Theoretical fits of the delta Cephei light, radius and radial velocity curves

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:355.30 KB

- 文档页数:13

3.1恒星有多亮已完成成绩:100.0分1【单选题】恒星的真亮度,指的是把所有恒星都“挪到”距我们()个秒差距的地方时它们呈现的亮度。

∙A、3.26∙B、4.3∙C、10∙D、206265我的答案:C得分:25.0分2【单选题】根据恒星视亮度与视星等的数量关系(m=-2.5lgE),1等星与6等星的亮度相差()倍。

∙A、6∙B、2.51∙C、1/0.398∙D、100我的答案:D得分:25.0分3【判断题】秒差距这个长度标尺的推导过程,所利用的数学知识是极限,也就是视差角x→0时,sinx→x或者tanx→x。

()我的答案:√得分:25.0分4【判断题】夜空中,凡是耀眼的恒星都离我们更近,凡是相对黯淡的恒星都离我们更远。

()我的答案:×得分:25.0分3.2恒星光度和光谱测量已完成成绩:100.0分1【单选题】一般来说,表面温度越低的恒星,其发射的最强电磁波越不可能是()。

∙A、X射线∙B、黄色光∙C、红色光∙D、红外线我的答案:A得分:25.0分2【单选题】通过测量得到了一颗恒星的光度,则仍不能获取这颗恒星的()。

∙A、最强发射电磁波长∙B、表面温度∙C、单位表面的电磁波辐射强度∙D、环绕行星的数量我的答案:D得分:25.0分3【单选题】人类最早测量恒星光度的方法是()。

∙A、人眼主观判断∙B、胶卷照相∙C、光电法∙D、CCD技术我的答案:A得分:25.0分4【单选题】仅根据维恩公式,对一颗恒星进行分光光度测量,就可以间接获得它的()。

∙A、表面温度∙B、光谱型∙C、质量大小∙D、与太阳系的距离我的答案:A得分:25.0分3.3光谱型与主序星已完成成绩:100.0分1【单选题】从赫罗图可以得知,太阳属于哪一类恒星?()∙A、主序星∙B、白矮星∙C、红巨星∙D、红超巨星我的答案:A得分:20.0分2【单选题】多普勒效应与物体的运动速度的哪个性质的关系最大?()∙A、速率∙B、变化率∙C、方向∙D、惯性我的答案:C得分:20.0分3【单选题】光谱之于恒星,犹如()之于个人。

高二英语圆锥曲线练习题50题(答案解析)1. In ancient architecture, a certain building has a shape that resembles an ellipse. If the major axis length is 10 meters and the minor axis length is 6 meters, what is the eccentricity of this ellipse?A. 0.4B. 0.6C. 0.8D. 1.2答案:0.8。

解析:根据椭圆离心率公式e = c/a(c 为半焦距,a 为长半轴)。

首先求c,c² = a² - b²,a = 10/2 = 5,b = 6/2 = 3,c² = 5² - 3² = 16,c = 4。

所以e = c/a = 4/5 = 0.8。

选项A 计算错误;选项B 结果不对;选项D 超出离心率范围。

2. A planet's orbit around a star is elliptical. If the distance between the farthest point and the star is 100 million kilometers and the distance between the nearest point and the star is 40 million kilometers, what is the length of the major axis of the ellipse?A. 60 million kilometersB. 140 million kilometersC. 120 million kilometersD. 80 million kilometers答案:140 million kilometers。

What the core is doing is not obvious from the surface of the starWhat will be the structure of the Sun 5billion years from now?Outer layers of starswell up and cool -->red giant (not obvious)Old core (nowhelium) continues tocontract (it’s not inhydrostaticequilibrium)demoEventually, temperatures in compact core reach high enough temperatures for helium fusion reactions, the “triple alpha process”Triple alpha process can proceed when thetemperature reaches 100 million K.Later in the future life of the SunRussell diagramnebulas, revealing the weird coressaw it during the field trip)As cores contract, the density goes to “astronomical” levels, matter acts in funnyways•Gas in this room, the “perfect gas law”PV=nRT. Pressure depends on both density and temperature•Extremely dense, “degenerate” gasPV=Kn. Pressure depends only on density•DemoThe contracted core reaches a new balance between gravity and degenerategas pressureWhat are the physical properties of theseobjects?Gas pressure Self gravityView from a spaceship in the Sirius system We know the white dwarfs must have the properties as described (we’re not makingthis up)There are many known examples of white dwarfs;they are a common phenomenon in the galaxy / WDCatalog/index.html。

Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2005217Ton 202 as a StarY. P. Varshni and J. Talbot Department of Physics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada K1N 6N5 Telephone: 613-565-2974 Fax number: 613-562-5190 Email address: ypvsj@uottawa.caEvidence is marshaled from proper motion, emission line spectrum and absorption line spectrum to show that the quasar Ton 202 (1425+267) is a star and that its properties are consistent with the expectations of the PLAST theory. Keywords: Quasar, Plasma-laser star1. IntroductionWhen the spectrum of the star-like object 3C 273 was first observed in 1963, it was found to have one strong line and one medium/weak strength line. The problem was, however, that these lines were at wavelengths where no strong lines were expected from laboratory spectra. It has been a traditional assumption in astronomy that the intensities of lines in astronomical sources will be similar to those in the laboratory under ordinary excitation conditions. Schmidt assumed that these two lines were redshifted H alpha and H beta lines, and obtained a redshift of 0.157. Subsequently, when other such objects with broad emission lines were discovered (3C 48, 3C 191 etc) they© 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2005218were also labelled quasars and the spectra were similarly interpreted on the redshift hypothesis. In conjunction with Hubble's law it meant that quasars were very distant objects. This in turn led to the well known difficulties concerning their energy generation mechanism, optical variability, lack of correlation in the redshift-magnitude diagram, superluminal motion etc. Theoretical and experimental investigations in physics in the next decade showed that when a high temperature plasma rapidly expands (for example, in vacuum) the resulting cooling leads to a population inversion in the lower levels of the atom, and this can lead to laser action. Also, it is well known that in certain types of stars (Wolf-Rayet, P Cygni); matter is ejected more or less continuously. This led Varshni [1-11] to propose the following realistic model of a quasar: A quasar is a star in which the surface plasma is undergoing rapid radial expansion giving rise to population inversion and laser action in some of the atomic species. The assumption of the ejection of matter from quasars at high speed is supported from the fact that the widths of emission spectral lines observed in quasars are typically of the order of 2000 - 4000 km/sec. The ejected matter can form a nebulosity around the quasar or dissipate into space, depending on the rate of mass loss, how long the ejection has been going, the surroundings of the quasar etc. Laser action is enhanced if the hot plasma ploughs into this colder gas. Thus no redshifts are required to explain the strong emission lines. This model is called the plasma-laser star (PLAST) model. The spectrum of Ton 202 was first observed in the visible region by Greenstein and Oke [12] and by Barbieri [13]. It was found to show broad emission lines at unexpected wavelengths, like other quasars, and so it was assumed to be a quasar and it was given a redshift of 0.366 by Greenstein and Oke [12]. This theory that quasars are stars raises the question of their proper motions. In the present paper we discuss the proper motion and© 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2005219distance of the quasar Ton 202. The proper motions (absolute) of 951 faint blue stars have been determined by Luyten [14] based on plates taken at Palomar. A search of Luyten's measurements [14] has shown that the quasar Ton 202 has a substantial proper motion. From the data given by Luyten, the absolute proper motion for Ton 202 turns out to be 52.6 ms/year with a mean error of 16 ms/year. Ton 202 had not been recognized as a quasar at the time of Luyten's measurements, because its spectrum had not been observed and Luyten thought it to be a star. The Hipparcos data goes only down to 7.3 mag and TYCHO2 data goes down to 11 mag only. There does not seem to be any more accurate measurements of the proper motion of Ton 202 (m = 16). We may also mention some problems with present day techniques. VLBI measurements are open to argument that they refer to the radio emitting region, which may or may not coincide with the quasar. Often such measurements are based on the International Celestial Reference System (ICRS). The Ox axis of ICRS was implicitly defined in the initial realization of the IERS celestial reference frame in 1988 by adopting the mean J2000.0 right ascensions of 23 radio sources (quasars) in a group of VLBI catalogues. It was implicitly assumed that quasars being so far away have no perceptible motion. On the other hand, stars do have motions. If quasars are stars, then any measurements which are based on ICRS clearly would not give correct results. This problem is known amongst workers in this field. Based on ICRS, they have found proper motions for certain quasars, where they should have been zero on the redshift hypothesis. However, such results have not been published in the open literature. One learns about them from certain websites and in discussions at conferences. Large proper motions are indicative of the nearness of the astronomical object. Faint stars are often considered to be far away,© 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2005220but there is one important exception, planetary nuclei, which are intrinsically faint stars. Ton 202 is also a faint object, m = 16, and it shows broad emission lines like some planetary nuclei. Analogy is a powerful tool in science. In an earlier paper [4] we have pointed out the similarities between quasars and