2019最新4923平法图集讲座2优质文档英语

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:4.43 MB

- 文档页数:51

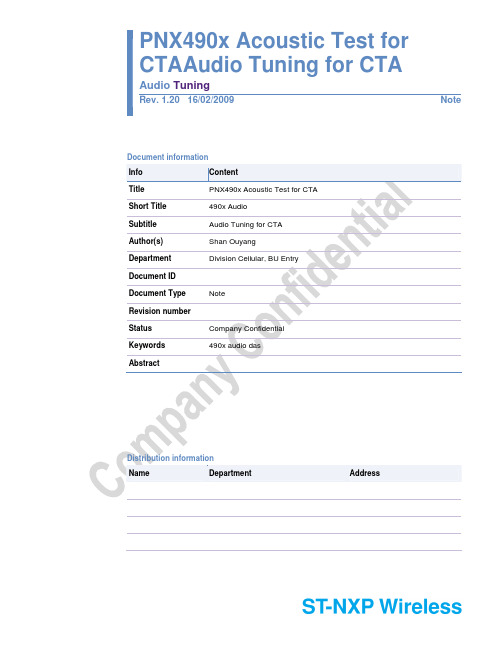

PNX490x Acoustic Test for CTAAudio Tuning for CTAAudio TuningRev. 1.20 16/02/2009NoteDocument informationInfo ContentTitle PNX490x Acoustic Test for CTAShort Title 490x AudioSubtitle Audio Tuning for CTAAuthor(s) Shan OuyangDepartment Division Cellular, BU EntryDocument IDDocument Type NoteRevision numberStatus Company ConfidentialKeywords 490x audio dasAbstractDistribution informationName Department AddressST-NXP wireless490x AudioAudio TuningContact informationFor additional information, please visit: Revision history Rev Date Description 1.0 20090216 Creation1. Content1.Content (3)2.Abbreviations (4)3.References (4)4.Introduction (5)5.Introduction of Audio Test in China TypeApproval (5)5.1Specifications (5)5.2Test items of CTA (5)6.Hardware and Software requirements (6)6.1Test Setup (6)6.2List of Equipment (6)6.3Audio Tuning Tools (7)7.Audio Tuning Procedures (7)7.1Tuning of Receive Frequency Response(RFR) (9)7.2Tuning of Receive Loudness Rating (RLR) (11)7.3Tuning of Send Frequency Response(SFR) (12)7.4Tuning of Send Loudness Rating (SLR) (13)7.5Tuning of Sidetone Masking Rate (STMR)14 7.6Tuning of Sending Distortion (15)7.7Tuning of Receive Distortion (17)7.8Tuning of Idle Channel Noise Receiving (18)7.9Tuning of Idle Channel Noise Sending (18)7.10Tuning of Acoustic Echo Control (AEC) (19)8.Legal information (19)8.1Disclaimers (19)2. AbbreviationsAcronym DescriptionAudioMon PC software used to adjust the audio subsystem. Version 2.44 and aboveshould be used with 4902.PGA Programmable Gain AmplifierCODEC Basically COder DECoder but used in the document as “DAC+ADC”LRGP Loudness Rating Guardring PositionERP Ear Reference PointMRP Mouth Reference Point3. References[1] Hw_UM_PNX490x_Audio_Mon_User_Manual_p23958.pdf : AudioMon user manual[2] Hw_ApplicationNote_PNX4902_Audio_Subsystem_p28595 : Audio structures and performance presentation[3] YD/T 1538-2006, Technical Requirements and Testing Methods for Acoustics Performance of Digital Mobile Terminal[4] 3GPP TS26.131, TS26.1324. IntroductionThis document helps readers understand audio test and gives guidelines how to tune the audio parameters of platform to pass audio tests of China Type Approval.5. Introduction of Audio Test in China Type ApprovalAll the mobile terminals sold in China market need to pass China type approval (CTA). The main test authority named CTTL (China Telecommunication Technology Labs) which Located in Beijing.5.1 SpecificationsThe Chinese national standard YD/T1538-2006 is followed by CTA. It has the same requirements with other international specifications which are:FTA: 3GPP TS 51.0103GPP TS 26.131 & TS 26.132ITU-T: P.51, P.57, P.58, P.64, P.67...5.2 Test items of CTACurrently seven items need to be tested in CTA and six of them must pass the test.Sending Frequency Response (SFR)Sending Loudness Rating (SLR)Receiving Frequency Response (RFR)Receiving Loudness Rating (RLR) nom volReceiving Loudness Rating (RLR) max volSide tone Masking Rating (STMR)Distortion SendingAlso following additional items were required by CTTL from Jan.1 2009.Distortion ReceivingEcho Loss (EL)Idle Channel Noise Receiving nomIdle Channel Noise Receiving maxIdle Channel Noise SendingStability MarginNote 3GPP TSTest name Requirement26.131CTA 5.4.1 Sending frequency response (Template)CTA 5.2.2 Sending loudness rating (SLR) 5...11 dBCTA 5.4.2 Receiving frequency response (Template)CTA 5.2.2 Nom. Receiving loudness rating (RLR) -1...5 dBCTA 5.2.2 Max. Receiving loudness rating (RLR) ≥ -13 dBCTA 5.5.1 Side Tone Masking Rating (STMR) 15...23 dBNew 5.7.1 Acoustic Echo Control ≥ 46 dBNew 5.6 Stability Loss (Nooscillation)CTA 5.8.1 Distortion – Sending (Template)New 5.8.2 Distortion – Receiving (Template)New 5.3.1 Idle noise – Sending -64dBNew 5.3.2 Idle noise – Receiving (Nominal) -57 dBNew 5.3.2 Idle noise – Receiving (Maximum) -54 dB6. Hardware and Software requirements6.1 Test SetupThe audio test can be conducted via DAI interface or air interface. Nowadays air interface is more popular and is used in CTA. Below is the typical test setup:6.2 List of EquipmentBelow are equipments using in STN Shanghai.Rhode & Schwarz UPV. (CTA is using ACQUR from Head Acoustic)Rhode & Schwarz CMU 200Artificial EarArtificial Ear ITU type 1: B&K Type 4185Artificial Ear ITU type 3.2: B&K Type 4195Artificial Mouth. B&K Type 4227Telephone Test Head: B&K Type 4602BSound level calibrator B&K Type 4231Microphone power-supply: B&K 2690A0S2The terminal under test, artificial mouth and ear should be put together into an acoustic chamber.6.3 Audio Tuning ToolsAll the audio parameters of terminal are stored in flash memory. A PC tool TAT (Test and Auto Test) is used to read, edit, import and export the audio parameters.AudioMon is another PC tool which is used to modify audio parameters on the fly. Detailed user guide please refer to reference.7. Audio Tuning ProceduresChosen settings of the audio parameters are stored in audio data section of flash memory. It is normallynecessary to have different settings of the audio parameters for different audio accessories connected to the mobile terminal (for example normal usage using the internal microphone and earphone, portable headset, loudspeaker, Bluetooth® headset, and so on). Hence, normally one pair of dedicated data sections called DSPTxOrgan[x] & DSPRxOrgan[x] should be prepared for each audio accessory used.Since FTA/CTA only test headset mode which only DSPTxOrgan[0] (main mic) and DSPRxOrgan[0] (main speaker) is involved, the following descriptions are all refer to DSPOrgan[0].Before first audio tuning, the default audio parameters has been stored in the mobile terminal with original delivery.After mounting the terminal in test set and a call was established between terminal and CMU200, audio tuning can be start. It is recommended that the tuning executed in the following common order:31.2.3. After tuning parameters, reread all parameters from terminal RAM into other active memo.4. Save the active memo to a file which will contain new parameters.5. Use TAT to import new parameters into terminal flash memory.Before continuing with the actual tuning it is recommended that the reader gets familiar with related 3GPP specifications, R&S equipments operation and NXP testing tools.TIP:During audio test, MS signal power level of CMU200 should