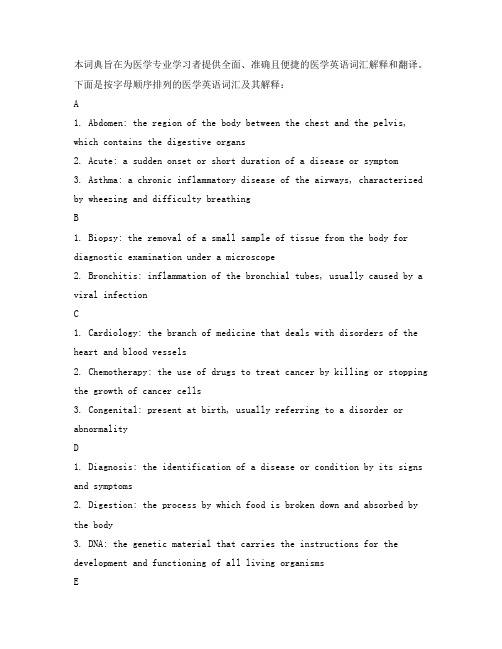

本词典旨在为医学专业学习者提供全面、准确且便捷的医学英语词汇解释和翻译。

下面是按字母顺序排列的医学英语词汇及其解释:A1. Abdomen: the region of the body between the chest and the pelvis, which contains the digestive organs2. Acute: a sudden onset or short duration of a disease or symptom3. Asthma: a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways, characterized by wheezing and difficulty breathingB1. Biopsy: the removal of a small sample of tissue from the body for diagnostic examination under a microscope2. Bronchitis: inflammation of the bronchial tubes, usually caused by a viral infectionC1. Cardiology: the branch of medicine that deals with disorders of the heart and blood vessels2. Chemotherapy: the use of drugs to treat cancer by killing or stopping the growth of cancer cells3. Congenital: present at birth, usually referring to a disorder or abnormalityD1. Diagnosis: the identification of a disease or condition by its signs and symptoms2. Digestion: the process by which food is broken down and absorbed by the body3. DNA: the genetic material that carries the instructions for the development and functioning of all living organismsE1. Electrocardiogram (ECG): a test that measures the electrical activity of the heart2. Endocrine system: the system of glands that produce and release hormones into the bloodstream3. Epilepsy: a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures F1. Fever: an elevated body temperature, usually as a response to infection or inflammation2. Fracture: a break or crack in a boneG1. Gastroenterology: the branch of medicine that deals with disorders of the digestive system2. Genetic: relating to genes and inheritanceH1. Hypertension: high blood pressure2. Hypothyroidism: a condition in which the thyroid gland does not produce enough thyroid hormoneI1. Immunity: the body's ability to resist and fight off infections and diseases2. Infection: the invasion and multiplication of microorganisms in body tissues, resulting in damage and diseaseJNo relevant vocabulary found.KNo relevant vocabulary found.L1. Lymphocytes: a type of white blood cell involved in the immune response2. Lymphoma: a cancer of the lymphatic systemM1. Mammogram: an X-ray of the breast used for the early detection of breast cancer2. Menopause: the cessation of menstrual periods in women, usually occurring around the age of 50N1. Nephrology: the branch of medicine that deals with disorders of the kidneys2. Neurology: the branch of medicine that deals with disorders of the nervous systemO1. Ophthalmology: the branch of medicine that deals with disorders of the eye2. Osteoporosis: a condition characterized by decreased bone density and increased risk of fracturesP1. Pathology: the branch of medicine that deals with the study of disease and its causes2. Pediatrics: the branch of medicine that deals with the medical care of infants, children, and adolescentsQNo relevant vocabulary found.R1. Radiology: the branch of medicine that deals with the use of medical imaging to diagnose and treat diseases2. Rheumatology: the branch of medicine that deals with disorders of the joints and connective tissuesS1. Surgery: the medical specialty that uses operative techniques totreat diseases, injuries, or other conditions2. Symptom: a subjective indication of a disease or condition, experienced by the patientT1. Thyroid: a gland located in the neck that produces hormones involved in regulating metabolism2. Tumor: an abnormal growth of cells, which may be benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous)UNo relevant vocabulary found.VNo relevant vocabulary found.WNo relevant vocabulary found.XNo relevant vocabulary found.YNo relevant vocabulary found.ZNo relevant vocabulary found.以上为《医学专业英语词典》内容,希望本词典能够为医学专业学习者提供准确、详细的医学英语词汇解释和翻译,帮助其更好地理解和学习医学知识。

儿科常见疾病中英文对照早产儿(未成熟儿) Preterm infant; Premature infant足月儿Term infant过期产儿(过熟儿) Post-term infant (Postmature infant) 小于胎龄儿Small for gestational age infant足月小样儿Small for date infant超低出生体重儿extremely birth weight,ELBW极低出生体重儿very low birth weight infant;VLBWI 低出生体重儿low birth weight infant巨大儿Macrosomia新生儿窒息Neonatal asphyxia缺氧缺血性脑病hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy新生儿颅内出血intracranial hemorrhage of newborn羊水及胎粪吸入综合征aspiration of amniotic fluid and meconium syndrome新生儿呼吸窘迫综合征Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, NRDS新生儿黄疸neonatal jaundice新生儿高胆红素血症Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia;hyperbilirubinemia of newborn新生儿生理性黄疸Neonatal physiologic jaundice新生儿溶血病hemolytic disease of the newborn 新生儿出血症hemorrhagic disease of newborn新生儿肺出血Neonatal pneumorrhagia新生儿感染Neonatal infection新生儿败血症Neonatal septicemia新生儿感染性肺炎Neonatal infectious pneumonia脐炎Omphalitis巨细胞病毒感染cytomegalovirus infection新生儿呕吐Vomiting in newborn鹅口疮Thrush新生儿硬肿症scleredema neonatorum新生儿水肿edema neonatorum新生儿低钙血症neonatal hypocalcemia;NHC新生儿低血糖症neonatal hypoglycemia脐疝exumbilication;UH;umbilical hernia 新生儿红斑erythema neonatorum婴幼儿营养不良infantile malnutrition蛋白质-能量营养不良protein-energy malnutrition, EPM 维生素D缺乏性佝偻病rickets of vitamin D-deficiency维生素D缺乏性手足搐搦症tetany of vitamin D-deficiency支气管哮喘bronchial asthma急性荨麻疹acute urticaria丘疹样荨麻疹papular urticaria药疹drug rash;风湿热RF;;rheumatic fever幼年型类风湿病Juvenile rheumatoid disease,JRD;Still disease系统性红斑狼疮SLE;systemic lupus erythematosus 过敏性紫癜Henoch-Schonlein syndrome; AP;anaphylactic purpura; allergicpurpura,皮肤粘膜淋巴结综合征Kawasaki's disease; muco-cutaneouslymphnode syndrome; MLNS 麻疹Measles风疹Rubella; German measles幼儿急疹exanthem subitum; roseolainfantilis; roseola infantum 单纯疱疹herpes simplex水痘chicken pox;chickenpox;varicella流行性感冒epidemic influenza;流行性腮腺炎epidemic parotitis; mumps病毒性脑炎VE;viral encephalitis病毒性脑膜脑炎viral meningocephalitis流行性乙型脑炎epidemic type B encephalitis;病毒性肝炎VH;viral hepatitis;virus hepatitis急性感染性多发性神经根炎acute infectious polyradiculoneuritis 传染性单核细胞增多症infectious monocytosis,infectiousmononucleosis急性传染性淋巴细胞增多症acute infectious lymphocytosis;AIL 细菌性痢疾bacillary dysentery伤寒typhoid; typhoid fever副伤寒paratyphoid; paratyphoid fever破伤风tetanus百日咳pertussis; whooping cough;WC化脓性脑膜炎purulent meningitis;suppurative meningitis流行性脑脊髓膜炎epidemic cerebrospinal meningitis猩红热scarlet fever;SF败血症septicemia; septicoemia; sepsis脓毒败血症septicopyaemia; septicopyemia原发性肺结核primary pulmonary tuberculosis原发综合征primary complex支气管淋巴结结核tuberculosis of bronchial lymphnodes1结核性胸膜炎tuberculous pleurisy亚急性血行播散型肺结核subacute hematogenous pulmonary tuberculosis结核性脑膜炎TBM;TM;tubercular meningitis;tuberculous meningitis蛔虫病ascariasis蛲虫病enterobiasis;oxyuria; pinworm;钩虫病ancylostomiasis; hookworm diseas 疟疾malaria; Cameroon