欧洲联盟基本权利宪章

- 格式:doc

- 大小:132.00 KB

- 文档页数:24

《欧洲联盟运行条件》114条适用条件概述欧洲联盟(E ur op ean U ni on,简称E U)是由28个成员国组成的政治经济联盟。

为了确保联盟的顺利运行,欧盟设立了一系列的运行条件。

本文将介绍《欧洲联盟运行条件》中的114条适用条件,旨在帮助读者更好地了解欧盟的工作原则和运行机制。

第一章宪法框架与基本法律1.第一部分:欧洲联盟宪法的制定和修改2.第二部分:欧盟基本法律的法律地位-2.1欧盟基本法律的构成要素-2.2欧盟基本法律的修正程序-2.3欧盟基本法律的适用和效力第二章政治机构与决策机制1.欧洲理事会的角色和职能2.欧洲理事会主席的选举和任期3.欧洲委员会的组成和职责4.欧洲议会的议员选举制度5.欧洲议会的议事规则和决策程序6.欧盟法院的司法管辖权和法官任命第三章经济政策与市场规则1.欧洲联盟的共同市场原则-1.1欧盟成员国的商品自由流通-1.2欧盟成员国的劳动力自由流动-1.3欧盟成员国的资本自由流动2.欧盟的经济政策协调机制-2.1欧盟成员国的财政政策协调-2.2欧盟成员国的货币政策协调-2.3欧盟成员国的经济结构政策协调3.欧盟的竞争政策和反垄断规定4.欧盟与非成员国的贸易关系第四章社会政策与人权保障1.欧盟的劳动力和社会保护政策-1.1欧洲劳工权益保护法-1.2欧洲社会福利制度2.欧盟的环境保护政策-2.1欧盟对气候变化的应对措施-2.2欧盟对环境污染的防治措施3.欧盟成员国的公民权利和人权保护-3.1欧洲人权公约的适用范围-3.2欧盟成员国公民的自由权利保护第五章外交与安全政策1.欧盟的共同外交与安全政策原则2.欧盟与成员国之间的外交协调机制3.欧盟对外援助政策和国际合作机制4.欧盟的联合国事务和国际安全事务参与5.欧盟对非洲、亚洲和拉美国家的政策第六章适用条件的执行和违约责任1.欧盟成员国对欧盟法规的执行2.欧盟成员国的违约责任和处罚机制3.欧盟委员会的违约调查和裁决程序结论本文对《欧洲联盟运行条件》中的114条适用条件进行了详细介绍,涵盖了欧盟的宪法框架与基本法律、政治机构与决策机制、经济政策与市场规则、社会政策与人权保障、外交与安全政策以及适用条件的执行和违约责任等方面。

欧盟法律体系概述欧盟(European Union)是由28个成员国组成的政治经济联盟,具有独立的法律体系。

欧盟法律体系的建立旨在保护成员国和欧盟公民的权益,确保欧洲内部市场的正常运作,并加强欧洲在国际事务中的影响力。

本文将对欧盟法律体系的组成以及其运作方式进行概述。

一、基本原则欧盟法律体系的基础是欧洲联盟条约(Treaties of the European Union),它规定了成员国的权利和义务,以及欧盟的机构和决策程序。

在条约的基础上,制定了大量的欧盟法律法规,这些法律法规是成员国必须遵守的。

欧盟法律体系的基本原则包括:1. 优先权原则:欧盟法律在成员国法律之上,成员国的国内法律必须与欧盟法律保持一致。

2. 直接效力原则:欧盟法律直接适用于成员国,成员国的法院必须执行欧盟法律。

3. 合作原则:欧盟法律的制定需要成员国之间的协商和合作,确保法律的民主性和多元性。

4. 逐步集中原则:欧盟法律的领域和范围在不断扩大,成员国需要逐步将主权移交给欧盟。

二、法律制定机构欧盟法律体系的法律制定机构包括欧洲委员会(European Commission)、欧洲议会(European Parliament)和欧洲理事会(Council of the European Union)。

