雅思精讲阅读班精讲班第9讲讲义

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:127.14 KB

- 文档页数:5

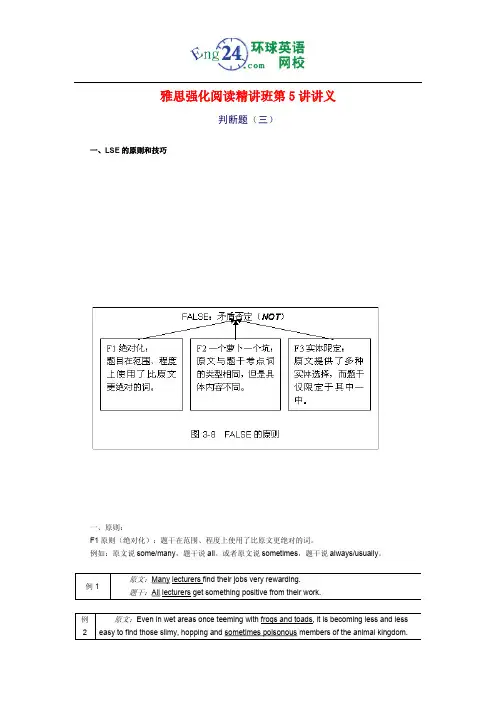

雅思强化阅读精讲班第5讲讲义判断题(三)一、LSE的原则和技巧一、原则:F1原则(绝对化):题干在范围、程度上使用了比原文更绝对的词。

例如:原文说some/many,题干说all。

或者原文说sometimes,题干说always/usually。

例1 原文:Many lecturers find their jobs very rewarding.题干:All lecturers get something positive from their work.例2原文:Even in wet areas once teeming with frogs and toads, it is becoming less and less easy to find those slimy, hopping and sometimes poisonous members of the animal kingdom.另外,请参见《剑桥6》移民类第一套阅读第五题F2原则(一个萝卜一个坑):原文与题干考点词的类型相同,但是具体内容不同。

例题:F2原则的例题包括:《剑桥3》:T2P1Q2,T3P1Q1/Q2,T3P2Q16,T4P2Q22/Q23《剑桥4》:T1P1Q5《剑桥5》:T2P3Q36,T3P2Q20F3原则(实体限定):原文提供了多种实体选择,而题干仅限定于其中一中。

例如:原文说A and/or B ,题干说only A 。

A and B 相当于NOT only A ,所以存在矛盾,选FALSE 。

例题:F3原则的例题:《剑桥4》T3P1Q11二、技巧:FS1技巧(S代表skill):含有绝对范围、程度考点词的题目大多数选FALSE/NO。

English for Study in Australia留学澳洲英语讲座Lesson 9: In the classroom第九课:在课堂上L1 Male 各位听众朋友好,欢迎您收听留学澳洲英语讲座节目,我是澳大利亚澳洲广播电台中文部的节目主持人陈昊。

L1 Female 各位朋友好,我是马健媛。

L1 Male 这套系列教材由澳大利亚成人多元文化教育服务机构为您编写,澳洲广播电台编播制作。

L1 Female 在这套课程里我们要跟随四名刚刚抵达澳大利亚墨尔本市的四名留学生一起来学习澳洲文化的方方面面以及在澳洲学校中的生活L1 Female 今天我们要学习第九课,在课堂上。

在这一课中我们要学习有关澳洲学校课堂上的一些情况以及考试中可能会遇到的一些问题。

另外,我们还要学习一些在课堂上向同学们做自我介绍时会用到的一些句型。

当然,如何向老师提问也是我们这一课学习的重点。

L1 Male: 好,我们现在就开始上课吧。

首先让我们一起来听一段对话的录音。

在这段对话中,罗基、凯蒂和安吉尔第一次到英语强化培训学校上课,他们的老师就是在学校开放日对罗基进行面试的马里奥老师。

Marion:OK. Let’s move on. If you’ll all look at the board, this is the timetable for Module A. As you can see, you’ll spend 4 hours a day in formal classes and one hour in independent study in thelibrary. You’ll also be expected to do at least one hour of homework per night, working on dailyassignments and research towards your assessment tasks. Are there any questions? Yes.Angel?L1:好,我们现在开始上课。

新航道雅思阅读强化精讲(李楠老师)雅思阅读强化精讲——Short Answer Questions (简答题)----- Crystal Lee1.题型要求每个题目都是一个特殊问句,要求根据原文作出回答。

绝大部分的题目要求有字数限制,一般有如下几种表达方式:(1)NO MORE THAN TWO/THREE/FOUR WORDS (不超过2/3/4 个字);(1)ONE OR TWO WORDS (一个或两个字);(1)Use a maximum of TWO words (最多两个字)。

