(2005)日本版FN的临床治疗

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:114.40 KB

- 文档页数:5

11116 2005年日本销售额前十名的药品和治疗类别

杨绍杰(摘)

【期刊名称】《国外药讯》

【年(卷),期】2006(000)011

【摘要】武田公司的抗高血压药Blopress(candesartan,坎地沙坦)再次位居2005年日本处方药市场销售额排名列表中的第一名,随后是Pfizer公司的钙离子拮抗剂Norvasc(amlodipine,氨氯地平)。

在此期间,整个市场增长回到7%的水平。

【总页数】1页(P49)

【作者】杨绍杰(摘)

【作者单位】无

【正文语种】中文

【中图分类】R394

【相关文献】

1.2005年~2010年全球销售额年均增长率超过10%的农药品种 [J], 张一宾;

2.2005年日本北兴化学工业株式会社农药销售额下降 [J],

3.2005年世界医药市场销售额领先的十大药品 [J], 无

4.2005年世界医药市场药品销售额领先的地区 [J], 无

5.2005年零售药品销售额增长5% [J], 杨绍杰(摘)

因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

nf化疗方案化疗是目前医学界治疗恶性肿瘤的主要手段之一,而NF化疗方案是其中一种常用的化疗方案。

本文将介绍NF化疗方案的具体内容,包括药物组成和治疗效果等方面。

一、NF化疗方案的药物组成NF化疗方案是针对某些恶性肿瘤的常规化疗方案之一,其药物组成多种多样。

下面将详细介绍几种常见的NF化疗药物:1. 氟尿嘧啶(5-FU):氟尿嘧啶是一种抗代谢药物,能够抑制肿瘤细胞的DNA合成,从而达到抑制细胞分裂和增殖的作用。

它被广泛用于治疗消化系统肿瘤和乳腺癌等。

2. 奈达铂(Nedaplatin):奈达铂是一种铂类化疗药物,对于某些固体肿瘤有较好的疗效。

它能够通过与肿瘤细胞DNA结合,阻断DNA链的合成,从而抑制肿瘤细胞的生长。

3. 福尼替尼(Folotyn):福尼替尼是一种抗代谢药物,常用于治疗周围T细胞淋巴瘤。

它能够通过抑制DNA和RNA的合成,干扰癌细胞的生长周期,从而达到抗癌的效果。

二、NF化疗方案的治疗效果NF化疗方案往往针对某些恶性肿瘤,如结直肠癌、胃癌、肺癌等,具有显著的治疗效果。

下面将从不同类型肿瘤的角度来介绍其治疗效果:1. 结直肠癌:NF化疗方案在结直肠癌的治疗中起到了重要作用。

研究表明,使用NF方案进行化疗能够显著延长结直肠癌患者的生存期,并且减轻患者的症状。

2. 胃癌:NF化疗方案在胃癌治疗中也有较好的效果。

临床研究发现,采用NF方案化疗的患者,其肿瘤持续缩小的比例明显高于其他化疗方案。

3. 肺癌:针对肺癌的NF化疗方案也受到了广泛应用。

研究显示,通过采用NF方案化疗,肺癌患者的远期生存率得到了明显提高。

三、NF化疗方案的副作用和注意事项尽管NF化疗方案具有较好的治疗效果,但也存在一些副作用,患者需要特别注意。

以下是一些常见的副作用和注意事项:1. 恶心和呕吐:由于化疗药物对消化系统的刺激,患者可能会出现恶心和呕吐等不适症状。

此时,患者可在医生指导下采取相应的抗恶心药物。

2. 免疫抑制:NF化疗方案中的药物可能会抑制患者的免疫系统,增加患者感染的风险。

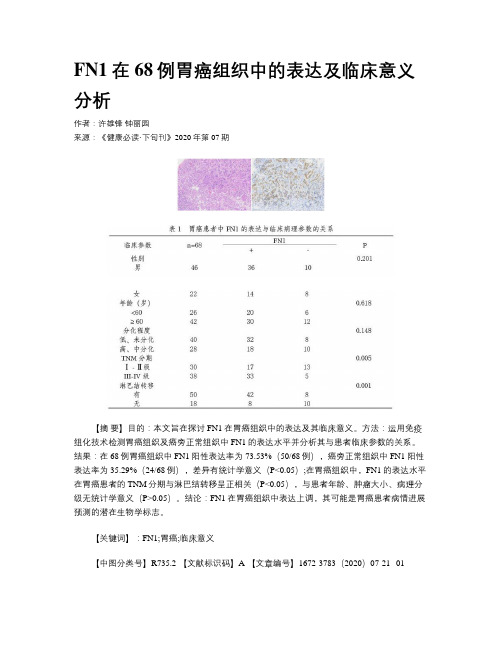

FN1在68例胃癌组织中的表达及临床意义分析作者:许雄锋钟丽园来源:《健康必读·下旬刊》2020年第07期【摘要】目的:本文旨在探讨FN1在胃癌组织中的表达及其临床意义。

方法:运用免疫组化技术检测胃癌组织及癌旁正常组织中FN1的表达水平并分析其与患者临床参数的关系。

结果:在68例胃癌组织中FN1阳性表达率为73.53%(50/68例),癌旁正常组织中FN1阳性表达率为35.29%(24/68例),差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);在胃癌组织中,FN1的表达水平在胃癌患者的TNM分期与淋巴结转移呈正相关(P<0.05),与患者年龄、肿瘤大小、病理分级无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

结论:FN1在胃癌组织中表达上调,其可能是胃癌患者病情进展预测的潜在生物学标志。

【关键词】:FN1;胃癌;临床意义【中图分类号】R735.2 【文献标识码】A 【文章编号】1672-3783(2020)07-21--01胃癌是第四大最常见的癌症,是癌症死亡的第三大主要原因,已经成为世界范围内重要的健康问题,尤其是在中国,韩国和日本。

