当代美国翻译理论

- 格式:doc

- 大小:55.50 KB

- 文档页数:12

当代美国翻译理论

!

当代美国翻译理论是研究理论翻译的一种重要流派,其派系延伸了达文西和维特根斯坦之研究成果。

特朗普认为,翻译越多某语言熟悉,其所表达文体也越接近,这种观点也被称为“内容之谬误”理论。

而在美国当代翻译理论看来,内容的完全承载不是主要的,自我表达也是翻译活动中的一个重要组成部分。

这里的自我表现,是指翻译者通过添加或转化文化符号或特有的口头表达等;充分发挥语种特色,从而使译文具有一定的文学魅力,这也就是所谓的“文体之全谱”理论。

从现代翻译理论中来看,今日的翻译与传统翻译有很大的不同。

今日的翻译理论不仅注重信息的传达,还强调了翻译者的风格与个性。

现在,在美国的高等教育领域,翻译学教学也已经不断引入当代翻译理论,着力培养学生认识翻译是一种艺术,需要融入自己的文化特色,把意思表达清楚,这种活跃理论,有助于装置文学翻译技能,从而帮助准备进入翻译行业的学生以及大众都能学到更多关于翻译艺术的知识。

美国翻译培训派(The American Translation Workshop)注重文学作品的翻译,其指导思想是翻译是一门艺术,培训班可以加强学生对文学、语言和诠释的认识和理解,进而通过翻译经验的交流提高翻译技艺和水平。

里查兹、庞德和威尔是该学派的主要代表。

里查兹(I. A. Richards)曾在哈佛大学创办阅读培训班,为翻译培训班提供了丰富的实践经验。

翻译培训班的宗旨是要使学生充分理解文本,达成正确而统一的反映和体验,并用完美的口、笔译形式再现或阐述这一体验。

其理论前提显然是文学作品有一个终极的、统一的意义。

只要通过适当的训练,掌握正确的方法,人们就能准确地理解原文。

翻译培训班的任务就是制定若干条款和程序,排除一切妨碍正确理解的障碍。

庞德(Ezra Pound)认为文学作品刻意塑造的是形象,而非内容或意义。

在翻译中译者应注重的不是所描写的事物,而是描述的过程和语言的形式与能量(energy)。

译者如同艺术家、雕刻家和书法家,应精确地再现细节、词语、片段和整个意象。

作品真正的灵魂常常蕴藏于“一瞥或一瞬之间”。

威尔(Frederic Will)认为文学作品是表现自我、统一而连贯的形式,能赋予我们洞悉事物本质的能力。

语际交际和翻译之所以可能,是因为人类的体验和情感有一个共核。

在翻译中他强调直觉的作用,认为在诗歌翻译中,有天赋的翻译家即使不精通原作的语言也同样可以再现原作的精髓与本质。

他认为,所谓精髓和本质就是作品的能量和冲量(thrust),译文不仅是原作的补充和延伸,而且使原作获得新的生命,勃发出新的生机。

美国翻译培训派对人类主观无意识的研究、强调文学翻译中的“创造性转换(creative transposition)”、注重文学作品的文学价值以及在译文忠实的标准问题上提出的新颖观点等,都对其后的翻译学派产生了巨大影响。

翻译科学派(The Science of Translation)亦称翻译语言学派,包括布拉格学派、伦敦学派、美国结构学派、交际理论派和俄国语言学派。

托尔曼和他的《翻译艺术》赫伯特. 库欣.托儿曼(Herbert Cushing Tolman)的《翻译艺术》(Art of Translation)发表于1901年。

