普遍主义

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:1.47 MB

- 文档页数:14

普遍主义名词解释

嘿,你知道啥是普遍主义不?普遍主义呀,就像是天空中那片广阔

无边的蓝天,涵盖着世间万物!它不是那种具体的、局限于某个小角

落的东西。

比如说,公平这个概念,大家都觉得应该公平对待每一个人,对吧?这就是一种普遍主义的体现呀!不管你是富人还是穷人,不管你是黑

人还是白人,都应该得到公平的机会和待遇,这难道不是应该的吗?

再看看爱这个伟大的情感,爱难道不应该是普遍的吗?对家人的爱,对朋友的爱,对陌生人的爱,甚至对整个世界的爱!这就像是阳光一样,温暖着每一个人,这就是普遍主义在发挥作用呀!

你想想看,要是没有普遍主义,这个世界会变成什么样?那岂不是

乱套了!每个人都只考虑自己,那还有什么和谐可言?

普遍主义还体现在道德准则上呢!诚实、善良、正直,这些美好的

品质,不应该是每个人都努力去拥有和践行的吗?这就是普遍主义在

引导我们走向更好的自己和更美好的世界呀!

普遍主义不是那种遥不可及的东西,它就在我们的生活中无处不在。

就好像我们呼吸的空气,虽然看不见摸不着,但却至关重要!它影响

着我们的思维方式、行为举止和价值观。

所以呀,普遍主义真的超级重要的!它让我们的世界更加有序、更加美好、更加充满希望!你难道不这么认为吗?

