联合国难民署介绍

- 格式:doc

- 大小:35.00 KB

- 文档页数:6

人文关怀是指对人的尊严、价值、命运的维护、追求和关切,它是人类社会文明进步的重要标志。

以下是一些真实的人文关怀事例:

1. 特蕾莎修女:特蕾莎修女是一位天主教修女,她致力于帮助穷人、病人和无家可归者。

她在印度创办了“慈善传教士修女会”,并在全球范围内开展了许多慈善工作,为那些需要帮助的人提供食物、医疗和庇护。

2. 联合国难民署:联合国难民署是一个专门处理难民问题的机构,它为全球数以百万计的难民提供庇护、食品、医疗和教育等方面的帮助。

联合国难民署还积极开展国际合作,为解决难民问题做出了巨大的贡献。

3. 红十字会:红十字会是一个国际人道主义组织,它在全球范围内开展了许多救援和援助工作,为那些遭受自然灾害、战争和疾病等困境的人们提供帮助。

4. 动物保护组织:动物保护组织致力于保护动物的权利和福利,它们开展了许多保护动物的工作,包括拯救濒危动物、防止虐待动物和推动动物保护立法等。

这些事例表明,人文关怀是一种跨越国界、文化和宗教的价值观,它可以促进人类社会的和谐、进步和发展。

2004年7月第6卷InternationalForumJul.,2004Vol.6国际政治论联合国难民署的历史地位与现实作用何[关键词][中图分类号]一、联合国难民署的艰难历程联合国难民署成立于1950年12月14日,并于次年1月1日开始工作。

它当时的主要任务是处理欧洲二战之后的难民问题。

50年代初期,缺乏资金和美国的不合作,是它遇到的最大问题。

从联合国难民署的第一位专员上任起,就提出设立美元的经费,为联合国难民署的工作带来生机,使之能!1∀够有效地进行国际难民救助工作。

50年代后期,随着美苏争霸的范围扩大到亚非地区,第三世界国家反对殖民主义、帝国主义斗争的发展,以及一批第三世界国家进入联合国,苏联和不少亚非国家都相信联合国难民署在解决国际难民问题上有积极作用,而开始给予它支持。

在1955年的联合国大会上,苏联首次对于扩大联合国难民署活动的议案投了弃权票,而不是反对票,这也是有史以来第一次关于联合国难民署的议案没有反对票。

之后,联合国难民署的活动广泛开展起来。

联合国难民署成立后的第一次大规模活动,是介入1956年的匈牙利事件。

虽然在处理国际难民的问题上,意识形态之争为联合国难民署的活动打上了深深的政治烙印,但它还是力求从人道主义的角度,尽量公正地处理这些问题。

联合国难民署的贡献和作为,为自己赢得了声誉,得到国际社会的广泛承认和接受,它开始成为一个超越意识形态,以人道主义为宗旨,救助世界各地难民的重要国际组织,难民问题也开始成为引起国际社会广泛重视的一个问题。

1958年,联合国大会授权联合国难民署帮助解决阿尔及利亚在反对欧洲殖民主义、争取民族独立斗争中出现的难民问题,∃国际论坛%2004年第4期这也是联合国难民署首次向第三世界国家提供难民救助。

1959年,联合国呼吁各会员国为解决难民问题而努力,并将这年定为在50年代末以前,联合国难民署的每一项活动都要得到联合国大会的批准,设立相关机构,造成繁文缛节,诸多掣肘。

2023解决难民问题的3种办法2023解决难民问题的3种办法自愿遣返、就地融合和第三国安置。

国际社会曾呼吁,在救助青少年难民时,不仅应着手解决他们的营养和健康问题,更应向他们提供教育和培训的机会,不断发掘青少年难民的潜力,为其未来的发展作准备。

2023世界难民日由来非洲拥有最多的难民并一向以慷慨相助著称。

作为非洲团结的象征,2001年,联合国大会通过了一项特殊的决议。

在这项决议中,大会注意到2001年是1951年的《关于难民地位的公约》五十周年,并且非洲统一组织同意国际难民日与6月20日非洲难民日可在同一天举行。

大会由此决定从2001年起,把6 月20日定为“世界难民日”。

难民问题一直是国际社会的一大顽疾。

为保证难民的基本权利,以及通过国际合作解决难民地位问题,早在1951年,联合国难民和无国籍人地位全权代表会议通过了《关于难民地位的公约》。

由于,灾难、战争、民族及种族争端等使得难民问题日益严重。

特别是从1993年到2003年这十年来,世界范围内爆发了80多起战争或冲突,造成了大规模的难民潮,难民数量一直高达2000多万人以上,1994年曾达到 2742万人,其中,妇女和儿童占难民总数的80%,难民问题的日益严重引起了国际社会的巨大关注。

从2001年起,把每年的6月20日定为“世界难民日”。

联合国希望借此引起人们对难民问题的关注,并对难民为社会作出的贡献有所认识、尊重。

第一个“世界难民日”在什么时候?2001年2023难民署联合国难民署的任务是领导和协调国际行动,以在全球范围内保护难民和解决难民问题。

联合国难民署的任务区别于其他人道主义行为体,它必须为那些不愿意接受当地政府管辖的难民提供国际保护和援助。

同时,联合国难民署也认识到,国际合作和支援都需要东道国的配合和努力,他们对满足难民的需求承担着主要责任。

难民被迫迁徙的当前趋势愈演愈烈,不断考验着国际体系的承受力。

20XX 年伊始,大约有3390万世界人口被联合国难民署认定为“受关注的人群”,这一数据比起2005年时的1920万有了明显的增加。

国籍和无国籍:议员手册联合国难民署办公室议会联盟国籍和无国籍议员手册1致谢本手册的编制过程中得到了民主和人权常务委员会议会联盟署的帮助。

调研和分析:Carol Batchelor和Philippe Leclerc(联合国难民署)执笔人:Marilyn Achiron女士编辑组:联合国难民署:Erika Feller, Philippe Leclerc, José Riera 和 Sara Baschetti 议会联盟:Anders B. Johnsson 和 Kareen Jabre原始版本:英语封面设计:瑞士Infographie工作室的Jacques Wandfluh印刷:瑞士的 SADAG Imprimerie公司2前言“人人有权享有国籍。