fever;急性鼻窦炎acute sinusitis急性上呼吸道感染acute upper respiratory infections 疱疹性咽峡炎Herpangina;HA; herpetic angina 咽结膜热Pharyngoconjunctival fever, PCF 急性鼻咽炎acute nasopharyngitis急性咽炎acute pharyngitis急性扁桃体炎acute tonsillitis先天性喉喘鸣congenital laryngealstridor哮吼综合征Croup syndrome急性感染性喉炎acute infectious laryngitis急性支气管炎Acute bronchitis喘息样支气管炎asthmatoid bronchitis毛细支气管炎bronchiolitis大叶性肺炎lobar pneumonia支气管肺炎bronchopneumonia间质性肺炎interstitial pneumonia支原体肺炎(原发性非典型肺炎) mycoplasmal pneumonia (primary atypical pneumonia)喘憋性肺炎(流行性毛细支气管炎) epidemic asthmatic suffocating pneumonia( epidemic bronchiolitis)巨细胞病毒肺炎cytomegalovirus pneumonia鹅口疮Thrush; muguet; mycotic stomatitis;疱疹性口炎herpetic stomatitis急性球菌性口炎acute coccus stomatis消化功能紊乱disorders of digestive function神经性厌食anorexia nervosa再发性(周期性)呕吐recurrent vomiting(cyclic vomiting)再发性腹痛recurrent abdominal pain,RAP肠痉挛colic;enterospasm婴幼儿腹泻infantile diarrhea秋季腹泻rotavirus enteritis迁延性腹泻persistent diarrhea慢性细菌性腹泻chronic bacillary diarrhea消化不良dyspepsia; indigestion; maldigestion 生理性腹泻physical diarrhea胃肠功能紊乱gastrointestinal dysfunction肠胃炎enterogastritis胃肠炎gastroenteritis;gastroenterocolitis细菌性肠炎bacterial enteritis致病性大肠杆菌肠炎enteropathogenic E.coli enteritis 真菌性肠炎Mycetes enteritis; fungous enteritis 病毒性肠炎Viral enteritis轮状病毒肠炎rotavirus enteritis坏死性肠炎necrotic enteritis水电解质紊乱Water-Electrolyte disturbances脱水Dehydration;anhydration代谢性酸中毒metabolic acidosis低钾血症kaliopenia低钙血症hypocalcemia高钠血症hypernatremia急性胃炎acute gastritis先天性肥大性幽门狭窄congenital hypertrophic pyloricstenosis肠梗阻intestinal obstruction;IO; ileus机械性肠梗阻mechanical ileus麻痹性肠梗阻paralytic ileus肠套叠intussusception急性肠系膜淋巴结炎Acute mesenteric lymphadenitis 肝肿大hepatomegalia; hepatomegaly药物性肝损害(炎)drug-induced liver injury;Drug-induced hepatitis巨细胞病毒肝炎Cylomegalovirus肝脓疡liver abscess急性胰腺炎acute pancreatitis;AP房间隔缺损ASD; atrial septal defect;卵圆孔未闭acleistocardia; open foramen ovale 室间隔缺损ventricular septal defect;VSD动脉导管未闭patent ductus arteriosus;PDA;法乐四联症tetralogy of Fallot; (F4; TOF)先天性二尖瓣关闭不全congenital mitral insufficiency 二尖瓣脱垂综合征mitral valve prolapse syndrome,MVPS;心律失常arrhythmia; arhythmia;CA窦性心动过速sinus tachycardia;ST窦性心动过缓sinus bradycardia,SB窦性心律不齐sinus arrhythmia;SA2游走心律wandering rhythm房性早搏atrial premature beats交界性早搏junctional premature beat室性早搏ventricular premature contraction阵发性室上性心动过速paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia;PST;PSVT;PSUT心房颤动atrial fibrillation完全性房室传导阻滞Complete atrioventricular block 病态窦房结综合征sick sinus syndrome;SSS预激综合征pre-excitation syndrome;W-P-W syndrome不完全性左束支传导阻滞incomplete left bundle branch block,ILBBB充血性心力衰竭congestive cardiac failure; congestive heart failure心源性休克cardiac shock;cardiogenic shock 感染性心内膜炎Infective endocarditis心肌病cardiomyopathy; myocardiopathy 心肌炎myocarditis,MC感染性心肌炎infective myocarditis病毒性心肌炎viral myocarditis;VM支原体性心肌炎mycoplasma myocarditis扩张型心肌病dilated cardiomyopathy肥厚性心肌病hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HC 限制性心肌病restrictive cardiomyopathy急性心包炎acute pericarditis化脓性心包炎purulent pericarditis;pyopericarditis; suppurative pericarditis病毒性心包炎Viral pericarditis肾性高血压renal hypertension;RH先天性尿路畸形congenital urinary tract deformity 婴儿型多囊肾infantile polycystic kidney包皮过长redundant prepuce鞘膜积液hydrocele of tunica vaginalis睾丸下降不全incomplete orchiocatabasis; cryptochidism肾小球肾炎glomerulonephritis; GN 急性肾小球肾炎acute glomerulonephritis急性链球菌感染后肾小球肾炎acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis;APSGN肾病综合征nephrotic syndrome;NS 单纯性肾病综合症simple type NS肾炎性肾病综合征nephritis NS孤立性血尿isolated hematuria孤立性蛋白尿isolated proteinuria复发性血尿recurrent hematuria持续性血尿persistent hematuria溶血尿毒综合征hemolytic uremic syndrome泌尿道感染urinary tract infection;UTI急性肾盂肾炎acute pyelonephritis急性肾功能衰竭acute renal failure;ARF肾小管性酸中毒renal tubular acidosis;RTA小儿贫血infantile anemia小细胞低色素性贫血microcytic hypochromic anemia 营养性贫血nutritional anemia缺铁性贫血iron deficiency anemia;IDA;sideropenic anemia巨幼红细胞性贫血megaloblastic anemia,MA营养性混合性贫血nutritional anemia;mixed type再生不良性贫血hypoplastic anemia再生障碍性贫血aplastic anemia感染性贫血Anemia of chronic infection铁粒幼红细胞性贫血sideroblastic anemia,SA 骨髓增生异常综合征myelodysplastic syndrome,MDS 溶血性贫血hemolytic anemia,HA蚕豆病fabism;favism感染性溶血性贫血hemolytic anemia,infectious失血性贫血Blood loss anemia中性粒细胞增多症neutrophilia中性粒细胞减少症Neutropenia免疫性粒细胞减少症immunologic neutropenia 感染性粒细胞减少症infective Granulocytopenia 血小板减少性紫癜thrombocytopenic purpura;thrombopenic purpura;TP 特发性血小板减少性紫癜idiopathic thrombocytopenicpurpura继发性血小板减少性紫癜thrombocytopenic purpura,secondary感染性血小板减少性紫癜infectious thrombocytopenicpurpura药物性免疫性血小板减少性紫癜drugs induced immunethrombocytopenic purpura 血栓性血小板减少性紫癜thrombotic thrombocytopenicpurpura3血友病 A hemophilia A血友病 B hemophilia B (plasma thromboplastin component, PTC)血友病 C hemophilia C (plasma thromboplastin antecedent, PTA)低凝血酶原血症Hypoprothrombinemia先天性凝血酶原缺乏症congenital prothrombin deficiency 维生素K缺乏症vitamin K deficiency脾脏增大(脾肿大)hypersplenotrophy;splenectasis;sple nomegalia;splenomegaly脾功能亢进hypersplenism;hypersplenia急性淋巴结炎acute lymphadenitis急性颌下淋巴结炎acute submaxillary lymphadenitis 急性肠系膜淋巴结炎acute adenomesenteritis惊厥convulsion;eclampsia;hyperspasmia 癫痫epilepsy癫痫发作seizure婴儿痉挛症infantile spasm;IS(West syndrome) 癫痫持续状态epileptic state;SE惊厥持续状态convulsive status急性中毒性脑病acute toxic encephalopathy;ATE蛛网膜下腔出血SAH;subarachnoid hemorrhage脑室内出血intraventricular hemorrhage先天愚型Down's disease;Down's syndrome;Mongolism脑积水hydrencephaly;hydrocephalus 小儿急性偏瘫acute hemiplegia in childhood 脑白质营养不良LD;leukodystrophy肾上腺脑白质营养不良adrenoleukodystrophy; Addison-Schilder disease呼吸暂停症(屏气发作)breathing holding (breath holding spell)癔病hysteria; hysterism尿崩症diabetes insipidus单纯性乳房早发育simple premature thelarche散发性甲状腺功能减低症sporadic hypothyroidism; sporadic cretinism地方性甲状腺功能减低症endemic hypothyroidism; endemic cretinism亚急性甲状腺炎subacute thyroiditis,SAT慢性淋巴细胞性甲状腺炎chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis;CLT 糖尿病diabetes酮症酸中毒ketoacidosis急性淋巴细胞性白血病acute lymphocytic leukemia;ALL 急性非淋巴细胞性白血病acute nonlymphocytic leukemia;ANL;ANLL慢性粒细胞白血病chronic myelocytic leukemia; CML;chronic granulocytic leukemia; CGL 淋巴瘤lymphoma; lymphadenoma;霍奇金病Hodgkin disease;Hodgkin's disease 脓疱疮crusted tetter脊柱侧弯scoliolosis脊柱裂cleft spine; spina bifida先天性手足畸形congenital extremities abnormality先天性髋关节半脱位Congenital subluxation of hip,CDH 流行性肌痛epidemic myalgia渗出性中耳炎exudative otitis; OME; otitis mediawith effusion急性化脓性中耳炎acute purulent otitis media; APOM 小儿眩晕vertigo; circumgyration; dinus化脓性结膜炎purulent conjunctivitis滤泡性结膜炎follicular conjunctivitis咽结膜热pharyngoconjunctival fever,PCF疱疹性口炎herpetic stomatitis鹅口疮thrush; muguet; mycotic stomatitis口角炎angular cheilitis;angular chilitis感染性口角炎perleche地图舌geographic tongue食物中毒food poisoning; food poison细菌性食物中毒bacterial food poisoning农药中毒pesticide intoxication有机磷农药中毒organophosphorus pesticide感染性休克septic shock急性呼吸衰竭acute respiratory failure;ARF颅内高压征acute intracranial hypertension消化道大出血massive hemorrhage ofgastrointestinal tract4。

