联合国招聘翻译真题

- 格式:docx

- 大小:14.13 KB

- 文档页数:1

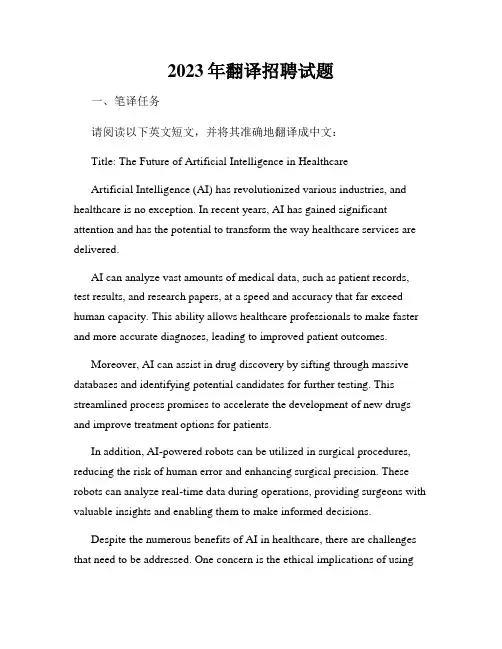

2023年翻译招聘试题一、笔译任务请阅读以下英文短文,并将其准确地翻译成中文:Title: The Future of Artificial Intelligence in HealthcareArtificial Intelligence (AI) has revolutionized various industries, and healthcare is no exception. In recent years, AI has gained significant attention and has the potential to transform the way healthcare services are delivered.AI can analyze vast amounts of medical data, such as patient records, test results, and research papers, at a speed and accuracy that far exceed human capacity. This ability allows healthcare professionals to make faster and more accurate diagnoses, leading to improved patient outcomes.Moreover, AI can assist in drug discovery by sifting through massive databases and identifying potential candidates for further testing. This streamlined process promises to accelerate the development of new drugs and improve treatment options for patients.In addition, AI-powered robots can be utilized in surgical procedures, reducing the risk of human error and enhancing surgical precision. These robots can analyze real-time data during operations, providing surgeons with valuable insights and enabling them to make informed decisions.Despite the numerous benefits of AI in healthcare, there are challenges that need to be addressed. One concern is the ethical implications of usingAI in patient care. It is essential to establish guidelines and regulations to ensure that AI is used responsibly and respects patient privacy.Furthermore, there is a need for ongoing training and education for healthcare professionals to effectively incorporate AI into their practice. This will enable them to fully utilize the potential of AI while maintaining a patient-centered approach.In conclusion, the future of artificial intelligence in healthcare is promising. With its ability to analyze data, assist in drug discovery, and enhance surgical procedures, AI has the potential to revolutionize the field and improve patient outcomes. However, careful consideration of ethical implications and proper training is necessary to ensure responsible and effective use of AI in healthcare settings.二、口译任务请听以下英文录音,并将其准确地口译成中文:[音频播放]Speaker 1: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for attending this conference. Today, I would like to talk to you about the importance of sustainable development in our cities.Speaker 2: Sustainable development is crucial for ensuring the well-being of our future generations. It involves striking a balance between economic growth, social progress, and environmental protection.Speaker 1: That's right. Sustainable cities should prioritize the use of renewable energy sources, promote public transportation, and implement waste management policies to reduce pollution.Speaker 2: Additionally, urban planning should focus on creating green spaces, such as parks and gardens, to improve the quality of life for residents.Speaker 1: Absolutely. We also need to encourage sustainable practices among individuals, such as recycling and conserving water and energy.Speaker 2: Education plays a vital role in promoting sustainable development. By raising awareness and providing knowledge, we can empower individuals to make environmentally conscious decisions.Speaker 1: In conclusion, sustainable development is not an option, but a necessity. It is our responsibility to create cities that are environmentally friendly, socially inclusive, and economically vibrant.[音频结束]三、写译任务请根据所提供的中文短文,将其准确地翻译成英文:标题:传统文化的保护与传承近年来,中国传统文化的保护与传承受到了广泛的关注。