be set as PCL 12 in GSM900.7.1 Tuning of Receive Frequency Response (RFR)This section describes how to tune frequency response in the audio receive path.7.1.1 DescriptionThe input frequency response is specified as the transmission ratio in dB of the sound pressure in the artificial ear to the input voltage at the voice coder input of CMU200.The mobile under test is installed in the LRGP position (ITU-T P.76) and the speaker is sealed to the artificial ear.The voice coder is driven so that tones with an internal reference level of -16 dBm0 are obtained. The noisepressure in the artificial ear is measured and evaluated.If type 1 artificial ear is used, The receiving frequency response must be within the limit lines specified in table30.2 of 3GPP TS51.010. The absolute sensitivity is not yet taken into account.Frequency (Hz) Upper Limit (dB) Lower Limit (dB)100 -12 -200 0 -300 2 -7500 - -51000 0 -53000 2 -53400 2 -104000 2 -Note 1: All sensitivity values are expressed in dB on a coordinate axis.Note 2: The limit of “-” lies on a straight line drawn between the breaking points on alogarithmic (frequency)/linear (dB sensitivity) coordinate.Limit lines according to 3GPP TS51.010 table 30.2If type 3.2 artificial ear is used, The receiving frequency response must be within the limit lines specified in table2 of 3GPP TS26.131.Frequency (Hz) Upper Limit (dB) Lower Limit (dB)70 -10 -200 2 -300 - -9500 - -1000 - -73000 - -3400 - -124000 2 -Note 1: All sensitivity values are expressed in dB on a coordinate axis.Note 2: The limit of “-” lies on a straight line drawn between the breaking points on a logarithmic(frequency)/linear (dB sensitivity) coordinate.Limit lines according to 3GPP TS26.131 table 2The offset of the measured frequency response to the upper or lower limit curve is calculated and then the total curve is shifted by the mean value of the maximum and minimum offset. Then another limit check is performed.If the shifted curve is within the limit lines, PASS is output, otherwise FAIL is output. The limit check isperformed at each measured frequency. If the measured value and the end point of a limit curve are not at the same frequency, it may happen that the trace slightly crosses a corner of the limit trace although there are no limit violations.7.1.2 Procedure1. Turn off Downlink FIR&IIR filters in AudioMonDSP config section.2. Measure RFR and save curve to a file. Usethe PC which running AudioMon to open the data file and copy the curve data to clipart. The data format is like below: 100 1.36016106 1.98170455736302 112 2.45548160024953…3550 4.3738710304971 3750 -1.80146960957754 4000 -14.517183. Open filter design wizard of AudioMon. ① Flat both FIR and IIR filters. ② Paste measured spectrum ③ Select limit mask as TS26.131 ④ Press FIR auto correct⑤ If FIR auto calculation is ok then press OKbutton. FIR coefficients will be present in Filter section of AudioMon. Also some fine tuning may be implemented manually. ⑥ If FIR auto calculation is not ok then may needadjust IIR filters manually to compensate the lower spectrum first. ⑦ Repeat step 4 to 6 till the compensatedspectrum in limit mask.4. Turn on Downlink FIR&IIR filters in AudioMonDSP Config section. Enable DL filter coefficients and send them to target.5. Measure the frequency response again. Theactually measured spectrum may not same as calculated by AudioMon. If the frequency response is still fail, manually trim filters at some frequency points by using filter wizard.7.2 Tuning of Receive Loudness Rating (RLR)This section describes how to tune loudness rating in the audio receive path.7.2.1 DescriptionThe receiving loudness rating (RLR) takes into account the absolute loudness in the receive direction and weights the tones in compliance with the normal sensitivity of the average human ear. The RLR is calculated at frequency bands 4 to 17 according to Table 1 of ITU-T P.79. 200250315400500630 800 1000 1250 1600 2000 2500 3150 4000The RLR depends on the receive loudness set on the ME under test and according to 3GPP TS 26.131, should be between -1 dB and +5 dB at a rated loudness setting, with lower decibel values corresponding to greater loudness (-1 dB = maximum loudness, +5 dB = minimum loudness).7.2.2 ProcedureRLR should be tuned after RFR.1. Make sure volume is set as normal. MeasureRFR.2. In case the measured RLR does not fall within thespecified limits (RLR = 2±3 dB). There are two programmable gains in receive path can be used to compensate it. If the measured RLR is less than -1dB, gains should be reduced. If themeasured RLR is higher than 5dB, gains should be increased.① DSP gain may involve digital distortion whichmay cause receive distortion failed in high sound pressure. It’s better to keep DSP DL gain no higher than 6dB. ② FIR filter gain also can be used adjust thewhole spectrum loudness. If the measured RLR is not far away thespecified limits. Tune the frequency response to change the weight of tones also can reach the target. But the RFR must keep in the mask.DSP DL GainFIR filter gain3. It’s better to trim RLR within 3~4dB which is incompliance with requirement and benefits to idle channel noise and echo loss test cases.7.3 Tuning of Send Frequency Response (SFR)This section describes how to tune frequency response in the audio send path.7.3.1 DescriptionThe send frequency response is specified as the transmission ratio in decibel of the voltage at the decoder output to the input noise pressure at the artificial mouth.The mobile terminal under test should be installed in the LRGP according to ITU-T P.76 and the speaker must be sealed to the artificial ear.Tones with a sound pressure of -4.7 dBPa are created with an artificial mouth at the Mouth Reference Point (MRP), and the corresponding output voltage is measured at the instrument voice coder (for example, CMU) output and evaluated.The send frequency response must be within the tolerance mask specified according to below table. The maskis drawn with straight lines between the breaking points in the table on a logarithmic (frequency)/linear (dBSensitivity) coordinate. Test results shall be within the mask.Frequency (Hz) Upper Limit Lower Limit100 -12 -200 0 -300 0 -121000 0 -62000 4 -63000 4 -63400 4 -94000 0 -Note 1: All sensitivity values are expressed in dB on a coordinate axis.Note 2: The limit of “-” lies on a straight line drawn between the breaking points on a logarithmic(frequency)/linear (dB