A cross-correlation of WMAP and ROSAT

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:113.45 KB

- 文档页数:6

Open reduction and internal fixation compared to closed reduction and external fixation in distal radial fracturesA randomized study of 50 patientsAntonio Abramo 1, Philippe Kopylov 1, Mats Geijer 2, and Magnus Tägil 11Hand Unit, Department of Orthopedics, Clinical Sciences, Lund University; 2Department of Radiology, Lund University Hospital, SwedenCorrespondence: tony.abramo@med.lu.seSubmitted 08-04-22. Accepted 09-02-22Open Access - This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the source is credited.DOI 10.3109/17453670903171875Background and purpose In unstable distal radial fractures thatare impossible to reduce or to maintain in reduced position, thetreatment of choice is operation. The type of operation and thechoice of implant, however, is a matter of discussion. Our aim wasto investigate whether open reduction and internal fixation wouldproduce a better result than traditional external fixation.Methods 50 patients with an unstab le or comminute distalradius fracture were randomized to either closed reduction andb ridging external fixation, or open reduction and internal fixa-tion using the TriMed system. The primary outcome parameterwas grip strength, but the patients were followed for 1 year withob jective clinical assessment, sub jective outcome using DASH,and radiographic examination.Results At 1 year postoperatively, grip strength was 90% (SD16) of the uninjured side in the internal fixation group and 78%(17) in the external fixation group. Pronation/supination was 150°(15) in the internal fixation group and 136° (20) in the externalfixation group at 1 year. There were no differences in DASHscores or in radiographic parameters. 5 patients in the externalfixation group were reoperated due to malunion, as compared to1 in the internal fixation group. 7 other cases were classified asradiographic malunion: 5 in the external fixation group and 2 inthe internal fixation group.Interpretation Internal fixation gave b etter grip strengthand a better range of motion at 1 year, and tended to have lessmalunions than external fixation. No difference could be foundregarding subjective outcome.N Distal radial fractures account for about one-sixth of the frac-tures seen in the emergency room, with an annual incidenceof 26 per 10,000 inhabitants in Sweden (Brogren et al. 2007).Non-operative treatment using plaster cast is chosen in non-displaced fractures and in displaced, but reducible fractures (Handoll and Madhok 2003a). The subject of our study is: fractures that are primarily impossible to reduce or impossible to retain in an acceptable position. These fractures are often considered necessary to operate. The type of operation and the choice of implant is still, however, a matter of discussion; a Cochran report has stated that “randomized trials do not provide robust evidence for most of the decisions necessary in the management of these fractures” (Handoll and Madhok 2003b).At our department, 2 types of surgical interventions have been used over the last decade for the treatment of distal radius fractures. The TriMed fragment-specific system (Schnall et al. 2006), is used preferably in younger patients whereas external fixation has been used more in older patients, but is still an acceptable option in all age groups. The present randomized study was conducted to compare closed reduction combined with external fixation—which has been or still is the standard operation in many hospitals—to the more complex and more technically demanding open reduction and internal fixation. Our aim was to determine whether a more accurate reduction could be achieved and retained during healing, and whether the outcome—both objective and subjective—could be improved by internal fragment-specific fixation methods, compared to external fixation. The study allowed the best possible opera-tion performed either openly or closed—thus allowing for additional pins, bone substitute, or graft if deemed necessary. As primary outcome, we chose grip strength at 7 weeks and 12 months postoperatively and as secondary outcome we chosethe DASH score at the same 2 time points.Patients and methods Patients At our department, all patients with a distal radial fracture areyears old were considered to be less osteoporotic. The aim was to recruit at least 24 patients (4 blocks) in each age group and the sealed envelopes were opened on the day of surgery, immediately before the operation. Randomization would stop when 4 blocks (24 patients) in each group had been random-ized. 26 patients were randomized to the O treatment and 24 to the C treament. Evaluation All patients were followed for 1 year with visits at 2, 5, and 7 weeks and 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. The grip strength at 7 weeks and at 12 months was chosen as the pri-mary outcome and the DASH score at the same time points was chosen as the secondary outcome. Reoperations for either a malunion or a redislocation of the fracture were considered to be endpoints and patients were excluded thereafter. Com-plications were registered by a hand surgeon at each visit. Complications were divided into (1) major complications, defined as those that were expected to have an effect on the final outcome, (2) moderate complications, defined as those that were not expected to have an effect on the final outcome but would need further interventions, and (3) minor compli-cations, defined as temporary and self-healing. Grip strength (JAMAR), range of motion (goniometer), and sensibility in all fingers (Weber 2PD) were recorded by a physiotherapist at all visits. Lateral and AP radiographs were taken at injury, directly postoperatively, at 2 and 5 weeks, and at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. All radiographs were classified by a radiologist (MG) according to the Frykman and AO classifi-cations. The radiographic result after healing was evaluated according to the same criteria as used for the definition of the primary instability (Table 1). Subjective outcome was evalu-ated using the DASH score, which is a self-administered ques-tionnaire developed by the AAOS and the Institute for Work and Health in Canada (Hudak et al. 1996). The questionnaire consists of 30 questions evaluating physical activities, severity of symptoms, and the effect of the injury on social activities. A score is calculated and converted to a scale from 0 to 100 with a score of 100 expressing the largest degree of disability. A Swedish version was used, which has been validated for gen-eral use in upper extremity disorders (Atroshi et al. 2000). At inclusion, the patients were asked to fill out the DASH ques-tionnaire relating to their pre-injury status and then again at 7 weeks, 3 months, and 1 year postoperatively. One patient in the O group moved to another part of the country and declined further visits after 7 weeks, when she was back to work and with full function. 1 patient in the O group failed to return the DASH form at 7 weeks, and another in the same group failed to return the form at 3 months. 1 patient in the O group failed to appear at the physical examination at 6 months. 2 patients in the C group failed to appear at the 12-month visit, but returned their completed DASH forms.treated according to a treatment protocol (Abramo et al. 2008).Non-displaced fractures are treated in a plaster cast for 4–5weeks. Displaced fractures are reduced and casted. If the frac-ture after reduction is unstable or even impossible to primarilyreduce (for definitions, see Table 1), surgical treatment is sug-gested to the patient. Patients with fractures in the AO groupsA1–3 and C1–3 were eligible for the study. These patientswere invited to participate in a randomized study comparingopen and closed treatment. The study was approved by thelocal ethics committee (no. Lu 45/02).Between May 2002 and December 2005, 50 patients (36women) with a mean age of 48 (20–65) years with unstablefractures fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Most patientswith a distal radius fracture were older than 65 years and werenot eligible for the study. Patients with a redislocated frac-ture were also not eligible for the study. Thus, only youngerpatients with an unstable fracture who were in need of anacute operation were recruited, thus explaining the relativelylong recruitment time.The patients gave their written and informed consent, andwere included and randomized to either open reduction andinternal fixation (O), or closed reduction and external fixation(C). 38 patients considered themselves to be healthy, 5 hadcardiovascular diseases such as hypertension or atrial fibrilla-tion, 1 had diabetes mellitus, 1 had epilepsy, 1 had hypothy-roidism, 1 had well-controlled depressive problems, and 3 hadasthma.RandomizationRandomization was prepared in blocks of 6 containing equalnumbers of C and O patients, and the patients were stratifiedinto 2 age groups. The older group was considered to be moreosteoporotic and consisted of men of 60 years of age andabove, and women of 50 years of age and above. The youngergroup of women less than 50 years old and men less than 60 Table 1. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studyOperative techniqueThe patients were operated by 1 of 4 senior hand surgeons.The participating surgeons agreed to aim for the best possiblestabilization in each patient with each technique, including theuse of additional K-wires, bone graft, or bone substitute. Thefragment-specific wrist fixation system TriMed (Konrath andBahler 2002) was used for internal fixation. The system con-sists of a combination of pins, plates, and screws (Figure 1).V olar fixed-angle plates were not available at the start of thestudy and were not used.Open reduction and internal fixation (O). Ordinarily, 2 inci-sions were made through the first and fourth extensor com-ter active mobilization was started under the supervision of aphysiotherapist.Closed reducti on and external fixati on (C). The externalfixator used for the first 20 patients was the Hoffman type-1 bridging external fixator (Stryker, Hopkinton, MA), whichwas changed to the Radio Lucent Wrist Fixator (OrthofixSrl, Bussolengo, Italy) by the start of 2005 and used in thelast 4 patients. Pins were inserted into the second metacarpaland into the radius proximally to the fracture. Clamps wereattached to the pins and the fracture was reduced and fixatedwith a steel rod between the clamps (Figure 2). In comminutedfractures with a bone defect and when additional stability wasdesired, K-wires were inserted percutaneously. A bone graftsubstitute (Norian SRS), also inserted percutaneously, wasused at the surgeons’ discretion (2 patients). The fixator wasusually removed after 5–6 weeks and thereafter active mobili-zation was started under the supervision of a physiotherapist.There was no restriction regarding pronation or supinationduring the fixation time in either of the groups.Statistics Based on the results of a previous study comparing external fixation with closed treatment using a bone substitute (Kopylov et al. 1999), grip strength was chosen as the primary outcome and a power analysis was performed. 20 patients were needed in each group to show a 10% difference in grip strength with a power of 85% in a two-sided test at the 5% significance level. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorized outcomes and Mann-Whitney U test for ordinal outcomes. Student’s t-test was used for continuous data such as radiographic measure-ments. Spearman correlation coefficient was used to calculate correlations between objective and radiographic parameters. SPSS software version 14.0 was used. Bonferroni correction was used for repeated measures of objective parameters at 7 weeks and at 12 months of follow-up.Figure 1. AP and lateral radiographs in two cases of distal radial fracture operated with the TriMed system. A. This patient was operated using a radial pin-plate and a volar buttress pin. Additionalstability was achieved using Norian SRS bone substitute. B. In intraarticular fractures with an ulnar fragment, an ulnar pin-plate could be combined with the radial pin-plate.Figure 2. AP and lateral radiographs of a patient operated using closedreduction and external fixation.partments. The fracture was reducedand 2 pins were introduced at the tipof the radial styloid, obliquely andin a proximal direction—leaving theradial cortex ulnarly and proximally.A stabilizing pin-plate was threadedonto the styloid pins and the platewas secured to the radial side of theradius by 3–5 screws. Through thedorsal incision, a buttress pin and/oran ulnar pin-plate was introducedfor dorsal stability. At the surgeon’sdiscretion, Norian SRS (Kopylov2001) (Synthes GmbH, Switzerland) was used in the void to add stabil-ity (2 patients). Postoperatively, the patients were treated with a forearmplaster cast for 2 weeks and thereaf-statistically significant difference was still found between the O and C groups both regarding the primary outcome param-eter grip strength (90% and 78%, respectively) (p = 0.03) and also forearm rotation (149° and 136°, respectively) (p = 0.03). In both groups, range of movement in extension/flexion was 121° and in radial/ulnar deviation it was 60°.Subjective outcome (Figure 3)The secondary outcome parameter, mean DASH score, was 3 (0–45) before the injury (Table 4) as reported by the patients. 41/48 had a score of 1 or less before injury. 3 patients had a pre-injury DASH score higher than 20, 2 of them due to CMC1 osteoarthritis, and 1 due to shoulder impingement. The results of the postoperative DASH questionnaires showed noROM in extension–flexion ROM in pronation–supination605040302010ROM in radial–ulnar deviation Grip strength (%)Results Age, sex, injured side, type of work, category of fracture, radiographic findings, and type of injury were equally distributed between the groups (Tables 2 and 3; see supple-mentary data). Most patients had intraarticular fractures, either in the radiocarpal joint or in the distal radio-ulnar joint or both, and only 8 patients had extraarticular fractures. There were 4 AO type-A fractures in eachgroup, and 20 type-C fractures in theC group and 22 in the O group.The operations were performed ata mean time of 3.6 (1–9) days afterinjury. In 7 patients in the C group,the fracture was augmented withK-wires. Norian SRS was used in 2patients in each group. Postopera-tively, the patients in the open groupwere treated in a forearm plaster castfor 14 (6–20) days, and the patientsin the closed group wore the fixatorfor 36 (33–41) days. There were noperoperative complications.Objective outcome (Figure 3)At 7 weeks postoperatively, the pri-mary outcome parameter, mean grip strength, was significantly higher in the O group than in the C group (47% of the uninjured side and 34% of the uninjured side, respectively) (p =0.01). Also, the mean range of motion in forearm rotation was significantly greater in the O group than in the C group (129° and 104°, respectively) (p = 0.006). No statistically signifi-cant differences were found regard-ing extension/flexion (88° and 74°, respectively) (p = 0.09) or radial/ulnar deviation (48° and 41°) (p = 0.2) at the early follow-up. At the final follow-up 1 year postoperatively, astatistically significant differences between the groups at any time after surgery (i.e. 7 weeks, 3 months, or 1 year postopera-tively). The DASH scores for the extraarticular fractures were better than the intraarticular scores 3 months postoperatively (median 6.8 vs.17; p = 0.01), but no statistically significant difference was found at 1 year.Complications50 postoperative complications occurred in 34 patients (Table 5). 