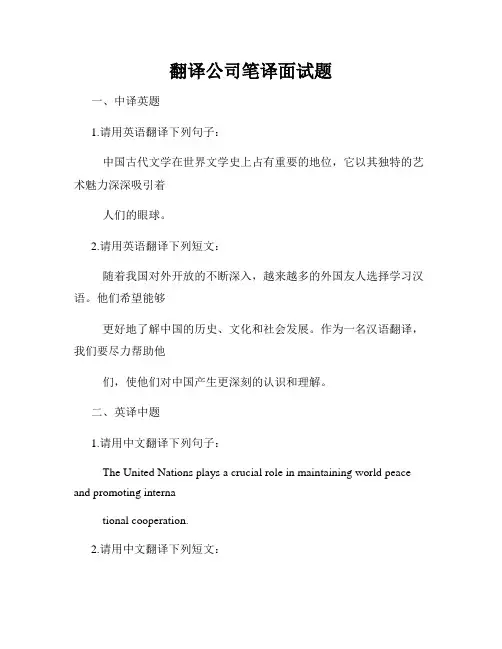

翻译公司笔译面试题一、中译英题1.请用英语翻译下列句子:中国古代文学在世界文学史上占有重要的地位,它以其独特的艺术魅力深深吸引着人们的眼球。

2.请用英语翻译下列短文:随着我国对外开放的不断深入,越来越多的外国友人选择学习汉语。

他们希望能够更好地了解中国的历史、文化和社会发展。

作为一名汉语翻译,我们要尽力帮助他们,使他们对中国产生更深刻的认识和理解。

二、英译中题1.请用中文翻译下列句子:The United Nations plays a crucial role in maintaining world peace and promoting international cooperation.2.请用中文翻译下列短文:With the development of globalization, the demand for professional translators is on the rise.A good translator not only needs to have excellent language skills, but also needs to have in-depthknowledge of various fields. Therefore, being a translator is not an easy job, but it is a rewardingand fulfilling profession.三、中英互译题1.请将下列中文句子翻译成英语:中国古代文学作品中的人物形象具有鲜明的个性特点,通过他们的言行举止,传达了丰富的思想情感。

2.请将下列英文句子翻译成中文:As a translator, it is important to accurately convey the original meaning of the text whiletaking into account the cultural nuances of both languages.四、语言运用题1.请用适当的中文词语或短语填空:翻译工作要求翻译人员不仅能理解原文的______,还要灵活运用翻译技巧和______,以准确传达原文的意思。

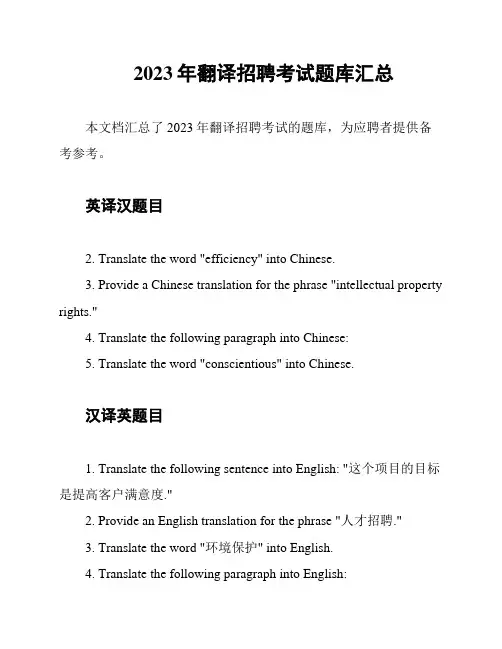

2023年翻译招聘考试题库汇总本文档汇总了2023年翻译招聘考试的题库,为应聘者提供备考参考。

英译汉题目2. Translate the word "efficiency" into Chinese.3. Provide a Chinese translation for the phrase "intellectual property rights."4. Translate the following paragraph into Chinese:5. Translate the word "conscientious" into Chinese.汉译英题目1. Translate the following sentence into English: "这个项目的目标是提高客户满意度."2. Provide an English translation for the phrase "人才招聘."3. Translate the word "环境保护" into English.4. Translate the following paragraph into English:"中国是世界上人口最多的国家之一,也是一个拥有悠久历史和丰富文化的国家。