我的观点就是:普遍主义是构建和谐、美好世界的基石,我们应该珍视并努力践行它。

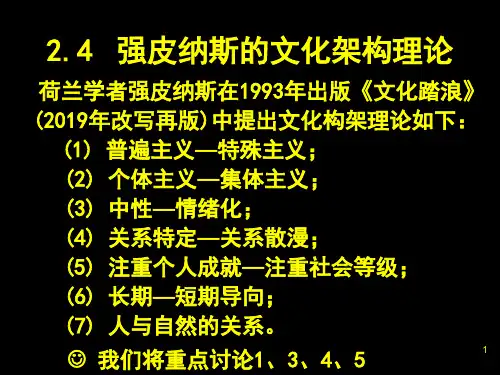

摘要营销是商业中直接与消费者打交道的一个功能性领域伦理问题广泛地存在于营销领域中营销人员潜在的非伦理行为最容易受到消费者密切的关注乃至争议随着越来越多的企业步出国门将业务全球化营销人员遇到的伦理问题由于文化冲突的影响而变得日趋复杂因此理解文化差异对伦理决策的影响对于避免潜在的商业陷阱和制定有效的国际营销管理项目显得愈加重要特龙彭纳斯和汉普登在他们的研究中指出美国属于高度普遍主义国家而中国属于高度特殊主义国家本论文尝试着通过比较中美两国营销专业的本科生探讨性地研究文化维度普遍主义与特殊主义对营销伦理决策的影响本论文分析了普遍主义与特殊主义这一文化维度对伦理决策三个阶段的影响这三个阶段是伦理知觉伦理判断伦理行为意图研究的结果表明文化维度普遍主义与特殊主义对营销伦理决策有很大的影响在伦理知觉方面美国人比中国人更有可能认识到营销中涉及到特惠待遇的伦理问题在伦理判断方面营销中道义论评价对美国人作出的伦理判断的影响比对中国人作出的伦理判断的影响更显著而目的论评价对中国人作出的伦理判断的影响比对美国人的影响更显著在伦理行为意图方面目的论评价对中国人形成的行为意图的影响比对美国人形成的行为意图的影响更显著虽然本论文的研究在某些方面尤其在受试方面存在着局限性但作为一个探讨性研究其结果仍然可以证明整个伦理决策的过程的确受到文化维度普遍主义与特殊主义的影响关键词普遍主义特殊主义伦理决策营销文化差异AbstractAs a functional area within business that interfaces with the consumer, marketing tends to come under the greatest scrutiny, generate the most controversy and receive the most criticism with respect to potentially unethical business practices.As more and more firms operate globally, the ethical problems faced by marketing practitioners have become more and more complicated as different culture clashes. Therefore, an understanding of the effects of cultural differences on ethical decision-making becomes increasingly important for avoiding potential business pitfalls and for designing effective international marketing management programs.According to Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner, the U.S.A. is ranked as a highly universalistic culture and China a highly particularistic culture. This dissertation attempts to make an exploratory study on the impact of the cultural dimension “universalism versus particularism” on ethical decision-making in marketing by comparing Chinese and American marketing undergraduate students.The dissertation analyzes the impact of the cultural dimension “universalism versus particularism” on the three stages of ethical decision-making including ethical perception, ethical judgment and ethical intention. The results show that the cultural dimension “universalism versus particularism” has a great influence on ethical decision-making in marketing. On ethical perception, Americans are more likely than their Chinese counterparts to recognize ethical problems involving preferential treatment of one over another in marketing context. On ethical judgment, deontological evaluation has a greater impact for Americans than for their Chinese counterparts in marketing context and teleological evaluation has a greater impact for Chinese than for their American counterparts in the marketing context. On ethical intention, teleological evaluation has a greater impact for Chinese than for their American counterparts in the marketing context.Though this dissertation has several limitations especially in the aspect of subject, as an exploratory study, the results, in a sense, still prove the whole ethical decision-making process is influenced by the cultural dimension “universalism versus particularism”.Key words: universalism, particularism, ethical decision-making, marketing,cultural differencesChapter One Introduction1.1 Statement of the ProblemToday, it is difficult to pick up a newspaper or magazine that does not contain stories about questionable business behaviors, especially about the questionable marketing practices. Vitell, Lumpkin and Rawwas (1991)state, “Since marketing is the functional area within business that interfaces with the consumer, it tends to come under the greatest scrutiny, generates the most controversy and receives the most criticism with respect to potentially unethical business practices. Advertising, personal selling, marketing research and international marketing are all the subjects of the most frequent ethical controversy.”(p.366)Concurrently, research examining ethical issues of the marketing has increased dramatically in the last decade. Within this general stream of research on marketing ethics, ethical decision-making (EDM) has been identified as one of the major topics of interest. In a review article of the EDM literature, Ford and Richardson (1994) cited 62 articles investigating variables which have been hypothesized to influence ethical beliefs and behaviors. These variables are categorized into individual and situational factors. Variables that are related to the individual factors include nationality (i.e., culture), religion, sex, age, education, employment, and personality. Situational variables include referent groups, rewards and sanctions, codes of conduct, type of ethical conflict, organizational effects, industry, and business competitiveness. However, as more and more firms operate globally, an understanding of the effects of cultural differences on ethical decision-making becomes increasingly important for avoiding potential business pitfalls and for designing effective international marketing management programs.The concept of culture recognizes that individuals from different backgrounds are exposed to different traditions, heritages, rituals, customs, and religions. All of these factors establish and provide human beings with various learning environments and histories, which in turn cause significant variations in moral standards, beliefs, and behaviors across cultures (Vitell, Nwachukwu, & Barnes, 1993). In other words, culture not only influences learning, but also impacts what is perceived as right/wrong,acceptable/unacceptable, and ethical/unethical. For example, individuals with different cultural backgrounds may view the following terms dramatically differently, such as bribes, sexual harassment, sexual orientation, abortion, individual espionage, and religious beliefs. Failure to recognize these differences across cultures may result in conflicts and negative business consequences.While there are a number of conceptual frameworks for understanding cultural differences, such as the ones proposed by Hofstede (1980), Hall (Samovar, Porter & Stefani, 2000), Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (ibid) and Trompennars and Hampden-Turner (1998),arguably the two most influential and widely known cultural perspectives that have been applied to business management and organization are the one of Hofstede and the one of Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (Dahl, 2004). Both of them have studied people in multinational companies, collected huge databases and then classified nationalities in idealized, typical dimensions of culture.Although there is no dearth of cross-cultural studies of marketing ethics, almost all these ethical studies (both empirical and theoretical) have almost exclusively incorporated Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in defining or describing national culture to the exclusion of other contributions from the literature (Gopalan &Thomson, 2003). Contributions made by Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1998) that addressed the impact of cultural dynamic on human relationships have been virtually ignored by the scholars who have investigated the effect of national culture on ethics. This triggers the author of this dissertation to utilize Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner’s cultural dimension to explore the effect of national culture on ethics.1.2 Purpose and Significance of the StudyBased on the above discussion, this study attempts to fill a significant gap by extending the research scope of Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner’s cultural dimensions to the study of ethical decision-making. The emphasis of this study is placed on the impact of the dimension “universalism versus particularism” (or universalism/particularism) on the ethical decision-making process and criteria. More specifically, the primary purposes of this study are: (1) to utilize one of Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner’s cultural dimensions, i.e., “universalism versus particularism”, to explain the cross-cultural differences in ethical perception; (2) to test how “universalism versus particularism” dynamic influences the relative weight given to deontological and teleological evaluations when making ethical judgments and forming ethical intentions.Some argue that ethical issues cannot be the concern of business because business occupies a special place and that it will be impossible to fulfill its functions if it focuses on ethical issues. However, no business can operate purely on the basis of self-interest over the long run. As part of a larger social system, marketers feel the pressure of society’s concerns for truth, honesty, altruism, and respect for human beings. Trust, fairness, honesty, and respect for others are critical values that are essential to business success. The free market system, with its allocation of scarce resources, can and does drive out those who serve less well the needs of customers and the society. If the marketplace’s expectations are not met, the product and the company may go out of existence. To put it bluntly, those individuals who serve only themselves will be replaced by others who serve the needs of the marketplace better. To survive in the long term, business and marketing must operate on ethical grounds.Ethical problems faced by marketing practitioners stem from conflicts and disagreements and they are relationship problems (Chonko, 1995).Each party in a marketing transaction brings a set of expectations regarding how the business relationship should exist and how transactions should be conducted. For example, when you, as a consumer, want to purchase something from a retailer, you bring the following expectations about the transaction: you want to be treated fairly