第三章 证据法学的理论基础

- 格式:ppt

- 大小:692.00 KB

- 文档页数:24

证据法学课件(封利强)证据法学讲义第一章证据法学概述1.证据法学的概念:是研究关于证据的法律规范和诉讼或非诉讼法律事务处理过程中运用证据认定案件事实或其他法律事实的规律、方法和规则的学科,是现代法学体系中的一个组成部分2.证据法学的分类:广义证据法学、狭义证据法学狭义证据法学:又称诉讼证据法学,是专门研究诉讼法律中有关证据的规定和诉讼过程中运用证据实践的学科。

广义证据法学:除研究诉讼证据外,还研究在处理其他法律事务,如行政执法、仲裁、公证、监察等活动中如何运用证据的问题,有人也称之为法律证据学。

证据法学学科的称谓之争:证据学与证据法学、证据科学、大证据学、证明法学。

3.证据法学的研究对象(1)与证据和证据运用有关的法律规范(2)与证据和证据运用有关的司法实践(3)诉讼证明的方法、规律和规则(4)古今中外的证据制度和证据理论4. 证据法的立法体系1.英美法系证据法的立法体系2.大陆法系证据法的立法体系3.我国现行的立法体系以及学界的不同主张我国目前存在多个层面的证据制度:法律层面、司法解释层面、部门规章层面、国际条约层面、地方性规定层面。

学界的主张主要包括:维持现状说、统一立法说与分别立法说等。

第二章证据制度的历史沿革第一节神示证据制度一、神示证据制度的概念概念:是证据制度发展史上最原始的一种证据制度,即它是凭借神的各种启示来判断案件是非曲直的一种证据制度。

存在时间:神示证据制度曾普遍存在于亚欧各国的奴隶社会,甚至在欧洲封建社会早期还保留有神示证据制度的残余。

产生基础:人们对神灵的信仰和崇拜。

二、神示证据制度的证明方法(一)对神宣誓《汉穆拉比法典》第131条规定:“倘自由民之妻被其夫发誓诬陷,而她并未被破获有与其他男人同寝之事,则她应对神宣誓,并得回其家。

(二)水审分类:冷水审、沸水审两种方式《汉穆拉比法典》第2条规定:“设若某人控他人行妖术,而又不能证实此事,则被控行妖术的人应走近河边,投入河中。

证据法学理论基础之我见证据法学的理论基础,就是作为证据法制、收集证据以及证明等活动以及证据法学研究的理论支持和指导力量。

对于证据立法和证据法实践活动提供支持和指导的理论是多样化的,我们在谈到证据法学的理论基础的时候,只能择其要者进行阐述,不可能将证据法的理论支持和指导力量一一列举出来,这是我们在谈证据法学的理论基础必须首先明确的。

我认为,证据法学的理论基础主要包括认识论和价值论两大部分,作为我国证据法学理论基础的,当以认识论和法律多元价值及平衡、选择理论为首选。

一、理论基础之一:认识论诉讼活动的主要构成部分是认识活动,对于认识活动,认识论无疑具有理论支持和指导作用。

认识论(epistemology)是哲学的一部分,是“”关于人类知识的来源、发展过程,以及认识与实践关系的学说。

“”它的任务是研究人类认识的起源与发展,并考察组织异常复杂的认识作用。

其基本问题包括认识的起源问题、认识的确实性问题和认识的本质问题。

对于认识的起源问题,主要有三派:唯理主义(rationalism)者认为认识乃是先天固有的,其起源在于思考;经验主义(empiricism)者认为认识起源于内外之经验;批评主义(criticism)调和于两说之间,批评主义者认为先天和经验同为知识的源泉。

对于认识的确实性问题。

主要有以下几种流派:其一,为独断论(dogmatism),独断论者是不加验证而独断其真实的观念,信奉者完全信赖感觉与知识的结果,认为世界的事实情况与我们所见的和所想的完全一致。

例如,宗教是独断的,宗教活动人士坚信其所持教义的真确性,即使是超感觉的不可能的经验的对象,也深信不已;哲学上也有一个相当长的时期是独断的,例如柏拉图认为世界的本质是由非物质的观念或者原型组织而成的,等等。

其二,为怀疑论(skepticism),怀疑论者与独断论者相反,极端怀疑认识的可能性,因而不作一切积极的主张。

怀疑论起源于公元前三百年的比罗(Pyrrho),当时哲学家所持的见解彼此矛盾,莫衷一是,因此诱发了怀疑论的产生。

《证据法学》教学大纲(本科)一、课程的性质、目的与任务证据法学是关于证据的法律规范和运用证据认定案件事实的规律、方法和规则的学科,它是一门思想性及实践性都很强的应用法学,以证据立法和司法实践为研究对象的科学。

证据法学是法学专业本科生选修课之一,是现代法学体系中的一个重要组成部分。

学习证据法学,目的与任务在于通过本课程的学习,使学生详细掌握证据法学的基本概念、基本内容以及基本原理,分析研究证据法律制度的本质和规律,着重培养学生运用证据查明案件事实的基本技能,提高运用证据分析、认定案件事实的能力。

