大汉堡指数BMfile2000-Jul2015

- 格式:xls

- 大小:210.00 KB

- 文档页数:2

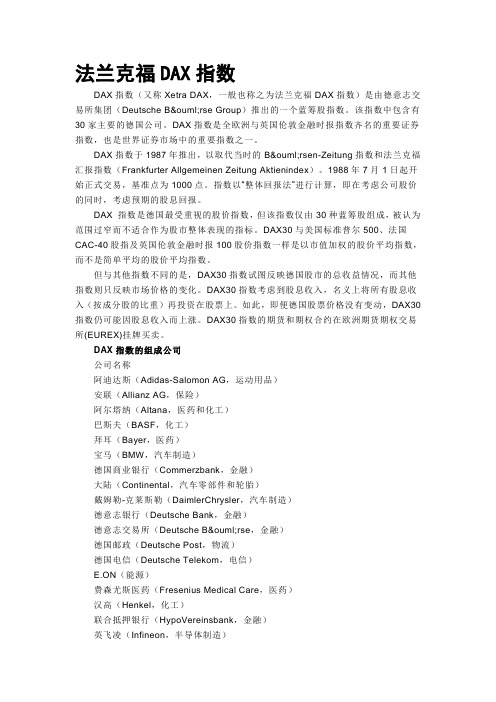

法兰克福DAX指数DAX指数(又称Xetra DAX,一般也称之为法兰克福DAX指数)是由德意志交易所集团(Deutsche Börse Group)推出的一个蓝筹股指数。

该指数中包含有30家主要的德国公司。

DAX指数是全欧洲与英国伦敦金融时报指数齐名的重要证券指数,也是世界证券市场中的重要指数之一。

DAX指数于1987年推出,以取代当时的Börsen-Zeitung指数和法兰克福汇报指数(Frankfurter Allgemeinen Zeitung Aktienindex)。

1988年7月1日起开始正式交易,基准点为1000点。

指数以“整体回报法”进行计算,即在考虑公司股价的同时,考虑预期的股息回报。

DAX 指数是德国最受重视的股价指数,但该指数仅由30种蓝筹股组成,被认为范围过窄而不适合作为股市整体表现的指标。

DAX30与美国标准普尔500、法国CAC-40股指及英国伦敦金融时报100股价指数一样是以市值加权的股价平均指数,而不是简单平均的股价平均指数。

但与其他指数不同的是,DAX30指数试图反映德国股市的总收益情况,而其他指数则只反映市场价格的变化。

DAX30指数考虑到股息收入,名义上将所有股息收入(按成分股的比重)再投资在股票上。

如此,即便德国股票价格没有变动,DAX30指数仍可能因股息收入而上涨。

DAX30指数的期货和期权合约在欧洲期货期权交易所(EUREX)挂牌买卖。

DAX指数的组成公司公司名称阿迪达斯(Adidas-Salomon AG,运动用品)安联(Allianz AG,保险)阿尔塔纳(Altana,医药和化工)巴斯夫(BASF,化工)拜耳(Bayer,医药)宝马(BMW,汽车制造)德国商业银行(Commerzbank,金融)大陆(Continental,汽车零部件和轮胎)戴姆勒-克莱斯勒(DaimlerChrysler,汽车制造)德意志银行(Deutsche Bank,金融)德意志交易所(Deutsche Börse,金融)德国邮政(Deutsche Post,物流)德国电信(Deutsche Telekom,电信)E.ON(能源)费森尤斯医药(Fresenius Medical Care,医药)汉高(Henkel,化工)联合抵押银行(HypoVereinsbank,金融)英飞凌(Infineon,半导体制造)林德(Linde,化工)汉莎航空(Lufthansa,航空运输)MAN(汽车及机械制造)麦德龙(Metro,商品零售)慕尼黑再保险(Münchener Rück,保险)RWE(能源)SAP(软件研发)先灵(Schering,医药)西门子(Siemens,电器制造)蒂森克虏伯(ThyssenKrupp,钢铁、建筑及制造业)TUI(旅游)大众汽车(Volkswagen,汽车制造)。