注意:有字数限制的,一定要严格按照题目要求去做。

少部分的题目要求中没有字数限制,这时,请注意,答案字数也不会很长,一般不会超过四个字。

总之,这种题型的答案都是词或短语,很少是句子,所以又叫“短问答”。

该题型一般为细节题(得分必拿题)。

是雅思阅读中难度较低的一种题型。

所以一定要保证此题型的准确率。

考试中,A类和G类一般都是每次必考,考一组,共三题左右。

2.解题步骤(1)定位。

找出题目中的关键词,最好先定位到原文中的一个段落。

将题目中的关键词与原文各段落的小标题或每段话的第一句相对照。

有些题目能先定位到原文中的一个段落,这必将大大加快解题时间,并提高准确率。

但并不是每个题目都能先定位到原文中的一个段落的。

题目中如果包含专有名词(年代、人名、地名、数字),这些词肯定是关键词,因为原文中不会对这些词做改变,而且这些词特别好找,所以依据这些词在原文中确定答案比较快。

(2)选读。

从头到尾快速阅读该段落,根据题目中的其他关键词,确定正确答案。

确定一个段落后,答案在该段落中的具体位置是未知的。

所以,需要从头到尾快速阅读该段落,确定正确答案。

新航道雅思阅读强化精讲(李楠老师)(3)作答。

答案要对应题目中的特殊疑问词。

答案必须要对应题目中的特殊疑问词。

绝大部分的答案是名词或名词短语,也有少部分是动词或形容词短语。

特殊疑问词:what ,who ,when, where 答案词性:名词(时间,地点,人或单位等)答案例子:8:00am, classroom, calcium deposit, Australian taxpayer 注意事项:不需要时间名词前面的介词及冠词,钟点后面要有am 或pm 。

主持⼈:各位友⼤家好,今天来到嘉宾聊天室的是北京新航道学校的王毅⽼师。

王毅⽼师在3⽉31⽇参加了武汉的雅思考试获得了单项听⼒9分,阅读9分,⼝语9分,写作8分,雅思总分9分。

在以下的时间⾥,他将与各位友交流有关雅思学习的问题。

先请王⽼师和⼤家打个招呼。

王毅:各位同学⼤家好。

友:你好,王⽼师,我的听⼒和阅读⽐较差,具体说阅读的summary的不知道填什么好,虽然知道在那⼀段,听⼒是阅读题⽬还没有看完,听⼒已经开始,⼿忙脚乱的。

王毅:先说说阅读的summary题,该体型是雅思阅读两⼤主要体型(细节题和归纳概括总结题)中的细节题。

⼀般来说,在难度系数为10的标准下,他的难度系数⼀般为6-8。

算是中等难度的题⽬。

当然针对你的问题--不知道填什么词回来好--解决的⽅法⼀般有以下⼏种:1。

对题⽬和原⽂的逻辑关系进⾏⽐较,把同等级逻辑元素天回来就是正确答案。

2。

运⽤最近原则。

简单的来讲就是分析空格最近意思层的信息回到原⽂当中寻找。

3。

在根本就不会做的情况下可以运⽤⼀些蒙题的技巧,例如:把所对应原⽂信息中最专业最长的词汇填回来就有可能是正确答案(当然,这样的正确率并不⾼)。

再来说说听⼒,以你的情况要多做快速阅读的训练。

其中之⼀,在读的时候不要在⼼⾥把每个词念出来,要练习扫描句⼦并掌握其主要意思的能⼒。

同时还要辅助地加以泛听训练。

友:王⽼师,请问雅思⽬前所要求的词汇量为多少? 从2007年到2009年雅思词汇量和难度是否还要调整,它将如何调整?王毅:⾸先,雅思的听说读写词汇侧重各有不同。

学术类的阅读和写作所要求的词汇侧重于学术,培训类的阅读和写作的词汇侧重于⽣存词汇。

对于这两者的听⼒和⼝语来说,所要求的词汇基本上也都以⽣存类为主,当然也有少量学术词汇的覆盖。

但是总体上来说,雅思达到6分所要达到的词汇量⼀般被认为是6000词汇。

当然要想考到⾼分,丰富的词汇是必备的。

就我个⼈⽽⾔,我考过GRE,词汇量在2-3万之间,所以雅思考起来就⽐较轻松。

雅思考试阅读9分秘诀雅思考试阅读9分秘诀雅思阅读如何拿到9分?和店铺一起来看看这个秘籍吧!以下是店铺为大家搜索整理的雅思考试阅读9分秘诀,希望能给大家带来帮助!一、何为“顺序原则”“顺序原则”即雅思官方在题型特点注释中所述的“Answers are in passage order.”说的复杂一些,便是:若某一题型符合“Answers are in passage order”的描述,该题型所包含的几个题目的答案在文中分布的相应位置随题号的变大而逐渐靠后。

Sounds like a mouthful, right? 简而言之吧,就是这种题型考生可以顺着题号一题一题地往文章更靠后的位置找,比较符合正常人的阅读习惯(相信很少有人上来先读一篇文章的第三段,或者第四段吧)。

二、顺序原则与题型宏观地看一篇文章包涵的全部题型,答案分布的顺序也符合题型出现的先后顺序,例如全文包含先判断题,后填空题这两种题型,则较有可能出现的情况是判断题答案分布在文章的前半部分,而填空题在文章后半部分。

例如: 剑桥雅思真题集系列7,T est 4 Passage 1:前7题判断题分布于前6个段落,剩下的段落填空题分布于第9段,和前面7段无关。

接下来说说哪些题型符合“Answers are in passage order”。

我们把题型总体分成四大类- 判断、选择、填空和配对。

判断题,包括identifying information(TRUE/FALSE/NOT GIVEN)和identifyingwriter’s views(YES/NO/NOT GIVEN)均严格地符合“顺序原则”。

选择题,分为单选题和多选题。

四选一的单选题,即multiple choice questions(choose one from A/B/C/D)符合顺序原则,而多选题,即pickingfrom a list(pick 2 out of 5, 3 out of 6, 5 out of 11, etc)则无所谓顺序原则,所选答案在list中的位置可能与它们在文章中出现的先后顺序不吻合,但是这种题型在答题卷上以任何顺序写出所选答案都可以。

