Leontief paradox

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:412.00 KB

- 文档页数:7

MécaniqueProcédés de mesure1 / 2SphéromètreDETERMINATION DE RAYONS DE COURBURE SUR DES VERRES DE MONTRESUE101010003/16 JSNOTIONS DES BASE GÉNÉRALESLe sphéromètre est constitué d'un trépied avec trois pointes en acier qui forment un triangle équilatéral de 50 mm de côté. Une vis micrométrique avec pointe de mesure passe par le centre du trépied. Une règle graduée verticale indique la hauteur h de la pointe de mesure au-dessus ou au-dessous du plan défini par les pointes des pieds. Le déplacement de la pointe de mesure peut être lu à 1 µm près à l'aide d'une graduation sur un disque circulaire qui tourne avec la vis micrométrique.L'équation suivante décrit le rapport entre l'écart r des pointes des pieds avec le centre du sphéromètre, le rayon de courbure recherché R et la hauteur de bombe-ment h :()222h R r R -+=(1)Après la conversion, on obtient pour R :hh r R ⋅+=222 (2)L'écart r résulte de la longueur de côté s du triangle équi-latéral formé par les pointes des pieds :3sr =(3)Pour R, l'équation est donc la suivante :262h h s R +⋅=(4)Fig. 1: Représentation schématique pour la mesure du rayonde courbure avec un sphéromètreEn haut : coupe verticale pour objet de mesure avec surface convexeMilieu : coupe verticale pour objet de mesure avec sur-face concaveEn bas : vue du hautUE1010100 3B SCIENTIFIC® PHYSICS EXPERIMENT3B Scientific GmbH, Rudorffweg 8, 21031 Hamburg, Allemagne, © Copyright 2016 3B Scientific GmbHLISTE DES APPAREILS1 Sphéromètre de précision 1002947 (U15030) 1 Miroir plan1003190 (U21885)1 Jeu de 10 coupes en verre de montre, 80 mm 1002868 (U14200) 1 Jeu de 10 coupes en verre de montre, 125 mm 1002869 (U14201)MONTAGENote : pour reconnaître que la pointe de mesure du sphé-romètre touche juste la surface de l'objet à mesurer, tour-nez avec précaution la vis micrométrique en observant si le trépied suit le mouvement et que le sphéromètre produit un léger basculement. ∙Nettoyez le miroir plan et les coupes en verre avec un chiffon non pelucheux et en utilisant de l'eau con-tenant un peu de produit de rinçage.∙ Placez le sphéromètre sur le miroir plan et vérifiez la position zéro sur la graduation.REALISATION∙ Posez le grand verre de montre sur une surface lisse avec le bombement tourné vers le haut.∙Placez le sphéromètre par-dessus de manière à ce que la pointe de mesure touche juste la surface du verre.∙ Lisez et notez le bombement h .∙ Placez le verre de montre avec le bombement vers le bas et répétez la mesure.∙Répétez les mesures avec un verre plus petit.Fig. 2: Agencement de la mesureEXEMPLE DE MESURE ET EVALUATIONL'écart des pointes des pieds s du sphéromètre s'élève à 50 mm. Pour de faibles hauteurs de bombements h , (4) peut être simplifié :hh h s R 222mm 4206mm 25006≈⋅=⋅=Tab. 1: Hauteur de bombement mesurée h et rayon decourbure R qui en résulte pour les verres de montres。

3B SCIENTIFIC® PHYSICSIstruzioni per l’uso10/15 ALF1 Spinotto da 4 mm per ilcollegamento dell’anodo2 Anodo3 Supporto4 Spirale riscaldante5 Piastra catodica6 Connettore da 4 mm peril collegamento diriscaldamento e anodo I tubi catodici incandescenti sono bulbi in vetro apareti sottili, sotto vuoto. Maneggiare con cura:rischio di implosione!∙Non esporre i tubi a sollecitazionimeccaniche.∙Non esporre il cavi di collegamento asollecitazioni alla trazione.∙Il tubo può essere utilizzato esclusivamentecon il supporto D (1008507).Tensioni e correnti eccessive e temperaturecatodiche non idonee possono distruggere i tubi.∙Rispettare i parametri di funzionamento indicati.Durante il funzionamento dei tubi, possonoessere presenti tensioni e alte tensioni cherendono pericoloso il contatto.∙Eseguire i collegamenti soltanto congliapparecchi di alimentazione disinseriti.∙Montare e smontare il tubo soltanto con gliapparecchi di alimentazione disinseriti.Durante il funzionamento il collo del tubo siriscalda.∙Se necessario far raffreddare i tubi prima dismontarli.Il rispetto della Direttiva CE per la compatibilitàelettromagnetica è garantito solo con glialimentatori consigliati.Il diodo consente test fondamentali sull´effettoEdison (effetto termoionico), serve perdimostrare la dipendenza della corrente diemissione dalla potenza di accensione delcatodo incandescente, per il rilevamento dellelinee caratteristiche del diodo nonché l’uso deldiodo come raddizzatore.Il diodo è un tubo a vuoto spinto con unfilamento caldo (catodo) in tungsteno puro e unapiastra metallica circolare (anodo) in una sferadi vetro trasparente, sotto vuoto. Catodo eanodo sono disposti parallelamente tra loro.Questa forma costruttiva planare corrisponde alsimbolo del diodo tradizionale. La capacità dipotenza della grande struttura geometrica èstata migliorata fissando una piastra metallicacircolare a una delle guide del filamento caldo,in modo da determinare un campo elettrico piùuniforme tra catodo e anodo.Tensione di accensione: ≤ 7,5 V Corrente di accensione: ≤ ca. 3 A Tensione anodo: max. 500 V Corrente anodo: tip. 2,5 mA conU A= 300 V,U F = 6,3 V CC Lunghezza del tubo: ca. 300 mm Diametro: ca. 130 mm Distanza tra catodo eanodo: ca. 15 mmPer il funzionamento del diodo sono inoltre necessari i seguenti dispositivi:1 Portatubo D 1008507 1 Alimentatore CC 500 V (@230 V) 1003308 oppure1 Alimentatore CC 500 V (@115 V) 1003307In aggiunta si consiglia:Adattatore di protezione bipolare 10099614.1 Inserimento del tubo nel portatubi∙Montare e smontare il tubo soltanto con gli apparecchi di alimentazione disinseriti.∙Spingere completamente all'indietro il dispositivo di fissaggio del portavalvole.∙Inserire il tubo nei morsetti.∙Bloccare il tubo nei morsetti mediante i cursori di fissaggio.∙Se necessario, inserire un adattatore di protezione sui jack di collegamento del tubo.4.2 Rimozione del tubo dal portatubi∙Per rimuovere il tubo, spingere di nuovo all'indietro i cursori di fissaggio e rimuoverlo.5.1 Produzione di portatori di caricamediante un catodo incandescente (effetto Edison) nonché misurazione della corrente anodica in funzione della tensione di accensione del catodo incandescenteSono necessari inoltre:1 Multimetro analogico AM50 1003073 ∙Realizzare il collegamento come illustrato in figura 1. Collegare il polo negativo della tensione anodica al connettore da 4 mmcontrassegnato con il segno meno sul collo del tubo.∙Avviare il test con un riscaldamento freddo (tensione di accensione U F = 0 V).∙Variare la tensione anodica U A tra 0 e 300 V. In pratica non c’è pass aggio di corrente (< 0,1 µA) tra catodo e anodo, anche se in presenza di alte tensioni.∙Applicare una tensione di 6 V al riscaldamento finché diventa caldo.Aumentare gradualmente la tensione anodica e misurare la corrente anodica.∙Riazzerare la tensione di accensione e far raffreddare il riscaldamento. Quindi, con tensione anodica costante, aumentare gradualmente la tensione di accensione e osservare la corrente anodica I A.Con tensione di accensione costante, la corrente anodica aumenta con l’aumentare della tensione anodica.Con tensione anodica costante, la corrente anodica aumenta con l’aumentare della tensione di accensione.5.2 Rilevamento delle linee caratteristichedel diodo∙Realizzare il collegamento come illustrato in figura 1. Collegare il polo negativo della tensione anodica al connettore da 4 mm contrassegnato con il segno meno sul collo del tubo.∙Selezionare la tensione 4,5 V, 5 V e 6 V.∙Determinare la corrente anodica I A per la rispettiva tensione di accensione in funzione della tensione anodica U A. All’uopo, aumentare la tensione anodica in fasi da 40 V a 300 V.∙Riportare in un diagramma le coppie di valori I A- U A per la rispettiva tensione di accensione.Con l’aumentare della tensione anodica, la corrente anodica aumenta fino a raggiungere un valore di saturazione.Con l’aumentare della tensione di accensione, aumenta l’inte nsità della corrente anodica.5.3 Il diodo come raddrizzatoreSono necessari inoltre:1 Resistenza di 10 kΩ1 Generatore di tensione per una tensione di 16 V CA 1 Oscilloscopio∙Montaggio come illustrato in Fig. 3 con U F = 6,3 V e U A = 16 V CA.∙Sull’oscilloscopio osservare l’effetto raddizzante del diodo.Nel circuito anodico del diodo azionato con tensione alternata, è presente una corrente continua determinata dal blocco di una semifase.Fig. 1 Rapporto di dipendenza della corrente anodica dalla tensione di accensione e misurazione della correnteanodicaFig. 2 Linee caratteristiche del diodo. La corrente anodica in funzione della tensione anodicaFig. 3 Il diodo come raddrizzatore3B Scientific GmbH ▪ Rudorffweg 8 ▪ 21031 Amburgo ▪ Germania ▪ 。