sensitivity) coordinate.7.3.2 ProcedurePlease refer to section 7.1.2 (RFR tuning procedure). The difference is the tuning is in audio uplink path.7.4 Tuning of Send Loudness Rating (SLR)This section describes how to tune loudness rating in the audio send path.7.4.1 DescriptionThe send loudness rating (SLR) takes into account the absolute loudness in the transmit direction and weights the tones in compliance with the normal sensitivity of the human ear.The SLR is calculated at frequency bands 4 to 17 according to Table 1 of ITU-T P.79.According to 3GPP TS26.131 the send loudness rating should be between 5 dB and 11 dB, with lower decibel-values corresponding to greater loudness (5 dB = maximum loudness, 11 dB = minimum loudness).7.4.2 ProcedureThe main procedure can refer to section 7.2.2 (RLR tuning procedure) but there are some differences.Except DSP UL gain and UL FIR gain, a two stage PGA is in analog part. Too high gain of analog PGA may cause MIC saturated or involve much noise in uplink path.A noise suppress function in DSP is recommended to turn on which benefits to idle channel noise performance.But this function will reduce sending loudness significantly. It has to be compensated by increase digital gains.Details of noise suppressor please have a look at reference.7.5 Tuning of Sidetone Masking Rate (STMR)This section describes how to tune the sidetone masking rating (STMR).7.5.1 DescriptionThe so-called sidetone path is the desired output from the part of the signal picked up by the microphone from the phone's speaker. We need sidetone because if we cannot hear ourselves during a call, our brain refuses to accept that anyone else can hear us and we tend to speak too loudly.The artificial mouth generates tones with a sound pressure of -4.7 dBPa at the MRP, and the sound pressure is measured in the artificial ear.When the mobile terminal is set to the rated receiving loudness, the STMR should be between 18±5 dBaccording to 3GPP TS 26.131.TIP:According to the old spec (TS 51.010), STMR requirement has been 13±5 dB. Please note this has been modified in new spec which applies in CTA.A high level of sidetone has a significant effect on the use of the mobile terminal in high ambient noiseconditions, making received speech extremely difficult to recognize.Sidetone is related to SLR and RLR. Any attempt to change them to achieve compliance with loudness rating requirements can also have a marked effect on sidetone performance.7.5.2 Procedure1. Active sidetone in audio path of AudioMon CodecConfig section.2. Measure STMR in UPV, adjust sidetone gain inAudioMon Codec Misc section till the measuredSTMR is between 13~23dB.7.6 Tuning of Sending DistortionThis section describes how to tune sending distortion.7.6.1 DescriptionThe S/N ratio in the transmit path is measured as a function of the sound level.A sine-wave signal with a frequency in the range of 1004Hz to 1025Hz shall be applied in the test. The level ofthis signal at the MRP shall be adjusted until the output of the terminal is -10dBm0. The level of the signal at the MRP is then the ARL.The ratio of the signal to total distortion power (SINAD value) of the received signal is measured at the CMU’s decoder output. The SINAD value is measured at sound pressures between -35 dB and +10dB relative to the acoustic reference level ARL and compared with the limit lines specified in table as belowLevel Relative to ARL Sending Level Ratio (dB)-35 17.5-30 22.5-20 30.7-10 33.30 33.7+7 31.7+10 25.5Limits for intermediate levels are found by drawing straight lines between the breaking points in the table on a linear (dB signal level)/linear (dB ratio) coordinate.7.6.2 ProcedureMeasure the sending distortion in UPV. According to the result, there are there scenarios to be analyzedrespectively.1. The curve failed in high sound pressure part. The distortion mainly caused by signal distortiondue to too high amplifier gain in uplink path. Reduce a certain PGA gain can resolve this problem.2. The curve failed in low sound pressure part and the failure is very significant (normally around20dB to the limit). This can be concluded the test signal is removed by uplink noise suppressor inDSP. Tune noise suppressor parameters can resolve this problem.3. The curve failed in low sound pressure part and the failure is slight. The reason is very complex. Mainlycaused by noise in MIC circuit. Optimize MIC circuit or replace MIC itself is helpful.Also it is worth to retrim sending frequency response. The main part of MIC noise is in lower frequency (217Hz and the harmonics) and the test signal is around 1K Hz. Thus, reduce lower frequency weight and increase 1KHz weight in spectrum can improve the S/N rate. Below are some examples:7.7 Tuning of Receive DistortionThis section describes how to tune receive distortion.7.7.1 DescriptionFor handset terminal, headset terminal, handheld hands-free terminal and Desktop-operated hands-freeterminal, when RLR is equal to the nominal value, receiving distortion shall be measured between MRP and the input port of the reference speed coder/decoder of the SS.The ratio of signal-to-total distortion power measured with the proper noise weighting (see Table 4 of ITU-T Recommendation G.223) shall be above the limits given in below table. For sound pressures ≥+10dBPa at the ERP there is no requirement on distortion.Receiving Level at Digital Interface of the TestedReceiving Level Ratio (dB)Apparatus (dBm0)-45 17.5-40 22.5-30 30.5-20 33.0-10 33.5-3 31.20 25.5Limits for intermediate levels are found by drawing straight lines between the breaking points on a linear (dB signal level)/linear (dB ratio) coordinate.7.7.2 ProcedureThe tuning method is very similar with tuning sending distortion. Please refer to section 7.6.2.The lower sound pressure part failure may caused by improper setting of Noise Gate.The high sound pressure part failure may caused by two high PGA gain setting especially the DSP DL gain.7.8 Tuning of Idle Channel Noise ReceivingThis section describes how to tune the idle channel noise receiving.7.8.1 DescriptionThe sound pressure in the artificial ear is measured with the mobile terminal set up in a quiet environment (<30 dB(A)).The sound pressure in the artificial ear is measured with A-weighting on.With optimum volume set on the mobile, the sound pressure should not exceed -57 dBPa(A).At maximum volume, the sound pressure should not exceed -54 dBPa(A).This measurement makes high demands