专八听力讲座2016(新考纲)

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:752.00 KB

- 文档页数:59

痫狂英语 理论版圆CRAZY ENGLISH PROTEM-8听力理解测试内容效度分析以2016、2017年TEM-8考试为例王晓霜!湖北工业大学,湖北武汉430064)摘要:效度是衡量测试有效性的重要标准,英语专业八级考试作为检查英语专业学生英语能力的测试,自1991年开始实行以来,其效度一直是人们关注的焦点。

国内对T E M<效度的研究主要集中在阅读理解方面,关于听力效度的研究较少。

2016年教育部发布的新考纲对T E M<)题型进行了调整。

文章对实施新考纲之后的2016年2017年的T E M<测试中听解部分的效度进行了分析,以期对T E M<测试的命题有所帮助。

关键词:TEM< $听力理解;有效性;内容效度[中图分类号]H319.6[文献标识码]A[文章编号]1006-2831 (2018)02-0022-2 doi% 10. 3969/j. issn. 1006-2831.2018.01.008!研究背景TEM-8(Test for English Majors-Band8 ),全国高校英 语专业八级考试,是1991年起由教育部实行的:参 性教学检查 试。

其目的是检测英语专业学生运用英语获取、和处理一般或与专业相 以达到的能力。

TEM-8自问世以来,经历了多次改革。

2015年8月的《英语专业八级考试(TEM-8)题调整说》中,再 TEM-8了改革和调整。

具体调整如下:Mini lecture即讲座长度增加,从10题 15 题,改为提前发卷;Conversation or Interview即会话题目 数量不变,问题消失,问题在听力中 ,新闻听力取消。

听力 试时间由35 改为25。

TEM-8取之后,听力 数百比由原先的20%升到了 25%。

TEM-8的研究从未间断过,其中关于效度的 研究也不在少数,然而大 研究都集中在阅读理解方,听力 效度的研究较少。

种象,分析了 2016年及2017年听力测试效度。

专业八级讲座——听力[replyview]听力理解讲座考试技巧1. 预览试题TEM8考试听力前部都有一小段提示语印在试卷和录在磁带上,要求考生如何答题。

如果考生对此很熟悉,就可以利用这段时间快速预览一下该部分的几个问题(前三个部分都有五个问题),做到在听录音前对所听内容有一个方向性的认识,在一定程度上帮助答题。

例如看到下面一题时,我们即可知道整个录音很可能与赌博有关。

The development of the gambling compulsion can be described as beingA. gradualB. slowC. periodicD. radical我们一旦获悉即将听的一篇材料与赌博有关的信息后,大脑就很自然地启动一些我们所储存的关于赌博的情景,这样就几乎达到了兵马未动,粮草先行的境地,从而主动权就部分地掌握在考生手里。

反之,如果不进行试题预览,我们可能在听完全部材料的三分之一后才知道其中心议题是赌博。

这就是预览的重要性。

不仅如此,我们还可以利用多余的答题时间来达到预览的目的。

题与题之间一般有15秒的答题时间,如果考生只用5秒就做好了第一题,那么余下的10秒就可以用于预览第2题、第3题等。

TEM8考试听力的四个部分中,只有第四部分考生不能预览,因为考生在做完笔录后才发给该部分答卷,即ANSWER SHEETONE。

2. 审题须仔细审题似乎是一个老生常谈的话题,但却是十分重要的问题。

这里所说的审题并非指考生完全看不懂题目,而是指由于审题不仔细而捕捉不到问题的核心。

我们来看看下面一道题:The modern electronic anti-noise devicesA. are an update version of the traditional methods.B. share similarities with the traditional methods.C. are as inefficient as the traditional methods.D. are based on an entirely new working principle.以上问题的核心在于领会modern electronic anti-noise devices (现代抗噪音电子装置)的定义,而不仅仅是electronic anti-noise devices(抗噪音电子装置),更不是一般的anti-noise devices(抗噪音装置)。