Wolf-Rayet type planetary nuclei. The faintness and the similarity of the spectrum of Ton 202 with some planetary nuclei suggests that perhaps we can get some idea of its distance by comparison, assuming that Ton 202 has the same sort of velocity as planetary nuclei. The largest proper motion reported up to now for a planetary nucleus is 40 ± 3 mas/year for NGC 7293 (believed to be the nearest planetary nebula)[15,16] and it is an isolated case. Proper motions for all other planetary nebulae for which measurements exist [16,17] are smaller than 24 mas/year, with considerable uncertainty in many cases. The distance of NGC 7293 is estimated to be 212 pc; from this it would be reasonable to estimate that the quasar Ton 202 lies within a few hundred parsecs from the sun. In other words, Ton 202 lies in our galaxy. Purely as an academic exercise, if we calculate the transverse velocity corresponding to the smallest value of the proper motion within the uncertainty range, assuming H = 50 km/sec per Mpc and q0 = 0, it turns out to be 1100c. The evidence clearly indicates that Ton 202 is a star. More accurate astrometric investigations on quasars are clearly most desirable. We would give further evidence to support the view that Ton 202 is a star and that its properties are consistent with the PLAST theory. Ton 202 is known to be surrounded by extended ionized nebulosity [18-20]; it is a consequence of the PLAST theory that many quasars will be surrounded by ionized nebulosity. According to PLAST theory, the emission lines will be broad as is the case for Ton 202.© 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 20052212. Emission-Line SpectrumNext we consider the spectrum of Ton 202. In the ultraviolet its emission line spectrum has been investigated by Gondhalekar et al. [21,22], and in the visible region by Greenstein and Oke [12] and by Barbieri [13], as noted earlier. We identify the observed emission lines (wavelengths in Å): • 1640 - He II λ1640 , • 2110 - Ca II λλ2103,2113 , • 2600 - O III λλ2598, 2605 and C III λλ2610,2614,2617 , • 3810 - It is a well known line in more than ten O VI sequence planetary nuclei and in several Sanduleak stars [4]. It is due to O VI λλ3811,3834 . • 6850 - Lines at λλ6857, 6863 and 6872 due to C III, multiplet 19, have been observed in the W-R spectra [23]. • 9010 - A line at λ9015.00 is known to occur in novaelike stars [23]. The emitter has not been identified. Thus we see that the emission lines which have been observed in Ton 202 also occur in certain type of stars. In Table 1 we list the wavelengths and the corresponding equivalent widths found by them and the identifications of the lines at no redshift. All wavelengths are in Angstroms (Å)3. Absorption-Line SpectrumNext we come to the absorption-line spectrum of Ton 202. Its spectrum in the ultraviolet has been observed by Bechtold et al. [24] with the high-resolution gratings of the Faint Object Spectrograph on board the Hubble Space Telescope. Besides the interstellar lines, their list has 8 lines.© 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2005Observed Wavelength 1653.55EWLab Wavelength 1654.10 1654.48 1658.67 1658.78 1684.58 1685.95 1689.49 1689.61 1689.82 2100.96 2104.85 2105.02 2105.98 2110.24 2110.37 2110.68 2110.72 2110.92 2110.98 2111.26 2114.87 2115.17IonMult.222 Difference38.4Fe II Fe II Mn III Fe II Mn II Fe II Mn II Mn II Fe II Fe III Cr III Fe III Mn III Fe II Cr II Cr II Fe II Cr II Cr II Cr II Cr III Fe I68 42 25 41 75 41 39 75 85 129 41 146 10 290 16 26 108 26 26 26 41 33–0.56 –0.93 –0.62 –0.74 0.00 –1.37 –0.01 –0.13 –0.34 0.82 0.84 0.67 –0.29 0.31 0.18 –0.13 –0.17 –0.37 –0.43 –0.71 0.51 0.211658.05 1684.587.4 16.31689.4813.12101.78 2105.69 2110.555.0 21.1 17.72115.3810.2The average of the absolute value of the difference between the observation and identification wavelength for all the identifications is 0.47 Å which is quite satisfactory. The lines are of the same type as those which occur in the ultraviolet region of shell stars.© 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2005223It would be of much interest to observe the absorption line spectrum of Ton 202 in the visible region (available spectra don't have enough resolution to resolve absorption lines). We expect that Fe II would be well represented in the absorption-line spectrum in the visible region. We would also like to draw attention to certain similarities between Ton 202 and the star upsilon Sgr. 1. In the two-color (U-B) versus (B-V) plot, the positions of Ton 202 and upsilon Sgr are pretty close as can be seen from the following values. For Ton 202: (U-B) = -0.75, (B-V) = 0.10 and for upsilon Sgr: (U-B) = -0.51, (B-V) = 0.10. 2. Both objects show large infrared excesses. Infrared photometry of upsilon Sgr has been carried out by Lee and Nariai [25], Woolf [26], and by Treffers et al. [27], and that of Ton 202 is taken from the 2MASS survey. In Figure 1 we compare the colors of Ton 202 with those of upsilon Sgr. It will be noted that both objects are very red at long wavelengths and the spectral energy distributions of the two are very similar. Two hypotheses have been advanced to explain the infra-red excess in upsilon Sgr. A late-type secondary or the circumstellar envelope. Parthasarathy et al. [28] have found that the companion is a hot star (late O or early B-type). Thus the second possibility seems most likely (see also Treffers et al., [27]). In the case of Ton 202, it is a natural consequence of our theory that the ejected material from the star will form a circumstellar envelope and in due course some of it will condense to form dust, which will lead to infrared excess. We may note here that ISO (Infrared Space Observatory) data