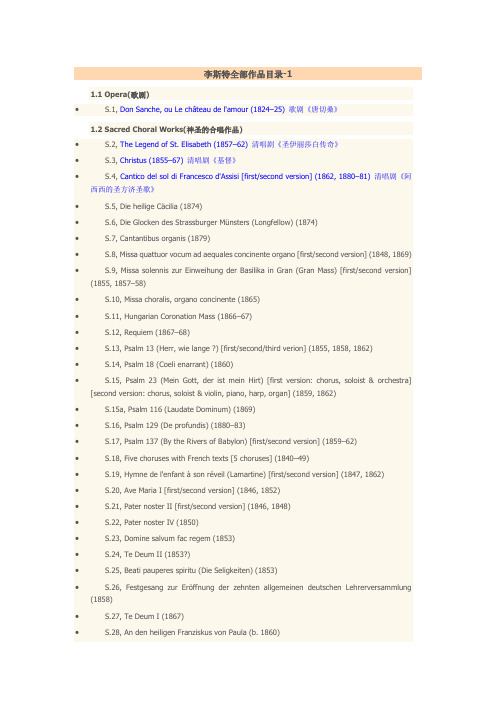

1.1 Opera(歌剧)•S.1, Don Sanche, ou Le château de l'amour (1824–25) 歌剧《唐切桑》1.2 Sacred Choral Works(神圣的合唱作品)•S.2, The Legend of St. Elisabeth (1857–62) 清唱剧《圣伊丽莎白传奇》•S.3, Christus (1855–67) 清唱剧《基督》•S.4, Cantico del sol di Francesco d'Assisi [first/second version] (1862, 1880–81) 清唱剧《阿西西的圣方济圣歌》•S.5, Die heilige Cäcilia (1874)•S.6, Die Glocken des Strassburger Münsters (Longfellow) (1874)•S.7, Cantantibus organis (1879)•S.8, Missa quattuor vocum ad aequales concinente organo [first/second version] (1848, 1869)•S.9, Missa solennis zur Einweihung der Basilika in Gran (Gran Mass) [first/second version] (1855, 1857–58)•S.10, Missa choralis, organo concinente (1865)•S.11, Hungarian Coronation Mass (1866–67)•S.12, Requiem (1867–68)•S.13, Psalm 13 (Herr, wie lange ?) [first/second/third verion] (1855, 1858, 1862)•S.14, Psalm 18 (Coeli enarrant) (1860)•S.15, Psalm 23 (Mein Gott, der ist mein Hirt) [first version: chorus, soloist & orchestra] [second version: chorus, soloist & violin, piano, harp, organ] (1859, 1862)•S.15a, Psalm 116 (Laudate Dominum) (1869)•S.16, Psalm 129 (De profundis) (1880–83)•S.17, Psalm 137 (By the Rivers of Babylon) [first/second version] (1859–62)•S.18, Five choruses with French texts [5 choruses] (1840–49)•S.19, Hymne de l'enfant à son réveil (Lamartine) [first/second version] (1847, 1862)•S.20, Ave Maria I [first/second version] (1846, 1852)•S.21, Pater noster II [first/second version] (1846, 1848)•S.22, Pater noster IV (1850)•S.23, Domine salvum fac regem (1853)•S.24, Te Deum II (1853?)•S.25, Beati pauperes spiritu (Die Seligkeiten) (1853)•S.26, Festgesang zur Eröffnung der zehnten allgemeinen deutschen Lehrerversammlung (1858)•S.27, Te Deum I (1867)•S.28, An den heiligen Franziskus von Paula (b. 1860)•S.29, Pater noster I (b. 1860)•S.30, Responsorien und Antiphonen [5 sets] (1860)•S.31, Christus ist geboren I [first/second version] (1863?)•S.32, Christus ist geboren II [first/second version] (1863?)•S.33, Slavimo Slavno Slaveni! [first/second version] (1863, 1866)•S.34, Ave maris stella [first/second version] (1865–66, 1868)•S.35, Crux! (Guichon de Grandpont) (1865)•S.36, Dall' alma Roma (1866)•S.37, Mihi autem adhaerere (from Psalm 73) (1868)•S.38, Ave Maria II (1869)•S.39, Inno a Maria Vergine (1869)•S.40, O salutaris hostia I (1869?)•S.41, Pater noster III [first/second version] (1869)•S.42, Tantum ergo [first/second version] (1869)•S.43, O salutaris hostia II (1870?)•S.44, Ave verum corpus (1871)•S.45, Libera me (1871)•S.46, Anima Christi sanctifica me [first/second version] (1874, ca. 1874)•S.47, St Christopher. Legend (1881)•S.48, Der Herr bewahret die Seelen seiner Heiligen (1875)•S.49, Weihnachtslied (O heilige Nacht) (a. 1876)•S.50, 12 Alte deutsche geistliche Weisen (Chorales) [12 chorals] (ca. 1878-79) •S.51, Gott sei uns gnädig und barmherzig (1878)•S.52, Septem Sacramenta. Responsoria com organo vel harmonio concinente (1878) •S.53, Via Crucis (1878–79)•S.54, O Roma nobilis (1879)•S.55, Ossa arida (1879)•S.56, Rosario [4 chorals] (1879)•S.57, In domum Domino imibus (1884?)•S.58, O sacrum convivium (1884?)•S.59, Pro Papa (ca. 1880)•S.60, Zur Trauung. Geistliche Vermählungsmusik (Ave Maria III) (1883)•S.61, Nun danket alle Gott (1883)•S.62, Mariengarten (b. 1884)•S.63, Qui seminant in lacrimis (1884)•S.64, Pax vobiscum! (1885)•S.65, Qui Mariam absolvisti (1885)•S.66, Salve Regina (1885)• 1.3 Secular Choral Works(世俗的合唱作品)•S.67, Beethoven Cantata No. 1: Festkantate zur Enthüllung (1845)•S.68, Beethoven Cantata No. 2: Zur Säkularfeier Beethovens (1869–70)•S.69, Chöre zu Herders Entfesseltem Prometheus (1850)•S.70, An die Künstler (Schiller) [first/second/third verion] (1853, 1853, 1856)•S.71, Gaudeamus igitur. Humoreske (1869)•S.72, Vierstimmige Männergesänge [4 chorals] (for Mozart-Stiftung) (1841)•S.73, Es war einmal ein König (1845)•S.74, Das deutsche Vaterland (1839)•S.75, Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh (Goethe) [first/second version] (1842, 1849)•S.76, Das düstre Meer umrauscht mich (1842)•S.77, Die lustige Legion (A. Buchheim) (1846)•S.78, Trinkspruch (1843)•S.79, Titan (Schobert) (1842–47)•S.80, Les quatre éléments (Autran) (1845)•S.81, Le forgeron (de Lamennais) (1845)•S.82, Arbeiterchor (de Lamennais?) (1848)•S.83, Ungaria-Kantate (Hungaria 1848 Cantata) (1848)•S.84, Licht, mehr Licht (1849)•S.85, Chorus of Angels from Goethe's Faust (1849)•S.86, Festchor zur Enthüllung des Herder-Dankmals in Weimar (A. Schöll) (1850)•S.87, Weimars Volkslied (Cornelius) [6 versions] (1857)•S.88, Morgenlied (Hoffmann von Fallersleben) (1859)•S.89, Mit klingendem Spiel (1859–62 ?)