精读4Unit2 SpringSowing配套课件

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:6.72 MB

- 文档页数:43

课程名称:大学英语精读授课班级:大二英语专业课时安排:2课时教学目标:1. 理解课文内容,掌握课文中的重点词汇和短语。

2. 提高学生的阅读理解能力,培养学生独立思考、批判性思维。

3. 培养学生运用英语进行口头和书面表达的能力。

教学内容:1. 课文内容:Spring Sowing2. 重点词汇和短语:spring sowing, germinate, dormancy, fertilize, germination, etc.3. 语言点:过去式、过去进行时、条件句等。

教学步骤:第一课时一、导入1. 教师简要介绍课文背景,激发学生的学习兴趣。

2. 学生自由讨论课文标题,预测课文内容。

二、阅读课文1. 学生自主阅读课文,了解课文大意。

2. 教师引导学生找出课文中的生词和短语,并进行讲解。

3. 学生再次阅读课文,加深对课文内容的理解。

三、课堂讨论1. 教师提出问题,引导学生进行小组讨论。

2. 学生分享自己的观点,教师进行点评和总结。

四、巩固练习1. 学生完成课后练习题,巩固所学知识。

2. 教师针对练习题进行讲解,帮助学生解决疑惑。

第二课时一、复习导入1. 教师提问上节课的内容,检查学生对课文的理解程度。

2. 学生分享自己的学习心得。

二、深入阅读1. 学生再次阅读课文,重点关注语言点。

2. 教师讲解语言点,并举例说明。

三、课堂讨论1. 教师提出与课文相关的问题,引导学生进行深入讨论。

2. 学生分享自己的观点,教师进行点评和总结。

四、拓展练习1. 学生完成拓展练习题,提高自己的英语水平。

2. 教师针对练习题进行讲解,帮助学生提高阅读理解能力。

五、总结1. 教师对本节课的内容进行总结,强调重点。

2. 学生回顾本节课所学内容,巩固所学知识。

教学评价:1. 课堂参与度:观察学生在课堂上的发言和讨论情况。

2. 课后作业完成情况:检查学生的课后练习题完成情况。

3. 期末考试成绩:评估学生对本节课内容的掌握程度。

教学反思:1. 教师在讲解过程中,注重启发学生的思维,提高学生的英语能力。

大学英语精读4 unit2课件1. Introduction本课件是针对大学英语精读4课程中的Unit 2而编写的教学材料。

本单元的主要内容是关于国际关系和全球化的讨论。

通过本课程,学生将了解到有关国际关系的重要概念,并学会阅读并分析相关的英语文章。

2. Learning Objectives本单元的学习目标包括:•了解全球化和国际关系的定义和背景;•掌握本单元涉及的核心词汇和表达;•学会阅读并分析相关的英语文章;•提高关于国际关系的英语写作能力。

3. Unit Outline本单元的内容主要分为以下几个部分:3.1 全球化的定义和背景在这一部分,我们将探讨全球化的概念以及对国际关系产生的影响。

学生将了解到全球化的背景和原因,并通过案例分析来深入了解全球化对经济、文化和社会的影响。

3.2 国际关系中的重要概念这一部分将介绍国际关系中的一些重要概念,如国家主权、国际法、联合国等。

学生将学习这些概念的定义和相关的背景知识,并了解它们在实际的国际事务中的应用。

3.3 国际关系中的核心词汇和表达在这一部分,我们将学习与国际关系相关的核心词汇和常用表达。

这些词汇和表达将帮助学生更好地理解相关的文章和进行书面和口头表达。

3.4 阅读和分析相关的英语文章本单元还将包括阅读和分析相关的英语文章的训练。

学生将通过阅读和讨论来进一步理解国际关系的重要议题,并学会从英语文章中提取关键信息。

3.5 提高写作能力在这一部分,我们将进行有关国际关系的英语写作训练。

学生将学习如何撰写关于国际关系的议论文,并提高写作技巧和思维能力。

4. Assessment本单元的评估方式主要包括以下几个方面:•课堂参与和讨论:学生在课堂上积极参与讨论和提问,展示对国际关系的理解和分析能力。

•阅读报告:学生需要阅读指定的英语文章,并撰写阅读报告,分析其内容和观点。

•写作作业:学生需要完成有关国际关系的写作作业,包括议论文和摘要等。

5. Resources为了辅助学习,以下是一些可以参考的资源:•教科书:《大学英语精读4》•课件资料:本课件提供的教学资料和范例•英语词典:如牛津高阶英汉双解词典等,帮助理解核心词汇和表达•网络资源:如相关的学术文章、新闻报道和学术论坛等,帮助扩展阅读和研究的范围6. Conclusion通过本单元的学习,学生将对国际关系和全球化有更深入的理解,并提高相关的阅读和写作能力。