西医感染科术语英文翻译以下是常见的西医感染科术语英文翻译:1. 病毒感染:Viral Infection2. 细菌感染:Bacterial Infection3. 真菌感染:Fungal Infection4. 寄生虫感染:Parasitic Infection5. 支原体感染:Mycoplasma Infection6. 立克次体感染:Rickettsial Infection7. 衣原体感染:Chlamydial Infection8. 性传播感染:Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs)9. 医院获得性感染:Hospital-Acquired Infections (HAIs)10. 社区获得性感染:Community-Acquired Infections (CAIs)11. 抗药性感染:Antibiotic-Resistant Infections12. 病毒性肝炎:Viral Hepatitis13. 细菌性痢疾:Bacterial Dysentery14. 结核病:Tuberculosis (TB)15. 破伤风:Tetanus16. 梅毒:Syphilis17. 性病性淋巴肉芽肿:Lymphogranuloma Venereum (LGV)18. 人乳头瘤病毒感染:Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection19. 钩端螺旋体病:Leptospirosis20. 疟疾:Malaria21. 阿米巴病:Amoebiasis22. 弓形虫病:Toxoplasmosis23. 细菌性食物中毒:Bacterial Food Poisoning24. 病毒性心肌炎:Viral Myocarditis25. 流行性感冒:Influenza (Flu)26. 登革热:Dengue Fever27. 黄热病:Yellow Fever28. 脑膜炎:Meningitis29. 败血症:Septicemia30. 脓毒症:Sepsis31. 脓肿:Abscess32. 发热待查:Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO)33. 抗生素治疗:Antibiotic Therapy34. 对症治疗:Symptomatic Treatment35. 免疫疗法:Immunotherapy36. 支持性护理:Supportive Care37. 隔离措施:Isolation Measures38. 预防接种:Vaccination39. 手卫生:Hand Hygiene40. 环境清洁消毒:Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection41. 传染病监测与控制:Infectious Disease Surveillance and Control42. 人免疫缺陷病毒(HIV)感染:Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection43. 人乳头瘤病毒疫苗(HPV疫苗):Human Papillomavirus Vaccine (HPV vaccine)44. 克林霉素抗药性检测:Clindamycin Resistance Testing45. 卡介苗接种(BCG接种):Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) Vaccination46. 内毒素检测(Endotoxin Detection):Endotoxin Testing (LPS Testing)47. 白喉抗毒素治疗(Diphtheria Antitoxin):Diphtheria Antitoxin Therapy (DAT)48. 结核病预防性治疗(TB Preventive Therapy):TB Preventive Therapy (TPT)49. 人畜共患病(Zoonoses):Zoonoses (Animal-borne Diseases)50. 人畜共患病预防和控制(Zoonosis Prevention and Control):Zoonosis Prevention and Control西医儿科术语英文翻译以下是常见的西医儿科术语英文翻译:1. 儿科:Pediatrics2. 儿童生长发育:Child Growth and Development3. 新生儿:Neonate4. 婴儿:Infant5. 学龄前儿童:Preschool Child6. 学龄儿童:School-aged Child7. 青春期:Adolescence8. 儿童营养:Child Nutrition9. 母乳喂养:Breastfeeding10. 配方奶喂养:Formula Feeding11. 断奶:Weaning12. 幼儿急疹:玫瑰疹:Rubella13. 水痘:Varicella14. 手足口病:Hand-foot-mouth Disease (HFMD)15. 流行性感冒:Influenza16. 中耳炎:Otitis Media17. 急性上呼吸道感染:Acute Upper Respiratory Infection (URI)18. 支气管肺炎:Bronchopneumonia19. 支原体肺炎:Mycoplasma Pneumonia20. 百日咳:Pertussis21. 儿童哮喘:Asthma in Children22. 过敏性鼻炎:Allergic Rhinitis23. 肠道寄生虫病:Intestinal Parasitic Diseases24. 微量元素缺乏症:Trace Element Deficiency25. 维生素缺乏症:Vitamin Deficiency26. 新生儿黄疸:Neonatal Jaundice27. 新生儿窒息:Neonatal Asphyxia28. 新生儿败血症:Neonatal Sepsis29. 肠套叠:Intussusception30. 小儿肺炎:Pneumonia in Children31. 小儿腹泻病:Diarrhea in Children32. 小儿营养不良:Malnutrition in Children33. 小儿肥胖症:Childhood Obesity34. 小儿糖尿病:Diabetes Mellitus in Children35. 小儿先天性心脏病:Congenital Heart Disease in Children36. 风湿热:Rheumatic Fever37. 川崎病:Kawasaki Disease38. 幼年特发性关节炎:Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)39. 儿科重症监护病房(PICU):Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU)40. 新生儿重症监护病房(NICU):Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)41. 儿童生长发育评估:Child Growth Assessment42. 儿童免疫接种计划:Child Immunization Schedule43. 儿童心理咨询与治疗:Child Psychological Counseling and Therapy44. 儿童康复治疗:Child Rehabilitation Therapies45. 儿童行为问题咨询与治疗:Child Behavioral Issues Counseling and Therapy46. 儿童疫苗接种咨询与指导:Child Vaccination Counseling and Guidance47. 新生儿筛查项目:Neonatal Screening Programs48. 小儿危重症管理技术:Critical Care Management in Children49. 儿科药理学和药物治疗学:Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics50. 小儿外科手术技术:Pediatric Surgical Techniques。

增加孩子的负担英文作文1. Nowadays, children are facing an increasing burdenin their lives. They have to deal with heavy academic workloads, participate in numerous extracurricular activities, and face the pressure of high expectations from their parents and society.2. The academic pressure on children is immense. They have to study for long hours, complete numerous assignments and projects, and prepare for multiple exams. This constant pressure to perform well in academics can lead to stress, anxiety, and even burnout.3. In addition to academic pressure, children are also expected to excel in extracurricular activities. They have to participate in sports, music, dance, and otheractivities to enhance their skills and build a well-rounded personality. While these activities are important for their overall development, the sheer number of activities can leave children with little time for relaxation and leisure.4. Moreover, parents often have high expectations from their children. They want them to achieve top grades, win competitions, and secure a bright future. This constant pressure to meet their parents' expectations can be overwhelming for children and can negatively impact their mental and emotional well-being.5. Furthermore, the influence of social media and peer pressure adds to the burden on children. They are constantly bombarded with images of their peers achieving great things, which can make them feel inadequate and push them to do more and be better.6. The increasing burden on children can have long-term consequences. It can lead to a lack of motivation, decreased self-esteem, and even mental health issues. Children need time to relax, play, and explore their interests without the constant pressure to perform.7. It is important for parents and educators to recognize the negative impact of an increasing burden onchildren and take steps to alleviate it. They should encourage a healthy balance between academics, extracurricular activities, and leisure time. They should also provide emotional support and create a nurturing environment where children feel valued for who they are, rather than just their achievements.8. In conclusion, the increasing burden on children isa concerning issue. It is essential for parents, educators, and society as a whole to address this issue and prioritize the well-being and happiness of children over excessive expectations and pressure. Children deserve a childhood filled with joy, exploration, and personal growth, rather than a constant race to meet unrealistic expectations.。