•S.90, Für Männergesang [12 chorals] (1842–60)•S.91, Das Lied der Begeisterung. A lelkesedes dala (1871)•S.92, Carl August weilt mit uns. Festgesang zur Enthüllung des Carl-August-Denkmals in Weimar am 3 September 1875 (1875)•S.93, Ungarisches Königslied. Magyar Király-dal (Ábrányi) [6 version] (1883)•S.94, Gruss (1885?)1.4 Orchestral Works(管弦乐作品)1.4.1 Symphonic Poems(交响诗)•S.95, Poème symphonique No. 1, Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne (Berg Symphonie) [first/second/third version] (1848–49, 1850, 1854) 第一交响诗山间所闻•S.96, Poème symphonique No. 2, Tasso, Lamento e Trionfo [first/second/third version] (1849, 1850–51, 1854) 《塔索,哀叹与胜利》•S.97, Poème symphonique No. 3, Les Préludes (1848) 第三交响诗“前奏曲”•S.98, Poème symphonique No. 4, Orpheus (1853–54) 第四交响诗《奥菲欧》•S.99, Poème symphonique No. 5, Prometheus [first/second version] (1850, 1855) 第五交响诗《普罗米修斯》•S.100, Poème symphonique No. 6, Mazeppa [first/second version] (1851, b. 1854) 第六交响诗《马捷帕》•S.101, Poème symphonique No. 7, Festklänge [revisions added to 1863 pub] (1853) 第七交响诗《节日之声》•S.102, Poème symphonique No. 8, Héroïde funèbre [first/second version] (1849–50, 1854) 第八交响诗《英雄的葬礼》•S.103, Poème symphonique No. 9, Hungaria (1854) 第九交响诗《匈牙利》•S.104, Poème symphonique No. 10, Hamlet (1858) 第十交响《哈姆雷特》•S.105, Poème symphonique No. 11, Hunnenschlacht (1856–57) 第十一交响诗《匈奴之战》•S.106, Poème symphonique No. 12, Die Ideale (1857) 第十二交响诗《理想》•S.107, Poème symphonique No. 13, Von der Wiege bis zum Grabe (From the Cradle to the Grave) (1881–82) 第十三交响诗《从摇篮到坟墓》1.4.2 Other Orchestral Works(其他管弦乐作品)•S.108, Eine Faust-Symphonie [first/second version] (1854, 1861)•S.109, Eine Symphonie zu Dante's Divina Commedia (1855–56)•S.110, Deux épisodes d'apres le Faust de Lenau [2 pieces] (1859–61)•S.111, Zweite Mephisto Waltz (1881)•S.112, Trois Odes Funèbres [3 pieces] (1860–66)•S.113, Salve Polonia (1863)•S.114, Künstlerfestzug zur Schillerfeier (1857)•S.115, Festmarsch zur Goethejubiläumsfeier [first/second version] (1849, 1857)•S.116, Festmarsch nach Motiven von E.H.z.S.-C.-G. (1857)•S.117, Rákóczy March (1865)•S.118, Ungarischer Marsch zur Krönungsfeier in Ofen-Pest (am 8 Juni 1867) (1870)•S.119, Ungarischer Sturmmarsch (1875)1.5 Piano and Orchestra(钢琴与乐队)•S.120, Grande Fantaisie Symphonique on themes from Berlioz Lélio (1834)•S.121, Malédiction (with string orchestra) (1833) 诅咒钢琴与弦乐队•S.122, Fantasie über Beethovens Ruinen von Athen [first/second version] (1837?, 1849) •S.123, Fantasie über ungarische Volksmelodien (1852) 匈牙利民歌主题幻想曲为钢琴与乐队而作•S.124, Piano Concerto No. 1 in E flat [first/second version] (1849, 1856) 降E大调第一钢琴协奏曲•S.125, Piano Concerto No. 2 in A major [first/second version] (1839, 1849) A大调第二钢琴协奏曲•S.125a, Piano Concerto No. 3 in E flat (1836–39)•S.126, Totentanz. Paraphrase on Dies Irae [Feruccio Busoni's 'De Profundis'/final version] (1849, 1859) 死之舞为钢琴与乐队而作•S.126a, Piano Concerto "In the Hungarian Style" [probably by Sophie Menter] (1885)1.6 Chamber Music(室内乐等)S.126b, Zwei Waltzer [2 pieces] (1832)•S.127, Duo (Sonata) - Sur des thèmes polonais (1832-35 ?)•S.128, Grand duo concertant sur la romance de font Le Marin [first/second version] (ca.1835-37, 1849)•S.129, Epithalam zu Eduard. Reményis Vermählungsfeier (1872)•S.130, Élégie No. 1 [first/second/third version] (1874)•S.131, Élégie No. 2 (1877)•S.132, Romance oubliée (1880)•S.133, Die Wiege (1881?)•S.134, La lugubre gondola [first/second version] (1883?, 1885?)•S.135, Am Grabe Richard Wagners (1883)1.7 Piano Solo1.7.1 Studies(钢琴练习曲)•S.136, Études en douze exercices dans tous les tons majeurs et mineurs [first version, 12 pieces] (1826) 12首钢琴练习曲•S.137, Douze grandes études [second version, 12 pieces] (1837) 《12首超技练习曲》•S.138, Mazeppa [intermediate version of S137/4] (1840) 练习曲“玛捷帕”•S.139, Douze études d'exécution transcendante [final version, 12 pieces] (1852) 12首超技练习曲•S.140, Études d'exécution transcendante d'après Paganini [first version, 6 pieces] (1838) 帕格尼尼超技练习曲•S.141, Grandes études de Paganini [second version, 6 pieces] (1851) 6首帕格尼尼大练习曲•S.142, Morceau de salon, Étude de perfectionnement [Ab Irato, first version] (1840) 高级练习曲“沙龙小品”•S.143, Ab Irato, Étude de perfectionnement [second version] (1852) 高级练习曲“愤怒”•S.144, Trois études de concert [3 pieces] (1848?) 3首音乐会练习曲1. Il lamento2. La leggierezza3. Un sospiro•S.145, Zwei Konzertetüden [2 pieces] (1862–63) 2首音乐会练习曲1. Waldesrauschen2. Gnomenreigen•S.146, Technische Studien [68 studies] (ca. 1868-80) 钢琴技巧练习1.7.2 Various Original Works(各种原创作品)•S.147, Variation on a Waltz by Diabelli (1822) 狄亚贝利圆舞曲主题变奏曲•S.148, Huit variations (1824?) 降A大调原创主题变奏曲•S.149, Sept variations brillantes dur un thème de G. Rossini (1824?)•S.150, Impromptu brilliant sur des thèmes de Rossini et Spontini (1824) 罗西尼与斯蓬蒂尼主题即兴曲•S.151, Allegro di bravura (1824) 华丽的快板•S.152, Rondo di bravura (1824) 华丽回旋曲•S.152a, Klavierstück (?)•S.153, Scherzo in G minor (1827) g小调谐谑曲•S.153a, Marche funèbre (1827)•S.153b, Grand solo caractèristique d'apropos une chansonette de Panseron [private collection, score inaccessible] (1830–32) [1]•S.154, Harmonies poétiques et religieuses [Pensée des morts, first version] (1833, 1835) 宗教诗情曲•S.155, Apparitions [3 pieces] (1834) 显现三首钢琴小品•S.156, Album d'un voyageur [3 sets; 7, 9, 3 pieces] (1835–38) 旅行者札记•S.156a, Trois morceaux suisses [3 pieces] (1835–36)•S.157, Fantaisie romantique sur deux mélodies suisses (1836) 浪漫幻想曲•S.157a, Sposalizio (1838–39)•S.157b, Il penseroso [first version] (1839)•S.157c, Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa [first version] (1849)•S.158, Tre sonetti del Petrarca [3 pieces, first versions of S161/4-6] (1844–45) 3首彼特拉克十四行诗•S.158a, Paralipomènes à la Divina Commedia [Dante Sonata original 2 movement version] (1844–45)•S.158b, Prologomènes à la Divina Commedia [Dante Sonata second version] (1844–45)•S.158c, Adagio in C major (Dante Sonata albumleaf) (1844–45)•S.159, Venezia e Napoli [first version, 4 pieces] (1840?) 