根据国际癌症研究机构的数据,2012年约诊断出950,000例胃癌新病例,和70万例死亡病例[1]。

通常,该疾病被诊断已为晚期,并且大多数患者中可用的治疗方法有限。

目前,尽管外科手术结合放疗,化学疗法和靶向治疗可以延长患者生存期,但晚期胃癌患者的5年总生存率仍然很差。

因此,迫切需要开发新的诊断方法和新疗法以降低与胃癌相关的死亡率并改善患者的临床疗效。

纤维连接蛋白(FN)是一种高分子量的糖蛋白,分子量介于220,000和250,000之间。

作为一种粘附分子,FN最初是从人血浆和成纤维细胞的细胞表面分离出来的,并以高水平存在于细胞外基質中,包括存在于胶质瘤在内的多种肿瘤中。

纤维连接蛋白1(FN1)是FN 家族的成员,它参与多种细胞生物学过程,包括细胞粘附,迁移,生长和分化在内的多个细胞过程中起着至关重要的作用。

FN诊疗方案FN(Febrile Neutropenia)是指发热和中性粒细胞减少的病症,常见于癌症患者接受化疗后。

为了确保癌症患者能够安全度过FN期,并尽早恢复治疗,医学界提出了一套完善的FN诊疗方案。

一、患者评估在开始治疗之前,医生需要对患者进行全面评估,以确定患者的病情和诊疗方案。

1. 体格检查:医生会对患者进行全面体格检查,包括查看体温、心率、呼吸频率、血压等重要指标。

2. 实验室检查:患者需要进行血常规、尿常规、生化指标等一系列实验室检查,以评估患者的免疫功能和身体状况。

3. 临床评分系统:医生会根据患者的体温、心率、呼吸频率、血压、年龄等信息,使用相应的临床评分系统对患者进行评估,以确定患者的危险程度。

二、抗菌治疗根据患者的病情评估结果,医生会选择合适的抗菌药物进行治疗。

1. 细菌谱覆盖范围:医生会选择广谱抗生素,以覆盖多种细菌感染。

常用的抗生素包括青霉素类、头孢菌素类和喹诺酮类等。

2. 经验性治疗:对于危重患者或无法明确感染来源的患者,医生会根据临床经验,选择更广谱的抗生素进行治疗。

3. 药物联合治疗:对于高危患者或有特殊感染源的患者,医生会考虑联合用药,以增加疗效。

三、支持治疗除了抗菌治疗,患者还需要接受一系列的支持治疗,以促进康复和减轻不适。

1. 充分水合:患者需要补充足够的液体,以保持体内水分平衡,促进康复。

2. 症状控制:如果患者伴有其他不适症状,如呕吐、腹泻等,医生会给予相应的药物进行控制。

3. 营养支持:患者需要接受高营养价值的饮食或静脉输液,以满足身体恢复所需的营养。

四、治疗评估在治疗过程中,医生会定期对患者的病情进行评估,以确定治疗效果。

1. 温度监测:医生会定期测量患者的体温,观察发热情况是否得到控制。

2. 实验室检查:患者需要定期进行血常规等实验室检查,以评估炎症指标是否有所改善。

3. 临床症状:医生会观察患者的一般症状,如乏力、食欲减退等,以判断患者是否有康复迹象。

核准日期:2020年4月7日 修改日期:2020年7月10日 修改日期:2020年9月29日富马酸伏诺拉生片说明书请仔细阅读说明书并在医师指导下使用。

