曼昆经济学原理英文版第11章

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:356.42 KB

- 文档页数:18

曼昆《经济学原理(微观经济学分册)》(第6版)第11章公共物品和公共资源课后习题详解跨考网独家整理最全经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题解析资料库,您可以在这里查阅历年经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题,经济学考研参考书等内容,更有跨考考研历年辅导的经济学学哥学姐的经济学考研经验,从前辈中获得的经验对初学者来说是宝贵的财富,这或许能帮你少走弯路,躲开一些陷阱。

以下内容为跨考网独家整理,如您还需更多考研资料,可选择经济学一对一在线咨询进行咨询。

一、概念题1.排他性(excludability)答:排他性指一个人使用或消费一种产品或服务时可以阻止其他人使用或消费该种产品和服务的特性。

一种产品或服务具有排他性时,一个人使用或消费该产品或服务时可以阻止其他人使用或消费该种产品和服务。

排他性是区分公共物品和私人物品的标准之一。

生产者的排他原则有效时,生产者能够限制那些不为这种物品支付的消费者使用这种商品,消费者的排他性有效时,消费者在消费一种物品时,其他人能够被排除在外。

在排他性原则失效的地方,就会出现没有付出代价,却可以享受物品效用的“免费搭便车”现象。

2.消费中的竞争性(rivalry in consumption)答:消费中的竞争性指一种产品或服务被一个人消费从而减少了其他人消费的特性。

如果某人已经使用了某个商品(如某一火车座位),其他人就不能再同时使用该商品,则这种商品就具有消费中的竞争性。

市场机制只有在具备排他性和竞争性两个特点的私人物品的场合才真正起作用,才有效率。

3.私人物品(private goods)答:私人物品指既有排他性又有竞争性的物品,是供个人单独消费的物品。

私人物品是那种可得数量将随任何人对它的消费或使用的增加而减少的物品,它具有两个特征:第一是竞争性,如果某人已消费了某种商品,则其他人就不能再消费该商品;第二是排他性,对商品支付价格的人才能消费商品,其他人则不能。

4.公共物品(public goods)(西北大学2003研;北京师范大学2007研;华南理工大学2010研)答:公共物品与私人物品相对应,指既无排他性又无竞争性的物品。

曼昆《经济学原理(微观经济学分册)》(第6版)第11章公共物品和公共资源复习笔记跨考网独家整理最全经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题解析资料库,您可以在这里查阅历年经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题,经济学考研参考书等内容,更有跨考考研历年辅导的经济学学哥学姐的经济学考研经验,从前辈中获得的经验对初学者来说是宝贵的财富,这或许能帮你少走弯路,躲开一些陷阱。

以下内容为跨考网独家整理,如您还需更多考研资料,可选择经济学一对一在线咨询进行咨询。

一、不同类型的物品1.相关概念:(1)排他性:一种物品具有的可以阻止一个人使用该物品的特性。

(2)消费者的竞争性:一个人使用一种物品将减少其他人对该物品的使用的特性。

(3)私人物品(private goods):消费中既有排他性又有竞争性的物品。

(4)公共资源:有竞争性但无排他性的物品。

(5)公共物品:既无排他性又无竞争性的物品。

(6)自然垄断:当一种物品在消费中有排他性但没有竞争性时,就是自然垄断的物品。

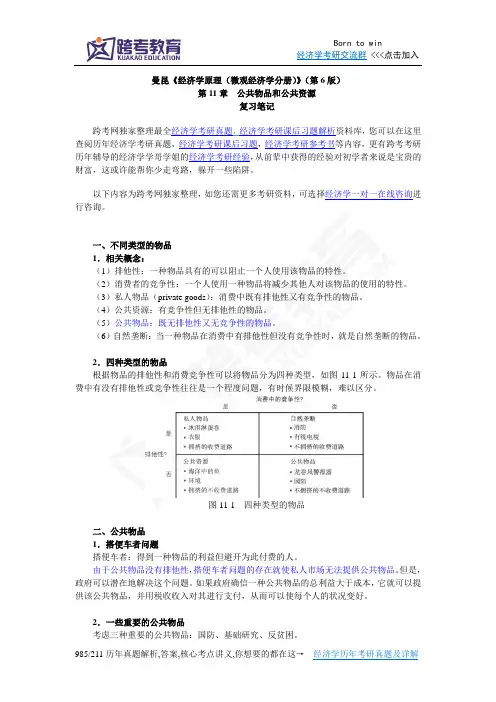

2.四种类型的物品根据物品的排他性和消费竞争性可以将物品分为四种类型,如图11-1所示。

物品在消费中有没有排他性或竞争性往往是一个程度问题,有时候界限模糊,难以区分。

图11-1 四种类型的物品二、公共物品1.搭便车者问题搭便车者:得到一种物品的利益但避开为此付费的人。

由于公共物品没有排他性,搭便车者问题的存在就使私人市场无法提供公共物品。

但是,政府可以潜在地解决这个问题。

如果政府确信一种公共物品的总利益大于成本,它就可以提供该公共物品,并用税收收入对其进行支付,从而可以使每个人的状况变好。

2.一些重要的公共物品考虑三种重要的公共物品:国防、基础研究、反贫困。

(1)国防国防既无排他性,也无竞争性。

国防是政府应该提供的公共物品。

(2)基础研究基础研究可以通过研究创造出知识。

知识可区分为一般性知识与特定知识:①特定技术知识可以申请专利,专利使发明者创造的知识具有了排他性,这将激励企业拿出资金用于新产品开发的研究中,以便获得专利并出售;②一般性知识是公共物品,既无排他性,也无竞争性,企业往往搭一般知识的便车,很少在上面投资。