Spring SowingIt was still dark when Martin Delaney and his wife Mary got up. Martin stood in his shirt by the window, rubbing his eyes and yawning, while Mary raked out the live coals that had lain hidden in the ashes on the hearth all night. Outside, cocks were crowing and a white streak was rising form the ground, as it were, and beginning to scatter the darkness. It was a February morning, dry, cold and starry.The couple sat down to their breakfast of tea, bread and butter, in silence. They had only been married the previous autumn and it was hateful leaving a warm bed at such and early hour. Martin, with his brown hair and eyes, his freckled face and his little fair moustache, looked too young to be married, and his wife looked hardly more than a girl, red-cheeked and blue-eyed, her black hair piled at the rear of her head with a large comb gleaming in the middle of the pile, Spanish fashion. They were both dressed in rough homespuns, and both wore the loose white shirt that Inverara peasants use for work in the fields.They ate in silence, sleepy and yet on fire with excitement, for it was the first day of their first spring sowing as man and wife. And each felt the glamour of that day on which they were to open up the earth together and plant seeds in it. But somehow the imminence of an event that had been long expected loved, feared and prepared for made them dejected. Mary,with her shrewd woman's mind, thought of as many things as there are in life as a woman would in the first joy and anxiety of her mating. But Martin's mind was fixed on one thought. Would he be able to prove himself a man worthy of being the head of a family by dong his spring sowing well? In the barn after breakfast, when they were getting the potato seeds and the line for measuring the ground and the spade, Martin fell over a basket in the half-darkness of the barn, he swore and said that a man would be better off dead than.. But before he could finish whatever he was going to say, Mary had her arms around his waist and her face to his. "Martin," she said, "let us not begin this day cross with one another." And there was a tremor in her voice. And somehow, as they embraced, all their irritation and sleepiness left them. And they stood there embracing until at last Martin pushed her from him with pretended roughness and said: "Come, come, girl, it will be sunset before we begin at this rate."Still, as they walked silently in their rawhide shoes through the little hamlet, there was not a soul about. Lights were glimmering in the windows of a few cabins. The sky had a big grey crack in it in the east, as if it were going to burst in order to give birth to the sun. Birds were singing somewhere at a distance. Martin and Mary rested their baskets of seeds on a fence outside the village and Martin whispered to Mary proudly: "We are first, Mary." And they both looked back at the little cluster of cabins that was the centre of their world, with throbbing hearts. For the joyof spring had now taken complete hold of them.They reached the little field where they were to sow. It was a little triangular patch of ground under an ivy-covered limestone hill. The little field had been manured with seaweed some weeks before, and the weeds had rotted and whitened on the grass. And there was a big red heap of fresh seaweed lying in a corner by the fence to be spread under the seeds as they were laid. Martin, in spite of the cold, threw off everything above his waist except his striped woolen shirt. Then he spat on his hands, seized his spade and cried: "Now you are going to see what kind of a man you have, Mary.""There, now," said Mary, tying a little shawl closer under her chin. "Aren't we boastful this early hour of the morning? Maybe I'll wait till sunset to see what kind of a man I have got."The work began. Martin measured the ground by the southern fence for the first ridge, a strip of ground four feet wide, and he placed the line along the edge and pegged it at each end. Then he spread fresh seaweed over the strip. Mary filled her apron with seeds and began to lay them in rows. When she was a little distance down the ridge, Martin advanced with his spade to the head, eager to commence."Now in the name of God," he cried, spitting on his palms, "let us raise the first sod!""Oh, Martin, wait till I'm with you !" cried Mary, dropping her seeds onthe ridge and running up to him .Her fingers outside her woolen mittens were numb with the cold, and she couldn't wipe them in her apron. Her cheeks seemed to be on fire. She put an arm round Martin's waist and stood looking at the green sod his spade was going to cut, with the excitement of a little child."Now for God's sake, girl, keep back!" said Martin gruffly. "Suppose anybody saw us like this in the field of our spring sowing, what would they take us for but a pair of useless, soft, empty-headed people that would be sure to die of hunger? Huh!" He spoke very rapidly, and his eyes were fixed on the ground before hm. His eyes had a wild, eager light in them as if some primeval impulse were burning within his brain and driving out every other desire but that of asserting his manhood and of subjugating the earth."Oh, what do we care who is looking?" said Mary; but she drew back at the same time and gazed distantly at the ground. Then Martin cut the sod, and pressing the spade deep into the earth with his foot, he turned up the first sod with a crunching sound as the grass roots were dragged out of the earth. Mary sighed and walked back hurriedly to her seeds with furrowed brows. She picked up her seeds and began to spread them rapidly to drive out the sudden terror that had seized her at that moment when she saw the fierce, hard look in her husband's eyes that were unconscious of her presence. She became suddenly afraid of that pitiless, cruel earth, thepeasant's slave master that would keep her chained to hard work and poverty all her life until she would sink again into its bosom. Her short-lived love was gone. Henceforth she was only her husband's helper to till the earth. And Martin, absolutely without thought, worked furiously, covering the ridge with block earth, his sharp spade gleaming white as he whirled it sideways to beat the sods.Then, as the sun rose, the little valley beneath the ivy-covered hills became dotted with white shirts, and everywhere men worked madly, without speaking, and women spread seeds. There was no heat in the light of the sun, and there was a sharpness in the still thin air that made the men jump on their spade halts ferociously and beat the sods as if they were living enemies. Birds hopped silently before the spades, with their heads cocked sideways, watching for worms. Made brave by hunger, they often dashed under the spades to secure their food.Then, when the sun reached a certain point, all the women went back to the village to get dinner for their men, and the men worked on without stopping. Then the women returned, almost running, each carrying a tin can with a flannel tied around it and a little bundle tied with a white cloth, Martin threw down his spade when Mary arrived back in the field. Smiling at one another they sat under the hill for their meal .It was the same as their breakfast, tea and bread and butter."Ah," said Martin, when he had taken a long draught of tea form his mug,"is there anything in this world as fine as eating dinner out in the open like this after doing a good morning's work? There, I have done two ridges and a half. That's more than any man in the village could do. Ha!" And he looked at his wife proudly."Yes, isn't it lovely," said Mary, looking at the back ridges wistfully. She was just munching her bread and butter .The hurried trip to the village and the trouble of getting the tea ready had robbed her of her appetite. She had to keep blowing at the turf fire with the rim of her skirt, and the smoke nearly blinded her. But now, sitting on that grassy knoll, with the valley all round glistening with fresh seaweed and a light smoke rising from the freshly turned earth, a strange joy swept over her. It overpowered that other felling of dread that had been with her during the morning. Martin ate heartily, reveling in his great thirst and his great hunger, with every pore of his body open to the pure air. And he looked around at his neighbors' fields boastfully, comparing them with his own. Then he looked at his wife's little round black head and felt very proud of having her as his own. He leaned back on his elbow and took her hand in his. Shyly and in silence, not knowing what to say and ashamed of their gentle feelings, they finished eating and still sat hand in hand looking away into the distance. Everywhere the sowers were resting on little knolls, men, women and children sitting in silence. And the great calm of nature in spring filled the atmosphere around them. Everything seemedto sit still and wait until midday had passed. Only the gleaming sun chased westwards at a mighty pace, in and out through white clouds.Then in a distant field an old man got up, took his spade and began to clean the earth from it with a piece of stone. The rasping noise carried a long way in the silence. That was the signal for a general rising all along the little valley. Young men stretched themselves and yawned. They walked slowly back to their ridges.Martin's back and his wrists were getting sore, and Mary felt that if she stooped again over her seeds her neck would break, but neither said anything and soon they had forgotten their tiredness in the mechanical movement of their bodies. The strong smell of the upturned earth acted like a drug on their nerves.In the afternoon, when the sun was strongest, the old men of the village came out to look at their people sowing. Martin's grandfather, almost bent double over his thick stick stopped in the land outside the field and groaning loudly, he leaned over the fence.“God bless the work, "he called wheezily."And you, grandfather," replied the couple together, but they did not stop working.'Ha!" muttered the old man to himself. "He sows well and that woman is good too. They are beginning well."It was fifty years since he had begun with his Mary, full of hope and pride,and themerciless soil had hugged them to its bosom ever since, each spring without rest. Today, the old man, with his huge red nose and the spotted handkerchief tied around his skull under his black soft felt hat, watched his grandson work and gave him advice."Don't cut your sods so long," he would wheeze, "you are putting too much soil on yourridge."''Ah woman! Don't plant a seed so near the edge. The stalk will come out sideways."And they paid no heed to him."Ah," grumbled the old man," in my young days, when men worked from morning till night without tasting food, better work was done. But of course it can't be expected to be the same now. The breed is getting weaker. So it is."Then he began to cough in his chest and hobbled away to another field where his sonMichael was working.By sundown Martin had five ridges finished. He threw down his spade and stretched himself. All his bones ached and he wanted to lie down and rest. "It's time to be going home, Mary," he said.Mary straightened herself, but she was too tired to reply. She looked atMartin wearily and it seemed to her that it was a great many years since they had set out that morning. Then she thought of the journey home and the trouble of feeding the pigs, putting the fowls into their coops and getting the supper ready, and a momentary flash of rebellion against the slavery of being a peasant's wife crossed her mind. It passed in a moment. Martin was saying, as he dressed himself:"Ha! It has been a good day's work. Five ridges done, and each one of them as straight as a steel rod. By God Mary, it's no boasting to say that you might well be proud of being the wife of Martin Delaney. And that's not saying the whole of it ,my girl. You did your share better than any woman in Inverara could do it this blessed day."They stood for a few moments in silence, looking at the work they had done. All her dissatisfaction and weariness vanished form Mary's mind with the delicious feeling of comfort that overcame her at having done this work with her husband. They had done it together. They had planted seeds in the earth. The next day and the next and all their lives, when spring came they would have to bend their backs and do it until their hands and bones got twisted with rheumatism. But night would always bring sleep and forgetfulness.As they walked home slowly, Martin walked in front with another peasant talking about the sowing, and Mary walked behind, with her eyes on the ground, thinking. Cows were lowing at a distance.。