by the retail salesperson; you want to pay a reasonable price; and you want the product to be available as advertising says it will be and in the indicated condition. Unfortunately, your expectations might not be in agreement with those of the retailer. The retail salesperson may not have time for you; or the retailer’s perception of a reasonable price may differ from yours; or the advertising of the product may be misleading. In such situations, ethical conflict occurs as one individual believes that his or her duties and responsibilities to one group (e.g., the retail salesperson’s responsibility to the store) are inconsistent with his or her duties and responsibilities to another group (e.g., the retail salesperson’s responsibilities to the customer) or to himself or herself. Simply put, people will often disagree about which action is best in a given situation.Internationally, these ethical problems will become more complicated as different cultures clash. The significance of ethics and its impact on successful marketing should be amplified in the international context, particularly when the parties involved hold different sets of cultural values. Moreover, a firm expanding its operation to other countries by direct investment or joint venture will inevitably face ethical dilemmas that may not be encountered in familiar, domestic markets. Thus MultinationalCorporations’ ethical capability—organization’s capability to identify and respond effectively to ethical issues in a global context—is a sustainable source of competitive advantage (Buller & McEvoy, 1999). As we know, with the accelerated race of globalization, economic interdependence and interaction between countries are becoming ever stronger. In this massive tide of economic globalization, no country can develop and prosper in isolation. Therefore, it would seem important to understand the ethical decision-making processes and criteria of individuals from different cultures, and how differences in cultural values may affect decision-making processes and criteria.This study extends the research scope of Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner’s cultural dimensions to ethical decision-making and also shows some distinct patterns in ethical judgment and ethical intention to match universalism and particularism with the relative weight given to deontological and teleological evaluations. Findings from this study will allow international firms to better identify the inherent cultural differences which lead to different perceptions of ethical dilemmas of employees and to adopt effective sales management practices appropriate for those differences. Considering that individuals with different cultural backgrounds possess different ethical standards, some marketing practices might be perceived as ethical by some marketing practitioners and unethical by others. Therefore, a greater understanding of how cultural differences affect EDM across employees in different countries will allow international firms to formulate and adopt appropriate management practices that better safeguard against potential unethical behaviors.In addition, the present situation of China indicates that it is necessary to compare the differences in ethical decision-making between China and the U.S. China has learnt from her long history that isolation leads to backwardness. Development, progress and prosperity could only be achieved through opening to and integrating with the outside world, through stepping up exchanges and cooperation with other countries and through absorbing all fine results of human civilization. According to China Statistical Yearbook 2004, China’s share of world trade increased from about 1% to almost 6% between 1979 (when China started to open up) and 2003; China’s share of global inflows of foreign direct investment was almost 10% in 2003 (US $53 billion of a world total of US $560 billion) and China had 200,000 firms that were either foreign affiliates or funded from foreign sources, which made China the world’s largest recipient of FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) in 2003. And the USA is the top source countries forChina’s FDI. In fact, China’s economic interactions with the other nations not only lie in FDI inflows but also outward FDI flows. China is now increasingly visible as a foreign investor and the USA’s share of China’s outward FDI becomes greater and greater. In 2003, China overtook the US and became the 6th largest outward investor among developing countries. Given the country’s rapid economic development and the government’s interest in encouraging outward FDI, China might emerge as a large source of FID in the near future. UNCTAD’s (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) Global Investment Prospects Assessment Survey found that a number of Investment Promotion Agencies (IPAs) ranked China as a possible top source of FDI during 2004-2007 (/TEMPLATES/webflyer.asp).1.3 OutlineThere are five chapters in this dissertation. The first chapter is introduction, which covers the purpose and significance of the study as well as the outline of this dissertation. Chapter Two is a review of relevant literatures; both theoretical and empirical perspectives are considered. In this chapter, the author firstly describes the definitions of three key terms in this study, i.e., culture, ethics, and ethical decision-making in marketing, and then states the relationship between culture and ethical decision-making. Secondly, a number of studies related to cultural differences are briefly reviewed. After that, the dissertation gives a general description of Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner’s seven cultural dimensions. Thirdly, the three major stages of ethical decision-making, i.e., ethical perception, ethical judgment, and ethical intention, are introduced. Finally, the relevant theoretical and empirical studies are reviewed. In Chapter Three Research Methodology, the author first advances the research hypotheses based on the literature review. And then the methodological procedures which will be used to test the hypotheses are presented. Chapter Four contains the results of the research and a comprehensive discussion of the results. Chapter Five is a conclusion chapter that will present the major findings, limitations of the study, implications for future studies and marketing practitioners.Chapter Two Literature Review2.1 Culture and Ethical Decision-Making2.1.1 CultureCulture is an umbrella word that encompasses a whole set of implicit, widely shared beliefs, traditions, values and expectations that characterize a particular group of people. Giving a definition to “culture” is not as easy as it sounds. “Culture is ubiquitous, multidimensional, complex and all-pervasive.” (Samovar, Porter & Stefani, 2000, p.36) Anthropologist, sociologist, psychologist, philologist, and so on—all kinds of experts or scholars have attempted to give a definition to culture.Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952), in their extensive literature review, listed over one hundred definitions of culture in an effort to develop one that would be acceptable to a range of social scientists. They defined culture as “…patterns, explicit and implicit, of and for behavior acquired and transmitted by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievement of human groups…the essential (i.e., historically derived and selected) ideas and especially their attached values” (p.357).Hofstede (1984)refers to culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes one human group from another…the interactive aggregate of common characteristics that influence a human group’s response to the environment” (p.21). Besides, Hofstede (1994) proposes a set of four layers of culture, each of which encompasses the lower level, as it depends on the lower level, or is a result of the lower level. At the core of Hofstede’s model of culture are values, or in his words, “broad tendencies to prefer certain states of affairs over others”(Hofstede, 1994, p. 8). These values form the most hidden layer of culture. Values as such represent the ideas that people have about how things ought to be. In this way, Hofstede (1994) emphasizes the assumption that “values are strongly influencing behaviors” (p.9).Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1998) state that “culture is the shared ways in which groups of people understand and interpret the world…culture has three layers: (1) explicit products; (2) norms and values; (3) assumptions about existence” (p.20). Among these three layers, values determine the definition of “good and bad”, andtherefore are closely related to the ideals shared by a group and the basic assumptions in the third layers are somewhat similar to values in Hofstede’s model, a lower level of values, i.e. basic assumptions are the absolute core values that influence the more visible values in the layer above (Dahl, 2004).In the book International Business Culture, the author Mitchell (2000)gives us a formal definition “Culture is a set of learned core values, beliefs, standards, knowledge, morals, laws, and behaviors shared by individuals and societies that determines how an individual acts, feels, and views oneself and others” (p.4). Mitchell (2000) defines culture in terms of its components, he believed that “to view a country’s culture from the outside can be intimidating, but breaking it down into its components and understanding how each component is related to the whole can help to unwrap the enigma and provide some logic and motivation behind behaviors, including business behaviors”(p.5).The common thread throughout the above various definitions is the acknowledgment of differences in values and behaviors across different cultures. From these definitions we can see that culture has both physical and nonphysical components. The physical aspects of culture are tangible and functional, such as music, crafts, artistic objects, poetry and arts. The nonphysical aspects of culture constitute the mental values which people use to characterize their environment and view their relationships with nature. These cultural characteristics differentiate one group of people from another.In addition, we should also be aware that there is a significant debate about what level of analysis is desirable for the concept of culture to be a viable tool (Dahl, 2004).In more practical terms, national boundaries have been the preferred level of resolution, and therefore countries or nations are considered as the preferred unit of analysis. Just as Adler (1997) observes, “national boundaries are implicitly accepted as operational definitions of culturally distinct units in cross-cultural management research” (p.31).There are several good arguments for this: Firstly, the nationality of a person can easily be established, whereas membership of a sub-culture is more difficult to establish, particularly in cases where individuals may declare themselves members of various sub-cultures at the same time. The use of nationality is therefore avoiding unnecessary duplication and removes ambiguity in the research process, as the nationality of a person can usually be established easily. Secondly, there is considerable support for the notion that people coming from one country will be shaped by largely the same valuesand norms as their co-patriots (Hofstede, 1991). In fact, nearly all the empirical cross-cultural studies on ethics (e.g., Singhapakdi, Vitell, & Leelakulthanit, 1994; Armstrong & Sweeney, 1994; Karande, Shankarmahesh, Rao, & Rashid, 2000) have utilized nationality as a proxy of culture. Therefore, this dissertation was no exception and used two countries (i.e., China and the U.S.A.) as the surrogates of the cultural dimension universalism/particularism.2.1.2 Ethical Decision Making in Marketing2.1.2.1 Definition of Ethics“Unethical” acts were committed throughout history: Christianity has Adam eating the forbidden fruit, Cain murdering his brother. The majority of the ancient Greek philosophers devoted much of their time to developing theories of ethics. The early theories studied ethics from a normative perspective, meaning that they were concerned with “constructing and justifying the moral standards and codes that one ought to follow” (Vitell, 1986, p.4). On the other side, a positive perspective of ethics attempted to describe and explain how individuals actually behave in ethical situations.One of the major preoccupations of ethical theorists was to create a definition of ethics. As with the majority of concepts, ethics was defined differently by different theorists.Runes states that “ethical behavior refers to ‘just’ or ‘right’ standards of behavior between parties in a situation” (qtd. in Beu & Buckley, 2001, p.59). On the same line, Barry defines ethics as “the study of what constitutes good and bad human conduct, including related actions and values” (ibid).According to DeGeorge(1982), ethics is the study of morality. He argues: Morality is a term used to cover those practices and activities that areconsidered importantly right and wrong, the rules which govern thoseactivities and the values that are imbedded, fostered, or pursued by thoseactivities and practices. The morality of a society is related to its mores or thecustoms accepted by a society or group as being the right and wrong ways toact as well as to the laws of a society which add legal prohibitions andsanctions to many activities considered to be immoral (pp. 13-15).Similarly, Taylor defines ethics as “…inquiry into the nature and grounds of morality where the term morality is taken to mean moral judgments, standards, and rules of conduct” (qtd. in Akaah, 1996, p.606). Ferrell and Fraedrich(1991) describe it as “the study and philosophy of human conduct with an emphasis on determination ofright and wrong” (p.4).In the book Ethical Marketing Decisions, Laczniak and Murphy (1993) wrote, “ethics is one of those subjects where people cannot say anything of substance without revealing quite a bit about their own values and it has two dimensions” (p.10). First, ethics, via its foundation in moral philosophy, provides various models and frameworks for handling ethical situations (Laczniak & Murphy, 1993). That is, there are various approaches to ethical reasoning. For instance, ethics leads us to consider whether we should judge the moral appropriateness of business decisions based on the consequences for various stakeholders or on the basis of the intentions held by the decision-maker when a particular action is selected. Differing approaches may lead us to similar conclusions or divergent conclusions about the “ethicalness” of a particular action. The second dimension of ethics refers to ethics as the right thing to do (ibid). When people say that someone is acting ethically, they usually mean individuals are doing what is morally correct.From the above definitions, we can see the underpinning for having a feeling about what one ought to do comes mostly from our values. Carroll (1996) points out that “ethics is a set of moral principles that drives behavior… Values are the individual’s concepts of the relative worth, utility or importance of certain ideas. ...One’s values, therefore, shape one’s ethics.” (pp. 133-134)2.1.2.2 Ethical Decision Making in MarketingVitell (1986) applied Taylor’s definition of ethics to define marketing ethics as “an inquiry into the nature and grounds of moral judgments, standards, and the rules of conduct relating to marketing decisions and marketing situations.” (p.4) Marketing ethics examines systematically marketing and marketing morality related to 4P-issues, such as unsafe products, deceptive pricing, deceptive advertising, bribery, or discrimination in distribution (Smith & Quelch, 1993).Research on marketing ethics can be divided into six categories: causes of unethical behavior; the relationship between ethical behavior and profitability; social marketing ethics; surveys of various publics; development of normative ethical theories; and ethical decision-making. Within this stream of research on marketing ethics, ethical decision-making has been identified as one of the major topics of interest(Lu, Rose & Blodgett, 1999).Ethical decision-making is a subset of business decision-making because not all the business decisions have ethical ramifications. It is actually the business decision-makingwhen ethical considerations are involved. According to Holt (1990), decision-making is the process of identifying problems and opportunities, developing alternative solutions, choosing a preferred alternative, and then implementing it. When making a decision, the decision maker reaches a conclusion based on the evaluation of options or alternatives. Therefore, ethical decision-making can be defined as a process of choosing a course of action based on what is right and fair in and of itself, or for the common good.For the purpose here, ethical decision-making refers to discretionary decision-making behavior, which “determines how conflicts in human interests are to be settled and …optimizes mutual benefit…for people living together in groups” (Rest, 1986, p.1). Ethical decision-making in marketing refers to the process of making marketing decisions when ethical dilemmas are involved. In business firms, marketing is the most visible functional area because of its frequent interfaces with the customers. Most marketing decisions have ethical ramifications whether business executives realize it or not. When the actions are taken properly, the ethical dimensions go unnoticed and attention centers upon the economic efficiencies and managerial astuteness of the decisions. But such is not always the case. When a marketing decision is ethically troublesome, its highly visible outcomes can be a public embarrassment or even worse.Just as the process of business decision-making, the ethical decision-making process begins when an individual recognizes an ethical dilemma. Subsequently, the individual makes judgments and forms behavioral intentions that are thought to be predictive of actual behavior.2.1.3 Relationship between Culture and Ethical Decision-Making in MarketingFrom the above definition of ethical decision-making in marketing, we know that to explore the relationship between culture and ethical decision-making in marketing is actually to explore the relationship between culture and ethical decision-making.Matthew wrote “What good will it be...[to gain] the whole world, yet [forfeit one’s] soul? Or what can [one] give in exchange for [one’s] soul?” (qtd. in Chonko, 1995, p.4) This statement is at the heart of ethical decision-making, as is the following verse from Taoism: “[One] who stands on tiptoe doesn’t stand firm. [One] who rushes ahead doesn’t go far. [One] who tries to shine dims [one’s] own light” (ibid). These two statements imply gains and losses from actions. Actions imply a choice between alternative courses of action. Evaluating those alternative courses of action implies weighing the pros and cons of each alternative as seen by the individual and as seen by others with whom the individual interacts. These choices form the heart of the problems。