BEC高级精讲班第9讲讲义Home work reviewHomework 1A proposal on improvement of company’s websiteIntroductionWith E-business expanding rapidly, company websites become more and more important. However, our company’s website does not show us to the best advantage. We need to improve it.Situations of our current websiteGenerally speaking, most aspects of our current website are successful as follows:n Our current website is designed beautifully and eye-catching.n All products of our company have been listed on the website and can be dealt with through our website.n The introduction of our company is written perfectly, which can make our customers well realize our corporate history and culture.However, there are also some weaknesses involved in our website.n The specifications and functions of our products are not elaborated sufficiently.n The layout of our website is something messed, which inconveniences our customers finding their intended products.n There is no room for our customers to discuss our products and give feedback to us.New services and informationSome new services and information should be provided so as to strengthen our website. For example,n A search engine will be added to the website.n All products will be given detailed and attractive descriptions.n A new unit, a forum, will be created to facilitate our customers to give comments on our products and contact us.BenefitsWith the above improvements, the customers can find needed products conveniently and quickly. Moreover, they can acquire details of all products and place orders duly. In addition, we can realize the customers’ requirements and improve our products timely and efficiently to maintain and develop our market shares.ConclusionsA perfect website can help us obtain unexpected success, such as reducing our cost and attracting more customers. More importantly, we can get the support from our customers. Therefore, improvements are necessary.RecommendationsWe had better cooperate with experts in website to improve ours. At the same time, each department should participate and collaborate actively. Furthermore, the language used on thewebsite should be concise and exact.Li QingrongManagement DepartmentHomework 2Proposal on Improvement of the websiteIntroductionThis proposal aims to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the current website and recommend an improvement plan and elaborate the benefits it will bring.Existing websiteAs a renowned multinational, our company has a beautiful website with a great deal of graphs and pictures. The framework of the website is reasonably designed and it includes almost all necessary aspects.By contrast, the content of the site is not that satisfactory at all. There is only a brief introduction of our company on it without any updated information. Besides, the security of the website also deserves improvement.Improvements to be madeIt has been proved that websites with abundant information and services get more page hits than those which are appearance-oriented. Consequently, the content of the website should be enriched via adding latest news or stories of our company.The security system of the website also needs optimizing so that it can operate normally when suffering virus attack.BenefitsAfter increasing the content of our website, our customers can know more about the company and keep abreast with the latest events. That will definitely enhance their loyalty to our company and will enlarge our customer base at the same time.A more secure system can ensure the safety of the database of the server and also prevent hostile hacking efficiently.ConclusionOur existing website has some defects and need improvement urgently. Appropriate improvements will bring considerable benefits to our company.RecommendationIt is strongly recommended that the content of the website be increased and the security system be optimized.Homework 3Report on improving our websiteThe proposal aims to raise some issues about our website and provide some recommendations to improve it.SituationsThe website of our company was set up in 2000. It has been running for five years. The website showed how our company runs, our mission statement and our structure, to name but a few. It also has a BBS and manager box which improve communications between staff and top leaders effectively. But the homepage of the website needs updating and cannot reflect our company’s status quo and the development we are making.More informationIn response to the expansion of our company, adding some new information is necessary, such as adding updated news, setting up new database centre, renewal of the web into a more customer-friendly way. A self-service system for customers is also a good idea to improve our customer relationships. The new website should be a centre of company information, and every employee can hear the voice from top leaders through the web. It must be a learning centre from which staff can download the newest technologies and skills to learn. Since our products enter Spain and Japan markets and sales rose dramatically, the Spanish and Japanese versions are also needed.ConclusionsThe improvement of our website will give both company and staff stronger backup, and raise the productivity. The multi-language versions website will be more effective for our imagination and provide stronger after-sales service for our foreign markets.RecommendationsIt is suggested that the website should be rebuilt as soon as possible. We should hire a professional team to achieve the end.其他观点online service, mailbox for complaintsu 请听一段报纸介绍德国汽车厂商如何通过建立儿童网站获取客户源的报道2.Report On Changes in the sales of product in Japan, Indonesia and France during the period June 1994 to January 1997In June 1994, Japanese sales were $20,000. They fell sharply for twelve months to no sales at all in June 1995, when a new marketing strategy was introduced. Sales rocketed to $90,000 by late 1996.Indonesian sales, in June 1994, were $50,000, and rose steadily to $70,000 in June 1995. Sales dropped slightly to $60,000 in early 1996, but rose again almost to $70,000 by June 1995. Sales dropped slightly to $60,000 in early 1996, but rose once more to $70,000 in January 1997.In June 1994, sales in France were $50,000, but they plunged to $10,000 in January 1996, and varied slightly around $10,000 to January 1997.The new marketing strategy introduced in June 1995 apparently worked well only in Japan.V ocabularystudyII. V ocabulary Study(1) learning words --- 缺少lack noun [singular, uncountable] when there is not enough of something, or none of itᅳsynonym shortagelack ofnew parents suffering from lack of sleepToo many teachers are treated with a lack of respect.comments based on a total lack of informationDoes their apparent lack of progress mean they are not doing their job properly?tours that are cancelled for lack of bookingsThere was no lack of willing helpers.lack verb1 [transitive] to not have something that you need, or not have enough of itAlex's real problem is that he lacks confidence.lacking adjective [not before noun]1 not having enough of something or any of itlacking inHe was lacking in confidence.She seems to be entirely lacking in intelligence.The new designs have all been found lacking in some important way.2 if something that you need or want is lacking, it does not existFinancial backing for the project is still lacking.These qualities are sadly lacking today.Whatmotivesstaff?III. What motivates staff?motivate verb [transitive]1 to be the reason why someone does something促使, 驱使ᅳ同义词driveWould you say that he was motivated solely by a desire for power? 你的意思是说他完全只被追逐权利的愿望驱使着吗?motivate somebody to do somethingWe may never know what motivated him to kill his wife. 是什么驱使他杀了他的妻子, 我们对此不得而知.2 to make someone want to achieve something and make them willing to work hard in order to do this 激励A good teacher has to be able to motivate her students. 一个好教师应该是有能力激励她的学生. motivate somebody to do somethingThe profit-sharing plan is designed to motivate the staff to work hard.这个利润分享计划就是要激励员工勤奋地工作。