on the sound insulation of the test chamber and the S/N ratio of the measuring microphone including preamplifier in the artificial ear. The artificial ear is observed sensitive withTDD noise. Please make sure the mobile power level is PCL12 and keep the cable of artificial ear as short as possible exposing in RF.7.8.2 ProcedureWith proper RLR, RFR and noise gate settings, normally no more tuning needed for this test case.If audio parameter modification still can not make the test pass, add two serial 10 Ohm resistors in receiver path should be considered.7.9 Tuning of Idle Channel Noise SendingThis section describes how to tune the idle channel noise sending.7.9.1 DescriptionThe noise voltage at the voice decoder output is measured with the mobile terminal set up in a quietenvironment (< 30 dB(A)).The decoder output voltage is measured, psophometrically weighted according to ITU-T G.223 and calculated at the internal level in dBm0p.The idle noise level should not exceed -64 dBm0p.7.9.2 ProcedureWith proper SLR, SFR and noise suppressor settings, normally no more tuning needed for this test case.7.10 Tuning of Acoustic Echo Control (AEC)This section describes how to tune the acoustic echo control. It has been said Echo Loss (EL) in 3GPP TS51.010.7.10.1 DescriptionThe AEC is the attenuation between the voice coder input and the voice decoder output. Normally the echocaused by internal acoustic coupling between the mobile phone receiver and the microphone. Since the echo considerably reduces the sound transmission quality, it should not exceed a certain value. 3GPP TS26.131specifies an echo loss of at least 46 dB.To obtain realistic results, an artificial voice is used for the echo loss test. Before the actual test, a trainingsequence consisting of 10s artificial voice (male) and 10s artificial voice (female) according to ITU-TRecommendation P.50 shall be applied.7.10.2 ProcedureEcho loss is measured on maximum volume.With default acoustic template, the echo canceller and echo suppressor are active. EL test case should be no problem to pass. But if the terminal under test has problems in mechanic design, there is not a full isolationbetween MIC and receiver within the mechanic for example, EL will fail. In this case, the best solution is tooptimize mechanic. But if change mechanic is impossible, reduce the RLR in maximum volume, increaseattenuation of ES are also considered.8. Legal information8.1 DisclaimersGeneral _Information in this document is believed to be accurate and reliable. However, ST-NXP wireless does not give any representations or warranties,expressed or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of such information and shall have no liability for the consequences of use of such information.Right to make changes _ ST-NXP wireless reserves the right to make changes to information published in this document, including without limitationspecifications and product descriptions, at any time and without notice. This document supersedes and replaces all information supplied prior to the publication hereof.Suitability for use _ ST-NXP wireless Semiconductors products are not designed, authorized or warranted to be suitable for use in medical, military, aircraft, space or life support equipment, nor in applications where failure or malfunction of a NXP Semiconductors product can reasonably be expected to result inpersonal injury, death or severe property or environmental damage. ST-NXP wireless accepts no liability for inclusion and/or use of ST-NXP wireless products in such equipment or applications and therefore such inclusion and/or use is at the customer’s own risk.Applications _ Applications that are described herein for any of these products are for illustrative purposes only. ST-NXP wireless makes no representation or warranty that such applications will be suitable for the specified use without further testing or modification.ST-NXP wireless 490x AudioAudio TuningNotesHwAN_PNX4902_Audio_Subsystem © NXP Semiconductors 2007. All rights reserved. Application note Rev. 1.2— 27/11/0821 of 21。

BIS Quarterly ReviewJune 2008 International banking and financial market developmentsBIS Quarterly ReviewMonetary and Economic DepartmentEditorial Committee:Claudio Borio Frank Packer Paul Van den BerghWhite Már Gudmundsson Eli Remolona William Robert McCauley Philip TurnerGeneral queries concerning this commentary should be addressed to Frank Packer(tel +41 61 280 8449, e-mail: frank.packer@), queries concerning specific parts to theauthors, whose details appear at the head of each section, and queries concerning the statisticsto Philippe Mesny (tel +41 61 280 8425, e-mail: philippe.mesny@).Requests for copies of publications, or for additions/changes to the mailing list, should be sent to:Bank for International SettlementsPress & CommunicationsCH-4002 Basel, SwitzerlandE-mail: publications@Fax: +41 61 280 9100 and +41 61 280 8100This publication is available on the BIS website ().©Bank for International Settlements 2008. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is cited.ISSN 1683-0121 (print)ISSN 1683-013X (online)BIS Quarterly ReviewJune 2008International banking and financial market developmentsOverview : a cautious return of risk tolerance (1)Credit market turmoil gives way to fragile recovery (1)Box: Estimating valuation losses on subprime MBS with theABX HE index – some potential pitfalls (6)Bond yields recover as markets stabilise (8)A turning point for equity prices? (11)Emerging market investors discount growth risks (12)Tensions in interbank markets remain high (13)Highlights of international banking and financial market activity (17)The international banking market (17)The international debt securities market (23)Derivatives markets (24)Box: An update on local currency debt securities marketsin emerging market economies (28)Special featuresInternational banking activity amidst the turmoil (31)Patrick McGuire and Goetz von PeterThe build-up of international bank balance sheets (32)Developments in the second half of 2007 (36)Bilateral exposures of national banking systems (39)Concluding remarks (42)Managing international reserves: how does diversification affect financial costs? 