曼昆经济学原理(双语)带你读经济学原理,每日更新/欢迎来主页查看/翻译经过校对第一章经济学十大原理The word economy comes from the Greek woid oikonomos,which means “one who manages a household." At first, this origin might seem peculiar. But in fact, households and economies have much in common. A household faces many decisions. It must decide wliich household members do which tasks and what each member receives in return: Wlio cooks diimer? Wlio does the laundiy? Who gets the extra dessert at dinner? Who gets to drive the car? In short, a household must allocate its scarce resources (time, dessert, car mileage) among its various members, taking into account each member's abilities, efforts, and desires.经济这个词来源于希腊语,其意为“管理一个家庭的人”。

乍一看,这个起源似乎有点奇特。

但事实上,家庭和经济有着许多共同之处。

一个家庭面临着许多决策。

它必须决定哪些家庭成员去做什么,以及作为回报每个家庭成员能得到什么:谁做晚饭?谁洗衣服?谁在晚餐时多得到一块甜点?谁有权选择看什么电视节目?简言之,家庭必须考虑到每个成员的能力、努力和愿望,以在各个成员中配置稀缺资源(时间,甜点,车辆英里程)。

曼昆《经济学原理(微观经济学分册)》(第6版)第11章公共物品和公共资源课后习题详解一、概念题1.排他性(excludability)答:排他性指一个人使用或消费一种产品或服务时可以阻止其他人使用或消费该种产品和服务的特性。

一种产品或服务具有排他性时,一个人使用或消费该产品或服务时可以阻止其他人使用或消费该种产品和服务。

排他性是区分公共物品和私人物品的标准之一。

生产者的排他原则有效时,生产者能够限制那些不为这种物品支付的消费者使用这种商品,消费者的排他性有效时,消费者在消费一种物品时,其他人能够被排除在外。

在排他性原则失效的地方,就会出现没有付出代价,却可以享受物品效用的“免费搭便车”现象。

2.消费中的竞争性(rivalry in consumption)答:消费中的竞争性指一种产品或服务被一个人消费从而减少了其他人消费的特性。

如果某人已经使用了某个商品(如某一火车座位),其他人就不能再同时使用该商品,则这种商品就具有消费中的竞争性。

市场机制只有在具备排他性和竞争性两个特点的私人物品的场合才真正起作用,才有效率。

3.私人物品(private goods)答:私人物品指既有排他性又有竞争性的物品,是供个人单独消费的物品。

私人物品是那种可得数量将随任何人对它的消费或使用的增加而减少的物品,它具有两个特征:第一是竞争性,如果某人已消费了某种商品,则其他人就不能再消费该商品;第二是排他性,对商品支付价格的人才能消费商品,其他人则不能。

4.公共物品(public goods)(西北大学2003研;北京师范大学2007研;华南理工大学2010研)答:公共物品与私人物品相对应,指既无排他性又无竞争性的物品。

一种公共物品可以同时供一个以上的人消费,任何一个人对某种公共物品的消费,都不排斥其他人对这种物品的消费,也不会减少其他人由此而获得的满足。

公共物品具有四个特性:①非排他性。

一种公共物品可以同时供一个以上的人消费,任何人对某种公共物品的消费,都不排斥其他人对这种物品的消费,也不会减少其他人由此而获得的满足。

曼昆经济学原理(双语)带你读《经济学原理》,每日更新,欢迎来主页查看。

翻译部分经本人校对修改,本文仅供学习交流使用,版权归相关权利人所有!第一章经济学十大原理原理八How the Economy as a Whole Works整体经济如何运行We started by discussing how individuals make decisions and then looked at how people interact with one another. All these decisions and interactions together make up “the economy.” The last three principles concern the workings of the economy as a whole.我们从讨论个人如何作出决策开始,然后考察人们如何相互作用。

所有这些决策和相互作用共同组成了“经济”。

后三个原理涉及到整体经济的运行。

Principle 8: A Country’s Standard of Living Depends on Its Ability to Produce Goods and Services原理八:一国的生活水平取决于它生产物品与劳务的能力The differences in living standards around the world are staggering. In 2014, the average American had an income of about $55,000. In thesame year, the average Mexican earned about $17,000, the average Chinese about $13,000, and the average Nigerian only $6,000. Not surprisingly, this large variation in average income is reflected in various measures of quality of life. Citizens of high-income countries have more TV sets, more cars, better nutrition, better healthcare, and a longer life expectancy than citizens of low-income countries.世界各国生活水平的差别是惊人的。