不得任意剥夺任何人的国籍, 亦不得否认其改变国籍的权利。

”《1948年世界人权宣言》第15条用简洁的语言赋予了每个人与某个国家具有法律联系的权利。

公民身份或国籍(同在国际法律内一样,这两个术语在本手册中交替使用)不仅让人们有归属感,而且赋予了个人享有国家保护的权利,享有许多公民和政治权利。

事实上,公民身份被认为是“去获取权利的权利”。

尽管国际法主要阐述了公民身份的获得、丢失或拒绝相关议题,但是全世界仍有数百万人没有国籍。

他们是无国籍人。

产生无国籍的原因有很多,包括法律冲突、领土的转移、婚姻法、管理规程、歧视、没有出生登记、剥夺国籍(某一国家剥夺某人的国籍)、脱离关系(某人拒绝某一国家的保护)。

世界上很多无国籍的人同时也是被迫流离失所的受害者。

那些背井离乡的人更容易失去国籍,尤其当他们移居后领土重新被划定时更是如此。

相反地,无国籍和无公民权的个人经常被迫离开他们居住的地方。

这种与难民情况有关的联系最初促使联合国大会指定联合国难民署作为负责监督防止和减少无国籍情况出现的机构。

根据最新的估计数字,全世界目前有1100万的无国籍人。

但这个数字仅为推测的数字。

联合国机构一览表Organs of United Nationsaaaa1946年6月《联合国宪章》在美国旧金山签署,同年10月《宪章》生效,联合国正式成立。

其宗旨是维持国际和平及安全,制止侵略行为,发展国际间以尊重人民平等权利及自决原则为根据的友好关系,促成国际合作等。

凡要求加入联合国的国家必须声明接受宪章规定的义务,由安理会推荐,经联合国大会2/3票数通过,才被接纳为会员国。

截止1996年4月,已有185个会员国。

联合国有6个主要机构:大会、安全理事会、经社理事会、托管理事会、国际法院和秘书处。

联合国总部设在纽约,在瑞士日内瓦设有联合国欧洲办事处。

主要机构及其附属机构、特设机构和其他有关机构如下:大会General Assembly主要委员会:Main Committees:第一委员会(裁军和国际安全委员会)First Committee (Disarmament and International Security Committee)第二委员会(经济和财政委员会)Second Committee (Economic and Financial Committee)第三委员会(社会、人道主义和文化委员会)Third Committee (Social, Humanitarian and Cultural Committee)第四委员会(政治和非殖民化委员会)Fourth Committee (Special Political and Decolonization Committee)第五委员会(行政和预算委员会)Fifth Committee (Administrative and Budgetary Committe e)第六委员会(法律委员会)SixthCommittee (Legal Committee)特别政治委员会Special Political Committee程序委员会:Procedural Committee:总务委员会General Committee全权证书委员会Credentials Committee常设委员会:Standing Committees:行政和预算问题咨询委员会Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions-- ACABQ会费委员会Committee on Contributions国际公务员制度委员会International Civil Service Commission新闻委员会Committee on Information附属机构、特设机构和其他有关机构:Subsidiary, Ad Hoc and Related Bodies:中部非洲安全常设委员会(1992年5月成立)Standing Committee on Security Questions in Central Africa大会临时委员会(俗称“小型联大”)Interim Committee of the General Assembly维持和平行动特别委员会Special Committee on Peace-Keeping O perations联合国宪章和加强联合国作用特别委员会Special Committee on the Charter of the United N ations and on theStrengthening of the Role of the Organization裁军审议委员会Disarmament Commission -- UNDC世界裁军会议问题特设委员会Ad Hoc Committee of the World Disarmament Conference审查联合国在裁军领域所起作用特设委员会Ad Hoc Committee on the Review of the Roleof the United Nations in the Field of Disarmament印度洋特设委员会Ad Hoc Committee on the Indian Ocean和平利用外层空间委员会Committee of Peaceful Uses of Outer Space -- COPUOS 联合国科学咨询委员会(科学咨委会)United Nations Scientific Advisory Committee联合国原子辐射影响问题科学委员会(辐射科委会)United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation -- UNSCEAR调查和调解小组Panel for inquiry and Conciliation和平观察委员会Peace Observation Commission军事专家小组Panel of Military Experts联合国巴勒斯坦和解委员会United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine -- UNCCP 巴勒斯坦人民行使不可剥夺权利委员会Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People给予殖民地国家和人民独立宣言执行情况特别委员会Special Committee on the Situation with Regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to C olonial Countries and Peoples种族隔离问题特别委员会Special Committee on Apartheid联合国南非信托基金委员会Committee of Trustees of the United Nations Trust Fund for South Africa联合国纳米比亚基金United Nations Fund for Namibia安哥拉情势问题小组委员会Sub-Committee on the Situation in Angola联合国南部非洲教育和训练方案咨询委员会Advisory Committee on the United Nations Educational and Training Programme for Southern Africa联合国贸易和发展会议(贸发会议)UnitedNations Conference on Trade and Development -- UNCTAD联合国贸发会议、世界贸易组织的国际贸易中心联合咨询小组Joint Advisory Group on the UNCTAD/WTO Inter national Trade Centre联合国防治艾滋病联合计划署United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS -- UNAIDS联合国开发计划署(开发计划署)United Nations Development Programme -- UNDP联合国工业发展组织(工发组织)United Nations Industrial Development Organization -- UNIDO联合国环境规划署(环境规划署)United Nations EnvironmentProgramme -- UNEP联合国特别基金United Nations Special Fund -- UNSF联合国人口基金会United Nations Population Fund -- UNPF世界粮食计划署World Food Programme -- WFP联合国人类住区(生境)委员会United Nations Commission on Human Settlements -- UNCHS (Ha bitat)联合国系统结构问题专家小组Group of Experts on the Structure of the United Nations System改组联合国系统经济和社会部门特设委员会Ad Hoc Committee on the Restructuring of the Economic and Social Sectors of the United Nations System世界粮食理事会World Food Council-- WFC联合国训练研究所(训研所)United Nations Institute for Training and Research -- UNITAR联合国大学United Nations University -- UNU青年问题特设咨询小组Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Youth联合国儿童基金会(儿童基金会)United Nations Children's Fund --UNICEF消除种族歧视委员会Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination -- CERD联合国人权奖得奖人遴选事宜特别委员会Special Committee to Select the Winners of the United Nations Hu man Rights Prize联合国难民事务高级专员公署(难民署)Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees -- UNHCR领土庇护公约草案专家小组Group of Experts on the Draft Convention on Terrtiorial Asylum国际妇女年会议协商委员会审计委员会Board of Auditors外聘审计团Panel of ExternalAuditors联合检查组(联检组)nt Inspection Unit-JIU货币不稳定问题工作组Working Group on Currency Instability新闻工作协商小组Consultative Panel on PublicInformation会议委员会Committee on Conferences联合国方案和预算机构工作组Working Group on United Nations Programme and Budget Machinery联合国财政紧急情况协商委员会Negotiating Committee on the Financial Emergency of the United Nations联合国行政法庭United Nations Administrative Tribunal申请复核行政法庭判决事宜委员会Committee on Applications for Review of Administrative Tribunal Judgements国际法委员会International Law Commission -- ILC联合国宪章特设委员会Ad Hoc Committee on the Charter of the United Nations自然资源永久主权委员会mission of Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources联合国国际法教学、研究、传播和普及的援助方案咨询委员会Advisory Committee on the United Nations Programme of Assistance in the Teaching, Study, Dissemi nation and Wider Appreciation of International Law联合国国际贸易法委员会(贸易法委会)United Nations Commission on International Trade Law-- UNCITRAL与东道国关系委员会Committee on Relations with the Host Country国际原子能机构International atomic Energy Agency -- IAEA信息与资料中心(设在华沙,1995年10月正式使用)Information and Data Center增强国际关系中不使用武力原则效力问题特别委员会Special Committee on Enhancing the Effectiveness of the Principleof Non-use of force in InternationalRelations安全理事会(安理会)Security Council下设机构:联合国军事参谋团(军参团)Military Staff Committee -- UNMSC裁军审议委员会Disarmament Commission-- UNDC集体措施委员会CollectiveMeasures Committee联合国近东巴勒斯坦难民救济和工程处(近东救济工程处)United Nations Reliefand Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near Fast -- UNRW A常设机构:Standing Committees:专家委员会Committee of Experts接纳新会员国委员会Committee on the Admission of New Members安全理事会在总部以外地点开会问题委员会Committee on Council Meetings Away from Headquarters特设机构:Ad Hoc Committees:联合国印度尼西亚问题委员会United Nations Commission for Indonesia联合国停战监督组织United Nations TruceSupervision Organization -- UNTSO联合国驻印度巴基斯坦军事观察小组United Nations Military Observer Group on India and Pakistan-UNMOGIP反对种族隔离特别委员会Special Committee Against Apartheid联合国驻塞浦路斯维持和平部队(联塞部队)United Nations Peace-Keeping Force in Cyprus -- UNFICYP联合国紧急部队(紧急部队)United Nations Emergency Force -- UNEF联合国脱离接触观察员部队(观察员部队)United NationsDisengagement Observer force -- UNDOF根据安全理事会第253(1968)号决议设立的委员会(有关制裁罗得西亚的实施情况)Security Council Committee Established in Pursuance of Resolution 253 (1968) Concerning the Question of Southern Rhodesia微小国家”问题专家委员会Committee of Expertson the Question of Micro-States调查以色列侵犯占领区巴勒斯坦人民和其他阿拉伯人人权行为特别委员会Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories联合国监督伊拉克销毁化学、生物和核武器特别委员会U.N. Special Commission Supervising the Destruction of Iraq's Chemical, Biological and Nuclear Weapons -- UNSCOM联合国驻马其顿共和国预防性部署部队U.N. Prevention Deployment Force in theFormer Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia -- UNPREDEP联合国东斯拉沃尼亚、巴拉尼亚和西斯雷姆地区过渡行政当局(东斯过渡当局)U.N. TransitionalAdministration for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and W estern Sirmium -- UNTAES联合国驻普雷夫拉卡半岛军事观察团(联普观察团)U.N. Mission of Observers in Prevlaka -- UNMOP联合国驻格鲁吉亚观察团(联格观察团)U.N. Observer Mission in Georgia-- UNOMIG联合国驻黎巴嫩临时部队(联黎部队)U.N. interim force in Lebanon -- UNIFIL联合国伊拉克-科威特军事观察团(伊科观察团)U.N. Iraq-Kuwait Observation Mission -- UNIKOM联合国安哥拉观察团U.N. Angola Observer Mission联合国西撒哈拉公民投票特派团(西撒特派团)U.N. Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara -- MINURSO联合国利比里亚观察团(联利观察团)U.N. Observer Mission in Liberia -- UNOMIL国际警察工作队International Police Task Force -- IPTF联合国多国稳定部队U.N. Multinational Stabilization Force -- SFOR联合国驻塔吉克斯坦观察团(联塔观察团)U.N.Mission of Observers in Tajikistan联合国海地支助团U.N. Support Mission in Haiti -- UNSMIH联合国危地马拉军事观察团U.N. Missionof Military Observers in Guatemala联合国经济及社会理事会(经社理事会)United Nations Economic and Social Council -- ECOSOC会期委员会:Sessional Committees第一(经济)委员会First (Economic) Committee第二(社会)委员会Second (Social) Committee第三(计划和协调)委员会Third (Programme and Co-Ordination) Committee职司委员会:Functional Commissions:防止犯罪和刑事司法委员会(1992年设立)Commission on Crime Prevention and Cri minal Justice人权委员会Commission on Human Rights麻醉品委员会Commission on Narcotic Drugs社会发展委员会Commission for Social Development妇女地位委员会Commission on the Status of Women可持续发展委员会Commission on Sustainable Development(1993年2月12日设立)人口委员会Population Commission统计委员会Statistical Commission区域委员会:Regional Commissions:非洲经济委员会Economic Commission for Africa -- ECA欧洲经济委员会Economic Commission for Europe -- ECE拉丁美洲和加勒比经济委员会Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean -- ECLAC亚洲及太平洋经济社会委员会(亚太经社会)Economic and Social Commission for Asia andthe Pacific -- ESCAP西亚经济社会委员会Economic and Social Commissio for Western Asia -- ESCW A常设委员会:Standing Committees:行政协调委员会Administrative Committee on Co-Ordination -- ACC发展规划委员会Committee for Development Planning -- CDP危险物品运输问题专家委员会Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods人类住区委员会Commission on Human Settlement自然资源委员会Committee on Natural Resources -- CNR与政府间机构商谈委员会Committee on Negotiations with Intergovernmental Agencies非政府组织委员会Committee on Non-governmental Organizations方案和协调委员会Committee for Programme and Co-ordination -- CPC跨国公司委员会Commission on Transnational Corporations -- CTC特设机构和其他有关机构:Ad Hoc Bodies Other Related Bodies:联合国人口与发展委员会U.N. Commission on Population and Development联合国国际麻醉品管制署United Nations International Drug Control Programme -- UNIDCP世界粮食计划署World Food Programme -- WFP世界粮食理事会(粮食理事会)World Food Council -- WFC联合国社会发展研究所(社发研究所)United Nations Research institute for Social Development -- UNRISD联合国特别基金会United Nations Special Fund-- UNSF联合国地名专家小组UnitedNations Group of Experts on Geographical Names发达国家和发展中国家间税务条约专家小组Group ofExperts on Tax Treaties Between Developed and Developing Countries设立提高妇女地位国际研究训练所问题专家小组Group of Experts on the Establishment of an International Research and Training institute for the Advancement of Women联合国贸易和发展会议(贸发会议)United Nations Conference onTrade and Development -- UNCTAD联合国儿童基金会(儿童基金会)United Nations Children's Fund-- UNICEF联合国难民事务高级专员公署(难民署)Office of the United Nations High Commissionerfor Refugees - UNHCR联合国开发计划署(开发计划署)United Nations Development Programme -- UNDP联合国环境规划署(环境规划署)United Nations Environment Programme -- UNEP联合国人口基金会United Nations Population Fund -- UNFPA联合国训练研究所(训研所)United Nations institute for Training and Research -- UNITAR联合国大学United Nations University -- UNUFAO联合国人类住区(生境)中心United Nations Commission on Human Settlements -- UN CHS (habitat)与经社理事会有关的专门机构和独立组织:世界贸易组织World Trade Organization -- WTO国际劳工组织International Labor Organization -- ILO联合国粮食及农业组织(粮农组织)Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations -- FAO联合国教育、科学及文化组织(教科文组织)United NationsEducational, Scientific and Cultural Organization -- UNESCO世界卫生组织World HealthOrganization -- WHO国际货币基金组织International Monetary Fund -- IMF国际开发协会Internatoinal Development Association -- IDA国际复兴开发银行(世界银行)International Bank for Reconstruction and Development -- IBRD国际金融公司International Finance Corporation -- IFC国际民用航空组织International Civil Aviation Organization -- ICAO万国邮政联盟Universal Postal Union -- UPU国际电信联盟International Telecommunication Union -- ITU世界气象组织World Meterological Organization -- WMO国际海事组织International Maritime Organization -- IMO世界知识产权组织World intellectual Property Organization -- WIPO国际农业发展基金会(农发基会)International Fund for Agricultural Development -- IFAD联合国工业发展组织(工发组织)United Nations industrial Developmen t Organization -- UNIDO托管理事会Trusteeship Council国际法院International Courtof Justice -- ICJ下设:简易程序分庭Chamber of Summary Procedure预算和行政委员会Budgetrary and Administrative Co mmittee关系委员会Committee on Relations图书馆委员会Library Committee修订国际法规约委员会Committee for the Revision of the Rules of the Court审判前南斯拉夫战犯法庭International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia -- ICTY卢旺达问题国际刑事法庭International Criminal Tribuanal forRwanda -- ICTR国际海洋法法庭International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea -- ITLS秘书处United Nations Secretariat主要机构:秘书长办公厅Executive officeof the Secretary-General负责特别政治事务的副秘书长办公室Office of the Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs负责政治和大会事务的副秘书长办公室Office of the Under-Secretary-General for Political and GeneralAssembly Affairs负责特别政治问题的助理秘书长办公室Office of the Assistant Secretary-General for Political andGeneral Assembly Affairs法律事务厅Office of Legal Affairs -- EEG机构间事务和协调厅Office of Inter-Agency Affairs and Coordination政治和安全理事会事务部Department of Political and Security Council Affai rs -- DPSCA/PSCA政治事务、托管和非殖民化部Department of Political Affairs, Trusteeship and De-Colonization国际经济和社会事务部Department of International Economic and Social Affairs联合国跨国公司中心United Nations Centre on Transnational Corporations行政和管理事务部Department of Administration and Management会议事务部Department of ConferenceServices新闻部Office of PublicInformation联合国日内瓦办事处United Nations office at Geneva。