中国的经济快速发展,吸引了许多国际投资者."5. Translate the word "创新" into English.视频笔译题目1. Watch the provided video clip and provide a written English translation of the content.2. Watch the provided video clip and provide a written Chinese translation of the content.以上是2023年翻译招聘考试题库的汇总,希望对应聘者备考有所帮助。

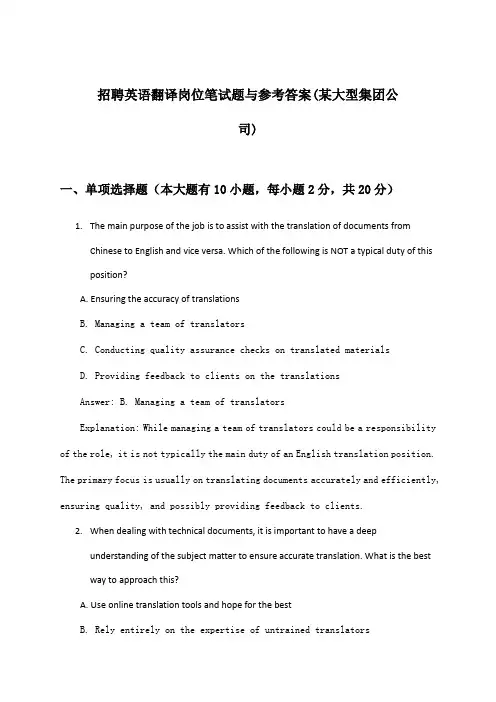

招聘英语翻译岗位笔试题与参考答案(某大型集团公司)一、单项选择题(本大题有10小题,每小题2分,共20分)1.The main purpose of the job is to assist with the translation of documents fromChinese to English and vice versa. Which of the following is NOT a typical duty of thisposition?A. Ensuring the accuracy of translationsB. Managing a team of translatorsC. Conducting quality assurance checks on translated materialsD. Providing feedback to clients on the translationsAnswer: B. Managing a team of translatorsExplanation: While managing a team of translators could be a responsibility of the role, it is not typically the main duty of an English translation position. The primary focus is usually on translating documents accurately and efficiently, ensuring quality, and possibly providing feedback to clients.2.When dealing with technical documents, it is important to have a deepunderstanding of the subject matter to ensure accurate translation. What is the bestway to approach this?A. Use online translation tools and hope for the bestB. Rely entirely on the expertise of untrained translatorsC. Collaborate with subject matter experts to review and refine translationsD. Ignore the importance of subject matter knowledge and focus solely on languageAnswer: C. Collaborate with subject matter experts to review and refine translationsExplanation: Accurate translation of technical documents requires a thorough understanding of the subject matter. By collaborating with subject matter experts, translators can ensure that the technical terms and concepts are correctly translated and that the documents are clear and understandable to the target audience.3、在商务英语翻译中,下列哪项是最常见的术语使用不当的例子?A. 将“cost-effective”翻译为“实惠的”,而不是按照其在特定商务语境下的意义“性价比高的”。

