Katz v. United States 美国关于搜查

- 格式:docx

- 大小:37.16 KB

- 文档页数:12

美利坚合众国宪法第四条修正案(英语:Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution)是美国权利法案的一部分,旨在禁止无理搜查和扣押,并要求搜查和扣押状的发出有相当理由的支持。

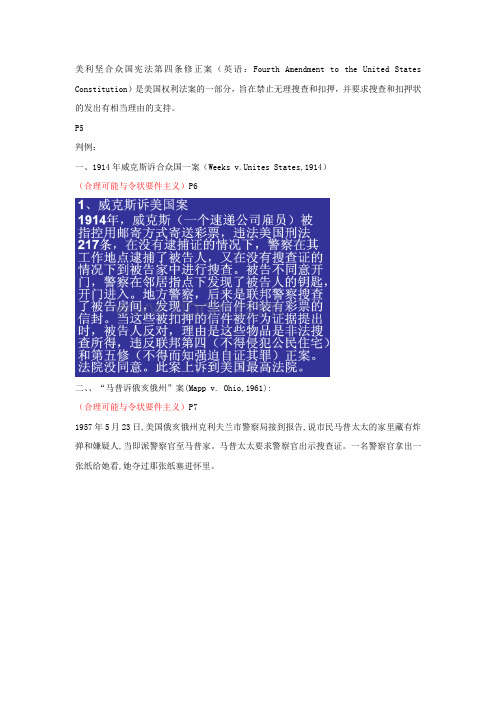

P5判例:一、1914年威克斯诉合众国一案(Weeks v.Unites States,1914)(合理可能与令状要件主义)P6二、、“马普诉俄亥俄州”案(Mapp v. Ohio,1961):(合理可能与令状要件主义)P71957年5月23日,美国俄亥俄州克利夫兰市警察局接到报告,说市民马普太太的家里藏有炸弹和嫌疑人,当即派警察官至马普家。

马普太太要求警察官出示搜查证。

一名警察官拿出一张纸给她看,她夺过那张纸塞进怀里。

三、在1984年的奥利弗诉美国案(英语:Oliver v. United States)(裸视原则)中[89],警方没有搜查令,也未经当事人许可并无视了“不得侵入”的警告标语和栅栏擅自进入嫌疑人的土地进行搜查,最终在数百英尺外发现了一片大麻地。

但最高法院认为这是一块开阔地,一个理性的人不会对一个露天场所存在全理的隐私预期[90],所以警方有理由相信其行为不会侵犯任何人的隐私,搜查是合宪的。

四、特里诉俄亥俄州案(Terry v. Ohio) (特里式截停规则)(合理可能与令状要件主义)1968年的特里诉俄亥俄州案(英语:Terry v. Ohio),执法人员可以在特定情况下因怀疑犯罪活动正在发生的合理理由而进行无证搜查。

最高法院在该判判决中认为,当一位警官发现“异常行为”,让他有合理理由相信“犯罪活动可能正在进行”,认为可疑人员有可能持有武器并且会对警官或他人构成威胁,那么警官可以对该人进行搜身来确定他是否持有武器[43]。

警官必须要对这类搜身行为给出具体而明晰的事实和理由来合理化自己的行为[44]。

俄亥俄州克里弗兰市一便衣侦探一天在街上巡逻,发现有两个年轻人站在一家商店前,从窗户往里张望,然后就走开了,过了一会儿,两人又回到商店前,像上次一样往里张望,并不时地低声地商量着什么,如此反复十余次。

商界论坛经法视点・236 ・论美国汽车搜查制度中的令状例外王若曦作者简介:王若曦,硕士研究生,四川大学法学院,法律硕士(法学)专业。

摘 要:美国刑事侦查中对待搜查一向要求要有相关令状,汽车搜查也不例外。

汽车搜查遵循令状原则,但是在1925年美国确立了汽车搜查的令状例外,即是汽车搜查例外。

汽车搜查例外有机动性理论以及较少隐私期待理论作为理论支撑,作为汽车搜查的特殊制度,其使无证搜查汽车合法化。

我国目前对汽车搜查以及汽车搜查例外的相关制度缺乏法律规定,美国的这一制度应当给我们以一定的借鉴意义。

关键词:令状;汽车搜查例外;机动性;较少隐私期待令状原则是美国刑事侦查阶段要进行搜查的一般原则,根据美国宪法第四修正案,在搜查公民人身住所等时应当出具相关令状。

在令状原则下,美国汽车搜查制度包括两个部分,有证汽车搜查和无证汽车搜查。

有证汽车搜查遵循一般搜查的规则,需要有搜查令,而无证汽车搜查也被称为“汽车例外”,是一种在无令状状态下对汽车进行搜查的制度。

一、美国汽车搜查例外的规则无证汽车搜查是有证汽车搜查的例外情况,是令状原则之下的汽车搜查例外。

1925年,美国最高法院在卡罗尔案(Carrollv.UnitedStates)①中第一次阐述了令状原则之下的汽车搜查例外。

这是一个美国禁酒令时期的案例。

在本案中,执法人员在高速公路巡逻时拦下有充分理由相信载有烈酒的汽车并在没有搜查令的情况下搜查了该车,发现了里面装的烈酒,对其进行了扣押。

最高法院在本案中支持了特殊情况下警察的无令状的搜查。

汽车搜查例外的规则包括“当场”实施搜查和“离开现场后的”搜查。

早期的汽车搜查例外要求具有紧急情形,如车辆可能马上开走警察很难再找到它。

但是,现行法规定,“汽车搜查例外不以存在紧急情形为条件。

”现在,只要具备汽车可以马上开走并且有合理根据相信汽车里放有违禁品(或依法允许扣押的证据),那么允许警察立即对该车辆进行搜查。

②关于“离开现场后的”搜查,这是指警察在汽车离开现场后不久对其进行无证搜查是合法的,同时,如果警察在将汽车扣押后不立即进行搜查而是在一个合理期限内进行无证搜查那也是合法的。

美国“搜查”规则的历史变迁【摘要】随着人权思想和隐私理念的不断增长,如何定义“搜查”行为成为了任何司法体系都需要关注的重要问题,美国联邦最高法院正是通过一系列的判例来构建起美国的“搜查”规则。

文章即对美国联邦最高法院相关案例进行归纳并从中指出其理论阐述的思路。

【关键词】美国;搜查;规则中图分类号:D99 文献标识码:A 文章编号:1006-0278(2013)08-127-01一、美国联邦最高法院关于第四修正案中“搜查”规则的主要判例博伊德案(116 U.8.616 1886)确立了以“财产权”为中心的第四修正案分析方法,警察的行为是否构成“搜查”取决于该行为是否对“人身、住宅、文件和财产”进行了物理性侵害。