(具有普适意义的,可能与本案有关的)一、专门规定保护难民的条约:1933年《难民公约》1931年《国际联盟南森国际难民署的规约》1946年《国际难民组织章程》1950年《联合国难民署章程》1951年《难民公约》1967年《难民议定书》1959年欧洲理事会通过的《关于取消难民签证的欧洲协定》1980年《关于转移对难民责任的欧洲协定》1954年《关于领土庇护公约》二、使用难民保护的人权保护公约:所有保护人的基本权利和自由条约都可以适用于难民世界层面上主要有:1919年《国际劳工组织章程》1930年《关于强迫劳动的公约》1945年《联合国宪章》1954年《关于无国籍人地位的公约》1957年《废止强迫劳动的公约》1961年《减少无国籍人状态公约》1966年《经济、社会和文化权利国际公约》和《公民权利和政治权利国际公约》1984年《禁止酷刑和其他残忍、不人道或有辱人格待遇或处罚公约》区域性保护人权条约:1950年《保护人权和基本自由的欧洲公约》及其12个议定书1957年《欧洲引渡条约》1961年《欧洲社会宪章》及其两个附加议定书和修订议定书1987年《防止酷刑、不人道或有辱人格的待遇或处罚的欧洲公约》及其两个议定书。

三、国际习惯1、难民不推回原则:不得强制将难民退回到其生命和自由受到威胁的领土范围,包括不难民驱逐或引渡到其生命和自由受到威胁的国家。

——————联合国难民署编:《难民》(中文本)第123期,2001年版,17页,第六章,关于不推回原则的国际习惯法地位之详细论述。

·1980年难民高专方案执委会第31届会议通过的第17(XXXI)号“影响难民的引渡问题”决议称:“重申普遍公认的‘不推回’原则的基本性质;认识到难民应受保护,不被引渡到他们根据1951年《难民公约》第1(A)(2)项所列举的条件有充分理由惧怕在那里会遭受迫害的国家,请各国保证在订立引渡条约和制定有关引渡的任何国家立法时,应充分考虑到‘不推回’原则;希望各国适用现有的引渡条约时,应适当顾及‘不推回’原则。

各国际组织驻华代表机构作为世界上最大的发展中国家和第二大经济体,中国一直以来都在积极参与并推动国际合作与交流。

为了更好地促进与其他国家和国际组织的合作,中国政府允许各国际组织在中国设立代表机构。

本文将介绍一些在中国的重要的国际组织代表机构。

联合国作为具有世界影响力的国际组织,联合国在中国设立了多个代表机构,包括联合国办事处、联合国开发计划署、联合国难民署等等。

这些机构的任务主要是协调和推进联合国在中国的所有工作,包括支持中国的发展和促进中国与联合国其他成员国之间的合作。

世界卫生组织世界卫生组织是致力于增强全球健康的国际组织,其在中国的代表机构主要是负责支持中国的卫生领域发展,包括传染病控制和卫生系统改革等。

中国是世界卫生组织的创始成员国之一,两者的合作历史悠久。

世界银行世界银行是致力于促进全球经济和社会发展的国际金融机构,其在中国的代表机构主要是负责与中国政府、企业和社会各界合作,支持中国的可持续发展、减贫和推进市场化改革。

国际货币基金组织国际货币基金组织是一个致力于促进全球货币稳定、国际贸易和金融合作的国际财经组织,其在中国的代表机构主要是负责与中国政府、企业和社会各界合作,支持稳定的国际金融和货币制度。

亚太经合组织亚太经合组织是一个由亚洲和太平洋地区的成员国组成的国际组织,成员国包括美国、中国、日本、俄罗斯等等。

其在中国的代表机构负责促进中国与其他成员国之间的贸易合作、投资和人员交流等。

上海合作组织上海合作组织是一个由中国、俄罗斯、哈萨克斯坦、吉尔吉斯斯坦、塔吉克斯坦、乌兹别克斯坦等成员国组成的地区性组织,旨在加强成员国之间的经济、安全和文化等方面的合作。

