资本结构的决定因素【外文翻译】

- 格式:doc

- 大小:53.50 KB

- 文档页数:8

外文文献翻译译文一、外文原文原文:The Determinants of Capital Structure Choice The basic approach taken in previous empirical work has been to estimate regression equations with proxies for the unobservable theoretical attributes. This approach has a number of problems. First, there may be no unique representation of the attributes we wish to measure. There are often many possible proxies for a particular attribute, and researchers, lacking theoretical guidelines, may be tempted to select those variables that work best in terms of statistical goodness-of-fit criteria, thereby biasing their interpretation of the significance levels of their tests. Second, it is often difficult to find measures of particular attributes that are unrelated to other attributes that are of interest. Thus, selected proxy variables may be measuring the effects of several different attributes. Third, since the observed variables are imperfect representations of the attributes they are supposed to measure, their use in regression analysis introduces an errors-in-variable problem. Finally, measurement errors in the proxy variables may be correlated with measurement errors in the dependent variables, creating spurious correlations even when the unobserved attribute being measured is unrelated to the dependent variable.This study extends empirical work on capital structure theory in three ways. First, it extends the range of theoretical determinants of capital structure by examining some recently developed theories that have not, as yet, been analyzed empirically. Second, since some of these theories have different empirical implications with regard to different types of debt instruments, we analyze separate measures of short-term, long-term, and convertible debt rather than an aggregate measure of total debt. Third, a technique is used that explicitly recognizes and mitigates the measurement problems discussed above.This technique, which is an extension of the factor-analytic approach tomeasuring unobserved or latent variables, is known as linear structural modeling. Very briefly, this method assumes that, although the relevant attributes are not directly observable, we can observe a number of indicator variables that are linear functions of one or more attributes and a random error term. There is, in this specification, a direct analogy with the return-generating process assumed to hold in the Arbitrage Pricing Theory. While the identifying restrictions imposed on our model are different, the technique for estimating it is very similar to the procedure used by Roll and Ross to test the APT.Our results suggest that firms with unique or specialized products have relatively low debt ratios. Uniqueness is categorized by the firms' expenditures on research and development, selling expenses, and the rate at which employees voluntarily leave their jobs. We also find that smaller firms tend to use significantly more short-term debt than larger firms. Our model explains virtually none of the variation in convertible debt ratios across firms and finds no evidence to support theoretical work that predicts that debt ratios are related to a firm's expected growth, non-debt tax shields, volatility, or the collateral value of its assets. We do, however, find some support for the proposition that profitable firms have relatively less debt relative to the market value of their equity.Determinants of Capital StructureIn this section, we present a brief discussion of the attributes that different theories of capital structure suggest may affect the firm's debt-equity choice. These attributes are denoted asset structure, non-debt tax shields, growth, uniqueness, industry classification, size, earnings volatility, and profitability. The attributes, their relation to the optimal capital structure choice, and their observable indicators are discussed below.A. Collateral Value of AssetsMost capital structure theories argue that the type of assets owned by a firm in some way affects its capital structure choice. Scott suggests that, by selli secured debt, firms increase the value of their equity by expropriating wealth from their existing unsecured creditor. Arguments put forth by Myers and Majluf also suggest thatfirms may find it advantageous to sell secured debt. Their model demonstrates that there may be costs associated with issuing securities about which the firm's managers have better information than outside shareholders. Issuing debt secured by property with known values avoids these costs. For this reason, firms with assets that can be used as collateral may be expected to issue more debt to take advantage of this opportunity.Work by Galai and Masulis, Jensen and Meckling, and Myers suggests that stockholders of leveraged firms have an incentive to invest suboptimally to expropriate wealth from the firm's bondholders. This incentive may also induce a positive relation between debt xatios and the capacity of firms to collateralize their debt. If the debt can be collateralized, the borrower is restricted to use the funds for a specified project. Since no such guarantee can be used for projects that cannot be collateralized, creditors may require more favorable terms, which in turn may lead such firms to use equity rather than debt financing.The tendency of managers to consume more than the optimal level of perquisites may produce the opposite relation between collateralizable capital and debt levels. Grossman and Hart suggest that higher debt levels diminish this tendency because of the increased threat of bankruptcy. Managers of highly levered firms will also be less able to consume excessive perquisites since bondholders (or bankers) are inclined to closely monitor such firms. The costs associated with this agency relation may be higher for firms with assets that are less collateralizable since monitoring the capital outlays of such firms is probably more difficult. For this reason, firms with less collateralizable assets may choose higher debt levels to limit their managers' consumption of perquisites.The estimated model incorporates two indicators for the collateral value attribute. They include the ratio of intangible assets to total assets (INTITA) and the ratio of inventory plus gross plant and equipment to total assets (IGPITA). The first indicator is negatively related to the collateral value attribute, while the second is positively related to collateral value.B. Non-Debt Tax ShieldsDeAngelo and Masulis present a model of optimal capital structure that incorporates the impact of corporate taxes, personal taxes, and non-debt-related corporate tax shields. They argue that tax deductions for depreciation and investment tax credits are substitutes for the tax benefits of debt financing. As a result, firms with large non-debt tax shields relative to their expected cash flow include less debt in their capital structures.Indicators of non-debt tax shields include the ratios of investment tax credits over total assets (ITCITA), depreciation over total assets (DITA), and a direct estimate of non-debt tax shields over total assets (NDTITA). The latter measure is calculated from observed federal income tax payments (T), operating income (OI), interest payments (i), and the corporate tax rate during our sample period (48%), using the following equation:NDT=OI-i-T/0.48which follows from the equalityT = 0.48(OI- i-NDT).These indicators measure the current tax deductions associated with capital equipment and, hence, only partially capture the non-debt tax shield variable suggested by DeAngelo and Masulis. First, this attribute excludes tax deductions that are not associated with capital equipment, such as research and development and selling expenses. (These variables, used as indicators of another attribute, are discussed later.) More important, our non-debt tax shield attribute represents tax deductions rather than tax deductions net of true economic depreciation and expenses, which is the economic attribute suggested by theory. Unfortunately, this preferable attribute would be very difficult to measure.C. GrowthAs we mentioned previously, equity-controlled firms have a tendency to invest suboptimally to expropriate wealth from the firm's bondholders. The cost associated with this agency relationship is likely to be higher for firms in growing industries, which have more flexibility in their choice of future investments. Expected future growth should thus be negatively related to long-term debt levels. Myers, however,noted that this agency problem is mitigated if the firm issues short-term rather than long-term debt. This suggests that short-term debt ratios might actually be positively related to growth rates if growing firms substitute short-term financing for long-term financing. Jensen and Meckling, Smith and Warner, and Green argued that the agency costs will be reduced if firms issue convertible debt. This suggests that convertible debt ratios may be positively related to growth opportunities.It should also be noted that growth opportunities are capital assets that add value to a firm but cannot be collateralized and do not generate current taxable income. For this reason, the arguments put forth in the previous subsections also suggest a negative relation between debt and growth