华政法律英语翻译大赛初赛试题

- 格式:doc

- 大小:29.08 KB

- 文档页数:4

1. To discuss the differences between the civil law system and the common law system. (P4 )There are many differences between civil law system and common law system. Ⅰ The original places are different. The civil law system originated in ancient Rome, and the common law system originated in England.起源地不同,民法起源于古罗马,普通法起源于英格兰Ⅱ The main traditional source of the common law is cases, while the main traditional source of the civil law is legislation. Thus there are many codes in civil law countries instead of unwritten laws in common law system.普通法的主要传统渊源是案例法,民法的主要传统渊源是成文法。

因此民法国家用许多成文法典取代普通法国家的不成文法Ⅲ The civil law system pays more attention to substantive law; the common law system pays more attention to procedural rules.民法法系更多关注实体法,普通法更关注程序规则Ⅳ The classification of law is different. The civil law is separated into public law and private law, the common law is separated into common law and equity.法的分类不同,民法法系分为公法和私法,普通法法系分为普通法和衡平法Ⅴ The role of judges and professors is another difference. Since theory and doctrines is important in legal education of civil law system, professor plays the important role to expose laws to students. In the contrary, case-law is the main source of common law, thus the judges has the discretion to make laws while trialing cases.法官和学者的作用不同,因为理论和学说在民法法系中的重要性,学者在教授学生法律时十分重要。

1:外国合者如果有意以落后的技和行欺,造成失的,失。

If the foreign joint venturer causes any losses by deception the intentional use of backward technology and equipment, it shall payc o m p e n s a t i o n f o r t h e l o s s through e s.修改提示:复数考不周;用不。

答案(修改要点): causes any losses → causes any loss(es) 造成一或多失都当,不能用复数形式。

pay compensation for the losses → pay compensation therefor (therefor=for that/them)2:人民法院、人民察院和公安机关理刑事案件,当分工,互相配合,互相制,以保准确有效地行法律。

原文: The people ’s courts, people ’s procuratorates and public security organs shall, in handling criminal cases, divide their functions, each taking responsibility for its own work, and they shall co-ordinate their efforts andcheck each other to ensure correct and effective enforcement of law.修改提示:“分工”,理解:重点在“ ”,而非“分工”,即分工程中各其; respective比own更妥当、准确;原来的文中,and theyshall ⋯比,更重的是,使 to ensure ⋯割断了与 divide their functions 的系。

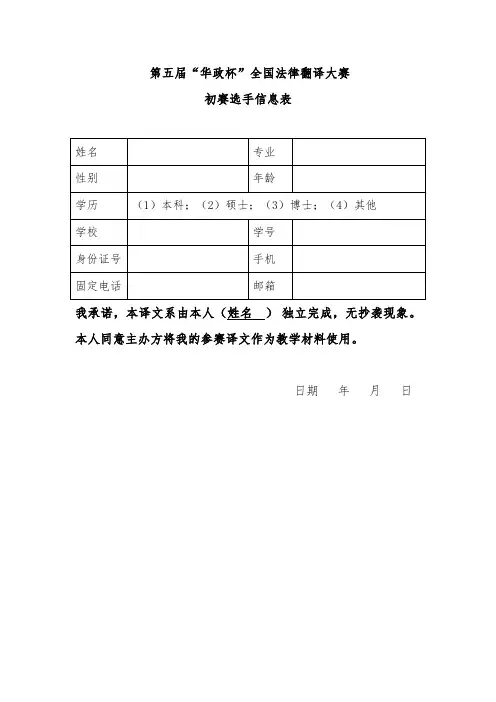

第五届“华政杯”全国法律翻译大赛初赛选手信息表我承诺,本译文系由本人(姓名)独立完成,无抄袭现象。

本人同意主办方将我的参赛译文作为教学材料使用。

日期年月日第五届“华政杯”全国法律翻译大赛初赛试题试题一(325 words)The U.S. Supreme Court has not squarely confronted the death penalty's constitutionality since the 1970s. In that decade, the Court actually ruled both ways on the issue. In McGautha v. California,the Court first held in 1971 that a jury's imposition of the death penalty without governing standards did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause. But then in 1972, in the landmark case of Furman v. Georgia,the Court interpreted the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause to hold that death sentences—as then applied—were unconstitutional. In that five-to-four decision, delivered in a per curiam opinion with all nine Justices issuing separate opinions, U.S. death penalty laws were struck down as violations of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. The sentences of the “capriciously selected random handful” of those sentenced to die, one of the Justices wrote, are “cruel and unusual in the same way being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual.” Other Justices also emphasized the arbitrariness of death sentences, with some focusing on the inequality and racial prejudice associated with them.Four years later, the Supreme Court reversed course yet again, approving once more the use of executions. After thirty-five states reenacted death penalty laws in the wake of Furman,the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of death penalty statutes in Gregg v. Georgia and two companion cases. The Court ruled that laws purporting to guide unbridled juror discretion—and requiring capital jurors to make special findings or to weigh “aggravating”versus “mitigating”circumstances—withstood constitutional scrutiny. The Court in Gregg emphasized that the Model Penal Code itself set standards for juries to use in death penalty cases. Only mandatory death sentences, the Court ruled that year, were too severe and thus unconstitutional. In its decision in Woodson v. North Carolina, the Court explicitly ruled mandatory death sentences, the norm in the Framers' era, were no longer permissible and had been “rejected” by American society “as unduly harsh and unworkably rigid.”试题二(348 words)The main features of the Anglo-American civil trial developed in the practice of the English common law courts in medieval and early modern times, as a consequence of the jury system, in which panels of lay persons were used to decide cases. Legal professionals—judges and lawyers—operated the initial pleading stage of the procedure, which was meant to identify and to narrow the dispute between the parties. If the dispute turned on a matter of law—that is, on a question such as whether the complaint stated a legally actionable claim, or whether some particular legal rule governed—the professional judges decided the case on the pleadings. If, however, the pleadings established that the case turned on a question of fact, the case was sent for resolution at trial by a jury composed of citizens untrained in the law. So tight was the linkage between trial and jury that there was in fact no such thing as nonjury trial at common law. In any case involving a disputed issue of fact, bench trial was unknown until the later nineteenth century.In the early days of the jury system, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, jurors were drawn from the close vicinity of the events giving rise to the dispute, in the expectation that the jurors would have knowledge of the events, or if not, that the jurors would be able to investigate the matter on their own in advance of the trial. Medieval jurors came to court mostly to speak rather than to listen—not to hear evidence, but to report a verdict that they had agreed upon in advance. Across the later Middle Ages, the jury ceased to function in this way for complex reasons, including cataclysmic demographic dislocations following the Black Death of the 1340s and the effects of urbanization in producing more impersonal social relations. By early modern times, jurors were no longer expected to come to court knowing the facts. The trial changed character and became an instructional proceeding to inform these lay judges about the matter they were being asked to decide.试题三(358 words)Among businessmen and lawyers familiar with commercial practice in complex transactions on both sides of the Atlantic, it is a common observation that a contractdrafted in the United States is typically vastly more detailed than a contract originating in Germany or elsewhere on the Continent.Why are American contracts so much more detailed than European? The Belgian legal writer Georges van Hecke discussed this subject in a stimulating paper that is now a quarter-century old. He offered three explanations. 1. Perfectionism.Van Hecke attributed to the American lawyer a drive “for perfection that is not commonly to be found in Europe. The average American businessman is prepared to pay for this perfection in the form of high fees,” while his European counterpart is not. 2. Federalism.Van Hecke directed attention to the multiplicity of American jurisdictions. “An American lawyer, when drafting a contract, does not know in what jurisdiction litigation will arise. He must make a contract that will achieve its purpose in any American jurisdiction.” By contrast, the European lawyer “always has in mind the law of one country where the contract is being localized by both choice of law and choice of forum.” 3. Code law versus case law.The most intriguing of van Hecke's suggestions is that the different American style of contracting is a manifestation of that seemingly profound difference between Continental and Anglo-American legal systems: The European private law is codified whereas the American is not. Codification, especially in Germany and in the German-influenced legal systems, entailed not only a reorganization of the law, but a scientific recasting of legal concepts. “The European lawyer has at his command a store of synthetic concepts, such as 'force majeure'. Their exact meaning may not always be perfectly clear, but they do save a lot of space-consuming enumeration.” By contrast, American lawyers draft to combat “the lawless science of their law, that codeless myriad of precedent, that wilderness of single instances.”Thus, van Hecke observes, “when a European and an American lawyer want to express the same thing, an American lawyer needs far more words.” American contracts are prolix because American substantive law is primitive.试题四(344 words)In international law, including WTO law, it is well accepted that certain questions of a preliminary character which are independent from the merits maynonetheless stop the proceedings before findings on the merits are made. This eventuality need not be expressly stated in the governing instruments of the judicial body concerned. Questions of jurisdiction and admissibility are both part of the universe of preliminary questions that, while leaving the merits of the case untouched, have the potential to prevent or postpone a final judgment on the merits.The difference between jurisdiction and admissibility is a feature of the general international law of adjudication. Besides the International Court of Justice, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and arbitral tribunals have also made this distinction. For example, in SGS v. Philippines, the tribunal of International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes found that it did have jurisdiction to consider a contractual claim under the so-called "umbrella clause" of the bilateral investment treaty at issue. The tribunal, however, declined to exercise this jurisdiction, concluding that the claim was not admissible because of a forum clause in the contract stating that contractual claims must be brought to domestic courts. Importantly, neither the Statute of the International Court of Justice, nor the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States, under which SGS v. Philippines was decided, explicitly includes the distinction between jurisdiction and admissibility. The Dispute Settlement Understanding of the WTO does not contain this distinction either, but that alone is not a reason to disregard the distinction out of hand. In fact, the dichotomy between jurisdiction and admissibility is embedded in the separation between the authority of the tribunal and the more general procedural relationship between the parties. The development of this distinction before the International Court of Justice, and its spillover to the ECHR and arbitral tribunals, indicates that there is a more general role for it in international dispute settlement. Analogously, in our view, the distinction between jurisdiction and admissibility should also be applied in WTO dispute settlement.。

