多恩布什《宏观经济学》第10版课后习题详解(13-17章)【圣才出品】

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:9.12 MB

- 文档页数:123

第13章国际联系一、名词解释1.实际汇率(东北财大2017研;上海大学2017研;浙江理工大学2015研;武汉大学2014研;南京财经大学2010研;山东大学2007研)答:汇率有名义汇率与实际汇率之分。

名义汇率是两种货币的交换比率,它是指1单位外币能够交换的本币数量,或1单位本币能交换的外币数量。

实际汇率是两国产品的相对价格,是以同一货币衡量的本国与外国物价之比,它反映一国商品在国际市场上的竞争力。

如果持有外币只是为了购买外国产品,本币与外币的交换比率取决于各自的购买力,即取决于物价水平的倒数。

由此可得实际汇率的表达式为:ε=e×P/P f。

其中,ε表示实际汇率;P和P f分别为国内与国外的价格水平;e为名义汇率(采用的是直接标价法)。

可见,如果购买力平价成立,实际汇率应等于1。

根据这一定义式,实际汇率低,本国产品就相对便宜,本国产品在国际市场竞争力强,有利于增加本国净出口;反之,本国产品就相对昂贵。

2.购买力平价(中央财大2018、2014、2009研;北师大2015研;厦门大学2013研;中南财大2013研)答:购买力平价指一种传统的,但在实际中不太成立的汇率决定理论。

它认为货币如果在各国国内具有相等的购买力,那么这时的汇率就是均衡汇率。

如果2美元和1英镑在各自的国内可以购买等量的货物,则2美元兑换1英镑便存在购买力平价。

购买力平价理论的思想基础是,如果一国的货物相对便宜,那么人们就会购买该国货币并在那里购买商品。

购买力平价成立的前提是一价定律,即同一商品在不同国家的价格是相同的。

此外,购买力平价成立还需要一些其他的条件:①经济的变动来自货币方面;②价格水平与货币供给量成正比;③国内相对价格结构比较稳定;④经济中如技术、消费倾向等实际因素不变,也不对经济结构产生实质影响。

购买力平价存在两种形式:①绝对购买力平价,即两国货币的兑换比率等于两国价格水平的比率;②相对购买力平价,指两国货币兑换比率的变动,等于两国价格水平变动的差额。

宏观经济学多恩布什第10版教材下载及考研视频网课多恩布什《宏观经济学》(第10版)网授精讲班【教材精讲+考研真题串讲】目录多恩布什《宏观经济学》(第10版)网授精讲班【郑炳老师讲授的完整课程】【共41课时】多恩布什《宏观经济学(第10版)》网授精讲班【王志伟老师讲授的部分课程】【共28课时】电子书(题库)•多恩布什《宏观经济学》(第10版)【教材精讲+考研真题解析】讲义与视频课程【39小时高清视频】•多恩布什《宏观经济学》(第10版)笔记和课后习题详解•试看部分内容导论与国民收入核算第1章导论1.1 复习笔记1宏观经济学宏观经济学主要讨论总体经济的运行,具体包括:经济增长问题——收入、就业机会的变化;经济波动问题——失业问题,通货膨胀问题;经济政策——政府能否、以及如何干预经济,改善经济的运行。

2.微观经济学与宏观经济学的关系(1)二者的联系第一,微观经济学和宏观经济学互为补充。

微观经济学是在资源总量既定的条件下,通过研究个体经济活动参与者的经济行为及其后果来说明市场机制如何实现各种资源的最优配置;宏观经济学则是在资源配置方式既定的条件下研究经济中各有关总量的决定及其变化。

第二,微观经济学是宏观经济学的基础。

这是因为任何总体总是由个体组成的,对总体行为的分析自然也离不开个体行为的分析。

第三,微观经济学和宏观经济学都采用了供求均衡分析的方法。

微观经济学通过需求曲线和供给曲线决定产品的均衡价格和产量,宏观经济学通过总需求曲线和总供给曲线研究社会的一般价格水平和产出水平。

(2)二者的区别第一,研究对象不同。

微观经济学研究的是个体经济活动参与者的行为及其后果,侧重讨论市场机制下各种资源的最优配置问题,而宏观经济学研究的是社会总体的经济行为及其后果,侧重讨论经济社会资源的充分利用问题。

第二,中心理论不同。

微观经济学的中心理论是价格理论,宏观经济学的中心理论是国民收入决定论。

第三,研究方法不同。

微观经济学的研究方法是个量分析,宏观经济学的研究方法是总量分析。

宏观经济学第二章概念题1.如果政府雇用失业工人,他们曾领取TR美元的失业救济金,现在他们作为政府雇员支取TR美元,不做任何工作,GDP会发生什么情况?请解释。

答:国内生产总值指一个国家(地区)领土范围,本国(地区)居民和外国居民在一定时期内所生产和提供的最终使用的产品和劳务的价值。

用支出法计算的国内生产总值等于消费C、投资I、政府支出G和净出口NX之和。

从支出法核算角度看:C、I、NX保持不变,由于转移支付TR美元变成了政府对劳务的购买即政府支出增加,使得G增加了TR美元,GDP会由于G的增加而增加。

2.GDP和GNP有什么区别?用于计算收入/产量是否一个比另一个更好呢?为什么?答:(1)GNP和GDP的区别GNP指在一定时期内一国或地区的国民所拥有的生产要素所生产的全部最终产品(物品和劳务)的市场价值的总和。

它是本国国民生产的最终产品市场价值的总和,是一个国民概念,即无论劳动力和其他生产要素处于国内还是国外,只要本国国民生产的产品和劳务的价值都记入国民生产总值。

GDP指一定时期内一国或地区所拥有的生产要素所生产的全部最终产品(物品和劳务)的市场价值的总和。

它是一国范围内生产的最终产品,是一个地域概念。

两者的区别:在经济封闭的国家或地区,国民生产总值等于国内生产总值;在经济开放的国家或地区,国民生产总值等于国内生产总值加上国外净要素收入。

两者的关系可以表示为:GNP=GDP+[本国生产要素在其他国家获得的收入(投资利润、劳务收入)-外国生产要素从本国获得的收入]。

(2)使用GDP比使用GNP用于计量产出会更好一些,原因如下:1)从精确度角度看,GDP的精确度高;2)GDP衡量综合国力时,比GNP好;3)相对于GNP而言,GDP是对经济中就业潜力的一个较好的衡量指标。

由于美国经济中GDP和GNP的差异非常小,所以在分析美国经济时,使用这两种的任何一个指标,造成的差异都不会大。

但对于其他有些国家的经济来说明,这个差别是相当大的,因此,使用GDP作为衡量指标会更好。

第4篇行为的基础第13章消费与储蓄一、概念题1.巴罗—李嘉图等价定理(李嘉图等价)(Barro ricardo equivalence proposition(ricardian equivalence))答:李嘉图等价定理是英国经济学家李嘉图提出,并由新古典主义学者巴罗根据理性预期重新进行论述的一种理论。

该理论认为,在政府支出一定的情况下,政府采取征税或发行公债来为政府筹措资金,其效应是相同的。

李嘉图等价理论的思路是:假设政府预算在初始时是平衡的。

政府实行减税以图增加私人部门和公众的支出,扩大总需求,但减税导致财政赤字。

如果政府发行债券来弥补财政赤字,由于在未来某个时点,政府将不得不增加税收,以便支付债务和积累的利息。

具有前瞻性的消费者知道,政府今天借债意味着未来更高的税收。

用政府债务融资的减税并没有减少税收负担,它仅仅是重新安排税收的时间。

因此,这种政策不会鼓励消费者更多支出。

根据这一定理,政府因减税措施而增发的公债会被人们作为未来潜在的税收考虑到整个预算约束中去,在不存在流动性约束的情况下,公债和潜在税收的现值是相等的。

这样,变化前后两种预算约束本质上是一致的,从而不会影响人们的消费和投资。

李嘉图等价定理反击了凯恩斯主义所提出的公债是非中性的,即对宏观经济是有益处的观点。

但实际上,该定理成立前提条件太苛刻,现实经济很难满足。

2.政府储蓄(government saving)答:政府储蓄亦称“公共储蓄”,指财政收入与财政支出的差额。

若财政收入大于财政支出,就称财政盈余为正储蓄,如果财政收入小于财政支出,就称财政赤字为负储蓄,但一般说政府储蓄时指的是正储蓄。

政府储蓄可以通过增收、节支的手段来实现,但从目前大多数国家情况看,节支与增收均较困难,财政多呈现赤字,政府没有储蓄,反而需发行国债借老百姓的钱弥补财政赤字。

3.缺乏远见(myopia )答:缺乏远见指家庭关于未来收入流的短视眼光,不能正确认识到未来的真正收入。

宏观经济学第十七章习题答案宏观经济学第十七章--习题答案第十七章总需求―总供给模型7.设总供给函数为ys=2000+p,总需求函数为yd=2400-p:(1)谋供需均衡点。

(2)如果总需求曲线向左(平行)移动10%,求新的均衡点并把该点与(1)的结果相比较。

(3)如果总需求曲线向右(平行)移动10%,求新的均衡点并把该点与(1)的结果相比较。

(4)如果总供给曲线向左(平行)移动10%,求新的均衡点并把该点与(1)的结果相比较。

(5)本题的总供给曲线具有何种形状?属于何种类型?解答:(1)由ys=yd,得2000+p=2400-p于是p=200,yd=ys=2200,即得供求均衡点。

(2)向左平移10%后的总需求方程为yd=2160-p于是,由ys=yd有2000+p=2160-pp=80ys=yd=2080与(1)较之,代莱平衡整体表现出来经济处在不景气状态。

(3)向右位移10%后的总需求方程为yd=2640-p于是,由ys=yd存有2000+p=2640-pp=320ys=yd=2320与(1)相比,新的均衡表现出经济处于高涨状态。

(4)向左平移10%的总供给方程为ys=1800+p于是,由ys=yd有1800+p=2400-pp=300ys=yd=2100与(1)较之,代莱平衡整体表现出来经济处在通缩状态。

(5)总供给曲线是向右上方倾斜的直线,属于常规型。

8.引致总需求曲线和总供给曲线变动的因素主要存有哪些?答疑:引致总需求曲线变动的因素主要存有:(1)家庭消费市场需求的变化;(2)企业投资市场需求的变化;(3)政府购买和税收的变化;(4)净出口的变化;(5)货币供给的变化。

引致总供给曲线变动的因素主要存有:(1)自然灾害和战争;(2)技术变化;(3)进口商品价格的变化;(4)工资水平的变化;(5)对价格水平的预期。

9.设立某一三部门的经济中,消费函数为c=200+0.75y,投资函数为i=200-25r,货币市场需求函数为l=y-100r,名义货币供给就是1000,政府出售g=50,求该经济的总需求函数。