1 patient in the O group had a postoperative swelling of the hand and fingers, which led to hospitalization for 2 days. Another patient in the same group had a small, incomplete longitudinal fracture proximal to the initial fracture. This was left untreated, and it healed without complications. 2 patients—both in the external fixation (C) group—had early dislocation of the fracture, resulting in both radial compres-sion and angulation requiring surgical correction. 1 patient was reoperated after 2 weeks and the other was reoperated 6 months postoperatively at another hospital. These 2 patients were then excluded from the study analyses.Most complications in both groups were minor, such as transient carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) not requiring surgery, skin adhesions, tendonitis not requiring surgery, transient radial neurapraxia, excessive postoperative pain, and super-ficial infections not requiring antibiotics. The most common minor complication in the O group was radial nerve symp-toms, due to the surgical approach through the first extensor compartment for the radial pin-plate. In all cases but 1, the nerve symptoms were transient and had resolved at the final follow-up at 1 year. 1 patient had the plate removed.Moderate complications requiring secondary interventions but not affecting the final outcome were equally common in both groups. Major complications, which may influence the final outcome, such as malunions requiring additional surgery, splinting, or reflex sympathetic dystrophy, were more common in the C group (Table 5). In the symptomatic malunions lead-ing to a secondary procedure, 1 patient in the C group had a radiocarpal intraarticular malunion and 5 others had extraar-ticular malunions with shortening and/or angulation of the radius. 5 of these patients were operated with a radial oste-otomy, 2 of them also with ulnar shortening. 1 patient in the C group was reoperated with the TriMed, 2 weeks after the primary operation. In addition to the malunions requiring cor-rective osteotomy, there were 7 other cases of radiographic malunion not in need of further surgery but with an incongru-ence in either the distal radioulnar joint or in the radiocarpal joint. These malunions are described below in the radiography section. The total number of malunions—those requiring cor-rective osteotomy and/or radiographic malunions—was 10 in the C group and 3 in the O group.Sick leavePatients with moderate-to-heavy manual work had more days at home from work in the C group than in the O group (Table 6). For patients with desk work, there was no statistically sig-nificant difference.Table 5. Complications by group and severityTable 4. Pre- and postoperative DASH scoresRadiologyThe fracture types, as classified by the Frykman and by the AO classification, were symmetrically distributed between the groups (Table 3; see supplementary data). As 8 patients in the C group and 10 in the O group underwent closed reduction at the ER prior to the first radiograph, preoperative radiographic measurements could not be done. There were no differences between the groups in mean postoperative radial inclination, dorsal angulation, radial compression, and incongruence in the radiocarpal and the distal radioulnar joint at any time post-operatively (Table 7; see supplementary data). In addition to the 6 malunions requiring corrective osteotomy, there were 7 cases of radiographic loss of correction, 5 in the C group and 2 in the O group. In the C group, 2 cases had intraarticular malunions with intraarticular steps of 2.2 mm and 2.4 mm, 2 cases had ulnar variances of 4.3 mm and 7.9 mm, and 1 case had both a dorsal angulation of 21˚ and an ulnar variance of 4.3 mm. 2 radiographic malunions were seen in the O group, 1 with an articular step of 3.3 mm and 1 with an ulnar variance of 6 mm.DiscussionIn contrast to many other fractures, there are have been a number of randomized studies on treatment of distal radial fractures. However, no clear conclusions can be drawn from meta-analyses of all randomized radial fracture studies as sum-marized in the Cochrane report (Handoll and Madhok 2003b) where 48 randomized trials and 25 different treatment options were compared in 3,371 patients. Also, in a major meta-analy-sis (Margaliot et al. 2005) of 46 non-randomized studies with either external or internal fixation in 1,519 patients, no clear conclusion could be drawn. Finally, in addition to the lack of consensus regarding the older established methods, no random-ized or high-quality prospective non-randomized studies have been carried out yet for the newest concepts. We believe that these new concepts, such as the TriMed system used in the pres-ent study or the increasingly popular volar angle-stable plates, improve the treatment of unstable distal radial fractures.To our knowledge, 4 randomized studies have compared open reduction and internal fixation to closed or indirect reduction. In a recent study by Leung et al. (2008), a better result was found for internal fixation with AO plates either dorsally or volarly compared to bridging external fixation with augmentation with Kirschner wires at the surgeon’s dis-cretion. The other 3 studies have reported either an absence of significant differences or a better functional outcome for external fixation (Kapoor et al. 2000, Grewal et al. 2005, Kreder et al. 2005). Grewal and co-workers (2005) also found a higher complication rate for internal fixation with a dorsal plate than for external fixation. Kapoor and co-workers (2000) concluded that open reduction and internal fixation provide the best articular anatomy in highly comminuted fractures, although the best outcome was achieved with the external fix-ator. Grewal et al. (2005) compared internal fixation using the dorsal Pi-plate with mini-open reduction and external fixation, and found a higher complication rate for the Pi-plate. A better grip strength was found in the mini-open group but there were no significant differences in ROM or DASH. Kreder et al. (2005) randomized 179 patients between either a mini-open indirect reduction and K-wires/screws or a full arthrotomy with internal fixation. A better result was found for the indirect group, but a high rate of crossovers from the indirect group to the open group at the time of surgery was reported and many patients were lost to follow-up.Higher rates of infection and hardware failure have been reported in patients treated with external fixation and higher rates of tendon complications with internal fixation (Margaliot et al. 2005). Thus, in the literature as well as in our study, the patterns of complications differ between the methods and might help the orthopedic surgeon to decide whether to use external or internal fixation. We found a high rate of complica-tions, but most were minor and transient. In the external fixa-tion group, the rate of major complications such as redisloca-tion requiring reoperation or complex regional pain syndrome was higher. Other studies have reported complication rates of 20% and 85% with external fixation (Anderson et al. 2004, Capo et al. 2006), most complications being minor.The malunion rate is an important outcome variable when evaluating different surgical treatments, and should be included in the overall decision. In our study, 5 cases in the external fix-ation group and 1 case in the internal fixation group had loss of reduction and malunions requiring further surgery. 5 otherpatients in the C group and 2 in the O group had radiographic Table 6. Days away from workmalunion only. The malunion rate found by McQueen (1998),comparing non-bridging external fixation to bridging external fixation, was similar to ours: 14 in the 30 patients treated with bridging external fixator.Regarding grip strength, which was the primary outcome in the power analysis, the group that was operated with internal fixation had a better result, maybe less surprising, at 7 weeks, but more important also at 12 months. Also, regarding fore-arm rotation, the results were better in the internal fixation (O) group at all follow-up visits. The absolute values of grip strength and range of motion in the present study were similar to those in other studies, both in the C group (McQueen et al. 1996, Harley et al. 2004, Wright et al. 2005, Atroshi et al. 2006) and in the O group, and in the latter case both compar-ing to the TriMed system (Benson et al. 2006, Schnall et al. 2006) or to the latest fixation trends of angle-stable volar plat-ing (Musgrave and Idler 2005, Wright et al. 2005).There may be different explanations for the increased range of motion and grip strength in the internal fixation group after 1 year of follow-up. The fractures in the O group might be better aligned at surgery and/or a better reduction may be maintained during the healing, leading to a better congruency of the joint. In the O group rehabilitation starts 3 weeks earlier, which could explain the early difference between the groups, both regarding range of motion and grip strength, as found in previous studies (Kopylov et al. 1999). However, in the pres-ent study, this effect persisted throughout the whole of the first year. Also, regarding the subjective outcome there was a ten-dency for there to be a better outcome in the O group.The median DASH values in our series (9 in the O group and 14 in the C group) are similar to the results in other studies reporting DASH scores, around 16 for the volar plate (Mus-grave and Idler 2005, Wright et al. 2005), between 9 and 17 for the TriMed system (Konrath and Bahler 2002, Benson et al. 2006, Gerostathopoulos et al. 2007), and between 7 and 17 for external fixation (McQueen et al. 1996, Harley et al. 2004, Wright et al. 2005, Atroshi et al. 2006). This subjective outcome in both groups must be considered favorable, bearing in mind that in our study internal and external fixation was compared in the most unstable distal radial fractures.In this group of patients with primarily unstable fractures, there is no acceptable alternative to surgery. The two methods we compared will both give a good result with good DASH values, good grip strength, and good range of motion after a year. Overall, considering the subjective and objective results as well as the rate of major complications and the sick-leave, we believe that internal fixation gives a superior result and in our opinion it would be the method of choice; however, results for the external fixator are still acceptable. Which method to use to internally stabilize the fracture is still a matter for dis-cussion and should be the subject of future randomized stud-ies. With smaller and smaller differences between the 2 meth-ods, better and more sensitive subjective outcome instruments will be required if the number of patients needed to show a difference is to be kept within reasonable numbers.AA: project set-up, planning, collection and interpretation of data, statistics, and writing of the manuscript. PK: project set-up, planning, and revision of the manuscript. MG: data collection and revision of the manuscript. MT: proj-ect set-up, planning, and revision of the manuscript.We thank physiotherapist Kerstin Runnquist for excellent assistance in follow-up of the patients and Ewa Persson for excellent secretarial assistance.The project was supported by Region Skåne, Lund University Hospital, the Swedish Medical Research Council (project 09509), the Alfred Österlund Foundation, the Greta and J ohan Kock Foundation, the Maggie Stephens Foundation, the Thure Carlsson Foundation, and the Faculty of Medicine at Lund University.Supplementary dataTables 2, 3 and 7 can be found at our website , iden-tification number 2771/09.Abramo A, Kopylov P, Tägil M. Evaluation of a treatment protocol in distal radius fractures. A prospective study in 581 patients using DASH as out-come. Acta Orthop. 2008; 79 (3): 376-85.Anderson J T, Lucas G L, Buhr B R. Complications of treating distal radius fractures with external fixation: a community experience. Iowa Orthop J 2004; 24: 53-9.Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Andersson B, Dahlgren E, Johansson A. The dis-abilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) outcome questionnaire: reliability and validity of the Swedish version evaluated in 176 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71 (6): 613-8.Atroshi I, Brogren E, Larsson G U, Kloow J, Hofer M, Berggren A M. Wrist-bridging versus non-bridging external fixation for displaced distal radius fractures: a randomized assessor-blind clinical trial of 38 patients followed for 1 year. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (3): 445-53.Benson L S, Minihane K P, Stern L D, Eller E, Seshadri R. The outcome of intra-articular distal radius fractures treated with fragment-specific fixa-tion. J Hand Surg (Am) 2006; 31 (8): 1333-9.Brogren E, Petranek M, Atroshi I. Incidence and characteristics of distal radius fractures in a southern Swedish region. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007; 8: 48.Capo J T, Swan K G, Jr., Tan V. External fixation techniques for distal radius fractures. Clin Orthop 2006; (445): 30-41.Gerostathopoulos N, Kalliakmanis A, Fandridis E, Georgoulis S. Trimed fixa-tion system for displaced fractures of the distal radius. J Trauma 2007; 62 (4): 913-8.Grewal R, Perey B, Wilmink M, Stothers K. A randomized prospective study on the treatment of intra-articular distal radius fractures: open reduction and internal fixation with dorsal plating versus mini open reduction, per-cutaneous fixation, and external fixation. J Hand Surg (Am) 2005; 30 (4): 764-72.Handoll H H, Madhok R. Conservative interventions for treating distal radial fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003a; (2): CD000314. Handoll H H, Madhok R. Surgical interventions for treating distal radial frac-tures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003b; (3): CD003209. Harley B J, Scharfenberger A, Beaupre L A, Jomha N, Weber D W. Augmented external fixation versus percutaneous pinning and casting for unstable frac-tures of the distal radius--a prospective randomized trial. J Hand Surg (Am) 2004; 29 (5): 815-24.Hudak P L, Amadio P C, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG). Am J Ind Med 1996; 29 (6): 602-8.。