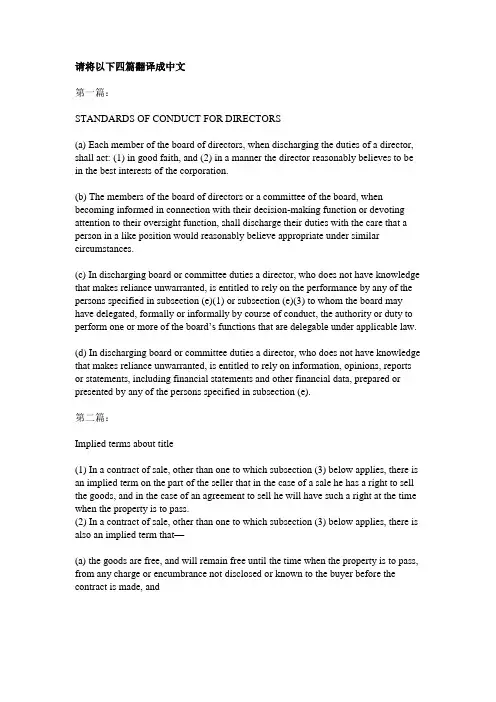

请将以下四篇翻译成中文第一篇:STANDARDS OF CONDUCT FOR DIRECTORS(a) Each member of the board of directors, when discharging the duties of a director, shall act: (1) in good faith, and (2) in a manner the director reasonably believes to be in the best interests of the corporation.(b) The members of the board of directors or a committee of the board, when becoming informed in connection with their decision-making function or devoting attention to their oversight function, shall discharge their duties with the care that a person in a like position would reasonably believe appropriate under similar circumstances.(c) In discharging board or committee duties a director, who does not have knowledge that makes reliance unwarranted, is entitled to rely on the performance by any of the persons specified in subsection (e)(1) or subsection (e)(3) to whom the board may have delegated, formally or informally by course of conduct, the authority or duty to perform one or more of the board’s functions that are delegable under applicable law.(d) In discharging board or committee duties a director, who does not have knowledge that makes reliance unwarranted, is entitled to rely on information, opinions, reports or statements, including financial statements and other financial data, prepared or presented by any of the persons specified in subsection (e).第二篇:Implied terms about title(1) In a contract of sale, other than one to which subsection (3) below applies, there is an implied term on the part of the seller that in the case of a sale he has a right to sell the goods, and in the case of an agreement to sell he will have such a right at the time when the property is to pass.(2) In a contract of sale, other than one to which subsection (3) below applies, there is also an implied term that—(a) the goods are free, and will remain free until the time when the property is to pass, from any charge or encumbrance not disclosed or known to the buyer before the contract is made, and(b) the buyer will enjoy quiet possession of the goods except so far as it may be disturbed by the owner or other person entitled to the benefit of any charge or encumbrance so disclosed or known.(3) This subsection applies to a contract of sale in the case of which there appears from the contract or is to be inferred from its circumstances an intention that the seller should transfer only such title as he or a third person may have.(4) In a contract to which subsection (3) above applies there is an implied term that all charges or encumbrances known to the seller and not known to the buyer have been disclosed to the buyer before the contract is made.(5) In a contract to which subsection (3) above applies there is also an implied term that none of the following will disturb the buyer’s q uiet possession of the goods, namely—(a) the seller;(b) in a case where the parties to the contract intend that the seller should transfer only such title as a third person may have, that person;(c) anyone claiming through or under the seller or that third person otherwise than under a charge or encumbrance disclosed or known to the buyer before the contract is made.第三篇:The United States, after threatening unilateral action under the much criticized Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, brought the matter to the WTO. The facts presented by the United States Trade Representative were sharply contested. But even if these facts had been conceded, the United States would have faced a serious problem: neither trade law nor antitrust law provided a forum or context for examination of the whole problem. The alleged private restraints were subject to the jurisdiction of the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC), but the JFTC, not unpredictably, found no antitrust violation. Japan's trade-restraining statutes, alone, were the basis for the US case at the WTO, but they were only a piece of the picture.A dispute resolution panel concluded that Japan's laws did not run afoul of the GATT rules. Whether the laws seriously harmed trade and competition was not relevant. The GATT's prohibitions against trade-restraining laws are narrow. They do not prohibit measures simply because they unreasonably restrain trade. The US challenge failed because (i) the trade-restraining laws of the Japanese government were not new restraints of which the United States had no notice at the time Japan agreed to reduce its trade protection (i.e. the existence and enforcement of the laws did not defeat United States' reasonable expectations) and (ii) the measures did not discriminate against foreigners; they were neutral on their face.第四篇:In order to conceptualize this world, I introduce literature on legal pluralism, and I suggest that, following its insights, we need to realize that normative conflict among multiple, overlapping legal systems is unavoidable and might even sometimes be desirable, both as a source of alternative ideas and as a site for discourse among multiple community affiliations. Thus, instead of trying to stifle conflict either through an imposition of sovereigntist, territorially-based prerogative or through universalist harmonization schemes, communities might sometimes seek (and increasingly are creating) a wide variety of procedural mechanisms, institutions, and practices for managing, without eliminating, hybridity. Such mechanisms, institutions, and practices can help mediate conflicts by recognizing that multiple communities may legitimately wish to assert their norms over a given act or actor, by seeking ways of reconciling competing norms, and by deferring to other approaches if possible. Moreover, when deference is impossible (because some instances of legal pluralism are repressive, violent, and/or profoundly illiberal), procedures for managing hybridity can at least require an explanation of why a decision maker cannot defer. In sum, pluralism offers not only a more comprehensive descriptive account of the world we live in, but also suggests a potentially useful alternative approach to the design of procedural mechanisms, institutions, and practices.。