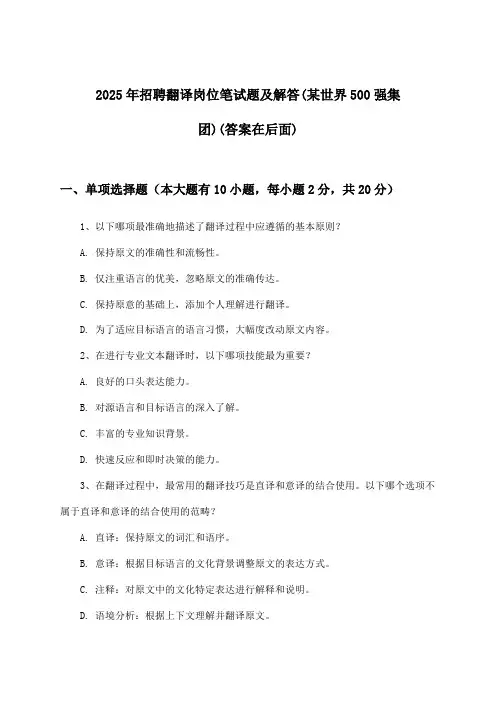

2025年招聘翻译岗位笔试题及解答(某世界500强集团)(答案在后面)一、单项选择题(本大题有10小题,每小题2分,共20分)1、以下哪项最准确地描述了翻译过程中应遵循的基本原则?A. 保持原文的准确性和流畅性。

B. 仅注重语言的优美,忽略原文的准确传达。

C. 保持原意的基础上,添加个人理解进行翻译。

D. 为了适应目标语言的语言习惯,大幅度改动原文内容。

2、在进行专业文本翻译时,以下哪项技能最为重要?A. 良好的口头表达能力。

B. 对源语言和目标语言的深入了解。

C. 丰富的专业知识背景。

D. 快速反应和即时决策的能力。

3、在翻译过程中,最常用的翻译技巧是直译和意译的结合使用。

以下哪个选项不属于直译和意译的结合使用的范畴?A. 直译:保持原文的词汇和语序。

B. 意译:根据目标语言的文化背景调整原文的表达方式。

C. 注释:对原文中的文化特定表达进行解释和说明。

D. 语境分析:根据上下文理解并翻译原文。

4、在翻译一部外文作品时,译者首先需要做的是:A. 了解原作者的意图和风格。

B. 熟悉目标语言的文化背景。

C. 翻译初稿。

D. 校对和修改。

5、以下哪项是翻译工作中常用的专业术语?A. 法律B. 艺术C. 数学D. 物理6、在翻译中,以下哪个词组经常用于表示道歉?A. 对不起B. 谢谢你C. 请原谅D. 再见7、在翻译过程中,遇到专业术语或行业特定的表达方式时,以下哪种做法最为恰当?A. 使用日常用词替代专业术语。

B. 直接采用外文,避免混淆和误解。

C. 猜测其含义并直接翻译。

D. 查阅相关资料或请教专业人士以确保准确性。

8、对于两种语言的转换过程中,下面哪种观点更符合翻译的实际操作原则?A. 应完全遵循原文的语法结构进行翻译。

B. 应注重保持原文的语义内容,同时考虑目的语言的表达习惯。

C. 可以添加个人主观感受或对原文进行改写,以增强翻译的感染力。

D. 翻译时只需关注词汇的对应转换即可,无需考虑文化背景差异。

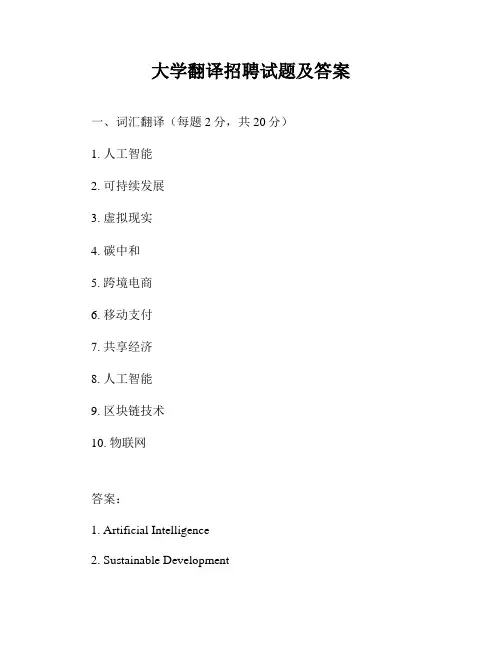

大学翻译招聘试题及答案 一、词汇翻译(每题2分,共20分) 1. 人工智能 2. 可持续发展 3. 虚拟现实 4. 碳中和 5. 跨境电商 6. 移动支付 7. 共享经济 8. 人工智能 9. 区块链技术 10. 物联网