45 Srichander RamaswamyFramework of the analysis (46)Risk-return trade-offs (48)Financial cost of acquiring reserves through FX intervention (49)Box: Methodology for computing estimates of financial cost (51)Central bank objectives and FX reserve allocation (53)Conclusions (54)Credit derivatives and structured credit: the nascent markets of Asiaand the Pacific (57)Eli M Remolona and Ilhyock ShimCredit default swaps (58)Traded CDS indices (60)Collaterised debt obligations (61)How the region’s markets have fared in the global turmoil (63)Conclusion (65)Asian banks and the international interbank market (67)Robert N McCauley and Jens ZukunftAsian banks’ international interbank liquidity: where do we stand? (68)Foreign banks and the local funding gap (73)Box: The Asian financial crisis: international liquidity lessons (76)Conclusions (78)BIS Quarterly Review, June 2008 iiiRecent initiatives by Basel-based committees and groupsBasel Committee on Banking Supervision (81)Joint Forum (84)Financial Stability Forum (87)Statistical Annex ........................................................................................ A1 Special features in the BIS Quarterly Review ................................ B1 List of recent BIS publications .............................................................. B2Notations used in this Reviewe estimatedlhs, rhs left-hand scale, right-hand scalemillionbillion thousand… notavailableapplicable. not– nil0 negligible$ US dollar unless specified otherwiseDifferences in totals are due to rounding.iv BIS Quarterly Review, June 2008BIS Quarterly Review, June 20081Ingo Fender +41 61 280 8415ingo.fender@Peter Hördahl+41 61 280 8434peter.hoerdahl@Overview: a cautious return of risk toleranceFollowing deepening turmoil and rising concerns about systemic risks in the first two weeks of March, financial markets witnessed a cautious return of investor risk tolerance over the remainder of the period to end-May 2008. The process of disorderly deleveraging which had started in 2007 intensified from end-February, with asset markets becoming increasingly illiquid and valuations plunging to levels implying severe stress. However, markets subsequently rebounded in the wake of repeated central bank action and the Federal Reserve-facilitated takeover of a large US investment bank. In sharp contrast to these favourable developments, interbank money markets failed to recover, as liquidity demand remained elevated.Mid-March was a turning point for many asset classes. Amid signs of short covering, credit spreads rallied back to their mid-January values before fluctuating around these levels throughout May. Market liquidity improved, allowing for better price differentiation across instruments. The stabilisation of financial markets and the emergence of a somewhat less pessimistic economic outlook also contributed to a turnaround in equity markets. In this environment, government bond yields bottomed out and subsequently rose considerably. A reduction in the demand for safe government securities contributed to this, as did growing perceptions among investors that the impact from the financial turmoil on real economic activity might turn out to be less severe than had been anticipated. Emerging market assets, in turn, performed broadly in line with assets in the industrialised economies, as the balance of risk shifted from concerns about economic growth to those about inflation.Credit market turmoil gives way to fragile recoveryFollowing two weeks of increasingly unstable conditions in early March, credit markets were buoyed by a cautious return of risk tolerance, with spreads recovering from the very wide levels reached during the first quarter of 2008. Sentiment turned in mid-March, following repeated interventions by the Federal Reserve to improve market functioning and to help avert the collapse of a major US investment bank. As these actions alleviated earlier concerns about risks to the financial system, previously dysfunctional markets resumed trading and prices rallied across a variety of risky assets.2BIS Quarterly Review, June 2008Between end-February and end-May, the US five-year CDX high-yield index spread tightened by about 144 basis points to 573, while corresponding investment grade spreads fell by 63 basis points to 102. European and Japanese spreads broadly mirrored the performance of the major US indices, declining by between 25 and 153 basis points overall. Between 10 and 17 March, all five major indices had been pushed out to or near the widest levels seen since their inception. They then rallied back and seemed to stabilise around their mid-January values, remaining significantly above the levels prevailing before the start of the market turmoil in mid-2007 (Graph 1).business lines, tightening repo haircuts caused a number of hedge funds and other leveraged investors to unwind existing positions. As a result, concerns underlying exposures are almost entirely protected by federal guarantees, as summer of 2007 (Graph 3, right-hand panel).BIS Quarterly Review, June 20083Fears about collapsing financial markets reached a peak in the week March, triggering repeated policy actions by the US authorities. investment grade credit default swap (CDS) indices underperforming lower-quality benchmarks (Graph 4, left-hand and centre panels). Spreads were temporarily arrested when, on 11 March, the Federal Reserve announced an expansion of its securities lending activities targeting the large US dealer banks (see section on money markets and Table 1 below). European CDS indices tightened by more than 10 basis points on the news, while the two key basis points down, respectively (Graph 1). allowing it to make secured advance payments to the troubled investment These developments appeared to herald a turning point in the market, funds target down to 2.25%. Earnings announcements by major investment banks on 18 and 19 March that were better than anticipated provided further support, with investors increasingly adopting the view that various central bank initiatives aimed at reliquifying previously dysfunctional markets were gradually gaining traction. Consistent with perceptions of a considerable reduction in systemic risk, spreads, and particularly those for financial sector and other investment grade firms, tightened from the peaks reached in early March(Graph 4). Movements were partially driven by the unwinding of speculative short positions, as suggested by changes in pricing differentials across products with similar exposures, according to the ease with which such positions can be opened or closed. For example, spreads on CDS contracts referencing the major credit