污水处理工业废水回用中英文对照外文翻译文献

- 格式:doc

- 大小:51.50 KB

- 文档页数:13

污水处理工业废水回用中英文对照外文翻译文献XXX and resource recovery in us industries。

and they are of significant XXX-catalysis has been well established for water recovery and reuse。

chemo-catalysis is only starting to make an XXX-catalytic processes for water reuse。

XXX。

XXX.2.Chemo-XXX reuseChemo-XXX。

including XXX。

One of the most promising ns of chemo-XXX。

XXX。

This process has been shown to be effective in removing COD (chemical oxygen demand) XXX.3.XXX COD removalXXX treatment。

The process involves the use of a XXX can be a metal oxide or a metal complex。

and the oxidizing agent can be hydrogen peroxide。

ozone。

or XXX mild ns。

and the process is XXX.4.XXXXXX (AOPs) such as XXX。

photo-Fenton n。

and electro-XXX include the use of anic frameworks (MOFs) XXX.5.nIn n。

chemo-catalytic processes。

XXX。

XXX。

such as AOPs。

MOFs。

and nanomaterials。

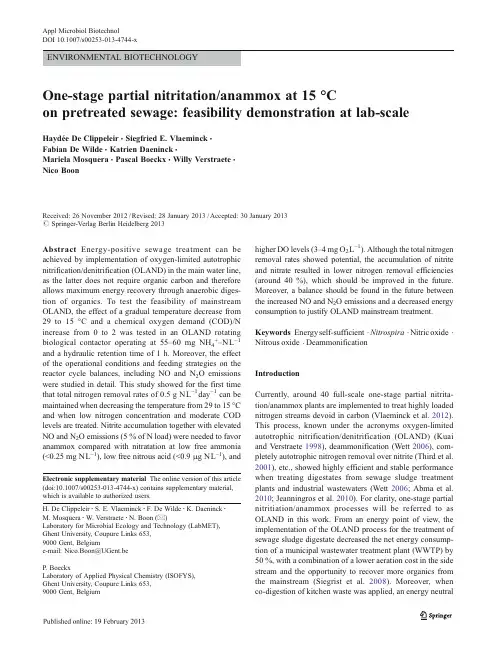

ENVIRONMENTAL BIOTECHNOLOGYOne-stage partial nitritation/anammox at15°Con pretreated sewage:feasibility demonstration at lab-scale Haydée De Clippeleir&Siegfried E.Vlaeminck&Fabian De Wilde&Katrien Daeninck&Mariela Mosquera&Pascal Boeckx&Willy Verstraete&Nico BoonReceived:26November2012/Revised:28January2013/Accepted:30January2013#Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg2013Abstract Energy-positive sewage treatment can beachieved by implementation of oxygen-limited autotrophicnitrification/denitrification(OLAND)in the main water line,as the latter does not require organic carbon and thereforeallows maximum energy recovery through anaerobic diges-tion of organics.To test the feasibility of mainstreamOLAND,the effect of a gradual temperature decrease from29to15°C and a chemical oxygen demand(COD)/Nincrease from0to2was tested in an OLAND rotatingbiological contactor operating at55–60mg NH4+–NL−1 and a hydraulic retention time of1h.Moreover,the effectof the operational conditions and feeding strategies on thereactor cycle balances,including NO and N2O emissionswere studied in detail.This study showed for the first timethat total nitrogen removal rates of0.5g NL−1day−1can bemaintained when decreasing the temperature from29to15°Cand when low nitrogen concentration and moderate CODlevels are treated.Nitrite accumulation together with elevatedNO and N2O emissions(5%of N load)were needed to favoranammox compared with nitratation at low free ammonia(<0.25mg NL−1),low free nitrous acid(<0.9μg NL−1),and higher DO levels(3–4mg O2L−1).Although the total nitrogen removal rates showed potential,the accumulation of nitrite and nitrate resulted in lower nitrogen removal efficiencies (around40%),which should be improved in the future. Moreover,a balance should be found in the future between the increased NO and N2O emissions and a decreased energy consumption to justify OLAND mainstream treatment. Keywords Energyself-sufficient.Nitrospira.Nitricoxide. Nitrous oxide.DeammonificationIntroductionCurrently,around40full-scale one-stage partial nitrita-tion/anammox plants are implemented to treat highly loaded nitrogen streams devoid in carbon(Vlaeminck et al.2012). This process,known under the acronyms oxygen-limited autotrophic nitrification/denitrification(OLAND)(Kuai and Verstraete1998),deammonification(Wett2006),com-pletely autotrophic nitrogen removal over nitrite(Third et al. 2001),etc.,showed highly efficient and stable performance when treating digestates from sewage sludge treatment plants and industrial wastewaters(Wett2006;Abma et al. 2010;Jeanningros et al.2010).For clarity,one-stage partial nitritiation/anammox processes will be referred to as OLAND in this work.From an energy point of view,the implementation of the OLAND process for the treatment of sewage sludge digestate decreased the net energy consump-tion of a municipal wastewater treatment plant(WWTP)by 50%,with a combination of a lower aeration cost in the side stream and the opportunity to recover more organics from the mainstream(Siegrist et al.2008).Moreover,when co-digestion of kitchen waste was applied,an energyneutral Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article(doi:10.1007/s00253-013-4744-x)contains supplementary material,which is available to authorized users.H.De Clippeleir:S.E.Vlaeminck:F.De Wilde:K.Daeninck:M.Mosquera:W.Verstraete:N.Boon(*)Laboratory for Microbial Ecology and Technology(LabMET),Ghent University,Coupure Links653,9000Gent,Belgiume-mail:Nico.Boon@UGent.beP.BoeckxLaboratory of Applied Physical Chemistry(ISOFYS),Ghent University,Coupure Links653,9000Gent,BelgiumAppl Microbiol BiotechnolDOI10.1007/s00253-013-4744-xWWTP was achieved(Wett et al.2007).To fully recover the potential energy present in wastewater,a first idea of a new sustainable wastewater treatment concept was reported (Jetten et al.1997).Recently,a“ZeroWasteWater”concept was proposed which replaces the conventional activated sludge system by a highly loaded activated sludge step (A-step),bringing as much as organic carbon(chemical oxygen demand(COD))as possible to the solid fraction, and a second biological step(B-step)removing the residual nitrogen and COD with a minimal energy demand (Verstraete and Vlaeminck2011).Subsequently,energy is recovered via anaerobic digestion of the primary and sec-ondary sludge.For the B-step in the main line,OLAND would potentially be the best choice as this process can work at a low COD/N ratio,allowing maximum recovery of COD in the A-step.Moreover,it was calculated that if OLAND is implemented in the main water treatment line and a maximum COD recovery takes place in the A-step,a net energy gain of the WWTP of10Wh inhabitant equivalent (IE)−1day−1is feasible(De Clippeleir et al.2013).To allow this energy-positive sewage treatment,OLAND has to face some challenges compared with the treatment of highly loaded nitrogen streams(>250mg NL−1).A first difference is the lower nitrogen concentration to be removed by OLAND.Domestic wastewater after advanced concen-tration will still contain around30–100mg NL−1and113–300mg CODL−1(Metcalf and Eddy2003;Tchobanoglous et al.2003;Henze et al.2008).High nitrogen conversion rates(around400mg NL−1day−1)by the OLAND process can be obtained at nitrogen concentrations of30–60mg N L−1and at low hydraulic retention times(HRT)of1–2h(De Clippeleir et al.2011).A second challenge is the low tem-perature at which OLAND should be operated(10–15°C compared with34°C).Several studies already described the effect of temperature on the activity of the separate micro-bial groups(Dosta et al.2008;Guo et al.2010;Hendrickx et al.2012).Only a few studies showed the long-term effect of a temperature decrease below20°C on the microbial bal-ances of anoxic and aerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria (AnAOB and AerAOB)and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB)at nitrogen concentrations above100mg NL−1 (Vazquez-Padin et al.2011;Winkler et al.2011).However, the combination of low temperature and low nitrogen con-centration was never tested on a co-culture of AerAOB, AnAOB,and NOB before.At temperatures around15°C, maintaining the balance between NOB and AnAOB and the balance between NOB and AerAOB will get more challeng-ing since the growth rate of NOB will become higher than the growth rate of AerAOB(Hellinga et al.1998). Therefore,it will not be possible to wash out NOB based on overall or even selective sludge retention.The third and main challenge in this application will therefore be the suppression of NOB at temperature ranges of10–20°C and at nitrogen concentration ranges of30–60mg NL−1 (low free ammonia and low nitrous acid),which was not shown before.A final fourth challenge will include the higher input of organics at moderate levels of90–240mg biodegradable CODL−1in the wastewater.Depending on the raw sewage strength,COD/N ratios between2and3are expected after the concentration step,which is on the edge of the described limit for successful OLAND(Lackner et al. 2008).The presence of organics could result in an extra competition of heterotrophic denitrifiers with AerAOB for oxygen or with AnAOB for nitrite or organics,since certain AnAOB can denitrify consuming organic acids (Kartal et al.2007).In this study,the challenges2to4,were evaluated in an OLAND rotating biological contactor(RBC).This reactor at 29°C was gradually adapted over24,22,and17to15°C under synthetic wastewater conditions(60mg N L−1, COD/N of0).Additionally,the COD/N ratio of the influent was increased to2by supplementing NH4+to diluted sewage to simulate pretreated sewage.The effect of the operational conditions and feeding strategies on the reactor cycle balan-ces,including gas emissions and microbial activities were studied in detail.An alternative strategy to inhibit NOB activity and as a consequence increase AnAOB activity at low temperatures based on NO production was proposed. Materials and methodsOLAND RBCThe lab-scale RBC described by De Clippeleir et al.