regulation of motivation evaluating an emphasized aspect of self regulated learning

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:98.63 KB

- 文档页数:19

Dimensions of Motivation in Language LearningJeff TennantWEFLA 2004Universidad de Holguín“Oscar Lucero Moya”Course Overview IDefining motivationMotivation as an individual difference variable in second language acquisition (SLA)Some theories of motivation in psychologyCourse Overview IIRobert Gardner’s socio-educational modelDebates on the expansion of the modelEmpirical research studiesApproaches to motivating our studentsWhat is motivation?Brainstorming activity:What does the word “motivation” mean to you?Describe a situation in which you feel very motivated.Describe a situation in which you do not feel motivated.Dörnyei’s “10 Commandments” ISet a personal example with your own behavior.Create a pleasant, relaxed atmosphere in the classroom.Present the tasks properly.Develop a good relationship with the learners.Increase the learners’ linguistic self-confidence.Dörnyei’s “10 Commandments” IIMake the language classes interestingPromote learner autonomyPersonalise the learning processIncrease learners’ goal-orientednessFamiliarize learners with the target language cultureWHICH OF THESE ARE MOST IMPORTANT TO YOU AND WHY?Defining MotivationVast and complex concept referring to what makes people do what they doNot an easy concept to defineWays of defining it have evolved along with theories of human behavior and mindDefinition from Madsen (1959):“By motivation, psychologists mean that which gives impetus to behavior byarousing, sustaining, and directing it toward the attainment of goals.”Earlier theories of motivation IDrive theory (Hull, 1952):physiological needs which create drives; people are motivated to satisfythose drivesReinforcement theory (Skinner, 1953):behaviorist psychology: stimulus-response, behavior controlled byreinforcementsLocke & Latham (1994: 13): “based on the premise that human action could be understood without reference to consciousness. The premise iswrong…”Earlier theories of motivation IIHumanistic psychology (Maslow): satisfaction of basic needs:PhysiologicalSafetyLoveEsteemself-actualizationCurrent dominant paradigmsCognitive revolution:Chomsky’s review of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior contributed to a declineof behaviorist theories and the development of cognitive theories Cognitive and social theories:People viewed as autonomous, thinking beings with minds, who are opento influences from their environment and social context, but are not fullydetermined by those influences.Language Learning MotivationThe most influential approach to motivation in language learning: R.C. Gardner Individual difference variable reflecting affective dimension of learningMotivation:Desire + Effort + Attitude, directed toward a GoalOrientations:Integrative orientationLearning an L2 to communicate with the people who speak it, discovertheir culture, etc.Instrumental orientationLearning a language for a practical purpose, such as to obtainemployment or get by while travelingMotivation and orientationsClément & Kruidenier (1983) also add:Travel orientationFriendship orientationOxford and Shearin (1994): many examples of orientations that they confuse with motivations:Do businessMake friendsIntellectual stimulationPersonal challengeShowing off to friendsAiding world peaceLearn a private code that parents wouldn’t knowTheories in Motivational PsychologyExpectancy-value theoryGoal theorySelf-determination theoryExpectancy-Value Theory IA dominant cognitive approach in recent research on motivational psychology Focus on motivation as:A person’s expectancy of success in a taskThe value the person attributes to success in the taskThree theories of expectancy of successAttribution theorySelf-efficacy theorySef-worth theoryExpectancy-Value Theory IIAttribution theory (Bernard Weiner)Causal attributions of past successes and failures, which will affect future effortsPeople can attribute success to:AbilityEffortTask difficultyLuckOther factors.Attribution of failure to lack of effort can be less demotivating thanattributing it to lack of abilityExpectancy-Value Theory IIISelf-efficacy theory“people’s judgement of their capabilities to carry out certain specific tasks”(Dörnyei, 2001a: 22)Four factors in self-efficacy according to Bandura (1993)Previous performanceVicarious learning (by observing models)Verbal encouragement by othersPhysiological reactionsExpectancy-Value Theory IVSelf-worth theory (Covington)People are motivated to maintain a sense of self-worth (i.e. to feel goodabout themselves)This can lead them to avoid making an effort so that unsatisfactoryperformance can be attributed to lack of effort rather than lack of abilityExpectancy-Value Theory VValue (or valence) component of expectancy-value theories:“Does a person want to do the task?Elements that define the intensity of the motivation4 componentsAttainment value: importance to the person of mastering the skill or task Intrinsic value: interest, esthetic appreciation, enjoymentExtrinsic utility value: relation to goals, how it improves the person’squality of lifeCost: negative component: expended effort and time, anxiety, fear offailureGoal Theories IGoals replace the notion of needs of earlier theoriesVariables in goal setting theory:Specificity of goalDifficulty of goalGoal commitmentGoal Theories IIMain findings of goal theory research (Locke, 1996), quoted in Dörnyei (20001a: 26):The more difficult the goal, the greater the achievementThe more specific or explicit the goal, the more precisely performance isregulatedGoals that are both specific and difficult lead to the highest performance Commitment to goals is most critical when goals are specific and difficult High commitment to goals is attained when (a) the individual is convinced that the goal is important; and (b) the individual is convinced that the goal is attainable.Goal Theories IIIGoal orientation theoryMastery orientationFocus on learning, mastering content: “task-involvement goals”Performance orientationDemonstrate ability, get good grades, do better than others: “ego-involvement goals”Self-determination theory IDistinction between intrinsic and extrinsic regulation of motivationIntrinsic:To experience pleasure, satisfy curiosityExtrinsic:Means to an end, receive awards, avoid punishmentAmotivation:Lack of regulation: “there is no point”; “I don’t know why I’m doing this”feelingSelf-determination theory IIContinuum of different types of extrinsic regulation (Vallerand, Deci & Ryan, Noels et al.)External regulation (or extrinsic): least self-determined: doing somethingdue to external pressuresIntrojected regulation: doing something because you think you should: obeya rule, conform to an external expectationIdentified regulation: doing something because you recognize its personal importance (e.g. hobby)Integrated regulation: doing something because it is considered part ofone’s self-identityMotivation as an individual difference variable in SLASome individual difference variables that have been studied:AgeAptitudeCognitive styleStrategy useAttitudes and MotivationThe role of age in SLAThe Critical Period HypothesisIs there an age after which native-like proficiency in an L2 in no longerattainable?Sometimes called “sensitive period”Research findings mixed: “yes and no”Before age 7, native-like proficiency quite certain7 to 14: more variation in degree of accentednessAfter age 14, native-like proficiency sometimes considered impossible, but some succeedNo biological evidence for critical periodAccess to Universal Grammar (UG) in SLAResearch related to role of age focuses now on learning mechanisms involved:Do L2 learners have access to Universal Grammar (specialized cognitive structures for language)?Issue still the subject of hot debateSome research supports hypothesis of UG accessOther research points to use of general learning mechanisms: e.g. gender in FrenchAptitudeDifferences in natural ability to learn an L2Partly related to general intelligence, partly distinctHas been shown to play an important role in language learning achievement Aptitude is focused on less nowadays in L2 education: preference to think in terms of what can be changedComponents of language learning aptitudePhonemic coding abilityAbility to identify sounds, establish sound-symbol linksGrammatical sensitivityAwareness of grammatical patterns, structuresInductive language learning abilityAbility to infer form-meaning links from contextRote learning