1933老场坊基础资料-2012联合课题 with english2.0

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:5.67 MB

- 文档页数:37

1933老场坊建筑介绍

1933老场坊是上海市黄浦区的一处历史建筑,建于1933年,原为英国人建造的畜牧场。

该建筑群占地面积约为3000平方米,由四栋建筑组成,包括两栋六层高的建筑和两栋四层高的建筑。

这些建筑物的设计灵感来自于英国的工业建筑,采用了当时最先进的建筑技术和材料,如钢筋混凝土和玻璃幕墙。

在建筑物的设计中,建筑师注重了建筑的功能性和美学价值。

建筑物的外观采用了简洁的几何形状和对称的布局,使其看起来非常现代化。

建筑物内部的空间布局也非常合理,可以满足不同的使用需求。

例如,建筑物的中央大厅可以用作展览、演出和会议等多种用途。

在历史上,1933老场坊曾经是上海市的一个畜牧场,后来又被用作食品加工厂和仓库。

在20世纪90年代,这些建筑物被改造成了一个文化创意产业园区,吸引了许多艺术家、设计师和创业者入驻。

如今,1933老场坊已经成为上海市的一个知名景点,吸引了大量的游客前来参观。

除了其独特的建筑风格和历史背景外,1933老场坊还有许多其他的特色。

例如,建筑物内部有许多精美的艺术品和装饰品,如雕塑、壁画和灯具等。

此外,建筑物内还有许多有趣的商店、餐厅和咖啡馆,可以让游客在欣赏建筑之余,享受美食和购物的乐趣。

1933老场坊是一处非常有特色的历史建筑,它不仅展示了上海市的建筑文化和历史,还成为了一个文化创意产业的中心,为城市的发展做出了重要的贡献。

上海1933老场坊建筑解析一、上海1933老场坊的基本情况上海1933老场坊那可是超酷的建筑。

它的位置在上海,这地方到处都充满着那种老上海的韵味。

这个建筑啊,从外面看就很有特点,整体的轮廓特别硬朗,就像一个沉默的巨人站在那里。

它的外墙有着一种独特的质感,摸上去虽然粗糙,但是却能感受到岁月的痕迹。

它以前是干啥的呢?原来是个宰牲场呢。

可别小瞧这个用途,就是因为这个用途,它的建筑结构设计得超级精妙。

那里面的通道啊,就像迷宫一样,弯弯绕绕的。

我第一次进去的时候,感觉自己像是走进了一个神秘的异世界,都有点找不着北了。

二、建筑风格的独特之处1. 建筑结构它的结构那是相当的复杂又有序。

有着好多的廊桥,这些廊桥在空中交错纵横,就像一个巨大的蜘蛛网悬在空中。

还有那些混凝土的柱子,又粗又壮,稳稳地支撑着整个建筑,就像一个个忠诚的卫士。

这些柱子的形状也不是普通的圆形或者方形,而是有着独特的几何形状,看起来特别有艺术感。

2. 空间布局空间布局方面也是很绝的。

各个区域之间既相互独立又有着某种联系。

比如说那些屠宰的区域,虽然现在已经没有那种血腥的场面了,但是从空间的大小和布局,还能想象出当年的场景。

而且有一些小的房间和大的空间相互搭配,小房间就像一个个小盒子一样,而大空间则像是一个大舞台,这种对比特别有趣。

3. 采光设计采光更是一绝。

通过一些巧妙的窗户和孔洞的设计,光线会在不同的时间以不同的角度照进来。

有时候是一束柔和的光,像一把利剑一样穿过黑暗的空间;有时候是一片朦胧的光,让整个空间都变得很有氛围感。

这采光设计既满足了当时的使用需求,又在现在成为了一种独特的视觉享受。

三、建筑的艺术价值和文化意义1. 艺术价值在艺术价值上,这个建筑简直就是一个艺术品。

它融合了好多建筑元素,那些线条、形状、空间的组合,就像是一个画家精心绘制的画卷。

对于学建筑的我们来说,这里就像是一个大课堂,能看到很多书本上学不到的建筑创意。

而且它吸引了很多摄影爱好者来拍照,不管从哪个角度拍,都能拍出很有艺术感的照片。

1.高考考查本模块主要集中在两次世界大战以及二战后的国际关系格局的调整上,尤其是国际联盟和联合国、凡尔赛——华盛顿体系和雅尔塔体系等。

2.第二次世界大战给人类带来的巨大灾难是高考考查的主要内容,反思战争、追求和平是高考试题命题的主题价值所在。

3.高考命题与时政热点联系密切,如中东问题、朝鲜半岛问题、联合国的作用、伊拉克局势等。

【专题讲解】1.第一次世界大战和第二次世界大战2.凡尔赛——华盛顿体系和雅尔塔体制3.际联盟与联合国4.二战后的局部战争5.七八十年代美苏等国由紧张对抗到谋求缓和对话的背景和过程。