奥穆斯泰德案(277 U.S.438 1928)严格适用了财产权,侵害分析法。

明确指出宪法只保护嫌疑人“人身、住宅、文件和财产”不受物理性侵入或侵害,且超越上述范围的领域不受宪法的保护。

卡兹案(389 U.S.347 1967)推翻了奥穆斯泰德案,宣布财产权/侵害分析法“不再是支配性的分析方法”,确立了以“隐私权”为中心的第四修正案分析方法。

提出了“合理的隐私期待”标准。

怀特案(4叭U.S.745 1971)重新论述了虚假朋友理论:个人对于交谈人不会向警察报告其谈话内容,不享有合理的隐私期待,因而虚假朋友不构成搜查行为。

史密斯案(442 U.S.735 1979)认为电话使用人在拨电话号码时缺乏主观上的隐私权期待,同时与“虚假朋友”理论一致,对于自愿提交第三方的信息,个人不再享有合理的隐私权期待。

杰克布森案(466 U.S.109 1984)再次确认仅仅在于揭示某物品是否属于违禁物品的行为,没有损害任何合法的隐私利益,因而不构成“搜查”。

科诺茨案(460 U.S.276 1983)和卡罗案(468 U.S.7051984)认为电子追踪装置在公共领域所反映的信息通过警察的视觉监控同样能够获得,因而被监控人不享有隐私权期待。

美国海关有多大权力?如何才知道越权搜查?一是美国宪法第四修正案可保护旅客免受不正当搜查和没收,但在国际机场或其它海关口入境美国,以及在美边境100飞行英里范围内的其它任何地点,这一保护都会削弱。

二是根据美国现行联邦法律规定和现有法庭裁决,美国海关人士在不出示搜查证情况下,对任何入境美国的旅客进行人身和行李搜查,有权询问旅客公民和移民身份,搜查入境文件。

但在要求体腔搜查时,海关需有一定证据怀疑此人有犯罪活动嫌疑。

三是美国现行联邦法规定,海关有权搜查旅客的手机、电脑、光盘、磁盘、驱动、磁带和其它电脑通信设备、照相机、音乐或媒体播放设备及其它电子或数据设备,安检人员搜查电子设备时,屋内必须有主管监督,必要时当着当事人的面进行搜查,涉及国家安全、执法或其它行动考虑时除外(如涉及敏感执法手段或影响调查过程时,不能当着旅客的面进行搜查)。

电子设备搜查CBP表示,无论海关是否怀疑当事人的电子设备涉嫌犯罪活动,海关都有权搜查。

主管不在场时,海关官员也有权没收旅客的电子设备或电子设备上的信息拷贝以进行仔细搜查,这类没收通常不超过5天,但海关可申请延长至1周,如搜查结果证实被没收内容不涉嫌犯罪,CBP会销毁没收的拷贝文件,归回电子设备。

当事人无具体犯罪嫌疑,海关是否有权搜查电子设备?在这一点上,美国高等法庭尚无直接裁决,但2013年美国联邦第九巡回上诉法院(CANC,仅次于高院)的一项多数裁决提供了一定参考。