二、课程的教学内容和基本要求:第一章证据制度内容:证据制度概述;证据制度的历史沿革;我国证据制度的历史沿革。

要求:(1)了解我国证据制度的历史沿革;(2)掌握证据制度的主要历史类型;本章重点和难点:神示证据制度、法定证据制度与自由心证证据制度的主要特征。

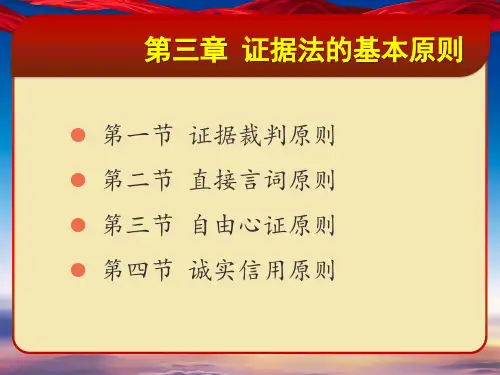

第二章证据法的理论基础内容:证据法的理论基础:认识论;方法论;价值论要求:(1)了解认识论对证据法的指导意义(2)了解方法论对证据法的指导意义(3)了解价值论对证据法的指导意义第三章证据法的基本原则内容: 守法制原则;实事求是原则;公平诚信原则;法定证明与自由证明相结合原则; 证据为本原则;直接言词原则要求:(1)了解遵守法制原则;实事求是原则;公平诚信原则;法定证明与自由证明相结合原则(2)掌握证据为本原则;直接言词原则第四章证据概念与证据资格内容:证据的真实观;证据的定义;证据的资格。

要求:(1)掌握证据的定义和资格;(2)了解证据的真实观。

本章重点和难点:证据的定义、资格。

第五章证据的学理分类内容:言词证据与实物证据;原始证据与派生证据;直接证据与间接证据;本证与反证要求:(1)了解证据分类的概念及意义;掌握言词证据与实物证据、原始证据与传来证据、直接证据与间接证据、本证与反证的概念及特征。

本章重点和难点:言词证据与实物证据;原始证据与传来证据;直接证据与间接证据;本证与反证的概念及特征。

证据法学的理论基础近年来证据法学研究热闹起来,这种热闹,与前几年较为沉寂的局面形成了强烈的对比,值得被称为一件令人欣慰的事,因为证据法学本来不但是技术性很强的学科,而且对于个人自由等个人价值的保障来说也颇为重要,这是毋庸赘述的。

不过,学术研究上忽冷忽热的局面,也可能会让人萌生一点隐忧,它多少会让人联想起这些年来我们身上反映出来的热情有余而思虑不足的学术研究习惯。

现在学者们将更多精力投注于证据法学研究,与证据法有关的论著也多起来,见解难免不一致。

对证据法的有关问题认真探讨、热情争论甚至直率批评,总归是有益于士林的。

能够如此,证据法学研究中出现的这场热闹才不致流为一场泡沫。

最近拜读了陈瑞华教授发表在《法学》(20XX年第1期)上的《从认识论到价值论——证据法学理论基础的反思与重构》一文(以下简称“”陈文“”),阅读过程中能够时时感觉到作者刻意求新的精神,不过,掩卷静思,觉得文中也不乏可推敲之处,其中若干主要观点,颇有详加探讨的必要,故而特撰此文,以求教于著者并借以达到澄清某些认识之目的。

诉讼活动与认识活动陈文提出:中国主流的诉讼理论将刑事诉讼、民事诉讼和行政诉讼都视为一种认识活动,这种认识活动的最终目标在于运用证据,查明案件事实的客观真相,从而为正确适用刑法、民法、行政法等实体法律规范奠定基础。

有关运用证据的活动作为重要的诉讼活动,是这种认识活动的重要环节。

由于这一原因,这一理论将辩证唯物主义认识论视为诉讼制度的重要指导思想之一,视为证据制度的重要理论基础。

陈文进而指出:尽管围绕证据的运用所进行的证明活动包含着认识过程,“”但绝不仅仅等同于认识活动“”,“”这种认识活动在诉讼中都不具有根本的决定性意义“”,理由是:首先,诉讼和仲裁都是以解决利益争端和纠纷为目的的活动,“”在解决争端的过程中,裁判者固然会通过审查控辩双方提供或者自行收集的证据材料,对案件的事实真相作出明确的揭示,但这种对事实的揭示只是为了争端的解决,提供一定的事实基础和依据,创造一定的条件,而不是诉讼的最终目的。