“巨无霸指数”及其局限性分析——以人民币汇率为例一、理论基础——购买力平价理论购买力平价理论是一种研究和比较各国不同的货币之间购买力关系的理论。

该理论认为:人们对外国货币的需求是由于用它可以购买外国的商品和劳务,外国人需要其本国货币也是因为用它可以购买其国内的商品和劳务。

因此,本国货币与外国货币相交换,就等于本国与外国购买力的交换。

所以,用本国货币表示的外国货币的价格也就是汇率,决定于两种货币的购买力比率。

由于购买力实际上是一般物价水平的倒数,因此两国之间的货币汇率可由两国物价水平之比表示。

购买力平价理论包括绝对购买力平价(Absolute PPP)和相对购买力平价(Relative PPP)。

(一)绝对购买力平价(Absolute PPP)指本国货币与外国货币之间的均衡汇率等于本国与外国货币购买力或物价水平之间的比率。

绝对购买力平价认为:一国货币的价值及对它的需求是由单位货币在国内所能买到的商品和劳务的量决定的,即由它的购买力决定的,因此两国货币之间的汇率可以表示为两国货币的购买力之比。

而购买力的大小是通过物价水平体现出来的。

根据这一关系式,本国物价上涨将意味着本国货币相对外国货币的贬值。

(二)相对购买力平价(Relative PPP)指不同国家的货币购买力之间的相对变化,是汇率变动的决定因素。

认为汇率变动的主要因素是不同国家之间货币购买力或物价的相对变化;同汇率处于均衡的时期相比,当两国购买力比率发生变化。

则两国货币之间的汇率就必须调整。

二、巨无霸指数(Big Mac index)巨无霸指数(Big Mac index)是英国《经济学家》杂志编制的一个不是很严谨的指数。

该杂志比较麦当劳巨无霸汉堡包(Bid Mac)在世界各地的价格,作为各国币值是否被低估或高估的指南。

其假设是“一价定律”,即相似的食品无论在哪里销售,其价格应当是相同的,价格有差别意味着币值出现异常情况。

采取的是为绝对购买力平价理论。

fat mass index 指数-概述说明以及解释1.引言1.1 概述概述部分的内容:FAT Mass Index(FMI)是一种用于评估个体身体脂肪含量的指数。

随着肥胖问题在全球范围内呈现出快速增长的趋势,对肥胖的评估和管理变得越来越重要。

传统的肥胖评估方法主要依赖于体重指数(BMI),然而BMI无法准确反映个体的体脂水平。

FAT Mass Index的提出填补了这一空白,它通过考虑体脂含量和身体大小的关系来提供更精确的肥胖评估结果。

FAT Mass Index的计算方法主要基于个体的身高、体重和体脂含量。

与BMI相比,FAT Mass Index更能够准确地反映出一个人的脂肪质量,并对其健康状况进行综合评估。

通过使用FAT Mass Index,我们可以更好地理解人们的体脂分布情况,从而更好地预测肥胖相关的风险。

本文旨在介绍FAT Mass Index的定义和计算方法,并探讨它与身体健康之间的关系。

我们将着重讨论FAT Mass Index在肥胖评估中的应用以及其局限性,同时也提出一些可能的改进方法。

通过研究FAT Mass Index,我们可以更全面地了解肥胖问题,为制定个体化的肥胖管理策略提供更有力的支持。

1.2 文章结构文章结构:本文将通过以下几个部分对FAT Mass Index(FMI)进行探讨。

首先,引言部分将对本文的概述、文章结构和目的进行介绍。

随后,在正文部分,将详细阐述FMI的定义与计算方法,以及FMI与身体健康之间的关系。

最后,在结论部分,将探讨FMI在肥胖评估中的应用,并讨论FMI的局限性与改进的可能性。

通过以上结构,读者将能够全面了解FAT Mass Index(FMI)以及它与身体健康的联系。

文章的结构清晰且有条理,让读者能够系统地了解FMI 的定义、计算方法,以及它在肥胖评估中的应用。

同时,我们也将深入讨论FMI的局限性,并提出改进的可能方向,以帮助读者更好地理解FMI 的实际应用价值。

作业:P706.已知某百货公司三个躺售人员对明年销售的预测意见与主观概率如下表,又知计划人员预测销售的期望值为1000万元,统计人员的预测销售的期望值为900万元,计划、统计人员的预测能力分别是销售人员的1.2倍和1.4倍。