剑桥雅思9阅读解析test2Passage1Question 1答案: H关键词: national policy定位原文: H段第1句“The New Zealand Government…”解题思路: 这一段的首句就以一种叙事口吻向考生交代了新西兰全国上下正在开展的一场为残疾人服务的战略,该句含义为“新西兰政府已经制定出一项‘新西兰残疾人事业发展战略’,并开始进入广泛咨询意见的阶段。

”另外,在该段其它语句中也提到the strategy recognises..., Objective 3...is to provide...等信息,非常符合题干中account一词的含义。

Question 2答案: C关键词: global team定位原文: C段最后一句“The International Institute of…”解题思路:这句含义为“在世界卫生组织的建议下,国际噪声控制工程学会(I-INCE)成立了一个国际工作小组来”,这句话中international能够对应题干中的global, 而working party能够对应team。

这是对应关系非常明显的一道题目。

Question 3答案: B关键词: hypothesis, reason, growth in classroom noise定位原文: B段第3句“Nelson and Soil have also suggested...”解题思路:在该段首句中就出现了classroom noise这个词,因此该段有可能就是本题的对应段落。

在接下来的叙述Nelson and Soil have also suggested...中,suggest一词能够对应题干中的hypothesis 后一句中的This all amounts to heightened activity and noise levels,与题干中的one reason相对应Question 4答案: I关键词: worldwide regulations对应原文: I 段最后一句“It is imperative that the needs…”解题思路:全文只有此句中提及国际标准,含义为“今后在制定和颁布国际标准时,必须把这些孩子的需求考虑进去。

高教版公共英语3级精讲班讲义9公共英语3级精讲班第9讲讲义MonologueMonologue 1:Language points:1.2004 TUC launched “Work Your Proper Hours Day” where workers were encouraged to take thelunch breaks they usually work through and leave for home at their contracted time.2004年英国劳工联合会提出“合理工作时间”这一号召。

鼓励工人中午休息并且按照合同的要求准时回家。

1)TUC: Trades Union Congress 英国劳工联合会2)Work Your Proper Hours Day:英国劳工联合会提倡的“合理工作时间”3)Contracted time:合同约定的时间2. Friday February 25 is the day in 2005 when the TUC estimates that people who do unpaid overtime will stop working for free and start to get paid.2005年2月25日是英国劳工联合会估计没有报酬加班的人们应该停止加班并开始得到报酬的日子。

unpaid overtime 没有报酬的加班工作3. The TUC is urging people who do unpaid overtime to “work your proper hours” on that day, takinga proper lunch-break , and arriving and leaving wok on time.英国劳工联合会激励没报酬加班的人们在那天“合理工作”,进行合理的午休,按时上下班。

新概念英语第三册逐句精讲:第9课飞猫Flying Cats 飞猫新概念3课文内容:Cats never fail to fascinate human beings. They can be friendly and affectionate towards humans, but they lead mysterious lives of their own as well. They never become submissive like dogs and horses. As a result, humans have learned to respect feline independence. Most cats remain suspicious of humans all their lives. One of the things that fascinates us most about cats is the popular belief that they have nine lives. Apparently, there is a good deal of truth in this idea. A cat's ability to survive falls is based on fact.Recently the New York Animal Medical Center made a study of 132 cats over a period of five months. All these cats had one experience in common: they had fallen off high buildings, yet only eight of them died from shock or injuries. Of course, New York is the ideal place for such an interesting study, because there is no shortage of tall buildings. There are plenty of high-rise windowsills to fall from! One cat, Sabrina, fell 32 storeys, yet only suffered from a broken tooth. 'Cats behave like well-trained paratroopers.' a doctor said.It seems that the further cats fall, the less they are likely to injure themselves. In a long drop, they reach speeds of 60 miles an hour and more. At high speeds, falling cats have time to relax. They stretch out their legs like flying squirrels. This increases theirair-resistance and reduces the shock of impact when they hit the ground.新概念英语3逐句精讲:1.Cats never fail to fascinate human beings.猫总能引起人们的极大兴趣。