威尼斯和拿波里•S.160, Années de pèlerinage. Première année; Suisse [9 pieces] (1848–55) 旅行岁月(第一集)- 瑞士游记•S.161, Années de pèlerinage. Deuxième année; Italie [7 pieces] (1839–49) 旅行岁月(第二集)- 意大利游记•S.162, Venezia e Napoli. Supplément aux Années de pèlerinage 2de volume [3 pieces] (1860) 旅行岁月(第二集补遗)- 威尼斯和拿波里•S.162a, Den Schutz-Engeln (Angelus! Prière à l'ange gardien) [4 drafts] (1877–82) •S.162b, Den Cypressen der Villa d'Este - Thrénodie II [first draft] (1882)•S.162c, Sunt lacrymae rerum [first version] (1872)•S.162d, Sunt lacrymae rerum [intermediate version] (1877)•S.162e, En mémoire de Maximilian I [Marche funèbre first version] (1867)•S.162f, Postludium - Nachspiel - Sursum corda! [first version] (1877)•S.163, Années de pèlerinage. Troisième année [7 pieces] (1867–77) 旅行岁月(第三集)•S.163a, Album-Leaf: Andantino pour Emile et Charlotte Loudon (1828) [2] 降E大调纪念册的一页•S.163a/1, Album Leaf in F sharp minor (1828)降E大调纪念册的一页•S.163b, Album-Leaf (Ah vous dirai-je, maman) (1833)•S.163c, Album-Leaf in C minor (Pressburg) (1839)•S.163d, Album-Leaf in E major (Leipzig) (1840)•S.164, Feuille d'album No. 1 (1840) E大调纪念册的一页•S.164a, Album Leaf in E major (Vienna) (1840)•S.164b, Album Leaf in E flat (Leipzig) (1840)•S.164c, Album-Leaf: Exeter Preludio (1841)•S.164d, Album-Leaf in E major (Detmold) (1840)•S.164e, Album-Leaf: Magyar (1841)•S.164f, Album-Leaf in A minor (Rákóczi-Marsch) (1841)•S.164g, Album-Leaf: Berlin Preludio (1842)•S.165, Feuille d'album (in A flat) (1841) 降A大调纪念册的一页•S.166, Albumblatt in waltz form (1841) A大调圆舞曲风格纪念册的一页•S.166a, Album Leaf in E major (1843)•S.166b, Album-Leaf in A flat (Portugal) (1844)•S.166c, Album-Leaf in A flat (1844)•S.166d, Album-Leaf: Lyon prélude (1844)•S.166e, Album-Leaf: Prélude omnitonique (1844)•S.166f, Album-Leaf: Braunschweig preludio (1844)•S.166g, Album-Leaf: Serenade (1840–49)•S.166h, Album-Leaf: Andante religioso (1846)•S.166k, Album Leaf in A major: Friska (ca. 1846-49)•S.166m-n, Albumblätter für Prinzessin Marie von Sayn-Wittgenstein (1847)•S.167, Feuille d'album No. 2 [Die Zelle in Nonnenwerth, third version] (1843) a小调纪念册的一页•S.167a, Ruhig [catalogue error; see Strauss/Tausig introduction and coda]•S.167b, Miniatur Lieder [score not accessible at present] (?)•S.167c, Album-Leaf (from the Agnus Dei of the Missa Solennis, S9) (1860–69)•S.167d, Album-Leaf (from the symphonic poem Orpheus, S98) (1860)•S.167e, Album-Leaf (from the symphonic poem Die Ideale, S106) (1861)•S.167f, Album Leaf in G major (ca. 1860)•S.168, Elégie sur des motifs du Prince Louis Ferdinand de Prusse [first/second version] (1842, 1851) 悲歌•S.168a, Andante amoroso (1847?)•S.169, Romance (O pourquoi donc) (1848) e小调浪漫曲•S.170, Ballade No. 1 in D flat (Le chant du croisé) (1845–48) 叙事曲一•S.170a, Ballade No. 2 [first draft] (1853)•S.171, Ballade No. 2 in B minor (1853) 叙事曲二•S.171a, Madrigal (Consolations) [first series, 6 pieces] (1844)•S.171b, Album Leaf or Consolation No. 1 (1870–79)•S.171c, Prière de l'enfant à son reveil [first version] (1840)•S.171d, Préludes et harmonies poétiques et religie (1845)•S.171e, Litanies de Marie [first version] (1846–47)•S.172, Consolations (Six penseés poétiques) (1849–50) 6首安慰曲•S.172a, Harmonies poétiques et religieuses [1847 cycle] (1847)•S.172a/3&4, Hymne du matin, Hymne de la nuit [formerly S173a] (1847)•S.173, Harmonies poétiques et religieuses [second version] (1845–52) 诗与宗教的和谐•S.174, Berceuse [first/second version] (1854, 1862) 摇篮曲•S.175, Deux légendes [2 pieces] (1862–63) 2首传奇•1. St. François d'Assise. La prédication aux oiseaux (Preaching to the Birds)•2. St. François de Paule marchant sur les flots (Walking on the Waves)•S.175a, Grand solo de concert [Grosses Konzertsolo, first version] (1850)•S.176, Grosses Konzertsolo [second version] (1849–50 ?) 独奏大协奏曲•S.177, Scherzo and March (1851) 谐谑曲与进行曲•S.178, Piano Sonata in B minor (1852–53) b小调钢琴奏鸣曲•S.179, Prelude after a theme from Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen by J. S. Bach (1859) 前奏曲“哭泣、哀悼、忧虑、恐惧”S.179 - 根据巴赫第12康塔塔主题而作•S.180, Variations on a theme from Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen by J. S. Bach (1862) 巴赫康塔塔主题变奏曲•S.181, Sarabande and Chaconne from Handel's opera Almira (1881)•S.182, Ave Maria - Die Glocken von Rom (1862) 圣母颂“罗马的钟声”•S.183, Alleluia et Ave Maria [2 pieces] (1862) 哈利路亚与圣母颂•S.184, Urbi et orbi. Bénédiction papale (1864)•S.185, Vexilla regis prodeunt (1864)•S.185a, Weihnachtsbaum [first version, 12 pieces] (1876)•S.186, Weihnachtsbaum [second version, 12 pieces] (1875–76) 钢琴曲集《圣诞树》•S.187, Sancta Dorothea (1877) 圣多萝西娅•S.187a, Resignazione [first/second version] (1877)•S.188, In festo transfigurationis Domini nostri Jesu Christi (1880) 我主耶稣基督之变形•S.189, Klavierstück No. 1 (1866)•S.189a, Klavierstück No. 2 (1845)•S.189b, Klavierstück (?)•S.190, Un portrait en musique de la Marquise de Blocqueville (1868)•S.191, Impromptu (1872) 升F大调即兴曲“夜曲”•S.192, Fünf Klavierstücke (for Baroness von Meyendorff) [5 pieces] (1865–79) 5首钢琴小品•S.193, Klavierstuck (in F sharp major) (a. 1860) 升F大调钢琴小品•S.194, Mosonyis Grabgeleit (Mosonyi gyázmenete) (1870) 在莫佐尼墓前•S.195, Dem andenken Petofis (Petofi Szellemenek) (1877) 纪念裴多菲•S.195a, Schlummerlied im Grabe [Elegie No 1, first version] (1874)•S.196, Élégie No. 1 (1874)•S.196a, Entwurf der Ramann-Elegie [Elegie No 2, first draft] (1877)•S.197, Élégie No. 2 (1877)•S.197a, Toccata (1879–81) 托卡塔•S.197b, National Hymne - Kaiser Wilhelm! (1876)•S.198, Wiegenlied (Chant du herceau) (1880) 摇篮曲•S.199, Nuages gris (Trübe Wolken) (1881) 灰色的云•S.199a, La lugubre gondola I (Der Trauergondol) [Vienna draft] (1882)•S.200, La lugubre gondola [2 pieces] (1882, 1885) 葬礼小船。

