英语翻译诗经赏析共16页

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:3.27 MB

- 文档页数:16

诗经采薇翻译及赏析《小雅・采薇》是中国古代现实主义诗集《诗经》中的一篇。

这是一首戎卒返乡诗,唱出从军将士的艰辛生活和思归的情怀。

全诗六章,每章八句。

下面是诗经采薇翻译及赏析,请参考!诗经采薇翻译采薇采薇一把把,薇菜新芽已长大。

说回家呀道回家,眼看一年又完啦。

有家等于没有家,为跟�N狁去厮杀。

没有空闲来坐下,为跟�N狁来厮杀。

采薇采薇一把把,薇菜柔嫩初发芽。

说回家呀道回家,心里忧闷多牵挂。

满腔愁绪火辣辣,又饥又渴真苦煞。

防地调动难定下,书信托谁捎回家!采薇采薇一把把,薇菜已老发杈��。

说回家呀道回家,转眼十月又到啦。

王室差事没个罢,想要休息没闲暇。

满怀忧愁太痛苦,生怕从此不回家。

什么花儿开得盛?棠棣花开密层层。

什么车儿高又大?高大战车将军乘。

驾起兵车要出战,四匹壮马齐奔腾。

边地怎敢图安居?一月要争几回胜!驾起四匹大公马,马儿雄骏高又大。

将军威武倚车立,兵士掩护也靠它。

四匹马儿多齐整,鱼皮箭袋雕弓挂。

哪有一天不戒备,军情紧急不卸甲!回想当初出征时,杨柳依依随风吹;如今回来路途中,大雪纷纷满天飞。

道路泥泞难行走,又渴又饥真劳累。

满心伤感满腔悲。

我的哀痛谁体会!赏析这首诗的主题是严肃的。

猃狁的凶悍,周朝军士严阵以待,作者以戍役军士的身份描述以天子之命命将帅、遣戍役,守卫中国,军旅的严肃威武,生活的紧张艰辛。

作者的爱国情怀是通过对猃狁的仇恨来表现的。

更是通过对他们忠于职守的叙述――“不遑启居”、“不遑启处”、“岂敢定居”、“岂不日戒”和他们内心极度思乡的强烈对比来表现的。

全诗再衬以动人的自然景物的描写:薇之生,薇之柔,薇之刚,棠棣花开,依依杨柳,霏霏雨雪,都烘托军士们“日戒”的生活,心里却是思归的情愫,这里写的都是将士们真真实实的思想,忧伤的情调并不降低本篇作为爱国诗篇的价值,恰恰相反是表现人们的纯真朴实,合情合理的思想内容和情感,也正是这种纯正的真实性,赋予这首诗强盛的生命力和感染力。

第一部分的三章采用重章叠句的形式,反复表达戍卒远别家室、历久不归的凄苦心情。

《Scarborough Fair》卡萨布兰卡歌词诗经版翻译(英语学习)Scarborough Fair(斯卡堡集市,也译作“斯卡波罗集市”),是一首旋律优美的经典英文歌曲,曾作为第40届奥斯卡获奖影片《毕业生》(The Graduate)的插曲,曲调凄美婉转,给人以心灵深处的触动。

《Scarborough Fair》原是一首古老的英国民歌,其起源可一直追溯到中世纪,原唱歌手为保罗·西蒙(Paul Simon)和阿特·加芬克尔(Art Garfunkel)。