shows an infrared nebulosity around TON 202. Upsilon Sgr shows a 10 micron emission feature (Treffers et al. [27]), which is similar to the 10 micron emission feature found around© 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2005224oxygen-rich stars and interpreted as being due to silicates. Irrespective of its interpretation it would be of interest to investigate if Ton 202 also shows the 10 micron emission feature. Summarizing, in this paper we have shown from evidence concerning proper motion, emission line spectrum and absorption line spectrum that the quasar Ton 202 (1425+267) is a star with high probability and that its properties are consistent with the expectations of the PLAST theory. It is also readily seen that this model resolves the well known difficulties concerning quasars, e.g., their energy generation mechanism, optical variability, lack of correlation in the redshift magnitude diagram, apparent brightnesses not diminishing with increasing redshift [29], superluminal motion etc. Accurate astrometric data on many quasars are badly needed. At present at least three projects are underway for precision optical astrometry of quasars. SIM - JPL Space Interferometry Mission [30,31], scheduled for launch in 2009. Two telescopes 10 m apart and 95 million km from earth will have 4 microarcsecond parallax accuracy, limiting mag 20. In its wide-angle mode, SIM will yield 4 microarcsecond absolute positions, and proper motions to about 2 microarcsecond/yr. FAME - Full-Sky Astrometric Mapping Explorer (FAME) [32] is expected to observe many quasars. GAIA - Global Astrometric Interferometer for Astrophysics. GAIA is a mission that will conduct a census of one billion stars to magnitude V = 20 in our Galaxy. It will monitor each of its target stars about 100 times during a five-year period, precisely charting their distances, movements and changes in brightness. To be launched in Mid-2011 by European Space Agency. GAIA will be placed in an orbit around the Sun, at a distance of 1.5 million kilometres further out than Earth. This special location, known as L2, will keep pace with the orbit of the Earth. Gaia will map the stars from there.© 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2005225Figure 1. The colors of Upsilon Sgr and Ton 202. The data points for Upsilon Sgr are from Lee and Nariai [25] and for Ton 202 the data are from USNO NOMAD, which is an aggregation from several surveys, U band from the SIMBAD U-B value, B and V bands from a YB6, R band from a USNO re-scan of POSS II red plates, I band from a USNO re-scan of POSS-II IV-N plates and J, H and K bands are from 2MASS. To accommodate the two objects on the same plot, the magnitudes for Ton 202 have been increased by 13.With these new high accuracy astrometric missions, it may be possible to determine the trigonometric parallax of some quasars. References[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] Y.P. Varshni, Bull. Am. Phys. Soc., 18, 1384 (1973). Y.P. Varshni, Bull. Am. Astron. Soc., 6, 213, 308 (1974). Y.P. Varshni, Astrophys. Space Sci., 37, L1 (1975). Y.P. Varshni, Astrophys. Space Sci., 46, 443 (1977). Y.P. Varshni, in S. Fujita (ed.), The Ta-You Wu Festschrift: Science of Matter, Gordon and Breach, New York, 1978, 285.© 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17][18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29]Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2005 226 Y.P. Varshni, Phys.Canada, 35, 11 (1979). Y.P. Varshni, Astrophys. Space Sci., 117, 337 (1985). Y.P. Varshni, Astrophys. Space Sci., 149, 197 (1988). Y.P. Varshni, Astrophys. Space Sci., 153, 153 (1989). Y.P. Varshni and C.S. Lam, Astrophys. Space Sci., 45, 87 (1976). Y.P. Varshni and R.M. Nasser, Astrophys. Space Sci., 125, 341 (1986). J.L. Greenstein and J.B. Oke, Pub. Astron. Soc. Pacific, 82, 898 (1970). C. Barbieri, 1970, quoted by Greenstein and Oke [12] W.J. Luyten, A Search for Faint Blue Stars, Paper 50,University of Minnesota Observatory, Minneapolis, 1969. Y.P. Varshni, Can. J. Phys., 58, 16 (1980). K.M. Cudworth, Astron. J., 79, 1384 (1974). L. Perek and L. Kohoutek, Catalogue of Galactic Planetary Nebulae, Czechoslovak Academy of Science, Prague, 1967; L. Kohoutek, in Planetary Nebulae, Y. Terzian (ed), IAU Symp., 76, 47 (1978). A. Stockton and J.W. Mackenty, Nature, 305, 678 (1983). A. Stockton, J.W. MacKenty , Astrophys.J., 316, 584 (1987). F. Durret, Astron. Astrophys. Suppl., 81, 253 (1989). C. Boisson, F. Durret, J. Bergeron and P. Petitjean, Astron. Astrophys., 285, 377 (1994). P.M. Gondhalekar, P. Obrien and R. Wilson, Monthly. Not. R. Astron. Soc., 222, 71 (1986). P.M. Gondhalekar, Monthly. Not. R. Astron. Soc., 237, 739 (1989). A.B. Meinel, A.F. Aveni and M.W. Stockton, Catalog of Emission Lines in Astrophysical Objects, The University of Arizona). Tucson, 1975. J. Bechtold, A. Dobrzycki, B. Wilden, M. Morita, J. Scott, D. Dobrzycka, K. Tran and T.L. Aldcroft, Astrophys. J. Suppl., 140, 143 (2002). T.A. Lee and K. Nariai, Astrophys.J., 149, L93 (1967). N.J. Woolf, Astrophys.J., 185, 229 (1973). R. Treffers, N.J. Woolf, U. Fink, H.P. Larson,, Astrophys.J., 207, 680 (1976). M. Parthasarathy, M. Cornachin, M. Hack, Astron.Astrophys., 166, 237 (1986). T. van Flandern, Bull. Amer. Astron.Soc., 25, 1395 (1993) 67.07. © 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — Apeiron, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2005 227 [30] S.C. Unwin, A.E. Wehrle , D.L. Jones , D.L. Meier and B.G. Piner, Publ.Astron. Soc. Australia, 19, 5 (2002).[31] E. Shaya, Bull. Amer. Astron. Soc., 33, 862 (2001).[32] S. Salim, A. Gould, and R. Olling, Bull. Amer. Astron. Soc., 33, 1437 (2001).© 2005 C. Roy Keys Inc. — 。