【药品名称】通用名称:富马酸伏诺拉生片 商品名称:沃克(Vocinti)英文名称:Vonoprazan Fumarate Tablets 汉语拼音:Fumasuan Funuolasheng Pian 【成份】本品主要成分为富马酸伏诺拉生。

化学名称:1-[5-(2-氟苯基)-1-(吡啶-3-磺酰基)-1H -吡咯-3-基]-N -甲基甲胺单富马酸盐 化学结构式:分子式:C 17H 16FN 3O 2S·C 4H 4O 4 分子量:461.46 【性状】10mg(按C 17H 16FN 3O 2S 计):本品为浅黄色薄膜衣片,除去包衣后显白色。

20mg(按C 17H 16FN 3O 2S 计):本品为浅红色薄膜衣片,除去包衣后显白色。

【适应症】 反流性食管炎。

【规格】按C 17H 16FN 3O 2S 计(1)10mg;(2)20mg 【用法用量】口服。

成人每日1次,每次20mg。

大部分患者通常4周可获益,如果疗效不佳,疗程最多可延长至8周。

【不良反应】临床试验下表列出了本品国内外临床试验期间报告的不良反应。

发生频率分类使用以下惯例并依据国际医学科学组织委员会(CIOMS)指南:十分常见(≥1/10);常见(≥1/100至<1/10);偶见(≥1/1,000至<1/100);罕见(≥1/10,000至< 1/1,000);十分罕见(<1/10,000);不详(无法根据可用数据进行估计)。

表1 伏诺拉生临床试验期间的不良反应以下是在上市后观察到的但上文未包括的不良反应,频率未知。

免疫系统疾病:药物超敏反应(包括过敏性休克)、药物性皮炎、荨麻疹。

肝胆系统疾病:肝毒性、黄疸。

皮肤和皮下组织疾病:多形性红斑、史蒂文斯-约翰逊综合征、中毒性表皮坏死松解症。

日本国神经病理性疼痛药物治疗指南:第2版(最全版)第4部分伴有神经病理性疼痛的疾病一、带状疱疹后神经痛(慢性阶段)带状疱疹后神经痛的首选用药是什么?因为有高质量循证学证据证实三环类抗抑郁药和钙通道α2δ配基的疗效,这两种药被推荐用于带状疱疹后神经痛。

注释:三环类抗抑郁药(tricyclic antidepresants, TCAs)如阿米替林(叔胺类)和去甲阿米替林(仲胺类)对于带状疱疹后神经痛(postherpetic neuralgiza, PHN)有效。

在一项对PHN患者进行的安慰剂对照试验中,阿米替林组疼痛缓解程度明显高于安慰剂组。

另外一项对PHN患者76例进行的为期8周的随机对照试验(randomized controlled trial, RCT)中,和安慰剂比,去甲阿米替林和脱甲丙咪嗪组NRS显著减低(1.4比0.2)。

在对阿米替林和去甲阿米替林疗效比较的一项研究中,两者的镇痛效果没有明显差别。

然而据报道,去甲阿米替林具有较好的耐受性同时伴有较低的副作用(如口干、嗜睡)发生率而更具有优势。

许多RCT试验证实钙通道α2δ配基如普瑞巴林、加巴喷丁的显著疗效。

一项对PHN患者76例进行的RCT试验比较了加巴喷丁和去甲阿米替林的效果,结果为尽管加巴喷丁可引起较少的副作用如口感和体位性低血压,但两者对于VAS和SF-MPQ评分方面的改善程度类似。

