植物功能基因组学的发展现状16页PPT

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:1.83 MB

- 文档页数:16

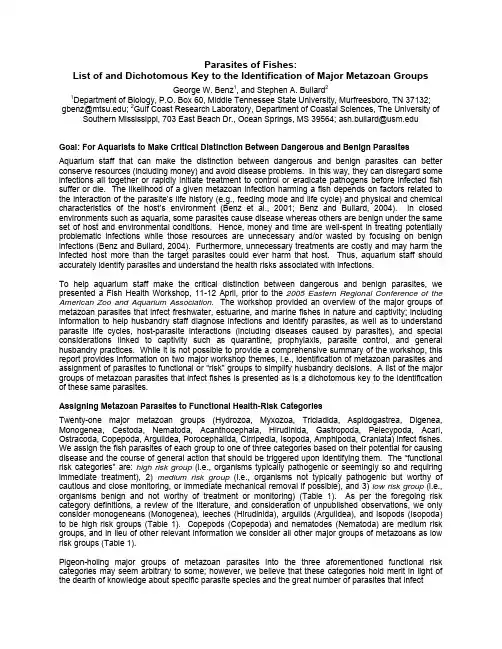

Parasites of Fishes:List of and Dichotomous Key to the Identification of Major Metazoan GroupsGeorge W. Benz1, and Stephen A. Bullard21Department of Biology, P.O. Box 60, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 37132; gbenz@; 2Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, Department of Coastal Sciences, The University of Southern Mississippi, 703 East Beach Dr., Ocean Springs, MS 39564; ash.bullard@Goal: For Aquarists to Make Critical Distinction Between Dangerous and Benign Parasites Aquarium staff that can make the distinction between dangerous and benign parasites can better conserve resources (including money) and avoid disease problems. In this way, they can disregard some infections all together or rapidly initiate treatment to control or eradicate pathogens before infected fish suffer or die. The likelihood of a given metazoan infection harming a fish depends on factors related to the interaction of the parasite’s life history (e.g., feeding mode and life cycle) and physical and chemical characteristics of the host’s environment (Benz et al., 2001; Benz and Bullard, 2004). In closed environments such as aquaria, some parasites cause disease whereas others are benign under the same set of host and environmental conditions. Hence, money and time are well-spent in treating potentially problematic infections while those resources are unnecessary and/or wasted by focusing on benign infections (Benz and Bullard, 2004). Furthermore, unnecessary treatments are costly and may harm the infected host more than the target parasites could ever harm that host. Thus, aquarium staff should accurately identify parasites and understand the health risks associated with infections.To help aquarium staff make the critical distinction between dangerous and benign parasites, we presented a Fish Health Workshop, 11-12 April, prior to the 2005 Eastern Regional Conference of the American Zoo and Aquarium Association. The workshop provided an overview of the major groups of metazoan parasites that infect freshwater, estuarine, and marine fishes in nature and captivity; including information to help husbandry staff diagnose infections and identify parasites, as well as to understand parasite life cycles, host-parasite interactions (including diseases caused by parasites), and special considerations linked to captivity such as quarantine, prophylaxis, parasite control, and general husbandry practices. While it is not possible to provide a comprehensive summary of the workshop, this report provides information on two major workshop themes, i.e., identification of metazoan parasites and assignment of parasites to functional or “risk” groups to simplify husbandry decisions. A list of the major groups of metazoan parasites that infect fishes is presented as is a dichotomous key to the identification of these same parasites.Assigning Metazoan Parasites to Functional Health-Risk CategoriesTwenty-one major metazoan groups (Hydrozoa, Myxozoa, Tricladida, Aspidogastrea, Digenea, Monogenea, Cestoda, Nematoda, Acanthocephala, Hirudinida, Gastropoda, Pelecypoda, Acari, Ostracoda, Copepoda, Argulidea, Porocephalida, Cirripedia, Isopoda, Amphipoda, Craniata) infect fishes. We assign the fish parasites of each group to one of three categories based on their potential for causing disease and the course of general action that should be triggered upon identifying them. The “functional risk categories” are: high risk group (i.e., organisms typically pathogenic or seemingly so and requiring immediate treatment), 2) medium risk group (i.e., organisms not typically pathogenic but worthy of cautious and close monitoring, or immediate mechanical removal if possible), and 3) low risk group (i.e., organisms benign and not worthy of treatment or monitoring) (Table 1). As per the foregoing risk category definitions, a review of the literature, and consideration of unpublished observations, we only consider monogeneans (Monogenea), leeches (Hirudinida), argulids (Argulidea), and isopods (Isopoda) to be high risk groups (Table 1). Copepods (Copepoda) and nematodes (Nematoda) are medium risk groups, and in lieu of other relevant information we consider all other major groups of metazoans as low risk groups (Table 