其在中国的代表机构主要是协调和推进上海合作组织在中国境内的所有工作,包括组织会议、推进合作等。

除上述组织外,还有很多其他国际组织在中国设立了代表机构,如世贸组织、联合国教科文组织、国际劳工组织等等。

这些代表机构的存在不仅促进了中国与国际组织之间的合作和交流,同时也为中国发展和世界贡献了力量。

如何通过模拟联合国联合国难民署锻炼青少年的难民问题意识和人文关怀?引言模拟联合国是让青少年通过模拟国际组织会议的方式,了解国际事务、增强团队协作、锻炼辩论能力的活动。

模拟联合国联合国难民署锻炼青少年的难民问题意识和人文关怀,对于培养青少年的社会责任感和全球视野至关重要。

本文将介绍如何借助模拟联合国的方式,培养青少年的难民问题意识和人文关怀。

正文1.认识模拟联合国模拟联合国是一种教育活动,通过模拟国际组织会议的方式,让参与者扮演不同国家或组织的代表,就国际事务进行辩论和协商。

模拟联合国的参与者在活动中扮演的角色包括各国政府代表、非政府组织代表、记者等。

2.了解联合国难民署联合国难民署(UNHCR)是联合国的一个专门机构,致力于保护和帮助世界各地的难民和流离失所者。

UNHCR的工作范围包括提供紧急救援、难民登记、安置和保护、教育等。

3.组织模拟联合国活动3.1 设定主题针对难民问题,可以设定不同的主题,例如“难民保护与安置”、“难民教育与文化融合”等。

主题的设定应当与参与者的年龄和背景相适应。

3.2 角色扮演参与者可以扮演联合国难民署代表、各国政府代表、非政府组织代表等角色,通过模拟会议形式进行辩论、协商和决策。

3.3 辩论与协商参与者需要根据自己所扮演的角色,准备辩论和协商的议题,并分别代表各自的立场进行辩论和协商。

通过这个过程,参与者不仅可以了解各国在难民问题上的立场和政策,还可以锻炼自己的辩论能力和团队合作精神。

4.培养难民问题意识和人文关怀4.1 认知与了解通过模拟联合国活动,青少年可以更加深入地认识难民问题的严重性和全球性,了解不同国家和组织在难民问题上的观点和政策。