(2011) was further optimized at29°C by an increase in the influent nitrogen concentration from30to60mg NL−1and a limitation of the oxygen input through the atmosphere by covering the reactor before this test was started.The reactor was based on an air washer LW14(Venta,Weingarten, Germany)with a rotor consisting of40discs interspaced at 3mm,resulting in a disc contact surface of1.32m2.The reactor had a liquid volume of2.5L,immersing the discs for 55%.The latter was varied over the time of the experiment. The reactor was placed in a temperature-controlled room. The DO concentration was not directly controlled.In this work,continuous rotation was applied at a constant rotation speed of3rpm,which allowed mixing of the water phase. RBC operationThe RBC was fed with synthetic wastewater during phases I to VII.From phase VIII onwards,the COD/N was gradually increased(phases VIII–X)to2(phases XI–XIII).The syn-thetic influent of an OLAND RBC,consisted of(NH4)2SO4 (55–60mg NL−1),NaHCO3(16mg NaHCO3mg−1N),andAppl Microbiol BiotechnolKH2PO4(10mg PL−1).Pretreated sewage was simulated by diluting raw sewage of the communal WWTP of Gent, Belgium(Aquafin).The raw wastewater after storage at 4°C and settlement contained23–46mg NH4+–NL−1, 0.2–0.4mg NO2−–NL−1,0.4–2.7mg NO3−–NL−1,23–46mgKjeldahl–NL−1,3.8–3.9mg PO43−–PL-1,26–27mg SO42−–S L−1,141–303mg COD tot L−1,and74–145mg COD sol L−1.The raw sewage was diluted by factors2–3to obtain COD values around110mg COD tot L−1and by addition of(NH4)2SO4to obtain final COD/N values around2.The reactor was fed in a semi-continuous mode:two periods of around10min/h for phases I–XI and one period of20min/h for phases XII and XIII.The influent flow range varied from47to65Lday−1and the reactor volume from3.7to2.5L(during78and55% submersion,respectively).Corresponding HRTare displayed in Tables1and2.Reactor pH,DO,and temperature were daily monitored and influent and effluent samples were taken at least thrice a week for ammonium,nitrite,nitrate,and COD analyses. Detection of AerAOB,NOB,and AnAOB with FISHand qPCRFor NOB and AnAOB,a first genus screening among the most commonly present organisms was performed by fluo-rescent in-situ hybridization(FISH)on biomass of days1 (high temperature)and435(low temperature and COD presence).A paraformaldehyde(4%)solution was used for biofilm fixation,and FISH was performed according to Amann et al.(1990).The Sca1309and Amx820probes were used for the detection of Cand.Scalindua and Cand. Kuenenia&Brocadia,respectively,and the NIT3and Ntspa662probes and their competitors for Nitrobacter and Nitrospira,respectively(Loy et al.2003).This showed the absence of Nitrobacter and Scalindua(Table S1in the Electronic supplementary material(ESM)).Biomass sam-ples(approximately5g)for nucleic acid analysis were taken from the OLAND RBC at days1,60,174,202,306,385, 399,and413of the operation.DNA was extracted using FastDNA®SPIN Kit for Soil(MP Biomedicals,LLC), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.The obtained DNA was purified with the Wizard®DNA Clean-up System (Promega,USA)and its final concentration was measured spectrophotometrically using a NanoDrop ND-1000spec-trophotometer(Nanodrop Technologies).The SYBR Green assay(Power SyBr Green,Applied Biosystems)was used to quantify the16S rRNA of AnAOB and Nitrospira sp.and the functional amoA gene for AerAOB.The primers for quantitative polymerase chain reactions(qPCR)for detection of AerAOB,NOB,and AnAOB were amoA-1F–amoA-2R (Rotthauwe et al.1997),NSR1113f–NSR1264r(Dionisi et al. 2002),and Amx818f–Amx1066r(Tsushima et al.2007),re-spectively.For bacterial amoA gene,PCR conditions were: 40cycles of94°C for1min,55°C for1min,and60°C for 2min.For the amplification of Nitrospira sp.16S rRNA gene, 40cycles of95°C for1min,50°C for1min,and60°C for 1min were used while for AnAOB16S rRNA the PCR temperature program was performed by40cycles of15s at 94°C and1min at60°C.Plasmid DNAs carrying NitrospiraTable1Effect of temperature decrease on the operational conditions and performance of OLAND RBC reactorPhase I II III IV V VI VIIPeriod(days)1–2122–3536–6162–210210–263263–274275–306 Immersion level(%)78787878557855 Temperature(°C)29±224±122±0.617±1.216±0.915±0.814±0.4 Operational conditionsDO(mg O2L−1) 1.1±0.2 1.3±0.2 1.4±0.1 1.7±0.3 2.8±0.4 2.4±0.2 3.1±0.2 pH(−)7.5±0.17.5±0.17.5±0.17.6±0.17.7±0.17.7±0.17.8±0.1 HRT(h) 1.85±0.04 1.84±0.09 1.73±0.04 1.86±0.11 1.09±0.02 1.57±0.02 1.09±0.02 FA(mg NL−1)0.35±0.180.36±0.180.34±0.140.36±0.130.25±0.160.33±0.170.13±0.04 FNA(μg NL−1)0.3±0.10.3±0.20.4±0.20.4±0.10.9±0.40.6±0.10.9±0.2 PerformanceTotal N removal efficiency(%)54±552±549±934±936±936±942±4 Relative NO3−prod(%of NH4+cons a)7±17±17±114±618±916±321±4 Relative NO2−accum(%of NH4+cons)2±43±45±515±530±826±631±5 AerAOB activity(mg NH4+–NL−1day−1)267±38267±49260±52260±53811±229460±44986±71 NOB activity(mg NO2–NL−1day−1)0±00±00±09±1260±9420±585±25 AnAOB activity(mg N tot L−1day−1)412±38403±37368±76248±67448±117305±74529±75DO dissolved oxygen,HRT hydraulic retention time,F A free ammonia,FNA free nitrous acid,cons consumption,prod production,accum accumulation,tot totala NH4+consumption is corrected for nitrite accumulationAppl Microbiol Biotechnoland AnAOB16S rRNA gene and AerAOB functional AmoA gene,respectively,were used as standards for qPCR.All the amplification reactions had a high correlation coefficient (R2>0.98)and slopes between−3.0and−3.3.Detailed reactor cycle balancesFor the measurements of the total nitrogen balance,including the NO and N2O emissions,the OLAND RBC was placed in a vessel(34L)which had a small opening at the top(5cm2).In this vessel,a constant upward air flow(around1ms−1or0.5L s-1)was generated to allow calculations of emission rates.On the top of the vessel(air outlet),the NO and N2O concentra-tion was measured,off-and online,respectively.NH3emis-sions were negligible in a RBC operated at about2mg NH3–NL−1(Pynaert et al.2003).Since FA levels in the currentstudy are about ten times lower,NH3emissions were not included.In the water phase,ammonium,nitrite,nitrate,hy-droxylamine(NH2OH),N2O,and COD concentrations were measured.Moreover,DO concentration and pH values were monitored.The air flow was measured with Testo425hand probe(Testo,Ternat,Belgium).Chemical analysesAmmonium(Nessler method)was determined according to standard methods(Greenberg et al.1992).Nitrite and nitrate were determined on a761compact ion chromatograph equipped with a conductivity detector(Metrohm,Zofingen, Switzerland).Hydroxylamine was measured spectrophoto-metrically(Frear and Burrell1955).The COD was determined with NANOCOLOR®COD1500en NANOCOLOR®COD 160kits(Macherey-Nagel,Düren,Germany).The volumetric nitrogen conversion rates by AerAOB,NOB,and AnAOB were calculated based on the measured influent and effluent compositions and the described stoichiometries,underestimat-ing the activity of AnAOB by assuming that all COD removed was anoxically converted with nitrate to nitrogen gas (Vlaeminck et al.2012).DO and pH were measured with respectively,a HQ30d DO meter(Hach Lange,Düsseldorf, Germany)and an electrode installed on a C833meter (Consort,Turnhout,Belgium).Gaseous N2O concentrations were measured online at a time interval of3min with a photo-acoustic infrared multi-gas monitor(Brüel&Kjær, Model1302,Nærem,Denmark).Gas grab samples were taken during the detailed cycle balance tests for NO detec-tion using Eco Physics CLD77AM(Eco Physics AG, Duernten,Switzerland),which is based on the principle of chemiluminescence.For dissolved N2O measurements,a1-mL filtered(0.45μm)sample was brought into a7-mL vacutainer(−900hPa)and measured afterwards by pressure adjustment with He and immediate injection at21°C in a gas chromatograph equipped with an electron capture detector (Shimadzu GC-14B,Japan).Table2Effect of COD/N increase on the operational conditions and performance of OLAND RBC reactorPhase VIII IX X XI XII XIIIPeriod(days)355–361362–369370–374375–406407–421422–435 Immersion level(%)555555555555COD/N(-)0.51 1.5222 Feeding regime(pulsesh−1)222211 Operational conditionsDO(mg O2L−1) 2.9±0.3 2.5±0.6 2.4±0.3 3.0±0.7 3.6±0.3 3.2±0.3 pH(−)7.8±0.027.7±0.17.6±0.027.6±0.17.6±0.27.6±0.1 HRT(h) 1.06±0.11 1.03±0.020.92±0.020.94±0.05 1.10±0.05 1.06±0.2 FA(mg NL−1)0.10±0.050.04±0.050.15±0.050.21±0.100.23±0.120.04±0.02 FNA(μg NL−1)0.4±0.10.2±0.20.2±0.010.3±0.10.2±0.10.6±0.2 PerformanceTotal N removal efficiency(%)36±545±1823±328±623±1342±3 Relative NO3−prod(%of NH4+cons a)42±543±1263±250±662±1846±6 Relative NO2−accum(%of NH4+cons)20±410±105±18±37±413±6 AerAOB activity(mg NH4+–NL−1day−1)592±15446±31238±28352±73289±138600±204 NOB activity(mg NO2−–NL−1day−1)257±19294±81465±60352±84427±115394±76 AnAOB activity(mg N tot L−1day−1)385±86452±205262±39355±73281±159481±73COD removal rates were negligible in all phasesDO dissolved oxygen,HRT hydraulic retention time,F A free ammonia,FNA free nitrous acid,cons consumption,prod production,accum accumulation,tot totala NH4+consumption is corrected for nitrite accumulationAppl Microbiol BiotechnolResultsEffect of temperature decreaseDuring the reference period (29°C),a well-balanced OLAND performance (Fig.1;Table 1)was reached with minimal nitrite accumulation (2%)and minimal nitrate production (7%).This was reflected in an AerAOB/AnAOB activity ratio of 0.6(Table 1,phase I).The total nitrogen removal rate was on average 470mg N L −1day −1or 1314mg Nm −2day −1,and the total nitrogen removal efficiency was 54%.Decreasing the temperature from 29to 24°C and further to 22°C over the following 40days,did not result in anysignificant changes of the operational conditions (Table 1;phases I –III),performance of the reactor (Fig.1)or abun-dance of the bacterial groups (qPCR;Fig.S1in the ESM ).However at 17°C,a decrease in total nitrogen removal efficiency was observed (Table 1;phase IV).An imbalance between the AerAOB and the AnAOB was apparent from a stable AerAOB activity yet a declining AnAOB activity.Moreover,NOB activity was for the first time detected in spite of free ammonia (FA)and free nitrous acid (FNA)con-centrations did not change (Table 1;phase IV).Moreover,no significant differences in abundance of NOB,AerAOB,and AnAOB could be detected with qPCR (Fig.S1in the ESM ).However,DO concentrations started to increase during that period from 1.4to 1.7mg O 2L −1.As the availabilityofFig.1Phases