试用主观概率加权平均法求:(1)每位销售人员的预测销售期望值。

(2)三位销售人员的平均预测期望值。

(3)该公司明年的预测销售额。

销曾人员顼测期望值计鼻衰解:(1)甲:销售期望值=Z销售额x主观概率=1120*0.25+965*0.5+640*0.25=922.5 (万元)同理,可求得乙和丙的销售期望值为900万元和978万元(2)922.5*0.3+900*0.35+978*0.35=934.05 (万元)(3)(934.05+1000* 1.2+900* 1.4) / (1+1.2+1.4) =942.79 (万元)7,已知某工业公司选定10位专家用德尔菲法进行预测,最后一轮征询意见,对明年利润率的估计的累计概率分布如下表:试用累计概率中位数法:(1)计算每种概率的不同意见的平均数,用累计概率确定中位效,作为点解:(1(2)预测误差为1%,则预测区间为8.2%±1%,为[7. 2%, 9.2%] ,区间概率为1 -1%=99%作业(P116)1.江苏省2004年1-11月社会消费品零售总额如下表所示,试分别以3个月和5个月移动平均法,2.1995—2002年全国财政收入如下表所示,试用加权移动平均法预测2003年财政收入(三年加权系数为0.5、1、3、我国1995-2002年全社会固定资产投资额如下表所示,试用一次指数平滑法预测2003年全社会固定资产投资额(取a =0.3,4.我国1995—2002(1)试用趋势移动平均法(取N=3)建立全国城乡居民年底定期存款余额预测模型。

(2)分别取a =0.3, a =0.6,以及S" = =(匕+匕+匕)/3 = 28292.8建立全国城乡居民年底定期存款余额的直线指数平滑预测模型。

面板数据F检验1.面板数据定义。

时间序列数据或截面数据都是一维数据。

例如时间序列数据是变量按时间得到的数据;截面数据是变量在截面空间上的数据。

面板数据(panel data)也称时间序列截面数据(time series and cross section data)或混合数据(pool data)。

面板数据是同时在时间和截面空间上取得的二维数据。

面板数据示意图见图1。

面板数据从横截面(cross section)上看,是由若干个体(entity, unit, individual)在某一时刻构成的截面观测值,从纵剖面(longitudinal section)上看是一个时间序列。

面板数据用双下标变量表示。

例如y i t, i= 1, 2, …, N; t= 1, 2, …, TN表示面板数据中含有N个个体。

T表示时间序列的最大长度。

若固定t不变,y i ., ( i= 1, 2, …, N)是横截面上的N个随机变量;若固定i不变,y. t, (t= 1, 2, …, T)是纵剖面上的一个时间序列(个体)。

图1 N=7,T=50的面板数据示意图例如1990-2000年30个省份的农业总产值数据。

固定在某一年份上,它是由30个农业总产总值数字组成的截面数据;固定在某一省份上,它是由11年农业总产值数据组成的一个时间序列。

面板数据由30个个体组成。

共有330个观测值。

对于面板数据y i t, i= 1, 2, …, N; t= 1, 2, …, T来说,如果从横截面上看,每个变量都有观测值,从纵剖面上看,每一期都有观测值,则称此面板数据为平衡面板数据(balanced panel data)。