3B SCIENTIFIC ® FÍSICAInstrucciones de uso08/22 HJB1 Clavijeros de 4 mm para conexiónde la tensión de calefacción 2 Clavijeros de 2 mmpara la conexión del cátodo 3 Resistencia interna 4 Espiral de calefacción 5 Cátodo 6 Ánodo7 Pin de 4 mmpara conexión del ánodo 8 Electrodo de focalización 9 Rejilla de grafito policristalino 10 Soporte11 Pantalla fluorescenteLos tubos catódicos incandescentes son ampo-llas de vidrio, al vacío y de paredes finas. Mani-pular con cuidado: ¡riesgo de implosión!∙ No someter los tubos a ningún tipo de esfuer-zos físicos.∙ El tubo se debe insertar únicamente en el so-porte para tubos D (1008507).∙No someter a tracción el cables de conexión.Las tensiones excesivamente altas y las corrien-tes o temperaturas de cátodo erróneas pueden conducir a la destrucción de los tubos.∙ Respetar los parámetros operacionales indicados. ∙Solamente efectuar las conexiones de los cir-cuitos con los dispositivos de alimentación eléctrica desconectados.∙Los tubos solo se pueden montar o desmon-tar con los dispositivos de alimentación eléc-trica desconectados.Durante el funcionamiento, el cuello del tubo se calienta.∙De ser necesario, permita que los tubos se enfríen antes de desmontarlos.El cumplimiento con las directrices referentes a la conformidad electromagnéticade la UE se puede garantizar sólo con las fuentes de alimen-tación recomendadas.Este tubo de difracción sirve para la comprobación de la naturaleza ondulatoria de los electrones, a tra-vés de la observación de las interferencias que se originan después de su paso por una rejilla policris-talina de grafito (difracción de Debye-Scherrer), una vez que se vuelven visibles en la pantalla fluores-cente; sirve también para la determinación de la lon-gitud de onda de los electrones, con diferentes ten-siones anódicas, a partir de los radios de los anillos de difracción y de las distancias entre las capas de la red de grafito, y para la comprobación de la hipó-tesis de de Broglie.El tubo de difracción de electrones es un tubo de alto vacío, con un filamento incandescente (4) de tungsteno puro y un ánodo cilíndrico (7) dentro de una ampolla de vidrio transparente y al vacío. A par-tir de los electrones emitidos por el cátodo incan-descente, se corta un delgado haz de rayos, por medio del orificio de un diafragma, y se enfoca a través de un sistema óptico de electrones.REste haz, nítidamente limitado y monocromático, atraviesa una red fina de filamentos de níquel, que se encuentra en la "desembocadura" del cañón de electrones (8), que está cubierto de una película de grafito policristalino y que actúa como rejilla de di-fracción. Sobre la pantalla fluorescente (10) se vi-sualiza la imagen de difracción en forma de dos ani-llos concéntricos, presentes alrededor del haz de electrones difractado.Un imán forma parte del volumen de suministro. Éste permite alterar la dirección del haz de elec-trones, lo cual es necesario cuando surge un punto defectuoso en la red de grafito, sea por de-fecto de fábrica o por la quemadura del mismo.Calentamiento: ≤ 7,0 V AC/DC Tensión anódica: 0 – 5000 V DC Corriente anódica: tipo 0,15 mAa 4000 V DCConstantesde la red de grafito: d10 = 0,213 nm d11 = 0,123 nmDimensiones:Distancia rejilla de grafito /Pantalla fluorescente: aprox. 125 ± 2 mm Pantalla fluorescente: aprox. 100 mm Ø Ampolla de vidrio: aprox. 130 mm Ø Longitud total: aprox. 260 mmIncluido en la entrega:1 adaptador de2 mm con toma de 4 mm; es ne-cesario si no se utiliza el adaptador de protección de3 polos (1009960) para conectar el cátodo a la toma de 2 mm [(2) en el diagrama]. La cone-xión a la fuente de alimentación de alta tensión se realiza de este modo a través de un cable ex-perimental de seguridad.Se requiere adicionalmente:Para la operación del tubo de difracción de elec-trones se necesita el siguiente equipo suplemen-tario:1 Soporte de tubos D 1008507 1 Fuente de alta tensión 5 kV:(115 V, 50/60 Hz) 1003309o(230 V, 50/60 Hz) 1003310 2 Par de cables de experimentación, 75 cm 1002850 1 Cable de experimentación, clavija/casquillo1002838 Se recomienda adicionalmente:1 Adaptador de protección, de 3 polos 10099602 Par de cables de experimentación de seguri-dad, 75 cm 1002849 1 Cable de experimentación, clavija de seguri-dad/casquillo 1002839 4.1 Instalación del tubo en el soporte para tubo ∙Montar y desmontar el tubo solamente con los dispositivos de alimentación eléctrica desconectados.∙Retirar hasta el tope el desplazador de fija-ción del soporte del tubo.∙Colocar el tubo en las pinzas de fijación.∙Fijar el tubo en las pinzas por medio del des-plazador de fijación.∙Dado el caso, se inserta el adaptador de protec-ción en el casquillo de conexión del tubo.4.2 Desmontaje del tubo del soporte para tubo∙Para retirar el tubo, volver a retirar el despla-zador de fijación y extraer el tubo.4.3 Indicaciones generalesLa película de grafito de la rejilla de difracción sólo tiene algunas capas moleculares de espesor y, por tanto, se puede destruir ante una corriente mayor a 0,2 mA.La resistencia interna sirve para la limitación de la corriente y, por tanto, para evitar daños en la película de grafito.Durante la experimentación, se debe controlar la pelí-cula de grafito. En caso de que se queme la rejilla de grafito, se debe desconectar inmediatamente la ten-sión anódica.En el caso de que los anillos de difracción no se vean claramente, se puede modificar la dirección del haz de electrones por medio de un imán, de modo que se proyecte sobre alguna otra área de la película de grafito.∙Monte el experimento de acuerdo con la fig. 2.El polo negativo de tensión anódica se conecta siempre a través de los conectores de 2 mm. ∙Conectar la tensión de calentamiento y esperar aproximadamente 1 minuto hasta que la res-puesta de calentamiento sea estable.∙Aplicar una tensión anódica de 4 kV.∙Determinar el diámetro D de los anillos de di-fracción sobre la pantalla luminosa.Ahora son visibles dos anillos de difracción en-vueltos por el haz de electrones difractado. Cada uno de los anillos corresponde a una reflexión de Bragg en los átomos de un nivel de la red de gra-fito.Las modificaciones de la tensión anódica provo-can cambios en los diámetros de los anillos de difracción, por lo que una reducción de la tensión provoca un aumento del diámetro. Esta observa-ción coincide con el postulado de de Broglie, se-gún el cual, la longitud de onda se expande con la disminución del impulso.a) Ecuación de Bragg: ϑ⋅⋅=λsin2dλ = Longitud de onda de los electronesϑ = Ángulo de brillo del anillo de difracciónd = Distancia entre las capas de red en la rejilla de gra-fitoL = Distancia entre el objeto de prueba y la pantalla lu-minosaD = Diámetro de los anillos de difracciónR = Radio de los anillos de difracciónLD⋅=ϑ22tanLRd⋅=λb) Ecuación de de Broglie:ph=λh = Quantum de Planckp = Impulso de los electronesmpUe⋅=⋅22Uemh⋅⋅⋅=λ2m = Masa del electrón, e = Carga elementalFig. 1 Representación esquemática de la difracción de Debye-ScherrerFig. 2 Circuito del tubo de difracción de electrones DFig. 3 Circuito del tubo de difracción de electrones D con adaptador de protección, de 3 polos (1009960) 3B Scientific GmbH ▪ Ludwig-Erhard-Str. 20 ▪ 20459 Hamburgo ▪ Alemania▪ 。