第十一章公共物品和共有资源复习题1.解释一种物品有“排他性”的含义。

解释一种物品有“竞争性”的含义。

比萨饼有排他性吗?有竞争性吗?答:一种物品具有“排他性”是指可以阻止一个人使用一种物品时该物品的特性。

一种物品有竞争性是指一个人使用一种物品减少其他人使用该物品的特性。

比萨饼有排他性,只要不卖给某人比萨饼就可以阻止他使用。

比萨饼也有竞争性,一个人多吃一块比萨饼,会使其他人少享受一块。

2.给公共物品下定义并举出一个例子。

私人市场本身能提供这种物品吗?并解释之。

答:公共物品是既无排他性又无竞争性的物品,私人市场本身不能提供这种物品。

公共物品没有排他性,因此,无法对公共物品的使用者收费,在私人提供这种物品时就存在搭便车的激励,从而使私人提供者无利可图。

3.什么是公共物品的成本一收益分析?为什么它是重要的?进行这种分析困难吗?答:公共物品的成本一收益分析是提供一种公共物品的社会成本和社会收益比较的研究。

只有比较提供一种公共物品的成本与收益,政府才能决定是否值得提供这种公共物品。

公共物品的成本一收益分析是一项艰苦的工作。

因为所有的人都可以免费使用一种公共物品,没有判断这种公共物品价值的价格。

简单地问人们,他们对一种公共物品的评价是多少是不可靠的。

那些受益于该公共物品的人有夸大他们的利益的激励。

那些受害于该公共物品的人有夸大他们成本的激励。

4.给共有资源下定义并举出一个例子。

没有政府干预,人们使用这种物品会太多还是太少?为什么?答:共有资源是有竞争性但无排他性的物品。

没有政府干预,人们使用这种物品会太多。

因为不能向使用共有资源的人收费,而且,一个人对共有资源的使用会减少其他人的使用,所以,共有资源往往被过度使用。

问题与应用1.本书认为公共物品和共有资源都涉及外部性。

A.与公共物品相关的外部性一般是正的还是负的?用例子来回答。

自由市场的公共物品量一般是大于还是小于有效率的数量?答:与公共物品相关的外部性一般是负的。

SOLUTIONS TO TEXT PROBLEMS:Quick Quizzes1. Public goods are goods that are neither excludable nor rival. Examples include national defense,knowledge, and uncongested nontoll roads. Common resources are goods that are rival but not excludable. Examples include fish in the ocean, the environment, and congested nontoll roads. 2. The free-rider problem occurs when people receive the benefits of a good but avoid paying for it.The free-rider problem induces the government to provide public goods because if the government uses tax revenue to provide the good, everyone pays for it and everyone enjoys its benefits. The government should decide whether to provide a public good by comparing the good’s costs to its benefits; if the benefits exceed the costs, society is better off.3. Governments try to limit the use of common resources because one person’s use of the resourcediminishes others’ use of it, so there is a negative externality which leads people to use common resources excessively.Questions for Review1. An excludable good is one that people can be prevented from using. A rival good is one for whichone person's use of it diminishes another person's enjoyment of it. Pizza is both excludable, sincea pizza producer can prevent someone from ea ting it who doesn't pay for it, and rival, since whenone person eats it, no one else can eat it.2. A public good is a good that is neither excludable nor rival. An example is national defense, whichprotects the entire nation. No one can be prevented from enjoying the benefits of it, so it is not excludable, and an additional person who benefits from it does not diminish the value of it to others, so it is not rival. The private market will not supply the good, since no one would pay for itbecause they cannot be excluded from enjoying it if they don't pay for it.3. Cost-benefit analysis is a study that compares the costs and benefits to society of providing a publicgood. It is important because the government needs to know which public goods people value most highly and which have benefits that exceed the costs of supplying them. It is hard to dobecause quantifying the benefits is difficult to do from a questionnaire and because respondents have little incentive to tell the truth.4. A common resource is a good that is rival but not excludable. An example is fish in the ocean. Ifsomeone catches a fish, that leaves fewer fish for everyone else, so it's a rival good. But theocean is so vast, you cannot charge people for the right to fish, or prevent them from fishing, so it is not excludable. Thus, without government intervention, people will use the good too much,since they don't account for the costs they impose on others when they use the good.Problems and Applicat ions1. a. The externalities associated with public goods are positive. Since the benefits from thepublic good received by one person don't reduce the benefits received by anyone else, thesocial value of public goods is substantially greater than the private value. Examplesinclude national defense, knowledge, uncongested non-toll roads, and uncongested parks.Since public goods aren't excludable, the free-market quantity is zero, so it is less than the215efficient quantity.b. The externalities associated with common resources are generally negative. Sincecommon resources are rival but not excludable (so not priced) the use of the commonresources by one person reduces the amount available for others. Since commonresources are not priced, people tend to overuse them their private cost of using theresources is less than the social cost. Examples include fish in the ocean, theenvironment, congested non-toll roads, the Town Commons, and congested parks.2. a. (1) Police protection is a natural monopoly, since it is excludable (the police may ignoresome neighborhoods) and not rival (unless the police force is overworked, they're availablewhenever a crime arises). You could make an argument that police protection is rival, ifthe police are too busy to respond to all crimes, so that one person's use of the policereduces the amount available for others; in that case, police protection is a private good.(2) Snow plowing is most likely a common resource. Once a street is plowed, it isn'texcludable. But it is rival, especially right after a big snowfall, since plowing one streetmeans not plowing another street.(3) Education is a private good (with a positive externality). It is excludable, sincesomeone who doesn't pay can be prevented from taking classes. It is rival, since thepresence of an additional student in a class reduces the benefits to others.(4) Rural roads are public goods. They aren't excludable and they aren't rival sincethey're uncongested.(5) City streets are common resources when congested. They aren't excludable, sinceanyone can drive on them. But they are rival, since congestion means every additionaldriver slows down the progress of other drivers. When they aren't congested, city streetsare public goods, since they're no longer rival.b. The government may provide goods that aren't public goods, such as education, becauseof the externalities associated with them.3. a. Charlie is a free rider.b. The government could solve the problem by sponsoring the show and paying for it with taxrevenue collected from everyone.c. The private market could also solve the problem by making people watch commercials thatare incorporated into the program. The existence of cable TV makes the good excludable,so it would no longer be a public good.4. a. Since knowledge is a public good, the benefits of basic scientific research are available tomany people. The private firm doesn't take this into account when choosing how muchresearch to undertake; it only takes into account what it will earn.b. The United States has tried to give private firms incentives to provide basic research bysubsidizing it through organizations like the National Institute of Health and the NationalScience Foundation.c. If it's basic research that adds to knowledge, it isn't excludable at all, unless people in othercountries can be prevented somehow from sharing that knowledge. So perhaps U.S.firms get a slight advantage because they hear about technological advances first, butknowledge tends to diffuse rapidly.5. When a person litters along a highway, others bear the negative externality, so the private costsare low. Littering in your own yard imposes costs on you, so it has a higher private cost and is thus rare.6. When the system is congested, each additional rider imposes costs on other riders. For example,when all seats are taken, some people must stand. Or if there isn't any room to stand, somepeople must wait for a train that isn't as crowded. Increasing the fare during rush hourinternalizes this externality.7. On privately owned land, the amount of logging is likely to be efficient. Loggers have incentives todo the right amount of logging, since they care that the trees replenish themselves and the forest can be logged in the future. Publicly owned land, however, is a common resource, and is likely to be overlogged, since loggers won't worry about the future value of the land.Since public lands tend to be overlogged, the government can improve things by restricting thequantity of logging to its efficient level. Selling permits to log, or taxing logging, could be used to reach the appropriate quantity by internalizing the externality. Such restrictions are unnecessary on privately owned lands, since there is no externality.8. a. Overfishing is rational for fishermen since they're using a common resource. They don'tbear the costs of reducing the number of fish available to others, so it's rational for them tooverfish. The free-market quantity of fishing exceeds the efficient amount.b. A solution to the problem could come from regulating the amount of fishing, taxing fishingto internalize the externality, or auctioning off fishing permits. But these solutionswouldn't be easy to implement, since many nations have access to ocea ns, so internationalcooperation would be necessary, and enforcement would be difficult, because the sea is solarge that it is hard to police.c. By giving property rights to countries, the scope of the problem is reduced, since eachcountry has a greater incentive to find a solution. Each country can impose a tax or issuepermits, and monitor a smaller area for compliance.d. Since government agencies (like the Coast Guard in the United States) protect fishermenand rescue them when they need help, the fishermen aren't bearing the full costs of theirfishing. Thus they fish more than they should.e. The statement, "Only when fishermen believe they are assured a long-term and exclusiveright to a fishery are they likely to manage it in the same far-sighted way as good farmersmanage they land," is sensible. If fishermen owned the fishery, they would be sure not tooverfish, because they would bear the costs of overfishing. This is a case in whichproperty rights help prevent the overuse of a common resource.f. Alternatives include regulating the amount of fishing, taxing fishermen, auctioning offfishing permits, or taxing fish sold in stores. All would tend to reduce the amount offishing from the free-market amount toward the efficient amount.9. The private market provides information about the quality or function of goods and services inseveral different ways. First, producers advertise, providing people information about the product and its quality. Second, private firms provide information to consumers with independent reportson quality; an example is the magazine Consumer Reports. The government plays a role as well, by regulating advertising, thus preventing firms from exaggerating claims about their products,regulating certain goods like gasoline and food to be sure they are measured properly and provided without disease, and not allowing dangerous products on the market.10. To be a public good, a good must be neither rival nor excludable. When the Internet isn’tcongested, it is n ot rival, since one person’s use of it does not affect anyone else. However, at times traffic on the Internet is so great that everything slows down at such times, the Internet is rival. Is the Internet excludable? Since anyone operating a Web site can charge a customer for visiting the site by requiring a password, the Internet is excludable. Thus the Internet is notstrictly a public good. Since the Internet is usually not rival, it is more like a natural monopolythan a public good. However, since most people’s Web sites contain information and exclude no one, the majority of the Internet is a public good (when it is not congested).11. Recognizing that there are opportunity costs that are relevant for cost-benefit analysis is the key toanswering this question. A richer community can afford to place a higher value on life and safety.So the richer community is willing to pay more for a traffic light, and that should be considered in cost-benefit analysis.。