莎拉·布莱曼(Sarah Brightman)翻唱过该歌曲,此外来自英伦岛屿的Gregorian格里高利合唱团(又称“教皇合唱团”)也曾翻唱过该歌曲。

Are you going to Scarborough Fair问尔所之,是否如适。

Parsely sage rosemary and thyme.蕙兰芫荽,郁郁香芷。

Remember me to one who lives there. 彼方淑女,凭君寄辞。

She was oncea true love of mine.伊人曾在,与我相知。

Tell her to make me a cambric shirt. 嘱彼佳人,备我衣缁。

Parsely sage rosemary and thyme.蕙兰芫荽,郁郁香芷。

Without no seams nor needle work. 勿用针砧,无隙无疵。

Then she will be a true love of mine.伊人何在,慰我相思。

On the side of hill in the deep forest green,彼山之阴,深林荒址。

Tracing of sparrow on snow crested brown冬寻毡毯,老雀燕子。

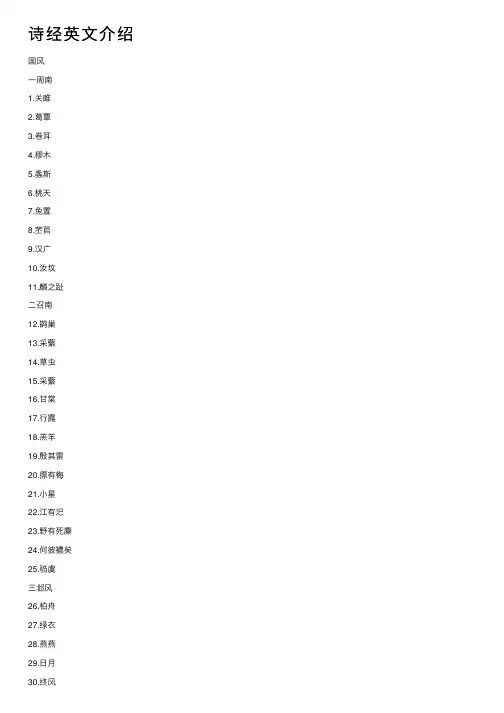

诗经英⽂介绍国风⼀周南1.关雎2.葛覃3.卷⽿4.樛⽊5.螽斯6.桃天7.兔置8.苤苢9.汉⼴10.汝坟11.麟之趾⼆召南12.鹊巢13.采蘩14.草⾍15.采蘩16.⽢棠17.⾏露18.羔⽺19.殷其雷20.摽有梅21.⼩星22.江有汜23.野有死麇24.何彼襛矣25.驺虞三邶风26.柏⾈27.绿⾐28.燕燕33.雄雉34.匏有苦叶35.⾕风36.式微37.旄丘38.简兮39.泉⽔40.北门41.北风42.静⼥43.新台44.⼆⼦乘⾈四鄘风45.柏⾈46.墙有茨47.君⼦偕⽼48.桑中49.鹑之奔奔50.定之⽅中51.蝃蝀52.相⿏53.⼲旄54.载驰五卫风55.淇奥56.考槃57.硕⼈58.氓59.⽵竿60.芄兰61.河⼴62.伯兮67.君⼦阳阳68.扬之⽔69.中⾕有蕹70.兔爰71.葛藟72.采葛73.⼤车74.丘中有⿇七郑风75.缁⾐76.将仲⼦77.叔于⽥78.⼤叔于⽥79.清⼈80.羔裘81.遵⼤路82.⼥⽇鸡鸣83.有⼥同车84.⼭有扶苏85.萚兮86.狡童87.褰裳88.丰89.东门之蝉90.风⾬91.⼦衿92.扬之⽔93.出其东门94.野有蔓草95.溱洧100.东⽅未明101.南⼭102.甫⽥103.芦令104.敝笱105.载驱106.猗嗟九魏风107.葛屦108.汾沮洳109.园有桃110.陟岵111.⼗亩之间112.伐檀113.硕⿏⼗唐风114.蟋蟀115.⼭有枢116.扬之⽔117.椒聊118.绸缪119.卡⼤杜120.羔裘121.鸨⽻122.⽆⾐123.有卡⼤之杜124.葛⽣125.采苓⼗⼀秦风126.车邻127.驷驖128.⼩戎129.蒹葭130.终南131.黄鸟132.晨风133.⽆⾐134.渭阳135.权舆⼗⼆陈风136.宛丘137.东门之扮138.衡门139.东门之池140.东门之杨141.墓门142.防有鹊巢145.泽陂⼗三桧风146.羔裘147.素冠148.隰有苌楚149.匪风⼗四曹风150.蜉蝣151.候⼈152.鸤鸠153.下泉⼗五豳风154.七⽉155.鸱鹗156.东⼭157.破斧158.伐柯159.九罭160.狼跋风周南召南邶风鄘风卫风王风郑风齐风魏风唐风秦风陈风桧风雅⿅鸣之什南有嘉鱼之什鸿雁之什节南⼭之什⾕风之什甫⽥之什鱼藻之什⽂王之什⽣民之什荡之什颂周颂·清庙之什周颂·⾂⼯之什周颂·闵予⼩⼦之什鲁颂·駉之什商颂Book of Songs (Chinese)From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia(Redirected from Shi Jing)Jump to: navigation, searchThe Book of Songs (simplified Chinese: 诗经; traditional Chinese: 詩經; pinyin: Shī Jīng; Wade-Giles: Shih Ching), translated variously as the Classic of Poetry, or the Book of Odes, is the earliest existing collection of Chinese poems. It comprises 305 poems, some possibly written as early as 1000 BC. It forms part of the Five Classics.The Book of Songs is the best source for the daily lives, hopes, complaints and beliefs of ordinary people in the early Zhou period. Over half of the poems are said to have originally been popular songs. They concern basic human problems such as love, marriage, work, and war. Others include court poems, and legendary accounts praising the founders of the Zhou dynasty. Included are also hymns used in sacrificial rites,[1] and songs used by the arisotracy in their sacrificial ceremonies or at banquets.[2]The poems of Book of Songs have strict patterns in both rhyme and rhythm, make much use of imagery, and tend to be short; they set the pattern for later Chinese poetry. The Book of Songs is regarded as a revered Confucius classic, and has been studied and memorized by centuries of scholars in China.[3] The popular songs were seen as good keys to understanding the troubles of the common people, and were often read as allegories; complaints against lovers were seen as complaints against faithless rulers, for example.[4] Confucius was supposed to have selected and edited the poems from a much larger body of material.