雅思精讲阅读班精讲班第7讲讲义Questions 22-24What is a dinosaur?A. Although the name dinosaur is derived from the Greek for “terrible lizard”, dinosaurs were not, in fact,lizards at all. Like lizards, dinosaurs are included in the class Reptilia, or reptiles, one of the five main classes of Vertebrata, animals with backbones. However, at the next level of classification, within reptiles, significant differences in the skeletal anatomy of lizards and dinosaurs have led scientists to place these groups of animals into two different superorders: Lepidosauria, or lepidosaurs, and Archosauria, or archosaurs.B. Classified as lepidosaurs are lizards and snakes and their prehistoric ancestors. Included among the archosaurs, or “ruling reptiles”, are prehistoric and modern crocodiles, and the now extinct thecondonts, pterosaurs and dinosaurs. Paleontologists believe that both dinosaurs and crocodiles evolved, in the later years of the Triassic Period (c. 248-208 million years ago), from creatures called pseudosuchian thecodonts. Lizards, snakes and different types of thecondont are believed to have evolved earlier in the Triassic Period from reptiles known as eosuchians.C. The most important skeletal differences between dinosaurs and other archosaurs are in the bones of the skull, pelvis and limbs. Dinosaur skulls are found in a great range of shapes and sizes, reflecting the different eating habits and lifestyles of a large and varied group of animals that dominated life on Earth for an extraordinary 165 million years. However, unlike the skulls of any other known animals, the skulls of dinosaurs had two long bones known as vomers. These bones extended on either side of the head, from the front of the snout to the level of the holes in the skull known as the antorbital fenestra, situated in front of the dinosaur’s orbits or eyesockets.D. All dinosaurs, whether large or small, quadrupedal or bipedal, fleet-footed or slow-moving, shared a common body plan. Identification of this plan makes it possible to differentiate dinosaurs from any other types of animal, even other archosaurs. Most significantly, in dinosaurs, the pelvis and femur had evolved so that the hind limbs were held vertically beneath the body, rather than sprawling out to the sides like the limbs of a lizard. The femur of a dinosaur had a sharply in-turned neck and a ball-shaped head, which slotted into a fully open acetabulum or hip socket. A supra-acetabular crest helped prevent dislocation of the femur. The position of the knee joint, aligned below the acetabulum, made it possible for the whole hind limb to swing backwards and forwards. This unique combination of features gave dinosaurs what is know as a “fully improved gait”. Evolution of this highly efficient method of walking also developed in mammals,but among reptiles it occurred only in dinosaurs.E. For the purpose of further classification, dinosaurs are divided into two orders: Saurischia, or saurischian dinosaurs, and Ornithischia, or ornithischian dinosaurs. This division is made on the basis of their pelvic anatomy. All dinosaurs had a pelvic girdle with each side comprised of three bones: the pubis, llium and ischium. However, the orientation of these bones follows one of two patterns. In saurischian dinosaurs, also known as lizard-hipped dinosaurs, the pubis points forwards, as is usual in most types of reptile. By contrast, in ornithischian, or bird-hipped, dinosaurs, the pubis points backwards towards the rear of the animal, which is also true of birds.(26F. Of the two orders of dinosaurs, the Saurischia was the larger and the first to evolve. It is divided into two suborders: Therapoda, or therapods, and Sauropodomorpha, or sauropodomorphs. The therapods, or “beast feet”, were bipedal, predatory carnivores. They ranged in size from the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex, 12m long, 5.6m tall and weighing as estimated 6.4 tonnes, to the smallest known dinosaur, Compsognathus, a mere 1.4m long and estimated 3kg in weight when fully grown. The sauropodomorphs, or “lizard feet forms”, included both bipedal and quandrupedal dinosaurs. Some sauropodomorphs were carnivorous or omnivorous but later species were typically herbivorous. They included some of the largest and best-known of all dinosaurs, such as Diplodocus, a huge quadruped with an elephant-like body, a long, thin tail and neck that gave it a total length of 27m, and a tiny head.G. Ornithischia dinosaurs were bipedal or quadrupedal herbivores. They are now usually divided into three suborders: Ornithipoda, Thyreophora and Marginocephalia. The ornithopods, or “bird feet”, both large and small, could walk or run on their long hind legs, balancing their body by holding their tails stiffly off the ground behind them. An example is lguanodon, up to 9m long, 5m tall and weighing 4.5 tonnes. The thyreophorans, or “shield bearers”, also known as armoured dinosaurs, were quadrupeds with rows of protective bony spikes, studs, or plates along their backs and tails. They included Stegosaurus, 9m long and weighing 2 tonnes.H. The marginocephalians, or “margined heads”, were bipedal or quadrupedal ornithischians with a deep bony frill or narrow shelf at the back of the skull. An example is Triceratops a rhinoceros-like dinosaur, 9m long, weighing 5.4 tonnes and bearing a prominent neck frill and three large horns.Questions 22-24Complete the sentences below. Use NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each blank space.Write your answers in Boxes 22-24 on your answer sheet.22.Lizards and dinosaurs are classified into two different superorders because of the difference intheir .23. In the Triassic period, evolved into thecondonts, for example, lizards and snakes.24.Dinosaur skulls differed from those of any other known animals because of the presence o .f vomers:。