Chapter 11 Public Goods And Common Resources 公共物品和共有资源·本章问题:公共物品和共有资源的定义为什么私人市场不能生产公共物品我们经济中的一些重要的公共物品为什么公共物品的成本—收益分析既是必要的又是困难的为什么人们往往会过多的使用共有资源我们经济中一些重要的共有资源§1. 不同类型的物品The Different Kinds of Goods一.根据两个特点来分类1.排他性Excludability:可以阻止其他人享用该物品the property of a good whereby a person can be prevented from using it2.竞争性Rivalry:某人对该物品的使用减少其他人对该物品的享受。

the property of a good whereby one person’s use diminishes other people’s use 二.四类物品Four Types of Goods1.私人物品Private Goods:既有排他性,又有竞争性both excludable and rival.2.公共物品Public Goods:既无排他性,又无竞争性neither excludable nor rival3.共有资源Common Resources:有竞争性,无排他性rival but not excludable4.自然垄断Natural Monopolies:有排他性,无竞争性excludable but not rival§2. 公共物品Public Goods一.搭便车问题The Free-Rider Problem1.搭便车者a free-rider:从一种物品中获益,但却避免了为此支付的人a person who receives the benefit of a good but avoids paying for it2.结论:由于公共物品没有排他性,搭便车者问题就阻碍了私人市场提供公共物品。

