2013年ADA糖尿病诊疗指南

- 格式:doc

- 大小:133.00 KB

- 文档页数:25

2013年ADA糖尿病诊疗指南美国糖尿病协会目前糖尿病的诊断标准l A1C≥6.5%。

试验应该用美国糖化血红蛋白标准化计划组织(National Glycohemoglobin Standardiz ation Program,NGSP)认证的方法进行,并与糖尿病控制和并发症研究(Diabetes Control and Complica tions Trial,DCCT)的检测进行标化。

或海南医学院附属医院内分泌科王新军l 空腹血糖(FPG)≥7.0 mmol/L。

空腹的定义是至少8小时未摄入热量。

或l 口服糖耐量试验(OGTT)2h血糖≥11.1 mmol/L。

试验应按世界卫生组织(WHO)的标准进行,用相当于75 g无水葡萄糖溶于水作为糖负荷。

或l 在有高血糖典型症状或高血糖危象的患者,随机血糖≥11.1 mmol/L。

l 如无明确的高血糖,结果应重复检测确认。

在无症状患者中筛查糖尿病●在无症状的成人,如超重或肥胖(BMI≥25kg/m2)并有一个以上其他糖尿病危险因素(见“2013年糖尿病诊疗标准”中的表4),应该从任何年龄开始筛查2型糖尿病和糖尿病前期。

对没有这些危险因素的人群,应从45岁开始筛查。

(B)●如果检查结果正常,至少每3年复查一次。

(E)●为筛查糖尿病或糖尿病前期,A1C、FPG或75g 2h OGTT均可使用。

(B)●对于糖尿病前期的人群,应该进一步评估并治疗其他心血管疾病(CVD)危险因素。

(B)在儿童中筛查2型糖尿病l 在超重并有2项或2项以上其他糖尿病危险因素(见“2013年糖尿病诊疗标准”中的表5)的儿童和青少年,应考虑筛查2型糖尿病。

(E)筛查1型糖尿病考虑将1型糖尿病的相关亲属转诊到临床研究机构检测抗体以行风险评估。

(E)妊娠期糖尿病的筛查和诊断●在有危险因素的个体,产前首次就诊时用标准的诊断方法筛查未诊断的2型糖尿病。

(B)●在无糖尿病史的孕妇,妊娠24~28周用75g 2h OGTT筛查妊娠糖尿病,诊断切点见“2013年糖尿病诊疗标准”表6。

中国 2 型糖尿病防治指南(2013 年版)1. 序翁建平千百年来医学不断探索,寻找治疗人类疾病的良方,探索的脚步从未停息。

提高人们的生活质量,延长生命一直是医者的神圣使命。

随着经济高速发展和工业化进程的加速,生活方式的改变和老龄化进程的加速,使我国糖尿病的患病率正呈快速上升的趋势,成为继心脑血管疾病、肿瘤之后另一个严重危害人民健康的重要慢性非传染性疾病。

据世界卫生组织估计,2005 到2015 年间中国由于糖尿病及相关心血管疾病导致的经济损失达5577 亿美元。

而近年的多项调查表明:无论是欧美发达国家还是发展中国家如中国,糖尿病控制状况均不容乐观。

我国党和政府十分重视以糖尿病为代表的慢性非传染性疾病的防治工作,糖尿病和高血压患者的管理自2009 年开始作为促进基本公共卫生服务均等化的重要措施,纳人深化医疗卫生体制改革的3 年实施方案。

为遏制糖尿病病魔肆虐,长期以来,中华医学会糖尿病学分会与世界各国的同仁一起为防治糖尿病做着孜孜不倦的努力,开展了大量糖尿病宣传教育、流行病学调查、预防与治疗研究和临床工作。

临床工作的规范化是糖尿病及其并发症防治取得成功的重要保证,指南是临床工作规范化的学术文件和依据。

自2003 年开始,中华医学会糖尿病学分会组织全国专家编写了《中国2 型糖尿病防治指南》,此后又于2007 年和2010 年予以更新。

指南不同于教科书,指南是重视指导性和可操作性的学术文件;指南也不是一成不变的“圣经”,而是与时俱进、不断更新的指导性文件。

近年来,我国糖尿病领域研究进展十分迅速,取得了一批成果,这些研究已对临床工作产生了较大影响。

有鉴于此,中华医学会糖尿病学分会第七届委员会再一次组织全国专家修订了《中国2 型糖尿病防治指南》,以适应当今日新月异的糖尿病防治工作需要。

2013 年修订版是在2010 年的基础上,根据我国糖尿病流行趋势和循证医学研究的进展,以循证医学为理论基础,既参考了国内外流行病学资料、近年的临床试验成果及相关的指导性文件,又结合了我国糖尿病防治的实践和研究数据,广泛征求各方意见,由近百位专家集体讨论和编写,历时两年完成的。

2013美国糖尿病学会糖尿病医学诊治标准更新内容解读李静,童南伟(四川大学华西医院 内分泌代谢科,成都 610041)通讯作者:童南伟 E-mail: buddyjun@糖尿病是一种慢性疾病,需要长期治疗和患者自我管理的教育及支持。

美国糖尿病学会(ADA )从1998年开始发布糖尿病医学诊治标准(以下简称标准),并从2002年开始每年初依据最新的证据进行更新。

最新的标准已于2013年初发表。

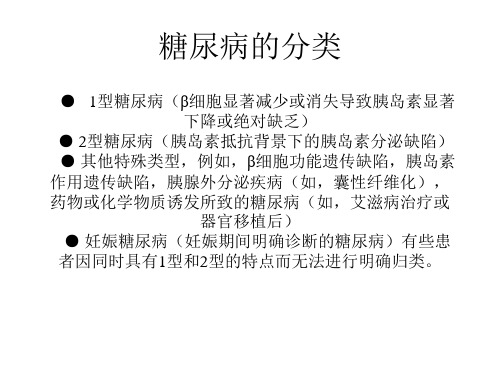

2013标准与2012标准[16]相同,共分为10大部分:Ⅰ:糖尿病的分型和诊断;Ⅱ:无症状患者糖尿病的筛查;Ⅲ:妊娠糖尿病(gestational diabetes mellitus ,GDM )的筛查和诊断;Ⅳ:2型糖尿病的预防和延缓;Ⅴ:糖尿病的诊治;Ⅵ:糖尿病并发症的预防和管理;Ⅶ:糖尿病常见合并症的评估;Ⅷ:特殊人群的糖尿病诊治;Ⅸ:特殊情况下的糖尿病处理;Ⅹ:改善糖尿病诊治水平的策略[1]。