这项裁决规定,海关对电子设备一般性搜查(cursory search),不需要什么具体犯罪嫌疑。

但对电子设备进行更深入搜查,如用电脑软件分析硬盘数据,访问删除文件和搜索历史记录、密码保护文件和其它隐私文件时,海关必须有正当的犯罪嫌疑理由,不能仅凭感觉。

这一裁决只适用于加州、亚利桑那州、内华达州、俄勒冈州和华盛顿州等美西9个州,CBP是否将之扩大应用到其它州则不得而知。

CBP对电子设备搜查规定最近一次修订是在2009年,目前修订还在审查中,具体什么时候修订完毕目前还未宣布。

论美国联邦最高法院对美国警察搜查权的调控——以非法证据排除规则的演变为视角2007年7月第4期北京人民警察学院JournalofBeijingPeople'SPoliceCollegeJu1..2007NO.4【法学与法律适用】论美国联邦最高法院对美国警察搜查权的调控——以非法证据排除规则的演变为视角刘海鸥(北京人民警察学院,北京102202)摘要:二十世纪六十年代以来,非法证据排除规则被美国联邦最高法院广泛使用,成为保护人民自由权利,限制警察非法搜查的尚方宝剑.但随着恐怖主义,毒品犯罪等的增多,加强警察执法权力,适当限制人民自由,成为联邦最高法院主导性理念.非法证据排除规则也随之产生了松动.非法证据排除规则对美国警察搜查权的影响历程,反映了联邦最高法院在保持个人利益与社会利益,自由与秩序之间的平衡做出的不懈努力.关键词:非法证据排除规则;警察;非法搜查中图分类号:D93文献标识码:A文章编号:1672—4127(2007)04—0016—04为有效履行控制犯罪,维护民众生命财产安全的职责,世界各国法律均赋与警察广泛的执法权力, 包括逮捕权,搜查权,审问嫌疑人权等.但警察如何行使执法权直接涉及人民的自由与权利,法律又必须对警察执法权的行使进行相应的程序限制,必须在警察有效控制犯罪,维护社会秩序与执法过程中不妨害人民合法权利之间寻找一个平衡点.在美国,人民在刑事程序中享有的宪法权利主要规定在宪法第四,五,六,八修正案中,而这些修正案多为程序性规定.在这些修正案中,与警察权力关联最大的是第四修正案有关人民不受不正当搜查与扣押的权利和第五修正案有关人民不得被强迫自证其罪的权利.其中,宪法第四条修正案规定:"人民的人身,住宅,文件和财产不受无理搜查和扣押的权利,不得侵犯.除依据可能成立的理由,以宣誓或代誓宣言保证,并详细说明搜查地点和扣押的人或物,不得发出搜查和扣押状."美国联邦最高法院基于司法审查权,通过一系列裁决,就该条修正案做过许多解释, 对警察执法权作出具体限制.其中,非法证据排除规则的确立,发展,便是联邦最高法院调控警察搜查权,保障人民自由权利的一项重要举措.一,非法证据排除规则对美国联邦警察搜查权的限制——规则的确立如何保证警察不在执法过程中侵犯人民的宪法权利?尤其是不受无理搜查和扣押的权利?在美国独立后的一百多年里,不论是普通法还是早期的宪法中,都没有任何要求在审判中排除执法人员以某种非法的方法所获得的证据的法令.大法官本杰明?卡多佐(BenjaminCardozo)解释出现这种情况的原因:法庭不愿意仅由于警察不自觉所犯的错误而使罪犯逍遥法外,而且法官也不情愿冒险去解释那些间接的,有时又是非常复杂的有关警察对证据收集方法的司法问题,而宁愿解决刑事犯罪这一主要问题.1914年后这种状态才有所改变._1在1914年威克斯诉美国(Weeksv.U.S.)一案中,联邦最高法院首次提出了非法证据排除规则.按照该规则,警察在搜查时如违反法律,联邦法院在审判中不得引用非法搜查所取得的证据,不能以此给被告人定罪.威克斯诉美国一案的基本案情是:威克斯是美国密苏里州堪萨斯城的一家快递公司的雇员.1911年,他被当地一警察逮捕,但是该警察没有携带逮捕证.其他警察来到威克斯的住所,通过一个邻居了解钥匙存放处.拿到钥匙后,警察搜查了威克斯的住所,带走了许多文件和物品,然后交给了检察官.就在同一天,警察和公诉人再次搜查了被告的住所,拿走一些信件和信封.无论是警察还是公诉人都没有搜查证.基于从威克斯住所取得的证据,威克斯因为非法输送赌博物品被提起公诉.威克斯要求返还从自己住所搜走的物品,并反对将这些物品作为证据使用.理由是警方是在没有搜查证的情况下获得的这些文件,并且擅自闯入他的家中,侵犯了宪法第四修正案及第五修正案规定的公民权利.该抗辩被联邦地方法院驳回.收稿日期:2007—06—13作者简介:刘海鸥(1968一),女,吉林人,北京人民警察学院副教授,中国人民大学法学博士.?l6?刘海鸥:论美国联邦最高法院对美国警察搜查权的调控——以非法证据排除规则的演变为视角后来联邦最高法院撤销了联邦地方法院的判决,将该案发回重审.最高法院在裁决中宣布,联邦法院在审判中不得采用非法搜查取得的证据.大法官威廉?德(wi11iamDay)的法庭意见认为,"如果能够以这种方式扣押这些信件和私人文件并将其作为指控被告违法的证据的话,那么,宪法第四修正案所保护的人民不受非法搜查和扣押的权利就形同虚设.如此,还不如从宪法中将其删除为好.""如果不是要公然地违抗宪法",法庭就不会"以司法判决的方式来认可一个对宪法禁止性规范的明显疏忽","政府公务员以执行公务为幌子,从被告的住宅拿走那些能否成为证据尚存疑问的信件,直接侵犯了被告的宪法权利.……法院应该退还被告的信件,保有这些信件并允许将它们作为法庭证据用于审判,是在犯一个后果严重的错误."显然,联邦最高法院是想通过确立非法证据排除规则来管制警察的非法搜查行为,以维护人民的宪法权利.但是,在威克斯案中进行非法搜查的是联邦警察,最高法院在此案中确立的排除非法证据原则因此只适用于联邦警察,不适用于州和地方警察.此后40多年中,最高法院一直没要求各州也采用排除规则.在沃尔夫诉科罗拉多州(Wo1fv.PeopleofTheStateofCo1o)一案中,科罗拉多州的警察对沃尔夫进行了非法搜查得到了有罪的证据.在法庭审理中,根据这些证据,被告人被判有罪.被告人不服,一直上诉到联邦最高法院.州法院和联邦最高法院对该案中定罪的证据是非法取得的这个事实没有争议,但违反了联邦宪法第四修正案取得的证据能否在州法院的审判中予以排除是个值得探讨的问题.最后,联邦最高法院没有强制将排除非法证据原则扩大到各州,是否实行非法证据的排除规则由各州自行决定.但是,联邦最高法院在该案中全体一致同意,第十四条修正案确定禁止各州采取不合理的搜查和逮捕.法兰克福特(FelixFrank一{urter)大法官在法庭意见中指出,保护个人自由免受警察任意侵犯是宪法修正案的核心,是自由社会的核心价值,它体现在"有秩序的自由"这个概念中, 通过正当程序对国家权力进行制衡.二,非法证据排除规则对州,地方警察非法搜查权的制约——规则的发展二十世纪六十年代,美国联邦最高法院由首席大法官沃伦为代表的持自由主义观点的法官所主导,它们倾向于强调保护人民自由权利的重要性,以民权,自由主义思想为主导,主张对警察执法权作较为严格的限制.