[5]Contents[hide]1 The collectiono 2.2 Xiao Yao 2.3 Da Yao 2.4 Song3 Trivia4 Translations5 See also6 Notes7 References8 External links[edit] The collectionThe collection is divided into three parts according to their genre, namely feng, ya and song, with the ya genre further divided into "small" and "large":ChinesePinyin Number and Meaningcharacter(s)⾵fēng160 folk songs (or airs)⼩雅xiǎoyǎ74 minor festal songs (or odes traditionally sung at court festivities) ⼤雅dàyǎ31 major festal songs, sung at more solemn court ceremonies頌sòng 40 hymns and eulogies , sung at sacrifices to gods and ancestral spirits of the royal houseThe Confucian tradition holds that the collection, one of the Wu Jing, or Five Classics, came to what we have today after the editing of Confucius. The collection was officially acknowledged as one of "Five Classics" during the Han Dynasty, and previously in Zhou Dynasty Shi (詩) was one of "Six Classics". Four schools of commentary existed then, namely the Qi (⿑), the Lu (魯), the Han (韓), and the Mao (⽑) schools. The first two schools did not survive. The Han school only survived partly. The Mao school became the canonical school of Book of Songs commentary after the Han Dynasty. As a result, the collection is also sometimes referred to as "Mao Shi" (⽑詩). Zheng Xuan's elucidation on the Mao commentary is also canonical. The 305 poems had to be reconstructed from memory by scholars since the previous Qin Dynasty had burned the collection along with other classical texts. (There are, in fact, a total of 308 poem titles that were reconstructed, but the remaining three poems only have titles without any extant text). The earliest surviving edition of Book of Songs is a fragmentary one of the Han Dynasty, written on bamboo strips, unearthed at Fuyang.The poems are written in four-character lines. The airs are in the style of folk songs, although the extent to which they are real folk songs or literary imitations is debated. The odes deal with matters of court and historical subjects, while the hymns blend history, myth and religious material.The three major literary figures or styles employed in the poems are fu, bi and xing:Chinese character Pinyin Meaning賦fùstraightforward narrative⽐bǐexplicit comparisons興xìng implied comparisonsAn example of a poem from the Book of Songs is as follows:Do not break our willow trees.It's not that I begrudge the willows,But I fear my father and mother.You I would embrace,But my parents' words—Those I dread.Please, Zhongzi,Do not leap over our wall,Do not break our mulberry trees.It's not that I begrudge the mulberries,But I fear my brothers.You I would embrace,But my brothers' words—Those I dread.Please, Zhongzi,Do not climb into our yard,Do not break our rosewood tree.It's not that I begrudge the rosewood,But I fear gossip.You I would embrace,But people's words—Those I dread.