1).Pigeon-holing major groups of metazoan parasites into the three aforementioned functional risk categories may seem arbitrary to some; however, we believe that these categories hold merit in light of the dearth of knowledge about specific parasite species and the great number of parasites that infectTable 1. Classification and common names of metazoan groups that include parasites of fishes.1 Bold entries indicatemajor groups of taxa presented in the identification key provided in the text and risk assignments mentioned in the text.Asterisks indicate groups whose membership is entirely parasitic.Classification— common name(s) (functional assignment)Kingdom Animalia— animalsPhylum Cnidaria— cnidariansClass Hydrozoa— hydrozoans (low risk group)Class Myxozoa*— myxozoans, myxosporidians (low risk group)Phylum Platyhelminthes— flatwormsSuperclass Turbellaria— turbellariansOrder Tricladida— triclads, turbellarians (medium risk group)Superclass Cercomeria*Class Aspidogastrea*— aspidogastreans, soleworms, aspidobothreans, aspidogastrids (low risk group)Class Digenea*— digeneans, flukes, digenes, digenetic trematodes (low risk group)Class Monogenea*— monogeneans, monogenoideans, monogenes, monogenetic trematodes (high risk group)Class Cestoda*— cestodes, cestoideans: gyrocotylideans and eucestodes, tapeworms (low risk group) Phylum Nematoda— nematodes, roundworms, threadworms (medium risk group)Phylum Acanthocephala*— acanthocephalans, spiny-headed worms (low risk group)Phylum Annelida— annelids, segmented wormsOrder Hirudinida— true leeches (high risk group)Phylum Mollusca— molluscsClass Gastropoda— gastropods, snails (low risk group)Class Pelecypoda— bivalves, clams, mussels, glochidia (larvae of many unionoids, Unionoidae) (low risk group)Phylum Arthropoda— arthropodsSubphylum Uniramia— uniramiansSubclass Acari— mites (low risk group)Subphylum Crustacea— crustaceansClass Maxillopoda— maxillopodansSubclass Ostracoda— ostracods, seed shrimp (low risk group)Subclass Copepoda— copepods (medium risk group but see comments in text regarding anchor worms, sea lice, and gill maggots)Subclass Branchiura*— branchiuransOrder Argulidea*— fish lice (high risk group)Order Porocephalida*— pentastomes, tongue worms (low risk group)Subclass Cirripedia— barnacles (low risk group)Class Malacostraca— malacostracansOrder Isopoda— isopods (high risk group)Order Amphipoda— amphipods (low risk group)Phylum Chordata— chordatesSubphylum Craniata— craniatesSuperclass Agnatha— jawless fishesClass Myxini— hagfishes, slime eels (low risk group)Class Cephalaspidomorphi— lampreys (low risk group)Superclass Gnathostomata— jawed vertebratesClass Chondrichthyes— chondrichthyans (low risk group)Class Actinopterygii— ray-finned fishes (low risk group)1 A universally-accepted classification scheme for taxa (groups) within Animalia does not exist. The classification used here is amixture of several widely accepted schemes.fishes. Nevertheless, it should be noted that not all members of a major metazoan group pose an identical health risk to hosts and thus species-level information regarding some parasites or environmental information important to the progression of particular infections may require case-specific considerations of health risk. For example, some low risk parasites might require control under special circumstances. Unfortunately, the myriad of circumstances under which this may occur are beyond the scope of this report. Hence, husbandry staff and veterinarians should confer with parasitologists when assignment to a particular risk category is in question. Generally, we recommend that only high risk groups and several lower-taxonomic groups of pathogenic copepods such as anchor worms (Lernaea spp.) and some species of sea lice (Caligidae) and gill maggots (Lernaeopodidae) be addressed with eradication or control protocols aimed at prophylaxis. Nevertheless, although no compelling evidence supports the routine control of any other major metazoan group for health purposes, some parasites (e.g., some ectoparasitic copepods) are large and their presence may upset patrons at public aquariums orthey can be associated with unsightly lesions that may facilitate disease caused by opportunistic pathogens. Given that these parasites are usually easy to mechanically remove or eradicate using various parasiticides, we encourage their elimination when this poses minimal risk