若在面板数据中丢失若干个观测值,则称此面板数据为非平衡面板数据(unbalanced panel data)。

注意:EViwes 3.1、4.1、5.0既允许用平衡面板数据也允许用非平衡面板数据估计模型。

例1(file:panel02):1996-2002年中国东北、华北、华东15个省级地区的居民家庭人均消费(不变价格)和人均收入数据见表1和表2。

MBSI指数:深度解析与应用在金融市场中,投资者经常需要依赖各种指标来评估市场的状况、趋势以及潜在的风险和机会。

其中,MBSI指数(请注意,此名称可能是虚构的或特定于某个领域,因为在我最后的知识更新中并没有广泛公认的“MBSI指数”。

但为了配合您的要求,我将基于此虚构名称进行描述。

)作为一个重要的分析工具,为投资者提供了独特的市场洞见。

本文将对MBSI指数进行详细的探讨,包括其定义、计算方法、应用场景、优势与局限,以及如何利用该指数制定投资策略。

一、MBSI指数的定义MBSI指数,全称为“Market Breadth and Sentiment Index”,即市场广度与情绪指数,是一个综合反映市场整体情绪和广度的指标。

它通过量化分析市场中参与者的交易行为、价格变动以及成交量等多个维度的数据,来评估市场的活跃程度、趋势强度以及投资者的情绪状态。

二、MBSI指数的计算方法1.MBSI指数的计算通常涉及以下几个步骤:2.数据收集:首先,收集市场中相关的交易数据,包括但不限于股票价格、成交量、买卖盘比例等。

3.数据处理:对这些原始数据进行清洗、归一化等预处理操作,以消除异常值和数据尺度差异对指数计算的影响。

4.权重分配:根据每个数据维度的重要性和相关性,为其分配相应的权重。

例如,成交量和价格变动可能被视为更重要的指标,因此会被赋予更高的权重。

5.指数计算:将处理后的数据与相应的权重相结合,通过特定的算法(如加权平均、指数平滑等)计算出MBSI指数的值。

6.指数调整:为了使MBSI指数更具可比性和解释性,可能还需要对其进行标准化或归一化处理。

三、MBSI指数的应用场景1.MBSI指数在多个金融领域具有广泛的应用价值,主要包括以下几个方面:2.市场监测:MBSI指数可以作为市场监测工具,帮助投资者实时了解市场的整体情绪和广度变化,从而及时调整投资策略。