它是美国理论史上的第一部专著,属于西方传统理论研究的范畴。

在该书中,托儿曼谈到了翻译的本质,翻译的过程,翻译的标准和译作的风格等问题。

一.翻译的本质托儿曼谈的是文学翻译。

首先,他认为,翻译是一种艺术。

翻译家应是艺术家,就像雕塑家,画家和设计师一样。

翻译的艺术,贯穿于整个翻译过程之中,即理解和表达的过程之中。

托儿曼认为,翻译艺术与绘画艺术最相近。

二.翻译的过程作者指出:“翻译的心理过程由两部分组成:第一,我们必须掌握原文作者的思想;第二,我们必须用译文的语言把原文作者的思想表达出来。

”这里,托儿曼像一般传统的理论家一样,把翻译的过程分为理解和表达两个阶段。

1.理解:托儿曼强调,必须从原文的观点理解原文,才能掌握原作的精神。

他说,译者只有从原文的观点出发去阅读,才能使自己沉浸在原文的思想和感情的激流之中,才能领会原文的精神实质。

他把译者阅读原文的过程,比作画家落笔前的构思过程。

画家只有知道自己要画什么,才会动手去画。

他不会随便去画一丛灌木,然后再画一颗树,接着再画一块石头,而是头脑里首先有了整幅风景的轮廓,心领神会,然后才动手去画。

翻译艺术也正是这样。

译者只有透彻地理解了原作的思想之后,才应动笔翻译。

(泰特勒也把翻译比作画画,但泰特勒强调的是翻译的困难,因为,画家临摹可用相同的材料,翻译家模仿却用的是不同的语言。

)2.表达:托儿曼指出: “译者对原文的精神领会越沈,就越感到自己责任之重大,也越来越深刻地理解到传达原作结构的精神实质之困难。

”他说:“翻译要能在英语读者或听众中引起像原文读者或听众所感受的同样的感情。

”他也意识到,译作要像原作一样,在译文读者中产生原作在原文读者中完全一样的效果是不可能的。

关于这一点,他又把翻译比作绘画艺术。

当代美国翻译理论当代美国翻译理论(转)2009-10-10 23:00郭建中编著,当代美国翻译理论,:教育,2000年4月。

一、赫伯特·库欣·托尔曼(Herbert Cushing Tolman)作者简介:赫伯特·库欣·托尔曼(Herbert Cushing Tolman)()“翻译的心理过程由两部分组成:第一,我们必须掌握原文作者的思想;第二,我们必须用译文的语言把原文作者的思想表达出来。

”“阅读是一回事,翻译是另一回事。

”译者只有从原文的观点出发去阅读,才能使自己沉浸在原文的思想和感情的激流之中,才能领会原文的精神实质。

“译者对原文的精神领会越深,就越感到自己责任之重大,也越来越深地理解到传达原作结构的精神实质之困难。

”“翻译要能在英国读者或听众中引起像原文读者或听众所感受的同样的感情。

”没有一个画家能完美地重现自然风景。

最好的画家并不是用与自然同样的颜色表现自然景色中的每一个细节;最好的画家应该是有感于壮丽的自然景色,并认识到绘画艺术的局限性,然后使自己的画尽可能地接近大自然的美景。

最好的翻译家也一样,他并不是在英语中精确地复制原作——因为这是不可能的——他只能使自己的译作尽可能地接近原作。

“翻译并不是把一种外语的单词译成母语(英语),而应该是原文中感情、生命、力度和精神的蜕变。

”我们既要忠实于原作的优美之处,也要忠实于原作的不足之处。

翻译不是解释。

“如果原作趴地蠕动,译作不可腾空翱翔。

”译文必须是地道的英语。

二、C·H·库利(C. H. Conley)尽管一般认为翻译经典著作有助于文化和自由思想的传播和发展,但16世纪英国经典著作的翻译反而助长了反动的社会和文化专制主义。

三、亨利·伯罗特·莱思罗普(Henry Burrowes Lathrop)16世纪英国所翻译的希腊罗马经典著作和我们今天所熟悉的完全不一样。

当代美国翻译理论当代美国翻译理论(转)2009-10-10 23:00郭建中编著~当代美国翻译理论~武汉:湖北教育出版社~2000年4月。

一、赫伯特?库欣?托尔曼(Herbert Cushing Tolman)作者简介:赫伯特?库欣?托尔曼(Herbert Cushing Tolman),,“翻译的心理过程由两部分组成:第一~我们必须掌握原文作者的思想,第二~我们必须用译文的语言把原文作者的思想表达出来。

”“阅读是一回事~翻译是另一回事。

”译者只有从原文的观点出发去阅读~才能使自己沉浸在原文的思想和感情的激流之中~才能领会原文的精神实质。

“译者对原文的精神领会越深~就越感到自己责任之重大~也越来越深地理解到传达原作结构的精神实质之困难。

”“翻译要能在英国读者或听众中引起像原文读者或听众所感受的同样的感情。

” 没有一个画家能完美地重现自然风景。

最好的画家并不是用与自然同样的颜色表现自然景色中的每一个细节,最好的画家应该是有感于壮丽的自然景色~并认识到绘画艺术的局限性~然后使自己的画尽可能地接近大自然的美景。