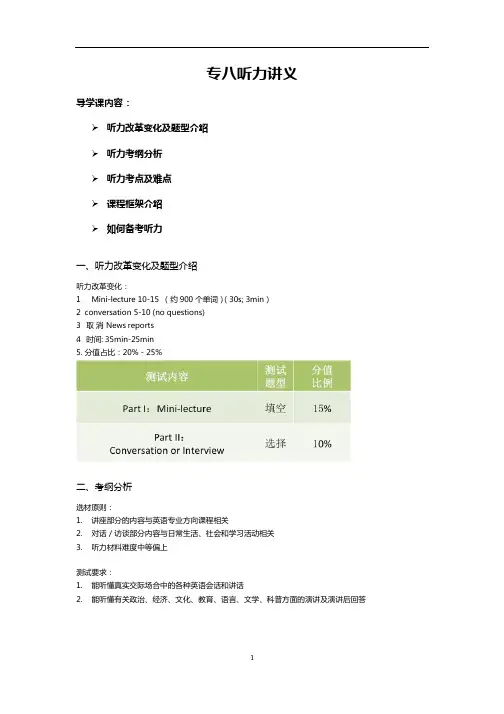

专八听力讲义导学课内容:➢听力改革变化及题型介绍➢听力考纲分析➢听力考点及难点➢课程框架介绍➢如何备考听力一、听力改革变化及题型介绍听力改革变化:1.Mini-lecture 10-15 (约 900 个单词)(30s; 3min)2.conversation 5-10 (no questions)3.取消 News reports4.时间: 35min-25min5. 分值占比:20%-25%二、考纲分析选材原则:1.讲座部分的内容与英语专业方向课程相关2.对话/访谈部分内容与日常生活、社会和学习活动相关3.听力材料难度中等偏上测试要求:1.能听懂真实交际场合中的各种英语会话和讲话2.能听懂有关政治、经济、文化、教育、语言、文学、科普方面的演讲及演讲后回答3.能理解材料大意,领会说话者态度、情感、真实意图4.能做较完整的笔记三、听力的考点及难点考点宏观:✓英语能力:语音、词汇、语法✓非英语能力逻辑分析、灵活应用提取归纳信息、短时记忆考点微观:✓连读、爆破、弱化等;✓英美发音;✓从句、非谓语、被动等;✓敏感听力点✓记笔记难点:1.如何快速抓取并记录有用信息2.如何分析理解复杂句意四、课程框架介绍强化阶段:方法+实践1、各题型解题方法2、听力技能练习方法3、大纲样题及真题解析冲刺阶段:1、回顾总结各题型练习方法2、考前突击方法3、考场注意事项及高分技巧五、如何备考听力✓针对不同程度的学生:基础较薄弱:词汇是重点-夯实基础语法知识基础一般:词汇-强化相关语音知识基础较好:听写+有逻辑的笔记✓精听训练:所需材料-历年真题1.审题2.不间断听力3.查阅4.视听(边听边读)5.裸听p.s.查阅定义:1.核对答案2.找出选项及原文所有不会及不熟单词及短语,做好笔记3.分析每到题正确和错误的理由4.确认所有选项及答案对应的原文处可以通顺的翻译成中文✓听写训练1、选取合适的文章2、先练习抓取重要信息(关键词)3、再练习记录完整句子4、不断缩减听音次数✓跟读训练:加强及时反应,增加储存记忆。

2016年英语专业八级听力English:Part 1。

Section A:1. The main goal of the speaker's research was to investigate the relationship between.> (A) parental involvement and children's academic achievement.> (B) socioeconomic status and children's behaviour.> (C) teachers' qualifications and students' performance.> (D) school size and students' motivation.Answer: (A)。

2. According to the speaker, a key factor contributing to the success of the school is.> (A) the implementation of a rigorous curriculum.> (B) the use of innovative teaching methods.> (C) the creation of a supportive and inclusive school climate.> (D) the provision of extensive extracurricular activities.Answer: (C)。

3. The speaker suggests that teachers should.> (A) focus on developing students' critical thinking skills.> (B) prioritize students' memorization of facts.> (C) use a variety of teaching methods to meet the needs of all students.> (D) strictly adhere to the established curriculum.Answer: (A)。