Examine why people tend to use common r esour ces too much Consider some of the impor tant common r esour ces in our economyConsider some of the impor tant public goods in our economy Lear n t he def ini ng characteristics of public goods and common r esour ces Examine why private markets fail to pr ovide public goods See why the cost-benefit analysis of public goods is both necessar y and dif ficult An old song lyric maintains that “the best things in life are free.” A moment’s thought reveals a long list of goods that the songwriter could have had in mind. Na-ture provides some of them, such as rivers, mountains, beaches, lakes, and oceans.The government provides others, such as playgrounds, parks, and parades. In each case, people do not pay a fee when they choose to enjoy the benefit of the good.Free goods provide a special challenge for economic analysis. Most goods in our economy are allocated in markets, where buyers pay for what they receive and sellers are paid for what they provide. For these goods, prices are the signals that guide the decisions of buyers and sellers. When goods are available free of charge,however, the market forces that normally allocate resources in our economy are absent.In this chapter we examine the problems that arise for goods without market prices. Our analysis will shed light on one of the Ten Principles of EconomicsP U B L I C G O O D S A N DC O M M O N R E S O U R C ES225226PA R T FOU R TH E ECONOMICS OF THE P UBLIC SECTORin Chapter 1: Governments can sometimes improve market outcomes. When a good does not have a price attached to it, private markets cannot ensure that the good is produced and consumed in the proper amounts. In such cases, government policy can potentially remedy the market failure and raise economic well-being.How well do markets work in providing the goods that people want? The answer to this question depends on the good being considered. As we discussed in Chapter 7, we can rely on the market to provide the efficient number of ice-cream cones: The price of ice-cream cones adjusts to balance supply and demand, and this equilib-rium maximizes the sum of producer and consumer surplus. Yet, as we discussed in Chapter 10, we cannot rely on the market to prevent aluminum manufacturers from polluting the air we breathe: Buyers and sellers in a market typically do not take ac-count of the external effects of their decisions. Thus, markets work well when the good is ice cream, but they work badly when the good is clean air.In thinking about the various goods in the economy, it is useful to group them according to two characteristics:N Is the good excludable?Can people be prevented from using the good?N Is the good rival?Does one person’s use of the good diminish another person’s enjoyment of it?Using these two characteristics, Figure 11-1 divides goods into four categories:1.Private goods are both excludable and rival. Consider an ice-cream cone, for example. An ice-cream cone is excludable because it is possible to prevent someone from eating an ice-cream cone—you just don’t give it to him. An ice-cream cone is rival because if one person eats an ice-cream cone, another person cannot eat the same cone. Most goods in the economy are private goods like ice-cream cones. When we analyzed supply and demand in Chapters 4, 5, and 6 and the efficiency of markets in Chapters 7, 8, and 9, we implicitly assumed that goods were both excludable and rival.2.Public goods are neither excludable nor rival. That is, people cannot be prevented from using a public good, and one person’s enjoyment of a public good does not reduce another person’s enjoyment of it. For example, national defense is a public good. Once the country is defended from foreign aggressors, it is impossible to prevent any single person from enjoying the benefit of this defense. Moreover, when one person enjoys the benefit of national defense, he does not reduce the benefit to anyone mon resources are rival but not excludable. For example, fish in the ocean are a rival good: When one person catches fish, there are fewer fish for the next person to catch. Yet these fish are not an excludable good because itis difficult to charge fishermen for the fish that they catch.4.When a good is excludable but not rival, it is an example of a naturalmonopoly.For instance, consider fire protection in a small town. It is easy toexcluda b i l i t ythe property of a good whereby aperson can be prevented fromusing itrivalr ythe property of a good whereby oneperson’s use diminishes otherpeople’s usepr iv at e g o o d sgoods that are both excludableand rivalpubli c g o o d sgoods that are neither excludablenor rivalcom m o n r e so ur c e sgoods that are rival but notexcludableC H A P T E R 11P U B L I C G O OD S A N D C O M M O N RE S O U R C E S 227exclude people from enjoying this good: The fire department can just let their house burn down. Yet fire protection is not rival. Firefighters spend much of their time waiting for a fire, so protecting an extra house is unlikely to reduce the protection available to others. In other words, once a town has paid for the fire department, the additional cost of protecting one more house issmall. In Chapter 15 we give a more complete definition of naturalmonopolies and study them in some detail.In this chapter we examine goods that are not excludable and, therefore, are available to everyone free of charge: public goods and common resources. As we will see, this topic is closely related to the study of externalities. For both public goods and common resources, externalities arise because something of value has no price attached to it. If one person were to provide a public good, such as na-tional defense, other people would be better off, and yet they could not be charged for this benefit. Similarly, when one person uses a common resource, such as the fish in the ocean, other people are worse off, and yet they are not compensated for this loss. Because of these external effects, private decisions about consumption and production can lead to an inefficient allocation of resources, and government intervention can potentially raise economic well-being.QUICK QUIZ:Define public goods and common resources,and give anexample of each.To understand how public goods differ from other goods and what problems they present for society, let’s consider an example: a fireworks display. This good is not excludable because it is impossible to prevent someone from seeing fireworks, and it is not rival because one person’s enjoyment of fireworks does not reduce anyone else’s enjoyment of them.228PA R T FOU R TH E ECONOMICS OF THE P UBLIC SECTORTH E FR EE -RI D ER P ROB L EM The citizens of Smalltown, U.S.A., like seeing fireworks on the Fourth of July. Each of the town’s 500 residents places a $10 value on the experience. The cost of putting on a fireworks display is $1,000. Because the $5,000 of benefits exceed the $1,000 of costs, it is efficient for Smalltown residents to see fireworks on