欧洲委员会是欧盟的执行机构,负责制定欧盟法律的提案,并监督欧盟法律的实施。

欧洲委员会由28名委员组成,每个成员国派出一名委员。

欧洲议会是欧盟的立法机构,代表着欧洲公民的权益。

欧洲议会的议员由欧洲各成员国选举产生,根据议员人数的多少确定每个国家的代表席位。

欧洲理事会是由成员国政府的代表组成的机构,负责协商欧盟的法律制定和决策。

欧洲理事会的主席由成员国轮流担任,任期半年。

三、法律的适用和执行欧盟法律的适用范围覆盖了欧盟的所有成员国。

成员国的法院必须根据欧洲法院的判决,执行欧盟法律。

欧洲法院是欧盟法律体系的最高司法机构,负责解释规范欧盟法律的含义和适用范围。

32新视点·法治足迹里斯本条约(Tratado de Lisboa),又称改革条约,因2007年12月13日签署于葡萄牙里斯本而得名。

它是欧盟用以取代《欧盟宪法条约》的条约,已于2009年12月1日正式生效。

《里斯本条约》为欧盟的各项改革奠定了坚实的基础,加快了欧盟政治经济一体化的进程,具有里程碑的意义。

源于欧盟制宪危机1991年12月11日,在马斯特里赫特会议上,欧共体首脑们签署了《欧洲联盟条约》,确立了建立欧洲经济货币联盟和欧洲政治联盟的目标。

1993年11月1日,条约生效,自此,欧共体发展成欧洲联盟。

尽管改变了名称,成员国数量有所增加,但是现行的决策机制和机构还是为过去6国共同体“量体定作”的,已经难以保证大欧盟的有效运转,不适应欧盟向更高层次一体化的发展。

另外,据统计,当时欧盟的各类条约和法律、法规已达10万页之多,不仅庞杂,且不系统、不完备。

欧盟的发展亟待一部系统、完整的宪法出台。

于是,2001年12月5日,欧盟在比利时莱肯欧盟首脑会议的《莱肯宣言》中决定开始制定宪法,并决定成立一个制宪筹备委员会。

2003年6月13日,欧盟制宪筹备委员会的105名成员经过近16个月的激烈讨论,终于就欧盟第一部宪法条约草案达成一致。

被誉为“欧洲宪法之父”的筹委会主席、法国前总统吉斯卡尔·德斯坦说,这部草案是理想主义和现实主义的结合,是“超出人们预期”的成果。

2004年6月18日,欧盟25个成员国在比利时首都布鲁塞尔举行首脑会议,一致通过了《欧盟宪法条约》草案的最终文本。

同年10月29日,欧盟及其25个成员国领导人在意大利首都罗马正式签署了条约。

按照规定,《欧盟宪法条约》将于2006年11月1日正式生效,但必须经所有成员国根据本国法律批准,如果遭到任何一个成员国否决,条约都不能生效。

成员国批准该条约可采取两种方式:议会表决和全民公决。

其中,采取全民公决的方式,条约不被批准的风险要比议会表决的方式大得多。

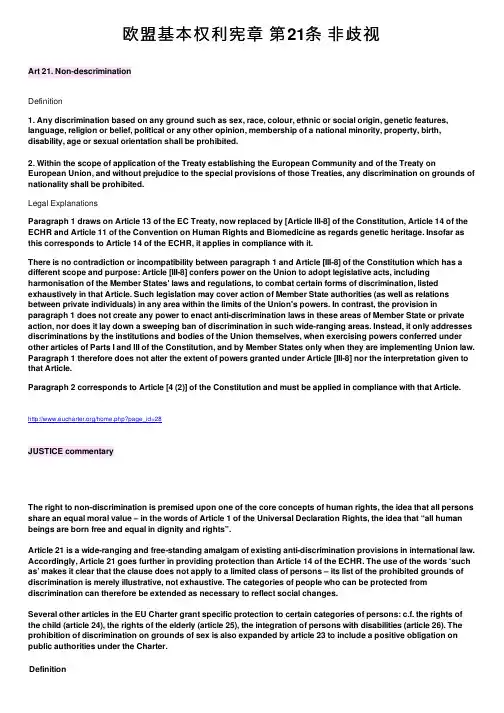

欧盟基本权利宪章第21条⾮歧视Art 21. Non-descriminationDefinition1. Any discrimination based on any ground such as sex, race, colour, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, birth, disability, age or sexual orientation shall be prohibited.2. Within the scope of application of the Treaty establishing the European Community and of the Treaty on European Union, and without prejudice to the special provisions of those Treaties, any discrimination on grounds of nationality shall be prohibited.Legal ExplanationsParagraph 1 draws on Article 13 of the EC Treaty, now replaced by [Article III-8] of the Constitution, Article 14 of the ECHR and Article 11 of the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine as regards genetic heritage. Insofar as this corresponds to Article 14 of the ECHR, it applies in compliance with it.There is no contradiction or incompatibility between paragraph 1 and Article [III-8] of the Constitution which has a different scope and purpose: Article [III-8] confers power on the Union to adopt legislative acts, including harmonisation of the Member States' laws and regulations, to combat certain forms of discrimination, listed exhaustively in that Article. Such legislation may cover action of Member State authorities (as well as relations between private individuals) in any area within the limits of the Union's powers. In contrast, the provision in paragraph 1 does not create any power to enact anti-discrimination laws in these areas of Member State or private action, nor does it lay down a sweeping ban of discrimination in such wide-ranging areas. Instead, it only addresses discriminations by the institutions and bodies of the Union themselves, when exercising powers conferred under other articles of Parts I and III of the Constitution, and by Member States only when they are implementing Union law. Paragraph 1 therefore does not alter the extent of powers granted under Article [III-8] nor the interpretation given to that Article.Paragraph 2 corresponds to Article [4 (2)] of the Constitution and must be applied in compliance with that Article. /home.php?page_id=28JUSTICE commentaryThe right to non-discrimination is premised upon one of the core concepts of human rights, the idea that all persons share an equal moral value – in the words of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration Rights, the idea that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”.Article 21 is a wide-ranging and free-standing amalgam of existing anti-discrimination provisions in international law. Accordingly, Article 21 goes further in providing protection than Article 14 of the ECHR. The use of the words ‘such as’ makes it clear that the clause does not apply to a limited class of persons – its list of the prohibited grounds of discrimination is merely illustrative, not exhaustive. The categories of people who can be protected from discrimination can therefore be extended as necessary to reflect social changes.Several other articles in the EU Charter grant specific protection to certain categories of persons: c.f. the rights of the child (article 24), the rights of the elderly (article 25), the integration of persons with disabilities (article 26). The prohibition of discrimination on grounds of sex is also expanded by article 23 to include a positive obligation on public authorities under the Charter.Definition‘Discrimination’ occurs where a person is subjected to arbitrary or unfair treatment on the basis of some group-based distinction such as sex, ethnicity, age, etc. As noted in the discussion of Article 20, direct discrimination occurs where a law singles out a particular social group (or groups) for unfair differential treatment (see ‘suspect groups’ below). Indirect discrimination occurs where the law is not necessarily targeted at a particular group, but nonetheless has the unjustified effect of unfairly burdening or penalizing the members of that group. At the same time, mere differential treatment is not itself prohibited. Rather, the prohibition against discrimination is meant as a check against unjustified and arbitrary treatment.Differential treatmentThe first step to determining where discrimination has taken place is to establish whether differential treatment has occurred – whether individuals who are similarly situated have been treated differently.[1] Of course, not every difference in treatment is necessarily discriminatory. The essential question is whether a ‘reasonable and objective justification’ can be shown for the difference in treatment in each case.[2] Such a justification depends upon:1. showing that the measure has a ‘rational aim’; and2. showing that there is a proportionate relationship between that aim and the specific measure employed.