雅思精讲阅读班精讲班第9讲讲义Questions 26-32PracticeYou are advised to spend about 20 minutes on Questions 26-38 which are based on Reading Passage 3.Wild Foods of AustraliaOver 120 years ago, the English botanist J. D. Hooker, writing of Australian edible plants, suggested that many of them were 'eatable but not worth eating'. Nevertheless, the Australian flora, together with the fauna, supported the Aboriginal people well before the arrival of Europeans. The Aborigines were not farmers and were wholly dependent for life on the wild products around them. They learned to eat, often after treatment, a wide variety of plants.The conquering Europeans displaced the Aborigines, killing many, driving others from their traditional tribal lands, and eventually settling many of the tribal remnants on government reserves, where flour and beef replaced nardoo and wallaby as staple foods. And so, gradually, the vast store of knowledge, accumulated over thousands of years, fell into disuse. Much was lost.However, a few European men took an intelligent and even respectful interest in the people who were being displaced. Explorers. missionaries, botanists, naturalists and government officials observed, recorded and. fortunately in some cases, published. Today we can draw on these publications to form the main basis of our knowledge of the edible, natural products of Australia. The picture is no doubt mostly incomplete. We can only speculate on the number of edible plants on which no observation was recorded.Not all our information on the subject comes from the Aborigines. Times were hard in the early days of European settlement, and traditional foods were often in short supply orimpossibly expensive for a pioneer trying to establish a farm in the bush. And so necessity led to experimentation just as it must have done for the Aborigines and experimentation led to some lucky results. So far as is known, the Aborigines made no use of Leptospermum or Dodonaea as food plants, yet the early settlers found that one could be used as a substitute for tea and the other for hops. These plants are not closely related to the species they replaced, so their use was not based on botanical observation. Probably some experiments had less happy endings; L. J. Webb has used the expression eat, die and learn in connection with the Aboriginal experimentation, but it was the successful attempts that became widely known. It is possible the edibility of some native plants used by the Aborigines was discovered independently by the European settlers or their descendants.Explorers making long expeditions found it impossible to carry sufficient food for the whole journey and were forced to rely, in part, on food that they could find on the way. Still another source of information comes from the practice in other countries. There are many species from northern Australia which occur also in southeast Asia, where they are used for food.In general, those Aborigines living in the dry inland areas were largely dependent for their vegetable foods on seed such as those of grasses, acacias and eucalypts. They ground these seeds between flat stones to make a coarse flour. Tribes on the coast, and particularly those in the vicinity of coastal rainforests, had a more varied vegetable diet with a higher proportion of fruits and tubers. Some of the coastal plants, even if they had grown inland, probably would have been unavailable as food since they required prolonged washing or soaking to render them non-poisonous; many of the inland tribes could not obtain water in the quantities necessary for such treatment. There was also considerable variation in the edible plants available to Aborigines in different latitudes. In general, the people who lived in the moist tropical areas enjoyed a much greater variety, than those in the southern part of Australia.With all the hundreds of plant species used for food by the Australian Aborigines, it is perhaps surprising that only one, the Queensland nut. has entered into commercial cultivation as a food plant. The reason for this probably does not lie with an intrinsic lack of potential in Australian flora, but rather with the lack of exploitation of this potential. In Europe and Asia, for example, the main food plants have had the benefit of many centuries of selection and hybridisation, which has led to the production of forms vastly superior to those in the wild. Before the Europeans came, the Aborigines practised no agriculture and so there was no opportunity for such improvement; either deliberate or unconscious, in the quality of the edible plants.Since 1788, there has, of course, been opportunity for selection of Australian food plants which might have led to the production of varieties that were worth cultivating. But Australian plants have probably 'missed the bus'. Food plants from other regions were already so far in advance after a long tradition of cultivation that it seemed hardly worth starting work on Australian species. Undoubtedly, the native raspberry, for example, could, with suitable selection and breeding programs, be made to yield a high-class fruit; but Australians already enjoy good raspberries from other areas of the world and unless some dedicated amateur plant breeder takes up the task, the Australian raspberries are likely to remain unimproved.And so, today, as the choice of which food plants to cultivate in Australia has been largely decided, and as there is little chance of being lost for long periods in the bush. our interest in the subject of Australian food plants tends to relate to natural history rather than to practical necessity.Questions 26-32Do the following statements reflect the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3 ? In boxes 26-32 write:YES if the statement reflects the writer’s claimsNO if the statement contradicts the writerNOT GIVEN if there is no information about this in the passage26. Most of the pre-European Aboriginal knowledge of wild foods has been recovered.27. There were few food plants unknown to pre-European Aborigines.28. Europeans learned all of what they knew of edible wild plants from Aborigines.29. Dodonaea is an example of a plant used for food by both pre-European Aborigines and European settlers.30. Some Australian food plants are botanically related to plants outside Australia.31. Pre-European Aboriginal tribes closer to the coast had access to a greater variety of food plants than tribes further inland.32. Some species of coastal food plants were also found inland.Questions 33-35Choose the appropriate letters (A-D) and write them in boxes 33-35 on your answer sheet.33. Wallaby meat...A was regularly eaten by Aborigines before European settlement.B was given by Aborigines in exchange for foods such as flour.C was a staple food on government reserves.D was produced on farms before European settlement.34. Experimentation with wild plants ...A depended largely on botanical observation.B was unavoidable for early settlers in all parts of Australia.C led Aborigines to adopt Leptospermum as a food plant.D sometimes had unfortunate results for Aborigines.35. Wild plant use by Aborigines …A was limited to dry regions.B was restricted to seed.C sometimes required the use of tools.D was more prevalent in the southern part of Australia.Questions 36-38Complete the partial summary below. Choose ONE or TWO words from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 36-38 on your answer sheet.Despite the large numbers of wild plants that could be used for food. only one, the ... (36) .... is being grown as a cash crop. Other edible plants in Australia, however, much potential they have for cultivation, had not gone through the lengthy process of ... (37) ... that would allow their exploitation, because Aborigines were not farmers. Thus species such as the ...(38) ..., which would be an agricultural success had it not bad to compete with established European varieties at the time of European settlement, are of no commercia。