4.2 情感与体验通过模拟联合国活动,参与者可以身临其境地感受到难民所面临的困境和挑战,培养同理心和人文关怀。

4.3 思考与行动模拟联合国活动不仅仅是一个辩论和协商的过程,更是一个思考和行动的过程。

参与者在活动中可以思考如何解决难民问题,如何改善难民的生活,并在现实生活中采取行动。

关注难民——联合国难民署介绍宋 菁宋菁,1995年毕业于华中理工大学外语系,随后进入浙江电视台工作。

1998年至2000年在北京广播学院电视系攻读新闻学硕士学位,毕业后进入联合国难民署驻华代表处任驻在国新闻官员。

1. 难民国际保护的发展过程联合国难民署并不是世界上第一个从事难民保护的机构。

在它之前,还有像联合国救济及复原管理办事处和国际难民组织这些机构处理过难民事务。

但成立于1950年12月14日的联合国难民署是第一个全面处理难民事务的机构。

1951年联合国关于《难民地位的公约》签订,这两件事第一次在国际法的范畴内对难民进行援助,同时为他们提供保护。

在难民署成立的时候,也就是在1950年的时候,它的职责是保护二次大战后欧洲的难民。

但是在后来,难民危机发展到全世界各地,成为一个全球性的危机。

联合国难民署由联合国大会成立,同时也向联合国大会汇报工作。

联合国难民署的大部分资金来自各国政府的捐助。

到2002年1月l日,难民署一共在114个国家设有办公室,一共有5500个工作人员,84%都是在一线工作的,其中一些是比较偏远的地区。

我们这里写了,我们现在的高级专员是吕贝尔斯。

他是二战以后荷兰任期最长的首相。

那么大家谁知道我们前一任高级专员是谁?知道的人不少,是绪方贞子。

吕贝尔斯是在2001年1月1日就任的,他由联合国大会任命,同时通过联合国经济和社会理事会向联合国大会汇报工作。

难民署的预算由我们的执行委员会(联合国难民署执行委员会)来批准。

这个执行委员会目前由57个国家共同组成。

我们中国是其中的一个。

2. 联合国难民署做什么样的工作?首先大家看一下这个UNHCR。

谁知道这个UNHCR是什么的缩写?对,UN是United Nations。

HCR呢?就有困难了。

这R呢,就是Refugee,难民,是吧?HC是High Commissioner,高级专员,所以我们的全称是联合国难民事务高级专员署。

顾名思义,我们是一个联合国的机构。

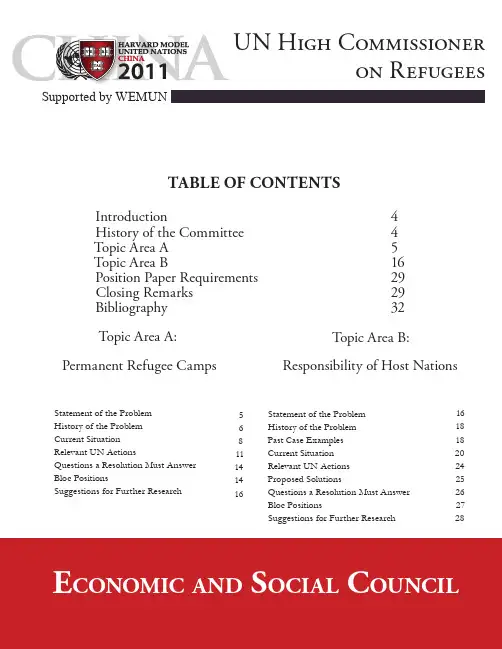

1Supported by WE MUNUN High Commissioneron RefugeesE S c Statement of the ProblemHistory of the Problem Current Situation Relevant UN ActionsQuestions a Resolution Must Answer Bloc PositionsSuggestions for Further Research56811141416Topic Area A:Permanent Refugee CampsTopic Area B:Statement of the Problem History of the Problem Past Case Examples Current Situation Relevant UN Actions Proposed SolutionsQuestions a Resolution Must Answer Bloc PositionsSuggestions for Further Research161818 202425 26 27 28Responsibility of Host NationsIntroduction 4History of the C ommittee 4Topic Area A 5Topic Area B 16Position Paper Requirements 29C losing Remarks 29Bibliography 32TABLE OF CONTENTS22Dear Delegates,It is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to Harvard Model United Nations China 2011! My name is Kerry Yang, and I have the honor of serving as your Secretary-General this year. I am a senior at Harvard studying Economics, and I have served twice on the Secretariat of Harvard’s college confer-ence, Harvard National Model United Nations. HMUN China 2011 will be my 21st Model UN conference, and I very much look forward to sharing this experience with all of you.As you prepare for committee, I hope you are looking ahead to the amazing experience that awaits you in Shanghai. Over 1,000 delegates, not unlike you, are poring over similar materials all over the world in anticipation of this four-day event. You and your peers will tackle issues of immense inter-national gravity, from cultural preservation in the face of globalization and global terrorism to the financial crisis and prevention of pandemics in the face of natural disasters. Alliances will form, blocs will strategize and negotiate, and at the end of the day, friendships will develop and flourish. The entire Conference Staff has been working tirelessly since last April to ensure that you enjoy an exciting and educational conference experience with the utmost substantive quality. Each Director has worked extensively to display his or her passion for the topic areas in one comprehensive study guide. The document you are about to read is the product of countless hours of detailed research and careful editing. HMUN is known for its unparalleled substantive excellence, and I am confident that with the help of this guide and your own self-guided research, you will be well prepared to tackle the challenging questions that will arise in committee in March.When approaching the study guide, make sure to pay special attention to the QARMA (Questions a Resolution Must Answer). Within each topic area, these are the central issues that are crucial to ad-dress in debate. While preparing, make sure to also reference our Rules of Parliamentary Procedure, as we run committees based on a set of rules that are unique to HMUN China. Keep in mind that the rules are subject to minor changes leading up to the conference at the discretion of the Secretariat and the Committee Directors. If you have any questions or concerns about your guide or the com-mittee, please do not hesitate to contact your Directors. They are incredibly excited to meet all of you and will be more than happy to answer your questions and provide further guidance for your research leading up to the conference.On behalf of the HMUN China staff and WEMUN team, I’d like to once again extend my warmest welcome to HMUN China 2011. Good luck with your research and preparation, and I look forward to seeing you in Shanghai in March!Sincerely,Kerry F. YangSecretary-GeneralHarvard Model United Nations China 2011secgen@h arvarD M oDel U niteD n ationSc hina 20113Dear Delegates,Welcome to the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees at Harvard Model United Na-tions China 2011. I am extremely honored to serve as your director this year and hope you are look-ing forward to conference with as the same amount of excitement. I chose the topics of Host Nation Responsibility and Permanent Refugee Camps as I believe they will challenge you to tackle some of the most difficult, yet under-addressed, problems facing the refugee community. Approaching these topics will require you to understand the issues as a whole as well as their more intricate and often more complicated components. While finding solutions will certainly be difficult, I hope you find the process rewarding and I look forward to hearing your ideas and eventual solutions.To tell you a little about myself: I’m a senior at Harvard, class of 2011. My family recently moved back to my original home town of Chicago, after living in Singapore for two years. I was involved in Model United Nations throughout high school and hope to combine my passion for international relations with my other passion – science. This combination of interests led me to concentrate in Molecular and Cellular Biology, following a premedical path, as well as pursuing a citation in Chi-nese. I am currently applying to medical school and I hope to combine medicine and international relations in practicing medicine overseas as well as working on international health policy. While my academic studies have always been an important part of my life, the experiences that have most in-fluenced me are those outside of the classroom, in my extracurricular activities. I highly recommend throwing yourself into activities outside the classroom whether within the local community or with friends; these experiences are the ones you’ll learn the most from and remember years down the road. The two topics I chose for committee are ones people often take for granted, assuming they’ll be resolved as other issues are addressed. However, these problems are urgent issues in their own right and cannot afford to be overlooked. First, they move beyond the scope of humanitarian crises to integrate economic, environmental, and judicial issues as well. Moreover, they’re essential in realiz-ing that refugees’ problems do not stop at the border of camps and host nations, but extend beyond them. The security of camps and host nations is often unreal, or at least too idealized. By examining these issues in greater detail, we can get at the heart of many problems refugees face, even brining into question much of the discussion surrounding the famous three ‘durable solutions’ that have been posed as the ultimate answers to refugee crises.Please do not hesitate to contact me with any questions or concerns you may have about conference, the topics, anything – feel free to just send me an e-mail any time! I expect this committee will be challenging, but extremely successful and rewarding. I look forward to meeting you all and sharing this great experience!Always,Lynn JiangDirector, United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees Harvard Model United Nations China 2011lynnj@h arvarD M oDel U niteD n ationSc hina 2011INTRODUCTIONWelcome to the Study Guide for the UN High Commissioner of Refugees, HMUN China 2011! This guide should provide you with background information on the committee and its topics, creating a platform for you to go off of in conducting individual research. While just a basic overview, I hope that you find it helpful in terms of getting you familiar with the topics and stimulating ideas to bring up in debate when we finally meet.Our two topics for this committee are Host Nation Responsibilities and Permanent Refugee C amps. Discussing these topics takes the committee’s mandate to protect and aid refugees to the next step, addressing aspects of the refugee issue that the international community has either overlooked or finds extremely challenging to resolve. Most recent discussion and action has focused around removing refugees from conflict and settling them into safe camps or countries. While important, equally important aspects are the problems refugees face after they are placed in a more secure place. Despite promises of new chances and opportunities, life in camps or a new country is not easy and comes with challenges of its own. Thus, by addressing these two topics, we will hopefully help bring them more into the limelight as well as work together in order to resolve problems that have persisted for over several decades.Most of all, these topics will force you to think about problems facing refugees in a new way, examining the intricacies and complexities from a new perspective. While writing an effective resolution is certainly an important focus of conference, it is also my hope that you will walk away from committee having enjoyed your time there and having learned from one another.HISTORY OF THE COMMITTEEOn 14 December 1950 the United Nations General Assembly established the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees . The founding of UNHCR was in response to the large number of people displaced in Europe as a result of WWII and the committee replaced the International Refugee Organization (IRO) which had been established directly after the war . The UNHC R was supposed to complement already established international laws, specifically the 1951 C onvention relating to the Status of Refugees . The Convention defines what a refugee is and the other rights and obligations refugees have under host governments . Since the 1951 C onvention specifically addressed the WWII European C risis, its focus was too narrow to address the changing realities of the refugee situation.C onsequently, it was amended by the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees which lifted many of the previous time and area restrictions and changed the definition of a refugee to be more geographically inclusive . As it currently stands, the UNHCR Statute defines the committee’s mandate to protect and provide assistance to refugees as well as cooperate with governments to seek permanent solutions for them .The UNHCR has grown over the years and is now responsible for more refugees than any other period since WWII. However, the UNHCR is often limited by state governments since governments sit on the executive committee of the UNHCR and are essential in donating funds and granting permission to work within national boundaries . Funding has become a large issue. In the mid-1970s, the UNHCR’s resources where able to keep pace with the increasing number of refugees, however while expenditures increased from US $8 million in 1970 to almost US $1,167 million in 1994 and stayed approximately at that level despite growing need .Currently, the UNHCR is often called upon to aid in the increasing number of situations where refugees do not meet Convention definitions . The UNHCR has expanded its efforts to aid internally displaced persons, who are not included under the Convention’s definition of a refugee and thus are often overlooked. For the most part, the UNHCR promotes the right to return home, seek asylum, integrate locally, or resettle in a third nation . However, it most actively presses for the need to return refugees to their countries of origins in order to prevent future refugee- producing events . The UNHCR has helped establish regional works such as 1969 OAU Refugee C onvention in Africa and the 1984 Latin American Cartagena Declaration . It was also integrally involved in operations after the 2004 Asian tsunami and the 2005 Pakistan earthquake as well as many of ongoing conflicts in places such as Sudan .44The UNHCR reports verbally to the ECOSOC and submits written reports to the General Assembly. The UNHCR can only seek contributions with the approval of the GA. An Executive Committee also meets annually to approve the programs and guidelines . In order to implement any plans, the committee must work under the guidance and limitations imposed by these groups as well as work in conjunction with state governments and NGOs.TOPIC AREA A: PERMANENTREFUGEE CAMPSS tatEmEnt of thE P roblEmAs conflict, instability, and disasters lead to violence and poverty around the world, entire populations abandon their homes, seeking refuge elsewhere. In order to effectively handle the large influx of people and efficiently provide relief, host nations and organizations such as the UNHCR often establish refugee camps. While providing immediate emergency aid and shelter, these camps are meant be temporary structures, to give aid and protection until the establishment of a more permanent solution. While it is understood that finding a solution may take time, many camps have moved far beyond this point, now “…boast[ing] a new quality: a ‘frozen transience’, an on-going lasting state of temporariness.” Rather than remaining only as long as necessary, some refugee populations live in camps for many years, with generations of refugees who live and die in camps, never knowing life outside their borders.In the period from 1993 to 2003, long-term camp situations increased from 45% of refugee camps to 90%. At the end of 2003, the United States C ommittee for Refugees and Immigrants estimated that approximately 8 million people, 2/3 of refugees, remained in prolonged refugee situations. Moreover, in the same period of time, the average duration refugees remained in camps increased from 9 to 17 years. Some camps develop semi-permanent structures with clinic, schools, and libraries indicating a permanent nature to the camp and no sense of the refugees moving any