最好的翻译家也一样~他并不是在英语中精确地复制原作——因为这是不可能的——他只能使自己的译作尽可能地接近原作。

“翻译并不是把一种外语的单词译成母语,英语,~而应该是原文中感情、生命、力度和精神的蜕变。

”我们既要忠实于原作的优美之处~也要忠实于原作的不足之处。

翻译不是解释。

“如果原作趴地蠕动~译作不可腾空翱翔。

”译文必须是地道的英语。

二、C?H?库利(C. H. Conley)尽管一般认为翻译经典著作有助于文化和自由思想的传播和发展~但16世纪英国经典著作的翻译反而助长了反动的社会和文化专制主义。

三、亨利?伯罗特?莱思罗普(Henry Burrowes Lathrop)16世纪英国所翻译的希腊罗马经典著作和我们今天所熟悉的完全不一样。

我们今天所认为的希腊罗马经典著作~他们没有翻译。

恰恰相反~他们所认为的经典著作~在今天~我们认为是不重要的~因此也并不熟悉。

翻译学必读1语文和诠释学派二十世纪之前的翻译理论被纽马克(1981)称为翻译研究的‘前语言学时期’,人们围绕‘word-for-word’和‘sense-for-sense’ 展开激烈的讨论,核心是‘忠实’,‘神似’和‘真理’。

典型的代表有John Dryden, Tytler等,而Barnard, Steiner等人则是在他们的基础上进一步发展。

2语言学派Jacobson(1959)提出意义对等的问题,随后的二十多当年,学界围绕这个问题进行了研究。

奈达(1969)采取了转换语法模式,运用“科学(奈达语)”的方法来分析他翻译《圣经》过程中的意义处理问题。

奈达提出的形式对等说、动态对等说和等效原则都是将注意力集中在受众一方。

纽马克信奉的是语义翻译和交际翻译,即重视翻译中的语义和交际方面。

3话语分析Discourse Analysis(critical discourse analysis批评话语分析functional discourse analysis功能语篇分析Discourse analysis theory话语分析理论Discourse Analysis for Interpreters翻译专业演说分析Pragmatics & Discourse Analysis语用学positive discourse analysis积极话语分析rhetorical or discourse analysis语篇分析Pragmatics and Discourse Analysis语用学Mediated discourse analysis中介话语分析二十世纪七十年代到九十年代,作为应用语言学领域的一个分支,话语分析经历了产生和发展壮大的过程,其理论背景来自(韩礼德)的系统功能语法。

今天,话语分析的方法已经逐步运用到翻译研究中。

House(1997)提出的翻译质量模型就是基于韩礼德的理论,他吸收了其中的语域分析方法;Baker(1992) 则为培养译员提供了话语分析和语用分析的范本;Hatim 和Mason(1997)将语域研究拓展到语用和符号学角度~4目的学派目的学派于二十世纪七、八十年代在德国兴起,是从静态的语言学、语言类型学中剥离出来的。

当代西方翻译理论流派评述及当代西方翻译理论家评述当代西方翻译理论流派评述一、美国翻译培训派1策德内斯:创立培训班的前提、2里查兹:翻译的理论基础、3庞德:细节翻译理论、4威尔:翻译的矛盾;二、翻译科学派1乔姆斯基:语言的“内在”结构、2奈达:翻译中的生成语法、3威尔斯:翻译的科学、4德国翻译理论的发展趋势;三、早期翻译研究派1俄国形式主义的影响2利维.米科和波波维奇3霍姆斯4勒非弗尔、布罗克与巴斯奈特;四、多元体系派1传统语言学和文学界限的瓦解、2通加诺夫:文学的演变、3佐哈尔:系统内部文学的联系、4图里:目标系统;五、解构主义派:1福科:解构原文、2海德格尔:重新认识命名、3德里达:系统的解构主义理论4解构主义理论的影响5解构与创译当代西方翻译理论家评述1奈达(三个发展阶段、对等概念、逆转换理论)、2卡特福德(翻译的语言学、翻译的界定与分类、翻译等值的条件与可译性)、3威尔斯(翻译是一门科学、翻译是交际过程、翻译方法的定义与分类、文本类型与翻译原则)、4纽马克(语义结构、翻译原则、文本类型与翻译方法)、5斯坦纳(翻译是理解的过程、语言的可译性、翻译的步骤)、6巴尔胡达罗夫(翻译的定义及实质、翻译理论的定位、语义与翻译、翻译的层次)、7费道罗夫、v.科米萨罗夫的翻译理论、8穆南(语言与意义、“世界映象”理论与可译性、意义交流与翻译、可译性与限度)、9塞莱丝柯维奇和法国释意理论(释意的基本问题、翻译程序与评价标准、释意理论与翻译教学)。