第5篇重大事件、国际调整和前沿课题第19章重大事件:萧条经济学、恶性通货膨胀和赤字一、简答题1.恶性通货膨胀对宏观经济运行效率将产生哪些不利影响?答:恶性通货膨胀对宏观经济运行效率产生的不利影响主要包括:(1)恶性通货膨胀使价格信号扭曲,使厂商无法根据价格提供的信号来决策,造成经济活动的低效率。

(2)恶性通货膨胀使厂商必须经常性地改变其产品或服务的价格,产生因价格改变而发生的菜单成本。

(3)恶性通货膨胀使不确定性提高,引发资源配置向通货膨胀预期有利的领域倾斜,不利于经济的长期稳定发展。

(4)恶性通货膨胀降低人们的货币需求,这会使往返银行的次数增多,以至于磨掉鞋底,经济学上这种成本被称为“鞋底成本”。

2.为什么通货膨胀有通货膨胀税的说法?它与铸币税是一回事吗?答:(1)如果货币供给的增加触发物价上涨,导致通货膨胀,由于通货膨胀的再分配效应,势必削弱社会公众手中所持有货币的购买力,引起一部分货币购买力从社会公众向货币发行者转移,这种转移犹如一种赋税,因而被称为通货膨胀税。

(2)铸币税指的是政府凭借对货币发行权的垄断而获得的对一部分社会资源的索取权,铸币税的数额等于所发行的货币面值与其实际发行成本之间的差额,实际发行成本主要包括纸张成本及印制费等。

通货膨胀税与铸币税不是一回事,只要政府发行的货币面值与发行成本之间存在差额,则必定存在铸币税;但如果所发行的货币恰好为经济活动所需要,没有相应出现通货膨胀,则就不存在通货膨胀税;只有在过度发行货币引致通货膨胀的时候,才会存在通货膨胀税。