I –VII:effect of temperature decrease on the volumetric rates (top )and nitrogen concentrations (bottom )Appl Microbiol Biotechnoloxygen through the liquid phase did not seem to be satisfac-tory to counteract the decrease in ammonium removal effi-ciency,the immersion level was lowered to55%to increase the availability of oxygen through more air-biofilm contact surface.Consequently,the volumetric loading rate increased (factor1.7)due to the decrease in reactor volume(day210, Fig.1).This action allowed higher ammonium removal effi-ciencies due to higher AerAOB activities(factor3).AnAOB activity increased with a similar factor as the volumetric loading rate(1.8compared with1.7)consequently resulting in an increased imbalance between these two groups of bac-teria(Table1;phase V).Moreover,although the FNA in-creased with a factor2,the NOB activity increased with a factor7,resulting in a relative nitrate production of30% (Table1;phase V).As NOB activity prevented good total nitrogen removal efficiencies,the immersion level was in-creased again to78%(day263;Fig.1).This resulted indeed in a lower NOB activity(Table1;phase VI).However,also the AerAOB activity decreased with the same factor,due to the lower availability of atmospheric oxygen.Therefore,the reactor was subsequently operated again at the lower immer-sion level(55%)to allow sufficient aerobic ammonium conversion.The latter allowed a stable removal efficiency of 42%.The AnAOB activity gradually increased to a stable anoxic ammonium conversion rate of529mg NL−1day−1. During the synthetic phase,no changes in AerAOB, AnAOB,and NOB abundance were measured with qPCR (Fig.S1in the ESM).The effluent quality was however not optimal as still high nitrite(around15mg NL−1)and nitrate (around13mg NL−1)levels were detected.Effect of COD/N increaseThe synthetic feed was gradually changed into pretreated sewage by diluting raw sewage and adding additional nitro-gen to obtain a certain COD/N ratio.During the first3weeks of this period(Fig.2),the COD/N ratio was gradually increased from0.5to2.Due to the short adaptation periods (1week per COD/N regime),the performance was unstable (Fig.2;Table2,phases VIII–XI).Compared with the end of the synthetic period(phase VII),operation at a COD/N ratio of2(phase XI)resulted in a sharp decrease in nitrite accu-mulation(Fig.2)and an increase in the ammonium and nitrate levels.This indicated increased NOB activity(factor 4),decreased AerAOB(factor3)and decreased AnAOB (factor2)activity(Tables1and2).To allow higher nitrogen removal rates,the HRT was increased from0.94to1.1h,by decreasing the influent flow rate.Moreover,the feeding regime was changed from two pulses of10min in1h to one period of20min/h.These actions did not significantly decrease the effluent nitrogen concentration(Fig.2)and did not influence the microbial activities(Table2,phase XII). Therefore the loading rate was again increased to the levels before phase XII.However,the single-pulse feeding wasmaintained.This resulted in high ammonium removal effi-ciencies and therefore low ammonium effluent concentra-tion around dischargeable level(4±1mg NH4+–NL−1; Fig.2).Nitrate and nitrite accumulation were not counter-acted by denitrification as only0.02mg CODL−1day−1wasremoved.Therefore,nitrite and nitrate levels were still toohigh to allow effluent discharge.The total nitrogen removalefficiency(42%)and rate(549±83mg NL−1day−1or1,098±106mgNm−2day−1)at COD/N ratios of2wassimilar as during the synthetic period(phase VII).Comparedwith the reference period at29°C,the total nitrogen removalrate did not changed significantly(470±43versus549±83mgNL−1day−1at high and low temperatures,respectively).The22%lowered removal efficiency was merely due to anincreased nitrogen loading rate.Nitratation and NO/N2O emissionsAt the end of the synthetic phase(phase VII)and the end ofthe experiment(phase XIII),the total nitrogen balance of thereactor was measured.A total nitrogen balance was obtainedby measuring all nitrogen species(NH4+,NO2−,NO3−,NH2OH,and N2O)in the liquid phase and N2O and NO inthe gas phase.A constant air flow,diluting the emitted N2Oand NO concentrations was created over the reactor tomeasure gas fluxes over time.The effect of the loading rate,feeding pattern,and concentration of nitrite and ammoniumon the total nitrogen balance in the reactor were tested(Table3).NH2OH measurements showed low concentra-tions(<0.2mg NL−1)in all tests,making it difficult to linkthe profiles with the N2O emission.Lowering the loading rate by increasing the HRT(Table3,test B)increased the DO values and allowed higherDO fluctuations over time at synthetic conditions.Moreover,NOB activity increased significantly resultingin lower total nitrogen removal efficiencies and high levelsof nitrate in the effluent(Table3,test B).The relative N2Oemissions did not change and were relatively high(6%of Nload).However,the concentration of N2O in the liquid andin the gas phase decreased with a factor2(Table3).When pretreated sewage was fed to the reactor,theOLAND RBC was operated at lower nitrite concentration,while similar ammonium and nitrate concentrations wereobtained(Table3,test C).The lower nitrite concentrationshowever did not result in lower N2O emission rates.Whenthe feeding regime was changed to a more continuous-likeoperation(4pulses/h),the N2O emission increased signifi-cantly,while NO emission remained constant(Table3,testD).Due to the lower ammonium removal efficiency(65compared with81%),but similar relative nitrite and nitrateaccumulation rate,the total nitrogen removal efficiencydecreased.Appl Microbiol BiotechnolWhen a nitrite pulse was added just after feeding,about 20mg NO 2−–NL −1was obtained in the reactor.This did increase the NO and N 2O emissions significantly (p <0.05)compared with the same feeding pattern (Table 3,tests C –E).Although similar constant total nitrogen removal efficien-cies were obtained during this operation,a significant (p <0.05)decrease in the relative nitrate production was observed.The latter was mainly caused by a global increase in AnAOB activity.In the last test (F),the influent ammo-nium concentration was doubled,leading to higher ammo-nium and also FA concentrations (1±0.4mg N L −1compared with 0.1±0.4mg NL −1).Due to overloading of the system,the total nitrogen removal efficiency decreased.However,at these conditions a lower relative nitrate pro-duction was obtained;due to a decrease in NOB and in-crease in AnAOB activity (Table 3,test F).Together with this,increased NO and N 2O emissions were observed.As the influence of the nitrogen loading and DO concentration could be considered minor in this test range (Fig.S2in the ESM ),these tests show a relation between increased NO emissions and decreased relative nitrate productions (Table 3).When the activity during the feeding cycle was studied in more detail,it could be concluded that the highest nitrogen conversion rates took place during the feeding period,which was characterized by a high substrate availability and high turbulence (Fig.3).As the HRT is only 1h,the reactor volume is exchanged in 20min.During this phase,ammo-nium increased,while nitrite and nitrate concentrations de-creased due to dilution (Figs.S3,S4,and S5in the ESM ).The NOB/AnAOB ratio was around 1,which means that NOB were able to take twice as much nitrite thanAnAOBFig.2Phases VIII –XIII:effect of COD/N increase on the volumetric rates (top )and nitrogen concentrations (bottom ).Data during the N balance tests (days 424–431)were not incorporated in the figure but are shown in Table 3Appl Microbiol BiotechnolTable 3Operational parameters and nitrogen conversion rates during the six different RBC operations which differ from feeding composition and feeding regime (volume at 2.5L and 50%immersion of the discs,days 307–309for synthetic feed,and days 424–431)Reactor phaseVII (synthetic)XIII (pretreated sewage)Test A a B C a D E -F Additive––––NO 2−NH 4+Feeding regime (pulses/h)221411Total N loading rate (mg NL −1day −1)1,1695851,3401,5541,7372,718Temperature water (°C)15±0.316±0.2*14±0.415±0.1*16±0.1*15±0.4DO (mg O 2L −1) 2.9±0.1 3.7±0.6* 4.0±0.1 3.2±0.1* 3.3±0.1* 3.2±0.1*pH (-)7.6±0.067.6±0.057.6±0.047.6±0.017.6±0.027.8±0.02*Ammonium out (mg NL −1)9±1 1.4±1*11±319±3*12±158±4*Nitrite out (mg NL −1)14±213±16±16±0.418±2*9±0.3*Nitrate out (mg NL −1)17±337±6*18±216±1*18±0.420±0.4NH 4+oxidation rate (mg NL −1day −1)895±22509±2*1,051±73957±891,053±161,285±93*Relative nitrite accumulation (%)25±320±1*14±315±18±4*15±1Relative nitrate production (%)36±876±6*48±147±342±2*34±3*Total efficiency (%)38±417±4*35±328±4*32±227±4*AerAOB activity (mg NH 4+–NL −1day −1)658±88469±17*827±44781±57795±30938±46*NOB activity (mg NO 2−–NL −1day −1)174±59299±28*375±38342±24*362±13277±18*AnAOB activity (mg N tot L −1day −1)205±3849±13*234±20218±29263±15*354±49*N 2O in liquid (μg NL −1)64±4630±22*78±12104±29*61±1374±4NO emission (mg Nday −1)0.53±0.03n.d.0.66±0.060.74±0.08 1.65±0.18*0.82±0.1*N 2O emission (mg Nday −1)151±2893±23*170±19179±6*274±37*202±18*%N 2O emission on loading5.1±1.06.4±1.6*5.0±0.64.5±0.2*6.2±0.8*3.0±0.3*aReference period for synthetic and pretreated sewage*p <0.05,significant differences compared with referenceperiod Fig.3Detailed NO/N 2Omonitoring during the reference test (Table 3,test C)and when nitrite was pulsed (Table 3,test E)and effect on AerAOB,AnAOB,and NOB activity during the different phases of the feeding cycle.Significant differences in AerAOB,AnAOB,NOB,and NO/N 2O concentration compared with the reference period areindicated with asterisks ,circles ,double quotation mark ,and plus sign ,respectivelyAppl Microbiol Biotechnol。