6.现代中国的对外关系7.20世纪以来世界形势的发展演变(2)1939年9月德军突袭波兰,第二次世界大战全面爆发。

德随着战争规模的不断扩大,反法西斯国家逐渐联合起来,结成世界反法西斯同盟。

斯大林格勒战役的胜利改变了苏德战场的形势,是第二次世界大战的重要转折点。

美军在中途岛海战中取得的成功,使太平洋战场形势发生了重大转折。

英军在阿拉曼战役中获胜,使北非战场形势发生了转折。

开罗和德黑兰会议后,盟军在诺曼底登陆,开辟了欧洲第二战场。

在世界反法西斯同盟力量的进攻下,德国和日本先后无条件投降。

第二次世界大战是人类历史上规模空前的战争,它推动了人类历史的进程,在很多方面产生了深远影响。

二战中,苏美英等不同社会制度的国家结成了世界反法西斯同盟,同盟国之间在政治上互相协商,军事上互相配合,物质上互相支援,对加速反法西斯战争的胜利起了重要作用。

这场战争告诉我们:社会制度与意识形态不相同的国家在平等的基础上能够联合起来,共同对付人类生存与发展面临的挑战。

人类的命运休戚相关,只有加强国际合作,才能求得共同发展。

(3)二战后期随着反法西斯战争的胜利,战时同盟的基础动摇,美苏两大国之间的全球战略分歧逐渐扩大,战时同盟发生分裂。

世界主要矛盾由二战中的法西斯国家同反法西斯联盟的生死较量变为美苏为首的两大阵营的全面对抗。

二战后,世界政治格局的演变经历了雅塔尔体系建立、美苏冷战、两大军事政治集团的形成、两大阵营的分化和三个世界的形成,美苏争霸、苏东剧变。

2012年会考内容提纲:政治模块第一单元古代中国的政治制度一.中国早期(夏商周)政治制度 B1.宗法制(1)含义:以父系血缘为纽带,规定宗族内的嫡庶系统的一种制度。

(2)核心:嫡长子继承制(3)作用:通过血缘亲疏,确立起一整套土地、财产和政治地位的分配与继承制度,保障各级贵族能够享受“世卿世禄”的特权;防止内部纷争,强化王权,把“国”与家密切地结合在一起。

2.分封制:(1)含义:分封制又称封邦建国,是周王室将土地连同土地上的人封赐给臣下,广建封国,用以拱卫周王室。

(2)分封对象:同姓亲族是主体,还有功臣、姻亲、殷商旧族。

(3)作用:使西周贵族集团形成了“周王-诸侯-卿大夫-士”的等级序列,巩固了统治。

二.中国古代中央集权制度的形成和发展B(部分C)(一)秦朝——创立B1.内容:(1)始皇帝(2)三公九卿(三公:丞相—“百官之首”;太尉—掌军事;御史大夫—掌监察)(3)郡县制。

(郡县官吏由中央任免)2.特点:以皇帝为中心形成从中央到地方的统治机构;官位不世袭,实行俸禄制度,由皇帝任免;官职有明确分工,既互相配合,又相互牵制。

3.秦朝中央集权的影响C:打破了传统贵族的分封制;奠定了中国古代大一统王朝的政治基础;对此后2000多年的中国政治与社会产生影响。

(二)汉至元——发展:1.汉武帝加强中央集权(1)措施:建立中朝(加强皇权)、设置刺史(监察地方)、推恩令(削弱王国势力)。

(2)影响:巩固和发展了大一统局面,促进社会经济发展。

2.唐朝的三省六部制(1)三省六部:中书省(起草政令)、门下省(审核,封驳审议)、尚书省(执行,下辖六部)(2)作用:相互牵制、互为补充、分工明确、提高效率;分割了相权,加强了皇权。