to the host.Identifying Metazoan Parasites of FishesAlthough parasite identification is a prerequisite for effective disease control, many metazoan parasites of fishes frequently are misidentified because they are small, anatomically complex, and delicate organisms that require extensive preparation techniques. With that in mind and to help reduce the frequency of misidentifications, we developed an identification key to the metazoan parasites of fishes that is user-friendly in the sense that it requires very little preparation of study samples and the use of a low-magnification microscope only. Although the key is geared for identifying adult parasites, it also facilitates the identification of many parasite larvae and juveniles. Parasite groups are not arranged by ancestry within the key, and some parasite characteristics used in the key pertain to species that infect fishes only. Although one can identify a parasite to a major metazoan group by using this key, species-, genus- or family-level identifications depend on reference to scientific literature (e.g., peer-reviewed or synoptic literature) or assistance from a taxonomic authority. The risk group assignment for each major group presented in the key is listed in Table 1. Readers that are curious about parasite diseases, prophylaxis, and control may benefit by reading Benz et al. (2001) and Benz and Bullard (2004) and the cited literature therein.Dichotomous Identification Key to Major Groups of Metazoans that Infect FishesIllustrations correspond to key couplets immediately above them, and all features or organismsunderlined in couplets are illustrated. Illustrations depict typical examples but not all variations.1. a. Organism (one species, Polypodium hydriforme ) only associated with eggs of sturgeon andpaddlefish (Acipenseriformes); infected fish eggs enlarged and containing parasite in form of macroscopic, light-colored stolon or microscopic planula; stolon with tentacles that may emergefrom egg…………………………………………………………………………………………..Hydrozoab. Organism not as described immediately above but may be associated with eggs of fishes (2)2. a. Organism appearing as a microscopic, symmetrical spore; spores may reside outside of or within cyst-like capsules (plasmodia); individual spores typically microscopic and amassed; spores maybe within or outside of plasmodium and they may or may not be encapsulated by host....Myxozoab. Organism visible to naked eye (may nonetheless be tiny and larvae may be microscopic); may ormay not be aggregated into clusters of individuals……………………………………………………..3 3. a. Organism a fish; endoskeleton made of cartilage or bone……………………………………..Craniatab. Organism not a fish; endoskeleton of cartilage or bone lacking………………………………………...4 tentacleplasmodia spore stolen freed from sturgeon egg hagfish lamprey cookiecutter shark snubnose eel4.a. Organism a snail that possess a snail shell………………………………………………….Gastropodab. Organism lacking snail shell (5)5. a. Organism a tiny bivalve with two shells that clamp shut on host gills, fins or general body surface;lacking jointed appendages; may be encysted…………………………………………….Pelecypodab. Organism not a tiny bivalve with two shells (6)6. a. Organism worm-like; lacking exoskeleton articulated with segmented appendages…………………7 b. Organism with exoskeleton articulated with segmented appendages; appendages may bemicroscopic………………………………………………………………………………………………..18 7. a. Organism segmented along main body axis (segmentation may be nonexistent or unapparent insome larval tapeworms) (8)b. Organism not segmented along main body axis (10)8. a. Organism with anterior sucker surrounding oral opening; digestive tract and blind posterior suckerpresent; with or without distinctive eyespots………………………..……………………….Hirudinidab. Organism without anterior sucker and blind posterior sucker; digestive tract mayor may not be present (9)9. a. Organism with digestive tract; four anterior claws longitudinally arranged as two pairs; may beencysted…….………………………………………………………………………………Porocephalidashellanterior suckerposterior suckeroral openinganterior clawsshell eyespotsb. Organism lacking gut; may have anterior hooks or tentacles with spines but not as describedabove; larvae may be encysted or encapsulated.......................segmented members of Cestoda10. a. Organism with spiny proboscis (possibly inverted) at anterior end of body; lackingdigestive tract........................................................................................Acanthocephala b. Organism without spiny proboscis (11)11. a. Organism lacking gut……………………….