另外当代西方翻译理论也典型地体现在后殖民主义与女性主义及其它以“解构为方法论”,以及以对“权力话语”的关注为重点的各种翻译理论,代表性的译论家有西门、巴巴拉.哥达德、凯特.米勒特、艾德里安.里奇、玛丽.艾尔曼、桑德拉.吉尔伯特、苏桑.格巴与埃莱娜.西苏、罗宾逊、巴斯奈特、特里弗蒂、韦努蒂、尼南贾纳、斯皮瓦克、霍米.巴巴、根茨乐、玛丽亚.提莫志克、本雅明、德里达、保尔.德曼、欧阳桢、L。

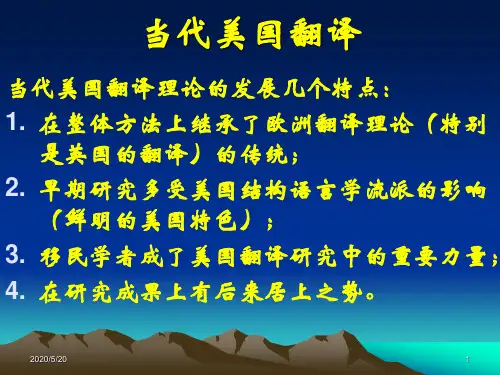

读郭建中《当代美国翻译理论》作者:宗蔚婷来源:《科教导刊》2010年第20期摘要美国的翻译研究,开始较迟,历史较短。

最早开始于20世纪初,二次大战后逐步有所发展,到了60年代之后,则取得了长足的进步。

郭建中编著的《当代美国翻译理论》系统、科学地向我们介绍了当代美国翻译研究发展史及重要翻译理论。

关键词美国翻译翻译理论中图分类号:H315.9文献标识码:A20世纪60年代初,美国大学中还没有翻译研讨班或研究中心,也没有翻译研究中心,没有文学翻译工作者的组织,也没有翻译或翻译研究的专门刊物。

埃德温·根茨勒在《当代翻译理论》中提到,60年代起,文学翻译在美国才开始受到公众和学术界的重视。

保罗·恩格尔于1964年在衣阿华大学开设了第一个翻译研讨班。

第二年,福特基金会拨款给在奥斯丁德克萨斯大学成立全国翻译中心。

1965年出版了第一本《现代诗翻译》的杂志。

1968年,全国翻译中心出版了第一期翻译研究杂志《得洛斯》。

从此,文学翻译在美国文化中取得了小小的一席之地。

70年代之后,美国的翻译和翻译理论继续得到发展。

好几所大学开始设翻译课和翻译研讨班。

由于翻译和翻译研究的发展,美国文学翻译工作者协会(American literary translators association)于70年代末成立,并出版了《翻译》(tanslation)作为该组织的机关刊物。

1977年美国政府开始从全国人文科学基金中拨出专款资助文学翻译。

目前,美国已形成了三个有影响的翻译研究中心,即加利福尼亚的蒙特利国际学院、华盛顿特区的乔治城大学和宾厄姆顿的纽约州立大学。

所有这些,为美国翻译和翻译理论在80-90年代的蓬勃发展奠定了基础。

1 托尔曼和他的《翻译艺术》赫伯特库辛托尔曼的《翻译艺术》(Art of translation)发表于1901年,是美国翻译理论史上的第一部专著,属于西方传统翻译理论研究的范围。

所以我们可以说,美国的翻译研究开始于20世纪初。

美国翻译培训派(The American Translation Workshop)注重文学作品的翻译,其指导思想是翻译是一门艺术,培训班可以加强学生对文学、语言和诠释的认识和理解,进而通过翻译经验的交流提高翻译技艺和水平。