3.汉至元中央集权发展特点:皇权不断加强,相权不断受到制约而削弱;中央权力不断加强,地方权力不断削弱。

4.明清——君主专制空前加强明:明太祖废丞相;明成祖设内阁(朱批、票拟);清:雍正设军机处,专制皇权达到顶峰。

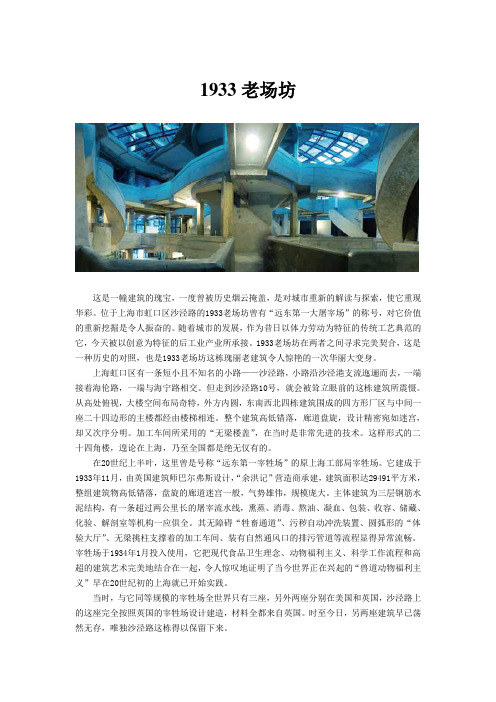

1933老场坊这是一幢建筑的瑰宝,一度曾被历史烟云掩盖,是对城市重新的解读与探索,使它重现华彩。

位于上海市虹口区沙泾路的1933老场坊曾有“远东第一大屠宰场”的称号,对它价值的重新挖掘是令人振奋的。

随着城市的发展,作为昔日以体力劳动为特征的传统工艺典范的它,今天被以创意为特征的后工业产业所承接。

1933老场坊在两者之间寻求完美契合,这是一种历史的对照,也是1933老场坊这栋瑰丽老建筑令人惊艳的一次华丽大变身。

上海虹口区有一条短小且不知名的小路——沙泾路,小路沿沙泾港支流迤逦而去,一端接着海伦路,一端与海宁路相交。

但走到沙泾路10号,就会被耸立眼前的这栋建筑所震慑。

从高处俯视,大楼空间布局奇特,外方内圆,东南西北四栋建筑围成的四方形厂区与中间一座二十四边形的主楼都经由楼梯相连。

整个建筑高低错落,廊道盘旋,设计精密宛如迷宫,却又次序分明。

加工车间所采用的“无梁楼盖”,在当时是非常先进的技术。

这样形式的二十四角楼,遑论在上海,乃至全国都是绝无仅有的。

在20世纪上半叶,这里曾是号称“远东第一宰牲场”的原上海工部局宰牲场。

它建成于1933年11月,由英国建筑师巴尔弗斯设计,“余洪记”营造商承建,建筑面积达29491平方米,整组建筑物高低错落,盘旋的廊道迷宫一般,气势雄伟,规模庞大。

主体建筑为三层钢筋水泥结构,有一条超过两公里长的屠宰流水线,熏蒸、消毒、熬油、凝血、包装、收容、储藏、化验、解剖室等机构一应俱全。

其无障碍“牲畜通道”、污秽自动冲洗装置、圆弧形的“体验大厅”、无梁挑柱支撑着的加工车间、装有自然通风口的排污管道等流程显得异常流畅。

宰牲场于1934年1月投入使用,它把现代食品卫生理念、动物福利主义、科学工作流程和高超的建筑艺术完美地结合在一起,令人惊叹地证明了当今世界正在兴起的“兽道动物福利主义”早在20世纪初的上海就已开始实践。

