林语堂翻译

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:119.00 KB

- 文档页数:11

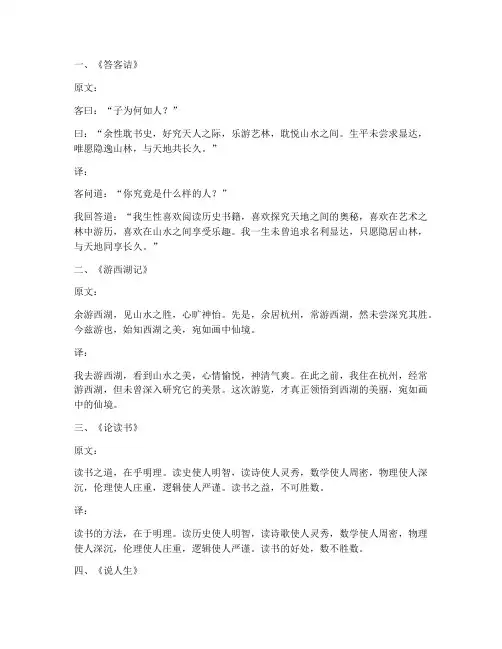

一、《答客诘》原文:客曰:“子为何如人?”曰:“余性耽书史,好究天人之际,乐游艺林,耽悦山水之间。

生平未尝求显达,唯愿隐逸山林,与天地共长久。

”译:客问道:“你究竟是什么样的人?”我回答道:“我生性喜欢阅读历史书籍,喜欢探究天地之间的奥秘,喜欢在艺术之林中游历,喜欢在山水之间享受乐趣。

我一生未曾追求名利显达,只愿隐居山林,与天地同享长久。

”二、《游西湖记》原文:余游西湖,见山水之胜,心旷神怡。

先是,余居杭州,常游西湖,然未尝深究其胜。

今兹游也,始知西湖之美,宛如画中仙境。

译:我去游西湖,看到山水之美,心情愉悦,神清气爽。

在此之前,我住在杭州,经常游西湖,但未曾深入研究它的美景。

这次游览,才真正领悟到西湖的美丽,宛如画中的仙境。

三、《论读书》原文:读书之道,在乎明理。

读史使人明智,读诗使人灵秀,数学使人周密,物理使人深沉,伦理使人庄重,逻辑使人严谨。

读书之益,不可胜数。

译:读书的方法,在于明理。

读历史使人明智,读诗歌使人灵秀,数学使人周密,物理使人深沉,伦理使人庄重,逻辑使人严谨。

读书的好处,数不胜数。

四、《说人生》原文:人生如梦,岁月如梭。

世间万事,皆过眼云烟。

唯有读书,可以陶冶性情,增长知识。

吾辈当珍惜时光,努力读书,以不负此生。

译:人生如梦,岁月如梭。

世间万物,都如同过眼云烟。

唯有读书,可以陶冶性情,增长知识。

我们应当珍惜时光,努力读书,不负此生。

五、《论诗》原文:诗者,情之发也。

诗之妙,在乎意境。

诗之高,在乎意境深远。

诗之真,在乎意境真实。

诗之奇,在乎意境新奇。

诗之美,在乎意境美妙。

译:诗,是情感的抒发。

诗的妙处,在于意境。

诗的高远,在于意境的深远。

诗的真实,在于意境的真实。

诗的新奇,在于意境的新奇。

诗的美妙,在于意境的美妙。

以上为林语堂文言文翻译,共计五百字。

林语堂的文言文作品,语言优美,寓意深刻,具有很高的文学价值。

希望这篇翻译能够帮助读者更好地了解林语堂的文言文魅力。

《兰亭集序》林语堂版英译文来源:It is the ninth year of Yonghe (A.C.353), also known as the year of Guichou in terms of the Chinese lunar calendar.On one of those late spring days, we gather at the Orchid Pavilion, which is located in Shanyin County, Kuaiji Prefecture, for dispelling bad luck and praying for good fortune.The attendees of the gathering are all virtuous intellectuals, varying from young to old. Endowed with great mountains and lofty peaks, Orchid Pavilion has flourishing branches and high bamboo bushes all around, together with a clear winding brook engirdled, which can thereby serve the guests by floating the wine glasses on top for their drinking. Seated by the bank of brook, people will still regale themselves right by poetizing their mixed feelings and emotions with wine and songs, never mind the absence of melody from string and wind instruments.永和九年,岁在癸(guǐ)丑。

----------------------- Page 1-----------------------《幽梦影》——林语堂译(品格辑) xyer@ 白云黄鹤BBS 录入1《幽梦影》——林语堂译品格——之一何谓善人?无损于世者则谓之善人;何谓恶人?有害于世者则谓之恶人。

含徵曰:尚有有害于世而反邀善人之誉。

此实为好利而显为名高者,则又恶人之尤。

What is a good man? Simply one whose life is useful to the world. And a bad man is simply onewhose life is harmful to others.Hanchen: There are, however, those who are harmful and yet enjoy a good reputation, and whomanage to profit by a show of unselfishness. These are the worst of all.品格——之二无善无恶是圣人,善多恶少是贤者,善少恶多是庸人,有恶无善是小人,有善无恶是仙佛。