选择每一种药物时一定要考虑副作用。

TCA的心脏毒性和抗胆碱能作用以及钙通道α2δ配基的中枢神经系统抑制作用需要考虑。

度洛西汀用于PHN患者的RCT研究还是空白;度洛西汀作为一种选择性5-羟色胺和去甲肾上腺素再摄取抑制剂(se-lective serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, SNRI),被强烈推荐用于疼痛性糖尿病神经病变。

阿片类药物对于带状疱疹后神经痛有效吗?阿片类药物对带状疱疹后神经痛有效:但是效果较三环类抗抑郁药和钙通道α2δ配基差。

一、引言胃癌是全球癌症死亡的主要原因之一,我国胃癌发病率和死亡率较高。

近年来,随着医学技术的不断发展,胃癌的治疗方法也在不断更新。

二线治疗方案在胃癌治疗中占据重要地位,本文将详细介绍日本胃癌二线治疗方案。

二、胃癌二线治疗的概念胃癌二线治疗是指在胃癌一线治疗失败后,针对残余肿瘤或复发肿瘤采取的治疗措施。

二线治疗主要包括化疗、靶向治疗、免疫治疗、放射性治疗等。

三、日本胃癌二线治疗方案1. 化疗化疗是胃癌二线治疗中最常用的方法,其目的是减轻肿瘤负荷、缓解症状、延长生存期。

以下为日本常用的胃癌二线化疗方案:(1)FOLFIRI方案:5-氟尿嘧啶(5-FU)、亚叶酸钙(FA)、伊立替康(CPT-11)组成的化疗方案,对晚期胃癌有一定疗效。

(2)mFOLFOX6方案:5-氟尿嘧啶、亚叶酸钙、奥沙利铂(Oxaliplatin)组成的化疗方案,对晚期胃癌有一定疗效。

(3)XELOX方案:奥沙利铂、卡培他滨(Capecitabine)组成的化疗方案,对晚期胃癌有一定疗效。

2. 靶向治疗靶向治疗是近年来兴起的一种胃癌二线治疗手段,通过针对肿瘤细胞特异性信号通路,抑制肿瘤细胞生长、转移和增殖。

以下为日本常用的胃癌二线靶向治疗方案:(1)表皮生长因子受体(EGFR)抑制剂:如吉非替尼(Gefitinib)、厄洛替尼(Erlotinib)等,适用于EGFR基因突变的胃癌患者。

(2)血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)抑制剂:如贝伐珠单抗(Bevacizumab)、瑞格列净(Regorafenib)等,适用于VEGF通路异常的胃癌患者。

3. 免疫治疗免疫治疗是近年来胃癌治疗研究的热点,通过激活人体免疫系统,增强对肿瘤细胞的杀伤能力。

以下为日本常用的胃癌二线免疫治疗方案:(1)程序性死亡蛋白-1(PD-1)抑制剂:如纳武单抗(Nivolumab)、帕博利珠单抗(Pembrolizumab)等,适用于PD-1/PD-L1阳性的胃癌患者。