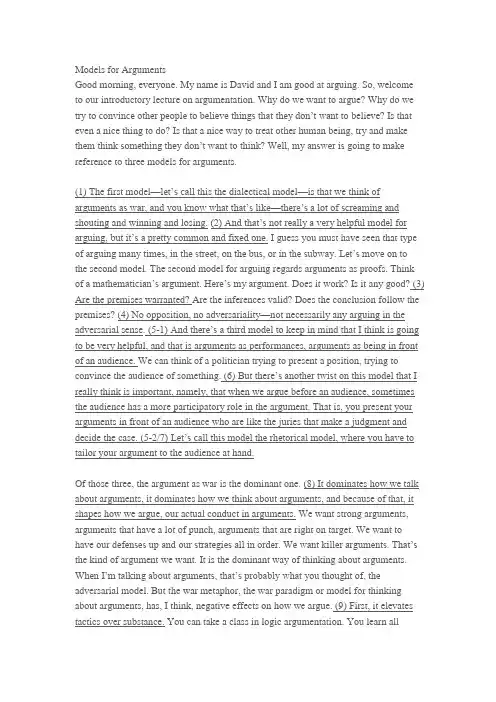

about the strategies that people use to try and win arguments, and that makes arguing adversarial; it’s polarizing. And the only foreseeable outcomes are triumph—glorious triumph—or disgraceful defeat. (10) I think those are very destructive effects, and worst of all, it seems to prevent things like negotiation and collaboration. Um, I think the argument-as-war metaphor inhibits those other kinds of resolutions to argumentation. (11) And finally—this is really the worst thing—arguments don’t seem to get us anywhere; they’re dead ends. We don’t get anywhere.Oh, and one more thing. (12) That is, if argument is war, then there’s also an implicit aspect of meaning—learning with losing. And let me explain what I mean. (13) Suppose you and I have an argument. You believe a proposition, and I don’t. And I say, “Well, why do you believe that?” And you give me your reasons. And I object and say, “Well, what about…?” And you answer my objection. And I have a question: “Well, what do you mean? How does it apply over here?” And you answer myq uestion. Now, suppose at the end of the day, I’ve objected, I’ve questioned, I’ve raised all sorts of questions from an opposite perspective, and in every case you’ve responded to my satisfaction.And so at the end of the day, I say, “You know what? I guess you’re right.” Maybe finally I lost my argument, but isn’t it also a process of learning? So, you see arguments may also have positive effects. (14) So, how can we find new ways to achieve those positive effects? We need to think of new kinds of arguments. Here, I have some suggestions: If we want to think of new kinds of arguments, what we need to do is think of new kinds of arguers—people who argue. So try this: Think of all the roles that people play in arguments. There’s the proponent and the opponen t in an adversarial, dialectical argument. There’s the audience in rhetorical arguments. There’s the reasoner in arguments as proofs. All these different roles. Now, can you imagine an argument in which you are the arguer, but you’re also in the audience, watching yourself argue? (15) Can you imagine yourself watching yourself argue? That means you need to be supported by yourself. Even when you lose the argument, still, at the end of the argument, you could say, “Wow, that was a good argument!” Can you do that? I think you can. In this way, you’ve been supported by yourself.Up till now, I’ve lost a lot of arguments. It really takes practice to become a good arguer in the sense of being able to benefit from losing, but fortunately, I’ve had many, many colleagues who have been willing to step up and provide that practice for me.OK. To sum up, in today’s lecture, I’ve introduced three models of arguments. The first model is called the dialectical model, the second one is the model of arguments as proofs, and the last one is called the rhetorical model, the model of arguments as performances. I have also emphasized that though the adversarial type of arguments is quite common, we can still make arguments produce some positive effects. Next time, I will continue our discussion on the process of arguing.。