当时,与它同等规模的宰牲场全世界只有三座,另外两座分别在美国和英国,沙泾路上的这座完全按照英国的宰牲场设计建造,材料全都来自英国。

World J Urol (2012) 30:437–443DOI 10.1007/s00345-011-0779-8TOPIC PAPERPelvic X oor muscle training in treatment of female stress urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse and sexual dysfunctionKari BøReceived: 11 September 2011 / Accepted: 26 September 2011 / Published online: 9 October 2011© Springer-Verlag 2011AbstractObjectives The objectives of the present review was to present and discuss evidence for pelvic X oor muscle (PFM) training on female stress urinary incontinence (SUI), pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and sexual dysfunction.Methods This manuscript is based on conclusions and data presented in systematic reviews on PFM training for SUI, POP and sexual dysfunction. Cochrane reviews, the 4th International Consultation on Incontinence, the NICE guidelines and the Health Technology Assessment were used as data sources. In addition, a new search on Pubmed was done from 2008 to 2011. Only data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in English language is presented and discussed.Results There is Level 1, Grade A evidence that PFM training is e V ective in treatment of SUI. Short-term cure rates assessed as <2g of leakage on pad testing vary between 35 and 80%. To date there are 5 RCTs showing signi W cant e V ect of PFM training on either POP stage, symptoms or PFM morphology. Supervised and more intensive training is more e V ective than unsupervised training. There are no adverse e V ects. There is a lack of RCTs addressing the e V ect of PFM training on sexual dysfunction.Conclusions PFM training should be W rst line treatment for SUI and POP, but the training needs proper instruction and close follow-up to be e V ective. More high quality RCTs are warranted on PFM training to treat sexual dysfunction.Keywords Pelvic X oor muscle training · Pelvic organ prolapse · Strength · Sexual dysfunction · Stress urinary incontinenceIntroductionIt has been estimated that during a woman’s lifespan there is an 11% risk of surgery for pelvic X oor dysfunctions such as urinary incontinence (UI) and pelvic organ pro-lapse (POP) [1]. Pelvic X oor disorders or dysfunction has been described by Bump and Norton [2] as urinary and fecal incontinence, POP, sensory and emptying abnormal-ities of the lower urinary tract, defecatory dysfunction, sexual dysfunction and chronic pain syndromes. The di V erent symptoms can exist alone, but in many cases a person has more than one symptom, and it has been pro-posed that the symptoms are linked together and caused by dysfunction of the ligaments, fascias and the pelvic X oor muscles (PFM) [3]. DeLancey et al. [4] described an integrated life span model and classi W ed pelvic X oor func-tion in 3 major life phases: (1) Development of functional reserve, (2) Variations in amount of injury and recovery during and after vaginal birth and (3) Deterioration that occurs with advancing age.According to Ashton-Miller and DeLancey [5], the ana-tomical structures that prevent incontinence and genital organ prolapse in females include sphincteric and support-ive systems. The PFM are regular skeletal muscles and con-sist of several muscles and muscle layers of the pelvic and urogenital diaphragms. During voluntary contraction of the PFM, there is a forward and upward lift and a squeeze constricting the levator hiatus with the pelvic openings [5]. Since Kegel W rst described PFM training to be e V ective for UI [6, 7], it has been the core of physical therapyK. Bø (&)Department of Sports Medicine,Norwegian School of Sport Sciences,PO Box 4014, Ullevål Stadion, 0806 Oslo, Norway e-mail: kari.bo@nih.nointerventions for pelvic X oor dysfunction in both male and female populations.The physical therapy process includes assessment, diag-nosis, planning, intervention and evaluation [8]. It has been found that more than 30% of women with pelvic X oor dis-orders may be unable to contract the PFM at their W rst con-sultation. Hence, individual instruction and feedback of the attempt to contract is important [9]. Physical therapy treat-ments for the pelvic X oor may include bladder training, PFM training with or without biofeedback, cones, electr-ostimulation or other adjuncts to training. The actual train-ing can be done individually or in groups [10, 11].The aim of this review is to address evidence for PFM training for female stress urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse and sexual dysfunction based on randomized con-trolled trials and systematic reviews.MethodsThis review is based on RCT and systematic reviews pub-lished from 2001 to 2011. The systematic reviews are Cochrane reviews on pelvic X oor muscle training [12–14], the NICE guidelines [15], the systematic reviews of Hay-Smith et al. from the 4th International Consensus on Incon-tinence 2009 [11] and the Health Technology Assessment [16]. A new search was retrieved on Pubmed on August 18th 2011, using the combination of pelvic X oor exercise (or pelvic X oor muscle training) and stress urinary inconti-nence (or pelvic organ prolapse or sexual dysfunction). Limits were English language, female and RCT. Due to limitations in number of references, references to many of the RCTs of PFM training for SUI/MUI are to be published systematic reviews rather than the original publication. ResultsStress urinary incontinenceIn 1948, Kegel [6, 7] was the W rst to report PFMT to be e V ective in treatment of female urinary incontinence (UI). In spite of his reports of cure rates of >84%, surgery soon became the W rst choice of treatment and not until the 1980s was there renewed interest for conservative treatment [4]. Since then, several RCTs have demonstrated that PFMT is more e V ective than no treatment to treat SUI [11, 16–18]. In addition, a number of RCTs have compared PFMT alone with either the use of vaginal resistance devices, biofeed-back or vaginal cones [11, 13]. Out of the RCTs on SUI, only one did not show any signi W cant e V ect of PFMT on UI [13]. In this study, there was no check of the women’s abil-ity to contract, adherence to the training protocol was poor and the placebo group contracted gluteal muscles and external rotators of the hips; activities that may give co-contractions of the PFM [10].It is often reported that PFMT is more commonly associ-ated with improvement of symptoms, rather than a total cure. However, short-term cure rates of 35–80%, de W ned as ·2 grams of leakage on di V erent pad tests, have been found after PFMT for SUI [18, 19]. The highest cure rates were shown in RCTs of high methodological quality [10, 15]. The participants had thorough individual instruction by a trained PT, combined training with biofeedback or electri-cal stimulation, and had close follow-up once or every sec-ond week. Adherence was high and dropout was low.BiofeedbackBiofeedback has been de W ned as “a group of experimental procedures where an external sensor is used to give an indi-cation on bodily processes, usually in the purpose of chang-ing the measured quality” [10]. Today, a variety of biofeedback apparatus are commonly used in clinical prac-tice to assist with PFM training. The apparatuses are based on either pressure measurements or surface EMG.Since Kegel W rst presented his results, several RCTs have shown that PFM training without biofeedback is more e V ective than no treatment for SUI [11, 15]. In women with stress or mixed incontinence, all but two RCTs have failed to show any additional e V ect of adding biofeedback to the training protocol for SUI. Berghmans et al. [10] demon-strated a quicker progress in the biofeedback group. In the study of Glavind et al. [20], a positive e V ect was demon-strated. However, this study was confounded