新发展大学英语阅读与写作4课文翻译Nine_Years_for_A_and_B_(九年遂成AB部)

- 格式:doc

- 大小:37.00 KB

- 文档页数:3

Unit 1享受幽默——是什么使人开怀?[1]The joy of laughing at a funny story is universal, probably as old as language itself. But, what is it that makes a story or a joke funny?1 听了一个有趣的故事会发笑、很开心,古今中外都一样。

这一现象或许同语言本身一样悠久。

那么,到底是什么东西会使一个故事或笑话让人感到滑稽可笑的呢?[2] As one who has enjoyed humor since I first recognized it, I've made an attempt to explain and discuss humor with students in such diverse cultures as Latin America and China. I've done some serious thinking about funny stories. It has been a labor of love!2 我是第一次辨识出幽默便喜欢上它的人,因此我曾试图跟学生议论和探讨幽默。

这些学生文化差异很大,有来自拉丁美洲的,也有来自中国的。

我还认真地思考过一些滑稽有趣的故事。

这么做完全是出于自己的喜好。

[3]Why is it that several students in a class will fall out of their chairs laughing after I tella joke while the rest of the students look as if I've just read the weather report?[N]Obviously some people are more sensitive to humor than others. And, we recognize that some people tell jokes very well while others struggle to say something funny. We've all heard people say, "I like jokes, but I can't tell one well, and I can never remember them." Some people have a better sense of humor than others just as some people have more musical talent, mathematical talent, etc. than others. A truly funny person has a joke for every occasion, and when one is told, that triggers an entire string of jokes from that person's memory bank. A humorless person is not likely to be the most popular person in a group.It is reasonable to say that the truly humorous individual is not only well liked, but is often the focus of attention in any gathering.3 为什么听我讲完一个笑话后,班上有些学生会笑得前仰后合,而其他学生看上去就像刚听我读了天气预报一样呢?显然,有些人对幽默比别人更敏感。