本文将就2013标准相对于2012标准所做的更新做一简单的介绍。

为便于读者参照原文,本文将每条建议在2013标准中的位置列出,所使用的符号与原文一致。

如Ⅴ.C.1.a 中Ⅴ代表第五大部分(1级标题)即糖尿病的诊治,C (2级标题)代表糖尿病诊治中的第三部分——血糖控制,1(3级标题)代表血糖控制中的第一部分即血糖控制的评估,a (4级标题)代表该部分中的血糖监测。

并附上ADA 临床实践建议的证据分级评价系统(见表1)。

1 2013标准删除的建议(1)Ⅴ.C.1.a :每日注射胰岛素次数较少、非胰岛治疗或单用医学营养治疗(MNT )的患者,自我监测血糖(SMBG )可能有助于糖尿病的管理(E )。

对于SMBG 在非胰岛治疗中的使用是有争议的。

几个随机研究的结果都对非胰岛素治疗患者进行常规SMBG 的临床获益和成本效益提出质疑[2-4],一个最新的荟萃分析[5]也与一个Cochrane 系统评价[6]结果不一致。

故新的标准因缺乏证据删除该建议。

Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes d2013A MERICAN D IABETES A SSOCIATIOND iabetes mellitus is a chronic illnessthat requires continuing medical careand ongoing patient self-management education and support to prevent acute complications and to reduce the risk of long-term complications.Diabetes care is complex and requires multifactorial risk reduction strategies beyond glycemic con-trol.A large body of evidence exists that supports a range of interventions to improve diabetes outcomes.These standards of care are intended to provide clinicians,patients,researchers, payers,and other interested individuals with the components of diabetes care, general treatment goals,and tools to eval-uate the quality of care.Although individ-ual preferences,comorbidities,and other patient factors may require modification of goals,targets that are desirable for most patients with diabetes are provided.Spe-cifically titled sections of the standards address children with diabetes,pregnant women,and people with prediabetes. These standards are not intended to pre-clude clinical judgment or more extensive evaluation and management of the patient by other specialists as needed.For more detailed information about management of diabetes,refer to references(1–3).The recommendations included are screening,diagnostic,and therapeutic actions that are known or believed to favorably affect health outcomes of patients with diabetes.A large number of these interventions have been shown to be cost-effective(4).A grading system(Table1), developed by the American Diabetes Asso-ciation(ADA)and modeled after existing methods,was utilized to clarify and codify the evidence that forms the basis for the recommendations.The level of evidence that supports each recommendation is listed after each recommendation using the letters A,B,C,or E.These standards of care are revisedannually by the ADA’s multidisciplinaryProfessional Practice Committee,incor-porating new evidence.For the currentrevision,committee members systemati-cally searched Medline for human stud-ies related to each subsection andpublished since1January2011.Recom-mendations(bulleted at the beginningof each subsection and also listed inthe“Executive Summary:Standards ofMedical Care in Diabetes d2013”)wererevised based on new evidence or,insome cases,to clarify the prior recom-mendation or match the strength of thewording to the strength of the evidence.A table linking the changes in recom-mendations to new evidence can be re-viewed at http://professional.diabetes.org/CPR.As is the case for all positionstatements,these standards of care werereviewed and approved by the ExecutiveCommittee of ADA’s Board of Directors,which includes health care professionals,scientists,and lay people.Feedback from the larger clinicalcommunity was valuable for the2013revision of the standards.Readers whowish to comment on the“Standards ofMedical Care in Diabetes d2013”areinvited to do so at http://professional./CPR.Members of the Professional PracticeCommittee disclose all potentialfinan-cial conflicts of interest with industry.These disclosures were discussed at theonset of the standards revision meeting.Members of the committee,their em-ployer,and their disclosed conflicts ofinterest are listed in the“ProfessionalPractice Committee for the2013ClinicalPractice Recommendations”table(seep.S109).The ADA funds developmentof the standards and all its position state-ments out of its general revenues anddoes not use industry support for thesepurposes.I.CLASSIFICATION ANDDIAGNOSISA.ClassificationThe classification of diabetes includesfour clinical classes:c Type1diabetes(results from b-celldestruction,usually leading to absoluteinsulin deficiency)c Type2diabetes(results from a pro-gressive insulin secretory defect on thebackground of insulin resistance)c Other specific types of diabetes due toother causes,e.g.,genetic defects inb-cell function,genetic defects in in-sulin action,diseases of the exocrinepancreas(such as cysticfibrosis),anddrug-or chemical-induced(such as inthe treatment of HIV/AIDS or after or-gan transplantation)c Gestational diabetes mellitus(GDM)(diabetes diagnosed during pregnancythat is not clearly overt diabetes)Some patients cannot be clearly clas-sified as type1or type2diabetic.Clinicalpresentation and disease progression varyconsiderably in both types of diabetes.Occasionally,patients who otherwisehave type2diabetes may present withketoacidosis.Similarly,patients with type1diabetes may have a late onset and slow(but relentless)progression of diseasedespite having features of autoimmunedisease.Such difficulties in diagnosis mayoccur in children,adolescents,andadults.The true diagnosis may becomemore obvious over time.B.Diagnosis of diabetesFor decades,the diagnosis of diabetes wasbased on plasma glucose criteria,eitherthe fasting plasma glucose(FPG)or the2-h value in the75-g oral glucose toler-ance test(OGTT)(5).In2009,an International ExpertCommittee that included representativesof the ADA,the International Diabetesc c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c Originally approved1988.Most recent review/revision October2012.DOI:10.2337/dc13-S011©2013by the American Diabetes Association.Readers may use this article as long as the work is properly cited,the use is educational and not for profit,and the work is not altered.See / licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/for details.Federation(IDF),and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD)recommended the use of the A1C test to diagnose diabetes,with a threshold of$6.5%(6),and the ADA adopted this criterion in2010(5).The