[3] These concepts will be explained in more detail below. Nonetheless, the first step for a person bringing a claim of discrimination against the state is for that person to show they have been subject to differential treatment. Once this has been shown, then the burden will be upon the state to show that the difference in treatment was nonetheless justified.Justification for differential treatmentThe first step for a state wishing to justify differential treatment on the basis of group-based characteristics is to show a ‘rational aim’ for the treatment. In practical terms, this is not an especially onerous requirement. This is because the courts are typically unwilling to gainsay the rationality of policies adopted by democratically-elected officials unless it is so plainly arbitrary as to be impossible to justify.However, establishing the ‘rational aim’ behind the contested legislation or decision is only the first part of the enquiry. What is required is also that the differences in treatment between members of different groups can be shown to ‘strike a fair balance between the protection of the interests of the community and respect for the rights and freedoms’.Suspect GroupsThe idea of a ‘suspect group’ means that any kind of differential treatment according to distinctions such as sex,[4] race,[5] nationality,[6] illegitimacy,[7]and religion[8] will automatically raise suspicion of unlawful discrimination unless the state is able to show extremely strong grounds justifying the distinction. This is because these are categories upon which arbitary discrimination has historically been associated and accordingly the law should be very slow to permit differential treatment on these grounds.Margin of AppreciationAn important principle that the courts will have regard to in determining whether differential treatment is justified is the ‘margin of appreciation’. The margin of appreciation doctrine has broader application than just the right to non-discrimination, but has been particularly important in this context. In general, it refers to the idea that states enjoy a degree of latitude or discretion as to how they give effect to Convention rights in certain areas and that international courts should be slow to interfere with the decisions of national governments in certain areas. Traditionally, one area where the doctrine of the margin of appreciation has been recognized has been in national security, but it also has relevance for some aspects of anti-discrimination law, such as regulating incitement to violence or racist speech.[9] However, the idea that standards of human rights protection may differ according to the decisions of national governments remains a controversial one.[10]Indirect DiscriminationIndirect discrimination is discrimination that results from a rule or practice that in itself does not require differential treatment but which disproportionately and adversely affects members of a particular group. For instance, instances of indirect discrimination include:- a job requirement that employees must be clean-shaven (practising Sikh men would be unable to comply without breaching religious requirements);- operating a work environment that is not accessible to disabled persons;- subjecting part-time workers to less favourable treatment than full-time workers (in an employment context where the overwhelming proportion of part-time workers are women but where the overwhelming proportion of full-time workers are men);[11]- restricting employment to nationals or citizens, where this would have the effect of excluding ethnic minorities from competing for jobs.[12]It is not necessary in such cases to show any discriminatory intent on behalf of the state, the employer or service provider, etc. Rather, where the implementation of an apparently uniform condition can be shown to have a disproportionate and negative impact on members of a particular group, then the court must consider whether there is ‘an objective balance between the discriminatory effect of the condition and the reasonable needs of the party who applies the condition.[13]Positive Discrimination‘Positive discrimination’ is the term used to describe programmes designed to favour or promote the interests of disadvantaged groups. The aim of redressing a pre-existing situation of inequality has been accepted as a legitimate objective of differential treatment, although it is still subject to careful scrutiny.Not all instances of differential treatment are discriminatory, particularly where the differential treatment is intended to correct existing inequality.[14] For instance, a tax advantage which encourages married women back towork[15]was held not considered to be discriminatory. However, states are not under any obligation to undertake measures of positive discrimination.[1]Fredin v Sweden, 18 February 1991[2] Belgian Linguistic v Belgium, 23 July 1968, A94 para 85; Rasmussen v Denmark, 28 November 1984;[3] Ibid. Rasmussen v Denmark, 28 November 1984[4] Abdulaziz, Cabales and Balkandali v United Kingdom, 28 May 1985[5] Ibid; East African Asian v UK, 15 December 1973.[6] Gaygusuz v Austria, 16 September 1996[7] Inze v Austria, 28 October 1987[8] Hoffmann v Austria, 23 June 1993[9] Eyal Benvenisti, “Margin of Appreciation, Consensus, and Universal Standards i”, International Law and Politics [Vol. 31:843], 1999, 845.[10] See Z v Finland, 25 February 1997; Judge De Meyer in a partly dissenting opinion was very critical of the doctrine. He pointed out “… it is high time for the Court to banish that concept from its reasoning … where human rights are concerned, there is no room for the State to decide what is acceptable and what is not…On that subject the boundary not to be overstepped must be as clear as possible”.[11] C-285/02, Edeltraud Elsner-Lakeberg v Land Nordrhein-Westfalen, 16 October 2003, para 11.[12] C-224/02, Heikki Antero Pusa v Osuuspankkien Keskinäinen Vakuutusyhtiö, 20 November 2003, para 17.[13] John Bowers QC and Elena Moran, “Justification in Direct Sex Discrimination Law: Breaking the Taboo”, Industrial Law Journal [Vol 31], December 2002, 312.[14] Belgian Linguistic v Belgium, 23 July 1968, para 10[15] Lindsay v UK, 11 November 1986,/home.php?page_id=96。