Nine Years for A and B九年遂成AB部(1)克利斯朵夫·里克斯[1]著敏译塞缪尔·约翰逊博士[2]是最伟大的词典编纂人。

詹姆斯·默雷则是编写了最伟大词典的人:从1879年直到1915年去世,他把大半生都献给了《牛津英语大词典》的编纂工作。

约翰逊博士比谁都更有资格说词典编纂者是个“无害的苦工”[3]。

他知道词典编纂包含的远远不只是苦工,而且其单调乏味程度简直难以想象,即使词典编纂者也有幸无法事先清楚预估。

所以词典编纂者——即使深思熟虑、经验丰富如詹姆斯·默雷,都想当然以为以A开头的词数有代表性,那么只要编完所有A开头的词,就可以推算还要多久能完成整部词典。

可很快他就得认清A开头的词不典型(很明显其中包括很多源于希腊语或拉丁语的派生词,这些词的意思不多),而且典型首字母这整个想法就不切实际。

另外,词典编纂者估计寻找罕见词或科学术语要耗费时间精力,结果却发现最难的词反而是看来最简单的词。

《牛津英语大词典》最长的词条是简单却难以捉摸的小词set,默雷也曾因编写“那可怕的词Black(黑)和它的派生词”而陷入深深绝望。

词典编纂者还得争分夺秒。

不这样不行,因为不抓紧,落下的就越来越多,而新出现的语言现象得经过一定时间才能收录进词典之中。

另外,像《牛津英语大词典》这样浩瀚的工程得分部出版,才能保持所有参与人员的士气。

但如果读者觉得有生之年无望看到词典编完出版,他们就不会买了。

订购的人是这样,出版商也一样。

他们当然希望自己的投资能有点回报,至少是金钱上的回报。

所以在这场和时间的赛跑中就得有进度表,也就有了焦虑、不满和催促,因为时间从来不等人。

“三重梦魇:空间、时间、金钱”——这是詹姆斯·默雷的孙女伊丽莎白·默雷为她祖父写的传记中主要章节的标题。

这本传记动人、诚挚、谦恭,记录许多轶事,生动地再现了默雷的生平。

他相信是天意给了他这个重大的机遇。

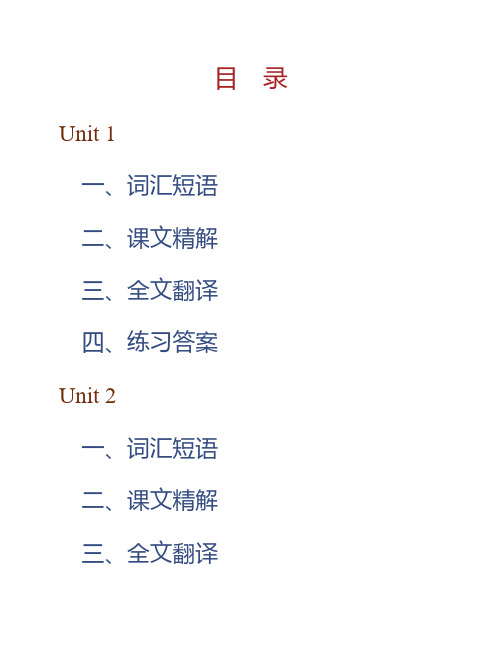

目 录Unit 1一、词汇短语二、课文精解三、全文翻译四、练习答案Unit 2一、词汇短语二、课文精解三、全文翻译四、练习答案Unit 3一、词汇短语二、练习答案Unit 4一、词汇短语二、课文精解三、全文翻译四、练习答案Unit 5一、词汇短语二、课文精解三、全文翻译四、练习答案Unit 6一、词汇短语二、练习答案Unit 7一、词汇短语二、课文精解三、全文翻译四、练习答案Unit 8一、词汇短语二、课文精解三、全文翻译四、练习答案Unit 9一、词汇短语二、练习答案Unit 10一、词汇短语二、课文精解三、全文翻译四、练习答案Unit 11一、词汇短语二、课文精解三、全文翻译四、练习答案Unit 12一、词汇短语二、练习答案Unit 1一、词汇短语Intensive Readingdivide [di5vaid] vt. 划分;除;分开;使产生分歧vi. 分开;意见分歧n. 分水岭,分水线【例句】The Nile divides near its mouth and forms a delta. 尼罗河在靠近河口的地方分开,形成一个三角洲。

【词组】divide into 除,除尽,把…作除数;把…分成…divide up瓜分;分割;分配divide out分配;除,约去various [5vZEriEs] adj. 各种各样的,不同的,多方面的,多样的【例句】There are various colors to choose from. 有各种各样的颜色可供选择。

gesture [5dVestFE] n. 姿态,手势;表示v. 做手势,以手势表示【例句】①He put his arm round her in a protective gesture. 他用一只手臂围住她做出保护的姿势。

②He gestured (to me) that it was time to go. 他向我示意该走了。

信用卡陷阱有一件事我得坦白。

几年前,我排队为家人取戏票时,我的朋友也在为她的家人取票。

我拿到了票,用信用卡付了账,对这种非现金交易的便利感到很满意。

然后就轮到她付款了,整个交易也进行得同样顺利,但我的高兴劲儿很快就变成了莫大的羞耻:我的信用卡太寒酸了,是不显示身份地位的深蓝色卡,而她的信用卡则是高级的金卡。

她是怎样弄到金卡的?怎么会这样呢?我知道我挣得比她多,我的车比她的车新,我的家比她的家漂亮,她怎么看起来显得比我光鲜呢?我有一份跟那时候任何工作相比还算安定的工作——虽然不是非常安定,不过我也没什么可抱怨的。