(冒)青若曰:昔人云,善可为而不可为。

Those beyond good and evil are sages. Those who have more good than bad in them aredistinguished persons. Common men have more evil than good, and the scum and riffraff ofsociety have no good at all. Fairies and Buddha have only good and no evil.Chinjo: An ancient one said, “One should do good, of course, but there are times when one shouldnot."品格——之三昭君以和亲而显,刘蕡(fei4)以下第而传,可谓之不幸,不可谓之缺憾。

昔陶渊明尝谓:“晋太元中,武陵人捕鱼为业。

缘溪行,忘路之远近。

忽逢桃花林,夹岸数百步,中无杂树,芳草鲜美,落英缤纷,渔人甚异之。

复前行,欲穷其林。

”余尝读此,亦异之。

盖陶公所述,实为奇境,非世所常有也。

然则桃花源果何在?岂非虚构之境,以寓其理想耶?然余窃以为,桃花源非虚构也。

盖桃花源者,乃陶公心中之理想境界,实有其地,而非虚造。

何也?盖陶公生于乱世,饱经忧患,故其心中所想,皆宁静、平和之境。

而桃花源正符合其理想,故陶公特为此记。

夫桃花源之境,实为陶公心中之乐土。

其中渔者耕者,皆安居乐业,不相侵扰。

村中环境优美,山水相映,四季如春。

此乃陶公心中之世外桃源,故曰:“土地平旷,屋舍俨然,有良田美池桑竹之属。

阡陌交通,鸡犬相闻。

”余读此,不禁感慨系之。

想吾辈生于世间,奔波劳碌,为名利所困,何尝不向往此等宁静、平和之境?桃花源虽不可及,然吾辈心中,亦当存此理想,以求心灵之宁静。

陶公所述桃花源,实为一种超脱世俗的理想境界。

其中渔者耕者,皆不慕名利,安心乐道。

此乃陶公所向往之世外桃源,亦为世人所向往之境界。

余尝思,桃花源虽美,然世人之心,未必能如桃花源中之人。

世人皆有所求,欲求名利,欲求地位,欲求权力。

然此等欲望,往往使人迷失本性,远离宁静、平和之境。

故余以为,桃花源虽美,然世人欲求宁静、平和,仍需从内心做起。

唯有放下名利之心,安心乐道,方能回归桃花源之境。

陶公所述桃花源,实为一种超脱世俗的理想境界。

其中渔者耕者,皆不慕名利,安心乐道。

此乃陶公所向往之世外桃源,亦为世人所向往之境界。

余读《桃花源记》,心中不禁涌起一股向往之情。

然桃花源虽美,世人欲求宁静、平和,仍需从内心做起。

愿世人皆能放下名利之心,安心乐道,回归桃花源之境,以求心灵之宁静。

余闻之:桃花源者,乃陶公心中之理想境界,实有其地,而非虚造。

世人欲求宁静、平和,当以桃花源为榜样,从内心做起,以求心灵之宁静。

陶公所述桃花源,实为一种超脱世俗的理想境界。

其中渔者耕者,皆不慕名利,安心乐道。

《幽梦影》——林语堂译1读书与文学——之一古今至文,皆血泪所成。

(吴)晴岩曰:山老《清泪痕》一书,细看皆是血泪。

含徵曰:古今恶文亦纯是血。

All literary masterpieces of the ancients and moderns were written with blood and tears.Ching-ai: Even this book of enjoyment of life shows tears. Looked at more closely, sometimes they are tears of blood.Hanchen: Bad literature is probably written all with blood and no tears. (All sex and violence.)读书与文学——之二文章是案头山水,山水是地上之文章。

圣许曰:文章必明秀方可作案头山水,山水必曲折乃可名地上之文章。

Literature is landscape on the desk; landscape is literature on the earth.Shengshu: One necessary qualification for each. Writing must have sinuous grace before it can be compared with landscape, and a landscape must have pleasant turns and surprises before it can be compared with writing.读书与文学——之三善读书者无之而非书,山水亦书也,棋酒亦书也,花月亦书也。