3.预算赤字是个问题吗?为什么是?或者为什么不是?答:预算赤字是在编制预算时支出大于收入的差额,是计划安排的赤字。

预算赤字是个问题。

原因分析如下:(1)在短期,扩张性财政政策引起的赤字增加会刺激总需求,使产出增加。

但同时利率上升会挤出私人消费和投资,而资本积累的降低意味着未来经济增长的乏力。

(2)在开放经济中,预算赤字增加会提高利率,吸引国外资金流入并使本币升值,削弱了本国商品的竞争力,使国际收支的经常项目恶化。

CHAPTER 10MONEY, INTEREST, AND INCOMEAnswers to Problems in the Textbook:Conceptual Problems:1. The model in Chapter 9 assumed that both the price level and the interest rate were fixed. But the IS-LM model lets the interest rate fluctuate and determines the combination of output demanded and the interest rate for a fixed price level. It should be noted that while the upward-sloping AD-curve in Chapter 9 (the [C+I+G+NX]-line in the Keynesian cross diagram) assumed that interest rates and prices were fixed, the downward-sloping AD-curve that is derived at the end of Chapter 10 from the IS-LM model lets the price level fluctuate and describes all combinations of the price level and the level of output demanded at which the goods and money sector simultaneously are in equilibrium. 2.a. If the expenditure multiplier (α) becomes larger, the increase in equilibrium income caused by a unitchange in intended spending also becomes larger. Assume investment spending increases due to a change in the interest rate. If the multiplier α becomes larger, any increase in spending will cause a larger increase in equilibrium income. This means that the IS-curve will become flatter as the size of the expenditure multiplier becomes larger.If aggregate demand becomes more sensitive to interest rates, any change in the interest rate causes the [C+I+G+NX]-line to shift up by a larger amount and, given a certain size of the expenditure multiplier α, this will increase equilibrium income by a larger amount. As a result, the IS-curve will become flatter.2.b. Monetary policy changes affect interest rates and this leads to a change in intended spending, whichis reflected in a change in income. In 2.a. it was explained that a steep IS-curve means either that the multiplier α is small or that desired spending is not very interest sensitive. Therefore, an increase in money supply will reduce interest rates. However, this does not result in a large increase in aggregate demand if spending is very interest insensitive. Similarly, if the multiplier is small, then any change in spending will not affect output significantly. Therefore, the steeper the IS-curve, the weaker the effect of monetary policy changes on equilibrium output.3. Assume that money supply is fixed. Any increase in income will increase money demand and theresulting excess demand for money will drive the interest rate up. This, in turn, will reduce the quantity of money balances demanded to bring the money sector back to equilibrium. But if money demand is very interest insensitive, then a larger increase in the interest rate is needed to reach a new equilibrium in the money sector. As a result, the LM-curve becomes steeper.Along the LM-curve, an increase in the interest rate is always associated with an increase in income. This means that an increase in money demand (due to an increase in income) has to be offset by a decrease in the quantity of money demanded (due to an increase in the interest rate) to keep the money sector in equilibrium. But if money demand becomes more income sensitive, a smaller change in income is required for any specific change in the interest rate to keep the money sector in equilibrium. Therefore, the LM-curve becomes steeper as money demand becomes more income sensitive.4.a. A horizontal LM-curve implies that the public is willing to hold whatever money is supplied at anygiven interest rate. Therefore, changes in income will not affect the equilibrium interest rate in the money sector. But if the interest rate is fixed, we are back to the analysis of the simple Keynesian model used in Chapter 9. In other words, there is no offsetting effect (or crowding-out effect) to fiscal policy.14.b. A horizontal LM-curve implies that changes in income do not affect interest rates in the money sector.Therefore, if expansionary fiscal policy is implemented, the IS-curve shifts to the right, but the level of investment spending is no longer negatively affected by rising interest rates, that is, there is no crowding-out effect. In terms of Figure 10-3, the interest rate not longer serves as the link between the goods and assets markets.4.c. A horizontal LM-curve results if the public is willing to hold whatever money balances are suppliedat a given interest rate. This situation is called the liquidity trap. Similarly, if the Fed is prepared to peg the interest rate at a certain level, then any change in income will be accompanied by an appropriate change in money supply. This will lead to continuous shifts in the LM-curve, which is equivalent to having a horizontal LM-curve, since the interest rate will never change.5. From the material presented in the text we know that when intended spending becomes more interestsensitive, then the IS-curve becomes flatter. Now assume that an increase in the interest rate stimulates saving and therefore reduces the level of consumption. This means that now not only investment spending but also consumption is negatively affected by an increase in the interest rate. In other words, the [C+I+G+NX]-line in the Keynesian cross diagram will now shift down further than previously and the level of equilibrium income will decrease more than before. In other words, the IS-curve has become flatter.This can also be shown algebraically, since we can now write the consumption function as follows:C = C* + cYD - giIn a simple model of the expenditure sector without income taxes, the equation for aggregate demand will now beAD = A o + cY - (b + g)i.From Y = AD ==> Y = [1/(1 - c)][A o - (b + g)i] ==>i = [1/(b + g)]A o - [(1 - c)/(b + g)]YTherefore, the slope of the IS-curve has been reduced from (1 - c)/b to (1 - c)/(b + g).6. In the IS-LM model, a simultaneous decline in interest rates and income can only be caused by a shiftof the IS-curve to the left. This shift in the IS-curve could have been caused by a decrease in private spending due to negative business expectations or a decline in consumer confidence. In 1991, the economy was in a recession and firms did not want to invest in new machinery and, since consumer confidence was very low, people were not expected to increase their level of spending. In the IS-LM diagram the adjustment process can be described as follows:I o↓ ==> Y ↓ (the IS-curve shifts left) ==> m d↓ ==> i ↓ ==> I ↑ ==> Y ↑. Effect: Y ↓ and i ↓ .2ii1i221Technical Problems:1.a. Each point on the IS-curve represents an equilibrium in the expenditure sector. Therefore the IS-curvecan be derived by settingY = C + I + G = (0.8)[1 - (0.25)]Y + 900 - 50i + 800 = 1,700 + (0.6)Y - 50i ==>(0.4)Y = 1,700 - 50i ==> Y = (2.5)(1,700 - 50i) ==> Y = 4,250 - 125i.1.b. The IS-curve shows all combinations of the interest rate and the level of output such that theexpenditure sector (the goods market) is in equilibrium, that is, intended spending is equal to actual output. A decrease in the interest rate stimulates investment spending, making intended spending greater than actual output. The resulting unintended inventory decrease leads firms to increase their production to the point where actual output is again equal to intended spending. This means that the IS-curve is downward sloping.1.c. Each point on the LM-curve represents an equilibrium in the money sector. Therefore the LM-curvecan be derived by setting real money supply equal to real money demand, that is,M/P = L ==> 500 = (0.25)Y - 62.5i ==> Y = 4(500 + 62.5i) ==> Y = 2,000 + 250i.1.d. The LM-curve shows all combinations of the interest rate and level of output such that the moneysector is in equilibrium, that is, the demand for real money balances is equal to the supply of real money balances. An increase in income will increase the demand for real money balances. Given a fixed real money supply, this will lead to an increase in interest rates, which will then reduce the quantity of real money balances demanded until the money market clears. In other words, the LM-curve is upward sloping.1.e. The level of income (Y) and the interest rate (i) at the equilibrium are determined by the intersectionof the IS-curve with the LM-curve. At this point, the expenditure sector and the money sector are both in equilibrium simultaneously.From IS = LM ==> 4,250 - 125i = 2,000 + 250i ==> 2,250 = 375I ==> i = 6==> Y = 4,250 - 125*6 = 4,250 - 750 ==> Y = 3,500Check: Y = 2,000 + 250*6 = 2,000 + 1,500 = 3,5003i125 ISLM62,000 3,500 4,250 Y2.a. As we have seen in 1.a., the value of the expenditure multiplier is α= 2.5. This multiplier αisderived in the same way as in Chapter 9. But now intended spending also depends on the interest rate, so we no longer have Y = αA o, but ratherY = α(A o - bi) = (1/[1 - c + ct])(A o - bi) ==> Y = (2.5)(1,700 - 50i) = 4,250 - 125i.2.b.This can be answered most easily with a numerical example. Assume that government purchasesincrease by ∆G = 300. The IS-curve shifts parallel to the right by==> ∆IS = (2.5)(300) = 750.Therefore IS': Y = 5,000 - 125iFrom IS' = LM ==> 5,000 - 125i = 2,000 + 250i ==> 375i = 3,000 ==> i = 8==> Y = 2,000 + 250*8 ==> Y = 4,000 ==> ∆Y = 500When interest rates are assumed to be constant, the size of the multiplier is equal to α = 2.5, that is, (∆Y)/(∆G) = 750/300 = 2.5. But when interest rates are allowed to vary, the size of the multiplier is reduced to α1 = (∆Y)/(∆G) = 500/300 = 1.67.2.c. Since an increase in government purchases by ∆G = 300 causes a change in the interest rate of 2percentage points, government spending has to change by ∆G = 150 to increase the interest rate by 1 percentage point.2.d. The simple multiplier α in 2.a. shows the magnitude of the horizontal shift in the IS-curve, given achange in autonomous spending by one unit. But an increase in income increases money demand and the interest rate. The increase in the interest rate crowds out some investment spending and this has a dampening effect on income. The multiplier effect in 2.b. is therefore smaller than the multiplier effect in 2.a.3.a. An increase in the income tax rate (t) will reduce the size of the expenditure multiplier (α). But as themultiplier becomes smaller, the IS-curve becomes steeper. As we can see from the equation for the IS-curve, this is not a parallel shift but rather a rotation around the vertical intercept.Y = α(A o - bi) = [1/(1 - c + ct)](A o - bi) ==> i = (1/b)A o - (α/b)Y = (1/b)A o - (1/b)[1 - c + ct]Y 3.b. If the IS-curve shifts to the left and becomes steeper, the equilibrium income level will decrease. Ahigher tax rate reduces private spending and this will lower national income.3.c. When the income tax rate is increased, the equilibrium interest rate will also decrease. The adjustmentto the new equilibrium can be expressed as follows (see graph on the next page):t up ==> C down ==> Y down ==> m d down ==> i down ==> I up ==> Y up. Effect: Y ↓ and i ↓45i 1i 2214.a. If money demand is less interest sensitive, then the LM-curve is steeper and monetary policy changesaffect equilibrium income to a larger degree. If money supply is assumed to be fixed, the adjustment to a new equilibrium in the money sector has to come solely through changes in money demand. If money demand is less interest sensitive, any increase in money supply requires a larger increase in income and a larger decrease in the interest rate in order to bring the money sector into a new equilibrium.i ii 1 i 1 2 2i 20 120 12The adjustment process in each of the two diagrams is the same; however, in the case of a more interest-sensitive money demand (a flatter LM-curve), the change in Y and i will be smaller.(M/P) up ==> i down ==> I up ==> Y up ==> m d up ==> i up Effect: Y ↑ and i ↓Section 10-5 derives the equation for the LM-curve and the equation for the monetary policy multiplier asi = (1/h)[kY - (M/P)] and (∆Y)/∆(M/P) = (b/h)γrespectively. If money demand becomes more interest sensitive, the value of h becomes larger and the slope of the LM-curve becomes flatter, while the size of the monetary policy multiplier becomes smaller.4.b. An increase in money supply drives interest rates down. This decrease in interest rates will stimulateintended spending and thus income. If money demand becomes less interest sensitive, a larger increase in income is required to bring the money sector into equilibrium. But this implies that the overall decrease in the interest rate has to be larger, given that the interest sensitivity of spending has not changed.5. The price adjustment, that is, the movement along the AD-curve, can be explained in the followingway: With nominal money supply (M) fixed, real money balances (M/P) will decrease as the price level (P) increases. There is an excess demand for money and interest rates will rise. This will lead toa decrease in investment spending and thus the level of output demanded will decrease. In otherwords, the LM-curve will shift to the left as real money balances decrease.6. In the classical case, the AS-curve is vertical. Therefore, any increase in aggregate demand due toexpansionary monetary policy will, in the long run, not lead to any increase in output but simply lead to an increase in the price level. An increase in money supply will first shift the LM-curve to the right.This implies a shift of the AD-curve to the right. Therefore we have excess demand for goods and services and prices will begin to rise. But as the price level rises, real money balances will begin to fall again, eventually returning to their original level. Therefore, the shift of the LM-curve to the right due to the expansionary monetary policy and the resulting shift of the AD-curve will be exactly offset by a shift of the LM-curve to the left and a movement along the AD-curve to the new long-run equilibrium due to the price adjustment. At this new long-run equilibrium, the level of output and interest rates will not have changed while the price level will have changed proportionally to the nominal money supply, leaving real money balances unchanged. In other words, money is neutral in the long run (the classical case).7.a. An increase in the demand for money will shift the LM-curve to the left, raising the interest rate andlowering the level of output demanded. As a result, the AD-curve will also shift to the left. In the Keynesian case, the price level is assumed to be fixed, that is, the AS-curve is horizontal. In this case, the decrease in income in the AD-AS diagram is equivalent to the decrease in income in the IS-LM diagram, since there is no price adjustment, that is, the real balance effect does not come into play. 7.b. An increase in the demand for money will shift the LM-curve to the left, raising the interest rate andlowering the level of output demanded. As a result, the AD-curve will also shift to the left. In the classical case, the level of output will not change, since the AS-curve is vertical. In this case, the shift in the AD-curve will simply be reflected in a price decrease, but the level of output will remain unchanged. The real balance effect causes the LM-curve to shift back to its original level, since the price decrease causes an increase in real money balances.Additional Problems:1. True or false? Explain your answer.