我是通过按揭贷款买的房子,可那会儿谁买房不贷款呢?我每个月底都付清信用卡欠款。

所以,虽然从技术上讲,我欠过信用卡公司的钱,但只是欠几个星期而已。

所以我认为我的信用等级应该很高。

你可以说我肤浅,而我也并不感到自豪。

但就在当时当地,我突然非常嫉妒那位朋友,我决定不要蓝色信用卡了,我要一张金卡。

金卡突然变得不可或缺,它会让我自我感觉良好,会让别人觉得我更有魅力。

于是,我去信用卡公司申请最特别、最耀眼的金卡。

可是,我的申请被拒绝了。

过了几秒钟,我才从这个打击中回过神来,我问自己为什么被拒绝。

显然,因为我每次都按时全额付清信用卡欠款,所以我不是他们想要的那种金卡客户。

他们的目标客户是那些随时有购物刷卡的冲动、有潜在信用风险、经不住诱惑超支消费、并且经常延期还款的人。

这样他们才有机会收取更多的利息,挣更多的钱,这就是他们的经营之道。

这能够解释为什么信用卡公司会用超低利率诱惑像我们家孩子那样的穷大学生吗?三个星期前,我的二女儿回家过周末。

她在读大一第二学期。

和她的大多数朋友一样,她借了3,000英镑的学生贷款,并从她可怜的妈妈(哈!)那里得到一笔小小的生活费,用于支付交通费、书费及其他生活费用。

她穿的衣服是从当地的慈善商店买来的,并且她平时也很少出门。

她拥抱了我(她以前从不拥抱我),然后说:“妈妈,我有事要跟您商量。

全新版大学英语阅读教程4Unit 1 In the Frozen Waters of Qomolangma,I learned the Value of Humility在结冰的珠穆朗玛峰,我学会了谦虚的价值2007年7月15日,我游过一个开放的补丁的海洋在北极突出的北极冰雪融化的海冰。

Three years later, I remember it as if it were yesterday. 三年后,我记得这件事仿佛就发生在昨天。

I recall walking to the edge of the sea and thinking: I've never seen anything so frightening in my life. 我记得走到的边缘海和思考:我从未见过任何东西这么可怕的在我的生命中。

There were giant chunks of ice in the water, which was –1.7C (29F) and utterly black.,,从看着我的手指。

They had swollen to the size of sausages. 他们已膨胀到香肠的大小。

The majority of the human body is water and when water freezes, it expands. 大多数人的身体是水和水结冰时扩大。

The cells in my fingers had frozen, swollen and burst. 这些细胞在我的手指已经冻结了膨胀和破灭。

I had never felt anything so excruciating. 我感到从未有过的任何痛苦。

My nerve cells were so badly damaged it was four months before I could feel my hands again. 我的神经细胞被严重的损害它是四个月之前,我能感觉到我的手再一次。

Unit 1Text天才与工匠许多人羡慕作家们的精彩小说,但却很少有人知道作家们是如何辛勤笔耕才使一篇小说问世的。

以下的短文将讨论小说的酝酿过程,以及作家是如何将这小说雕琢成一件精致完美的艺术品。

1.有一次,我在暮色中来到小树林边一棵鲜花盛开的小桃树前。

我久久站在那里凝视着,直到最后一道光线消逝。

我看不到那树原先的模样,看不见曾穿透果核,能崩碎你的牙齿的力量,也看不到那使它与橡树和绿草相区别的原则。

显现在我面前的,是一种深邃而神秘的魅力。

2. 当读者读到一部杰出的小说时,他也会这样如痴如狂,欲将小说字字句句刻骨铭心,不提出任何问题。

3.但即使是个初学写作者也知道,除那将小说带到世上的文字之外,还有更多的构成小说生命的因素,小说的生命并不始于写作,而始于内心深处的构思。

4. 要创作出有独创性的作品,并不要求懂得创造的功能。

多少世纪以来的艺术、哲学及科学创造都出自人们的头脑,而创造者也许从未想到去关注创造的内在过程。

然而,在我看来,对创造工作一定程度的了解,至少会使我们通过知道两个事实,增长我们处理正在出现的故事的智慧。

5. 首先,天赋不是掌握了技艺的艺术家独有的特性,而是人脑的创造性功能。

不仅所有对技艺的掌握都含有天赋,而且每个人都具有天赋,无论他的天赋发展是何等不充分。

对技艺的掌握是天赋的显现,是经过培养的,发展了的和受过训练的天赋。

你的天赋在最原始的层面上起作用。

它的任务就是创造。

它是你的故事的创造者。

6. 第二,将你的小说带进世界的文字是艺术家的工作,它就和一个泥瓦匠的工作一样,有意识、谨慎而实实在在。

天赋正如理解力、记忆力和想象力一样是我们的精神禀赋中的天然部分,而技艺却不是。

它必须通过实践才能学到,并要通过实践才能掌握。

如果要使在我们内心深处浮现的故事跃然纸上,光彩照人,那么,每个故事都须有感染力极强的优雅文笔。

Unit 1 Active reading (1) / P3Looking for a job after university? First, get off the sofaMore than 650000 students left university this summer and many have no idea about the way to get a job. How tough should a parent be to galvanize them in these financially fraught times?今年夏天,超过65万名学生离开了大学,很多人都不知道如何找到工作。