abilityAbility to form and remember associations; plays role in vocabulary learningCognitive styleThe way people approach mental tasksOften seen as contrast between field dependence and field independence Field independent learners:Can focus on specific parts of what is being learned, without beingdistracted by overall pictureField dependent learners:More oriented to overall picture with less focus on smaller parts of itRole of cognitive styleIs one cognitive style better than the other for language learning? It depends on what aspects of learning we are considering…Field independent: better at analytical tasks involving grammatical accuracy;stronger on accuracy than fluencyField dependent: better at synthesis, broader picture, general communicative skills, even if not with perfect accuracy; stronger on fluency than accuracyStrategy useLanguage learning strategies: practices that aid language learningRebecca Oxford’s (1990) classification:Direct strategiesCognitive, memory, compensationIndirect strategiesMetacognitive, affective, socialLanguage learning strategiesCognitive strategies: repeating, translating, taking notes, summarizingMemory strategies: associating, using keywords, physical response or sensationCompensation strategies: using clues, switching to L1, using gestureLanguage learning strategiesMetacognitive strategies: organizing, self-monitoring, overviewing and linking already known materialAffective strategies: making positive statements, using relaxation, discussing feelings with other peopleSocial strategies: asking for correction, cooperating with peers, developing cultural understandingA study of strategy useUWO French 021 studentsMemory and cognitive strategies linked to achievement (grades) in the course Memory strategies were least used -- training in them could be helpfulStudents thought strategies could benefit them and should be integrated in curriculumThe “Good language learner” 11.Has an effective personal learning style or positive learning strategies2.Has an active approach to the learning task3.Has a tolerant and outgoing approach to the target language and empathywith its speakers4.Has technical know-how about how to tackle a language5.Has strategies of experimentation and planning with the object of developingthe language into an ordered system and revising this system progressivelyThe “Good language learner” 21.Is constantly searching for meaning.2.Is willing to practise.3.Is willing to use the language in real communication.4.Has self-monitoring ability and critical sensitivity to language use.5.Is able to develop the target language more and more as a separatereference system and to learn to think in it.Gardner’s socio-educational modelLanguage learning is different from learning another subject matterNot just learning facts, but acquiring behaviour, ways of thinking and expressing oneself, that are those of another groupA central concept contributing to language learning success: the integrativemotiveImportance of attitudes:"an attitude is an evaluative reaction to some referent or attitude object,inferred on the basis of the individual's beliefs or opinions about thereferent” (Gardner, 1985: 9)Gardner’s AMTB ISurvey instrument, questionnaire: the Attitudes / Motivation Test Battery (AMTB)Validated in dozens of studies, the only one to have such convincing proof of its validity and statistical reliabilitySeveral questions for each trait studied, e.g. for motivational intensity:I actively think about what I have learned in my French class: a) veryfrequently (3); b) hardly ever (1), c) once in a while (2)A shorter version, the mini-AMTB: one question per traitGardner’s AMTB IIMotivation (mini-AMTB items)Desire: My desire to learn French is: Weak <-> StrongMotivational intensity: I would characterize how hard I work at learningFrench as: Very little <-> Very muchAttitudes toward learning the language: My attitude toward learning French is: Unfavourable <-> FavourableGardner’s AMTB IIIIntegrativeness (mini-AMTB items)Integrative orientation: If I were to rate my feelings about learning French in order to interact with Francophones, I would have to say they are: Weak <-> StrongAttitudes toward the target language group: My attitudes towardsFrancophones is: Favourable <-> UnfavourableInterest in foreign languages: My interest in languages other than French and English is: Very Low <-> Very HighGardner’s AMTB IVAttitudes toward the learning situation (mini-AMTB items)Attitudes toward the instructor: My attitude toward my French professor is: Favourable <-> UnfavourableAttitudes toward the course: My attitude toward my French classes is:Favourable <-> UnfavourableInstrumental orientation (mini-AMTB item):If I were to rate my feelings about learning French for practical purposessuch as to improve my occupational opportunities, I would say that theyare: Weak <-> StrongGardner’s AMTB VAnxiety (mini-AMTB items)French course anxiety: My anxiety level in my French classes is: Very Low <-> Very HighFrench use anxiety: My anxiety in speaking French outside of class is: Very Low <-> Very HighIntegrative motiveThe Integrative motive is composed of:IntegrativenessAttitudes toward the learning situationMotivationMotivation affects the success of learningAttitudes have an indirect effect on learning: their effects are mediated by motivationDebates on the expansion of the model ICrookes & Schmidt (1991): “Reopening the research agenda”, Oxford & Shearin (1994), Dörnyei (1994), criticisms of GardnerHis theory has dominated the field too muchHis approach to motivation doesn’t reflect teachers’ concernsHis theory is limited to the affective dimension from a social psychological approach, without considering other perspective from educationalpsychologyDebates on the expansion of the model IIGardner’s position:Some criticisms based on misinterpretations of his theory (e.g. the mistaken belief that the opposition between integrative and instrumental motivation isa central part of his model)Need to carry out empirical investigations to validate expanded theory« On with the challenge! »Empirical research studiesTremblay & Gardner (1995)Gardner, Tremblay Masgoret (1997): full empirical modelGardner at al. (2004): trait, state, changesGardner & Tennant: expanded mini-AMTBTremblay & Gardner (1995)Incorporation of new concepts in a causal model including socio-educational model elements:Goal-setting theory, Expectancy-value theoryStudy of students in French-language secondary schoolSome results:Language attitudes -> motivated behaviourGoal setting -> motivated behaviorAdaptive attributions -> self-efficiency -> motivated behaviourGardner, Tremblay & Masgoret (1997) I“Towards a full model of second language learning: An empirical investigation” 102 university students in intro FrenchComprehensive questionnaire including AMTB items, aptitude, field dependence/independence, self-confidenceGardner, Tremblay & Masgoret (1997) IIResults show links between:Attitudes and motivationAptitude and achievementMotivation and achievementMotivation and self-confidenceAchievement and self-confidenceStrategy use and achievement (negative correlation)Approaches to motivating our studentsWith all we know (and don’t know) about language learning motivation, can we language teachers motivate our students?We saw a number of suggestions in Zoltán Dörnyei’s “10 commandments’While these haven’t been demonstrated empirically to have definite effects on motivation, they are good tips to tryWilliams and Burden’s suggestions1.Recognize the complexity of motivation2.Be aware of both initiating and sustaining motivation3.Discuss with learners why they are carrying out activities4.Involve learners in decisions related to learning the language5.Involve learners in setting language learning goals6.Recognise people as individualsWilliams and Burden’s suggestions 21.Build up individuals’ beliefs in themselves2.Develop internal beliefs3.Help to move towards a mastery-oriented style4.Enhance intrinsic motivation5.Build up a supportive learning environment6.Give feedback that is informationalDörnyei’s Motivational Strategies ICreating the basic motivational conditions:Demonstrate and talk about your own enthusiasm for the course material, and how it affects you personallyTake the students’ learning very seriouslyDevelop a personal relationship with your studentsCreate a pleasant and supportive atmosphere in the classroomPromote the development of group cohesivenessDörnyei’s Motivational Strategies IIGenerating initial motivation:Raise the learners’ intrinsic interest in the L2 