康复听力学试卷1 1、女,6个月,出生体重3.0kg,现体重应为()A.6.50kgB.7.20kgC.8.15kgD.8.50kgE.9.95kg2、男,3岁,他的标准身高是()A. 84cmB. 86cmC. 91cmD. 96cmE. 101cm3、婴儿期指()A. 从28天至不满1岁B. 从出生至不满28天C. 从出生至不满1岁D. 从28天至不满3岁E. 从出生至不满7天4、不属于婴儿期小儿特点的是()A. 体格生长迅速B. 脑发育快C. 易患消化紊乱及营养不良等疾病D. 易患急性传染病E. 易发生意外事故5、不属于幼儿期小儿特点的是()A. 前囟闭合B. 乳牙出齐C. 脑发育很快D. 能用人称代词,会说简单句子E. 易发生意外事故6、健康婴儿每日每公斤体重需水量为()A. 150mlB. 120 mlC. 100 mlD. 90 mlE. 80 ml7、不属于维生素D生理功能的是()A. 促进肠道对钙的吸收B. 促进成骨细胞增殖与合成碱性磷酸酶,促进骨钙素的合成C. 促使间叶细胞向成熟破骨细胞分化,从而发挥骨质重吸收效应D. 抑制肾小管对钙、磷重吸收E. 1, 25-(OH)2D参与多种细胞的增殖、分化和免疫功能的调控过程8、冬春季多见维生素D缺乏性佝偻病的原因是()A. 日照时间短,紫外线较弱B. 食物中维生素D含量不足C. 婴儿食物中钙、磷含量少D. 婴儿生长快、钙磷需要量多E. 体内维生素D储备量少9、不符合维生素D缺乏性佝偻病临床表现的是()A. 多汗B. 方颅C. 枕秃D. 惊厥E. 肌肉松弛10、佝偻病后遗症期指()A. 1岁以后B. 2岁以后C. 3岁以后D. 4岁以后E. 5岁以后11、预防婴幼儿维生素D缺乏性佝偻病,不正确的是()A. 孕妇及乳母多作户外活动B. 每日补充维生素D400IUC. 多晒太阳D. 饮食应富含维生素、钙、磷和蛋白质等E. 小于3个月小儿不可抱出户外活动12、维生素D缺乏性手足搐搦症最常见的症状是()A. 惊厥B. 喉痉挛C. 腓反射D. 手足搐搦E. 陶瑟征13、小儿急性喉炎,哪项是错误的()A. 犬吠样咳嗽B. 声音嘶哑C. 呼气性呼吸困难D. 喉喘鸣E. 三凹征14、第二度喉梗阻表现为()A. 安静时出现喘鸣和呼吸困难B. 肺呼吸音清晰C. 心率无改变D. 口唇和指(趾)发绀E. 活动时出现喘鸣和呼吸困难15、铁剂治疗缺铁性贫血应服用至:A. Hb正常后B. 网织红细胞计数达高峰即可C. 网织红细胞和Hb达正常水平D. Hb达正常水平后2个月左右E. 总疗程达1个月时16、3岁男孩,高热2周。

不同流量给氧在先天性心脏病患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒中的应用效果周诗敏摘要 目的:探索不同流量给氧在先天性心脏病(先心病)患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒中的应用效果㊂方法:采用便利抽样法选取2022年3月 10月长沙市某三级甲等儿童医院心脏外科接受心脏手术的63例先心病患儿作为研究对象,随机分为低流量组㊁中流量组㊁高流量组3组,每组21例㊂低流量组氧流量设为1~2L /m i n ,中流量组设为>2~6L /m i n ,高流量组设为>6~10L /m i n ㊂探究在先心病患儿全身麻醉术后不同流量给氧对患儿唤醒时间㊁苏醒室停留时间㊁咽喉痛㊁躁动和平均动脉压波动发生率的影响㊂结果:高流量组患儿唤醒时间㊁苏醒室停留时间显著短于低流量组和中流量组,差异均具有统计学意义(P <0.05)㊂高流量组患儿平均动脉压波动情况显著少于低流量组和中流量组,躁动发生率显著低于低流量组和中流量组,差异均具有统计学意义(P <0.05)㊂结论:高流量给氧可以缩短先心病患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒时间,提高唤醒质量㊂关键词 高流量给氧;先心病;儿童;全身麻醉;唤醒K e yw o r d s h i g h f l o wo x y g e n s u p p l y ;c o n g e n i t a l h e a r t d i s e a s e ;c h i l d ;g e n e r a l a n e s t h e s i a ;a w a k e n d o i :10.12104/j.i s s n .1674-4748.2023.32.024 在我国每千例新生儿中约有9例患有先天性心脏病(下称先心病),其中大部分患儿都需要进行先心病全身麻醉手术[1-2]㊂在先心病患儿全身麻醉术后,唤醒是影响手术效果㊁患儿康复质量的重要因素[3-4]㊂该手术唤醒存在的重要隐患在气道管理,而氧疗流量的选择则是气道管理的重点㊂目前我国临床上氧疗流量常规设定范围较为模糊,缺乏规范性㊂世界卫生组织发布的危重症儿童氧疗指南[5]中也提到,虽然根据病理生理学的研究和既往临床经验已经建立了儿童氧疗流量设置的大致区间(1~10L /m i n )[6-8],但是仍然缺乏更为精确的儿童氧疗流量设置的高质量证据㊂目前研究中尚未明确先心病患儿全身麻醉术后的给氧流量,而氧疗时氧流量的设置可能会影响先心病患儿的唤醒效果㊂因此,本研究采用类试验的方法,探索先心病患儿全身麻醉术后不同氧流量的设置对唤醒效果的影响,以期为医护人员制订先心病患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒的氧疗护理方案提供依据㊂1 对象与方法1.1 研究对象采用便利抽样法,选取2022年3月 10月长沙市某三级甲等儿童医院心脏外科接受心脏手术的63例先心病患儿作为研究对象㊂纳入标准[9-10]:1)年龄ɤ5岁;2)单纯的左向右分流先心病;3)血氧饱和度<85%;4)与患儿家属签署知情同意书㊂排除标准[9-10]:1)具有神经系统疾病或者其他可能影响本试验的疾病;2)发生过颅脑外伤;3)合并肺动脉高压㊂脱落标准:氧疗过程中患儿出现呼吸异常㊁氧合下降㊁血流动力学不稳定等情况;设置的氧流量无法满足患儿机体需要㊂按入科顺序编号,采用随机数字表法随机产生63作者简介 周诗敏,护师,本科,单位:410007,湖南省儿童医院㊂引用信息 周诗敏.不同流量给氧在先天性心脏病患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒中的应用效果[J ].全科护理,2023,21(32):4563-4565.个数字,装入信封实施分配隐藏,研究人员随机抽选信封㊂根据抽选的数字将病人随机分为3组(低流量组㊁中流量组㊁高流量组)㊂本研究通过湖南省儿童医院伦理委员会批准,伦理编号:K Y S Q 2022-079㊂所有儿童家属均知情同意㊂1.2 研究方法1.2.1 吸氧方法3组先心病患儿全身麻醉术后氧流量设置分为低㊁中㊁高流量3种㊂低流量以1~2L /m i n,吸入氧浓度(F i O 2)=(21+流量ˑ4)%为代表,中流量以3~6L /m i n ,F i O 2=(21+流量ˑ4)%为代表,高流量以6~10L /m i n ,F i O 2(21+流量ˑ4)%为代表[11-16]㊂临床实践中,氧流量设置多根据病人病情动态调节㊂考虑临床实际工作中的可操作性,本研究将氧流量设置为具体参数范围,即低流量组流量为1~2L /m i n ,F i O 2=(21+流量ˑ4)%;中流量组流量为>2~6L /m i n,F i O 2=(21+流量ˑ4)%;高流量组流量为>6~10L /m i n ,F i O 2=(21+流量ˑ4)%㊂1.2.2 评价方法1.2.2.1 病人一般资料包括性别㊁年龄㊁疾病类型㊁手术时间和体外循环时间㊂1.2.2.2 唤醒相关时间指标包括唤醒时间㊁苏醒室停留时间㊂唤醒时间是指停止用药(麻醉药)至唤醒成功的时间㊂苏醒室停留时间是指从入苏醒室至出苏醒室的时间㊂本次研究的时间节点均由研究组成员在患儿出苏醒室后由麻醉系统导出㊂1.2.2.3 唤醒质量相关指标包括咽喉痛㊁躁动和平均动脉压波动发生率㊂咽喉痛采用东大略儿童医院疼痛评分法(C H E O P S )评分,既往已有较多研究表明该评分法在0~5岁患儿中应用信效度较高[17]㊂根据患儿哭闹㊁面部表情㊁语言㊃3654㊃全科护理2023年11月第21卷第32期情况,将咽喉痛分为4级,0级表示无咽喉痛,1~2级表示轻度咽喉痛,3级为重度咽喉痛㊂躁动分为4级:0级表示病人安静㊁合作㊁无挣扎;1级表示刺激时病人肢体有活动,用语言可以唤醒;2级表示病人无刺激时就有间断的挣扎,但不需制动;3级表示病人强烈挣扎并需多人进行制动[18-20]㊂其中,0级表示无躁动,1~2级表示轻度躁动,3级为重度躁动㊂平均动脉压波动在基础值的20%及以上,则认为有波动,反之则无㊂小组成员在病人唤醒后即刻评估患儿的躁动评分,并在拔管后评估患儿咽喉痛情况,同时根据监护仪数值记录患儿平均动脉压的波动情况㊂1.2.3 统计学方法 运用S P S S25.0软件录入数据并进行数据分析㊂问卷中的缺失值采用平均值代替㊂描述性分析中,符合正态分布的定量资料采用均数ʃ标准差(x ʃs )表示,定性资料用例数㊁百分比(%)表示㊂3组患儿年龄㊁手术时间㊁体外循环时间㊁唤醒时间和苏醒室停留时间比较采用方差分析,3组患儿性别㊁疾病类型㊁咽喉痛㊁躁动和平均动脉压波动情况比较采用χ2检验,以P <0.05为差异有统计学意义㊂2 结果2.1 3组患儿一般资料比较本研究共纳入63例先心病患儿,每组21例㊂3组患儿年龄㊁性别㊁疾病类型㊁手术时间和体外循环时间比较差异均无统计学意义(P >0.05),具有可比性㊂见表1㊂表1 3组先心病患儿一般资料比较组别例数年龄(个月)性别(例)男女 疾病类型(例)室间隔缺损房间隔缺损室间隔缺损+房间隔缺损手术时间(h)体外循环时间(m i n)低流量组2120.05ʃ14.6213812634.14ʃ0.4869.30ʃ7.58中流量组2117.62ʃ13.1216511734.04ʃ0.3068.20ʃ5.72高流量组2117.43ʃ12.3315614524.09ʃ0.3063.67ʃ11.81统计值F =0.250χ2=1.055χ2=0.962F =0.390F =2.524P0.7800.5900.9160.6790.0892.2 3组病人唤醒时间和唤醒质量比较高流量组患儿唤醒时间和苏醒室停留时间均显著短于低流量组和中流量组,差异具有统计学意义(P <0.05),见表2㊂高流量组患儿躁动发生率和无平均动脉压波动患儿占比显著高于低流量组和中流量组,差异具有统计学意义(P <0.05)㊂3组患儿咽喉痛发生率比较差异无统计学意义(P >0.05),见表3㊂表2 3组患儿唤醒时间及苏醒室停留时间比较单位:m i n组别例数唤醒时间苏醒室停留时间低流量组2112.33ʃ3.81①95.43ʃ14.11①中流量组2111.38ʃ4.09①88.48ʃ12.36①高流量组219.05ʃ4.10 84.38ʃ13.40F 值3.7413.699P0.0290.031①与高流量组比较,P <0.05㊂表3 3组患儿唤醒质量比较单位:例组别例数 咽喉痛 无轻度重度 躁动无轻度重度平均动脉压波动情况有无低流量组2161147①10①4①14①7①中流量组21712213①5①3①10①11①高流量组2181121821615χ2值1.34512.3046.109P0.8540.0150.047①与高流量组比较,P <0.05㊂3 讨论3.1 高流量给氧能够缩短先心病患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒时间本研究结果显示,高流量组先心病患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒时间及苏醒室停留时间明显短于低流量组㊁中流量组(均P <0.05)㊂这在一定程度上说明,高流量给氧能够缩短先心病患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒时间,有利于提高麻醉复苏室的运转效率㊂可能原因是高流量给氧能够改善机体脑细胞的供血㊁供氧[21],从而更快地解除全身麻醉结束后先心病患儿大脑的抑制状态㊂师博文[22]的研究中发现,在先心病患儿全身麻醉手术中,相较于低氧组,高氧分压给氧进行体外循环可降低患儿胶原纤维酸性蛋白㊁丙二醛水平,提升脑神经元兴奋性,更加有利于脑部损伤组织的恢复㊂这提示护理人员在为患儿调节氧流量时,在符合患儿机体所需的氧流量范围下应该选择较高的流量参数㊂㊃4654㊃C H I N E S EG E N E R A LP R A C T I C E N U R S I N G N o v e m b e r 2023V o l .21N o .323.2高流量给氧能够改善先心病患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒质量本研究结果显示,与低流量给氧相比,采用高流量给氧可以减少患儿躁动和平均动脉压波动的情况发生(均P<0.05)㊂W a n g等[23]的系统评价中也显示了类似的结果,在成人心脏手术中,采用高流量给氧可以减少病人术后躁动等情况㊂患儿发生躁动可能会导致气管导管或引流管移位㊁伤口敷料脱落等不良后果,进而造成缺氧㊁出血㊁手术伤口裂开,甚至导致手术失败[24]㊂患儿在唤醒的过程中可能会由于处在一个陌生的环境和状态下而造成平均动脉压波动,而采用高流量给氧可以减少患儿平均动脉压波动的情况发生,进而减少脑血管意外和心律失常等严重后果的发生[25-26]㊂但是本研究没有发现不同氧流量给氧会对先心病患儿全身麻醉术后咽喉痛有影响,与吴海燕等[27]在上肢骨骨折手术合并上呼吸道感染患儿中进行的研究结果不一致㊂这可能与病种不一致有关,也有可能与本研究中的先心病患儿年龄较小,不会表达自己的疼痛有关,在未来需要开展进一步的研究㊂3.3局限性与不足本研究存在一定局限性与不足㊂首先,研究的总样本量较小,未来可以进行多中心㊁更大样本的研究,进一步探讨高流量给氧在先心病患儿全身麻醉手术后唤醒中的应用㊂其次,考虑到患儿年龄和语言表达能力,本研究中评估唤醒效果的客观指标较多,纳入的主观指标较少,未来可以考虑更多变量,全方面分析高流量给氧在先心病患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒中的应用效果㊂4小结总的来说,高流量给氧能够缩短先心病患儿全身麻醉术后唤醒时间,并且提高患儿的唤醒质量㊂同时,临床医护人员在先心病患儿全身麻醉术后氧流量的设定中也需要结合病人病情进行个性化和动态化管理㊂参考文献:[1] Z H O U WJ,H O U J M,S U N M,e ta l.T h ei m p a c to ff a m i l ys o c i o e c o n o m i cs t a t u so n e l d e r l y h e a l t hi n C h i n a:b a s e d o nt h ef r a i l t y i n d e x[J].I n t e r n a t i o n a l J o u r n a l o fE n v i r o n m e n t a lR e s e a r c ha n dP ub l i cH e a l t h,2022,19(2):968.