欧盟公民制度欧盟公民制度是指欧洲联盟成员国公民在欧盟内享有的一系列权利和义务。

这一制度的建立旨在加强欧盟成员国之间的联系和合作,促进欧洲一体化进程的发展。

首先,欧盟公民制度确保了欧盟成员国公民的基本权利。

根据欧盟公民权利宪章,欧盟公民享有言论自由、宗教自由、人身自由等基本权利。

这些权利的保障使得欧盟成员国公民能够在欧盟内自由地居住、工作和学习,享受平等待遇。

此外,欧盟公民还有权利参与欧洲议会选举和地方选举,以及提起诉讼和申请救济。

其次,欧盟公民制度促进了欧洲内部的经济和社会发展。

欧盟成员国公民可以在欧盟内自由流动,这为他们提供了更多的就业和发展机会。

欧盟公民可以在欧盟内的任何成员国工作和生活,享受与当地公民相同的待遇。

这种自由流动的制度有助于促进欧洲内部的经济一体化,提高欧洲的竞争力。

此外,欧盟公民制度还鼓励欧洲成员国之间的文化交流和合作,促进了欧洲社会的多元化和融合。

然而,欧盟公民制度也面临一些挑战和争议。

首先,欧盟公民制度的实施需要各成员国之间的合作和协调。

不同成员国之间的法律和制度差异可能导致公民权利的不平等。

此外,欧盟公民制度也面临着移民和难民问题的挑战。

欧盟成员国之间的边界开放政策使得移民和难民涌入欧洲,给一些国家的社会和经济带来了压力。

这些问题需要欧盟成员国共同努力,寻找合适的解决方案。

为了进一步完善欧盟公民制度,欧盟成员国需要加强合作,加强对公民权利的保护和促进。

欧盟可以通过加强法律和制度的协调,确保欧盟公民在不同成员国之间享有平等的权利和待遇。

此外,欧盟还可以加强对移民和难民问题的管理,制定更加公正和可持续的政策,以减少社会和经济的不平等。

总之,欧盟公民制度是欧洲一体化进程中的重要组成部分。

它为欧盟成员国公民提供了基本权利和机会,促进了欧洲内部的经济和社会发展。

然而,欧盟公民制度也面临一些挑战和争议,需要欧盟成员国共同努力,寻找合适的解决方案。

只有通过加强合作和协调,欧盟公民制度才能更好地为欧洲公民服务,推动欧洲一体化进程的发展。

欧洲的人权保障与法治建设近年来,欧洲各国在人权保障与法治建设方面取得了令人瞩目的成就。

作为一个高度发达和文明的大陆,欧洲国家秉持着保护人权的核心理念,努力构建公正、平等、法治的社会秩序,为世界其他地区树立了良好的榜样。

一、欧洲人权保障的法律框架欧洲的人权保障体系建立在一系列国际和地区法律框架之上。

首先,我们不能忽视的是欧洲人权公约(European Convention on Human Rights,ECHR)。

该公约于1950年签署,自1953年起生效,并成为欧洲人权保护的基石。

与此同时,欧盟也通过了《欧洲联盟基本权利宪章》(Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union),确保欧洲公民在各个领域享有基本权利和自由。

二、欧洲的反歧视立法和实践欧洲一直是反歧视工作的领导者之一。

欧洲各国通过立法禁止各类歧视行为,并在实践中努力维护社会公正和平等。

其中最具代表性的是英国的《平等法案》(Equality Act)和法国的“宪法原则法”(Constitutional Principles Act),这些法律明确规定了歧视行为的禁止和违法后果。

三、欧洲的司法独立与公正欧洲国家注重司法独立和司法公正,为人权保障和法治建设提供了有力保障。

法官在审判过程中独立行使权力,不受政治或经济压力的干扰。

此外,欧洲各国也建立了完善的司法制度,确保判决公正、透明,维护了人权的平等和尊严。

四、欧洲的言论自由与媒体监督人权保障的重要方面之一是言论自由。

欧洲国家长期以来致力于保护公民的言论自由权利,允许人们自由表达观点和意见。

并且,欧洲各国还建立了相应的监督机制,监管媒体行为,保证媒体报道客观、公正,不引导公众舆论。

五、欧洲的人权教育和意识提升欧洲国家注重人权教育与意识提升,通过教育系统推广人权知识,加强公民参与,培养人权意识。

人权博物馆、人权教育中心等机构在欧洲如雨后春笋般涌现,提供了更多的机会,让公众了解、尊重和捍卫自己和他人的人权。

欧盟法与欧洲法律体系了解欧洲法律的基本原则和规范欧盟法与欧洲法律体系:了解欧洲法律的基本原则和规范在了解欧洲法律的基本原则和规范之前,我们首先需要了解欧盟法和欧洲法律体系的概念及其关系。