indices moved more strongly than those on the same indices’ constituent names (Graph 1, centre and right-hand panels). Similarly, CDS markets outperformed those for comparable cash bonds, as market participants adjusted their synthetic trades.risks (Graph 1, centre and right-hand panels). Similarly, implied volatilities from CDS index options eased into the second quarter, indicating a somewhat reduced uncertainty about shorter-run credit spread movements (Graph 3, centre and right-hand panels).losses based on ABX prices (see box). This was despite the lack of a recovery for the index series with lower original ratings, whose prices continued to4 BIS Quarterly Review, June 2008BIS Quarterly Review, June 20085suggest expectations of complete writedowns of all underlying bonds by mid-2009 (Graph 2, centre panel). At these low levels, and with none of the ABX indices having experienced any principal writedowns so far, investors appeared to be pricing in the possibility of legislation writing down mortgage principal. Against this background, issuance of private-label mortgage-backed securities remained depressed, with volume growth coming mainly from US agency-Supported by optimism about banks’ recapitalisation efforts, spreads pace of capital replenishment. Following news of a rights issue on 31 March, CDS spreads referencing debt issued by Lehman Brothers tightened. UBS announced large first quarter losses and a fully underwritten capital increase on 1 April, and other institutions followed over the rest of the month. Globally, banks managed to raise more than $100 billion of new capital in April alone, stemming the deterioration in capital ratios. Financial CDS spreads, the monoline segment excluded, outperformed corresponding equity prices in the process (Graph 4, right-hand panel), reflecting diminishing concerns about imminent financial sector risk as well as the dilutory effects of equity financing. Markets retraced some of these gains in early May, partially driven by strong supply flows from corporate issuers that included, at $9 billion, the largest US dollar deal by a non-US borrower in seven years. Volumes were dominated by6 BIS Quarterly Review, June 2008Pitfalls in using the ABX. Estimated mark to market losses and actual writedowns made by banks and other investors can differ for a variety of reasons. Analysts, depending on their objective, thus have to be mindful of potential sources of bias. At least three such sources can be identified, of which two are specific to the ABX index:•Accounting treatment. Subprime MBS are held by a variety of investors and for different purposes. While large amounts of outstanding subprime MBS are known to reside inbanks’ trading books, banks and other investors may also hold these securities tomaturity. This can result in different accounting treatments, which would tend to deflateactual writedowns and impairment charges relative to estimates of mark to market losseson the basis of market indices, such as the ABX. The size of this effect, however, isdifficult to determine. Further complexities are added once securities cease to be tradedin active markets, implying the use of valuation techniques, which may differ acrossinvestors, in establishing fair value.5•Market coverage. ABX prices may not be representative of the total subprime universe, due to limited index coverage of the overall market. Original balance across all four serieshas averaged about $31 billion. This compares to average monthly MBS issuance ofsome $36 billion over the 10 quarters up to mid-2007, ie almost a month’s worth ofsubprime MBS supply per index series. Similarly, with 2004–07 vintage subprime MBSvolumes estimated at around $600 billion in outstanding amounts, each series representssome 5% of the overall universe on average. At the same time, ABX deal composition isknown to be quite similar in terms of collateral attributes (such as FICO scores and loan-to-value ratios) to the overall market (by vintage).6 Therefore, despite somewhat limitedcoverage, this particular source of bias may not be large.•Deal-level coverage. Similarly, ABX prices may not be representative because each index series covers only part of the capital structure of the 20 deals included in the index(see Graph A, right-hand panel, for an illustration).7 In particular, tranches referenced bythe AAA indices are not the most senior pieces in the capital structure, but those with thelongest duration (expected average life) – the so-called “last cash flow bonds”. Theseclaims will receive any cash flow allocations sequentially after all other AAA trancheshave been paid; and tend to switch to pro rata pay only when the highest mezzaninebond has been written down. It follows that AAA ABX index prices are going to reflectdurations that are longer, and effective subordinations that are lower, than those of theremaining AAA subprime MBS universe. As a result, using newly available data for MBStranches with shorter durations, the $119 billion of losses implied by the ABX AAA indicesas of end-May would be some 62% larger than those implied under more realisticassumptions.8_________________________________1 See, for example, International Monetary Fund, Global Financial Stability Report, April 2008, pp 46–52, and Box 1 in Bank of England, Financial Stability Report, April 2008.2 Supplementary indices, called ABX HE PENAAA, were introduced in May 2008 to provide additional pricing information for all four existing vintages.3 An alternative approach, likely to lead to very different results, would estimate future default-related cash flow shortfalls on the basis of deal-level or aggregate data for subprime securities. To obtain these estimates, such methodologies rely on information about collateral performance and require the analyst to make assumptions about structural relationships and model parameters. Typical subprime loss projections, for example, use delinquency data and assumptions about factors such as delinquency-to-default transitions, default timing, and losses-given-default. See Box 1 in the Overview section of the December 2007 BIS Quarterly Review for an example on the basis of an approach devised by UBS. 4Mark to market losses (relative to par) are calculated assuming that unrated tranches are written down completely; ABX prices for the BBB– indices are used to mark BB collateral; rated tranches from the 2004 vintage are assumed unimpaired; outstanding amounts remain static.5 For details, see Global Public Policy Committee, Determining fair value of financial instruments under IFRS in current market conditions, December 2007.6 See, for example, UBS, Mortgage Strategist, 17 October 2006. 