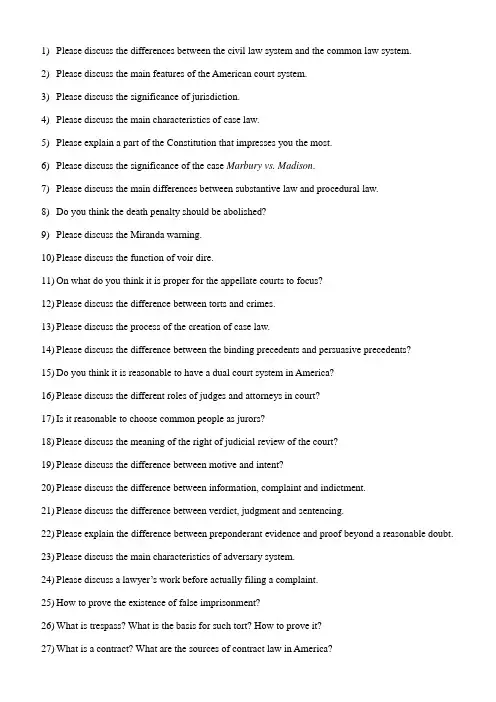

1)Please discuss the differences between the civil law system and the common law system.2)Please discuss the main features of the American court system.3)Please discuss the significance of jurisdiction.4)Please discuss the main characteristics of case law.5)Please explain a part of the Constitution that impresses you the most.6)Please discuss the significance of the case Marbury vs. Madison.7)Please discuss the main differences between substantive law and procedural law.8)Do you think the death penalty should be abolished?9)Please discuss the Miranda warning.10)Please discuss the function of voir dire.11)On what do you think it is proper for the appellate courts to focus?12)Please discuss the difference between torts and crimes.13)Please discuss the process of the creation of case law.14)Please discuss the difference between the binding precedents and persuasive precedents?15)Do you think it is reasonable to have a dual court system in America?16)Please discuss the different roles of judges and attorneys in court?17)Is it reasonable to choose common people as jurors?18)Please discuss the meaning of the right of judicial review of the court?19)Please discuss the difference between motive and intent?20)Please discuss the difference between information, complaint and indictment.21)Please discuss the difference between verdict, judgment and sentencing.22)Please explain the difference between preponderant evidence and proof beyond a reasonable doubt.23)Please discuss the main characteristics of adversary system.24)Please discuss a lawyer’s work before actually filing a complaint.25)How to prove the existence of false imprisonment?26)What is trespass? What is the basis for such tort? How to prove it?27)What is a contract? What are the sources of contract law in America?28)How do you define consideration? Why is it so important to the American contract law?29)How to prove the existence of false imprisonment?30)How to prove the existence of negligence?31)What is trespass? What is the basis for such tort?。

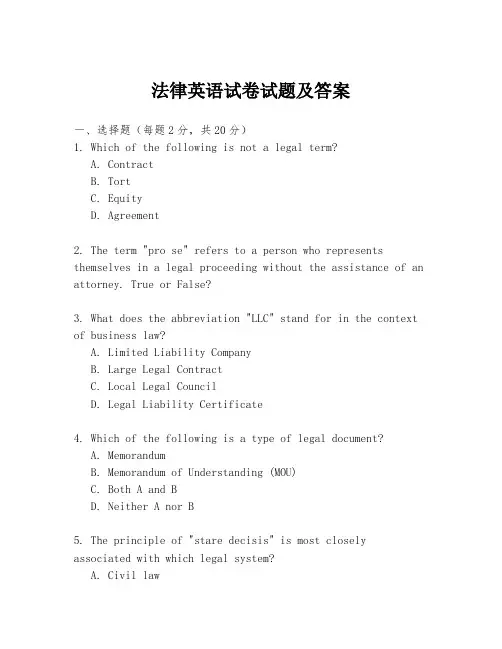

法律英语试卷试题及答案一、选择题(每题2分,共20分)1. Which of the following is not a legal term?A. ContractB. TortC. EquityD. Agreement2. The term "pro se" refers to a person who represents themselves in a legal proceeding without the assistance of an attorney. True or False?3. What does the abbreviation "LLC" stand for in the context of business law?A. Limited Liability CompanyB. Large Legal ContractC. Local Legal CouncilD. Legal Liability Certificate4. Which of the following is a type of legal document?A. MemorandumB. Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)C. Both A and BD. Neither A nor B5. The principle of "stare decisis" is most closely associated with which legal system?A. Civil lawB. Common lawC. Religious lawD. International law6. What is the term for the legal process of resolving disputes outside the court system?A. LitigationB. MediationC. ArbitrationD. Negotiation7. In the context of intellectual property law, "patent" refers to:A. A right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an inventionB. A document that grants ownership of a work of literature or artC. A legal document that protects a brand name or logoD. A license to practice a profession8. Which of the following is a fundamental principle of criminal law?A. Presumption of innocenceB. Right to a fair trialC. Both A and BD. Neither A nor B9. The term "precedent" in legal English refers to:A. A legal principle or rule established in a previous case that is binding in courtB. A document that outlines the facts of a caseC. A legal agreement between partiesD. A formal request for a court to review a case10. What does the term "actus reus" mean in criminal law?A. The guilty mindB. The wrongful actC. The criminal intentD. The legal defense二、填空题(每空1分,共10分)11. In legal English, "due process" refers to the fundamental legal rights that must be observed to ensure a fair trial.- The term "due process" is derived from the Latin phrase "due process of law."12. A "writ" is a formal written order issued by a court, typically directed to someone other than the parties in a case.- An example of a writ is a "writ of _habeas corpus_."13. The term "negligence" in tort law refers to the failure to exercise the degree of care that a reasonable person would exercise in the same situation to prevent harm to others.- In order to establish negligence, a plaintiff must prove the defendant's duty of care, breach of that duty, causation, and _damages_.14. "Probate" is the legal process by which a will is proved to be valid or invalid.- The court that oversees probate proceedings is known as the _probate court_.15. "Jurisdiction" refers to the authority of a court to hear and decide cases.- There are different types of jurisdiction, including_personal jurisdiction_, subject matter jurisdiction, and territorial jurisdiction.三、简答题(每题5分,共20分)16. Define "actus reus" and "mens rea" in the context of criminal law.17. Explain the concept of "joint and several liability" in tort law.18. What is the difference between "specific performance" and "damages" as remedies in contract law?19. Describe the process of "discovery" in civil litigation.四、案例分析题(每题15分,共30分)20. Case Study: A company has been accused of patent infringement. The company argues that they were not aware of the patent and therefore should not be held liable. Discuss the legal principles that may apply to this case and the possible outcomes.21. Case Study: A tenant has been evicted from their apartment without proper notice. The tenant claims that the eviction was unlawful. Analyze the relevant legal provisions and discuss the tenant's potential remedies.五、论述题(共20分)22. Discuss the role of language in legal interpretation and the challenges it presents. Provide examples to support your argument.参考答案:一、选择题1-5: D T A B B6-10: B C A B B二、填空题11. "due process of law"。