International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents26S(2005)S123–S127Clinical guidelines for the management of neutropenic patients with unexplained fever in Japan:validation by theJapan Febrile Neutropenia Study GroupKazuo Tamura∗The First Department of Internal Medicine,School of Medicine,Fukuoka University,Fukuoka,JapanAbstractThe Japan Febrile Neutropenia Study Group(JFNSG)Trial was a multicenter,open,randomized study designed to validate thefirst Japanese guidelines for the management of neutropenic cancer patients with unexplained fever issued in1998.The trial compared cefepime monotherapy with cefepime plus amikacin combination therapy in febrile neutropenic patients with hematological disorders.The JFNSG found that monotherapy with cefepime was,in general,as effective as combination therapy.In terms of subset analyses,defervescence appeared to occur more frequently in leukemic patients and in those with profound neutropenia treated with the dual combination.The conclusion of the trial was that the1998guidelines were applicable to the Japanese febrile neutropenic patient population.The JFNSG met again in2003to revise these guidelines.An important addition to the guidelines was a distinction between low-and high-risk patients.Low-risk febrile neutropenic patients can receive oral ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin,with or without amoxicillin/clavulanic acid,on an outpatient basis,or intravenous (i.v.)monotherapy with cefepime,ceftazidime or a carbapenem.High-risk patients can receive i.v.cefepime,ceftazidime or a carbapenem, or an i.v.dual combination with cefepime,ceftazidime or a carbapenem plus an aminoglycoside.Those patients with a documented infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus should also receive a glycopeptide.It remains to be determined whether existing assessment scoring systems apply to Japanese patients;whether a broad-spectrum cephalosporin plus an aminoglycoside combination is required as the initial management of patients with acute leukemia and/or profound neutropenia;which antibacterial drugs should be used whenfirst-and second-line agents fail;what are the appropriate oral agents and dosing regimens for low-risk patients;whether serology or the polymerase chain reaction should be the preferred marker for initiating pre-emptive antifungal therapy;and whether the azoles or the candins should be the preferred antifungal agents.©2005Elsevier B.V.and the International Society of Chemotherapy.All rights reserved.Keywords:Monotherapy;Combination therapy;Febrile neutropenia;Risk stratification1.IntroductionGuidelines for the management of neutropenic cancer patients with fever of unknown origin werefirst issued in Japan in1998[1].Two separate study groups were sub-sequently formed to validate these guidelines,the Kyushu Hematology Organization for Treatment(K-HOT)Study Group,involving17institutions[2],and the Japan Febrile Neutropenia Study Group(JFNSG)[3],involving30institu-tions.∗Fax:+81928628200.E-mail address:ktamura@fukuoka-u.ac.jp.2.The JFNSG Trial2.1.Background dataThe JFNSG Trial was a multicenter,open,randomizedstudy designed to compare cefepime monotherapy withcombination therapy of cefepime plus amikacin in febrileneutropenic patients with hematological disorders[3].Febrile neutropenia was defined by an axillary temperature ≥37.5◦C,an absolute neutrophil count(ANC)<1000/L and increasing levels of C-reactive protein(CRP)in patientswith no other identifiable cause of fever.Patients with blooddisorders meeting these criteria were randomized to receiveempirical treatment with either intravenous(i.v.)cefepime0924-8579/$–see front matter©2005Elsevier B.V.and the International Society of Chemotherapy.All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.08.001S124K.Tamura /International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 26S (2005)S123–S127Fig.1.Study by the Japan Febrile Neutropenia Study Group (JFNSG)[1,3].CRP,C-reactive protein.monotherapy 1–2g every 12h,or i.v.cefepime plus amikacin combination 100–200mg every 12h,and were re-assessed after 3days.If defervescence occurred at day 4,patients with infections of unknown etiology continued receiving the same treatment for an additional 4days,whereas therapy was adjusted related to the causative microorganism in those with infections of established etiology.The total duration of treatment was 7days.Patients who remained febrile at day 4were re-assessed based on a complete blood count,blood chemistry profile,serology for fungal pathogens,CRP,radiography,etc.