3.趋势判断:通过分析MBSI指数的历史数据,投资者可以判断市场的长期趋势和中短期波动,为投资决策提供参考依据。

Economics focusMcCurrenciesMay 25th 2006From The Economist print editionHappy 20th birthday to our Big Mac indexWHEN our economics editor invented the Big Mac index in 1986 as a light-hearted introduction to exchange-rate theory, little did she think that 20 years later she would still be munching her way, a little less sylph-like, around the world. As burgernomics enters its third decade, the Big Mac index is widely used and abused around the globe. It is time to take stock of what burgers do and do not tell you about exchange rates.The Economist's Big Mac index is based on one of the oldest concepts in international economics: the theory of purchasing-power parity (PPP), which argues that in the long run, exchange rates should move towards levels that would equalise the prices of an identical basket of goods and services in any two countries. Our “basket” is a McDonald's Big Mac, produced in around 120 countries. The Big Mac PPP is the exchange rate that would leave burgers costing the same in America as elsewhere. Thus a Big Mac in China costs 10.5 yuan, against an average price in four American cities of $3.10 (see the first column of the table). To make the two prices equal would require an exchange rate of 3.39 yuan to the dollar, compared with a market rate of 8.03. In other words, the yuan is 58% “undervalued” against the dollar. To put it another way, converted into dollars at market rates the Chinese burger is the cheapest in the table.In contrast, using the same method, the euro and sterling are overvalued against the dollar, by 22% and 18% respectively; the Swiss and Swedish currencies are even more overvalued. On the other hand, despite its recent climb, the yen appears to be 28% undervalued, with a PPP of only ¥81 to the dollar. Note that all emerging-market currencies also look too cheap.The index was never intended to be a precise predictor of currency movements, simply a take-away guide to whether currencies are at their “correct” long-run level. Curiously, however, burgernomics has an impressive record in predicting exchange rates: currencies that show up as overvalued often tend to weaken in later years. But you must always remember the Big Mac's limitations. Burgers cannot sensibly be traded across borders and prices are distorted by differences in taxes and the cost of non-tradable inputs, such as rents.Despite our frequent health warnings, some American politicians are fond of citing the Big Mac index rather too freely when it suits their cause—most notably in their demands for a big appreciation of the Chinese currency in order to reduce America's huge trade deficit. But the cheapness of a Big Mac in China does not really prove that the yuan is being held far below its fair-market value. Purchasing-power parity is a long-run concept. It signals where exchange rates are eventually heading, but it says little about today's market-equilibrium exchange rate that would make the prices of tradable goods equal. A burger is a product of both traded and non-traded inputs.An idea to relishIt is quite natural for average prices to be lower in poorer countries than in developedones. Although the prices of tradable things should be similar, non-tradable services will be cheaper because of lower wages. PPPs are therefore a more reliable way to convertGDP per head into dollars than market exchange rates, because cheaper prices mean that money goes further. This is also why every poor country has an implied PPP exchange rate that is higher than today's market rate, making them all appear undervalued. Both theory and practice show that as countries get richer and their productivity rises, their real exchange rates appreciate. But this does not mean that a currency needs to rise massively today. Jonathan Anderson, chief economist at UBS in Hong Kong, reckons that the yuan is now only 10-15% below its fair-market value. Even over the long run, adjustment towards PPP need not come from a shift in exchange rates; relative prices can change instead. For example, since 1995, when the yen was overvalued by 100% according to the Big Mac index, the local price of Japanese burgers has dropped by one-third. In the same period, American burgers have become one-third dearer. Similarly, the yuan's future real appreciation could come through faster inflation in China than in the United States.The Big Mac index is most useful for assessing the exchange rates of countries withsimilar incomes per head. Thus, among emerging markets, the yuan does indeed look undervalued, while the currencies of Brazil, Turkey, Hungary and the Czech Republic look overvalued. Economists would be unwise to exclude Big Macs from their diet, but Super Size servings would equally be a mistakeBig Mac indexJan 12th 2006From The Economist print editionThe Economist's Big Mac index is based on the theory of purchasing-power parity, under whichexchange rates should adjust to equalise the cost of a basket of goods and services, wherever it is bought around the world. Our basket is the Big Mac. The cheapest burger in our chart is in China, where it costs $1.30, compared with an average American price of $3.15. This implies that the yuan is 59% undervalued.The Big Mac IndexFood for thoughtMay 27th 2004From The Economist print editionThe world economy looks very different once countries' output is adjusted for differences in pricesHOW fast is the world economy growing? How important is China as an engine of growth? How much richer is the average person in America than in China? The answers to these huge questions depend crucially on how you convert the value of output in different countries into a common currency. Converting national GDPs into dollars at market exchange rates is misleading. Prices tend to be lower in poor economies, so a dollar of spending in China, say, is worth a lot more