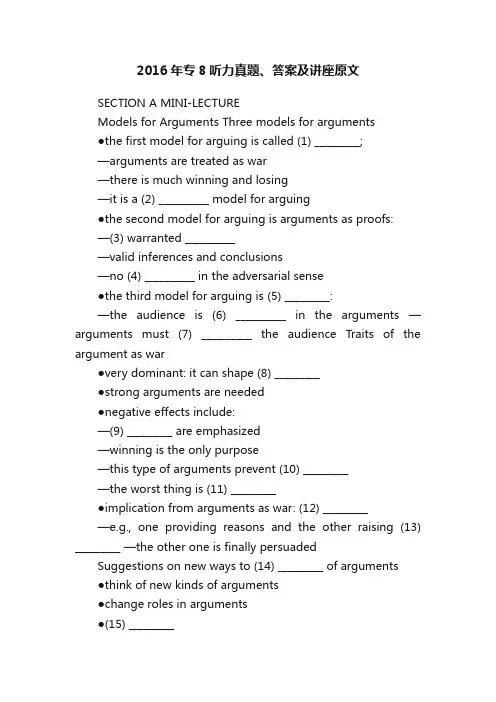

2016年专8听力真题、答案及讲座原文SECTION A MINI-LECTUREModels for Arguments Three models for arguments●the first model for arguing is called (1) _________;—arguments are treated as war—there is much winning and losing—it is a (2) __________ model for arguing●the second model for arguing is arguments as proofs:—(3) warranted __________—valid inferences and conclusions—no (4) __________ in the adversarial sense●the third model for arguing is (5) _________:—the audience is (6) __________ in the arguments —arguments must (7) __________ the audience Traits of the argument as war●very dominant: it can shape (8) _________●strong arguments are needed●negative effects include:—(9) _________ are emphasized—winning is the only purpose—this type of arguments prevent (10) _________—the worst thing is (11) _________●implication from arguments as war: (12) _________—e.g., one providing reasons and the other raising (13) _________ —the other one is finally persuadedSuggestions on new ways to (14) _________ of arguments●think of new kinds of arguments●change roles in arguments●(15) _________SECTION B INTERVIEWNow, listen to the Part One of the interview. Questions 1 to 5 are based on Part One of the interview.1.What is the topic of the interview?A. Maggie’s university life.B. Her mom’s life at Harvard.C. Maggie’s view on studying with Mom.D. Maggie’s opinion on her mom’s major.2.Which of the following indicates that they have the same study schedule?A. They take exams in the same weeks.B. They have similar lecture notes.C. They apply for the same internship.D. They follow the same fashion.3.What do the mother and the daughter have in common as students?A. Having roommates.B. Practicing court trails.C. Studying together.D. Taking notes by hand.4.What is the biggest advantage of studying with Mom?A. Protection.B. Imagination.C. Excitement.D. Encouragement.5.What is the biggest disadvantage of studying with Mom?A. Thinking of ways to comfort Mom.B. Occasional interference from Mom.C. Ultimately calls when Maggie is busy.D. Frequent check on Maggie’s grades.Now, listen to the Part Two of the interview. Questions 6 to 10 are based on Part Two of the interview.6.Why is parent and kid studying together a common case?A. Because parents need to be ready for new jobs.B. Because parents love to return to college.C. Because kids require their parents to do so.D. Because kids find it hard to adapt to college life.7.What would Ma ggie’s mom like to be after college?A. Real estate agent.B. Financier.C. Lawyer.D. Teacher.8.How does Maggie’s mom feel about sitting in class after30 years?A. Delighted.B. Excited.C. Bored.D. Frustrated.9.What is most challenging for Maggie’s m om?A. How to make a cake.B. How to make omelets.C. To accept what is taught.D. To plan a future career.10.How does Maggie describe the process of thinking out one’s career path?A. Unsuccessful.B. Gradual.C. Frustrating.D. Passionate.1.the dialectical model/doc/8a754565.html,mon and fixed3.premises4.opposition / arguing5.arguments as performances / the rhetorical model6.participatory / participating / the participant / taking part7.be tailored to / cater for8.how we argue / our actual conduct9.tactics / strategies10.negotiation and collaboration11.ther e’s no solution / progress12.learning with losing13.questions / counter-considerations / counter-arguments / objections /arguments in opposition14.achieve positive effects15.support oneself / yourselfC AD D BA C D C BGood morning, everyone. My name is David and I am good at arguing. So welcome to our introductory lecture on argumentation. Why do we want to argue? Why do we try to convince other people to be lieve things that they don’t want to believe? And is that even a nice thing to do? Is that a nice way to treat other human being, try and make them think something they don’t want to think? Well, my answer is going to make reference to three models for arguments.(1) The first model —let’s call this the dialectical model—is that we think of arguments as war. And you know what that’s like. There is a lot of screaming and shouting and winning andlosing. (2) And that’s not really a very helpful model arguing, but it’s a pretty common and fixed one. I guess you must have seen that type of arguing many times —in the street, on the bus or in the subway.Let’s move on to the second model. The second model for arguing regards arguments as proofs. Think of a mathema tician’s argument. Here’s my argument. Does it work? Is it any good? (3) Are the premises(前提)warranted? Are the inferences(推论)) valid? Does the conclusion follow the premises? (4) No opposition, no adversariality(对抗)—not necessarily any arguing in the adversarial sense.(5) And there’s a third model to keep in mind that I think is going to be very helpful, and that is arguments as performances, arguments as being in front of an audience. We can think of a politician trying to present a position, trying to convince the audience of something.But there’s another twist(转折)on this model that I really think is important; namely, that when we argue before an audience, (6)sometimes the audience has a more participatory role in the argument; that is, you present you arguments in front of an audience who are like juries(陪审团)that make a judgment and decide the case.(5) Let’s call this model the rhetorical model, (7) where you have to tailor(迎合)your argument to the audience at hand.Of those three, the argument as war is the dominant one. It dominates how we talk about arguments, it dominates how we think about arguments, and because of that, (8) it shapes how we argue, our actual right on target.We want to have our defenses up and our strategies all in order. We want killer arguments. That’s the kind of argument we want. It is the dominant way ofthinking about arguments. When I’m talking about arguments, that’s probably what you thought of, the adversarial model.But the war metaphor, the war paradigm(范例)or model for thinking about arguments, has, I think, negative effects on how we argue. (9) First, it elevates tactics over substance. You can take a class in logic argumentation. You learn all about the strategies that people use to try and win arguments and that makes arguing adversarial; it’s polarizing(分化的). And the only foreseeable outcomes are triumph —glorious triumph —or disgraceful(可耻的)defeat. I think those are very destructive effects, and worst of all, (10) it seems to prevent things like negotiation and collaboration(合作). Um, I think the argument-as-war metaphor inhibits(阻止)those other kinds of resolutions to argumentation.(11) And finally —this is really the worst thing —arguments don’t seem toget us anywhere; they’re dead ends(死胡同). We don’t anywhere. Oh, and one more thing. (12) That is, if argument is war, then there’s also an implicit(绝对的)aspect of meaning —learning with losing.And let me explain what I mean. Suppose you and I have an argument. You believe a proposition(命题)and I don’t. And I say, “Well, why do you believe that?”And you give me your reasons. And I object and say, “Well, what about…?” And I have a question: “Well, what do you mean? How does it apply over here?” And you answer my question. Now, suppose at the end of the day, I’ve objected, I’ve questioned, (13)I’ve raised all sorts of questions from an opposite perspective and in every case you’ve responded to my satisfaction. And so at the end of the day, I say, “You know what? I guess you’re right.” Maybefinally I lost my argument. But isn’t it also a process of learning? So you see arguments may also have positive effects.(14) So, how can we find new ways to achieve those positive effects? We need to think of new kinds of arguments. Here I have some suggestion. If we want to think of new kinds of argument, what we need to do is think of new kinds of arguers —people who argue.So try this: Think of all the roles that people play in arguments. (1) (5) There’s the proponent and the opponent in an adversarial, dialectical argument(对话式论证). Ther e’s the audience in rhetorical arguments.There’s the reasoner in arguments as proofs. All these different roles. Now, can you imagine an argument in which you are the arguer, but you’re also in the audience, watching yourself argue? Can you imagine yourself watching yourself argue? (15) That means you need to be supportedby yourself. Even when you lose the argument, still, at the end of the argument, you could say, “Wow, that was a good argument!” Can you do that? I think you can. In this way, you’ve been supported by yourself.Up till now, I have lost a lot of arguments. It really takes practice to become a good arguer, in the sense of being able to benefit from losing, but fortunately, I’ve had many, many colleagues who have been willing to step up and provide that practice for me.Ok. To sum up, in today’s lecture, I have introduced three models of arguments.(1) The first model is called the dialectical model. The second one is the model of arguments as proofs. (5) And the last one is called the rhetorical model, the model of arguments asperformances. I have also emphasized that, though the adversarial type of arguments is quite common, we can still make arguments produce some positive effects. Next time I will continue our discussion on the process of arguing.。