[edit] ContentsSummary of groupings of Book of Songs poems[edit] Guo FengGuo Feng (simplified Chinese: 国风; traditional Chinese: 國⾵; pinyin: Guófēng) "Airs of the States" poems 001-160; 160 total folk songs (or airs)group char group name poem #s01 周南Odes of Zhou & South 001-01102 召南Odes of Shao & South 012-02503 邶⾵Odes of Bei 026-04404 鄘⾵Odes of Yong 045-05405 衛⾵Odes of Wei 055-06408 ⿑⾵Odes of Qi 096-10609 魏⾵Odes of Wei 107-11310 唐⾵Odes of Tang 114-12511 秦⾵Odes of Qin 126-13512 陳⾵Odes of Chen 136-14513 檜⾵Odes of Kuai 146-14914 曹⾵Odes of Cao 150-15315 豳⾵Odes of Bin 154-160[edit] Xiao YaXiao Ya (Chinese: ⼩雅; pinyin: xiǎoyǎ)"Minor Odes of the Kingdom" poems 161-234; 74 total minor festal songs (or odes) for court group char group name poem #s01 ⿅鳴之什Decade of Lu Ming 161-17002 ⽩華之什Decade of Baihua 170-17503 彤⼸之什Decade of Tong Gong 175-18504 祈⽗之什Decade of Qi Fu 185-19505 ⼩旻之什Decade of Xiao Min 195-20506 北⼭之什Decade of Bei Shan 205-21507 桑扈之什Decade of Sang Hu 215-22508 都⼈⼠之什Decade of Du Ren Shi 225-234[edit] Da YaDa Ya (Chinese: ⼤雅; pinyin: dàyǎ)"Major Odes of the Kingdom" poems 235-265;31 total major festal songs (Chinese: 湮捇) for solemn court ceremoniesgroup char group name poem #s01 ⽂王之什Decade of Wen Wang 235-24402 ⽣民之什Decade of Sheng Min 245-25403 蕩之什Decade of Dang 255-265[edit] SongSong (simplified Chinese: 颂; traditional Chinese: 頌; pinyin: sòng)"Odes of the Temple & Altar" poems 266-305;40 total praises, hymns, or eulogies sung at spirit sacrificesgroup char group name poem #s 01 周頌Sacrificial Odes of Zhou1 266-29601a -清廟之什Decade of Qing Miao 266-27502 魯頌Praise Odes of Lu3 297-30003 商頌Sacrificial Odes of Shang1 301-305note: alternative divisions may be topical or chronological (Legges): Song, DaYa, XiaoYa, GuoFeng [edit] Trivia Shijingcun (诗经村乡) in Xian County, Hebei, China is named after the Classic of Poetry.[edit] TranslationsThis article contains Chinese text. Without properrendering support, you may see question marks,boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinesecharacters.Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article:詩經Wikisource has original text related to this article:Classic of PoetryThe Book of Odes, in The Sacred Books of China, translated by James Legge, 1879.The Book of Songs, translated by Arthur Waley, edited with additional translations by Joseph R.Allen, New York: Grove Press, 1996.Book of Poetry, translated by Xu Yuanchong (許淵沖), edited by Jiang Shengzhang (姜勝章), Hunan, China: Hunan chubanshe, 1993.The Classic Anthology Defined by Confucius, translated by Ezra Pound, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1954. The Book of Odes, translated by Bernhard Karlgren, Stockholm: The Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, 1950. [edit] See alsoGuan ju (The first ode of Guo Feng, Zhou Nan)[edit] Notes1.^ Ebrey 1993, pp. 11-132.^ de Bary 1960, p. 33.^ Ebrey 1993, pp. 11-134.^ Ebrey 1993, pp. 11-135.^ de Bary 1960, p. 3[edit] Referencesde Bary, William Theodore, Wing-Tsit Chan, Burton Watson, Yi-Pao Mei, Leon Hurvitz, T'ung-Tsu Ch'u and John Meskill (1960). Sources of Chinese Tradition: Volume I. ColumbiaUniversity Press.Ebrey, Patricia (1993). Chinese Civilisation: A Sourcebook Second Edition. The Free Press.[edit] External linksShiijing with Mao prefaces and Zhu Xi commentary by Harrison HuangLegge's translation of the Book of Songs at the Internet Sacred Text Archive.【概要】这是⼀⾸恋曲,表达对⼥⼦的爱慕,并渴望永结伴侣。