learning processPromote ‘integrative’ values by encouraging a positive and open-mindeddisposition towards the L2 and its speakers, and towards foreignness ingeneralPromote the students’ awareness of the instrumental values associatedwith the knowledge of an L2Increase the students’ expectancy of success in particular tasks and inlearning in generalIncrease your students’ goal-orientedness by formulating explicit classgoals accepted by themDörnyei’s Motivational Strategies IIIMaintaining and protecting motivation:Make learning more stimulating and enjoyable by breaking the monotony of classroom eventsPresent and administer tasks in a motivating wayUse goal-setting methods in your classroomBuild your learners’ confidence by providing regular encouragementHelp diminish language anxiety by removing or reducing the anxiety-producing elements in the learning environmentBuild your learners’ confidence in their learning abilities by teaching them various learner strategiesDörnyei’s Motivational Strategies IVEncouraging positive self-evaluation:Promote effort attributions in your studentsProvide students with positive information feedbackIncrease learner satisfactionOffer rewards in a motivational mannerUse grades in a motivating manner, reducing as much as possible theirdemotivating impactConclusionHave our ideas about motivation changed since the brainstorming at the beginning?。

In the pursuit of academic excellence, it is crucial to develop and refine strategies that foster effective learning. The process of enhancing one's learning experience transcends mere rote memorization and involves a multi-dimensional approach that encompasses cognitive, emotional, and environmental aspects. This essay delves into various key elements that contribute to optimizing learning, offering a comprehensive and high-quality roadmap for students seeking to elevate their academic performance.1. **Establishing a Strong Foundation of Motivation**A compelling drive to learn is the cornerstone of academic success. To cultivate this motivation, it is essential to identify personal goals and aspirations, linking them explicitly to the learning process. This can be achieved by setting specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) objectives, which provide clear direction and a sense of purpose. Moreover, understanding the intrinsic value of knowledge acquisition, such as its potential to broaden perspectives, foster critical thinking, and enhance career prospects, can further fuel motivation.Additionally, extrinsic motivators, such as praise, rewards, or the prospect of higher grades, can also play a role in maintaining momentum. However, it is crucial to strike a balance between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, as overreliance on external factors may undermine long-term interest and engagement.2. **Adopting Effective Study Techniques**The methods we employ to process and retain information significantly impact our learning outcomes. Here are some evidence-based study techniques: **Active Learning:** Engaging in activities like summarizing, discussing, teaching, or applying concepts promotes deeper understanding and retention compared to passive reading or listening. Techniques like the Feynman Technique, where one explains a concept to an imaginary audience in simple terms, can be particularly effective.**Spaced Repetition:** Revisiting material at increasingly longer intervals helps consolidate memories in long-term storage. Tools like flashcards or digital apps like Anki can facilitate this process.**Interleaving:** Alternating between different subjects or types of problems during a study session enhances retention and problem-solving skills by forcing the brain to discriminate and adapt to varying contexts.**Deep Processing:** Encouraging elaboration, organization, and critical thinking about the material, rather than superficial processing, leads to better retention and transfer of knowledge. Techniques like mind mapping or the PQ4R (Preview, Question, Read, Reflect, Recite, Review) method can promote deep processing.3. **Cultivating a Growth Mindset**A growth mindset, as opposed to a fixed mindset, embraces challenges, views effort as a path to mastery, and learns from setbacks. Cultivating this mindset involves:**Embracing Challenges:** Seeing difficult tasks as opportunities for growth rather than threats to competence.**Valuing Effort:** Recognizing that intelligence and talent are malleable and can be developed through persistent effort.**Learning from Failure:** Perceiving failures as informative feedback rather than a reflection of inherent abilities, and using them to adjust strategies and persist in learning.4. **Managing Time Effectively**Efficient time management is vital for balancing academic responsibilities, personal life, and self-care. Strategies include:**Creating a Study Schedule:** Designing a structured yet flexible plan that allocates time for coursework, revision, breaks, and leisure activities.**Prioritizing Tasks:** Using tools like the Eisenhower Matrix to categorize tasks based on urgency and importance, ensuring focus on high-value activities.**Minimizing Distractions:** Identifying and eliminating or mitigating distractions, such as social media or multitasking, to enhance concentration during study sessions.**Practicing Self-Discipline:** Establishing routines, setting boundaries, and holding oneself accountable to maintain consistency and productivity.5. **Promoting Physical and Mental Well-being**Optimal learning is contingent upon good physical and mental health. Steps to nurture well-being include:**Maintaining a Balanced Diet:** Consuming a diet rich in nutrients, vitamins, and minerals to support brain function and energy levels.**Regular Exercise:** Engaging in physical activity to improve mood, reduce stress, and enhance cognitive function.**Quality Sleep:** Ensuring adequate sleep to facilitate memory consolidation, attention, and emotional regulation.**Mental Health Support:** Seeking help when needed, practicing stress-reduction techniques like mindfulness or meditation, and cultivating positive relationships for emotional support.6. **Leveraging Technology and Resources**In today's digital age, technology offers numerous tools and resources to augment learning:**Online Learning Platforms:** Utilizing platforms like Coursera, Khan Academy, or edX for supplementary learning materials, interactive exercises, and expert insights.**Educational Apps:** Exploiting apps like Duolingo, Quizlet, or Evernote to facilitate language learning, memorization, or organization.**Collaborative Tools:** Employing tools like Google Docs, Zoom, or Slack to facilitate group work, discussions, and peer learning.7. **Engaging in Continuous Feedback and Reflection**Continuous assessment and reflection are instrumental in identifying strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement. Strategies include: **Self-Assessment:** Regularly evaluating one's understanding, progress, and study habits using quizzes, self-tests, or reflection journals.**Peer Feedback:** Seeking constructive criticism and suggestions from classmates, study groups, or online forums.**Teacher Feedback:** Actively engaging with instructors, asking questions, attending office hours, and incorporating their feedback into learning strategies.**Formal Assessments:** Analyzing exam results, assignment feedback, and course evaluations to inform future learning approaches.In conclusion, enhancing learning is a holistic endeavor that requires a blend of motivation, effective study techniques, mindset cultivation, time management, well-being promotion, technology utilization, and continuous feedback. By integrating these multifaceted strategies, students can embark on a transformative journey towards academic excellence, fostering not only improved grades but also a lifelong love for learning and a robust set of skills applicable beyond the classroom.。