善游山水者无之而非山水,书史亦山水也,诗酒亦山水也,花月亦山水也。

隺山曰:此方是真善读书人,善游山水人。

含徵曰:五更卧被时,有无数山水书籍,在眼前胸中。

On Leveling All ThingsTsech'i of Nankuo sat leaning on a low table. Gazing up to heaven, he sighed and looked as though he had lost his mind.Yench'eng Tseyu, who was standing by him, exclaimed, "What are you thinking about that your body should become thus like dead wood, your mind like burnt-out cinders? Surely the man now leaning on the table is not he who was here just now.""My friend," replied Tsech'i, "your question is apposite. Today I have lost my Self.... Do you understand? ... Perhaps you only know the music of man, and not that of Earth. Or even if you have heard the music of Earth, perhaps you have not heard the music of Heaven.""Pray explain," said Tseyu."The breath of the universe," continued Tsech'i, "is called wind. At times, it is inactive. But when active, all crevices resound to its blast. Have you never listened to its deafening roar?"Caves and dells of hill and forest, hollows in huge trees of many a span in girth -- some are like nostrils, and some like mouths, and others like ears, beam-sockets, goblets, mortars, or like pools and puddles. And the wind goes rushing through them, like swirling torrents or singing arrows, bellowing, sousing, trilling, wailing, roaring, purling, whistling in front and echoing behind, now soft with the cool blow, now shrill with the whirlwind, until the tempest is past and silence reigns supreme. Have you never witnessed how the trees and objects shake and quake, and twist and twirl?""Well, then," inquired Tseyu, "since the music of Earth consists of hollows and apertures, and the music of man of pipes and flutes, of what consists the music of Heaven?""The effect of the wind upon these various apertures," replied Tsech'i, "is not uniform, but the sounds are produced according to their individual capacities. Who is it that agitates their breasts?"Great wisdom is generous; petty wisdom is contentious. Great speech is impassioned, small speech cantankerous."For whether the soul is locked in sleep or whether in waking hours the body moves, we are striving and struggling with the immediate circumstances. Some are easy-going and leisurely, some are deep and cunning, and some are secretive. Now we are frightened over petty fears, now disheartened and dismayed over some great terror. Now the mind flies forth like an arrow from a cross-bow, to be the arbiter of right and wrong. Now it stays behind as if sworn to an oath, to hold on to what it has secured. Then, as under autumn and winter's blight, comes gradual decay, and submerged in its own occupations, it keeps on running its course, never to return. Finally, worn out and imprisoned, it is choked up like an old drain, and the failing mind shall not see light again(8)."Joy and anger, sorrow and happiness, worries and regrets, indecision and fears, come upon us by turns, with ever-changing moods, like music from the hollows, or like mushrooms from damp. Day and night they alternate within us, but we cannot tell whence they spring. Alas! Alas! Could we for a moment lay our finger upon their very Cause?"But for these emotions I should not be. Yet but for me, there would be no one to feel them. So far we can go; but we do not know by whose order they come into play. It would seem there was a soul;(9) but the clue to its existence is wanting. That it functions is credible enough, though we cannot see its form. Perhaps it has inner reality withoutoutward form."Take the human body with all its hundred bones, nine external cavities and six internal organs, all complete. Which part of it should I love best? Do you not cherish all equally, or have you a preference? Do these organs serve as servants of someone else? Since servants cannot govern themselves, do they serve as master and servants by turn? Surely thereis some soul which controls them all."But whether or not we ascertain what is the true nature of this soul, it matters but little to the soul itself. For once coming into this material shape, it runs its course until it is exhausted. To be harassed by the wear and tear of life, and to be driven along without possibility of arrestingone's course, -- is not this pitiful indeed? To labor without ceasing all life, and then, without living to enjoy the fruit, worn out with labor, to depart, one knows not whither, -- is not this a just cause for grief?""Men say there is no death -- to what avail? The body decomposes, and the mind goes with it. Is this not a great cause for sorrow? Can the world be so dull as not to see this? Or is it I alone who am dull, and others not so?"Now if we are to be guided by our prejudices, who shall be without a guide? What need to make comparisons of right and wrong with others? And if one is to follow one's own judgments according to his prejudices, even the fools have them! But to form judgments of right and wrong without first having a mind at all is like saying, "I left for Yu:eh today, and got there yesterday." Or, it is like assuming something which does not exist to exist. The (illusions of) assuming something which does not exist to exist could not be fathomed even by the divine Yu:; how much less could we?For speech is not mere blowing of breath. It is intended to say some thing, only what it is intended to say cannot yet be determined. Is there speech indeed, or is there not? Can we, or can we not, distinguish it from the chirping of young birds?How can Tao be obscured so that there should be a distinction of trueand false? How can speech be so obscured that there should be a distinction of right and wrong?