diagnostic test should be performed using a method that is certified by the NGSP and standardized or traceable to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial(DCCT)reference as-say.Although point-of-care(POC)A1C as-says may be NGSP certified,proficiency testing is not mandated for performing the test,so use of these assays for diagnostic purposes could be problematic.Epidemiological datasets show a sim-ilar relationship for A1C to the risk of retinopathy as has been shown for the corresponding FPG and2-h PG thresh-olds.The A1C has several advantages to the FPG and OGTT,including greater convenience(since fasting is not required), evidence to suggest greater preanalytical stability,and less day-to-day perturbations during periods of stress and illness.These advantages must be balanced by greater cost,the limited availability of A1C testing in certain regions of the developing world, and the incomplete correlation between A1C and average glucose in certain indi-viduals.In addition,HbA1c levels may vary with patients’race/ethnicity(7,8).Some have posited that glycation rates differ byrace(with,for example,African Americanshaving higher rates of glycation),but this iscontroversial.A recent epidemiologicalstudy found that,when matched for FPG,African Americans(with and without dia-betes)indeed had higher A1C than whites,but also had higher levels of fructosamineand glycated albumin and lower levels of1,5anhydroglucitol,suggesting that theirglycemic burden(particularly postpran-dially)may be higher(9).Epidemiologicalstudies forming the framework for recom-mending use of the A1C to diagnose diabe-tes have all been in adult populations.Whether the cut point would be the sameto diagnose children or adolescents withtype2diabetes is an area of uncertainty(3,10).A1C inaccurately reflects glycemiawith certain anemias and hemoglobinopa-thies.For patients with an abnormal hemo-globin but normal red cell turnover,such assickle cell trait,an A1C assay without inter-ference from abnormal hemoglobins shouldbe used(an updated list is available at www./interf.asp).For conditions withabnormal red cell turnover,such as preg-nancy,recent blood loss or transfusion,orsome anemias,the diagnosis of diabetesmust employ glucose criteria exclusively.The established glucose criteria forthe diagnosis of diabetes(FPG and2-hPG)remain valid as well(Table2).Just asthere is less than100%concordance be-tween the FPG and2-h PG tests,there isno perfect concordance between A1C andeither glucose-based test.Analyses of theNational Health and Nutrition Examina-tion Survey(NHANES)data indicate that,assuming universal screening of the un-diagnosed,the A1C cut point of$6.5%identifies one-third fewer cases of undiag-nosed diabetes than a fasting glucose cutpoint of$126mg/dL(7.0mmol/L)(11),and numerous studies have confirmedthat at these cut points the2-h OGTTvalue diagnoses more screened peoplewith diabetes(12).However,in practice,alarge portion of the diabetic population re-mains unaware of its condition.Thus,thelower sensitivity of A1C at the designatedcut point may well be offset by the test’sgreater practicality,and wider applicationof a more convenient test(A1C)may actu-ally increase the number of diagnoses made.As with most diagnostic tests,a testresult diagnostic of diabetes should berepeated to rule out laboratory error,unless the diagnosis is clear on clinicalgrounds,such as a patient with a hyper-glycemic crisis or classic symptoms ofhyperglycemia and a random plasmaglucose$200mg/dL.It is preferablethat the same test be repeated for confir-mation,since there will be a greater likeli-hood of concurrence in this case.Forexample,if the A1C is7.0%and a repeatresult is6.8%,the diagnosis of diabetes isconfirmed.However,if two different tests(such as A1C and FPG)are both above thediagnostic thresholds,the diagnosis of di-abetes is also confirmed.On the other hand,if two differenttests are available in an individual and theresults are discordant,the test whose resultis above the diagnostic cut point should berepeated,and the diagnosis is made basedon the confirmed test.That is,if a patientmeets the diabetes criterion of the A1C(tworesults$6.5%)but not the FPG(,126mg/dL or7.0mmol/L),or vice versa,that per-son should be considered to have diabetes.Since there is preanalytical and ana-lytical variability of all the tests,it is alsopossible that when a test whose result wasabove the diagnostic threshold is re-peated,the second value will be belowthe diagnostic cut point.This is leastlikely for A1C,somewhat more likely forFPG,and most likely for the2-h PG.Barring a laboratory error,such patientsare likely to have test results near themargins of the threshold for a diagnosis.The health care professional might opt toTable1d ADA evidence grading system for clinical practice recommendationsLevel ofevidence DescriptionA Clear evidence from well-conducted,generalizable RCTs that are adequatelypowered,including:c Evidence from a well-conducted multicenter trialc Evidence from a meta-analysis that incorporated quality ratings in theanalysisCompelling nonexperimental evidence,i.e.,“all or none”rule developed by theCentre for Evidence-Based Medicine at the University of OxfordSupportive evidence from well-conducted RCTs that are adequately powered,including:c Evidence from a well-conducted trial at one or more institutionsc Evidence from a meta-analysis that incorporated quality ratings in the analysis B Supportive evidence from well-conducted cohort studiesc Evidence from a well-conducted prospective cohort study or registryc Evidence from a well-conducted meta-analysis of cohort studiesSupportive evidence from a well-conducted case-control studyC Supportive evidence from poorly controlled or uncontrolled studiesc Evidence from randomized clinical trials with one or more major or three ormore minor methodologicalflaws that could invalidate the resultsc Evidence from observational studies with high potential for bias(such as caseseries with comparison with historical controls)c Evidence from case series or case