职业健康和安全管理体系英文Occupational Health and Safety Management System (OHSMS)is a comprehensive approach to managing occupational health and safety issues in the workplace. The system aims to reduce the risk of accidents and illnesses by promoting a safe and healthy working environment.The OHSMS is based on the principles of continuous improvement and focuses on identifying and controlling hazards, assessing risks, and improving safety performance. The system includes policies, procedures, and practicestailored to the needs of the organization.Benefits of OHSMSImplementing an effective OHSMS can bring significant benefits to organizations. These benefits include:1. Improved safety performance: The OHSMS helps identify hazards and assess risks, leading to the implementation of measures that reduce the likelihood of accidents and injuries. This, in turn, leads to improved safety performance, reduced absenteeism, and health care costs.2. Compliance with regulations: The OHSMS helps organizations meet legal requirements related to occupationalhealth and safety. It ensures that the organization is in compliance with applicable laws and regulations, reducing the risk of legal action and penalties.3. Improved reputation: Implementing an OHSMS send a message to stakeholders that the organization is serious about safety and health. It enhances the reputation of the organization, which can attract customers, investors, and talent.4. Increased productivity: A safe and healthy working environment can improve productivity by reducing absenteeism, worker turnover, and injury-related costs.Component of OHSMSAn OHSMS consists of several components, including:1. Policy: The OHSMS policy outlines the organization's commitment to managing occupational health and safety. It defines the roles and responsibilities of employees, management, and other stakeholders.2. Planning: The planning stage involves identifying hazards and assessing risks, setting objectives and targets, and developing action plans to achieve them.3. Implementation: The implementation stage involves putting the plans into practice, including the implementation of policies, procedures, and training programs.4. Measurement and evaluation: The OHSMS measures and evaluates the effectiveness of the program. This involves monitoring and evaluating progress against objectives, identifying areas for improvement, and implementingcorrective action.5. Review: The review stage involves regularly reviewing the OHSMS to ensure it is up-to-date, effective, and meets regulation requirements.ConclusionAn effective OHSMS can bring significant benefits to an organization, including improved safety performance, compliance with regulations, a better reputation, and increased productivity. Organizations can implement an OHSMS by following the key components, including policy, planning, implementation, measurement, evaluation, and review. By prioritizing health and safety, organizations can create a positive working environment that benefits both employees and the organization.。

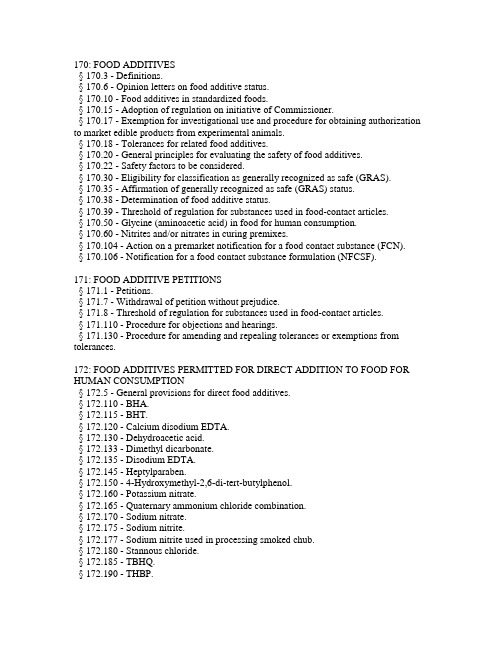

170: FOOD ADDITIVES§ 170.3 - Definitions.§ 170.6 - Opinion letters on food additive status.§ 170.10 - Food additives in standardized foods.§ 170.15 - Adoption of regulation on initiative of Commissioner.§ 170.17 - Exemption for investigational use and procedure for obtaining authorization to market edible products from experimental animals.§ 170.18 - Tolerances for related food additives.§ 170.20 - General principles for evaluating the safety of food additives.§ 170.22 - Safety factors to be considered.§ 170.30 - Eligibility for classification as generally recognized as safe (GRAS).§ 170.35 - Affirmation of generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status.§ 170.38 - Determination of food additive status.§ 170.39 - Threshold of regulation for substances used in food-contact articles.§ 170.50 - Glycine (aminoacetic acid) in food for human consumption.§ 170.60 - Nitrites and/or nitrates in curing premixes.§ 170.104 - Action on a premarket notification for a food contact substance (FCN).§ 170.106 - Notification for a food contact substance formulation (NFCSF).171: FOOD ADDITIVE PETITIONS§ 171.1 - Petitions.§ 171.7 - Withdrawal of petition without prejudice.§ 171.8 - Threshold of regulation for substances used in food-contact articles.§ 171.110 - Procedure for objections and hearings.§ 171.130 - Procedure for amending and repealing tolerances or exemptions from tolerances.172: FOOD ADDITIVES PERMITTED FOR DIRECT ADDITION TO FOOD FOR HUMAN CONSUMPTION§ 172.5 - General provisions for direct food additives.§ 172.110 - BHA.§ 172.115 - BHT.§ 172.120 - Calcium disodium EDTA.§ 172.130 - Dehydroacetic acid.§ 172.133 - Dimethyl dicarbonate.§ 172.135 - Disodium EDTA.§ 172.145 - Heptylparaben.§ 172.150 - 4-Hydroxymethyl-2,6-di-tert-butylphenol.§ 172.160 - Potassium nitrate.§ 172.165 - Quaternary ammonium chloride combination.§ 172.170 - Sodium nitrate.§ 172.175 - Sodium nitrite.§ 172.177 - Sodium nitrite used in processing smoked chub.§ 172.180 - Stannous chloride.§ 172.185 - TBHQ.§ 172.190 - THBP.§ 172.215 - Coumarone-indene resin.§ 172.280 - Terpene resin.§ 172.310 - Aluminum nicotinate.§ 172.320 - Amino acids.§ 172.330 - Calcium pantothenate, calcium chloride double salt.§ 172.335 - D-Pantothenamide.§ 172.340 - Fish protein isolate.§ 172.365 - Kelp.§ 172.372 - N-Acetyl-L-methionine.§ 172.375 - Potassium iodide.§ 172.385 - Whole fish protein concentrate.§ 172.480 - Silicon dioxide.§ 172.490 - Yellow prussiate of soda.§ 172.520 - Cocoa with dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate for manufacturing. § 172.535 - Disodium inosinate.§ 172.560 - Modified hop extract.§ 172.580 - Safrole-free extract of sassafras.§ 172.615 - Chewing gum base.§ 172.620 - Carrageenan.§ 172.626 - Salts of carrageenan.§ 172.655 - Furcelleran.§ 172.660 - Salts of furcelleran.§ 172.665 - Gellan gum.§ 172.695 - Xanthan gum.§ 172.712 - 1,3-Butylene glycol.§ 172.720 - Calcium lactobionate.§ 172.725 - Gibberellic acid and its potassium salt.§ 172.730 - Potassium bromate.§ 172.755 - Stearyl monoglyceridyl citrate.§ 172.765 - Succistearin (stearoyl propylene glycol hydrogen succinate). § 172.780 - Acacia (gum arabic).§ 172.802 - Acetone peroxides.§ 172.804 - Aspartame.§ 172.806 - Azodicarbonamide.§ 172.810 - Dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate.§ 172.811 - Glyceryl tristearate.§ 172.812 - Glycine.§ 172.814 - Hydroxylated lecithin.§ 172.818 - Oxystearin.§ 172.822 - Sodium lauryl sulfate.§ 172.824 - Sodium mono- and dimethyl naphthalene sulfonates.§ 172.828 - Acetylated monoglycerides.§ 172.829 - Neotame.§ 172.830 - Succinylated monoglycerides.§ 172.832 - Monoglyceride citrate.§ 172.833 - Sucrose acetate isobutyrate (SAIB).§ 172.834 - Ethoxylated mono- and diglycerides.§ 172.836 - Polysorbate 60.§ 172.838 - Polysorbate 65.§ 172.840 - Polysorbate 80.§ 172.842 - Sorbitan monostearate.§ 172.844 - Calcium stearoyl-2-lactylate.§ 172.846 - Sodium stearoyl lactylate.§ 172.850 - Lactylated fatty acid esters of glycerol and propylene glycol.§ 172.858 - Propylene glycol alginate.§ 172.860 - Fatty acids.§ 172.861 - Cocoa butter substitute from coconut oil, palm kernel oil, or both oils.§ 172.862 - Oleic acid derived from tall oil fatty acids.§ 172.863 - Salts of fatty acids.§ 172.864 - Synthetic fatty alcohols.§ 172.868 - Ethyl cellulose.§ 172.870 - Hydroxypropyl cellulose.§ 172.872 - Methyl ethyl cellulose.§ 172.874 - Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose.§ 172.876 - Castor oil.§ 172.892 - Food starch-modified.§ 172.894 - Modified cottonseed products intended for human consumption.173: SECONDARY DIRECT FOOD ADDITIVES PERMITTED IN FOOD FOR HUMAN CONSUMPTION§ 173.50 - Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone.§ 173.55 - Polyvinylpyrrolidone.§ 173.60 - Dimethylamine-epichlorohydrin copolymer.§ 173.115 - Alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase ([alpha]-ALDC) enzyme preparation derived from a recombinant Bacillus subtilis.§ 173.145 - Alpha-Galactosidase derived from Mortierella vinaceae var. raffinoseutilizer.§ 173.160 - Candida guilliermondii.§ 173.165 - Candida lipolytica.§ 173.170 - Aminoglycoside 3'-phosphotransferase II.§ 173.275 - Hydrogenated sperm oil.§ 173.345 - Chloropentafluoroethane.§ 173.350 - Combustion product gas.§ 173.355 - Dichlorodifluoromethane.§ 173.360 - Octafluorocyclobutane.§ 173.400 - Dimethyldialkylammonium chloride.174: INDIRECT FOOD ADDITIVES: GENERAL§ 174.5 - General provisions applicable to indirect food additives.§ 174.6 - Threshold of regulation for substances used in food-contact articles.176: INDIRECT FOOD ADDITIVES: PAPER AND PAPERBOARD COMPONENTS§ 176.160 - Chromium (Cr III) complex of N-ethyl-N-heptadecylfluoro-octane sulfonyl glycine.177: INDIRECT FOOD ADDITIVES: POLYMERS§ 177.1390 - Laminate structures for use at temperatures of 250 deg. F and above. 178: INDIRECT FOOD ADDITIVES: ADJUVANTS, PRODUCTION AIDS, AND SANITIZERS§ 178.3480 - Fatty alcohols, synthetic.§ 178.3520 - Industrial starch-modified.180: FOOD ADDITIVES PERMITTED IN FOOD OR IN CONTACT WITH FOOD ON AN INTERIM BASIS PENDING ADDITIONAL STUDY§ 180.1 - General.§ 180.22 - Acrylonitrile copolymers.§ 180.30 - Brominated vegetable oil.§ 180.37 - Saccharin, ammonium saccharin, calcium saccharin, and sodium saccharin.。