《诗经·秦风·无衣》诗经翻译赏析《诗经·秦风·无衣》诗经翻译赏析《诗经·秦风·无衣》是《诗经》中最为著名的战争诗篇,它产生于民风骁勇剽悍的秦地,据传是秦人相应周王室号召,抗击西戎入侵者的军中战歌,表现出了秦人英勇无畏的尚武精神。

下面是店铺整理的《诗经·秦风·无衣》诗经翻译赏析,欢迎大家阅读学习。

《诗经·秦风·无衣》诗经翻译赏析篇1[译文] 怎么能说没有衣服呢?我的斗篷就可以与你共用啊![出典] 春秋《诗经·秦风·无衣》和《诗经·唐风·无衣》岂曰无衣?与子同袍。

王于兴师,修我戈矛。

与子同仇!岂曰无衣?与子同泽。

王于兴师,修我矛戟。

与子偕作!岂曰无衣?与子同裳。

王于兴师,修我甲兵。

与子偕行!《诗经·唐风·无衣》岂曰无衣?七兮。

不如子之衣,安且吉兮?岂曰无衣?六兮。

不如子之衣,安且燠兮?注释:秦风袍:长衣。

行军者日以当衣,夜以当被。

就是今之披风,或名斗篷。

“同袍”是友爱之辞。

于:语助词,犹“曰”或“聿”。

兴师:出兵。

秦国常和西戎交兵。

秦穆公伐戎,开地千里。

当时戎族是周的敌人,和戎人打仗也就是为周王征伐,秦国伐戎必然打起“王命”的旗号。

戈、矛:都是长柄的兵器,戈平头而旁有枝,矛头尖锐。

仇:《吴越春秋》引作“讐”。

“讐”与“仇”同义。

与子同仇:等于说你的讐敌就是我的讐敌。

泽:同“襗”内衣,指今之汗衫。

戟:兵器名。

古戟形似戈,具横直两锋。

作:起。

裳:(cháng)下衣,此指战裙。

唐风七:七章之衣,诸侯的服饰;虚数,言衣之多也。

子:此指制衣人。

安:舒适。

吉:美,善。

六:音路,六节衣。

燠:音“玉”,暖热。

译文1:秦风谁说没有衣裳?和你穿同样的战袍。

君王要起兵,修整好戈和矛,和你同仇敌忾!谁说没有衣裳?和你穿同样的内衣。

君王要起兵,修整好矛和戟,和你共同作准备!谁说没有衣裳?和你穿同样的战裙。

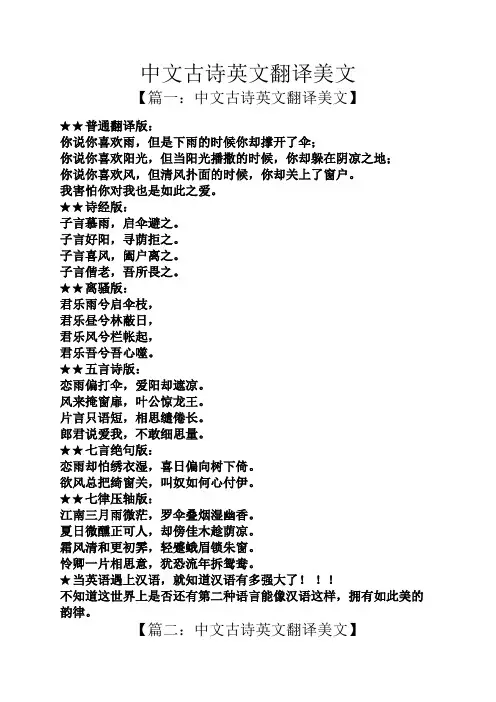

中文古诗英文翻译美文【篇一:中文古诗英文翻译美文】★★普通翻译版:你说你喜欢雨,但是下雨的时候你却撑开了伞;你说你喜欢阳光,但当阳光播撒的时候,你却躲在阴凉之地;你说你喜欢风,但清风扑面的时候,你却关上了窗户。