在1961年的马普诉俄亥俄州案(Mappv.Ohio)中,最高法院裁定维克斯案的排除规则为联邦宪法原则,适用于各州的刑事诉讼中.马普诉俄亥俄州案的基本情况如下:1957年5月23日,警察怀疑马普太太家窝藏一个爆炸案的嫌疑犯,3个克里夫兰市的警官敲马普太太家的家门并要求进屋去.因为警察没有搜查证,马普和律师通电话后,拒绝警察人门.警察不死心,几个小时后,它们第二次来到马普太太家,这次他们不等马普太太来应门便破门而人.站在楼梯半道的马普太太要看搜查证,一名警察从El袋里掏出一张纸谎称是搜查证.马普太太抢过那张纸,收进裙子.经过一番争夺,警察抢回那张纸,并因为马普太太的挑衅行为,警察铐住了她.之后,警察对马普太太家进行了全面搜查.警察没有找到逃犯,但在地下室搜到了淫秽物品,马普太太因这些物品而被捕.马普太太被指控窝藏淫秽物品.在法庭上,检察官企图证明这些物品是马普太太的.审判中发现,警察根本没有搜查马普太太家的搜查令.警察在既无可能理由又无搜查证的情况下强行搜查,显然是非法的.但当时俄亥俄州没有采用非法证据排除规则,警察搜查到的淫秽物品仍然用作给马普太太定罪的证据,马普太太被判有罪.判决后,马普太太不服,诉至俄亥俄州最高法院,声称淫秽物品不属于她,警察取证过程是违法的.但俄亥俄州最高法院驳回了她的上诉,认定在法庭出示的证据没有问题.马普太太最终上诉到联邦最高法院.联邦最高法院撤销了俄亥俄州最高法院的判决.克拉克(JohnClarke)大法官的法庭意见认为:维克斯诉美国案的判决是第一次在联邦诉讼中澄清第四修正案禁止采用通过非法搜查和扣押所获得的证据.在沃尔夫诉科罗拉多州一案判决中,法庭不允许将排除规则的适用扩展到州刑事程序中,是由于当时有三分之二的州反对运用排除规则作为对非法搜查和扣押的惩罚.然而自沃尔夫案判决后,已经有超过半数的州通过立法或者是判例,全面或部分地采用了排除规则.因此,联邦最高法院认为构成沃尔夫案件基础的关键性事实问题不再起决定作用了.既然在沃尔夫案判决中表明了第四修正案的隐私权通过第十四修正案也可以适用于州,那么,就如同非法证据排除规则能对抗联邦政府的非法搜查行为一样,各州也应使用非法证据排除规则来保护人民的隐私权.针对部分持保守主义观念大法官提出的法庭异议,法庭多数意见认为,适用排除规则的确会在一些案件中产生犯人免受处罚的结果,但是,"这是法律自身所指出的,有必要考虑到司法必须完整的训诫(imperativeofjudicialintegrity)".至此,最高法院通过马普案将排除非法证据规则的适用成功地推向全国.此后,不论是联邦警察,州警察,还是地方警察,只要进行了非法搜查,他们在搜查中取得证据都要按照排除规则予以排除.最高法院设立排除规则的目的是为了以此来防止警察进行非法搜查.在实践中,排除规则的适用对警察的执法活动确实起到了警示作用.为避免所收集的?]7?刘海鸥:论美国联邦最高法院对美国警察搜查权的调控——以非法证据排除规则的演变为视角证据被排除,劳而无功,各警局普遍采取措施,提高警察依法执法意识.尽管如此,对排除规则的批评依然广泛存在.联邦最高法院持保守主义观点的大法官认为,适用排除规则会削弱刑事司法机构控制犯罪的能力.警察固然不应以非法手段取得证据,但法院也不应因警察的过失而放纵罪犯.使用排除规则会使事实上有罪的人逃避法律制裁._2]2一些美国学者认为,排除规则并不能在多大程度上解决警察侵犯公民宪法权利的问题.因为,对那些在非法搜查中没有被搜到犯罪证据的人来说,排除规则并不能为他们提供任何救济.同时,在犯罪率居高不下时,有些警察机构会采用激进执法手段来达到迅速降低犯罪率的效果.这种激进执法措施虽然可以吓跑犯罪分子,也肯定会使许多守法居民遭到无理搜查.警察采取的这种激进执法手段完全置公民的宪法权利于不顾, 但由于警察的直接目的只是想吓跑犯罪分子,并不想将犯罪嫌疑人送上法庭,排除规则并无助于防止这种情况下的警察违法行为.从根本上促使警察遵纪守法的途径不是非法证据排除规则,而是由警察机构加强对警察的教育和训练,通过行政手段处罚有违法行为的警察.对侵犯嫌疑人权利的警察提出刑事起诉也是防止和减少警察侵犯公民权利事件发生的途径.可见,美国法律界对排除规则的争论,集中在排除规则抑制警察非法搜查的效果及社会因此付出的代价等方面.从实质上来说,反映了在个人权利自由与社会秩序之间寻求平衡点的努力.三,非法证据排除规则适用的"例外"——规则的松动由于美国联邦最高法院至高无上的司法审查权,美国的法治进程很大程度上是由最高法院通过各种判例解释宪法来推动的.正如大法官查尔斯? 休斯(CharlesEvensHughes)所言:"我们生活在宪法之下,但这个宪法是什么意思,却是由法官们说了算."虽然最高法院竭力追求政治中立,强调不偏不倚,但事实上很难完全做到.大法官本身存在着不同的司法观念,加之总统提名和参议院批准过程中存在强烈的党派色彩,以及政治思潮的变迁,社会舆论的转向,都对法庭多数意见的形成构成直接或间接的影响.1969年沃伦大法官退休后,保守的尼克松总统任命联邦哥伦比亚特区上诉法院保守派法官伯格(WarrenBurger)出任联邦最高法院首席大法官,联邦最高法院大法官构成发生了较大变化,逐渐为持保守主义观点的法官所主导.这些大法官虽然没有推翻排除非法证据规则,但却通过一系列裁决, 对这一原则的适用作出了限制,设立了一些可不排除非法证据的例外,非法证据排除规则开始出现了一些松动.其中比较有影响的是1984年的两个判决,即美国诉里昂(U.S.v.Leon)一案确立的"善意?]8'的例外"及尼克斯诉威廉姆斯(Nixv.wi11iams)一案确立的"必将发现例外".美国诉里昂一案的基本案情是:1981年8月,基于一个告密者提供的线索,美国伯班克的警察开始对一宗毒品买卖案件进行调查,包括对里昂行动的监视.基于一份总结了警方侦查结果的宣誓书,警官准备了一份要求对里昂三处住所,汽车和其它财物发出搜查令的申请,几个副检察官审查了这份申请,一个地方法庭法官迅速发出了一份有效的搜查令.接下来的搜查发现了大量毒品和其他证据,里昂因此被指控毒品犯罪.里昂要求地方法院禁止使用依据搜查令搜查所获取的证据,地方法院同意了里昂的请求,认为宣誓书不足以成为逮捕的合理理由.尽管法院承认Rombach警官的行为具有"良好诚信",但是对地方政府认为第四条修正案的排除规则不适用依赖合理的,良好诚信基础上的搜查证所取得的证据观点持否定意见.地方政府上诉后,上诉法院维持了地方法院的判决.最后,政府将该案上诉到联邦最高法院.最高法院撤销了上诉法院对于该案的判决,裁定排除规则不适用此案.最高法院认为,在此案中适用排除规则无助防止警察进行非法搜查.适用排除规则是为了抑制警察的非法搜查行为,而不是为了惩罚法官错误发出搜查令的行为.