[2] X I A N GL,S U Z H,L I U Y W,e ta l.E f f e c to f f a m i l y s o c i o e c o n o m i cs t a t u so nt h e p r o g n o s i so fc o m p l e xc o n g e n i t a lh e a r td i s e a s ei nc h i ld re n:a no b s e r v a t i o n a l c o h o r t s t u d yf r o m C h i n a[J].T h eL a n c e tC h i l d&A d o l e s c e n tH e a l t h,2018,2(6):430-439.[3] S U N D A R Y M,P A R T H A S A R A T H Y S,R A D H I K A K.A w a k ec a ud a la ne s t h e s i af o r a n o p l a s t y i n a p r e t e r m n e w b o r n w i t hc o m p l e x c y a n o t i c c o n g e n i t a l h e a r td i se a s e[J].J o u r n a l o fA n a e s t h e s i o l o g y C l i n i c a l P h a r m a c o l o g y,2018,34(1):126.[4] D'A N T I C OC,H O F E R A,F A S S LJ,e t a l.C a s e r e p o r t:e m e r g e n c ya w a k e c r a n i o t o m y f o r c e r eb r a l a b sc e s s i n a p a t i e n tw i t h u n r e p a i r e dc y a n o t i cc o n g e n i t a lh e a r td i se a s e[J].F1000R e s e a r c h,2016,5:2521.[5] WH O.G u i d e l i n e:u p d a t e so n p a e d i a t r i ce m e r g e n c y t r i a g e,a s s e s s m e n ta n dt r e a t m e n t:c a r eo fc r i t i c a l l y-i l lc h i l d r e n[M].G e n e v a:W o r l dH e a l t hO r g a n i z a t i o n,2016:1.[6] M I LÉS IC,MA T E C K IS,J A B E R S,e ta l.6c mH2O c o n t i n u o u sp o s i t i v ea i r w a yp r e s s u r ev e r s u sc o n v e n t i o n a lo x y g e nt h e r a p y i n s e v e r e v i r a l b r o n c h i o l i t i s:a r a n d o m i z e d t r i a l[J].P e d i a t r i c P u l m o n o l o g y,2013,48(1):45-51.[7] E L K S M,Y O U N G J,K E A R N E Y L,e ta l.T h ei m p a c t o fa na u t o n o m o u s n u r s e-l e dh i g h-f l o wn a s a l c a n n u l ao x y g e n p r o t o c o l o nc l i n i c a lo u t c o m e s o fi n f a n t s w i t h b r o n c h i o l i t i s[J].J o u r n a l o fC l i n i c a lN u r s i n g,2023,32(15/16):4719-4729.[8] H O U G HJL,P HAM T M T,S C H I B L E R A.P h y s i o l o g i c e f f e c t o fh i g h-f l o wn a s a l c a n n u l a i n i n f a n t sw i t hb r o n c h i o l i t i s[J].P e d i a t r i cC r i t i c a l C a r eM e d i c i n e,2014,15(5):e214-e219.[9]陈寄梅,庄建,刘小清,等.先天性心脏病产前产后 一体化 诊疗模式中国专家共识[J].中国心血管病研究,2022,20(2):97-103.[10]国家卫生健康委员会国家结构性心脏病介入质量控制中心,国家心血管病中心结构性心脏病介入质量控制中心,中华医学会心血管病学分会先心病经皮介入治疗指南工作组,等.常见先天性心脏病经皮介入治疗指南(2021版)[J].中华医学杂志,2021, 101(38):3054-3076.[11]陈烁,陈麒,王艳玲,等.加温加湿经鼻高流量氧疗在心脏术后患者低氧血症中应用的M e t a分析[J].中华现代护理杂志,2021,27(31):4275-4281.[12]季景媛,唐会静,王宏梅.经鼻高流量氧疗用于心脏外科术后患者的研究进展[J].医疗装备,2019,32(18):201-202. [13]谢小伟,李武军,赵海,等.不同吸氧流量对高海拔高原地区病人术后血氧饱和度的影响[J].外科理论与实践,2019,24(2):155-158.[14]骆磊,王叶倩.胸部手术后患者氧驱动雾化吸入不同氧流量的效果观察[J].护理实践与研究,2015,12(9):120-121. [15]汪子钰.改良式口罩吸氧装置的临床运用[J].中华现代护理杂志,2013,19(6):700.[16]王美兰,方建梅,谢强丽,等.开胸术后患者氧驱动雾化吸入治疗中氧流量的研究[J].护士进修杂志,2011,26(14):1256-1257.[17]刘莹,刘天婧,王恩波.不同年龄段儿童疼痛评估工具的选择[J].中国疼痛医学杂志,2012,18(12):752-755.[18]牛红艳,马玉龙,郭梦晓.针对性护理干预对胃癌患者术后麻醉恢复期的影响[J].齐鲁护理杂志,2022,28(14):120-122. [19]刘明旻,王玉婷,鲍洁.医护一体化协作模式在全身麻醉术后病人复苏期管理中的应用[J].护理研究,2022,36(14):2606-2609.[20]彭景燕,李玉霞,杨运亮,等.不同剂量右美托咪定滴鼻对小儿地氟烷吸入麻醉术后躁动㊁恶心及呕吐的改善效果研究[J].川北医学院学报,2022,37(11):1447-1450.[21]李文奇,余遥,刘尚昆,等.多感官唤醒方案在全身麻醉胸科手术患者中的应用[J].护理学杂志,2022,37(20):54-56. [22]师博文.体外循环逐级给氧对紫绀型先心病围手术期G F A P水平影响的临床研究[D].上海:上海交通大学,2020.[23] WA N G YL,Z HUJK,WA N G X F,e ta l.C o m p a r i s o no fh i g h-f l o wn a s a l c a n n u l a(H F N C)a n dc o n v e n t i o n a l o x yg e nth e r a p yi no b e s e p a t i e n t su n d e r g o i n g c a r d i a cs u r g e r y:as y s t e m a t i cr e v i e wa n dm e t a-a n a l y s i s[J].I nV i v o,2021,35(5):2521-2529.[24] B A N C H SRJ,L E R MA N J.P r e o p e r a t i v ea n x i e t y m a n a g e m e n t,e m e r g e n c ed e l i r i u m,a n d p o s t o p e r a t i v e b e h a v i o r[J].A n e s t h e s i o l o g yC l i n i c s,2014,32(1):1-23.[25]黄金,刘训芹,李昂庆,等.个性化血压管理策略对老年胃肠手术后急性肾损伤的影响[J].中华全科医学,2022,20(7):1098-1101.[26]朱永锋.小儿先天性心脏病手术的麻醉处理[J].中国实用医药,2014,9(17):141-142.[27]吴海燕,姜良斌,李希明.不同氧流量预防患儿喉痉挛的临床观察[J].山东医学高等专科学校学报,2022,44(4):251-253.(收稿日期:2023-01-18;修回日期:2023-09-28)(本文编辑李进鹏)㊃5654㊃全科护理2023年11月第21卷第32期。

Journal of Clinical Virology 65(2015)41–45Contents lists available at ScienceDirectJournal of ClinicalVirologyj o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w.e l s e v i e r.c o m /l o c a t e /j cvViral load in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection identified on newborn hearing screeningJun-ichi Kawada a ,Yuka Torii a ,Yoshihiko Kawano a ,Michio Suzuki a ,Yasuko Kamiya a ,Tomomi Kotani b ,Fumitaka Kikkawa b ,Hiroshi Kimura c ,Yoshinori Ito a ,∗aDepartment of Pediatrics,Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine,Nagoya,JapanbDepartment of Obstetrics and Genecology,Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine,Nagoya,Japan cDepartment of Virology,Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine,Nagoya,Japana r t i c l e i n f o Article history:Received 4September 2014Received in revised form 19January 2015Accepted 21January 2015Keywords:Congenital cytomegalovirus infection Sensorineural hearing loss Valganciclovir Viral loada b s t r a c tBackground:Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV)infection is the most common non-genetic cause of sen-sorineural hearing loss (SNHL)in children.However,congenital SNHL without other clinical abnormalities is rarely diagnosed as CMV-related in early infancy.Objectives:The aim of this study was to identify and treat patients with congenital CMV-related SNHL or CMV-related clinical abnormalities other than SNHL.The association between CMV load and SNHL was also evaluated.Study design:Newborns who had abnormal hearing screening results or other clinical abnormalities were screened for congenital CMV infection by PCR of saliva or urine specimens,and identified infected patients were treated with valganciclovir (VGCV)for 6weeks.The CMV load of patients with or without SNHL was compared at regular intervals during as well as after VGCV treatment.Results:Of 127infants with abnormal hearing screening results,and 31infants with other clinical abnor-malities,CMV infection was identified in 6and 3infants,respectively.After VGCV treatment,1case had improved hearing but the other 5SNHL cases had little or no improvement.Among these 9patients with or without SNHL at 1year of age,there was no significant difference in CMV blood or urine load at diagnosis,but both were significantly higher in patients with SNHL during VGCV treatment.Conclusions:Selective CMV screening of newborns having an abnormal hearing screening result would be a reasonable strategy for identification of symptomatic congenital CMV infection.Prolonged detection of CMV in blood could be a risk factor for SNHL.