我害怕你对我也是如此之爱。

★★诗经版:子言慕雨,启伞避之。

子言好阳,寻荫拒之。

子言喜风,阖户离之。

子言偕老,吾所畏之。

★★离骚版:君乐雨兮启伞枝,君乐昼兮林蔽日,君乐风兮栏帐起,君乐吾兮吾心噬。

★★五言诗版:恋雨偏打伞,爱阳却遮凉。

风来掩窗扉,叶公惊龙王。

片言只语短,相思缱倦长。

郎君说爱我,不敢细思量。

★★七言绝句版:恋雨却怕绣衣湿,喜日偏向树下倚。

欲风总把绮窗关,叫奴如何心付伊。

★★七律压轴版:江南三月雨微茫,罗伞叠烟湿幽香。

夏日微醺正可人,却傍佳木趁荫凉。

霜风清和更初霁,轻蹙蛾眉锁朱窗。

怜卿一片相思意,犹恐流年拆鸳鸯。

★当英语遇上汉语,就知道汉语有多强大了!!!不知道这世界上是否还有第二种语言能像汉语这样,拥有如此美的韵律。

【篇二:中文古诗英文翻译美文】美文赏析中还需要学会放弃我属于不擅长说“不”的那类人,一次揽太多活儿,花太多时间做自己原本不想做的事情。

我常对自己说:“好吧,既然已经在这些事情上花费了太多时间,那就一直做下去。

”而有一天,我的一位朋友对我说:“在我读一本书读到第500页时发现不喜欢它,我没有接着读完,而是把它扔在一边,这时我才发现自己真正成熟了。

”……i m one of those people who s terrible at saying no. i take on too many projects at once, and spend too much of my time doing things i d rather not be. i get stuff done, but it s not always the best i can do, or the best way i can spend my time. that s why my newest goal, both as a professional and a person, is to be a quitter.being a quitter isn t being someone who gives up, who doesn t see important things through to the end. i aspire to be the opposite of those things, and think we all should. the quitter i want to be is someone who gets out when there s no value to be added, or when that value comes at the expense of something more important.i want to quit doing things that i m asked to do, for no other reason than i m asked to do it. i want to be able to quit something in mid-stream, because i realize there’s nothing good coming from it.a friend of mine once told me that i knew i was an adult when i could stop reading a book, even after getting 500 pages into it. odd though it sounds, we all tend to do this. we get involved in something, realize we don t want to be a part of it, but keep trucking through. we say well, i ve already invested so much time in this, i might as well stick it out.i propose the opposite: quit as often as possible, regardless of project status or time invested. if you re reading a book, and don t like it, stop reading. cut your losses, realize that the smartest thing to do is stop before your losses grow even more, and quit. if you re working on a project at work that isn t going anywhere, but you ve already invested tons of time on it, quit. take the time gained by quitting the pointless project, and put it toward something of value. instead of reading an entire book you hate, read 1/2 a bad one and 1/2 a good one. isn t that a better use of your time?if you re stuck doing something, and don t really want to do it anymore, step back for a second. ask if you really have to do this, and what value is being produced from your doing it. don t think about the time you ve put into it, or how much it s taken over your life. if you don t want to do it, and don t have to do it, don t do it.by quitting these things, you ll free up time to do things that actually do create value, for yourself and for others. you ll have time to read all the great books out there, or at least a couple more. you’ll be able to begin to put your time and effort i nto the things you d actually like to do.let s try it together: what are the things you re doing, that you re only doing because you ve been doing them for so long? quit. don t let time spent dictate time you will spend. let s learn how to say no at the beginning, or in the middle, and free up more of our time to do the things we’d like to be doing, and the things actually worth doing.saying no is hard, and admitting a mistaken yes is even harder. but if we do both, we ll start to make sure that we re spending our time creating value, rather than aggravating our losses. let s be quitters together.what do you think? what in your life can you quit?美文欣赏:你可以选择自己想过的生活occasionally, life can be undeniably, impossibly difficult. we are faced with challenges and events that can seem overwhelming, life-destroying to the point where it may be hard to decide whether to keep going. but you always have a choice. jessica heslop shares her powerful, inspiring journey from the worst times in her life to the new life she has created for herself:in 2012 i had the worst year of my life.2012年是我生活中最艰难的一年。