7 Incomplete coverage at the deal level further reduces effective market coverage: typical subprime MBS structures have some 15 tranches per deal, of which only five were originally included in the ABX indices. As a result, each series references less than 15% of the underlying deal volume at issuance.8 Duration effects at the AAA level are bound to be significant for overall loss estimates as the AAA classes account for the lion’s share of MBS capital structures. Using prices for the newly instituted PENAAA indices, which reference “second to last” AAA bonds, to calculate AAA mark to market losses generates an estimate of $73 billion. This, in turn, translates into an overall valuation loss of $205 billion (ie some 18% below the unadjusted estimate of $250 billion).capitalisation had recovered, while remaining weaker than before the crisis. At the same time, still-elevated implied volatilities suggested ongoing investor uncertainty over the future trajectory of credit markets. With the credit cycle continuing to deteriorate and related losses on exposures outside the residential mortgage sector looming, it was thus unclear whether liquidity supply and risk tolerance had recovered to an extent that would help maintain this improved environment on a sustained basis.Bond yields recover as markets stabiliseFrom its low point on 17 March, the 10-year US Treasury bond yield rose by 75 basis points to reach 4.05% at the end of May. During this period, 10-year yields in the euro area and Japan climbed by around 70 and 50 basis points, respectively, to 4.40% and 1.75% (Graph 5, left-hand panel). In US and euro area bond markets, the increase in yields was particularly pronounced for short maturities, with two-year yields rising by 130 basis points in the United States and by almost 120 basis points in the euro area (Graph 5, centre panel). Two-year yields went up in Japan too, but by a more modest 35 basis points. In addition to reduced safe haven demand for government securities, the rise in short-term yields reflected a reassessment among investors of the need for monetary easing, following the stabilisation of financial markets.In the first two weeks of March, as the financial turmoil deepened and forward rates dropping (Graph 6, right-hand panel). While flight to safety and other effects relating to the volatility in financial markets may have influenced consistent with the observed fall at the short end of the forward break-evencurve. At the same time, these same concerns led investors to increasinglyexpect the Federal Reserve to maintain a more accommodative policy stancethan normal in an effort to contain the fallout on economic growth. Insofar asthis was seen as likely to lead to higher prices down the road, it could explainthe rise in distant forward break-even rates at the time.As the situation in financial markets stabilised after the rescue of BearStearns in mid-March, and perceptions of the economic outlook improvedsomewhat, the US forward break-even curve shifted in the opposite directionand flattened considerably. To a large extent, this shift in the forward curve islikely to have reflected a reversal of the same influences that had been at playin the first two weeks of March: the dampening effect on prices coming from theturmoil was perceived to be weaker after mid-March, while the Federal Reservewas seen to be less likely to deliver further sharp rate cuts. Moreover, upwardprice pressures appeared to intensify in the short to medium term, with foodprices rising continuously and oil prices reaching new all-time highs during thisperiod (Graph 5, right-hand panel), pushing near-term forward break-evenrates further upwards.real yields reflected a combination of expectations of higher average realinterest rates in coming years and a reversal of flight to safety pressures. Theformer component, in turn, was due to perceptions among investors that thereal economic fallout from the financial turmoil was likely to be less severe thanhad previously been anticipated. This was despite indications of deterioratingconsumer confidence amid tighter bank lending standards and continuedweakness in US housing markets. The revival in investor confidence seemedinstead to follow from the stabilisation in markets and from a number ofrelatively upbeat macroeconomic announcements. These included better thangovernment securities.In line with perceptions that the stabilisation of markets had reduced therisks to economic growth somewhat, prices of short-term interest rateindicating expectations of a period of stable rates, followed by rising rates inthe first half of 2009 (Graph 7, left-hand panel). In the euro area, EONIA swapprices at the beginning of March had signalled expectations of sizeable ECBrate cuts, but by end-May prices had shifted to reflect expectations of graduallyincreasing policy rates (Graph 7, centre panel). Meanwhile in Japan,expectations of mildly falling policy rates in March had by May been revised toindicate rising rates (Graph 7, right-hand panel).A turning point for equity prices?to end-2007 levels, gained almost 10% between 17 March and end-May. Equity markets in Europe and Japan, which had seen losses in excess of 20% between the turn of the year and 17 March, subsequently also displayed a strong recovery, with the EURO STOXX gaining 11% and the Nikkei 225 rising Reflecting the improved situation in financial markets during this period, by almost 20% and 34%, respectively. These gains occurred despiteannouncements by several banks of record losses during the first quarter amidcontinued credit-related write-offs. Investors obviously took solace from the factthat losses – although big – were no worse than expected, and that a numberof banks had been successful in their recapitalisation efforts (see credit marketsection above).surprises remained well above that of negative surprises, provided somesupport for equity prices. In addition, as fears failed to materialise that economic growth might slow dramatically in the first few months of the year,investors increasingly began to see equity valuations as attractive following thesharp price declines in late 2007 and early 2008. markets recovered after a