(10) Where can you go and find Tao not to exist? Where can you go and find that words cannot be proved? Tao is obscured by our inadequate understanding, and words are obscured by flowery expressions. Hence the affirmations and denials of the Confucian and Motsean(11) schools, each denying what the other affirms and affirming what the other denies. Each denying what the other affirms and affirming what the other denies brings us only into confusion.There is nothing which is not this; there is nothing which is not that. What cannot be seen by what (the other person) can be known by myself. Hence I say, this emanates from that; that also derives from this. This is the theory of the interdependence of this and that (relativity of standards).Nevertheless, life arises from death, and vice versa. Possibility arises from impossibility, and vice versa. Affirmation is based upon denial, and vice versa. Which being the case, the true sage rejects all distinctionsand takes his refuge in Heaven (Nature). For one may base it on this, yet this is also that and that is also this. This also has its 'right' and 'wrong', and that also has its 'right' and 'wrong.' Does then the distinction between this and that really exist or not? When this (subjective) and that (objective) are both without their correlates, that is the very 'Axis ofTao.' And when that Axis passes through the center at which all Infinities converge, affirmations and denials alike blend into the infinite One. Hence it is said that there is nothing like using the Light.To take a finger in illustration of a finger not being a finger is not so good as to take something which is not a finger to illustrate that a finger is not a finger. To take a horse in illustration of a horse not being a horse is not so good as to take something which is not a horse to illustrate that a horse is not a horse(12). So with the universe which is but a finger, but a horse. The possible is possible: the impossible is impossible. Tao operates, and the given results follow; things receive names and are said to be what they are. Why are they so? They are said to be so! Why are they not so? They are said to be not so! Things are so by themselves and have possibilities by themselves. There is nothing which is not so and there is nothing which may not become so.Therefore take, for instance, a twig and a pillar, or the ugly person and the great beauty, and all the strange and monstrous transformations. These are all leveled together by Tao. Division is the same as creation; creation is the same as destruction. There is no such thing as creation or destruction, for these conditions are again leveled together into One. Only the truly intelligent understand this principle of the leveling of all things into One. They discard the distinctions and take refuge in the common and ordinary things. The common and ordinary things serve certain functions and therefore retain the wholeness of nature. From this wholeness, one comprehends, and from comprehension, one to the Tao. There it stops. To stop without knowing how it stops -- this is Tao.But to wear out one's intellect in an obstinate adherence to the individuality of things, not recognizing the fact that all things are One, -- that is called "Three in the Morning." What is "Three in the Morning?" A keeper of monkeys said with regard to their rations of nuts that each monkey was to have three in the morning and four at night. At this the monkeys were very angry. Then the keeper said they might have four in the morning and three at night, with which arrangement they were all well pleased. The actual number of nuts remained the same, but there was a difference owing to (subjective evaluations of) likes and dislikes.It also derives from this (principle of subjectivity). Wherefore the true Sage brings all the contraries together and rests in the natural Balance of Heaven. This is called (the principle of following) two courses (at once). The knowledge of the men of old had a limit. When was the limit? It extended back to a period when matter did not exist. That was the extreme point to which their knowledge reached. The second period was that of matter, but of matter unconditioned (undefined). The third epoch saw matter conditioned (defined), but judgments of true and false were still unknown. When these appeared, Tao began to decline. And with the decline of Tao, individual bias (subjectivity) arose.Besides, did Tao really rise and decline?(13) In the world of (apparent) rise and decline, the famous musician Chao Wen did play the string instrument; but in respect to the world without rise and decline, Chao Wen did not play the string instrument. When Chao Wen stopped playing the string instrument, Shih K'uang (the music master) laid down hisdrum-stick (for keeping time), and Hueitse (the sophist) stopped arguing, they all understood the approach of Tao. These people are the best in their arts, and therefore known to posterity. They each loved his art, and wanted to excel in his own line. And because they loved their arts, theywanted to make them known to others. But they were trying to teach what (in its nature) could not be known. Consequently Hueitse ended in the obscure discussions of the "hard" and "white"; and Chao Wen's son tried to learn to play the stringed instrument all his life and failed. If this may be called success, then I, too, have succeeded. But if neither of them could be said to have succeeded, then neither I nor others have succeeded. Therefore the true Sage discards the light that dazzles and takes refuge in the common and ordinary. Through this comes understanding.Suppose here is a statement. We do not know whether