paraphrase1,They ate in silence,sleepy and bad-humored and……as man and wife.Paraphrase : Although they were still not fully awake, the young couple was already greatly excited, because that day was the first day of their first spring planting after they got married.2,But somehow the imminence of an event……made them dejected.Paraphrase : The couple had been looking forward to and preparing for this spring planting for a long time. But now that the day had finally arrived, strangely, they felt somehow a bit sad.3,Mary, with her shrewed woman’s mind,……and anxiety of her mating.a) Paraphrase : Mary, like all sharp and smart women, thought of many things in life when she got married.4,“Martin,”she said, “let us not begin this day cross with one another.”Paraphrase : “ Martin,” she said, “ let us not be rather angry or irritated with each other on the first day of our first spring sowing.”5,Still, as they walked silently……therewas not a soul about.Paraphrase: When they walked silently through the small village, they saw not a single person around them because they were earlier than everybody else.6,His eyes had a wild ,eager light in them……and of subjugating the earth.Paraphrase: His eyes shone and his only desire now was to prove what a strong man he was and how he could conquer the land.7,…he turned up the first sod with a crunching sound…Paraphrase: …he dug up the first piece of earth with grass and roots with his spade, making a crunching sound….8,…to drive out the sudden terror that…were unconscious of her presence.Paraphra se: …she began to work hard in order to get rid of the terror that suddenly seized her when she saw that her husband had suddenly changed from the loving husband she knew into a fierce-looking farmer who did not seem to be aware that his bride was with him.9,She became suddenly afraid of that pitiless,…she would sink again into its bosom. Paraphrase: She became afraid of the earth because it was going to force her to work like a slave and force her to struggle against poverty all her life until she died and was buried in it.10,Her short-lived love was gone…….to till the earth.Paraphrase: The love they had for each other did not last long. Their romance was now replaced by their necessity to face the hard work. From then on, she was merely her husban d’s helper and had to work side by side with him.11,And Martin, absolutely without thought,…covering the ridge with block earth…Paraphrase: Martin, on the other hand, had no time to waste on idle thought. He just concentrated on his work and worked with great energy.12,…there was a sharpness in the still thin air……as if they were living enemies. Paraphrase: The chilly and biting air of early spring made the peasants work fiercely with their spades, beating the sods as if they were enemies.13,Martin ate heartily,……his body open to the pure air.Paraphrase: The heavy work made Martin thirsty and hungry and made him enjoy his lunch and tea more.14,That was the signal for a general rising all along the little valley.Paraphrase: The noise was the signal for all the peasants to stand up and start working again.15,The breed is getting weaker.Paraphrase: The younger generation nowadays are becoming squeamish and can hardly bear hardship.16,Then she thought of the journey home……It passed in a moment.Paraphrase: When she thought of all the drudgery waiting for her at home,suddenly she wanted to break the chains on her as a peasant’s wife, but it only lasted a very short time. She immediately dismissed the idea.17,And that’s not saying the whole of it,…Paraphrase:And what I have said can not cover all the work we have done today….18,But night would bring sleep and forgetfulness.Paraphrase:But during the night the young couple would have a sound sleep which might help them to forget all the tiredness and unpleasant feelings resulting from the spring sowing.。