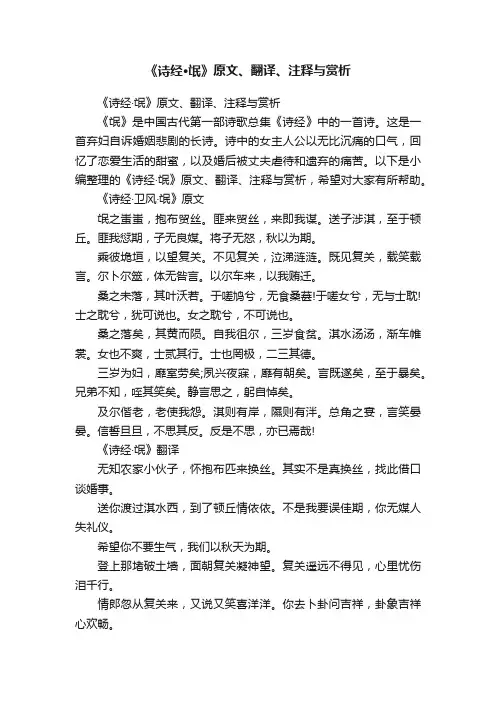

《诗经·氓》原文、翻译、注释与赏析《诗经·氓》原文、翻译、注释与赏析《氓》是中国古代第一部诗歌总集《诗经》中的一首诗。

这是一首弃妇自诉婚姻悲剧的长诗。

诗中的女主人公以无比沉痛的口气,回忆了恋爱生活的甜蜜,以及婚后被丈夫虐待和遗弃的痛苦。

以下是小编整理的《诗经·氓》原文、翻译、注释与赏析,希望对大家有所帮助。

《诗经·卫风·氓》原文氓之蚩蚩,抱布贸丝。

匪来贸丝,来即我谋。

送子涉淇,至于顿丘。

匪我愆期,子无良媒。

将子无怒,秋以为期。

乘彼垝垣,以望复关。

不见复关,泣涕涟涟。

既见复关,载笑载言。

尔卜尔筮,体无咎言。

以尔车来,以我贿迁。

桑之未落,其叶沃若。

于嗟鸠兮,无食桑葚!于嗟女兮,无与士耽!士之耽兮,犹可说也。

女之耽兮,不可说也。

桑之落矣,其黄而陨。

自我徂尔,三岁食贫。

淇水汤汤,渐车帷裳。

女也不爽,士贰其行。

士也罔极,二三其德。

三岁为妇,靡室劳矣;夙兴夜寐,靡有朝矣。

言既遂矣,至于暴矣。

兄弟不知,咥其笑矣。

静言思之,躬自悼矣。

及尔偕老,老使我怨。

淇则有岸,隰则有泮。

总角之宴,言笑晏晏。

信誓旦旦,不思其反。

反是不思,亦已焉哉!《诗经·氓》翻译无知农家小伙子,怀抱布匹来换丝。

其实不是真换丝,找此借口谈婚事。

送你渡过淇水西,到了顿丘情依依。

不是我要误佳期,你无媒人失礼仪。

希望你不要生气,我们以秋天为期。

登上那堵破土墙,面朝复关凝神望。

复关遥远不得见,心里忧伤泪千行。

情郎忽从复关来,又说又笑喜洋洋。

你去卜卦问吉祥,卦象吉祥心欢畅。

赶着你的车子来,把我财礼往上装。

桑树叶子未落时,挂满枝头绿萋萋。

唉呀那些斑鸠呀,别把桑叶急着吃。

唉呀年轻姑娘们,别对男人情太痴。

男人要是迷恋你,要说放弃也容易。

女子若是恋男子,要想解脱不好离。

桑树叶子落下了,又枯又黄任飘零。

自从嫁到你家来,三年挨饿受清贫。

淇水滔滔送我归,车帷溅湿水淋淋。

我做妻子没差错,是你奸刁缺德行。

做人标准你全无,三心二意耍花招。

About the electronic versionShi Jing [Book of Odes]AnonymousCreation of machine-readable version: Xuepen Sun and Xiaoqian Zheng, University of Virginia Chinese Text InitiativeCreation of digital images:Conversion to TEI.2-conformant markup: Xuepen Sun and Xiaoqian Zheng, University of Virginia Chinese Text InitiativeUniversity of Virginia LibraryCharlottesville, VirginiaChinese, AnoShihPublicly-accessibleURL: /chinese1998Chinese Text InitiativeChinese characters which were not available in the Chinese word processor (NJStar) were substituted with synonymous characters.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------About the print versionShi Ji ZhuanZhu XiZhong Hua Xue Yi SheShanghai1936Print copy consulted: in UVa Makiam collectionThe English translation text was taken from The Chinese Classics, vol. 4 by James Legge (1898) and checked against a reprinted edition by Wen Zhi Zhe chu pan she (Taiwan, 1971). Transliteration of Chinese names in the English translation were converted to PinYin from Legge's own.Prepared for the University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center.The images exist as archived TIFF images, one or more JPEG versions for general use, and thumbnail GIFs.Some keywords in the header are a local Electronic Text Center scheme to aid in establishing analytical groupings.English Chinese--------------------------------------------------------------------------------Revisions to the electronic versionAugust 1998corrector Christine Ruotolo, Electronic Text Center Created TEI header; parsed text and fixed tagging errors.etextcenter@ . Commercial use prohibited; all usage governed by our Conditions of Use: /conditions.html--------------------------------------------------------------------------------詩集傳序或有問予曰、詩何為而作也。

《诗经唐风绸缪》古诗赏析及翻译

今夕何夕,见此良人。

[译文]今夜究竟是怎样的一个晚上啊?我竟能与心上人相会。

[出自]春秋《诗经·唐风·绸缪》

绸缪束薪,三星在天。

今夕何夕,见此良人。

子兮子兮,如此良人何!