如果法官发出的搜查令无效,但警察基于善意,相信搜查令是合法的,此时适用排除规则并不能起到防止警察非法搜查的作用.非法证据排除规则不能被用于阻碍那些执法官员在获得独立公正的地方治安官所签署的搜查令后,以合法行为所获得的证据的使用,尽管最后发现搜查令是无效的.联邦最高法院因此设立了非法证据排除规则的"善意例外"(goodfaithexception).这一例外的含义是,在搜查时如警察合理地,善意地相信所持搜查令为有效搜查令,即使事后发现该搜查令无效,警察依据该搜查令所查获的证据也不必作为非法证据予以排除.美国学者博登海默认为"善意例外"基于以下价值考虑:在不知道令状无效的情况下获取的证据的使用,比起社会要承担的实质价值来讲,只付出了侵犯第四修正案的小部分代价,因为有罪者获得自由对社会的危害更大._3最高法院同年在尼克斯诉威尼斯(Nixv.Wi1—1iams)一案中,确立了"必将发现例外"(Inevitable DiscoveryException).在该案中,最高法院虽然承认警察在被告人要求会见律师后以"基督徒葬礼"谈话的方式继续盘问被告人,侵犯了其宪法权利,但不同意将因此而获得的证据——被害人的尸体作为非法证据排除.最高法院指出,当被告带警察找到被害人尸体时,警察组织的搜索队已经很接近尸体被刘海鸥:论美国联邦最高法院对美国警察搜查权的调控——以非法证据排除规则的演变为视角遗弃的地点,即使被告没有将警察带到该地点,搜索队也会很快找到被害人的尸体.最高法院因此裁决,由于警察必将发现被害人尸体,该证据不必作为非法证据予以排除.许多事实证明,二十世纪七十年代以后,美国联邦最高法院的司法理念日趋保守.尤其是九十年代以来,随着恐怖主义及毒品犯罪的泛滥,刑事司法打击犯罪的功能被日益强化.最高法院也不再坚持非法证据排除规则是一项宪法原则,而认为它只是一项由法院制订的旨在防止警察非法行为的一般法律原则.最高法院解释说,法院必须兼顾适用此原则的社会效益和社会代价.适用该原则的社会效益是排除非法证据能起到防止警察以非法手段取证的作用,适用该原则的代价是排斥规则会使事实上有罪的人逃避法律制裁.法院必须全面考虑和平衡此原则的利与弊.当适用此原则的社会代价大于它的社会效益时,法院即可适用此原则的例外._2]非法证据排除规则例外的确立,表明美国联邦最高法院在适用这一规则态度上的松动.八十年代以后,美国社会各界意识到,必须用强有力的手段控制居高不下的犯罪率,赋予美国警察更多的执法权.在犯罪率持续增长的情况下,面对维护社会秩序和保障个人自由的两难抉择,维持社会秩序的价值日益受到重视,侧重于单一利益和价值追求的做法遭到质疑,进而表现出自由与秩序价值选择的平等对待趋势.非法证据排除规则"例外"的规定,使刑事诉讼控制犯罪的功能得到加强,注重了对秩序的维护.四,结束语适用非法证据排除规则是否大大降低了警察的破案率?排除规则的"例外"又是否大大方便了警察执法?不少人认为,无论是非法证据排除规则抑或是排除规则的"例外",对美国警察破案率的影响都微乎其微.因为,法院其实只是在极少案件的审判中使用排除规则.据估计,法院只是在1到2的刑事案件中使用非法证据排除规则排除证据,而且这些案件大多为毒品案件,法院很少在杀人案,强奸案等重大案件中使用排除规则.很显然,法官在重大刑事案件中都不愿看到因排除证据而使罪犯逃避法网.[.]然而,事实也表明,非法证据排除规则也促进了警察改革.美国警察机构通过改善征募,严格培训, 教育和监督管理,使警察对公民的自由价值理念有新的认识.同时,在执法实践中,已经逐渐自觉地以非法证据排除规则来约束执法行为.从长远来看,排除规则大大促进了警察机关形成保护人民自由权的警察文化.必须承认,世界上不存在尽善尽美的法律和制度.尤其是现代社会充斥着利益与价值观的多元化,任何制度和规则都只能审时度势,权衡利弊,在不同的利益和价值冲突之间寻找一种动态性平衡.尽管有了非法证据排除规则的例外,美国联邦最高法院至今还没有摒弃非法证据排除规则."9?11"以来,美国社会维护治安,打击恐怖主义的呼声日益高涨,包括警察机关在内的政府执法部门的权势也日益加强,牺牲公民权利的压力日益增大,联邦最高法院如何在新形势下保持个人利益与社会利益,自由与秩序之间的平衡,人们将拭目以待.参考文献:I-1-11-美]乔恩?R?华尔兹.刑事证据大全(第二版)I-M].何家弘,等,译.北京:中国人民公安大学出版社,2004:246.[2]马跃.美国刑事司法制度[M].北京:中国政法大学出版社,2004.[3]樊崇义,夏红.正当程序文献资料选编[C].北京:中国人民公安大学出版社,2004:101.责任编辑:谢昀OntheAmericanFederationoftheUnitedStatesSupreme CourtControllingtheSearchingRightofthePolice——f1.0mtheperspectiveoftheevolutionofrules concerningillegalevidenceexclusionLIUHai-ou(BeijingPeople'SPoliceCollege,Beijing102202,China)Abstract:Sincethe1960s,illegalevidenceexclusionrulesareextensivelyusedbytheUnited StatesFederalSupremeCourt,andhavebecomethemostpowerfultooltoprotectfreedomofpeopleandtolimitillegal policesearchandcharges.Butwiththeincreaseofterrorismanddrug-relatedcrimes,tostrengthenenforcementpowersofth epoliceandappropriatelyrestrict freedomofpeoplehasbecomedominantphilosophyofTheFederalSupremeCourt.Rulesco ncerningillegalevidenceexclusionalsogotloose.TheimpactoftheillegalevidenceexclusionrulesontheUnitedStatespolicesea rchingrightisreflectedintheeffortofthefedera1SupremeCourttomaintainthebalancebetweenpersonalandcommunity interests.orderandfreedom.Keywords:illegalevidenceexclusionrules;police;illegalsearch?]9?。