现代大学英语精读4-Unit2-Spring-Sowing原文Spring SowingIt was still dark when Martin Delaney and his wife Mary got up. Martin stood in his shirt by the window, rubbing his eyes and yawning, while Mary raked out the live coals that had lain hidden in the ashes on the hearth all night. Outside, cocks were crowing and a white streak was rising form the ground, as it were, and beginning to scatter the darkness. It was a February morning, dry, cold and starry.The couple sat down to their breakfast of tea, bread and butter, in silence. They had only been married the previous autumn and it was hateful leaving a warm bed at such and early hour. Martin, with his brown hair and eyes, his freckled face and his little fair moustache, looked too young to be married, and his wife looked hardly more than a girl, red-cheeked and blue-eyed, her black hair piled at the rear of her head with a large comb gleaming in the middle of the pile, Spanish fashion. They were both dressed in rough homespuns, and both wore the loose white shirt that Inverara peasants use for work in the fields.They ate in silence, sleepy and yet on fire with excitement, for it was the first day of their first spring sowing as man and wife. And each felt the glamour of that day on which they were to open up the earth together and plant seeds in it. But somehow the imminence of an event that had been long expected loved, feared and prepared for made them dejected. Mary, with her shrewd woman's mind, thought of as many things as there are in life as a woman would in the first joy and anxiety of her mating. But Martin's mind was fixed on one thought. Would he be able to prove himself a man worthy ofbeing the head of a family by dong his spring sowing well?In the barn after breakfast, when they were getting the potato seeds and the line for measuring the ground and the spade, Martin fell over a basket in the half-darkness of the barn, he swore and said that a man would be better off dead than.. But before he could finish whatever he was going to say, Mary had her arms around his waist and her face to his. "Martin," she said, "let us not begin this day cross with one another." And there was a tremor in her voice. And somehow, as they embraced, all their irritation and sleepiness left them. And they stood there embracing until at last Martin pushed her from him with pretended roughness and said: "Come, come, girl, it will be sunset before we begin at this rate."Still, as they walked silently in their rawhide shoes through the little hamlet, there was not a soul about. Lights were glimmering in the windows of a few cabins. The sky had a big grey crack in it in the east, as if it were going to burst in order to give birth to the sun. Birds were singing somewhere at a distance. Martin and Mary rested their baskets of seeds on a fence outside the village and Martin whispered to Mary proudly: "We are first, Mary." And they both looked back at the little cluster of cabins that was the centre of their world, with throbbing hearts. For the joy of spring had now taken complete hold of them.They reached the little field where they were to sow. It was a little triangular patch of ground under an ivy-covered limestone hill. The little field had been manured with seaweed some weeks before, and the weeds had rotted and whitened on the grass. And there was a big red heap of fresh seaweed lying in a corner by the fence to be spreadunder the seeds as they were laid. Martin, in spite of the cold,threw off everything above his waist except his striped woolen shirt. Then he spat on his hands, seized his spade and cried: "Now you are going to see what kind of a man you have, Mary." "There, now," said Mary, tying a little shawl closer under her chin."Aren't we boastful this early hour of the morning? Maybe I'll wait till sunset to see what kind of a man I have got."The work began. Martin measured the ground by the southern fence for the first ridge, a strip of ground four feet wide, and he placed the line along the edge and pegged it at each end. Then he spread fresh seaweed over the strip. Mary filled her apron with seeds and began to lay them in rows. When she was a little distance down the ridge, Martin advanced with his spade to the head, eager to commence."Now in the name of God," he cried, spitting on his palms, "let us raise the first sod!" "Oh, Martin, wait till I'm with you !" cried Mary, dropping her seeds on the ridge and running up to him .Her fingers outside her woolen mittens were numb with the cold, and she couldn't wipe them in her apron. Her cheeks seemed to be on fire. She put an arm round Martin's waist and stood looking at the green sod his spade was going to cut, with the excitement of a little child."Now for God's sake, girl, keep back!" said Martin gruffly. "Suppose anybody saw us like this in the field of our spring sowing, what would they take us for but a pair of useless, soft, empty-headed people that would be sure to die of hunger? Huh!" He spoke very rapidly, and his eyes were fixed on the ground before hm. His eyes had a wild, eager light in them as if some primeval impulse were burning within his brain and driving out every other desire but that of asserting his manhood and of subjugating the earth."Oh, what do we care who is looking?" said Mary; but she drew back at the same time and gazed distantly at the ground. Then Martin cut the sod, and pressing the spade deep into the earth with his foot, he turned up the first sod with a crunching sound as the grass roots were dragged out of the earth. Mary sighed and walked back hurriedly to her seeds with furrowed brows. She picked up her seeds and began to spread them rapidly to drive out the sudden terror that had seized her at that moment when she saw the fierce, hard look in her husband's eyes that were unconscious of her presence. She became suddenly afraid of that pitiless, cruel earth, the peasant's slave master that would keep her chained to hard work and poverty all her life until she would sink again into its bosom. Her short-lived love was gone. Henceforth she was only her husband's helper to till the earth. And Martin, absolutely without thought, worked furiously, covering the ridge with block earth, his sharp spade gleaming white as he whirled it sideways to beat the sods.Then, as the sun rose, the little valley beneath the ivy-covered hills became dotted with white shirts, and everywhere men worked madly, without speaking, and women spread seeds. There was no heat in the light of the sun, and there was a sharpness in the still thin air that made the men jump on their spade halts ferociously and beat the sods as if they were living enemies. Birds hopped silently before the spades, with their heads cocked sideways, watching for worms. Made brave by hunger, they often dashed under the spades to secure their food.Then, when the sun reached a certain point, all the women went back to the village to get dinner for their men, and the men worked on without stopping. Then the women returned, almost running, each carrying a tin can with a flannel tied around it anda little bundle tied with a white cloth, Martin threw down his spade when Mary arrived back in the field. Smiling at one another they sat under the hill for their meal .It was the same as their breakfast, tea and bread and butter."Ah," said Martin, when he had taken a long draught of tea form his mug, "is there anything in this world as fine as eating dinner out in the open like this after doing a good morning's work? There, I have done two ridges and a half. That's more than any man in the village could do. Ha!" And he looked at his wife proudly."Yes, isn't it lovely," said Mary, looking at the back ridges wistfully. She was just munching her bread and butter .The hurried trip to the village and the trouble of getting the tea ready had robbed her of her appetite. She had to keep blowing at the turf fire with the rim of her skirt, and the smoke nearly blinded her. But now, sitting on that grassy knoll, with the valley all round glistening with fresh seaweed and a light smoke rising from the freshly turned earth, a strange joy swept over her. It overpowered that other felling of dread that had been with her during the morning.Martin ate heartily, reveling in his great thirst and his great hunger, with every pore of his body open to the pure air. And he looked around at his neighbors' fields boastfully, comparing them with his own. Then he looked at his wife's little round black head and felt very proud of having her as his own. He leaned back on his elbow and took her hand in his. Shyly and in silence, not knowing what to say and ashamed of their gentle feelings, they finished eating and still sat hand in hand looking away into the distance. Everywhere the sowers were resting on little knolls, men, women and children sitting in silence.And the great calm of nature in spring filled the atmosphere around them. Everything seemed to sit still and wait until midday had passed. Only the gleaming sun chased westwards at a mighty pace, in and out through white clouds.Then in a distant field an old man got up, took his spade and began to clean the earth from it with a piece of stone. The rasping noise carried a long way in the silence. That was the signal for a general rising all along the little valley. Young men stretched themselves and yawned. They walked slowly back to their ridges.Martin's back and his wrists were getting sore, and Mary felt that if she stooped again over her seeds her neck would break, but neither said anything and soon they had forgotten their tiredness in the mechanical movement of their bodies. The strong smell of the upturned earth acted like a drug on their nerves.In the afternoon, when the sun was strongest, the old men of the village came out to look at their people sowing. Martin's grandfather, almost bent double over his thick stick stopped in the land outside the field and groaning loudly, he leaned over the fence.“God bless the work, "he called wheezily."And you, grandfather," replied the couple together, but they did not stop working.'Ha!" muttered the old man to himself. "He sows well and that woman is good too. They are beginning well."It was fifty years since he had begun with his Mary, full of hope and pride, and the merciless soil had hugged them to its bosom ever since, each spring without rest. Today,the old man, with his huge red nose and the spotted handkerchief tied around his skull under his black soft felt hat, watched his grandson work and gave him advice."Don't cut your sods so long," he would wheeze, "you areputting too much soil on your ridge."''Ah woman! Don't plant a seed so near the edge. The stalk will come out sideways." And they paid no heed to him."Ah," grumbled the old man," in my young days, when men worked from morning till night without tasting food, better work was done. But of course it can't be expected to be the same now. The breed is getting weaker. So it is."Then he began to cough in his chest and hobbled away to another field where his son Michael was working.By sundown Martin had five ridges finished. He threw down his spade and stretched himself. All his bones ached and he wanted to lie down and rest. "It's time to be going home, Mary," he said.Mary straightened herself, but she was too tired to reply. She looked at Martin wearily and it seemed to her that it was a great many years since they had set out that morning. Then she thought of the journey home and the trouble of feeding the pigs, putting the fowls into their coops and getting the supper ready, and a momentary flash of rebellion against the slavery of being a peasant's wife crossed her mind. It passed in a moment. Martin was saying, as he dressed himself:"Ha! It has been a good day's work. Five ridges done, and each one of them as straight as a steel rod. By God Mary, it's no boasting to say that you might well be proud ofbeing the wife of Martin Delaney. And that's not saying the whole of it ,my girl. You did your share better than any woman in Inverara could do it this blessed day."They stood for a few moments in silence, looking at the work they had done. All her dissatisfaction and weariness vanished form Mary's mind with the delicious feeling of comfort thatovercame her at having done this work with her husband. They had done it together. They had planted seeds in the earth. The next day and the next and all their lives, when spring came they would have to bend their backs and do it until their hands and bones got twisted with rheumatism. But night would always bring sleep and forgetfulness.As they walked home slowly, Martin walked in front with another peasant talking about the sowing, and Mary walked behind, with her eyes on the ground, thinking. Cows were lowing at a distance.。