“A decrease in the marginal propensity to save implies tha t the IS-curve will become steeper.”False A decrease in the marginal propensity to save (s = 1 - c) is equivalent to an increase in the marginal propensity to consume (c), which, in turn, implies an increase in the expenditure multiplier ( ). But with a larger expenditure multiplier, any increase in investment spending due to a decrease in the interest rate will lead to a larger increase in income. Therefore the IS-curve will become flatter and not steeper.2. True or false? Explain your answer.“If the c entral bank keeps the supply of money constant, then the money supply curve is vertical, which implies a vertical LM-curve.”6False. Equilibrium in the money sector implies that real money supply is equal to real money demand, that is,m s = M/P = m d(i,Y).This implies that any increase in income (Y) will increase the demand for money. To bring the money sector back into equilibrium, interest rates (i) have to rise simultaneously to bring the quantity of money demanded back to the original level (equal to the fixed supply of money). Therefore, to keep the money sector in equilibrium, an increase in income must always be associated with an increase in the interest rate and the LM-curve must be upward sloping.3. "Restrictive monetary policy reduces consumption and investment." Comment on thisstatement.A reduction in money supply raises interest rates, which will, in turn, have a negative effect on the level of investment spending. The level of consumption may also decrease as it becomes more costly to finance expenditures by borrowing money. But even if it is assumed that consumption is not affected by changes in the interest rate, consumption will still decrease since restrictive monetary policy will reduce national income and therefore private spending.4. "If government spending is increased, money demand will increase." Comment.A change in government spending directly affects the expenditure sector and therefore the IS-curve. But in an IS-LM framework, the money sector is also affected indirectly. An increase in the level of government spending will shift the IS-curve to the right, leading to an increase in income. But the increase in income will lead to an increase in money demand, so the interest rate will have to increase in order to lower the quantity of money demanded and to bring the money sector back into equilibrium. Overall no change in money demand can occur, since equilibrium in the money sector requires that m s = M/P = m d, that is, money supply has to be equal to money demand, and money supply is assumed to be fixed.5. "An increase in autonomous investment reduces the interest rate and therefore the moneysector will no longer be in equilibrium." Comment on this statement.An increase in autonomous investment shifts the IS-curve to the right. The increase in income leads to an increase in the demand for money, which means that interest rates increase. The increase in interest rates then reduces the quantity of money demanded again to bring the money market back to equilibrium.6. "A monetary expansion leaves the budget surplus unaffected." Comment on this statement. Expansionary monetary policy, that is, an increase in money supply, will lower interest rates (the LM-curve will shift to the right). Lower interest rates will lead to an increase in investment spending and the economy will therefore be stimulated. But a higher level of national income increases the government’s tax revenues and therefore the budget surplus will increase.7. "Restrictive monetary policy implies lower tax revenues and therefore to an increase in thebudget deficit." Comment on this statement.A decrease in money supply will shift the LM-curve to the left. This will lead to an increase in the interest rate, which will lead to a reduction in spending and thus national income. But as income decreases, so does income tax revenue. Therefore, the budget deficit will increase because of the change in its cyclical component.78. “If the demand for money becomes more sensitive to changes in income, then the LM-curvebecome s flatter.” Comment on this statement.Along the LM-curve, an increase in the interest rate is always associated with an increase in income. This means that an increase in money demand (due to an increase in income) has to be offset by a decrease in the quantity of money demanded (due to an increase in the interest rate) to keep the money sector in equilibrium. But if money demand becomes more income sensitive, a smaller change in income is required for any specific change in the interest rate to keep the money sector in equilibrium. Therefore, the LM-curve becomes steeper (and not flatter) as money demand becomes more sensitive to changes in income.9. “A decrease in the income tax rate will increase the demand for money, shifting the LM-curveto the righ t.” Comment on this statement.A decrease in the income tax rate (t) will increase the expenditure multiplier (α). But with a larger expenditure multiplier, any increase in investment spending due to a decrease in the interest rate will lead to a larger increase in income. Since fiscal policy affects the expenditure sector, the IS-curve (not the LM-curve) will shift. The IS-curve will become flatter and shift to the right. This will lead to a new equilibrium at a higher level of income (Y) and a higher interest rate (i). But money supply is fixed and the LM-curve remains unaffected by fiscal policy. Therefore, at the new equilibrium (the intersection of the new IS-curve with the old LM-curve) the demand for money will not have changed, since the money sector has to be in an equilibrium at m s = m d(i,Y).10. “If the demand for money becomes more insensitive to changes in the interest rate, equilibriumin the money sector will have to be restored mostly through changes in income. This implies a flat LM-curve.” Comment on this statement.Any increase in income will increase money demand and this will drive the interest rate up. Therefore, the quantity of money balances demanded will decline again until the money sector is back in equilibrium. But if money demand is very interest insensitive, then a larger increase in the interest rate is needed to reach a new equilibrium in the money sector. This means that the LM-curve is steep and not flat.11. Assume the following IS-LM model:Expenditure Sector Money SectorSp = C + I + G + NX M = 700C = 100 + (4/5)YD P = 2YD = Y - TA m d = (1/3)Y + 200 - 10iTA = (1/4)YI = 300 - 20iG = 120NX = -20(a) Derive the equilibrium values of consumption (C) and money demand (m d).(b) How much of investment (I) will be crowded out if the government increases its purchasesby ∆G = 160 and nominal money supply (M) remains unchanged?(c) By how much will the equilibrium level of income (Y) and the interest rate (i) change, ifnominal money supply is also increased to M' = 1,100?a. Sp = 100 + (4/5)[Y - (1/4)Y] + 300 - 20i + 120 - 20 = 500 + (4/5)(3/4)Y – 20i = 500 + (3/5)Y - 20iFrom Y = Sp ==> Y = 500 + (3/5)Y - 20i ==> (2/5)Y = 500 - 20i==> Y = (2.5)(500 - 20i) ==> Y = 1,250 - 50i IS-curveFrom M/P = m d ==> 700/2 = (1/3)Y + 200 - 10i ==> (1/3)Y = 150 + 10i==> Y = 3(150 + 10i) ==> Y = 450 + 30i LM-curve89IS = LM ==> 1,250 - 50i = 450 + 30i ==> 800 = 80i ==> i = 10==> Y = 1,250 - 50*10 ==> Y = 750C = 100 + (4/5)(3/4)750 = 100 + (3/5)750 ==> C = 550m s = M/P = 700/2 = 350 = m dCheck: m d = (1/3)750 + 200 - 10*10 = 350i25 IS o LM o10450 750 1,250 Yb. ∆IS = (2.5)160 = 400 ==> IS' = 1,650 - 50iIS' = LM ==> 1,650 - 50i = 450 + 30i ==> 1,200 = 80i ==> i = 15==> Y = 1,650 - 50*15 ==> Y = 900Since ∆i = + 5 ==> ∆I = - 20*5 ==> ∆I = - 100Check: ∆ 331510450 750 900 1,250 1,650 Yc. From M'/P = m d ==> 1,100/2 = (1/3)Y + 200 - 20i==> (1/3)Y = 350 - 20i ==> Y = 3(350 - 20i) ==> Y = 1,050 + 30iIS 1 = LM 1 ==> 1,650 - 50i = 1,050 + 30i ==> 600 = 80i ==> i = 7.5==> Y = 1,650 - 50(7.5) = 1,275.==> ∆i = - 7.5 and ∆Y = 375 as compared to (b).i1107.512. Assume the money sector can be described by these equations: M/P = 400 and m d = (1/4)Y - 10i.In the expenditure sector only investment spending (I) is affected by the interest rate (i), and the equation of the IS-curve is: Y = 2,000 - 40i.(a) If the size of the expenditure multiplier is α= 2, show the effect of an increase ingovernment purchases by ∆G = 200 on income and the interest rate.(b) Can you determine how much of investment is crowded out as a result of this increase ingovernment spending?(c)If the money demand equation were changed to m d = (1/4)Y, how would your answers in (a)and (b) change?a. From M/P = m d ==> 400 = (1/4)Y - 10i ==> Y = 1,600 + 40i LM-curveFrom IS = LM ==> 2,000 - 40i = 1,600 + 40i ==> 80i = 400 ==> i = 5==> Y = 2,000 - 40*5 ==> Y = 1,800∆IS = 2*200 = 400 ==> IS' = 2,400 - 40iIS' = LM ==> 2,400 - 40i = 1,600 + 40i ==> 80i = 800 ==> i = 10==> Y = 1,600 + 40*10 ==> Y = 2,000Therefore ∆i = + 5 and ∆Y = + 200b.Since the size of the expenditure multiplier is α = 2 but income only goes up by αY = 200, the fiscalpolicy multiplier in the IS-LM model is α1= 1. But this means that the level of investment has been reduced by 100, that is, ∆I = -100. This can be seen by restating the IS-curve as follows:Y = 2,000 - 40i = Y = 2(1,000 - 20i)Since government purchases are changed by ∆G = 200 ==> Y = 2(1,200 - 20i), which means that the IS-curve shifts by ∆IS = 2*200 = 400. But the increase in income is actually only ∆Y = 200. This implies that investment changes by ∆I = -100. Investment is of the form I = I o– 20i; however, since the interest rate went up by ∆i = 5, investment changes by ∆I = - 20*5 = - 100.From ∆Y = α(∆Sp) ==> 200 = 2(∆Sp) ==> ∆Sp = 100But since ∆Sp =∆ G + ∆I ==> 100 = 200 + ∆I ==> ∆I = - 100c. If m d= (1/4)Y, then we have the classical case, that is, a vertical LM-curve. In this case, fiscalexpansion will not change income at all. This occurs since the increase in G will be offset by a decrease in I of equal magnitude due to an increase in the interest rate.(M/P) = m d ==> 400 = (1/4)Y ==> Y = 1,600 LM-curveIS = LM ==> 2,000 - 40i = 1,600 ==> 40i = 400 ==> i = 10 ==> Y = 1,600IS' = LM ==> 2,400 - 40i = 1,600 ==> 40i = 800==> i = 20 ==> Y = 1,600 ==> ∆I = - 2001013. Assume money demand (md) and money supply (ms) are defined as: md = (1/4)Y + 400 - 15iand ms = 600, and intended spending is of the form: Sp = C + I + G + NX = 400 + (3/4)Y - 10i.Calculate the equilibrium levels of Y and i, and indicate by how much the Fed would have to change money supply to keep interest rates constant if the government increased its spending by ∆G = 50. Show your solutions graphically and mathematically.ms = md ==> 600 = (1/4)Y + 400 - 15i ==> (1/4)Y = 200 + 15i==> Y = 4(200 + 15i) ==> Y = 800 + 60i LM-curveY = C + I + G + NX ==> Y = 400 + (3/4)Y - 10i ==>(1/4)Y = 400 - 10i ==> Y = 4(400 - 10i) ==> Y = 1,600 - 40i IS-curveFrom IS = LM ==> 1,600 - 40i = 800 + 60i ==> 100i = 800 ==> i = 8 ==> Y = 1,280If government spending is increased by ∆G = 50, the IS-curve will shift to the right) by (∆IS) = 4*50 = 200. If the Fed wants to keep the interest rate constant, money supply has to be increased in a way that shifts the LM-curve to the right by exactly the same amount as the IS-curve, that is, (∆LM) = 200.From Y = 2(200 + 15i) ==> (∆Y) = 2(∆ms) ==> 200 = 2(∆ms)==> (∆ms) = 100, so money supply has to be increased by 100.Check: IS' = LM": 1,800 - 40i = 1,000 + 60i ==> 800 = 100i4018800 1000 1280 1480 1600 1800 Y14. Assume the equation for the IS-curve is Y = 1,200 – 40i, and the equation for the LM-curve isY = 400 + 40i.(a) Determine the equilibrium value of Y and i.(b) If this is a simple model without income taxes, by how much will these values change if thegovernment increases its expenditures by ∆G = 400, financed by an equal increase in lump sum taxes (∆TA o = 400)?a. From IS = LM ==> 1,200 - 40i = 400 + 40i ==>800 = 80i ==> i = 10 ==> Y = 400 + 40*10 ==> Y = 800b. According to the balanced budget theorem, the IS-curve will shift horizontally by the increase ingovernment purchases, that is, ∆IS = ∆G = ∆TA o = 400.Thus the new IS-curve is of the form: Y = 1,600 - 40i.From IS' = LM ==> 1,600 - 40i = 400 + 40i ==>1,200 = 80i ==> i = 15 ==> Y = 400 + 40*15 ==> Y = 1,00015. Assume you have the following information about a macro model:Expenditure sector: Money sector:11。