……Caryophyllideae and Spathebothriidea (Cestoda)b. Organism with digestive tract (12)12. a. Organism with more than two suckers or rugae (13)b. Organism with two or fewer sucker-like attachment organs; if circular or disc-like the attachmentorgan may be subdivided (14)hookstentaclesproboscis proboscisscolexstrobilaneck13. a. Organism with suckers (rugae) arranged in one to several ranks along longitudinalbody axis……………………………………………………………………………………Aspidogastreab. Organism with posterior attachment organ (haptor) having three or four pairs of suckers with hooksand associated sclerites……………………….....……………….Polyopisthocotylea (Monogenea)14. a. Organism with attachment organ occupying extreme posterior end of body (15)b. Organism having an attachment organ not occupying extreme posterior-most end of body, i.e., theattachment organ is subterminal (17)15. a. Organism with haptor (each circumscribed below) in form of simple saucer-like sucker with hooksor lappet-like sucker without hooks............................................Monopisthocotylea (Monogenea)b. Organism with poorly defined, indiscrete posterior attachment organ that lacks hooks and is not inform of a well-delineated posterior attachment organ such as that depicted for 15a (16)rugaesuckerseggegghookssclerites16. a. Organism typically with eyespots; external body surface ciliated; having complete digestive tract;may be embedded……………………………………………………………...……………….Tricladidab. Organism lacking complete digestive tract, eyespots and external cilia.....Gyrocotylidea (Cestoda)17. a. Organism with two suckers (an oral sucker and acetabulum)1; monoecious; typically capable ofextension with non-sigmoidal, worm-like movements; larvae of many species encysted in flesh,gill, eye (may or may not be encysted), brain, or heart of fishes………………….….……...Digeneab. Organism lacking suckers; dioecious; body tube-like and cuticularized; movement via sigmoidalwriggling and thrashing; larvae encysted or encapsulated or not; adult with lips and tail; adulttypically not encapsulated……………………………………………………………………...Nematoda 1Except sanguinicolids (Sanguinicolidae) that lack a ventral sucker (“acetabulum”) and obvious oral sucker.oral suckeracetabulumtail anteriorlipseyespots18. a. Organism with three or four pairs of walking legs; all appendages unbranched; pedipalps present;body compact and possibly tick-like; larvae may be encapsulated……………………………...Acarib. Organism with biramous crawling appendages; body not tick-like; may penetrate host (20)19. a. Organism bivalved, with laterally compressed carapace enclosing head, body, and mostappendages.....................................................................................................................Ostracodab. Organism lacking bivalve carapace as described immediately above (21)20. a. Organism sessile; attached by peduncle that may or may not be embedded……………...Cirripediab. Organism not attached to host by peduncle (21)21. a. Organism lacking compound eyes, but may possess obvious non-compound eyes……..Copepodab. Organism with compound eyes (22)pedipalpwalking legsbarnacle on fish22. a. Organism with dorsoventrally compressed body; four pairs of biramous, cirriform legs; somespecies (genus Argulus ) with two conspicuous sucker-like appendages on ventral bodysurface……………………………………………………………………………………………Argulideab. Organism lacking sucker-like appendages (23)23. a. Organism with laterally compressed body…………...………………………………………Amphipodab. Organism with dorsoventrally compressed body or uncompressed body…………………….IsopodaReferencesBenz, W. W., S. A. Bullard, and A. D. M. Dove. 2001. Metazoan parasites of fishes: synoptic information and portal to the literature for aquarists. Pp. 1-15. In: Regional Conference Proceedings 2001. Anonymous (ed.). American Zoo and Aquarium Association, Silver Spring, MD.Benz, G. W., and S. A. Bullard. 2004. Metazoan parasites and associates of chondrichthyans with emphasis on taxa harmful to captive hosts. Pp. 325-416. In: The elasmobranch husbandry manual: captive care of sharks, rays and their relatives. Smith, M., D. Warmolts, D. Thoney, and R. Hueter (eds.). Special Publication, Ohio Biological Survey, Columbus, OH. suckerscirriform legs。