(Fig.1)[1,3].If the etiology of infection was established,therapy was adjusted accordingly.Vancomycin therapy was considered for Gram-positive infections.If the etiology of infection remained unknown,patients on monotherapy received an aminoglycoside in addition to cefepime.If afebrile after 48h,the patient continued with the same treatment.If febrile,they received an antifungal agent.Change to another -lactam antimicrobial was considered for patients previously on dual therapy.Fungal serology and/or culture were performed.Amphotericin B was added to patients with positive fungal cultures,amphotericin B or an azole was added to those with positive serology,while an azole was added to those with negative serology.Patients were evaluated at days 3,7,10,14and 30after initiation of empirical therapy.Response to treatment was stratified as:excellent if afebrile within 3days with clini-cal/laboratory improvement;good if afebrile within 7days with clinical/laboratory improvement;fair if fever tended to decrease within 7days with clinical/laboratory improvement;and poor if the initial drug had to be changed within 3days,or if fever had not declined within 7days,with no clini-cal/laboratory improvement.2.2.ResultsOf the 201patients initially recruited,it was possible to evaluate 189(95in the monotherapy arm and 94in the combi-nation therapy arm).Complete defervescence with improved general condition at day 3was obtained in 32.6%of patients in the monotherapy arm compared with 45.7%in the combina-tion therapy arm (not significant).By day 7,64.2%and 76.6%of patients in the cefepime monotherapy 1–2g i.v.every 12h group and the cefepime plus amikacin 100–200mg i.v.every 12h combination group,respectively,had responded (not sig-nificant).The potential impact of three variables,namely body tem-perature,ANC and underlying disease,on treatment response was examined.In general,no significant differences were observed in the response to monotherapy or to combination therapy at day 3and day 7in terms of body temperature below,equal to,or above 38.0◦C.With regard to the ANC at the start of empirical antibiotic treatment,at day 3cefepimeK.Tamura/International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents26S(2005)S123–S127S125alone was equally effective as the combination therapy for patients with ANCs between500/L and1000/L,whereas the cefepime plus amikacin combination was more effective for those with fewer than500neutrophils/L.This suggests that high-risk patients should be further stratified in terms of their ANCs before selecting an empirical treatment approach. Finally,when patients were categorized as leukemic or non-leukemic,the dual combination seemed more effective for leukemic patients.Adverse events were few and generally mild.In the monotherapy group,two patients developed a skin rash and two had liver dysfunction.In the dual therapy arm,one patient each developed a skin rash,liver dysfunction and renal dysfunction.There werefive cases of bacteremia both in the cefepime monotherapy group(Enterobacter cloacae,Staphylococ-cus epidermidis,Pseudomonas aeruginosa,Aeromonas hydrophila and Escherichia coli)and in the combination ther-apy group(P.aeruginosa,E.coli,Stomatococcus mucilagi-nosus and coagulase-negative staphylococci(two patients)). Gram-negative bacteria were more prevalent.One patient in the combination therapy arm developed fungemia by Can-dida inconspicua at day14,and another developed fungemia by an unspecified Candida at day17.2.3.ConclusionsThe JFNSG concluded that:•an axillary temperature≥37.5◦C and an ANC<1000/L were appropriate markers for the initiation of antibiotic therapy in febrile neutropenic patients;•patients with ANCs between500/L and1000/L tend to respond to antibiotics better than other patients;•monotherapy with cefepime is,in general,as effective as combination therapy;and•according to subset analyses,defervescence appears to be attained more frequently with the dual combination in leukemic patients and in those with profound neutropenia, although these two groups did not differ in terms of overall survival or risk for severe complications.Based on these considerations,the JFNSG concluded that the1998febrile neutropenia guidelines were applicable to the Japanese febrile neutropenic patient population.3.The2003revision of the Japanese guidelinesIn2002,the Infectious Diseases Society of America revised the US guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer[4].Novel characteristics of the revised guidelines included:1.stratification of febrile neutropenic patients into high-versus low-risk subgroups;e of oral antibiotic therapy in carefully selected patientsat low risk of complications;3.an extension from3days to3–5days in the time for eval-uating initial therapy;4.the feasibility of continuing to administer the same initialantimicrobials to stable patients with persistent fever;and 5.the emphasis on an ANC of500/L for importantdecision-making in the management of febrile neu-tropenic patients.In2003,the JFNSG met again in Honolulu,Hawaii,to revise the Japanese guidelines[5].The revised Japanese guidelines incorporated a distinction between low-and high-risk patients.Various instruments have been developed to make this distinction,including a scoring system designed to identify low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients[4,6]. An important pending task in this respect is the validation of these instruments specifically for the Japanese patient popu-lation.In the revised Japanese guidelines,febrile neutropenic patients at low risk of complications can be given oral ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin,with or without amoxi-cillin/clavulanic acid,on an outpatient basis.Low-risk patients can also be given i.v.monotherapy with cefepime, ceftazidime or a carbapenem.Oral agents used in Japan are different from those used in the Western world.They are usually administered at one-third to one-half the dose