现代性与其批判:普遍主义和特殊主义的问题酒井直树(一)我可以预言,将得到的结论认为后现代,即现代的一个他体,以我们的"现代"话语是不能够加以界定的。

尽管如此,问一问究竟是什么东西构成了现代与后现代之间的隔离也不会毫无意义的。

我们可以提问什么构成了我们能够讨论现代的基础?同样的道理,对待现代的另外一个他体,即前现代,也必须以在许多情况下加以界定的现代性为参照。

前现代-现代-后现代这一系列似乎给人一个纪年性顺序的印象。

然而,必须记住这个顺序从来都不是与世界的地缘政治的格局截然分开的。

时至今日,人们都已十分熟知,这个基本上19世纪的历史图式(scheme)提供了一种视角,通过它来系统地理解各个国家、文化、传统与种族所处的位置。

虽然最后一个术语,即后现代,是不久以前才出现的,前现代与现代这种历史-地缘政治的对应一直是学术界话语的主要组织装置(organizing apparatus)之一。

第三个莫名其妙的术语--后现代--的出现,也许与其说是证明一个时代到另一个个时代的过渡。

不如说是证明我们的话语业已受到了变动或转换。

其后果则是,这一历史一地缘政治的对应(前现代与现代)的所谓的不容置疑性,越来越站不住了。

当然,这两个对应物的有效性并不是第一次受到挑战。

然而,令人惊异的是,它们居然经受住了许多挑战。

如果认为它终于被证明为不起作用,那就未免期望太高。

无论是作为一些社会经济的条件还是作为一个社会对它所选择的价值观念的依附,如果不参照前现代与现代这一配对,就无法理解"现代性"这个术语。

从历史的角度看,"现代性"基本上是与它的历史先行者对立而言的;从地缘政治的角度看,它与非现代、或者更具体地说,与非西方相对照。

因此,前现代与现代这一配对是作为一种话语性的图式(dscursive scheme),依据此配对一个历史的谓语可以被翻译成一个地缘政治的谓语,反之亦然。

关于默顿规范研究的简述摘要:默顿规范被提出之后就受到了学界的关注。

在默顿工作的基础上,默顿学派的其他成员又对这一科学规范做出了不同程度的修正与补充。

但随着科学自身发生变化以及科学哲学新思想的出现,学界开始对默顿规范进行反思与批评。

笔者在所掌握的资料的基础上,试简述这两方面的研究成果。

关键词默顿规范继承拓展批评默顿(R.K.Merton)的博士论文《十七世纪英格兰的科学、技术与社会》开启了当代科学社会学研究的先河,因此默顿也被尊称为“科学社会学之父”。

1942年,默顿在《论科学与民主》一文,从科学作为一种社会建制的视角,系统地阐述了科学的精神特质即科学活动应遵循的四条规范——普遍主义、公有性、无私利性和有组织的怀疑主义,学界将这四条规范统称为默顿规范。

作为默顿科学社会学理论的核心组成部分,默顿规范自被提出之日就在学界引起了巨大而广泛的影响,得到了默顿学派不同程度的继承与扩展,可是随着科学和科学哲学新思想的发展,也有学者对默顿规范进行了质疑与否定。

本文试图在所掌握的资料的基础上,整理学界对默顿规范的发展、和对默顿规范的质疑及默顿学派的回应的相关思想。

一默顿规范的提出背景与内容(一)默顿规范提出的时代背景在1938年的《科学与社会秩序》一文中,默顿就认为对科学的敌意可能产生于两类条件,“第一类条件属于逻辑性的,尽管不一定是经验证实的结论,即认为科学的结构或方法不利于满足重要价值的需要;第二类条件主要包括非逻辑性因素,它基于这样一种感觉即包含在科学的精神特质中的情感与存在于其他制度中的情感是不相容的[1]”。