第17章政策17.1复习笔记一、政策作用的时滞1.政策时滞含义与分类当经济出现扰动,均衡国民收入偏离充分就业水平时,政策行动影响经济的过程,每一个阶段都存在时滞,这些时滞可以分成两种时间层次:内部时滞和外部时滞。

(1)内部时滞内部时滞指从经济发生变动,认识到有采取政策措施的必要性到决策者制定出适当的经济政策并付诸实施之间的时间间隔,是与“外部时滞”相对而言的。

内部时滞包括三个组成部分:认识时滞、决策时滞和行动时滞。

不同的经济政策具有不同的内部时滞。

政府要有效地影响经济运行,其制定和执行经济政策的内部时滞就必须尽可能地缩短。

但由于内部时滞受一系列客观因素的制约,故其变动不可能太大。

①认识时滞认识时滞指从一种潜在的不稳定的动乱情况发生时起到这种情况被政策制定者认识为止的一段时间,处于决策时滞和实施时滞之前。

如果政策制定者能准确地预测经济变动,并在这种变动发生之前采取相应政策,那么,认识时滞就小于零。

但在现实的经济生活中,认识时滞一般是正的。

认识时滞的长短取决于加工整理资料所需的时间和政策制定者对经济运行规律的把握程度。

②决策时滞决策时滞指对一个经济问题,特别是宏观经济问题,从认识到需要采取行动到实际做出决策之间的时间间隔,介于认识时滞和实施时滞之间。

决策时滞的长短取决于决策者的意见是否一致,立法程序是否复杂等。

一般而言,不同种类的经济政策的决策时滞是不同的:货币政策的决策时滞比较短;财政政策的决策时滞比较长。

③行动时滞行动时滞,也称实施时滞,指从做出决策到具体实施之间的时间间隔,处于认识时滞和决策时滞之后。

实施时滞的长短受经济管理当局的制度结构和运行效率的影响。

货币政策由中央银行决定和实施,因而实施时滞较短;财政政策由立法机构做出决定,再由财政部具体实施,因而实施时滞较长。

另外经济管理当局的行政效率也在很大程度上影响行动时滞。

(2)外部时滞外部时滞指从一项经济政策特别是宏观经济政策开始执行到其充分地发挥全部效果并达到预期目标之间的时间间隔,是与“内部时滞”相对而言的。

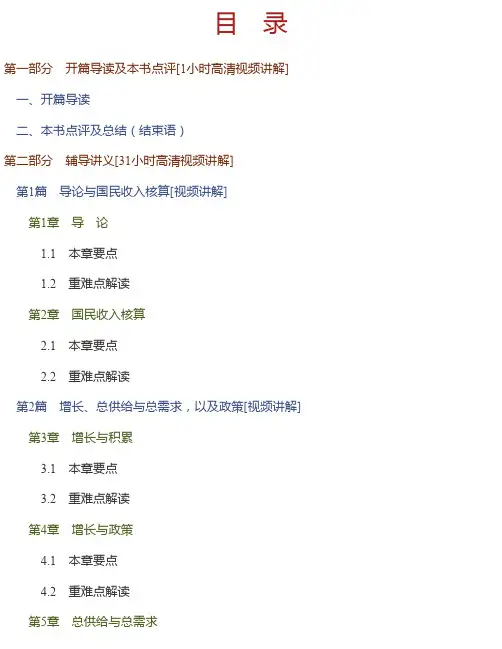

目 录第一部分 开篇导读及本书点评[1小时高清视频讲解]一、开篇导读二、本书点评及总结(结束语)第二部分 辅导讲义[31小时高清视频讲解]第1篇 导论与国民收入核算[视频讲解]第1章 导 论1.1 本章要点1.2 重难点解读第2章 国民收入核算2.1 本章要点2.2 重难点解读第2篇 增长、总供给与总需求,以及政策[视频讲解]第3章 增长与积累3.1 本章要点3.2 重难点解读第4章 增长与政策4.1 本章要点4.2 重难点解读第5章 总供给与总需求5.1 本章要点5.2 重难点解读第6章 总供给:工资、价格与失业6.1 本章要点6.2 重难点解读第7章 通货膨胀与失业的解剖7.1 本章要点7.2 重难点解读第8章 政策预览8.1 本章要点8.2 重难点解读第3篇 首要的几个模型[视频讲解]第9章 收入与支出9.1 本章要点9.2 重难点解读第10章 货币、利息与收入10.1 本章要点10.2 重难点解读第11章 货币政策与财政政策11.1 本章要点11.2 重难点解读第12章 国际联系12.1 本章要点12.2 重难点解读第4篇 行为的基础[视频讲解]第13章 消费与储蓄13.1 本章要点13.2 重难点解读第14章 投资支出14.1 本章要点14.2 重难点解读第15章 货币需求15.1 本章要点15.2 重难点解读第16章 联邦储备、货币与信用16.1 本章要点16.2 重难点解读第17章 政 策17.1 本章要点17.2 重难点解读第18章 金融市场与资产价格18.1 本章要点18.2 重难点解读第5篇 重大事件、国际调整和前沿课题[视频讲解]第19章 重大事件:萧条经济学、恶性通货膨胀和赤字19.1 本章要点19.2 重难点解读第20章 国际调整与相互依存20.1 本章要点20.2 重难点解读第21章 前沿课题21.1 本章要点21.2 重难点解读第三部分 名校考研真题名师精讲及点评[8小时高清视频讲解]一、名词解释二、简答题三、计算题四、论述题第一部分 开篇导读及本书点评[1小时高清视频讲解]一、开篇导读[0.5小时高清视频讲解]主讲老师:郑炳一、教材及教辅、课程、题库简介► 教材:多恩布什《宏观经济学》(第10版)(多恩布什、费希尔、斯塔兹著,王志伟译,中国人民大学出版社)► 教辅(两本,文库考研网主编,中国石化出版社出版)√网授精讲班【教材精讲+考研真题串讲】精讲教材章节内容,穿插经典考研真题,分析各章考点、重点和难点。