TREATMENT OF DOMESTICWASTEWATER BY ENHANCEDPRIMARY DECANTATION AND SUBSEQUENT NATURALLYVENTILATED TRICKLING FILTRATIONLINPING KUAI, WIM KERSTENS, NGUYEN PHU CUONGand WILLY VERSTRAETECentre for Environmental Sanitation, Faculty of Agricultural and Applied Biological Sciences,University of Gent, Coupure links 653, 9000 Gent, Belgium(* author for correspondence, e-mail: willy.verstraete@rug.ac.be)(Received 16 January 1998; accepted 22 June 1998)Abstract. To treat household wastewater, a sequence of ‘primary decantation–trickling filter percolation’ was applied in a lab-scale designed treatment system. Poly-electrolyte was used as coagulant toenhance the primary treatment and charcoal was used as carrier material in the trickling filters. Oxy-gen was supplied to the trickling filters by means of natural ventilation. In the labscale system, theenhanced primary stage removed more than 91% of the suspended solids (SS), and 79% of the totalchemical oxygen demand (CODt). The subsequent trickling filtration brought a complete nitrificationto the wastewaters at a volumetric loading rate (Bv) of 0.7–1.0 g CODt L−1 d−1.Onaverage,theconcentrations of the CODt and SS in the final effluents were about 55 and 15 mg L−1 respectively.With respect to phosphate, physico-chemical removal was the dominant process. About 46–62% oftotal P was removed from the tested wastewaters. The integrated treatment system also achieved a fairdegree of hygienisation. The numbers of total coliforms, fecal coliforms and fecal streptococci weredecreased by 2–4 log units. The sludge production of the entire treatment system was about 1.7%(v/v) of the treated wastewater. Only primary sl udge was produced; secondary sludge produced in thetrickling filters was negligible. The cost savings in terms of minimization of sludge production andaeration energy are estimated to be substantial (i.e. some 50%) relative to a conventional activatedsludge system.Keywords: charcoal, coagulation, cost evaluation, household wastewater, nitrification, pathogenremoval, poly-electrolyte, sedimentation, small-scale, trickling filter1.Introduction2.Water pollution in many developing regions causes serious problems. Often thepopulation is living in small villages which are scattered in the countryside. Theincrease of the population and the improvement of people’s daily life in these areasresult not only in an increase of the volume of wastewater, but also in a changeof the wastewater composition which tends to contain more chemicals such asdetergents. Change of the nightsoil system to the flush toilet brings about 90% ofthe nightsoil into wastewater (Ukita et al., 1993). Direct discharge of nightsoil intolocal waters endangers the hygienic quality. Although no systematic epidemiological studies have been conducted in developing countries, it is generally assumedWater, Air, and Soil Pollution 113: 43–62, 1999.© 1999 Kluwer Academic Publishers.Printed in the Netherlands.44LINPING KUAI ET AL.that the direct discharge of raw nightsoil is responsible for a high risk of infectiousdisease transmission in many rural regions of the developing countries (Schertenleib, 1995). Water shortage in arid and semi arid areas can necessitate the reuseof wastewater for local irrigation (Mandi et al., 1993). Treatment of this potentialresource is imperative to avoid sanitary risks before re-use (Hespanhol, 1990).The main objective of wastewater treatment is to dispose the treated effluentwithout causing an adverse impact on the ecosystem of the receiving water body.For this reason sewage treatment always includes the reduction of the concentrationof at least one of the four most important constituents of sewage: (1) suspendedsolids; (2) organic matter; (3) nutrients (notably nitrogen and phosphorus); and(4) pathogenic organisms (Van Haandel and Lettinga, 1994). Up to now, the western model of sewage treatment is the dominant one leading the environmental technological development over the world. However, the techniques which havebeen developed to achieve high levels of N and P removal, might not be applicablein many developing countries because of limited financial and energy resourcesavailable (Larsen and Gujer, 1997; Netter et al., 1993). Yet, since agriculture re-quires a substantial amount of water and nutrient input, safe reuse of treated sewagein these regions can free high quality water for other purposes and can supplementchemical fertilizers. Efficient use of resources will lead to a minimal increase ofentropy and will require an active rather than a reactive approach (Larsen andGujer, 1997). It is therefore of importance in many developing areas to treat sewageto the extend that it can be safely reused on the land. If the wastewater has to bedischarged to the local water-bodies, it should be treated so that the quality ofthe receiving water can be maintained at a level for safe drinking with no risk ofpathogens, no bad smell, no depletion of O2 and no toxicity from NHC4 or NH3.Hence, removal of pathogens and organic matter, in addition to achieving a highlevel of nitrification are essential.Centralized sewage treatment plants are generally not suitable for rural areas.Collection of domestic wastewater and transport to a distant treatment plant isexpensive at low population density (Netter et al., 1993; Paulsrud and Haraldsen,1993). On-site treatment using small scale wastewater treatment plants is the mostcost-effective alternative. The treatment technology for small wastewater streamsshould be based on locally available and serviceable materials and equipments thatare simple and economical to operate. Those low technical skills needed are the most appropriate ones (Ødegaard, 1997). A primary settling tank combined witha t rickling filter based on natural materials and natural ventilation might be anappropriate solution for water pollution control in most rural areas, especially indeveloping countries. The small-scale treatment unit designed for individual house holds or small communities can be compact and closed without causing negativeimpact on the landscape and without producing noise or odors. It can handle fluctuations in hydraulic and organic loads without variation in removal efficiencies(D’Antonio et al., 1997).TREATMENT OF DOMESTICWASTEWATER 45TABLE IThe main characteristics of the two types of wastewater(Average Standard deviation)Parameter UnitThe MHWThe SHWCODtmg L−1 500.0±376 2865.0±3822CODs mg L−1 161.0±42 205.0±134SS mg L−1 673.0±425 2555.0±3103Total N mg L−1 41.0±13 204.0±161Kj-N mg L−1 41.0±13 202.0±161NHC4 -N mg L−1 30.0±1063.0±28NOx−-N mg L−1 0.0 2.03Total Pmg L−1 8.0±3 26.0±13PO3C4 –Pmg L−1 4.0±3 13.0±4pH 7.2±0.4 7.7±0.3The purpose of our research was to develop a treatment process that will guarantee the technical asibility in rural areas, taking into consideration factors suchas the construction and maintenance costs, the availability of construction materialsand equipment, the limitation of land for anindividual household, the productionof noise and odor as well as specialized labor and skills, especially for developingcountries.2. Materials and Methods2.1. WASTEWATERTwo types of domestic wastewaters were tested in the experiments. One was amultiple households wastewater (MHW) obtained from a municipal wastewatertreatment plant located in Gent, Belgium. The other was a single household wastewater (SHW) collected from a family living in the rural area of Avelgem, Belgium.The wastewater samples were taken generally once a week from the sites andstoredat 4 C in the lab before feeding. The main characteristics of the wastewaters aregiven in Table I. The SHW was about 3 times more concentrated than the MHWbecause the water consumption of the family was relatively low and rainfall wasnot entering the wastewater collecting system. Instead of 180 L per inhabitantequivalent (I.E.) per day, discharged to the municipal wastewater treatment plant,the family only discharged maximally 70 L (I.E.)−1d−146LINPING KUAI ET AL.2.2EXPERIMENTS2.2.1. Integrated Treatment of the Multiple Households WastewaterThe process diagram used for the treatment of the MHW is illustrated in Figure 1.The lab-scale integrated system consisted of an influent tank of 30 L, a primarysettling tank of 6 L and a na turally ventilated trickling filter of 2.5 L. To enhancethe natural aeration, as illustrated in Figure 2, the trickling filter was modified basedTREATMENT OF DOMESTICWASTEWATER 47on a conventional trickling filter by placing a net column inside to improve the O2supply. This inner net column was made with PVC and about 80% of the wall areawas holes with 1 cm in diameter. The dimensions of the modified trickling filterwere 1.0 m in height, 0.08 m in diameter of the outside PVC column and 0.056 mof the inside net column. A commercial charcoal (Charbon de bois Epure, S. A.Delhaize, Brussels, Belgium) was used as carrier material, it was grinded toparticles with diameter of about 2 cm before use. Aeration occurred via natural contactwith air entering through the inside net column. Supplemental forced aeration wasnot imposed.The raw MHW was batch fed into the influent tank once a day. It was pumpedsemi-continuously from the influent tank into the primary settling tank in upwarddirection, i.e. 10 min every 15 min. During the pumping period, the influent was si-multaneously mixed by a mixer to avoid accumulation of solids in the influent tank.Chemical coagulation was not applied in the primary stage. The supernatant fromthe primary settling tank automatically flowed into the subsequent trickling filterby gravity force. It percolated over the carrier in downward direction. Operation ofthe trickling filter was started at a low loading rate. The loading rate was increasedstep-wise during the first few weeks depending on the removal e fficiencies of totalchemical oxygen demand (CODt) and NHC4 -N. After an adaptation period of 4weeks, the flow rate was controlled around 25 L d−1, and the HRTs (hydraulicretention time) of the primary settling tank and the trickling filter were 5.8 and2.4 hr, respectively. The volumetric loading rate (Bv) of the trickling filter wasabout 1.0 g COD L−1d−1corresponding to 0.35 g Kj-N L−1d−1(based on theCODt and Kj-N concentrations of the outflow from the primary settling tank). During the whole experimental period, the