并指出“1933年之后的纳碎德国的情况即表明了改变或消弱科学活动的逻辑和非逻辑因素共同作用的方式。

在一定程度上,对科学的妨碍是政治结构和民族主义信条变化出乎意料的副产品[2]”。

纳粹主义“按照种族纯洁性的信条,在大学和科研机构中强行规定了这样的政治标准,即必须:出身于‘雅利安’家族并且公开赞同纳粹的目的,实际上所有不能达到这一标准[1] R.K.默顿.鲁旭东、林聚任译.科学社会学[M].北京:商务印书馆,2003:345[2] R.K.默顿.鲁旭东、林聚任译.科学社会学[M].北京:商务印书馆,2003:345的人都被排斥在大学和科研机构之外[1]”,这种种族清洗的结果就是消弱了德国的科学。

莫顿提出的科学家的社会规范内容

莫顿提出的科学家的社会规范的有四种:

(1)普遍主义.

普遍主义表现在关于真相的断言,无论其来源如何,都必须服从于先定的非个人性的准则,即要与观察和以前被证实的知识相一致。

普遍主义提出了判断科学知识真理性的一个重要准则:必须通过观察获得科学事实和先前的经过检验的知识一致,而不是以个人的标准而改变。

(2)公有性。

公有性要求科学家把自己的科学成果公开,“科学发现应该交流”。

由于科学成果具有社会合作性和历史积累性,因此,科学发现都应该成为人类的共同财产。

(3)无私立性。

要求科学家为“科学的目的”从事科学研究,在研究中坚持求真求实的精神,在工作中坚持正直、城市,对科学负责,对同行负责的品格。

莫顿指出,科学活动中虚假的主张,欺骗的行为和不负责任的态度与这种规范要求是不相容的。

(4)有组织的怀疑。

它提倡一种怀疑的精神,该规范要求科学家在工作中保持审慎的态度,对所有的知识,不管他的来源如何,在其成为确证无误的知识之前,都应经过思考,都可以作追问,不应该盲目推崇。

跨国破产中的地方主义与普遍主义跨国破产是全球化过程中不可避免的经济法律现象,而且正越来越多地吸引国际社会和各个国家的注意力。

诚然,一个成功的跨国破产应该形成双赢的结果,使各方位于各个国家的财产价值达到最大化。

因此,跨国破产法存在的价值和目的就是在保持各个国家国内的破产秩序和促进国际合作之间寻求平衡,而这很大程度上取决于每个国家所选择的特定的理论原则。

从传统的地方主义和普遍主义到合作的地方主义和修正的普遍主义再到新实用主义,我们可以看出在地方主义和普遍主义之间存在着妥协和整合化的趋势。

基于地方主义和普遍主义的理论讨论,逐一分析地方主义、普遍主义以及新实用主义,在总结出优缺点的基础上深入研究跨国破产的未来发展方向和合适出路。

标签:跨国破产;地方主义;普遍主义;公平;国家主权1跨国破产的理论分析自从2008年经济危机爆发,全球各个国家的经济都处于急剧倒退的状态。

不良资产显著增长,跨国破产案例接踵出现,最为我们熟知的就是雷曼兄弟破产案件。

近年来,学者们从未停止对解决跨国破产问题最优方案的探索,他们致力于分析地方主义、普遍主义和新实用主义中到底哪一个是最符合实践的。

以加利福尼亚大学的LynnM.LoPucki教授为代表的地方主义支持者和以得克萨斯大学的JayL.Westbrook教授为代表的普遍主义支持者从不同角度深入分析了上述理论问题,他们主要把关注点放在平衡性的因素上,例如公平、国家主权以及可预测性。

1.1地方主义在经济全球化的过程中遭到了诸多诟病推行地方主义的根本原因是显而易见的,那就是保护国家主权。

因为每个国家都希望拥有对当地财产的处置权,以保护本地债权人的利益不受到他国程序的干扰。

然而在经济全球化的环境中,复杂的财产关系和管辖权需要站在国际化的角度达成和谐。

地方主义遭到诟病主要由于它有四个缺点:一是由于各国国内破产法在优先政策等方面潜在的矛盾,可能会造成文件的重叠交杂和债权人的权利无法实现;二来,如果每个国家都想实现本地债权人利益的最大化,那么这不仅将使从整体上重整债权人的利益的可能性化为虚有,而且将极大地增加破产过程中的花费;再者,富有经验且行动迅速的债权人往往会将自己的财产在各个国家之间转移以期使他们资产在每个国家的价值最大化,所以当破产程序启动的时候很难预测财产所在的位置。