在这个经济困难的时期,父母应该怎样严厉地激励他们呢?In July, you looked on as your handsome 21-year-old son, dressed in gown and mortarboard, proudly clutched his honors degree for his graduation photo. Those memories of forking out thousands of pounds a year so that he could eat well and go to the odd party, began to fade. Until now.7月,你看着你21岁的儿子,穿着学士服,戴着学位帽,骄傲地拿着他的荣誉学位拍毕业照。

那些为了吃得好、参加不定期的聚会而每年掏出几千英镑的记忆开始消失了。

直到现在。

As the summer break comes to a close and students across the country prepare for the start of a new term, you find that your graduate son is still spending his days slumped in front of the television, broken only by texting, Facebook and visits to the pub. This former scion of Generation Y has morphed overnight into a member of Generation Grunt. Will he ever get a job?当暑假即将结束,全国各地的学生都在为新学期的开始做准备时,你会发现,你毕业的儿子仍然整天窝在电视机前,只有发短信、上Facebook和泡酒吧。

Looking good by doing good[Jan 15th 2009]Economics focusLooking good by doing goodJan 15th 2009From The Economist print editionRewarding people for their generosity may be counterproductiveIllustration by Jac Depczyk A LARGE plaque in the foyer of Boston’s Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA), a museum housed in a dramatic glass and metal building on the harbour’s edge, identifies its most generous patron s. Visitors who stop to look will notice that some donors—including two who gave the ICA over $2.5m—have chosen not to reveal their names. Such reticence is unusual: less than 1% of private gifts to charity are anonymous. Most people (including the vast majority of the ICA’s patrons) want their good deeds to be talked about. In “Richistan”, a book on America’s new rich, Robert Frank writes of the several society publications in Florida’s Palm Beach which exist largely to publicise the charity of its well-heeled residents (at least before Bernard Madoff’s alleged Ponzi scheme left some of them with little left to give).As it turns out, the distinction between private and public generosity is helpful in understanding what motivates people to give money to charities or donate blood, acts which are costly to the doer and primarily benefit others. Such actions are widespread, and growing. The $306 billion that Americans gave to charity in 2007 was more than triple the amount donated in 1965. And though a big chunk of this comes from plutocrat s like Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, whose philanthropy has attracted much attention, modest earners also give generously of their time and money. A 2001 survey found that 89% of American households gave to charity, and that 44% of adults volunteered the equivalent of 9m full-time jobs. Tax break s explain some of the kindness of strangers. But by no means all.Economists, who tend to think self-interest governs most actions of man, are intrigue d, and have identified several reasons to explain good deeds of this kind. Tax breaks are, ofcourse, one of the main ones, but donors are also sometimes paid directly for their pains, and the mere thought of a thank-you letter can be enough to persuade others to cough up. Some even act out of sheer altruism. But most interesting is another explanation, which is that people do good in part because it makes them look good to those whose opinions they care about. Economists call this “image motivation”.Dan Ariely of Duke University, Anat Bracha of Tel Aviv University, and Stephan Meier of Columbia University sought, through experiments, to test the importance of image motivation, as well as to gain insights into how different motivating factors interact. Their results, which they report in a new paper*, suggest that image motivation matters a lot, at least in the laboratory. Even more intriguingly, they find evidence that monetary incentives can actually reduce charitable giving when people are driven in part by a desire to look good in others’ eyes.The crucial thing about charity as a means of image building is, of course, that it can work only if others know about it and think positively of the charity in question. So, the academics argue, people should give more when their actions are public.To test this, they conducted an experiment where the number of times participants clicked an awkward combination of computer keys determined how much money was donated on their behalf to the American Red Cross. Since 92% of participants thought highly of the Red Cross, giving to it could reasonably be assumed to make people look good to their peers. People were randomly assigned to either a private group, where only the participant knew the amount of the donation, or a public group, where the participant had to stand up at the end of the session and share this information with the group. Consistent with the hypothesis that image mattered, participants exerted much greater effort in the public case: the average number of clicks, at 900, was nearly double the average of 517 clicks in the private case.However, the academics wanted to go a step further. In this, they were influenced by the theoretical model of two economists, Roland Benabou, of Princeton University, and Jean Tirole, of Toulouse University’s Institut d’Economie Industrielle, who formalised the idea that if people do good to look good, introducing monetary or other rewards into the mix might complicate matters. An observer who sees someone getting paid for donating blood, for example, would find it hard to differentiate between the donor’s intrinsic “goodness” and his greed.Blood moneyThe idea that monetary incentives could be counterproductive has been around at least since 1970, when Richard Titmuss, a British social scientist, hypothesised that paying people to donate blood would reduce the amount of blood that they gave. But Mr Ariely and his colleagues demonstrate a mechanism through which such confound ing effects could operate. They presumed that the addition of a monetary incentive should have much less of an impact in public (where it muddle s the image signal of an action) than in private (where the image is not important). By adding a monetary reward for participants to theirexperiment, the academics were able to confirm their hypothesis. In private, being paid to click increased effort from 548 clicks to 740, but in public, there was next to no effect. The trio also raise the possibility that cleverly designed rewards could actually draw out more generosity by exploiting image motivation. Suppose, for example, that rewards were used to encourage people to support a certain cause with a minimum donation. If that cause then publicised those who were generous well beyond the minimum required of them, it would show that they were not just “in it for the money”. Behavioural economics may yet provide charities with some creative new fund-raising techniques.寻找好行善[ 2009年1月15日]经济焦点寻找好行善2009年1月15日来自经济学人印刷版回报人民的慷慨可能会适得其反插图由江淮Depczyk在波士顿当代艺术学院(ICA ),装在一个巨大的玻璃和金属建筑海港的边缘博物馆大厅一个大匾,确定其最慷慨的赞助人。