than a dollar in America. A better method is to use purchasing-power parities (PPP), which take account of price differences.The theory of purchasing-power parity says that in the long run exchange rates should move towards rates that would equalise the prices of an identical basket of goods and services in any two countries. This is the thinking behind The Economist's Big Mac index. Invented in 1986 as a light-hearted guide to whether currencies are at their “correct” level, our “basket” is a McDonalds' Big Mac, which is produced locally in almost 120 countries.The Big Mac PPP is the exchange rate that would leave a burger in any country costing the same as in America. The first column of our table converts the local price of a Big Mac into dollars at current exchange rates. The average price of a Big Mac in four American cities is $2.90 (including tax). The cheapest shown in the table is in the Philippines ($1.23), the most expensive in Switzerland ($4.90). In other words, the Philippine peso is the world's most undervalued currency, the Swiss franc its most overvalued.The second column calculates Big Mac PPPs by dividing the local currency price by the American price. For instance, in Japan a Big Mac costs ¥262. Dividing this by the American price of $2.90 produces a dollar PPP against the yen of ¥90, compared with its current rate of ¥113, suggesting that the yen is 20% undervalued. In contrast, the euro (based on a weighted average of Big Mac prices in the euro area) is 13% overvalued. But perhaps the most interesting finding is that all emerging-market currencies are undervalued against the dollar. The Chinese yuan, on which much ink has been spilled in recent months, looks 57% too cheap.The Big Mac index was never intended as a precise forecasting tool. Burgers are not traded across borders as the PPP theory demands; prices are distorted by differences in the cost of non-tradable goods and services, such as rents.Yet these very failings make the Big Mac index useful, since looked at another way it can help to measure countries' differing costs of living. That a Big Mac is cheap in China does not in fact prove that the yuan is being held massively below its fair value, as many American politicians claim. It is quite natural for average prices to be lower in poorer countries and therefore for their currencies to appear cheap.The prices of traded goods will tend to be similar to those in developed economies. But the prices of non-tradable products, such as housing and labour-intensive services, are generally much lower. A hair-cut is, for instance, much cheaper in Beijing than in New York.One big implication of lower prices is that converting a poor country's GDP into dollars at market exchange rates will significantly understate the true size of its economy and its living standards. If China's GDP is converted into dollars using the Big Mac PPP, it is almost two-and-a-half-times bigger than if converted at the market exchange rate. Meatier and more sophisticated estimates of PPP, such as those used by the IMF, suggest that the required adjustment is even bigger.Weight watchersThe global economic picture thus looks hugely different when examined through a PPP lens. Take the pace of global growth. Anyone wanting to calculate this needs to bundle together countries' growth rates, with each one weighted according to its share of world GDP. Using weights based on market exchange rates, the world has grown by an annual average of only 1.9% over the past three years. Using PPP, as the IMF does, global growth jumps to a far more robust 3.1% a year.The main reason for this difference is that using PPP conversion factors almost doubles the weight of the emerging economies, which have been growing much faster. Measured at market exchange rates, emerging economies account for less than a quarter of global output. But measured using PPP they account for almost half.Small wonder, then, that global economic rankings are dramatically transformed when they are done on a PPP basis rather than market exchange rates. America remains number one, but China leaps from seventh place to second, accounting for 13% of world output. India jumps into fourth place ahead of Germany, and both Brazil and Russia are bigger than Canada. Similarly, market exchange rates also exaggerate inequality. Using market rates, the average American is 33 times richer than the average Chinese; on a PPP basis, he is “only” seven times richer.The way in which economies are measured also has a huge impact on which country has contributed most to global growth in recent years. Using GDP converted at market rates China has accounted for only 7% of the total increase in the dollar value of global GDP over the past three years, compared with America's 25%. But on PPP figures, China has accounted for almost one-third of global real GDP growth and America only 13%.This helps to explain why commodity prices in general and oil prices in particular have been surging, even though growth has been relatively subdued in the rich world since 2000. Emerging economies are not only growing much faster than rich economies and are more intensive in their use of raw materials and energy, but they also account for a bigger chunk of global output if measured correctly. As Charles Dumas, an economist at Lombard Street Research, neatly puts it, even if a Chinese loaf is a quarter of the cost of a loaf in America, it uses the same amount of flour.All measures of PPP are admittedly imperfect. But most economists agree that they give a more accurate measure of the relative size of economies than market exchange rates—and a better understanding of some of the dramatic movements in world markets. The humble burger should be part of every economist's diet.The Economist's Big Mac indexFast food and strong currenciesJun 9th 2005From The Economist print editionHow much burger do you