D i g e s t i v e D i s e a s e a n dE n d o s c o p y 中国消化内镜散发性大肠癌脆性组氨酸三联体基因与错配修复基因蛋白表达关系的研究白文元苏艳欣穆华(河北医科大学第二医院消化内科,石家庄,050000)【摘要】目的探讨散发性大肠癌(Spor a di c C ol or ect al C ar ci nom a,SCC)组织中脆性组氨酸三联体基因(Fr agi l eH i s t i di ne T r i ad,FH I T)与错配修复基因(hum a n D N A M i sm a t c h R e pai r gene,hM M R)蛋白的表达之间有无相关性,以进一步研究大肠癌的发病机制。

方法采用免疫组织化学的方法,检测了50例散发性大肠癌组织中的FH I T、hM LH1、hM SH2蛋白表达。

结果(1)所有正常/非瘤组织中FH I T、hM LH1和hM SH2蛋白均为阳性表达。

(2)FH I T蛋白表达的缺失癌在高、中和低分化癌中分别为3/10、11/29和9/11,低分化癌中FH I T表达的缺失癌与高、中分化癌比较,差异有显著性(P<0.01)。

FH I T蛋白低表达癌在不同D uke’s分期癌中的分布为A和B期癌中总共为12/36,D uke’s C期癌中为11/14。

已伴淋巴结转移的C期癌与未转移组的A和B期癌比较,差异有显著性(P<0.01)。

(3)散发性大肠癌中主要发生突变的错配修复基因是hM LH1。

hM L H1和(或)hM SH2蛋白低表达癌在高、中和低分化癌中分别为2/10、6/29和7/11,低分化癌中hM LH1或hM S H2蛋白表达的缺失与高、中分化癌比较,差异有显著性(P<0.05)。