自我管理作文英语Self-management is a critical skill that plays a significant role in our personal and professional lives. It encompasses the ability to regulate our emotions, thoughts, and behaviors in different situations, as well as effectively manage our time and resources. In this essay, we will delve into the historical background and development of self-management, analyze various perspectives and opinions surrounding the topic, provide case studies and examples to illustratekey points, offer a critical evaluation of the benefits and drawbacks of self-management, and conclude with future implications and recommendations related to the title.Historical Background and DevelopmentThe concept of self-management has roots in ancient philosophy, with thinkers such as Aristotle and Confucius emphasizing the importance of self-control andself-discipline. However, the modern understanding of self-management has evolved significantly, particularly in the context of organizational behavior and psychology. In the 20th century, influential psychologists like Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers contributed to the development of self-management theories,highlighting the significance of self-awareness, self-regulation, and motivationin achieving personal growth and success. Today, self-management is a key focus in fields such as leadership development, emotional intelligence, and stress management, reflecting its enduring relevance in contemporary society.Different Perspectives and OpinionsThe topic of self-management elicits a wide range of perspectives and opinions. Some individuals view self-management as a fundamental skill for personal and professional success, emphasizing its role in fostering resilience, adaptability, and productivity. They argue that individuals who possess strong self-management abilities are better equipped to navigate challenges, make informed decisions, and achieve their goals. On the other hand, critics may argue that excessive emphasis on self-management can lead to burnout and unrealistic expectations, particularlyin high-pressure work environments. They suggest that a more balanced approach,which incorporates support systems and collective responsibility, is essential for sustainable well-being and performance.Case Studies and ExamplesTo illustrate the importance of self-management, we can consider the case of Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple Inc. Known for his visionary leadership and innovative mindset, Jobs exemplified the power of self-management in driving personal and professional success. Despite facing numerous setbacks and challenges, he maintained a steadfast commitment to his goals, demonstrating resilience, focus, and self-discipline. Similarly, in the context of academic achievement, research has shown that students who possess strong self-management skills, such aseffective time management and goal setting, are more likely to excel in their studies and extracurricular activities. These examples underscore the tangible impact of self-management on individual outcomes and success.Critical Evaluation of Benefits and DrawbacksWhile self-management offers various benefits, it is essential to critically evaluate its drawbacks and limitations. One potential drawback is the risk of excessive self-reliance, which may hinder individuals from seeking support or collaboration when needed. Moreover, the pressure to constantly self-manage can contribute to stress and anxiety, particularly in competitive and fast-paced environments. Additionally, individuals with limited access to resources or facing systemic barriers may encounter challenges in developing and applying self-management skills, highlighting the importance of addressing broader societal factors in fostering personal development.Future Implications and RecommendationsLooking ahead, the future implications of self-management are multifaceted. As technology continues to reshape the nature of work and communication, individuals will need to adapt and refine their self-management skills to thrive in evolving environments. Furthermore, there is a growing recognition of the interconnectedness between individual well-being and organizational success, underscoring the need for holistic approaches to self-management that prioritizemental health and work-life balance. To that end, recommendations for promoting effective self-management include integrating well-being initiatives in educational and workplace settings, fostering a culture of open communication and support, and providing accessible resources for skill development and self-care.In conclusion, self-management is a complex and multifaceted topic that holds significant implications for personal and professional development. By examining its historical background, analyzing different perspectives, and critically evaluating its benefits and drawbacks, we gain a deeper understanding of its relevance in contemporary society. As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, the cultivation of effective self-management skills emerges as a valuable asset for individuals and organizations alike. Embracing a balanced and inclusive approach to self-management, grounded in empathy and self-awareness, can pave the way for sustainable well-being and success in the future.。

Selfmanagement is a crucial skill that enables individuals to effectively organize and regulate their own behavior,emotions,and time.Cultivating good habits in selfmanagement can significantly enhance ones productivity,wellbeing,and overall quality of life.Here are some key aspects to consider when writing an essay on selfmanagement and good habits:1.Introduction to SelfManagement:Begin by defining selfmanagement and its importance in personal and professional development.Explain how it differs from being managed by others and the benefits of taking control of ones own life.2.Importance of Good Habits:Discuss the significance of good habits in selfmanagement. Good habits are behaviors that are regularly practiced and lead to positive outcomes. They can be the foundation of a selfmanaged lifestyle.3.Setting Goals:Explain the role of goal setting in selfmanagement.Setting clear, achievable goals is the first step towards selfregulation.Goals provide direction and motivation.4.Time Management:Time is a limited resource,and effective selfmanagement involves using it wisely.Discuss techniques such as prioritization,scheduling,and avoiding procrastination.5.Emotional Regulation:Managing emotions is a critical aspect of selfmanagement. Describe how being aware of ones emotional state and responding appropriately can lead to better decisionmaking and stress reduction.6.Healthy Lifestyle Choices:Good habits in selfmanagement extend to physical health. Discuss the importance of regular exercise,a balanced diet,and adequate sleep in maintaining energy levels and focus.7.Continuous Learning:Selfmanagement is not a static process.It requires continuous learning and adaptation.Highlight the importance of being open to new information and experiences to improve selfmanagement skills.8.Adopting Technology:In the modern world,technology can be a powerful tool for selfmanagement.Discuss apps and tools that can help with goal setting,time management,and tracking progress.9.Overcoming Obstacles:No selfmanagement strategy is without its challenges.Discuss common obstacles such as distractions,lack of motivation,and setbacks,and how toovercome them.10.Reflection and Adaptation:Regular reflection on ones selfmanagement practices is essential for growth.Discuss the importance of evaluating habits and strategies and adapting them as needed.11.Conclusion:Summarize the key points made in the essay and emphasize the longterm benefits of good selfmanagement habits.Encourage readers to take steps towards improving their own selfmanagement skills.12.Call to Action:End the essay with a call to action,urging readers to start implementing selfmanagement habits in their own lives and to continuously strive for improvement.Remember to use clear examples and evidence to support your points,and to write in a clear,engaging,and persuasive style to effectively communicate the value of selfmanagement and good habits.。