新视野大学英语(第二版)第四册读写教程课文翻译.An artist who seeks fame is like a dog chasing his own tail who, when he captures it, does not know what else to do but to continue chasing it.艺术家追求成名,如同狗自逐其尾,一旦追到手,除了继续追逐不知还能做些什么。

The cruelty of success is that it often leads those who seek such success to participate in their own destruction.成功之残酷正在于它常常让那些追逐成功者自寻毁灭。

"Don't quit your day job!" is advice frequently given by understandably pessimistic family members and friends to a budding artist who is trying hard to succeed.对一名正努力追求成功并刚刚崭露头角的艺术家,其亲朋常常会建议“正经的饭碗不能丢!”他们的担心不无道理。

The conquest of fame is difficult at best, and many end up emotionally if not financially bankrupt.追求出人头地,最乐观地说也困难重重,许多人到最后即使不是穷困潦倒,也是几近精神崩溃。

Still, impure motives such as the desire for worshipping fans and praise from peers may spur the artist on.尽管如此,希望赢得追星族追捧和同行赞扬之类的不太纯洁的动机却在激励着他们向前。

Unit 1Alone in the Arctic Cold 一个人在北极严寒一天打碎了非常寒冷和灰色,当那个人偏离主要育空试验和爬上斜坡,在那里的是一个朦胧而过去向东穿过了踪迹松林之间。