·证据法讲堂·The Theoretical Foundations and Implications of EvidenceRonald J.Allen“Evidence”and“evidence law”are two quite distinct concepts.“Evidence”generally refers to those inputs to decision making that influence its outcome in what,to introduce a third concept,is normally re-ferred to as a rational manner.In the United States,“evidence”also has a technical legal meaning to re-fer to the testimony and exhibits introduced at trial,but this is problematic.In the United States,fact finders may take into account their observations of witnesses(“demeanor”),which obviously is“evidence”in any useful sense of the term,and more deeply no observation may be processed and deliberated upon without the use of a vast storehouse of preexisting concepts,observations,and decision makings tools(such as logic,abduction,utilities,and so on).A useful concept of evidence must thus expand considerably far beyond the mere“trial inputs”–the observations of witness testimony and exhibits.What“rational”means here is putting all of the inputs and cognitive capabilities to the use of discovering as best can be done the way the world was at some prior time,and then to let rights and obligations be determined con-sistently with the preexisting state of affairs.“Evidence law”,by contrast,refers to the manner in which the evidentiary process is organized,but obviously the organization of the evidentiary process is contingent on both“evidence”and the nature of “rationality.”The domain of evidence law,then,extends to the traces of the past that we colloquially refer to as“evidence,”the manner in which such traces of the past are processed and relied upon in human decision making,and the regulation by law of the formal evidentiary process.Evidence law is thus contin-gent upon,and must accommodate,at least three things:Universal truths of the human condition,contin-gent aspects of the nature of government and its legal system,and highly specific policies to be pursued in addition or opposition to the pursuit of truth.I will say a word about each of these in turn.Universal Truths:Although much of human culture is socially determined,cognitive capacities are not.How capacities are developed and employed may differ,but the underlying epistemological capacities to perceive,process,remember,and relate what was observed are part of the human condition.Obviously, they differ over individuals within societies,but they are universally present in all competent adults.Many of the tools that humans employ to assist in understanding their environment likewise are universal.Math-ematics and logic do not vary from place to place,nor do decision tools such as utility functions and costJohn Henry Wigmore Professor of Law,Northwestern University President,Board of Foreign Advisors,Evidence Law and Forensic Sciences Institute Fellow,Procedural Law Research Center,CUPL Beijing,China June,2010curves.Together,I will refer to these epistemological capacities and formal tools as the“tools of rationali-ty.”These tools of rationality are what permit humans to understand and control their environment.They include such things as simple deductive reasoning,the capacity to generalize,abductive reasoning(the search for the explanation of a series of data points),an understanding of cause and effect and of necessary and sufficient conditions,and many other things as well.These issues comprise the study of epistemolo-gy—the study of knowledge—and the law of evidence is in fact the law’s epistemology.I should note that in some discussions of the foundations of the law of evidence a distinction is made between probability theory and epistemology.That may be a useful distinction for some purposes,but in my opinion probabili-ty theory is just one of the tools of rationality that facilitate pursuing epistemic tasks.There surely are cultural and social influences operating on the basic tools of rationality,and at all levels.Two individuals from different cultures may experience the same perceptual event but understand it completely differently based on their respective familiarity with the type of event in question and their background knowledge.Similarly,the assumptions that begin logical processes may differ,and both the sets of costs and benefits and their relative weights may vary,as well.I am less sure that there is a universal human nature beyond the epistemological capacities,frankly, although many think that there is.There is much lose talk about a universal sense of justice and univer-sal human rights,but the twentieth century is a reproach to any who would see“human nature”as benefi-cent or concerned about the welfare of strangers.Perhaps,then,the economists are correct in a sense that people pursue,or should be conceived of as pursuing,their own self-interest,however those interests are conceived.Obviously,people do pursue their own financial and medical self-interest and those of their families.There certainly is a widespread desire for the conditions of a peaceful life with the possibility of human flourishing,but it is hard to see this as resting upon universals of the human condition.Not only is the twentieth century a reproach to such a view,so,too,is most of recorded history.And the twenty-first century is off to a start that suggests not much has changed from the millennium.As I will elaborate below,one of the primary tasks of the law of evidence is to process and digest this elaborate set of considerations and create in their light a system of dispute resolution that serves the inter-ests of the community.Contingencies of Government and its Legal System:Although there is much that is common to human-ity,the ways in which humans organize themselves varies almost infinitely.Legal systems are critical components of government,and they reflect the resolution of issues of deep political theory.One need look no further than China and the United States to see this clearly.Because of the political history of the United States,our founders concluded that political power should be diffused over the three branches of government,with each needing one or both of the others in order to be effective.This was designed to counteract what western observers almost universally believe is the centripetal force of all power centers and their tendency to aggrandizement.In brief,this is why we have a tradition of independent courts that we conceive of as being a potential brake on other branches of government.China has no such political theory of separation of powers.The central political tenet of Chinese communism is that all political power is possessed by the party,and any political organization is merely a means of efficiently and effectively pursuing the policies set by the party.There is no room here for an independent judiciary in the western sense.This difference is the cause of much of the lack of understanding between these two cultures,and is a good example of how the background knowledge a person possesses may color observations.Western eyes may see in Chinese courts a lack of the rule of law precisely