原文:Merger Policy and Tax CompetitionIn many situations governments have sector-specific tax and regulation policies at their disposal to influence the market outcome after a national or an international merger has taken place. We find that whether national or international mergers are more likely to be enacted in the presence of nationally optimal tax policies depends crucially on the ownership structure of firms. When all firms are owned domestically in the premerger situation, non-cooperative tax policies are more efficient in the national merger case and smaller synergy effects are needed for this type of merger to be proposed and cleared. These results are reversed when there is a high degree of foreign firm ownership prior to the merger.Mergers have played a prominent role over the past decade, and international merger activity has grown particularly fast. During the period 1981-1998 the annual number of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) has increased more than fivefold and the share of cross-border mergers has reached more than one quarter of the total by the end of this period. This increase in merger activity has led to situations where a national or an international merger have been in direct competition with each other. A recent example has been the bidding race for the leading Spanish electricity provider Endesa, where the German-based E.ON company initially competed with the Spanish-based rival Gas Natural. The Spanish authorities favored the national merger and formulated severe obstacles to an international take-over by E.ON, which was one of the reasons why E.ON eventually withdrew its bid.A different approach has been taken by the British government, which has fully liberalized its electricity market in the early 1990s. In this process, foreign electricity providers (among them E.ON ) took over a large part of the British electricity industry. The British government responded to high profits in this and other privatized industries by imposing a one-time, sector-specifi c ‘windfall pro fi t tax’ in 1997. Since then, a renewed imposition of this tax has been repeatedly discussed as a complement to the regulation of prices through the regulation authority Ofgem (Office of Gas and Electricity Markets).The last example shows clearly that national governments dispose overadditional policy instruments in an industry where a merger or a foreign acquisition has taken place. Price regulation in privatized `network industries' is one important way to increase domestic consumer surplus at the expense of corporate profits, which often accrue, at least in part, to foreign shareholders. Sector-specific profit taxes have very similar effects, if their proceeds are redistributed to consumers in compensation for higher goods prices. On the other hand, there are also many industries where subsidies are granted in order to improve the competitiveness of domestic products in world markets. One set of examples are direct subsidies to specific sectors, such as mining, shipbuilding, steel production, or airplane construction. Moreover, several of these sectors and several others (e.g. air transportation) also receive indirect subsidies by paying reduced rates of excise taxes, in particular mineral oil or electricity taxes. To the extent that these `eco taxes' represent Pigouvian taxes that cause firms to internalize the true social cost of their products, such tax rebates also represent subsidies to the involved sectors and, importantly, to the electricity and energy sector itself. In all these cases, sector-specific tax or subsidy policies can be adjusted by national policymakers in response to a change in market structure caused by a merger.we argue that the possibility to levy industry-specific taxes or subsidies in a nationally optimal way has important repercussions on the position that national regulation authorities take vis-µa-vis a national or an international merger proposal. At the same time, merging firms will incorporate a possible change in policy when deciding about a merger in a particular country. To analyze this interaction between tax and merger policies we set up a model where both firms and merger regulation authorities anticipate that taxes will be optimally adjusted in the host country after a merger has taken place. More specifically, we investigate a setting of Cournot quantity competition between four producing firms where two firms are located in each of two symmetric countries. Importantly, these firms may have foreign shareholders, thus giving an incentive to each government to employ profit taxes that can be partly exported to foreigners.Starting from a market structure of double duopoly, our focus is on the comparison between a national merger in one of the countries and an international merger between a home and a foreign firm.Our analysis shows that the relative attractiveness of a national versus an international merger depends critically on the degree of foreign firm ownership. When all firms are nationally owned prior to the merger, then a national merger will lead to more efficient tax policies as compared to the international merger. In contrast, when the level of foreign firm ownership is high initially, then non-cooperative tax policies in the host countries will be more efficient under the international merger. Extending the model to allow for synergy effects of mergers, we show that these welfare properties translate into the national (international) merger being more likely to be proposed and adopted when the degree of foreign firm ownership is low (high). These results imply that a more geographically dispersed ownership structure of firms, in combination with non-cooperatively chosen national tax policies, may offer one explanation for the recent surge in cross-border merger activity.Our analysis relates to two strands in the literature. First, there is a growing recent literature on merger policies in open economies. This literature, however, typically regards merger control as an isolated policy problem for national or international regulators. The literature that analyses the interaction of merger control with other policy instruments is scarce, and it almost exclusively focuses on international trade policies as the additional policy variable (Richardson, 1999; Horn and Levinsohn, 2001; Huck and Konrad, 2004; Saggi and Yildiz, 2006). In contrast, the interaction between merger policy and national tax policies has not been addressed in this literature so far. A second literature strand on which our paper builds is the analysis of optimal commodity taxation in oligopolistic markets (Keen and Lahiri, 1998; Lockwood, 2001; Keen et al., 2002;Haufler et al.,2005;Hashimzade et al.,2005). This literature, however, has focused mainly on issues of commodity tax harmonization and the choice of commodity tax regime under an exogenously given market structure. It has not addressed the implications for tax policy that follow from changes in the underlying market conditions as a result of mergers.The plan of the paper is as follows. Section 2 describes the basic framework for our analysis. Section 3 presents the benchmark case of double duopoly, where two firms are located in each country and all four firms compete in both markets. Section4 analyzes the changes in tax policies and welfare when a national merger occurs in one of the countries. Section5 carries out the same analysis for an international merger. Section6 introduces synergy effects associated with a national and an international merger and compares the conditions under which one or the other type of merger is proposed and accepted by merger authorities. Section7 concludes.In practice a core motivation for firms to undertake mergers, and an important reason for regulation authorities to permit them, is that mergers can create synergy effects. We analyze how large the cost savings must be for a national or an international merger in order to be in the interest of both the merging firms and the regulation authority of the host country. We deal again with different ownership structures of firms. Due to the complexity of the resulting expressions, we confine the discussion in the main text to the polar cases of full national ownership and complete international ownership diversificationWe should observe a positive and systematic relationship between the foreign ownership share and the share of cross-border mergers in a particular industry. There is indeed some first, suggestive evidence in favour of this proposition. In the OECD countries the share of cross-border mergers in the total number of M&A cases differs widely across different economic sectors and is highest in manufacturing. At