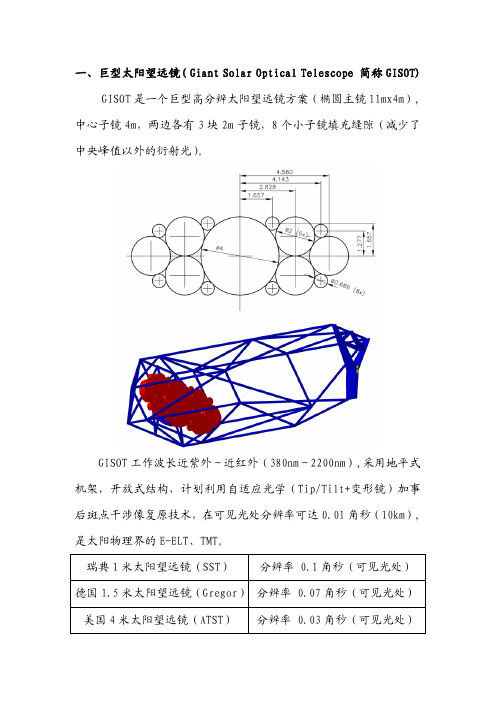

一、巨型太阳望远镜( Giant Solar Optical Telescope 简称GISOT)GISOT是一个巨型高分辨太阳望远镜方案(椭圆主镜11mx4m),中心子镜4m,两边各有3块2m子镜,8个小子镜填充缝隙(减少了中央峰值以外的衍射光)。

GISOT工作波长近紫外~近红外(380nm~2200nm),采用地平式机架,开放式结构,计划利用自适应光学(Tip/Tilt+变形镜)加事后斑点干涉像复原技术,在可见光处分辨率可达0.01角秒(10km),是太阳物理界的E-ELT、TMT。

瑞典1米太阳望远镜(SST) 分辨率 0.1角秒(可见光处) 德国1.5米太阳望远镜(Gregor)分辨率 0.07角秒(可见光处) 美国4米太阳望远镜(ATST) 分辨率 0.03角秒(可见光处)GISOT采用30m直径可折叠帐篷式圆顶,位于60m高塔架上。

主镜子镜是轻型镜面,镜面背部开有三角形空腔,镜面侧支撑在空腔内(不在镜面边缘),可使镜面彼此靠得更近。

空腔内还有空气冷却系统。

主镜抛物面(11mx4m),焦距18500mm。

次镜抛物面,直径340mm,焦距500mm。

GISOT光学系统图两种工作模式:1):共焦所有子镜元件共焦,需要高精度的指向控制,指向探测系统可采用太阳自适应光学波前探测系统。

2):共位相这需要对主镜元件进行高精度轴向控制(“piston”误差)。

普通的自适应光学波前探测技术(基于Shackhartman),不能测量“piston”误差,要用干涉测量方法。

有两种方法实现共位相测量a):用几个白光麦克尔逊干涉仪在子镜两两接触区域(有10个这样的区域)测量6个“piston”误差。

b):在曲率中心干涉测量(需要零位补偿)上述两种方法都不能探测大气引起的piston误差(在1um处将达10个波长),探测大气引起的piston误差可采用修正型Dame干涉仪。

参考文献1:GISOT: A giant solar telescopehttp://dot.astro.uu.nl/rrweb/dot-publications/gisot2004.pdf2004年SPIE Vol.5489二、印度2米太阳望远镜计划(India National Large Solar Telescope 简称NLST)印度天体物理研究所提出在喜玛拉雅山地区建造一个2米级的太阳望远镜。