opportunities.Indicators of growth include capital expenditures over total assets (CEITA) and the growth of total assets measured by the percentage change in total assets (GTA). Since firms generally engage in research and development to generate future investments, research and development over sales (RDIS) also serves as an indicator of the growth attribute.D. UniquenessTitman presents a model in which a firm's liquidation decision is causally linked to its bankruptcy status. As a result, the costs that firms can potentially impose on their customers, suppliers, and workers' by liquidating are relevant to their capital structure decisions. Customers, workers, and suppliers of firms that produce unique or specialized products probably suffer relatively high costs in the event that they liquidate. Their workers and suppliers probably have jobspecific skills and capital, and their customers may find it difficult to find alternative servicing for their relatively unique products. For these reasons, uniqueness is expected to be negatively related to debt ratios.Indiators of uniqueness include expenditures on research and development over sales (RDIS), selling expenses over sales (SEIS), and quit rates (QR), the percentage of the industry's total work force that voluntarily left their jobs in the sample years. It is postulated that RDIS measures uniqueness because firms that sell products with close substitutes ark likely to do less research and development since their innovationscan be more easily duplicated. In addition, successful research and development projects lead to new products that differ from those existing in the market. Firms with relatively unique products are expected to advertise more and, in general, spend more in promoting and selling their products. Hence, SEIS is expected to be positively related to uniqueness. However, it is expected that firms in industries with high quit rates are probably relatively less unique since firms that produce relatively unique products tend to employ workers with high levels of job-specific human capital who will thus find it costly to leave their jobs.It is apparent from two of the indicators of uniqueness, RDIS and SEIS, that this attribute may also be related to non-debt tax shields and collateral value. Research and development and some selling expenses (such as advertising) can be considered capital goods that are immediately expensed and cannot be used as collateral. Given that our estimation technique can only imperfectly control for these other attributes, the uniqueness attribute may be negatively related to the observed debt ratio because of its positive correlation with non-debt tax shields and its negative correlation with collateral value.E. Industry ClassificationTitman suggests that firms that make products requiring the availability of specialized servicing and spare parts will find liquidation especially costly. This indicates that firms manufacturing machines and equipment should be financed with relatively less debt. To measure this, we include a dummy variable equal to one for firms with SIC codes between 3400 and 4000 (firms producing machines and equipment) and zero otherwise as a separate attribute affecting the debt ratios.F. SizeA number of authors have suggested that leverage ratios may be related to firm size. Warner and Ang, Chua, and McConnell provide evidence that suggests that direct bankruptcy costs appear to constitute a larger proportion of a firm's value as that value decreases. It is also the case that relatively large firms tend to be more diversified and less prone to bankruptcy. These arguments suggest that large firms should be more highly leveraged.The cost of issuing debt and equity securities is also related to firm size. In particular, small firms pay much more than large firms to issue new equity (see Smith) and also somewhat more to issue long-term debt. This suggests that small firms may be more leveraged than large firms and may prefer to borrow short term (through bank loans) rather than issue long-term debt because of the lower fixed costs associated with this alternative.We use the natural logarithm of sales (LnS) and quit rates (QR) as indicators of size.5 The logarithmic transformation of sales reflects our view that a size effect, if it exists, affects mainly the very small firms. The inclusion of quit rates, as an indicator of size, reflects the phenomenon that large firms, which often offer wider career opportunities to their employees, have lower quit rates.G. VolatilityMany authors have also suggested that a firm's optimal debt level is a decreasing function of the volatility of earning. We were only able to include one indicator of volatility that cannot be directly affected by the firm's debt level. It is the standard deviation of the percentage change in operating income (SIGOI). Since it is the only indicator of volatility, we must assume that it measures this attribute without error. H. ProfitabilityMyers cites evidence from Donaldson and Brealey and Myers that suggests that firms prefer raising capital, first from retained earnings, second from debt, and third from issuing new equity. He suggests that this behavior may be due to the costs of issuing new equity. These can be the costs discussed in Myers and Majluf that arise because of asymmetric information, or they can be transaction costs. In either case, the past profitability of a firm, and hence the amount of earnings available to be retained, should be an important determinant of its current capital structure. We use the ratios of operating income over sales (OIIS) and operating income over total assets (OIITA) as indicators of profitability.Measures of Capital StructureSix measures of financial leverage are used in this study. They are long-term, short-term, and convertible debt divided by market and by book values of equity.'Although these variables could have been combined to extract a common "debt ratio" attribute, which could in turn be regressed against the independent attributes, there is good reason for not doing this. Some of the theories of capital structure have different implications for the different types of debt, and, for the reasons discussed below, the predicted coefficients in the structural model may differ according to whether debt ratios are measured in terms of book or market values. Moreover, measurement errors in the dependent variables are subsumed in the disturbance term and do not bias the regression coefficients.Data limitations force us to measure debt in terms of book values rather than market values. It would, perhaps, have been better if market value data were available for debt. However, Bowman demonstrated that the cross-sectional correlation between the book value and market value of debt is very large, so the misspecification due to using book value measures is probably fairly small. Furthermore, we have no reason to suspect that the cross-sectional differences between market values and book values of debt should be correlated with any of the determinants of capital structure suggested by theory, so no obvious bias will result because of this misspecification.There are, however, some other important sources of spurious correlation. The dependent variables used in this study can potentially be correlated with the explanatory variables even if debt levels are set randomly. Consider first the case where managers set their debt levels according to some randomly selected target ratio measured at book value.' This would not be irrational if capital structure were in fact irrelevant. If managers set debt levels in terms of book value rather than market value ratios, then differences in market values across firms that arise for reasons other than differences in their book values (such as different growth opportunities) will not necessarily affect the total amount of debt they issue. Since these differences do, of course, affect the market value of their equity, this will have the effect of causing firms with higher marketbook value ratios to have lower debt/market value ratios. Since firms with growth opportunities and relatively low amounts of collateralizable assets tend to have relatively high market value/book value ratios, a spurious relation might exist between debt market value and these variables, creating statisticallysignificant coefficient estimates even if the book value debt ratios are selected randomly.Similar spurious relations will be induced between debt ratios measured at book value and the explanatory variables if firms select debt levels in accordance with market value target ratios. If some firms use book value targets while others use market value targets, both dependent variables will be spuriously correlated with the independent variables. Fortunately, the book and market value debt ratios induce spurious correlation in opposite directions. Using dependent variables scaled by both book values and market values may then make it possible to separate the effects of capital structure suggested by theory, which predicts coefficient estimates of the same sign for both dependent variable groups, from these spurious effects.Source:Sheridan Titman; Roberto Wessels The Journal of Finance, V ol. 43, No. 1. (Mar., 1988), pp. 1-19.二、翻译文章译文:资本结构的选择的决定因素用以往用过的基本方法来评估回归方程,而此方程夹杂着难以窥测的代理性理论因素。