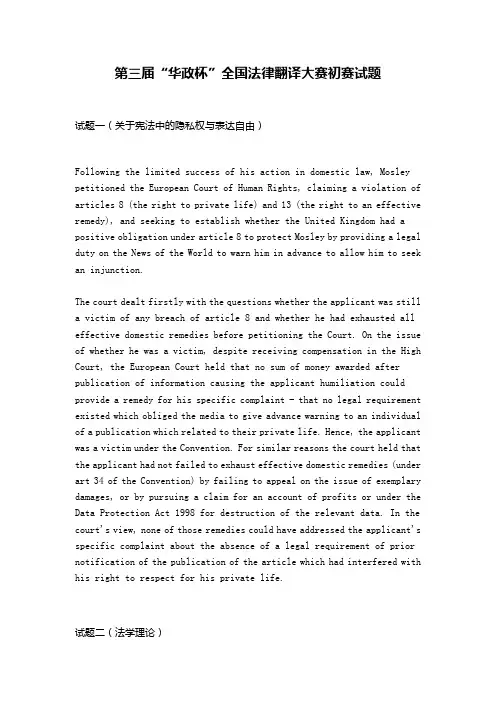

第三届“华政杯”全国法律翻译大赛初赛试题试题一(关于宪法中的隐私权与表达自由)Following the limited success of his action in domestic law, Mosley petitioned the European Court of Human Rights, claiming a violation of articles 8 (the right to private life) and 13 (the right to an effective remedy), and seeking to establish whether the United Kingdom had a positive obligation under article 8 to protect Mosley by providing a legal duty on the News of the World to warn him in advance to allow him to seek an injunction.The court dealt firstly with the questions whether the applicant was still a victim of any breach of article 8 and whether he had exhausted all effective domestic remedies before petitioning the Court. On the issue of whether he was a victim, despite receiving compensation in the High Court, the European Court held that no sum of money awarded after publication of information causing the applicant humiliation could provide a remedy for his specific complaint - that no legal requirement existed which obliged the media to give advance warning to an individual of a publication which related to their private life. Hence, the applicant was a victim under the Convention. For similar reasons the court held that the applicant had not failed to exhaust effective domestic remedies (under art 34 of the Convention) by failing to appeal on the issue of exemplary damages, or by pursuing a claim for an account of profits or under the Data Protection Act 1998 for destruction of the relevant data. In the court's view, none of those remedies could have addressed the applicant's specific complaint about the absence of a legal requirement of prior notification of the publication of the article which had interfered with his right to respect for his private life.试题二(法学理论)In the Middle Ages there was a twofold organization of paramount or legal social control, namely, state control and church control. The writers ofthe church took their ideas of law largely from the Greek philosophers and the Roman law books. They conceived that the state existed in order to maintain justice and so to maintain the law of God. The teachers of law in the medieval universities postulated an emperor over all Christendom in its temporal aspects as the pope was over its spiritual aspects. State and church were held co-workers in maintaining justice and realizing the law of God. In time, they became rivals for the paramountcy. But typically in the Middle Ages they were expected to work together as concurrent agencies of upholding the social and moral order. The so-called restoration of the empire under Charlemagne gave an ideal towhich men of the time recurred constantly in the quest of order and legal unity.But the ideas derived from the Roman law books were not only in contact with ideas of fathers of the church, they came also in contact with ideas of the Germanic law. Thus the juristic thought of the time was a resultant. There were two ideas of law: (1) The Roman-Byzantine, academic idea of enacted law— the civil law as enactments of the emperor Justinian, and the canon law as enactments of the popes — and (2) the idea of law as authoritatively declared custom, the idea of the customs of the Germanic peoples, authoritatively ascertained and declared by reduction to writing iuxta ex-emplum Romanorum.试题三(法律史)Historically, Chinese society preferred rule by moral suasion, rather than relying on codified law enforced by the courts. The teachings of Confucius1 have had an enduring effect on Chinese life and have provided the basis for the social order through much of the country's history. Confucians believed in the fundamental goodness of man and advocated adherence to li (propriety), a set of generally accepted social values or norms of behaviour. Education was considered the most important means for maintaining order, and codes of law were intended only to supplement li, not to replace it.Confucians held that codified law was inadequate to provide meaningful guidance for the entire panorama of human activity, but they were not against using laws to control the most unruly elements in the society. The first criminal code was promulgated sometime between 455 and 395 BC. There were also civil statutes, mostly concerned with land transactions.Most legal professionals were not lawyers but generalists trained in philosophy and literature. The local, classically trained, Confucian gentry played a crucial role as arbiters and handled all but the most serious local disputes. This basic legal philosophy remained in effect for most of the imperial era. The criminal code was not comprehensive and often not written down, which left magistrates great flexibility during trials. The accused had no rights and relied on the mercy of the court; defendants were tortured to obtain confessions and often served long jail terms while awaiting trial. A court appearance, at minimum, resulted in loss of face, and the people were reluctant and afraid to use the courts. Rulers did little to make the courts more appealing, for if they stressed rule by law, they weakened their own moral influence.试题四(民商法)Article 5.2 of the Commercial Law allows the parties to choose foreign law in case one party is a foreign element. The language which allows the parties to choose foreign law is slightly different and clearer than art.759 of the Civil Code:“Parties to a commercial transaction with a foreign element may agree to apply a foreign law or international practice, provided that such foreign law or international practice is not contrary to the basic principles of Vietnamese law.”Although the language of the Commercial Law is much clearer, it is not perfect. What constitutes “the basic principles of Vietnamese law”? A commercial contract is subject to both the general “basic principles”as set out in Ch. II Pt One of the Civil Code, and the “basic principles”as they specifically apply to a commercial transaction as set out in the Commercial Law. Both Codes contemplate that the parties are equal in the transaction and have freedom to negotiate and agree to terms. In addition, the Civil Code refers to the principle of legal compliance in “establishment and execution of civil rights and performance of civil obligations”, while the Commercial Code refers to the principle of application of common commercial practices. However, the grounds to challenge application of foreign law as incompatible with the “basic principles” of Vietnamese law would likely be narrow.初赛选手基本信息表。