reportsConflicting evidence with the weight of evidence supporting the recommendation E Expert consensus or clinical experiencePosition Statementfollow the patient closely and repeat the testing in3–6months.The current diagnostic criteria for diabetes are summarized in Table2.C.Categories of increased riskfor diabetes(prediabetes)In1997and2003,the Expert Committee on Diagnosis and Classification of Diabe-tes Mellitus(13,14)recognized an inter-mediate group of individuals whose glucose levels,although not meeting cri-teria for diabetes,are nevertheless too high to be considered normal.These per-sons were defined as having impaired fast-ing glucose(IFG)(FPG levels100mg/dL [5.6mmol/L]to125mg/dL[6.9mmol/L]) or impaired glucose tolerance(IGT)(2-h values in the OGTT of140mg/dL[7.8 mmol/L]to199mg/dL[11.0mmol/L]).It should be noted that the World Health Organization(WHO)and a number of other diabetes organizations define the cut-off for IFG at110mg/dL(6.1mmol/L).Individuals with IFG and/or IGT have been referred to as having prediabetes, indicating the relatively high risk for the future development of diabetes.IFG and IGT should not be viewed as clinical entities in their own right but rather risk factors for diabetes as well as cardiovascular disease(CVD).IFG and IGT are associated with obesity(especially abdominal or vis-ceral obesity),dyslipidemia with high tri-glycerides and/or low HDL cholesterol,and hypertension.As is the case with the glucose mea-sures,several prospective studies that used A1C to predict the progression todiabetes demonstrated a strong,continu-ous association between A1C and sub-sequent diabetes.In a systematic review of44,203individuals from16cohort stud-ies with a follow-up interval averaging5.6years(range2.8–12years),those with anA1C between5.5and6.0%had a substan-tially increased risk of diabetes with5-yearincidences ranging from9to25%.An A1Crange of6.0–6.5%had a5-year risk of de-veloping diabetes between25to50%andrelative risk(RR)20times higher comparedwith an A1C of5.0%(15).In a community-based study of black and white adultswithout diabetes,baseline A1C was astronger predictor of subsequent diabetesand cardiovascular events than was fast-ing glucose(16).Other analyses suggestthat an A1C of5.7%is associated withdiabetes risk similar to that in the high-risk participants in the Diabetes PreventionProgram(DPP)(17).Hence,it is reasonable to consider anA1C range of5.7–6.4%as identifying in-dividuals with prediabetes.As is the casefor individuals found to have IFG andIGT,individuals with an A1C of5.7–6.4%should be informed of their increased riskfor diabetes as well as CVD and counseledabout effective strategies to lower their risks(see Section IV).As with glucose measure-ments,the continuum of risk is curvilinear,so that as A1C rises,the risk of diabetes risesdisproportionately(15).Accordingly,inter-ventions should be most intensive andfollow-up particularly vigilant for thosewith A1Cs above6.0%,who should be con-sidered to be at very high risk.Table3summarizes the categories ofprediabetes.II.TESTING FOR DIABETES INASYMPTOMATIC PATIENTSRecommendationsc Testing to detect type2diabetes andprediabetes in asymptomatic peopleshould be considered in adults of anyage who are overweight or obese(BMI$25kg/m2)and who have one or moreadditional risk factors for diabetes(Table4).In those without these risk factors,testing should begin at age45.(B)c If tests are normal,repeat testing at leastat3-year intervals is reasonable.(E)c To test for diabetes or prediabetes,theA1C,FPG,or75-g2-h OGTT are appro-priate.(B)c In those identified with prediabetes,identify and,if appropriate,treat otherCVD risk factors.(B)For many illnesses,there is a major dis-tinction between screening and diagnostictesting.However,for diabetes,the sametests would be used for“screening”as fordiagnosis.Diabetes may be identified any-where along a spectrum of clinical scenar-ios ranging from a seemingly low-riskindividual who happens to have glucosetesting,to a higher-risk individual whomthe provider tests because of high suspicionof diabetes,to the symptomatic patient.The discussion herein is primarily framedas testing for diabetes in those withoutsymptoms.The same assays used for test-ing for diabetes will also detect individualswith prediabetes.A.Testing for type2diabetes andrisk of future diabetes in adultsPrediabetes and diabetes meet establishedcriteria for conditions in which early de-tection is appropriate.Both conditions arecommon,increasing in prevalence,andimpose significant public health burdens.There is a long presymptomatic phasebefore the diagnosis of type2diabetes isusually made.Relatively simple tests areavailable to detect preclinical disease.Ad-ditionally,the duration of glycemic burdenis a strong predictor of adverse outcomes,and effective interventions exist to preventprogression of prediabetes to diabetes(seeSection IV)and to reduce risk of compli-cations of diabetes(see Section VI).Type2diabetes is frequently not di-agnosed until complications appear,andapproximately one-fourth of all peoplewith diabetes in the U.S.may be undiag-nosed.The effectiveness of early identifica-tion of prediabetes and diabetes throughmass testing of asymptomatic individualshas not been proven definitively,andrigorous trials to provide such proof areunlikely to occur.In a large randomizedcontrolled trial(RCT)in Europe,generalpractice patients between the ages of40–69years were screened for diabetes andTable2d Criteria for the diagnosis of diabetesA1C$6.5%.The test should be performed in a laboratory using a method that is NGSP certified and standardized to the DCCT assay.*ORFPG$126mg/dL(7.0mmol/L).Fasting is defined as no caloric intake for at least8h.*OR2-h plasma glucose$200mg/dL(11.1mmol/L) during an OGTT.The test should be performed as described by the WHO,using a glucose load containing the equivalent of 75g anhydrous glucose dissolved in water.*ORIn a patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis,a random plasma glucose$200mg/dL(11.1mmol/L).