integrated treatment system was operated atroom temperature varying around 20 C.2.2.2. Integrated Treatment of the Single Household Wastewater2.2.2.1. (a). Primary Coagulation and Sedimentation Tests Before operation ofthe integrated treatment system, a jar test using chemical coagulation and sedimentation to pre-treat the highly concentrated wastewater was carried out. Polyelectrolyte (Praestol BC 611, ChemischeFabrik Stockhausen Gmbh, Krefeld, Germany) was used as the coagulant. Five different dosages of poly-electrolyte, namely0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 mg L−1, were tested. The wastewater sample (800 mL) and theneeded amount of the poly-electrolyte stock solution (1 g L−1) were added into1000 mL beakers. After mixing at 250 rpm for 2 min, the mixed liquors wereallowed to settle for 30 min and the supernatants were taken for analyses. The testswere performed twice with samples obtained at two different times.2.2.2.2. (b). Operation of the Integrated T reatment System The process diagramof the integrated system operated for the SHW was similar to the one used for theMHW treatment. However, the individual treatment units were slightly different.The volume of the influent tank and the primary settling tank were smaller, only48 LINPING KUAI ET AL.10 and 4 L, respectively. The employed trickling filter was a conventional tricklingfilter constructed with a PVC column with a total volume of 2 L, 1.0 m in heightand 0.05 m in diameter. The detailed structure is demonstrated in Figure 1. Freshcharcoal, grinded and sieved to a particle size of about 2 cm, was used as carriermaterial. On the top of the trickling filter, a layer of 10 cm of crushed stones with0.5 to 1 cm in diameter, was placed in order to improve the influent distribution.About 8 small holes, with 1 cm in diameter each, were scattered on the wall of thePVC column close to the bottom. Aeration occurred via contact with air enteringthrough the aeration holes.Based on the results of the primary coagulation and sedimentation tests, chemical coagulation was applied in the primary treatment stage for this highly con centrated SHW. The raw SHW and about 5 mg L−1of poly-electrolyte (PraestolBC 611) were batch added into the influent tank once a day. They were mixed inthe influent tank and pumped into the primary settl ing tank in upward direction simultaneously, for 10 min in every 15 min. The consequential treatment procedureswere similar to those applied for the MHW treatment. After an adaptation periodof 4 weeks, the flow ratewas controlled around 10 L d−1. The Bv of the tricklingfilter fluctuated around 0.7 g CODt L−1d−1which was about 30% lower than theone applied for the MHW treatment. The nitrogen loading rate was about 0.3 gKj-N L−1d−1. The HRT was about 9.6 hr in the primary settling tank and 4.8 hr inthe trickling fil ter. The primary sludge was removed at intervals from the primarysettling tank, e.g. once every two weeks. The system was also operated at roomtemperature around 20 C.2.3. ANALYSESThe routine analyses were carried out once a week unless stated otherwise. Theinfluent and effluent samples were collected proportionally everyday and stored at4 C until analyses. The parameters of COD, Kj-N (Kjeldahl-N), NHC4 -N, NOx -N,andPt (total P) were determined in accordance to the Standard Methods (APHAet al., 1992). Total coliform (TC), fecal coliform (FC) and fecal streptococci (FS)were enumerated by plate count techniques as described by Kersters et al. (1995).3. ResultsThe treatment performance of the laboratory integrated systems were monitoredby determining the removal of (1) suspended solid; (2) organic materials (CODt);(3) nutrients (N and P); and (4) pathogenic organisms (TC, FC and FS).TREATMENT OF DOMESTICWASTEWATER 49TABLE I IThe results of the jar tests on the raw SHW3.1. CODt AND SS REMOVAL3.1.1. Primary Jar Tests to Pre-Treat the SHW by Coagulation and SedimentationThe results of the jar tests by coagulation and sedimentation are described in Table II. For the concentrated SHW, simple sedimentation gave an insufficient andunstable removal of COD t which varied from 23 to 73%. The poly-electrolyteshowed to be highly effective to enhance the CODt removal. By adding 5 mg L−1of poly-electrolyte, the removal percentage of CODt increased to 93%.3.1.2. The Integrated SystemThe change of the CODt concentrations during the whole experimental period areshown in Figure 3. The influent CODt and SS in both types of wastewaters variedconsiderably. For the SHW, up to 15700 mg L−1of CODt was measured in week15 coupled with a high SS concentration of 11200 mg L−1. The variation of theMHW was slightly lower because the wastewater was taken after a grit chamberwhere large particles had already been removed. However, as shown in Figure 3,the influent CODt was still often up to 1000 mg L−1, which was 2 times as high asi tsmean value.The high CODt mainly resulted from the high SS concentration. The primarytreatments removed the major part of CODt and SS from both types of wastewaters.As indicated in Table III, although in the treatment of MHW, poly-electrolyte wasnot used in the primary stage, straight-forward sedimentation still removed 79% ofCODt and 91% of SS, leaving a stable CODt concentration in the effluent rangingfrom 80 to 250 mg L−1. For the SHW, combination of chemical coagulation andsedimentation could even remove up to 95% of CODt and 99% of SS, respectively.Fluctuation of the loading rates was successfully smoothed. The effluent after theprimary stage had a relatively stable concentration of CODt, mostly between 100to 200 mg L−1.The subsequent trickling filters polished the outflows from the primary settlingtanks to a high quality. The final effluents of the MHW and SHW contained a lowCODt concentration of 55 and 50 mg L−1as well as a low SS concentration of 17and11mgL−1in average, respectively.50 LINPING KUAI ET AL.Figure 3.The concentration of CODt in the different process stages. A) The multiple households wastewater; B) The single household wastewater.In total, the entire processes removed respectively about 98% of CODt and 99%of SS fromthe SHW, and about 89% of CODt and 98% of SS from the MHW.3.2. REMOVAL OF NITROGENThe concentrations of nitrogen compounds in the different treatment processes areindicated in Figure 4. The removal percentages are listed in Table IV. As shown inTable IV, for both types of wastewaters, the pri mary treatments were shown sufficient for organic N removal but not for NHC-N removal. For the MHW, the singlesedimentation stage removed about 15% of the Kj-N which was totally due to theremoval of organic N. Of the residual Kj-N in the outflow, 9% was contributedby organic N. For the SHW, about 69% of Kj-N was removed in which only 3%was due to the removal of NHC4 -N. The primary coagulation and sedimentationremoved almostall the organic N.Of the residual Kj-N in the outflow, only 1.6%came from organic N.The trickling filters converted the residual Kj-N mainly to NO−x -N by means ofnitrification. Figure 5 shows that the two trickling filters were all characterized bya start-up period of about 3 weeks with a limited efficiency of nitrification for bothtypes of wastewaters. Significant decrease of NHC4 -N concentration and increase ofNO−x -N concentration in the effluents of the trickling filter occurred simultaneouslyfrom week 3 onwards. After an adaptation period of about 4 weeks, the removalrates of NHC4 -N in the trickling filters increased to 0.30 and 0.25 g NHC4 -N L−1Figure 4.The change of N concentration in the different treatment stages. A) The multiple householdswastewater; B) The single household wastewater.d−1for the MHW and SHW, respectively. On average, about 60% of NHC4 -N wasconverted to NOxN from the MHW and 75% from the MHW.The total N removal was different for the two types of wastewaters. For theMHW, the entire system removed about 49%of total N, in which 15%was removedby the primary sedimentation and another 34% was contributed by the tricklingfilter as partial denitrification occurred in the reactor. The final effluent of theMHW contained 3 mg L−1ofKj-Nand18mgL−1of NO−x -N. For the SHW,the primary coagulation and sedimentation processes removed about 69% of theotal N. However, only a very limited removal of total N, about 2%, was achievedTREATMENT OFin the trickling filter. The final effluent of the SHW contained about 14 mgL−1ofKj-Nand46mgL−1of NO−x -N, respectively.3.3. REMOVAL OF PHOSPHORUSor both types of wastewaters, removal of total phosphorus (Pt) was stable duringhe whole experimental period. As shown in Table V, Pt was mainly removed inhe primary stage. Physico-chemical removal of Pt was the dominant pathway. Inotal, the removal of Pt was about 49% from the MHW and 62% from the SHW.The residual Pt in the final effluents was about 4 and 10 mg L−1, respectively.3.4. HYGIENEThe removal of pathogens from the two wastewaters by the integrated treatmentas quite similar. As shown in Table VI, a fair degree of hygienisation was achieved.n total, the numbers of total coliforms (TC), fecal coliforms (FC) and fecal streptococci (FS) were reduced by 2–4 log units. The reduction was mainly broughtbout by the trickling filters.TREATMENT OF DOMESTICWASTEWATER 553.5. SLUDGE PRODUCTION3.5.1. Primary SludgeThe MHW was less concentrated than the SHW and chemical coagulation wasot imposed in the primary stage. Therefore, sedimentation of the MHW did notprodu ce much sludge. In the first 2 months, the volume of the sludge accumulatedin the primary settling tank increased slowly to 4 L. After that, increase of thesludge volume did not proceed. During the whole operational period of 5 months,there was no need to discharge sludge from the primary settling tank. For the SHW,the primary coagulation and sedimentation stage produced about 1.7% (v/v) ofsludge relative to the total flow of the raw wastewater. The sludge produced wasregularly withdrawn from the primary settling tank once every two weeks. Thewaste sludge was a mixture of under-flow and skimmed floating material and hada concentration of 40 to 50 g SS L−1.3.5.2. Secondary Sludge Secondary sludge produced in the trickling filters was negligible for the two typeso f wastewaters. This was reflected by the low SS concentrations in the effluents;a secondary decanter was not