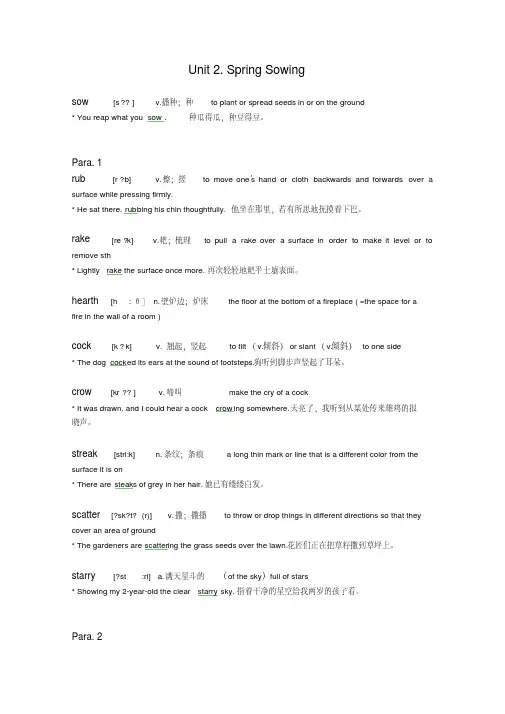

Unit 2. Spring Sowingsow [s??]v.播种;种to plant or spread seeds in or on the ground* You reap what you sow. 种瓜得瓜,种豆得豆。

Para. 1rub[r?b] v.擦;搓to move one’s hand or cloth backwards and forwards over a surface while pressing firmly.* He sat there, rubbing his chin thoughtfully.他坐在那里,若有所思地抚摸着下巴。

rake [re?k] v.耙;梳理to pull a rake over a surface in order to make it level or to remove sth* Lightly rake the surface once more.再次轻轻地耙平土壤表面。

hearth [hɑ:θ]n.壁炉边;炉床the floor at the bottom of a fireplace ( =the space for afire in the wall of a room )cock [k?k] v. 翘起,竖起to tilt(v.倾斜)or slant(v.倾斜)to one side* The dog cocked its ears at the sound of footsteps.狗听到脚步声竖起了耳朵。

crow[kr??] v.啼叫make the cry of a cock* It was drawn, and I could hear a cock crow ing somewhere.天亮了,我听到从某处传来雄鸡的报晓声。

streak [stri:k] n.条纹;条痕 a long thin mark or line that is a different color from the surface it is on* There are steaks of grey in her hair.她已有缕缕白发。