第9课--精品讲义P57快速阅读第一篇Reading ComprehensionPart I Fast ReadingDirections: In this part, you will have 15 minutes to go over the passage quickly and answer the questions on Answer Sheet.For questions 1-7, choose the best answer from the choices marked A), B), C) and D).For questions 8-10, complete the sentences with the information given in the passage.OrFor questions 1-7, markY (for YES) if the statement agrees with the information given in the passage;N (for NO) if the statement contradicts the information given in the passage;NG (for NOT GIVEN) if the information is not given in the passage.Passage 1Family SociologyThe basic family structuresThe structure of the family and the needs that the family fulfills vary from society to society. The nuclear family—two adults and their children—is the main family unit in most Western societies. In others, especially in Asian societies, it is a subordinate part of an extended family unit, which also consists of grandparents and other relatives. A third type of family unit, which is becoming more prevalent, is the single-parent family, in which children live with an unmarried, divorced, or widowed mother or father.History and evolution of the family unitThe family unit began primarily as an economic unit; men hunted, while women gathered and prepared food and tended children. Infanticide and expulsion of the infirm that could not work were common. Later, with the advent of Christianity, marriage and childbearing became central concerns in religious teaching. However, after the Reformation, which began in the 1500s, the purely religious nature of family ties was partly abandoned in favor of civil bonds. Today, most Western nations now recognize the family relationship as primarily a civil matter rather than a religious one.The Modern FamilyThe modern family differs from earlier traditional forms, primarily in its functions, composition, and life cycle and in the roles of husbands and wives. Many of the functions that were once performed by or within the traditional family unit are now performed by or within community institutions, e.g., economic production (work), education, and recreation. In the modern family, members now work in different occupations and in locations away from the home. Education is provided by the state or by private groups. Organized recreational activities often take place outside the home. The family is still responsible for the socialization of children. Even in this capacity, the influence of peers and of the mass media has assumed a larger role.Family composition in industrial societies has also changed dramatically. The average number of children born to a woman in the United States, for example, fell from 7.0 in 1800 to 2.0 by the early 1990s. Consequently, the number of years separating the births of the youngest and oldest children has declined. This has occurred in conjunction with increased longevity. In earliertimes, marriage normally dissolved through the death of a spouse before the youngest child left home.Today husbands and wives potentially have about as many years together after the children leave home as before.During the 20th century, extended family households declined in prevalence. This change is associated particularly with increased residential mobility and with diminished financial responsibility of children for aging parents, as pensions from jobs and government-sponsored benefits for retired people became more common.By the 1970s, the prototypical nuclear family had yielded somewhat to modified structures including the one-parent family, the stepfamily, and the childless family. One-parent families in the past were usually the result of the death of a spouse. Now, however, most one-parent families are the result of divorce, although some are created when unmarried mothers bear children. In 1991, more than one out of four children lived with only one parent, usually the mother. Most one-parent families, however, eventually became two-parent families through remarriage.A stepfamily is created by a new marriage of a single parent. It may consist of a parent and children and a childless spouse, a parent and children and a spouse whose children live elsewhere, or two joined one-parent families. In a stepfamily, problems in relations between non-biological parents and children may generate tension; the difficulties can be especially great in the marriage of single parents when the children of both parents live with them as siblings.Childless families may be increasingly the result of deliberate choice and the availability of birth control. For many years, theproportion of couples that were childless declined steadily as venereal and other diseases that cause infertility were conquered. In the 1970s, however, the changes in the status of women reversed this trend. Couples often elect to have no children or to postpone having them until their careers are well established.Since the 1960s, several variations on the family unit have emerged. More unmarried couples are living together, before or instead of marrying. Some elderly couples, most often widowed, are finding it more economically practical to cohabit without marrying.World trendsAll industrial nations are experiencing family trends similar to those found in the United States. The problem of unwed mothers—especially very young ones and those who are unable to support themselves—and their children is an international one, although improved methods of birth control and legalized abortion have slowed the trend somewhat. Divorce is increasing even where religious and legal impediments to it are strongest.Unchecked population growth in developing nations threatens the family system. The number of surviving children in a family has rapidly increased as infectious diseases, famine, and other causes of child mortality have been reduced. Because families often cannot support so many children, the reduction in infant mortality has posed a challenge to the nuclear family and to the resources of developing nations.1.The family unit first began as a product of religious teaching.[Y][N][NG]2.Presently, most western countries view the family relationship as essentially a civilmatter.[Y][N][NG]3.Due to changes in function, the modern family is weaker than earlier traditional forms.[Y][N][NG]4.Peer influence and mass media have played a bigger role in the socialization ofchildren.[Y][N][NG]5.During the 20th century, extended family households became more common.[Y][N][NG]6.Some elderly couples prefer living together without marriage because it is morepractical.[Y][N][NG]7.Divorce is slowly decreasing, especially where religious and legal impediments arestrongest.[Y][N][NG]8.The main family unit in most western societies is the _______________________.9.Now, most single-parented families result from ____________________.10.Childless families may be increasingly the result of deliberate choice and the____________________ birth control.。