绸缪束刍,三星在隅。

今夕何夕,见此邂逅。

子兮子兮,如此邂逅何!

绸缪束楚,三星在户。

今夕何夕,见此粲者。

子兮子兮,如此粲者何!注释:

绸缪:音仇谋,缠绕,捆束

束薪:捆住的柴草,喻婚姻爱情。

有人考证,《诗经》中的“薪”都

比喻婚姻:“三百篇言取妻者,皆以析薪取兴。

盖古者嫁娶以燎炬为烛”。

(魏源《诗古微》此用捆束柴草,比喻婚姻缠绵不解。

三星:即参星,是由三颗星组成。

良人:古代妇女称丈夫。

刍:柴草。

隅:东南边。

参星黄昏时在东方天上,此时到东南,已至深夜。

邂逅:遇合。

此用作名词,代指遇合的人。

楚:荆条。

粲者:美人。

诗经卷耳原文,全文赏析,翻译注释采采卷耳,不盈顷筐。

嗟我怀人,寘彼周行。

陟彼崔嵬,我马虺隤。

我姑酌彼金,维以不永怀。

陟彼高冈,我马玄黄。

我姑酌彼兕觥,维以不永伤。

陟彼矣,我马矣。

我仆⒁矣,云何吁矣!注释①采采:采了又采。

卷耳:野菜名,又叫苍耳。

②盈:满。

顷筐:浅而容易装满的竹筐。

③嗟:叹息。

怀:想,想念。

④真加宝盖(zhi):放置。

周行(hang):大道。

⑤陟(zhi):登上。

崔嵬(wei):山势高低不平。

⑥虺阝贵(hui tui):疲乏而生病。

⑦ 姑:姑且。

金儡(lei):青铜酒杯。

⑧维:语气助词,无实义。

永怀:长久思念。

⑨玄黄:马因病而改变颜色。

⑩兕觥(si gong):犀牛角做成的酒杯。

⑾永伤:长久思念。

⑿咀(ju):有土的石山。

⒀者加病头凸(tu):马疲劳而生病。

⒁甫加病头(pu):人生病而不能走路。

⒂云:语气助词,没有实义。

何:多么。

吁(xu):忧愁。

译文采了又采卷耳菜,采来采去不满筐。

叹息想念远行人,竹筐放在大路旁。

登上高高的石山,我的马儿已困倦。

我且斟满铜酒杯,让我不再长思念。

登上高高的山冈,我的马儿步踉跄。

我且斟满牛角杯,但愿从此不忧伤。

登上高高山头呦,我的马儿难行呦。

我的仆人病倒呦,多么令人忧愁呦。

赏析征夫怨妇,是中国古代生活方式中的独特景观,也是中国古代诗歌的独特景观。

正如西方文学中崇尚个人奋斗的英雄一样,中国古代诗人十分关注由男女有别、男女分工而造成的男女不同的内心情怀。

男子汉不能无所作为,总得要做点什么,才会对得起祖先、子孙。

孔子所说的“三不朽”(立功、立德、立言),是专对男人说的。

立功既可以在庄稼地里、仕途上,也可以在疆场上。

长期在外征战的汉子,被称为“征夫”。

按人之常情,他们有刚强勇猛无所畏惧的一面,也有儿女情长英雄气短的一面。

照传统的观点,女子无才便是德。

女人虽然主内,但女人缠绵悱恻的情意却足以感动诗人和刚毅的汉子。

在那种嫁鸡随鸡、嫁狗随狗的年代,一个出嫁为人妻的女子,全部的希望和情感的依托,都在夫君身上。

诗经带翻译和赏析Title: Appreciation and Translation of Selected Poems from the Book of Songs。

The Book of Songs, also known as the Classic of Poetry, is a collection of ancient Chinese poems that dates back to the Western Zhou dynasty (1046-771 BC). It contains a total of 305 poems that were sung by common people in various occasions, such as festivals, weddings, funerals, and hunting trips. The Book of Songs is not only a literary masterpiece but also a valuable source of historical and cultural information about ancient China.In this article, we will select and analyze four representative poems from the Book of Songs, providing both the original Chinese text and English translation, as well as some insights into their cultural significance and artistic features.1. 《关雎》(Guān Jū) "A Song of Parting"关关雎鸠,在河之洲。