Chapter 13Solutions to the Problems in the Textbook:Conceptual Problems:1.a. According to the life-cycle theory of consumption, people try to maintain a fairly stable consumption pathover their lifetime. Individuals save during their working years so they can keep up the same consumption stream after they retire. This implies that wealth increases steadily until retirement while consumption remains stable. We should therefore expect the ratio of consumption to accumulated saving (wealth) to decrease over time up to retirement.1.b. After retirement, wealth is used up to finance consumption during the remaining years. Therefore the ratioof consumption to accumulated saving (wealth) increases again after retirement, eventually approaching 1.2.a. Suppose that you and your neighbor both work the same number of years until retirement and you bothhave the same annual income. If your neighbor is in bad health and does not expect to live as long as you do, she will expect to have fewer retirement years in which to use accumulated wealth to finance a steady consumption stream. Your neighbor's goal for retirement saving will not be as high as yours, and compared to you, she will have a higher level of consumption over her working years.Since planned annual consumption (C) is determined by the number of working years (WL), the number of years to live (NL), and income from labor (YL), we get the equation:C = [(WL)/(NL)](YL).WL and YL are the same for you and your neighbor, but NL is smaller for your neighbor. Therefore you will have a lower level of consumption (C).(Note: Students may come up with a variety of different answers. For one, your neighbor, who is in bad health, currently has much larger medical bills than you do. Therefore she may not be able to save as much for retirement, even if she might expect to live as long as you. On the other hand, she may not have large medical bills now, but expects them later, as she gets older. This may induce her to save more now.While such arguments are valid, instructors should point out that the answer should be related to the life-cycle theory.)2.b. If we assume for simplicity that the rate of return on Social Security is the same as the rate of return onprivate saving, then the introduction of a Social Security system based on a trust fund should not have any effect on your level of consumption. Social Security may be considered a form of "forced saving," since you are forced to pay Social Security taxes during your working years and will, in return, receive benefits during your retirement years. However, most likely you would have voluntarily saved as much as the government is now “forcing” you to save with levying a Social Security tax. Therefore your consumption behavior will not change. Still, the levying of a Social Security tax reduces disposable income during your working years, increasing the ratio of consumption to disposable income (the average propensity to consume). If private saving were simply replaced with government saving, national saving would not be affected.In reality, however, the Social Security system is not strictly financed through a trust fund, but largely on a pay-as-you-go basis. The size of the Social Security trust fund was fairly insignificant until the system was amended in 1983. Now the trust fund is increasing and, in effect, contributing to the federal budget surplus. But because of our aging population, predictions are that the Social Security system will experience severe financial difficulties within the next 20-30 years. If the credibility of the system becomes an issue, people may intensify their saving efforts, since they no longer feel they can rely on the1public system to provide for them during retirement. In the past, most of the Social Security taxes were not "saved" but immediately used by the government to finance the benefits of the current retirees. This is why most economists claim that the Social Security system has led to a decrease in the national savings rate and a decrease in the rate of capital accumulation. The magnitude of this decrease, however, has not been clearly established.3.a. If you get a yearly Christmas bonus, you immediately treat it as part of your permanent income and spendit accordingly, that is, ∆C = c(∆Y). In other words, your current consumption will change significantly. 3.b. If you get a Christmas bonus for only this year, you will consider it as transitory income. Since yourpermanent income is hardly affected, you will consume only a small fraction of it and save the rest. In other words, your current consumption will not be significantly affected.4. Gamblers (or thieves) seldom have a very stable income. However, their consumption is determined bytheir permanent income, that is, their expected average lifetime income. Whether they have a large or small income during any given period, their consumption pattern remains relatively stable, since their permanent income is not significantly affected by temporary changes in earnings.5. Both theories, in their own way, try to explain why the short-run mpc is smaller than the long-run mpc.The life-cycle theory attributes the difference to the fact that people prefer a smooth consumption stream over their lifetime. Therefore the average expected lifetime income is the true determinant of current consumption. The permanent income theory suggests that the difference is due to measurement errors.Measured income has two components, that is, permanent and transitory income. But only permanent income is a true determinant of current consumption.6.a. One possible explanation could be that the “baby boomers” were still in their dissaving phase. In otherwords, if households of the baby boom generation still had to buy houses or pay for expenses related to childcare in their late twenties, they may not have been able to save for retirement yet.6.b. If the above explanation is correct, one can expect an increase in saving as these “baby boomers” age,become more financially solvent, and begin to prepare for retirement.7. The ranking from highest to lowest value should be first (a), then (d), and then (b). Clearly, (c) shouldbe lower than (a), but where exactly it ranks after that depends largely on the severeness of the liquidity constraint.8. A series follows a random walk when future changes cannot be predicted from past behavior. In otherwords, it does not have a mean or clear long-run value. Any major change comes about because of random shocks. Hall asserted that changes in current consumption largely come from unanticipated changes in income. According to the life-cycle theory or permanent-income theory, people try to smoothen out their consumption stream in such a way that its expected value is always the same in each period. Therefore, we can express future consumption as the expected value plus some error term, that is, some random value that is unpredictable. This error term is a shock to future income that is spread over the remaining lifetime.Hall supported the permanent-income hypothesis by showing that lagged consumption is the most2significant determinant of future consumption.9. The problem of excess sensitivity means that consumption responds more strongly to predictable changesin current income than the life-cycle theory and permanent-income theories predict. The problem of excess smoothness means that consumption does not respond as strongly to unpredictable changes in current income as these theories predict. However, the existence of these problems does not invalidate the theories.It simply means that the theories can explain consumption behavior only to a certain degree.10. Precautionary (or buffer stock) saving can be explained by uncertainty. It could be uncertainty in regardto one’s life expectancy or one’s time of retirement (af fecting the accumulated saving needed to finance retirement), or uncertainty about future spending needs (which may be caused by a change in family composition or health). Clearly, if we account for such uncertainties, we bring the model much closer to reality. For example, many elderly still continue to save after retirement in anticipation of predicted high medical costs not covered by Medicare.11.a. It is unclear whether an increase in the interest rate leads to an increase or a decrease in saving. On the onehand, as the interest rate increases, the return on saving increases and people may therefore increase their savings effort (due to the substitution effect). On the other hand, a higher return on saving implies that a given future savings goal can now be reached with a smaller savings effort in each year (due to the income effect).11.b. The income effect and the substitution effect generally tend to go in different directions, and the overalloutcome depends on the relative magnitude of these two effects. Until now, empirical evidence has not established a significant sensitivity of saving to changes in the interest rate. This would imply that the income and the substitution effects have about the same magnitude.12.a. According to the Barro-Ricardo hypothesis, it does not matter whether an increase in government spendingis financed by taxation or by issuing debt.12.b. The Barro-Ricardo hypothesis states that people realize that government debt financing by issuing bondssimply postpones taxation. In other words, people know that the government will have to raise taxes in the future to pay back what they have borrowed now. Therefore, expansionary fiscal policy that results in an increase in the budget deficit will no stimulate the economy since it will lead to an increase in saving rather than consumption. People want to be prepared to pay future taxes.12.c. There are two main objections to the Barro-Ricardo hypothesis. One is based on liquidity constraints, thatis, people may want to consume more but may not be able to borrow as much as they like. Therefore, if there is a tax cut, they will consume more, rather than save the tax cut. The other argument is that those people who benefit from a tax cut or an increase in government spending are not the same as those who will have to pay the higher taxes to pay off the debt. This argument assumes that people are not concerned about the welfare of their descendants.Technical Problems:1.a. If income remains constant over time, permanent income equals current income. Your permanent income3this year is YP0 = (1/5)(5*20,000) = 20,000.1.b. Your permanent income next year is YP1 = (1/5)(30,000 + 4*20,000) =1.c. Since C = 0.9YP, your consumption this year is C0 = 0.9*20,000 = 18,000.Your consumption next year is C1 = 0.9*19,000 = 17,100.1.d. In the short run, the mpc = (0.9)(1/5) = 0.18; but in the long run, the mpc = 0.9.1.e. We have already calculated this and next year's permanent income. In each of the coming years you add$30,000 and subtract $20,000, and therefore your permanent income (which is your average over a five year period) will increase by $2,000 each year until it reaches $30,000 after 5 years.YP o = (1/5)(5*20,000) = 20,000YP1 = (1/5)(1*30,000 + 4*20,000) = 22,000YP2 = (1/5)(2*30,000 + 3*20,000) = 24,000YP3 = (1/5)(3*30,000 + 2*20,000) = 26,000YP4 = (1/5)(4*30,000 + 1*20,000) = 28,000YP5 = (1/5)(5*30,000) = 30,000Y30,00028,00026,00024,00022,00020,0000 1 2 3 4 5 time2.a. The person lives for NL = 4 periods and earns a lifetime income ofYL = 30 + 60 + 90 + 0 = 180.Therefore consumption in each period will be C i = (1/4)180 = 45, i = 1, 2, 3, 4.This implies that saving in each period is:S1 = 30 - 45 = - 15; S2 = 60 - 45 = + 15; S3 = 90 - 45 = + 45; S4 = 0 - 45 = - 45.2.b. If liquidity constraints exist and the person cannot borrow in the first period, then she will consume all ofher income, that is, Y1 = C1 = 30.For the remaining three periods the person wants a stable consumption stream. Thus she will consume C(i) = (1/3)(60 + 90 + 0) = 50 in each of the remaining three periods i = 2, 3, 4.42.c. An increase in wealth of only $13 is not enough to offset the difference in consumption patterns betweenperiod 1 and the other periods. Therefore all of the increase in wealth will be consumed in period 1, such that C1 = 43. In the remaining three periods, consumption will be the same as in 2.b.An increase in wealth of $23 will be enough to offset the difference in consumption patterns. Lifetime consumption in each period will now be C i = (1/4)(180 + 23) = 50.75. This means that 20.75 (or almost all of the additional wealth) will be used up in the first period; the remaining 2.25 will be distributed over the next three years.3.a. According to the life-cycle theory and permanent income hypothesis (LC-PIH), the change in consumptionequals the surprise element, that is, ∆C LC-PIH= ε. According to the traditional theory, the change in consumption equals ∆C tr = c(∆YD). Therefore if a fraction λ of the population behaves according to the traditional theory and the other fraction behaves according to LC-PIH, then the total change in consumption is∆C = λ(∆C tr) + (1 - λ)(∆C LC-PIH) = λc(∆YD)+ (1 - λ)cε = (0.7)(0.8)10 + (0.3)ε = 5.6 + (0.3)ε3.b. ∆C = (.3)(.8)10 + (.7)ε = 2.4 + (.7)ε3.c. ∆C = (0)(.8)10 + 1ε = ε4.a. If the real interest rate increases, the opportunity cost of consuming should increase. Therefore, theaverage propensity to save, that is, the fraction of total income that is saved, should increase.4.b. If you only save for retirement and your savings goal is fixed, then you actually will save less. With ahigher interest rate it will take less saving each year to achieve your goal.4.c. The first case (4.a.) describes the substitution effect, whereas the second case (4.b.) describes the incomeeffect. Unless the magnitude of each of these effects is known, we cannot predict the overall effect of this interest rate increase on saving.5. One way to increase saving would be to either privatize or eliminate the Social Security system, so peoplewould have to save for retirement on their own. (Eliminating Social Security is not a very popular measure, but the privatization of Social Security is often discussed.) This would do away with the negative effect on saving that comes from the pay-as-you-go nature of financing Social Security. Another way might be to make it more difficult to borrow. The U.S. tax system encourages people (and firms) to borrow rather than save.5Additional Problems:1. As a share of GDP, how large is consumption compared to the other three main components.Would you expect consumption's share to increase or decrease in a recession?Consumption expenditures are roughly two thirds of total GDP, which is higher than the other three components (investment, government purchases, and net exports) taken together. The ratio of consumption to GDP, however, does not always remain constant. In a recession, for example, when income is below trend, we should expect the consumption-to-GDP ratio to increase, while in a boom, when income is above trend, we should expect the ratio to decrease. The reason is that current consumption is based on permanent rather than current income and when current income is greater than permanent income, the ratio of consumption to income (the apc) goes down. This argument is reinforced by the concept of automatic stability. When GDP falls, personal disposable income falls by less and thus consumption does not fall dramatically.2. True or false? Why?"The marginal propensity to consume out of transitory income is greater than the marginal propensity to consume out of permanent income."False. The permanent-income hypothesis argues that consumption is related to permanent disposable income. Individuals will only revise their consumption behavior significantly if they perceive a change in income as permanent. Very often people are uncertain as to whether a rise in income is permanent or transitory, so they do not significantly revise their consumption patterns immediately. This suggests a lower marginal propensity to consume out of transitory income than out of permanent income.3. Do you think that the marginal propensity to consume out of current income would differ betweentenured professors who have a high degree of job security and professional gamblers who never know when luck will strike?Tenured professors have a high degree of job security and their income does not vary a great deal. They can therefore relatively accurately estimate their permanent income. This means that their current consumption is largely based on current income, implying that their short-run mpc is fairly high. Gamblers, on the other hand, never know what their income in any given year is going to be. Therefore, they base their consumption decisions on their average expected lifetime income (permanent income) rather than on current income. This implies that their short-run mpc is fairly low.4. Is the short-run marginal propensity to save different between farmers and government employees?Why or why not?Government employees generally have very stable incomes and high job security. Therefore they base their consumption decision to a large extent on current income so their short-run mpc is high, while their short-run mps is low. Farmers, on the other hand, have highly variable incomes, depending on weather conditions. Therefore they tend to base their consumption decisions on their permanent income. Their short-run mpc is low, while their short-run mps is high.5. "If most people base their consumption decisions on their current rather than their permanentincome, then the short-run multiplier is greater than the long-run multiplier." Comment on this6statement.If most people follow the traditional theory and base their consumption decisions mostly on current income, then their mpc out of current income is high, making the value of the short-run multiplier high. But if most people follow the permanent-income theory and base their consumption decisions primarily on permanent income, then the short-run mpc is low, making the value of the short-run multiplier low. In either case, as long as some people follow the permanent-income theory, then the short-run multiplier should always be smaller than the long-run multiplier.6. Assume you define your permanent income as the average of this and the past four years’ incomesand you always consume 4/5 of your permanent income. Your earnings record over these years has been: Y t= 40,000, Y t-1 = 38,000, Y t-2 = 34,000, Y t-3 = 32,000, Y t-4 = 31,000.If next year your income increases to Y t+1= 46,000, by how much will your consumption change between year t and year t+1?YP t= (1/5)(40,000 + 38,000 + 34,000 + 32,000 + 31,000) = (1/5)175,000 = 35,000C t= (4/5)YP t = (4/5)35,000 = 28,000YP t+1 = (1/5)(46,000 + 40,000 + 38,000 + 34,000 + 32,000) = (1/5)190,000 = 38,000C t+1 = (4/5)YP t+1 = (4/5)38,000 = 30,400Therefore your consumption will change by C = 2,400.7. Assume a distant aunt gives you several thousand dollars and you use the money to pay back part ofyour student loan. Does your behavior correspond to the prediction of the permanent-income theory?Why or why not?Paying back your debts actually can be seen as an act of "saving." Therefore, since you use some unexpected income to save (rather than consume), your behavior fits the permanent income theory nicely.8. "Early retirement raises aggregate consumption." Comment on this statement.Early retirement reduces lifetime income and increases the length of retirement. The life-cycle model states that individuals consume on the basis of their average lifetime income to maintain a stable consumption path throughout their lives. In an economy with a constant population and no technological progress, aggregate consumption will fall if retirement age drops because people who retire earlier have to accumulate funds for more retirement years over fewer working years. As this can only be accomplished with greater saving, consumption has to be reduced.However, if the population is growing and retirement benefits are financed through taxes levied on workers currently employed, then aggregate consumption may actually rise. In this case, the working population will be paying for the reduction in lifetime earnings experienced by those who have retired early, and there is less need for retirement saving.9. The simple life-cycle hypothesis predicts that people save over their working years but dissave7during their retirement years. Do we actually observe such behavior? If not, can you explain why not?Most elderly actually do not dissave, but they do save less than they did during their working years. One of the reasons that the elderly still save may be the fact that they anticipate large medical bills as they grow older and therefore prefer to keep a certain buffer stock of saving. The elderly may also hope to leave some of their savings as bequests to their children or grandchildren.10. On October 19, 1987, the Dow Jones industrial average dropped about 500 points, or a little morethan 23%. What effect should a decline in stock values of this magnitude have had on aggregate demand according to the life-cycle theory of consumption?According to the life-cycle theory, any change in wealth should affect consumption behavior. The decline in stock values constituted roughly a $500 billion decline in wealth. However, we did not see a huge decrease in consumption in 1987, since the wealth effect tends to be fairly small. In addition, the Fed reacted promptly, announcing that liquidity would be provided if needed.11. Does the random walk model of consumption disprove the permanent income hypothesis? Why orwhy not?Robert Hall tried to disprove the permanent income theory by applying the concept of rational expectations to the theory of consumption. He asserted that consumption patterns may follow a random walk, that is, changes in consumption may come from unanticipated changes in income. However, by concluding that lagged consumption is the most significant determinant of future consumption, Hall actually supported the predictions of the permanent-income hypothesis.12. How is Hall’s random walk model of consumption related to the permanent-income hypothesis andwhat are the implications of these theories for fiscal policy?Hall asserted that changes in current consumption largely come from unanticipated changes in income. Any major change in consumption comes about because of random shocks. According to the permanent-income theory, people try to smoothen out their consumption stream in such a way that its expected value is always the same in each period. Therefore, we can express future consumption as the expected value plus some error term, that is, some random value that is unpredictable. This error term is a shock to future income that is spread over the remaining lifetime. Hall supported the permanent-income hypothesis by showing that lagged consumption is the most significant determinant of future consumption. The implication for fiscal policy is that a temporary tax change will not significantly affect current consumption, unless there are liquidity constraints.13. True or false? Why?"A temporary tax surcharge never has a significant effect on current consumption."False. If individuals know that the tax surcharge is temporary they will not alter their spending patterns as the tax change has little impact on their permanent income. However, when liquidity constraints exist, individuals may be forced to adjust their consumption behavior immediately. If individuals barely earn enough to finance their current consumption, for example, they may be forced to cut their current consumption if a temporary tax surcharge is levied.814. "As a response to a temporary increase in personal and corporate income taxes consumers willreduce their spending and firms will cut production and increase prices. Therefore all we will get is stagflation, that is, an increase in both unemployment and inflation, and tax revenues won't increase." Comment on this statement.The life-cycle/permanent-income theory of consumption predicts that temporary changes in income will not significantly affect the level of consumption. Thus a temporary tax surcharge should not significantly affect aggregate demand. A similar argument can be made about firms, since changes in production are often costly and therefore a temporary surcharge on corporate income taxes should not affect the level of output and prices. The levels of national income and prices should not be affected significantly but we should see a (temporary) increase in tax revenues due to the surcharge. (Note, however, that if consumers and firms face liquidity constraints, they may react to a temporary surcharge in the way described in the statement.)15. "Any tax cut that results in an increase in the budget deficit will fail to stimulate aggregatedemand." Comment on this statement. In your answer explain the effect of such a tax cut on interest rates, money supply, and private domestic saving.The Barro-Ricardo proposition states that a tax cut that results in a budget deficit increase leads to higher saving. Since people will anticipate a future tax increase to finance the higher deficit, permanent income will not be affected. Thus consumption will not be affected; instead people will save the tax cut. Since this is purely a fiscal policy measure, money supply is not affected. The increase in the budget deficit will lead to higher interest rates due to the increased demand for credit. (Note that evidence from the 1980s does not support this hypothesis. The Reagan tax cuts in 1981 resulted in a large increase in the budget deficit but there was no subsequent increase in saving.)916. Assume the government announces plans for fiscal expansion that are likely to result inincreased government borrowing. What effect should this have on aggregate consumption, money supply, the income velocity of money, the trade deficit, and savings?The Barro-Ricardo proposition states that if fiscal expansion results in a budget deficit, the public will anticipate a future tax increase to finance the deficit. They believe that their permanent income will not be affected and choose to save rather than consume more. Therefore, we should expect an increase in private saving but no significant change in consumption. Thus there is no significant change in national income and, since this is solely a fiscal policy, money supply is also not affected. Therefore there is no change in the income velocity. The trade deficit may also not be significantly affected, since domestic saving supports the budget deficit. However, evidence from the 1980s does not lend support for this hypothesis. Saving did not increase after the Reagan tax cuts that resulted in a huge increase in the budget deficit. Instead, we saw an increase in consumption and the trade deficit, since higher interest rates caused an inflow of funds, leading to an appreciation of the U.S. dollar. The income velocity also increased, due to the increase in economic activity.10。