答案: 1. Artificial Intelligence 2. Sustainable Development 3. Virtual Reality 4. Carbon Neutrality 5. Cross-border E-commerce 6. Mobile Payment 7. Sharing Economy 8. Artificial Intelligence 9. Blockchain Technology 10. Internet of Things

二、句子翻译(每题5分,共30分) 1. 随着全球化的不断推进,跨文化交流变得越来越重要。 2. 该公司致力于开发创新技术,以提高生产效率和降低成本。 3. 这个项目旨在通过教育和培训,提高农村地区的就业率。 4. 随着科技的发展,远程工作已经成为许多行业的新常态。 5. 为了保护环境,政府采取了一系列措施,包括减少工业排放和推广可再生能源。

6. 随着互联网的普及,越来越多的人开始在线购物。 7. 这家公司通过提供高质量的产品和服务,赢得了良好的声誉。 8. 教育是提高一个国家竞争力的关键因素之一。 9. 随着人口老龄化的加剧,医疗保健系统面临着前所未有的挑战。

10. 为了应对气候变化,各国需要加强合作,共同寻找解决方案。

答案: 1. With the continuous advancement of globalization, cross-cultural communication has become increasingly important.

2. The company is committed to developing innovative technologies to improve production efficiency and reduce costs.

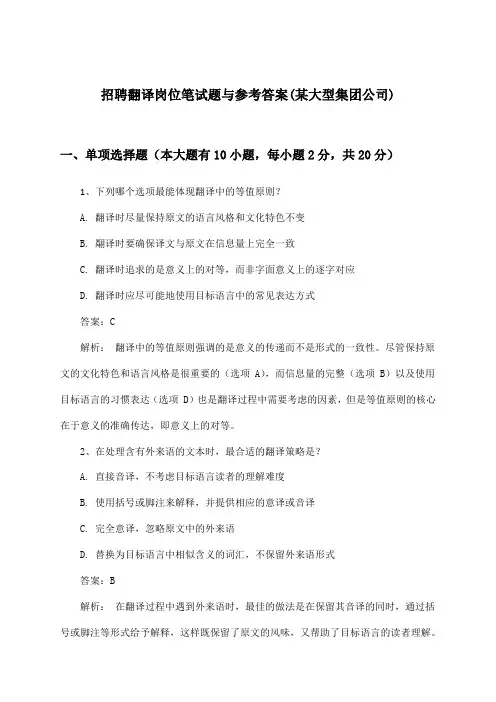

招聘翻译岗位笔试题与参考答案(某大型集团公司)一、单项选择题(本大题有10小题,每小题2分,共20分)1、下列哪个选项最能体现翻译中的等值原则?A. 翻译时尽量保持原文的语言风格和文化特色不变B. 翷译时要确保译文与原文在信息量上完全一致C. 翻译时追求的是意义上的对等,而非字面意义上的逐字对应D. 翻译时应尽可能地使用目标语言中的常见表达方式答案:C解析:翻译中的等值原则强调的是意义的传递而不是形式的一致性。

尽管保持原文的文化特色和语言风格是很重要的(选项 A),而信息量的完整(选项 B)以及使用目标语言的习惯表达(选项 D)也是翻译过程中需要考虑的因素,但是等值原则的核心在于意义的准确传达,即意义上的对等。

2、在处理含有外来语的文本时,最合适的翻译策略是?A. 直接音译,不考虑目标语言读者的理解难度B. 使用括号或脚注来解释,并提供相应的意译或音译C. 完全意译,忽略原文中的外来语D. 替换为目标语言中相似含义的词汇,不保留外来语形式答案:B解析:在翻译过程中遇到外来语时,最佳的做法是在保留其音译的同时,通过括号或脚注等形式给予解释,这样既保留了原文的风味,又帮助了目标语言的读者理解。