time soon. As one refugee said, “we need help to get out of the camp. I don’t think we shall manage it soon. That is the worst of living here, you never know a thing…” Life in camps becomes a waiting game of uncertainty; refugees learn to settle in for the long haul.CAMP CONDITIONSBecause camps are supposed to be an emergency response, little thought is put into the long-term. Shelter stability and supplies are typically insufficient to last for extended periods of time. Refugees often express disbelief and incomprehension at the small amounts of food they are given. One aid worker in a Guinean camp wrote, “When the ‘old’ refugees first arrived, they received up to 12 items in the food basket. Today, they receive only three. In addition, there are widespread complaints that the food rations are insufficient in terms of quantity and do not last…” Cuts in food amounts result from lack of supplies rather than reduction in need. In Kenyan camps, for example, a shortage of funds led to a 30% reduction in rations; the number of calories given to each person fell from the recommended 2,166 kilo-calories to 1,400 kcal per day. Considering that the minimum intake a person should healthily take in is 1,200 kcal, this is barely enough nutrition for an individual – especially for growing children and nursing mothers that live in the camps. This issue is aggravated by the fact that while camps turn into permanent establishments over time, aid remains continually difficult to obtain and refugees must live on the same or less aid, despite growing need. In fact, as time goes on, many governments and organizations lose interest in the plight of the refugees, moving onto more recent “hot topics.” Thus, camps lose a lot of their initial aid.C onsequently, the conditions in camps rarely provide the safety and better life they initially promise. Malnutrition, limited resources, and violence are common problems. Camps can rarely afford sufficient police, and residents often go unprotected, becoming victims of violent hostility or rape originating from both in and out of the camp. Undefended camps become greater targets to groups looking to raid camps for their supplies, some of which can be hard or impossible to obtain in poorer host nations. In places such as northern Uganda, western Zambia, and northern Namibia, these raids are run by rebel groups. This in turn leads to a spillover of violence from surrounding areas into host nations. The problem becomes worse when the rebel groups are the same people the refugees fled from in the first place.5Camps can prove equally taxing on the host nations as they are on the refugees. The presence of camps places heavy demands on the surrounding environment, taking up land and trees for shelter and cultivation. In farming, the refugees take short-term perspectives, taking what they need for the immediate time but not considering the long-term impact of their actions on the land. The constant need of the refugees drains often scarce food, water, and fuel, leading to animosity from native populations who must compete for the same resources. Moreover, camps can drain the host country’s administrative and financial resources, contributing to increased insecurity. When these nations appeal for assistance, the international community’s reluctance to aid host nations further reinforces the idea that refugees are a burden, leading nations to place refugees in camps rather than attempt to find better solutions. The combination of these factors creates citizen and governmental opposition towards refugees, only increasing the potential for violence and problems within camps. These concerns are the foundation of nations’ rationale for directing resources towards the native population and keeping refugees only in camps where international agencies can manage them. As long as camps offer basic support and appear uncomplicated compared to other solutions, they inevitably become the preferred method of dealing with refugee populations.Permanent camps are evidently an issue, placing strain on both the refugee populations and host nations. Spending money on basic maintenance of camps does not contribute to finding a proper solution, but only helps prolong the situation and perpetuate the problem. In order to address the world refugee crisis and work towards viable solutions, the problem of permanent camps must be resolved, both aiding in protecting these populations as well as establishing an important foundation for permanent solutions.h iStory of thE P roblEmThe problem has existed since before the 1980s, when long-term camps became the norm to deal with the refugees fleeing conflicts around the world. Apart from camps, however, the international community failed to provide other solutions. Other than these facts, it is difficult to truly understand when the problem began. It is an issue created by time – the terrible conditions in camps and the difficulty of finding a solution increases as camps settle into a more permanent status. What we can examine, however, are some of the past ideas about permanent camps and methods of dealing with the problem to understand some of the issues that have compounded and examine potential solutions.HISTORY OF CAMP ESTABLISHMENTThe idea of durable solutions arose with the UNHCR Statute, emphasizing repatriation, assimilation into new countries, and resettlement as potential durable solutions which should be promoted. When looking back at the original C onvention, however, nothing was directly mentioned about solutions to permanent camps making combining the Statute with the Convention difficult – the only mention is Article 33 specifying that refugees should not be forced back to their countries of origins. In fact, the C onvention’s writers thought that integration would automaticallyrise to be the best possible solution, one 1950 reportsaying “the refugees will lead an independent life in thecountries which have given them shelter…the refugeeswill no longer be maintained by an internationalorganization.”During the Cold War, protracted refugee situationsand the establishment of more permanent refugee The chart indicates the distribution and type of cases aroundthe world.6Specialized Agencies 6camps were brought more fully to the public’s attention. The new unstable economic and political conditions in many of the West’s Cold War enemies pushed integration and resettlement further to the forefront as the preferred solution over repatriation. The international community saw refugees as passive recipients of aid, and placing them in camps was considered the ‘fashionable’ model that would help change the countries they were placed in. Accepting this idea, African nations began to force refugees into camps, but experts began to realize that the dependency that developed was extremely detrimental – the nations that received the most aid did not improve, whereas those that had more self independence did.As conflicts intensified, host and resettlement nations became less and less willing to accept refugees and these solutions became less feasible. As a result, in the 1980s the refugee situation turned to the establishment of long-term – eventually permanent – camps. From the mid-1980s, repatriation was focused on as the only possible solution to deal with the African refugee problem – even if it was not desired by either countries of origin or the refugees themselves. African nations felt the refugees placed a burden on their declining economies, a burden that was not equally shared by those with better resources. Moreover, some politicians found they could capitalize on anti-refugee sentiments in order to gain support. C onsequently, repatriation became the dominant solution, since any other attempts such as local integration and self-reliance were ineffective. However, repatriation began to prove unfeasible, even in situations when the country of origin was stable. Some refugees lacked the money and resources to make the journey home. Scholars explain the persistence of camps as a combined result of resistance to integration and the difficulty of repatriation. Beyond prolonged camp existence there were no other suggestions for alternatives. Only the end of the C old War brought new hope for resolution and the preferred choice of a durable solution turned to voluntary repatriation. In fact, the UNHCR declared 1992 as the “Year of Voluntary Repatriation”. The lessons from the C old War transferred to later situations.HISTORICAL EXAMPLESAfter Eritrean independence in 1992, some of the original refugees still remained in Sudan. Due to the troubles and conflict that took place in Eritrea, repatriation was delayed in order to converse with the new government and improve conditions. In 1993, a new program costing $260 million was developed by the UNHC R and Eritrean government to improve integration and repatriation and the plan was implemented in November 1994. Initially considered successful, the movement stalled as a result of unstable conditions between Sudan and Eritrea – fighting and a loss of positive diplomatic relations.The scale of the crisis also played an important role in finding a long-term solution. Perhaps due to costs, the larger the problem and the longer it had been going on, the more difficult and challenging it was to resolve. Moreover, nations found that larger issues took at least several years to achieve a solution, sometimes creating difficulties for those wishing to see immediate results with limited resources.An interesting historical comparison is that of the Afghan refugees in both Pakistan and Iran prior to 1992. By the mid-1980s, when permanent refugee camps became the norm, there were 2.3 million refugees in Iran and 3.2 million in Pakistan. The nations initially took two different approaches to deal with the populations. Before 1992, Iran allowed the refugees to have general freedom and allowed them to work and integrate into the local communities. They even had access to many of the same resources and services as the citizens. Thus, many of the refugees, in fact less than 10 percent, remained in camps. Comparatively, the refugees in Pakistan were extremely limited in their opportunities and depended on the camps for their main source of support. Thus the majority of the Afghan refugees lived in camps and could not be self-reliant. The two different treatments meant that integration in Pakistan was not seen as a possible solution as it drained resources whereas in Iran the refugee population was seen as an economic benefit.As a result of this, the UNHCR became more involved in Pakistan, coordinating aid and helping maintain and improve the camps. In fact, the UNHCR provided 50 percent of the aid by the mid-1980s, unfortunately only compounding the problem since the outside assistance made camps less expensive than integration. In Iran, the UNHC R did not provide assistance until 1983 and even then it was only a small amount. Everything changed in 1992, however, when the Iranian government reversed the integration policy and took away rights in order to place refugees back into camps. This was78Specialized Agencies8due in large part to rising costs of integration and worsening economic stability in Iran. The situation began to resemble the conditions in Pakistan and when the government fell, repatriation became the chosen solution; in 1993, repatriation was actually forced rather than voluntary, however. In this situation, similar to that occurring in current permanent camps, the issue became a compounded result of the refugees losing ties with their home country, host nations resenting the refugee population, and donor nations unwilling to help out. Even when the cost of repatriation was lowered a little, it was still more expensive than staying in the camps. In order to ensure success, the government did not want to support repatriation that was not assisted by international aid.ECONOMIC CONCERNSIn other places, the UNHC R had very littlebackground in implementing programs to improveagricultural self-reliance as well as to find new sourcesof income. Without this ability, it was difficult toeliminate many of the economic constraints placed on the refugee populations, constraints that forced them to rely heavily on others rather than learn to provide for themselves. Some researchers argued that the UNHCR enacted long-term programs that did not effectively adapt to the changes in the refugee problems. Essentially, the implemented solution only focused on immediate assistance as a result of a lack of resources. Evidently, the proposed solutions historically proved neither feasible nor successful in certain situations.To respond, donors emphasized new aid programs to aid the host nations and improve infrastructure in areas of settlement. While donor nations meant the programs to help integrate refugees, host nations only saw it as an opportunity to gain more aid for their own purposes while still keeping the refugees separated from the nativepopulation. The combinations of all the historical efforts lead to our current situation. Nations now seethe refugees’ displacement and dependency as the normand accept it rather than recognizing it as something thatdesperately needs to be resolved.c urrEnt S ituationMany of the historically based problems with permanent refugee camps still exist today. It is the compounding of these problems that elevates the issue to its current situation. Camps stand as physical symbols of the refugee crisis and become ground zero for security, economic, and political problems.The following includes several specific examples in order to gain a better understanding of some more detailed issues that arise in different camps around the world. These examples are often specific to that nation or region, but include many of the general issues that arise with the presence of permanent camps. Please note that these are only some examples, some more extreme than others, and in reality the refugee population enjoy varying degrees of conditions, with some better than others.BHUTANSince 1989, over 103,000 Bhutanese refugees have resided in seven refugee camps in Nepal and a solution is still pending. In September 2003, the High Comissioner emphasized that finding a solution for the Bhutanese wasThe setup of an example refugee camp.。