植物基因组研究的现状与前景植物基因组研究是一门涉及植物遗传信息的学科,通过对植物基因组的理解,可以深入研究植物的进化、功能和形态特征,从而推动农业、生物技术和生态保护领域的发展。

随着高通量测序技术的不断发展和基因组学研究的兴起,植物基因组研究已经取得了很多重要的突破。

本文将介绍植物基因组研究的现状和前景,并展望未来的发展方向。

目前,植物基因组研究已经取得了很多重要的进展。

通过测序和分析多个植物基因组,我们已经了解了植物基因组的组成和结构。

例如,2024年,植物学家成功测序了拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)的基因组,这是第一个全基因组已知的植物。

这项研究为我们提供了了解植物演化和适应环境的基础知识。

此外,研究人员还测序了其他重要的作物基因组,如水稻、小麦、玉米和大豆等,这些研究为改良农作物品质和产量提供了重要的信息。

在现代植物基因组研究中,高通量测序技术是最重要的工具之一、高通量测序技术的发展使得我们能够更快速、更经济地测序整个植物基因组。

此外,通过比较多个植物基因组的序列,我们可以发现共有的基因和结构,揭示它们之间的关联和功能。

另一个重要的研究方向是功能基因组学。

功能基因组学研究主要关注基因组中的功能基因和其在植物生理和发育中的作用。

通过分析植物基因的表达模式和突变体,我们可以识别和研究与植物重要生理过程相关的基因。

例如,通过比较表达模式,我们可以了解哪些基因在植物对逆境环境的适应中起关键作用。

此外,通过制作功能基因组饼图,我们可以将基因组中的基因分成不同的功能分类,了解每个功能类别的基因在植物生长发育中的作用。

未来,植物基因组研究仍将有很大的发展空间。

首先,随着测序技术的不断进步,我们将能够更快地测序更多的植物基因组。

这将使我们能够更好地了解植物基因组的差异和演化。

此外,随着单细胞测序和单细胞组学的发展,我们将能够更好地了解不同的细胞类型和组织在植物发育和功能中的作用。

此外,植物基因组研究还将与其他学科进行跨学科的合作,如计算机科学、生物信息学和生物化学等,以提高数据分析和解释的能力。

植物基因组学的发展随着科技的不断发展和进步,植物基因组学的发展也越来越迅速,成为了生命科学的一个重要研究领域之一。

在过去的几十年里,人们通过对植物基因组的研究,理解了许多重要的基因调控机制和代谢途径,为农业的发展和保护自然资源提供了很多有益的信息和思路。

一、植物基因组学的历史植物基因组学的起源可以追溯到上世纪50年代,当时人们利用多种技术手段,对一些植物的基因组进行了初步的研究。

随着DNA测序技术,PCR技术等分子生物学技术的发展,在20世纪80年代,研究人员已经能够对一些植物基因组进行初步的测序,并对其进行一定的分析。

但是在那个时期,植物基因组的测序和分析还面临很多困难和挑战,研究进展缓慢。

随着21世纪的到来,生物技术发展的步伐越来越快,植物基因组学的研究也得到了快速的发展。

2000年,人类基因组的测序工作成功完成,这对植物基因组研究的推进起到了很好的促进作用。

2007年,米国科学家联合会发起了植物基因组倡议,旨在对所有重要的经济、生命和环境作用的植物进行基因组测序和分析,从而加快该领域的发展。

二、植物基因组学的意义和价值植物是全球生物多样性的重要组成部分,对生态环境的保持和生物多样性的维护有着不可替代的作用。

同时,植物作为人类的食物来源和药物资源也有着重要的经济价值。

通过对植物基因组的深入研究,可以更好地理解植物生长发育的调控机制,对植物的改良和优化提供更加精确的基础数据。

此外,对植物基因组的研究也可以为生物多样性保护和生态环境改善提供有益的信息。

通过对不同植物基因组的比较和分析,可以更好地揭示不同物种之间的进化关系和适应性,为生物多样性的保护和维护提供更好的指导和帮助。

三、植物基因组学的发展现状和趋势目前,植物基因组研究的范围已经非常广泛,涉及到了许多不同的植物种类和方面。

一些经济作物和重要的食用植物的基因组已经被完整地测序和分析,如大豆、水稻、玉米、葡萄和小麦等,为植物育种、种植和农业生产提供了重要的支持和保障。