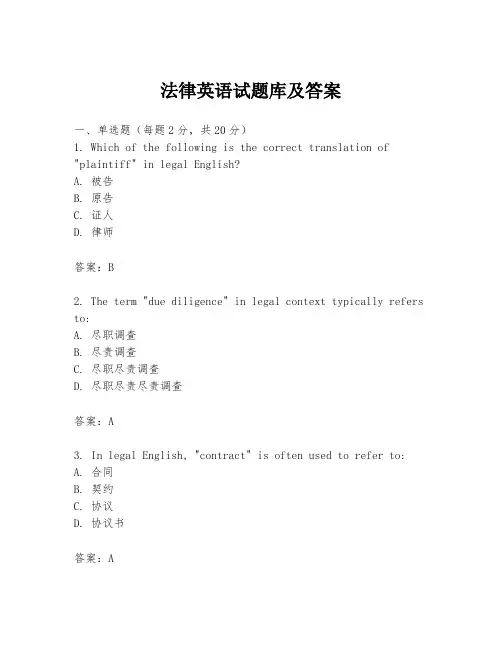

法律英语试题库及答案一、单选题(每题2分,共20分)1. Which of the following is the correct translation of "plaintiff" in legal English?A. 被告B. 原告C. 证人D. 律师答案:B2. The term "due diligence" in legal context typically refers to:A. 尽职调查B. 尽责调查C. 尽职尽责调查D. 尽职尽责尽责调查答案:A3. In legal English, "contract" is often used to refer to:A. 合同B. 契约C. 协议D. 协议书答案:A4. The phrase "in consideration of" is commonly used in legal documents to mean:A. 鉴于B. 考虑到C. 由于D. 因为答案:B5. Which of the following is not a type of intellectual property?A. 商标B. 专利C. 版权D. 商业秘密答案:D6. The term "tort" in legal English refers to:A. 侵权行为B. 犯罪行为C. 合同违约D. 民事纠纷答案:A7. "Jurisdiction" in legal English means:A. 管辖权B. 审判权C. 执行权D. 立法权答案:A8. The abbreviation "LLC" stands for:A. Limited Liability CompanyB. Limited Legal CompanyC. Legal Liability CompanyD. Legal Limited Company答案:A9. "Probate" in legal English refers to the process of:A. 遗嘱认证B. 遗嘱执行C. 遗嘱公证D. 遗嘱登记答案:A10. "Statute" in legal English is used to denote:A. 法规B. 法律C. 法令D. 条例答案:B二、填空题(每题2分,共20分)1. The legal term for a formal written statement submitted toa court is a(n) _____________.答案:brief2. A(n) _____________ is a legal document that outlines the terms and conditions of a contract.答案:agreement3. The process of challenging the validity of a will is known as _____________.答案:contest4. A(n) _____________ is a legal professional who represents clients in court.答案:attorney5. The term _____________ refers to the legal principle that no one may profit from their own wrongdoing.答案:unclean hands6. A(n) _____________ is a legal document that grants a person the authority to act on behalf of another.答案:power of attorney7. The legal term for a formal written request to a court is a(n) _____________.答案:petition8. A(n) _____________ is a legal document that provides evidence of a debt.答案:promissory note9. The legal term for a formal written order from a court is a(n) _____________.答案:decree10. A(n) _____________ is a legal document that outlines the terms and conditions of a sale of real estate.答案:deed三、判断题(每题2分,共20分)1. The term "lien" in legal English refers to a legal claim on property to secure the payment of a debt. (对/错)答案:对2. "Negligence" in legal English means the failure to exercise reasonable care, resulting in harm to another. (对/错)答案:对3. "Indemnity" in legal English refers to the right to be compensated for a loss or damage suffered. (对/错)答案:对4. A "writ" is a legal document issued by a court that ordersa person to do or refrain from doing a specific act. (对/错) 答案:对5. "Affidavit" in legal English is a written statement of facts voluntarily made by a person under oath. (对/错)答案:对6. "Misdemeanor" in legal English refers to a less serious crime than a felony. (对/错)答案:对7. "Arbitration" is a form of alternative dispute resolution where a neutral third party makes a binding decision. (对/错) 答案:对8. "Eminent domain" refers to the power of the government to take private property for public use without compensation. (对/错)答案:错9. "Venue" in legal English refers to the geographical location where a legal action is brought. (对/错)答案:对10. "Custody" in。

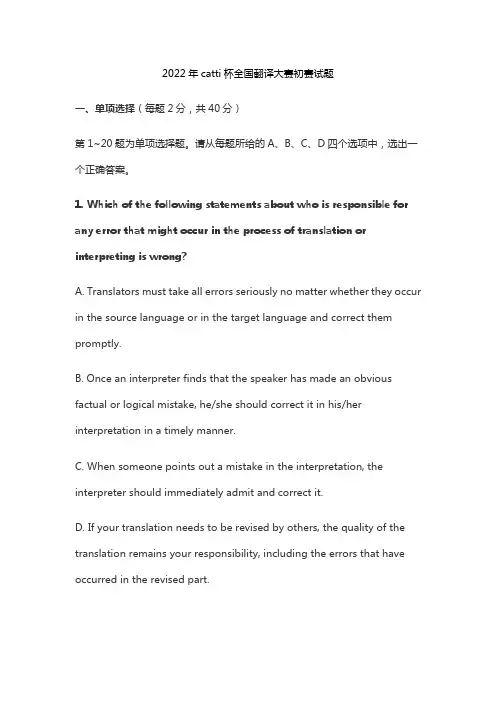

2022年catti杯全国翻译大赛初赛试题一、单项选择(每题2分,共40分)第1~20题为单项选择题。

请从每题所给的A、B、C、D四个选项中,选出一个正确答案。

1. Which of the following statements about who is responsible for any error that might occur in the process of translation or interpreting is wrong?A. Translators must take all errors seriously no matter whether they occur in the source language or in the target language and correct them promptly.B. Once an interpreter finds that the speaker has made an obvious factual or logical mistake, he/she should correct it in his/her interpretation in a timely manner.C. When someone points out a mistake in the interpretation, the interpreter should immediately admit and correct it.D. If your translation needs to be revised by others, the quality of the translation remains your responsibility, including the errors that have occurred in the revised part.2. Avery had established himself as a/an __________ microbiologist, but had never imagined venturing into the new world of genes and chromosomes.A. efficientB. competentC. patientD. innocent3. It is imperative that the government _______ more investment into the autonomous driving industry.A. attractsB. shall attractC. attractD. attracted4. We have maintained consultation with the ASEAN(东盟)on the formulation of codes of conduct in the South China Sea area.A. 制定中国南海地区行为准则B. 拟定中国南海地区行动准则C. 签订中国南海地区行动准则D. 形成中国南海地区行为准则5. 中国航空航天技术比较先进,是成功把人类送上太空的国家之一。