the same time, manufacturing is also one of the most internationalized sectors with respect to foreign ownership, at least in European countries. Similarly, there are sectors with a low share of foreign firm ownership, such as construction, where the share of cross-border mergers in the total number of M&A cases is also low. A detailed empirical study would be needed to rigorously test whether this positive relationship between foreign ownership and the share of cross-border mergers holds more generally, and whether it can be linked to the interaction of nationally optimal tax policies and merger control.In many industries governments have sector-specific tax and regulation policies at their disposal to influence the market outcome after a change in market structure has occurred. In this paper we have set up a simple model to analyze how nationally optimal tax rates will be adjusted in response to a national merger on the one hand andan international merger on the other. Extending the analysis to incorporate synergy effects of mergers, we have then studied how these changes in tax policy feed back on the incentives for firms to propose one or the other kind of merger, and for the merger regulation authorities to accept it.Our analysis shows that a national and an international merger lead to different incentives for national tax policy. On the one hand an international merger increases the 24 incentives for non-cooperative tax policy to tax foreign firm owners in excess of the efficient levels. On the other hand, an international merger leads to a larger share of consumption in each country being served by local producers and thus increases the incentive for each country to grant Pareto efficient subsidies. Which of these two effects dominates depends crucially on the share of foreign firm ownership in the pre-merger situation. If all firms are locally owned initially, then the national merger is the dominant alternative, in the sense that it requires fewer cost savings in order to be proposed by the merging firms and to be cleared by the regulation authority. In contrast, if the share of foreign firm ownership is large, then the international merger will be proposed and cleared for a wider range of cost savings.One implication of our model is that a rise in international portfolio diversification will favour cross-border mergers, other things being equal. When, as it is often argued, a rise in foreign asset holdings is one of the consequences of economic integration, then our analysis provides an explanation for the rising share of cross-border mergers. In principle our argument is complementary to other reasons for cross-border mergers found in the literature, in particular the argument that they allow firms to save aggregate transport costs. It is interesting to note, however, that this alternative argument cannot explain a rising share of cross-border mergers over time, as it becomes less important when economic integration proceeds and transport costs accordingly fall.Our analysis could be extended in several directions. One possibility would be to indigenize the share of foreign firm ownership, and relate this share explicitly to the forces of economic integration. In such a setting international portfolio diversification would lead to gains in the form of higher returns or lower aggregate risk, but it wouldalso cause higher information or transaction costs. If economic integration reduces the latter, the link between globalization and the rise of cross-border mergers could be explicitly modeled. We do not expect, however, that our conclusions would be fun- dementally altered by this extension. Another model extension would be to consider consecutive mergers, or `merger waves'. In such a setting it would be possible to derive equilibrium market structures for any given set of exogenous model parameters (as in Horn and Parson, 2001). In principle this extension could be incorporated into our model, but the analysis must account for both the change in market structure and for the change in tax policies following each merger. We leave this task for future research.Source: Andreas Haufle, 2007.”Merger Policy and Tax Competition”, Munich Discussion Paper No.39 P25-35.译文:合并政策和税收竞争通常政府有特定部门的税收和管理政策来处理国内并购或者跨国并购中产生的市场问题。

510(k) SUBSTANTIAL EQUIVALENCE DETERMINATIONDECISION SUMMARYINSTRUMENT ONLY TEMPLATEA. 510(k) Number:k170983B.Purpose for Submission:Modification of a previously cleared device to add a 6 second exhalation modeC.Manufacturer and Instrument Name:Circassia AB NIOX VEROD.Type of Test or Tests Performed:QuantitativeE. System Descriptions:1. Device Description:NIOX VERO is a portable system for the non‐invasive, quantitative measurement of the fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (NO) in expired human breath (FeNO).The NIOX VERO system is comprised of the NIOX VERO unit with AC adapter, arechargeable battery, an electrochemical NO sensor, disposable patient filters, and anexchangeable handle containing an internal NO scrubber filter. The NIOX Panel is anoptional PC application for operation of the NIOX VERO from a PC and access toelectronic medical record systems. The device can connect to the PC via a standard USB cable or wirelessly via Bluetooth.For testing, the patient empties their lungs, inhales deeply through the patient filter tototal lung capacity and then slowly exhales for 6 or 10 seconds, depending on the mode of operation. The default mode of operation is the 10 second exhalation mode. Inapproximately one minute, the NO concentration is displayed in parts per billion (ppb).Results are processed using dedicated software. The device has built‐in system controlprocedures and a Quality Control procedure to be performed on a daily basis.2. Principles of Operation:The measurement principle is based on American Thoracic Society guidelines (ATS/ERS Recommendations for Standardized Procedures for the Online and Offline Measurement of Exhaled Lower Respiratory Nitric Oxide and Nasal Nitric Oxide, 2005. Am J RespirCrit Care Med. 2005;171:912-930). The last three second fraction of a 6 second or 10 second exhalation is evaluated for average NO concentration. The exhalation flow is controlled to 50 ml/s ±5 ml/s at an applied pressure of 10 to 20 cm H2O. Sample isevaluated in 25 seconds (2 ml/sec for 25 seconds). The inhaled air is NO free. NO is measured using electrochemical detection. There is a gas inlet chamber with anelectrolyte (sulfuric acid solution) and hardware. The NO molecules diffuse through the membrane and reach the electrolyte. A chemical reaction takes place where one electron for each NO molecule is generated. The current is proportional to the number ofconverted NO molecules.3. Modes of Operation:Does the applicant’s device contain the ability to transmit data to a computer, webserver, or mobile device?Yes ___X____ or No ________Does the applicant’s device transmit data to a computer, webserver, or mobile device using wireless transmission?Yes ___X____ or No ________4. Specimen Identification:There is no mechanism to identify the specimen.5. Specimen Sampling and Handling:The user obtains a breath sample by exhaling into the device.6. Calibration:The manufacturer performs calibration for each NIOX VERO sensor. NIOX VERO sensor is an electrochemical sensor pre-calibrated and pre-programmed for a defined number of tests (60, 100, 300, 500, or 1000 tests).The user exchanges the sensor upon expiration. The instrument prompts the user for upcoming exchange prior to sensorexpiration and does not allow for measurements with an expired sensor. No additional calibration is needed during the lifetime of the sensor.7. Quality Control:NIOX VERO provides internal controls as well as an External Quality Control program for the user to verify the reliability of measurements.8. Software:FDA has reviewed applicant’s Hazard Analysis and Software Development processes for this line of product types:Yes___X____ or No________F. Regulatory Information:1. Regulation section:21 CFR 862.3080, Breath nitric oxide test system2. Classification:Class II3 Product code:MXA4. Panel:Clinical Chemistry (75)G. Intended Use:1. Indication(s) for Use:NIOX VERO measures Nitric Oxide (NO) in human breath. Nitric Oxide is frequentlyincreased in some airway inflammatory processes such as asthma. The fractional NOconcentration in expired breath (FeNO), can be measured by NIOX VERO according to guidelines for NO measurement established by the American Thoracic Society.Measurement of FeNO by NIOX VERO is a quantitative, non-invasive, simple