Galactic aggregate 银河星集Galactic astronomy 银河系天文Galactic bar 银河系棒galactic bar 星系棒galactic cannibalism 星系吞食galactic content 星系成分galactic merge 星系并合galactic pericentre 近银心点Galactocentric distance 银心距galaxy cluster 星系团Galle ring 伽勒环Galilean transformation 伽利略变换Galileo 〈伽利略〉木星探测器gas-dust complex 气尘复合体Genesis rock 创世岩Gemini Telescope 大型双子望远镜Geoalert, Geophysical Alert Broadcast 地球物理警报广播giant granulation 巨米粒组织giant granule 巨米粒giant radio pulse 巨射电脉冲Ginga 〈星系〉X 射线天文卫星Giotto 〈乔托〉空间探测器glassceramic 微晶玻璃glitch activity 自转突变活动global change 全球变化global sensitivity 全局灵敏度GMC, giant molecular cloud 巨分子云g-mode g 模、重力模gold spot 金斑病GONG, Global Oscillation Network 太阳全球振荡监测网GroupGPS, global positioning system 全球定位系统Granat 〈石榴〉号天文卫星grand design spiral 宏象旋涡星系gravitational astronomy 引力天文gravitational lensing 引力透镜效应gravitational micro-lensing 微引力透镜效应great attractor 巨引源Great Dark Spot 大暗斑Great White Spot 大白斑grism 棱栅GRO, Gamma-Ray Observatory γ射线天文台guidscope 导星镜GW Virginis star 室女GW 型星habitable planet 可居住行星Hakucho 〈天鹅〉X 射线天文卫星Hale Telescope 海尔望远镜halo dwarf 晕族矮星halo globular cluster 晕族球状星团Hanle effect 汉勒效应hard X-ray source 硬X 射线源Hay spot 哈伊斑HEAO, High-Energy Astronomical 〈HEAO〉高能天文台Observatoryheavy-element star 重元素星heiligenschein 灵光Helene 土卫十二helicity 螺度heliocentric radial velocity 日心视向速度heliomagnetosphere 日球磁层helioseismology 日震学helium abundance 氦丰度helium main-sequence 氦主序helium-strong star 强氦线星helium white dwarf 氦白矮星Helix galaxy (NGC 2685 )螺旋星系Herbig Ae star 赫比格Ae 型星Herbig Be star 赫比格Be 型星Herbig-Haro flow 赫比格-阿罗流Herbig-Haro shock wave 赫比格-阿罗激波hidden magnetic flux 隐磁流high-field pulsar 强磁场脉冲星highly polarized quasar (HPQ )高偏振类星体high-mass X-ray binary 大质量X 射线双星high-metallicity cluster 高金属度星团;高金属度星系团high-resolution spectrograph 高分辨摄谱仪high-resolution spectroscopy 高分辨分光high - z 大红移Hinotori 〈火鸟〉太阳探测器Hipparcos, High Precision Parallax 〈依巴谷〉卫星Collecting SatelliteHipparcos and Tycho Catalogues 〈依巴谷〉和〈第谷〉星表holographic grating 全息光栅Hooker Telescope 胡克望远镜host galaxy 寄主星系hot R Coronae Borealis star 高温北冕R 型星HST, Hubble Space Telescope 哈勃空间望远镜Hubble age 哈勃年龄Hubble distance 哈勃距离Hubble parameter 哈勃参数Hubble velocity 哈勃速度hump cepheid 驼峰造父变星Hyad 毕团星hybrid-chromosphere star 混合色球星hybrid star 混合大气星hydrogen-deficient star 缺氢星hydrogenous atmosphere 氢型大气hypergiant 特超巨星Ida 艾达(小行星243号)IEH, International Extreme Ultraviolet 〈IEH〉国际极紫外飞行器HitchhikerIERS, International Earth Rotation 国际地球自转服务Serviceimage deconvolution 图象消旋image degradation 星象劣化image dissector 析象管image distoration 星象复原image photon counting system 成象光子计数系统image sharpening 星象增锐image spread 星象扩散度imaging polarimetry 成象偏振测量imaging spectrophotometry 成象分光光度测量immersed echelle 浸渍阶梯光栅impulsive solar flare 脉冲太阳耀斑infralateral arc 外侧晕弧infrared CCD 红外CCDinfrared corona 红外冕infrared helioseismology 红外日震学infrared index 红外infrared observatory 红外天文台infrared spectroscopy 红外分光initial earth 初始地球initial mass distribution 初始质量分布initial planet 初始行星initial star 初始恒星initial sun 初始太阳inner coma 内彗发inner halo cluster 内晕族星团integrability 可积性Integral Sign galaxy (UGC 3697 )积分号星系integrated diode array (IDA )集成二极管阵intensified CCD 增强CCDIntercosmos 〈国际宇宙〉天文卫星interline transfer 行间转移intermediate parent body 中间母体intermediate polar 中介偏振星international atomic time 国际原子时International Celestial Reference 国际天球参考系Frame (ICRF )intraday variation 快速变化intranetwork element 网内元intrinsic dispersion 内廪弥散度ion spot 离子斑IPCS, Image Photon Counting System 图象光子计数器IRIS, Infrared Imager / Spectrograph 红外成象器/摄谱仪IRPS, Infrared Photometer / Spectro- 红外光度计/分光计meterirregular cluster 不规则星团; 不规则星系团IRTF, NASA Infrared Telescope 〈IRTF〉美国宇航局红外Facility 望远镜IRTS, Infrared Telescope in Space 〈IRTS〉空间红外望远镜ISO, Infrared Space Observatory 〈ISO〉红外空间天文台isochrone method 等龄线法IUE, International Ultraviolet 〈IUE〉国际紫外探测器ExplorerJewel Box (NGC 4755 )宝盒星团Jovian magnetosphere 木星磁层Jovian ring 木星环Jovian ringlet 木星细环Jovian seismology 木震学jovicentric orbit 木心轨道J-type star J 型星Juliet 天卫十一Jupiter-crossing asteroid 越木小行星Kalman filter 卡尔曼滤波器KAO, Kuiper Air-borne Observatory 〈柯伊伯〉机载望远镜Keck ⅠTelescope 凯克Ⅰ望远镜Keck ⅡTelescope 凯克Ⅱ望远镜Kuiper belt 柯伊伯带Kuiper-belt object 柯伊伯带天体Kuiper disk 柯伊伯盘LAMOST, Large Multi-Object Fibre 大型多天体分光望远镜Spectroscopic TelescopeLaplacian plane 拉普拉斯平面late cluster 晚型星系团LBT, Large Binocular Telescope 〈LBT〉大型双筒望远镜lead oxide vidicon 氧化铅光导摄象管Leo Triplet 狮子三重星系LEST, Large Earth-based Solar 〈LEST〉大型地基太阳望远镜Telescopelevel-Ⅰcivilization Ⅰ级文明level-Ⅱcivilization Ⅱ级文明level-Ⅲcivilization Ⅲ级文明Leverrier ring 勒威耶环Liapunov characteristic number 李雅普诺夫特征数(LCN )light crown 轻冕玻璃light echo 回光light-gathering aperture 聚光孔径light pollution 光污染light sensation 光感line image sensor 线成象敏感器line locking 线锁line-ratio method 谱线比法Liner, low ionization nuclear 低电离核区emission-line regionline spread function 线扩散函数LMT, Large Millimeter Telescope 〈LMT〉大型毫米波望远镜local galaxy 局域星系local inertial frame 局域惯性架local inertial system 局域惯性系local object 局域天体local star 局域恒星look-up table (LUT )对照表low-mass X-ray binary 小质量X 射线双星low-metallicity cluster 低金属度星团;低金属度星系团low-resolution spectrograph 低分辨摄谱仪low-resolution spectroscopy 低分辨分光low - z 小红移luminosity mass 光度质量luminosity segregation 光度层化luminous blue variable 高光度蓝变星lunar atmosphere 月球大气lunar chiaroscuro 月相图Lunar Prospector 〈月球勘探者〉Ly-α forest 莱曼-α 森林MACHO (massive compact halo 晕族大质量致密天体object )Magellan 〈麦哲伦〉金星探测器Magellan Telescope 〈麦哲伦〉望远镜magnetic canopy 磁蓬magnetic cataclysmic variable 磁激变变星magnetic curve 磁变曲线magnetic obliquity 磁夹角magnetic period 磁变周期magnetic phase 磁变相位magnitude range 星等范围main asteroid belt 主小行星带main-belt asteroid 主带小行星main resonance 主共振main-sequence band 主序带Mars-crossing asteroid 越火小行星Mars Pathfinder 火星探路者mass loss rate 质量损失率mass segregation 质量层化Mayall Telescope 梅奥尔望远镜Mclntosh classification 麦金托什分类McMullan camera 麦克马伦电子照相机mean motion resonance 平均运动共振membership of cluster of galaxies 星系团成员membership of star cluster 星团成员merge 并合merger 并合星系; 并合恒星merging galaxy 并合星系merging star 并合恒星mesogranulation 中米粒组织mesogranule 中米粒metallicity 金属度metallicity gradient 金属度梯度metal-poor cluster 贫金属星团metal-rich cluster 富金属星团MGS, Mars Global Surveyor 火星环球勘测者micro-arcsec astrometry 微角秒天体测量microchannel electron multiplier 微通道电子倍增管microflare 微耀斑microgravitational lens 微引力透镜microgravitational lensing 微引力透镜效应microturbulent velocity 微湍速度millimeter-wave astronomy 毫米波天文millisecond pulsar 毫秒脉冲星minimum mass 质量下限minimum variance 最小方差mixed-polarity magnetic field 极性混合磁场MMT, Multiple-Mirror Telescope 多镜面望远镜moderate-resolution spectrograph 中分辨摄谱仪moderate-resolution spectroscopy 中分辨分光modified isochrone method 改进等龄线法molecular outflow 外向分子流molecular shock 分子激波monolithic-mirror telescope 单镜面望远镜moom 行星环卫星moon-crossing asteroid 越月小行星morphological astronomy 形态天文morphology segregation 形态层化MSSSO, Mount Stromlo and Siding 斯特朗洛山和赛丁泉天文台Spring Observatorymultichannel astrometric photometer 多通道天测光度计(MAP )multi-object spectroscopy 多天体分光multiple-arc method 复弧法multiple redshift 多重红移multiple system 多重星系multi-wavelength astronomy 多波段天文multi-wavelength astrophysics 多波段天体物。