直接音译(选项 A)可能会造成理解障碍;完全意译(选项 C)和替换为相似含义词汇(选项 D)则可能丢失原文的文化信息。

3、题干:在翻译工作中,以下哪个术语指的是将源语言信息转换成目标语言信息的过程?A. 翻译技巧B. 翻译过程C. 翻译策略D. 翻译理论答案:B解析:选项B“翻译过程”指的是将源语言信息转换成目标语言信息的过程。

翻译技巧(A)指的是在翻译过程中使用的方法和技巧;翻译策略(C)是指翻译者在翻译过程中采取的策略和计划;翻译理论(D)则是关于翻译现象的理论体系。

4、题干:在以下翻译错误中,哪种情况属于“直译”错误?A. 将“苹果”直译为“apple”B. 将“红色”直译为“red”C. 将“天上的星星”直译为“stars in the sky”D. 将“时间就是金钱”直译为“time is money”答案:D解析:选项D“时间就是金钱”直译为“time is money”属于“直译”错误。

For three hundred years, science and scientific technology had an unblemished and justified reputation as a wonderful adventure, pouring out practical benefits, and liberating the spirit from the errors of superstition and traditional faith. During this 法century they have finally been the only generally credited system of explanation and problem-solving. Yet in our generation they have come to seem to many as essentially inhuman, abstract, regimenting, hand-in-glove with Power and even diabolical.

The immediate reasons for this shattering reversal of values are fairly obvious. Hitler's ovens and his other experiments in eugenics, the first atom bombs and their frenzied subsequent developments, the deterioration of the physical environment and the destruction of the biosphere, the catastrophes impending over the cities because of technological failures and psychological stress. Innovations yield diminishing returns in enhancing life. And instead of rejoicing, there is now widespread conviction that beautiful advances in genetics, surgery, computers, rocketry or atomic energy will surely only increase human woe.

Often it is clear that a technology has been oversold, like the cars. Then even though the public, seduced by advertising, wants more, technologists must balk, as any professional does when his client wants what isn't good for him. Yet we are now repeating the same self- defeating congestion with the planes and airports: the more the technology is oversold, the less immediate utility it provides, the greater the costs, and the more damaging the remote effects. As this becomes evident, it is time for technologists to confer with sociologists and economists and ask deeper questions. Is so much travel necessary? Are there ways to diminish it? However, the recent history of technology has consisted largely of a desperate effort to remedy situations caused by previous over-application of technology.

Currently, perhaps the chief moral criterion of a philosophic technology is modesty, having a sense of the whole and not obtruding more than a particular function warrants. Immodesty is always a danger of free enterprise, but when the same disposition is financed by big corporations, technologists rush into production with neat solutions that swamp the environment. This applies to packaging products and disposing of garbage, to freeways that bulldoze neighbourhoods, high-rises that destroy landscape, wiping out a species for a passing fashion, strip mining, scrapping an expensive machine rather than making a minor repair, draining a watershed for irrigation because the cultivable land has been covered by asphalt.

Since we are technologically overcommitted, a good general maxim in advanced countries at present is to innovate in order to simplify the technical system, but otherwise to innovate as sparingly as possible. Every advanced country is over-technologized; past a certain point, the quality of life diminishes with new "improvements.” Yet no country is rightly technologized, making efficient use of available techniques. There are ingenious devices for unimportant functions, stressful mazes for essential functions, and drastic dislocation when anything goes wrong, which happens with increasing frequency. To add to the complexity, the mass of people tend to become incompetent and dependent on repairmen—indeed, unrepairability except by experts has become a desideratum of industrial design.

In such a crisis, it will not be sufficient to simply solve problems of transportation, desalinization, urban renewal, garbage disposal, and cleaning up the air and water. It is necessary to alter the entire relationship of science, technology and social needs both in men's minds and in fact. This involves changes in the organization of science, in scientific education, and in the kinds of men who make scientific decisions.。