because of the lack of a robustly independentjudiciary,whereas Chinese eyes may see in the western legal systems needless bureaucracy that is obstruc-tive of the social good.And of course there are innumerable additional ways in which governments can be constructed. Whatever form of government is chosen,and more importantly whatever assumptions form its foundation, will obviously impact the nature of the legal system,which in turn will impact the way in which disputes are resolved and evidence is administered.Having said all that,there is one universal aspect of dispute resolution,and it is not what one might think.There is a misconception in the West that the fundamental political insight of the Enlightenment, and the strongest plank supporting modern western governments,has something to do with rights and obli-gations.Citations to Hobbes,Locke,and Rousseau are found in abundance in legal scholarship and under-score this point.While rights and obligations are important,the more fundamental insight of the Enlight-enment was the epistemological revolution that there is a world external to our mind that may be known objectively through evidence;however,citations to the epistemological work of Locke,Berkeley,Hume,or even Kant for this proposition,are few and far between.This reverses the actual relationship of facts and rights/obligations.Facts are prior to and determinative of rights and obligations.Without accurate fact finding,rights and obligations are meaningless.Consider the simple case of ownership of the clothes you are wearing.Your ownership of those clothes allows you the“right”to possess,consume,and dispose of those assets,but suppose I demand that you return“my”clothes.That is,I insist that the clothes that you are wearing actually be long to me.What will you do?You will search for a decision-maker to whom you will present evidence that you bought,made,found,or were given the clothes in question,and,if success-ful in this effort,the decision-maker will indeed grant you those rights and impose upon me reciprocal obligations.The critical point is that those rights and obligations are dependent upon what facts are found and are derivative of them.The significance of this point cannot be overstated.Tying the rule of law to true states of the real world anchors rights and obligations in things that can be known and are indepen-dent of whim and caprice.This is why the ideas of relevance and materiality are so fundamentally impor-tant to the construction of a legal system.They tie the legal system to the bedrock of factual accuracy.This point is truly universal.Neither rights or obligations,on the one hand,or policy choices on the other,can be pursued in the absence of knowledge of the actual,relevant states of affairs.Thus,even within the contingencies of ways of governing,we find a universal aspect of the law of evidence.Of course,how one might think that facts are most accurately or efficiently found,and what policies may off-set the significance of factual accuracy,are matters of reasonable disagreement.The Significance of Policy Issues:An enormous number of policy choices face the designer of a legal system.Some are consistent with the pursuit of factual accuracy,but many are in opposition to it.Note that I use the phrase“policy issues”to accompany all interests that society may pursue.It thus encom-passes what some might call“value theory.”However,not all the policies governments pursue are moral; many are quite practical and utilitarian.Indeed,maybe most policies governments pursue are practical and utilitarian.It is surely acceptable to make the distinction between moral and utilitarian policies,but they are parts of the larger category of interests governments pursue and can effectively be lumped together when thinking about the law of evidence.Another distinction that could be made,but that I do not make, is between the sources of policy issues.The source of some are just the standard questions that all govern-ments face everywhere,that involve the ordinary exercise of what we call,misleadingly,in the United States,the police power—the power of the State to regulate issues affecting health,safety,and welfare.By contrast,the source of others are explicit constitutional provisions,whatever the form a constitution maytake in any particular country.Some commentators sort out constitutional questions from other kinds of policy questions,which again is coherent.However,the distinction is not helpful to understanding the law of evidence,and thus I do not bother with making it.Evidence law does some things because of constitu-tional commitments,but at the highest level of generality that is no different than fashioning evidence law to pursue an interest that is not embedded in a constitutional document.I now turn to many of the policy issues that must be accommodated by the law of evidence.Pursuit of Factual Accuracy.One might reasonably suppose that natural reasoning processes based on innate epistemological capacities work reasonably well,and thus typically should be deferred to in the pursuit of factual accuracy.However,there may be recurring situations that lead people to error.In such a case,rules of evidence may attempt to correct for that systematic error.This explains FRE403's autho-rization to exclude evidence when it may be misleading or unfairly prejudicial.It also underlies other rules,such as limitations on character and propensity evidence,and the requirement that witnesses testify from firsthand knowledge.The circumstances under which individuals systematically make errors probably is heavily dependent on culture.The Value of Accuracy.Factual accuracy is surely the most significant desideratum,but it is by no means the only one.It has a cost,and the cost can sometimes be too high.A legal system overly preoccu-pied with factual accuracy may undermine the very social conditions that the legal system is trying to fos-ter.A dispute worth only a dollar that would take a thousand dollars to litigate to a factually accurate conclusion perhaps should not be litigated.Such litigation may very well reduce overall social welfare and discourage private settlement of disputes.Where the limit is reached is difficult to say,of course,and surely depends on local views.I will say much more about this in my second lecture.The Value of Incentives.Factual accuracy competes not just with cost but with other policies that a government reasonably may pursue.The list of such policies is long,and again culturally contingent.The law of privileges may foster and protect numerous relationships(spouses,legal,medical,spiritual,govern-mental,etc.).Litigation of an accident should not discourage reduction of risk(the subsequent repair rule). Perhaps settlement of disputes is preferred to their litigation,which leads to the exclusion of statements made during settlement talks.The encouragement of settlement is also a reason not to price litigation too low.The more the public subsidizes litigation,presumably the more of it there will be,and the less of