现代大学英语精读4-Unit2-Spring-Sowing原文Spring SowingIt was still dark when Martin Delaney and his wife Mary got up. Martin stood in his shirt by the window, rubbing his eyes and yawning, while Mary raked out the live coals that had lain hidden in the ashes on the hearth all night. Outside, cocks were crowing and a white streak was rising form the ground, as it were, and beginning to scatter the darkness. It was a February morning, dry, cold and starry.The couple sat down to their breakfast of tea, bread and butter, in silence. They had only been married the previous autumn and it was hateful leaving a warm bed at such and early hour. Martin, with his brown hair and eyes, his freckled face and his little fair moustache, looked too young to be married, and his wife looked hardly more than a girl, red-cheeked and blue-eyed, her black hair piled at the rear of her head with a large comb gleaming in the middle of the pile, Spanish fashion. They were both dressed in rough homespuns, and both wore the loose white shirt that Inverara peasants use for work in the fields.They ate in silence, sleepy and yet on fire with excitement, for it was the first day of their first spring sowing as man and wife. And each felt the glamour of that day on which they were to open up the earth together and plant seeds in it. But somehow the imminence of an event that had been long expected loved, feared and prepared for made them dejected. Mary, with her shrewd woman's mind, thought of as many things as there are in life as a woman would in the first joy and anxiety of her mating. But Martin's mind was fixed on one thought. Would he be able to prove himself a man worthy ofbeing the head of a family by dong his spring sowing well?In the barn after breakfast, when they were getting the potato seeds and the line for measuring the ground and the spade, Martin fell over a basket in the half-darkness of the barn, he swore and said that a man would be better off dead than.. But before he could finish whatever he was going to say, Mary had her arms around his waist and her face to his. "Martin," she said, "let us not begin this day cross with one another." And there was a tremor in her voice. And somehow, as they embraced, all their irritation and sleepiness left them. And they stood there embracing until at last Martin pushed her from him with pretended roughness and said: "Come, come, girl, it will be sunset before we begin at this rate."Still, as they walked silently in their rawhide shoes through the little hamlet, there was not a soul about. Lights were glimmering in the windows of a few cabins. The sky had a big grey crack in it in the east, as if it were going to burst in order to give birth to the sun. Birds were singing somewhere at a distance. Martin and Mary rested their baskets of seeds on a fence outside the village and Martin whispered to Mary proudly: "We are first, Mary." And they both looked back at the little cluster of cabins that was the centre of their world, with throbbing hearts. For the joy of spring had now taken complete hold of them.They reached the little field where they were to sow. It was a little triangular patch of ground under an ivy-covered limestone hill. The little field had been manured with seaweed some weeks before, and the weeds had rotted and whitened on the grass. And there was a big red heap of fresh seaweed lying in a corner by the fence to be spreadunder the seeds as they were laid. Martin, in spite of the cold,threw off everything above his waist except his striped woolen shirt. Then he spat on his hands, seized his spade and cried: "Now you are going to see what kind of a man you have, Mary." "There, now," said Mary, tying a little shawl closer under her chin."Aren't we boastful this early hour of the morning? Maybe I'll wait till sunset to see what kind of a man I have got."The work began. Martin measured the ground by the southern fence for the first ridge, a strip of ground four feet wide, and he placed the line along the edge and pegged it at each end. Then he spread fresh seaweed over the strip. Mary filled her apron with seeds and began to lay them in rows. When she was a little distance down the ridge, Martin advanced with his spade to the head, eager to commence."Now in the name of God," he cried, spitting on his palms, "let us raise the first sod!" "Oh, Martin, wait till I'm with you !" cried Mary, dropping her seeds on the ridge and running up to him .Her fingers outside her woolen mittens were numb with the cold, and she couldn't wipe them in her apron. Her cheeks seemed to be on fire. She put an arm round Martin's waist and stood looking at the green sod his spade was going to cut, with the excitement of a little child."Now for God's sake, girl, keep back!" said Martin gruffly. "Suppose anybody saw us like this in the field of our spring sowing, what would they take us for but a pair of useless, soft, empty-headed people that would be sure to die of hunger? Huh!" He spoke very rapidly, and his eyes were fixed on the ground before hm. His eyes had a wild, eager light in them as if some primeval impulse were burning within his brain and driving out every other desire but that of asserting his manhood and of subjugating the earth."Oh, what do we care who is looking?" said Mary; but she drew back at the same time and gazed distantly at the ground. Then Martin cut the sod, and pressing the spade deep into the earth with his foot, he turned up the first sod with a crunching sound as the grass roots were dragged out of the earth. Mary sighed and walked back hurriedly to her seeds with furrowed brows. She picked up her seeds and began to spread them rapidly to drive out the sudden terror that had seized her at that moment when she saw the fierce, hard look in her husband's eyes that were unconscious of her presence. She became suddenly afraid of that pitiless, cruel earth, the peasant's slave master that would keep her chained to hard work and poverty all her life until she would sink again into its bosom. Her short-lived love was gone. Henceforth she was only her husband's helper to till the earth. And Martin, absolutely without thought, worked furiously, covering the ridge with block earth, his sharp spade gleaming white as he whirled it sideways to beat the sods.Then, as the sun rose, the little valley beneath the ivy-covered hills became dotted with white shirts, and everywhere men worked madly, without speaking, and women spread seeds. There was no heat in the light of the sun, and there was a sharpness in the still thin air that made the men jump on their spade halts ferociously and beat the sods as if they were living enemies. Birds hopped silently before the spades, with their heads cocked sideways, watching for worms. Made brave by hunger, they often dashed under the spades to secure their food.Then, when the sun reached a certain point, all the women went back to the village to get dinner for their men, and the men worked on without stopping. Then the women returned, almost running, each carrying a tin can with a flannel tied around it anda little bundle tied with a white cloth, Martin threw down his spade when Mary arrived back in the field. Smiling at one another they sat under the hill for their meal .It was the same as their breakfast, tea and bread and butter."Ah," said Martin, when he had taken a long draught of tea form his mug, "is there anything in this world as fine as eating dinner out in the open like this after doing a good morning's work? There, I have done two ridges and a half. That's more than any man in the village could do. Ha!" And he looked at his wife proudly."Yes, isn't it lovely," said Mary, looking at the back ridges wistfully. She was just munching her bread and butter .The hurried trip to the village and the trouble of getting the tea ready had robbed her of her appetite. She had to keep blowing at the turf fire with the rim of her skirt, and the smoke nearly blinded her. But now, sitting on that grassy knoll, with the valley all round glistening with fresh seaweed and a light smoke rising from the freshly turned earth, a strange joy swept over her. It overpowered that other felling of dread that had been with her during the morning.Martin ate heartily, reveling in his great thirst and his great hunger, with every pore of his body open to the pure air. And he looked around at his neighbors' fields boastfully, comparing them with his own. Then he looked at his wife's little round black head and felt very proud of having her as his own. He leaned back on his elbow and took her hand in his. Shyly and in silence, not knowing what to say and ashamed of their gentle feelings, they finished eating and still sat hand in hand looking away into the distance. Everywhere the sowers were resting on little knolls, men, women and children sitting in silence.And the great calm of nature in spring filled the atmosphere around them. Everything seemed to sit still and wait until midday had passed. Only the gleaming sun chased westwards at a mighty pace, in and out through white clouds.Then in a distant field an old man got up, took his spade and began to clean the earth from it with a piece of stone. The rasping noise carried a long way in the silence. That was the signal for a general rising all along the little valley. Young men stretched themselves and yawned. They walked slowly back to their ridges.Martin's back and his wrists were getting sore, and Mary felt that if she stooped again over her seeds her neck would break, but neither said anything and soon they had forgotten their tiredness in the mechanical movement of their bodies. The strong smell of the upturned earth acted like a drug on their nerves.In the afternoon, when the sun was strongest, the old men of the village came out to look at their people sowing. Martin's grandfather, almost bent double over his thick stick stopped in the land outside the field and groaning loudly, he leaned over the fence.“God bless the work, "he called wheezily."And you, grandfather," replied the couple together, but they did not stop working.'Ha!" muttered the old man to himself. "He sows well and that woman is good too. They are beginning well."It was fifty years since he had begun with his Mary, full of hope and pride, and the merciless soil had hugged them to its bosom ever since, each spring without rest. Today,the old man, with his huge red nose and the spotted handkerchief tied around his skull under his black soft felt hat, watched his grandson work and gave him advice."Don't cut your sods so long," he would wheeze, "you areputting too much soil on your ridge."''Ah woman! Don't plant a seed so near the edge. The stalk will come out sideways." And they paid no heed to him."Ah," grumbled the old man," in my young days, when men worked from morning till night without tasting food, better work was done. But of course it can't be expected to be the same now. The breed is getting weaker. So it is."Then he began to cough in his chest and hobbled away to another field where his son Michael was working.By sundown Martin had five ridges finished. He threw down his spade and stretched himself. All his bones ached and he wanted to lie down and rest. "It's time to be going home, Mary," he said.Mary straightened herself, but she was too tired to reply. She looked at Martin wearily and it seemed to her that it was a great many years since they had set out that morning. Then she thought of the journey home and the trouble of feeding the pigs, putting the fowls into their coops and getting the supper ready, and a momentary flash of rebellion against the slavery of being a peasant's wife crossed her mind. It passed in a moment. Martin was saying, as he dressed himself:"Ha! It has been a good day's work. Five ridges done, and each one of them as straight as a steel rod. By God Mary, it's no boasting to say that you might well be proud ofbeing the wife of Martin Delaney. And that's not saying the whole of it ,my girl. You did your share better than any woman in Inverara could do it this blessed day."They stood for a few moments in silence, looking at the work they had done. All her dissatisfaction and weariness vanished form Mary's mind with the delicious feeling of comfort thatovercame her at having done this work with her husband. They had done it together. They had planted seeds in the earth. The next day and the next and all their lives, when spring came they would have to bend their backs and do it until their hands and bones got twisted with rheumatism. But night would always bring sleep and forgetfulness.As they walked home slowly, Martin walked in front with another peasant talking about the sowing, and Mary walked behind, with her eyes on the ground, thinking. Cows were lowing at a distance.。