necessary. The two test-runs revealed that the integrated system was stable in operation over an observation period of more than 5months under the given lab-scale conditions. Clogging was never experienced inthe trickling filters.4. Discussion4.1. COAGULATION AND SEDIMENTATIONIn practice, both the quantity and quality of wastewater can vary drastically. It iswell known that the smaller the population, the more pronounced the variation.Whereas larger cities exhibit a variation factor, defined as maximum load/meanload of 1.5–2, the factor may be as high as 5 in small domestic residential areas(Markus, 1997). Therefore, the dynamics of flow and load variations ask for equalization and pretreatment. Especially, when applying high rate treatment systemswith short retention times such as trickling filters and rotating biological contactors, a stable loading rate is an important prerequisite for satisfactory treatmentperformance. Pretreatment also ensures the high quality of the final effluent. Itcan effectively remove the recalcitrant COD fraction as this fraction is mainlyassociated with particles and colloids (Yoshimasa and Yoshihiko, 1997; Rustenet al., 1997).In the treatment of theMHWwith the integrated system, during the first 3 weeksof operating, the COD removal by the simple sedimentation step was not as goodas the one combined with coagulation in the treatment of the SHW (Figure 3).However, from week 4 onwards when enough amount of sludge was accumulated56 LINPING KUAI ET AL.in the primary settling tank and the sludge bed had built up, increase of the CODtremoval was observed. This fact indicated that the sludge bed could serve as asorption layer capturing particles and colloids effectively.For the SHW, the primary jar tests with coagulation and sedimentation showedthat for the concentrated SHW, simple sedimentation was insufficient and unstableto buffer the high variation of the wastewater (T able II). This poor and variableperformance was mainly due to the poor settling characteristics of the SHW.Whenthe wastewater contained much toilet wastes, which also happened frequently during the experimental period, it became very turbid with colloids and settled poor ly.Yet, by adding 5 mg L−1of poly-electrolyte, the removal of the CODt increasedto 93%. This clearly indicated that combination of coagulation and sedimentationwas necessary to ensure a high and stable performance of the primary settling tank.During the operation of the integrated treatment system, the high performance andthe considerable equilibrium capacity of the primary coagulation and sedimentation processes were furtherconfirmed (Figure 3). Not only did it remove about79–95% of CODt, but also absorbed the peak CODt, which varied from 240 to15800 mg L−1. Consequently, the influence of a shock load to the downstreamtrickling filter was alleviated and a high performance was guaranteed.The hydraulic retention time of about 6–10 hr in the two primary settling tankswas relatively long compared with a normal primary settling time of 1–2 hours.The reason of applying the large primary settling tanks was to make them functionboth as primary sludge separation and sludge storage tanks. Long time retention ofsludge in the primary settling tanks, especially in the case of the MHW treatment,resulted in sludge hydrolysis and digestion. Because of sludge hydrolysis and digestion, the sludge production was reduced and a slightly increase of the NHC4 –Nconcentration in the effluent, from 30 to 32 mg L−1, was observed (Figure 4).4.2. TRICKLING FILTERA trickling filter purifies wastewater through physical filtration/adsorption and bi ological degradation. Generally, at least two biological processes are involved ina trickling fil ter, i.e. COD degradation and nitrification. In some cases, partialdenitrification occurs simultaneously (Bertanza, 1997).During the experimental period of 5 months, the effluent CODt from the twotrickling filters remained below 70 mg L−1. Mostly, they were below 60 mg L−1.Without a secondary decanter, the SS concentration in the effluents was around10–20 mg L−1, which indicated that sludge production in the trickling filters wasnegligible. Based on the above fact, backwashing of the trickling filters was notnece ssary. In comparison, a survey of 43 small Norwegian activated sludge plantswith co-precipitation showed a median effluent COD concentration of 70 mg L−1 andSSof24mgL−1(Rusten et al., 1997). The nitrification capacity in the two testruns reached 0.2–0.3 g Kj-N L−1d−1at a Bv of 0.7–1.0 g COD L−1d−1(Figure 4).It was equivalent to or even higher than that in a conventional activated sludgeTREATMENT OF DOMESTICWASTEWATER 57system working at a low loading rate (Muller et al., 1995). Similar results werereported by Netter et al. (1993). However, the latter authors applied a loading rateto the biofilter of only 0.1–0.2 g COD L−1d−1and forced aeration was supplied.An important aspect of the biological processes in a trickling filter is the oxygensupply. In theory, oxygen diffusion from gas to liquid, and then from liquid tobiomass surface is much slower than diffusion from gas phase to biomass surfacedirectly (Tijhuis, 1994). Biomass in a trickling filter can only gain oxygen from airin the open spaces. Gas transport i s the limiting process in all types of biologicallyactive filters (Schwager and Boller, 1997). The trickling filters used in this work,especially the modified one with an inner net column, created good conditions for air supply. The low hydraulic loading rate, obtained by not applying recirculation, avoided liquid flooding. Without liquid resistance, high efficiency of oxygentransfer was ensured. Therefore, the oxygen supply, based solely on the naturalventilation through the aeration holes or the inner net was satisfactory. The latterwas demonstrated by the efficient COD removal, the negligible sludge productionand the effective nitrification.Charcoal has been widely used as an adsorbent in the wastewater treatment (Abeet al., 1993; Funke et al., 1994; Abe et al., 1993; Khalfaoui et al., 1995) because itssurface characteristics are similar to those of granular activated carbon. However,its application as carrier material in a biofilm reactor was scarcely reported. Besideshaving many essential properties, such as a high specific surface area and a highvoid ratio, being durable and light-weight, a maxtrixto be used for sewage treatment in rural areas should also be cheap and locally available. Charcoal, the supportused in the tested trickling filters, fulfilled the abov e requirements. It can be easilycrushed to a required particle size, i.e. 2 to 3 cm. The low density of charcoal, lessthan 1 kg cm−3, makes it more favorable than other materials such as crushed rock,slag etc. With many micro-pores on the surface, charcoal provides good conditionsfor micro-organisms to attach. Fresh charcoal is also a good adsorbent which canaccumulate sufficient organic matter and nutrients for biomass to grow. During thefirst few weeks before the biofilm builds up, the adsorption can also c ompensate theinsufficient biodegradation of COD. Therefore, it can ensure a low effluent CODduring the whole experimental period (Figure 3).In a nitrifying trickling filter, removal of total N can occ ur through the simultaneous denitrification in the anoxic micro-zones within the biological floc (Bertanza,1997). As noted in Table IV, the two trickling filter test-runs showed differentperformance for total N removal from the two types of wastewaters. During thetreatment of the SHW, the trickling filter only converted NHC4 -N to NOx -N withoutdenitrification. However, in the treatment of the MHW, trickling filtration is considered to remove 34% of the total N by means of denitrification. The differencewas due to two factors. One was the different loading rates (Bv) applied to the two trickling filters. The former was treated under a low Bv, e.g., 0.7 g COD L−1d−1,while the latter was treated at a relatively high Bv of 1.0 g COD L−1d−1. The higherBv might create more anoxic micro-zones in the filter which allow denitrification58 LINPING KUAI ET AL.to occur. The other factor was the different ratio of CODt:Kj-N in the influents ofthe two trickling filters. The former had a ratio of 2.2, while the latter had a ratio of3.3. The higher COD:Kj-N ratio resulted in the higher denitrification driving force(Watanabe, et al., 1995).Drawbacks of the system are the absence of an effective denitrification and Premoval. In regions where local soil is poor in nutrients and agricultural fertilizersare relatively expensive or scarce, the so treated sewage could be used for irrigationand fertilization. In industrialized countries however, further improvement of thedenitrification and P removal processes is necessary in order to make this integratedsystem acceptable for implementation in rural areas.4.3. HYGIENEPrimary or secondary wastewater treatment systems generally have poor disinfecting capacity. According to Block (1982) and Farrell et al. (1990), the removalefficiency of fecal coliforms (FC) can only reach 60 to 99% in a con ventionalactivated sludge or a biofilm process. Tremblay et al. (1996) reported that about56% reduction of FC was observed in their trickling bio-filtration process. Our twotrickling filter test-runs disinfected the wastewater fairly well after the adaptationperiods. They reduced the total coliforms (TC), fecal coliforms (FC) and fecalstreptococci (FS) by 2–4 log units. The residual TC in the effluents was less than1000 TC per 100 mL (Table VI). According to the guidelines of microbiologicalquality for irrigation posted by the World Health Organization (WHO), i.e. <1000TC per 100 mL, the treated wastewaters can be used for irrigation of all cropswithout further disinfection (Janssens and Verstraete, 1996; Ghrabi et al., 1993).The main principle of disinfection by a biological process is believed to be basedon sorption, die-off and the predation of micro-organisms by macro-organisms.The high variety of macro-organisms in the trickling filters might be the majorcontributor to the good effect of disinfection. However, the disinfection appearedsimultaneously with nitrification. This fact was in good agreement with the findingsof Lens et al. (1994). The good disinfection effect of their peat。