it belongs to one category or another. But if we put the different categories in one, then the differences of category cease to exist. However, I must explain. If there was a beginning, then there was a time before that beginning, and a time before the time which was before the time of that beginning. If there is existence, there must have been non-existence. And if there was a time when nothing existed, then there must have been a time when even nothing did not exist. All of a sudden, nothing came into existence. Could one then really say whether it belongs to the category of existence or of non-existence? Even the very words I have just now uttered, -- I cannot say whether they say something or not.There is nothing under the canopy of heaven greater than the tip of abird's down in autumn, while the T'ai Mountain is small. Neither is there any longer life than that of a child cut off in infancy, while P'eng Tsu himself died young. The universe and I came into being together; I and everything therein are One.If then all things are One, what room is there for speech? On the other hand, since I can say the word 'one' how can speech not exist? If it does exist, we have One and speech -- two; and two and one -- three(14) from which point onwards even the best mathematicians will fail to reach (the ultimate); how much more then should ordinary people fail?Hence, if from nothing you can proceed to something, and subsequently reach there, it follows that it would be still easier if you were to start from something. Since you cannot proceed, stop here. Now Tao by its very nature can never be defined. Speech by its very nature cannot express the absolute. Hence arise the distinctions. Such distinctions are: "right" and "left," "relationship" and "duty," "division" and "discrimination, "emulation and contention. These are called the Eight Predicables.Beyond the limits of the external world, the Sage knows that it exists,but does not talk about it. Within the limits of the external world, the Sage talks but does not make comments. With regard to the wisdom of the ancients, as embodied in the canon of Spring and Autumn, the Sage comments, but does not expound. And thus, among distinctions made, there are distinctions that cannot be made; among things expounded, there are things that cannot be expounded.How can that be? it is asked. The true Sage keeps his knowledge within him, while men in general set forth theirs in argument, in order to convince each other. And therefore it is said that one who argues does so because he cannot see certain points.Now perfect Tao cannot be given a name. A perfect argument does not employ words. Perfect kindness does not concern itself with (individual acts of) kindness(15). Perfect integrity is not critical of others(16). Perfect courage does not push itself forward.For the Tao which is manifest is not Tao. Speech which argues falls short of its aim. Kindness which has fixed objects loses its scope. Integrity which is obvious is not believed in. Courage which pushes itself forward never accomplishes anything. These five are, as it were, round (mellow) with a strong bias towards squareness (sharpness). Therefore that knowledge which stops at what it does not know, is the highest knowledge.Who knows the argument which can be argued without words, and the Tao which does not declare itself as Tao? He who knows this may be said to enter the realm of the spirit (17). To be poured into without becoming full, and pour out without becoming empty, without knowing how this is brought about, -- this is the art of "Concealing the Light."Of old, the Emperor Yao said to Shun, "I would smite the Tsungs, and the Kueis, and the Hsu:-aos. Since I have been on the throne, this has ever been on my mind. What do you think?""These three States," replied Shun, "lie in wild undeveloped regions. Why can you not shake off this idea? Once upon a time, ten suns came out together, and all things were illuminated thereby. How much greater should be the power of virtue which excels the suns?"Yeh Ch'u:eh asked Wang Yi, saying, "Do you know for certain that all things are the same?""How can I know?" answered Wang Yi. "Do you know what you do not know?""How can I know!" replied Yeh Ch'u:eh. "But then does nobody know?" "How can I know?" said Wang Yi. "Nevertheless, I will try to tell you. How can it be known that what I call knowing is not really not knowing and that what I call not knowing is not really knowing? Now I would ask you this, If a man sleeps in a damp place, he gets lumbago and dies. But how about an eel? And living up in a tree is precarious and trying to the nerves. But how about monkeys? Of the man, the eel, and the monkey, whose habitat is the right one, absolutely? Human beings feed on flesh, deer on grass, centipedes on little snakes, owls and crows on mice. Of these four, whose is the right taste, absolutely? Monkey mates with the dog-headed female ape, the buck with the doe, eels consort with fishes, while men admire Mao Ch'iang and Li Chi, at the sight of whom fishes plunge deep down in the water, birds soar high in the air, and deer hurry away. Yet who shall say which is the correct standard of beauty? In my opinion, the doctrines of humanity and justice and the paths of right and wrong are so confused that it is impossible to know their contentions." "If you then," asked Yeh Ch'u:eh, "do not know what is good and bad, is the Perfect Man equally without this knowledge?""The Perfect Man," answered Wang Yi, "is a spiritual being. Were the ocean itself scorched up, he would not feel hot. Were the great rivers frozen hard, he would not feel