the Fourth of July.Would the private market produce the efficient outcome? Probably not. Imag-ine that Ellen, a Smalltown entrepreneur, decided to put on a fireworks display.Ellen would surely have trouble selling tickets to the event because her potential customers would quickly figure out that they could see the fireworks even without a ticket. Fireworks are not excludable, so people have an incentive to be free riders.A free rider is a person who receives the benefit of a good but avoids paying for it.One way to view this market failure is that it arises because of an externality.If Ellen did put on the fireworks display, she would confer an external benefit onthose who saw the display without paying for it. When deciding whether to put on the display, Ellen ignores these external benefits. Even though a fireworks dis-play is socially desirable, it is not privately profitable. As a result, Ellen makes the socially inefficient decision not to put on the display.Although the private market fails to supply the fireworks display demanded by Smalltown residents, the solution to Smalltown’s problem is obvious: The local government can sponsor a Fourth of July celebration. The town council can raise everyone’s taxes by $2 and use the revenue to hire Ellen to produce the fireworks.Everyone in Smalltown is better off by $8—the $10 in value from the fireworks mi-nus the $2 tax bill. Ellen can help Smalltown reach the efficient outcome as a pub-lic employee even though she could not do so as a private entrepreneur.The story of Smalltown is simplified, but it is also realistic. In fact, many local governments in the United States do pay for fireworks on the Fourth of July. More-over, the story shows a general lesson about public goods: Because public goods are not excludable, the free-rider problem prevents the private market from sup-plying them. The government, however, can potentially remedy the problem. If the government decides that the total benefits exceed the costs, it can provide the public good and pay for it with tax revenue, making everyone better off.SOME IMPOR TANT PUBLIC GOODSThere are many examples of public goods. Here we consider three of the most important.N at i onal Def ens e The defense of the country from foreign aggressors is a classic example of a public good. It is also one of the most expensive. In 1999 the U.S. federal government spent a total of $277 billion on national defense, or about $1,018 per person. People disagree about whether this amount is too small or too large, but almost no one doubts that some government spending for national de-fense is necessary. Even economists who advocate small government agree that the national defense is a public good the government should provide.B a s i c R e s e a r c h The creation of knowledge is a public good. If a mathe-matician proves a new theorem, the theorem enters the general pool of knowledgefr ee ridera person who receives the benefit of agood but avoids paying for itC H A P T E R11P U B L I C G O OD S A N D C O M M O N RE S O U R C E S229“I like the concept if we can do it with no new taxes.”that anyone can use without charge. Because knowledge is a public good, profit-seeking firms tend to free ride on the knowledge created by others and, as a result,devote too few resources to the creation of knowledge.In evaluating the appropriate policy toward knowledge creation, it is impor-tant to distinguish general knowledge from specific, technological knowledge.Specific, technological knowledge, such as the invention of a better battery, can bepatented. The inventor thus obtains much of the benefit of his invention, althoughcertainly not all of it. By contrast, a mathematician cannot patent a theorem; suchgeneral knowledge is freely available to everyone. In other words, the patent sys-tem makes specific, technological knowledge excludable, whereas general knowl-edge is not excludable.The government tries to provide the public good of general knowledge in var-ious ways. Government agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health and theNational Science Foundation, subsidize basic research in medicine, mathematics,physics, chemistry, biology, and even economics. Some people justify governmentfunding of the space program on the grounds that it adds to society’s pool ofknowledge. Certainly, many private goods, including bullet-proof vests and the in-stant drink Tang, use materials that were first developed by scientists and engi-neers trying to land a man on the moon. Determining the appropriate level ofgovernmental support for these endeavors is difficult because the benefits are hardto measure. Moreover, the members of Congress who appropriate funds for re-search usually have little expertise in science and, therefore, are not in the best po-sition to judge what lines of research will produce the largest benefits.F i g h t i n g P o v e r t y Many government programs are aimed at helping thepoor. The welfare system (officially called Temporary Assistance for Needy Fami-lies) provides a small income for some poor families. Similarly, the Food Stampprogram subsidizes the purchase of food for those with low incomes, and variousgovernment housing programs make shelter more affordable. These antipovertyprograms are financed by taxes on families that are financially more successful.230PA R T FOU R TH E ECONOMICS OF THE P UBLIC SECTORC ASE ST UD Y ARE LIGHTHOUSES PUBLIC GOODS?Some goods can switch between being public goods and being private goods depending on the circumstances. For example, a fireworks display is a public good if performed in a town with many residents. Yet if performed at a private amusement park, such as Walt Disney World, a fireworks display is more like a private good because visitors to the park pay for admission.Another example is a lighthouse. Economists have long used lighthouses as examples of a public good. Lighthouses are used to mark specific locations so that passing ships can avoid treacherous waters. The benefit that the lighthouse provides to the ship captain is neither excludable nor rival, so each captain has an incentive to free ride by using the lighthouse to navigate without paying for the service. Because of this free-rider problem, private markets usually fail to provide the lighthouses that ship captains need. As a result, most lighthouses today are operated by the government.Economists disagree among themselves about what role the government should play in fighting poverty. Although we will discuss this debate more fully in Chapter 20, here we note one important argument: Advocates of antipoverty pro-grams claim that fighting poverty is a public good.Suppose that everyone prefers to live in a society without poverty. Even if this preference is strong and widespread, fighting poverty is not a “good” that the pri-vate market can provide. No single individual can eliminate poverty because the problem is so large. Moreover, private charity is hard pressed to solve the problem:People who