©2015Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.1.BackgroundIn developed countries,congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV)infection occurs in 0.2–2.0%of births and is one of the most fre-quently identified members of the TORCH complex [1,2].Because most infants congenitally infected with CMV are considered to be asymptomatic at birth,the number of these patients is underesti-mated [2].Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL)is the most common sequela,and abnormal findings on ultrasonography and brain mag-Abbreviations:CMV,cytomegalovirus;SNHL,sensorineural hearing loss;VGCV,valganciclovir;MRI,magnetic resonance imaging;AABR,automated auditory brainstem response;OAE,oto-acoustic emission;US,ultrasound;SGA,small for gestational age;WM,white matter.∗Corresponding author at:Department of Pediatrics,Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine,65Tsurumai-cho,Showa-ku,Nagoya 466-8550,Japan.Tel.:+81527442294;fax:+81527442974.E-mail address:yoshi-i@med.nagoya-u.ac.jp (Y.Ito).netic resonance imaging are associated with SNHL [3].This disease is the most common non-genetic cause of SNHL in children [4].In Japan,12–15%of cases with severe SNHL were associated with congenital CMV infection [5].Because congenital CMV infection is a potentially treatable cause of SNHL,early identification is impor-tant.However,congenital SNHL without other clinical abnormalities is rarely recognized to be CMV-related in early infancy.Generally,it is recommended that neonates who do not pass hearing screening receive a comprehensive audiological evaluation no later than 3months of age [6].Infants with SNHL are suspected to have congen-ital CMV infection,but it is often too late to distinguish perinatal from congenital infection,or to offer antiviral treatment.Univer-sal newborn screening for congenital CMV infection could allow for early identification and intervention.There is fair evidence of a potential benefit from antiviral treatment during the neonatal period and early infancy for children with congenital CMV-related SNHL [7].On the other hand,potential harm arising from universal/10.1016/j.jcv.2015.01.0151386-6532/©2015Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.J.-i.Kawada et al./Journal of Clinical Virology65(2015)41–4543Fig.1.Longitudinal change of the mean CMV load in whole blood and urine specimens from patients with congenital CMV infection.Shaded region indicated the6-week duration of valganciclovir(VGCV)treatment.Filled and open circles represent patients with and without sensorineural hearing loss at1year of age,respectively.Bars indicate±SE of the mean.*P<0.05.newborn screening may include factors such as increased parental stress from a result(although more than80%of CMV-infected chil-dren never develop sequela),inappropriate antiviral treatment,or added costs from unnecessary medical visits or tests[8].Recently, Williams et al.have conducted a selective CMV screening program targeting infants who did not pass the hearing test[9].In that study, congenital CMV infection was identified in1.5%of infants,suggest-ing that this strategy is reasonable for identification of symptomatic patients with congenital CMV infection,who could benefit from antiviral treatment.In Japan,hearing screening is performed for about70%of all newborns,and approximately1∼2%are referred for further audiological evaluation[10].Here we report results of prospective screening for CMV of newborns who had abnormal hearing screening results.2.ObjectivesThe aims of this study were early identification and treatment of CMV-related SNHL by a selective CMV screening of infants having abnormal hearing screening test results.The effect of valganciclovir (VGCV)treatment and the association between CMV load and SNHL were also evaluated.3.Study design3.1.Patients and specimensInfants(<20days old)referred to Nagoya University Hospital for CMV testing because of abnormal neonatal hearing screening results were prospectively enrolled in this study from January2011 to December2013.Oto-acoustic emission or automated auditory brainstem response procedures were used for screening to detect hearing loss of over35∼40dB.Urine or salivary samples from infants with abnormal hearing screening test results,as well as from infants without SNHL but suspected to have congenital CMV infec-tion based on clinical symptoms or laboratory data,were collected and analyzed by real-time PCR to detect CMV DNA,as described previously[11–13].The minimum detection level with this assay is two copies/reaction[12],equal to100copies/mL.The amplifica-tion plots were checked to exclude non-specific amplified signals.44J.-i.Kawada et al./Journal of Clinical Virology65(2015)41–45Duplicate standard references through the dynamic range of the assay were examined in each assay.When CMV DNA was detected, patients were referred to Nagoya University Hospital for further evaluation.Ethics committee approval was obtained,and all par-ents gave written consent for their children to participate in this study.3.2.VGVC treatmentPatients with symptomatic congenital CMV infection were con-sidered for treatment with oral VGCV at32mg/kg/day(b.i.d)for 6weeks[14].Infants≤1month of age,≥32weeks’gestation,and body weight≥1800g at enrollment were eligible for VGCV treat-ment.Patients were not eligible for VGCV treatment if another antiviral agent or immunoglobulin was administered,if gastroin-testinal abnormalities existed to preclude drug absorption,or if creatinine was≥1.5mg/dl at enrollment.Close follow-up dur-ing VGCV treatment was performed,including weekly physical examinations,complete blood counts,and liver/kidney function tests.If a patient’s absolute neutrophil count(ANC)decreased to <500cells/mm3,VGCV was withheld until the ANC recovered to >750cells/mm3;administration of the drug was then resumed at the normal dosage.If the ANC again decreased to≤750cells/mm3, VGCV dosage was reduced by50%and was maintained at that level as long as the ANC remained>750cells/mm3.CMV DNA load in whole blood and urine were measured weekly during VGCV treat-ment,and then monthly or every other month until the patient was 12months of age.3.3.Audiological evaluationAudiological testing was carried out using the auditory brain-stem response and/or auditory steady state response at the time of diagnosis,and again at6and12months of age.Results were ana-lyzed by considering the best evaluable ear,and hearing loss degree was categorized as follows;normal hearing(<20dB),mild