KATZ v. UNITED STATES389 U.S. 347 (1967)MR. JUSTICE STEWART delivered the opinion of the Court.(1)The petitioner was convicted in the District Court for the Southern District of California under an eight-count indictment charging him with transmitting wagering information by telephone from Los Angeles to Miami and Boston, in violation of a federal statute. 1 At trial the Government was permitted, over the petitioner's objection, to introduce evidence of the petitioner's end of telephone conversations, overheard by FBI agents who had attached an electronic listening and recording device to the outside of the public telephone booth from which he had placed his calls. In affirming his conviction, the Court of Appeals rejected the contention that the recordings had been obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment, [389 U.S. 347, 349] because "[t]here was no physical entrance into the area occupied by [the petitioner]." We granted certiorari in order to consider the constitutional questions thus presented.(2)The petitioner has phrased those questions as follows:"A. Whether a public telephone booth is a constitutionally protected area so thatevidence obtained by attaching an electronic listening recording device to the top ofsuch a booth is obtained in violation of the right to privacy of the user of the booth.[389 U.S. 347, 350]"B. Whether physical penetration of a constitutionally protected area is necessarybefore a search and seizure can be said to be violative of the Fourth Amendment tothe United States Constitution."We decline to adopt this formulation of the issues. In the first place, the correct solution of Fourth Amendment problems is not necessarily promoted by incantation of the phrase "constitutionally protected area." Secondly, the Fourth Amendment cannot be translated into a general constitutional "right to privacy." That Amendment protects individual privacy against certain kinds of governmental intrusion, but its protections go further, and often have nothing to do with privacy at all. Other provisions of the Constitution protect personal privacy from other forms of governmental invasion. But the protection of a person's general right to privacy --- his right to be let alone by other people --- is, like the [389 U.S. 347,351] protection of his property and of his very life, left largely to the law of the individual States.(3)Because of the misleading way the issues have been formulated, the parties have attached great significance to the characterization of the telephone booth from which the petitioner placed his calls. The petitioner has strenuously argued that the booth was a "constitutionally protected area." The Government has maintained with equal vigor that it was not. But this effort to decide whether or not a given "area," viewed in the abstract, is "constitutionally protected" deflects attention from the problem presented by this case. For the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places. What a person knowingly exposes to the public, even in his own home or office, is not a subject of Fourth Amendment protection. See Lewis v.United States, 385 U.S. 206, 210 ; United States v. Lee, 274 U.S. 559, 563 . But what he seeks to preserve as private, even in an area accessible to the public, may be constitutionally protected. [389 U.S. 347, 352] See Rios v. United States, 364 U.S. 253 ; Ex parte Jackson,96 U.S. 727, 733 .(4)The Government stresses the fact that the telephone booth from which the petitioner made his calls was constructed partly of glass, so that he was as visible after he entered it as he would have been if he had remained outside. But what he sought to exclude when he entered the booth was not the intruding eye - it was the uninvited ear. He did not shed his right to do so simply because he made his calls from a place where he might be seen. No less than an individual in a business office, in a friend's apartment, or in a taxicab, a person in a telephone booth may rely upon the protection of the Fourth Amendment. One who occupies it, shuts the door behind him, and pays the toll that permits him to place a call is surely entitled to assume that the words he utters into the mouthpiece will not be broadcast to the world. To read the Constitution more narrowly is to ignore the vital role that the public telephone has come to play in private communication.(5)The Government contends, however, that the activities of its agents in this case should not be tested by Fourth Amendment requirements, for the surveillance technique they employed involved no physical penetration of the telephone booth from which the petitioner placed his calls. It is true that the absence of such penetration was at one time thought to foreclose further Fourth Amendment inquiry, Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438, 457 , 464, 466; Goldman v. United States, 316 U.S. 129, 134 -136, for that Amendment was thought to limit only searches and seizures of tangible [389 U.S. 347, 353] property. But "[t]he premise that property interests control the right of the Government to search and seize has been discredited." Warden v. Hayden, 387 U.S. 294, 304 . Thus, although a closely divided Court supposed in Olmstead that surveillance without any trespass and without the seizure of any material object fell outside the ambit of the Constitution, we have since departed from the narrow view on which that decision rested. Indeed, we have expressly held that the Fourth Amendment governs not only the seizure of tangible items, but extends as well to the recording of oral statements, over-heard without any "technical trespass under . . . local property law." Silverman v. United States, 365 U.S. 505, 511 . Once this much is acknowledged, and once it is recognized that the Fourth Amendment protects people - and not simply "areas" - against unreasonable searches and seizures, it becomes clear that the reach of that Amendment cannot turn upon the presence or absence of a physical intrusion into any given enclosure.(6)We conclude that the underpinnings of Olmstead and Goldman have been so eroded by our subsequent decisions that the "trespass" doctrine there enunciated can no longer be regarded as controlling. The Government's activities in electronically listening to and recording the petitioner's words violated the privacy upon which he justifiably relied while using the telephone booth and thus constituted a "search and seizure" within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. The fact that the electronic device employed to achieve that end did not happen to penetrate the wall of the booth can have no constitutional significance. [389 U.S. 347, 354](7)The question remaining for decision, then, is whether the search and seizure conducted in this case complied with constitutional standards. In that regard, the Government's position is that its agents acted in an entirely defensible manner: They did not begin their electronic surveillance until investigation of the petitioner's activities had established a strong probability that he was using the telephone in question to transmit gambling information to persons in other States, in violation of federal law. Moreover, the surveillance was limited, both in scope and in duration, to the specific purpose of establishing the contents of the petitioner's unlawful telephonic communications. The agents confined their surveillance to the brief periods during which he used the telephone booth, and they took great care to overhear only the conversations of the petitioner himself.(8)Accepting this account of the Government's actions as accurate, it is clear that this surveillance was so narrowly circumscribed that a duly authorized magistrate, properly notified of the need for such investigation, specifically informed of the basis on which it was to proceed, and clearly apprised of the precise intrusion it would entail, could constitutionally have authorized, with appropriate safeguards, the very limited search and seizure that the Government asserts in fact took place. Only last Term we sustained the validity of [389 U.S. 347, 355] such an authorization, holding that, under sufficiently "precise and discriminate circumstances," a federal court may empower government agents to employ a concealed electronic device "for the narrow and particularized purpose of ascertaining the truth of the . . . allegations" of a "detailed factual affidavit alleging the commission of a specific criminal offense." Osborn v. United States, 385 U.S. 323, 329 -330. Discussing that holding, the Court in Berger v. New York, 388 U.S. 41 , said that "the order authorizing the use of the electronic device" in Osborn "afforded similar protections to those . . . of conventional warrants authorizing the seizure of tangible evidence." Through those protections, "no greater invasion of privacy was permitted than was necessary under the circumstances." Id., at 57. Here, too, a similar [389 U.S. 347, 356] judicial order could have accommodated "the legitimate needsof law enforcement" by authorizing the carefully limited use of electronic surveillance.