资本结构决定因素以中国企业为案例【外文翻译】XXX titled "XXX Structure: Evidence from XXX's n-making process in regards to their capital structure。

The article XXX: the "pecking order" theory and the "trade-off" theory.XXX external sources。

XXX。

This is due to the XXX seeks external XXX that a financial manager will first use internal capital。

then issue debt。

and only as a last resort。

XXX。

This is because the market may perceive the issuance of equity as a signal of poor XXX.2.2 The trade-off XXXIn contrast。

the XXX and potential financial distress costsare low。

XXX and financial distress costs are high.Overall。

XXX's n-making process in regards to their capital structure。

By examining the pecking order and trade-off theories。

the article sheds light on the complex nature of this XXX inform future research in this area.XXX。

中英文对照外文翻译(文档含英文原文和中文翻译)The effect of capital structure on profitability : an empirical analysis of listed firms in Ghana IntroductionThe capital structure decision is crucial for any business organization. The decision is important because of the need to maximize returns to various organizational constituencies, and also because of the impact such a decision has on a firm’s ability to deal with its competitive environment. The capital structure of a firm is actually a mix of different securities. In general, a firm can choose among many alternative capital structures. It can issue a large amount of debt or very little debt. It can arrange lease financing, use warrants, issue convertible bonds, sign forward contracts or trade bond swaps. It can issue dozens of distinct securities in countless combinations; however, it attempts to find the particular combination that maximizes its overall market value.A number of theories have been advanced in explaining the capital structure of firms. Despite the theoretical appeal of capital structure, researchers in financial management have not found the optimal capital structure. The best that academics and practitioners have been able to achieve are prescriptions that satisfy short-term goals. For example, the lack of a consensus about what would qualify as optimal capital structure has necessitated the need for this research. A better understanding of the issues at hand requires a look at the concept of capital structure and its effect on firm profitability. This paper examines the relationship between capital structure and profitability of companies listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange during the period 1998-2002. The effect of capital structure on the profitability of listed firms in Ghana is a scientific area that has not yet been explored in Ghanaian finance literature.The paper is organized as follows. The following section gives a review of the extant literature on the subject. The next section describes the data and justifies the choice of the variables used in the analysis. The model used in the analysis is then estimated. The subsequent section presents and discusses the results of the empirical analysis. Finally, the last section summarizes the findings of the research and also concludes the discussion.Literature on capital structureThe relationship between capital structure and firm value has been the subject of considerable debate. Throughout the literature, debate has centered on whether there is an optimal capital structure for an individual firm or whether the proportion of debt usage is irrelevant to the individual firm’s value. The capital structure of a firm concerns the mix of debt and equity the firm uses in its operation. Brealey and Myers (2003) contend that the choice of capital structure is fundamentally a marketing problem. They state that the firm can issue dozens of distinct securities in countless combinations, but it attempts to find the particular combination that maximizes market value. According to Weston and Brigham (1992), the optimal capital structure is the one that maximizes the market value of the firm’s outstanding shares.Fama and French (1998), analyzing the relationship among taxes, financing decisions, and the firm’s value, concluded that the debt does not concede tax b enefits. Besides, the high leverage degree generates agency problems among shareholders and creditors that predict negative relationships between leverage and profitability. Therefore, negative information relating debt and profitability obscures the tax benefit of the debt. Booth et al. (2001) developed a study attempting to relate the capital structure of several companies in countries with extremely different financial markets. They concluded thatthe variables that affect the choice of the capital structure of the companies are similar, in spite of the great differences presented by the financial markets. Besides, they concluded that profitability has an inverse relationship with debt level and size of the firm. Graham (2000) concluded in his work that big and profitable companies present a low debt rate. Mesquita and Lara (2003) found in their study that the relationship between rates of return and debt indicates a negative relationship for long-term financing. However, they found a positive relationship for short-term financing and equity.Hadlock and James (2002) concluded that companies prefer loan (debt) financing because they anticipate a higher return. Taub (1975) also found significant positive coefficients for four measures of profitability in a regression of these measures against debt ratio. Petersen and Rajan (1994) identified the same association, but for industries. Baker (1973), who worked with a simultaneous equations model, and Nerlove (1968) also found the same type of association for industries. Roden and Lewellen (1995) found a significant positive association between profitability and total debt as a percentage of the total buyout-financing package in their study on leveraged buyouts. Champion (1999) suggested that the use of leverage was one way to improve the performance of an organization.In summary, there is no universal theory of the debt-equity choice. Different views have been put forward regarding the financing choice. The present study investigates the effect of capital structure on profitability of listed firms on the GSE.MethodologyThis study sampled all firms that have been listed on the GSE over a five-year period (1998-2002). Twenty-two firms qualified to be included in the study sample. Variables used for the analysis include profitability and leverage ratios. Profitability is operationalized using a commonly used accounting-based measure: the ratio of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) to equity. The leverage ratios used include:. short-term debt to the total capital;. long-term debt to total capital;. total debt to total capital.Firm size and sales growth are also included as control variables.The panel character of the data allows for the use of panel data methodology. Panel data involves the pooling of observations on a cross-section of units over several time periods and provides results that are simply not detectable in pure cross-sections or pure time-series studies. A general model for panel data that allows the researcher to estimate panel data with great flexibility and formulate the differences in the behavior of thecross-section elements is adopted. The relationship between debt and profitability is thus estimated in the following regression models:ROE i,t =β0 +β1SDA i,t +β2SIZE i,t +β3SG i,t + ëi,t (1) ROE i,t=β0 +β1LDA i,t +β2SIZE i,t +β3SG i,t + ëi,t (2) ROE i,t=β0 +β1DA i,t +β2SIZE i,t +β3SG i,t + ëi,t (3)where:. ROE i,t is EBIT divided by equity for firm i in time t;. SDA i,t is short-term debt divided by the total capital for firm i in time t;. LDA i,t is long-term debt divided by the total capital for firm i in time t;. DA i,t is total debt divided by the total capital for firm i in time t;. SIZE i,t is the log of sales for firm i in time t;. SG i,t is sales growth for firm i in time t; and. ëi,t is the error term.Empirical resultsTable I provides a summary of the descriptive statistics of the dependent and independent variables for the sample of firms. This shows the average indicators of variables computed from the financial statements. The return rate measured by return on equity (ROE) reveals an average of 36.94 percent with median 28.4 percent. This picture suggests a good performance during the period under study. The ROE measures the contribution of net income per cedi (local currency) invested by the firms’ stockholders; a measure of the efficiency of the owners’ invested capital. The variable SDA measures the ratio of short-term debt to total capital. The average value of this variable is 0.4876 with median 0.4547. The value 0.4547 indicates that approximately 45 percent of total assets are represented by short-term debts, attesting to the fact that Ghanaian firms largely depend on short-term debt for financing their operations due to the difficulty in accessing long-term credit from financial institutions. Another reason is due to the under-developed nature of the Ghanaian long-term debt market. The ratio of total long-term debt to total assets (LDA) also stands on average at 0.0985. Total debt to total capital ratio(DA) presents a mean of 0.5861. This suggests that about 58 percent of total assets are financed by debt capital. The above position reveals that the companies are financially leveraged with a large percentage of total debt being short-term.Table I.Descriptive statisticsMean SD Minimum Median Maximum━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ROE 0.3694 0.5186 -1.0433 0.2836 3.8300SDA 0.4876 0.2296 0.0934 0.4547 1.1018LDA 0.0985 0.1803 0.0000 0.0186 0.7665DA 0.5861 0.2032 0.2054 0.5571 1.1018SIZE 18.2124 1.6495 14.1875 18.2361 22.0995SG 0.3288 0.3457 20.7500 0.2561 1.3597━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━Regression analysis is used to investigate the relationship between capital structure and profitability measured by ROE. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression results are presented in Table II. The results from the regression models (1), (2), and (3) denote that the independent variables explain the debt ratio determinations of the firms at 68.3, 39.7, and 86.4 percent, respectively. The F-statistics prove the validity of the estimated models. Also, the coefficients are statistically significant in level of confidence of 99 percent.The results in regression (1) reveal a significantly positive relationship between SDA and profitability. This suggests that short-term debt tends to be less expensive, and therefore increasing short-term debt with a relatively low interest rate will lead to an increase in profit levels. The results also show that profitability increases with the control variables (size and sales growth). Regression (2) shows a significantly negative association between LDA and profitability. This implies that an increase in the long-term debt position is associated with a decrease in profitability. This is explained by the fact that long-term debts are relatively more expensive, and therefore employing high proportions of them could lead to low profitability. The results support earlier findings by Miller (1977), Fama and French (1998), Graham (2000) and Booth et al. (2001). Firm size and sales growth are again positively related to profitability.The results from regression (3) indicate a significantly positive association between DA and profitability. The significantly positive regression coefficient for total debt implies that an increase in the debt position is associated with an increase in profitability: thus, the higher the debt, the higher the profitability. Again, this suggests that profitable firms depend more on debt as their main financing option. This supports the findings of Hadlock and James (2002), Petersen and Rajan (1994) and Roden and Lewellen (1995) that profitable firms use more debt. In the Ghanaian case, a high proportion (85 percent)of debt is represented by short-term debt. The results also show positive relationships between the control variables (firm size and sale growth) and profitability.Table II.Regression model results━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━Profitability (EBIT/equity)Ordinary least squares━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━Variable 1 2 3SIZE 0.0038 (0.0000) 0.0500 (0.0000) 0.0411 (0.0000)SG 0.1314 (0.0000) 0.1316 (0.0000) 0.1413 (0.0000)SDA 0.8025 (0.0000)LDA -0.3722(0.0000)DA -0.7609(0.0000)R²0.6825 0.3968 0.8639SE 0.4365 0.4961 0.4735Prob. (F) 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ConclusionsThe capital structure decision is crucial for any business organization. The decision is important because of the need to maximize returns to various organizational constituencies, and also because of the impact such a decision has on an organization’s ability to deal with its competitive environment. This present study evaluated the relationship between capital structure and profitability of listed firms on the GSE during a five-year period (1998-2002). The results revealed significantly positive relation between SDA and ROE, suggesting that profitable firms use more short-term debt to finance their operation. Short-term debt is an important component or source of financing for Ghanaian firms, representing 85 percent of total debt financing. However, the results showed a negative relationship between LDA and ROE. With regard to the relationship between total debt and profitability, the regression results showed a significantly positive association between DA and ROE. This suggests that profitable firms depend more on debt as their main financing option. In the Ghanaian case, a high proportion (85 percent) of the debt is represented in short-term debt.译文加纳上市公司资本结构对盈利能力的实证研究论文简介资本结构决策对于任何商业组织都是至关重要的。