get for your euro, yuan or Swiss franc?Italians like their coffee strong and their currencies weak. That, at least, is the conclusion one can draw from their latest round of grumbles about Europe's single currency. But are the Italians right to moan? Is the euro overvalued?Our annual Big Mac index (see table) suggests they have a case: the euro is overvalued by 17% against the dollar. How come? The euro is worth about $1.22 on the foreign-exchange markets. A Big Mac costs €2.92, on average, in the euro zone and $3.06 in the United States. The rate needed to equalise the burger's price in the two regions is just $1.05. To patrons of McDonald's, at least, the single currency is overpriced.The Big Mac index, which we have compiled since 1986, is based on the notion that a currency's price should reflect its purchasing power. According to the late, great economist Rudiger Dornbusch, this idea can be traced back to the Salamanca school in 16th-century Spain. Since then, he wrote, the doctrine of purchasing-power parity (PPP) has been variously seen as a “truism, an empirical regularity or a grossly misleading simplification.”Economists lost some faith in PPP as a guide to exchange rates in the 1970s, after the world's currencies abandoned their anchors to the dollar. By the end of the decade, exchange rates seemed to be drifting without chart or compass. Later studies showed that a currency's purchasing power does assert itself over the long run. But it might take three to five years for a misaligned exchange rate to move even halfway back into line. Our index shows that burger prices can certainly fall out of line with each other. If he could keep the burgers fresh, an ingenious arbitrageur could buy Big Macs for the equivalent of $1.27 in China, whose yuan is the most undervalued currency in our table, and sell them for $5.05 in Switzerland, whose franc is the most overvalued currency. The impracticality of such a trade highlights some of the flaws in the PPP idea. Trade barriers, transport costs and differences in taxes drive a wedge between prices in different countries.More important, the $5.05 charged for a Swiss Big Mac helps to pay for the retail space in which it is served, and for the labour that serves it. Neither of these two crucial ingredients can be easily traded across borders. David Parsley, of Vanderbilt University, and Shang-Jin Wei, of the International Monetary Fund, estimate that non-traded inputs, such as labour, rent and electricity, account for between 55% and 64% of the price of a Big Mac.The two economists disassemble the Big Mac into its separate ingredients. They find that the parts of the burger that are traded internationally converge towards purchasing-power parity quite quickly. Any disparity in onion prices will be halved in less than nine months, for example. But the non-traded bits converge much more slowly: a wage gap between countries has a “half-life” of almost 29 months.Seen in this light, our index provides little comfort to Italian critics of the single currency. If the euro buys less burger than it should, perhaps inflexible wages, not a strong currency, are to blame.The Hamburger Standard (based on Dec 16, 2004 BigMac Prices)BigMac PriceCountryin Local Currencyin USdollarsActualExchange Rate1 USD =Over(+) / Under(-)Valuation againstthe dollar, %PurchasingPower PriceUnited States $3.00 3.00 1.00 - - Argentina Peso4.75 1.6278 2.918 -45.8533 1.58 Australia A$3.20 2.4521 1.305 -18.0077 1.07Brazil Real5.45 2.3681 2.3014 -20.9177 1.82Britain £1.99 3.5811 1.7995‡ 18.7691 0.66 Canada C$3.20 2.7346 1.1702 -8.5626 1.07China Yuan10.50 1.2962 8.1008 -56.7944 3.50Euro area €2.80 3.3952 0.8247 12.7683 0.93Hong Kong HK$12.00 1.546 7.7621 -48.4676 4.00 Hungary Forint523 2.572 203.34 -14.429 174.33 Indonesia Rupiah14,545 1.424 10214 -52.5357 4,848.33 Japan ¥260 2.3229 111.93 -22.5409 86.70 Malaysia M$5.10 1.3468 3.7867 -55.106 1.70 Mexico Peso24.0 2.2155 10.833 -26.1516 8.00New Zealand NZ$4.50 3.1427 1.4319 4.7559 1.50 Poland Zloty6.40 1.9964 3.2058 -33.5579 2.13 Russia Rouble41.501.4617 28.391 -51.2874 13.83 Singapore s$3.602.1378 1.684 -28.7411 1.20South Africa Rand14.05 2.185 6.4302 -27.2184 4.68South Korea Won2,500 2.4117 1036.6 -19.6411 833 Sweden Skr30.0 3.8941 7.704 29.8027 10 Switzerland SFr6.23 4.8638 1.2809 62.3858 2.08 Taiwan NT$75.25 2.2733 33.1015 -24.233 25.08 Thailand Baht60.0 1.4593 41.115 -51.356 20.00‡ Dollars per poundPurchasing Power Parity (PPP): is a measure of the relative purchasing power ofdifferent currencies. It is measured by the price of the same goods in different countries, translated by the exchange rate of that country's currency against a "base currency".How to read this table:In this case, the goods is the Big Mac. The first column of the table shows local-currency prices of a Big Mac. The second converts the prices into dollars using exchange rates(third column): The cheapest Big Macs is now in China, where it costs $1.30. At the other extreme, Big Mac fans in Switzerland have to pay $4.86.Given that Americans in four cities pay an average of $3.00, the yuan looks massively undervalued, the Swiss franc massively overvalued. The Over/Under valuation againstthe dollar (fourth column) is calculated as:(PPP - Exchange Rate)---------------------------------- x 100Exchange RateThe fifth column calculates Big Mac PPPs. For example, dividing the Japanese price (¥260) by the American price ($3.00) gives a dollar PPP of ¥86.70. On December 16th 2004, the exchange rate was ¥111.93, implying that the yen is 22.5% undervalued against the dollar.If the actual exchange rate is lower, then the BigMac theory says that you should expect the value of the Yen to go up until it reaches the PPP exchange rate. If the actual exchange rate is higher, then the BigMac theory says that you should expect the value of the Yen to go down until it reaches the PPP exchange rate.。