arXiv:0711.2857v1 [astro-ph] 19 Nov 2007TheoreticalfitsoftheδCepheilight,radiusandradialvelocitycurves

GiovanniNatale1,2,MarcellaMarconi2,GiuseppeBono3

ABSTRACTWepresentatheoreticalinvestigationofthelight,radiusandradialvelocityvariationsoftheprototypeδCephei.Wefindthatthebestfitmodelaccountsforluminosityandvelocityamplitudeswithanaccuracybetterthan0.8σ,andfortheradiusamplitudewithanaccuracyof1.7σ.Thechemicalcompositionofthismodelsuggestsadecreaseinbothhelium(0.26vs0.28)andmetal(0.01vs0.02)contentinthesolarneighborhood.Moreover,distancedeterminationsbasedonthefitoflightcurvesagreeatthe0.8σlevelwiththetrigonometricparallaxmeasuredbytheHubbleSpaceTelescope(HST).Ontheotherhand,distancedeterminationsbasedonangulardiametervariations,thatareindependentofinterstellarextinctionandofthep-factorvalue,indicateanincreaseoftheorderof5%intheHSTparallax.

Subjectheadings:Cepheids–stars:distances–stars:evolution–stars:oscilla-tions

1.IntroductionClassicalCepheidsarethemostimportantprimarydistanceindicators.OneofthekeyissuesconcerningtheuseofCepheidsasdistanceindicatorsistheirdependenceonchemicalcomposition.Empiricaltestsseemtosuggestthatmetal-richCepheidsare,atfixedperiod,brighterthanmetal-poorones,eitherovertheentireperiodrange(Kennicuttetal.1998,2003;Kanburetal.2003;Stormetal.2004;Groenewegenetal.2004;Sakaietal.2004;–2–Macrietal.2006)orforperiodsshorterthan≈25days(Sasselovetal.1997;Sandageetal.2004).Ontheotherhand,distanceestimatesbasedontheNear-InfraredSurfaceBrightnessmethodindicatethattheslopeofthePeriod-Luminosity(PL)relationmightbethesameforMagellanicandGalacticCepheids(Gierenetal.2005).However,theimpactoftheprojectionfactorpontheCepheiddistancesisstilldebated(Sahaetal.2006;Nardettoetal.2007).Earlytheoreticalpredictionsbasedonlinearpulsationmodels(e.g.Sandageetal.1999;Alibertetal.1999;Baraffe&Alibert2001)predictedamildmetallicityeffect,whilenonlinearconvectivemodels(Bonoetal.1999;Caputoetal.2002;Fiorentinoetal.2002;Marconietal.2005)showedthatthemetallicityaffectsboththezero-pointandtheslopeofthePLrelations.Thiseffectismoreevidentintheopticalbandsanditisnonlinearwhenmovingfrommetal-poor(Z=0.004)tosupermetal-rich(Z=0.04)structures.Currentpredictionsalsosuggestaturnoveracrosssolarmetallicity(Z∼0.02)duetothecorrelatedincreaseinHecontent(Fiorentinoetal.2002;Marconietal.2005).

ThreeapproachesareadoptedtocalibratetheCepheidPLrelations:clusterdistances,trigonometricparallaxesandBaade-Wesselink(BW)method.ParallaxesbasedonCepheidsinopenclustersandassociationshavebeenwidelyadoptedtocalibratethePLrelations(Turner&Burke2002),butFouqueetal.(2007)foundasystematicdifferencewithothermethods.AccurateCepheidparallaxeshavebeenprovidedbyBenedictetal.(2002)andbyBenedictetal.(2007)usingtheFineGuideSensoronboardtheHubbleSpaceTelescope(HST).TheymeasuredthedistanceofseveralGalacticCepheidswithaveragerelativeerrorsof≈8%.TheBWmethodappearstobearobustapproach,butsomeassumptionsneedtobeinvestigated(Gautschy1987;Bonoetal.1994;Gierenetal.2005).Thevalueoftheprojectionfactor(p),i.e.theparameteradoptedtotransformradialintopulsationvelocity,isstillcontroversial(Sabbeyetal.1995;M´erandetal.2006).Thetypicalvalueusedintheliteratureisp=1.36(Burkietal.1982),butperiod-dependentvaluesarealsoadopted(Gierenetal.1993,2005).However,thep-factorofδCephei,p=1.27±0.06,measuredbyM´erandetal.(2005),usingtheHSTparallax,agreesquitewellwiththepredictedvalue(Nardettoetal.2004).

Although,severalCepheidsarebinariesdynamicalmassestimatesareonlyavailableforahandfulobjects(Evansetal.2005).Currentmassestimatesrelyeitheronevolutionaryoronpulsationprescriptions(D’Cruzetal.2000;Keller&Wood2002;Caputoetal.2005)andwearestillfacingthelong-standingproblemofthe“Cepheidmassdiscrepancy”(Cox1980).Evolutionarymassesaresystematicallylargerthanpulsationmasses(Bonoetal.2001;Beaulieuetal.2001;Caputoetal.2005).

TheoreticalfitsofCepheidlightcurvesproviderobustconstraintsontheirintrinsicparametersanddistances(Woodetal.1997;Bonoetal.2002;Keller&Wood2006).This–3–approach,uptonow,hasonlybeenappliedtoBumpCepheids.Wepresent,forthefirsttime,asimultaneousfitofoptical/NIRlight,radialvelocity,andangulardiametervariationsoftheprototypeδCephei.Weselectedthisobjectbecauseaccuratemeasurementsoflight,radius,velocitycurves,andofthep-factorareavailableanditsgeometricdistanceisknownwithanaccuracyof4%(273+12−11Benedictetal.2002).

2.EmpiricalandtheoreticalframeworkTheoptical(V,I)andthenear-infrared(NIR)K-bandlightcurvewerecollectedbyKiss(1998)andbyBarnesetal.(1997).Weselectedtheselightcurvesbecauseboththeshapeandtheamplitudeintheopticalbandsdependonsurfacetemperatureandradiusvariation,whileinK-bandthedependenceontemperatureissignificantlyreduced.TheradialvelocitydatawerecollectedbyBersieretal.(1994)1,whiletheangulardiameterandtheprojectionfactorbyM´erandetal.(2005).TheobservablesforδCepheiaresummarizedinTable1.