hearing loss(21–45dB),moderate hearing loss(46–70dB),severe hearing loss(71–90dB),and profound hearing loss(≥91dB).3.4.Statistical analysisThe Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze differences in CMV load between the two groups.A p value<0.05was considered statistically significant.4.ResultsDuring the study enrollment period,hearing screening was performed for20,760newborns in19facilities,and127(0.6%) infants were referred for further audiological evaluation.Of these 127infants,congenital CMV infection was identified in6(4.7%) by PCR using urine or saliva specimens.During the same period, among the31infants without SNHL but suspected to have congen-ital CMV infection because of other clinical abnormalities,such as being small for gestational age or having abnormal cerebral imag-ing,infection was identified in3(9.7%).A summary of these9 patients is shown in Table1.Other clinical manifestations of CMV infection,such as microcephaly,chorioretinitis,petechiae,hep-atosplenomegaly,and jaundice were not seen in any of the patients. All9patients were treated with oral VGCV for6weeks.All patients completed the treatment without any major adverse events,and neutropenia(ANC<500cells/mm3)(that would have required a dosage modification)was not observed in any patients.Of the6 patients identified by newborn hearing screening tests(cases1–6), only one patient(case6)had improved hearing after the VGCV treatment;however,little or no improvement was observed in the other5patients.Of the3patients without SNHL at diagnosis(cases 7–9),late-onset SNHL was not seen during the observation period (12–24months).Neurodevelopmental status was evaluated regu-larly,and an adaptive developmental quotient(DQ)was obtained from the ratio of the child’s developmental age to the chronological age multiplied by100.Developmental delay,which was defined as <70of the DQ,was seen in3patients at1year of age.All patients with developmental delay also had SNHL and abnormal cerebral imaging results(Table1).We examined the association of the prognosis of SNHL with CMV load at diagnosis or during VGCV treatment.The mean CMV load of the5patients with SNHL(cases1–5)at one year of age was compared with that of the4patients(cases6–9)without SNHL.As shown in Fig.1,before the administration of VGCV,the mean CMV load in whole blood of patients with and without SNHL were6.6×102copies/mL and4.2×102copies/mL,respectively, and mean CMV load in urine of patients with and without SNHL were8.8×105copies/mL and2.6×104copies/mL,respectively; neither of these differences was significant.In all4patients without SNHL at1year of age,CMV load in blood became undetectable1 week after the administration of VGVC;in the patients with SNHL, CMV decreased,but remained detectable continuously or intermit-tently over time.In3of4patients without SNHL,CMV urine load became undetectable6weeks after the administration of VGVC, while CMV was detected in4of5patients with SNHL at the same time point.During VGCV treatment,in patients with SNHL,CMV blood and urine load was significantly higher at several time points including both during and following VGCV treatment.After stop-ping VGCV treatment,in all5patients with SNHL and in2of4 patients without SNHL,a rebound of CMV blood load was observed. At5months after VGCV treatment,CMV was detected in blood from 3of5patients with SNHL,while it was undetectable in blood from patients without SNHL(Fig1).5.DiscussionIn this study,we identified6patients with symptomatic congen-ital CMV infection by selective CMV screening of infants who did not pass the neonatal hearing screening test.These patients might otherwise not have been diagnosed with congenital CMV infec-tion,because typical clinical manifestations such as microcephaly and hepatosplenomegaly were absent.In the recent universal CMV screening conducted in Japan,CMV was identified in0.3%of new-borns,and SNHL was observed in12%of infected cases[15].If these frequencies are applied to our study population,the predicted num-ber of congenital CMV-related SNHL is7.5,which is close to the number of cases identified in this study.These results suggest that selective CMV screening of newborns who do not pass the hear-ing screening test is a reasonable strategy for early identification of symptomatic congenital CMV infection[9,16].But a limitation of this selective CMV screening strategy is that patients with other neurologic involvement or late-onset SNHL are missed.Because more than80%of children with congenital CMV infection are esti-mated to be asymptomatic,a feasible and cost-effective method is needed to identify those patients who could benefit from antiviral treatment.Some severe cases of symptomatic congenital CMV infection have been treated with intravenous ganciclovir or oral VGCV for6 weeks[7,14,17–19].The randomized study conducted by Kimber-lin et al.has shown that,between testing at baseline and6months, 84%of ganciclovir recipients had improved hearing or maintained normal hearing,vs.59%of control patients;and none of the ganci-clovir recipients had worsened hearing,vs.41%of control patients [7].Recently,oral VCGV has sometimes been used for treatment of congenital CMV infection because oral VGCV can provide plasmaJ.-i.Kawada et al./Journal of Clinical Virology65(2015)41–4545concentrations of ganciclovir comparable to those achieved by administration of intravenous ganciclovir[14].Furthermore,VCGV can be used on an outpatient basis for mildly symptomatic patients, while treatment with intravenous ganciclovir requires at least6 weeks’hospitalization.In this study,all patients were treated with VGCV for6weeks,but hearing improvement was observed in1of6 patients with SNHL.Because4of6patients had severe or profound SNHL at baseline,VGCV treatment might have had only a small effect on hearing outcome.Recently,results of a phase III trial of6 weeks vs.6months of oral VGCV treatment were revealed;the trial showed that6months of treatment resulted in better audiologic and neurodevelopmental outcome than did6weeks of treatment [20].It might be possible that patients with severe SNHL require VGCV treatment for a longer period of time.In some previous studies,hearing loss appears to be associ-ated with increased concentrations of CMV in blood and urine [15,21–24].Infants with lower amounts of CMV in blood or urine are considered to be less likely to have SNHL,but a high amount of CMV is sometimes detected in the blood or urine of asymptomatic patients.In this study,there were no significant