九年级英语摄影主题分析练习题30题1. I have a new _____. It can take beautiful pictures.A.cameraB.paintingC.bookD.pen答案:A。

本题考查摄影器材相关词汇。

A 选项“camera”是“相机”的意思;B 选项“painting”是“绘画”;C 选项“book”是“书”;D 选项“pen”是“钢笔”。

根据题干中“take beautiful pictures(拍漂亮的照片)”可知是相机,所以选A。

2. The _____ is used to take pictures in the dark.A.flashB.sunC.moonD.star答案:A。

A 选项“flash”是“闪光灯”,可以在黑暗中拍照时使用;B 选项“sun”是“太阳”;C 选项“moon”是“月亮”;D 选项“star”是“星星”。

所以选A。

3. My father bought me a _____ as a birthday present.A.telescopeB.camera lensC.microscopeD.binoculars答案:B。

本题考查摄影器材相关词汇。

A 选项“telescope”是“望远镜”;B 选项“camera lens”是“相机镜头”;C 选项“microscope”是“显微镜”;D 选项“binoculars”是“双筒望远镜”。

根据题干中“as a birthday present( 作为生日礼物)”且结合摄影主题,可知是相机镜头,所以选B。

4. The _____ of this camera is very good.A.colorB.sizeC.qualityD.price答案:C。

本题考查词汇用法。

A 选项“color”是“颜色”;B 选项“size”是“尺寸”;C 选项“quality”是“质量”;D 选项“price”是“价格”。

Chapter12Leontief ParadoxThere exist two possible methods for the investigation,the inductive inference and deductive inference.The inductive inference collects empirical observations and infers the general conclusion from them.Although it is very useful for the practical purposes,the inductive inference cannot arrive to the definite conclusion. You observe as many white swans as you like in the northern hemisphere,but cannot conclude that swan is white,since you cannot exclude the possibility to see black swans in the southern hemisphere.You can collect all the cases in the past,but cannot conclude definitely,since you cannot know the possible cases in the future. To arrive at the definite conclusion,therefore,we have to rely on the deductive inference.It starts with some assumptions and derive logical conclusions from them.Some assumptions may be derived from inductive inference founded on the empirical observations while other assumptions are made merely as the simplifying assumptions.As far as the assumptions are admitted,and the logical operations are correct,the derived conclusion must be accepted.Since there is no assurance that assumptions are empirically true,however,the conclusion of the deductive inference cannot be assured to be empirically right. Such a conclusion must be subject to the empirical tests,since to test the empirical validity of assumptions themselves is,in general,more difficult.If the conclusion is empirically refuted,something must be wrong with respect to assumptions.We have to discard at least some of them and replace them by new assumptions.With the new set of assumptions,then,the deductive inference and the empirical test of its conclusion must be repeated.If the conclusion is not refuted,however,it does not imply that it is empirically true.It merely means that it is not refuted temporarily,since we cannot exclude the possibility that it will be refuted by some other empirical tests in the future.When carefully planned experiments are possible,as in the case of some natural sciences,it is easy to refute empirically the conclusion of the deductive inferences.When it is not,as in the case of social sciences,the empirical test must rely on the observation of empirical data which we cannot control and it is very difficult to see whether the data given is relevant and appropriate for the refutation of the conclusion.87 T.Negishi,Developments of International Trade Theory,Advances in Japanese Businessand Economics2,DOI10.1007/978-4-431-54433-3__12,©Springer Japan2014Our Heckscher–Ohlin theorem,discussed in Chap.10,is a typical example of the conclusion of the deductive inference logically derived from assumptions.From the assumptions on the production functions,consumer taste,the endowments of factors of production,etc.,the theorem is derived logically that a country exports those commodities which use intensively such factors of productions that are endowed abundantly,and imports those commodities which use intensively such factors of production that are endowed scarcely.It was Leontief(1954)who tried to check this theorem empirically.Leontief(1954)considered a Heckscher–Ohlin international trade model of two countries,the USA and the rest of the world.Two commodities considered are a composite commodity“US exports”and another composite commodity“US competitive import replacements.”Competitive import is defined as the import of commodities which can be and are,at least in part,actually produced by domestic industries.In other words,two domestic industries are the export industry and the import competing industry.The question to be studied is,then,whether it is true that the United States exports commodities the domestic production of which absorbs relatively large amounts of capital and little labor and imports foreign goods which, if produced at home,would employ a great quantity of indigenous labor but a small amount of domestic capital.By applying his famous input–output analysis to the 1947input–output table of the US economy,Leontief computed the total(direct and indirect)input requirements of capital and labor per unit of two composite commodities.The result is that the capital–labor ratio is approximately14for US Exports and18for US Import replacements.In other words,USA exports labor-intensive commodities and imports capital-intensive commodities.This is called Leontief paradox,since USA was considered generally to be a capital abundant country relative to the rest of the world.Heckscher–Ohlin theorem seems to be empirically refuted.One might wonder,of course,whether Leontief’s result was relevant or appropriate to the empirical test of Heckscher–Ohlin theorem.As a matter of fact, Leontief himself was thefirst who wondered.If the labor is measured by using the man-years units and the capital,by dollars in1947prices,as was done in his study,certainly USA is a relatively capital abundant country.Since labor is more efficient in USA than in the rest of the world,however,USA should be considered as a labor abundant country,if the labor is measured by using the efficiency units.