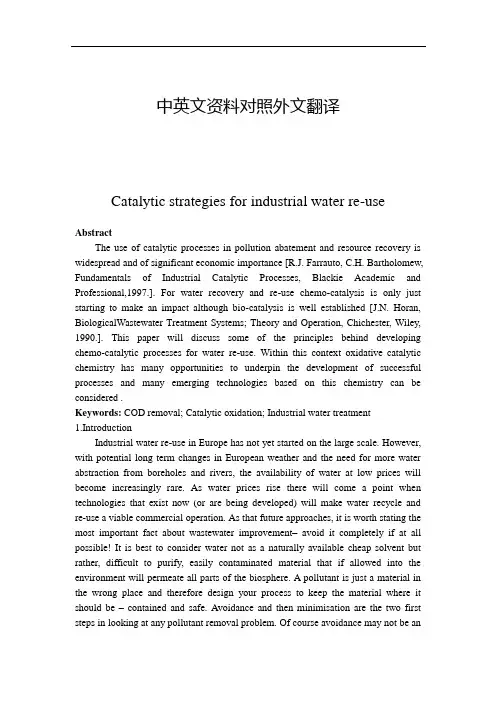

中英文资料对照外文翻译Catalytic strategies for industrial water re-useAbstractThe use of catalytic processes in pollution abatement and resource recovery is widespread and of significant economic importance [R.J. Farrauto, C.H. Bartholomew, Fundamentals of Industrial Catalytic Processes, Blackie Academic and Professional,1997.]. For water recovery and re-use chemo-catalysis is only just starting to make an impact although bio-catalysis is well established [J.N. Horan, BiologicalWastewater Treatment Systems; Theory and Operation, Chichester, Wiley, 1990.]. This paper will discuss some of the principles behind developing chemo-catalytic processes for water re-use. Within this context oxidative catalytic chemistry has many opportunities to underpin the development of successful processes and many emerging technologies based on this chemistry can be considered .Keywords: COD removal; Catalytic oxidation; Industrial water treatment1.IntroductionIndustrial water re-use in Europe has not yet started on the large scale. However, with potential long term changes in European weather and the need for more water abstraction from boreholes and rivers, the availability of water at low prices will become increasingly rare. As water prices rise there will come a point when technologies that exist now (or are being developed) will make water recycle and re-use a viable commercial operation. As that future approaches, it is worth stating the most important fact about wastewater improvement–avoid it completely if at all possible! It is best to consider water not as a naturally available cheap solvent but rather, difficult to purify, easily contaminated material that if allowed into the environment will permeate all parts of the biosphere. A pollutant is just a material in the wrong place and therefore design your process to keep the material where it should be –contained and safe. Avoidance and then minimisation are the two first steps in looking at any pollutant removal problem. Of course avoidance may not be anoption on an existing plant where any changes may have large consequences for plant items if major flowsheet revision were required. Also avoidance may mean simply transferring the issue from the aqueous phase to the gas phase. There are advantages and disadvantages to both water and gas pollutant abatement. However, it must be remembered that gas phase organic pollutant removal (VOC combustion etc.,) is much more advanced than the equivalent water COD removal and therefore worth consideration [1]. Because these aspects cannot be over-emphasised,a third step would be to visit the first two steps again. Clean-up is expensive, recycle and re-use even if you have a cost effective process is still more capital equipment that will lower your return on assets and make the process less financially attractive. At present the best technology for water recycle is membrane based. This is the only technology that will produce a sufficiently clean permeate for chemical process use. However, the technology cannot be used in isolation and in many (all) cases will require filtration upstream and a technique for handling the downstream retentate containing the pollutants. Thus, hybrid technologies are required that together can handle the all aspects of the water improvement process[6,7,8].Hence the general rules for wastewater improvement are:1. Avoid if possible, consider all possible ways to minimise.2. Keep contaminated streams separate.3. Treat each stream at source for maximum concentration and minimum flow.4. Measure and identify contaminants over complete process cycle. Look for peaks, which will prove costly to manage and attempt to run the process as close to typical values as possible. This paper will consider the industries that are affected by wastewater issues and the technologies that are available to dispose of the retentate which will contain the pollutants from the wastewater effluent. The paper will describe some of the problems to be overcome and how the technologies solve these problems to varying degrees. It will also discuss how the cost driver should influence developers of future technologies.2. The industriesThe process industries that have a significant wastewater effluent are shown in Fig. 1. These process industries can be involved in wastewater treatment in many areas and some illustrations of this are outlined below.Fig. 1. Process industries with wastewater issues.2.1. RefineriesThe process of bringing oil to the refinery will often produce contaminated water. Oil pipelines from offshore rigs are cleaned with water; oil ships ballast with water and the result can be significant water improvement issues.2.2. ChemicalsThe synthesis of intermediate and speciality chemicals often involve the use of a water wash step to remove impurities or wash out residual flammable solvents before drying.2.3. PetrochemicalsEthylene plants need to remove acid gases (CO2, H2S) formed in the manufacture process. This situation can be exacerbated by the need to add sulphur compounds before the pyrolysis stage to improve the process selectivity. Caustic scrubbing is the usual method and this produces a significant water effluent disposal problem.2.4. Pharmaceuticals and agrochemicalsThese industries can have water wash steps in synthesis but in addition they are often formulated with water-based surfactants or wetting agents.2.5. Foods and beveragesClearly use water in processing and COD and BOD issues will be the end result.2.6. Pulp and paperThis industry uses very large quantities of water for processing –aqueous peroxide and enzymes for bleaching in addition to the standard Kraft type processing of the pulp. It is important to realise how much human society contributes to contaminated water and an investigation of the flow rates through municipal treatment plants soon shows the significance of non-process industry derived wastewater.3. The technologiesThe technologies for recalcitrant COD and toxic pollutants in aqueous effluent are shown in Fig. 2. These examples of technologies [2,6,8] available or in development can be categorised according to the general principle underlying the mechanism of action. If in addition the adsorption (absorption) processes are ignored for this catalysis discussion then the categories are:1. Biocatalysis2. Air/oxygen based catalytic (or non-catalytic).3. Chemical oxidation1. Without catalysis using chemical oxidants2. With catalysis using either the generation of _OH or active oxygen transfer. Biocatalysis is an excellent technology for Municipal wastewater treatment providing a very cost-effective route for the removal of organics from water. It is capable of much development via the use of different types of bacteria to increase the overall flexibility of the technology. One issue remains –what to do with all the activated sludge even after mass reduction by de-watering. The quantities involved mean that this is not an easy problem to solve and re-use as a fertilizer can only use so much. The sludge can be toxic via absorption of heavy metals, recalcitrant toxic COD. Inthis case incineration and safe disposal of the ash to acceptable landfill may be required. Air based oxidation [6,7] is very attractive because providing purer grades of oxygen are not required if the oxidant is free. Unfortunately, it is only slightly soluble in water, rather unreactive at low temperatures and, therefore, needs heat and pressure to deliver reasonable rates of reaction. These plants become capital intensive as pressures (from _10 to 100 bar) are used. Therefore, although the running costs maybe low the initial capital outlay on the plant has a very significant effect on the costs of the process. Catalysis improves the rates of reaction and hence lowers the temperature and pressure but is not able to avoid them and hence does not offer a complete solution. The catalysts used are generally Group VIII metals such as cobalt or copper. The leaching