h M LH1和(或)hM SH2蛋白低表达癌在左侧和右侧大肠癌组织中分别为8/38和7/12,hM SH2蛋白低表达癌多分布在右侧大肠癌。

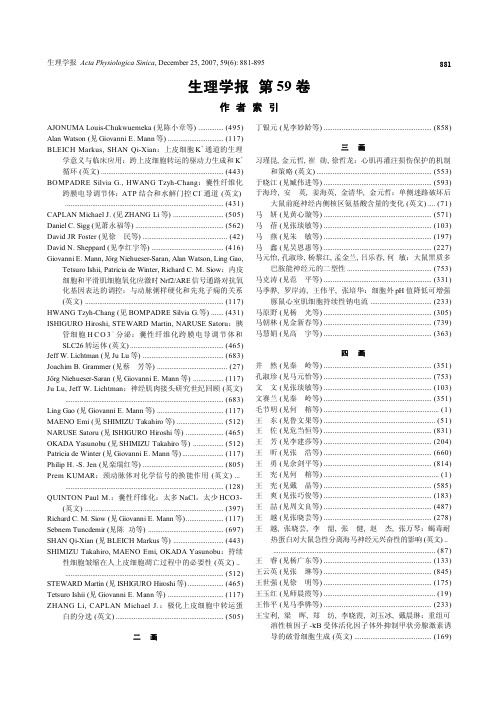

生理学报第59卷作 者 索 引AJONUMA Louis-Chukwuemeka (见陈小章等) (495)Alan Watson (见Giovanni E. Mann等) (117)BLEICH Markus, SHAN Qi-Xian:上皮细胞K+通道的生理学意义与临床应用:跨上皮细胞转运的驱动力生成和K+循环 (英文) (443)BOMPADRE Silvia G., HWANG Tzyh-Chang:囊性纤维化跨膜电导调节体:ATP结合和水解门控Cl-通道(英文) (431)CAPLAN Michael J. (见ZHANG Li等) (505)Daniel C. Sigg (见萧永福等) (562)David JR Foster (见徐 民等) (42)David N. Sheppard (见李红宇等) (416)Giovanni E. Mann, Jörg Niehueser-Saran, Alan Watson, Ling Gao, Tetsuro Ishii, Patricia de Winter, Richard C. M. Siow:内皮细胞和平滑肌细胞氧化应激时Nrf2/ARE信号通路对抗氧化基因表达的调控:与动脉粥样硬化和先兆子痫的关系(英文) (117)HWANG Tzyh-Chang (见BOMPADRE Silvia G.等) (431)ISHIGURO Hiroshi, STEWARD Martin, NARUSE Satoru:胰管细胞H C O3-分泌:囊性纤维化跨膜电导调节体和SLC26转运体 (英文) (465)Jeff W. Lichtman (见Ju Lu等) (683)Joachim B. Grammer (见蔡 芳等) (27)Jörg Niehueser-Saran (见Giovanni E. Mann等) (117)Ju Lu, Jeff W. Lichtman:神经肌肉接头研究世纪回顾 (英文) (683)Ling Gao (见Giovanni E. Mann等) (117)MAENO Emi (见SHIMIZU Takahiro等) (512)NARUSE Satoru (见ISHIGURO Hiroshi等) (465)OKADA Yasunobu (见SHIMIZU Takahiro等) (512)Patricia de Winter (见Giovanni E. Mann等) (117)Philip H. -S. Jen (见栾瑞红等) (805)Prem KUMAR:颈动脉体对化学信号的换能作用(英文)... (128)QUINTON Paul M.:囊性纤维化:太多NaCl,太少HCO3-(英文) (397)Richard C. M. Siow (见Giovanni E. Mann等) (117)Sebnem Tuncdemir (见陈功等) (697)SHAN Qi-Xian (见BLEICH Markus等) (443)SHIMIZU Takahiro, MAENO Emi, OKADA Yasunobu:持续性细胞皱缩在人上皮细胞凋亡过程中的必要性 (英文).. (512)STEWARD Martin (见ISHIGURO Hiroshi等) (465)Tetsuro Ishii (见Giovanni E. Mann等) (117)ZHANG Li, CAPLAN Michael J.:极化上皮细胞中转运蛋白的分选 (英文) (505)二 画丁银元 (见李妙龄等) (858)三 画习瑾昆, 金元哲, 崔勋, 徐哲龙:心肌再灌注损伤保护的机制和策略 (英文) (553)于晓江 (见臧伟进等) (593)于海玲, 安 英, 姜海英, 金清华, 金元哲:单侧迷路破坏后大鼠前庭神经内侧核区氨基酸含量的变化 (英文) (71)马 妍 (见黄心璇等) (571)马 蓓 (见张琰敏等) (103)马 燕 (见朱 敏等) (197)马 鑫 (见吴恩惠等) (227)马元怡, 孔淑珍, 杨黎江, 孟金兰, 吕乐春, 何敏:大鼠黑质多巴胺能神经元的二型性 (753)马克涛 (见范 平等) (331)马季骅, 罗岸涛, 王伟平, 张培华:细胞外pH值降低可增强豚鼠心室肌细胞持续性钠电流 (233)马原野 (见杨 光等) (305)马朝林 (见金新春等) (739)马慧娟 (见高 宇等) (363)四 画井 然 (见秦 岭等) (351)孔淑珍 (见马元怡等) (753)文 文 (见张琰敏等) (103)文赛兰 (见秦 岭等) (351)毛节明 (见何 榕等) (1)王 东 (见鲁文果等) (51)王 佐 (见危当恒等) (831)王 芳 (见李建莎等) (204)王 昕 (见张 浩等) (660)王 勇 (见余剑平等) (814)王 宪 (见何 榕等) (1)王 宪 (见戴 晶等) (585)王 爽 (见张巧俊等) (183)王 喆 (见周文良等) (487)王 越 (见张晓芸等) (278)王 越, 张晓芸, 李 韶, 张 健, 赵 杰, 张万琴:蝎毒耐热蛋白对大鼠急性分离海马神经元兴奋性的影响 (英文).. (87)王 睿 (见杨广东等) (133)王云英 (见张 琳等) (845)王世强 (见徐 明等) (175)王玉红 (见师晨霞等) (19)王伟平 (见马季骅等) (233)王宝利, 梁 晖, 郑 纺, 李晓霞, 刘玉冰, 戴晨琳:重组可溶性核因子-κB受体活化因子体外抑制甲状旁腺激素诱导的破骨细胞生成 (英文) (169)王俊科 (见李敬远等) (13)王春晖 (见郭梅梅等) (163)王贵学 (见危当恒等) (831)王晓飞 (见陈小章等) (495)王晓春, 邱一华, 彭聿平:白介素-6保护小脑颗粒神经元抵抗NMDA的神经毒性作用 (英文) (150)王晓锋 (见秦 峥等) (293)王海昌 (见刘海涛等) (651)王继江 (见陈咏华等) (770)王莹萍 (见张 浩等) (660)王基平 (见徐 民等) (42)王常勇 (见李恩中等) (345)王琳琳 (见吕萍萍等) (674)王满香 (见李建莎等) (204)王福伟 (见许 萌等) (215)王靖宇 (见张晓芸等) (278)王慷慨, 肖献忠:心肌内源性保护研究中的若干问题与展望 (635)王曜晖, 郑海燕, 秦娜琳, 余上斌, 刘声远:ATP敏感钾通道参与大鼠前脂肪细胞增殖和分化 (英文) (8)邓建新, 刘 杰:严重烫伤延长大鼠心室肌细胞动作电位时程的机制 (375)邓林红 (见危当恒等) (831)邓春玉 (见余剑平等) (814)五 画付志燕, 杜春芸, 姚 扬, 刘朝巍, 田裕涛, 贺秉军, 张 涛,杨 卓:高效氯氰菊酯对大鼠海马CA3区神经元电压门控钾通道的影响 (63)兰 欢 (见蔡 芳等) (27)古靓丽 (见黄 维等) (865)史弘流 (见贺玉香等) (524)叶林奇 (见危当恒等) (831)司 瑞 (见刘海涛等) (651)司军强 (见范 平等) (331)左武麟 (见周文良等) (487)田 丹 (见朱 敏等) (197)田 丹 (见李建莎等) (204)田裕涛 (见付志燕等) (63)申晶晶, 刘长金, 李 爱, 胡新武, 陆永利, 陈 蕾, 周 莹,刘烈炬:大麻素抑制大鼠三叉神经节神经元ATP激活电流 (英文) (745)白 晶 (见谢 敏等) (94)白 晶, 刘先胜, 徐永健, 张珍祥, 谢 敏, 倪 望:细胞外信号调节激酶活化在慢性支气管哮喘大鼠气道平滑肌细胞增殖中的作用 (英文) (311)白瑞樱 (见邢 莹等) (267)石丽娟 (见汤 浩等) (534)六 画乔志梅 (见陈小默等) (851)乔健天 (见崔慧林等)............................................................(759)仲萍萍 (见贺玉香等) (524)任新瑜, 阮秋蓉, 朱大和, 朱 敏, 瞿智玲, 路 军:川芎嗪抑制血管紧张素II诱导的平滑肌细胞NF-κB激活和骨形成蛋白-2表达降低 (英文) (339)关 玥 (见周利彬等) (840)刘 丹 (见余剑平等) (814)刘 宁 (见杨 光等) (305)刘 红 (见高 原等) (382)刘 佳, 宋爱国:人手指柔性触觉感知的记忆特性 (387)刘 杰 (见邓建新等) (375)刘 持 (见秦晓群等) (454)刘 珍, 郑济芳, 杨露青, 易 岚, 胡 弼:青藤碱对吗啡依赖与戒断小鼠小脑与脊髓NO/nNOS系统的影响 (285)刘 健 (见张巧俊等) (183)刘 涛 (见黄 维等) (865)刘 莉 (见贺玉香等) (524)刘 谨 (见杨文星等) (325)刘小粉 (见杨 光等) (305)刘凤英 (见张振英等) (643)刘少君 (见阙海萍等) (791)刘长金 (见申晶晶等) (745)刘玉冰 (见王宝利等) (169)刘先胜 (见白 晶等) (311)刘先胜 (见谢 敏等) (94)刘声远 (见王曜晖等) (8)刘秀华 (见张振英等) (643)刘秀华 (见李玉珍等) (221)刘秀华:缺血后处理内源性心脏保护的研究进展 (628)刘录山 (见危当恒等) (831)刘娅萍 (见张巧俊等) (183)刘政江 (见范 平等) (331)刘轶锴 (见李恩中等) (345)刘海涛, 张海锋, 司 瑞, 张全江, 张昆茹, 郭文仪, 王海昌, 高峰:胰岛素保护缺血/再灌注心脏:PI3-K/Akt和JNKs 信号通路间的交互作用 (英文) (651)刘海瑛 (见张琰敏等) (103)刘烈炬 (见申晶晶等) (745)刘智飞 (见李妙龄等) (858)刘智飞 (见蔡 芳等) (27)刘朝巍 (见付志燕等) (63)刘新华,辛 宏,朱依谆:不仅是“益母”草:益母草的心脏保护作用 (英文) (578)危当恒, 王贵学, 唐朝君, 叶林奇, 杨 力, 邓林红, 刘录山, 王 佐, 唐朝克:狭窄血管远心端低密度脂蛋白浓度极化促进动脉粥样硬化形成 (831)向 阳 (见秦 岭等) (351)向 阳 (见秦晓群等) (454)吕 靖 (见黄 维等) (865)吕乐春 (见马元怡等) (753)吕志珍 (见徐 明等) (175)吕萍萍, 范 莹, 陈文良, 沈岳良, 朱 立, 王琳琳, 陈莹莹:环加氧酶-2抑制剂尼美舒利通过改善内皮功能和增加NO883含量对抗大鼠心肌氧化应激损伤 (英文) (674)孙 岚 (见高 放等) (821)孙 威 (见何 榕等) (1)孙 捷 (见高 莉等) (58)孙 蕾 (见黄 维等) (865)孙 蕾 (见臧伟进等) (593)孙心德 (见杨文伟等) (784)孙心德 (见栾瑞红等) (805)孙华英 (见杨 光等) (305)孙俊辉:蛋白质巯基亚硝基化参与调控一氧化氮介导的心肌缺血预适应 (英文) (544)孙继虎 (见晏妮等) (240)安 英 (见于海玲等) (71)师晨霞, 王玉红, 董 芳, 张永健, 许彦芳:压力负荷性心衰小鼠左心室跨壁L-型钙电流的变化 (19)成大欣 (见李 晖等) (299)曲爱娟 (见何 榕等) (1)朱 立 (见吕萍萍等) (674)朱 敏 (见任新瑜等) (339)朱 敏 (见李建莎等) (204)朱 敏, 李建莎, 田 丹, 马 燕, 李娜萍, 吴人亮:糖原合酶激酶3β和腺瘤性结肠息肉病蛋白在气道上皮细胞机械损伤修复过程的时空分布 (197)朱大和 (见任新瑜等) (339)朱小南 (见余剑平等) (814)朱进霞, 陈小章:白凤丸及其主要活性成分对机体及胃肠道上皮细胞离子转运功能的影响 (英文) (477)朱依谆 (见刘新华等) (578)朱忠良 (见李 晖等) (299)朱玲玲 (见吴恩惠等) (227)朱玲玲 (见赵 彤等) (273)朱晓琳 (见秦晓群等) (454)汤 浩, 崔桂英, 石丽娟, 高青华, 曹 宇:川芎嗪抗链霉素耳毒性作用及其对豚鼠耳蜗外毛细胞钾通道的影响 (英文) (534)汤晓军 (见李 董等) (35)许 盈 (见魏义明等) (765)许 萌, 武宇明, 李 茜, 王福伟, 何瑞荣:硫化氢对离体豚鼠乳头状肌的电生理效应 (英文) (215)许 燕 (见邢 莹等) (267)许彦芳 (见师晨霞等) (19)许德义 (见徐 民等) (42)邢 莹, 白瑞樱, 鄢文海, 韩雪飞, 段 萍, 许 燕, 樊志刚:人骨髓间充质干细胞向神经细胞分化过程中Notch通路信号分子表达的变化 (267)闫剑群 (见雷 琦等) (260)阮怀珍 (见黄 维等) (865)阮秋蓉 (见任新瑜等) (339)阮晔纯 (见周文良等) (487)齐永芬 (见龚永生等) (210)七 画严 进 (见晏 妮等) (240)严珊珊 (见贺玉香等) (524)何 进 (见余剑平等) (814)何 敏 (见马元怡等) (753)何 榕, 曲爱娟, 毛节明, 王 宪, 孙 威:胰岛素增强糖基化白蛋白对大鼠血管平滑肌细胞的促增殖作用 (英文).. (1)何 琼 (见陈小章等) (495)何瑞荣 (见许 萌等) (215)余上斌 (见王曜晖等) (8)余志斌 (见张 琳等) (845)余志斌 (见李 辉等) (369)余剑平, 何 进, 刘 丹, 邓春玉, 朱小南, 汪雪兰, 王 勇, 陈汝筑:κ-银环蛇毒素敏感的烟碱受体激活引起的去甲肾上腺素释放参与烟碱诱导的长时程增强样反应 (英文).. (814)吴 霞 (见陈 功等) (697)吴人亮 (见朱 敏等) (197)吴人亮 (见李建莎等) (204)吴小脉 (见龚永生等) (210)吴飞健 (见栾瑞红等) (805)吴中海 (见秦 峥等) (293)吴立玲 (见李 丽等) (614)吴恩惠, 李海生, 赵 彤, 樊俊蝶, 马 鑫, 熊 雷, 李伍举,朱玲玲, 范 明:低氧对人骨髓间充质干细胞基因表达谱的影响 (227)吴博威 (见崔香丽等) (667)宋 亮 (见李 晖等) (299)宋 峣 (见徐 明等) (175)宋 智 (见秦 岭等) (351)宋立林 (见周利彬等) (840)宋光耀 (见高 宇等) (363)宋美英 (见黄 维等) (865)宋爱国 (见刘 佳等) (387)张 勃 (见黄 维等) (865)张 洁 (见杨 光等) (305)张 健 (见王 越等) (87)张 健 (见张晓芸等) (278)张 浩, 杨长瑛, 王莹萍, 王 昕, 崔 芳, 周兆年, 张 翼:间歇性低压低氧方式对发育大鼠心脏缺血/再灌注损伤的影响 (英文) (660)张 涛 (见付志燕等) (63)张 涛 (见李 董等) (35)张 琳 (见贺 明等) (796)张 琳, 王云英, 余志斌:模拟失重降低大鼠心肌细胞对异丙肾上腺素的反应性 (845)张 磊 (见黄 维等) (865)张 翼 (见张 浩等) (660)张 翼 (见周利彬等) (840)张 翼, 杨黄恬, 周兆年:间歇性低氧适应的心脏保护........ (601)张 曦 (见黄 维等) (865)《生理学报》第59卷 作者索引884生理学报Acta Physiologica Sinica, December 25, 2007, 59(6): 881-895张万琴 (见王 越等) (87)张万琴 (见张晓芸等) (278)张文杰 (见高 宇等) (363)张文德 (见杨 光等) (305)张世庆 (见李恩中等) (345)张巧俊, 高 蕊, 刘 健, 刘娅萍, 王 爽:帕金森病大鼠中缝背核5-羟色胺能神经元电活动的变化 (英文) (183)张幼怡 (见徐 明等) (175)张永健 (见师晨霞等) (19)张立藩 (见高 放等) (821)张全江 (见刘海涛等) (651)张志琴 (见范 平等) (331)张苏明 (见鲁文果等) (51)张奇兰 (见杨文星等) (325)张季平 (见杨文伟等) (784)张学明 (见李恩中等) (345)张昆茹 (见刘海涛等) (651)张珍祥 (见白 晶等) (311)张珍祥 (见赵建平等) (157)张珍祥 (见赵建平等) (319)张珍祥 (见谢 敏等) (94)张振英, 刘秀华, 郭晓笋, 刘凤英:钙网蛋白参与缺血后处理减轻大鼠骨骼肌缺血/再灌注损伤 (643)张晓芸 (见王 越等) (87)张晓芸, 王 越, 张 健, 王靖宇, 赵 杰, 张万琴, 李 韶:蝎毒耐热蛋白对大鼠海马神经元钠通道的抑制作用...... (278)张海锋 (见刘海涛等) (651)张培华 (见马季骅等) (233)张景琨 (见羡晓辉等) (357)张琰敏, 马 蓓, 高文元, 文 文, 刘海瑛:谷氨酸受体在噪声所致豚鼠螺旋神经节细胞损伤中的作用 (103)张翠萍 (见赵 彤等) (273)李 丽 (见范 平等) (331)李 丽, 吴立玲:腺苷酸活化蛋白激酶在脂联素心血管保护效应中的作用 (614)李 岑 (见秦 岭等) (351)李 杨, 袁 斌, 唐敬师:电刺激和损毁丘脑中央下核对大鼠福尔马林诱发伤害性行为的影响 (英文) (777)李 松 (见阙海萍等) (791)李 欣 (见阙海萍等) (791)李 茜 (见许 萌等) (215)李 晖, 李清红, 朱忠良, 陈 蕊, 成大欣, 蔡 青, 贾 宁,宋 亮:产前束缚应激子代大鼠海马神经颗粒素表达降 (299)李 爱 (见申晶晶等) (745)李 董, 杜春芸, 汤晓军, 金英雄, 雷 霆, 姚 扬, 杨 卓,张涛:大鼠缺血性脑损伤引起学习记忆障碍及心率变异性改变 (35)李 辉, 焦 博, 余志斌:萎缩比目鱼肌间断强直收缩疲劳后恢复速率的影响因素 (369)李 韶 (见王 越等)..............................................................(87)李 韶 (见张晓芸等) (278)李 澜 (见李恩中等) (345)李永波 (见杨文星等) (325)李玉珍, 刘秀华, 蔡莉蓉:串珠素表达下调参与低氧对大鼠心肌微血管内皮细胞增殖的抑制作用 (英文) (221)李伍举 (见吴恩惠等) (227)李红宇, 蔡志伟, 陈正豪, 鞠 敏, 徐 喆, David N. Sheppard:囊性纤维化跨膜转运调节体氯离子通道——跨上皮离子转运的多功能引擎 (英文) (416)李妙龄 (见蔡 芳等) (27)李妙龄, 曾晓荣, 杨 艳, 刘智飞, 丁银元, 周 文, 裴 杰:一种改进的人体心房肌细胞分离方法 (858)李建莎 (见朱 敏等) (197)李建莎, 朱 敏, 田 丹, 王满香, 王 芳, 李娜萍, 吴人亮:糖原合酶激酶3β以细胞周期蛋白D1依赖性方式引发人肺腺癌细胞A549细胞周期阻滞 (英文) (204)李娜萍 (见朱 敏等) (197)李娜萍 (见李建莎等) (204)李恩中, 李德雪, 张世庆, 李澜, 王常勇, 张学明, 鲁景艳, 刘轶锴:隐睾小鼠与正常成年小鼠睾丸蛋白表达谱的差异分析 (345)李晓霞 (见王宝利等) (169)李海生 (见吴恩惠等) (227)李清红 (见李 晖等) (299)李敬远, 王俊科, 曾因明:外周苯二氮受体激动剂Ro5-4864抑制大鼠心肌细胞线粒体通透性转换 (13)李葆明 (见金新春等) (739)李鹏云 (见蔡 芳等) (27)李潇寒 (见晏 妮等) (240)李德雪 (见李恩中等) (345)杜建阳 (见周文良等) (487)杜春芸 (见付志燕等) (63)杜春芸 (见李 董等) (35)杨 力 (见危当恒等) (831)杨 光, 刘小粉, 刘 宁, 张 洁, 郑佳威, 孙华英, 张文德, 马原野:慢性吗啡给予、戒断及再给药过程中大鼠海马感觉门控的动态变化 (305)杨 卓 (见付志燕等) (63)杨 卓 (见李 董等) (35)杨 艳 (见李妙龄等) (858)杨 艳 (见蔡 芳等) (27)杨 勤, 韩 冰, 谢汝佳, 程明亮:骨形态发生蛋白-7及抑制性Smads在糖尿病肾病发生发展中的表达变化 (190)杨 慧 (见曹 倩等) (253)杨广东, 王 睿:硫化氢与细胞的增殖和凋亡 (英文) (133)杨文伟, 周晓明, 张季平, 孙心德:电刺激大鼠内侧额叶前皮质对听皮层神经元频率感受野可塑性的调制 (英文)..(784)杨文星, 张奇兰, 呼海燕, 刘 谨, 李永波, 周 华, 郑 煜:内源性一氧化碳参与呼吸节律调节 (325)杨长瑛 (见张 浩等) (660)杨雪娟 (见雷 琦等) (260)杨黄恬 (见张 翼等) (601)885杨黎江 (见马元怡等) (753)杨露青 (见刘 珍等) (285)汪 涛 (见赵建平等) (157)汪 涛 (见赵建平等) (319)汪雪兰 (见余剑平等) (814)沈岳良 (见吕萍萍等) (674)沈金宝 (见高 莉等) (58)肖献忠 (见王慷慨等) (635)辛 宏 (见刘新华等) (578)辛 艳 (见林凡凯等) (79)邱一华 (见林树新等) (150)陆永利 (见申晶晶等) (745)陆利民 (见贺 明等) (796)陈 功, 吴 霞, Sebnem Tuncdemir:细胞黏附和突触发生 (英文) (697)陈 红 (见鲁文果等) (51)陈 坷 (见雷 琦等) (260)陈 俊 (见赵建平等) (157)陈 晨 (见赵玉峰) (247)陈 蕊 (见李 晖等) (299)陈 蕾 (见申晶晶等) (745)陈 曦:溶血磷脂酸受体及下游信号通路在心脏细胞生长中的调节作用 (619)陈士新(见谢 敏等) (94)陈小章(见朱进霞等) (477)陈小章(见周文良等) (487)陈小章, 何 琼, AJONUMA Louis-Chukwuemeka, 王晓飞:上皮细胞离子通道对雌性生殖道内液体微环境的调节作用:对生殖与不孕的影响(英文) (495)陈小默, 乔志梅, 高上凯, 洪 波:在体神经元胞外记录用于大脑皮层可塑性研究 (851)陈文良 (见吕萍萍等) (674)陈正豪 (见李红宇等) (416)陈伟强 (见徐 民等) (42)陈汝筑 (见余剑平等) (814)陈还珍 (见崔香丽等) (667)陈咏华, 侯丽丽, 王继江:电突触电流在单个吸气性气管运动神经元中的选择性显示 (英文) (770)陈建国 (见林凡凯等) (79)陈莹莹 (见吕萍萍等) (674)八 画单保恩 (见高 莉等) (58)周 专 (见黄 维等) (865)周 文 (见李妙龄等) (858)周 文 (见蔡 芳等) (27)周 华 (见杨文星等) (325)周 宇 (见高 宇等) (363)周 莹 (见申晶晶等) (745)周文良, 左武麟, 阮晔纯, 王 喆, 杜建阳, 熊 原, 陈小章:胞外ATP在男性生殖道中的作用 (英文) (487)周兆年 (见张 浩等)............................................................