do not donate to charity can free ride on the generosity of others. In this case, taxing the wealthy to raise the living standards of the poor can make everyone better off. The poor are better off because they now enjoy a higher stan-dard of living, and those paying the taxes are better off because they enjoy living in a society with less poverty.U SE OF THE LIGHTHOUSE IS FREE TO THE BOAT OWNER . D OES THIS MAKE THE LIGHTHOUSE A PUBLIC GOOD?C H A P T E R11P U B L I C G O OD S A N D C O M M O N RE S O U R C E S231In some cases, however, lighthouses may be closer to private goods. On thecoast of England in the nineteenth century, some lighthouses were privatelyowned and operated. The owner of the local lighthouse did not try to chargeship captains for the service but did charge the owner of the nearby port. If theport owner did not pay, the lighthouse owner turned off the light, and shipsavoided that port.In deciding whether something is a public good, one must determine thenumber of beneficiaries and whether these beneficiaries can be excluded fromenjoying the good. A free-rider problem arises when the number of beneficiariesis large and exclusion of any one of them is impossible. If a lighthouse benefitsmany ship captains, it is a public good. Yet if it primarily benefits a single portowner, it is more like a private good.THE DIFFICULT JOB OF COST-BENEFIT ANALYSISSo far we have seen that the government provides public goods because the pri-vate market on its own will not produce an efficient quantity. Yet deciding that thegovernment must play a role is only the first step. The government must then de-termine what kinds of public goods to provide and in what quantities.Suppose that the government is considering a public project, such as buildinga new highway. To judge whether to build the highway, it must compare the totalbenefits of all those who would use it to the costs of building and maintaining it.To make this decision, the government might hire a team of economists and engi-neers to conduct a study, called a cost-benefit analysis,the goal of which is to es-timate the total costs and benefits of the project to society as a whole.Cost-benefit analysts have a tough job. Because the highway will be available to everyone free of charge, there is no price with which to judge the value of the highway. Simply asking people how much they would value the highway is not reliable. First, quantifying benefits is difficult using the results from a question-naire. Second, respondents have little incentive to tell the truth. Those who would use the highway have an incentive to exaggerate the benefit they receive to get the highway built. Those who would be harmed by the highway have an incentive to exaggerate the costs to them to prevent the highway from being built.The efficient provision of public goods is, therefore, intrinsically more difficult than the efficient provision of private goods. Private goods are provided in the market. Buyers of a private good reveal the value they place on it by the prices they are willing to pay. Sellers reveal their costs by the prices they are willing to accept. By contrast, cost-benefit analysts do not observe any price signals when evaluating whether the government should provide a public good. Their findings on the costs and benefits of public projects are, therefore, rough approximations at best.cost-benefit analysisa study that compares the costs and benefits to society of providing a public goodCASE STUDY HOW MUCH IS A LIFE WORTH?Imagine that you have been elected to serve as a member of your local town council. The town engineer comes to you with a proposal: The town can spend $10,000 to build and operate a traffic light at a town intersection that now has only a stop sign. The benefit of the traffic light is increased safety. The engineer232PA R T FOU R TH E ECONOMICS OF THE P UBLIC SECTORestimates, based on data from similar intersections, that the traffic light wouldreduce the risk of a fatal traffic accident over the lifetime of the traffic light from1.6 to 1.1 percent. Should you spend the money for the new light?To answer this question, you turn to cost-benefit analysis. But you quicklyrun into an obstacle: The costs and benefits must be measured in the same unitsif you are to compare them meaningfully. The cost is measured in dollars, butthe benefit—the possibility of saving a person’s life—is not directly monetary.To make your decision, you have to put a dollar value on a human life.At first, you may be tempted to conclude that a human life is priceless. Af-ter all, there is probably no amount of money that you could be paid to volun-tarily give up your life or that of a loved one. This suggests that a human lifehas an infinite dollar value.For the purposes of cost-benefit analysis, however, this answer leads tononsensical results. If we truly placed an infinite value on human life, weshould be placing traffic lights on every street corner. Similarly, we should all bedriving large cars with all the latest safety features, instead of smaller ones withfewer safety features. Yet traffic lights are not at every corner, and people some-times choose to buy small cars without side-impact air bags or antilock brakes.In both our public and private decisions, we are at times willing to risk our livesto save some money.Once we have accepted the idea that a person’s life does have an implicitdollar value, how can we determine what that value is? One approach, some-times used by courts to award damages in wrongful-death suits, is to look at thetotal amount of money a person would have earned if he or she had lived.Economists are often critical of this approach. It has the bizarre implication thatthe life of a retired or disabled person has no value.A better way to value human life is to look at the risks that people are vol-untarily willing to take and how much they must be paid for taking them. Mor-tality risk varies across jobs, for example. Construction workers in high-risebuildings face greater risk of death on the job than office workers do. By com-paring wages in risky and less risky occupations, controlling for education, ex-perience, and other determinants of wages, economists can get some senseabout what value people put on their own lives. Studies using this approachconclude that the value of a human life is about $10 million.EVERYONE WOULDLIKE TO AVOID THERISK OF THIS, BUTATWHATCOSTC H A P T E R 11P U B L I C G O OD S A N D C O M M O N RE S O U R C E S 233We can now return to our original example and respond to the town engi-neer. The traffic light reduces the risk of fatality by 0.5 percent. Thus, the ex-pected benefit from having the traffic light is 0.005 ϫ$10 million, or $50,000.This estimate of the benefit well exceeds the cost of $10,000, so you should ap-prove the project.I N T H E N E W SExistence ValueQUICK QUIZ:What is the free-rider problem?N Why does the free-rider problem induce the government to provide public goods?N How should the government