by a di V er-ence in training frequency, and the e V ect might be due to a double training dosage, the use of biofeedback, or both. Vaginal conesVaginal cones are weights that are put into the vagina above the levator plate. The cones were developed by Plevnik [10] in 1985. The theory behind the use of cones in strength training is that the PFM are contracted re X exively or voluntary when the cone is perceived to slip out.A Cochrane review, combining studies including patients with both SUI and mixed incontinence, concluded that training with vaginal cones is more e V ective than no treat-ment [14]. Bø et al. [10] found that PFMT was signi W cantly more e V ective than training with cones both to improve muscle strength and reduce urinary leakage. In other stud-ies, there were no di V erences between PFMT with and without cones [10, 14]. Cammu and Van Nylen [10, 14] reported very low compliance and therefore did not recom-mend use of cones. Also in the study of Bø et al. [10, 14], women in the cone group had motivational problems.Laycock et al. [10, 14] had a total dropout rate in their study of 33%.Adverse e V ects of PFM trainingFew, if any, adverse e V ects have been found after PFMT [10, 11, 15–18]. Lagro-Jansson et al. [10, 11] found that one woman reported pain with exercise and three had an uncomfortable feeling during the exercises. Aukee et al. [10, 11] reported no side e V ects in the training group but found that two women interrupted the use of home biofeed-back apparatus because they found the vaginal probe uncomfortable. These women were both postmenopausal. In other studies, no side e V ects have been found [11].Long-term e V ect of PFM training for SUISeveral studies have reported long-term e V ect of PFMT [10, 11, 16]. However, the results are di Y cult to interpret because usually women in the nontreatment or less e V ec-tive intervention groups have gone on to retrieve treat-ment after cessation of the study period. As for surgery, there are only few long-term studies including clinical examination [10]. Klarskov et al. [10] assessed only some of the women originally participating in the study. Lagro-Janssen et al. [10] evaluated 88 out of 110 women with SUI, urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) or mixed uri-nary incontinence (MUI) 5years after cessation of train-ing and found that 67% remained satis W ed with the condition. Only seven of 110 had been treated with sur-gery. Satisfaction was closely related to adherence to training and type of incontinence, with mixed incontinent women being more likely to lose the e V ect. SUI women had the best long-term e V ect.In a 5year follow-up, Bø and Talseth [10] examined only the intensive exercise group and found that urinary leakage was signi W cantly increased after cessation of orga-nized training. Three of 23 had been treated with surgery. Fifty-six % of the women had a positive closure pressure during cough and 70% had no visible leakage during cough at W ve-year follow-up. Seventy % of the patients were still satis W ed with the results and did not want other treatment options.Cammu et al. [10] used a postal questionnaire and medi-cal W les to evaluate long-term e V ect of 52 women who had participated in an individual course of PFMT for urody-namic SUI. Eighty-seven % were suitable for analysis. Thirty-three % had had surgery after 10years. However, only 8% had undergone surgery in the group originally being successful after training, whereas 62% had under-gone surgery in the group initially dissatis W ed with training. Successful results were maintained after 10years in 2/3 of the patients originally classi W ed as successful.Bø et al. [21] reported current status of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) from questionnaire data 15years after cessation of organized training. They found that the short-term signi W cant e V ect of intensive training was no longer present at follow-up. Fifty % from both groups had interval surgery for SUI, however more women in the less-intensive training group had surgery within the W rst 5years after ending the training program. There were no di V er-ences in reported frequency or amount of leakage between non-operated or operated women, and women who had sur-gery reported signi W cantly more severe leakage and to be more bother by urinary incontinence during daily activities than those not operated.Pelvic organ prolapseWhile systematic reviews and RCTs have shown convinc-ing e V ect of PFMT for SUI and MUI [11, 12], the research on PFM training to treat POP is rather new. A survey of UK Women’s Health physical therapists showed that 92% of the physical therapists assessed and treated women with POP [22]. The most commonly used treatment was PFM training with and without biofeedback. A Cochrane review on PFM training for POP concluded that there was an urgent need for guidance regarding the e V ectiveness of PFMT [23].Till date W ve RCTs have assessed PFM training to treat POP or POP symptoms. The RCTs are all in favor of PFM training, demonstrating statistically signi W cant improve-ment in symptoms [24–26] and/or prolapse stage [24, 25, 27, 28]. The only full-scale RCT showed a 19% improve-ment in prolapse stage measured by POP-Q, compared to 4% in the control group receiving lifestyle advice only [24].Sexual dysfunctionAccording to Graziottin [29], female sexuality is complex and rooted in biological, psychosexual and context-related factors and correlated to couple dynamics and family and sociocultural issues. Female sexual disorder is classi W ed as women’s sexual interest/desire disorder, sexual aversion disorder, subjective sexual arousal disorder, combined gen-ital and subjective arousal disorder, persistent sexual arousal disorder, women’s orgasmatic disorder, dyspareu-nia and vaginismus.To date, there are only a limited number of RCTs evalu-ating the e V ect of PFM training on sexual function in women. Three RCTs have been found reporting the e V ect of PFM training on sexual function in the postpartum period. Wilson and Herbison [30] did not W nd any signi W-cant di V erences between the exercise group and the control group in sexual satisfaction. However, 52 and 22% dropped out of the exercise and control group, respectively, theparticipants had only 4 follow-up visits with a physical therapist and there was no e V ect of the training on PFM strength. Mørkved et al. [31] asked women about sexual satisfaction 6years after cessation of an 8weeks postpar-tum PFM training program. They found that 36% in the former training group compared to 18% in the control group reported improved satisfaction with sex after deliv-ery (P<0.01). Citak et al. [32] conducted a single blind RCT on 118 primiparous women at 4months postpartum. The training period lasted for 12weeks and started with individual vaginal assessment to ensure correct contrac-tions. The results showed a signi W cant increase in PFM strength in the exercise group only, and the exercise group scored signi W cantly higher on sexual arousal, lubrication and orgasm, but not on satisfaction.In a RCT, Bø et al. [33] investigated the e V ect of PFM training on sexual function in a group of SUI women, mean age 50years, and found that the exercise group was signi W-cantly better o V in questions on sex life in X uenced by uri-nary symptoms and UI during intercourse.DiscussionThere is consensus that PFM training has Level 1, grade A evidence to be e V ective in treatment of SUI and MUI [11, 14–18]. There is growing evidence for e V ect on POP and one study has also shown changes in pelvic X oor morphol-ogy pointing toward a possible e V ect at the pathophysiolog-ical level. To date, the evidence for PFM training on sexual dysfunction is sparse.Stress