![资本结构的决定因素研究:基于土耳其房屋租赁公司[文献翻译]](https://uimg.taocdn.com/a7683f91c1c708a1284a4451.webp)

lodging companies出处:International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 作者:Erdinc Karadeniz, Serkan Yilmaz Kandir, Mehmet Balcilar andYildirim Beyazit Onal原文Determinants of capital structure:evidence from Turkish lodging companiesBy Erdinc Karadeniz, Serkan Yilmaz Kandir, Mehmet Balcilar and Yildirim BeyazitOnalIntroductionCap ital structure refers to the composition of a firm’s liabilities and owners’ equity. Capital structure decisions are related to the magnitudes of liabilities and owners’equity. Capital structure decisions are one of the three financing decisions –investment, financing, and dividend decisions – finance managers have to make (Van Horne and Wachowicz, 1995).Capital structure of a firm determines the weighted average cost of capital (WACC).WACC is the minimum rate of return required on a firm’s investments an d used as the discount rate in determining the value of a firm. A firm can create value for its shareholders as long as earnings exceed the costs of investments (Damodaran, 2000).A number of theoretical and empirical studies investigated the optimal capital structure of a firm. These studies pointed out the importance of the relationships among capital structure, cost of capital, capital budgeting decisions, and firm value.Lodging companies are capital intensive, as they require huge capital at both investment and operating stages. Since assets of lodging companies mostly consist of fixed assets share of long-term debt and owners’ equity becomes rather high. Furthermore, because of the structure of the industry, lodging companies are highly sensitive to systematic risks. Therefore, lodging companies face high operating andfinancial risks (Andrew and Schmidgall, 1993). All these make it important to determine the composition of capital structure and the factors affecting leverage decisions and debt ratio.The trade-off and pecking order theoriesThe relationship between capital structure decisions and firm value has been extensively investigated in the past few decades. Over the years, alternative capital structure theories have been developed in order to determine the factors that affect capital structure decisions. Modigliani and Miller (1958) is a milestone among capital structure studies. In their first proposition, Modigliani and Miller (1958) state that market is fully efficient when there are no taxes. Thus, capital structure and financing decisions affect neither cost of capital nor market value of a firm. In their second proposition, they maintain that interest payments of debt decrease the tax base, thus cost of debt is less than the cost of equity. The tax advantage of debt motivates the optimal capital structure theory, which implies that firms may attain optimal capital structure and increase firm value by altering their capital structures. Bankruptcy and financial distress costs (Myers, 1977) and agency costs (Jensen and Meckling, 1976) constitute the basics of trade-off theory. Trade-off theory asserts that firms set a target debt to value ratio and gradually move towards it. According to this theory, any increase in the level of debt causes an increase in bankruptcy, financial distress and agency costs, and hence decreases firm value. Thus, an optimal capital structure may be reached by establishing equilibrium between advantages (tax advantages) and disadvantages (financial distress and bankruptcy costs) of debt. In order to establish this equilibrium firms should seek debt levels at which the costs of possible financial distress offset the tax advantages of additional debt.Data and methodologyWe investigate the determinants of capital structure decisions of lodging companies using a panel data on five companies traded in the ISE. Although there are eight lodging companies traded in the ISE, there of these companies are excluded from the study since these are traded only after 2000 and including would substantially reduce the number of observations. The sample period of the data set spans the period1994-2006. There are totally 65 observations and all data are expressed in local currency (Turkish lira). We specify a dynamic fixed effects panel data model to investigate the factors that affect the capital structure of lodging companies. Various estimation techniques, including the Arellano-Bond System GMM method, are used for the estimation. In the theoretical model specified to test the capital structure decisions of the lodging companies in Turkey the dependent variable is specified as the debt ratio. The debt ratio is defined as the book value of liabilities divided by the book value of total assets. This variable measures the share of liabilities in total assets of a company and is widely used in capital structure studies. Explanatory variables are specified as follows:. growth opportunities defined as the market value divided by the book value of the firm, often referred as market-to-book ratio;. share of fixed assets (tangibility) defined as the net fixed tangible assets divided by total assets;. effective tax rates defined as the corporate tax divided by taxable income;. non-debt tax shields defined as the depreciation divided by total assets;. firm size defined as the net sales adjusted by the inflation rate, where the inflation rate is computed as the annual percentage change in the wholesale price index;. profitability (return on assets-ROA) calculated by dividing net profit by total assets; . free cash flows computed by adding interest payments and depreciation to earnings before taxes;. net commercial trade position (inter-enterprise debt) defined as the difference between commercial receivables and liabilities divided by total assets.Empirical findingsIn this section, we present the various estimation results and discuss the implications of the empirical findings. The specification of the debt ratio equation introduces correlation between the errors and the lagged first-differenced endogenous variable. This correlation is handled using instrumental variables (IVs). Anderson and Hsiao (1982) proposed using lagged past differences or levels of endogenous variables as instruments (Anderson-Hsiao IV approach). These IVs are proposedwithin the framework of the GMM, since they may not be highly correlated with the first-differenced dependent variable. Alternatively, Arellano and Bond (1991) suggested that first differences of the endogenous variable be instrumented with lags of its own levels. This is known as the Arellano-Bond GMM approach. Blundell and Bond (1998) pointed out that lagged levels are often poor instruments for first differences. They proposed using all information on both endogenous and exogenous variables. This is known as the Arellano and Bond system (Arellano-Bond System GMM approach) method and provides more efficient and unbiased estimates in small Samples。