第4篇行为的基础第13章消费与储蓄13.1复习笔记一、消费函数之谜二战后的经验数据表明,凯恩斯的绝对收入假说与现实经济运行情况并不吻合。

有经济学家根据美国1929~1941年的资料得出消费函数为47.60.73d c y =+,但根据美国1948~1988年的资料得出消费函数为0.917d c y =。

可以看出,边际消费倾向并不是递减的,而是递增的;另外,短期边际消费倾向是波动的,而不是稳定的。

也就是说,短期消费函数有下降的平均消费倾向,而长期消费函数有不变的平均消费倾向。

二、消费与储蓄的生命周期一持久性收入理论1.生命周期理论(假说)(1)生命周期理论(假说)的概述生命周期理论(假说)是由美国经济学家F·莫迪利阿尼(F.Modigliani)、R·布伦伯格(R.Brumberg)和A·安东(A.Ando)提出的一种消费函数理论。

该假说认为,消费不取决于现期收入,而主要取决于一生的收入,理性人根据自己一生的收入和财产在长期中计划其消费与储蓄行为,以便在他们整个一生中,以最好的可能方式配置其消费。

由于不依靠基于理性经验法则的单一数值的边际消费倾向,基于最大化行为的生命周期理论意味着产生于持久性收入、暂时性收入与财富的边际消费倾向各不相同。

(2)生命周期理论(假说)的关键假定生命周期理论(假说)的关键假定是绝大多数人会选择稳定的生活方式,在各个时期大致消费相似的水平,一般不会在一个时期内大量储蓄,而在下一时期挥霍无度地消费。

所以,该理论假定人们试图每年消费相同的数量。

(3)生命周期理论(假说)的消费函数WL C YL NL=⨯其中,WL 表示工作年限,NL 表示生活年数,YL 表示每年收入水平。

从公式可以看出,边际消费倾向为WL NL。

在这种分析中,假定储蓄不赚取利息,当前的储蓄将等额转换为未来的消费,所有资产将在生命终结耗尽。

图13-1说明了消费与储蓄的方式。

图13-1生命周期模型中的一生收入、消费、储蓄和财富如图13-1所示,整个一生中消费是稳定不变的,在一生的工作年限期间,工作期限持续WL 年,人们储蓄、积累资产。

第10章收入与支出10.1 复习笔记一、总需求与均衡产出1.总需求概述(1)总需求的含义与构成总需求指整个经济社会在每一个价格水平下对产品和劳务的需求总量,它由消费需求、投资需求、政府支出和国外需求构成。

将商品需求区分为消费()、投资()、政府采购()、与净出口()等需求,则总需求()由下面的公式决定:(2)总需求与国民收入核算中总支出的区别①总需求指计划(意愿)支出量;国民收入中的总支出是指实际发生量;②一般而言在消费、政府采购、以及净出口方面两者不存在差异;③关键在于计划投资与实际投资之间的差别,在实际发生的投资中往往会出现非计划的存货投资。

2.均衡产出(1)均衡产出水平的含义均衡产出水平指总供给和总需求相一致时的产出水平。

经济社会的产量或者国民收入决定于总需求,均衡产出是和总需求相一致的产出,也就是经济社会的收入正好等于全体居民和企业想要有的产出。

当下式成立时,经济处于均衡产出水平状态:(2)非计划库存投资与产量调节机制当总需求即人们想要购买的量与产出不相等时,则存在非计划库存投资或负投资。

可将其概括为:,其中为非计划的库存投资。

①如果产出大于总需求,就有非计划库存投资,此时存在超额库存积累,企业会减少生产,直到产出与总需求再度均衡为止。

②如果产出低于总需求,,企业将增加生产直至均衡恢复为止。

③在均衡状态下,非计划存货投资为零,,企业没有增加或减少产出的激励。

以上论述的以存货调整为基础的产量调节机制如图10-1所示。

图10-1 产出调节机制3.基本结论(1)总需求决定均衡产出(收入)水平(2)在均衡时,非计划库存投资等于零,而且消费者、政府以及外国居民都买到了他们想要购买的商品。

(3)以非计划库存变化为基础的产量调整将使经济达到均衡水平。

二、消费函数与总需求1.消费函数(1)假定条件①不考虑政府部门和对外贸易的影响,即与;②消费需求随收入水平的提高而增加。

(2)消费函数消费函数是描述消费与诸种影响因素之间的数学关系的函数。

第4篇行为的基础第13章消费与储蓄一、判断题1.可以用消费的生命周期假说解释短期边际消费倾向高,长期边际消费倾向低的现象。

()【答案】F【解析】消费的生命周期假说通过对消费者生命周期各个阶段消费—储蓄行为的分析,说明了为什么长期边际消费倾向高于短期边际消费倾向。

2.根据消费的持久性收入假说,长期稳定的收入对消费的影响较小,暂时性收入对消费的影响较大。

()【答案】F【解析】根据消费的持久性收入假说,长期稳定的收入对消费的影响较大,暂时性收入对消费的影响较小。

3.根据消费的持久性收入假说,当人们预期中国经济将高速增长时,他们并不认为中国的消费也会相应增加。

()【答案】T【解析】持久性消费假说认为人们的消费取决于持久收入,他们会将永久性的收入平滑分配到一生之中。

在改革之前,人们的收入较低,因此拉低了人们的永久性收入水平,因此消费并不一定相应增加。

二、单项选择题1.假定行为人每期都有收入,但不能进行借贷。

用YP MPC 和YT MPC 分别表示持久性收入和暂时性收入的边际消费倾向,则()。

A.YT YPMPC MPC >B.YT YPMPC MPC =C.YT YPMPC MPC <D.YP MPC 和YT MPC 无关【答案】C【解析】根据持久消费收入理论,令永久收入函数为:()111P Y Y Y θθθ-=+-<,0<,则当前收入的边际消费倾向为c θ,而长期消费倾向为c 。

因此可知,YT YP MPC MPC <。

2.根据生命周期假说,消费者的消费对积累的财富的比率的变化情况是()。

A.在退休前,这比率是下降的;退休后,则为上升B.在退休前后,这个比率都保持不变C.在退休前后,这个比率都下降D.在退休前,这个比率是上升的,退休后这比率为下降【答案】A 【解析】生命周期假说认为,人的一生分为退休阶段和参加工作阶段,退休阶段无收入,因此其消费由工作阶段的收入来弥补。

在退休阶段,消费是一致的,而财富则随着消费而减少,因此两者比率是上升的;在工作阶段,消费一致,其财富积累随着工作时间增长而增加,因此该比率是下降的。

第1篇导论与国民收入核算第1章导论一、概念题1.总需求曲线(aggregate demand curve)答:总需求曲线表示产品市场和货币市场同时达到均衡时价格水平与国民收入间的依存关系的曲线。

总需求指整个经济社会在每一个价格水平下对产品和劳务的需求总量,它由消费需求、投资需求、政府支出和国外需求构成。

在其他条件不变的情况下,当价格水平提高时,国民收入水平就下降;当价格水平下降时,国民收入水平就上升。

总需求曲线向下倾斜,其机制在于:当价格水平上升时,将会同时打破产品市场和货币市场上的均衡。

在货币市场上,价格水平上升导致实际货币供给下降,从而使LM曲线向左移动,均衡利率水平上升,国民收入水平下降。

在产品市场上,一方面由于利率水平上升造成投资需求下降(即利率效应),总需求随之下降;另一方面,价格水平的上升还导致人们的财富和实际收入水平下降以及本国出口产品相对价格的提高从而使人们的消费需求下降,本国的出口也会减少,国外需求减少,进口增加。

这样,随着价格水平的上升,总需求水平就会下降。

总需求曲线的斜率反映价格水平变动一定幅度使国民收入(或均衡支出水平)变动多少。

IS曲线斜率不变时,LM曲线越陡,则LM移动时收入变动就越大,从而AD曲线越平缓;相反,LM曲线斜率不变时,IS曲线越平缓(即投资需求对利率变动越敏感或边际消费倾向越大),则LM曲线移动时收入变动越大,从而AD曲线也越平缓。

政府采取扩张性财政政策(如扩大政府支出)或扩张性货币政策都会使总需求曲线向右上方移动;反之,则向左下方移动。

2.总供给一总需求模型(aggregate supply-aggregate demand model )答:总供给—总需求模型是把总需求与总供给结合在一起来分析国民收入与价格水平的决定及其变动的国民收入决定模型。

在图1-1中,横轴代表国民收入(Y ),纵轴代表价格水平(P ),1AD 代表原来的总需求曲线,1AS 代表短期总供给曲线,2AS 代表长期总供给曲线。

第17章联邦储备、货币与信用17.1 复习笔记一、货币供应量的决定:货币乘数1.基本概念理解(1)部分准备金银行制度部分准备金银行制度又称作部分准备金制度,指银行只把它们的部分存款作为准备金的制度。

在这种制度下,银行将部分存款作为准备金,而将其余存款用于向企业或个人发放贷款或者投资,若得到贷款的人再将贷款存入其他银行,从而使其他银行增加了发放贷款或者投资的资金,这一过程持续下去,使得更多的货币被创造出来了。

因此,部分准备金的银行制度是银行能够进行多倍货币创造的前提条件,在百分之百准备金银行制度下,银行不能进行多倍货币创造。

(2)高能货币高能货币亦称“基础货币”、“强力货币”、“货币基数”或“货币基础”,是经过商业银行的存贷款业务而能扩张或收缩货币供应量的货币,包括商业银行存入联储的存款准备金(包括法定准备金和超额准备金)与社会公众所持有的现金之和。

联储控制高能货币是决定货币供应量的主要途径。

高能货币的四个属性为:①可控性,高能货币是联储能调控的货币;②负债性,高能货币是联储的负债;③扩张性,高能货币能被联储吸收作为创造存款货币的基础,具有多倍创造的功能;④初始来源的惟一性,高能货币的增量只能来源于联储。

2.货币存量的决定(1)货币乘数①货币乘数的定义货币乘数又称为“货币创造乘数”或“货币扩张乘数”,指联储创造一单位的基础货币所能增加的货币供应量,是货币存量对高能货币存量的比率,且货币乘数大于1。