used in the USA,e.g.ciprofloxacin200mg every8h.Similarly, i.v.agents,e.g.cefepime,ceftazidime and carbapenems,are administered in Japan at1–2g every12h.Patients at high risk of complications can be given i.v. cefepime,ceftazidime or a carbapenem in a schedule similar to that outlined for low-risk patients,or a dual combination therapy with i.v.cefepime,ceftazidime or a carbapenem plus an aminoglycoside.A glycopeptide such as vancomycin or teicoplanin should be added to the treatment of high-risk patients with documented infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.Patients should be re-assessed after 3–5days.Those with infections of unknown etiology who become afebrile by days4or5can continue on the initial empirical treatment for at least4additional days.When the etiology of the infection has been established,therapy can be adjusted accordingly.If defervescence fails to occur in4–5days,patients need to be re-assessed,based on a complete blood count,blood chemistry profile,cultures,serology for fungal pathogens, CRP,radiography and other imaging techniques(Fig.2)[5]. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or gamma globulin therapy,if not instituted previously,should be considered for patients with persistent fever at days4–5.Patients with infec-tions of unknown etiology who remain stable can continue receiving the initial antibiotic regimen.Those previously on monotherapy who show signs of progressive disease should have an aminoglycoside added to their treatment.A change to alternative monotherapy should be considered, e.g.the initial cephalosporin can be changed to another cephalosporin or a carbapenem,or the initial carbapenem can be changed to a broad-spectrum cephalosporin.ForS126K.Tamura /International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 26S (2005)S123–S127Fig.2.The 2003Japan Febrile Neutropenia Study Group (JFNSG)new guidelines [5].CBC,complete blood count;CRP,C-reactive protein;G-CSF,granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.patients initially receiving dual therapy,the cephalosporin or carbapenem can be changed as recommended above,whereas the initial aminoglycoside should be changed to another aminoglycoside or to i.v.ciprofloxacin.If the patients are afebrile when re-assessed 48h later,no further changes in therapy are needed.In contrast,a shift to another -lactam antibiotic should be considered for those with persistent fever,as well as for those with signs of progressive disease originally treated with combination therapy.Fungal infection should be evaluated in these patients based on serology and/or culture,and determination of -d -glucan and galac-tomannan antigenemia.If the culture is positive,specific therapy for the fungal pathogen should be initiated.If fungal infection is considered possible or probable,an azole (if not used as prophylaxis),amphotericin B or the echinocandin micafungin (where this product is available)should be added.Patients with infections of established etiology should have their therapy adjusted based on the causative microor-ganism.If this is a Gram-positive bacterium,treatment with a glycopeptide should be considered.4.Issues pending elucidationResearch to be planned for the next few years should address a number of unanswered questions related to the man-agement of infections in febrile neutropenic patients.Some of these are:•Are the scoring systems developed to assess the risk for complications applicable to Japanese patients?•Is a dual combination strategy with a broad-spectrum cephalosporin and an aminoglycoside required as the ini-tial management of patients with acute leukemia and/or profound neutropenia?•Which antibacterial agents should be given to patients who fail to respond to first-and second-line therapies?•Which are the appropriate oral agents and dosage regimens for low-risk patients?•Should serology or the polymerase chain reaction be the preferred marker for initiating pre-emptive antifungal ther-apy?Which should be the preferred antifungals for empir-ical therapy:the azoles or the candins?K.Tamura/International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents26S(2005)S123–S127S127References[1]Masaoka T.Management of fever of unknown origin in theneutropenic patient:the Japanese experience.Int J Hematol 1998;68(Suppl.1):S9–11.[2]Tamura K,Matsuoka H,Tsukada J,et al.Cefepime or carbapenemtreatment for febrile neutropenia as a single agent is as effective asa combination of4th-generation cephalosporin+aminoglycosides:comparative study.Am J Hematol2002;71:248–55.[3]Tamura K,Imajo K,Akiyama N,et al.Randomized trial of cefepimemonotherapy or cefepime in combination with amikacin as empir-ical therapy of febrile neutropenia.Clin Infect Dis2004;39:S15–24.[4]Hughes WT,Armstrong D,Bodey GP,et al.2002guidelines for theuse of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer.Clin Infect Dis2002;34:730–51.[5]Tamura K.Initial empirical antimicrobial therapy:duration and sub-sequent modifications.Clin Infect Dis2004;39:S59–64.[6]Klastersky J,Paesmans M,Rubenstein EB,et al.The MultinationalAssociation for Supportive Care in Cancer risk index:a multinational scoring system for identifying low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients.J Clin Oncol2000;18:3038–51.。