pri-vate negotiation.There are still other policies that can be pursued.In the United States,we rest a vast body of exclusionary rules on the perceived need to regulate police investigative activities.Rules of evi-dence also can encourage or discourage certain kinds of law suits from being brought.Again in the United States,we went through a period in which we thought rape victims were being overly discouraged from re-porting crimes against them,and one response was to create rules of evidence that reduced the abuse at trial that such individuals may have been exposed to.General Considerations of Fairness may also influence the law of evidence,although the precise effect of this variable is often hard to sort out from more overtly utilitarian motivations.Some think that the limit on unfairly prejudicial evidence reflects not just the concern about accuracy but the concern about humili-ation,as is also the case with rape relevancy rules.The limits on prior behavior and propensity evidence reflect in part a belief that an individual should not be trapped in the past.The hearsay rule to some ex-tent reflects the values of the right to confront witnesses against you.The Risk of Error.A mistake free legal system is not possible.It is critically important to recognize that two types of errors can be made–a wrongful verdict for a plaintiff(including a conviction of an inno-cent person),which we call a Type I or false positive error,and a wrongful verdict for a defendant(includ-ing an acquittal of a guilty person),which we call a Type II or false negative error–and resource alloca-tion and other decisions will affect the relationship between these two types of errors.Reasonable people can disagree as to the significance of these two types of errors,but both must be taken into account in the construction of the legal system.In the United States,we structure civil litiga-tion to attempt to both equalize the errors made on behalf of plaintiffs and defendants and to reduce the total number of errors.The criminal justice process,by contrast,is designed to reduce the possibility of wrongful conviction at the admitted expense of making more mistakes of wrongful acquittals.Although the matter is complicated,these perspectives explain in large measure the preponderance standard in civil cas-es and the standard of proof beyond reasonable doubt in criminal cases.In civil cases,an error either way results in identical misallocation of resources.If the plaintiff wrongly wins a$500verdict,a citizen(the defendant)wrongly must part with$500.If the defendant wrongly wins a verdict that he or she does not owe$500,a citizen(the plaintiff)wrongly will be deprived of$500that rightfully he or she should possess. These two cases are identical analytically.In criminal cases,by contrast,in the United States we view a wrongful conviction as a more serious harm than a wrongful acquittal,and thus make convictions hard to obtain by requiring proof beyond reasonable doubt.We do so even though it is possible(but by no means certain)that a side effect will be increased numbers of false acquittals and an overall increase in the total number of errors.Again,I will say much more about this tomorrow,and I will cast some doubt upon how well these simple ideas work out in practice.Miscellaneous Policy Questions.There are many other contingent questions that must be answered by the architect of a legal system.Most importantly are those allocating responsibility over the various actors in the legal drama.These involve such questions as whether trials should be episodic events as is some-what more prevalent in Europe or single shot events as in the United States,how much discretion should the trial judge have and how much should the parties control the process,what is the relationship between trial judges and appellate judges.Should there be trial de novo in the appellate court or is it limited to re-view of legal errors?Are small civil cases different from large commercial cases in ways that justify differ-ent treatment?What about criminal cases?The matters discussed above indicate the breath of the foundations and implications of the law of evi-dence,and I now wish to make four analytical points,three of which are critical to understanding the foundations and implications of any body of law,and the fourth of which is critical to thinking clearly about the law of evidence.They involve:1.The distinction between the law on the books and the law in action;2.The relationship between procedural and evidentiary law,on the one hand,and substantive on the other law,and in particular how procedural and evidentiary law are in fact quite interrelated with rather than distinct from substantive law;3.Economics,or as we say in the United States,there is no free lunch.If you use a dollar(or yuan) here for one purpose you cannot use it there for a different purpose.4.Whether trials the ideal or instead are perverse.Is the legal system designed to encourage trials or settlement?What should it be designed for?I will discuss in turn each of these variables and their significance.1.The law on the books;the law in action.Constitutions are enacted,legislation is passed,executives issue orders and directives,courts decide,and one would think that the rest of us more or less obey.Un-fortunately(or perhaps fortunately),life is not so simple.When constitutions or laws are adopted in any multi-party decision making process,there will be multiple understandings of what the legal language con-notes.Some legislators may vote for the passage of a law even though they do not believe it goes far e-nough in its coverage(or even though it goes too far);others may vote against it for just the same reasons. There also may be serious disagreements as to precisely what a particular provision is supposed to mean or do.One person may think the legal language has one implication,and someone else may think it has a different implication.Statutory language in the abstract often will not resolve the meaning of those pounding the difficulty even further,legal language is often deliberately left vague because of the inability to come to agreement as to precisely what it should say or because of the omnipresent inability to anticipate all possible scenarios in which a particular problem might arise.In the United States,there is the added complexity of separation of powers.It is the legislature’s job to enact law,including in most states the law of evidence,but it is the courts’job to put that law into ef-fect.The judges may have different understandings of the implication of the language adopted by the leg-islature,and their institutional concerns will differ as well.Thus,the application of the law by the courts may differ from the idealized meaning of the law intended by a legislature or an individual legislator.The law of evidence has one potentially unique structural aspect that exacerbates the problem of in-definiteness.Aspects of the law of evidence are rule-like in the sense of providing necessary and suffi-cient conditions for