里查兹、庞德和威尔是该学派的主要代表。

里查兹(I. A. Richards)曾在哈佛大学创办阅读培训班,为翻译培训班提供了丰富的实践经验。

翻译培训班的宗旨是要使学生充分理解文本,达成正确而统一的反映和体验,并用完美的口、笔译形式再现或阐述这一体验。

其理论前提显然是文学作品有一个终极的、统一的意义。

只要通过适当的训练,掌握正确的方法,人们就能准确地理解原文。

翻译培训班的任务就是制定若干条款和程序,排除一切妨碍正确理解的障碍。

庞德(Ezra Pound)认为文学作品刻意塑造的是形象,而非内容或意义。

在翻译中译者应注重的不是所描写的事物,而是描述的过程和语言的形式与能量(energy)。

译者如同艺术家、雕刻家和书法家,应精确地再现细节、词语、片段和整个意象。

作品真正的灵魂常常蕴藏于“一瞥或一瞬之间”。

威尔(Frederic Will)认为文学作品是表现自我、统一而连贯的形式,能赋予我们洞悉事物本质的能力。

语际交际和翻译之所以可能,是因为人类的体验和情感有一个共核。

在翻译中他强调直觉的作用,认为在诗歌翻译中,有天赋的翻译家即使不精通原作的语言也同样可以再现原作的精髓与本质。

他认为,所谓精髓和本质就是作品的能量和冲量(thrust),译文不仅是原作的补充和延伸,而且使原作获得新的生命,勃发出新的生机。

美国翻译培训派对人类主观无意识的研究、强调文学翻译中的“创造性转换(creative transposition)”、注重文学作品的文学价值以及在译文忠实的标准问题上提出的新颖观点等,都对其后的翻译学派产生了巨大影响。

翻译科学派(The Science of Translation)亦称翻译语言学派,包括布拉格学派、伦敦学派、美国结构学派、交际理论派和俄国语言学派。

美国翻译培训派(The American Translation Workshop)注重文学作品的翻译,其指导思想是翻译是一门艺术,培训班可以加强学生对文学、语言和诠释的认识和理解,进而通过翻译经验的交流提高翻译技艺和水平。

里查兹、庞德和威尔是该学派的主要代表。

xx(I.A. Richards)曾在哈佛大学创办阅读培训班,为翻译培训班提供了丰富的实践经验。

翻译培训班的宗旨是要使学生充分理解文本,达成正确而统一的反映和体验,并用完美的口、笔译形式再现或阐述这一体验。

其理论前提显然是文学作品有一个终极的、统一的意义。

只要通过适当的训练,掌握正确的方法,人们就能准确地理解原文。

翻译培训班的任务就是制定若干条款和程序,排除一切妨碍正确理解的障碍。

庞德(Ezra Pound)认为文学作品刻意塑造的是形象,而非内容或意义。

在翻译中译者应注重的不是所描写的事物,而是描述的过程和语言的形式与能量(energy)。

译者如同艺术家、雕刻家和书法家,应精确地再现细节、词语、片段和整个意象。

作品真正的灵魂常常蕴藏于“一瞥或一瞬之间”。

威尔(FredericWill)认为文学作品是表现自我、统一而连贯的形式,能赋予我们洞悉事物本质的能力。

语际交际和翻译之所以可能,是因为人类的体验和情感有一个共核。

在翻译中他强调直觉的作用,认为在诗歌翻译中,有天赋的翻译家即使不精通原作的语言也同样可以再现原作的精髓与本质。

他认为,所谓精髓和本质就是作品的能量和冲量(thrust),译文不仅是原作的补充和延伸,而且使原作获得新的生命,勃发出新的生机。

美国翻译培训派对人类主观无意识的研究、强调文学翻译中的“创造性转换(creativetransposition)”、注重文学作品的文学价值以及在译文忠实的标准问题上提出的新颖观点等,都对其后的翻译学派产生了巨大影响。

翻译科学派(The Science of Translation)亦称翻译语言学派,包括布拉格学派、伦敦学派、美国结构学派、交际理论派和俄国语言学派。

《当代美国》翻译实践报告的开题报告开题报告:题目名称:《当代美国》翻译实践报告选题背景和意义:随着全球化的发展,美国在世界舞台上扮演着重要的角色,其政治、经济、文化等各方面的影响都十分深远。