第六届“华政杯”全国法律翻译大赛初赛试题试题1 [340 words]The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) attempts to improve consistency in judicial decision making through a new legal device called the guiding cases system. According to the 2010 Guiding Cases Provisions, the SPC selects and publishes guiding cases that must be taken into account by lower courts when deciding similar cases.All legal systems must ensure a certain consistency in the application of law. The hierarchical organization of the judiciary provides for a mechanism that guarantees consistent adjudication. Typically, the highest courts within a judicial system have appellate jurisdiction relating to appeals on points of law. If a higher court disagrees with the interpretation of the law by a lower court, it will quash or amend the decision, or else remit the case to the lower court to decide in the light of the law as stated by the higher court. The authority of the decisions of the highest courts within a judicial system has the effect of making the application of law consistent throughout the judicial system. In common law systems, a decision made by a superior court is a binding precedent that all inferior courts are required to follow.In China, as in other continental legal systems, this doctrine of binding precedents is not applied. However, in legal systems that do not follow this doctrine, the appeal mechanism in effect renders the decisions of higher courts binding on lower courts. Lower courts follow the legal views of higher courts because their deviating decisions would be overturned on appeal by an appellate court. The Chinese four-level court system only allows one appeal to be made to a court of higher ranking, which minimizes the impact of the provincial high courts’or the SPC’s decisions on those of lower level courts. Compared with the organization of judiciaries in other countries, there appears to be a gap in the formal legal control over lower courts by provincial high courts and the SPC. Guiding cases are designed to fill this gap, promote centralization of the judiciary and strengthen the position of the SPC.(Source:Ahl, Björn: Retaining Judicial Professionalism: The New Guiding Cases Mechanism of the Supreme People’s Court. The China Quarterly, Volume 217, 2014.)试题2 [342 Words]The Supreme Court’s practice of revising its opinions is surprising to most people, including those who follow the Court, and naturally raises the question: Why? Why does the Court make mistakes notwithstanding the talent of its personnel and the intensity of its internal review procedures? Why does the Court not do more to eliminate mistakes prior to publication of the slip opinions? And why does the Court insist on correcting all of its mistakes? The answers to some of these questions are quite obvious, but to others far less so.One obvious answer is that everyone needs a good editor, and Supreme Court Justices are no exception, even those who are especially talented writers. In internal Court correspondence, ChiefJustice Stone described himself as “probably the most ineffective proof reader who ever sat on the Bench.” And the ce ntral role of the opinion, as the Court’s ultimate work product, makes it essential to write and edit carefully, which includes review and revision.Less obvious is why mistakes persist after publication of the slip opinion. After all, the structure of opinion writing within the Court provides ample opportunity for close scrutiny that invites revision. …The more elusive inquiry is therefore why, given all this exceedingly intense and skilled scrutiny, revision is still necessary after the Court’s opinion is first announced and published. As the Reporter himself acknowledged in private correspondence to the Chief Justice in 1984, by making a “considerable number of corrections and editorial changes in the Court’s opinions after their announcement and prior to their publication in the United States Reports . . . we actually operate a system that is completely at odds with general publishing practices.”The most fundamental reason is that mistakes are inevitable and will persist even after the rigorous reviewing process. The Justices and their chambers can, of course, reduce the number of mistakes by being more rather than less careful and by being more rather than less skilled. But no matter how much time and skill are applied, the possibility of mistakes cannot be eliminated.(Source: Richard J. Lazarus: The (Non)finality of Supreme Court Opinions. 128 Harvard Law Review, 2014. pp. 540-625.)试题3 [300 words]As in most writing on damages, the rights-based literature is rarely explicit about whether the law it purports to explain is a law that creates legal duties to pay damages or merely a law that provides for court-imposed liabilities –or whether the distinction even makes a difference. Rights-based theorists frequently describe damages law using the language of liabilities. But these theorists’explanations for that law assume and justify legal duties to pay damages. The explanations fall into two main groups. In the first group are explanations that suppose wrongdoers should pay damages for the same reason that they should comply with their primary legal duties. The reason is the same, according to this view, because the original duty transforms itself, at the moment of injury, into a duty to pay damages. For rights-based theorists who adopt this explanation, the original right that was breached lives on, albeit in a different form. The second group of rights-based explanations of damages supposes that committing a wrongful injury gives rise, on the basis of a complex notion of responsibility, to a new and different “duty to repair.” Both of these approaches thus explain damages law using the same kinds of individualist arguments that their defenders use to explain primary duties to perform contracts, not to injure others, and so forth. Indeed, rights-based theorists must explain damages in terms of individualist duties if they wish to provide a general theory of private law rather than merely a theory of primary duties. And like the individualist duties that explain primary legal duties, the individualist duties that, in this view, explain duties to pay damages arise from prelitigation facts – in this case the fact of a wrongful injury. It follows that, at least in principle, wrongdoers should pay damages immediately upon the commission of a wrong.(Source: Stephen A. Smith: Duties, Liabilities, and Damages, 125 Harv. L. Rev., 2012. pp. 1730-1731)试题4 [303 words]Each area of private law also has direct or indirect connections to others. The law of property informs the law of torts because one of the ways in which one person can wrong another is by interfering with the ownership, or use and enjoyment, of land and chattels. It follows that one will sometimes need to know the rules of property in order to know whether a tort has been committed. One will also need to take into account changing conceptions of property to make sense of tort law.A number of tort doctrines once hinged on the idea that a wife’s services counted as something in which her husband had a property interest. This patriarchal notion was the source of the actions for loss of consortium and alienation of affections. The eventual abandonment of this application of the concept of property had direct implications for tort law, though it did not have singular entailments. Courts and legislatures were faced with the question of whether to scrap these torts or to reconceptualize them as claims for interferences with spousal relations.Even though tort is to some degree dependent on property, tort is not beholden to property any more than it is beholden to contract, or any more than property and contract are beholden to tort. Some tort claims vindicate rights or interests that property and contract refuse to treat as possessory or contractual rights – for example, tortious interference with commercial advantage. Sometimes courts applying tort law reserve the right not to recognize what are, so far as the law of contract is concerned, valid waivers of liability for tortious conduct. Again, the departments and concepts of private law interact in complicated ways, and a lot of what legal reasoning should involve is thinking through these connections and what they entail for particular cases.(Source: John C. Goldberg, Introduction: Pragmatism and Private Law, 125 Harv. L. Rev., 2012. pp. 1654-1655)。

法律英语试题及答案一、单项选择题(每题2分,共10题,满分20分)1. Which of the following is not a legal term?A. PlaintiffB. DefendantC. LitigationD. Negotiation答案:D2. In legal English, "due process" refers to:A. A fair and just legal procedureB. A quick legal procedureC. A legal procedure without any delayD. A legal procedure with minimal paperwork答案:A3. The term "precedent" in law means:A. A previous case that sets a legal principleB. A document that records a legal decisionC. A legal principle that is not bindingD. A case that is not relevant to current legal issues 答案:A4. Which of the following is not a type of contract?A. Sales contractB. Employment contractC. Marriage contractD. Insurance contract答案:C5. "Tort" in legal English refers to:A. A civil wrongB. A criminal actC. A legal documentD. A legal remedy答案:A6. "Probate" is the legal process of:A. Dividing an estate after deathB. Filing a lawsuitC. Registering a trademarkD. Drafting a will答案:A7. "Jurisdiction" in law refers to:A. The authority to make legal decisionsB. The location of a courtC. The type of law being appliedD. The legal profession答案:A8. "Affidavit" is a legal document that:A. Is signed by a judgeB. Is a sworn statement of factsC. Is a request for a court orderD. Is a legal opinion答案:B9. "Statute" is a type of law that is:A. Created by judgesB. Passed by a legislative bodyC. Based on common lawD. Enforced by the executive branch答案:B10. "Moot" in legal context means:A. Unimportant or irrelevantB. A legal argumentC. A type of lawsuitD. A legal document答案:A二、填空题(每题2分,共5题,满分10分)1. A legal dispute that is not resolved by negotiation or mediation may proceed to ________.答案:litigation2. The ________ of a contract is the formal agreement between parties.答案:execution3. A ________ is a person who has been granted the authorityto act on behalf of another.答案:agent4. The ________ is the highest court in many legal systems.答案:supreme court5. A ________ is a legal document that outlines the terms ofa contract.答案:deed三、阅读理解题(每题3分,共3题,满分9分)阅读以下段落,并回答问题。