坡率陡峭,而且他停顿了一下喘不过气来保持最佳的状态。

没有太阳和缕阳光,尽管他天空无云。

这是一个晴朗的日子,但在那里似乎是一个蒙上了一层水汽表面看来,把这天黑暗。

这个事实不担心那个人。

他被用来缺乏阳光。

那人回头而且他已经来了。

育空河打下英里宽藏起来了以下3英尺的冰。

这个世界上的冰一样多英尺的积雪。

这是连续的白色的,除了一个黑暗的发际线了痕迹,向南延伸达500英里去的库特关口。

但是,整个神秘,深远的发际线跟踪,没有太阳从天空,巨大的冷的,陌生和怪异的没有什么印象all-made上了的人。

他是新来的人在这地,这是他的第一个冬天。

他的问题他是缺乏想象力。

他很快和警惕在生活的一切,但只有在去吧,而不是在意义。

意思eighty-odd零下五十度学位霜。

这样的事实了冷漠,而且不舒服,就这些。

它并不带他去思考男人的一般是脆弱,能够只活在确定的限度窄的热量和冷。

零下五度代表点冰霜伤害必须提防,利用厚,暖和的衣服。

50度以下零是他就精确50度零度以下。

应该有其他东西了可那是一个思想,从来没有进过他的头上。

当他转身要走,他吐不确定。

就有一个陡坡、易爆裂纹他的震惊。

他吐了。

又一次,空气里之前,这可能下降至雪吐口唾沫裂了。

他知道五十岁的唾沫在雪地上闪现下面,但这吐口唾沫空气中闪现了。

毫无疑问这个五十个更加寒冷below-how要冷得多了不知道。

但是温度还显得无关紧要。

他注定的老我的左边叉子汉德森的孩子们在小溪了。

他们来了在山上从印度人小河的国家,虽然他来拐弯抹角看一看的可能性走出木材来源于群岛的育空。

他要在六营地点,有点天黑之后,这是真的,但男孩们会去,火灾的去,和热晚饭将为此做好准备。

他陷入水中在大松树。

踪迹减弱了。

他很高兴他没有雪橇、旅游的光。

Nine Years for A and B

九年遂成AB部(1)

克利斯朵夫·里克斯[1]著敏译

塞缪尔·约翰逊博士[2]是最伟大的词典编纂人。

詹姆斯·默雷则是编写了最伟大词典的人:从1879年直到1915年去世,他把大半生都献给了《牛津英语大词典》的编纂工作。

约翰逊博士比谁都更有资格说词典编纂者是个“无害的苦工”[3]。

他知道词典编纂包含的远远不只是苦工,而且其单调乏味程度简直难以想象,即使词典编纂者也有幸无法事先清楚预估。

所以词典编纂者——即使深思熟虑、经验丰富如詹姆斯·默雷,都想当然以为以A开头的词数有代表性,那么只要编完所有A开头的词,就可以推算还要多久能完成整部词典。

可很快他就得认清A开头的词不典型(很明显其中包括很多源于希腊语或拉丁语的派生词,这些词的意思不多),而且典型首字母这整个想法就不切实际。

另外,词典编纂者估计寻找罕见词或科学术语要耗费时间精力,结果却发现最难的词反而是看来最简单的词。

《牛津英语大词典》最长的词条是简单却难以捉摸的小词set,默雷也曾因编写“那可怕的词Black(黑)和它的派生词”而陷入深深绝望。

词典编纂者还得争分夺秒。

不这样不行,因为不抓紧,落下的就越来越多,而新出现的语言现象得经过一定时间才能收录进词典之中。

另外,像《牛津英语大词典》这样浩瀚的工程得分部出版,才能保持所有参与人员的士气。

但如果读者觉得有生之年无望看到词典编完出版,他们就不会买了。

订购的人是这样,出版商也一样。

他们当然希望自己的投资能有点回报,至少是金钱上的回报。

所以在这场和时间的赛跑中就得有进度表,也就有了焦虑、不满和催促,因为时间从来不等人。

“三重梦魇:空间、时间、金钱”——这是詹姆斯·默雷的孙女伊丽莎白·默雷为她祖父写的传记中主要章节的标题。

这本传记动人、诚挚、谦恭,记录许多轶事,生动地再现了默雷的生平。

他相信是天意给了他这个重大的机遇。

他的宗教信仰、爱国精神、他的意志力和异常广博的学术天赋、他的协调能力,都集中体现在他受托进行的这项任务之上。

[1]克利斯朵夫·里克斯(Christopher Ricks),英国文学评论家。

本文是一篇书评,评论伊丽莎白·默雷为其祖父詹姆斯·默雷写的传记。

[2]塞缪尔·约翰逊博士(Samuel Johnson, 1709-84),18世纪英国最重要的作家之一,编纂的《英语词典》在1755年出版后一直是最权威的英语词典,直到20世纪初才被《牛津英语词典》取而代之。