2016专八听力新题型完全解读作者:春花老师来源:星火英语《高等学校英语专业高年级英语教学大纲》规定,高等学校英语专业高年级英语的教学任务是“继续打好语言基本功,进一步扩大知识面,重点应放在培养英语综合技能,充实文化知识,提高交际能力上。

”自2016年起,外语专业教学测试专家委员会对TEM-8考试的试卷结构、测试要求和测试形式均做出重大调整。

今儿个星火君给大家扒一扒专八听力~本部分采用填空题和多项选择题形式,分两节:Section A 讲座和Section B 会话,共25题。

录音语速为每分钟约150个单词。

下面是本部分的测试要求:(a)能听懂真实交际场合中的各种英语会话和讲话;(b)能听懂有关政治、经济、历史、文化、教育、语言、文学、科普方面的演讲及演讲后的问答;(c)能理解所听材料的大意,领会说话者的态度、感情和真实意图;(d)能做较为完整的笔记;(e)考试时间约25分钟。

此次专八考试听力题型有较大调整,具体包括:1. Section A Mini-lecture由原来的10道填空题增加到15道题,听后发卷改为听前发卷。

新的测试形式规定,本部分由一个约900个单词的讲座和一项填空任务组成,要求学生边听边做笔记,然后完成15道填空题。

本部分内容的选材与本专业方向课程相关。

试题数量由原来的10题增加到15题,需要考生捕捉的细节信息有所增加。

但也有一个好消息,本考次起讲座部分由听后发卷改为听前发卷,从某种程度上讲又降低了此题型的答题难度。

2. Section B Conversation or Interview由原来的5道选择题增加到10道题,卷面问题消失。

这个真的比原来难了!新的测试形式规定,本部分由一个约1 000个单词的会话或两个约500个单词的会话组成。

会话后有10道多项选择题。

本部分每道题后有10秒的间隙,要求考生听到问题后从所给的四个选项中选出一个最佳答案。

本部分内容的选材与学生的日常生活、社会和学习活动相关。