法律英语考查试题及答案一、英译汉1.general jurisdiction 一般管辖2.bar examination 律师考试3.ripeness 案件成熟度4.substantive law 实体法5.no contest pleas 不辩护也不认罪的答辩二、汉译英1.巡回法院 circuit courts2.模拟法庭 moot court3.案件决议度 mootness4.起诉书 complaint5.被上诉人 appellee三、翻译短文1.No two legal systems,then,are exactly alike.Each is specific to its country or its jurisdiction.This does not mean,of course,that every legal system is entirely different from every other legal system.Not at all.When two countries are similar in culture and tradition,their legal systems are likely to be similar as well.No doubt the law of E1Salvador is very much like the Law of Honduras.The laws of Australia and New Zealand are not that far apart.没有两个法系是恰好相似的。

每一种法系对于它的国家和它的管辖范围是特定的。

当然,这并不意味着每一种法系是完全不同于其它任何一种法系。

当两个国家在文化和传统上相似的时候,他们的法系也很可能相似。

难怪萨尔瓦多的法律和洪都拉斯的法律异常相似。

澳大利亚的法律和新西兰的法律也不是相差甚远。

第八届“华政杯”全国法律翻译大赛初赛试题试题1 (519 words)Appreciating the role of property in promoting public welfare necessitates rejecting the Blackstonian conception of property because market failures and the physical characteristics of the resources at stake often require curtailing an owner’s dominion so that ownership can properly serve the public interest. A similar lesson emerges from the robust economic analysis of takings law. This literature indeed shows that compensation is at times required to prevent risk-averse landowners from under-investing in their property and to create a budgetary effect that, assuming public officials are accountable for budget management, forces governments to internalize the costs of their planning decisions. These considerations are particularly pertinent to private homeowners, who are not professional investors and who have purchased a small parcel of land with their life savings, as well as to members of a marginal group with little political clout. But providing private landowners and public officials with proper incentives also implies that, in other cases, full compensation should not be granted. Where a piece of land is owned as part of a diversified investment portfolio, full compensation may lead to inefficient overinvestment, while the possibility of an uncompensated investment is likely to lead to an efficient adjustment of the landowner’s investment decisions commensurate with the risk that the land will be put to public use. Similarly, landowners who are members of powerful and organized groups can use non-legal means to force public officials to weigh their grievances properly. An indiscriminate regime of full compensation may therefore distort the officials’ incentives by s ystematically encouraging them to impose the burden on the non-organized public or on marginal groups, even when the best planning choice would be to place the burden on powerful or organized groups. The absolutist conception of property and the strict proportionality takings regime are also anathema to the most attractive conceptions of membership and citizenship, which insist on integrating social responsibility into our understanding of ownership. The absolutist conception of property expresses and reinf orces an alienated culture, which “underplays the significance of belonging to a community, [and] perceives our membership therein in purely instrumental terms.” In other words, this approach “defines our obligations qua citizens and qua community members as ‘exchanges formonetizable gains,’ . . . [and] thus commodifies both our citizenship and our membership in local communities.” To be sure, the impersonality of market relations is not inherently wrong; quite the contrary, by facilitating dealings “on an explicit, quid pro quo basis,” the market defines an important “sphere of freedom from personal ties and obligations.” A responsible conception of property can and should appreciate these virtues of the market norms. But it should still avoid allowing these norms to override those of the other spheres of society. Property relations participate in the constitution of some of our most cooperative human interactions. Numerous property rules prescribe the rights and obligations of spouses, partners, co-owners, neighbors, and members of local communities. Imposing the competitive norms of the market on these divergent spheres and rejecting the social responsibility of ownership that is part of these ongoing mutual relationships of give and take, would effectively erase these spheres of human interaction.试题2(509 words)In the common-law tradition, lawyers and jurists consult the reports of judicial decisions to determine applicable rules of law. Common lawyers conduct this evaluative process both as they plan transactions in the shadow of the law and as they frame cases for litigation. With careful attention to particular holdings, and to trends, dominant voices, and cogent rationales, adept practitioners of the common law can say where the law has settled for the moment and how it might evolve in the future. Judges often emerge as actors in the formulation of legal rules, sifting through the available materials to play the cautiously dynamic role that has come to be seen as the hallmark of common-law judging in the Anglo-American tradition. Occasionally, judges issue transformative opinions, ones that allow us to see both the past and the future more clearly and give voice to a bold new conception of the law that will one day be seen as self-evident. Few such opinions have emerged in the course of the war-on-terror litigation. Instead, as dissenting judges have warned, we have witnessed the “silent erosion” of human rights through the accumulation of balancing opinions by the federal courts. True, the Supreme Court has creatively deployed the writ of habeas corpus to ensure a measure of judicial review for enemy combatants detained,indefinitely, at Guantanamo Bay. In Boumediene v. Bush, moreover, the Court narrowly but decisively reaffirmed the role of the federal district courts in the face of legislation that proposed to confine judicial oversight within the narrow appellate-review boundaries set forth in the Detainee Treatment Act. The Constitution was said to guarantee detainees access to the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, and Congress was said to have violated that guarantee by restricting review without providing an adequate substitute. The alternative vision, boldly stated in Justice Scalia’s dissent, called for complete judicial deference in the treatment of alien detainees to the war-making power of the president. Although Justice Scalia did not accuse the majority of treason, he did describe the majority opinion as a bait-and-switch that would complicate the task of prosecuting the war and “almost certainly” lead to the death of more Americans. Wholesale judicial deference leaves the law inarticulate, as judges fail to perform the common-law function of passing on the legality of challenged conduct. As we have seen, the federal courts have failed to define what it means to torture a detainee, to opine on the legality of extrajudicial kidnaping (extraordinary rendition), and to specify what sorts of detainee abuse can be permitted before it rises to the level of cruel, inhuman, or degrading conduct. The federal courts have similarly failed to conclude that war-on-terror detainees enjoy the same protections that apply to other prisoners and pretrial detainees under the Fifth and Eighth Amendments. As a result of these judicial silences, one can say very little about the concrete legal status of the rendition, detention, and interrogation tactics deployed in the Bush administration’s war on terror, other than that they appear to be lawful more or less by default.试题3(485 words)The notion of restrictive interpretation is often used interchangeably with the principle of in dubio mitius, but the former can also be used to refer to other methods of interpretation, such as the interpretation of exceptions. According to the principle of in dubio mitius, ‘i f the meaning of a term is ambiguous, that meaning is to be preferred which is less onerous to the party assuming an obligation, or which interferes less with the territorial and personal supremacy of a party, orinvolves less general restrictions upon the parties’. Treaty language is not to be interpreted so as to limit state sovereignty or a state’s ‘personal and territorial supremacy’, ‘even though these stipulations do not conflict with such interpretation’. If the language on the existence or scope of an obligation is unclear, the in dubio mitius principle supports the proposition that no or only a minimal obligation should be applied. The application of the principle essentially results in an interpretation in deference to the sovereignty of one specific signatory, the party assuming an obligation (in practice, this is often the respondent state). Such an interpretation is supposed to protect the sovereignty of the parties to a treaty. But most treaty law restricts sovereignty, albeit through the exercise of state sovereignty. The Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) initially formulated the in dubio mitius principle as applicable ‘when, in spite of all pertinent considerations, the intention of the Parties still remains doubtful’ and unless i ts application would lead to an interpretation ‘contrary to the plain terms … and would destroy what has been clearly granted’. The principle is not codified in the VCLT (Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties) and is unlikely to qualify as a general principle of law or part of customary international law. The validity of applying the principle has also been denied where the language in different authentic versions of a treaty conflicts and the conflict cannot be resolved through the general principles of interpretation. The use of the principle appears to have received more support from scholars than from international courts and tribunals. Although the PCIJ cited the notion of restrictive interpretation (meaning, in this context, the principle of in dubio mitius) in several cases, it relied upon it only as a last resort and always emphasized its limits. The starting point of interpretation remains the terms of the treaty, not the interests of those who drafted the treaty in exercise of their sovereignty with the effect of transferring parts of that sovereignty. In the Wimbledon case, the PCIJ found that a restrictive interpretation stops ‘at the point where [it] would be contrary to the plain terms of the article and would destroy what has been clearly gra nted’. In the Nuclear Tests case, the ICJ (International Court of Justice) applied a restrictive interpretation to unilateral statements limiting a state’s freedom of action, followed by an extensive approach to whether a commitment existed.。