人权保护案例难民权益与国际人道法的调整难民问题是当代世界面临的一个重要挑战,也是保护人权的核心议题之一。

随着全球政治和经济环境的变化,越来越多的人不得不背井离乡,寻求庇护和保护。

然而,在难民权益保护方面,国际社会和国际人道法在不断调整和完善。

本文将以一些经典案例为例,探讨难民权益保护与国际人道法的关系,并分析国际人道法在调整中的意义与影响。

一、案例一:《公民权利和政治权利国际公约》与亚洲难民问题亚洲地区是全球难民问题的热点之一。

在亚洲难民问题中,一系列案例成为了对人权保护机制的检验。

《公民权利和政治权利国际公约》是国际人权法律框架中的重要组成部分,它确保了个体享有自由、公平的审判、言论自由等基本权利。

亚洲国家如缅甸、中国和朝鲜等,面临着政治不稳定、人权问题等难民大量涌入的情况。

在这些事件中,国际人道法的调整和完善成为了保护难民权益的重要保障。

二、案例二:欧洲难民危机与《日内瓦难民公约》的解读欧洲难民危机是近年来引起广泛关注的事件之一。

从2015年开始,大量难民涌入欧洲,引发了一系列政治、社会和经济问题。

《日内瓦难民公约》是保护难民权益的重要法律文件,其中规定了难民的定义、权利和义务。

然而,欧洲难民危机对这一公约提出了挑战,也促使了国际人道法的调整和解读。

例如,欧盟对难民配额系统的引入,旨在分担各国的难民压力,同时也提醒了国际社会对《日内瓦难民公约》的重新解读和适应。

三、案例三:联合国难民署与难民保护的责任分工联合国难民署(UNHCR)是联合国系统中负责难民问题的重要机构。

难民保护的责任在国际社会中存在不同的分工和合作方式。

在一些重大难民危机事件中,联合国难民署与各国政府及其他非政府组织密切合作,共同致力于难民权益的保护与救助。

这种分工模式和合作机制使联合国难民署成为国际人道法调整中的关键参与者,也为保护难民权益提供了重要的支持和指导。

四、案例四:国际人权法与难民权益的平衡国际人权法在保护难民权益方面扮演着重要角色。

联合国系统最大的多边无常援助机构

联合国系统最大的多边无常援助机构是联合国难民署(UNHCR)。

联合国难民署是联合国系统中最大的多边无常援助机构,它致力于保护和支持全球难民,以及其他受到迫害的人们。

联合国难民署的使命是保护和支持全球难民,以及其他受到迫害的人们,并为他们提供安全和尊严。

联合国难民署的工作范围涵盖了从提供紧急救援到支持难民重返家园的各

个领域。

联合国难民署的工作主要集中在提供紧急救援、支持难民重返家园、改善难民居

住环境、改善难民的教育和就业机会、改善难民的健康状况、改善难民的法律保护等方面。

联合国难民署的工作受到全球各国政府的支持,它们提供了大量的资金和物资,以支持联合国难民署的工作。

此外,联合国难民署还得到了许多国际组织和民间组织的支持,他们

提供了大量的志愿者和资金,以支持联合国难民署的工作。

联合国难民署的工作取得了巨大的成功,它为全球难民提供了安全和尊严,并为他们提供了更好的生活条件。

联合国难民署的工作也为全球难民提供了更多的机会,使他们能够重

新定居,重新开始新的生活。

总之,联合国难民署是联合国系统中最大的多边无常援助机构,它致力于保护和支持全球难民,以及其他受到迫害的人们,并为他们提供安全和尊严。

联合国难民署的工作受到全球各国政府和国际组织的支持,它们提供了大量的资金和物资,以支持联合国难民署的工作。

联合国难民署的工作取得了巨大的成功,为全球难民提供了安全和尊严,并为他们提

供了更好的生活条件。

联合国相关知识点联合国(United Nations)是人类历史上最具权威和影响力的国际组织。

它成立于1945年6月26日,总部设在纽约,现有193个成员国。

联合国主要任务是维护国际和平与安全、促进全球合作与发展、保护人权、应对全球性挑战等。

本文将介绍几个联合国相关的知识点,让读者更好地了解联合国。

一、联合国的组成机构联合国共设有六个主要机构,分别是:1.大会:联合国最高权力机关,每年在纽约总部召开一次会议。

2.安理会:负责维护国际和平与安全,15个成员国,5个常任理事国(中国、俄罗斯、美国、英国、法国)拥有否决权。

3.经社理事会:负责促进全球合作与发展,54个成员国,每年在纽约总部召开一次会议。

4.国际法院:联合国主要司法机构,总部设在海牙,负责解决国际法律争端。

5.秘书处:负责联合国日常工作的执行机构,总部设在纽约。

6.人权理事会:负责保护人权,47个成员国,每年在瑞士日内瓦召开多次会议。

二、联合国的成员国目前联合国有193个成员国,其中包括全部主权国家。

每个成员国都有一个代表来参加大会会议,并对大会决议进行表决。

成员国在国际事务中有平等权利和义务,而联合国则负有世界和睦和人类福祉的使命和责任。

三、联合国的宗旨和原则联合国的宗旨和原则确立在《联合国宪章》中。

其中宣示了,维护国际和平与安全、促进全球合作与发展、保护人权、实现平等和主权国家的互相尊重等基本宗旨。

而宪章还提出了一些重要的原则,如国家的平等、不干涉内政、和平解决国际争端、禁止使用武力等。

这些宗旨和原则是联合国工作的基石和指导思想。

四、联合国的全球行动联合国在维护国际和平与安全、推动可持续发展、提高全球健康水平、保护人权等方面有着丰富的全球行动。

下面列举几个具有代表性的全球行动:1.维和行动:联合国拥有一支维和部队,由各成员国提供兵员和物资进行维和行动,目的是解决冲突、维护和平。

自1948年起,联合国先后进行了72次维和行动。

2.气候行动:联合国秘书长设立的气候变化秘书处负责推动世界各国应对气候变化,制定《巴黎协定》等重要文件。

国际主要救援组织介绍国际主要救援组织介绍UNDP(联合国开发署,United Nation Development Program),主要协助受灾国进⾏灾前长期防灾减灾和灾后的恢复⼯作。

UNICEF(联合国⼉童基⾦,The United Nations Children’s Fund),主要负责灾区紧急时段的妇⼥和⼉童的⽣活条件的援助⼯作,适时提供灾区妇⼥和⼉童的情况的快速评估。

UNHCR(联合国难民署,United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees),主要负责紧急时段建⽴难民营,协调国际援助和难民的再安置。

OCHA(联合国⼈道主义事务协调办公室,United Nation Office of Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs ),主要负责政策发展、⽀持⼈道主义事务、⼈道主义应急响应的协调⼯作。

UNESCO(联合国教科⽂组织,United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization),通过教育、科学和⽂化促进各国合作,对和平和安全作出贡献。

WHO(世界卫⽣组织,The World Health Organization ),主要负责紧急时段卫⽣健康信息的收集管理;卫⽣健康状况的快速评估;建⽴⾼层次的应急卫⽣协调组织⽹络;在总部和各分区加强应急响应基⾦。

WFP(世界粮⾷组织,The World Food Program),主要负责紧急时段的⾷品援助;准备后勤和运输⽅案;建⽴⾷品通道、仓库、路线和分发点。

IFRC(国际红⼗字和红新⽉联合会,The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies)是各国红⼗字会和红新⽉会的国际性联合组织,宗旨是在战争中⾏善和通过⼈道⼯作维护和平。