Spring SowingIt was still dark when Martin Delaney and his wife Mary got up. Martin stood in his shirt by the window, rubbing his eyes and yawning, while Mary raked out the live coals that had lain hidden in the ashes on the hearth all night. Outside, cocks were crowing and a white streak was rising form the ground, as it were, and beginning to scatter the darkness. It was a February morning, dry, cold and starry.The couple sat down to their breakfast of tea, bread and butter, in silence. They had only been married the previous autumn and it was hateful leaving a warm bed at such and early hour. Martin, with his brown hair and eyes, his freckled face and his little fair moustache, looked too young to be married, and his wife looked hardly more than a girl, red-cheeked and blue-eyed, her black hair piled at the rear of her head with a large comb gleaming in the middle of the pile, Spanish fashion. They were both dressed in rough homespuns, and both wore the loose white shirt that Inverara peasants use for work in the fields.They ate in silence, sleepy and yet on fire with excitement, for it was the first day of their first spring sowing as man and wife. And each felt the glamour of that day on which they were to open up the earth together and plant seeds in it. But somehow the imminence of an event that had been long expected loved, feared and prepared for made them dejected.Mary, with her shrewd woman's mind, thought of as many things as there are in life as a woman would in the first joy and anxiety of her mating. But Martin's mind was fixed on one thought. Would he be able to prove himself a man worthy of being the head of a family by dong his spring sowing well?In the barn after breakfast, when they were getting the potato seeds and the line for measuring the ground and the spade, Martin fell over a basket in the half-darkness of the barn, he swore and said that a man would be better off dead than.. But before he could finish whatever he was going to say, Mary had her arms around his waist and her face to his. "Martin," she said, "let us not begin this day cross with one another." And there was a tremor in her voice. And somehow, as they embraced, all their irritation and sleepiness left them. And they stood there embracing until at last Martin pushed her from him with pretended roughness and said: "Come, come, girl, it will be sunset before we begin at this rate."Still, as they walked silently in their rawhide shoes through the little hamlet, there was not a soul about. Lights were glimmering in the windows of a few cabins. The sky had a big grey crack in it in the east, as if it were going to burst in order to give birth to the sun. Birds were singing somewhere at a distance. Martin and Mary rested their baskets of seeds on a fence outside the village and Martin whispered to Mary proudly: "We are first, Mary." And they both looked back at the littlecluster of cabins that was the centre of their world, with throbbing hearts. For the joy of spring had now taken complete hold of them.They reached the little field where they were to sow. It was a little triangular patch of ground under an ivy-covered limestone hill. The little field had been manured with seaweed some weeks before, and the weeds had rotted and whitened on the grass. And there was a big red heap of fresh seaweed lying in a corner by the fence to be spread under the seeds as they were laid. Martin, in spite of the cold, threw off everything above his waist except his striped woolen shirt. Then he spat on his hands, seized his spade and cried: "Now you are going to see what kind of a man you have, Mary.""There, now," said Mary, tying a little shawl closer under her chin. "Aren't we boastful this early hour of the morning? Maybe I'll wait till sunset to see what kind of a man I have got."The work began. Martin measured the ground by the southern fence for the first ridge, a strip of ground four feet wide, and he placed the line along the edge and pegged it at each end. Then he spread fresh seaweed over the strip. Mary filled her apron with seeds and began to lay them in rows. When she was a little distance down the ridge, Martin advanced with his spade to the head, eager to commence."Now in the name of God," he cried, spitting on his palms, "let us raise the first sod!""Oh, Martin, wait till I'm with you !" cried Mary, dropping her seeds on the ridge and running up to him .Her fingers outside her woolen mittens were numb with the cold, and she couldn't wipe them in her apron. Her cheeks seemed to be on fire. She put an arm round Martin's waist and stood looking at the green sod his spade was going to cut, with the excitement of a little child."Now for God's sake, girl, keep back!" said Martin gruffly. "Suppose anybody saw us like this in the field of our spring sowing, what would they take us for but a pair of useless, soft, empty-headed people that would be sure to die of hunger? Huh!" He spoke very rapidly, and his eyes were fixed on the ground before hm. His eyes had a wild, eager light in them as if some primeval impulse were burning within his brain and driving out every other desire but that of asserting his manhood and of subjugating the earth."Oh, what do we care who is looking?" said Mary; but she drew back at the same time and gazed distantly at the ground. Then Martin cut the sod, and pressing the spade deep into the earth with his foot, he turned up the first sod with a crunching sound as the grass roots were dragged out of the earth. Mary sighed and walked back hurriedly to her seeds with furrowed brows. She picked up her seeds and began to spread them rapidly to drive out the sudden terror that had seized her at that moment when she saw the fierce, hard look in her husband's eyes that wereunconscious of her presence. She became suddenly afraid of that pitiless, cruel earth, the peasant's slave master that would keep her chained to hard work and poverty all her life until she would sink again into its bosom. Her short-lived love was gone. Henceforth she was only her husband's helper to till the earth. And Martin, absolutely without thought, worked furiously, covering the ridge with block earth, his sharp spade gleaming white as he whirled it sideways to beat the sods.Then, as the sun rose, the little valley beneath the ivy-covered hills became dotted with white shirts, and everywhere men worked madly, without speaking, and women spread seeds. There was no heat in the light of the sun, and there was a sharpness in the still thin air that made the men jump on their spade halts ferociously and beat the sods as if they were living enemies. Birds hopped silently before the spades, with their heads cocked sideways, watching for worms. Made brave by hunger, they often dashed under the spades to secure their food.Then, when the sun reached a certain point, all the women went back to the village to get dinner for their men, and the men worked on without stopping. Then the women returned, almost running, each carrying a tin can with a flannel tied around it and a little bundle tied with a white cloth, Martin threw down his spade when Mary arrived back in the field. Smiling at one another they sat under the hill for their meal .It was the same as their breakfast, tea and bread and butter."Ah," said Martin, when he had taken a long draught of tea form his mug, "is there anything in this world as fine as eating dinner out in the open like this after doing a good morning's work? There, I have done two ridges and a half. That's more than any man in the village could do. Ha!" And he looked at his wife proudly."Yes, isn't it lovely," said Mary, looking at the back ridges wistfully. She was just munching her bread and butter .The hurried trip to the village and the trouble of getting the tea ready had robbed her of her appetite. She had to keep blowing at the turf fire with the rim of her skirt, and the smoke nearly blinded her. But now, sitting on that grassy knoll, with the valley all round glistening with fresh seaweed and a light smoke rising from the freshly turned earth, a strange joy swept over her. It overpowered that other felling of dread that had been with her during the morning.Martin ate heartily, reveling in his great thirst and his great hunger, with every pore of his body open to the pure air. And he looked around at his neighbors' fields boastfully, comparing them with his own. Then he looked at his wife's little round black head and felt very proud of having her as his own. He leaned back on his elbow and took her hand in his. Shyly and in silence, not knowing what to say and ashamed of their gentle feelings, they finished eating and still sat hand in hand looking away into the distance. Everywhere the sowers were resting on little knolls, men,women and children sitting in silence. And the great calm of nature in spring filled the atmosphere around them. Everything seemed to sit still and wait until midday had passed. Only the gleaming sun chased westwards at a mighty pace, in and out through white clouds.Then in a distant field an old man got up, took his spade and began to clean the earth from it with a piece of stone. The rasping noise carried a long way in the silence. That was the signal for a general rising all along the little valley. Young men stretched themselves and yawned. They walked slowly back to their ridges.Martin's back and his wrists were getting sore, and Mary felt that if she stooped again over her seeds her neck would break, but neither said anything and soon they had forgotten their tiredness in the mechanical movement of their bodies. The strong smell of the upturned earth acted like a drug on their nerves.In the afternoon, when the sun was strongest, the old men of the village came out to look at their people sowing. Martin's grandfather, almost bent double over his thick stick stopped in the land outside the field and groaning loudly, he leaned over the fence.“God bless the work, "he called wheezily."And you, grandfather," replied the couple together, but they did not stop working.'Ha!" muttered the old man to himself. "He sows well and that woman isgood too. They are beginning well."It was fifty years since he had begun with his Mary, full of hope and pride, and themerciless soil had hugged them to its bosom ever since, each spring without rest. Today, the old man, with his huge red nose and the spotted handkerchief tied around his skull under his black soft felt hat, watched his grandson work and gave him advice."Don't cut your sods so long," he would wheeze, "you are putting too much soil on yourridge."''Ah woman! Don't plant a seed so near the edge. The stalk will come out sideways."And they paid no heed to him."Ah," grumbled the old man," in my young days, when men worked from morning till night without tasting food, better work was done. But of course it can't be expected to be the same now. The breed is getting weaker. So it is."Then he began to cough in his chest and hobbled away to another field where his sonMichael was working.By sundown Martin had five ridges finished. He threw down his spade and stretched himself. All his bones ached and he wanted to lie down andrest. "It's time to be going home, Mary," he said.Mary straightened herself, but she was too tired to reply. She looked at Martin wearily and it seemed to her that it was a great many years since they had set out that morning. Then she thought of the journey home and the trouble of feeding the pigs, putting the fowls into their coops and getting the supper ready, and a momentary flash of rebellion against the slavery of being a peasant's wife crossed her mind. It passed in a moment. Martin was saying, as he dressed himself:"Ha! It has been a good day's work. Five ridges done, and each one of them as straight as a steel rod. By God Mary, it's no boasting to say that you might well be proud of being the wife of Martin Delaney. And that's not saying the whole of it ,my girl. You did your share better than any woman in Inverara could do it this blessed day."They stood for a few moments in silence, looking at the work they had done. All her dissatisfaction and weariness vanished form Mary's mind with the delicious feeling of comfort that overcame her at having done this work with her husband. They had done it together. They had planted seeds in the earth. The next day and the next and all their lives, when spring came they would have to bend their backs and do it until their hands and bones got twisted with rheumatism. But night would always bring sleep and forgetfulness.As they walked home slowly, Martin walked in front with another peasanttalking about the sowing, and Mary walked behind, with her eyes on the ground, thinking. Cows were lowing at a distance.。