*In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia,re-sult should be confirmed by repeat testing.Table3d Categories of increased risk for diabetes(prediabetes)*FPG100mg/dL(5.6mmol/L)to125mg/dL (6.9mmol/L)(IFG)OR2-h plasma glucose in the75-g OGTT140mg/dL (7.8mmol/L)to199mg/dL(11.0mmol/L) (IGT)ORA1C5.7–6.4%*For all three tests,risk is continuous,extending be-low the lower limit of the range and becoming dis-proportionately greater at higher ends of the range.Position Statementthen randomly assigned by practice to routine care of diabetes or intensive treat-ment of multiple risk factors.After5.3 years of follow-up,CVD risk factors were modestly but significantly more improved with intensive treatment.Incidence offirst CVD event and mortality rates were not significantly different between groups (18).This study would seem to add sup-port for early treatment of screen-detected diabetes,as risk factor control was excel-lent even in the routine treatment arm and both groups had lower event rates than predicted.The absence of a control unscreened arm limits the ability to defi-nitely prove that screening impacts out-comes.Mathematical modeling studies suggest that screening independent of risk factors beginning at age30years or age45years is highly cost-effective (,$11,000per quality-adjusted life-year gained)(19).Recommendations for testing for di-abetes in asymptomatic,undiagnosed adults are listed in Table4.Testing should be considered in adults of any age with BMI$25kg/m2and one or more of the known risk factors for diabetes.In addi-tion to the listed risk factors,certain med-ications,such as glucocorticoids and antipsychotics(20),are known to in-crease the risk of type2diabetes.There is compelling evidence that lower BMI cut points suggest diabetes risk in some racial and ethnic groups.In a large multiethnic cohort study,for an equivalent incidence rate of diabetes conferred by a BMI of30 kg/m2in whites,the BMI cutoff value was 24kg/m2in South Asians,25kg/m2inChinese,and26kg/m2in African Ameri-cans(21).Disparities in screening rates,not explainable by insurance status,arehighlighted by evidence that despitemuch higher prevalence of type2diabe-tes,non-Caucasians in an insured popu-lation are no more likely than Caucasiansto be screened for diabetes(22).Becauseage is a major risk factor for diabetes,test-ing of those without other risk factorsshould begin no later than age45years.The A1C,FPG,or the2-h OGTT areappropriate for testing.It should be notedthat the tests do not necessarily detectdiabetes in the same individuals.Theefficacy of interventions for primary pre-vention of type2diabetes(23–29)hasprimarily been demonstrated among in-dividuals with IGT,not for individualswith isolated IFG or for individuals withspecific A1C levels.The appropriate interval betweentests is not known(30).The rationalefor the3-year interval is that false nega-tives will be repeated before substantialtime elapses,and there is little likelihoodthat an individual will develop significantcomplications of diabetes within3yearsof a negative test result.In the modelingstudy,repeat screening every3or5yearswas cost-effective(19).Because of the need for follow-up anddiscussion of abnormal results,testingshould be carried out within the healthcare munity screening outsidea health care setting is not recommendedbecause people with positive tests may notseek,or have access to,appropriate follow-uptesting and care.Conversely,there may befailure to ensure appropriate repeat testingfor individuals who test mu-nity screening may also be poorly targeted;i.e.,it may fail to reach the groups most at riskand inappropriately test those at low risk(theworried well)or even those already diag-nosed.B.Screening for type2diabetesin childrenRecommendationsc Testing to detect type2diabetes andprediabetes should be considered in chil-dren and adolescents who are overweightand who have two or more additionalrisk factors for diabetes(Table5).(E)The incidence of type2diabetes inadolescents has increased dramatically inthe last decade,especially in minoritypopulations(31),although the diseaseremains rare in the general pediatric pop-ulation(32).Consistent with recom-mendations for adults,children andyouth at increased risk for the presenceor the development of type2diabetesshould be tested within the health caresetting(33).The recommendations ofthe ADA consensus statement“Type2Diabetes in Children and Adolescents,”with some modifications,are summa-rized in Table5.C.Screening for type1diabetesRecommendationsc Consider referring relatives of thosewith type1diabetes for antibody test-ing for risk assessment in the settingof a clinical research study.(E)Generally,people with type1diabetespresent with acute symptoms of diabetesand markedly elevated blood glucoselevels,and some cases are diagnosed withlife-threatening ketoacidosis.Evidencefrom several studies suggests that mea-surement of islet autoantibodies in rela-tives of those with type1diabetesidentifies individuals who are at risk fordeveloping type1diabetes.Such testing,coupled with education about symptomsof diabetes and follow-up in an observa-tional clinical study,may allow earlieridentification of onset of type1diabetesand lessen presentation with ketoacidosisat time of diagnosis.This testing may beappropriate in those who have relativeswith type1diabetes,in the context ofTable4d Criteria for testing for diabetes in asymptomatic adult individuals1.Testing should be considered in all adults who are overweight(BMI$25kg/m2*)and have additional risk factors:c physical inactivitycfirst-degree relative with diabetesc high-risk race/ethnicity(e.g.,African American,Latino,Native American,AsianAmerican,Pacific Islander)c women who delivered a baby weighing.9lb or were diagnosed with GDMc hypertension($140/90mmHg or on therapy for hypertension)c HDL cholesterol level,35mg/dL(0.90mmol/L)and/or a triglyceridelevel.250mg/dL(2.82mmol/L)c women with polycystic ovary syndromec A1C$5.7%,IGT,or IFG on previous testingc other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance(e.g.,severe obesity,acanthosis nigricans)c history of CVD2.In the absence of the above criteria,testing for diabetes should begin at age45years.3.If results are normal,testing should be repeated at least at3-year intervals,withconsideration of more frequent testing depending on initial results(e.g.,those withprediabetes should be tested yearly)and risk status.