关注难民——联合国难民署介绍宋菁宋菁,1995年毕业于华中理工大学外语系,随后进入浙江电视台工作。

1998年至2000年在北京广播学院电视系攻读新闻学硕士学位,毕业后进入联合国难民署驻华代表处任驻在国新闻官员。

1. 难民国际保护的发展过程联合国难民署并不是世界上第一个从事难民保护的机构。

在它之前,还有像联合国救济及复原管理办事处和国际难民组织这些机构处理过难民事务。

但成立于1950年12月14日的联合国难民署是第一个全面处理难民事务的机构。

1951年联合国关于《难民地位的公约》签订,这两件事第一次在国际法的范畴内对难民进行援助,同时为他们提供保护。

在难民署成立的时候,也就是在1950年的时候,它的职责是保护二次大战后欧洲的难民。

但是在后来,难民危机发展到全世界各地,成为一个全球性的危机。

联合国难民署由联合国大会成立,同时也向联合国大会汇报工作。

联合国难民署的大部分资金来自各国政府的捐助。

到2002年1月l日,难民署一共在114个国家设有办公室,一共有5500个工作人员,84%都是在一线工作的,其中一些是比较偏远的地区。

我们这里写了,我们现在的高级专员是吕贝尔斯。

他是二战以后荷兰任期最长的首相。

那么大家谁知道我们前一任高级专员是谁?知道的人不少,是绪方贞子。

吕贝尔斯是在2001年1月1日就任的,他由联合国大会任命,同时通过联合国经济和社会理事会向联合国大会汇报工作。

难民署的预算由我们的执行委员会(联合国难民署执行委员会)来批准。

这个执行委员会目前由57个国家共同组成。

我们中国是其中的一个。

2. 联合国难民署做什么样的工作?首先大家看一下这个UNHCR。

谁知道这个UNHCR是什么的缩写?对,UN是United Nations。

HCR呢?就有困难了。

这R呢,就是Refugee,难民,是吧?HC是High Commissioner,高级专员,所以我们的全称是联合国难民事务高级专员署。

顾名思义,我们是一个联合国的机构。

我们这个机构的立身之本就是:我们是一个非政治性的、人道主义的机构。

强调这一点,是因为在二战以后在冷战时期难民署需要在两大阵营里工作。

在这样的情况下,你必须强调你是非政治性的,要不然你就没有办法开展工作。

联合国难民署的职责呢,就是为难民提供国际保护,同时寻求永久解决关于难民的问题的方法。

除此之外,我们的一些主要的工作还包括为难民提供人道主义的援助。

我想大家可能对这方面都熟,就是老能听见看见难民署提供居住的地方,给难民发食物什么的。

这是我们一方面的工作,给难民提供基本的人道主义援助。

联合国难民署关注的人,就是我们为哪些人提供帮助?在2002年年初的时候,我们所关注的人数是1980万,这相当于全世界每300个人中就有一个是我们关注的人。

这个数字比去年有所减少。

减少的原因是什么呢?因为阿富汗问题已经基本得到解决,阿富汗人已经开始回到他们的家园。

我们所关注的人数,在1995年达到高峰,是2700多万,2001年是2100多万,今年是1900多万,又减少了一些。

谁是我们所关注的人?从我们的这个名称——UNHCR——可以看出难民是我们最主要的关注入群,占60%。

接下来呢,是寻求避难者。

我们这个机构所说的难民,和大家所说的难民(有些是灾民),并不完全是同样的概念,是需要法律认定的。

寻求避难者,就是还没有被认定为难民的人。

还有返回者,就是返回到祖国以后的这些原难民。

比如阿富汗人,他们回去之后,难民署还要继续给他们提供援助,并不是在他们回去之后援助就结束了。

接下来呢,很重要的一块叫做国内流离失所者,他们跟难民有什么关系呢?待会儿还会给大家讲,他们也是我们工作很重要的一个对象。

剩下的就是其他人,像无国籍人等等,跟难民境况有一定的相似。

难民分布在什么地方?大家看到的国内的报道,比较侧重于非洲难民。

一提起难民,就想起非洲特别瘦弱的小孩什么的,像《黑镜头》上拍了好多非洲难民的照片。

大家听到难民就跟非洲联系到一起。

但从这个图上,大家可以看出,亚洲的难民是最多的。

亚洲的难民数差不多是非洲和欧洲难民数之和。

从去年的数字上来看呢,亚洲、非洲、欧洲难民数有点相近。

阿富汗危机之后,亚洲的难民数目急剧增加。

明显地,亚洲的难民占了绝大多数。

从这个表(难民来源国),大家就知道为什么亚洲的难民占绝大多数了。

阿富汗的难民就差不多占了亚洲难民一半。

接下来是布隆迪、伊拉克、苏丹、安哥拉、索马里、波黑、民主刚果、越南和厄立特里亚。

越南的难民其实很多都居住在中国。

联合国难民署在中国一共有两个办公室。

一个是在我们所在的这个驻华地区代表处,还有一个是香港办公室。

最早在中国设置难民署是在1978年到1979年间,那时有很多的越南难民流落到东南亚各国。

其中有26万到了中国大陆。

在这一段时间,难民署在中国大陆,同时也在香港设立了临时办公室来应对这种难民潮的涌入。

1997年北京办公室升级成为地区代表处,主要负责中国大陆、香港、澳门和蒙古的难民事务。

现在介绍一下援助对象。

我们的援助对象分为两部分,一部分是印支难民;第二部分是个别难民,这些人主要是一些留学生。

他们离开自己的国家之后,国内局势发生变化,他们没法回去,所以就被迫留在我们国家成为难民,包括伊朗、伊拉克、阿富汗和一些非洲国家来的难民。

我们不仅给他们提供一些必要的援助,同时也寻求解决他们问题的方法。

(关于难民的问题解决方法,待会再向大家介绍)。

中国政府允许他们暂时留在中国,但这不是一种长期的对他们的安置。

印支难民,他们和我刚刚说的这种城市难民不太一样。

从1978年到1980年,中国是当时所有东南亚国家中,惟一一个对他们提供大批量的一次性安置的国家。

这26万人是一个相当沉重的负担,但中国把他们留下来了,并将他们永久地安置在广西、广东、云南、海南、福建和江西。

他们的待遇和中国公民基本一样,只是他们没有中国国籍,所以没有选举权和被选举权。

从1981年到1982年,中国政府又接收了约3700名老挝难民,把他们安置在云南省。

26万人,是一个相当大的数目,再加上后来生育的,已经达到29万多人了。

1994年,联合国难民署开始实行周转金贷款计划。

在1994年之前,联合国难民署所有的钱都是援助的,就是不需要归还的。

1994年之后,难民已经取得一定程度的自立,所以这个援助就以周转金贷款的方式来进行。

这个周转金贷款计划就是说,联合国难民署提供一种低息的贷款来给当地的企业,发展一些小的加工业、农业。

获得这个低息贷款的前提条件就是雇佣一定比例的印支难民作为他们的员工,这样就可以帮助一些生活在贫困线以下的难民家庭。

在1999年之后,周转金计划就不再投钱了,主要是靠前期的投资和利息来维持运转。

目前有66个周转金贷款计划项目在运行。

联合国难民署所做的另外一种援助是职业培训。

职业培训主要面对他们的第二代,因为年轻人自立以后,可以养活他们的父母、他们的家人。

目前在除江西(江西安置的难民人数比较少)以外的5个省区都有职业培训中心。

职业培训的内容就是像理发、修理电器、厨师这样的。

受训人大多数都可以通过职介中心的就业网得到工作。

自愿遣返。

在1991年到1996年,有3700名老挝难民在联合国难民署和中国政府的帮助之下,回到了他们自己的国家。

联合国难民署在这个过程中,主要负责他们的交通,同时还提供遣返的补助金。

难民署在香港。

在1975年到1995年之间,差不多在20万越南难民在香港。

经过一段时间之后,他们中的大部分人都被安置到第三国,还有很多人返回了自己的家园。

剩下的1400人于2000年2月正式在香港就地融合。

2000年7月望后石难民营的关闭,标志着越南难民和船民这一段历史在香港正式结束。

下面希望大家能够向难民提供一些力所能及的帮助吧。

对难民有两种观点。

一种观点是难民是负担。

比如我们花那么多的钱对难民进行帮助,给他们提供衣食住行;另一种认为难民对我们是一种威胁,他们可能威胁到我们自己的生存。

其实我们应该换一种角度看。

难民是和我们一样的人,他们只是比较不走运,遇到了这样那样的困难,而不得不背井离乡。

所以我希望大家能在需要的时候对难民伸出帮助之手。

他们完全有可能成为我们社会的财富。

难民署经常用爱因斯坦来进行宣传。

其他的杰出难民还有弗洛伊德、基辛格、科马内齐等,有很多大家耳闻目睹的人。

如果他们没有得到帮助的话,他们也无法获得成功。

试想一下如果全世界都把背转向爱因斯坦,爱因斯坦会怎么样?3. 为难民提供国际保护国际保护究竟是一个什么样的内涵呢?保护难民,就是接受难民资格的成立。

提供国际保护主要包括两方面的内容:一是保护难民的避难权,保障难民不被强迫送回他有理由畏惧遭到迫害的国家,即“不推回原则”;二是为难民的基本人权提供保障,使难民的经济、社会、文化、工作、教育、健康等权利得到保障。

究竟谁来提供国际保护?由谁来确定难民的资格,确定他是不是难民?难民公约的签约国首先有责任来确定难民的资格。

我们把这一部分难民叫做“公约难民”。

公约难民享有签约国所赋予他的所有权利。

另外联合国难民署根据其职能来确定难民,这一部分难民叫“章程难民”。

难民署给这部分难民一些资助并保护其不被“推回”。

有这样一种说法:对于难民本身而言,作为一个公约难民他享受的权利可能会多一些,因为签约国家一般赋予公约难民相当于外国人的待遇。

下面我想介绍一下寻求国际保护的一系列法律的依据。

首先我要讲的是“不推回原则”。

这一原则是国际习惯法,就是说不论一个国家是不是难民公约的缔约国,他都有义务执行这个不推回原则。

简单地说,如果有一个寻求庇护者因为担心遭到迫害逃到了另一个国家,那么这个国家有义务不把他推回到他所担心受到迫害的那个国家。

这一原则是一个已被联合国成员国普遍接受的习惯法。

提供国际保护的法律依据,一个是联合国难民署的章程。

这个章程赋予了难民署提供国际保护的职能。

第二个就是《关于难民地位的公约》。

这是一个最有力的法律依据,也是最权威的。

这个《难民地位公约》是1951年通过的。

1967年通过了《关于难民地位的议定书》,《议定书》相对于《公约》来说有一点不一样:它取消了《公约》关于地域和时间的限制。

再一个就是《非洲统一组织公约》,这是区域性的公约。

区域性的公约只是对这个区域组织的成员国具有法律约束力。

但是它非常重要,也具有现实意义。

它会影响到非洲以外的其他国家。

在这个公约里面,难民的定义得到了扩大。

还有就是1984年《卡塔赫纳宣言》,它主要是对拉美地区的国家有约束力。

最后一个就是联合国大会所作的决议。

联合国难民署是联合国大会授权的一个组织,联合国大会的决定可以授权难民署履行一些职能。

难民署最初的职责是保护难民的。

“流离失所者”实际上并不是难民。

但是这一部分人因为国内的动乱,虽然没有离开他的祖国,但在自己的国家内处于一种失去保护的状态,他的国家不能对他实施有效的保护。