and safe method to measure the decrease in FeNO concentration in asthma patients that oftenoccurs after treatment with anti-inflammatory pharmacological therapy, as an indication of the therapeutic effect in patients with elevated FeNO levels. NIOX VERO is suitable for children, 7- 17 years, and adults 18 years and older.NIOX VERO 10 second test mode is for age 7 and up.NIOX VERO 6 second test mode is for ages 7-10 only who cannot successfully completea 10 second test.FeNO measurements provide the physician with means of evaluating an asthma patient'sresponse to anti-inflammatory therapy, as an adjunct to the established clinical andlaboratory assessments in asthma. The NIOX VERO is intended for prescription use and should only be used as directed in the NIOX VERO User Manual by trained healthcareprofessionals. NIOX VERO cannot be used with infants or by children under the age of 7 as measurement requires patient cooperation.NIOX VERO should not be used in critical care, emergency care or in anesthesiology.2. Special Conditions for Use Statement(s):NIOX VERO should only be operated by trained healthcare professionals and only after careful reading of the NIOX VERO User Manual.The device should not be used with infants or by children under the age of 7, or anypatient who cannot cooperate with any necessary requirements of test performance.The device should not be used in critical care, emergency care or in anaesthesiology.Subjects should not smoke in the hour before measurements, and short- and long-termactive and passive smoking history should be recorded. In addition, subjects shouldrefrain from eating and drinking for 1 hour before exhaled NO measurement. Alcoholingestion reduces FENO in patients with asthma and healthy subjects FENO.It is prudent, where possible, to perform serial NO measurements in the same period ofthe day and to always record the time.For prescription use only.H. Substantial Equivalence Information:1. Predicate Device Name(s) and 510(k) numbers:NIOX VERO Airway Inflammation Monitor; k1502332. Comparison with Predicate Device:I. Special Control/Guidance Document Referenced (if applicable):·AAMI/ANSI ES60601-1:2005/(R)2012 And A1:2012,C1:2009/(R)2012 And A2:2010/(R)2012(Consolidated Text) Medical·IEC 60601-1-6 Edition 3.1 2013-10, Medical Electrical Equipment - Part 1-6: General Requirements For Basic Safety And Essential·AAMI / ANSI / ISO 14971:2007/(R)2010, Medical Devices - Applications Of Risk Management To Medical Devices·CLSI EP5-A2 Vol 24 No. 25 Evaluation of Precision Performance of Quantitative Measurement methods·CLSI EP6-A vol 23, no. 16, Evaluation of the Linearity of Quantitative Measurement Procedures: A Statistical Approach·CLSI EP09-A2, Measurement Procedure Comparison And Bias Estimation Using Patient Samples; Approved Guideline – Third Edition. (InVitro Diagnostics) ·CLSI EP09-A3, Measurement Procedure Comparison And Bias Estimation Using Patient Samples; Approved Guideline – Third Edition. (InVitro Diagnostics)J. Performance Characteristics:1. Analytical Performance:a. Accuracy:A method comparison study was performed to assess the agreement between the 6second and 10 second exhalation modes of the NIOX VERO in patients ages 7 – 10.The difference in FeNO measurements between the 6 second and 10 secondexhalation modes was not clinically significant.b. Precision/Reproducibility:Analytical precision for the 6 second exhalation mode was evaluated based on theCLSI standard EP5-A2. A certified NO calibration gas concentration of 200 ppb wasmixed with nitrogen gas in a gas mixer to create concentrations of 5, 25, 75, and 200ppb. Data was collected over 20 operating days, two runs per day, with duplicatedeterminations for each concentration. The repeatability and within-device precisionover 20 days were determined for each concentration. Five NIOX VERO sensors,continually mounted in 5 NIOX VERO instruments, respectively, were used. Theresults at the 5 and 25 ppb levels, expressed as standard deviation (ppb), and at the 75and 200 ppb levels, expressed as percent CV (%), are as follows:c. Linearity:Linearity of measurements using the 6 second exhalation mode was determined using certified NO at 200 ppb and 2000 ppb in nitrogen calibration gas mixed with nitrogen gas in a gas mixer, connected in-line with the NIOX VERO instrument, (withmounted NIOX VERO sensors), to obtain 7 NO concentration levels (3, 5, 25, 100,200, 300 and 330 ppb). Five replicate determinations of the concentrations at 3 and 5 ppb, and three replicate determinations on the other intervals were made.For the 10 devices tested, the regression analysis gave slopes of 1.05 to 1.09 andintercept ± 4 ppb. The squared correlation coefficient r2 was 0.999 for all 10 devices tested. Results indicate linearity within the 5-300 ppb measuring range.Effects of Temperature and Relative HumidityThe effects of temperature and relative humidity were characterized in k133898.Please refer to the Decision Memorandum for k133898 for details.d. Carryover:Not applicablee. Interfering Substances:The effect of potentially interfering substances was characterized in k133898.2. Other Supportive Instrument Performance Data Not Covered Above:Other clinical supportive data:A clinical study was not conducted with the 6 second mode of the NIOX VERO device.In 2007, a multi-center device randomized open-label prospective single-cohort study was conducted to demonstrate substantial equivalence between NIOX MINO andpredicate device (NIOX) when measuring the change of FeNO that often occurs after 2 weeks of corticosteroid therapy compared to their baseline levels. Symptomatic asthmatic males and females performed two valid FeNO measurements at each visit, with NIOX MINO and NIOX respectively, with a limit of six exhalation attempts per subject in each device. The order of the FENO measurement on NIOX MINO versus NIOX wasrandomized. At every visit and for every patient, spirometry was performed and asthma symptoms were recorded using Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ). In total, 156subjects were included, 105 adults 18 - 70 years old and 51 children 7 - 17 years old.Results from this study, in conjunction with the new method comparison study described above, were determined to be applicable to the 6 second mode of the candidate device, the NIOX VERO. See k072816 for more details.Traceability, Stability, Expected values (controls, calibrators, or methods):The NIOX VERO instrument is calibrated by the manufacturer and does not requirecalibration by the user. A replaceable sensor is used which is pre-programmed and pre-calibrated for a defined number of tests. The life time of NIOX VERO instrument is setto 5.5 years. The number of possible tests is 15000. The sensor life time is limited to 12 months in unopened packaging following manufacture, for 6 months from initialinstallation into NIOX VERO, or for the defined number of tests (60, 100, 300, 500 or1000), whichever comes first. The shelf life for NIOX Filter in unopened primarypackage is 2 years. NIOX Filter is for single use and must be replaced for every newpatient and measurement occasion. Stability information to support all claims wasreviewed in k133898.Detection limit:The detection limit of the NIOX VERO using the 6 second mode was determined in alaboratory setting, using mixtures of standard reference NO gas and nitrogen gas belowand above the detection limit, at 3 and 5 ppb. Five replicate determinations of eachconcentration were made. 10 NIOX VERO sensors, continually mounted in 10 NIOXVERO instruments, respectively, were used in these tests. The results of the study support the claimed detection limit of 5 ppb for the 6 second mode.Expected values/Reference range:The expected values are provided from the literature. In the labeling the sponsor states,“Given that physiological and environmental factors can affect FeNO, FeNO levels inclinical practice need to be established on an individual basis. However, most healthyindividuals will have NO levels in the range 5-35 ppb (children slightly lower, 5-25 ppb) when measured at 50 ml/s.(ATS/ERS Recommendations for Standardized Procedures for the Online and OfflineMeasurement of Exhaled Lower Respiratory Nitric Oxide and Nasal Nitric Oxide, 2005.Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:912-930.)”K. Proposed Labeling:The labeling is sufficient and it satisfies the requirements of 21 CFR Part 809.10.L. Conclusion:The submitted information in this premarket notification is complete and supports asubstantial equivalence decision.。