the operation of a rule,but important parts of the law of evidence simply allocate re-sponsibility and discretion precisely because the relevant issue is too complicated for rule-like treatment. Perhaps the single most important aspect of the law of evidence–relevancy–has precisely this attribute. It is impossible to state a priori the necessary and sufficient conditions for the relevance of most evidence presented at any particular trial.Those determinations will necessarily be contingent on the unique char-acteristics of each trial,and it is literally impossible to articulate them in advance(how could we identify when a presently unknown witness will lie about a presently unknown topic?).Thus,the law of evidence vests responsibility in someone–party or judge–to determine what evidence to offer,and does so under quite general guidelines.In the United States,relevant evidence is defined as evidence that may increase or decrease the probability of some material fact being true,but virtually no effort is made to specify when the condition may be met.One last factor that may result in the law on the books being different from the law in action is that some areas of evidence law must try to accommodate quite opposed principles or impulses.This can result in part of the law making a promise and another part subverting that promise.Two important examples of this from American evidence law are the hearsay rule and the rule against character and propensity evi-dence.The hearsay rule promises to exclude hearsay,but there has been a unidirectional growth of the ex-ceptions to the hearsay rule for centuries.In civil cases,the promise of the exclusion of hearsay is rarely redeemed,and even in criminal cases hearsay is routinely admitted.Similarly,the law of evidence promis-es the exclusion of character and propensity evidence but then creates broad avenues of admission.2.The Relationship Between Substantive Law and Procedural Law.Substantive law is sometimes conceived of as quite distinct from evidentiary(and procedural)law,but this is misleading,for the two are in a complex and interactive relationship.This has become particularly clear,and is the subject of inter-esting legal research,in the United States due to the significance of the point for the protection of constitu-tional rights,but the point applies to general evidentiary matters as well.The decisions of the United States Supreme Court extending and enforcing individual rights have been viewed as imposing considerable constraints on the police and prosecutors,yet the legal system has not been greatly disturbed by these rul-ings.These systems are dynamic and infinitely adaptable and thus can and do respond to changes in un-predictable and astonishingly varied ways.Thus,“reform”to a dynamic process often cannot be imposedunproblematically through discrete measures that will have only the desired and no unintended conse-quences.One important aspect of this dynamic phenomenon is that legitimate substantive changes can blunt virtually any procedural innovation that emerges from courts or law reformers.An example of this point in the United States involves the fourth amendment limit on unreasonable searches and seizures.Suppose the police want to stop cars to do cursory inspections for criminality,but courts rule that the fourth amendment requires that the police have probable cause that a crime has been committed before a car can be stopped.All the legislature need do to make this judicial command a prac-tical nullity is to expand the criminal law to include more rigorous driving requirements.The legislature can essentially make it next to impossible to drive without violating a criminal statute(such as crossing the center line,driving too closely to the car ahead of you,not putting your turning light indicator on early e-nough or too early,etc.).If the legislature passes such laws,the police will be able to stop virtually any car by following it until the driver violates one of statutes regulating driving.The stop will be on“proba-ble cause”but the legislation will have expanded dramatically the potential sources of probable cause, thus subjecting everyone to being stopped by the police whenever the police decide to do so,notwithstand-ing the attempt by the courts to forbid just that process.Similarly,if the government cannot seize certain information without probable cause,it can often instead require that individuals keep records of the infor-mation it wants and divulge those records to the government.This point generalizes across evidentiary and procedural law.The most obvious example is materiali-ty,which is directly determined by the substantive law,but the point goes deeper than that.By changing the elements of causes of actions,legislatures can make recovery under those causes of actions easier or more difficult.Whether oral testimony concerning the meaning of contractual provisions is allowed–what we call the“parol evidence rule”in the United States–obviously impacts the evidentiary regime.Equally obviously,the statute of frauds that requires certain contracts to be in writing dominates normally eviden-tiary principles,as does res ipsa loquitur in tort law.Just as substantive law can affect the evidentiary process,evidence law can affect substantive law. The examples are legion.Rules of exclusion typically increase and rules of admission typically decrease the costs of litigation.As privileges expand,the cost of litigating and thus enforcing rights goes up in most instances.The ready admission of hearsay makes proof easier(although at the same time perhaps less re-liable),and so on.Discovery rules can dramatically affect parties’incentives to create and search for evi-dence.Individual rules like the rape relevancy rules can affect the ease with which cases may be proven. Allocation of burdens of proof can encourage or discourage the bringing of certain causes of action,and so on.Again,we will spend most of tomorrow talking in greater depth about such matters.There is one other interaction between substantive and evidence law that should be noted.In the U-nited States,but perhaps not in China,evidence underlies everything the lawyer does,since in the United States everything can collapse into litigation.Wills,criminal matters(sentencing based in part on what's in record),anti-trust,commercial work,everything.Evidence bears upon every other legal field,and the worst case scenario of every legal transaction is the collapse into litigation.In litigation,a crucial variable will be what can be proven.Thus every attorney,no matter how remote from the courtroom,must take the courtroom into account,which means taking the rules of evidence into account prior to litigation so that if litigation ensues the necessary facts can be proven.Good records must be kept and be in an admissible format,for example.3.Economics.We have a saying in the United States that“There is no such thing as a free lunch,”which means that,if someone“invites”you to lunch,he probably wants to talk to you about something or。