*At-risk BMI may be lower in some ethnic groups.Position Statementclinical research studies(see,for example, ).However, widespread clinical testing of asymptomatic low-risk individuals cannot currently be recommended,as it would identify very few individuals in the general population who are at risk.Individuals who screen positive should be counseled about their risk of developing diabetes and symptoms of diabetes,followed closely to prevent de-velopment of diabetic ketoacidosis,and informed about clinical trials.Clinical studies are being conducted to test various methods of preventing type1diabetes in those with evidence of autoimmunity. Some interventions have demonstrated modest efficacy in slowing b-cell loss early in type1diabetes(34,35),and further re-search is needed to determine whether they may be effective in preventing type 1diabetes.III.DETECTION AND DIAGNOSIS OF GDM Recommendationsc Screen for undiagnosed type2diabetes at thefirst prenatal visit in those with risk factors,using standard diagnostic criteria.(B)c In pregnant women not previously known to have diabetes,screen forGDM at24–28weeks of gestation,using a75-g2-h OGTT and the di-agnostic cut points in Table6.(B)c Screen women with GDM for persistentdiabetes at6–12weeks postpartum,using the OGTT and nonpregnancydiagnostic criteria.(E)c Women with a history of GDM shouldhave lifelong screening for the de-velopment of diabetes or prediabetes atleast every3years.(B)c Women with a history of GDM foundto have prediabetes should receivelifestyle interventions or metformin toprevent diabetes.(A)For many years,GDM was defined asany degree of glucose intolerance withonset orfirst recognition during preg-nancy(13),whether or not the conditionpersisted after pregnancy,and not ex-cluding the possibility that unrecognizedglucose intolerance may have antedatedor begun concomitantly with the preg-nancy.This definition facilitated a uniformstrategy for detection and classification ofGDM,but its limitations were recognizedfor many years.As the ongoing epidemicof obesity and diabetes has led to moretype2diabetes in women of childbearingage,the number of pregnant women withundiagnosed type2diabetes has increased(36).Because of this,it is reasonable toscreen women with risk factors for type2diabetes(Table4)for diabetes at theirinitial prenatal visit,using standard diag-nostic criteria(Table2).Women with di-abetes found at this visit should receivea diagnosis of overt,not gestational,diabetes.GDM carries risks for the mother andneonate.The Hyperglycemia and Ad-verse Pregnancy Outcome(HAPO)study(37),a large-scale(;25,000pregnantwomen)multinational epidemiologicalstudy,demonstrated that risk of adversematernal,fetal,and neonatal outcomescontinuously increased as a function ofmaternal glycemia at24–28weeks,evenwithin ranges previously considered nor-mal for pregnancy.For most complica-tions,there was no threshold for risk.These results have led to careful recon-sideration of the diagnostic criteria forGDM.After deliberations in2008–2009,the International Association ofDiabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups(IADPSG),an international consensusgroup with representatives from multipleobstetrical and diabetes organizations,including ADA,developed revised rec-ommendations for diagnosing GDM.The group recommended that all womennot known to have prior diabetesundergo a75-g OGTT at24–28weeksof gestation.Additionally,the group de-veloped diagnostic cut points for the fast-ing,1-h,and2-h plasma glucosemeasurements that conveyed an oddsratio for adverse outcomes of at least1.75compared with women with themean glucose levels in the HAPO study.Current screening and diagnostic strate-gies,based on the IADPSG statement(38),are outlined in Table6.These new criteria will significantlyincrease the prevalence of GDM,primar-ily because only one abnormal value,nottwo,is sufficient to make the diagnosis.The ADA recognizes the anticipated sig-nificant increase in the incidence of GDMdiagnosed by these criteria and is sensitiveto concerns about the“medicalization”ofpregnancies previously categorized as nor-mal.These diagnostic criteria changes arebeing made in the context of worrisomeworldwide increases in obesity and diabe-tes rates,with the intent of optimizing ges-tational outcomes for women and theirbabies.Admittedly,there are few data fromrandomized clinical trials regarding ther-apeutic interventions in women who willnow be diagnosed with GDM based ononly one blood glucose value above theTable5d Testing for type2diabetes in asymptomatic children*Criteriac Overweight(BMI.85th percentile for age and sex,weight for height.85th percentile,orweight.120%of ideal for height)Plus any two of the following risk factors:c Family history of type2diabetes infirst-or second-degree relativec Race/ethnicity(Native American,African American,Latino,Asian American,PacificIslander)c Signs of insulin resistance or conditions associated with insulin resistance(acanthosisnigricans,hypertension,dyslipidemia,polycystic ovary syndrome,or small-for-gestational-age birth weight)c Maternal history of diabetes or GDM during the child’s gestationAge of initiation:age10years or at onset of puberty,if puberty occurs at a younger ageFrequency:every3years*Persons aged18years and younger.Table6d Screening for and diagnosis of GDMPerform a75-g OGTT,with plasma glucose measurement fasting and at1and2h,at24–28weeks of gestation in women not previously diagnosed with overt diabetes.The OGTT should be performed in the morning after an overnight fast of at least8h.The diagnosis of GDM is made when any of the following plasma glucose values are exceeded:c Fasting:$92mg/dL(5.1mmol/L)c1h:$180mg/dL(10.0mmol/L)c2h:$153mg/dL(8.5mmol/L)Position Statement。