欧盟法是指欧洲联盟(European Union, EU)制定的法律,是欧洲法律体系的一个组成部分。

欧洲法律体系则是指欧洲国家和地区的法律体系的总称,包括了欧盟法以及各个成员国的国内法。

在本文中,我们将探究欧盟法与欧洲法律体系的关系,并介绍欧洲法律的基本原则和规范。

一、欧盟法与欧洲法律体系的关系欧盟法是欧洲法律体系的一个重要组成部分,但并不代表全部。

欧洲法律体系包括了多个国家的法律,涵盖了不同的法律传统和文化背景。

欧盟法在欧洲法律体系中有着独特的地位,它是由欧洲联盟机构制定的,适用于所有成员国,并具有直接适用性和优先适用性。

欧盟法对成员国的国内法有着重要的影响,成员国的国内法必须与欧盟法保持一致。

欧盟法的主要特点是具有超国家性和一体化的特征。

它的目标是推动欧洲内部一体化和统一市场的建设,确保成员国之间的经济、政治和法律上的合作与协调。

欧盟法充分体现了欧盟成员国共同的价值观和利益,并通过各种法律行为,如指令、条例和决议等,对成员国进行约束和规范。

二、欧洲法律的基本原则欧洲法律的发展离不开一些基本原则的指导和规范。

以下是欧洲法律的基本原则之一。

1. 优先适用性原则欧盟法享有优先适用性,这意味着在欧盟法与成员国国内法之间存在冲突时,欧盟法具有更高的法律效力,成员国的国内法必须遵守欧盟法的规定。

2. 直接适用性原则欧盟法有直接适用性,这意味着欧盟法对成员国的国内法有直接约束力,成员国的法院和政府机构必须根据欧盟法的规定执行和适用。

3. 合资本市场和自由流通原则欧洲法律倡导建立统一的资本市场和自由流通的原则,以促进欧盟内部的贸易和经济合作。

成员国不能对其他成员国的商品、服务、人员和资本实施不合理的限制和歧视。

4. 人权保护原则欧洲法律体系高度重视人权保护。

欧盟的法律和治理体系欧洲联盟(European Union, EU)是由28个欧洲国家组成的政治和经济联盟。

为了实现欧盟的目标,成员国制定了一系列的法律和治理体系。

本文将介绍欧盟的法律制度、决策过程以及其对成员国的治理。

一、欧盟的法律制度欧盟的法律制度由基本法源、次级法和成员国法律构成。

欧盟的基本法源主要包括《欧洲联盟的功能条约》(Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, TFEU)、《欧洲联盟运作条约》(Treaty on European Union, TEU)以及《欧洲联盟宪章》(Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union)。

基本法源确立了欧洲联盟的机构、职能和宏观目标。

次级法是根据基本法源由欧盟机构制定的具体法规、指令和决议等。

成员国在履行欧盟职责的过程中,需要制定或修改国内法律以确保与欧盟法律的一致性。

欧盟的法律制度具有权威性和直接适用性。

一旦欧盟法律发布,它就具有优先性并可直接在所有成员国适用。

二、欧盟的决策过程欧盟的决策过程涉及各个机构之间的合作与互动。

欧洲联盟理事会(European Council)是欧盟的最高决策机构,由各成员国的元首或政府首脑组成。

欧洲委员会(European Commission)是欧盟的行政执行机构,负责起草法律和政策建议,并执行已通过的法律。

欧洲议会(European Parliament)则是欧盟的立法机构。

在决策过程中,欧洲委员会提出法律和政策建议,并提交给欧洲议会和理事会。

欧洲议会与理事会通过立法程序对其进行审议和修改。

一旦议会和理事会就法律或政策达成共识,该法律或政策就会生效。

需要注意的是,欧盟的决策过程通常需要在不同的机构之间进行谈判和协商,以确保各成员国的权益得到平衡和尊重。

三、欧盟对成员国的治理欧盟的治理是通过欧洲委员会、理事会和欧洲议会这些机构进行的。

欧洲的人权与社会正义欧洲作为一个先进的大陆,一直以来都非常注重人权和社会正义的推进与实现。

在欧洲,人权被认为是每个人的基本权利,社会正义也是构建和谐社会的核心价值。

本文将从欧洲的人权保护机构、法律制度以及社会平等和公正等方面,探讨欧洲的人权与社会正义。

一、欧洲的人权保护机构欧洲各国注重保护和促进人权的机构众多。

其中,最有代表性的是欧洲人权法院(European Court of Human Rights,简称ECHR)。

ECHR是一个独立的国际法庭,设在法国斯特拉斯堡,负责处理来自欧洲各国的人权投诉案件。

通过审理和解决跨国界的人权纠纷,ECHR提供了一个平等、公正的司法程序,维护了欧洲人权法的权威性和一致性。

另外,欧洲理事会下设的人权事务总司(Directorate General of Human Rights),是欧洲各国就人权事务开展合作和协调的重要机构。

该机构致力于推动各国人权立法和政策的发展,促进跨国界人权合作,加强各国间的对话和交流。

二、欧洲的法律制度欧洲各国都制定了一系列法律规定,以保障和维护人权。

其中,最重要的法律框架是《欧洲人权公约》(European Convention on Human Rights,简称ECHR)。

ECHR是欧洲理事会成员国必须遵守的一项国际公约,它规定了各种人权和基本自由的保障措施,并确保各国人民能够获得公平公正的司法程序。

此外,欧洲联盟也对人权的保护扮演着重要的角色。

通过《欧洲联盟宪章》和《欧盟基本权利宪章》,欧洲联盟确保了成员国在欧盟法律框架下的人权保护,并明确规定了公民的基本权利和自由。

三、社会平等和公正欧洲注重实现社会平等和社会公正,通过法律措施和社会政策,努力消除社会不平等现象,并促进社会的包容和和谐。

在劳动法方面,欧洲对劳动者权益的保护非常重视。

各国法律规定了劳动时间、工资待遇、工作条件等,保障了劳动者的权益和福利。

欧洲各国也致力于提供全民教育、医疗和社会保障等公共服务,确保每个人都能够享受到基本的权益和福利。

欧盟的宪法与法治建设权力制衡与司法独立欧洲联盟(European Union,简称EU)是一个由27个成员国组成的政治和经济联盟。

为了确保成员国之间的合作和规范,欧盟建立了一套宪法和法治体系。

本文将探讨欧盟的宪法与法治建设,以及权力制衡与司法独立在其中所起的关键作用。

一、欧盟宪法的重要性宪法被视为一个国家或组织的基本法律文件,规定了权力的行使、组织结构和公民权利等方面。

欧盟作为一个国际组织,也有自己的宪法性文件,其中最重要的是《欧洲联盟宪章》(Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union)。