外文翻译Capital Structure and Firm Performance Material Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve SystemAuthor: Allen N. BergerAgency costs represent important problems in corporate governance in both financial and nonfinancial industries. The separation of ownership and control in a professionally managed firm may result in managers exerting insufficient work effort, indulging in perquisites, choosing inputs or outputs that suit their own preferences, or otherwise failing to maximize firm value. In effect, the agency costs of outside ownership equal the lost value from professional managers maximizing their own utility, rather than the value of the firm.Theory suggests that the choice of capital structure may help mitigate these agency costs. Under the agency costs hypothesis, high leverage or a low equity/asset ratio reduces the agency costs of outside equity and increases firm value by constraining or encouraging managers to act more in the interests of shareholders. Since the seminal paper by Jensen and Meckling (1976), a vast literature on such agency-theoretic explanations of capital structure has developed (see Harris and Raviv 1991 and Myers 2001 for reviews). Greater financial leverage may affect managers and reduce agency costs through the threat of liquidation, which causes personal losses to managers of salaries, reputation, perquisites, etc. (e.g., Grossman and Hart 1982, Williams 1987), and through pressure to generate cash flow to pay interest expenses (e.g., Jensen 1986). Higher leverage can mitigate conflicts between shareholders and managers concerning the choice of investment (e.g., Myers 1977), the amount of risk to undertake (e.g., Jensen and Meckling 1976, Williams 1987), the conditions under which the firm is liquidated (e.g., Harris and Raviv 1990), and dividend policy (e.g., Stulz 1990).A testable prediction of this class of models is that increasing the leverage ratio should result in lower agency costs of outside equity and improved firm performance, all else held equal. However, when leverage becomes relatively high, further increases generate significant agency costs of outside debt – including higher expected costs of bankruptcy or financial distress – arising from conflicts between bondholders and shareholders.1 Because it is difficult to distinguish empiricallybetween the two sources of agency costs, we follow the literature and allow the relationship between total agency costs and leverage to be non-monotonic.Despite the importance of this theory, there is at best mixed empirical evidence in the extant literature (see Harris and Raviv 1991, Titman 2000, and Myers 2001 for reviews). Tests of the agency costs hypothesis typically regress measures of firm performance on the equity capital ratio or other indicator of leverage plus some control variables. At least three problems appear in the prior studies that we address in our application.First, the measures of firm performance are usually ratios fashioned from financial statements or stock market prices, such as industry-adjusted operating margins or stock market returns. These measures do not net out the effects of differences in exogenous market factors that affect firm value, but are beyond management’s control and therefore cannot reflect agency costs. Thus, the tests may be confounded by factors that are unrelated to agency costs. As well, these studies generally do not set a separate benchmark for each firm’s performance that would be realized if agency costs were minimized.We address the measurement problem by using profit efficiency as our indicator of firm performance. The link between productive efficiency and agency costs was first suggested by Stigler (1976), and profit efficiency represents a refinement of the efficiency concept developed since that time.2 Profit efficiency evaluates how close a firm is to earning the profit that a best-practice firm would earn facing the same exogenous conditions. This has the benefit of controlling for factors outside the control of management that are not part of agency costs. In contrast, comparisons of standard financial ratios, stock market returns, and similar measures typically do not control for these exogenous factors. Even when the measures used in the literature are industry adjusted, they may not account for important differences across firms within an industry –such as local market conditions – as we are able to do with profit efficiency. In addition, the performance of a best-practice firm under the same exogenous conditions is a reasonable benchmark for how the firm would be expected to perform if agency costs were minimized.Second, the prior research generally does not take into account the possibility of reverse causation from performance to capital structure. If firm performance affects the choice of capital structure, then failure to take this reverse causality into account may result in simultaneous-equations bias. That is, regressions of firmperformance on a measure of leverage may confound the effects of capital structure on performance with the effects of performance on capital structure.We address this problem by allowing for reverse causality from performance to capital structure. We discuss below two hypotheses for why firm performance may affect the choice of capital structure, the efficiency-risk hypothesis and the franchise-value hypothesis. We construct a two-equation structural model and estimate it using two-stage least squares (2SLS). An equation specifying profit efficiency as a function of the firm’s equity capital ratio and other variables is use d to test the agency costs hypothesis, and an equation specifying the equity capital ratio as a function of the firm’s profit efficiency and other variables is used to test the net effects of the efficiency-risk and franchise-value hypotheses. Both equations are econometrically identified through exclusion restrictions that are consistent with the theories.Third, some, but not all of the prior studies did not take ownership structure into account. Under virtually any theory of agency costs, ownership structure is important, since it is the separation of ownership and control that creates agency costs (e.g., Barnea, Haugen, and Senbet 1985). Greater insider shares may reduce agency costs, although the effect may be reversed at very high levels of insider holdings (e.g., Morck, Shleifer, and Vishny 1988). As well, outside block ownership or institutional holdings tend to mitigate agency costs by creating a relatively efficient monitor of the managers (e.g., Shleifer and Vishny 1986). Exclusion of the ownership variables may bias the test results because the ownership variables may be correlated with the dependent variable in the agency cost equation (performance) and with the key exogenous variable (leverage) through the reverse causality hypotheses noted above.To address this third problem, we include ownership structure variables in the agency cost equation explaining profit efficiency. We include insider ownership, outside block holdings, and institutional holdings.Our application to data from the banking industry is advantageous because of the abundance of quality data available on firms in this industry. In particular, we have detailed financial data for a large number of firms producing comparable products with similar technologies, and information on market prices and other exogenous conditions in the local markets in which they operate. In addition, some studies in this literature find evidence of the link between the efficiency of firms and variables that are recognized to affect agency costs, including leverage andownership structure (see Berger and Mester 1997 for a review).Although banking is a regulated industry, banks are subject to the same type of agency costs and other influences on behavior as other industries. The banks in the sample are subject to essentially equal regulatory constraints, and we focus on differences across banks, not between banks and other firms. Most banks are well above the regulatory capital minimums, and our results are based primarily on differences at the margin, rather than the effects of regulation. Our test of the agency costs hypothesis using data from one industry may be built upon to test a number of corporate finance hypotheses using information on virtually any industry.We test the agency costs hypothesis of corporate finance, under which high leverage reduces the agency costs of outside equity and increases firm value by constraining or encouraging managers to act more in the interests of shareholders. Our use of profit efficiency as an indicator of firm performance to measure agency costs, our specification of a two-equation structural model that takes into account reverse causality from firm performance to capital structure, and our inclusion of measures of ownership structure address problems in the extant empirical literature that may help explain why prior empirical results have been mixed. Our application to the banking industry is advantageous because of the detailed data available on a large number of comparable firms and the exogenous conditions in their local markets. Although banks are regulated, we focus on differences across banks that are driven by corporate governance issues, rather than any differences in-regulation, given that all banks are subject to essentially the same regulatory framework and most banks are well above the regulatory capital minimums.Our findings are consistent with the agency costs hypothesis – higher leverage or a lower equity capital ratio is associated with higher profit efficiency, all else equal. The effect is economically significant as well as statistically significant. An increase in leverage as represented by a 1 percentage point decrease in the equity capital ratio yields a predicted increase in profit efficiency of about 6 percentage points, or a gain of about 10% in actual profits at the sample mean. This result is robust to a number of specification changes, including different measures of performance (standard profit efficiency, alternative profit efficiency, and return on equity), different econometric techniques (two-stage least squares and OLS), different efficiency measurement methods (distribution-free and fixed-effects), different samples (the “ownership sample” of banks with detailed ownership data and the “full sample” of banks), and the different sample periods (1990s and 1980s).However, the data are not consistent with the prediction that the relationship between performance and leverage may be reversed when leverage is very high due to the agency costs of outside debt.We also find that profit efficiency is responsive to the ownership structure of the firm, consistent with agency theory and our argument that profit efficiency embeds agency costs. The data suggest that large institutional holders have favorable monitoring effects that reduce agency costs, although large individual investors do not. As well, the data are consistent with a non-monotonic relationship between performance and insider ownership, similar to findings in the literature.With respect to the reverse causality from efficiency to capital structure, we offer two competing hypotheses with opposite predictions, and we interpret our tests as determining which hypothesis empirically dominates the other. Under the efficiency-risk hypothesis, the expected high earnings from greater profit efficiency substitute for equity capital in protecting the firm from the expected costs of bankruptcy or financial distress, whereas under the franchise-value hypothesis, firms try to protect the expected income stream from high profit efficiency by holding additional equity capital. Neither hypothesis dominates the other for the ownership sample, but the substitution effect of the efficiency-risk hypothesis dominates for the full sample, suggesting a difference in behavior for the small banks that comprise most of the full sample.The approach developed in this paper can be built upon to test the agency costs hypothesis or other corporate finance hypotheses using data from virtually any industry. Future research could extend the analysis to cover other dimensions of capital structure. Agency theory suggests complex relationships between agency costs and different types of securities. We have analyzed only one dimension of capital structure, the equity capital ratio. Future research could consider other dimensions, such as the use of subordinated notes and debentures, or other individual debt or equity instruments.译文资本结构与企业绩效资料来源: 联邦储备系统理事会作者:Allen N. Berger 在财务和非财务行业,代理成本在公司治理中都是重要的问题。