“[W]ith a given quantity of capital,one man-year of American labor is equivalent to,say,three man-years of foreign labor.Then,in comparing the relative amount of capital and labor possessed by the United States and the rest of the world—the total number of American workers must be multiplied by three—.Spread thrice as thinly as the unadjustedfigures suggest,the American capital supply per“equivalent worker”turns out to be comparatively smaller,rather than larger,than that of many other countries.”Leontief’s empirical data,then,does not refute Heckscher–Ohlin theorem.Another possibility is that the choice of labor and capital as two factors of production,as was done by Leontief,might not be appropriate for the case of trade between USA and the rest of the world.In view of the fact,for example,that US oil-fields are less rich than those in Venezuela or in the Arabian countries, it is important to consider natural resources as factors of production.Then,the United States might import goods intensive in natural resources,which is the relatively less abundant factors there,and export goods intensive in capital and labor relative to natural resources.If so,again,Leontief’s empirical data does not refute Heckscher–Ohlin theorem.For the details of literature which insists on this possibility,see Gandolfo(1994,p.96).If one accept Leontief’s empirical result as the refutation of Heckscher–Ohlin theorem,on the other hand,some of assumptions of the theorem must be rejected. Among the assumptions of Heckscher–Ohlin theorem,one of the assumptions which can be most easily doubted is that of the identical consumption pattern between different countries.This may be particularly so in the case of Leontief paradox since the per-capita income level is much different between USA and the rest of the world.Suppose,relatively speaking,USA is abundantly endowed with capital and labor,scarcely.If Heckscher–Ohlin theorem is right as far as the pattern of incomplete specializations is concerned,USA is specialized in the production of those commodities which are relatively capital intensive,though the specialization is incomplete.Suppose,however,the domestic consumption pattern in USA is biased to capital intensive commodities.Even though the domestic supply of such capital intensive commodities is large,the domestic demand for them may be still larger. Then,the domestic excess demand for such capital intensive commodities should be supplied by the imports from the rest of the world,a country where capital is, relatively speaking,scarcely endowed.Since the information on technology is mobile internationally,we may assume the identical production functions between different countries.As people are not freely mobile between countries,however,we may not assume the identical level of income,which include not only wage income but also that from capital,1so that the consumption pattern can be different in different countries.It is well known that the ratio of the food consumption in the total expenditure is less for the high income families than for the low income ones(Engel’s law).Can we suppose high income USA families prefer the capital intensive commodities rather than the labor intensive commodities?Unfortunately,this is not certain.High income families may prefer such labor intensive commodities as expensive homemade goods like homespun cloth rather than to such capital intensive commodities as machine-made cheap goods produced in large-scale production factories.Another assumption of Heckscher–Ohlin theorem,which may be doubted,is that of no factor intensity reversal.It is assumed in the theorem that the commodity1, for example,is always more capital intensive(capital–labor ratio is higher)than the commodity2for any value of the wage–rental ratio,i.e.,k1>k2for any given w/r.Suppose,however,that the commodity1is more capital intensive than1If capital is abundantly endowed relative to labor,in comparison with the rest of the world,per-capita income level is higher in such a country than in the rest of the world,since per-capita income from capital is larger.Fig.12.1Factor intensityreversal Fig.12.2Wage–rental rationot equalizedthe commodity 2when the wage–rental ratio is high,w /r >(w /r )1;but is less capital intensive when the wage–rental ratio is low,w /r <(w /r )1,as is shown in Fig.12.1.Then in Fig.12.2,we cannot have the unique solution of w /r for the given value of p ,i.e.,the price of the second commodity in terms of the first.For the same p in the international market,it is possible that w /r for the country 1is Oa while it is Ob for the second country.The commodity 1is less capital intensive (k 1<k 2)in the first country while it is more capital intensive (k 1>k 2)in the second country.Then,Heckscher–Ohlin theorem cannot be valid generally,since the exportables have the same kind of factor intensity in both countries.It remains valid for one country only.The case like Fig.12.1occurs if the production functions are of CES (constant elasticity of substitution)type,Y =[aL −b +(1−a )K −b ]−1/b (0<a <1,b >−1)(12.1)Bibliography91 where Y,L,and K denote,respectively,the output,the labor input,and the capital input,while a and b are given constants.2Using production functions of this type, Minhas(1962)found that factor intensity reversals were quite frequent in the real world.This suggests that,theoretically speaking,Leontief paradox is very likely to occur.What is most important with respect to Leontief paradox is,however,that the presence of the paradox could be by no means systematically confirmed by the subsequent studies carried out with respect to both USA and other countries.How, then,should we interpret the significance of this almost single empirical evidence against Heckscher–Ohlin theorem?It depends on the nature of the theorem.If it is the exact theorem which insists that each country always exports the commodity which uses her more abundant factor more intensively,it should be refuted by a single empirical evidence against it.In view of the long-run and the aggregate nature of Heckscher–Ohlin two-country two-commodity two-factor model,however,we should rather interpret the theorem that most of the countries generally export the commodities which use,on the average,their abundantly endowed factors more intensively.Then,we have to retain such a theorem on the long-run average tendency,unless it is repeatedly and systematically refuted empirically.This is the reason why,in spite of Leontief’s paradox,Heckscher–Ohlin theorem is still in the textbooks of international trade theory as one of the basic theorems.12.1Problems12.1.Demonstrate that there is no factor intensity reversal if the production functions are of Cobb–Douglas type.12.2. a.Demonstrate that w/r=[a/(1−a)]k b+1,where w/r is the wage–rentalratio and k is the capital–labor ratio,if the production function is of the constant elasticity of substitution type,i.e.,(12.1).Consider the elasticity of k with respect to(w/r)and show it is constant.b.Explain,then,that we have a case of Fig.12.1,if two commodities havethe identical production function,i.e.,the constant elasticity of substitution production function but with different values of b.BibliographyGandolfo,G.(1994).International economics,I.Berlin:Springer.Kemp,M.C.(1964).The pure theory of international trade.Englewood Cliff,NJ:Prentice Hall. 2For the constant elasticity of substitution production functions,see Kemp(1964,pp.22and57). See also Problem12.2.9212Leontief Paradox Leontief,W.(1954).Domestic production and foreign trade;the American capital position re-examined.Economia Internazionale,7,3–32.Minhas,B.S.(1962).The homohypallagic production functions,factor intensity reversals,and the Heckscher–Ohlin Theorem.Journal of Political Economy,70,140–168.。