of these metals into the aqueous phase is a difficulty that inhibits the general use of heterogeneous catalysts [7]. Chemical oxidation with cheap oxidants has been well practised on integrated chemical plants. The usual example is waste sodium hypochlorite generated in chlor-alkali units that can be utilised to oxidise COD streams from other plants within the complex. Hydrogen peroxide, chlorine dioxide, potassium permanganate are all possible oxidants in this type of process. The choice is primarily determined by which is the cheapest at the point of use. A secondary consideration is how effective is the oxidant. Possibly the most researched catalytic area is the generation and use of _OH as a very active oxidant (advanced oxidation processes) [8]. There are a variety of ways of doing this but the most usual is with photons and a photocatalyst. The photocatalyst is normally TiO2 but other materials with a suitable band gap can be used [9,10]. The processes can be very active however the engineering difficulties of getting light, a catalyst and the effluent efficiently contacted is not easy. In fact the poor efficiency of light usage by the catalyst (either through contacting problems or inherent to the catalyst) make this process only suitable for light from solar sources. Photons derived from electrical power that comes from fossil fuels are not acceptable because the carbon dioxide emission this implies far outweighs and COD abatement. Hydroelectric power (and nuclear power) are possible sources but the basic inefficiency is not being avoided. Hydrogen peroxide and ozone have been used with photocatalysis but they can be used separately or together with catalysts to effect COD oxidation. For ozone there is the problem of the manufacturing route, corona discharge, which is a capital intensive process often limits its application and better route to ozone would be very useful. It is important to note at this point that the oxidants discussed do not have sufficient inherent reactivity to be use without promotion. Thus, catalysis is central to their effective use against both simple organics (often solvents) or complex recalcitrant COD. Hence, the use of Fenton’s catalyst (Fe) for hydrogen peroxide [11]. In terms of catalysis these oxidants together with hypochlorite form a set of materials that can acthas ‘active oxygen transfer (AOT) oxidants’ in the presence of a suitable catalyst. If the AOT oxidant is hypochlorite or hydrogen peroxide then three phase reactions are avoided which greatly simplifies the flowsheet. Cheap, catalytically promoted oxidants with environmentally acceptable products of oxidation that do not require complex chemical engineering and can be produced efficiently would appear to offer one of the best solutions to the general difficulties often observed.3.1. Redox catalysis and active oxygen transferThe mechanism of catalytically promoted oxidation with hydrogen peroxide or sodium hypochlorite cannot be encompassed within one concept, however there are general similarities between the two oxidants that allows one to write a series of reactions for both (Fig. 3) [5]. This type of mechanism could be used to describe a broad range of reactions for either oxidant from catalytic epoxidation to COD oxidation. The inherent usefulness of the reactions is that;1. The reactions take place in a two-phase system.2. High pressure and temperature are not required.3. The catalytic surface can act as an adsorbent of the COD to be oxidised effectively increasing the concentration and hence the rate of oxidation.The simple mechanism shows the selectivity issue with this type of processes. The oxidant can simply be decomposed by the catalyst to oxygen gas – this reaction must be avoided because dioxygen will play no role in COD removal. Its formation is an expensive waste of reagent with oxygen gas ($20/Te) compared to the oxidant ($400–600/Te). To be cost competitive with alternative processes redox catalysis needs excellent selectivity.3.2. Technology mappingThe technologies so far described can be mapped [12] for their applicability with effluent COD concentration (measured as TOC) and effluent flow rate (m3 h-1). The map is shown in Fig. 4. The map outlines the areas where technologies are most effective. The boundaries, although drawn, are in fact fuzzier and should be only used as a guide. Only well into each shape will a technology start to dominate. The underlying cost model behind the map is based on simple assertions – at high COD mass flows only air/oxygen will be able to keep costs down because of the relatively low variable cost of the oxidant. At high COD concentrations and high flows only biological treatment plants have proved themselves viable –of course if done at source recovery becomes an option. At low flows and low COD levels redox AOT catalysis is an important technology – the Synetix Accent 1 process being an example of this type of process (see Fig. 5 for a simplified flowsheet). The catalyst operates under very controlled conditions at pH > 9 and hence metal leaching can be avoided (<5 ppb). The activity and selectivity aspects of the catalyst displayed in Fig. 3 can befurther elaborated to look at the potential surface species. This simple view has been extended by a significant amount of research [3,4,5]. Now the mechanism of such a catalyst can be described in Fig. 6. The key step is to avoid recombination of NiO holes to give peroxy species and this can be contrasted with the hydrogen peroxide situation where the step may be characterized as oxygen vacancy filled. From both recombination will be facilitated by electronic and spatial factors. The range of application of the process is outlined below. From laboratory data some general types of chemical have been found suitable –sulphides, amines, alcohols, ketones, aldehydes, phenols, carboxylic acids, olefins and aromatic hydrocarbons. From industrial trials recalcitrant COD (nonbiodegradable) and sulphur compounds have been successfully demonstrated and a plant oxidising sulphur species has been installed and is operational.4. ConclusionsWastewater treatment processes are in the early stages of development. The key parameters at present are effectiveness and long term reliability. Many processes operating are in this stage, including the redox Accent TM is a trademark of the ICI Group of Companies. catalysis systems. However,once proven, redox catalysis offers many advantages for COD removal from wastewater:1. The low capital cost of installation.2. Simple operation that can be automated.3. Flexible nature of the process – can be easily modified to meet changing demands of legislation.Hence it will be expected to develop into an important technology in wastewater improvement.AcknowledgementsThe author is grateful to Jane Butcher and Keith Kelly of Synetix for discussions on this paper. References[1] R.J. Farrauto, C.H. Bartholomew, Fundamentals of Industrial Catalytic Processes, Blackie Academic and Professional, 1997. F.E. Hancock / Catalysis Today 53 (1999) 3–9 9[2] J.N. Horan, Biological Wastewater Treatment Systems; Theory and Operation, Chichester, Wiley, 1990.[3] F.E. Hancock et al., Catalysis Today 40 (1998) 289.[4] F. King, F.E. Hancock, Catal. Today 27 (1996) 203.[5] J. Hollingworth et al., J. Electron Spectrosc., in press.[6] F. Luck, Environmental Catalysis, in: G. Centi et al. (Eds.), EFCE Publishers, Series 112, p. 125.[7] D. Mantzavinos et al., in: V ogelpohl and Geissen (Eds.), in: Proceedings of the Conference on Water Science and Technology, Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany, May 1996, J. Int. Assoc. Water Quality, Pergamon, 1997.[8] R. Venkatadri, R.W. Peters, Hazardous Waste Hazardous Mater. 10 (1993) 107.[9] A.M. Braun, E. Oliveros, Water Sci. Tech. 35 (1997) 17.[10] D. Bahnemann et al., Aquatic and surface photochemistry, Am. Chem. Soc. Symp. Ser. (1994) 261.[11] J. Prousek, Chem. Lisy 89 (1995) 11.工业废水回用的接触反应策略摘要:无论从控制污染还是资源恢复的角度,接触反应都是被广泛应用并极具经济效益的。