2013年ADA糖尿病诊疗指南(转载)发表者:吴敏 (访问人次:272)目前糖尿病的诊断标准l A1C≥6.5%。

试验应该用美国糖化血红蛋白标准化计划组织(National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program,NGSP)认证的方法进行,并与糖尿病控制和并发症研究(Diabetes Control and Complications Trial,DCCT)的检测进行标化。

或空腹血糖(FPG)≥7.0 mmol/L。

空腹的定义是至少8小时未摄入热量。

或口服糖耐量试验(OGTT)2h血糖≥11.1 mmol/L。

试验应按世界卫生组织(WHO)的标准进行,用相当于75 g无水葡萄糖溶于水作为糖负荷。

或在有高血糖典型症状或高血糖危象的患者,随机血糖≥11.1 mmol/L。

如无明确的高血糖,结果应重复检测确认。

在无症状患者中筛查糖尿病●在无症状的成人,如超重或肥胖(BMI≥25kg/m2)并有一个以上其他糖尿病危险因素(见“2013年糖尿病诊疗标准”中的表4),应该从任何年龄开始筛查2型糖尿病和糖尿病前期。

对没有这些危险因素的人群,应从45岁开始筛查。

(B)●如果检查结果正常,至少每3年复查一次。

(E)●为筛查糖尿病或糖尿病前期,A1C、FPG或75g 2h OGTT均可使用。

(B)●对于糖尿病前期的人群,应该进一步评估并治疗其他心血管疾病(CVD)危险因素。

(B)在儿童中筛查2型糖尿病l 在超重并有2项或2项以上其他糖尿病危险因素(见“2013年糖尿病诊疗标准”中的表5)的儿童和青少年,应考虑筛查2型糖尿病。

(E)筛查1型糖尿病考虑将1型糖尿病的相关亲属转诊到临床研究机构检测抗体以行风险评估。

(E)妊娠期糖尿病的筛查和诊断●在有危险因素的个体,产前首次就诊时用标准的诊断方法筛查未诊断的2型糖尿病。

(B)●在无糖尿病史的孕妇,妊娠24~28周用75g 2h OGTT筛查妊娠糖尿病,诊断切点见“2013年糖尿病诊疗标准”表6。

(B)●妊娠糖尿病的妇女在产后6~12周用OGTT及非妊娠标准筛查永久性糖尿病。

(E)●有妊娠糖尿病病史的妇女应至少每3年筛查是否发展为糖尿病或糖尿病前期。

(B)●如发现有妊娠糖尿病病史的妇女为糖尿病前期,应接受生活方式干预或二甲双胍治疗以预防糖尿病(A)预防/延缓2型糖尿病●对于糖耐量异常(IGT)(A)、空腹血糖受损(IFG)(E)或A1C 在5.7~6.4%之间(E)的患者,应转诊到具有有效持续支持计划的单位,减轻体重7%,增加体力活动,每周进行至少150分钟中等强度(如步行)的体力活动。

●定期随访咨询非常重要。

(B)●基于糖尿病预防的花费效益比,这种咨询的费用应由第三方支付。

(B)●对于IGT(A)、IFG(E)或A1C 在5.7~6.4%之间(E),特别是那些BMI >35kg/m2,年龄<60岁和以前有GDM的妇女,可以考虑使用二甲双胍治疗预防2型糖尿病。

(A)●建议糖尿病前期患者应该每年进行检测以观察是否进展为糖尿病。

(E)●筛查并治疗相关CVD危险因素。

(B)血糖监测●采用每日多次胰岛素注射(MDI)或胰岛素泵治疗的患者,应该进行自我检测血糖(SMBG),至少在每餐前均检测,偶尔在餐后、睡前、锻炼前、怀疑低血糖、低血糖治疗后直到血糖正常、在关键任务如驾驶操作前检测。

(B)●对于胰岛素注射次数少、非胰岛素治疗的患者,处方SMBG作为教育内容的一部分或许有助指导治疗和/或患者自我管理。

(E)●处方SMBG后,应确保患者获得SMBG持续技术支持并定期评估其SMBG技术和SMBG结果以及他们用SMBG数据调整治疗的能力。

(E)●对于部分年龄25岁以上的1型糖尿病患者进行动态血糖监测(CGM)并联合胰岛素强化治疗,是降低A1C的有效方法。

(A)●虽然CGM在儿童、青少年和青年患者中降低A1C的证据不强,但CGM或许有对该人群有所帮助。

是否成功与这种仪器持续使用的依从性具有相关性。

(C)●在无症状低血糖和/或频发低血糖的患者,CGM可作为SMBG的一种辅助工具。

(E)A1C●对于治疗达标(血糖控制稳定)的患者,每年应该至少检测两次A1C。

(E)●对更改治疗方案或血糖控制未达标患者,应每年进行四次A1C检测。

(E)●应用即时A1C检测有助更及时更改治疗方案。

(E)成人的血糖目标●已有证据显示降低A1C到7%左右或以下可减少糖尿病微血管并发症,如果在诊断糖尿病后立即良好控制血糖,可以减少远期大血管疾病。

所以,在许多非妊娠成人合理的A1C控制目标是<7%。

(B)●如果某些患者无明显的低血糖或其他治疗副作用,建议更严格的A1C目标(如<6.5%)或许也是合理的。

这些患者或许包括那些糖尿病病程较短、预期寿命较长和无明显心血管并发症者。

(C)●对于有严重低血糖病史、预期寿命有限、有晚期微血管或大血管病并发症、有较多的伴发病及糖尿病病程较长的患者,尽管实施了糖尿病自我管理教育、合理的血糖检测、应用了包括胰岛素在内的多种有效剂量的降糖药物,而血糖仍难达标者,较宽松的A1C目标(如<8%)或许是合理的。

(B)药物和整体治疗方案1型糖尿病的胰岛素治疗l 大多数1型糖尿病患者应该用MDI注射(每天注射3到4次基础和餐时胰岛素)或连续皮下胰岛素输注(CSII)方案治疗。