资本结构层次因素甲,乙爱德华光加代?,赫伯特木村一Universidade圣保罗,圣保罗,巴西bUniversidade Presbiteriana麦肯齐,圣保罗,巴西文章资讯摘要:文章历史:我们分析了时间,固件,行业和国家一级的资本结构决定因素的影响。

收到2019年2月3日第一,我们使用阶层线性模式,以评估这些水平的相对重要性。

接受2019年8月16日我们发现,时间和企业一级公司的杠杆解释78%。

第二,我们包括随机拦截可在线二○一○年八月二十日和随机系数以分析公司的直接和间接的影响力/行业/国家characteristicsonfirmleverage.Wedocumentseveralimportantindirectinfluences ofvariablesatindus - JEL分类:尝试和国家层面的杠杆公司决定因素,以及在一些结构上的差异F30金融行为与发达国家和新兴国家的公司。

G32 2019埃尔塞维尔B.诉保留所有权利。

关键词:资本结构层次分析企业层面的决定因素行业水平的决定因素国家一级的决定因素1。

导言等,2019;。

曼西和里布,2019年;。

德赛等,2019)的比较与跨国公司的国内企业融资政策这些研究对资本结构的优势主要basedontheargumentthatglobalfactorsmightinfluencefinancial重点是分析某些公司特征- 例如,利润杠杆。

如果,一方面,它很容易找到研究,分析能力,有形性,大小等- 作为杠杆的决定因素。

在阿迪,公司/作为国家的资本结构影响因素的特点,tion,资本结构可能各不相同的时间(例如,Korajczyk和ontheotherhand,theliteratureoftenneglectstheroleofindustry。