urinary incontinenceThere are two main theories of mechanisms on how PFMT may be e V ective in prevention and treatment of SUI [34]: (1) Women learn to consciously contract before and during increase in abdominal pressure and continue to perform such contractions as a behavior modi W cation to prevent descent of the pelvic X oor and stop leakage from occurring and (2) Women are taught to perform regular strength training over time in order to build up “sti V ness” and structural support of the pelvic X oor. There is basic research, case–control studies and RCTs to support both these hypotheses [34, 35].In addition to these main theories, two other theories have been proposed: Sapsford [36] claimed that the PFM was e V ectively trained indirectly by contraction of the internal abdominal muscles, especially the transversus abdominal (TrA) muscle. There are no RCTs supporting this theory [37]. However, one RCT showed no additional e V ect of adding TrA training to a PFMT program [38]. Another concept is “Functional training of the PFM”. This means that women are asked to conduct a PFM contraction during di V erent tasks of daily living [39]. There are no RCTs to support this theory [37].Because of use of di V erent outcome measures and instru-ments to measure PFM function and strength, it is impossi-ble to combine results between studies and it is di Y cult to conclude which training regimen is the more e V ective. Also the exercise dosage (type of exercise, frequency, duration and intensity) varies signi W cantly between studies [10, 11]. Length of the intervention varied between 6weeks and 6months, holding time varied between 3 and 40s and num-ber of repetitions per day between 36 and >200 [13].Bø et al. [10] showed that instructor followed up training is signi W cantly more e V ective than home exercise. This study was the W rst demonstrating that a huge di V erence in outcome can be expected according to the intensity and fol-low-up of the training program, and that very little e V ect can be expected after training without close follow-up. It is worth notifying that the signi W cantly less e V ective group in this study had 7 visits with a skilled PT, and that adherence to the home training program was high. Nevertheless, the e V ect was only 17%. To date, more intensive training has also shown to be more e V ective in other RCTs and system-atic reviews [10, 11, 15–17]. There is a dose–response issue in all sorts of training regimens [10, 40]. Hence, one reason for disappointing e V ects shown in some clinical practises or clinical trials may be due to insu Y cient training stimulus and low dosage.In some textbooks, the term “biofeedback” is often used to classify a method di V erent from PFMT. However, bio-feedback is not a treatment by its own, but an adjunct to training, measuring the response from a single PFM con-traction. In the area of PFMT, both vaginal and anal surface EMG, and urethral and vaginal squeeze pressure measure-ments have been utilized in purpose of making the patients more aware of muscle function, and to enhance and moti-vate patients’ e V ort during training [10]. However, errone-ous attempts of PFM contractions e.g., straining may be registered by both manometers and dynamometers, and contractions of other muscles than the PFM may a V ect sur-face EMG activity. Hence, EMG, manometers and dyna-mometers cannot be used to register a correct contraction.Very few of the studies comparing PFMT with and with-out biofeedback have used the exact same training dosage in the two randomized intervention groups. When the two groups under comparison receive di V erent dosage of train-ing in addition to biofeedback, it is impossible to conclude what is causing a possible e V ect. Moreover, since PFMT is e V ective without biofeedback, a large sample size may be needed to show any bene W cial e V ect of adding biofeedback to an e V ective training protocol. In most of the published studies comparing PFMT with and without biofeedback, the sample sizes are small, and type II error may have been the reason for negative W ndings [11].Any factor that may stimulate to high adherence and intensive training should be recommended in purpose of enhancing the e V ect of a training program. Hence, when available, biofeedback should be given as an option for home training, and the physical therapist should use any sensitive, reliable and valid tool to measure the contraction force at o Y ce follow-up.The use of cones can be questioned from an exercise sci-ence perspective. To hold the cone for as long as 15–20min may cause decreased blood supply, decreased oxygen con-sumption, muscle fatigue and pain. In addition, it may recruit contraction of other muscles instead of the PFM. Moreover, many women report that they dislike using cones [10]. Arvonen et al. [10, 14] used “vaginal balls” and followed general strength training principles. They found that training with the balls was signi W cantly more e V ective in reducing urinary leakage than regular PFMT.The general recommendations for maintaining muscle strength are 1 set of 8–12 contractions twice a week [40]. The intensity of the contraction seems to be more important than frequency of training. So far, no studies have evalu-ated how many contractions subjects have to perform to maintain PFM strength after cessation of organized train-ing. In a study of Bø and Talseth [10], PFM strength was maintained 5years after cessation of organized training with 70% exercising more than once a week. However, number and intensity of exercises varied considerably between successful women. In the study of Cammu et al.[10], the long-term e V ect of PFMT appeared to be attrib-uted to the pre-contraction before sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressure, and not so much to regular strength training. Using pre-contractions have been found not to increase muscle strength in a recent published RCT [35].Pelvic organ prolapseThe same two hypotheses proposed for treatment of SUI also apply for prevention and treatment of POP [34]. Research on basic and functional anatomy supports con-scious contraction of the PFM as an e V ective maneuver to stabilize the pelvic X oor [34]. However, to date, there are no studies on how much strength or what neuromotor con-trol strategies are necessary to prevent descent during cough and other physical exertions, nor how to prevent gradual descent due to activities of daily living or over time.The theoretical rationale for intensive strength training of the PFM to treat POP is the same as for SUI. As described by DeLancey [41] in the “boat in dry dock” the-ory, the connective tissue support of the pelvic organs fails if the PFM relax or are damaged, and organ descent occurs. This underpins the concept of elevation of the PFM and closure of the levator hiatus as important elements in con-servative management of POP. Till date, Brækken et al.