因此,翻译涉及美国文化、社会、政治等相关领域的作品逐渐增多,涉及范围也越来越广泛。

在这样的背景之下,研究美国翻译的问题,对于提升我国的翻译技术和语言素养有重要作用。

研究方法和步骤:本文将采用实践与理论相结合的方法进行研究。

首先,选取多篇包括新闻报道、政治分析和文化评论等方面的英文原文,进行翻译实践。

其次,分析和总结在翻译实践过程中遇到的难点、翻译策略等问题,并结合相关理论进行分析和解释。

最后,撰写翻译实践报告,对研究结果进行总结与归纳。

研究计划:第一阶段:调研与材料收集,明确研究方向和选取翻译篇目;第二阶段:进行翻译实践,同时记录翻译过程和注意事项;第三阶段:归纳总结,在理论基础上分析翻译实践中遇到的难点与翻译策略;第四阶段:撰写翻译实践报告,结合实践和理论对研究结果进行总结;第五阶段:修改和完善研究报告,并进行最终的答辩。

预期成果:本研究将通过翻译实践,从实践出发,探究翻译过程中的难点和策略,并以理论为支撑进行分析和解释。

预期成果有以下几点:一、呈现多种类型文章的翻译实践,包括新闻报道、政治分析、文化评论等方面的翻译;二、探究翻译实践中的难点和解决方法,并结合相关理论进行分析和解释;三、提升翻译者的翻译素养和修炼,促进翻译工作的规范化和专业化程度的提高。

以上是本人对《当代美国》翻译实践报告开题报告的初步构想和设计,希望能够得到您的认可和支持。

当代美国翻译理论(转)2009-10-10 23:00郭建中编著,当代美国翻译理论,:教育,2000年4月。

一、赫伯特·库欣·托尔曼(Herbert Cushing Tolman)作者简介:赫伯特·库欣·托尔曼(Herbert Cushing Tolman)()“翻译的心理过程由两部分组成:第一,我们必须掌握原文作者的思想;第二,我们必须用译文的语言把原文作者的思想表达出来。

”“阅读是一回事,翻译是另一回事。

”译者只有从原文的观点出发去阅读,才能使自己沉浸在原文的思想和感情的激流之中,才能领会原文的精神实质。

“译者对原文的精神领会越深,就越感到自己责任之重大,也越来越深地理解到传达原作结构的精神实质之困难。

”“翻译要能在英国读者或听众中引起像原文读者或听众所感受的同样的感情。

”没有一个画家能完美地重现自然风景。

最好的画家并不是用与自然同样的颜色表现自然景色中的每一个细节;最好的画家应该是有感于壮丽的自然景色,并认识到绘画艺术的局限性,然后使自己的画尽可能地接近大自然的美景。

最好的翻译家也一样,他并不是在英语中精确地复制原作——因为这是不可能的——他只能使自己的译作尽可能地接近原作。

“翻译并不是把一种外语的单词译成母语(英语),而应该是原文中感情、生命、力度和精神的蜕变。

”我们既要忠实于原作的优美之处,也要忠实于原作的不足之处。

翻译不是解释。

“如果原作趴地蠕动,译作不可腾空翱翔。

”译文必须是地道的英语。

二、C·H·库利(C. H. Conley)尽管一般认为翻译经典著作有助于文化和自由思想的传播和发展,但16世纪英国经典著作的翻译反而助长了反动的社会和文化专制主义。

三、亨利·伯罗特·莱思罗普(Henry Burrowes Lathrop)16世纪英国所翻译的希腊罗马经典著作和我们今天所熟悉的完全不一样。

我们今天所认为的希腊罗马经典著作,他们没有翻译。

恰恰相反,他们所认为的经典著作,在今天,我们认为是不重要的,因此也并不熟悉。

四、威廉·弗罗斯特(William Frost)从理论上来说,诗歌是不可译的。

诗歌翻译只能是再创造。

成功的诗歌翻译要符合以下两个条件:(1)它必须是一首新的英诗,具有英诗固有趣味;(2)它必须是基于原作的基础上所作出的解释,或出自对原作的解释。

五、杰弗里·F·亨茨曼(Jeffrey F. Huntsman)尽管泰特勒提出的三原则[1]是不言自明的原理,但首先,这些原则是在泰特勒研究了大量的翻译实例之后形成的。