第三章证据的理论基础和基本原则第一节证据法的理论基础一、认识论(一)司法证明是一种特殊的认识活动。

证据法的主旨在于规范司法证明活动,因此探讨证据法的理论基础要从司法证明活动开始。

司法证明属于社会证明的范畴,但同生活中的证明如实验室证明又有很大区别:A、司法证明必须接受证据规则、法律规范以及其他人为因素的制约;B、司法证明有着场所和时间的限制;C司法证明通常由不知情的法官主持,精通法律但不一定精通专业知识,要借助专家协助,证明主体与认识主体相分离。

(二)我国证据法在认识论方面的理论基础是辨证唯物主义认识论辨证唯物主义认识论主要有三个基本理论要素构成1、物质论:即物质或存在是第一性的,意识或思维是第二性的,物质决定意识。

世界是物质的,物质是运动的,物质具有客观实在性,这种物质论表明任何案件都是物质的,司法人员所要查明和证明的对象总是物质性额案件事实。

存在于人脑中的思想活动和思维意向不构成案件。

2、反映论:即思维是大脑的技能,是对存在的反应。

辨证唯物主义认为物质运动的结果必然呈现一定的形态,因此各种证据都是案件事实的反映。

生活中的案件类型各不相同,但都具有特定性、稳定性、和反映性。

特定性表明,任何案件都具有不同于其他案件的质的规定性,能与其他案件区别开来;稳定性表明,任何案件都具有相对静止、暂时平衡和稳定的特点,能够在一定的时间内保持不变;反应性表明,任何案件的特征都能在其特征反映体中得到良好的反映,且能够为人们所认识。

反映论表明,各种证据就是案件的反映。

反映论表明,绝大多数司法证明活动就是一种同一认定活动。

即“人--- 事同一认定”。

3、可知论:即认为思维和存在之间具有同一性,人的认识可以正确的反映客观世界。

辨证唯物主义认为人的思维是至上的,能够认识现存世界的一切事物和现象,因此任何案件事实从理论上都是可以查明和证明的。

并且,辨证唯物主义主张可知论是相对的。

、方法论---- 我们不但要提出任务,而且要解决完成任务的方法问题。

论证据学的理论基础【内容提要】近年来,有些学者质疑甚至否定证据学或证据法学辩证唯物主义的理论基础,提出围绕证据的活动是不是认识活动的问题、从“证据学”到“证据法学”的理论转型问题以及辩证唯物主义认识论与程序工具主义有密切的关系并为程序工具主义和程序虚无主义提供合理化解释等问题。

这些观点均不能成立。

证据学或证据法学的辩证唯物主义理论基础不可动摇。

【关键词】证据学理论基础辩证唯物主义辩证法认识论[Abstract]In recent years,some scholars have questioned or even negative evidence,or evidence law adj materialist theoretical basis,put forward around evidence of activity is it right?Understanding activity problem,from“evidence”to“evidence law”theory transformation as well as the dialectical materialist theory of knowledge and the procedure instrumentalism has close relationship and for program tool justice and procedure nihilism provides reasonable explanation of the problem. These views are not tenable. The science of evidence or the evidence law adj materialism theory unshakable.[Key words]the science of evidence;theoretical basis;dialectical materialism;dialectics epistemology证据学的理论基础本不是一个复杂的问题。

证据法学的理论基础以裁判事实的可接受性为中心一、概述证据法学作为法律科学的一个重要分支,专注于研究证据规则、证据能力和证据可采性等问题,其核心目标在于确保裁判事实的公正、客观和可接受性。