[24] found a signi W cant and huge increase in strength in the PFMT group only. They also found statistically signi W cant increases in muscle volume, shortening of the muscle length, constriction of the levator hiatus, and lifting of the bladder neck and rectal ampulla [35], factors that may be essential in prevention and reversion of POP.Use of POP-Q as a measure of improvement after PFM training can be questioned. During the POP-Q, the investi-gator tries to make the women strain as much as possible, a manouver that should be discouraged and by itself is a risk factor for developing prolapse. Measurement of the resting position of the organs before and after PFM training may be a much better way of measuring improvement. A lift of the organs to a higher resting position of approximately 0.5cm was found in the study by Brækken et al. [35]. Given the strong e V ect on POP symptoms in the same study [24], we suggest this to be the recommended e V ect measure for future studies.All RCTs on PFM training on POP are in favor of PFM training. To date, there is only one full-scale RCT evaluat-ing both stage of prolapse and symptoms [24]. This exam-iner-blinded trial found signi W cant improvement in a group of women with stage I, II, and III POP receiving supervised PFMT compared to a group receiving advice not to strain while defecating, in addition to encouragement to pre-contract the PFM before an increase in intra-abdominal pressure.The published studies on POP reported short-term e V ects. To maintain the e V ect, it is expected that PFM train-ing must be continued, although to a lesser degree, to avoid relapse [42].Sexual dysfunctionFrom the understanding of the complexity of these disor-ders and the numerous di V erent conditions with complex causality, one could argue that it is unlikely that PFM func-tion or PFM training alone could in X uence all sexual disor-ders, and one could also question the theoretical framework for how it could in X uence the di V erent aspects of female sexuality. In general, physical therapy has been recom-mended for sexual disorders when clinical assessment of the pelvic X oor has demonstrated either “overactive”(hypertone) muscles or weak PFM [29]. However, to date there are limited evidence for the association between PFM dysfunction and sexual disorders.In a comparison study of 32 women who delivered vagi-nally, 21 women who underwent cesarean section and 15 nulliparous women, Baytur et al. [43] found that PFM strength was signi W cantly lower in women delivering vagi-nally. Nevertheless, there was no di V erence between the groups regarding sexual function and no correlationbetween sexual function and PFM strength. Schimpf et al.[44] assessed 505 women with POP-Q and the female sex-ual function index (FSFI). The results showed that there was no association between vaginal size and sexual activ-ity. Contradictory to this, Lowenstein et al. [45] found that among 166 women, women with strong or moderate PFM scored signi W cantly higher on the FSFI orgasmatic and arousal domains than women with weak PFM. Ability to hold the PFM contraction was also correlated with orgas-matic and arousal domains.To date there are only few studies on the in X uence of PFM function on female sexuality and the e V ect of PFM training on sexual function. A few RCTs with supervised training show some promising results. However, it is not yet possible to make clinical recommendations. There is an immediate need for further high quality research in this important area of women’s health.ConclusionPFM training has support from several high quality RCTs and systematic reviews for SUI and MUI, and W ve RCTs show favorable results for PFM training to treat POP. PFM training has no known serious adverse e V ects and should therefore be o V ered as W rst line treatment for these conditions. There is some data from RCTs supporting an e V ect also on sexual function. However, more research is needed on PFMT and sexual disorders in addition to pre-vention studies. It is unlikely that weak interventions without supervision will be e V ective. Hence, low cost interventions with non-supervised training can be costly in the long term, as they most likely do not provide a worthwhile e V ect size.Con X ict of interest The author declares that she has no con X ict of interest.References1.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL (1997)Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 89:501–5062.Bump RC, Norton PA (1998) Epidemiology and natural history ofpelvic X oor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clinics North Am 25:723–7463.Wall L, DeLancey JO (1991) The politics of prolapse: a revisionistapproach to disorders of the pelvic X oor in women. Perspect Biol Med 34:486–4964.DeLancey JO, Low LK, Miller JM, Patel DA, Tumbarello JA(2008) Graphic integration of causal factors of pelvic X oor disor-ders: an integrated life span model. Am J Obstet Gynecol 199:610.e1–610.e55.Ashton-Miller J, DeLancey JO (2007) Functional anatomy of thefemale pelvic X oor. Ann NY Acad Sci 1101:266–2966.Kegel AH (1948) Progressive resistance exercise in the functionalrestoration of the perineal muscles. Am J Obstet Gynecol 56:238–2497.Kegel AH (1952) Stress incontinence and genital relaxation. CibaClinical Symp 2:35–518.Bø K (2007) Overview of physical therapy for pelvic X oor dys-function. In: Bø K, Berghmans B, Mørkved S, van Kampen M (eds) Evidence based physical therapy for the pelvic X oor: bridg-ing science and clinical practice. Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, pp1–89.Bø K, Mørkved S (2007) Motor learning. In: Bø K, Berghmans B,Mørkved S, van Kampen M (eds) Evidence based physical therapy for the pelvic X oor: bridging science and clinical practice. Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, pp113–11910.Bø K Pelvic X oor muscle training for stress urinary incontinence.In: Bø K, Berghmans B, Mørkved S, van Kampen M (eds) Evi-dence based physical therapy for the pelvic X oor: bridging science and clinical practice. Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, pp171–187 11.Hay Smith J, Berghmans B, Burgio K, et al (2009) Adult conser-vative management: Committee 12. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A (eds) Incontinence: 4th international consulta-tion on incontinence, 4th edn. Health Publication Ltd, pp1025–110812.Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith J (2010) Pelvic X oor muscle training ver-sus no treatment for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20:CD00565413.Hay-Smith EJ, Bø K, Berghmans LC et al (2001) Pelvic X oor mus-cle training fur urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Data-base Syst Rev Issue 1:CD00140714.Herbison GP, Dean N (2002) Weigthed vaginal cones for urinaryincontinence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Issue 1:CD002114 15.Welsh A (2006) Urinary incontinence—the management of uri-nary incontinence in women. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). RCOG Press. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, London16.Imamura M, Abrams P, Bain C et al (2010) Systematic review andeconomic modelling of the e V ectiveness of non-surgical treat-ments for women with stress urinary incontinence. Health Technol Assess 14:1–118, iii–iv17.Hay-Smith EJC, Dumoulin C (2006) Pelvic X oor muscle trainingversus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 25: CD00565418.Bø K (2002) Is there still a place for physiotherapy in the treatmentof female incontinence? EAU Update Ser 1:145–15219.Felicissimo MF, Carneiro MM, Saleme CS, Pinto RZ, da FonsecaAMRM, da Siva-Filho AL (2010) Intensive supervised versus unsupervised pelvic X oor muscle training for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized comparative study. Int Urogynecol J 21:835–84020.Glavind K, Nøhr SB, Walter S (1996) Biofeedback and physio-therapy versus physiotherapy alone in the treatment of genuine stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dys-funct 7:339–34321.Bø K, Kvarstein B, Nygaard I (2005) Lower urinary tract symp-toms and pelvic X oor muscle exercise adherence after 15years.Obstet Gynecol 105:999–100522.Hagen S, Stark D, Cattermole D (2004) A United Kingdom-widesurvey of physiotherapy practice in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Physiotherapy 90:19–2623.Hagen S, Stark D, Maher C, Adams E (2006) Conservative man-agement of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD00388224.Brækken IH, Majida M, Ellstrom-Engh M, Bø K (2010) Can pel-vic X oor muscle training reverse pelvic organ prolapse and reduce。