注释:[1] 泰特勒著名的三原则:(1)译作应完全复写出原作的思想;(2)译作的风格和笔调应和原作性质相同;(3)译作应与用原文创作的作品同样流畅。

泰特勒对前人有关翻译的论述重视不够,所引译作和译者也有很大的随意性。

泰特勒的贡献,正如泰特勒自己所说的,是在于从这些一般原理所引申出来的具体原则,并以大量正反面的离子来详细说明。

泰特勒写这篇论文的有两个目的。

一是泰特勒要证明,翻译决非易事。

翻译的艺术比一般人所想的要崇高得多,重要的多。

二是泰特勒想把翻译的原则总结成几条规律,以便译者完善自己的译文,也便于别人评判译作。

实际上,泰特勒在翻译理论上的地位和塞缪尔·约翰逊在词汇学上的地位相当。

泰特勒总结和概括了前人的翻译实践,并成为后人模仿的典。

六、博拉斯·奈特(Bouglas Knight)要理解蒲伯的英语诗歌译作,应放在荷马作品和史诗传统的背景下加以考察,而正是史诗的传统,把荷马的作品和蒲伯的英语诗歌译作融合在一起。

七、弗洛拉·罗斯·阿莫斯(Flora Ross Amos)中世纪英国的翻译理论尚处于幼稚的阶段;16世纪处于初步形成阶段;17世纪和18世纪是较为系统的现代翻译理论形成阶段。

翻译理论的发展,决非是一个连贯的、有序的进程,其间往往有中断。

那些为翻译指定规则的人,又往往看不到前辈或同辈有关翻译的论述。

对翻译的目的和方法,从未取得过一致的意见。

例如,谁是读者?谁是评判者?这些对译者和评论家来说都是至关重要的问题,都有对立的、甚至互不相容的观点。

很少批评家能勇于面对两种对立的观点和方法,把它们看成是可以调和的、互为补充的观点和方法。

翻译既要忠于原著,又要忠于英语的规。

容和形式应该是统一的。

翻译不应是母语的敌人,而是促进母语发展,并使母语表达更为清晰的手段。

把翻译看作是有益的实验,而不是犹豫不决的妥协,这是优秀翻译家的本质特征。

开明的、宽容的思想对翻译研究至关重要。

新的译作不断出现,理论家就必须修正前辈的思想以容纳新的事实。

翻译理论史是文学史的一个重要组成部分。

八、T.R.斯坦纳(Thomas R. Steiner)早期的翻译理论家是西塞罗(Cicero, 106~43 B.C.)、贺拉斯(Quintus Horatius Flaccus,一般称他Horace, 65~8 B.C.)、昆体良(Quintilian, 35?~95?)和普利尼(Pliny the Younger,61~112?),中世纪和文艺复兴初期无翻译理论可言。

但从查普曼开始,翻译理论重又受到重视。

查普曼在他的同时代翻译家中有很大的影响,并形成了新古典主义。

德莱顿之前有影响的翻译理论家有查普曼、德·阿柏兰库(Perrot d’Ablancourt)和德南姆。

当时的翻译理论主要有两种趋向,即以作者为归宿,还是以读者为归宿。

德莱顿则把两种倾向结合了起来。

德莱顿是英国制定翻译规律的人。

翻译家是画家,这是德莱顿的基本翻译思想,即强调翻译是艺术。

泰特勒也把翻译比作画画,但泰特勒强调的是翻译的困难,因为,画家临摹可用相同的材料,翻译家模仿却用的是不同的语言。

翻译家必须首先是诗人(因为当时谈的都是文学翻译,且主要是谈诗歌翻译)。

从查普曼到柯柏的17世纪和18世纪最重要的翻译思想是强调翻译家应与原作者融为一体。

翻译是一种“转述引语”(即“间接引语”)。

如果俄国和捷克的学者(形式主义运动的继承者)把语言学理论和统计理论应用于翻译研究,那么,奎因在《词语和对象》一书中,则勾画了形式逻辑与语言转换模式之间的关系。

九、安德烈·勒菲弗尔(Andre Lefevere,1944-1996)施莱尔马赫的译论是德国翻译理论的基石,也是德国翻译理论的高峰。

德国的翻译理论即使在今天,在许多方面仍然是文学翻译理论的重要组成部分。

十、弗雷德里克·M·勒(Frederick M. Rener)从西塞罗到泰特勒,阐释学的观点贯穿整个西方传统的翻译理论,即认为,与其说翻译是语言的操作,还不如说是阐释的过程。