第二章劳动生产率与比较优势李嘉图模型▪各国参与国际贸易的基本原因有两个:•首先,它们在气候、土地、资本、劳动力和技术等方面存在着千差万别。

•其次,它们试图通过贸易来达到规模经济。

▪李嘉图模型以国家间的技术差别为研究基础:•这些技术差别反映在劳动生产率上。

第二节单一要素经济▪假定存在一个经济社会(我们称之为本国),在这个经济社会中:•劳动是唯一的生产要素。

•只生产两种产品(葡萄酒和奶酪)。

•劳动的供给是既定的。

•每种产品的劳动生产率是既定的。

•所有的市场都是完全竞争的。

▪各个产业的劳动生产率表明了本国的技术水平,为简便起见,我们用单位产品劳动投入来表示劳动生产率。

•单位产品劳动投入指一单位产出所需要的劳动时间。

▪aLW表示生产一加仑葡萄酒的单位产品劳动投入。

▪aLC表示生产一磅奶酪的单位产品劳动投入。

▪L为本国的全部资源,即劳动供给。

一、生产可能性边界二、相对价格与供给▪在单一要素模型中,产品的供给是由相对价格与机会成本共同决定的。

▪PC-为奶酪的价格,PW-为葡萄酒的价格。

▪以葡萄酒衡量的奶酪的相对价格为PC/PW。

单一要素模型中不存在利润,因此每小时工资率等于一个工人在1小时内创造的价值。

第三节单一要素世界中的贸易▪模型假设:•在世界上有两个国家:本国和外国•每个国家生产两种产品:葡萄酒和奶酪•劳动是唯一的生产要素•在每个国家劳动的供给是既定的(L,L*)•每种产品的劳动生产率是固定的•劳动在两个国家之间不可流动•市场为完全竞争的•用*来表示外国的变量一、绝对优势和比较优势1、绝对优势Absolute Advantage•当一个国家能够以少于其他国家的劳动投入生产出同样单位的商品时,那么该国在生产这种商品上具有绝对优势。

•假设–这意味着本国在两种产品的生产上均具有绝对优势。

也就是说和外国相比,本国在两种产品的生产上效率更高。

–即使本国在两种产品上均具有绝对优势,互惠贸易也是由可能发生的。

贸易模式是由比较优势决定的。

波希米亚人歌剧曲目介绍大全波西米亚人(La bohème)是一部由意大利作曲家普契尼(Giacomo Puccini)创作的歌剧,首演于1896年。

它以浪漫主义风格描绘了一群年轻艺术家在19世纪末巴黎的生活,以及他们之间的友谊、爱情和悲剧。

以下是《波希米亚人》中的曲目介绍:第一幕:1. 序曲(Prelude)。

2. "Questo Mar Rosso"(马尔切洛的独唱)。

3. "Che Gelida Manina"(罗德尔福的独唱)。

4. "Sì. Mi Chiamano Mimì"(米米的独唱)。

5. "O Soave Fanciulla"(罗德尔福和米米的二重唱)。

第二幕:1. "Aranci, datteri!"(巴尔托洛梅奥的独唱)。

2. "Quando m'en vo"(穆齐塔的独唱)。

3. "Chi l'ha richiesto?"(巴尔托洛梅奥和穆齐塔的二重唱)。

4. "Viva Parpignol!"(合唱)。

第三幕:1. "Ohè là, le guardie!"(巴尔托洛梅奥的独唱)。

2. "Mimì è una civetta"(巴尔托洛梅奥和罗德尔福的二重唱)。

3. "Mimì è tanto malata!"(米米和罗德尔福的二重唱)。

4. "Dunque è proprio finita!"(巴尔托洛梅奥、罗德尔福和米米的三重唱)。

5. "Addio... Donde lieta uscì"(米米的独唱)。