(A)l 应该教育大多数1型糖尿病患者如何根据碳水化合物摄入量、餐前血糖和运动调整餐前胰岛素剂量。

(E)l 大多数1型糖尿病患者应该使用胰岛素类似物以减少低血糖风险。

(A)l 1型糖尿病患者考虑筛查其他自身免疫性疾病(甲状腺、维生素B12缺乏、乳糜症)。

(B)2型糖尿病的降糖药物治疗●糖尿病一经诊断,起始首选生活方式干预和二甲双胍(如果可以耐受)治疗,除非有二甲双胍的禁忌症(A)。

●在新诊断的2型糖尿病患者,如有明显的高血糖症状和/或血糖及A1C水平明显升高,一开始即考虑胰岛素治疗,加或不加其他药物。

(E)●如果最大耐受剂量的非胰岛素单药治疗在3~6个月内不能达到或维持A1C 目标,加第二种口服药物、胰高血糖素样肽-1(GLP-1)受体激动剂或胰岛素。

(E)●药物的选择应该用以患者为中心的方案指导。

考虑的因素包括有效性、花费、潜在的副作用、对体重的影响、伴发病、低血糖风险和患者的喜好。

(E)●由于2型糖尿病是一种进行性疾病,大多数2型糖尿病患者最终需要胰岛素治疗。

(B)医学营养治疗整体建议●糖尿病前期及糖尿病患者需要依据治疗目标接受个体化的医学营养治疗(MNT),优先考虑由熟悉糖尿病MNT的注册营养师指导。

(A)●因为可以节省花费并可改善预后(B),MNT应该被保险公司及其他支付所充分覆盖。

(E)能量平衡、超重和肥胖●建议所有超重或肥胖的糖尿病患者或有糖尿病风险的个体减轻体重。

(A)●为减轻体重,低碳水化合物饮食、低脂卡路里限制饮食或地中海饮食在短期内(至少2年)或许有效。

(A)●对于低碳水化合物饮食的患者,监测其血脂、肾功能和蛋白质摄入(有肾病患者)情况,并及时调整降糖治疗方案。

(E)●体力活动和行为矫正是控制体重方案的重要组成部分,同时最有助于保持减轻的体重。

(B)糖尿病的一级预防建议●在有2型糖尿病风险的个体,预防措施重点强调生活方式的改变,包括适度减轻体重(体重的7%)和规律的体力活动(每周150分钟),饮食控制如减少热量摄入、低脂饮食能够减少发生2型糖尿病的风险。

(A)●有2型糖尿病风险的个体,应该鼓励食用美国农业部(USDA)推荐的纤维摄入量(14g纤维/1000千卡)及全谷食物(谷物中的一半)。

(B)●应该鼓励有2型糖尿病风险的个体限制含糖饮料的摄入。

(B)糖尿病的治疗建议糖尿病治疗中的宏量营养素●可以调整碳水化合物、蛋白质和脂肪的最佳比例,以满足糖尿病患者的代谢目标和个人喜好。

(C)●采用计算、食物交换份或经验估算来监测碳水化合物的摄入量,仍是血糖控制达标的关键。

(B)●饱和脂肪摄入量应少于总热量的7%。

(B)●减少反式脂肪摄入能降低LDL胆固醇,增加HDL胆固醇(A),所以应尽量减少反式脂肪的摄入。

(E)其他营养建议l 成年糖尿病患者如果想饮酒,每日饮酒量应适度(成年女性每天≤1份,成年男性≤2份),并应格外注意预防低血糖。

(E)l 不建议常规补充抗氧化剂如维生素E、C和胡萝卜素,因为缺乏有效性和长期安全性的证据。

(A)l个体化的饮食方案应包括优化食物选择,使所有微量元素符合推荐膳食许可量(RDA)/膳食参考摄入量(DRI)。

(E)糖尿病自我管理教育和支持l 糖尿病诊断确定后应根据需要按国家糖尿病自我管理教育和支持标准接受DSME和糖尿病自我管理支持(DSMS)。

(B)l 自我管理的效果和生活质量是DSME的主要指标,应该作为治疗的一部分进行评估和监测。

(C)l DSME和DSMS应该包括心理咨询,因为良好的情绪与糖尿病预后相关。

(C)l 糖尿病前期人群参加DSME和DSMS系统接受教育和支持以改善和保持良好的习惯是合适的,因为这可预防或延缓糖尿病的发病。

(C)l 因DSME可以节省花费并能改善预后(B),所以DSME和DSMS的费用应该由第三方支付者足额报销。

(E)体力活动l 糖尿病患者应该每周至少进行150 分钟中等强度有氧运动(最大心率的50%~70%),每周活动至少3天,不能连续超过2天不运动。

(A)l 鼓励无禁忌证的2型糖尿病患者每周进行至少2次耐力锻炼。

(A)心理评估与治疗l 心理学和社会状态的评估应是糖尿病治疗不可或缺的一部分。

(E)l 心理筛查和随访应包括但不限于:对疾病的态度、对治疗和预后的期望值、情感/情绪状态、一般及与糖尿病相关的生活质量、资源(经济、社会和情感方面)以及精神病史。

(E)l 当自我管理较差时,应筛查心理问题,如抑郁和糖尿病相关的压抑、焦虑、饮食障碍以及认知障碍等。

(C)低血糖l 有低血糖风险的患者在每次就诊时应该询问症状性和无症状性低血糖。

(C)l 无意识障碍的低血糖患者治疗首选治疗是葡萄糖(15~20g),也可选用其他含有葡萄糖的碳水化合物。

如果15分钟后SMBG依然为低血糖,应该重复上述措施。

SMBG血糖正常后,患者应该继续追加一次饮食或小吃,以预防低血糖复发。

(E)l所有具有明显严重低血糖风险的患者、照护者或家人均应给予胰高血糖素,并教会如何用药。

胰高血糖素不要求由专业人员治疗。

(E)l对于无症状低血糖或出现过一次或多次严重低血糖的糖尿病患者,应该重新评估其治疗方案。

(E)l用胰岛素治疗的患者如有未感知低血糖或严重低血糖发作,应该放宽血糖控制目标,严格避免近几周内再次发生低血糖,以降低无症状性低血糖并减少发生低血糖的风险。

(A)l低血糖风险增加的患者如发现认知功能较低或/和认知功能下降应由临床医生、患者和看护者持续评估其认知功能。