植物基因组学的研究现状和展望植物基因组学是研究植物基因组结构、功能和演化的学科。

通过对植物基因组的分析和解读,可以深入了解植物的遗传变异、适应性进化和重要农艺性状的形成机制。

同时,植物基因组学的研究也对植物种质资源的挖掘与利用、基因工程的发展以及农业的可持续发展具有重要意义。

本文将从植物基因组学的研究现状和展望两个方面进行论述。

一、植物基因组学的研究现状在过去的几十年中,随着基因测序技术的飞速发展,植物基因组学取得了重大突破。

首先,在基因组水平上,我们已经完成了许多植物的全基因组测序,如拟南芥、水稻、小麦等。

这些研究为我们深入了解植物的基因组特征和功能提供了重要依据。

此外,我们还发现了许多植物基因组的特殊结构和重要基因家族,如重复序列和转座子、抗逆基因家族等,这些都为后续的研究奠定了基础。

其次,在表观遗传学领域,植物基因组学的研究也在不断深入。

表观遗传学是研究基因组上不涉及DNA序列改变的遗传变异,它通过染色质修饰和非编码RNA等调控机制影响基因的表达。

研究表明,表观遗传学在植物的生长发育、抗逆性、营养代谢等方面起着重要作用。

在植物基因组学的研究中,我们已经揭示了许多植物表观遗传学修饰的调控机制,并与植物的重要农艺性状相关联。

此外,植物基因组学还涉及到功能基因组学的研究。

功能基因组学是通过基因敲除、表达调控和转基因等方法研究基因功能和基因网络的学科。

在植物基因组学中,我们已经成功地利用功能基因组学方法在拟南芥、水稻等模式植物上解析了许多基因的功能和基因调控网络。

这些研究为我们理解植物的发育机制、逆境响应和次生代谢合成提供了重要线索。

二、植物基因组学的研究展望随着高通量测序技术的不断完善和降低成本,植物基因组学的研究进入了全面发展的新阶段。

未来的研究中,我们可以预期以下几个方面的突破。

首先,我们将进一步完善植物基因组的测序和注释工作。

虽然目前已经完成了许多植物的全基因组测序,但其中仍存在一些缺失和错误,需要通过更加精确的技术和算法进行补充和校准。

植物基因组学研究的发展现状和前景展望植物基因组学研究是一个新兴的领域,它涉及到植物的基因组结构、基因功能、基因组表达和进化等方面。

这个领域在过去几十年里,得到了飞速的发展。

本文将介绍植物基因组学的发展现状和未来展望。

发展现状植物基因组学研究的起点可以追溯到20世纪60年代,当时科学家们刚刚开发出了分子生物学工具。

随着技术的改进和实验手段的不断完善,人们开始能够更加深入地了解植物与生俱来的基因组信息。

目前,已有许多关于植物基因组的研究成果,例如在植物基因工程、新基因的发现以及植物的生物学特性等方面。

下面将具体介绍植物基因组学研究的现状。

1. 基因组测序和分析随着高通量测序技术的不断革新,基因组测序和分析技术也大幅提高。

目前,已有许多植物基因组测序项目启动,其中大多数是全基因组测序。

例如水稻、拟南芥、玉米和小麦的基因组序列均已解析,这些数据大大促进了植物基因组研究。

此外,这些测序数据的分析能够更好地揭示基因的功能和演化历史等信息。

2. 基因组编辑技术的应用基因组编辑技术是指通过改变基因组序列来实现物种进化或遗传学上的功能变化的技术。

CRISPR/Cas 系统是一种经常被使用的基因组编辑技术,因为它不仅精准,而且操作简单。

近年来,植物基因组编辑的应用越来越广泛,例如用在提高作物产量、改善营养成分等方面。

基因组编辑技术的出现,将极大地促进植物基因组学的发展。

3. 遗传标记和基因关联分析遗传标记是指与某个性状相关的基因或序列标记,它们可用于进行遗传关联分析。

基因关联分析是一种用于研究基因与性状/生物过程之间关系的统计技术。

遗传标记和基因关联分析在研究植物基因组中的复杂特性方面发挥了重要作用。

未来展望植物基因组学研究的发展前景非常广泛。

下面讨论植物基因组学的未来展望。

1. 基于多组学的研究多组学研究是指综合不同类型数据,如基因组、转录组、蛋白组、代谢组和表观组学等,以便更全面地分析生物过程。

植物基因组学将越来越与多组学研究结合,这种研究方式将有力地推动植物基因组学的发展。