雅思精讲阅读班精讲班第9讲讲义Questions 26-32PracticeYou are advised to spend about 20 minutes on Questions 26-38 which are based on Reading Passage 3.Wild Foods of AustraliaOver 120 years ago, the English botanist J. D. Hooker, writing of Australian edible plants, suggested that many of them were 'eatable but not worth eating'. Nevertheless, the Australian flora, together with the fauna, supported the Aboriginal people well before the arrival of Europeans. The Aborigines were not farmers and were wholly dependent for life on the wild products around them. They learned to eat, often after treatment, a wide variety of plants.The conquering Europeans displaced the Aborigines, killing many, driving others from their traditional tribal lands, and eventually settling many of the tribal remnants on government reserves, where flour and beef replaced nardoo and wallaby as staple foods. And so, gradually, the vast store of knowledge, accumulated over thousands of years, fell into disuse. Much was lost.However, a few European men took an intelligent and even respectful interest in the people who were being displaced. Explorers. missionaries, botanists, naturalists and government officials observed, recorded and. fortunately in some cases, published. Today we can draw on these publications to form the main basis of our knowledge of the edible, natural products of Australia. The picture is no doubt mostly incomplete. We can only speculate on the number of edible plants on which no observation was recorded.Not all our information on the subject comes from the Aborigines. Times were hard in the early days of European settlement, and traditional foods were often in short supply orimpossibly expensive for a pioneer trying to establish a farm in the bush. And so necessity led to experimentation just as it must have done for the Aborigines and experimentation led to some lucky results. So far as is known, the Aborigines made no use of Leptospermum or Dodonaea as food plants, yet the early settlers found that one could be used as a substitute for tea and the other for hops. These plants are not closely related to the species they replaced, so their use was not based on botanical observation. Probably some experiments had less happy endings; L. J. Webb has used the expression eat, die and learn in connection with the Aboriginal experimentation, but it was the successful attempts that became widely known. It is possible the edibility of some native plants used by the Aborigines was discovered independently by the European settlers or their descendants.Explorers making long expeditions found it impossible to carry sufficient food for the whole journey and were forced to rely, in part, on food that they could find on the way. Still another source of information comes from the practice in other countries. There are many species from northern Australia which occur also in southeast Asia, where they are used for food.In general, those Aborigines living in the dry inland areas were largely dependent for their vegetable foods on seed such as those of grasses, acacias and eucalypts. They ground these seeds between flat stones to make a coarse flour. Tribes on the coast, and particularly those in the vicinity of coastal rainforests, had a more varied vegetable diet with a higher proportion of fruits and tubers. Some of the coastal plants, even if they had grown inland, probably would have been unavailable as food since they required prolonged washing or soaking to render them non-poisonous; many of the inland tribes could not obtain water in the quantities necessary for such treatment. There was also considerable variation in the edible plants available to Aborigines in different latitudes. In general, the people who lived in the moist tropical areas enjoyed a much greater variety, than those in the southern part of Australia.With all the hundreds of plant species used for food by the Australian Aborigines, it is perhaps surprising that only one, the Queensland nut. has entered into commercial cultivation as a food plant. The reason for this probably does not lie with an intrinsic lack of potential in Australian flora, but rather with the lack of exploitation of this potential. In Europe and Asia, for example, the main food plants have had the benefit of many centuries of selection and hybridisation, which has led to the production of forms vastly superior to those in the wild. Before the Europeans came, the Aborigines practised no agriculture and so there was no opportunity for such improvement; either deliberate or unconscious, in the quality of the edible plants.Since 1788, there has, of course, been opportunity for selection of Australian food plants which might have led to the production of varieties that were worth cultivating. But Australian plants have probably 'missed the bus'. Food plants from other regions were already so far in advance after a long tradition of cultivation that it seemed hardly worth starting work on Australian species. Undoubtedly, the native raspberry, for example, could, with suitable selection and breeding programs, be made to yield a high-class fruit; but Australians already enjoy good raspberries from other areas of the world and unless some dedicated amateur plant breeder takes up the task, the Australian raspberries are likely to remain unimproved.And so, today, as the choice of which food plants to cultivate in Australia has been largely decided, and as there is little chance of being lost for long periods in the bush. our interest in the subject of Australian food plants tends to relate to natural history rather than to practical necessity.Questions 26-32Do the following statements reflect the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3 ? In boxes 26-32 write:YES if the statement reflects the writer’s claimsNO if the statement contradicts the writerNOT GIVEN if there is no information about this in the passage26. Most of the pre-European Aboriginal knowledge of wild foods has been recovered.27. There were few food plants unknown to pre-European Aborigines.28. Europeans learned all of what they knew of edible wild plants from Aborigines.29. Dodonaea is an example of a plant used for food by both pre-European Aborigines and European settlers.30. Some Australian food plants are botanically related to plants outside Australia.31. Pre-European Aboriginal tribes closer to the coast had access to a greater variety of food plants than tribes further inland.32. Some species of coastal food plants were also found inland.Questions 33-35Choose the appropriate letters (A-D) and write them in boxes 33-35 on your answer sheet.33. Wallaby meat...A was regularly eaten by Aborigines before European settlement.B was given by Aborigines in exchange for foods such as flour.C was a staple food on government reserves.D was produced on farms before European settlement.34. Experimentation with wild plants ...A depended largely on botanical observation.B was unavoidable for early settlers in all parts of Australia.C led Aborigines to adopt Leptospermum as a food plant.D sometimes had unfortunate results for Aborigines.35. Wild plant use by Aborigines …A was limited to dry regions.B was restricted to seed.C sometimes required the use of tools.D was more prevalent in the southern part of Australia.Questions 36-38Complete the partial summary below. Choose ONE or TWO words from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 36-38 on your answer sheet.Despite the large numbers of wild plants that could be used for food. only one, the ... (36) .... is being grown as a cash crop. Other edible plants in Australia, however, much potential they have for cultivation, had not gone through the lengthy process of ... (37) ... that would allow their exploitation, because Aborigines were not farmers. Thus species such as the ...(38) ..., which would be an agricultural success had it not bad to compete with established European varieties at the time of European settlement, are of no commercia。