在司法实践中,裁判事实的可接受性不仅关系到个案的公正处理,更对法治社会的构建和维护起着至关重要的作用。

深入探究证据法学的理论基础,特别是以裁判事实的可接受性为中心,对于提升司法公正、增强法律信仰、保障人权等方面具有深远的理论价值和实践意义。

本文将从证据法学的理论基础出发,系统分析裁判事实可接受性的内涵、影响因素和实现路径。

通过界定裁判事实可接受性的基本概念和特征,明确其在证据法学体系中的核心地位。

深入探讨影响裁判事实可接受性的诸多因素,包括证据规则、证明标准、法官自由裁量权等。

结合国内外证据法学的理论研究成果和司法实践经验,提出提高裁判事实可接受性的具体路径和方法。

通过本文的研究,旨在为我国证据法学的理论发展和司法实践提供有益的参考和借鉴,为实现司法公正、提升司法公信力贡献智慧和力量。

1. 介绍证据法学的重要性和在司法体系中的地位。

证据法学作为法学的一个重要分支,主要关注在法律程序中如何运用证据来认定案件事实。

它是确保司法公正、提高司法效率以及实现社会公平正义的关键因素。

在司法体系中,证据法学扮演着举足轻重的角色。

证据法学的重要性首先体现在其为裁判者提供了明确、系统的证据规则和原则,以确保他们在认定案件事实时能够遵循科学的方法,避免主观臆断和偏见。

同时,证据法学也要求裁判者在评价证据时保持中立和客观,从而确保裁判结果的公正性和可信度。

证据法学在司法体系中的地位也不容忽视。

它是连接实体法和程序法的桥梁,为实体法的实施提供了必要的程序保障。

在诉讼过程中,证据法学不仅关注证据的收集、审查和判断,还关注证据与案件事实之间的关系,以及证据对裁判结果的影响。

证据法学在司法体系中的地位可以说是举足轻重,对于实现司法公正、提高司法效率以及维护社会公平正义具有不可替代的作用。

证据法学的理论基础———以裁判事实的可接受性为中心易延友Ξ内容提要:裁判事实的可接受性是诉讼证明的核心问题,也是证据理论和证据规则所要解决的首要问题。

在当事人主义模式下,裁判结果的可接受性主要来源于程序的正当性;在职权主义模式下,裁判事实的可接受性则更多地来源于裁判事实的“客观性”。

辩证唯物主义认识论无法为证明模式的建构提供指导,也难以为证据规则的设立提供合理的解释。

适当借鉴实用主义哲学的合理因素,是重构我国证据法学理论基础的可行途径。

关键词:裁判事实 可接受性 证据法学 理论基础 实用主义引 言我国证据法学中的客观真实论以马克思主义的辩证唯物主义认识论为指导,独步学界四十余年。

这一理论认为,发现真实是诉讼中最重要的价值。

笔者并不否认发现真实在诉讼证明中的重要性,但是,笔者认为,裁判事实的可接受性才是诉讼证明的核心问题,也是证据理论和证据规则所要解决的首要问题。

就此而言,发现真实这一价值仅仅具有从属性地位。

所谓证据法学的理论基础问题,就是如何获得裁判事实的可接受性问题,而不是如何发现真实的问题。

近年来,诉讼法学界对证据法学理论基础的探索可谓方兴未艾,但是学者们在提出各自对证据法学理论基础的看法时却似乎忘记了一个更为根本的问题,那就是:探索证据法学的理论基础,其意义何在?笔者认为,证据法学的理论基础应当具备两方面的功能:一是为证据立法提供指导,二是为已经存在的证据规则提供合理的解释。

为证据立法提供指导,就是根据从理论中抽象出的原则,确立裁判事实可接受性的适当模式;同时,根据对现行诉讼证明模式的理论分析,指出法律改革的应然方向。

对证据规则提供解释,就是在已经存在的证据法体制下,对证据规则存在的合理性进行说明。

我国目前的证据法学理论,难以起到这两方面的作用。

本文试图通过对裁判事实可接受性的论述,提出重构我国证据法学理论基础的可能路径。

一、诉讼的功能与裁判事实的可接受性功能学派的社会人类学者认为,一切社会制度都是为了满足一定的社会需要而设置的。

证据法学的理论基础摘要:证据法学是研究证据规则的学科,它是以诉讼活动为基础并存在于诉讼活动中的,以刑事诉讼为例,刑事诉讼活动是一种认识活动,受认识论的指导,因此,证据法学也是以认识论为其理论基础的。

另一方面,程序正义论也是证据法学的理论基础,只不过认识论与程序正义论处于不同层次而已,证据法学的理论基础是以认识论为原则,以程序正义论为例外。

一、问题的提出长期以来,我国证据法学都是以认识论为其理论基础的,认为马克思主义的辩证唯物主义认识论作为基础指导着证据法学的发展。

但是,近来,有学者提出了不同观点,对认识论的理论基础地位进行质疑,并在21世纪初期展开了对证据法学理论基础的反思。

关于证据法学的理论基础,除了传统观点的认识论之外,目前学界主要有以下几种不同观点:一种观点是价值论,认为证据法学的理论基础应该从认识论走向价值论,应将其建立在形式理性和程序正义的基础之上;另一种是二元论,即认为辩证唯物主义认识论与程序正义理论二者的对立统一是指导我们研究证据法学的理论基础。

与二元论相似,也有学者认为:“辩证唯物主义认识论与价值论是不矛盾的,两者存在着内在的联系。

可见,在证据法的理论基础上,价值论应成为认识论的必要补充”。

综观这几种不同观点,可以看到在传统的马克思主义的认识论作为证据法学的地位受到挑战之后,程序正义作为证据法学的理论基础得到越来越多的人支持,基本再不存在争议。

所以,要弄清楚证据法学的理论基础,只需要解决这样两个问题:首先,认识论到底是不是证据法学的理论基础;其次,如果认识论是证据法学的理论基础,它与程序正义论之间又是什么关系。

以下详细分析。

二、认识论能否作为证据法学的理论基础要看认识论是不是证据法学的理论基础,就要从证据法学的概念及一些相关基本问题入手。

首先,关于证据法学的概念,学术界也有不同观点,一种观点认为:“所谓证据法学,应当是对证据规则(有关证据的法律规则)的意义进行探求的学问”,“它的研究领域只能拓展至有关证据规则的哲学原理、历史渊源、社会效果等内容”;也有学者这样定义:“证据法学主要是研究如何在法律上对待收集的证据,是以一系列约束查明案件事实方法的规则为主要研究对象的理论法学,它并不致力于发现事实真相,而是旨在保障合理而正当地发现真相,因此可以归入程序法学的领域”;还有学者将刑事证据法所规范的主体内容具体到“有关证据能力的规则和司法证明的规则”,而将带有程序性意义的证据规则排除在外[6]。