[3]“无害的苦工”(harmless drudge)出自塞缪尔·约翰逊在《英语词典》中对“词典编纂者”这一词条的定义,原文是Lexicographer: a writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge that busies himself in tracing the original and detailing the signification of words (词典编纂者是编字典的人,忙于溯源、详述词语含义的无害的苦工)。

九年遂成A与B(2)

克利斯朵夫·里克斯著敏译

他会不会承认也是上天慈悲,没让他知道他永远没法完成这项任务?这本“大词典”独一无二的重要性他从没低估过,但他却一再低估了词典最终的规模:1万6千多页——全是大开页,密密麻麻,排版紧凑——其中默雷亲自编写近一半内容。

如果一百年前的当时(默雷同意编写词典时正是40岁),神轻轻告诉他工程开始后9年才只出版完以A和B开头的词,而他78岁去世时离大功告成还早着呢,那他还会开始这项毕生的事业吗?

答案当然是会。

詹姆斯·默雷1837年生于苏格兰,父亲是乡下裁缝。

他读过牧区学校,但14岁时就不上了,却还执著地继续自学。

他热爱知识,也热爱传授知识,后来成为教师,学了一门又一门语言,还很关注地质学、考古学、语音学和地方政治。

第一任妻子生病,他不得不离开苏格兰来到伦敦,当起银行职员。

没受过一点大学教育的他凭借纯粹的学术热忱自学成材,成为当时卓越的语文学家眼中举足轻重的人物。

后来他重回讲台,余下人生的每一天都在轮轴转中度过,因为他应邀着手编写《牛津英语辞典》,这个邀请他无法拒绝。

起初他兼顾教书

和辞典编写。

后来他搬到牛津,全心全意建造这座无与伦比的丰碑,之所以无与伦比,是因为它纪念的不是他自己,也不是什么死亡的东西,而是不朽的东西——英语。

这本词典不同寻常之处在于它严谨的词源追溯,对每个词本义和引申义精妙有力的定义和细分,而它用于举例说明的引语的范围、精确度和组织不只是不同寻常,还是独一无二的。

一大群受过专门培训的志愿者采集引语,由副编筛选,最后默雷在他的“缮写室”里做出调整,并尽其它各种努力使这本字典在人力所及的范围内尽善尽美。

他兢兢业业、一丝不苟,有时不得不像追野鹅一样忙于厘清疑惑。

他问罗伯特·路易斯·史蒂文森他一本书里的单词“brean”是什么意思,结果发现是把“ocean”印错了。

他对詹姆斯·拉塞尔·洛威尔一篇文章中的复数名词“alliterates”疑惑不解,却发现那也是印刷错误,这次是把“illiterates”印错了。

默雷为自己的事业骄傲,但他不自傲,他不想留传记:“我无足轻重——如果你对《词典》有什么想说的,尽可以说——但把我当成一则太阳神话,一个回声,一个无理数,或是干脆忽略我。

”但他不容忽视,他是一个卓越的维多利亚时期学者,如我们现在所知,绝对不容小觑。

他的一生平凡而有尊严,写成传记要说震撼人心有些过头,要说毫无触动也未免麻木不仁。

无止境的压力诱他应付了事,他因此想过请辞,他说:“这项事业重于我,重于任何从事它的人。

”只有一个伟大的人会这么说,并且以那么纯粹的真诚和自我牺牲精神接着说:“虽然我永远不愿放弃这项事业,可如果别人能更好更快地完成,我也决不会占着不放。

”

默雷的一生充满苦痛艰辛,却并不残酷,一个人这一生能完全了解自己、了解自己能做的事并甘之如饴,他的人生又怎么会残酷。

默雷和他的朋友同事一样,从“现在”中体会到一种深刻的一脉相承,不只同“过去”紧密相连,(从中继承了表达思维、感觉和行为的语言),还同未来紧密相连,由未来继续传承。

他们的孩子,孩子的孩子才是他们为之奋斗的对象,他们一直是这么认为的。

此刻正是默雷的孩子的孩子记录了他的一生。

这位伟人在招募志愿者时说过:“如果你不为这项事业感到光荣,没有兴趣协助我,那我也用不着你,别为我悲哀,为你和你的孩子悲哀吧。

”。