讨论翻译的前提是语言学理论,在西方,从古代到18世纪,翻译家们都是在他们所处时代的语言学理论的指导下工作的。

语法:译者的基本工具。

译者可以不顾及作者的修辞特征,但必须重视用词的妥帖、纯正、清晰。

语法是基础,处于最低层,但又是十分重要和必要的。

译者地位也不高,但同样是十分重要和必要的。

修辞:译者修饰的工具。

翻译也深受修辞的影响。

翻译是艺术,翻译家是艺术家。

解释一直是翻译的基本特征。

从古代到18世纪末,人们并不把翻译仅仅看作是语言技巧,而主要是属于阐释学的畴。

模仿有两种。

一种是学习性的模仿,在翻译中,这种模仿是一种语言训练。

另一种是创造性模仿,在翻译中,这种模仿是创造出一种新的文学作品。

翻译研究包括三个领域:语法、修辞和翻译。

从研究的目的出发,又可分为两个层次。

语法和修辞是语言的层次,也是实践的层次;文本是属于阐释的层次,也是理论的层次。

从语言的角度来看,翻译似乎只是通过语言进行交际的活动。

但从阐释学的角度来看,翻译主要关注的是文本的信息,语言只是达到目的的手段。

从西塞罗到18世纪的传统语言符号理论认为,语言是思想的奴隶或是思想的外衣。

这种观点对译者有很大的影响。

从许多翻译家译作的序言中可以看出,许多译者都认为,译者的主要任务是翻译原文的容,改换原作者表达容的外衣。

如果译者有这样的观点,他们在翻译中首先就是要改变语言表达的形式。

近来的文学批评开始更注重读者以及读者在文学中的地位。

(Rener,1989)译者往往要写序言或后记。

里面的话实际上主要都是对读者来说的。

也就是说,译者总是想方设法地与读者沟通,因为读者是他服务的对象。

译者调动一切翻译手段都服务于“为读者服务”这一目的。

十一、道格勒斯·鲁滨逊(Douglas Robinson)理想的做法是把翻译的部研究和外部研究结合起来。

十二、乔纳斯·兹达尼斯(Jonas Zdanys)翻译可使学生进一步领会诗、语言、美学和阐释。

十三、弗雷德里克·威尔(Frederic Will)不存在一个同一个的客观现实,但认识本质是可能的,因为人类经验和感情中存在着一种“中心共核”,可以克服语言的模糊性,从而使“外在的现实”显露出来。

一部文学作品有其在的统一的意义,因而达到共同的理解是可能的。

十四、赖纳·舒尔特(Rainer Schulte)翻译研讨班的主要目的不是培养翻译家,而是对文学作品的阅读和理解。

翻译研讨班重新激活了阐释的艺术,......并重新肯定了阅读的艺术。

读者如果从译者的眼光去阅读,就能把自己摆到作品中去,通过对语言的探索,用自己的母语来诠释作品。

译者就是把阅读的行为转化为写作的行为。

因此,翻译研讨班是让学生阅读文学作品并发现其意义的一种手段。

十五、埃兹拉·庞德(Ezra Pound,1885~1972)作者简介:美国诗人、翻译家、文艺评论家,新批评派和意象派诗歌的主要代表。

最有影响的译作是英译中国古诗《中国》(Cathay,1915)(也译为《华夏》)。

一位理想的诗人与一位理想的诗歌翻译家是没有区别的。

诗歌翻译家只有深人原诗作者的思想,钻进原诗作者的灵魂深处,与原诗作者达到“神合”,才能超越文化和语言障碍,译出原诗的精神和效果。

艺术作品的意义不是一成不变的。

语言变了,作品的意义也就变了。

在原作中词语所引起的联想与不同时代和不同文化中重新塑造的新作品所引起的联想是不一样的。

意义不是什么抽象的东西,而是语言中的一部分,并永远处于历史的流动之中——即“气氛”。

要解开这一气氛中的意义,就必须了解历史,并重现意义所产生的那种“气氛”或环境。

诗歌的音乐感是很难翻译的,但视觉感可以全部或几乎全部可以翻译出来。

但词的本义和文字游戏的上下文意义是无法翻译的。

译者必须了解文本的时间、地点和意识形态的制约,然后融入文本所在的时间情绪、气氛和作者的思维过程中去,也许能,但也许无法找到对等的表达方式。

诗中能触动读者的眼睛而引起想象的部分,译成外语一点也不会遭到损失;而诉诸读者耳朵的部分,则只有阅读原作的人才能感受到的。