欧洲联盟宪章于2000年颁布,旨在保护欧盟成员国内的公民权利和自由。

它包含了诸多基本权利,如言论自由、宗教信仰自由、平等权利、私人生活保护等。

它的颁布对于加强欧盟成员国之间的团结和公民权利的保护起到了重要作用。

二、权力制衡的重要性权力制衡是现代民主制度中重要的一个原则,意味着不同的权力机构相互制衡,以避免出现过度集中权力的情况。

欧盟中的权力制衡主要体现在三个方面:欧洲议会、欧洲委员会和欧洲理事会之间的相互制衡。

欧洲议会是由欧盟成员国选举产生的立法机构,代表欧盟公民的权益。

它对欧盟的立法过程发挥着重要的作用,能够对欧盟委员会提出指示并审查委员会的行动。

欧洲委员会是欧盟的执行机构,由各成员国提名的专员组成。

它负责制定欧盟的政策和法规,并监督成员国的执行情况。

欧洲委员会的工作受到欧洲议会的监督,避免了权力滥用的情况。

欧洲理事会由欧盟成员国的领导人组成,代表各成员国的权益。

其主要职责是制定欧盟的总体政策和指导方针。

虽然欧洲理事会的决议不具有法律约束力,但它对欧盟政策的影响力很大,并能够对欧洲委员会的任命提出建议。

三、司法独立的重要性司法独立是法治社会中的核心原则,意味着司法机构能够独立行使审判权,不受外界干预或影响。

欧盟的司法独立主要体现在欧洲法院。

欧洲法院是欧盟的最高法院,负责解释欧洲联盟法律的适用和有效性。

最新版欧盟条约学习要点

1. 欧盟条约概述

- 欧盟条约是欧盟成员国之间签订的重要法律文件,旨在建立

和维护欧盟的法律框架和政治体系。

- 欧盟条约的目标是促进成员国间的合作,加强欧洲内部市场,推动欧洲一体化进程。

2. 欧盟条约的主要内容和原则

- 欧盟条约确立了欧洲联盟的基本原则,如平等、民主、透明、多样性、和平等。

- 欧盟条约规定了欧盟机构的组成和职责,如欧洲委员会、欧

洲议会、欧洲理事会等。

- 欧盟条约还规定了欧盟成员国的权利和义务,以及各个政策

领域的管理和决策程序。

3. 欧盟条约修订和维护

- 欧盟条约可以通过修订来适应欧盟的发展和变化。

- 欧盟条约的修订需要由欧盟成员国同意并遵守一定的程序。

- 欧盟条约的维护是欧盟成员国共同的责任,需要各个成员国共同合作和遵守相应的规定。

4. 欧盟条约的影响和意义

- 欧盟条约对欧洲联盟的发展和运行起着重要的指导作用。

- 欧盟条约规定了欧洲联盟内各成员国的权利和义务,维护了欧洲内部市场的一体化。

- 欧盟条约还有助于推动欧洲联盟在国际上的地位和影响力。

5. 欧盟条约的研究要点

- 熟悉欧盟条约的基本原则和主要内容。

- 了解欧盟条约的修订和维护方式。

- 分析欧盟条约对欧洲联盟和成员国的影响和意义。

以上是最新版欧盟条约学习要点的简要介绍,希望能对您的学习和研究有所帮助。

欧洲联盟法了解欧盟成员国的法律要求欧洲联盟(简称欧盟)是一个由28个成员国组成的政治和经济联盟。

作为一个整体,欧盟制定了一系列的法律要求,以确保成员国在各个领域的合作与一致性。

欧盟法对成员国的法律体系有着直接的影响和约束。

本文将介绍欧洲联盟法以及它对欧盟成员国法律要求的影响。

一、欧洲联盟法简介欧洲联盟法是由欧盟制定和颁布的法律规范,旨在统一成员国间的立法和行政体系,建立一个统一的市场和法律框架。

欧洲联盟法包括主要法律文件如欧盟条约、欧洲联盟宪章以及欧盟法规和指令等。

欧盟法规是欧盟制定的具有普遍适用性的法律文件,直接适用于所有成员国。

而欧盟指令是欧盟制定的法律文件,要求成员国在一定期限内将其转化为国内法并执行。

欧盟法规和指令在成员国内具有同等法律效力,必须得到充分的遵守和执行。

二、欧盟成员国的法律要求欧盟成员国作为欧盟的一部分,必须遵守欧盟法规定的法律要求。

这些要求涵盖多个领域,包括经济、环境、就业、消费者保护等。

1. 经济要求欧盟法对成员国的经济政策和市场行为有着严格的规定。

成员国需要遵守欧盟的竞争法,确保市场公平竞争和自由贸易的原则得到维护。

此外,成员国还需遵守欧盟关于货币政策、财政稳定和经济合作等方面的规定,以促进欧盟内各成员国之间的经济一体化和稳定发展。

2. 环境要求欧盟致力于保护环境和推动可持续发展,因此对成员国的环境政策有着严格的要求。

成员国需要制定和执行符合欧盟标准的环境法规,其中包括减少温室气体排放、保护水资源、推动可再生能源等。

欧盟还通过制定和执行相关指令,确保成员国在环境保护方面的一致性和协调性。

3. 就业要求欧盟致力于促进就业和创造良好的劳动条件,通过欧盟法规定了成员国在就业领域的一系列法律要求。

成员国需要确保实施公平的劳动法规,保护劳动者的权益,包括工资支付、工时限制、职业安全等方面。

欧盟还制定了就业政策和指导原则,进行协调和合作,以保障成员国的就业市场的稳定性和发展。

4. 消费者保护要求欧盟重视消费者权益的保护,通过欧盟法规定了成员国在消费者保护方面的法律要求。

欧盟的人权保护与社会正义欧盟作为一个政治经济实体,其人权保护与社会正义一直是其重要的发展目标。

本文将从欧盟的人权法框架、人权保护机制以及社会正义政策三个方面探讨欧盟在这一领域的努力和成就。