建筑学报70旧建筑改建 REBUILD ING OF OLD B UILDING概述1933老场坊改造项目,是将一个废弃的工业遗产盘活,并改造成为时尚中心。

此类改造项目多被称为“创意产业”,就是改造城市中遗留下来的、目前已经不再生产的工业建筑,它们大都位于城市中心,但是由于功能不能与其位置相匹配,产权关系较为复杂,所以长时间被空置,逐渐变成城市的死角。

为了改变这样的状况,政府采用了长期租用的办法,配合三个不变的政策(土地性质不变、产权不变、建筑规模不变),允许投资公司进行改造,1933项目就是在这样的背景下得以改造建设的。

1933老场坊位于上海市中心的砂径路,包含5栋楼,其中1号楼为原工部局宰牲场、2号楼为宰牲场的化制间、3号楼为宰牲场的狗棚间,以上楼宇均建成于1933-1934年间;4号楼为1966年建筑的食堂和仓库,5号楼为解放初建筑的锅炉房。

本文着重介绍1号楼和4号楼的改造设计。

1号楼—原上海工部局宰牲场建于1933年的1号楼是当时远东最大的、最为现代化的屠宰场,是上海第4批历史文化保护建筑。

建筑主体由东、南、西、北高低不一的钢筋混凝土结构围合成方楼,正中是一座24边形的圆楼,方、圆楼之间通过26座廊桥连接,各层上下交错,貌若迷宫。

结构采用了当时非常先进的“伞形柱无梁楼盖”,由伞型柱帽构成的内部空间具有强烈的视觉冲击力。

该建筑是功能主义的工业建筑,可被视为是根据宰牲工艺设计的钢筋混凝土的机器(图1)。

我认为当时的设计师并非想创造一个非凡的建筑,但恰恰是这些工艺元素产生了一个伟大的空间。

连接室内外的那些斜坡和桥梁是工艺流程的一部分,当时是供大型动物行走用的,非常有机的将不同楼层连接起来,是构成空间最重要的组成部分。

这里被废弃后曾成为都市探险者的乐园和摄影师创作的基地,而今它将通过注入创意产业的新功能使其更新为具有地标性的顶级消费品交易中心。

采用创意产业的经营方式,对原有历史建筑进行经营性保护,以盘活历史建筑,在新的历史时期焕发出时尚的活力。