sharp dip in March (Graph 8, right-hand panel).Emerging market investors discount growth risksequities fell up to mid-March, before rebounding in the wake of the change inmarket sentiment following the Bear Stearns rescue in the United States.Between end-February and end-May, the MSCI emerging market indexgained about 4% in local currency terms, and was up more than 14% from thelows established in mid-March. Latin American markets, which had seen ahigh trading volumes in commodity derivatives (see the Highlights section inthis issue) and speculative demand as a source of part of that strength, otherspointed to low supply elasticities and expectations of sustained rates ofindustrialisation throughout the emerging markets. With the region being amajor net commodities importer and natural disaster contributing to weakerequity prices in China, Asian markets were broadly flat over the period.Emerging Europe, in turn, remained exposed to the risk of a reversal in privatecapital flows, owing to large current account deficits and associated financingneeds in a number of countries. Nevertheless, strong gains in Russia and thebetter than expected growth performance of major European economies in thefirst quarter seemed to aid equity markets in May.Emerging market credit spreads, as measured by the EMBIG index,accounting for most of the spread tightening, the EMBIG remained almost flatin return terms, gaining about 1.1% between end-February and end-May(Graph 9, left-hand panel). Large stocks of foreign reserves and favourablemacroeconomic performance in key emerging market economies continued toprovide support, aiding the market recovery. Spread dispersion remained high,pointing to ongoing price differentiation according to credit quality (Graph 10,centre panel). At the same time, with inflation running well above target in anumber of major emerging market economies, policy credibility appeared tobecome more of a concern, putting pressure on local bond markets. Risinginflation expectations, combined with increasing US Treasury yields andrelatively resilient markets during the earlier stages of the recent marketturmoil, may thus have contributed to a somewhat more muted performancefrom emerging market bonds relative to other asset markets over the periodsince mid-March.Tensions in interbank markets remain highas high at the end of May as three months earlier, across most horizons and inall three major markets (Graph 10). This appeared to imply expectations thatinterbank strains were likely to remain severe well into the future.After a relatively smooth turn of the year, interbank market tensions hadappeared to ease somewhat until early March 2008, and Libor-OIS spreadshad shown some signs of stabilising. However, as the financial turmoilsuddenly deepened in the second week of March, following an acceleration inmargin calls and rapid unwinding of trades (see the credit section above),interbank market pressures quickly increased. With market rumoursproliferating about imminent liquidity problems in one or more large investmentbanks, banks became increasingly wary of lending to others. At the same time,their own demand for funds jumped as they sought to avoid being perceived ashaving a shortage of liquidity.Selected central bank liquidity measures during the period under review7 March The Federal Reserve increases the size of its Term Auction Facility (TAF) to $100 billion andextends the maturity of its repos to up to one month.11 March The Federal Reserve introduces the Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF), which allowsprimary dealers to borrow up to $200 billion of Treasury securities against collateral. Theexisting dollar swap arrangements between the Federal Reserve and the ECB and the SNB areincreased from a total of $24 billion to $36 billion.16 March The Federal Reserve introduces the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), which providesovernight funding for primary dealers in exchange for collateral. The Federal Reserve alsolowers the spread between the discount rate and the federal funds rate from 50 to 25 basispoints, and lengthens the maximum maturity from 30 to 90 days.28 March The ECB announces that the maturity of its longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs) wouldbe extended from up to three months to a maximum of six months.21 April The Bank of England introduces the Special Liquidity Scheme, under which banks can swapilliquid assets for Treasury bills.2 May The Federal Reserve boosts the size of its TAF programme to $150 billion, and announces abroadening of the collateral eligible for the TSLF auctions. The dollar swap arrangements withthe ECB and the SNB are increased further, from $36 billion to $62 billion.Source: Central bank press releases. Table 1The near collapse and subsequent takeover of Bear Stearns onMarch highlighted the risks that banks face in such situations. On the would not be allowed to fail, and this helped restore order in other markets. On the other hand, the speed with which Bear Stearns’ access to market liquidity had collapsed underscored the vulnerability of other banks in this regard, which kept Libor-OIS spreads high even as CDS spreads on banks and brokerages Throughout the period, central banks maintained and even stepped up activity from central banks seemed to have limited immediate impact oninterbank rates. To some extent, this may have reflected the fact that while thesums involved in central bank liquidity schemes were large in absolute terms,they were still rather limited compared to banks’ assessment of their overallliquidity needs against the background of a sharp decline in traditional sourcesof funding. One significant source of short-term funding for banks in the pasthas been money market mutual funds. Such funds have seen substantialinflows since the outbreak of the financial turmoil (Graph 11, left-hand panel),reflecting a noticeable reduction in investors’ appetite for risk. However, thisloss of risk appetite also resulted in money market funds shifting theirinvestments increasingly into treasury bills and other safe short-term securities,hence depriving banks of a key funding source (Graph 11, centre panel). Thissuggests that determining how persistent the interbank tensions will be maydepend significantly, among other things, on how long the risk appetite ofmoney market fund managers, and investors more broadly, will continue to bedepressed.。