一、欧盟的人权法框架欧洲联盟成立的宗旨之一就是确保欧洲所有成员国和公民享有基本的人权和自由。

欧盟的人权法框架主要包括欧洲联盟基本权利宪章和欧洲人权公约。

欧洲联盟基本权利宪章于2000年通过,是欧洲联盟的第一个具有约束力的人权文件,其中囊括了包括言论自由、信仰自由、平等权利等在内的一系列基本权利。

欧洲人权公约则是欧洲人权法的核心文件,对个人权利的保护作出了具体规定。

二、欧盟的人权保护机制为了保障人权的实施和监督,欧盟建立了一套完整的人权保护机制。

其中,欧洲联盟法院、欧洲人权法院以及欧洲委员会扮演了重要的角色。

欧洲联盟法院是欧洲联盟内最高级别的司法机构,负责确保欧盟法律和其他成员国之间的法律保持一致,并保障联盟的法律准则得到遵守。

欧洲人权法院则是负责处理侵犯欧洲人权公约的申诉和决定。

而欧洲委员会则是负责监督欧洲公民权利的实施情况,同时也是一种信访机构。

三、欧盟的社会正义政策欧盟致力于通过社会正义政策来保护弱势群体的权益,促进社会公平和包容。

这一政策主要体现在教育、就业和福利三个方面。

在教育领域,欧盟通过投资教育资源来促进社会平等。

欧盟通过资助教育项目、提供奖学金等方式,鼓励各成员国提供平等的机会,确保所有人都享有受教育的权利。

在就业领域,欧盟致力于消除就业歧视,保护劳动者的权益。

欧盟通过立法措施和政策引导,推动雇主提供平等的就业机会,保障劳动者的福利和待遇。

在福利领域,欧盟倡导建立社会安全网络,保障每个人的权益。

欧盟通过设立最低工资标准、提供社会保障制度等措施,确保每个成员国公民都能享受基本的福利保障。

总结:欧盟在人权保护与社会正义方面积极努力,通过制定法律框架、建立人权保护机制以及推行社会正义政策,致力于保障每个人的基本权利和福祉。

根据最新《欧洲联盟条约》学习要点.txt根据最新《欧洲联盟条约》研究要点欧洲联盟条约是欧盟的重要法律文件,对于了解欧盟的组织结构、权力划分以及成员国之间的合作等方面至关重要。

以下是最新《欧洲联盟条约》的一些研究要点:1. 组织结构:欧洲联盟由欧洲委员会、欧洲议会、欧洲理事会、欧洲经济社会委员会、欧洲司法法院和其他机构组成。

这些机构共同负责管理和推动欧盟的事务。

组织结构:欧洲联盟由欧洲委员会、欧洲议会、欧洲理事会、欧洲经济社会委员会、欧洲司法法院和其他机构组成。

这些机构共同负责管理和推动欧盟的事务。

2. 权力分配:不同机构在欧盟事务中享有不同的权力和职责。

欧洲委员会负责提出提案和执行决策,欧洲议会代表欧洲人民的声音,欧洲理事会则由成员国领导人组成,负责制定欧盟政策的方向。

权力分配:不同机构在欧盟事务中享有不同的权力和职责。

欧洲委员会负责提出提案和执行决策,欧洲议会代表欧洲人民的声音,欧洲理事会则由成员国领导人组成,负责制定欧盟政策的方向。

3. 成员国合作:成员国在欧盟框架内合作,共同制定政策,并通过欧洲议会和欧洲理事会进行协商和决策。

成员国还负有遵守欧盟法律和执行欧盟政策的责任。

成员国合作:成员国在欧盟框架内合作,共同制定政策,并通过欧洲议会和欧洲理事会进行协商和决策。

成员国还负有遵守欧盟法律和执行欧盟政策的责任。

4. 欧洲市场:欧洲联盟致力于建立一个共同市场,促进成员国之间的货物、服务、资本和人员的自由流动。

这有助于促进经济增长和就业机会的增加。

欧洲市场:欧洲联盟致力于建立一个共同市场,促进成员国之间的货物、服务、资本和人员的自由流动。

这有助于促进经济增长和就业机会的增加。

5. 欧洲法院:欧洲司法法院负责解决欧盟法律事务的争议,并对欧盟法律的适用进行解释。

其裁决对成员国具有约束力。

欧洲法院:欧洲司法法院负责解决欧盟法律事务的争议,并对欧盟法律的适用进行解释。

其裁决对成员国具有约束力。

以上是根据最新《欧洲联盟条约》的一些研究要点。

欧盟机构介绍欧盟联盟(European Union,以下简称“欧盟”)的前身是由西欧12国组成的欧洲共同体。

经欧洲共同体各成员国批准,《欧洲联盟条约》(即:《马斯特里赫特条约》)于1993年11月1日正式生效。

欧洲联盟现在成员国15个,即法国、德国、意大利、英国、荷兰、比利时、卢森堡、爱尔兰、丹麦、希腊、西班牙、葡萄牙、奥地利、芬兰和瑞典。

欧盟是一个超国家的组织,既有国际组织的属性,又有某些邦联甚至联邦的特征。

欧盟的条约使其成为一个高度自主决策机构,赋予立法权限。

欧盟成员国自愿将国家部分主权转移至欧盟,欧盟在机构的组成和权利的分配上,强调每个成员国的参与,其组织体制以"共享"、"法制"、"分权和制衡"为原则。

欧共体还远不是一个国家意义上的联邦,因为至少在政治体制上欧共体各国仍以各政府协调为基础,但一些学者将其称为“超国家组织”,因为其的确具有了某些联邦的特征。

如:一系列基础条约具有共同体宪法的作用;欧共体条约创建了立法、执法机关并赋予它们各种权力;共同体条约、共同体机关的立法在各成员国有直接效力,优先于成员国法律适用;欧共体条约更创设了欧洲法院,并且赋予其解释“宪法”――欧共体条约的权力等等。