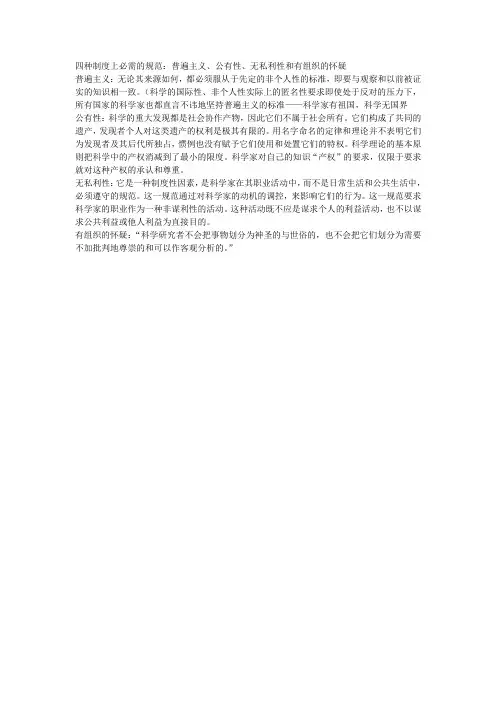

四种制度上必需的规范:普遍主义、公有性、无私利性和有组织的怀疑

普遍主义:无论其来源如何,都必须服从于先定的非个人性的标准,即要与观察和以前被证实的知识相一致。

(科学的国际性、非个人性实际上的匿名性要求即使处于反对的压力下,所有国家的科学家也都直言不讳地坚持普遍主义的标准——科学家有祖国,科学无国界

公有性:科学的重大发现都是社会协作产物,因此它们不属于社会所有。

它们构成了共同的遗产,发现者个人对这类遗产的权利是极其有限的。

用名字命名的定律和理论并不表明它们为发现者及其后代所独占,惯例也没有赋予它们使用和处置它们的特权。

科学理论的基本原则把科学中的产权消减到了最小的限度。

科学家对自己的知识“产权”的要求,仅限于要求就对这种产权的承认和尊重。

无私利性:它是一种制度性因素,是科学家在其职业活动中,而不是日常生活和公共生活中,必须遵守的规范。

这一规范通过对科学家的动机的调控,来影响它们的行为。

这一规范要求科学家的职业作为一种非谋利性的活动。

这种活动既不应是谋求个人的利益活动,也不以谋求公共利益或他人利益为直接目的。

有组织的怀疑:“科学研究者不会把事物划分为神圣的与世俗的,也不会把它们划分为需要不加批判地尊崇的和可以作客观分析的。

”。

科学的规范结构〔美〕R.默顿一、科学与社会对科学完美性的持续批评使科学家们意识到,他们不能超越于特定类型的社会结构。

科学家协会的宣言和声明都关注科学与社会的关系。

受到抨击的科学制度必须重新考虑它的基础,重审它的目标,寻找它的基本原则。

危机唤起了自我评估。

既然科学家的生活方式受到了挑战,他们也就对敏感的自我意识状况有了警觉:自我意识作为一种社会的整合性因素,有其相应的责任和旨趣。

当象牙塔之墙受到长期攻击时,它就变得摇摇欲坠了。

在一个长久的相对稳定的时期里,对知识的追求和传播占有主导地位,即使这种追求在这一文化价值中没有占据第一位的话,科学家也要表明,科学是为人类谋福的一种方式。

因此他们绕了整整一圈后, 又回到了科学在现代世界出现时的起点。

三个世纪之前,当科学制度刚刚能够宣称独立并且还需要社会支持时,自然哲学家便做出承诺:从文化上看,科学既能保证有效地实现经济功利目的,又是颂扬上帝的手段。

科学的这一目标当时并无自我证明的价值。

但随着无数成就的取得,工具变成了目标,手段变成了目的。

这方面进一步强化的结果是,科学家们认为他们独立于社会,并认为科学是社会的独立存在的事业,而不是社会中的一部分。

但对科学自治性的当头一击,使这种乐观的独立主义转变为现实地参与到文化的革命性冲突之中。

这种问题的提出导致了对现代科学精神特质的明确化和重新肯定。

科学是一个难以概括的词语,它所指的是一些不同的、尽管是相关的事项。

它通常被用于指(1)一套特定的方法,知识的证实依靠这套方法;(2)通过应用这些方法所获得的一些积累性的知识;(3)一套支配所谓的科学活动的文化价值和惯例;或者(4)上述任何方面的组合。

我们这里所考虑的是科学的文化结构的一个基本形式,即科学作为一种制度的一定方面。

西方普遍主义的内在困境与外在尴尬——读马德普博士的近作《普遍主义的贫困——自由主义政治哲学批判》高建、佟德志海通以来,中国思想界绵延不绝的“中—西”、“体—用”之争即引人瞩目,串起了一条明暗起伏的主线,在时空转换的场景中铺开了中国近代化的道路。

当现代化以经济市场化和政治民主化以及各民族之间的文化交流为内容布下全球化之幕时,在一系列两分法之间进退的中国思想界更是将普世伦理与地方知识的争论推向白热化。

斟酌此番背景,兼及西方政治文明的强势扩张,马德普博士的这部《普遍主义的贫困——自由主义政治哲学批判》①(以下称《普遍主义的贫困》)就不只是义理的辨析和学术的探讨,而是充满了对现实的热切关怀和深层忧虑。

从学理层次出发,自由主义成为我国西方政治思想研究的一个热点,学界围绕着这一学说不但形成了影响重大的思想争论,而且完成了大量的研究成果。

李强教授的《自由主义》一书成为这一研究的起点,而应奇教授所著《从自由主义到后自由主义》则考察了这一思潮的最新发展。

除此而外,吴春华教授主编《当代西方自由主义》,石元康教授所著《当代西方自由主义理论》对当代西方的自由主义进行了重点研究;丛日云教授所著《在上帝与恺撒之间——基督教二元政治观与近代自由主义》、郁建兴教授所著《自由主义批判与自由理论的重建》则侧重了对自由主义发展历史的考察。

另外,顾肃所著《自由主义基本理念》等一些著作均在一定程度上推动了国内的自由主义研究。

然而,从普遍主义角度对自由主义进行研究的成果并不多见,马德普博士的《普遍主义的贫困》无疑填补了这一空白。

围绕着西方普遍主义的世界观、价值观和方法论,《普遍主义的贫困》全面地梳理了西方普遍主义经历的本体普遍主义、价值普遍主义以及规范普遍主义三个阶段,并集中对自由主义普遍主义进行了考察,还分析了历史主义、价值多元主义的兴起对自由主义普遍主义的冲击。