cold. Were the mountains to be cleft by thunder, and the great deep to be thrown up by storm, he would not tremble with fear. Thus, he would mount upon the clouds of heaven, and driving the sun and the moon before him, pass beyond the limits of this mundane existence. Death and life have no more victory over him. How much less should he concern himself with the distinctions of profit and loss?"Chu: Ch'iao addressed Ch'ang Wutse as follows: "I heard Confucius say, 'The true Sage pays no heed to worldly affairs. He neither seeks gain nor avoids injury. He asks nothing at the hands of man and does not adhereto rigid rules of conduct. Sometimes he says something without speaking and sometimes he speaks without saying anything. And so he roams beyond the limits of this mundane world.'These,' commented Confucius, 'are futile fantasies.' But to me they are the embodiment of the most wonderful Tao. What is your opinion?" "These are things that perplexed even the Yellow Emperor," repliedCh'ang Wutse. "How should Confucius know? You are going too far ahead. When you see a hen's egg, you already expect to hear a cock crow.When you see a sling, you are already expected to have broiled pigeon. I will say a few words to you at random, and do you listen at random. "How does the Sage seat himself by the sun and moon, and hold the universe in his grasp? He blends everything into one harmonious whole, rejecting the confusion of this and that. Rank and precedence, which the vulgar sedulously cultivate, the Sage stolidly ignores, amalgamating the disparities of ten thousand years into one pure mold. The universe itself, too, conserves and blends all in the same manner."How do I know that love of life is not a delusion after all? How do Iknow but that he who dreads death is not as a child who has lost his way and does not know his way home?"The Lady Li Chi was the daughter of the frontier officer of Ai. When the Duke of Chin first got her, she wept until the bosom of her dress was drenched with tears. But when she came to the royal residence, shared with the Duke his luxurious couch, and ate rich food, she repented of having wept. How then do I know but that the dead may repent of having previously clung to life?"Those who dream of the banquet, wake to lamentation and sorrow. Those who dream of lamentation and sorrow wake to join the hunt.While they dream, they do not know that they are dreaming. Some will even interpret the very dream they are dreaming; and only when they awake do they know it was a dream. By and by comes the great awakening, and then we find out that this life is really a great dream. Fools think they are awake now, and flatter themselves they know -- this one is a prince, and that one is a shepherd. What narrowness of mind! Confucius and you are both dreams; and I who say you are dreams -- I am but a dream myself. This is a paradox. Tomorrow a Sage may arise to explain it; but that tomorrow will not be until ten thousand generations have gone by. Yet you may meet him around the corner."Granting that you and I argue. If you get the better of me, and not I of you, are you necessarily right and I wrong? Or if I get the better of you and not you of me, am I necessarily right and you wrong? Or are we both partly right and partly wrong? Or are we both wholly right and wholly wrong? You and I cannot know this, and consequently we all live in darkness."Whom shall I ask as arbiter between us? If I ask someone who takes your view, he will side with you. How can such a one arbitrate between us? If I ask someone who takes my view, he will side with me. How can such a one arbitrate between us? If I ask someone who differs from both of us, he will be equally unable to decide between us, since he differs from both of us. And if I ask someone who agrees with both of us, he will be equally unable to decide between us, since he agrees with both of us. Since then you and I and other men cannot decide, how can we depend upon another? The words of arguments are all relative; if we wish to reach the absolute, we must harmonize them by means of the unity ofGod, and follow their natural evolution, so that we may complete our allotted span of life."But what is it to harmonize them by means of the unity of God? It is this. The right may not be really right. What appears so may not be really so. Even if what is right is really right, wherein it differs from wrong cannot be made plain by argument. Even if what appears so is really so, wherein it differs from what is not so also cannot be made plain by argument. "Take no heed of time nor of right and wrong. Passing into the realm of the Infinite, take your final rest therein."The Penumbra said to the Umbra, "At one moment you move: at another you are at rest. At one moment you sit down: at another you get up. Why this instability of purpose?""Perhaps I depend," replied the Umbra, "upon something which causes me to do as I do; and perhaps that something depends in turn upon something else which causes it to do as it does. Or perhaps my dependence is like (the unconscious movements) of a snake's scales orof a cicada's wings. How can I tell why I do one thing, or why I do not do another?"Once upon a time, I, Chuang Chou (18), dreamt I was a butterfly, fluttering hither and thither, to all intents and purposes a butterfly. I was conscious only of my happiness as a butterfly, unaware that I was Chou. Soon I awaked, and there I was, veritably myself again. Now I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man. Between a man and abutterfly there is necessarily a distinction. The transition is called the transformation of material。