第1篇摘要随着生活节奏的加快,快餐已成为人们日常饮食的重要组成部分。

汉堡作为一种流行的快餐食品,备受消费者喜爱。

本文通过对汉堡的营养成分进行分析,旨在为消费者提供科学、全面的营养数据,以指导消费者合理选择和消费汉堡。

一、汉堡的营养成分1. 蛋白质汉堡中的主要蛋白质来源是牛肉、鸡肉或蔬菜等。

以牛肉汉堡为例,每100克牛肉汉堡含有约20克蛋白质。

蛋白质是人体必需的营养素,有助于维持身体组织的生长和修复。

2. 脂肪汉堡中的脂肪主要来源于面包、牛肉和调料。

以牛肉汉堡为例,每100克牛肉汉堡含有约20克脂肪。

脂肪是人体能量来源之一,但过量摄入会增加肥胖、心血管疾病等风险。

3. 碳水化合物汉堡中的碳水化合物主要来自面包和蔬菜。

以牛肉汉堡为例,每100克牛肉汉堡含有约40克碳水化合物。

碳水化合物是人体主要的能量来源,有助于维持正常的生理功能。

4. 维生素和矿物质汉堡中的维生素和矿物质主要来源于蔬菜、面包和调料。

以牛肉汉堡为例,每100克牛肉汉堡含有约2毫克维生素A、0.3毫克维生素E、0.3毫克维生素B1、0.2毫克维生素B2、0.3毫克烟酸、0.2毫克维生素B6、0.1毫克维生素B12、0.1毫克泛酸、0.2毫克钙、0.2毫克铁、0.1毫克镁、0.1毫克锌、0.1毫克铜、0.1毫克锰、0.1毫克硒、0.1毫克铬。

5. 纤维汉堡中的纤维主要来源于蔬菜。

以牛肉汉堡为例,每100克牛肉汉堡含有约1克纤维。

纤维有助于促进肠道蠕动,预防便秘。

二、汉堡的营养评价1. 能量密度以牛肉汉堡为例,每100克汉堡含有约280千卡能量。

相对于其他快餐食品,汉堡的能量密度较高,过量摄入容易导致能量过剩。

2. 蛋白质质量汉堡中的蛋白质质量较好,易于人体消化吸收。

但应注意,部分汉堡调料中的蛋白质质量较差,如炸鸡汉堡中的蛋白质主要来自鸡肉皮。

3. 脂肪质量汉堡中的脂肪主要来自饱和脂肪酸,过量摄入会增加心血管疾病风险。

部分汉堡调料中的脂肪质量较差,如炸鸡汉堡中的脂肪主要来自鸡肉皮。