(660)周兆年 (见张 翼等) (601)周利彬, 宋立林, 关 玥, 郭书梅, 袁 芳, 张 翼:雌二醇对家兔窦房结自律细胞的电生理学效应 (英文) (840)周志刚 (见赵建平等) (157)周志刚 (见赵建平等) (319)周晓红 (见羡晓辉等) (357)周晓明 (见杨文伟等) (784)呼海燕 (见杨文星等) (325)孟金兰 (见马元怡等) (753)屈 飞 (见秦晓群等) (454)庞永政 (见龚永生等) (210)於 峻 (见林树新等) (141)易 岚 (见刘 珍等) (285)林凡凯, 辛 艳, 高东明, 熊 哲, 陈建国:电刺激大鼠束旁核对底丘脑核和丘脑腹内侧核神经元的影响 (79)林树新, 於 峻:花生四烯酸代谢物对呼吸道感受器的作用(英文) (141)武宇明 (见许 萌等) (215)罗 蕾 (见高 原等) (382)罗岸涛 (见马季骅等) (233)范 平, 李 丽, 刘政江, 司军强, 张志琴, 赵 磊, 马克涛:一氧化氮和K+通道参与乙酰胆碱引起的大鼠离体输精管平滑肌细胞超极化 (英文) (331)范 明 (见吴恩惠等) (227)范 明 (见赵 彤等) (273)范 莹 (见吕萍萍等) (674)范小芳 (见龚永生等) (210)郑 纺 (见王宝利等) (169)郑 煜 (见杨文星等) (325)郑永添 (见黄心璇等) (571)郑佳威 (见杨 光等) (305)郑济芳 (见刘 珍等) (285)郑海燕 (见王曜晖等) (8)金 木 (见黄 维等) (865)金元哲 (见习瑾昆等) (553)金元哲 (见于海玲等) (71)金英雄 (见李 董等) (35)金清华 (见于海玲等) (71)金新春, 马朝林, 李葆明:α2A肾上腺素受体激动剂guanfacine 增强大鼠空间学习能力而不影响条件性恐惧记忆 (英文) (739)九 画侯丽丽 (见陈咏华等) (770)俞昌喜 (见魏义明等) (765)修 云 (见黄 维等) (865)姚 扬 (见付志燕等) (63)姚 扬 (见李 董等) (35)姚 泰 (见贺 明等) (796)姜海英 (见于海玲等) (71)施京红 (见雷 琦等) (260)段 萍 (见邢 莹等) (267)《生理学报》第59卷 作者索引886Acta Physiologica Sinica, December 25, 2007, 59(6): 881-895洪 波 (见陈小默等) (851)胡 弼 (见刘 珍等) (285)胡红玲 (见赵建平等) (157)胡红玲 (见赵建平等) (319)胡良冈 (见龚永生等) (210)胡新武 (见申晶晶等) (745)贺 明, 黄娅林, 张 琳, 姚 泰, 陆利民:肾素(原)受体在大鼠肾小球系膜细胞和肾脏的表达 (796)贺玉香, 仲萍萍, 严珊珊, 刘 莉, 史弘流, 曾木圣, 夏云飞:DNA-PK的活性与鼻咽癌细胞株CNE1/CNE2放射敏感性的关系 (英文) (524)贺秉军 (见付志燕等) (63)赵 彤 (见吴恩惠等) (227)赵 彤, 张翠萍, 朱玲玲, 靳 冰, 黄 欣, 范 明:低氧促进神经干细胞向多巴胺能神经元分化 (273)赵 杰 (见王 越等) (87)赵 杰 (见张晓芸等) (278)赵 磊 (见范 平等) (331)赵玉峰, 陈 晨:脂肪细胞对胰岛β细胞功能的内分泌调节作用 (英文) (247)赵建平, 周志刚, 胡红玲, 郭 治, 汪 涛, 甄国华, 张珍祥:低氧条件下大鼠肺动脉平滑肌细胞中活性氧与低氧诱导因子-1α和细胞增殖的关系 (英文) (319)赵建平, 郭 治, 周志刚, 陈 俊, 胡红玲, 汪 涛, 张珍祥:线粒体ATP敏感钾通道对大鼠肺动脉平滑肌细胞低氧诱导因子-1α表达及细胞增殖的作用 (157)赵春礼 (见曹 倩等) (253)赵焕英 (见曹 倩等) (253)赵燕婷 (见徐 明等) (175)郝天袍 (见徐 明等) (175)十 画倪 望 (见白 晶等) (311)倪 望 (见谢 敏等) (94)倪 鑫 (见晏 妮等) (240)凌亦凌 (见羡晓辉等) (357)唐 娟 (见蒋建利等) (517)唐承薇 (见郭梅梅等) (163)唐敬师 (见李 杨等) (777)唐朝克 (见危当恒等) (831)唐朝君 (见危当恒等) (831)唐朝枢 (见龚永生等) (210)夏云飞 (见贺玉香等) (524)徐 民, 陈伟强, 王基平, David JR Foster, 许德义:大鼠中央杏仁核5-HT3受体参与胸腺功能调制 (英文) (42)徐 明, 赵燕婷, 宋峣, 郝天袍, 吕志珍, 韩启德, 王世强, 张幼怡:α1-肾上腺素受体激活大鼠心脏腺苷酸活化蛋白激酶 (英文) (175)徐 喆 (见李红宇等) (416)徐永健 (见白 晶等) (311)徐永健 (见谢 敏等) (94)徐哲龙 (见习瑾昆等)............................................................(553)晏 妮, 李潇寒, 程 祺, 严 进, 倪 鑫, 孙继虎:瞬时外向钾电流的降低介导了慢性压迫背根神经节细胞兴奋性的升高. (240)栾瑞红, 吴飞健, Philip H. -S. Jen, 孙心德:GABA能抑制调制大棕蝠下丘神经元对串声刺激的强度敏感性 (英文)...... (805)秦 岭 (见秦晓群等) (454)秦 岭, 宋 智, 文赛兰, 井 然, 李 岑, 向 阳, 秦晓群:间歇性低氧对肥胖小鼠瘦素及其受体表达的影响 (351)秦 峥, 吴中海, 王晓锋:5-HT1A受体对新生大鼠离体延髓脑片呼吸节律性放电的调制 (293)秦娜琳 (见王曜晖等) (8)秦晓群 (见秦 岭等) (351)秦晓群, 向 阳, 刘 持, 谭宇蓉, 屈 飞, 彭丽花, 朱晓琳, 秦岭:支气管上皮细胞在气道高反应中的作用(英文).... (454)袁 芳 (见周利彬等) (840)袁 斌 (见李 杨等) (777)贾 宁 (见李 晖等) (299)郭 宁 (见黄 维等) (865)郭 治 (见赵建平等) (157)郭 治 (见赵建平等) (319)郭书梅 (见周利彬等) (840)郭文仪 (见刘海涛等) (651)郭晓笋 (见张振英等) (643)郭梅梅, 黄明慧, 王春晖, 唐承薇:猕猴发育过程中肠肝组织血管活性肠肽及其受体的变化 (163)高 宇, 宋光耀, 马慧娟, 张文杰, 周 宇:长期高饱和、高不饱和脂肪酸饮食诱导胰岛素抵抗大鼠肾动脉舒张和收缩功能的变化 (英文) (363)高 放, 张立藩, 黄威权, 孙 岚:慢性阻断血管紧张素II 1型受体不能完全防止模拟失重大鼠血管的适应性结构变化 (821)高 原, 罗 蕾, 刘 红:大鼠单根近端肾小管Na+-K+-ATPase活性测定方法的改进 (英文) (382)高 峰 (见刘海涛等) (651)高 莉, 沈金宝, 孙 捷, 单保恩:雷氏大疣蛛毒液对人肝癌HepG2细胞p21基因表达的影响 (英文) (58)高 蕊 (见张巧俊等) (183)高上凯 (见陈小默等) (851)高文元 (见张琰敏等) (103)高东明 (见林凡凯等) (79)高青华 (见汤 浩等) (534)十一 画崔 芳 (见张 浩等) (660)崔 勋 (见习瑾昆等) (553)崔香丽, 陈还珍, 吴博威:氨甲酰胆碱通过M2胆碱能受体对大鼠心肌细胞发挥正性肌力作用 (英文) (667)崔桂英 (见汤 浩等) (534)崔慧林, 乔健天:溶血磷脂酸对离体培养的大鼠胚胎神经干细胞向神经胶质细胞分化的影响 (英文) (759)887《生理学报》第59卷 作者索引曹 宇 (见汤 浩等) (534)曹 倩, 魏灵荣, 鲁玲玲, 赵春礼, 赵焕英, 杨 慧:星形胶质细胞通过谷胱甘肽保护MN9D细胞抵抗鱼藤酮所致氧化应激 (英文) (253)梁 晖 (见王宝利等) (169)萧永福, Daniel C. Sigg:用生物学方法重建心脏起搏点的研究进展 (英文) (562)黄 欣 (见赵 彤等) (273)黄 维, 黄宏平, 穆 玉, 张 磊, 金 木, 吕 靖, 古靓丽, 修 云, 张 勃, 郭 宁, 刘 涛, 孙 蕾, 宋美英, 张 曦,阮怀珍, 周 专:中枢神经系统去甲肾上腺素分泌的实时检测 (865)黄心璇, 马 妍, 郑永添, 黄德明:雌激素的心脏保护作用——与β1-肾上腺素受体的相互作用及其信号通路 (英文) (571)黄宏平 (见黄 维等) (865)黄明慧 (见郭梅梅等) (163)黄威权 (见高 放等) (821)黄娅林 (见贺 明等) (796)黄新莉 (见羡晓辉等) (357)黄德明 (见黄心璇等) (571)龚永生, 范小芳, 吴小脉, 胡良冈, 唐朝枢, 庞永政, 齐永芬:Intermedin/adrenomedullin 2及其受体在慢性低氧性肺动脉高压大鼠右心室的表达变化 (210)十二 画彭聿平 (见林树新等) (150)彭丽花 (见秦晓群等) (454)曾木圣 (见贺玉香等) (524)曾因明 (见李敬远等) (13)曾晓荣 (见李妙龄等) (858)曾晓荣 (见蔡 芳等) (27)焦 博 (见李 辉等) (369)程 俊 (见蔡 芳等) (27)程 祺 (见晏 妮等) (240)程明亮 (见杨 勤等) (190)羡晓辉, 黄新莉, 周晓红, 张景琨, 凌亦凌:硫化氢与内毒素血症大鼠心肌损伤的关系 (357)董 芳 (见师晨霞等) (19)蒋建利, 唐 娟:CD147相互作用蛋白及其细胞生物学功能(英文) (517)谢 敏 (见白晶等) (311)谢 敏, 刘先胜, 徐永健, 张珍祥, 白 晶, 倪 望, 陈士新:细胞外信号调节激酶1/2信号通路在慢性哮喘模型大鼠支气管平滑肌细胞迁移功能变化中的调控作用 (94)谢汝佳 (见杨 勤等) (190)韩 冰 (见杨 勤等) (190)韩启德 (见徐 明等) (175)韩雪飞 (见邢 莹等) (267)鲁文果, 陈 红, 王 东, 黎逢光, 张苏明:小鼠胚胎干细胞移植入成体大鼠脑内的区域特异性存活与分化 (英文).... (51)鲁玲玲 (见曹 倩等) (253)鲁景艳 (见李恩中等) (345)十三 画甄国华 (见赵建平等) (319)路 军 (见任新瑜等) (339)鄢文海 (见邢 莹等) (267)阙海萍, 李 欣, 李 松, 刘少君:低浓度神经生长因子存在下GPI-1046刺激鸡胚神经节突起生长 (英文) (791)雷 琦, 闫剑群, 施京红, 杨雪娟, 陈 坷:味觉刺激引起大鼠臂旁核神经元抑制性反应 (英文) (260)雷 霆 (见李 董等) (35)靳 冰 (见赵 彤等) (273)十四 画熊 原 (见周文良等) (487)熊 哲 (见林凡凯等) (79)熊 雷 (见吴恩惠等) (227)臧伟进, 孙 蕾, 于晓江:腺苷和乙酰胆碱后适应诱导的心肌保护作用 (英文) (593)蔡 芳, 李鹏云, 杨 艳, 刘智飞, 李妙龄, 周 文, 裴 杰, 程俊, 兰 欢, Joachim B. Grammer, 曾晓荣:猪冠状动脉平滑肌细胞的自发瞬时外向电流的特性 (英文) (27)蔡 青 (见李 晖等) (299)蔡志伟 (见李红宇等) (416)蔡莉蓉 (见李玉珍等) (221)裴 杰 (见李妙龄等) (858)裴 杰 (见蔡 芳等) (27)谭宇蓉 (见秦晓群等) (454)十五 画樊志刚 (见邢 莹等) (267)樊俊蝶 (见吴恩惠等) (227)黎逢光 (见鲁文果等) (51)十六 画穆 玉 (见黄 维等) (865)十七 画戴 晶, 王 宪:同型半胱氨酸在心血管疾病中的免疫调节作用 (英文) (585)戴晨琳 (见王宝利等) (169)鞠 敏 (见李红宇等) (416)魏义明, 许盈, 俞昌喜:褪黑素对吗啡戒断小鼠下丘脑弓状核和中脑导水管周围灰质中β-内啡肽含量的影响..(765)魏灵荣 (见曹 倩等) (253)十八 画瞿智玲 (见任新瑜等) (339)。