(9)The Government urges that, because its agents relied upon the decisions in Olmstead and Goldman, and because they did no more here than they might properly have done with prior judicial sanction, we should retroactively validate their conduct. That we cannot do. It is apparent that the agents in this case acted with restraint. Yet the inescapable fact is that this restraint was imposed by the agents themselves, not by a judicial officer. They were not required, before commencing the search, to present their estimate of probable cause for detached scrutiny by a neutral magistrate. They were not compelled, during the conduct of the search itself, to observe precise limits established in advance by a specific court order. Nor were they directed, after the search had been completed, to notify the authorizing magistrate in detail of all that had been seized. In the absence of such safeguards, this Court has never sustained a search upon the sole ground that officers reasonably expected to find evidence of a particular crime and voluntarily confined their activities to the least intrusive [389 U.S. 347, 357] means consistent with that end. Searches conducted without warrants have been held unlawful "notwithstanding facts unquestionably showing probable cause," Agnello v. United States, 269 U.S. 20, 33 , for the Constitution requires "that the deliberate, impartial judgment of a judicial officer . . . be interposed between the citizen and the police . . . ." Wong Sun v.United States, 371 U.S. 471, 481 -482. "Over and again this Court has emphasized that the mandate of the [Fourth] Amendment requires adherence to judicial processes," United States v. Jeffers, 342 U.S. 48, 51 , and that searches conducted outside the judicial process, without prior approval by judge or magistrate, are per se unreasonable under the Fourth Amendment --- subject only to a few specifically established and well-delineated exceptions.(10)It is difficult to imagine how any of those exceptions could ever apply to the sort of search and seizure involved in this case. Even electronic surveillance substantially contemporaneous with an individual's arrest could hardly be deemed an "incident" of that arrest. [389 U.S. 347, 358] Nor could the use of electronic surveillance without prior authorization be justified on grounds of "hot pursuit." And, of course, the very nature of electronic surveillance precludes its use pursuant to the suspect's consent.(11)The Government does not question these basic principles. Rather, it urges the creation of a new exception to cover this case. It argues that surveillance of a telephone booth should be exempted from the usual requirement of advance authorization by a magistrate upon a showing of probable cause. We cannot agree. Omission of such authorization"bypasses the safeguards provided by an objective predetermination of probablecause, and substitutes instead the far less reliable procedure of an after-the-eventjustification for the . . . search, too likely to be subtly influenced by the familiarshortcomings of hindsight judgment." Beck v. Ohio, 379 U.S. 89, 96 .And bypassing a neutral predetermination of the scope of a search leaves individuals secure from Fourth Amendment [389 U.S. 347, 359] violations "only in the discretion of the police." Id., at 97.(12)These considerations do not vanish when the search in question is transferred from the setting of a home, an office, or a hotel room to that of a telephone booth. Wherever a man may be, he is entitled to know that he will remain free from unreasonable searches and seizures. The government agents here ignored "the procedure of antecedent justification . . . that is central to the Fourth Amendment," a procedure that we hold to be a constitutional precondition of the kind of electronic surveillance involved in this case. Because the surveillance here failed to meet that condition, and because it led to the petitioner's conviction, the judgment must be reversed.It is so ordered.MR. JUSTICE MARSHALL took no part in the consideration or decision of this case.MR. JUSTICE DOUGLAS, with whom MR. JUSTICE BRENNAN joins, concurring.While I join the opinion of the Court, I feel compelled to reply to the separate concurring opinion of my Brother WHITE, which I view as a wholly unwarranted green light for the Executive Branch to resort to electronic eaves-dropping without a warrant in cases which the Executive Branch itself labels "national security" matters.Neither the President nor the Attorney General is a magistrate. In matters where they believe national security may be involved they are not detached, disinterested, and neutral as a court or magistrate must be. Under the separation of powers created by the Constitution, the Executive Branch is not supposed to be neutral and disinterested. Rather it should vigorously investigate [389 U.S. 347, 360] and prevent breaches of national security and prosecute those who violate the pertinent federal laws. The President and Attorney General are properly interested parties, cast in the role of adversary, in national security cases. They may even be the intended victims of subversive action. Since spies and saboteurs are as entitled to the protection of the Fourth Amendment as suspected gamblers like petitioner, I cannot agree that where spies and saboteurs are involved adequate protection of Fourth Amendment rights is assured when the President and Attorney General assume both the position ofadversary-and-prosecutor and disinterested, neutral magistrate.There is, so far as I understand constitutional history, no distinction under the Fourth Amendment between types of crimes. Article III, 3, gives "treason" a very narrow definition and puts restrictions on its proof. But the Fourth Amendment draws no lines between various substantive offenses. The arrests in cases of "hot pursuit" and the arrests on visible or other evidence of probable cause cut across the board and are not peculiar to any kind of crime.I would respect the present lines of distinction and not improvise because a particular crime seems particularly heinous. When the Framers took that step, as they did with treason, the worst crime of all, they made their purpose manifest.MR. JUSTICE HARLAN, concurring.I join the opinion of the Court, which I read to hold only (a) that an enclosed telephone booth is an area where, like a home, Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 , and unlike a field, Hester v. United States, 265 U.S. 57 , a person has a constitutionally protected reasonable expectation of privacy; (b) that electronic as well as physical intrusion into a place that is in this sense private may constitute a violation of the Fourth Amendment; [389 U.S. 347, 361] and (c) that the invasion of a constitutionally protected area by federal authorities is, as the Court has long held, presumptively unreasonable in the absence of a search warrant.As the Court's opinion states, "the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places." The question, however, is what protection it affords to those people. Generally, as here, the answer to that question requires reference to a "place." My understanding of the rule that has emerged from prior decisions is that there is a twofold requirement, first that a person have exhibited an actual (subjective) expectation of privacy and, second, that the expectation be one that society is prepared to recognize as "reasonable." Thus a man's home is, for most purposes, a place where he expects privacy, but objects, activities, or statements that he exposes to the "plain view" of outsiders are not "protected" because no intention to keep them to himself has been exhibited. On the other hand, conversations in the open would not be protected against being overheard, for the expectation of privacy under the circumstances would be unreasonable. Cf. Hester v. United States, supra.The critical fact in this case is that "[o]ne who occupies it, [a telephone booth] shuts the door behind him, and pays the toll that permits him to place a call is surely entitled to assume" that his conversation is not being intercepted. Ante, at 352. The point is not that the booth is "accessible to the public" at other times, ante, at 351, but that it is a temporarily private place whose momentary occupants' expectations of freedom from intrusion are recognized as reasonable. Cf. Rios v. United States, 364 U.S. 253 .In Silverman v. United States, 365 U.S. 505 , we held that eavesdropping accomplished by means of an electronic device that penetrated the premises occupied by petitioner was a violation of the Fourth Amendment. [389 U.S. 347, 362] That case established that interception of conversations reasonably intended to be private could constitute a "search and seizure," and that the examination or taking of physical property was not required. This view of the Fourth Amendment was followed in Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 , at 485, and Berger v. New York, 388 U.S. 41 , at 51. Also compare Osborn v. United States, 385 U.S. 323 , at 327. In Silverman we found it unnecessary to re-examine Goldman v. United States, 316 U.S. 129 , which had held that electronic surveillance accomplished without the physical penetration of petitioner's premises by a tangible object did not violate the Fourth Amendment. This case requires us to reconsider Goldman, and I agree that it should now be overruled. * Its limitation on Fourth Amendment protection is, in the present day, bad physics as well as bad law, for reasonable expectations of privacy may be defeated by electronic as well as physical invasion.Finally, I do not read the Court's opinion to declare that no interception of a conversation one-half of which occurs in a public telephone booth can be reasonable in the absence of a warrant. As elsewhere under the Fourth Amendment, warrants are the general rule, to which the legitimate needs of law enforcement may demand specific exceptions. It will be time enough to consider any such exceptions when an appropriate occasion presents itself, and I agree with the Court that this is not one.