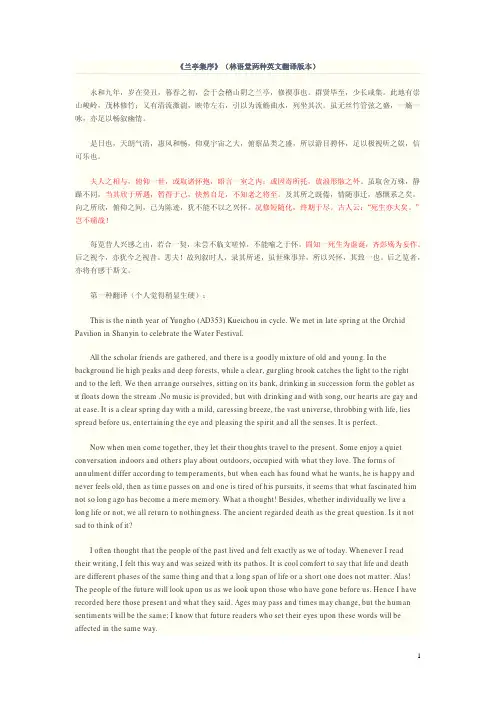

《兰亭集序》(林语堂两种英文翻译版本)永和九年,岁在癸丑,暮春之初,会于会稽山阴之兰亭,修禊事也。

群贤毕至,少长咸集。

此地有崇山峻岭,茂林修竹;又有清流激湍,映带左右,引以为流觞曲水,列坐其次。

虽无丝竹管弦之盛,一觞一咏,亦足以畅叙幽情。

是日也,天朗气清,惠风和畅,仰观宇宙之大,俯察品类之盛,所以游目骋怀,足以极视听之娱,信可乐也。

夫人之相与,俯仰一世,或取诸怀抱,晤言一室之内;或因寄所托,放浪形骸之外。

虽取舍万殊,静躁不同,当其欣于所遇,暂得于己,快然自足,不知老之将至。

及其所之既倦,情随事迁,感慨系之矣。

向之所欣,俯仰之间,已为陈迹,犹不能不以之兴怀。

况修短随化,终期于尽。

古人云:“死生亦大矣。

”岂不痛哉!每览昔人兴感之由,若合一契,未尝不临文嗟悼,不能喻之于怀。

固知一死生为虚诞,齐彭殇为妄作。

后之视今,亦犹今之视昔。

悲夫!故列叙时人,录其所述,虽世殊事异,所以兴怀,其致一也。

后之览者,亦将有感于斯文。

第一种翻译(个人觉得稍显生硬):This is the ninth year of Yungho (AD353) Kueichou in cycle. We met in late spring at the Orchid Pavilion in Shanyin to celebrate the Water Festival.All the scholar friends are gathered, and there is a goodly mixture of old and young. In the background lie high peaks and deep forests, while a clear, gurgling brook catches the light to the right and to the left. We then arrange ourselves, sitting on its bank, drinking in succession form the goblet as it floats down the stream .No music is provided, but with drinking and with song, our hearts are gay and at ease. It is a clear spring day with a mild, caressing breeze, the vast universe, throbbing with life, lies spread before us, entertaining the eye and pleasing the spirit and all the senses. It is perfect.Now when men come together, they let their thoughts travel to the present. Some enjoy a quiet conversation indoors and others play about outdoors, occupied with what they love. The forms of annulment differ according to temperaments, but when each has found what he wants, he is happy and never feels old, then as time passes on and one is tired of his pursuits, it seems that what fascinated him not so long ago has become a mere memory. What a thought! Besides, whether individually we live a long life or not, we all return to nothingness. The ancient regarded death as the great question. Is it not sad to think of it?I often thought that the people of the past lived and felt exactly as we of today. Whenever I read their writing, I felt this way and was seized with its pathos. It is cool comfort to say that life and death are different phases of the same thing and that a long span of life or a short one does not matter. Alas! The people of the future will look upon us as we look upon those who have gone before us. Hence I have recorded here those present and what they said. Ages may pass and times may change, but the human sentiments will be the same; I know that future readers who set their eyes upon these words will be affected in the same way.下面是第二种翻译(这个版本可能更好):The Orchid PavilionIn the ninth year of the reign Yungho[A.D. 353] in the beginning of late spring we met at the Orchid Pavilion in Shanyin of Kweich'i for the Water Festival, to wash away the evil spirits.Here are gathered all the illustrious persons and assembled both the old and the young. Here aretall mountains and majestic peaks, trees with thick foliage and tall bamboos. Here are also clear streams and gurgling rapids, catching one's eye from the right and left. We group ourselves in order, sitting by the waterside, and drinking in succession from a cup floating down the curving stream; and although there is no music from string and wood-wind instruments, yet with alternate singing and drinking, we are well disposed to thoroughly enjoy a quiet intimate conversation.Today the sky is clear, the air is fresh and the kind breeze is mild. Truly enjoyable it is sit to watch the immense universe above and the myriad things below, traveling over the entire landscape with our eyes and allowing our sentiments to roam about at will, thus exhausting the pleasures of the eye and the ear.Now when people gather together to surmise life itself, some sit and talk and unburden their thoughts in the intimacy of a room, and some, overcome by a sentiment, soar forth into a world beyond bodily realities. Although we select our pleasures according to our inclinations—some noisy and rowdy, and others quiet and sedate—yet when we have found that which pleases us, we are all happy and contented, to the extent of forgetting that we are growing old. And then, when satiety follows satisfaction, and with the change of circumstances, change also our whims and desires, there then arises a feeling of poignant regret. In the twinkling of an eye, the objects of our former pleasures have become things of the past, still compelling in us moods of regretful memory. Furthermore, although our lives may be long or short, eventually we all end in nothingness. "Great indeed are life and death", said the ancients. Ah! What sadness!I often study the joys and regrets of the ancient people, and as I lean over their writings and see that they were moved exactly as ourselves, I am often overcome by a feeling of sadness and compassion, and would like to make those things clear to me. Well I know it is a lie to say that life and death are the same thing, and that longevity and early death make no difference! Alas! As we of the present look upon those of the past, so will posterity look upon our present selves. Therefore, have I put down a sketch of these contemporaries and their sayings at this feast, and although time and circumstances may change, the way they will evoke our moods of happiness and regret will remain the same. What will future readers feel when they cast their eyes upon this writing.。

林语堂《吾国与吾民》自序(中英文互译)林语堂(1895~1976),福建龙溪(今漳州)人,原名和乐,后改玉堂,又改语堂,中国现代著名作家、学者、翻译家、语言学家。