利维,2019年),尽管常常相对稳定云集帽虽然大多数研究包括资本结构虚拟需求面实证结构(莱蒙等。

中文3400字原文:The interaction of corporate dividend policy and capital structure decisions under differential tax regimes1、The interaction of capital structure and dividend policyFirm values are normalized with respect to the firm with zero debt and zero dividend payout. The panels in the figure indicate that the combined net impact of corporate dividend and capital structure policies on firm value is directly affected by the pertinent tax rates at the time.We next discuss the implications of the model for dividend and capital structure policies under several historical tax regimes. Three representative tax regimes (1979–1981, 1988–1990, 1993–2002) were chosen for analysis out of the ten that were in existence at some time during the three decades since 1979. The three representative tax regimes exhibit distinctly different set of tax rates both in terms of absolute values and relative to each other. For this reason, these three contrasting regimes provide a suitable setting to test the value implications of our model. If our model provides a reasonable representation of firms’ capital structure and dividend policy decisions, the three contrasting tax regimes would be the ideal environment to observe the fit between the model’s predictions and the empirical o bservations.2、Years 1979–1981The application of the model using the tax rates from the period 1979–1981 reveals a subtle effect. The table and the figure depict normalized firm value, VD,Π/V0,0, as a function of the leverage D and the dividend payout π. The gain from leverage is positive only when the firm is at a relatively high payout ratio (above approximately 40%), with the maximum gain occurring at full (100%) payout. Interestingly, at a dividend payout level lower than 40%, increasing leverage lowers firm value.The reversal of the leverage effect at lower payout ratios is driven by the relative levels of tax rates. During the years 1979–1981, the top marginal tax rate for personalincome was very high in comparison to the tax rate for corporate income (70% and 46% respectively). In a tax rate environment such as this, high taxes paid by the bondholders for their interest income proceeds exceed the benefit from the tax deductibility of interest payments at the firm level. Since debt financing can be assumed to have zero NPV, this additional burden is borne by the shareholders. At high levels of dividend payout on the other hand, the taxation of the dividend income makes dividend payout even more disadvantageous compared to paying interest. In other words, now it would be more beneficial for the firm to borrow and pay interest rather than dividends. The benefit reaped from the tax deductibility of interest payments tilts the balance in favor of debt financing, and makes leverage more attractive.Another noteworthy observation about the 1979–1981 tax rate environment is the steep loss in firm value at very low debt levels in response to increasing dividend payout. According to our model, it was possible for an all-equity firm to experience losses in value up to 58%. The firm could mitigate this loss by maintaining a higher debt level.The tax regime that made the interesting features discussed above possible is not a short-term anomaly confined to the years 1979–1981. Indeed, the entire period between the Great Depression and the late 1970s was characterized by a similar tax rate environment. Our model indicates that optimal policies to maximize firm value under such tax regimes required zero debt and zero dividend payout. This prescription interestingly comports with the observed leverage policies of the time, when numerous prominent companies such as IBM and Coca Cola had little, if any, debt before the 1980s. However, if a firm would need to maintain high dividend payout levels, it would be better off by carrying a relatively high debt level at the same time. Traditional electric utility companies are examples that appear to fit this mold.3、Years 1988–1990 (and 1991–1992)The situation during the years 1988–1990 is unique because during that time the top marginal tax rates on ordinary income (thus on dividend and interest income) were nominally the same as the tax rate on capital gains at 28%. In the following 2 years(1991–1992), the two tax rates remained very close (at 31.0% and 28.9% respectively). The result of the convergence in tax rates is visible in Fig. 2 for the1988–1990 and 1991–1992 panels. There is little if any moderating influence of the dividend payout on the leverage-firm value relation. The maximum theoretical gain from leverage is close to 50% regardless of the level of dividend payout. As discussed and anticipated on the comparative statics for our model, the influence of the dividend payout ratio vanishes due to the near-zero tax rate differential (τpd−τpg) during the years 1988–1992.4、Years 1993–2002In contrast to the reversal effect observed under the tax regime during 1979–1981, and similar to the situation during 1988–1992, the gain from leverage is always positive under the 1993–2002 tax regimes. The details of the gain from leverage relation and the effect of the dividend payout for the years 1993–1994 and the year 2002 are available. As a departure from the previous tax regimes discussed above, throughout this decade-long time interval, the gain from leverage is significantly more pronounced for high payout firms. Although at low or zero debt levels increased dividend payout reduces the firm value, the negative impact of the dividend payout weakens as the debt level increases.In contrast to the maximum potential gain from leverage during 1988–1992 that reached up to 50%, the tax rate changes throughout the 1990s significantly reduced the maximum potential gain. the maximum potential gain was near 30% in 1993, and by 1998, approximately 20%,remaining at that level through 2002.5、Summary and empirical implicationsThe nature of the combined impact of financial leverage and dividend policy on firm value over the years 1979–2002 is found to be wide ranging as a direct result of the tax rate changes. We discussed above three distinct tax regime environments in detail. In the first interval 1979–1981, low leverage and low dividend payout leads to higher firm value. However, given a high dividend payout, the firm is better off by carrying a high debt level. That suggests a simultaneous increase or decrease in leverage and payout for firms. It is less likely to find firms with low leverage and highpayout (which results in the minimum possible firm value). The empirical implication of the model for the 1979–1981 time interval is a positive association between leverage and payout.The same logic applies throughout the years following the 1979–1981 time interval up to 1987 and again after 1992. During the years 1979–1987, the tax rate were such that at low debt levels, firm value declined with increasing dividend payout ratios. Similarly, from 1993 until 2002, firms would suffer losses in value if they chose to increase dividend payout while maintaining low debt levels. In contrast, during the 1988–1992 time interval, there was no penalty for having a high dividend payout for a firm with a low debt level. Dividend payout was truly irrelevant during that time and would not be expected to systematically vary between firms that carry various levels of debt.The breakdown in the interaction of dividend payout and capital structure during the 1988–1992 time period as implied by our model provides an opportunity to test the model empirically. If our model is a reasonable representation of the dividend payout-capital structure interaction under varying tax rate environments, we would expect a positive association between dividend payout and debt levels during the years 1979–1987 and 1993–2002 During the years 1988–1992, the association between dividend payout and leverage is expected to be weaker. We conduct several empirical tests in Section 5 to examine the validity of these predictions.It is worth noting that, to the extent firms have shifted their distributions to their shareholders from dividends to stock repurchases over time, our empirical analysis, which only uses dividend payout data, will not be able to pick up this trend. Indeed, during the three decades under study there was a shift in firms’ attitudes toward share repurchases vis-à-vis dividend payout. We do not pursue stock repurchases empirically in this study due to data limitations. However, note that the model derived in this paper is implicitly capturing the valuation effect of repurchases via the capital gains term .Variable pay is an expanding field within compensation driven by the emerging trends of pay for performance and competitive advantage. Funding these new programs and developing the processes supporting long-term effectiveness iscritical.In this paper we develop a valuation model that ties together capital structure and dividend payout polices while incorporating differential tax rates on dividend distributions and capital gains. As such it is an extension of the original Miller and Modigliani (1961) dividend policy model and of the Miller (1977) model. We numerically and graphically demonstrate the implications of this new model under ten different tax regimes in effect since 1979 and derive the implications of the model for firm value as a function of debt ratio and dividend payout ratio.Our analysis indicates a wide range of firm values depending on the particular set of tax rates applicable at the time. In the first interval, 1979–1981, when the tax regime featured a high rate on dividend income in comparison to the rates on corporate income and personal capital gains, increasing financial leverage would lead to losses in firm value, if the dividend payout was relatively small. At dividend payout ratios below 40%, the loss in firm value in response to increased debt ratio could potentially reach 23%. During the same time period, if the firm maintained a dividend payout ratio in excess of 40%, the firm value could almost double, if an all equity firm decided to take on debt. During the 1988–1990 time period, when the tax rates on dividend income and capital gains were both 28%, an all-equity firm (without regard to its dividend payout level) could increase in value by as much as50% as it took on more debt. Under the tax regimes prevailing after 1998, the maximum potential gain for a non-dividend paying all-equity firm was roughly 20%, whereas a firm with a high dividend payout could be worth 50% more if it were to boost its debt financing.Using the analysis of the valuation model under a diverse set of tax regimes, we develop several predictions for empirical testing. The results of the empirical tests are strongly supportive of the basic predictions of our analysis in a static setting. The interaction between dividend policy and financial leverage decisions is significantly influenced by the prevailing tax rates. The more dynamic predictions of the model remain for subsequent examination.By design, our tax-based model abstracts from the well-known and important contributions of previous studies on bankruptcy/financial distress costs, agencyconsiderations, and signaling theories. However, the insights gained from our extended tax-based model could contribute in a significant way to the understanding of corporate financial policy in both research and policy dimensions. It is a well established notion within the trade-off theory of corporate capital structure that a range of debt levels exists, in which debt financing has a positive impact on firm value. Over this range, our model has the potential to provide a valuable insight into the effect of dividend policy on capital structure.In the near future, another major change in the U.S. tax environment is possible, especially if the JGTRRA is allowed to expire by the Congress. The ability of the model in this paper to easily incorporate the new levels of marginal tax rates on four types of income makes it a useful tool for corporate decision makers in analyzing dividend and debt decisions. For purposes of research, the model can be used to gain insights into the evolution of dividend policy over the past three decades.Source: Ufuk Ince and James E. Owers. 2003 “The interaction of corporate dividend policy and capital structure decisions under differential tax regimes”. Journal of Economics and Finance, August, pp. 29-32.译文:在分税制度股利政策与资本结构下的决策1、互动的资本结构和股利政策公司价值方面进行归一零债务和零股利支出。