第九届“华政杯”全国法律翻译大赛初赛试题试题一:(598 words)Commerce’s primary argument is that the plain statutory language mandating that a countervailing duty “shall be imposed” requires it to impose countervailing duties when it is able to identify a subsidy, even in an NME country. See Commerce Br. 19-23; Commerce Reply Br. 2. We disagree. The text of the relevant statute states that if “the administering authority determines that the government of a country . . . is providing, directly or indirectly, a countervailable su bsidy,” and if the domestic injury requirement is met, “then there shall be imposed upon such merchandise a countervailing duty, in addition to any other duty imposed, equal to the amount of the net countervailable subsidy.” 19 U.S.C. § 1671. Contrary to C ommerce’s argument we do not find the statute to be clear on its face. The statute does not explicitly require the imposition of countervailing duties on goods from NME countries. The question is whether government payments in an NME economy constitute “co untervailable subsidies” within the meaning of the statute. We have indeed previously held that the statute does not compel the imposition of countervailing duties to goods from NME countries because the government payments with respect to such goods are n ot “bounties or grants,” or “countervailable subsidies” in the current terminology.Georgetown Steel, 801 F.2d at 1314.Section 303 of the Tariff Act of 1930, the predecessor to the current countervailing duty law, stated that “whenever any country . . . shall pay or bestow, directly or indirectly, any bounty or grant,” then “there shall be levied . . . in addition to any duties otherwise imposed, a duty equal to the net amount of such bounty or grant.” 19 U.S.C. § 1303 (1988) (repealed 1994). In Georgetown Steel we found that the “economic incentives and benefits” provided by governments in NME countries “do not constitute bounties or grants under section 303,” 801 F.2d at 1314, that is, “countervailable subsidies” in the language of the current statute. Georgetown Steel found “no indication . . . that Congress intended” this law to apply to NME exports, noting that the purpose of countervailing duty law is “to offset the unfair competitive advantage that foreign producers would otherwise enjoy from export subsidies,” and that “[i]n exports from a nonmarket economy . . . this kind of ‘unfair’ competition cannot exist.” 801 F.2d at 1315-16 (quoting Zenith Radio Corp. v. United States, 437 U.S. 443, 456 (1978)). We stated that “[e]ven if one were to label the incentives [provided by NMEs to exporting entities] as a ‘subsidy,’ . . . the governments of those nonmarket economies would in effect be subsidizing themselves.” Id. at 1316. We thus upheld Commerce’s decision not to impose countervailing duties on goods from NME countries.The “bounty or grant” language of Section 303 involved in Georgetown Steel was replaced by the current “countervailable subsidy” language in the Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. No. 103-465, 108 Stat. 4809 (1994) (“URAA”), but Co ngress made clear that this change was not intended to substantively affect the countervailing duty law. The URAA Statement of Administrative Action (“SAA”), which “shall be regarded as an authoritative expression by the United States concerning the interp retation and application of the [URAA],” 19 U.S.C. §3512(d), stated that “the definition of ‘subsidy’ will have the same meaning that administrative practice and courts have ascribed to the term ‘bounty or grant’ and ‘subsidy’ under prior versions of the statute” and that “practices countervailable under the current law will be countervailable under the revised statute,” H.R. Doc. No. 103-316, at 925 (1994). Thus, Georgetown Steel is equally applicable to the revised statute.试题二:(499 words)When a statute’s constitutionality is in doubt, we have an obligation to interpret the law, if possible, to avoid the constitutional problem. See, e.g., Edward J. DeBartolo Corp. v. Florida Gulf Coast Building & Constr. Trades Council, 485 U. S. 568, 575 (1988). As one treatise puts it, “[a] statute should be interpreted in a way that avoids placing its constitutionality in doubt.” A. Scalia & B. Garner, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts §38, p. 247 (2012). This canon applies fully when considering vagueness challenges. In cases like this one, “our task is not to destroy the Act if we can, but to construe it, if consistent with the will of Congress, so as to comport with constitutional limitations.” Civil Service Comm’n v. Lett er Carriers, 413 U. S. 548, 571 (1973); see also Skilling v. United States, 561 U. S. 358, 403 (2010). Indeed, “‘[t]he elementary rule is that every reasonable construction must be resorted to, in order to save a statute from uncon stitutionality.’” Id., a t 406 (quoting Hooper v. California, 155 U. S. 648, 657 (1895); emphasis deleted); see also Ex parte Randolph, 20 F. Cas. 242, 254 (No. 11,558) (CC Va. 1833) (Marshall, C. J.).The Court all but concedes that the residual clause would be constitutional if it applied to “real-world con duct.” Whether that is the best interpretation of the re sidual clause is beside the point. What matters is whether it is a reasonable interpretation of the statute. And it surely is that.First, this interpretation heeds the pointed distinction that the Armed Career Criminal Act of 1984 (ACCA) draws between the “element[s]” of an offense and “conduct.” Under §924(e)(2)(B)(i), a crime qualifies as a “violent felony” if one of its “element[s]” involves “the use, attempted use,or threatened use of physical force against the person of another.” But the residual clause, which appears in the very next subsection, §924(e)(2)(B)(ii), focuses on “conduct”—specifically, “conduct that presents a serious potential risk of physical injur y to another.” The use of these two different terms in §924(e) indicates that “conduct” refers to things done during the commission of an offense that are not part of the elements needed for conviction. Because those extra actions vary from case to case, it is natural to interpret “conduct” to mean real-world conduct, not the conduct involved in some Platonic ideal of the offense.Second, as the Court points out, standards like the one in the residual clause almost always appear in laws that call for application by a trier of fact. This strongly suggests that theresidual clause calls for the same sort of application.Third, if the Court is correct that the residual clause is nearly incomprehensible when interpreted as applying to an “idealized ordinary case of the crime,” then that is telling evidence that this is not what Congress intended. When another interpretation is ready at hand, why should we assume that Congress gave the clause a meaning that is impossible—or even, exceedingly difficult—to apply?各参赛选手任选一题作答,且只能提交一道试题的译文。