The Contemporary Theory of MetaphorGeorge Lakoff(c) Copyright George Lakoff, 1992To Appear in Ortony, Andrew (ed.) Metaphor and Thought (2nd edition), Cambridge University Press.Do not go gentle into that good night. -Dylan ThomasDeath is the mother of beauty . . . -Wallace Stevens, Sunday Morning IntroductionThese famous lines by Thomas and Stevens are examples of what classical theorists, at least since Aristotle, have referred to as metaphor: instances of novel poetic language in which words like mother,go, and night are not used in their normal everyday senses. In classical theories of language, metaphor was seen as a matter of language not thought. Metaphorical expressions were assumed to be mutually exclusive with the realm of ordinary everyday language: everyday language had no metaphor, and metaphor used mechanisms outside the realm of everyday conventional language. The classical theory was taken so much for granted over the centuries that many people didn’t realize that it was just a theory. The theory was not merely taken to be true, but came to be taken as definitional. The word metaphor was defined as a novel or poetic linguistic expression where one or more words for a concept are used outside of its normal conventional meaning to express a similar concept. But such issues are not matters for definitions; they are empirical questions. As a cognitive scientist and a linguist, one asks: What are the generalizations governing the linguistic expressions re ferred to classically as poetic metaphors? When this question is answered rigorously, the classical theory turns out to be false. The generalizations governing poetic metaphorical expressions are not in language, but in thought: They are general map pings across conceptual domains. Moreover, these general princi ples which take the form of conceptual mappings, apply not just to novel poetic expressions, but to much of ordinary everyday language. In short, the locus of metaphor is not in language at all, but in the way we conceptualize one mental domain in terms of another. The general theory of metaphor is given by characterizing such cross-domain mappings. And in the process, everyday abstract concepts like time, states, change, causation, and pur pose also turn out to be metaphorical. The result is that metaphor (that is, cross-domain mapping) is absolutely central to ordinary natural language semantics, and that the study of literary metaphor is an extension of the study of everyday metaphor. Everyday metaphor is characterized by a huge system of thousands of cross-domain mappings, and this system is made use of in novel metaphor. Because of these empirical results, the word metaphor has come to be used differently in contemporary metaphor research. The word metaphor has come to mean a cross-domain mapping in the conceptual system. The term metaphorical expression refers to a linguisticexpression (a word, phrase, or sentence) that is the surface realization of such a cross-domain mapping (this is what the word metaphor referred to in the old theory). I will adopt the contemporary usage throughout this chapter. Experimental results demonstrating the cognitive reali ty of the extensive system of metaphorical mappings are discussed by Gibbs (this volume). Mark Turner’s 1987 book, Death is the mother of beauty, whose title comes from Stevens’great line, demonstrates in detail how that line uses the ordinary system of everyday mappings. For further examples of how literary metaphor makes use of the ordinary metaphor system, see More Than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor, by Lakoff and Turner (1989) and Reading Minds: The Study of English in the Age of Cognitive Science, by Turner (1991). Since the everyday metaphor system is central to the understanding of poetic metaphor, we will begin with the everyday system and then turn to poetic examples.Homage To ReddyThe contemporary theory that metaphor is primarily conceptual, conventional, and part of the ordinary system of thought and language can be traced to Michael Reddy’s (this volume) now classic paper, The Conduit Metaphor,which first appeared in the first edition of this collection. Reddy did far more in that paper than he modestly suggested. With a single, thoroughly analyzed example, he allowed us to see, albeit in a restricted domain, that ordinary everyday English is largely metaphorical, dispelling once and for all the traditional view that metaphor is primarily in the realm of poetic or figurative language. Reddy showed, for a single very significant case, that the locus of metaphor is thought, not language, that metaphor is a major and indispensable part of our ordinary, conventional way of conceptualizing the world, and that our everyday behavior reflects our metaphorical understanding of experience. Though other theorists had noticed some of these characteristics of metaphor, Reddy was the first to demonstrate it by rigorous linguistic analysis, stating generalizations over voluminous examples. Reddy’s chapter on how we conceptualize the concept of communication by metaphor gave us a tiny glimpse of an enormous system of conceptual metaphor. Since its appearance, an entire branch of linguis tics and cognitive science has developed to study systems of metaphorical thought that we use to reason, that we base our actions on, and that underlie a great deal of the structure of language. The bulk of the chapters in this book were written before the development of the contemporary field of metaphor research. My chapter will therefore contradict much that appears in the others, many of which make certain assumptions that were widely taken for granted in 1977. A major assumption that is challenged by contemporary research is the traditional division between literal and figurative language, with metaphor as a kind of figurative language. This entails, by definition, that: What is literal is not metaphorical. In fact, the word literal has traditionally been used with one or more of a set of assumptions that have since proved to be false:Traditional false assumptions•All everyday conventional language is literal, and none is metaphorical.•All subject matter can be comprehended literally, without metaphor.•Only literal language can be contingently true or false.•All definitions given in the lexicon of a language are literal, not metaphorical.•The concepts used in the grammar of a language are all literal; none are metaphorical.The big difference between the contemporary theory and views of metaphor prior to Reddy’s work lies in this set of assumptions. The reason for the difference is that, in the intervening years, a huge system of everyday, convention al, conceptual metaphors has been discovered. It is a system of metaphor that structures our everyday conceptual system, including most abstract concepts, and that lies behind much of everyday language. The discovery of this enormous metaphor system has destroyed the traditional literal-figurative distinction, since the term literal,as used in defining the traditional distinction, carries with it all those false assumptions. A major difference between the contemporary theory and the classical one is based on the old literal-figurative distinction. Given that distinction, one might think that one arrives at a metaphorical interpretation of a sentence by starting with the literal meaning and applying some algorithmic process to it (see Searle, this volume). Though there do exist cases where something like this happens, this is not in general how metaphor works, as we shall see shortly.What is not metaphoricalAlthough the old literal-metaphorical distinction was based on assumptions that have proved to be false, one can make a different sort of literal-metaphorical distinction: those concepts that are not comprehended via conceptual metaphor might be called literal. Thus, while I will argue that a great many common concepts like causation and purpose are metaphorical, there is nonetheless an extensive range of nonmetaphorical concepts. Thus, a sentence like The balloon went up is not metaphorical, nor is the old philosopher’s favorite The cat is on the mat.But as soon as one gets away from concrete physical experience and starting talking about abstractions or emotions, metaphorical understanding is the norm.The Contemporary Theory: Some ExamplesLet us now turn to some examples that are illustrative of contemporary metaphor research. They will mostly come from the domain of everyday conventional metaphor, since that has been the main focus of the research. I will turn to the discussion of poetic metaphor only after I have discussed the conventional system, since knowledge of the conventional system is needed to make sense of most of the poetic cases. The evidence for the existence of a system of conventional conceptual metaphors is of five types: -Generalizations governing polysemy, that is, the use of words with a number of related meanings.-Generalizations governing inference patterns, that is, cases where a pattern of inferences from one conceptual domain is used in another domain.-Generalizations governing novel metaphorical language (see, Lakoff & Turner, 1989).-Generalizations governing patterns of semantic change (see, Sweetser, 1990).-Psycholinguistic experiments (see, Gibbs, 1990, this volume).We will primarily be discussing the first three of these sources of evidence, since they are the most robust.Conceptual MetaphorImagine a love relationship described as follows: Our relationship has hit a dead-end street.Here love is being conceptualized as a journey, with the implication that the relationship is stalled, that the lovers cannot keep going the way they’ve been going, that they must turn back, or abandon the relationship altogether. This is not an isolated case. English has many everyday expressions that are based on a conceptualization of love as a journey, and they are used not just for talking about love, but for reasoning about it as well. Some are necessarily about love; others can be understood that way: Look how far we’ve come. It’s been a long, bumpy road. We can’t turn back now. We’re at a crossroads. We may have to go our separate ways. The relationship isn’t going anywhere. We’re spinning our wheels. Our relationship is off the track. The marriage is on the rocks. We may have to bail out of this relationship. These are ordinary, everyday English expressions. They are not poetic, nor are they necessarily used for special rhetorical effect. Those like Look how far we’ve come, which aren’t necessarily about love, can readily be understood as being about love. As a linguist and a cognitive scientist, I ask two commonplace questions:•Is there a general principle governing how these linguistic expressions about journeys are used to characterize love?•Is there a general principle governing how our patterns of inference about journeys are used to reason about love when expressions such as these are used?The answer to both is yes. Indeed, there is a single general principle that answers both questions. But it is a general principle that is neither part of the grammar of English, nor the English lexicon. Rather, it is part of the conceptual system underlying English: It is a principle for under standing the domain of love in terms of the domain of journeys. The principle can be stated informally as a metaphorical scenario: The lovers are travelers on a journey together, with their common life goals seen as destinations to be reached. The relationship is their vehicle, and it allows them to pursue those common goals together. The relationship is seen as fulfilling its purpose as long as it allows them to make progress toward their common goals. The journey isn’t easy. There are impediments, and there are places (crossroads) where a decision has to be made about which direction to go in and whether to keep traveling together. The metaphor involves understanding one domain of experience, love, in terms of a very different domain of experience, journeys. More technically, the metaphor can be understood as a mapping (in the mathematical sense) from a source domain (in this case, journeys) to a target domain (in this case, love). The mapping is tightly structured. There are ontological correspondences, according to which entities in the domain of love (e.g., the lovers, their common goals, their difficulties, the love relationship, etc.) correspond systematically to entities in the domain of a journey (the travelers, the vehicle, des tinations, etc.). To make it easier to remember what mappings there are in the conceptual system, Johnson and I (lakoff and Johnson, 1980) adopted a strategy for naming such mappings, using mnemonics which suggest the mapping. Mnemonic names typically (though not always) have the form: TARGET-DOMAIN IS SOURCE-DOMAIN, or alternatively, TARGET-DOMAIN AS SOURCE-DOMAIN. In this case, the name of the mapping is LOVE IS A JOURNEY. When I speak of the LOVE IS A JOURNEY metaphor, I am using a mnemonic for a set of ontological correspondences that characterize a map ping, namely:THE LOVE-AS-JOURNEY MAPPING-The lovers correspond to travelers.-The love relationship corresponds to the vehicle.-The lovers’ common goals correspond to their common destinations on the journey.-Difficulties in the relationship correspond to impediments to travel.It is a common mistake to confuse the name of the mapping, LOVE IS A JOURNEY, for the mapping itself. The mapping is the set of correspondences. Thus, whenever I refer to a metaphor by a mnemonic like LOVE IS A JOURNEY, I will be referring to such a set of correspondences. If mappings are confused with names of mappings, another misunderstanding can arise. Names of mappings commonly have a propositional form, for example, LOVE IS A JOURNEY. But the mappings themselves are not propositions. If mappings are confused with names for mappings, one might mistakenly think that, in this theory, metaphors are propositional. They are, of course, anything but that: metaphors are mappings, that is, sets of conceptual correspondences. The LOVE-AS-JOURNEY mapping is a set of ontological correspondences that characterize epistemic correspondences by mapping knowledge about journeys onto knowledge about love. Such correspondences permit us to reason about love using the knowledge we use to reason about journeys. Let us take an example. Consider the expression, We’re stuck, said by one lover to another about their relationship. How is this expression about travel to be understood as being about their relationship? We’re stuck can be used of travel, and when it is, it evokes knowledge about travel. The exact knowledge may vary from person to person, but here is a typical example of the kind of knowledge evoked. The capitalized expressions represent entities n the ontology of travel, that is, in the source domain of the LOVE IS A JOURNEY mapping given above. Two TRAVELLERS are in a VEHICLE, TRAVELING WITH COMMON DESTINATIONS. The VEHICLE encounters some IMPEDIMENT and gets stuck, that is, makes it nonfunctional. If they do nothing, they will not REACH THEIR DESTINATIONS. There are a limited number of alternatives for action:•They can try to get it moving again, either by fixing it or get ting it past the IMPEDIMENT that stopped it.•They can remain in the nonfunctional VEHICLE and give up on REACHING THEIR DESTINATIONS.•They can abandon the VEHICLE.•The alternative of remaining in the nonfunctional VEHICLE takes the least effort, but does not satisfy the desire to REACH THEIR DESTINATIONS.The ontological correspondences that constitute the LOVE IS A JOURNEY metaphor map the ontology of travel onto the ontology of love. In doing so, they map this scenario about travel onto a corresponding love scenario in which the corresponding alternatives for action are seen. Here is the corresponding love scenario that results from applying the correspondences to this knowledge structure. The target domain entities that are mapped by the correspondences are capitalized:Two LOVERS are in a LOVE RELATIONSHIP, PURSUING COMMON LIFE GOALS. The RELATIONSHIP encounters some DIFFICULTY, which makes it nonfunctional. If they do nothing, they will not be able to ACHIEVE THEIR LIFE GOALS. There are a limited number of alternatives for action:•They can try to get it moving again, either by fixing it or getting it past the DIFFICULTY.•They can remain in the nonfunctional RELATIONSHIP, and give up onACHIEVING THEIR LIFE GOALS.•They can abandon the RELATIONSHIP.The alternative of remaining in the nonfunctional RELATIONSHIP takes the least effort, but does not satisfy the desire to ACHIEVE LIFE GOALS. This is an example of an inference pattern that is mapped from one domain to another. It is via such mappings that we apply knowledge about travel to love relationships.Metaphors are not mere wordsWhat constitutes the LOVE-AS-JOURNEY metaphor is not any particular word or expression. It is the ontological mapping across conceptual domains, from the source domain of journeys to the target domain of love. The metaphor is not just a matter of language, but of thought and reason. The language is secondary. The mapping is primary, in that it sanctions the use of source domain language and inference patterns for target domain concepts. The mapping is conventional, that is, it is a fixed part of our conceptual system, one of our conventional ways of conceptualizing love relationships. This view of metaphor is thoroughly at odds with the view that metaphors are just linguistic expressions. If metaphors were merely linguistic expressions, we would expect different linguistic expressions to be different metaphors. Thus, "We’ve hit a dead-end street" would constitute one metaphor. "We can’t turn back now" would constitute another, entirely different metaphor. "Their marriage is on the rocks" would involve still a different metaphor. And so on for dozens of examples. Yet we don’t seem to have dozens of different metaphors here. We have one metaphor, in which love is conceptualized as a journey. The mapping tells us precisely how love is being conceptualized as a journey. And this unified way of conceptualizing love metaphorically is realized in many different linguistic expressions. It should be noted that contemporary metaphor theorists commonly use the term metaphor to refer to the conceptual mapping, and the term metaphorical expression to refer to an individual linguistic expression (like dead-end street) that is sanctioned by a mapping. We have adopted this terminology for the following reason: Metaphor, as a phenomenon, involves both conceptual mappings and individual linguistic expressions. It is important to keep them distinct. Since it is the mappings that are primary and that state the generalizations that are our principal concern, we have reserved the term metaphor for the mappings, rather than for the linguistic expressions. In the literature of the field, small capitals like LOVE IS A JOURNEY are used as mnemonics to name mappings. Thus, when we refer to the LOVE IS A JOURNEY metaphor, we are refering to the set of correspondences discussed above. The English sentence Love is a journey, on the other hand, is a metaphorical expression that is understood via that set of correspondences.GeneralizationsThe LOVE IS A JOURNEY metaphor is a conceptual mapping that characterizes a generalization of two kinds:•Polysemy generalization: A generalization over related senses of linguistic expressions, e.g., dead-end street, crossroads, stuck, spinning one’s wheels, not going anywhere, and so on.•Inferential generalization: A generalization over inferences across different conceptual domains.That is, the existence of the mapping provides a general answer to two questions: -Why are words for travel used to describe love relationships? -Why are inference patterns used to reason about travel also used to reason about love relationships. Correspondingly, from the perspective of the linguistic analyst, the existence of such cross-domain pairings of words and of inference patterns provides evidence for the existence of such mappings. Novel extensions of conventional metaphorsThe fact that the LOVE IS A JOURNEY mapping is a fixed part of our conceptual system explains why new and imaginative uses of the mapping can be understood instantly, given the ontological correspondences and other knowledge about journeys. Take the song lyric, We’re driving in the fast lane on the freeway of love. The traveling knowledge called upon is this: When you drive in the fast lane, you go a long way in a short time and it can be exciting and dangerous. The general metaphorical mapping maps this knowledge about driving into knowledge about love relationships. The danger may be to the vehicle (the relationship may not last) or the passengers (the lovers may be hurt, emotionally). The excitement of the love-journey is sexual. Our understanding of the song lyric is a consequence of the pre-existing metaphorical correspondences of the LOVE-AS-JOURNEY metaphor. The song lyric is instantly comprehensible to speakers of English because those metaphorical correspondences are already part of our conceptual system. The LOVE-AS-JOURNEY metaphor and Reddy’s Conduit Metaphor were the two examples that first convinced me that metaphor was not a figure of speech, but a mode of thought, defined by a systematic mapping from a source to a target domain. What convinced me were the three characteristics of metaphor that I have just discussed: The systematicity in the linguistic correspondences. The use of metaphor to govern reasoning and behavior based on that reasoning. The possibility for understanding novel extensions in terms of the conventional correspondences.MotivationEach conventional metaphor, that is, each mapping, is a fixed pattern of conceptual correspondences across conceptual domains. As such, each mapping defines an open-ended class of potential correspondences across inference patterns. When activated, a mapping may apply to a novel source domain knowledge structure and characterize a corresponding target domain knowledge structure. Mappings should not be thought of as processes, or as algorithms that mechanically take source domain inputs and produce target domain outputs. Each mapping should be seen instead as a fixed pattern of onotological correspondences across domains that may, or may not, be applied to a source domain knowledge structure or a source domain lexical item. Thus, lexical items that are conventional in the source domain are not always conventional in the target domain. Instead, each source domain lexical item may or may not make use of the static mapping pattern. If it does, it has an extended lexicalized sense in the target domain, where that sense is characterized by the mapping. If not, the source domain lexical item will not have a conventional sense in the target domain, but may still be actively mapped in the case of novel metaphor. Thus, the words freeway and fast lane are not conventionally used of love, but the knowledge structures associated with them are mapped by the LOVE IS A JOURNEY metaphor in the case of We’re driving in the fast lane on the freeway of love. Imageable IdiomsMany of the metaphorical expressions discussed in the literature on conventional metaphor are idioms. On classical views, idioms have arbitrary meanings. But withincognitive linguistics, the possibility exists that they are not arbitrary, but rather motivated. That is, they do arise automatically by productive rules, but they fit one or more patterns present in the conceptual system. Let us look a little more closely at idioms. An idiom like spinning one’s wheels comes with a conventional mental image, that of the wheels of a car stuck in some substance-either in mud, sand, snow, or on ice, so that the car cannot move when the motor is engaged and the wheels turn. Part of our knowledge about that image is that a lot of energy is being used up (in spinning the wheels) without any progress being made, that the situation will not readily change of its own accord, that it will take a lot of effort on the part of the occupants to get the vehicle moving again --and that may not even be possible. The love-as-journey metaphor applies to this knowledge about the image. It maps this knowledge onto knowledge about love relationships: A lot of energy is being spent without any progress toward fulfilling common goals, the situation will not change of its own accord, it will take a lot of effort on the part of the lovers to make more progress, and so on. In short, when idioms that have associated conventional images, it is common for an independently-motivated conceptual metaphor to map that knowledge from the source to the target domain. For a survey of experiments verifying the existence of such images and such mappings, see Gibbs 1990 and this volume. Mappings are at the superordinate levelIn the LOVE IS A JOURNEY mapping, a love relationship corresponds to a vehicle. A vehicle is a superordinate category that includes such basic-level categories as car, train, boat, and plane. Indeed, the examples of vehicles are typically drawn from this range of basic level categories: car ( long bumpy road, spinning our wheels), train (off the track), boat (on the rocks, foundering), plane (just taking off, bailing out). This is not an accident: in general, we have found that mappings are at the superordinate rather than the basic level. Thus, we do not find fully general submappings like A LOVE RELATIONSHIP IS A CAR; when we find a love relationship conceptualized as a car, we also tend to find it conceptualized as a boat, a train, a plane, etc. It is the superordinate category VEHICLE not the basic level category CAR that is in the general mapping. It should be no surprise that the generalization is at the superordinate level, while the special cases are at the basic level. After all, the basic level is the level of rich mental images and rich knowledge structure. (For a discussion of the properties of basic-level categories, see Lakoff, 1987, pp. 31-50.) A mapping at the superordinate level maximizes the possibilities for mapping rich conceptual structure in the source domain onto the target domain, since it permits many basic-level instances, each of which is information rich. Thus, a prediction is made about conventional mappings: the categories mapped will tend to be at the superordinate rather than basic level. Thus, one tends not to find mappings like A LOVE RELATIONSHIP IS A CAR or A LOVE RELATIONSHIP IS A BOAT. Instead, one tends to find both basic-level cases (e.g., both cars and boats), which indicates that the generalization is one level higher, at the superordinate level of the vehicle. In the hundreds of cases of conventional mappings studied so far, this prediction has been borne out: it is superordinate categories that are used in mappings.Basic Semantic Concepts That Are MetaphoricalMost people are not too surprised to discover that emotional concepts like love and anger are understood metaphorically. What is more interesting, and I think more exciting, is the realization that many of the most basic concepts in our conceptual systems are alsocomprehended normally via metaphor-concepts like time, quantity, state, change, action, cause, purpose, means, modality and even the concept of a category. These are concepts that enter normally into the grammars of languages, and if they are indeed metaphorical in nature, then metaphor becomes central to grammar. What I would like to suggest is that the same kinds of considerations that lead to our acceptance of the LOVE-AS-JOURNEY metaphor lead inevitably to the conclusion that such basic concepts are often, and perhaps always, understood via metaphor.CategoriesClassical categories are understood metaphorically in terms of bounded regions, or ‘containers.’ Thus, something can be in or out of a category, it can be put into a category or removed from a category, etc. The logic of classical categories is the logic of containers (see figure 1). If X is in container A and container A is in container B, then X is in container B. This is true not by virtue of any logical deduction, but by virtue of the topological properties of containers. Under the CLASSICAL CATEGORIES ARE CONTAINERS metaphor, the logical properties of categories are inherited from the logical properties of containers. One of the principal logical properties of classical categories is that the classical syllogism holds for them. The classical syllogism, Socrates is a man. All men are mortal. Therefore, Socrates is mortal. is of the form: If X is in category A and category A is in category B, then X is in category B. Thus, the logical properties of classical categories can be seen as following from the topological properties of containers plus the metaphorical mapping from containers to categories. As long as the topological properties of containers are preserved by the mapping, this result will be true. In other words, there is a generalization to be stated here. The language of containers applies to classical categories and the logic of containers is true of classical categories. A single metaphorical mapping ought to characterize both the linguistic and logical generalizations at once. This can be done provided that the topological properties of containers are preserved in the mapping. The joint linguistic-and-inferential relation between containers and classical categories is not an isolated case. Let us take another example.Quantity and Linear ScalesThe concept of quantities involves at least two metaphors. The first is the well-known MORE IS UP, LESS IS DOWN metaphor as shown by a myriad of expressions like Prices rose, Stocks skyrocketed, The market plummeted, and so on. A second is that LINEAR SCALES ARE PATHS. We can see this in expressions like: John is far more intelligent than Bill. John’s intelligence goes way beyond Bill’s. John is way ahead of Bill in intelligence. The metaphor maps the starting point of the path onto the bottom of the scale and maps distance traveled onto quantity in general. What is particularly interesting is that the logic of paths maps onto the logic of linear scales. (See figure 2.) Path inference: If you are going from A to C, and you are now at in intermediate point B, then you have been at all points between A and B and not at any points between B and C. Example: If you are going from San Francisco to N.Y. along route 80, and you are now at Chicago, then you have been to Denver but not to Pittsburgh. Linear scale inference: If you have exactly $50 in your bank account, then you have $40, $30, and so on, but not $60, $70, or any larger amount. The form of these inferences is the same. The path inference is a consequence of the cognitive topology of paths. It will be true of any path image-schema. Again, there is a linguistic-and-inferential generalization to be stated. It would be stated by the metaphor LINEAR SCALES ARE PATHS, provided that metaphors in general preserve the cognitive topology (that is, the image-schematic structure) of the source。