[ Footnote * ] I also think that the course of development evinced by Silverman, supra, Wong Sun, supra, Berger, supra, and today's decision must be recognized as overruling Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438 , which essentially rested on the ground that conversations were not subject to the protection of the Fourth Amendment.MR. JUSTICE WHITE, concurring.I agree that the official surveillance of petitioner's telephone conversations in a public booth must be subjected [389 U.S. 347, 363] to the test of reasonableness under the Fourth Amendment and that on the record now before us the particular surveillance undertaken was unreasonable absent a warrant properly authorizing it. This application of the Fourth Amendment need not interfere with legitimate needs of law enforcement. *In joining the Court's opinion, I note the Court's acknowledgment that there are circumstances in which it is reasonable to search without a warrant. In this connection, in footnote 23 the Court points out that today's decision does not reach national security cases.Wiretapping to protect the security of the Nation has been authorized by successive Presidents. The present Administration would apparently save national security cases from restrictions against wiretapping. See Berger v. New York, 388 U.S. 41, 112 -118 (1967) (WHITE, J., [389 U.S. 347, 364] dissenting). We should not require the warrant procedure and the magistrate's judgment if the President of the United States or his chief legal officer, the Attorney General, has considered the requirements of national security and authorized electronic surveillance as reasonable.[ Footnote * ] In previous cases, which are undisturbed by today's decision, the Court has upheld, as reasonable under the Fourth Amendment, admission at trial of evidence obtained (1) by an undercover police agent to whom a defendant speaks without knowledge that he is in the employ of the police, Hoffa v. United States, 385 U.S. 293 (1966); (2) by a recording device hidden on the person of such an informant, Lopez v. United States, 373 U.S. 427 (1963); Osborn v. United States, 385 U.S. 323 (1966); and (3) by a policeman listening to the secret micro-wave transmissions of an agent conversing with the defendant in another location, On Lee v. United States, 343 U.S. 747 (1952). When one man speaks to another he takes all the risks ordinarily inherent in so doing, including the risk that the man to whom he speaks will make public what he has heard. The Fourth Amendment does not protect against unreliable (or law-abiding) associates. Hoffa v. United States, supra. It is but a logical and reasonable extension of this principle that a man take the risk that his hearer, free to memorize what he hears for later verbatim repetitions, is instead recording it or transmitting it to another. The present case deals with an entirely different situation, for as the Court emphasizes the petitioner "sought to exclude . . . the uninvited ear," and spoke under circumstances in which a reasonable person would assume that uninvited ears were not listening.MR. JUSTICE BLACK, dissenting.If I could agree with the Court that eavesdropping carried on by electronic means (equivalent to wiretapping) constitutes a "search" or "seizure," I would be happy to join the Court's opinion. For on that premise my Brother STEWART sets out methods in accord with the Fourth Amendment to guide States in the enactment and enforcement of laws passed to regulate wiretapping by government. In this respect today's opinion differs sharply from Berger v. New York, 388 U.S. 41 , decided last Term, which held void on its face a New York statute authorizing wiretapping on warrants issued by magistrates on showings of probable cause. The Berger case also set up what appeared to be insuperable obstacles to the valid passage of such wiretapping laws by States. The Court's opinion in this case, however, removes the doubts about state power in this field and abates to a large extent the confusion and near-paralyzing effect of the Berger holding. Notwithstanding these good efforts of the Court, I am still unable to agree with its interpretation of the Fourth Amendment.My basic objection is twofold: (1) I do not believe that the words of the Amendment will bear the meaning given them by today's decision, and (2) I do not believe that it is the proper role of this Court to rewrite the Amendment in order "to bring it into harmony with the times" and thus reach a result that many people believe to be desirable. [389 U.S. 347, 365]While I realize that an argument based on the meaning of words lacks the scope, and no doubt the appeal, of broad policy discussions and philosophical discourses on such nebulous subjects as privacy, for me the language of the Amendment is the crucial place to look in construing a written document such as our Constitution. The Fourth Amendment says that"The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects,against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrantsshall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, andparticularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to beseized."The first clause protects "persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures . . . ." These words connote the idea of tangible things with size, form, and weight, things capable of being searched, seized, or both. The second clause of the Amendment still further establishes its Framers' purpose to limit its protection to tangible things by providing that no warrants shall issue but those "particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized." A conversation overheard by eavesdropping, whether by plain snooping or wiretapping, is not tangible and, under the normally accepted meanings of the words, can neither be searched nor seized. In addition the language of the second clause indicates that the Amendment refers not only to something tangible so it can be seized but to something already in existence so it can be described. Yet the Court's interpretation would have the Amendment apply to overhearing future conversations which by their very nature are nonexistent until they take place. How can one "describe" a future conversation, and, if one cannot, how can a magistrate issue a warrant to eavesdrop one in the future? It is argued that information showing what [389 U.S. 347, 366] is expected to be said is sufficient to limit the boundaries of what later can be admitted into evidence; but does such general information really meet the specific language of the Amendment which says "particularly describing"? Rather than using language in a completely artificial way, I must conclude that the Fourth Amendment simply does not apply to eavesdropping.Tapping telephone wires, of course, was an unknown possibility at the time the Fourth Amendment was adopted. But eavesdropping (and wiretapping is nothing more than eavesdropping by telephone) was, as even the majority opinion in Berger, supra, recognized, "an ancient practice which at common law was condemned as a nuisance. 4 Blackstone, Commentaries 168. In those days the eavesdropper listened by naked ear under the eaves of houses or their windows, or beyond their walls seeking out private discourse." 388 U.S., at 45 . There can be no doubt that the Framers were aware of this practice, and if they had desired to outlaw or restrict the use of evidence obtained by eavesdropping, I believe that they would have used the appropriate language to do so in the Fourth Amendment. They certainly would not have left such a task to the ingenuity of language-stretching judges. No one, it seems to me, can read the debates on the Bill of Rights without reaching the conclusion that its Framers and critics well knew the meaning of the words they used, what they would be understood to mean by others, their scope and their limitations. Under these circumstances it strikes me as a charge against their scholarship, their common sense and their candor to give to the Fourth Amendment's language the eavesdropping meaning the Court imputes to it today.。