[总部所在地]比利时首都布鲁塞尔。

[组织机构]根据马约规定,欧盟理事会(European Council)在欧盟组织中占有中心地位,是欧盟成员国首脑会议,每年至少举行两次,理事会主席由各成员国每6个月轮流担任。

欧盟理事会是欧盟的最高决策机构,由各成员国国家元首或政府首脑及欧盟委员会主席组成,主要是确定欧盟的内部建设和对外关系的大政方针。

欧盟理事会秘书长兼任欧盟共同外交与安全政策高级代表,现任主席国、下任主席国和高级代表组成“三驾马车”。

按条约规定,欧盟主要机构如下:1.欧盟部长理事会(Council of Ministers)部长理事会是欧盟的日常决策机构,由成员国外长组成总务理事会,其他部长组成专门理事会,主席亦由成员国轮任,任期6个月。

CHARTER OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION欧洲联盟基本权利宪章(2000/C 364/01)PREAMBLE前言The peoples of Europe, in creating an ever closer union among them, are resolved to share a peaceful future based on common values.在创设一个前所未有的紧密联盟的过程,欧洲人民决意在共同价值上共享一和平的未来。

Conscious of its spiritual and moral heritage, the Union is founded on the indivisible, universal values of human dignity, freedom, equality and solidarity; it is based on the principles of democracy and the rule of law. It places the individual at the heart of its activities, by establishing the citizenship of the Union and by creating an area of freedom, security and justice.谅察其精神与道德上之传统,欧洲联盟乃建立在不可分离及普世价值之人性尊严、自由、平等与团结之上。

其系奠基于民主与法治原则之上。

藉由创立欧洲联盟公民并创造一自由、安全与正义之领域,欧洲联盟认为个人是其各项活动之重心。

The Union contributes to the preservation and to the development of these common values while respecting the diversity of the cultures and traditions of the peoples of Europe as well as the national identities of the Member States and the organisation of their public authorities at national, regional and local levels; it seeks to promote balanced and sustainable development and ensures free movement of persons, goods, services and capital, and the freedom of establishment.欧洲联盟对于上述共同价值之发展与保存有所贡献,但是其亦尊重欧洲人民文化与传统之多元性、各会员国国民之自我意识及国家、区域与地方层级之公权力组织;欧洲联盟欲促进平衡及永续之发展,并确保人员、货物、服务与资金之自由流动与创业自由。

To this end, it is necessary to strengthen the protection of fundamental rights in the light of changes in society, social progress and scientific and technological developments by making those rights more visible in a Charter.为达成此一目的,且衡酌社会变迁及进步与科技发展之情形,有必要以于一宪章中将彼等权利加以明示之方式,加强对基本权利之保障。

This Charter reaffirms, with due regard for the powers and tasks of the Community and the Union and the principle of subsidiarity, the rights as they result, in particular, from the constitutional traditions and international obligations common to the Member States, the Treaty on European Union, the Community Treaties, the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, the Social Charters adopted by the Community and by the Council of Europe and thecase-law of the Court of Justice of the European Communities and of the European Court of Human Rights.基于尊重欧洲共同体与欧洲联盟之权力与职掌及辅助原则之前提,本宪章再次确认这些权利,因为这些权利源自于会员国共同之宪政传统与国际义务、欧洲联盟条约、欧洲共同体各条约、欧洲保护人权与基本自由公约、欧洲共同体与欧洲理事会所通过之各社会宪章及欧洲共同体法院与欧洲人权法院之判决。

Enjoyment of these rights entails responsibilities and duties with regard to other persons, to the human community and to future generations.对于此等权利之享有,伴随着对他人、人类社会以及未来世代之责任与义务。

The Union therefore recognises the rights, freedoms and principles set out hereafter. 欧洲联盟兹此确认以下诸权利、自由与原则。

CHAPTER I (第一章)DIGNITY (尊严)Article 1 (第一条)Human dignity人性尊严Human dignity is inviolable. It must be respected and protected.人性尊严不可侵犯,其必须受尊重与保护。

Article 2 (第二条)Right to life生命权1. Everyone has the right to life.人人均享有生命权。

2. No one shall be condemned to the death penalty, or executed.不论何人均不受死刑判决或受死刑执行。

Article 3 (第三条)Right to the integrity of the person人身自主权1. Everyone has the right to respect for his or her physical and mental integrity.人人均享有尊重其心理与生理自主之权利。

2. In the fields of medicine and biology, the following must be respected in particular: 于医药与生物领域,下列事项应特别受到遵守:— the free and informed consent of the person concerned, according to the procedures laid down by law,依法律规定程序之相关人员之自由且经告知之同意;— the prohibition of eugenic practices, in particular those aiming at the selection ofpersons,禁止基因改造医疗行为,特别是针对人种选择而行之者;—the prohibition on making the human body and its parts as such a source of financial gain,禁止为营利而为人体与器官复制;— the prohibition of the reproductive cloning of human beings.禁止复制人之行为。

Article 4 (第四条)Prohibition of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment酷刑与不人道或羞辱之待遇或惩罚之禁止No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.不论何人均不得被施以酷刑或不人道或羞辱之待遇或惩罚Article 5 (第五条)Prohibition of slavery and forced labour奴隶与强制劳动之禁止1. No one shall be held in slavery or servitude.不论何人均不得被处为奴隶或奴役。

2. No one shall be required to perform forced or compulsory labour.不论何人均不得被要求施以强制或非自愿性劳动。

3. Trafficking in human beings is prohibited.禁止进行人口贩卖。

CHAPTER II (第二章)FREEDOMS (自由权)Article 6 (第六条)Right to liberty and security自由与安全之权利Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person.人人均有权享有人身自由与安全。

Article 7 (第七条)Respect for private and family life个人与家庭生活Everyone has the right to respect for his or her private and family life, home and communications.人人均有权要求尊重其私人与家庭生活、住居及通信。