以自由主义普遍主义为重心,本书所展①开的不仅仅是对自由主义本身困境与悖论的理性反思,而且还进一步深入地分析了自由主义向外扩张时所表现出来的傲慢与偏见,揭示了殖民主义、帝国主义以及霸权主义等理论与实践的思想根源。

论施特劳斯用普遍主义对历史主义的替代[摘要]在施特劳斯的视域中,历史主义所带来的矛盾与冲突实际上并不是来自现实中的历史实践,而是来自于历史主义完全摒弃了普遍主义中的那些恒定性,而这些恒定的东西必须由社会精英来发现。

所以说这种说法其实就是否认了历史主义在现实生活中的决定性作用,并且进一步确定了普遍主义能够给现实生活带来极大益处这一思想。

但是,这种做法的可行性却值得我们深究。

[关键词]普遍主义;历史主义;自然正当根据历史主义解决现代性问题的逻辑,化解人们在道德与价值上的冲突的思路主要在于人们通过一定的具体的行动来使得人们找到他们各自认为更加适合自己的正义与价值,这就需要对社会实践加以改变,这种社会实践包括经济发展状态、生活方式等;而根据普遍主义来解决现代性问题的逻辑,化解人们在道德与价值上的冲突,则需要哲学家在哲学上的努力,重新发掘自然正当,找到一种普遍的正义与价值,使这种正义与价值能够重新引领政治生活,从而解决众多的现代性问题。

施特劳斯选择了后者,也就是说,由于认为现代社会中的众多在道德和价值上的冲突实际上就是由历史主义所引起的,所以在施特劳斯看来,现代性困境问题的解决则应通过一场对古典政治理性主义的反思来完成。

正是根据这个思路,施特劳斯才要求要重新重视起哲学家在现代社会中的地位,由此来重新“恢复政治哲学”;由此我们可以看到在这种思想之下,哲学家的重要地位就再次摆在了人们面前,但是这种思想导致的另一个结果就是精英主义,这种思想主张现代社会中的正义与价值的确定工作应当交给哲学家这样的社会精英来完成。

施特劳斯希望,在现代政治生活中应当由应当由社会精英来占主导地位,而不是世俗大众或者少数仅仅拥有权力和金钱的人,从而能够避免现代西方民主自由主义所带来的使社会失范的巨大风险。

我认为,不管是施特劳斯所提出的回归普遍主义原则,还是这种社会精英理论所存在的一个重大问题就是其在现在社会中是难以操作的,所以施特劳斯才会希望能够找到一种无限接近自然正当的价值体系,也就是说,真正的能够适应现代政治生活,或者说能够被现代政治生活所适应的这种价值体系是根本不存在的,是虚无飘渺的。

科学共同体及其规范如下:

1、普遍主义。

即深信科学的真理具有客观性和普遍性,是放之四海而皆准的;

2、公有主义。

及承认科学发现本质上是社会合作的产物,它属于复整个科学共同体以至社会,科学家无权独占或收回他的科学发现,科学发现奉行公开原则,科学家得到发明权;

3、不谋私利的精神。

即主张科学家应当把认识自然奥秘和追求真理作为科学探索的制主要动力,仅仅在次要的意义上才把从事科学研究工作作为谋生的手段;

4、有条理的怀疑精神。

科学家决不应不经任何分析批判而盲目接受任何东西,应按照一定规范合理地怀疑现存的事物。

科学家有责任评价其他科学家的科研成果,也要允许别人对自己的成果怀疑。

苏格拉底普遍主义伦理学作者:屈雪姣来源:《青年与社会》2013年第04期[摘要]苏格拉底伦理学的普遍意图是在普遍性定义探求事物的普遍本质,苏格拉底所探讨的“美德即知识”这一命题,通过实践智慧把握事物的本质,由于美德与知识各自都有不同含义,对这一命题具有多种解释,但苏格拉底从普遍主义的角度对美德即知识做出了深入探讨,对现代生活产生了深远的影响。

[关键词]普遍主义;美德即知识;影响一、苏格拉底伦理学的理论意图苏格拉底普遍主义伦理理论是针对于古希腊智者学派所认同的相对主义而论的,智者学派所注重的是对自然本身的研究,而这种层面只停留在感性阶段,认为一切感性事物都处于永远流动之中,并且关于他们不能有任何的知识,不会以知识为基发点,对此苏格拉底本人的思绪中存在许多的疑惑,他所考虑的是‘事物是什么’也就是说的事物的本质,正式这种提问的方式,以概念的形式正名,揭示了一类事物的本质属性,要求概念有内涵与外延,从而阐明这类事物的因果本性,也就是苏格拉底所说的理性的知识,这种普遍性的定义也就是针对早期希腊哲学中的直观思想与独断倾向,要求人以理性的思维来探究事物的本质,而不是智者所认为“人是万物的尺度”的主观意识决定了你所认识一切,一定程度上,这些概念是人为约定俗成的,可以说“公说公有理,婆说婆有理”并没有确定的意义。

苏格拉底这里才根本改变了这种状况,转变成为对社会伦理和人的研究。

苏格拉底伦理学的普遍意图是在普遍性定义探求事物的普遍本质,这是和现象中流动变异的事物是有所不同的东西。

而明确肯定理性知识在人的道德行为中的决定作用,这是古希腊以至整个西方哲学中首次建立起来的一种理性主义道德哲学,从某种意义上讲,就是赋予道德价值以客观性确定性,普遍规范性。

意识到人们是以其特有的方式来理解世界,开始学会对自己的思维活动进行反思而不盲目相信自己智慧的客观性。

因此,黑格尔说:在苏格拉底身上,思维的主观性已经更确切的更透彻的被意识到了。