早年留学美国、德国,获哈佛大学文学硕士、莱比锡大学语言学博士。

回国后在清华大学、北京大学、厦门大学任教。

1954年赴新加坡筹建南洋大学,任校长。

曾任联合国教科文组织美术与文学主任、国际笔会副会长等职。

林语堂于1940年和1950年先后两度获得诺贝尔文学奖提名。

曾创办《论语》《人间世》《宇宙风》等刊物,作品包括小说《京华烟云》《啼笑皆非》、散文和杂文文集《人生的盛宴》《生活的艺术》及译著《东坡诗文选》《浮生六记》等。

PrefaceMy Country and My People《吾国与吾民》自序In this book I have tried only to communicate my opinions, which I have arrived at after some long and painful thoughts and reading and introspection. I have not tried to enter into arguments or prove my different theses, but I will stand justified or condemned by this book, as Confucius once said of his Spring and Autumn Annals. China is too big a country, and her national life has too many facets,for her not to be open to the most diverse and contradictory interpretations. And I shall always be able to assist with very convenient material anyone who wishes to hold opposite theses. But truth is truth and will overcome clever human opinions. It is given to man only at rare moments to perceive the truth, and it is these moments of perception that will survive, and not individual opinions. Therefore, the most formidable marshaling of evidence can often lead one to conclusions which are mere learned nonsense. For the presentation of such perceptions, one needs a simpler, which is really a subtler, style. For truth can never be proved; it can only be hinted at.在这一本书里头,我只想发表我自己的意见,这是我经过长时间的苦思苦读和自我省察所收获的,我不欲尝试与人论辩,亦不欲证定我的各项论题,但是我将接受一切批评。

1.桃花源记——陶渊明The Peach Colony (translated by Lin Yutang 林语堂)晋太元中,武陵人捕鱼为业,缘溪行,忘路之远近。

忽逢桃花林,夹岸数百步,中无杂树,芳草鲜美,落英缤纷;渔人甚异之。

复前行,欲穷其林。

林尽水源,便得一山。

山有小口,仿佛若有光,便舍船,从口入。

初极狭,才通人;复行数十步,豁然开朗。

During the reign of Taiyuan of Chin, there was a fisherman of Wuling. One day he was walking along a bank. After having gone a certain distance, he suddenly came upon a peach grove which extended along the bank for about a hundred yards. He noticed with surprise that the grove had a magic effect, so singularly free from the usual mingling of brushwood, while the beautifully grassy ground was covered with its rose petals. He went further to explore, and when he came to the end of the grove, he saw a spring which came from a cave in the hill, Having noticed that there seemed to be a weak light in the cave, he tied up his boat and decided to go in and explore. At first the opening was very narrow, barely wide enough for one person to go in. After a dozen steps, it opened into a flood of light.土地平旷,屋舍俨然。

林语堂《记承天寺夜游》译文评析——兼论关联性语境融合理论与翻译批评原文:元丰六年十月十二日夜,解衣欲睡,月色入户,欣然起行。

念无与为乐者,遂至承天寺,寻张怀民,怀民未寝,相与步中庭。

庭下如积水空明,水中藻荇交横,盖竹柏影也。

何夜无月,何处无松柏,但少闲人如吾两人者耳。

译文:元丰六年十月十二日,晚上。

解开衣服想睡觉时,月光从窗口射进来,我愉快地起来行走。

想到没有可与自己一起游乐的人,于是到承天寺,找张怀民。

张怀民也没有睡觉,我们在庭院中散步。

庭院中的月光宛如一泓积水那样清澈透明,水中藻、荇纵横交叉,都是绿竹和翠柏的影子。

哪夜没有月光,哪里没有绿竹和翠柏,但缺少像我两个这样的闲人。

赏析:《记承天寺夜游》是一篇小品文。

所谓小品文,顾名思义就是内容短小(本文只有84个字),但韵味深长,需要用心品味的文章。

借用一句广告词来形容:“简约而不简单”,简约的内容里有着不简单的内涵,含义深刻隽永,回味无穷。

一、明月朗照无眠夜欣然起行寻超脱“元丰六年十月十二日夜,解衣欲睡,月色入户,欣然起行”。

时值冬初,长江边的小城黄州已是寒气袭人,苏轼本已解衣欲睡,准备就寝。

可是今晚明朗的月色入户,苏轼禁不住“欣然起行”。

苏轼是发现今晚的月色可爱吗?那他为什么先要“解衣欲睡”?为什么不早早做好赏月的准备?如果是“解衣欲睡”,为什么又要“欣然起行”?很显然,这一矛盾的动作正是苏轼内心矛盾的外在体现。

“欣然起行”应该只是苏轼夜不成寐的一种解脱方式。

明朗的月色、寒冷的冬夜、孤寂的身影,往往更能勾起那些想忘掉却无法忘掉的往事,更能想起那些想逃避却无法逃避的往事。

这样的夜晚,想起这样的事情,任何人都难以入眠。

苏轼自然难眠:记得当今圣上神宗的祖父仁宗皇帝初得苏轼、苏辙之日,曾曰:“吾今为子孙得太平宰相两人,惜吾不及用也。

”经历了两代皇帝,可是时至今日,苏轼不仅没有当上宰相,不能为朝廷大显身手,甚至连自家性命差点枉送!他实在想不通,为什么王安石变法这么十万火急,这么大刀阔斧,全然不顾社会的承受能力?放慢一点速度,先团结好人心,选用一批贤良,缓缓图之岂不是更稳妥、更能收到实效吗?……往事如烟,如今却一幕幕、一桩桩展现在眼前。