differences in CMV blood and urine load at diagnosis between patients with and with-out SNHL measured at1year of age.But interestingly,CMV in blood became undetectable1week after the administration of VGVC in all 4patients without SNHL at age1,while continuous or intermittent detection of CMV was observed in patients with SNHL at age1.Our results suggest that CMV load at diagnosis cannot predict the hear-ing outcome,but prolonged detection of CMV in blood during the VGCV treatment could be a risk factor for SNHL.Because prolonged CMV viremia might be associated with neurological sequelae of congenital CMV infection,6months of VGCV treatment might be most appropriate,especially for patients having a high CMV load [20].FundingNone.Competitng interestNot required.Ethical approvalThe study design and purpose were approved by the insti-tutional review board of Nagoya University(2010-885).Written informed consent was provided by study participants and/or their legal guardians prior to enrolment.AcknowledgementsWe thank the following pediatricians for providing specimens and patient care:M.Oshiro(Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daiichi Hospital,Nagoya),S.Hara(Toyota Memorial Hospital,Aichi),M. Kajita(Toyota Kosei Hospital,Aichi),Y.Kato(Anjo Kosei Hospi-tal,Aichi),Y.Yanase(Seven Bells Clinic,Aichi),and A.Ishida(Gifu Prefectual Tajimi Hospital,Gifu).References[1]A.Kenneson,M.J.Cannon,Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology ofcongenital cytomegalovirus(CMV)infection,Rev.Med.Virol.17(2007)253–276.[2]Y.Torii,H.Kimura,Y.Ito,M.Hayakawa,T.Tanaka,H.Tajiri,et al.,Clinicoepidemiologic status of mother-to-child infections:a nationwidesurvey in Japan,Pediatr.Infect.Dis.J.32(2013)699–701.[3]Y.Ito,H.Kimura,Y.Torii,M.Hayakawa,T.Tanaka,H.Tajiri,et al.,Risk factorsfor poor outcome in congenital cytomegalovirus infection and neonatalherpes on the basis of a nationwide survey in Japan,Pediatr.Int.55(2013)566–571.[4]C.C.Morton,Newborn hearing screening–a silent revolution,N.Engl.J.Med.354(2006)2151–2164.[5]S.Koyano,N.Inoue,T.Nagamori,H.Yan,H.Asanuma,K.Yagyu,et al.,Driedumbilical cords in the retrospective diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection as a cause of developmental delays,Clin.Infect.Dis.48(2009)e93–e95.[6]American Academy of Pediatrics JCoIH,Year2007position statement:principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and interventionprograms,Pediatrics120(2007)898–921.[7]D.W.Kimberlin,C.Y.Lin,P.J.Sanchez,G.J.Demmler,W.Dankner,M.Shelton,et al.,Effect of ganciclovir therapy on hearing in symptomatic congenitalcytomegalovirus disease involving the central nervous system:a randomized, controlled trial,J.Pediatr.143(2003)16–25.[8]M.J.Cannon,P.D.Griffiths,V.Aston,W.D.Rawlinson,Universal newbornscreening for congenital CMV infection:what is the evidence of potentialbenefit?Rev.Med.Virol.24(2014)291–307.[9]E.J.Williams,S.Kadambari,J.E.Berrington,S.Luck,C.Atkinson,S.Walter,et al.,Feasibility and acceptability of targeted screening for congenital CMV-related hearing loss,Arch.Dis.Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.99(2014)F230–236.[10]Y.Tanaka,M.Goto,H.Koga,Clinical surveillance of newborn hearingimpairment,J.Jpn.Pediatr.Soc.118(2014)899–903.[11]N.Tanaka,H.Kimura,K.Iida,Y.Saito,I.Tsuge,A.Yoshimi,et al.,Quantitativeanalysis of cytomegalovirus load using a real-time PCR assay,J.Med.Virol.60 (2000)455–462.[12]K.Wada,N.Kubota,Y.Ito,H.Yagasaki,K.Kato,T.Yoshikawa,et al.,Simultaneous quantification of Epstein-Barr virus,cytomegalovirus,andhuman herpesvirus6DNA in samples from transplant recipients by multiplex real-time PCR assay,J.Clin.Microbiol.45(2007)1426–1432.[13]S.B.Boppana,S.A.Ross,M.Shimamura,A.L.Palmer,A.Ahmed,M.G.Michaels,et al.,Saliva polymerase-chain-reaction assay for cytomegalovirus screening in newborns,N.Engl.J.Med.364(2011)2111–2118.[14]D.W.Kimberlin,E.P.Acosta,P.J.Sanchez,S.Sood,V.Agrawal,J.Homans,et al.,Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessment of oral valganciclovir in the treatment of symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease,J.Infect.Dis.197(2008)836–845.[15]S.Koyano,N.Inoue,A.Oka,H.Moriuchi,K.Asano,Y.Ito,et al.,Screening forcongenital cytomegalovirus infection using newborn urine samples collected onfilter paper:feasibility and outcomes from a multicentre study,BMJ Open 1(2011)e000118.[16]E.K.Stehel,A.G.Shoup,K.E.Owen,G.L.Jackson,D.M.Sendelbach,L.F.Boney,et al.,Newborn hearing screening and detection of congenitalcytomegalovirus infection,Pediatrics121(2008)970–975.[17]R.J.Whitley,G.Cloud,W.Gruber,G.A.Storch,G.J.Demmler,R.F.Jacobs,et al.,Ganciclovir treatment of symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: results of a phase II study National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group,J.Infect.Dis.175(1997)1080–1086. [18]G.Lombardi,F.Garofoli,P.Villani,M.Tizzoni,M.Angelini,M.Cusato,et al.,Oral valganciclovir treatment in newborns with symptomatic congenitalcytomegalovirus infection,Eur.J.Clin.Microbiol.Infect.Dis.28(2009)1465–1470.[19]N.Tanaka-Kitajima,N.Sugaya,T.Futatani,H.Kanegane,C.Suzuki,M.Oshiro,et al.,Ganciclovir therapy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection in sixinfants,Pediatr.Infect.Dis.J.24(2005)782–785.[20]D.W.Kimberlin,Six months versus six weeks of oral valganciclovir for infantswith symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus(CMV)disease with andwithout central nervous system(CNS)involvement:Results of a Phase III,randomized,double-blind,placebo-controlled,multinational study.IDWeek;2013,San Francisco,2013,LB-1.[21]R.D.Bradford,G.Cloud,keman,S.Boppana,D.W.Kimberlin,R.Jacobs,et al.,Detection of cytomegalovirus(CMV)DNA by polymerase chain reaction is associated with hearing loss in newborns with symptomatic congenitalCMV infection involving the central nervous system,J.Infect.Dis.191(2005) 227–233.[22]S.B.Boppana,K.B.Fowler,R.F.Pass,L.B.Rivera,R.D.Bradford,keman,et al.,Congenital cytomegalovirus infection:association between virusburden in infancy and hearing loss,J.Pediatr.146(2005)817–823.[23]S.A.Ross,Z.Novak,K.B.Fowler,N.Arora,W.J.Britt,S.B.Boppana,Cytomegalovirus blood viral load and hearing loss in young children withcongenital infection,Pediatr.Infect.Dis.J.28(2009)588–592.[24]J.Nijman,A.M.van Loon,L.S.de Vries,C.Koopman-Esseboom,F.Groenendaal,C.S.Uiterwaal,et al.,Urine viral load and correlation with disease severity ininfants with congenital or postnatal cytomegalovirus infection,J.Clin.Virol.54(2012)121–124.。