decide whether to provide a public good?Common resources, like public goods, are not excludable: They are available free of charge to anyone who wants to use them. Common resources are, however, rival:234PA R T FOU R TH E ECONOMICS OF THE P UBLIC SECTOROne person’s use of the common resource reduces other people’s enjoyment of it.Thus, common resources give rise to a new problem. Once the good is provided,policymakers need to be concerned about how much it is used. This problem is best understood from the classic parable called the Tragedy of the Commons.THE TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONSConsider life in a small medieval town. Of the many economic activities that take place in the town, one of the most important is raising sheep. Many of the town’s families own flocks of sheep and support themselves by selling the sheep’s wool,which is used to make clothing.As our story begins, the sheep spend much of their time grazing on the land surrounding the town, called the Town Common. No family owns the land. In-stead, the town residents own the land collectively, and all the residents are al-lowed to graze their sheep on it. Collective ownership works well because land is plentiful. As long as everyone can get all the good grazing land they want, the Town Common is not a rival good, and allowing residents’ sheep to graze for free causes no problems. Everyone in town is happy.As the years pass, the population of the town grows, and so does the number of sheep grazing on the Town Common. With a growing number of sheep and a fixed amount of land, the land starts to lose its ability to replenish itself. Eventu-ally, the land is grazed so heavily that it becomes barren. With no grass left on the Town Common, raising sheep is impossible, and the town’s once prosperous wool industry disappears. Many families lose their source of livelihood.What causes the tragedy? Why do the shepherds allow the sheep population to grow so large that it destroys the Town Common? The reason is that social and private incentives differ. Avoiding the destruction of the grazing land depends on the collective action of the shepherds. If the shepherds acted together, they could reduce the sheep population to a size that the Town Common can support. Yet no single family has an incentive to reduce the size of its own flock because each flock represents only a small part of the problem.In essence, the Tragedy of the Commons arises because of an externality. When one family’s flock grazes on the common land, it reduces the quality of the land available for other families. Because people neglect this negative externality when deciding how many sheep to own, the result is an excessive number of sheep.If the tragedy had been foreseen, the town could have solved the problem in various ways. It could have regulated the number of sheep in each family’s flock, internalized the externality by taxing sheep, or auctioned off a limited num-ber of sheep-grazing permits. That is, the medieval town could have dealt with the problem of overgrazing in the way that modern society deals with the problem of pollution.In the case of land, however, there is a simpler solution. The town can divide up the land among town families. Each family can enclose its parcel of land with a fence and then protect it from excessive grazing. In this way, the land becomes a private good rather than a common resource. This outcome in fact occurred dur-ing the enclosure movement in England in the seventeenth century.The Tragedy of the Commons is a story with a general lesson: When one per-son uses a common resource, he diminishes other people’s enjoyment of it. Be-cause of this negative externality, common resources tend to be used excessively.Tra g edy of t he C o m m o nsa parable that illustrates whycommon resources get used morethan is desirable from the standpointof society as a wholeThe government can solve the problem by reducing use of the common resource through regulation or taxes. Alternatively, the government can sometimes turn the common resource into a private good.This lesson has been known for thousands of years. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle pointed out the problem with common resources: “What is common to many is taken least care of, for all men have greater regard for what is their own than for what they possess in common with others.”SOME IMPOR TANT COMMON RESOURCESThere are many examples of common resources. In almost all cases, the same prob-lem arises as in the Tragedy of the Commons: Private decisionmakers use the com-mon resource too much. Governments often regulate behavior or impose fees to mitigate the problem of overuse.Clean Air and Water As we discussed in Chapter 10, markets do not ad-equately protect the environment. Pollution is a negative externality that can be remedied with regulations or with Pigovian taxes on polluting activities. One can view this market failure as an example of a common-resource problem. Clean air and clean water are common resources like open grazing land, and excessive pol-lution is like excessive grazing. Environmental degradation is a modern Tragedy of the Commons.O i l P o o l s Consider an underground pool of oil so large that it lies under many properties with different owners. Any of the owners can drill and extract the oil, but when one owner extracts oil, less is available for the others. The oil is a common resource.Just as the number of sheep grazing on the Town Common was inefficiently large, the number of wells drawing from the oil pool will be inefficiently large. Be-cause each owner who drills a well imposes a negative externality on the other owners, the benefit to society of drilling a well is less than the benefit to the owner who drills it. That is, drilling a well can be privately profitable even when it is so-cially undesirable. If owners of the properties decide individually how many oil wells to drill, they will drill too many.To ensure that the oil is extracted at lowest cost, some type of joint action among the owners is necessary to solve the common-resource problem. The Coase theorem, which we discussed in Chapter 10, suggests that a private solution might be possible. The owners could reach an agreement among themselves about how to extract the oil and divide the profits. In essence, the owners would then act as if they were in a single business.When there are many owners, however, a private solution is more difficult. In this case, government regulation could ensure that the oil is extracted efficiently. Congested Roads Roads can be either public goods or common resources. If a road is not congested, then one person’s use does not affect anyone else. In this case, use is not rival, and the road is a public good. Yet if a road is congested, then use of that road yields a negative externality. When one person drives on the road, it becomes more crowded, and other people must drive more slowly. In this case, the road is a common resource.。