精读4 Unit 2 课后练习答案Vocabulary1. Into English1. assert one’s manhood 6. rub his eyes2. cross one’s mind 7. munch her bead and butter3. measure the ground 8. overpower that feeling of dread4. secure one’s food 9. carry a long way5. scatter the darkness 10. bend their backsInto Chinese1. 燃烧着的煤 6. 一家之主2. 他那长满雀斑的脸7. 一颗怦怦直跳的心3. 淡淡的八字须8. 一组山间小屋4. (不好的)事情迫在眉睫9. 一块狭长的地5. 一位精明的妇女10. 一副凶猛严厉的表情3.1. Zhuge Liang pretended to be very calm and succeed in hiding the fact from Sima Yi that the city was really ungrounded. He proved himself worthy of the admiration he had received.2. He knew that a bloody battle was imminent and his army was terribly outnumbered. So he pretended to be retreating quickly to the rear. Actually he was laying a trap for the enemy troops.3. Social Darwinists asserted that we can compare human society to the animal world. It did not cross their minds that human beings could be different from other animals. They relied on their brain rather than their instinct.4. These mass-produced chickens can not compare with the chickens we used to raise at home. Chicken farms may have increased the output, but they have robbed the chickens of their good taste.5. The financial bubbles finally burst, causing a serious crisis that swept over the whole world.6. Thanks to our price edge, our exports to that region increased by 30% compared with the same period the previous year.7. The reporters were all bursting with questions. But the government spokesman/spokesperson said that all she knew was that people were watching a play when some thirty armed terrorists burst into the theater.8. When the prisoners burst out singing, the prison warden was frightened.9. The area is dotted with factories. It also has holiday inns dotted around the whole island. But there are already signs that many local people will rebel against this trend.10. He declared that all the rebels would be pardoned if they laid down their arms.41 B2 A3 C4 C5 B6 D7 D8 C9 A10 D51.1.bosom, brest, bosom2. chest3. chest4. brest,bosom5. breast6. breast21. jump/leap2. leaped3. skip, jumped/sprang4. jumping5. hopping/jumping, leaping/skipping6. skip/jump31. verge2. verge3. border4. edge5. brim6. rim7. edge41. swearing2. curse, curse3. abused4. calling names/ name-calling51. rubbing2. scraped3. scratch4. scraped5. scratched6. rub, scrape6ScatteredSpreadSprayedSpreadingScattered6.1. clearly/evidently/obviously whole-heartedly/heartily/greedily/hungrily2. fiercely/furiously/feverishly3. gruffly/sharply/rudely/roughly4. doubtlessly/undoubtedly/unquestionably/undeniably/ indisputablyproudly/arrogantly/boastfully5. cruelly/brutally/heartlessly/mercilessly/pitilessly/remorselessly/savagely/ruthlessly6. oddly/strangly7. coolly/calmly/evenly/placidly8. convincingly/persuasively/rationally completely/entirely/wholly/thoroughly9. greatly/ dramatically/considerably/enormously/immenselyGrammar1.if2.suppose/ supposing3.If4.only if5.If6.even if7.unless8.Suppose/Supposing9.If10.If2. 2.1. As the saying goes, there’s no smoke without fire.2. There’s no denying that the film has no equal in cinema history.3. I warned him about the danger involved, but he paid no heed to my warning.4. There’s no generally accepted definition of happiness.5. These are no ordinary students; they are going to be trained as astronauts.’s financial problems.6. There are no easy or painless solutions to the company7. Away from home for the first time, college students have to do day-day chores themselves. It’s no bad thing.8. The two sides are so far apart on key issues that there’s no telling how long the talks could drag on.9. That’s the kind of holiday I dream of—no telephone, no TV and no worries.10. Some of the nation’s top economists say that they see no sign of economicrecovery in the country.4此时此刻西里尔●博吉斯先生装扮成一位身着袍服的牧师,除此之外,倒也看不出他有什么邪恶阴险之处。