World Literature Studies 世界文学研究, 2023, 11(5), 375-379Published Online October 2023 in Hans. https:///journal/wlshttps:///10.12677/wls.2023.115065科马克·麦卡锡《路》中的梦境叙事王妍扬州大学外国语学院,江苏扬州收稿日期:2023年8月28日;录用日期:2023年10月10日;发布日期:2023年10月19日摘要作为一种独到的文学创作技巧,梦境叙事在美国当代作家科马克·麦卡锡著名的末世题材小说《路》中占据重要地位。

小说中的十三处梦碎片大体可分为怀旧梦、想象梦、变异梦三个类别,梦中出现的“怪物”“蛇”“妻子”等重要意象蕴含深刻的象征意义,不仅揭示了人物内心世界,还开拓了小说叙事格局,亦凸显了小说“末世救赎”之主题。

关键词《路》,梦境叙事,科马克·麦卡锡,意象On the Dream Narrative in CormacMcCarthy’s The RoadYan WangCollege of Foreign Languages, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou JiangsuReceived: Aug. 28th, 2023; accepted: Oct. 10th, 2023; published: Oct. 19th, 2023AbstractAs a unique literary creation skill, dream narrative occupies an important position in the Ameri-can contemporary writer Cormac McCarthy’s apocalyptic novel The Road. The thirteen dreams in the novel can be divided into three categories: nostalgic dreams, imaginary dreams, and mutated dreams. The important images appearing in the dreams including “monsters” “snakes” and “wife”carry profound symbolic meaning, which not only provides insights into characters’ mind, but also opens up the narrative pattern of the novel, and highlights the “apocalyptic redemption” them of the novel.王妍KeywordsThe Road, Dream Narrative, Cormac McCarthy, ImageCopyright © 2023 by author(s) and Hans Publishers Inc.This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0)./licenses/by/4.0/1. 引言《路》是美国作家科马克·麦卡锡著名的末世题材小说,讲述了在一片死寂的末日寒冬,一对父子沿着某条模糊的“长路”执着向南,寻找更为温暖的避难所。

论弗罗斯特《摘苹果之后》中的死亡隐喻发布时间:2022-07-21T08:53:03.876Z 来源:《时代教育》2022年5期作者:刘沛婷[导读] 乔治·莱考夫和马克?约翰逊于《我们赖以生存的隐喻》一书中指出隐喻不仅仅是一种修辞手法,更是一种思维方式刘沛婷湖南师范大学,湖南长沙 410006摘要:乔治·莱考夫和马克?约翰逊于《我们赖以生存的隐喻》一书中指出隐喻不仅仅是一种修辞手法,更是一种思维方式,在人们的日常语言和活动中无所不在。

诗歌是高度隐喻化的体裁,本文就将以弗罗斯特的短诗——《摘苹果之后》为例,通过挖掘诗歌中的结构隐喻、方位隐喻和本体隐喻,深刻剖析弗罗斯特的死亡观建构,为该诗的解读提供新的维度,也有助于丰富该理论的应用范畴。