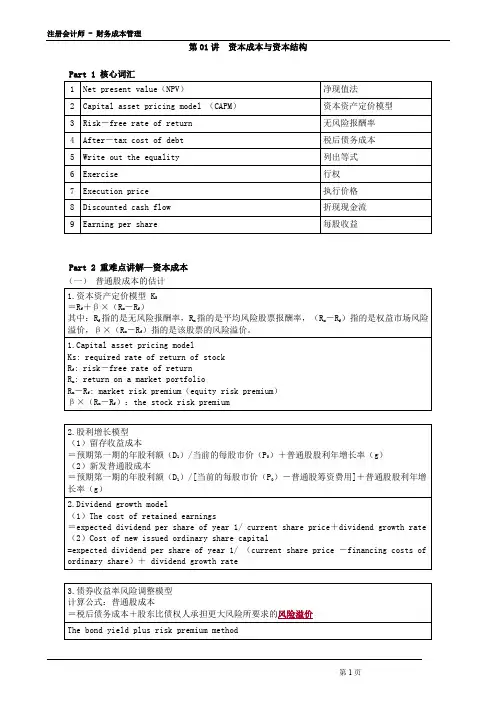

第01讲资本成本与资本结构Part 1 核心词汇Part 2 重难点讲解—资本成本(一)普通股成本的估计(二)优先股成本的估计(三)债务成本的估计特殊债券的成本估计(四)加权平均资本成本(WACC)【例题·2017年考题】甲公司为扩大产能,拟平价发行分离型附认股权证债券进行筹资,方案如下:债券每份面值1000元,期限5年,票面利率5%。

每年付息一次。

同时附送20份认股权证。

认股权证在债券发行3年后到期,到期时每份认股权证可按11元的价格购买1股甲公司普通股股票。

甲公司目前有发行在外的普通债券,5年后到期,每份面值1000元,票面利率6%,每年付息一次,每份市价1020元(刚刚支付过最近一期利息)公司目前处于生产的稳定增长期,可持续增长率5%。

普通股每股市价10元。

公司企业所得税率25%。

要求:(1)计算公司普通债券的税前资本成本。

(2)计算分离型附认股权证债券的税前资本成本。

(3)判断筹资方案是否合理,并说明理由,如果不合理,给出调整建议。

『正确答案』(1)令税前资本成本为iAssume Pre-tax cost of capital is i1020=1000×6%×(P/A,i,5)+1000×(P/F,i,5)当i=4%时,等式右边=1000×6%×4.4518+1000×0.8219=1089When i equals 4%, the right side of the equation=1000×6%×4.4518+1000×0.8219=1089 continuing当i=6%时, 等式右边=1000×6%×4.2124+1000×0.7473=1000When i equals 6%, the right side of the equation =1000×6%×4.2124+1000×0.7473=1000 列出等式:Write out the equality :(i-4%)/(6%-4%)=(1020-1089)/(1000-1089)i=4%+[(1020-1089)/(1000-1089)]×(6%-4%)=5.55%(2)第3年末行权支出=11×20=220(元)Exercise expenditure at the end of the third year=11×20=220(yuan )取得股票的市价=10×(F/P,5%,3)×20=231.525(元)The market price of the acquired stock=10×(F/P,5%,3)×20=231.525(yuan )行权现金净流入=231.5325-220=11.525(元)Net cash inflow when option are exercised= 231.5325-220=11.525(yuan )令税前资本成本为k,Assume Pre-tax cost of capital is K1000=1000×5%×(P/A,K,5)+11.525×(P/F,K,3)+1000×(P/F,K,5)K=5%时,等式右边=1000×5%×4.3295+11.525×0.8638+1000×0.7835=1009.93(元)When K equals 5%, the right side of the equation =……K=6%时,等式右边=1000×5%×4.2124+11.525×0.8396+1000×0.7473=967.60(元)When K equals 6%, the right side of the equation =……(K-5%)/(6%-5%)=(1000-1009.93)/(967.60-1009.93)K=5%+[(1000-1009.93)/(967.60-1009.93)]×(6%-5%)=5.23%(3)该筹资方案不合理,原因是附认股权证债券的税前资本成本低于普通债券的税前资本成本。