②货币乘数的表达式货币存量和高能货币通过货币乘数相联系,如图17-1所示。

图17-1 高能货币与货币存量的关系忽略不计各种存款之间的差别,以表示货币供给量,即货币存量,以表示一个相同类型的存款,表示通货,表示高能货币,表示货币乘数,表示准备金,由和,可以得到:其中,,称为通货—存款比率;,称为准备金比率。

公式表明,公众、银行和联邦储备的行为分别通过影响通货—存款比、准备金比率和高能货币来影响货币供应量。

③货币乘数的决定因素根据公式可知,通货—存款比率和准备金比率是决定货币乘数大小的两大因素。

第13章消费与储蓄一、概念题1.巴罗—李嘉图等价定理(李嘉图等价)(Barro ricardo equivalence proposition (ricardian equivalence))答:李嘉图等价定理是英国经济学家李嘉图提出,并由新古典主义学者巴罗根据理性预期重新进行论述的一种理论。

该理论认为,在政府支出一定的情况下,政府采取征税或发行公债来为政府筹措资金,其效应是相同的。

李嘉图等价理论的思路是:假设政府预算在初始时是平衡的。

政府实行减税以图增加私人部门和公众的支出,扩大总需求,但减税导致财政赤字。

如果政府发行债券来弥补财政赤字,由于在未来某个时点,政府将不得不增加税收,以便支付债务和积累的利息。

具有前瞻性的消费者知道,政府今天借债意味着未来更高的税收。

用政府债务融资的减税并没有减少税收负担,它仅仅是重新安排税收的时间。

因此,这种政策不会鼓励消费者更多支出。

根据这一定理,政府因减税措施而增发的公债会被人们作为未来潜在的税收考虑到整个预算约束中去,在不存在流动性约束的情况下,公债和潜在税收的现值是相等的。

这样,变化前后两种预算约束本质上是一致的,从而不会影响人们的消费和投资。

李嘉图等价定理反击了凯恩斯主义所提出的公债是非中性的,即对宏观经济是有益处的观点。

但实际上,该定理成立前提条件太苛刻,现实经济很难满足。

2.政府储蓄(government saving)答:政府储蓄亦称“公共储蓄”,指财政收入与财政支出的差额。

若财政收入大于财政支出,就称财政盈余为正储蓄,如果财政收入小于财政支出,就称财政赤字为负储蓄,但一般说政府储蓄时指的是正储蓄。

政府储蓄可以通过增收、节支的手段来实现,但从目前大多数国家情况看,节支与增收均较困难,财政多呈现赤字,政府没有储蓄,反而需发行国债借老百姓的钱弥补财政赤字。

3.缺乏远见(myopia)答:缺乏远见指家庭关于未来收入流的短视眼光,不能正确认识到未来的真正收入。

消费对当前收入的敏感性的另一种解释就是消费者缺乏远见,这在实际上难以和流动性约束假说区别开。

例如,联邦储备理事会的大卫·威尔科克斯(David wilcox)已表明,社会保障福利金即将增加(这总是在变动之前至少六个星期发布)的公告,并不会引起消费的变动,一直要到福利金的增加被实际支付时,消费才会改变。

一旦增加的福利金支付出去,接受者肯定会调整他们的支出——主要是对耐用品的支出。

这种消费调整的延迟可能是由于接受者在收到较高的支付之前,缺乏能使其调整支出的资产(流动性约束),或者是由于他们没有注意到这项公告(缺乏远见),也可能是他们不相信这项公告。

4.生命周期假说(life cycle hypothesis)答:生命周期假说是由美国经济学家F.莫迪利阿尼(F.Modigliani)、R·布伦伯格(R.Brumberg)和A·安东(A.Ando)提出的一种消费函数理论。

该假说指出,在人一生中的各个阶段,个人消费占其一生收入现值的比例是固定的。

消费不取决于现期收入,而主要取决于一生的收入。

生命周期假说的消费函数可以表示为:L RC bY W σ=+其中:C 代表消费,b 代表劳动收入中的边际消费倾向,L Y 代表劳动收入,σ代表实际财产的边际消费倾向,R W 代表实际财产。

生命周期假说认为,理性人根据自己一生的收入和财产来安排自己一生的消费并保证每年的消费水平保持在一定水平。

人们在一生中的消费规律是:青年时以未来收入换取借款,中年时清偿早期债务或储蓄防老,老年人逐日消耗一生积蓄。

一般而言,中年人具有较高水平的收入,青年人和老年人收入水平较低。

所以,中年人具有较低的平均消费倾向,青年人和老年人具有较高的平均消费倾向。

但终其一生,个人具有相对稳定的长期消费倾向。

这就很好地解释了消费函数在长期和短期中的不同形式。

5.可操作的遗赠动机(operational bequest motive)答:可操作的遗赠动机指某人将遗产留给后代或朋友或慈善施舍的意愿。

遗赠动机是储蓄的原因之一。

如果由于遗赠动机而进行的储蓄占总储蓄的比重较大,而生命周期储蓄的比重较小,那么由于收入再分配政策主要影响遗赠储蓄,其对增加总消费的作用也较大。

生命周期储蓄是必需品,而遗赠储蓄是奢侈品。

高收入者进行储蓄的动机,更多是出于遗赠目的(因为他们的收入很高,不必担心退休后消费水平会降低而进行大量的生命周期储蓄,同时他们有能力进行遗赠储蓄),所以其遗赠储蓄的比重很高;而低收入者则更多出于生命周期动机而储蓄(为保证退休后消费水平不致降低,同时也没有能力考虑过多遗赠),所以其生命周期储蓄的比重较大。

6.持久性收入理论(permanent income theory)答:持久性收入理论指美国经济学家M·弗里德曼提出的一种消费函数理论。

它指出个人或家庭的消费取决于持久收入。

持久收入可以被认为是一个人期望终身从其工作或持有的财富中产生的收入。

弗里德曼的理论认为,在保持财富完整性的同时,个人的消费在其工作和财富的收入流量的现值中占有一个固定的比例。

持久收入假说的消费函数可以表示为:其中:C代表消费,c代表边际消费倾向,YP代表持久收入。

而在实际情况下,个人在任何时期的实际收入可能与持久收入不同。

这种不同可以解释在消费函数形式方面相互矛盾的原因。

该假说认为,个人的收入和消费都包含一个持久部分和一个暂时部分。

持久收入和持久消费分别由一个预计的、有计划的收入成分和消费成分组成;暂时收入和暂时消费则分别由收入方面的意外收益或意外损失以及消费方面的不可预知的变化构成。

在长期内,个人消费占有固定比例的持久收入,这就解释了长期消费函数。

在短期内,许多家庭或个人在经济周期中会面临一个负值的暂时收入,然而他们的消费与其持久收入相关,因而他们的平均消费倾向增加,这就解释了短期消费函数。

由于每个家庭和个人都寻求消费其持久收入的一个固定比例,因而意外的收益或损失将不会影响消费。

但在实际运用中,持久收入和消费的价值估计非常困难。

弗里德曼的持久收入假说还是他的现代货币数量论的重要组成部分。

弗里德曼用持久收入的稳定性,证明了货币需求的稳定性,从而说明了货币供给量对经济的决定性作用。

7.缓冲库存(buffer stock saying)答:缓冲库存指为了平抑市场上商品价格的波动而保持的一定数量的库存。

通常情况下,主要由政府、地区联盟或世界性经济组织来担当建立缓冲存货的角色。

当某种商品价格看跌时,则购进该种商品;当商品价格继续看涨时,就出售该种商品。

其目的是为了避免因商品价格的大起大落而影响生产者和消费者的利益及他们预期的稳定性。

建立缓冲存货往往是有针对性的,所储存的商品通常是那些需求弹性小、容易受到市场炒作和冲击的商品。

同时,在操作中也需要考虑到这类商品是否便于储存,以及储存的费用是否昂贵等。

8.终生预算约束(lifetime budget constraint)答:终生预算约束指现在和未来一定时期内,以贴现值计算的消费总量必须等于资源总量。

它是反映跨期的所有可行的消费组合的曲线,适用于一个以上时期的支出与收入的预算限制。

终生预算约束的公式为:()()1111Tt t TC r C r C --++++++ ()()1111T t t T YL r YL r YL --+=++++++ 财富9.个人储蓄(personal saving)答:个人储蓄指由个人和家庭进行的储蓄。

个人及家庭储蓄的原因主要包括为不测事件建立储备金、为自己年老时积累资金、为保护自己的家属或为了其他某一具体目的等储蓄资金。

个人和家庭储蓄也为商业资本投资提供了部分资金来源。

影响个人及家庭储蓄水平的主要因素包括收入的多少、人们对未来收入的预期以及利息率的高低等。

10.企业储蓄(business saving)答:企业储蓄指企业将征收所得税和进行分配之后的净利润存入金融机构的行为。

其目的一是为了获取利息收益,二是为了将一部分闲置资金保存下来作为扩大再生产之用。

对企业利息征收所得税,直接影响是减少了企业的税后留利,对企业的扩大再生产产生不利影响,其结果是降低了企业储蓄愿望。

影响企业储蓄的主要因素是投资的边际效率。

11.终生效用(lifetime income)答:终生效用指各个时期效用的总和。

LC PIH -理论的现代方法开始在形式上描述一个代表性消费者终生效用最大化问题。

在一个特定时期内,消费者享受该时期的消费效用()t u C 。

人们宁愿现在消费而不是放到以后消费,因此以参数δ表示的时间偏好率较高,使得消费提前。

抵消这种影响的是推迟消费,储蓄起来获取利息(利率为r )。

如果人们耐心等待,就能增加消费。

计算每个时期的δ与r 的百分比,则得到终生效用的方程,即:一生的效用=()()()()()1111T t t T u C u C u C δδ--++++++ 取决于:()()1111T t t T C r C r C --++++++ =财富+()()1111Tt t T YL r YL r YL --++++++ 消费者选择各个时期的消费,以便使其一生的效用最大化,它取决于等于其一生总财力的一生的总消费。

12.私人储蓄(private saving)答:私人储蓄指社会公众或居民将个人可支配收入扣除消费以后所余下的部分,在内容上由个人储蓄和企业储蓄两部分构成。

私人储蓄是市场经济中投资活动的主要来源,因此也是一国资本形成和经济增长的重要支柱。

进行私人储蓄的行为是典型的市场主体决策行为。

所以,经济学中关于储蓄的理论(如储蓄动机、储蓄倾向、储蓄水平等)大部分是围绕着私人储蓄来展开的。

由于私人储蓄可能大于或小于意愿的投资水平,因此政府需要采取宏观政策以对公共储蓄进行调节,或引入国外储蓄进行补充。

13.过度敏感性(excess sensitivity)答:过度敏感性指当一个变量对另一个变量变化的反应比理论上预计的程度更大时的情况。

例如,消费存在着过度敏感性,就是指消费的反应太强烈,以至于无法对收入变动作出预期。

消费的过度敏感性的发现与消费理论发展密不可分。

西方对消费理论的研究可以分为几。